Nomura, JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs Received a Cumulative $8 Trillion from the Fed’s Emergency Repo Loans in Fourth Quarter of 2019

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 17, 2022 ~

The Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 ordered the Government Accountability Office (GAO), an investigative body for Congress, to audit the Fed’s alphabet soup of emergency lending programs conducted during and after the 2008 financial crisis. The GAO found that a cumulative $16.1 trillion had been pumped out to Wall Street firms by the Fed – at super cheap interest rates. The GAO provided data for the peak amounts outstanding and also a cumulative total.

Why is a cumulative total essential and relevant? Because one institution in 2008, Citigroup, was insolvent for much of the time the Fed was flooding it with cheap loans. (Under law, the Fed is not allowed to make loans to an insolvent institution.) And when an insolvent institution is getting loans rolled over and over by the Fed for a span of two and a half years, at interest rates frequently below one percent when the market wouldn’t loan it money at even double-digit interest rates, it’s highly relevant to know the cumulative tally of just how much Citigroup got from the Fed. According to the GAO, that tally came to $2.5 trillion for just some of these Fed loan programs. (See page 131 of the GAO study here.)

The academic scholars that compiled the Fed’s loans during the financial crisis for the Levy Economics Institute also provided cumulative tallies. Their tally, which included additional Fed bailout programs not included by the GAO, came to $29 trillion.

The largest of the Fed’s emergency loan programs to Wall Street trading houses in 2008 was called the Primary Dealer Credit Facility, or in alphabet-soup-speak, PDCF. It made a cumulative tally of $8.9 trillion over a span of more than two years. Just three Wall Street trading firms received 64 percent of that money: Citigroup, a cumulative $2.02 trillion; Morgan Stanley, a cumulative $1.9 trillion; and Merrill Lynch, a cumulative $1.78 trillion.

Back in 2008 there was no law that forced the Fed to ever reveal the names of the banks that borrowed this money from the Fed and the amounts borrowed. The Dodd-Frank legislation made these disclosures by the Fed the law of the land. But Dodd-Frank set up a two-tier level of disclosures. If the emergency lending program was under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, as the Primary Dealer Credit Facility was, the Fed would have to reveal the firm names and amounts borrowed one year after the program had been terminated. But emergency operations conducted through the Fed’s so-called “open market” operations would not have to reveal the names of the firms and amounts borrowed until two years after the loans were made.

Thus, it appears that in 2019 the Fed decided to make astronomical sums available to Wall Street’s trading houses not through a Primary Dealer Credit Facility (which it set up again in March 2020) but through its repo loan open market operations.

The repo loan market is an overnight loan market where banks, brokerage firms, mutual funds and others make one-day loans to each other against safe collateral, typically Treasury securities. Repo stands for “repurchase agreement.”

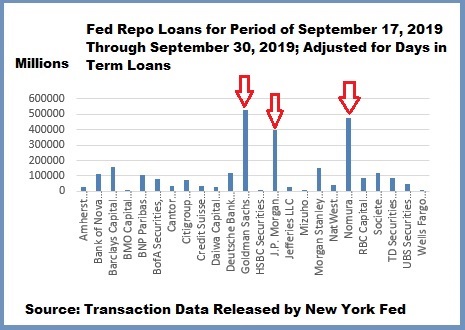

On September 17, 2019 the overnight loan rate spiked from an average of about 2 percent to 10 percent – signaling that one or more firms were in trouble. So the Fed effectively became the repo loan market on September 17, 2019 and exponentially grew the amount of loans it was making over the following months. Its repo loans lasted until July 2, 2020, by which time it had re-established the alphabet soup list of emergency loan programs from 2008.

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington D.C., an independent federal agency, outsources the vast majority of its emergency lending programs to the New York Fed, one of 12 privately owned regional Fed banks. The largest shareowners of the New York Fed are the following five Wall Street banks: JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Bank of New York Mellon. Those five banks represent two-thirds of the eight Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) in the United States. The other three G-SIBs are Bank of America, a shareowner in the Richmond Fed; Wells Fargo, a shareowner of the San Francisco Fed; and State Street, a shareowner in the Boston Fed.

We have now crunched the numbers for the New York Fed’s emergency repo loans for the periods in which it has thus far released the names of the borrowers: the last 14 days of September 2019 and the full fourth quarter of 2019. (The New York Fed is releasing the transaction data on a quarterly basis here. You have to delete the Reverse Repo transactions.)

After crunching the numbers, it now appears that the New York Fed may have intentionally thrown in a dizzying array of term loans to this one-day (overnight) repo loan market in order to disguise the fact that the trading units of the largest banks it supervises were the largest borrowers.

For example, the New York Fed offered one-day repo loans every business day but periodically also added 14-day, 28-day, 42-day and other term loans. Let’s say a trading firm took a $10 billion loan for one-day but on the same day took another $10 billion loan for a term of 14 days. The 14-day loan for $10 billion represented the equivalent of 14-days of borrowing $10 billion or a cumulative tally of $140 billion.

If we simply tallied the column the New York Fed provided for “trade amount” per trading firm, it listed only $10 billion for that 14-day term loan and not the $140 billion it actually translated into.

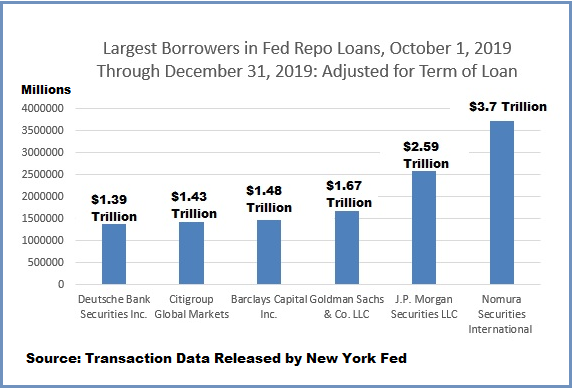

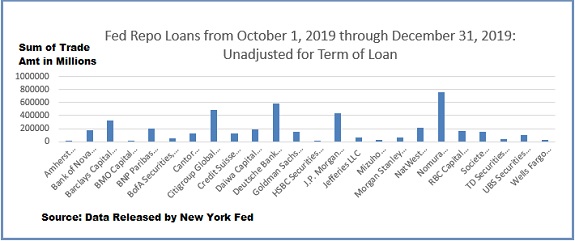

When we tallied the New York Fed’s “trade amount” column for the fourth quarter of 2019, the New York Fed’s repo loans came to $4.5 trillion. But when we set up a new column that adjusted the loans by the number of days in the term, the Fed’s repo loans for the fourth quarter of 2019 came to $19.87 trillion, or 4.4 times the “trade amount” column.

Just six trading houses received 62 percent of the $19.87 trillion, as illustrated in the chart above. The parents of three of those firms, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Goldman Sachs, are shareowners of the New York Fed. The New York Fed is allowed to electronically create the trillions of dollars it loans at the push of a button.

Below is the chart that shows the understated amounts borrowed using just the New York Fed’s “trade amount” column for the fourth quarter of 2019. Below that we’ve also adjusted the Fed’s repo loans to account for the number of days in the term for the period of September 17, 2019 through September 30, 2019. (The Fed released this transaction data separately at the end of September in 2021.) It shows, convincingly, that from the get-go of the financial crisis in 2019, the same three firms were at the center of the borrowing.

The Fed originally tried to pass the problem off to corporations draining liquidity from the financial system by withdrawing their quarterly tax payments in the fall of 2019. But among the largest depository banks in the country where those quarterly tax payments would be held are Wells Fargo Bank and Bank of America, in addition to JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup’s Citibank. But as the chart below shows, neither Wells Fargo nor Bank of America seem to be having any major liquidity issues. In addition, three of the largest borrowers (Nomura, Barclays and Deutsche) are the trading affiliates of foreign banks. Are we really expected to believe that U.S. corporations are holding their quarterly tax payments with the trading units of foreign banks?

The Fed’s audited financial statements show that on its peak day in 2020 the Fed’s repo loan operation had $495.7 billion in loans outstanding. On its peak day in 2019, the Fed’s repo loans outstanding stood at $259.95 billion. It should be noted that there was no COVID-19 pandemic crisis in the U.S. in 2019. The first case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was reported by the CDC on January 20, 2020.

It’s long past the time for the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee to haul the relevant parties to a hearing, put the witnesses under oath, and get to the bottom of this second clandestine Wall Street bailout by the Fed in the span of 11 years.