Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Pfizer is among the Big Pharma companies trying to block legislation strengthening whistleblowers’ ability to report corporate fraud.

In the midst of a dizzying legislative environment, with much attention focused on the Build Back Better debate, major corporate interests, including Pfizer, are fighting an update to the False Claims Act, a Civil War-era law that rewards whistleblowers for filing anti-fraud lawsuits against contractors on behalf of the government.

The law has historically returned $67 billion to the government, with whistleblowers successfully helping uncover wrongdoing by military contractors, banks, and pharmaceutical companies.

The law has been particularly thorny for Pfizer. In 2009, Pfizer paid $2.3 billion in criminal and civil fines to settle allegations that the company illegally marketed several drugs for off-label purposes that were specifically not approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The company instructed its marketing team to advertise Bextra, which was approved only for arthritis and menstrual cramps, for acute and surgical pain issues. The lawsuit, brought under the False Claims Act through the actions of six whistleblowers, ended in one of the largest health care fraud settlements in history.

But the law poses far less risk today to companies engaged in criminal behavior. That’s because the anti-fraud statute has been severely hampered by a series of federal court decisions that radically expanded the scope of what’s known as “materiality.” In 2016, the Supreme Court ruled in Universal Health Services v. United States ex rel. Escobar that a fraud lawsuit could be dismissed if the government continued to pay the contractor.

The court reasoned that if the government continues to pay a company despite fraudulent activity, then the fraud is not “material” to the contract. That ruling functionally neutered application of the False Claims Act against many companies that are so large that the government cannot abruptly sever payments, especially against large health care interests and defense contractors.

Recent court decisions, including cases involving Honeywell and Halliburton, show contractors winning dismissal of fraud cases by simply citing “continued government payments.” Last year, a federal district court dismissed a False Claims Act case against engineering company Aecom brought by a whistleblower alleging widespread billing fraud for a $2 billion contract in Afghanistan. Aecom lawyers also cited the government’s continued payments to the company. The lawsuit is now under appeal.

What’s more, the federal government has taken an active role in discouraging cases. In 2018, the Trump administration’s Justice Department issued the “Granston Memo,” which encouraged the dismissal of more whistleblower-initiated suits under the False Claims Act.

In October, Attorney General Merrick Garland officially rescinded the “overly restrictive” memo, a move widely seen as designed to promote greater False Claims Act enforcement.

The erosion of the statute has brought together a bipartisan push, led by Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, to update the law to give whistleblowers greater protection against potential industry retaliation and make it more difficult for companies charged with fraud to dismiss cases on procedural grounds.

Earlier this year, as he introduced the legislation, Grassley took to the Senate floor to showcase images of scrapped multibillion Afghanistan War contracts and examples of fraud cases that have escaped accountability because of the judicial constraints placed on the False Claims Act.

“Defendants get away with scalping the taxpayers because some government bureaucrats failed to do their job,” thundered the senator. “In my many years of investigating the Department of Defense, it has taught me that a Pentagon bureaucrat is rarely motivated to recognize fraud. That’s because the money doesn’t come out of their pocket.”

The legislation, the False Claims Amendments Act of 2021, adjusts the materiality standard to include instances in which the government made payments despite knowledge of fraud “if other reasons exist” for continuing the contract. The bill also expands the anti-retaliation protections of the law, which currently only cover current whistleblower employees of a company. The bill seeks to prevent an industry from blacklisting former whistleblowers seeking employment.

That push has run into a buzzsaw of corporate opposition, some of it disclosed and some of it shrouded from public view. Pfizer hired Hazen Marshall, a former policy director for Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., to lobby on the issue, along with the law firm Williams & Jensen, a powerhouse that employs an array of former congressional staffers.

Pfizer, which has cast itself as a hero in the fight against Covid-19 and a trustworthy corporate citizen, did not respond to a request for comment.

In an initial test vote, the bill was blocked. In August, Grassley proposed his False Claims Amendments Act as an amendment to the bipartisan infrastructure agreement in the Senate. The bill, however, never reached the floor for a vote because of an objection lodged on behalf of Senate Democrats.

In October, the legislation again found a hearing. Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., attempted to erase most of the bill in a Judiciary Committee meeting. The amendment Cotton proposed sought to strike all substantive lines of the bill except for the first title, which is simply the description of the legislation. During committee debate, Cotton argued that the Supreme Court “made the right decision” in the Escobar case and the “continued payment” standard for materiality. The legislation “potentially could increase health care costs,” the senator argued, echoing industry claims that litigation from the False Claims Act would force health care interests to raise prices.

The American Hospital Association reportedly lobbied to delay a vote, but the bill eventually passed 15-7 out of the Senate Judiciary Committee, with the support of Grassley and his main co-sponsor, Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt.

“This is a very concerted lobbying effort that really took our supporters on Capitol Hill by surprise,” said Stephen Kohn, a whistleblower attorney with the law firm Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto.

Many of the companies engaged in the lobbying fight have chosen to conceal their efforts through undisclosed third-party groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which has made the Grassley bill one of its primary targets for defeat. The chamber does not disclose its membership or which corporations direct its advocacy, but previous reporting suggests companies such as Halliburton, Lockheed Martin, and JPMorgan Chase, among others that have faced False Claims Act violations in the past.

Other trade groups — including the American Hospital Association, the Healthcare Leadership Council, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, and the American Bankers Association — have lobbied against the bill without disclosing the companies directing their actions.

The known corporate interests lobbying on the Grassley bill include Pfizer, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Merck, and Genentech. These companies listed the legislation on lobbying disclosures. All five have paid nine-figure settlements over health care fraud brought to light through the False Claims Act.

“Drug companies are notorious for paying kickbacks, giving benefits in exchange for a competitive advantage. Drug companies and health care firms are about 80 percent of the False Claim[s] Act recoveries for a reason,” said Kohn.

In the case of Pfizer’s record settlement, whistleblowers charged that the company promoted Bextra for uses that were not approved by the FDA, placing patients at risk for heart attack and stroke. The company allegedly paid doctors kickbacks for off-label uses. The False Claims Act, like other “qui tam” laws, awards whistleblowers a portion of the money the government recovers from lawsuits.

“The whole culture of Pfizer is driven by sales, and if you didn’t sell drugs illegally, you were not seen as a team player,” said John Kopchinski, one of the Pfizer whistleblowers, following the settlement.

The Grassley initiative is championed by a diverse array of watchdog groups over government waste. Taxpayers Against Fraud, the National Whistleblower Center, the Project on Government Oversight, and the Government Accountability Project are among the groups officially supporting the update to the anti-fraud law.

But advocates have expressed confusion over the involvement of several other supposed taxpayer protection organizations. Citizens Against Government Waste and Americans for Tax Reform, two conservative groups that do not disclose donor information, filed a letter to lawmakers urging them to vote down the Grassley measure.

Despite Citizens Against Government Waste’s official focus on fighting government waste, the very intent of the False Claims Act, the group’s lobbying arm argued in a letter that the bill was not appropriate for inclusion in the infrastructure package because it is “not related to traditional infrastructure” and the bill is not fully “understood by the 95 senators who have not cosponsored” the legislation. Americans for Tax Reform similarly argued that the legislation had not “received proper debate.”

Neither Citizens Against Government Waste nor Americans for Tax Reform responded to a request for comment explaining why they have lobbied so aggressively against taxpayer protection legislation and whether any donor interests are involved.

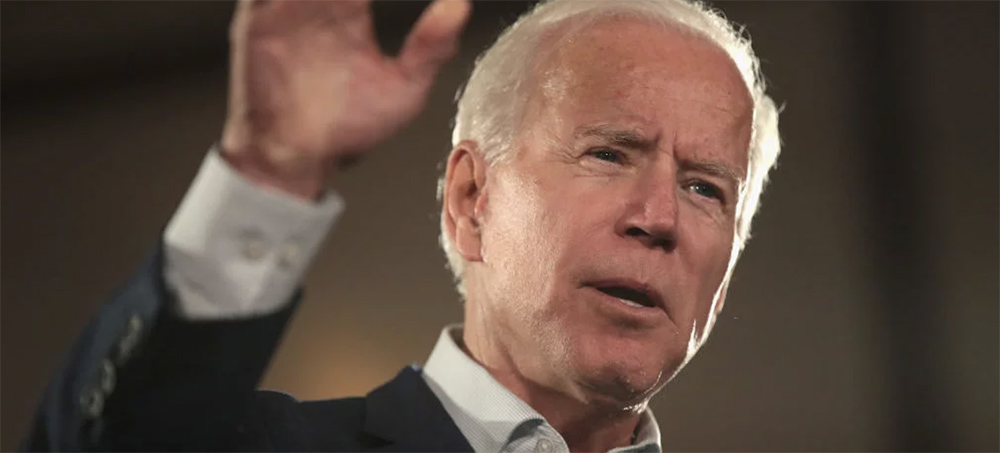

Joe Biden. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Joe Biden. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

When it came to work and the pandemic, you could say that I led the way. By the time it struck, I had left my job as an editor in publishing and had been working at home for decades. I was, in that sense, a remote worker long before Zoom made working from home a potential reality of everyday life. Mind you, in those pre-pandemic years, I was also toiling alone in my little home office in an America working its way toward Gilded Age-levels of inequality, the collapse of the union movement, and — as TomDispatch regular Rebecca Gordon makes all too clear today — the institution in so many jobs of hellish working hours and conditions.

And yes, the pandemic has been a veritable godsend for billionaires who’ve made money in such a stunning fashion while it killed millions (and then taken off for outer space to spend it). Still, on the rare bright side in these nearly two pandemic years, fear of that disease and of labor that endangered workers because of it in jobs ranging from meat packing to truck driving — once considered high-paying blue-collar work but now a nightmare of low wages and poor conditions and short 80,000 drivers this Covid-19 Christmas season! — led staggering millions to voluntarily quit their jobs in what’s been called “the Great Resignation.” That, in turn, opened the way for a revived union movement, rising labor militancy, the recent month of “Striketober,” and potentially better pay and working conditions.

In other words, it’s just possible that, on the other side of the pandemic (if such a side even exists), could lie a better working America in every sense of the phrase — or, of course, if Donald Trump and the Republican Party have their way, it could lead to an all-too-literal hell on earth. In the meantime, consider with Gordon what it means for an American president, in this case a Democrat, to call for dock workers to go on a 24/7 schedule to ensure that Christmas presents arrive at homes on time. A Gilded Age? Not for those workers heading for the night shift, that’s for sure. Tom

-Tom Engelhardt, TomDispatch

Supply-Chain Woes

The "Graveyard Shift" in a Pandemic World

The purpose of expanding port hours, according to the New York Times, was “to relieve growing backlogs in the global supply chains that deliver critical goods to the United States.” Reading this, you might be forgiven for imagining that an array of crucial items like medicines or their ingredients or face masks and other personal protective equipment had been languishing in shipping containers anchored off the West Coast. You might also be forgiven for imagining that workers, too lazy for the moment at hand, had chosen a good night’s sleep over the vital business of unloading such goods from boats lined up in their dozens offshore onto trucks, and getting them into the hands of the Americans desperately in need of them. Reading further, however, you’d learn that those “critical goods” are actually things like “exercise bikes, laptops, toys, [and] patio furniture.”

Fair enough. After all, as my city, San Francisco, enters what’s likely to be yet another almost rainless winter on a planet in ever more trouble, I can imagine my desire for patio furniture rising to a critical level. So, I’m relieved to know that dock workers will now be laboring through the night at the command of the president of the United States to guarantee that my needs are met. To be sure, shortages of at least somewhat more important items are indeed rising, including disposable diapers and the aluminum necessary for packaging some pharmaceuticals. Still, a major focus in the media has been on the specter of “slim pickings this Christmas and Hanukkah.”

Providing “critical” yard furnishings is not the only reason the administration needs to unkink the supply chain. It’s also considered an anti-inflation measure (if an ineffective one). At the end of October, the Consumer Price Index had jumped 6.2% over the same period in 2020, the highest inflation rate in three decades. Such a rise is often described as the result of too much money chasing too few goods. One explanation for the current rise in prices is that, during the worst months of the pandemic, many Americans actually saved money, which they’re now eager to spend. When the things people want to buy are in short supply — perhaps even stuck on container ships off Long Beach and Los Angeles — the price of those that are available naturally rises.

Republicans have christened the current jump in the consumer price index as “Bidenflation,” although the administration actually bears little responsibility for the situation. But Joe Biden and the rest of the Democrats know one thing: if it looks like they’re doing nothing to bring prices down, there will be hell to pay at the polls in 2022 and so it’s the night shift for dock workers and others in Los Angeles, Long Beach, and possibly other American ports.

However, running West Coast ports 24/7 won’t solve the supply-chain problem, not when there aren’t enough truckers to carry that critical patio furniture to Home Depot. The shortage of such drivers arises because there’s more demand than ever before, and because many truckers have simply quit the industry. As the New York Times reports, “Long hours and uncomfortable working conditions are leading to a shortage of truck drivers, which has compounded shipping delays in the United States.”

Rethinking (Shift) Work

Truckers aren’t the only workers who have been rethinking their occupations since the coronavirus pandemic pressed the global pause button. The number of employees quitting their jobs hit 4.4 million this September, about 3% of the U.S. workforce. Resignations were highest in industries like hospitality and medicine, where employees are most at risk of Covid-19 exposure.

For the first time in many decades, workers are in the driver’s seat. They can command higher wages and demand better working conditions. And that’s exactly what they’re doing at workplaces ranging from agricultural equipment manufacturer John Deere to breakfast-cereal makers Kellogg and Nabisco. I’ve even been witnessing it in my personal labor niche, part-time university faculty members (of which I’m one). So allow me to pause here for a shout-out to the 6,500 part-time professors in the University of California system: Thank you! Your threat of a two-day strike won a new contract with a 30% pay raise over the next five years!

This brings me to Biden’s October announcement about those ports going 24/7. In addition to demanding higher pay, better conditions, and an end to two-tier compensation systems (in which laborers hired later don’t get the pay and benefits available to those already on the job), workers are now in a position to reexamine and, in many cases, reject the shift-work system itself. And they have good reason to do so.

So, what is shift work? It’s a system that allows a business to run continuously, ceaselessly turning out and/or transporting widgets year after year. Workers typically labor in eight-hour shifts: 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., 4:00 p.m. to midnight, and midnight to 8:00 a.m., or the like. In times of labor shortages, they can even be forced to work double shifts, 16 hours in total. Businesses love shift work because it reduces time (and money) lost to powering machinery up and down. And if time is money, then more time worked means more profit for corporations. In many industries, shift work is good for business. But for workers, it’s often another story.

The Graveyard Shift

Each shift in a 24-hour schedule has its own name. The day shift is the obvious one. The swing shift takes you from the day shift to the all-night, or graveyard, shift. According to folk etymology, that shift got its name because, once upon a time, cemetery workers were supposed to stay up all night listening for bells rung by unfortunates who awakened to discover they’d been buried alive. While it’s true that some coffins in England were once fitted with such bells, the term was more likely a reference to the eerie quiet of the world outside the workplace during the hours when most people are asleep.

I can personally attest to the strangeness of life on the graveyard shift. I once worked in an ice cream cone factory. Day and night, noisy, smoky machines resembling small Ferris wheels carried metal molds around and around, while jets of flame cooked the cones inside them. After a rotation, each mold would tip, releasing four cones onto a conveyor belt, rows of which would then approach my station relentlessly. I’d scoop up a stack of 25, twirl them around in a quick check for holes, and place them in a tall box.

Almost simultaneously, I’d make cardboard dividers, scoop up three more of those stacks and seal them, well-divided, in that box, which I then inserted in an even larger cardboard carton and rushed to a giant mechanical stapler. There, I pressed it against a switch, and — boom-ba-da-boom — six large staples would seal it shut, leaving me just enough time to put that carton atop a pallet of them before racing back to my machine, as new columns of just-baked cones piled up, threatening to overwhelm my worktable.

The only time you stopped scooping and boxing was when a relief worker arrived, so you could have a brief break or gobble down your lunch. You rarely talked to your fellow-workers, because there was only one “relief” packer, so only one person at a time could be on break. Health regulations made it illegal to drink water on the line and management was too cheap to buy screens for the windows, which remained shut, even when it was more than 100 degrees outside.

They didn’t like me very much at the Maryland Pacific Cone Company, maybe because I wanted to know why the high school boys who swept the floors made more than the women who, since the end of World War II, had been climbing three rickety flights of stairs to stand by those machines. In any case, management there started messing with my shifts, assigning me to all three in the same week. As you might imagine, I wasn’t sleeping a whole lot and would occasionally resort to those “little white pills” immortalized in the truckers’ song “Six Days on the Road.”

But I’ll never forget one graveyard shift when an angel named Rosie saved my job and my sanity. It was probably three in the morning. I’d been standing under fluorescent lights, scooping, twirling, and boxing for hours when the universe suddenly stood still. I realized at that moment that I’d never done anything else since the beginning of time but put ice cream cones in boxes and would never stop doing so until the end of time.

If time lost its meaning then, dimensions still turned out to matter a lot, because the cones I was working on that night were bigger than I was used to. Soon I was falling behind, while a huge mound of 40-ounce Eat-It-Alls covered my table and began to spill onto the floor. I stared at them, frozen, until I suddenly became aware that someone was standing at my elbow, gently pushing me out of the way.

Rosie, who had been in that plant since the end of World War II, said quietly, “Let me do this. You take my line.” In less than a minute, she had it all under control, while I spent the rest of the night at her machine, with cones of a size I could handle.

I have never been so glad to see the dawn.

The Deadly Reality of the Graveyard Shift

So, when the president of the United States negotiated to get dock workers in Los Angeles to work all night, I felt a twinge of horror. There’s another all-too-literal reason to call it the “graveyard” shift. It turns out that working when you should be in bed is dangerous. Not only do more accidents occur when the human body expects to be asleep, but the long-term effects of night work can be devastating. As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reports, the many adverse effects of night work include:

“type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, metabolic disorders, and sleep disorders. Night shift workers might also have an increased risk for reproductive issues, such as irregular menstrual cycles, miscarriage, and preterm birth. Digestive problems and some psychological issues, such as stress and depression, are more common among night shift workers. The fatigue associated with nightshift can lead to injuries, vehicle crashes, and industrial disasters.”

Some studies have shown that such shift work can also lead to decreased bone-mineral density and so to osteoporosis. There is, in fact, a catchall term for all these problems: shift-work disorder.

In addition, studies directly link the graveyard shift to an increased incidence of several kinds of cancer, including breast and prostate cancer. Why would disrupted sleep rhythms cause cancer? Because such disruptions affect the release of the hormone melatonin. Most of the body’s cells contain little “molecular clocks” that respond to daily alternations of light and darkness. When the light dims at night, the pineal gland releases melatonin, which promotes sleep. In fact, many people take it in pill form as a “natural” sleep aid. Under normal circumstances, such a melatonin release continues until the body encounters light again in the morning.

When this daily (circadian) rhythm is disrupted, however, so is the regular production of melatonin, which turns out to have another important biological function. According to NIOSH, it “can also stop tumor growth and protect against the spread of cancer cells.” Unfortunately, if your job requires you to stay up all night, it won’t do this as effectively.

There’s a section on the NIOSH website that asks, “What can night shift workers do to stay healthy?” The answers are not particularly satisfying. They include regular checkups and seeing your doctor if you have any of a variety of symptoms, including “severe fatigue or sleepiness when you need to be awake, trouble with sleep, stomach or intestinal disturbances, irritability or bad mood, poor performance (frequent mistakes, injuries, vehicle crashes, near misses, etc.), unexplained weight gain or loss.”

Unfortunately, even if you have access to healthcare, your doctor can’t write you a prescription to cure shift-work disorder. The cure is to stop working when your body should be asleep.

An End to Shift Work?

Your doctor can’t solve your shift work issue because, ultimately, it’s not an individual problem. It’s an economic and an ethical one.

There will always be some work that must be performed while most people are sleeping, including healthcare, security, and emergency services, among others. But most shift work gets done not because life depends upon it, but because we’ve been taught to expect our patio furniture on demand. As long as advertising and the grow-or-die logic of capitalism keep stoking the desire for objects we don’t really need, may not even really want, and will sooner or later toss on a garbage pile in this or some other country, truckers and warehouse workers will keep damaging their health.

Perhaps the pandemic, with its kinky supply chain, has given us an opportunity to rethink which goods are so “critical” that we’re willing to let other people risk their lives to provide them for us. Unfortunately, such a global rethink hasn’t yet touched Joe Biden and his administration as they confront an ongoing pandemic, supply-chain problems, a rise in inflation, and — oh yes! — an existential climate crisis that gets worse with every plastic widget produced, packed, and shipped.

It’s time for Biden — and the rest of us — to take a breath and think this through. There are good reasons that so many people are walking away from underpaid, life-threatening work. Many of them are reconsidering the nature of work itself and its place in their lives, no matter what the president or anyone else might wish.

And that’s a paradigm shift we all could learn to live with.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Billionaire Jeff Bezos. (photo: David Ryder/Getty Images)

Billionaire Jeff Bezos. (photo: David Ryder/Getty Images)

A U.S. labor board official is ordering a revote after an agency review found Amazon improperly pressured warehouse staff to vote against joining a union, tainting the original election enough to scrap its results. The decision was issued Monday by a regional director of the National Labor Relations Board. Amazon is expected to appeal.

The news puts the warehouse in Bessemer, outside Birmingham, back in the spotlight as a harbinger of labor-organizing efforts at Amazon, which is now America's second-largest private employer with more than 950,000 employees.

The union drive is being led by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. Its president, Stuart Appelbaum, hailed Monday's development:

"Today's decision confirms what we were saying all along – that Amazon's intimidation and interference prevented workers from having a fair say in whether they wanted a union in their workplace."

Kelly Nantel, an Amazon spokesperson, noted that employees at the warehouse overwhelmingly chose not to join the union in the previous vote. "It's disappointing that the NLRB has now decided that those votes shouldn't count. As a company, we don't think unions are the best answer for our employees."

During the first attempt in early 2021 — seen as the most consequential union election in recent history — Bessemer workers voted more than 2-to-1 against unionizing. It was a stinging defeat for the high-profile push to organize Amazon's U.S. workers after gaining nationwide support, including from President Biden, other politicians and celebrities.

That vote, tallied in April, was held by mail due to pandemic concerns. More than half the warehouse staff had cast ballots.

The union filed a legal challenge to the election, alleging that Amazon engaged in unfair labor practices. Amazon denied the charge. The NLRB held a hearing before the hearing officer last month recommended a do-over of the Bessemer election.

Amazon appealed the recommendation, saying it did not act illegally or intimidate workers and called on the agency and the union to accept the choice of the Bessemer workers. The union maintained that Amazon "cheated (and) got caught."

Unions are a prominent presence at Amazon in Europe, but the company has so far fought off labor-organizing efforts in the United States. The election in Bessemer was the first union vote since 2014. The Teamsters union has passed a resolution that would prioritize its Amazon unionization campaign.

In October, workers from a Staten Island warehouse cluster in New York petitioned federal officials for a union election but later withdrew the request.

Previously, the NLRB's hearing shed new light on Amazon's anti-union campaign during the Bessemer election. One warehouse staffer testified that during mandatory meetings at the facility, managers said the fulfillment center could shut down if the staff voted to unionize. Other workers said they were told that the union would waste their dues on fancy vacations and cars.

One key controversy had been over a new mailbox in the warehouse's private parking lot that Amazon said was installed by the U.S. Postal Service to make voting "convenient, safe and private." However, the mailbox's placement inside an Amazon tent right by the workplace prompted some employees to wonder whether the company was trying to monitor the vote.

U.S. Postal Service official Jay Smith, who works as a liaison for large clients like Amazon, testified that he was surprised to see the corporate-branded tent around the mailbox because the company appeared to have found a way around his explicit instructions to not place anything physically on the mailbox.

But Smith and other Postal Service officials also testified that no one at Amazon has been provided keys to access the outgoing mail or, in this case, election ballots. A pro-union Amazon worker told the hearing that he saw corporate security officers opening the mailbox.

Donald Trump. (photo: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Donald Trump. (photo: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Sources tell Guardian Trump pressed lieutenants at Willard hotel in Washington about ways to delay certification of election result

The former president first told the lieutenants his vice-president, Mike Pence, was reluctant to go along with the plan to commandeer his largely ceremonial role at the joint session of Congress in a way that would allow Trump to retain the presidency for a second term.

But as Trump relayed to them the situation with Pence, he pressed his lieutenants about how to stop Biden’s certification from taking place on 6 January, and delay the certification process to get alternate slates of electors for Trump sent to Congress.

The former president’s remarks came as part of strategy discussions he had from the White House with the lieutenants at the Willard – a team led by Trump lawyers Rudy Giuliani, John Eastman, Boris Epshteyn and Trump strategist Steve Bannon – about delaying the certification.

Multiple sources, speaking to the Guardian on the condition of anonymity, described Trump’s involvement in the effort to subvert the results of the 2020 election.

Trump’s remarks reveal a direct line from the White House and the command center at the Willard. The conversations also show Trump’s thoughts appear to be in line with the motivations of the pro-Trump mob that carried out the Capitol attack and halted Biden’s certification, until it was later ratified by Congress.

The former president’s call to the Willard hotel about stopping Biden’s certification is increasingly a central focus of the House select committee’s investigation into the Capitol attack, as it raises the specter of a possible connection between Trump and the insurrection.

Several Trump lawyers at the Willard that night deny Trump sought to stop the certification of Biden’s election win. They say they only considered delaying Biden’s certification at the request of state legislators because of voter fraud.

The former president made several calls to the lieutenants at the Willard the night before 6 January. He phoned the lawyers and the non-lawyers separately, as Giuliani did not want non-lawyers to participate on legal calls and jeopardise attorney-client privilege.

Trump’s call to the lieutenants came a day after Eastman, a late addition to the Trump legal team, outlined at a 4 January meeting at the White House how he thought Pence could usurp his role in order to stop Biden’s certification from happening at the joint session.

At the meeting, which was held in the Oval Office and attended by Trump, Pence, Pence’s chief of staff, Marc Short, and his legal counsel, Greg Jacob, Eastman presented a memo that detailed how Pence could insert himself into the certification and delay the process.

The memo outlined several ways for Pence to commandeer his role at the joint session, including throwing the election to the House, or adjourning the session to give states time to send slates of electors for Trump on the basis of election fraud – Eastman’s preference.

The then acting attorney general, Jeff Rosen, and his predecessor, Bill Barr, who had both been appointed by Trump, had already determined there was no evidence of fraud sufficient to change the outcome of the 2020 election.

Eastman told the Guardian last month that the memo only presented scenarios and was not intended as advice. “The advice I gave the vice-president very explicitly was that I did not think he had the authority simply to declare which electors to count,” Eastman said.

Trump seized on the memo – first reported by Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Robert Costa in their book Peril – and pushed Pence to adopt the schemes, which some of the other lieutenants at the Willard later told Trump were legitimate ways to flip the election.

But Pence resisted Trump’s entreaties, and told him in the Oval Office the next day that Trump should count him out of whatever plans he had to subvert the results of the 2020 election at the joint session, because he did not intend to take part.

Trump was furious at Pence for refusing to do him a final favor when, in the critical moment underpinning the effort to reinstall Trump as president, he phoned lieutenants at the Willard sometime between the late evening on 5 January and the early hours of 6 January.

From the White House, Trump made several calls to lieutenants, including Giuliani, Eastman, Epshteyn and Bannon, who were huddled in suites complete with espresso machines and Cokes in a mini-fridge in the north-west corner of the hotel.

On the calls, the former president first recounted what had transpired in the Oval Office meeting with Pence, informing Bannon and the lawyers at the Willard that his vice-president appeared ready to abandon him at the joint session in several hours’ time.

“He’s arrogant,” Trump, for instance, told Bannon of Pence – his own way of communicating that Pence was unlikely to play ball – in an exchange reported in Peril and confirmed by the Guardian.

But on at least one of those calls, Trump also sought from the lawyers at the Willard ways to stop the joint session to ensure Biden would not be certified as president on 6 January, as part of a wider discussion about buying time to get states to send Trump electors.

The fallback that Trump and his lieutenants appeared to settle on was to cajole Republican members of Congress to raise enough objections so that even without Pence adjourning the joint session, the certification process would be delayed for states to send Trump slates.

It was not clear whether Trump discussed on the call about the prospect of stopping Biden’s certification by any means if Pence refused to insert himself into the process, but the former president is said to have enjoyed watching the insurrection unfold from the dining room.

But the fact that Trump considered ways to stop the joint session may help to explain why he was so reluctant to call off the rioters and why the Republican senator Ben Sasse told the conservative talkshow host Hugh Hewitt that he heard Trump seemed “delighted” about the attack.

The lead Trump lawyer at the Willard, Giuliani, appearing to follow that fallback plan, called at least one Republican senator later that same evening, asking him to help keep Congress adjourned and stall the joint session beyond 6 January.

In a voicemail recorded at about 7pm on 6 January, and reported by the Dispatch, Giuliani implored the Republican senator Tommy Tuberville to object to 10 states Biden won once Congress reconvened at 8pm, a process that would have concluded 15 hours later, close to 7 January.

“The only strategy we can follow is to object to numerous states and raise issues so that we get ourselves into tomorrow – ideally until the end of tomorrow,” Giuliani said.

Liz Harrington, a spokesperson for Trump, disputed the account of Trump’s call after publication. “This is totally false,” Harrington said, without giving specifics. Giuliani did not respond to a request for comment. Eastman, Epshteyn and Bannon declined to comment.

Trump made several calls the day before the Capitol attack from both the White House residence, his preferred place to work, as well as the West Wing, but it was not certain from which location he phoned his top lieutenants at the Willard.

The White House residence and its Yellow Oval Room – a Trump favorite – is significant since communications there, including from a desk phone, are not automatically memorialized in records sent to the National Archives after the end of an administration.

But even if Trump called his lieutenants from the West Wing, the select committee may not be able to fully uncover the extent of his involvement in the events of 6 January, unless House investigators secure testimony from individuals with knowledge of the calls.

That difficulty arises since calls from the White House are not necessarily recorded, and call detail records that the select committee is suing to pry free from the National Archives over Trump’s objections about executive privilege, only show the destination of the calls.

House select committee investigators this month opened a new line of inquiry into activities at the Willard hotel, just across the street from the White House, issuing subpoenas to Eastman and the former New York police commissioner Bernard Kerik, an assistant to Giuliani.

The chairman of the select committee, Bennie Thompson, said in a statement that the panel was pursuing the Trump officials at the Willard to uncover “every detail about their efforts to overturn the election, including who they were talking to in the White House and in Congress”.

A health care worker administers a dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine. (photo: Roger Kisby/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

A health care worker administers a dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine. (photo: Roger Kisby/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

With the spread of the new Omicron variant and low levels of vaccination throughout much of the world, there’s still no real end to COVID in sight. It’s bad news for global public health — but great news for big pharmaceutical companies.

Moderna and Pfizer have added billions to their market capitalizations in a matter of days since news of Omicron first broke amid an anticipated demand for booster shots and, by extension, huge profits. 2021 has already been a banner year for the various pharma companies who’ve successfully made their brands synonymous with the distribution of vaccines — Pfizer’s profits jumping some 124 percent in the first three quarters of the year when compared to 2020 and Johnson & Johnson’s some 24 percent.

As lucrative business models go, Big Pharma’s pandemic strategy is about as good as it gets. The mRNA-type vaccines produced by the likes of Pfizer and Moderna were only developed thanks to billions in publicly funded research, and both companies paid well under the statutory US tax rate in the first half of this year. With the encouragement, protection, and cooperation of some of the world’s richest and most powerful states, both have also overwhelmingly sold shots within wealthy countries — successfully charging as much as twenty-four times the actual production costs according to one analysis by mRNA scientists at Imperial College London, resulting in doses five times more expensive than they need to be.

As an actual response to a global pandemic goes, the Big Pharma–led vaccine rollout has wrought a completely avoidable humanitarian crisis that’s quite rightly called vaccine apartheid by its critics. Breaking this corporate grip is a necessary step toward increasing vaccine supply and bringing urgently needed doses to billions who need them. But as the global news cycle concerns itself with the emergence of yet another variant, it’s also a basic prerequisite to ending the pandemic for everyone, even in rich countries with relatively high rates of vaccination.

Until vaccine production formulas are shared and doses made widely available at low cost, we can expect further unnecessary infections and deaths — and a hugely profitable industry continuing to make a killing from it all.

Marisol Cuadras, who was shot dead last week, was a feminist activist in Sonora, Mexico. (photo: IG)

Marisol Cuadras, who was shot dead last week, was a feminist activist in Sonora, Mexico. (photo: IG)

Marisol Cuadras was killed in the Mexican state of Sonora on International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women.

“Unfortunately, there was collateral damage,” Admiral Rafael Ojeda, secretary of the Navy, said during the president’ morning press conference last week. His reference to murdered activist Marisol Cuadras as a “muchachita,” or “little girl,” further inflamed indignation in feminist circles.

The attack Thursday evening in Guaymas, Sonora that killed Cuadras has caused an outcry in Mexico, where an overage of 10 women are murdered daily, according to Amnesty International. Cuadras, wearing black with a purple scarf, was participating in a peaceful demonstration on International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, when she was shot and killed.

The brazen nature of the attack also underscores just how emboldened organized groups have become — sometimes taking siege of entire cities in an effort to seize control or kill a rival. Record levels of violence in Mexico have cast doubt on President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s embrace of the armed forces to address the country’s security problems.

Ojeda said the intended target of Thursday’s attack was Andrés Humberto Cano Ahuir, a Navy captain who became police chief in 2019. His appointment was part of a federal plan to stem violence in Sonora by bringing in the military to lead up local police forces, according to local news reports.

Authorities have said a drug cartel was behind the attack and have since arrested 11 people. Turf wars between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel are believed to have contributed to rising violence in the state.

Sonora’s state prosecutor said the felled gunman was a 49-year-old window cleaner who suffered addiction problems and had been recruited to carry out the shooting, and that the attackers used at least one hand grenade, which appeared to have hit a car.

Cuadras was a member of the feminist collective “Feminists of the Sea.” A student at the Center for Technological Studies in Guaymas, she described herself in her Twitter profile as a proud feminist and environmentalist. Cuadras and other members of the collective posed for a picture with the mayor moments before the attack at 6:40 p.m. The police chief had also stepped outside to speak with the protestors. Neither the mayor nor the police chief were harmed.

Cuadras’s mother, identified in news reports only as Teresa, wrote on Facebook that her daughter wanted to protest peacefully. “I raise my voice in your name, my love, for the right to freedom of expression without violence. I raise my voice for injustice. I raise my voice for everyone who has left us, may you rest in peace.”

The governor of Sonora, Alfonso Durazo, said “federal, state and municipal” authorities are looking into the attack, and added: “We are going to get those who are responsible.”

Climate change activism. (image: Christina Animashaun/Vox)

Climate change activism. (image: Christina Animashaun/Vox)

These are seven of the most high-impact, cost-effective, evidence-based organizations. You may not have heard of them.

The trouble is, it can be genuinely hard to figure out how to direct your money wisely if you want to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. There’s a glut of environmental organizations out there — but how do you know which are the most impactful?

Below is a list of seven of the most high-impact, cost-effective, and evidence-based organizations. We’re not including bigger-name groups, such as the Environmental Defense Fund, the Nature Conservancy, or the Natural Resources Defense Council, because most big organizations are already relatively well-funded (those three, for example, recently got $100 million each from the Bezos Earth Fund). The groups we list below seem to be doing something especially promising in the light of certain criteria: importance, tractability, and neglectedness.

Important targets for change are ones that drive a big portion of global emissions. Tractable problems are ones where we can actually make progress right now. And neglected problems are ones that aren’t already getting a big influx of cash from other sources like the government or philanthropy, and so could really use money from smaller donors.

Founders Pledge, an organization that guides entrepreneurs committed to donating a portion of their proceeds to effective charities, and Giving Green, a climate charity evaluator, used these same criteria to assess climate organizations. Their research informed much of the list below. As in the Founders Pledge and Giving Green recommendations, we’ve chosen to look at groups focused on mitigation (tackling the root causes of climate change by reducing emissions) rather than adaptation (decreasing the suffering from the impacts of climate change). Both are important, but the focus of this piece is preventing further catastrophe.

We’ve also selected organizations that are tackling this problem on different levels, based on different theories of change. Some advocate for high-level policy change, while others are focused on building activist movements or achieving immediate emissions reductions.

Dan Stein, director of Giving Green, says we should have a diverse portfolio of mitigation strategies. “There should be some short-term projects that give us certainty about reducing emissions now,” he told Vox last year. “But I also buy the argument that that’s not going to be enough — we need some moonshot projects.”

With that in mind, here are the organizations where your money is likely to have an exceptionally positive impact.

1) Clean Air Task Force

What it does: Since its founding 25 years ago, the Clean Air Task Force (CATF) has worked to curb air pollution in all its forms through regulation at the US state and federal levels. It successfully campaigned to reduce the pollution caused by coal-fired power plants; helped establish regulations of diesel, shipping, and methane emissions; and worked to limit the power sector’s CO2 emissions. CATF also advocates for the adoption of innovative, neglected low- and zero-carbon technologies, from advanced nuclear power to super-hot rock geothermal energy.

Why you should consider donating: CATF stands out not only for its impressive impact on US climate policy but also for being a pioneer in the environmental space. (Disclosure: Sigal donated to CATF in 2021.) It was one of the first major environmental organizations to publicly campaign against neglected superpollutants like methane, which plays a central but underrecognized role in the ongoing climate catastrophe.

At this year’s UN Climate Change Conference, or COP26, more than 100 countries committed to the Global Methane Pledge, which aims for a reduction in methane by at least 30 percent by the end of the decade — an issue that CATF and other environmental nonprofits had foregrounded. More recently, CATF has begun expanding beyond the US to operate in Latin America, the EU, Western Asia, and Northern Africa.

2) Carbon180

What it does: As its name suggests, Carbon180 is an environmental nonprofit focused on flipping humanity’s current relationship with carbon upside down, so that we take in more carbon than we emit. A relatively new organization with a modest budget of less than $3 million in 2020, it works toward its goal of carbon removal (or “negative emissions”) through advocacy on Capitol Hill — an approach that may have reaped dividends with the recent passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which included billions in research and development for carbon removal.

Why you should consider donating: Scientists agree that for the world to have any hope of capping global warming at 2 degrees Celsius, let alone 1.5, by 2100, we’ll need some deployment of carbon-removal technologies. In the increasingly likely scenario that we’ll miss both of those targets through cutting emissions (right before COP26 began, UN researchers calculated that we’re likely to hit 2.7 degrees of warming by the end of the century), carbon removal technologies can play an essential role.

That’s because even if ideal timelines for capping and reducing emissions are not realized, so long as we have the scalable technology, carbon can continue to be removed from the atmosphere to keep the planet habitable.

Carbon removal generally has been underfunded, in part because the tech is pretty new. Carbon180 can play an important role by advocating for more federal and state funding for R&D, investing in entrepreneurs, and boosting the public profile and awareness of carbon removal as a necessary technology.

3) Evergreen Collaborative

What it does: Arising from the ashes of Washington Gov. Jay Inslee’s climate-change-focused 2020 presidential campaign, the Evergreen Collaborative is a new advocacy organization that functions as a bridge between environmental organizations and the US federal government.

Evergreen includes some of the most prominent scientists and policymakers working for better climate policy and environmental justice, and they seek to leverage their experience and network to push for key energy and climate provisions in the Biden administration’s executive orders and Congress’s legislative agenda.

Why you should consider donating: Despite being a young, small organization, the Evergreen Collaborative has punched well above its weight in the past year (a crucial moment for the federal government to enact climate legislation, given that Democrats are in control). The group co-developed and advocated for the Clean Electricity Performance Program (CEPP), which became a central pillar of the Biden administration’s climate agenda. Though that program has unfortunately been scrapped from the legislation, that it was a fixture in the climate policy discourse is suggestive of Evergreen’s effectiveness at pushing ideas at the federal policymaking level.

4) Rainforest Foundation US

What it does: Rainforest Foundation US works to protect the rainforests of Central and South America by partnering directly with those on the front lines: Indigenous peoples in Brazil, Peru, Panama, and Guyana, who are deeply motivated to protect their lands. The foundation supplies them with legal support as well as technological equipment and training so they can use smartphones, drones, and satellites to monitor illegal loggers and miners, and take action to stop them.

Why you should consider donating: Rainforest Foundation US has shown an unusual commitment to rigorous evaluation of its impact by inviting Columbia University researchers to conduct a randomized controlled trial in Loreto, Peru. Starting in early 2018, researchers collected survey data and satellite imagery from 36 communities partnered with the foundation and 40 control communities.

The results were published this year — and they’re encouraging. The program reduced tree cover loss, and the reductions were largest in the communities most vulnerable to deforestation (along the deforestation frontier).

So much of the donor money going into the climate fight gets poured into efforts within the US and EU; it may make sense to divert some of that money to efforts in key ecosystems like the Amazon rainforest, on which the global climate depends. Given that the past couple of years have seen massive fires and a surge of deforestation there, now seems like an especially good time to directly support the Indigenous peoples who are holding the front lines for all of us.

5) Sunrise Movement Education Fund

What it does: The Sunrise Movement Education Fund is the 501(c)(3) arm of the Sunrise Movement, a youth activist organization. Activism is an important piece of the climate puzzle; in addition to pushing leaders to keep prioritizing climate, activists can shift the Overton window, the range of policies that seem possible.

Of course, some activist groups are more effective than others. Stein, the director of Giving Green, told Vox in 2020 that the Sunrise Movement Education Fund is extremely effective, not least because it “has the ear of the Biden administration. ... They’ve gotten that seat at the table.”

Why you should consider donating: Giving Green recommended this nonprofit last year, noting: “Sunrise Movement Education Fund played a central role in building a strong coalition of politicians, activists, and researchers to coalesce around a policy framework generally known as ‘Standards, Investment, and Justice.’ This framework has been adopted by the House Select Committee on Climate Change and is integrated into the Biden administration’s climate plan.”

Although Sunrise isn’t on Giving Green’s recommended list this year, Stein told Vox that’s largely because the nonprofit hasn’t yet made public its plans for 2022 and it’s better-funded than it used to be; after learning more about its plans, Giving Green may again recommend it in 2022. In the meantime, it still looks like a good bet.

6) Climate Emergency Fund

What it does: The Climate Emergency Fund (CEF) was founded in July 2019 with the goal of regranting money to groups engaged in climate protest — and fast. Its founders believe that street protest is crucially important to climate politics and neglected in environmental philanthropy. This year alone, CEF has given over $1.35 million in grants to 33 groups and projects it has vetted. Grantees include Extinction Rebellion, an activist movement that uses nonviolent civil disobedience — like filling the streets and blocking intersections — to demand that governments do more on climate. (Disclosure: Muizz donated to Extinction Rebellion DC in 2021.)

CEF was the lead institutional funder of the Climate Emergency Declaration campaign, which led to over 2,000 national and local governments declaring a climate emergency. More recently, CEF funded the Hunger Strikers for Climate Justice, whose participants fasted in front of the White House this fall to demand the Biden administration pass certain climate measures.

Why you should consider donating: Social change is not an exact science, and the challenges in measuring a social movement’s effectiveness are well-documented. While it would be helpful to have more concrete data on the impact of CEF’s grantees, it may also be shortsighted to ignore movement-building for that reason.

Bill McKibben, co-founder of 350.org, told Vox that building the climate movement is crucial because, although we’ve already got some good mitigation solutions, we’re not deploying them fast enough. “That’s the ongoing power of the fossil fuel industry at work. The only way to break that power and change the politics of climate is to build a countervailing power,” he said. “Our job — and it’s the key job — is to change the zeitgeist, people’s sense of what’s normal and natural and obvious. If we do that, all else will follow.”

If you’re skeptical that street protest can make a difference, consider Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth’s research. She’s found that if you want to achieve systemic social change, you need to mobilize 3.5 percent of the population, a finding that helped inspire Extinction Rebellion.

7) TerraPraxis

What it does: TerraPraxis is a nascent UK-based nonprofit aiming to find innovative ways to meet the globe’s growing energy needs, with a special focus on advanced nuclear power, which is neglected in the climate funding landscape. The data shows that nuclear power is safer than you might think. It’s a clean energy source that’s already been scaled up fast to decarbonize electricity systems in countries like Sweden and France; going forward, it could help ensure that people in developing countries have enough energy to meet their needs.

Why you should consider donating: TerraPraxis is a very small, young organization, so it doesn’t have much of a track record yet. But Founders Pledge recommends it, arguing that more funding would enable it to reach its full potential. “We believe that TerraPraxis continues to do incredibly important work around shaping a conversation for advanced nuclear to address critical decarbonization challenges, such as the decarbonization of hard-to-decarbonize sectors and the conundrum of how to deal with lots of very new coal plants that are unlikely to be prematurely retired,” write Johannes Ackva and Luisa Sandkühler in their report for Founders Pledge.

Aside from donating, there are many other ways you can help

It’s worth noting that there are plenty of ways to use your skills to combat climate change. And many don’t cost a cent.

If you’re a writer or artist, you can use your talents to convey a message that will resonate with people. If you’re a religious leader, you can give a sermon about climate and run a collection drive to support one of the groups above. If you’re a teacher, you can discuss this issue with your students, who may influence their parents. If you’re a good talker, you can go out canvassing for a politician you believe will make the right choices on climate.

If you’re, well, any human being, you can consume less. You can reduce your energy use, how much stuff you buy (did you know plastic packaging releases greenhouse gases when exposed to the elements?), and how much meat you consume.

Research shows that it’s very difficult to “convert” people to vegetarianism or veganism through information campaigns, which is one reason we did not recommend donating to such campaigns (there are more cost-effective options). But now that you can get Impossible Whoppers and Beyond Burgers delivered right to your door, you can easily transition to a more plant-based diet without sacrificing on taste. Individual action alone won’t move the needle much — real change on the part of governments and corporations is key — but your actions can influence others and ripple out to shift social norms, and keep you feeling motivated rather than resigned to climate despair.

You can, of course, also volunteer with an activist group — whether it’s Extinction Rebellion, the Sunrise Movement, or Greta Thunberg’s Fridays for Future — and put your body in the street to nonviolently disrupt business as usual and demand change.

The point is that activism comes in many forms. It’s worth taking some time to think about which one (or ones) will allow you, with your unique capacities and constraints, to have the biggest positive impact. But at the end of the day, don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good: It’s best to pick something that seems doable and get to work.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment