Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s promises to curb civilian casualties are as empty as the military’s vows to stop sexual harassment.

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin — after months of news reports about civilians killed by U.S. bombs, including the deaths of seven children and three adults in a Kabul drone attack — just issued a directive to reduce what the military traditionally describes as collateral damage. “We can and will improve upon efforts to protect civilians,” Austin vowed this week. “The protection of innocent civilians in the conduct of our operations remains vital to the ultimate success of our operations, and as a significant strategic and moral imperative.”

His two-page directive calls for the creation of a “Civilian Harm and Mitigation Response Plan” in 90 days that will lay out a comprehensive approach to improve the training of military personnel and the collection and sharing of data, so that the wrong people don’t get killed so often. He also ordered the establishment of a hazily defined “civilian protection center of excellence” to institutionalize the knowledge needed to prevent wrongful killings. The underlying idea is that military culture will be changed so that protecting civilians is a core goal.

If you were just tuning into the catastrophe of America’s forever wars, you might be impressed by Austin’s directive, in the same way you might be impressed by Capt. Louis Renault in “Casablanca” when he shuts down Rick’s Café because, shockingly, gambling was happening in the casino. Renault’s horror was feigned, of course. He was a regular visitor to the cafe, and after blowing his whistle on gambling, he was handed his winnings for that night.

It’s not as though the Pentagon is taking action — or pretending to take action, as is much more likely — because battlefield abuses have suddenly been brought to its attention. From the beginning, one of the hallmarks of the post-9/11 wars has been the widely reported killing of civilians by U.S. forces. These things have been revealed in exhaustive detail year after year by generations of journalists (I even did a bit of it during the Iraq invasion), as well as nonprofit organizations and military whistleblowers like Chelsea Manning and Daniel Hale.

There has even been a begrudging chorus of admissions by the Pentagon that go back more than a decade. In 2010, the Joint Chiefs of Staff completed its classified “Joint Civilian Casualty Study.” In 2013, a Pentagon office called Joint and Coalition Operational Analysis published a report titled “Reducing and Mitigating Civilian Casualties: Enduring Lessons.” The remarkable thing about that 2013 report — other than the fact that it included most of the remedies Austin mentioned this week — was that it contained a list of a dozen other reports on civilian casualties that JCOA alone had published in the previous five years.

And five years later, in 2018, the Joint Chiefs completed yet another classified report on civilian casualties. The Washington Post, which revealed its existence, described that report as “a major examination of civilian deaths in military operations, responding to criticism that [the Pentagon] has failed to protect innocent bystanders in counterterrorism wars worldwide.” Sound familiar? And that secret report came two years after President Barack Obama had issued an executive order that said the military was killing too many civilians and needed to take a range of actions to change that.

You get the point. The Pentagon’s protestations of disappointment at what has happened, and its promises to do better, are the standard confetti of insincerity. In many ways, it’s similar to executives at Facebook expressing dismay and regret at some of the ways their platform has been used and abused, and promising to do a better job. The important thing to watch is not what powerful institutions promise to do but what they actually do. And when they do nothing after promising again and again to make changes, you would be foolish to regard their latest vow as meaningful.

“While a serious Defense Department focus on civilian harm is long overdue and welcome, it’s unclear that this directive will be enough,” noted Hina Shamsi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s national security project. “What’s needed is a truly systemic overhaul of our country’s civilian harm policies to address the massive structural flaws, likely violations of international law, and probable war crimes that have occurred in the last 20 years.”

The best template for understanding the endurance of the Pentagon’s failures on civilian casualties might be its record on curbing sexual abuse in its ranks. This is a problem that has existed forever but jumped into the public realm in a particularly strong way with the 1991 Tailhook scandal, when 83 women and seven men were sexually assaulted at a Navy conference in Las Vegas. Since then, the military has continually promised to do everything it could to fight sexual abuse. There has been no shortage of studies and plans and hearings, but the problem persists, with nearly one in four servicewomen reporting sexual assault in recent studies, and more than half reporting sexual harassment.

There is now hope of real change after Congress finally passed legislation in December that transfers to independent military prosecutors the authority to pursue sexual assault cases. Under an executive order signed by President Joe Biden this week, sexual harassment has also been added as a crime to the Uniform Code of Military Justice. These moves came more than three decades after Tailhook.

It would be good if we could save ourselves another decade or two of insincere Pentagon reports and jump forward to the day when commanders no longer have the ability to protect their subordinates, and themselves, by standing in the way of prosecutions after civilians are recklessly killed. (There was no disciplinary action taken against any soldier after the Kabul drone bombing, for instance.) But that day is probably a long way off, especially when the current defense secretary is a former general who for many years commanded U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the meantime, there is one thing Biden could do that would show the government is just a little bit serious about reducing civilian casualties. Daniel Hale, who pleaded guilty to leaking classified military documents that revealed the scale of civilian killings by U.S. drones, is currently serving a 45-month sentence for violating the Espionage Act. He should be pardoned, to demonstrate that it was terribly wrong to punish someone who tried to stop the murder of innocent people.

“I stole something that was never mine to take — precious human life,” Hale said at his sentencing. “I couldn’t keep living in a world in which people pretend that things weren’t happening that were. Please, your honor, forgive me for taking papers instead of human lives.”

Demonstrators with Witness Against Torture march in front of the US supreme court in Washington DC on 27 May 2008 protesting that the rights and humanity of Guantánamo Bay detainees be respected. (photo: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images)

Demonstrators with Witness Against Torture march in front of the US supreme court in Washington DC on 27 May 2008 protesting that the rights and humanity of Guantánamo Bay detainees be respected. (photo: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images)

Calls mount for release of full Senate report on the torture of Abu Zubaydah, to counter a narrative too many Americans still believe – that torture works

A government lawyer addressed the panel, arguing on grounds of “state secrets” that Zubaydah should be blocked from calling two CIA contractors to testify about the brutal interrogations they put him through at a hidden black site in Poland. Within minutes of his opening remarks, the lawyer was interrupted by Amy Coney Barrett, one of the rightwing justices appointed to the court by Donald Trump.

Barrett wanted to know what the government would do were the contractors to give evidence before a domestic US court about how they had “waterboarded” Zubaydah at least 83 times, beat him against a wall, hung him by his hands from cell bars and entombed him naked in a coffin-sized box for 266 hours. “You know,” she said, “the evidence of how he was treated and his torture.”

“Torture.”

Barrett said the word almost nonchalantly, but its significance ricocheted around the courtroom and far beyond. By using the word she had effectively acknowledged that what was done by the CIA to Zubaydah, and to at least 39 other “war on terror” detainees in the wake of 9/11, was a crime under US law.

After Barrett uttered the word the floodgates were opened. “Torture” echoed around the nation’s highest court 20 times that day, pronounced by Barrett six times and once by another of Trump’s conservative nominees, Neil Gorsuch, with liberal justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan also piling in.

The flurry of plain speaking by justices on both ideological wings of the court amazed observers of America’s long history of duplicity and evasion on this subject. “The way the supreme court justices used the word ‘torture’ was remarkable,” Andrea Prasow, a lawyer and advocate working to hold the US accountable for its counterterrorism abuses, told the Guardian. “You could feel the possibility that the ground is shifting.”

Prasow was astonished a second time three weeks later when Majid Khan, a former al-Qaida courier also held in Guantánamo, became the first person to speak openly in court about the torture he suffered at a CIA black site.

Khan’s description of being waterboarded, held in the nude and chained to the ceiling to the point that he began to hallucinate was so overpowering that seven of the eight members of his military jury wrote a letter pleading for clemency for him, saying his treatment was a “stain on the moral fiber of America”.

The ground does appear to be shifting, and as it does attention is once again falling on one of the great unfinished businesses of the 21st century: the US torture program. In the panicky aftermath of 9/11, when the world seemed to be imploding, the CIA took the view that the ends – the search for actionable intelligence to thwart further terrorist attacks – justified any means.

With the enthusiastic blessing of the justice department and George W Bush’s White House, the CIA abandoned American values and violated international and US laws by adopting callous cruelties that they consciously copied from the enemy.

They took one prisoner, Abu Zubaydah, and made him their experimental guinea pig. On Zubaydah’s back they built an entire edifice of torture – “enhanced interrogation techniques” as the bloodless euphemism went – that in turn was founded upon a mountain of lies. When the worst of the torture was completed, to spare themselves from possible prosecution the CIA insisted that Zubaydah remain “in isolation and incommunicado for the remainder of his life”.

“The torture program was designed for only one person – they gave him a name and that name was Abu Zubaydah,” Mark Denbeaux, Zubaydah’s lead habeas lawyer, told the Guardian. “After they tortured him, they demanded that he be held incommunicado forever so that his story could never be told. Since that moment the only people he has ever spoken to are his torturers, his jailers, and his lawyers, including me.”

Twenty years after Zubaydah was waterboarded, slammed repeatedly against a wall, sleep-deprived, face slapped, chained in painful stress positions, hosed with freezing water, stripped naked, and blasted with deafening noise, his story still has not fully been told. In 2014 the Senate intelligence committee released a heavily redacted, 500-page executive summary of its seven-year investigation into the torture program, generating headlines around the world and leading Barack Obama to conclude that “these harsh methods were not only inconsistent with our values, they did not serve our national security”.

Yet at the insistence of the CIA the full report from which the summary was drawn remains under lock and key to this day. All three volumes of it. All more than 6,700 pages. All 38,000 footnotes. All the detail distilled from 6.2m pages of classified CIA documents.

The persistent refusal to release the full Senate torture report has left a black hole at the centre of one of the most shameful episodes in US history. Now, with the T-word being heard even in the hallowed halls of the US supreme court, renewed calls are being made for the report to be published so that this sorry chapter can finally be closed.

Several of the individuals most closely involved in the battle for the truth over Abu Zubaydah’s treatment have told the Guardian that 20 years is long enough. It is time for the American people to be told the full unadulterated facts about what was done in their name.

“More than seven years after the completion of the torture investigation, it remains critically important that the public see the full report,” said Ron Wyden, the Democratic senator from Oregon who was an important advocate for the Senate investigation and who played a critical role in ensuring that at least some of its findings have emerged into daylight.

Wyden called for a full accounting of the CIA’s handling of detainees. He said a wealth of information still shrouded in secrecy would confirm that the torture program was ineffective – it simply didn’t work.

“The withholding of the full report, and the redactions in the public executive summary, have hidden from the public the story of how the program was developed and operated. Understanding how all of this happened is important because it must never happen again.”

Daniel Jones, the chief author of the US Senate report, said that now was the moment for its release. “The country is ready. It’s what you do in a transparent democracy: when you mess up you admit it and you move on as a better country. We’ve reached that point now.”

Abu Zubaydah, 50, (actual name Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn) is a Saudi-born Palestinian who was one of the CIA’s “high-value” targets in the wake of 9/11. He was captured in Faisalabad, Pakistan, on 28 March 2002 in a raid in which he was shot several times including in the thigh and groin. He later lost his left eye while in US custody in unexplained circumstances.

John Kiriakou, a former CIA counter-terrorism officer, was a leading member of the team that seized Zubaydah, sitting guard at the prisoner’s bedside after the raid. Though Kiriakou did not participate in the prisoner’s subsequent interrogations at secret black sites in Thailand, Poland, Lithuania and other countries, he continued to keep tabs on his captive.

In December 2007, having by then left the CIA, Kiriakou gave an interview to NBC News in which he became the first former government official publicly to state that Zubaydah had been waterboarded – the process where a cloth is placed over a detainee’s face and water poured over it as a form of controlled drowning. Kiriakou declared that he had come to view the procedure as torture.

Kiriakou’s comments marked the first chink in the wall of official silence surrounding the CIA’s abuses. The move displeased his former employers and he was made the subject of a leak inquiry that ended in a sentence of 23 months in a federal penitentiary – he is convinced as an act of revenge – ostensibly for having revealed the identity of a covert CIA agent to a journalist.

Unbeknownst to him at the time, Kiriakou in fact gave erroneous information in his NBC News interview. He said Zubaydah had been waterboarded only once and that the detainee had instantly cracked, divulging good actionable intelligence in less than a minute.

In fact, the prisoner was waterboarded not once but at least 83 times over more than a month. After the torture began in earnest at “detention site green” in Thailand in August 2002, the CIA gleaned no valuable information from Zubaydah whatsoever.

Kiriakou told the Guardian that his remarks to NBC had been based on what he picked up at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. “This was all a lie and we didn’t know it was a lie until it was declassified in 2009. So on top of being illegal, unethical and immoral, it was also false.”

To Kiriakou, the supreme court’s ease with the word “torture” 14 years after he used it for the first time on network television is “vindication that it was wrong”. He said he was dismayed that the CIA continues to cover up its “barbaric crimes” by resisting release of the full Senate report, likening the study to the defense department’s internal account of the Vietnam war that changed the course of history when it was leaked in 1971.

“We knew a lot about what was happening in Vietnam but we didn’t have official government confirmation until Daniel Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers. It’s the same here. We have had some testimony from torture victims but we don’t have official confirmation of what the CIA did from the CIA itself, and that’s what release of this report would do.”

The lies to which Kiriakou fell foul were intrinsic to the torture program from its inception. Zubaydah was used as the prototype for a new type of “enhanced interrogation” that crossed the line into torture.

In April 2002 a pair of psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, were brought on board by the CIA on contract to create the program. They based the plan partly on experiments on dogs that found if you hurt and humiliated the animals sufficiently, eventually they would stop resisting – “learned helplessness” as it was known in the trade. (At least in this regard the torture program proved successful – Zubaydah did reach such a place of helplessness. It got to the point that as soon as an interrogator snapped his fingers twice, the detainee would lie flat on the waterboard and wait supinely for the controlled drowning to begin.)

The psychologists, whom the CIA paid more than $80m for their efforts, consciously modeled their interrogation methods on the so-called SERE training of American soldiers on how to resist torture were they to fall into enemy hands. The contractors openly adopted the enemy torture techniques, without irony, despite the fact that the methods were designed to extract propaganda statements from US prisoners of war and not accurate intelligence.

Senior CIA officials knew that they faced an uphill battle in persuading the Department of Justice that what they planned to do was legal – after all torture was categorically prohibited under the 1949 Geneva Conventions that the US had ratified. So they presented the DoJ with a “psychological assessment” of Zubaydah justifying why he needed to be made to talk using aggressive interrogation methods, warning that “ countless more Americans may die unless we can persuade Zubaydah to tell us what he knows”.

It was all a smorgasbord of lies. “The reasons they gave for why he had to be tortured were false and known to be false,” Denbeaux said.

“The justice department was duped into approving the torture of a man who was never a member of al-Qaida. They said he was number two, three or four of al-Qaida – not true. They said he was part of 9/11 – laughable and not true. They said he was part of all al-Qaida operations around the world – totally untrue.”

Denbeaux added that one of the most urgent arguments in favour of releasing the full Senate report was that it would expose the lies at the core of the program. “It would show in detail how the falsity was made up, and who in the CIA put these false facts together.”

Zubaydah’s psychological profile was not the only aspect of the untruths that formed the building blocks of the torture program. The CIA was also misleading about the efficacy of “enhanced interrogation techniques”.

Ali Soufan has personal knowledge of how distorted the official CIA account was. A former FBI special agent, he was one of the first US officials to interrogate Zubaydah at a black site.

He did so using conventional interrogation methods that would be familiar to students of Law & Order. He learned everything he could about his subject, spoke in the prisoner’s own language (Arabic), built up a rapport with Zubaydah, and played mind games on him such as giving him the impression that the FBI knew much more about his activities than in fact they did.

All without recourse to force, violence or humiliation. “We did not need torture to get information,” Soufan told the Guardian.

Soufan and his FBI partner succeeded in securing Zubaydah’s cooperation and extracting significant intelligence from the prisoner, including the central role played by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed as the architect of 9/11. Even so, they were abruptly pulled off the job and replaced by the CIA contractors armed with a very different approach.

Soufan watched aghast as CIA operatives, under the instruction of Mitchell and Jessen, began to torture the prisoner. “At the beginning it was mostly loud music,” Soufan said. “He was held naked in the cell. That shocked me at the time. It was stupid, why are we doing it, the guy is already giving information. And then it evolved, one step after another.”

Starting at 11.50am on 4 August 2002, Zubaydah was tortured through a variety of methods, almost 24 hours a day, for 19 days without break. After a waterboarding session he was noted to have “involuntary leg, chest and arm spasms” and to be unable to communicate. On one occasion he became “completely unresponsive, with bubbles rising through his open, full mouth”.

Given Zubaydah’s incommunicado status, he has never been allowed to recount his experiences directly to the American people. But over the years his lawyers have managed to put together notes in which the Guantánamo detainee describes his abuse.

Excerpts of those notes, together with some of Zubaydah’s drawings that he sketched from memory in Guantánamo that illustrate his treatment at the CIA black sites, are being published by the Guardian. They amount to a harrowing account in Zubaydah’s own words and images of the relentless, round-the-clock, prolonged and illegal abuse he suffered.

Soufan, who is now CEO of the Soufan Group, said the release of the full Senate report is essential to counter the CIA narrative, which he fears that too many Americans still believe – that torture works. “Most of the American public believe the Hollywood version: you beat someone up, they give you the information you want, you save lives.”

Soufan added: “Release the full Senate report and you will see that the CIA shaped a false narrative. The torture did not work, it did not produce information that saved lives, it did hinder our counterterrorism operations and destroy our image and reputation around the world.”

Soufan’s own experiences give some hope that the full Senate report might one day be made public. When his book on the war of terror, The Black Banners, was published in 2011 it was so heavily redacted by the CIA that he even had to black out any reference to himself including the words “I”, “me”, “our” and “we”.

It took him a legal battle lasting nine years, but in 2020 he was finally able to bring out a declassified edition. Soufan hopes that the softening attitude of CIA chiefs towards his book bodes well for an eventual release of the Senate report.

“The CIA is now a very different organization from what it was in 2002. The people who were directly involved in the torture program, they are all out and there is a new leadership who understand the impact of all this.”

Kiriakou is more pessimistic about a CIA change of heart: “For the next 100 years the CIA will do anything it can to stop that report being made public.”

The Guardian asked the CIA whether it had plans to revisit the question of whether the report could be published, and invited the agency to comment. It did not immediately respond.

For all the uncertainty about the CIA’s intentions, calls for release of the full Senate report are growing. Prasow said that the US will find it all but impossible to close Guantánamo without grappling with the torture issue first.

“The public has been sold a false story that torture victims were somehow less deserving of human rights protections. For far too long it’s been too easy to see torture victims as ‘other’. It’s time to bring them out into the light.”

Denbeaux, Zubaydah’s lawyer, said that releasing the report would help fill in some of the void that was left in 2005 when the CIA destroyed videotapes of the torture of Zubaydah. “In the absence of the destroyed footage, the full Senate report would bring home to the American people the cumulative horror of how the torture worked, day after day, hour after hour, continuously, endlessly. This was a hideous awful thing, and they’d like us to forget about it?”

Jones, the report’s chief author, said that were it to emerge in its totality it would “shut the book and remove any lingering doubts” – about the torture, about its ineffectiveness, and about the lies that were told. “There are so many examples in it of the CIA misleading Congress, the White House, the public.”

Among the items still waiting to be revealed is a photograph that has never been made public that Jones and his team discovered of a waterboard that was stored at the notorious “Salt Pit”, a black site outside Bagram airbase in Afghanistan. The device appeared extremely well used, and in the photo it is seen surrounded by buckets of water and bottles of a peculiar pink solution.

The photograph puzzled Jones and his team of investigators because there were no official records to indicate that waterboarding had ever been practiced at the Salt Pit. When the Senate team asked the CIA to explain the photograph, the agency said it had no answer.

In the last analysis, Jones said that it all points to a massive failure of accountability – a failure that until the full report is made public will continue to gnaw away at the nation’s standing and self-respect. “We’ve failed at every level of accountability – criminal, civil and societal,” he said. “If this is never to happen again, there has to be a reckoning.”

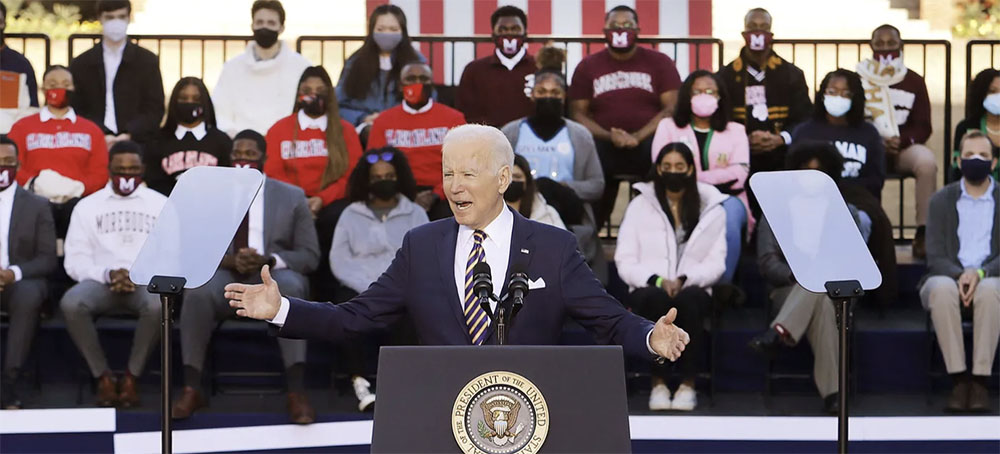

Biden delivers a speech on voting rights on the campuses of Clark Atlanta University and Morehouse College in January 2022. (photo: Erik S Lesser/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock)

Biden delivers a speech on voting rights on the campuses of Clark Atlanta University and Morehouse College in January 2022. (photo: Erik S Lesser/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock)

Although Biden has lost ground with most every demographic group, he’s suffered especially steep losses with African American voters. In polling from NBC News, Biden’s approval rating among Black voters has fallen from 83 percent last April to 64 percent today. Quinnipiac University’s surveys show a similar trend, with Biden’s Black support dropping from 78 percent to 57 percent over the course of his first year in office.

Much of that erosion has come in just the last few months. A Pew Research survey released this week finds that Biden has bled seven percentage points of support among Black adults since September. Over that same period, the president lost just four points of support from whites, and virtually none from Asian or Hispanic voters.

For half a century, Black voters have been among the most reliably Democratic constituencies in the country. Thus, the fact that Biden’s rising disapproval has been concentrated within the demographic demands explanation.

Many outlets have attributed the president’s woes to his failure to enact racial-justice legislation in general, and a voting-rights law in particular. As Bloomberg reported last week, “The sudden collapse of voting-rights legislation this week is emerging as the final straw for Black voters with President Joe Biden.” Politico echoed this assessment Thursday morning: “The defeat of the voting-rights bill last week was a final straw for many voters of color disenchanted with the lack of action on that issue as well as on police reform.”

This explanation is intuitive. Civil-rights groups and African American community organizations have made voting-rights and criminal-justice reform focal points of their lobbying on Capitol Hill. Black congressional leaders have made the former a top priority. And there’s little question that voting rights are of special concern to Black voters.

This is especially true in Georgia, the Deep South’s lone blue state and ground zero for Donald Trump’s “Stop the Steal” campaign. In an Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll released Thursday, 24 percent of Georgia voters named “elections/voting” as their most important issue. No other subject was a top priority for quite as many Georgians. And concern about election reform was higher among Black Georgians than among the general population, with 31 percent of the former naming it as their top issue. The same AJC poll found that Biden’s disapproval rating among African Americans in the Peach State had risen from 8 percent in May 2021 to 36 percent today. It’s plausible that Biden’s inability to get voting rights over the finish line is responsible for some part of that great increase.

At the national level, however, there’s reason to suspect that Biden’s defunct democracy agenda is less central to his declining Black support than is commonly presumed.

For one thing, available polling suggests that across America as a whole, the push for voting rights has only limited salience. When Gallup asked U.S. voters to name their nation’s “most important problem” in December, only one percent said “elections” or “election reform.” In a recent poll from the Democratic firm Navigator Research, only 21 percent of Black respondents said that they had “heard a lot” about the Democrats’ main voting-rights proposal, the Freedom to Vote Act. Further, in Quinnipiac’s recent poll, Black voters were actually much less likely than white or Hispanic voters to agree with the statement, “the nation’s democracy is in danger of collapse.”

For another thing, Biden’s erosion of support among Black voters far predates the voting-rights push’s latest failure. In fact, we still don’t have much polling conducted after Democrats failed to come up with the votes necessary to pass the Freedom to Vote Act in defiance of a Republican filibuster this month. Quinnipiac’s survey, which showed Biden’s Black support at a disastrous 57 percent, was largely taken during a period when the president was treating voting rights as his top legislative priority.

There are other explanations for Biden’s difficulties with Black voters that have stronger empirical support. Chief among these is the unpopularity of his vaccine-mandate policy with a small but significant minority of Black Democrats.

Morning Consult’s national tracking poll shows a stark inflection point in Biden’s Black support immediately after the announcement of the mandate. Between September 8 (the day before the mandate’s rollout) and September 20, Biden’s support among Black voters fell by 12 percentage points in the survey. One might write this off as a coincidence, had the pollster not specifically monitored Biden’s standing with unvaccinated Black voters — and found that he had lost 17 points with that segment of the electorate over those two weeks.

As noted above, a post-September decline in Biden’s Black support has been captured in other polls. And there is no analogous inflection point (yet) showing a similar decline in the immediate aftermath of a legislative setback on voting rights.

That Biden’s vaccine mandate would hurt his Black approval more than his failure to deliver on voting rights makes some sense. Generally speaking, presidents are most vulnerable to losing the support of marginal members of their party, which is to say, those who are least firmly attached to their coalition. Marginal Democrats are atypical Democrats, by definition. Relative to strong partisans, marginal Democratic voters tend to hold more heterodox issue positions and to pay less attention to political news. And voters who don’t follow politics closely can quite easily remain unengaged by (if not oblivious to) fights over the details of election law. In most cases, if a pollster classifies you as a “voter,” then you have successfully cast a ballot in a recent election. Which means that, for you personally, disenfranchisement is unlikely to be experienced as a clear and present threat. And in any case, in the time between elections, changes in voting law are unlikely to impinge upon your daily life.

By contrast, vaccine mandates meet low-information voters where they are. If you are a vaccine-averse Black Democrat, Biden’s mandate effectively forced you — or at least, before it was struck down, threatened to force you — to do something you did not want to do in order to keep your job. That is not the kind of policy that is easily ignored. And it is not hard to imagine how a voter with little trust in public authority might revise their political allegiances when their president tries to coerce them into taking a medical treatment they don’t want.

None of this is to say that Biden’s vaccine mandate was not a worthwhile policy on the merits (it was). Nor is it even to assert that the mandate was bad politics; my reading of the polling suggests that they probably gained him about as much goodwill as they cost him. But because Black voters are overwhelmingly concentrated within the Democratic Party — and therefore not politically sorted by their attitudes toward meritocratic expertise, collective responsibility, or trust in government to the same extent that white voters are — a small minority of Black Democrats are vaccine skeptics. And Biden’s mandate appears to have alienated much of this contingent.

Another issue that makes itself felt to Black voters, whether or not they pay attention to goings-on in D.C., is inflation. For months now, polls have indicated that rising prices are a top concern for the electorate as a whole, and that voters overwhelmingly disapprove of Biden’s handling of the matter. Black voters appear to be roughly as concerned about the issue as the general public. In a Morning Consult poll from November, 50 percent of African American voters said that they were “very concerned” about inflation. By contrast, only 37 percent said that they were very concerned about “conflict between political parties.” In the same survey, 54 percent of Black voters said that “the Biden administration’s policies” were responsible for inflation.

African Americans are overrepresented on the lower rungs of our nation’s socioeconomic ladder. And polling indicates that lower-income Americans are more alarmed by inflation than high-income ones. An AP-NORC poll from December found that, among Americans with household incomes of less than $50,000 a year, half say price increases have had “a major impact on their finances,” while only a third of those with household incomes above $50,000 say the same. A Gallup poll released at roughly the same time yielded similar results, with 71 percent of households earning under $40,000 reporting that inflation was causing them severe or moderate hardship, while only 29 percent of households earning more than $100,000 said the same.

Finally, even before Biden took office, there was reason to believe that Democrats were poised for a gradual, long-term decline in Black support. In 2018 House races, Democrats actually won a smaller share of the African American vote than they had in the 2016 presidential election — even as the party’s overall popular-vote edge in the midterm was five points higher than Hillary Clinton’s two years earlier.

Remarkably, this very slight right turn among Black voters showed up even in Georgia’s gubernatorial race, which pitted the African American minority leader of the state’s House of Representatives, Stacey Abrams, against a secretary of State complicit in voter-suppression efforts. According to the Democratic data firm Catalist, Abrams’s share of the state’s Black vote in 2018 was four percentage points lower than Hillary Clinton’s in 2016.

In 2020, this pattern of very slight Democratic underperformance with Black voters continued, at least in Catalist’s data. Looking at the two-way vote between the Democratic and Republican nominees in each election, Democrats won 97 percent of the Black vote in 2012, 93 percent in 2016, and 90 percent in 2020.

These changes are small enough to dismiss as random variation. But there is a theoretical basis for expecting the Democratic Party’s share of the African American vote to erode over the coming decade. Keeping 90-plus percent of any subgroup united in one partisan camp takes work. The reason Democrats have enjoyed such a landslide margin among Black voters — despite considerable ideological and attitudinal diversity within that demographic — is not that each individual African American Democrat concluded that the GOP was hostile to people like them through their own personal ruminations on current affairs. Rather, as political scientists Ismail K. White and Cheryl N. Laird argue in their book, Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior, the Black bloc vote is a product of “racialized social constraint” — which is to say, the process by which African American communities internally police norms of political behavior through social rewards and penalties. In their account, the exceptional efficacy of such norm enforcement within the Black community reflects the extraordinary degree of Black social cohesion that slavery and segregation fostered.

If this thesis is correct (and White and Laird do much to substantiate it), then it would follow that the erosion of African Americans’ social isolation would weaken racialized social constraint, and thus narrow the Democratic Party’s margin with Black voters. As White and Laird write:

We believe that increased contact with non-blacks and a decline in attendance at black institutions, in favor of more integrated spaces, would threaten the stability of black Democratic partisan loyalty. The result, we believe, would be a slow but steady diversification of black partisanship because leveraging social sanctions for racial group norm compliance would become much more difficult in integrated spaces.

It remains possible that Biden’s failure to deliver legislative breakthroughs on voting rights and police reform have hurt him badly with the Black electorate. In any case, action on both of those issues is morally imperative.

But the widespread sense that the president’s legislative impotence on racial-justice issues is at the heart of his Black voter problem lacks strong empirical support. It seems to derive largely from the analysis of African American politicians, community leaders, and activists. These figures may well represent the views of the typical Black Democrat, but they are generally much more uniformly liberal and politically engaged than the marginal Black Democrat, whose support is most easily lost.

Further, since Black political organizations often find themselves to be the sole advocates for issues that concern African Americans specifically, they are understandably keen to emphasize such issues. Yet it is one thing for an issue to be more important to a minority group than it is to the general public, and another for an issue to be more important to a minority group than other, non-racially-coded issues. It is true that immigration policy tends to be more important to foreign-born Americans than it is to the median voter. But that does not necessarily mean that immigration policy is more important to foreign-born Americans than their wages or cost of living or other matters that tend to be high-salience issues for voters of every stripe. And the same is true of voting rights and African Americans. As the Democratic pollster Brian Stryker recently told the New York Times, “The No. 1 issue for women right now is the economy, and the No. 1 issue for Black voters is the economy, and the No. 1 issue for Latino voters is the economy.” It is possible that Striker’s analysis is mistaken. Either way, only by seeing nonwhite voters as members of minority groups first — and people second — can we assume that their primary concerns depart from those of the public writ large.

None of this is to suggest that Democrats or the press should ignore the political analysis of civil-rights organizations and Black activist groups. These institutions have better insights into the formal obstacles to Black political participation than any polling outfit. And it is quite plausible that such groups will have a harder time mobilizing solidly Democratic African American voters ahead of this year’s midterms if the party fails to deliver on voting rights, criminal-justice reform, or other racial-justice imperatives.

But it is also important to understand where Biden is most vulnerable to Black defections — namely, within the subset of Black voters who strongly identify with neither the Democratic Party nor African American community organizations. How to best retain the sympathies of this ideologically heterogeneous and disorganized contingent is not obvious (other than, say, “simply increase real wages”). But any viable strategy for stanching Biden’s bleeding with such voters will likely begin with the recognition that their priorities and concerns cannot be gleaned from those of highly engaged, ideologically coherent Black Democrats.

Students from Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, watch as the last of their fellow students are evacuated from the school building in April 1999. (photo: Mark Leffingwell/Boulder Daily Camera/AFP/Getty Images)

Students from Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, watch as the last of their fellow students are evacuated from the school building in April 1999. (photo: Mark Leffingwell/Boulder Daily Camera/AFP/Getty Images)

After coming of age in a world wholly unprepared to deal with the aftermath of mass school shootings, an early wave of survivors is now in their 30s and 40s, grappling with the present.

Leam was 7 when a man brought a semi-automatic weapon to Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California, killing five children who were immigrants from Cambodia and Vietnam, and injuring about 30 others. Leam was one of them, shot three times, twice in the buttocks and once in his arm. The shooting took place in 1989. At the time, mass shootings at schools were incredibly rare. Leam couldn’t have known that tragedies like the one he experienced would, a decade later, be a horrible national trend, and that while uncommon, they would only continue, becoming more frequent in the decades after. At the time, he was just a kid, struggling to make sense of what happened.

It wasn’t easy. “My mom, coming from the killing fields of Cambodia and surviving her own trauma, didn’t want to talk about it. I remember asking her certain things about the school shooting,” he said, but “it was traumatizing for her, too.”

The kids who lived through the start of the school shooting era have grown up. Most of them came of age in the late ’90s and the 2000s, when mass shooters started showing up in schools in Pearl, Mississippi; West Paducah, Kentucky; and Springfield, Oregon (though some, like Leam, survived them even earlier). Now adults in their 30s and 40s, many with children of their own, they are navigating a world in which what happened to them was not an anomaly but the beginning of a recurrent feature of American life. As children, they practiced tornado and fire drills at their schools. Because of what happened to them, their kids have active shooter drills, too.

There’s no real guidebook for recovering from what they experienced. What distinguishes the thousands of survivors of the early wave of school mass shootings from those who came after is that they experienced those shootings in a world wholly unprepared to deal with the aftermath. Few got the mental health treatment now considered necessary for survivors of mass violence. As a result, many were left on their own, to process their trauma in the countless years — and school shootings — since.

When Leam came back to school after the shooting, he remembers, a group of Buddhist monks were there to lead a cleansing ceremony in the cafeteria. A therapist used a large teddy bear with a moving mouthpiece to speak to him. He was comforted by it, and by the chance to say that he was afraid of the spirits that he worried might now be haunting the school. Beyond that, he didn’t receive any formal counseling for years.

His experience was not unusual. Missy Jenkins Smith was 15 years old when a classmate opened fire at her high school, in West Paducah, Kentucky, in 1997. Jenkins Smith, who had just left her morning prayer circle, was shot and paralyzed. The shooting at Heath High School was among the first to receive widespread media coverage in the cable news era; three people were killed, and five were injured.

Jenkins Smith received thousands of letters and gifts from well-wishers around the world, which helped her feel supported in her recovery. There were specialists at the hospital who worked with her to adapt to using a wheelchair. But, she said, “I didn’t have anyone who focused on the fact that I saw someone get shot in the head.” Her twin sister, who also survived the shooting, tried group counseling, but the other children in the group were dealing with different problems (a parent making them practice piano when they didn’t want to, for example), which made sharing her own experiences feel absurd.

Instead of seeing a professional, Jenkins Smith and a few of her friends started an informal therapy group, supervised by their guidance counselor. They held sleepovers and created a safe space to talk about their memories. They stopped, 10 months after the incident, when the shooter pleaded guilty but mentally ill and was sentenced. His plea, they felt, seemed like a logical end point.

Even when schools had counselors on hand after a shooting, the survivors often didn’t feel comfortable using them. “I refused to see a counselor,” said Kristen Dare, who was 16 in 2001 when a classmate opened fire at her school in Santee, California. “I refused to talk about it. I didn’t want to open up.” Her peers, she realizes now, were struggling, too. The cultural understanding of mental health was totally different 20 years ago; the importance of seeking professional help wasn’t as widely acknowledged as it is now.

There was also a profound sense of alienation that teenagers felt then, trying to speak with therapists about an experience that was most likely new to them, too: How can I explain this to an adult who has no idea what I’ve been through?

“I only wanted to talk to people who understood. I didn’t want to talk to people who didn’t see what I saw or understand how I felt,” Dare said. “I found it more therapeutic to be among my peers who had the same understanding as me.”

Heather Martin, who survived the Columbine High School shooting in 1999 by hiding in a teacher’s office with her classmates, felt the same way. “I didn’t want to be around people who hadn’t gone through it,” she said.

I wanted to reach out to the adult survivors of school shootings because I have something in common with them. When I was in sixth grade, a student from my school brought a gun to a dance. He killed one of our teachers and wounded three other people. It happened in 1998 — a few months after the shooting in West Paducah, and almost exactly a year before Columbine — at which point our town’s tragedy was swept away in the public consciousness by other, even deadlier acts of violence.

I did not witness the shooting firsthand, but I was standing right next to the dance hall where the shooter was, and had to run and take cover in a concession stand when the shooter came outside with the gun. I crammed in with other students, crouched down on the ground, until an adult came and told us we were safe. Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about what happened, and about other kids who had these experiences. Back then, the phenomenon seemed so new that we didn’t have the language to discuss it. Talking to adult survivors was a chance to learn about their experiences. It was also an opportunity to better understand my own.

Because of my distance from what happened, I’ve never thought of myself as a survivor; to me, it would feel insulting to the students more directly affected. Some of those I spoke with also didn’t recognize themselves as victims who might be in need of help. Each shooting created concentric circles of trauma. Often, the further out someone was, the less justified they felt seeking treatment.

Hollan Holm was in the same prayer circle as Jenkins Smith in West Paducah, and he was shot in the head, though his injuries weren’t life-threatening. In the days following the incident, he remembers thinking that he needed to get back to class sooner than the other students who were more seriously hurt. He was in school again just a few days after the shooting.

Holm and his friend Craig Keene dealt with their injuries in a typical teenage fashion: They made jokes. Of the five students injured who survived the shooting, they were among the least seriously hurt, and dark humor is how they processed it with each other, ranking themselves by the severity of their injuries and teasing each other about it. I spoke to Holm and Keene on the same afternoon in September, and Holm pulled out his 1998 yearbook to read what Keene wrote: “sup number #5 I got an exit [wound]. #4 (craig)”

Keene, though, was unusual among school shooting survivors of the era: He recognized that he was struggling, and sought help. “I had this huge bandage that covered half my neck; it was like a highlighter for ‘the kid who was shot.’ While I had that bandage on, things went really well,” Keene said. “After that came off, people kind of stopped asking and caring, and that’s when things got pretty rough for me mentally. I felt invisible.” He lost interest in sports and had difficulty sleeping — he couldn’t shake the sense that he was still in danger. He doesn’t remember much of the details about those early therapy sessions, but he is certain that they helped.

For Holm, it would be decades before he sought treatment. “I guess I wasn’t injured enough to justify going to a trauma counselor, which is just kind of insane and sad,” Holm said, reflecting on his attitude at the time. He remembers going to see his pastor once to discuss it. “It was really grossly inadequate. That’s what you get when you let a 14-year-old boy lead his own mental health response to a crisis.”

Jenkins Smith doesn’t remember there being much conversation about what happened outside of her group. She got a sense of why when she connected with classmates at her 20-year high school reunion. “They felt like for them to have a problem was ridiculous because there were people that were worse than them.” Jenkins Smith felt tremendous sympathy for them, and then she felt something unexpected. “I felt kind of lucky,” she said. “Because I was a victim, because I was injured, it did give me that ticket to heal.”

Each survivor was trying to make sense of an experience with mass tragedy with a brain that was still developing. They’d spend years processing and reprocessing the trauma as they got older. Experts still don’t have a complete picture of the different ways that brain development can affect the processing of trauma. “As a field, we’re still figuring it out,” said Laura Wilson, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Mary Washington and editor of The Wiley Handbook of the Psychology of Mass Shootings.

Still, the field of psychology has come a long way in understanding how children and teenagers might experience post-traumatic stress. “Young people are in a lot of ways more resilient,” Wilson said, but they also have less life experience to help them make sense of violence, making them more susceptible to destabilizing shifts in their worldview. It might be harder for young people to feel safe again after experiencing a mass shooting.

Mass shooting trauma can be different from the kind of trauma experienced after natural disasters, because the traumatic event was caused by another person. “You have more individuals that may develop something like PTSD, depression, or anxiety following a man-made disaster,” said Robin Gurwitch, a psychologist and professor at Duke University Medical Center and a member of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Age also affects how the symptoms of post-traumatic stress might manifest. Younger children might experience sleep disturbances, difficulty focusing, and other troubles at school, while adolescent and young adults may also withdraw from their regular activities and relationships, and engage in more risk-seeking behaviors. Untreated symptoms, Gurwitch said, can lead to a greater risk of addiction and the development of other mental and physical health issues later in life.

Martin was a senior at the time of the Columbine shooting; she and her classmates finished their last few weeks at a nearby school. She eventually went off to college, and didn’t tell people there that she was a survivor of what was then the deadliest school shooting in American history. Still, she couldn’t escape it. Once, during class, a fire alarm went off, and she started crying. Another time, a teacher asked her to write a persuasive essay on gun violence, and when she tried to explain why that might be difficult, the teacher told her she needed to write it or fail the class. She failed, and later dropped out.

“I stopped going to classes, and I started using recreational drugs,” Martin said. “I knew I wasn’t okay on a surface level, but I refused to believe it was because of Columbine.” She went to a few sessions of therapy, and tried to move on with her life. Yet the trauma kept resurfacing. She was triggered by the 9/11 terror attacks and, years later, by the mass shooting at Virginia Tech that killed 32 people. “I was horrified, I cried, I freaked out,” she said. “I felt jealous that nobody would remember Columbine.”

Later, Martin went back to college, graduated, and became a teacher. As an adult, she co-founded a group to help support other survivors of mass shootings. Looking back at it now, she thinks, “I was so desperate for people to know my story and know I wasn’t shot, but I’m struggling. It’s a horrible thing to admit and even recognize in yourself.”

Zach Cartaya, a classmate of Martin’s who hid with her that day, experienced a similar trajectory. “I suppressed it through my college years with drugs and alcohol,” he said. After graduating from college, he started a career in financial services, and he, too, found the aftershocks of the shooting creeping up in unexpected ways. His job required regular meetings in conference rooms. At first, they were fine. Yet over time, he said, “those meetings got harder and harder for me. I hated being in them. My skin started to crawl.”

One day, during a meeting, Cartaya realized he couldn’t breathe. “I got up, jumped the table, ran out the door, got in my bed, and didn’t talk to anyone for three days,” he said. He met with his doctor, who ran a battery of tests to make sure there wasn’t some underlying medical cause. When there wasn’t, the doctor sent him to therapy. Cartaya tried different treatments, including eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR), a form of therapy that has been proven effective for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. “I’ve come a long way, and managed to keep a lid on it,” he said, but not until after “things got pretty dark and scary.”

The discovery that everything was not okay, that they were still struggling with what happened, came from events large and small. The survivors of the West Paducah shooting felt it when a school 30 miles away in Marshall County, Kentucky, had a shooting in 2018. Those moments of revelation could be more subtle, too. Leam didn’t receive a PTSD diagnosis until four years ago, when a doctor he was seeing for severe back pain suggested he try seeing a therapist.

Another survivor, William Tipper Thomas, who was paralyzed in a school shooting just outside Baltimore, Maryland, in 2004, said a recent small moment — snapping at his sister during a FaceTime call — helped him realize he was still dealing with trauma-related stress. His sister found it so unusual that she drove from her home in Virginia to his place in Baltimore to confront him about it, leading to him seeking treatment. Thomas had never seen a therapist. When the shooting happened, he was an honors student weeks away from graduating and fulfilling his dream of playing college football. Suddenly, he had to orient himself to using a wheelchair. The argument with his sister, he realized, came just after doing a photo shoot on the field of his college alma mater, where he was supposed to have played.

The timing ended up being significant. In May 2021, Thomas realized he’d crossed an important threshold. He was 17 when he was shot, and he’s 35 now. “I’ve spent more time in the wheelchair than I have walking,” he said. He feels that he’s had a certain level of healing, psychologically and emotionally. Being in a wheelchair, though, makes it hard to forget. “I think about it often because I’m constantly reminded of it,” he said. “It’s hard to heal from things that you’re consistently and constantly reminded of.”

Long after Jenkins Smith was released from the hospital, and after her informal therapy group disbanded, reporters continued to reach out to her, eager to track her story of recovery. At times the interest could be overwhelming, but she also found some value in it: Here were adults who were genuinely interested in her experiences and thoughts, providing an open forum for her to discuss what happened. “I started using reporters as counselors,” she said. “It was therapeutic to me, and I really didn’t have that realization that that’s what I was doing with it until later on in life.”

Though I couldn’t exactly relate to her experience, I instinctively understood it. I’ve never found it necessary to seek treatment for what happened on the day of my school’s shooting, but it looms large in my memories. It was my first and most powerful experience with collective trauma. What has helped me process my feelings as an adult has been writing about it, again and again and again. But perhaps nothing was as helpful as talking with these adult survivors.

There was so much overlap in our experiences. To know that others felt like they weren’t impacted directly enough to need help — even some students who had been shot — was both surprising and reassuring. We were all looking back at the ways we tried, as kids, to comprehend the incomprehensible. We were all considering what life was like back then, what’s different now, and what’s stayed the same.

The survivors I spoke with come from a diverse range of backgrounds and experiences. They grew up in suburbs, rural areas, and cities. Their experiences with guns were mixed. Some, like me, grew up in homes and communities where lots of people owned guns, regardless of their politics. Others had never touched one before. Many, but not all, grew up to favor stricter gun control; a handful of them owned guns themselves. (Leam owns an assault rifle, the kind of weapon he was shot with, but he said he wouldn’t mind if the government banned them.) Dare decided that she doesn’t want guns in her house; Jenkins Smith, despite her initial discomfort, has allowed them because hunting is a part of the culture where she lives, and she wants her children to experience it.

They also had different feelings about how we should discuss the perpetrators of the shootings. Martin asked me not to name the shooters in my article; the media coverage of Columbine focused intensely on the psychology of the shooters, which inspired copycats. Fannie Black, who survived a shooting in 1997 when she was a teen at Bethel High School in Alaska, felt differently. It’s always bothered her that no one ever talked about her school’s shooter when discussing what happened. “No one ever talked about bullying,” she said. She knew the shooter, watched him get bullied, watched him unsuccessfully try to seek help. “This could have been prevented,” she said.

As a teen, Jenkins Smith forgave the boy who shot her. He then proceeded to mail and call her from prison, until her dad called the authorities and told them to make it stop. As an adult, she went to meet with him in prison. She wanted to see what he remembered, and if he was remorseful, though she was almost nine months pregnant at the time and wasn’t sure it was a great idea. He couldn’t remember much, she said, but he did apologize for what he’d done. “I felt like I got what I needed,” she said. “There was no reason for me to talk with him again.”

Many adult survivors have entered the life phase where they are having children. Some have decided not to. “Around the time that it would have made sense for me to have kids,” Cartaya said, “I was realizing I didn’t want to bring children into a world where this stuff was still happening.” Others, though, are now raising kids, some with fellow survivors, in the towns where they grew up. Dare and her husband both attended Santana High School, but they weren’t a couple at the time of the shooting. They didn’t talk much about what happened until it was time for their son to enter high school, and Dare’s husband told her he didn’t want his son to attend their high school, because it would mean too many trips back to a place that was still difficult to visit. “I had no idea it bothered him,” she said. “We had never talked about our experiences of that day.”

Nichole Burcal and her husband are high school sweethearts; they were both in the cafeteria of Thurston High School when their classmate opened fire. Even though they were together, they too had different experiences: Burcal was shot; her husband wasn’t. As one of the injured, she says she received offers of free counseling and scholarships. But he didn’t, she said, “even though we were [both] in the middle of it.” Later, their oldest son attended Thurston High. When it came time to sign him up for cross-country in the school’s cafeteria, she found that she couldn’t do it. “I still can’t go in the cafeteria,” she said, “even 20 years later.”

The impacts of trauma can last a lifetime, but psychologists are much better equipped to deal with young trauma survivors today than they were 20 years ago. “The field of child trauma has grown exponentially over the years, and that’s a good thing because we know more treatments are readily available now for children,” Gurwitch said. Cognitive processing therapy, in which a patient learns to reframe unhelpful thoughts about a traumatic event, and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy have been shown to help children and adolescents recover from traumatic experiences. Parent-child interaction therapy has also proven helpful for young children.

Something else has changed, too: The adult survivors with school-age children have had to process the reality of their children going through active shooter drills. (Research suggests that the drills increase stress and anxiety in students, with little evidence that they’re effective.)

Holm remembered the day his daughter came home from kindergarten and told him and his wife about a drill where they had to turn off the lights and be quiet so the bad guys couldn’t find them. It was the kind of moment, he said, in which “you step outside of yourself and you take a look at your entire life leading up to that moment. It reprioritizes everything. ... This thing that happened to me is now affecting my daughter.”

The following year, when students in Marshall County had a shooting at their school, Holm and other West Paducah survivors met with the students affected, to offer them help. He also wrote an op-ed for his local paper, and started speaking out at rallies for greater gun control. “I was silent for 20 years, and it never went away,” he said, “and these kids kept getting injured and it’s frustrating.” Doing nothing was no longer an option.

Holm wasn’t the only one who took action. After the Aurora, Colorado, shooting in 2012, Martin and another classmate decided to start a group, the Rebels Project, named after the Columbine school mascot, to lend support to and connect with other mass shooting survivors. “When we started, all we knew is that we wanted to help in ways we didn’t have access to in 1999,” Martin said. Since then, the group has met with victims to offer their help and hosts an annual meetup for survivors.

Keene focuses on helping another way. He is a social worker who does therapy with kids, including in his old school district. “Hollan is so outspoken and eloquent, he speaks at rallies, and he’s so good at that,” Keene said of his old high school friend. “The way I deal with it is I pour it into these individuals who are sitting across from me at work.”

There’s been one undeniable difference in the media landscape since the first generation of survivors grew up — young people are more able to make their voices heard about the issue. When Parkland, Florida, students seized on media attention after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School to call for greater gun control, “I was extremely proud of them,” said Thomas, who now works as an engineer and started his own foundation aimed at violence prevention for young people in Baltimore.

A few years ago, Leam took his oldest son with him to an event commemorating the 29th anniversary of the Cleveland Elementary shooting. Getting diagnosed and treated for PTSD has helped Leam cope with the loud noises that used to trigger him, and with the pain of seeing his trauma repeated in countless other schools. Before treatment, “I could be driving and break down in tears, just thinking about what these kids are going through over and over again,” he said.

Still, he hasn’t talked to many of his fellow Cleveland survivors about what happened — even at the anniversary event. “I wish we did more back then to talk about it, and the repercussions from it,” Leam said. “Because I think it could have changed my life.”

'Crisis Text Line is one of the world's most prominent mental health support lines.' (photo: Getty Images)

'Crisis Text Line is one of the world's most prominent mental health support lines.' (photo: Getty Images)

The Crisis Text Line’s AI-driven chat service has gathered troves of data from its conversations with people suffering life’s toughest situations.

But the data the charity collects from its online text conversations with people in their darkest moments does not end there: The organization’s for-profit spinoff uses a sliced and repackaged version of that information to create and market customer service software.

Crisis Text Line says any data it shares with that company, Loris.ai, has been wholly “anonymized,” stripped of any details that could be used to identify people who contacted the helpline in distress. Both entities say their goal is to improve the world — in Loris’ case, by making “customer support more human, empathetic, and scalable.”

In turn, Loris has pledged to share some of its revenue with Crisis Text Line. The nonprofit also holds an ownership stake in the company, and the two entities shared the same CEO for at least a year and a half. The two call their relationship a model for how commercial enterprises can help charitable endeavors thrive.

For Crisis Text Line, an organization with financial backing from some of Silicon Valley’s biggest players, its control of what it has called “the largest mental health data set in the world” highlights new dimensions of the tech privacy debates roiling Washington: Giant companies like Facebook and Google have built great fortunes based on masses of deeply personal data. But information of equal or greater sensitivity is also in the hands of nonprofit groups that fall outside federal regulations on commercial businesses — with little outside control over where that data ends up.

Ethics and privacy experts contacted by POLITICO saw several potential problems with the arrangement.

Some noted that studies of other types of anonymized datasets have shown that it can sometimes be easy to trace the records back to specific individuals, citing past examples involving health records, genetics data and even passengers in New York City taxis.

Others questioned whether the people who text their pleas for help are actually consenting to having their data shared, despite the approximately 50-paragraph disclosure the helpline offers a link to when individuals first reach out.

The nonprofit “may have legal consent, but do they have actual meaningful, emotional, fully understood consent?” asked Jennifer King, the privacy and data policy fellow at the Stanford University Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

Those disclosure terms also note that Meta’s Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp services can access the content of conversations taking place through those platforms. (Before this article was published, Meta confirmed that it has access to that data but says it does not use any of it, except for cases involving risk of imminent harm. After publication, WhatsApp clarified that it and Meta have no access to the contents of messages occurring via WhatsApp.)

Former federal regulator Jessica Rich said she thought it would be “problematic” for third-party companies to have access even to anonymized data, though she cautioned that she was unfamiliar with the companies involved.

“It would be contrary to what the expectations are when distressed consumers are reaching out to this nonprofit,” said Rich, a former director of the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Consumer Protection. She later added: “The fact that the data is transferred to a for-profit company makes this much more troubling and could give the FTC an angle for asserting jurisdiction.”

The nonprofit’s vice president and general counsel, Shawn Rodriguez, said in an email to POLITICO that “Crisis Text Line obtains informed consent from each of its texters” and that “the organization’s data sharing practices are clearly stated in the Terms of Service & Privacy Policy to which all texters consent in order to be paired with a volunteer crisis counselor.”

In an earlier exchange, he emphasized that Crisis Text Line’s relationship with its for-profit subsidiary is “ethically sound.”

“We view the relationship with Loris.ai as a valuable way to put more empathy into the world, while rigorously upholding our commitment to protecting the safety and anonymity of our texters,” Rodriguez wrote. He added that "sensitive data from conversations is not commercialized, full stop.”

Loris’ CEO since 2019, Etie Hertz, wrote in an email to POLITICO that Loris has maintained “a necessary and important church and state boundary” between its business interests and Crisis Text Line.

After POLITICO began asking questions about its relationship with Loris, the nonprofit changed wording on its website to emphasize that “Loris does not have open-ended access to our data; it has limited contractual rights to periodically ask us for certain anonymized data.” Rodriguez said such sharing may happen every few months.

A ‘tech startup’ for mental health crises

Since its launch in 2013, Crisis Text Line says it has exchanged 219 million messages in more than 6.7 million conversations over text, Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp — channels that it says allow it to meet its often youthful client base “where they are.” It has spread beyond the U.S. to open operations in Canada, the U.K. and Ireland.

The New York-based nonprofit says it knows how “deeply personal and urgent” these silent conversations are for those reaching out, many of them young, people of color, LGBTQ or living in rural areas: “68% of our texters share something with us that they have never shared with anyone else,” the helpline wrote in one government filing.

In a little less than 1 percent of cases, the group says, the conversation becomes so dire that it contacts emergency services to “initiate an active rescue.” Two to three times a week, it wrote in one 2020 report, the discussion turns to thoughts of homicide, “most often a school shooting or partner murder.”

Data science and AI are at the heart of the organization — ensuring, it says, that those in the highest-stakes situations wait no more than 30 seconds before they start messaging with one of its thousands of volunteer counselors. It says it combs the data it collects for insights that can help identify the neediest cases or zero in on people’s troubles, in much the same way that Amazon, Facebook and Google mine trends from likes and searches.

“We know that if you text the words ‘numbs’ and ‘sleeve,’ there's a 99 percent match for cutting,” the nonprofit’s co-founder and former CEO, Nancy Lublin, said in a 2015 TED talk. “We know that if you text in the words ‘mg’ and ‘rubber band,’ there's a 99 percent match for substance abuse. And we know that if you text in ‘sex,’ ‘oral’ and ‘Mormon,’ you're questioning if you're gay.”

“I love data,” added Lublin, who has also described the helpline as “a tech startup.” She had previously founded the group Dress for Success, which provides business clothing and job training to women in need. (This month, Lublin referred questions about the relationship between the help line and Loris to Hertz, the current Loris CEO.)

Crisis Text Line has partnered with local governments and more than a dozen school systems across the country and has expanded its reach by teaming up with tech titans like Google, Meta and TikTok. The organization also allows access to its data for research purposes.

But it also came to view texters’ data as valuable for another purpose: helping corporations deal with their customer service problems.

So in 2018, Lublin created Loris, with backing from investors including former LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner and the Omidyar Network of billionaire eBay founder Pierre Omidyar. Its purpose, the company outlined, was to use Crisis Text Line’s “de-escalation techniques, emotional intelligence strategies, and training experience” to develop AI software that helps guide customer service agents through live chats with customers.

“We’ve baked all of our learning into enterprise software that helps companies boost empathy AND bottom line,” says Loris’ website, which features testimonials from clients such as the ride-hailing company Lyft and the meal-subscription service Freshly.

The “core” of its artificial intelligence, Loris said in a news release last year, comes from the insights “drawn from analyzing nearly 200 million messages” at Crisis Text Line. (Hertz, the Loris CEO, said in an email that its AI has evolved and now includes data from e-commerce and other industries.)

Loris’ website says a portion of the company’s revenue would go toward supporting the nonprofit, calling the arrangement “a blueprint for ways for-profit companies can infuse social good into their culture and operations, and for nonprofits to prosper.” In practice, Crisis Text Line’s Rodriguez said, the company “has not yet reached the contractual threshold” where such revenue-sharing would occur, although he said Loris paid Crisis Text Line $21,000 in 2020 for office space.

“Simply put, why sell t-shirts when you can sell the thing your organization does best?” reads Crisis Text Line’s description of the data-sharing partnership.

Volunteers speak out

Former Crisis Text Line volunteer Tim Reierson has a different term for Loris’ use of the crisis line’s data: “disrespectful.”

“When you're in conversation with someone, and you don't know how it's going to end … it's a very delicate and tender and fragile space,” said Reierson, who has started a public campaign to try to change the nonprofit’s data practices. He said the people who contact the text line — many of them teens or younger — include “somebody staring at blades on their table in front of them, or somebody hiding from a parent who's on a rampage, or someone who's struggling with an eating disorder, somebody who's ready to end their life.”

In his experience as a volunteer, he said he believed those individuals “definitely have an expectation that the conversation is between just the two people that are talking.”

Reierson said the organization terminated him in August after he began raising concerns internally about its handling of data. Rodriguez, the Crisis Text Line general counsel, disputed this, saying Reierson “was dismissed from the volunteer community because he violated Code of Conduct.” Despite repeated requests, Rodriguez declined to specify what the alleged violations were.

“I absolutely did not ever violate the code of conduct, not even close, and they know that,” Reierson said. “There is a process that is followed for code of conduct violations and it was never invoked. … The organization encourages volunteers and staff to use their internal system for expressing any concerns, and that’s what I did.”

Former volunteer Alison Diver — who described talking one texter out of jumping off a freeway bridge and another off a hotel balcony — left Crisis Text Line in July. She said she has since signed onto a Change.org petition that Reierson started that urges the nonprofit “to phase out its practice of monetizing crisis conversations as data, as soon as possible.” Diver expressed alarm after hearing Reierson describe the nonprofit’s data practices.

“That makes me feel betrayed,” she said, contending that volunteers should have a say in whether the data is used for other purposes. “They wouldn't even have a Crisis Text Line if it wasn't for us.”

Beck Bamberger, a current volunteer in California who has logged nearly 300 hours during her three years with the hotline, said she was not aware that data from those conversations was being used for customer service applications until POLITICO reached out for this story.

"Mental health and people cutting themselves adapted to customer service?” she said. “That sounds ridiculous. Wow.”

She added: "If your volunteers, staff and the users themselves are not aware of that use, then that's a problem.”

Reierson launched a website in January calling for “reform of data ethics” at Crisis Text Line, and his petition, started last fall, also asks the group to “create a safe space” for workers to discuss ethical issues around data and consent.