30 October 21

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

WHO WILL STEP UP FOR RSN? Who will be the ones that say, "I will support this project." These are the Reader Supporters, the stalwarts, the engine that drives this publication. It's not easy, but these are not easy times. Come on Reader Supporters! In gratitude.

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News

Sure, I'll make a donation!

Cuban Exile Told Sons He Trained Oswald, JFK's Accused Assassin, at a Secret CIA Camp

Nora Gamez Torres, Miami Herald

Gamez Torres writes: "Almost 40 years after his death following a bar brawl in Key Biscayne, Ricardo Morales, known as 'Monkey' - contract CIA worker, anti-Castro militant, counter-intelligence chief for Venezuela, FBI informant and drug dealer - returned to the spotlight Thursday morning when one of his sons made a startling claim on Spanish-language radio."

Almost 40 years after his death following a bar brawl in Key Biscayne, Ricardo Morales, known as “Monkey” — contract CIA worker, anti-Castro militant, counter-intelligence chief for Venezuela, FBI informant and drug dealer — returned to the spotlight Thursday morning when one of his sons made a startling claim on Spanish-language radio:

Morales, a sniper instructor in the early 1960s in secret camps where Cuban exiles and others trained to invade Cuba, realized in the hours after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963 that the accused killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, had been one of his sniper trainees.

Morales also told his two sons that two days before the assassination, his CIA handler told him and his “clean-up” team to go to Dallas for a mission. But after the tragic events, they were ordered to go back to Miami without learning what the mission was about.

The claims made by Ricardo Morales Jr. during a show on Miami’s Actualidad Radio 1040 AM, add to one of the long-held theories about the JFK assassination — that Cuban exiles working for the CIA had been involved. But the claims also point the finger at the CIA, which some observers believe could help explain why President Joe Biden backed off last week on declassifying the remaining documents in the case.

Morales’ son, 58, said the last time his father took him and his brother to shooting practice in the Everglades, a year before dying in 1982, he told them he felt his end was near because he had revealed too much information of his work for the CIA to a Venezuelan journalist and he was writing a memoir. So he encouraged his sons to ask him questions about his life.

“My brother asked ‘Who killed John F. Kennedy?’ and his answer was, ‘I didn’t do it but I was in Dallas two days before waiting for orders. We were the cleaning crew just in case something bad had to be done.’ After the assassination, they did not have to do anything and returned to Miami,” his son said on the radio show.

Morales Jr. said his father told them he did not know of the plans to assassinate Kennedy.

“He knew Kennedy was coming to Dallas, so he imagines something is going to happen, but he doesn’t know the plan,” he said. “In these kinds of conspiracies and these big things, nobody knows what the other is doing.”

Morales also knew Oswald, his son claims.

“When my old man was training in a CIA camp — he did not tell me where — he was helping to train snipers: other Cubans, Latin Americans, and there were a few Americans,” he said. “When he saw the photo of Lee Harvey Oswald [after the assassination] he realized that this was the same character he had seen on the CIA training field. He saw him, he saw the name tag, but he did not know him because he was not famous yet, but later when my father sees him he realizes that he is the same person.”

Morales Jr. gave a similar account to the Miami Herald in an interview Thursday, adding that his father said he didn’t believe Oswald killed Kennedy “because he has witnessed him shooting at a training camp and he said there is no way that guy could shoot that well.”

He said he believes his father told the truth at a moment he was fearing for his life after losing government protection.

While Lee Harvey Oswald was accused in Kennedy’s assassination, a 1979 report from the House Select Committee on Assassinations contradicted the 1964 Warren Commission conclusion that JFK was killed by one lone gunman. The committee instead concluded that the president was likely slain as the result of a conspiracy and that there was a high probability that two gunmen fired at him.

The House Select Committee, which also interviewed Morales, said they couldn’t preclude the possibility that Cuban exiles were involved.

There have been previous reports that a group of anti-Castro Cuban exiles, including the leader of the organization Alpha 66, Manuel Rodriguez Orcarberro, met at a house in Dallas days before the assassination, and that Oswald was seen visiting the house or being in the area. As that theory goes, Cuban exiles, who felt betrayed by Kennedy’s lack of support in the 1961 Bay of Pigs operation and his deal with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev after the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis not to invade Cuba, could have planned to kill JFK and blamed Castro so the U.S. would invade the island.

Other theories say the CIA was involved in the conspiracy, using Cuban exiles while helping create a fake narrative to paint Oswald as a pro-Castro communist so that the Cuban leader could be blamed for the assassination.

The CIA did not immediately reply to an email requesting comments about the new allegations.

Whatever happened, Biden’s decision to postpone the declassification of the remaining 15,000 documents linked to the case is once again giving life to the conspiracy theories. Morales’ son believes the documents might never be made public.

After advocating for the documents’ release, President Biden ordered the postponement last week citing the impact of the COVID pandemic on the declassifying efforts and the need to protect “against identifiable harm to the military defense, intelligence operations, law enforcement, or the conduct of foreign relations that is of such gravity that it outweighs the public interest in immediate disclosure.”

“If Lee Harvey Oswald was the killer, acting on his own, why not release the documents?” said Democratic pollster Fernand Amandi, who has extensively researched Kennedy’s assassination.

Other experts think that no single document will reveal the truth, but might shed light on how intelligence agencies impeded the investigations to cover other operations, tactics and shadow figures.

Peter Kornbluh, a Cuba analyst at the National Security Archive in Washington, D.C., called on the Biden administration to release the remaining JFK assassination records and end “the speculation, conjecture and conspiracy theories that have flourished because of the secrecy surrounding these documents.”

“If we have learned anything from the Kennedy assassination,” he noted, “it is that conspiracy theories like this one spread like mold in the darkness of secrecy. Almost 60 years later, it is time for historical transparency so that the Kennedy assassination can be laid to rest.”

Amandi, who called Morales Jr.’s account “a bomb” said there is no doubt that what Morales told his sons has merit, since he was a confessed CIA hitman, he told the Herald. Amandi believes many documents in the classified records make reference to Morales.

But Morales’ complex history and character, and his legal maneuvers to stay out of prison by becoming an informant in several federal and state investigations of anti-Castro terrorist activities, along with his drug trafficking, gave him a reputation as a clever man who was also unreliable.

The “Monkey,” a former intelligence agent for the Castro government in the early days of the revolution, later worked for or collaborated with the CIA, the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, Israel’s Mossad and Venezuela’s DISIP intelligence agency during the 1960s and ‘70s. According to CIA documents declassified in 2017, Morales was terminated as a CIA contract worker in 1964 after a mission in the Congo because he was “’too wise’ and not too clever for own good.”

His son said his father was in Cuba during the Cuban missile crisis and was working as a double agent, feeding false information to Cuban intelligence services after he was already a CIA asset.

Morales claimed to have been involved in almost every major plot to overthrow Fidel Castro, and he confessed to having a hand in more than 15 bombings. After his death, he was even linked to a plot to kill Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in 1976, the Herald reported in 1991.

In a pretrial deposition related to a drug investigation case in which he was an informant, Morales confessed to being one of the people behind the mid-air bombing of a Cubana Airlines jetliner in Barbados in 1976, killing all 73 aboard. He also implicated the late Luis Posada Carriles, believed to be the mastermind of the bombing. In a 2005 interview with the Herald, Posada Carriles dismissed Morales’ account, attacking his character.

“I never would have participated in any conspiracy with Monkey Morales,” Posada said. “I’d have to be crazy, my God! Everything Monkey said had a double intent. He was not credible.”

But the fact that Morales avoided prosecution time after time, and that his name seems to pop up in so many government records, make his son and Amandi believe he knew what he was talking about regarding Kennedy’s assassination, they said during the show.

Morales’ son also made another claim on the show that might solve another 1980s murder mystery.

“On his deathbed, my uncle confessed he killed Rogelio Novo in retaliation for my father’s murder,” he said. Novo was the owner of Rogers on the Green, the Key Biscayne restaurant and bar where Morales was gunned down in December 1982. No one was ever arrested in Novo’s death.

A series of killings, including the death of Morales’ lawyer months before Morales himself was killed “destroyed my family,” his son told the Herald. The family split and scattered all around the country, fearing retaliation.

Morales Jr. currently lives in Michigan. He didn’t say anything before about the Kennedy connection because in the beginning, the family was “scared to death,” he said. Later he thought people would not believe him.

He mentioned the family is now considering a TV deal in connection to his father’s life, but gave no further details.

“It’s an amazing story,” he said. “It seems larger than life.”

READ MORE

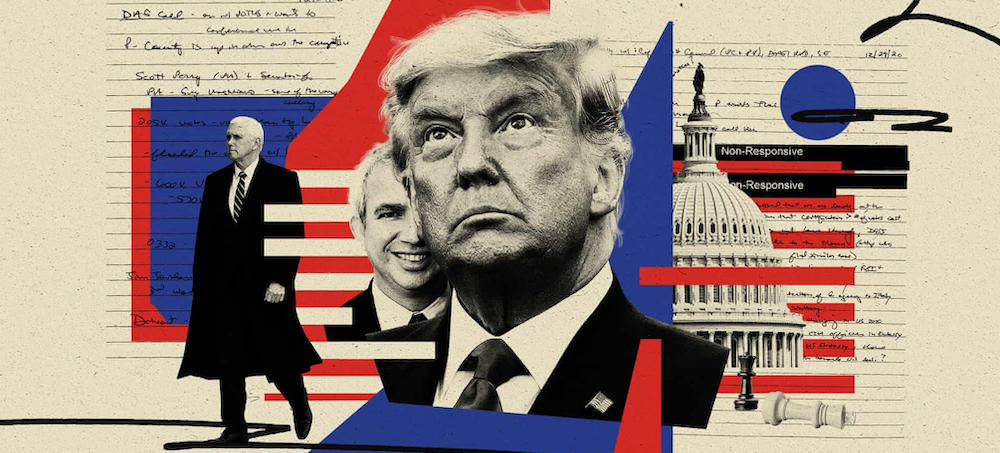

Investigations by the U.S. House and Senate have added granular detail that has astonished even seasoned election-watchers in terms of the scale and complexity of Trump's attempted coup. (image: Klawe Rzeczy/Getty Images)

Investigations by the U.S. House and Senate have added granular detail that has astonished even seasoned election-watchers in terms of the scale and complexity of Trump's attempted coup. (image: Klawe Rzeczy/Getty Images)

'A Roadmap for a Coup': Inside Trump's Plot to Steal the Presidency

Ed Pilkington, Guardian UK

Pilkington writes: "On 4 January, the conservative lawyer John Eastman was summoned to the Oval Office to meet Donald Trump and Vice-President Mike Pence. Within 48 hours, Joe Biden's victory in the 2020 presidential election would formally be certified by Congress, sealing Trump's fate and removing him from the White House."

A startling memo, a surreal Oval Office encounter – just some of the twists in the unfolding story of Trump’s bid to cling to power, which critics say was no less than an attempted coup

On 4 January, the conservative lawyer John Eastman was summoned to the Oval Office to meet Donald Trump and Vice-President Mike Pence. Within 48 hours, Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election would formally be certified by Congress, sealing Trump’s fate and removing him from the White House.

The atmosphere in the room was tense. The then US president was “fired up” to make what amounted to a last-ditch effort to overturn the election results and snatch a second term in office in the most powerful job on Earth.

Eastman, who had a decades-long reputation as a prominent conservative law professor, had already prepared a two-page memo in which he had outlined an incendiary scenario under which Pence, presiding over the joint session of Congress that was to be convened on 6 January, effectively overrides the votes of millions of Americans in seven states that Biden had won, then “gavels President Trump as re-elected”.

The Eastman memo, first revealed by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa in their book Peril, goes on to predict “howls” of protest from Democrats. The theory was that Pence, acting as the “ultimate arbiter” of the process, would then send the matter to the House of Representatives which, following an arcane rule that says that where no candidate has reached the necessary majority each state will have one vote, also decides to turn the world upside down and hand the election to the losing candidate, Donald Trump.

Eastman’s by now notorious memo, and the surreal encounter in the Oval Office, are among the central twists in the unfolding story of Trump’s audacious bid to hang on to power. They form the basis of what critics argue was nothing less than an attempted electoral coup.

In an interview with the Guardian, Eastman explained that he had been asked to prepare the memo by one of Trump’s “legal shop”. “They said can you focus first on the theory of what happens if there are not enough electoral votes certified. So I focused on that. But I said: ‘This is not my recommendation. I will have a fuller memo to you in a week outlining all of the various scenarios.’”

Inside the Oval Office, with the countdown on to 6 January, Trump urged Pence to listen closely to Eastman. “This guy’s a really respected constitutional lawyer,” the president said, according to the book I Alone Can Fix It.

Eastman, a member of the influential rightwing Federalist Society, told the Guardian that he made clear to both men that the account he had laid out in the short memo was not his preferred option. “The advice I gave the vice-president very explicitly was that I did not think he had the authority simply to declare which electors to count” or to “simply declare Trump re-elected”.

Eastman continued: “The vice-president turned to me directly and said, ‘Do you think I have such powers?’ I said, ‘I think it’s the weaker argument.’”

Instead, Eastman pointed to one of the scenarios in the longer six-page memo that he had prepared – “war-gaming” alternatives. His favorite was that the vice-president could adjourn the joint session of Congress on 6 January and send the electoral college votes back to states that Trump claimed he had lost unfairly so their legislatures could have another go at rooting out the fraud and illegality the president had been railing about since election day.

“My advice to the vice-president was to allow the states formally to assess the impact of what they had determined were clear illegalities in the conduct of the election,” Eastman said. After a delay of a week or 10 days, if they found sufficient fraud to affect the result, they could then send Trump electors back to Congress in place of the previous Biden ones.

The election would then be overturned.

“Those votes are counted and TRUMP WINS,” Eastman wrote in his longer memo, adding brashly: “BOLD, certainly … but we’re no longer playing by Queensbury rules.”

Eastman insisted to the Guardian that he had only been presenting scenarios to the vice-president, not advice. He said that since news of his memos broke he had become the victim of a “false narrative put out there to make it look as though Pence had been asked to do something egregiously unconstitutional, so he was made to look like a white knight coming in to stop this authoritarian Trump”.

The problem is that for many close observers of American elections, Eastman’s presentation to Pence just two days before the vice-president was set to certify Biden’s victory leaves a very different impression.

Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, a leading authority on US election issues, sees Eastman’s set of alternative scenarios as nothing less than a “fairly detailed roadmap for a constitutional coup d’état. That memo was a plan for a series of tricks to steal the presidency for Trump.”

The 2020 presidential election was the largest in US history, with a record 156 million votes cast and the highest turnout of eligible voters since 1900. By all official accounts, it was also among the most secure and well-conducted in US history.

“It was something of a civil miracle,” Waldman said. “To have this massive turnout, an election that was extraordinarily well run, in the middle of a pandemic – this was one of America’s finest hours in terms of our democracy.”

And yet, Waldman went on, what happened next? “Trump’s big lie, his campaign to overturn the election, the insurrection.”

Alarm bells began to ring months before America went to the polls on 3 November 2020. As early as July Trump was laying into mail-in voting, which was seeing huge voter take-up as a result of Covid-19, deriding the upcoming poll as the “most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT Election in history” and calling for it to be delayed.

At the time, Biden was holding a steady opinion poll lead over Trump in battleground states.

By September, Trump was refusing to commit to a peaceful transfer of power. He told reporters: “We’re going to have to see what happens.”

When we did see what happened – Biden winning the presidency by a relatively convincing margin – Trump refused to concede. Now, something that had only been posited as a remote and extreme possibility was unfolding before Americans’ eyes.

“The events of 2020 were unprecedented,” said Ned Foley, a law professor at the Ohio State University. “A sitting president was trying to get a second term that the voters didn’t want him to have – it was an effort to overturn a free election and deprive the American people of their verdict.”

Since the violent incidents of 6 January when a mob of Trump supporters stormed the US Capitol, resulting in the deaths of five people, information has begun to amass about Trump’s extensive ploy to undo American democracy. Congressional investigations by the US House and Senate have added granular detail that has astonished even seasoned election-watchers in terms of the scale and complexity of the endeavour.

For Foley, a picture has come into focus of a “systematic effort to deny the voters their democratic choice. It was a deliberate, orchestrated campaign, and there’s nothing more fundamentally undemocratic than what was attempted.”

Rick Hasen, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine who has written a report on 2020 election subversion, said that as time has passed the scope of Trump’s ambition has become clear. “There was much more behind the scenes than we knew about. We came much closer to a political and constitutional crisis than we realized,” he said.

In his Guardian interview, Eastman justified his Oval Office presentation to Pence on scenarios of how to overturn an election by pointing to widespread irregularities in the 2020 voting process. He claimed there were “violations of election law by state or county election officials” and “good, unrebutted evidence of fraud”.

Asked how he would answer the charge that has been levelled at him that he had sketched out an electoral coup, he replied: “That begs the question: was there illegality and fraud? If there was, and it altered the results of the election, then that undermines democracy, as we have someone put in office who has not been elected.”

But why would such widespread fraudulent activity be directed against Trump and not, say, Biden, or before him Barack Obama? Eastman said that it was because Trump was “pushing back against the deep state in American politics”.

The “deep state” had become such an entrenched bureaucracy that it was “unaccountable to the ultimate sovereign authority of the American people”, Eastman said. “Trump’s punching back had all of the forces aligned with that entrenched bureaucracy doing everything to stop him.”

Contrary to Eastman’s claim that widespread fraud occurred during the election, all the main federal and state authorities charged with safeguarding the 2020 election, including law enforcement, have declared it historically secure. In several instances, that conclusion was reached by Trump’s own hand-picked Republican officials.

They included Chris Krebs, who had been appointed by Trump to be director of the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (Cisa) in charge of protecting the integrity of the 2020 election. On 12 November, Cisa put out a joint statement from election security officials that found the presidential vote to be “the most secure in American history”.

Five days later Krebs was out of a job. “He fired me by Twitter,” Krebs told the Guardian. “One of Trump’s own nominees saying the election was legitimate was a credibility issue for him. What he did to me shows there were lengths to which the former president would go which were well beyond any previous norms.”

Bill Barr, then US attorney general, was another Trump appointee who challenged the false claims of mass election fraud. Two days after the election, Barr bowed to pressure from the president and allowed federal prosecutors to investigate allegations of voting irregularities, a break with a longstanding justice department norm that prevented prosecutors from interfering in active election counts.

Yet later in November, Barr met Trump at the White House and told him bluntly, according to Peril, that stories of widespread illegality were “just bullshit”. Then, on 1 December, the attorney general told Associated Press that the FBI and prosecutors had found no fraud on a scale sufficient to impact the election result.

Barr stood down as the nation’s top prosecutor two weeks later.

Another prominent Republican lawyer who thoroughly rejects Trump’s “big lie” that the election was stolen from him is Ben Ginsberg. For almost four decades, Ginsberg was at the center of major election legal battles as counsel to the Republican National Committee as well as to four of the last six Republican presidential nominees, through his law firm, Trump included.

Ginsberg was also a central figure in the white-hot recount in Florida in 2000 that handed the White House to George W Bush.

“What we’ve seen has been different from anything in my experience, because Donald Trump has made an assertion about our elections being fraudulent and the results rigged,” Ginsberg told the Guardian. “I know from my 38 years of conducting election-day operations that that simply is not true, there is no evidence for it. What Donald Trump is saying is destructive to the democracy at its very foundations.”

Ginsberg likened Trump to an arsonist firefighter. “He is setting a fire deliberately so that he can be the hero to put it out. The problem is that there is no real fire, there is no systemic election fraud. The destruction is unnecessary.”

Trump’s campaign to subvert the election began with a flurry of tweets after election day. The New York Times calculated that in the three weeks from 3 November he attacked the legitimacy of the election to his vast social media following more than 400 times.

In the past few weeks, as congressional investigations have deepened, it has become clear that Trump’s efforts to overturn the election result were much more extensive and multi-layered than his Twitter rages. “This wasn’t just some crazy tweets,” Waldman said. “There was a concerted effort to push at every level to find ways to cling to power, even though he had lost.”

Politico estimated that in the month after the election, the sitting president reached out to at least 31 Republicans at all levels of government, from governors to state lawmakers, members of Congress to local election officials. Such was the obsessive attention to detail, the sitting US president even called the Republican chairwoman of the board of canvassers in Wayne county, Michigan, to encourage her not to certify Biden’s victory in a heavily Democratic area.

At the centre of the operation was a ragtag bunch of lawyers assembled by Rudy Giuliani, the former mayor of New York who was acting as Trump’s personal attorney. Few of the team had experience in election law; Barr referred to them, according to Peril, as a “clown car”.

Among the comical conspiracy theories amplified by Giuliani and the Trump campaign lawyer Sidney Powell was “Italygate”, the idea that an Italian defense company used satellites to flip votes from Trump to Biden.

Such florid fantasies, and the accompanying absence of hard and credible data, did little to endear Trump’s legal team to the courts. By the end of December, 61 lawsuits had been lodged by Trump and his acolytes in courts ranging from local jurisdictions right up to the US supreme court. Of those, only one succeeded, on a minor technicality.

Yet the epic failure to persuade judges to play along with Trump’s efforts at subversion should not disguise the seriousness of the endeavour, nor how far it was allowed to proceed. “What I find most disturbing is how far this plot got with such thin material to work with,” Foley said.

One of the most alarming aspects of the fraud conspiracy theories peddled around Trump was that so many senior Republicans and the Republican party itself endorsed them.

On 19 November, Powell was invited to appear in front of cameras at the headquarters of the Republican National Committee. Four days earlier, the Trump campaign had circulated an internal memo that thoroughly debunked a bizarre claim championed by Powell – that Biden’s victory was the product of a communist plot. Yet Powell went ahead nonetheless, using her RNC platform to double down on the palpably false claim that Dominion voting machines created by Venezuela’s deceased president Hugo Chávez (they weren’t) had been manipulated to redirect Trump votes to Biden (they hadn’t).

Complicity in the lie of the stolen election reached right to the heart of the Republican party. Even on 6 January, while shattered glass lay strewn across the corridors of Congress following the violent insurrection hours earlier, 139 House Republicans – more than half the total in the chamber – and eight Senate Republicans went ahead and voted to block the certification of Biden’s win.

Many other Republicans also acted as passive accomplices in Trump’s subversion plot, by failing publicly to speak out against it. Mitch McConnell, the top Republican in the US Senate, waited until 15 December to recognize Biden as president-elect.

For six weeks, McConnell watched and waited. He remained silent, as every day the big lie grew stronger, amplified through the echo chambers of Fox News, the far-right OANN news network and a web of Trump benefactors including the MyPillow founder, Mike Lindell.

Ginsberg told the Guardian that “the greatest disappointment to me personally is seeing people I know to be principled, with only the best intentions for the country, stand aside as Donald Trump wreaks havoc through American democracy. I don’t understand that, and I think it has really negative ramifications.”

Ginsberg added: “Many of them are guilt-ridden about that. It is a very unfortunate, disappointing situation.”

On 7 November, the Associated Press called Pennsylvania, and with it the presidency, for Biden. At that point, Trump’s efforts to subvert the election went into hyper-drive.

“Trump appeared to think he had a viable path to staying in power,” said Hasen. “His outlook morphed into an actual attempt to use the claims of fraud to try and overturn the election.”

Trump turned to what has been dubbed the “independent state legislature doctrine”. This is a convoluted legal theory that has been increasingly embraced by the right wing of the Republican party.

Those who adhere to the doctrine point to the section of the US constitution that gives state legislatures the power to set election rules and to determine the “manner” in which presidential electors are chosen under the electoral college system. If those rules are changed by other legal entities without the approval of the state legislatures, then, the theory goes, election counts can be deemed illegitimate and an alternate slate of electors imposed.

“It’s an extreme legal theory that does not depend on fraud but on claimed irregularities between the way 2020 was conducted and how the states had set up the election,” Hasen said.

Trump and his legal advisers began bearing down on critical swing states which Biden had won, attempting to browbeat state legislators into taking up the doctrine and using it as a means of overturning the result. Lawmakers in Arizona, Pennsylvania and other battleground states were encouraged to call a special session to highlight the disparities in election procedures, with the end goal being to replace Biden’s presidential electors with an alternate slate of Trump electors.

In his Guardian interview, Eastman said he was part of this effort. “I recommended that the legislatures be called into special session to assess the impact of the illegality. If there were cumulative illegal actions greater than the margin of victory, then the legislature needed to take the power back.”

A month before Eastman gave his presentation to Trump and Pence in the Oval Office, he appeared before the Georgia legislature. By that point Georgia had already held a full hand recount of the almost 5m votes cast and was poised to announce the results of a third count – all of which confirmed Biden had won.

In a half-hour presentation on 3 December, Eastman called on Georgia’s lawmakers to effectively take the law into their own hands. “You could adopt a slate of electors yourselves,” he told them. “I don’t think it’s just your authority to do that, but, quite frankly, I think you have a duty to do that to protect the integrity of the election in Georgia.”

And then Trump took the fight to the next level: into the heart of US law enforcement. An interim report from the Senate judiciary committee published earlier this month chronicles the bombardment to which senior Department of Justice officials were subjected in the days leading up to 6 January.

It is a fundamental DoJ norm that the president and his allies should never interfere in any investigation, let alone to undermine American democracy. Yet the Senate report shows that on the day after Barr’s departure was announced, 15 December, Trump began ratcheting up pressure on his replacement to try to get him to adopt the big lie.

When Jeffrey Rosen, the new acting attorney general, demurred, Trump turned to a relatively lowly justice official, Jeffrey Clark, and propelled him into the thick of a mounting power struggle that had the potential to turn into a full-blown constitutional crisis. Clark, who was recently subpoenaed by the House committee investigating the 6 January insurrection, drew up a draft letter which he intended to have sent out to six critical swing states.

In essence, it called on state legislatures won by Biden to throw out the official will of the people and reverse it for Trump.

When Rosen refused to authorize the letter, Trump prepared to fire him and put Clark in his place. It took a showdown in the Oval Office at which key justice department officials threatened to resign en masse, accompanied even by the White House counsel, Pat Cipollone, before Trump stood his threat down.

That volatile three-hour meeting on 3 January was one of the most dramatic incidents in which US democracy was pushed to the brink of collapse. It was not the only one.

As the clock ticked down towards Trump’s final appointment with fate on 6 January, he grew more and more agitated. On 27 December, he called Rosen to make another attempt at cajoling the justice department to come on board with his subversion plot.

Handwritten notes taken by Rosen’s deputy record an astonishing exchange:

Rosen: “Understand that the DoJ can’t + won’t snap its fingers + change the outcome of the election, doesn’t work that way.”

Trump: “Don’t expect you to do that, just say that the election was corrupt + leave the rest to me and the R[epublican] congressmen.”

Then, on 2 January, Trump made his by now notorious call to Brad Raffensperger, Georgia’s top election official as secretary of state. A recording of the conversation obtained by the Washington Post captured Trump telling Raffensperger, “I just want to find 11,780 votes” – one more vote than Biden’s margin of victory in the official count.

Raffensperger politely rejected the request. Four days later, Pence turned his back on Eastman’s scenarios, and announced that he would do his constitutional duty and certify Biden as the 46th president of the United States.

Trump had run out of road. He had nothing left, nowhere else to turn. Nothing, that is, except for his adoring, credulous and increasingly angry supporters.

“Big protest in DC on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!” Trump exhorted his followers in a now excised tweet.

Just how direct was Trump’s involvement in inciting the insurrection is now the stuff of a House select committee inquiry. The committee is aggressively pursuing Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist in the White House, over any role he might have played in the buildup towards the violence.

Bannon, who faces criminal charges for defying congressional subpoenas, was among a gathering at the Willard Hotel in Washington on the eve of 6 January that the House committee has dubbed the “war room”. Also present were Giuliani and Eastman. According to Peril, Trump called into the meeting and spoke with Bannon, expressing his disgust over Pence’s refusal to play along and block the certification just as Eastman had outlined.

When 6 January finally arrived, all eyes were on the Ellipse, the park flanking the White House where Trump was set to headline a massive “Stop the Steal” rally. Before he spoke, Eastman said a few words.

The law professor recounted one of his more lurid conspiracy theories – that voting machines had secret compartments built within them where pristine ballots were held until they were needed to increase Biden’s numbers and put him over the top. “They unload the ballots and match them to the unvoted voter and … voilà!”

Then Trump took the stage. He encouraged his thousands of followers to march to the Capitol. “Fight like hell. If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country any more.”

The Guardian asked Eastman whether he had any regrets about what happened, personal or otherwise. A week after the insurrection he was pressured into stepping down from his post at Chapman University in California.

“Regrets, yes, that people are taking action against me for telling the truth,” he said. “Regrets that I told the truth and that I continue to do so? Absolutely not.”

Eastman’s pledge to continue “telling the truth” will not soothe the anxieties of those concerned about American democracy. Already, speculation about another Trump run in 2024 is causing jitters.

Liz Cheney, a member of the House committee inquiry into the insurrection, has issued a stark warning to her Republican colleagues. Unless they start really telling the truth, she has told them, and countering the lies about election fraud, the country is on the path of “national self-destruction”.

Rick Hasen shares her fears. “Donald Trump has been underestimated before,” he said. “He is telling us he’s planning on running. He’s continuing to claim the election was stolen. The situation in the United States right now is desperate.”

READ MORE

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. (photo: Brittany Greeson/Getty Images)

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. (photo: Brittany Greeson/Getty Images)

AOC Says Now Is the Time to 'Bring the Heat on Biden' to Cancel Student Debt: 'He Doesn't Need Manchin's Permission for That'

Ayelet Sheffey, Business Insider

Sheffey writes: "AOC is disappointed in the $1.75 trillion social-spending plan President Joe Biden unveiled on Thursday, and she says it's a good time to ramp up pressure on the President to cancel student debt."

AOC is disappointed in the $1.75 trillion social-spending plan President Joe Biden unveiled on Thursday, and she says it's a good time to ramp up pressure on the President to cancel student debt.

The plan is significantly scaled down from Democrats' initial $3.5 trillion proposal and leaves out many progressive priorities, thanks to negotiations that were necessary to get centrist Democratic holdouts Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema on board.

The New York representative. posted about the smaller Build Back Better (BBB) framework on her Instagram story on Thursday:

"I think given how much BBB has been slashed there is more opportunity than ever to bring the heat on Biden to cancel student loans. He doesn't need Manchin's permission for that and now that his agenda is thinly sliced he needs to step up his executive action game and show his commitment to deliver for people."

Ocasio-Cortez also suggested the possibility of a "showdown" when student-loan payments are expected to resume on February 1 after a nearly two-year pause, adding that "we need to organize and prepare actions now." She called out the Debt Collective — a debtors' union that is fighting to abolish all forms of debt — for guidance on organizing.

As Insider reported, the only measure that would have significantly helped lessen student debt in Biden's plan — free community college — did not make the cut, and higher education as a whole received just a $40 billion investment to increase Pell grants and support minority-serving colleges, compared to the $400 billion early education and childcare got.

Given that the Education Department is reportedly preparing a "safety net" to ease borrowers back into repayment next year, it doesn't look like broad student-debt cancellation is coming anytime soon. Biden has yet to fulfill his campaign promise of $10,000 in forgiveness per borrower, and he asked the department nearly seven months ago to prepare a memo on his legal ability to cancel at least $50,000.

The results of that memo have yet to be released, and Ocasio-Cortez joined a group of her Democratic colleagues earlier this month in urging the department to tell borrowers across the country if Biden will cancel their student debt.

"Millions of borrowers across the country are desperately asking for student debt relief," Minnesota Rep. Ilhan Omar, who led the effort, told Insider. "We know the President can do it with the stroke of a pen."

Biden has so far canceled about $11.5 billion in student debt for targeted groups of borrowers, like those defrauded by for-profit schools, and Education Secretary Miguel Cardona recently said "conversations are continuing" with broad loan forgiveness.

READ MORE

A Florida-based for-profit prison company paid detainees $1 a day for their work. (photo: On Labor)

A Florida-based for-profit prison company paid detainees $1 a day for their work. (photo: On Labor)

Immigrant Detainees Who Earned Just $1 a Day Are Owed $17 Million in Back Pay, a Jury Says

Martin Kaste, NPR

Kaste writes: "A federal jury in Tacoma, Wash., says the GEO Group, which owns and runs a large detention center for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, owes former detainees $17.3 million in back pay for tasks such as cleaning and cooking meals."

A federal jury in Tacoma, Wash., says the GEO Group, which owns and runs a large detention center for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, owes former detainees $17.3 million in back pay for tasks such as cleaning and cooking meals.

The Florida-based for-profit prison company paid detainees $1 a day for such work, a practice the jury determined earlier this week is a violation of the state's minimum wage law. On Friday, they announced how much back pay was owed.

"This was about fair wages for work," says Adam Berger, an attorney with Schroeter Goldmark & Bender, which brought a class action on behalf of former detainees. "These detained immigrants are just emblematic of other workers in this economy who are in exploitive labor situations."

One former detainee who joined the suit is Nigerian-born Goodluck Nwauzor. He says he was detained at the Tacoma facility for eight months, starting in 2016, as he waited for his asylum claim to be processed. During that time he cleaned showers for a dollar a day. He says the GEO Group didn't force people to do such work, but he saw little choice.

"You have to do it, to get the money to get the stuff you need, or also make a call to your friends and family members," Nwauzor told NPR on Friday. "It's unfair. Because the amount of the job, or the kind of job we do, is beyond what they were paying us."

The class action was consolidated with a separate lawsuit brought by the state of Washington, which accused the GEO Group of violating state labor law and enriching itself unjustly.

The GEO Group argued that the detainees were not employees under Washington law, and that the state itself pays less than minimum wage to prisoners in its corrections facilities. The state minimum wage law exempts people living in "state, county or municipal" detention facilities. The Tacoma site is federal, and owned by a private company.

The company made $18.6 million in profits from the Tacoma detention center in 2018, and it acknowledged in a previous trial that it could have paid detainees more.

The company did not respond to NPR's request for comment.

The jury awarded the former detainees $17.3 million in back pay on Friday evening. It's still up to U.S. District Judge Robert Bryan to determine how much money the company must pay the state on its claim of unjust enrichment.

Berger says about 10,000 former detainees are eligible to share the back pay.

"We're going to have a big job ahead of us, locating all of these folks to try to give them the money that they've earned," he says. "And quite frankly, some of them we might not be able to find."

He says attorneys will petition the court separately for their fees.

Nwauzor, who was one of the lead plaintiffs in the class action, received asylum in 2017, and now lives in suburban Seattle.

READ MORE

As communities across the country grapple with the role police play in schools, new research serves to highlight the issue's complexities. (photo: Carl D. Walsh/Getty Images)

As communities across the country grapple with the role police play in schools, new research serves to highlight the issue's complexities. (photo: Carl D. Walsh/Getty Images)

Investigation: As Minneapolis Weighs Police Dept's Fate, Records Show School Cops Had Lengthy History of Discipline, Civil Rights Complaints

Mark Keierleber, The 74 Million

Keierleber writes: "As a talent show came to a close in the winter of 2007, hundreds of children and parents poured out of a Minneapolis high school only to be met by the piercing blast of gunfire."

As a talent show came to a close in the winter of 2007, hundreds of children and parents poured out of a Minneapolis high school only to be met by the piercing blast of gunfire.

North High School students and their parents rushed back inside and police raced to investigate the commotion. But the guns and bullet shells were nowhere to be found. A campus security guard who helped in the search, they’d soon learn, had already stashed them in his pockets and, later, his wife’s purse.

The weapons turned up that evening outside a gas station a few blocks from the school where the security guard, Kelly Woods, got into a heated altercation with his ex-girlfriend. Police, who observed witnesses screaming “They’ve got a gun,” arrested Woods at gunpoint.

For Woods, the arrest added to a lengthy criminal record, including drug trafficking, auto theft, armed robbery and a federal firearms conviction, which didn’t stop him from becoming a security guard in charge of protecting students. For police officer Charles Adams III, the security guard’s colleague at North High, the ordeal became part of his internal disciplinary record. When officials pursued fresh criminal charges against Woods, Adams pressed them to “go easy” on a man he described as a “good guy,” according to police records obtained by The 74. The move infuriated the lead prosecutor on the case. Assistant County Attorney Diane Krenz said it was the first time in her decades-long career an officer had pressured her to go lenient on a suspect, according to the records. The last thing the community needed, she said, were “more guns on the North Side.”

The incident linked to Adams — the decorated North High School football coach and now-former cop with a national reputation — is included among dozens of allegations and disciplinary findings against campus police officers recently stationed inside Minneapolis public schools that include claims of police brutality, racial discrimination and domestic violence.

In one incident, officers were accused of beating and arresting a man for carrying a handgun despite having a concealed carry permit. In another, police were accused of pounding in a man’s face because he littered the crust from a slice of pizza. Both incidents ended with court settlements, a common outcome in police brutality lawsuits against Minneapolis officers that has cost taxpayers millions of dollars. The city paid $235,000 in 2010 to settle a lawsuit after a man said at least six officers punched, kicked and tasered him during a traffic stop. One of the accused officers became a school-based cop, a position he held until last year.

After George Floyd was murdered in 2020 at the hands of a Minneapolis officer, the city school board was quick to end its longstanding contract with the police department for campus cops, a move that some critics said was politically motivated. Floyd’s death put a national spotlight on police brutality and excessive force. The 74 obtained public officer misconduct records and court files to explore whether similar interactions between police and students had transpired in Minneapolis classrooms — and if such incidents may have contributed to the school board’s decision to cut ties with the department. Ultimately, few of the records involved on-campus incidents or youth, but the lengthy list of allegations and disciplinary findings — many alleging violence on the part of police — raised separate questions about how the officers wound up inside schools in the first place. They also offer new context for an ongoing national debate about the role police should play in schools and whether they’re best equipped to ensure students are safe.

Ben Fisher, an assistant criminal justice professor at Florida State University whose research focuses on the efficacy of school-based police, said the Minneapolis officers’ disciplinary and court records “seemed quite problematic.”

“Schools contain some of our most vulnerable people in society,” Fisher said. “If we are putting officers in there who have abused their power in some way outside of the school, it’s a very scary proposition to imagine that track record following them into schools.”

Minneapolis Police Department spokesman Garrett Parten said officers’ disciplinary records were considered before they were stationed inside schools, but he declined to comment on specific allegations or findings against officers. School resource officers took the job to build trust between youth and police, serve as positive role models and ensure children could learn in a safe environment, he said in an email. Effects of the school board’s decision to end the school resource officer program, he said, “will become evident over time.”

Dozens of school districts across the country severed their ties with police after Floyd’s murder, but broader police reform efforts have so far faltered. In Washington, legislation that sought to improve transparency around officer misconduct and make it easier to prosecute bad cops, among other changes, failed as bipartisan negotiations broke down.

Locally, Minneapolis voters will consider a ballot question next week that could remove from the city charter a police department that’s long been accused of sweeping officer misconduct under the rug. As the school district navigates its first year without a full-time police presence in classrooms, the unprecedented ballot measure would create instead a city Department of Public Safety that would use a “comprehensive public health approach” and employ police officers only “if necessary.”

National industry “best practices” recommend collaboration between police and education leaders when stationing officers inside schools, but researchers who study the efficacy of school resource officers said that little evidence exists about how such selection processes actually work. Anecdotally, the job is highly regarded in some districts and officers compete for the position, Fisher said. In other places, being stationed in schools is “a punishment where police are put there if they can’t cut it on the streets.”

‘Completely out of control’

The 74 obtained Minneapolis Police Department misconduct records for the 24 officers assigned to public schools for the five years prior to Floyd’s murder. Of those, 21 officers faced 105 internal complaints, 11 of which resulted in discipline of varying severity. Those records span the duration of officers’ employment with the department. Separately, the officers stationed in schools were named in federal lawsuits on at least two dozen occasions, according to an analysis of court records.

The police disciplinary issues range in seriousness. One officer who worked in the schools was cited in 2019 for unintentionally firing his service rifle while responding to a call about a man with a gun, and another was given a letter of reprimand after getting arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol. In two of the 11 cases which resulted in official department action, officers were disciplined for using excessive force.

About half of the Minneapolis officers who were sued or disciplined remain on the force, according to a department spokesperson.

Among them is Mukhtar Abdulkadir, who has faced 11 internal complaints — two that resulted in discipline — and two federal lawsuits. He reported to work as a school resource officer as recently as 2017, district records show. Records suggest the officer has a tendency to respond violently when under stress.

In 2010, a young Ethiopian immigrant accused Abdulkadir of choking and punching him and calling him a racial slur after he was pulled over and cited for riding a bike at night without a light, a citation the man called “stupid.” A federal lawsuit following the incident was ultimately settled. Abdulkadir and his attorneys couldn’t be reached for comment.

In 2011, Abdulkadir was arrested on assault and terroristic threat charges after his then-wife accused him of punching her in the ribs, smothering her face with a pillow and hitting her in the face with the butt of his service pistol. Abdulkadir was fired for the incident but was rehired with back pay after his former wife retracted her allegations. Yet according to his disciplinary file, internal investigators believed her decision to recant was obvious: “Only if he is reinstated will she obtain child support when they divorce.” Additionally, internal records note that domestic abuse victims often “take the blame” because their abusers maintain control over them.

Abdulkadir was also accused of repeatedly punching a man outside a car wash in 2013. The man honked at the officer because he was next in line at the automatic car wash but hadn’t moved forward, according to a complaint in a federal lawsuit. In response, Abdulkadir was accused of punching the man repeatedly before charging him with disorderly conduct, according to the lawsuit that also ended with an undisclosed financial settlement.

Then, in 2014, Abdulkadir was reprimanded for becoming irate after he failed firearms training. Officers who witnessed the outburst reported feeling afraid because he “was completely out of control” and had easy access to a gun.

“That night I truly believed that at any time he could grab his weapon, load it and use it against officers,” a police sergeant told internal investigators. In a less controlled environment, the sergeant said he could see a situation where Abdulkadir would “completely lose control of everything and harm himself, other officers or the public.”

District records show Abdulkadir was assigned to Minneapolis campuses a year later, including Andersen United Middle School and Seward Montessori School.

When officers protect their own

The disciplinary findings against Adams put the storied coach and second-generation Minneapolis cop on defense, a position he isn’t used to playing. After the school board voted to break with the police department, some students at North High School, the predominantly Black school where Adams worked as a school resource officer, rallied to support him. So did the school’s principal.

On two occasions after Floyd’s murder reinvigorated the Black Lives Matter movement, The New York Times examined how his roles as a football coach and a Black police officer placed him on both ends of the debate on policing in America. As Adams told a local newspaper, “I wear blue, but I’m Black.”

The records suggest that Adams, who left the police department last year and is now head of team security for the Minnesota Twins, was willing to go to great lengths for a colleague accused of a serious crime, a reality he acknowledged in an interview with The 74. Woods, the North High School security guard, and his attorney couldn’t be reached for comment.

“I stood up for him as a character,” Adams said. “I never said that it was OK for what he did.”

North High School Principal Mauri Friestleben, who has been outspoken against the school board’s decision to cut ties with the police, similarly stood behind Adams. With officers in schools, she said she witnessed a “healthy discourse about what real protecting and serving looked like,” including situations where campus cops helped students avoid arrests. “I have no reservations about my public support” of Adams, she wrote in an email, and called the officer “a protector” who came to the job “with multiple dimensions and this may be just one of them.”

Adams sought to downplay his own disciplinary record, arguing that police leaders and prosecutors overreacted to his intervening in Woods’s criminal case. Prior to becoming a school security guard, Woods was convicted of armed robbery in 1992 and became ineligible to possess a firearm. Six years later, police arrested Woods with a gun outside a Minneapolis Greyhound bus station. Woods, who is Black, unsuccessfully accused the officers of racial discrimination when they stopped him while investigating drug and gun trafficking, according to court records.

Adams said that Woods was a positive force in the community and shouldn’t be defined by the years he spent in prison. After the shooting outside North High, Woods wasn’t trying to keep the guns for himself, Adams maintained. Instead, Woods knew the students involved in the shooting and didn’t want them to get arrested. Woods recognized them as gang members, according to court documents.

“I took it as him looking out for those two kids,” said Adams, who added that he didn’t observe the shooting himself. “He took [the guns] from them and said ‘Get out of here,’ one of those types of deals because that’s just the type of person that he is.”

Adams scoffed at the suggestion from Krenz, the prosecutor, that his defense of Woods conflicted with his role in keeping the community safe. Krenz declined to comment for this article. Adams said she wouldn’t know where North High was if it “smacked her in her face.”

“I don’t want to hear that,” Adams said. “I hear so many people talk about what should be good for our community. They have never stepped one foot inside of it.”

‘Good ol’ boy network’

Internal police records obtained by The 74 likely offer a significant undercount of officer misconduct. Just 2.7 percent of complaints resulted in discipline between 2013 and 2019, according to a recent investigation by the Minnesota Reformer, a nonprofit news outlet. After lengthy investigations, disciplined officers often received letters of reprimand or brief suspensions.

A pattern of officers protecting their peers allowed abuses to remain under the radar until it went to court, the investigation found. Three years before he murdered Floyd, for example, Derek Chauvin hit a 14-year-old boy with a flashlight and pinned him to the ground for 17 minutes. The incident, which could be seen as a precursor to Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck, is excluded from his public records.

The 74 sought comments from Minneapolis officers previously stationed inside schools, school board members, the city and state police unions, an attorney who represents many officers in misconduct litigation, the city and the county attorney’s office. Each declined to comment or didn’t respond to interview requests.

Among the lawsuits against officers placed in schools, civil rights attorney Zorislav Leyderman represented the plaintiffs in six. Police misconduct incidents that occur outside schools, he said, should influence whether those involved are assigned as school resource officers. Leyderman cited the allegations as contributing to a larger culture in the city where many Minneapolis residents fear the police.

“They don’t want to interact with law enforcement because they’re worried that if they do, they’re going to get injured,” he said. The allegations against the officers stationed in schools “should have been looked into, both the lawsuits and these internal complaints.”

Oftentimes, he said police misconduct remains outside the public eye because officers are “coached” following incidents, a practice the department has maintained isn’t a form of official discipline. The department was sued and accused of illegally withholding misconduct records, including in cases of serious wrongdoing. In a 2015 U.S. Department of Justice report, investigators found that Minneapolis police used coaching to resolve more than a quarter of complaints over a six-year period.

Local parent advocate Khulia Pringle, who helped the school district hire security staff to replace sworn police last year, said that officers’ disciplinary records should be a major factor when placing them inside schools. However, that history only reinforced her belief that police have no place walking hallways.

“In any other situation, when we need the cops, we call them,” said Pringle, a Minnesota-based representative of the National Parents Union. If they’re going to be there, there “should have been more protocols in place as to which officers are in schools,” she said.

Adams said he was surprised to see the allegations against other police officers who worked in the schools, and although negative interactions between cops and youth have occurred, he couldn’t recall any recent instances that could’ve motivated the school board’s decision to end its police contract. Yet Adams, who said he can “speak freely” now because he’s no longer a cop, portrayed his former department as one where officer misconduct is routine.

“It’s the good ol’ boy network,” he said. “You’ve got guys who are in the police department that treat people wrong on purpose and you can see it.”

‘Part of the game’

As communities across the country grapple with the role police play in schools, new research serves to highlight the issue’s complexities. On one hand, the officers reduce some forms of violent crimes like fights, according to the research. At the same time, their presence prompts a dramatic uptick in suspensions and arrests — especially for students who are Black. Little academic research explores the types of officers who are more effective than others in schools.

But being named in a federal lawsuit shouldn’t be automatically disqualifying, said school safety consultant Kenneth Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services in Cleveland. Filing civil rights lawsuits against an arresting officer is all “part of the game,” he said. Police misconduct suits often end in settlements, yet Trump said the final results should become part of the equation when making school resource officer assignments.

“If you’re a police officer and you’re doing your job on the streets, there’s a really good chance you’re going to get sued somewhere in your career,” said Trump, a proponent of school-based policing. “But there should be some sort of baseline criteria and screening set by your police administration before that pool of officers is ever presented at that next step to your school people.”

Parten, the Minneapolis police spokesman, said that all officers were eligible to apply for the school resource officer program and were interviewed by a panel of police department and school district officials. The police chief had the final say in hiring decisions. Parten said he collaborated with education officials when crafting a statement for this article, but Minneapolis school district spokeswoman Julie Schultz Brown didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

“Candidates were presented with scenario-based questions designed to evaluate critical thinking skills necessary for a school setting and further examined each individual’s understanding of the challenges and rewards associated with the position,” he said.

Policing in Minneapolis remains contentious in the larger community, and voters will soon decide whether to go in a completely new direction. Ahead of next week’s election, a recent poll of likely voters suggests the question of whether to dismantle the traditional police department will be close. Black voters were less likely than white voters to support the idea.

A similar course change — to remove cops from Minneapolis schools and replace them with district security staff — was ultimately detrimental, Adams maintains. “Crime is outrageous” at North High School, he said, and the security team hired to replace sworn officers is “stretched thin.”

And even though he defended a security guard who he said sought to keep kids out of the criminal justice system, the former cop said stationing police in schools was an effective strategy to catch suspected criminals.

“A lot of kids would obviously show up to school and investigators and a lot of police knew the kid would be there,” Adams said. “That was a good way to get bad guys.”

READ MORE

A vigil for slain journalists in Mexico. (photo: Yuri Cortez/AFP/Getty Images)

A vigil for slain journalists in Mexico. (photo: Yuri Cortez/AFP/Getty Images)

Mexico: Journalist Shot to Death in Chiapas

teleSUR

Excerpt: "On Thursday, Mexican journalist Freddy Lopez was shot dead outside his home in San Cristobal de las Casas in the state of Chiapas."

The Committee to Protect Journalists informed that the world’s deadliest countries for the practice of journalism are Somalia, Syria, Iraq, South Sudan, Afghanistan, and Mexico.

On Thursday, Mexican journalist Freddy Lopez was shot dead outside his home in San Cristobal de las Casas in the state of Chiapas.

Accompanied by his family, the editor of Jovel magazine was arriving at his home when he was attacked by an unknown person and died almost immediately. The police searched unsuccessfully for the attacker. The Attorney General's Office began investigations to find those responsible for the crime and to clarify its causes.

Lopez, who was a correspondent for El Universal in Guatemala in the 1990s, worked for the Central American magazine Panorama and was in charge of the Notimex office in Chiapas. He also was head of information in the newspaper Novedades and published articles in the magazine Proceso.

On Thursday, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that Mexico ranks sixth in the Global Impunity Index, which assesses countries according to the persistence of the lack of punishment in murder cases. Currently, the world’s deadliest countries for journalists are Somalia, Syria, Iraq, South Sudan, Afghanistan, and Mexico.

“The CPJ’s global index calculated the number of unsolved journalist murders as a percentage of each country’s population… It only tallies murders that have been carried out with complete impunity, while it does not include those where partial justice has been achieved,” GMA Network recalled.

"CPJ defines murder as a deliberate killing of a specific journalist in retaliation for the victim’s work. This index does not include cases of journalists killed in combat or while on dangerous assignments, such as coverage of protests that turn violent," it added.

According to this 2021 CPJ report, the rate of attacks on Mexican journalists has increased permanently from September 2011 to August 2021. In the last two years, at least four journalists were killed for reasons directly linked to their communication work. In that period, however, the Mexican justice only convicted the murderers of journalists Javier Valdez and Miroslava Breach.

Over the last 21 years, 142 Mexican journalists have been assassinated for reasons related to their professional work. This figure could be even higher since the Interior Secretary assures that 47 journalists have been assassinated since the administration of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) began in 2018.

READ MORE

The cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) is considered one of the most endangered primate subspecies on the planet. (photo: AZ Animals)

The cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) is considered one of the most endangered primate subspecies on the planet. (photo: AZ Animals)

Deforestation Soars in Nigeria's Gorilla Habitat: 'We Are Running Out of Time'

Orji Sunday, Mongabay

Sunday writes: "When 57-year-old Linus Otu was a child, each dawn arrived with the chatter of monkeys and occasional belches of gorillas from the mountain that overlooks his small bungalow home in the village of Kanyang II in southeastern Nigeria's Cross River state. He recalled peering up at the foggy, forested mountains, uncertain what to make of his noisy animal neighbors."

When 57-year-old Linus Otu was a child, each dawn arrived with the chatter of monkeys and occasional belches of gorillas from the mountain that overlooks his small bungalow home in the village of Kanyang II in southeastern Nigeria’s Cross River state. He recalled peering up at the foggy, forested mountains, uncertain what to make of his noisy animal neighbors.

One morning, while exploring the banks of the Afi River, Otu came upon a mother chimpanzee bathing its infant. “It acted like a human, like a mother will care for her baby,” Otu told Mongabay.

But when Otu walks beside the river today, once a watering hole for diverse wildlife, the cacophony of the forest is different, quieter. Decades of habitat loss have taken their toll on Cross River’s rainforest, and even the state’s protected areas haven’t been able to escape the intertwined forces of agriculture, poverty and war.

Afi River Forest Reserve (ARFR), named after the river that bisects it into two unequal halves, was established in the 1930 to protect more than 300 square kilometers (about 116 square miles) of rainforest near Nigeria’s border with Cameroon. The reserve, now managed by the government’s Cross River State Forestry Commission harbors many species, including blue duikers (Philantomba monticola), bay duikers (Cephalophus dorsalis), red river hogs (Potamochoerus porcus), yellow-backed duikers (C. silvicultor), mona monkeys (Cercopithecus mona) and African brush-tailed porcupines (Atherurus africanus).

The region is also home to critically endangered Cross River gorillas (Gorilla gorilla diehli) that occasionally inhabit ARFR but prefer to live more permanently in nearby Cross River National Park and adjacent Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary (AMWS). However, despite becoming an official protected area in 2000, poaching has persisted in AMWS; according to Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), an infant gorilla was killed by a snare trap in 2010; in 2012, two gorilla carcasses were found at a hunter’s camp.

The Cross River gorilla remains Africa’s most endangered ape, with fewer than 300 individuals believed to remain in the wild, all of which are relegated to a small, mountainous portion along the Nigeria-Cameroon border. Around 100 – a third of the entire subspecies – are found in a patchwork of three adjoining protected areas in Nigeria: AMWS, the Mbe Mountains Community Sanctuary and the contiguous Okwangwo division of Cross River National Park.

Poaching isn’t the only threat that the gorillas face. Habitat loss is on the rise in Cross River, with satellite data from the University of Maryland (UMD) showing that more primary forest was cleared in 2020 than in any year prior since measurement began in 2002. Overall, Cross River state lost nearly 5% of its primary forest cover between 2002 and 2020.

As with many of Nigeria’s forest reserves, ARFR has been beset by increasing deforestation. The reserve has had the highest rate of forest loss in the region, according to a 2018 study published in the Open Journal of Forestry, which found that annual deforestation in ARFR increased twelve-fold between 1986 and 2010. UMD satellite data show the reserve lost another 4% of its primary forest cover between 2011 and 2020. Like Cross River state, 2020 saw ARFR’s highest levels of deforestation since the beginning of the century – and preliminary data suggest the reserve is experiencing another year of intense habitat loss.

Habitat in flames

2021 started with a bang in Cross River state as the region saw some of its highest fire activity in years, according to data from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The data show several fires spread and broke out in ARFR.

Local sources said the 2021 fire season was one of the worst they’ve ever experienced in the region, dwarfing even the outbreak of 2002. Blazes in ARFR lingered for several weeks, defying firefighting efforts from local communities, said George Mbang, a WCS ranger who works in adjacent Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuar. Mbang said he and his team were eventually able to snuff out the fires, but not before dozens of farms and tracts of forest were lost in and near the two protected areas.

Sources said the origins of the fires remain unclear but suspect that some of them may have been started by farmers clearing land for new fields. Satellite imagery shows many of the fires that invaded ARFR occurred near areas that had been previously cleared.

Fighting forest fires in ARFR is difficult. Rangers are challenged by a lack of resources and varied, inaccessible terrain, with peaks soaring to 1,300 meters above sea level. Mbang said unstable rocky outcrops can become dislodged as fire burns the vegetation holding them together and can crush firefighters and houses as they careen downhill. He said that the only option is to raze the edges of affected areas to restrict further spread.

Some communities around ARFR have proposed new, stiffer penalties for those linked to fire outbreaks, Otu told Mongabay. He said the new clause, when fully enshrined, will require those found responsible to forfeit their own cocoa farms to the victims of fire incidents, in addition to monetary fines.

Farmers told Mongabay that fires that spread onto land they already used for agriculture deplete nutrients in the soil, forcing them to seek – and clear – replacement farmland in protected areas. Research has shown that fire replenishes some, but not all, nutrients in the soil as it breaks down organic matter. Critically, fire has been found to reduce nitrogen in soil, and farmers told Mongabay that it was easier for them to clear more forest for new farmland than use fertilizer to replace nitrogen and other nutrients.

Poverty and conflict

During a visit to ARFR in Aug. 2021, Mongabay observed several trucks loading logged timber day and night in and near ARFR, destined for urban centers where a growing demand for timber products is increasing the pressure on dwindling habitat in Nigeria’s forest reserves. Many areas of ARFR were pockmarked by deforestation and strewn with logs as distant rattles of chainsaws mingled with the moist forest breeze.

Cocoa trees bearing yellow and green pods spread across the undulating landscape in and around the reserve. It was the peak of farming season, with farmers continuing to clear new farms even as rains fell, burning stumps and applying chemicals to control crop pests and disease. At numerous homesteads, farmers were collecting harvested cocoa pods and bagging dried beans. Bagged cocoa beans were then weighed and loaded onto trucks at depots, where they’ll be transported to nearby cities before being exported abroad.

The search for new agricultural land to grow cocoa, plantain, banana and cassava is driving forest loss in ARFR, said Otu, who is a former community leader of Kanyang II. “As you enter you start clearing as much as you have the power to clear,” he said. “Almost every portion of the reserve has been claimed.”

Cocoa farming became commercialized fairly recently in surrounding communities, spurring a new wave of demand for larger farming spaces. Farmers, backed by wealthy cocoa merchants from urban centers, competed to dominate the emerging market primarily by farming larger portions each year. The surge of cocoa farms in the likes of ARFR, linked to the growing demand for the product in the international market, has made Nigeria the world’s fourth largest cocoa producer.

With most surrounding communal forests nearly depleted, community residents say customary practice allows them to permanently own any portion of land they can clear and farm in ARFR – despite official laws that prohibit it. Several farmers told Mongabay that they have cleared more land in the reserve than they need in the short term, hoping to either transfer the land to their children, use it for new farms or rent it out to migrant cocoa farmers for a fee. In addition, locals said that by taking possession of large expanses of land, they stand a chance of receiving eviction payouts if the government steps in to reclaim remaining forest in the reserve.

The underlying factor driving deforestation in ARFR and elsewhere in the country is poverty. Nearly half of Nigeria’s 190 million people live in extreme poverty, and unemployment reached a record 33% in 2020, according to figures from the National Bureau of Statistics. With few legal options to make a living and with the country’s population expected to double by 2050, Nigerians say they are forced to turn to the forests to make a living.

The situation has deteriorated to the point at which resource wars have broken out, local sources told Mongabay. Power conflicts and boundary disputes over access to timber, cropland, bushmeat and other forest products have intensified in recent years as resources diminish in and around ARFR and communities fight to control what remains.

Customary negotiators once relied on traditional boundaries such as trees, rivers and oral practices to delineate borders between local communities and mitigate disputes. But 61-year-old Leonard Akam said this is no longer sufficient to deter bloodshed, and multiple sources said that resource wars between communities have led to the deaths of at least 100 people.

Akam is calm in his demeanor, often witty with words and brutally honest. He was the head of the Boje clan when a dispute over communal boundaries within the reserve with neighboring clan Nsadop led to a brutal communal war in 2010. “So many lives were lost,” Akam told Mongabay. Local authorities temporarily restored peace by deploying the military, complete with a panel of inquiry and an arbitration committee. But Akam said the government’s approach was half-hearted and ineffective.

One such war erupted in 2018 between the Boje and Iso Bendeghe communities. After a year of conflict in which at least two people were reportedly killed, the Nigerian government again deployed the military in an effort to restore peace in the area.

This time intervention was more successful. A fragile truce was struck between Boje, Nsadop and Iso Bendeghe as well as other communities such as Bouanchor and Katabang. Boundary tracing, aided by old documents retrieved from the archive, is in progress. Meanwhile, communities around the reserve are in dialogue to avoid further bloodshed.

Despite this progress, Akam said sustainable peace depends on addressing the root causes of the crisis: unemployment, lack of infrastructure, poor educational systems – and the poverty that underpins them all.

Running out of time

ARFR has long been too degraded to provide permanent habitat for Cross River gorillas but researchers still consider it a lifeline that connects resident populations in AMWS and Cross River National Park. However, ARFR may be losing its capacity as a habitat corridor. A 2007 study published in Molecular Ecology found evidence of “low levels” of gene flow between gorilla populations, suggesting that while individuals were still able to move between populations to breed, it wasn’t happening very often. A related study published in 2008 in the American Journal of Primatology found Cross River gorillas have less genetic diversity than western gorillas (G. gorilla gorilla), putting them at greater risk of extinction.

“These results emphasize the need for maintaining connectivity in fragmented populations and highlight the importance of allowing small populations to expand,” the study states.

A 2008 survey of the southeastern portion of ARFR conducted by WCS in 2008 found that primary forest covered just 24% of the surveyed area.