06 December 21

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

ON DONATIONS IF WE SLIP WE’RE DEAD — RSN financial stability has been badly damaged by months of reduced fundraising returns. If we slip now the organization is done. The good news is that it doesn’t take much to right the ship. Take a moment to donate what you can afford. That will do it. Sincere thanks to all.

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News

Sure, I'll make a donation!

Julia Rock and David Sirota | Six Things You're Not Hearing About Inflation

Julia Rock and David Sirota, Jacobin

Excerpt: "The current conversation about inflation serves corporate interests."

The current conversation about inflation serves corporate interests.

Inflation is punching far above its weight in the minds of Americans immersed in louder and louder media alarms about rising prices — often stripped of any context or policy prescriptions that might complicate the narrative, embarrass the rich, or spotlight the predatory business practices of wildly profitable corporations.

Have you noticed that all the media fearmongering about wage inflation hasn’t mentioned the soaring salaries of corporate executives?

Have you noticed how most of the headlines about price increases haven’t mentioned medicine, health insurance, and housing prices that have been skyrocketing for years?

Have you noticed that stories about expensive essential goods don’t mention the record profits of the companies selling them?

That’s not an accident. The discourse is being rigged and manipulated by media and political voices so that the conversation serves the business interests and donors benefiting from the status quo.

Make no mistake, higher prices are annoying, and for 70 percent of households with an annual income below $40,000, they are causing financial hardship. For some people, the rate of inflation has outpaced wage increases. But the bottom 60 percent of earners have more money in their pockets than they did pre-pandemic, even after accounting for inflation, when wage increases and government programs like COVID relief checks and the Child Tax Credit are included. That spending successfully cut poverty nearly in half.

Why is inflation overshadowing these positive indicators? In part, it’s because — as social scientists have long observed — people tend to have a negative gut reaction to increased prices, since they don’t intuitively connect inflation to increasing wages or aforementioned government benefits that may contribute to inflation.

That lack of context is exacerbated by corporate media.

Like the pundit freakout over worker shortages last summer, the conversation about inflation is being driven by corporate lobbying groups like the US Chamber of Commerce, whose self-serving talking points are echoed across the mediascape — and amplified by ever-more cartoonish sensationalism.

Instead of reporting context, corporate media is busy finding families that drink forty-eight gallons of milk a month to talk about milk inflation (which, by the way, was higher a decade ago) or people who drive older Cadillac Escalades to talk about gas prices (which were also higher a decade ago). Corporate media outlets are also falsely predicting food and labor shortages, writing stories based on the inflation concerns of anonymous CEOs, and falsely claiming that inflation is being caused by wage increases for rank-and-file workers.

As a result, even though people think the job market is better than it’s been in decades, consumer confidence is plummeting — likely due to price increases largely caused by sector-specific shortages and a global energy crisis, according to a Conference Board Consumer Confidence survey. Meanwhile, even though people are spending no more of their income on gas than pre-pandemic, and far less on gas than a decade ago, President Joe Biden’s low approval ratings seem inextricably tied to rising gas prices over the past ten months.

In this Great Inflation Scare of 2021, we’re not talking about the following six issues at play in the economy.

1. Inflation at the Very Top

Perhaps the most important point being overlooked by the corporate media is that inflation is being driven by the greed and power of wealthy people and corporations.

As banks notch record profits, executives are finding ways to “juice” their salaries. There’s a 20 to 30 percent “private jet inflation” caused by booming demand from rich people who saw their wealth soar during the pandemic. Rich people have so much spare cash laying around they are buying digital art for tens of millions of dollars, creating new speculative bubbles. Corporations are seeing their largest profits since 1950 (and still jacking up prices of essentials). Over the last forty years, the top 1 percent have seen income gains far outpacing inflation, while workers’ wages have flatlined.

And yet, John Deere workers are being scapegoated for demanding wage increases because it might cause a wage-price spiral (even though the company is reporting record profits this year). An MSNBC host lamented that rank-and-file workers’ “higher wages are one of the contributing factors to inflation.” Even the 2021 survival checks green-lit by the American Rescue Plan Act are being blamed for inflation.

This all shows that the inflation scare, like any crisis moment, is being cynically exploited by corporate actors to entrench their own power and further erode the power of working people.

2. Corporate Consolidation

Relatedly, unchecked corporate consolidation is making it easier for corporations to cite the inflation crisis to unilaterally jack up prices, even as their huge profit margins show they don’t actually need to.

For many essential goods, ranging from diapers to meat to insulin, there are just a few companies that dominate the market for that product. When the one or two companies that make a product raise prices, consumers have no choice but to buy essential goods at that higher price.

Monopolies can also artificially restrict supply in order to keep prices high, explained the American Economic Liberties Project’s Matt Stoller, leading to shortages. This is why some corporate leaders seem to be celebrating higher prices in their earnings calls.

This concentration of corporate power also makes supply chains more vulnerable to the bottlenecks that are now contributing to inflation.

3. Wars And Fossil Fuels

There seems to be an unspoken rule among the corporate media that when it comes to fear mongering about government spending, the deficit, and inflation, the US military budget doesn’t matter and isn’t worth discussing. In fact, intervening in overseas conflicts, killing civilians, and siphoning public money to military contractors have all proven to be major contributors to inflation. The Vietnam War, for example, wasn’t just long, bloody, and unnecessary, but it was also inflationary, economists agree.

Running a fossil fuel economy also subjects American consumers to the price volatility associated with the geopolitics of a global energy market. “Clean energy is much less economically volatile than fossil fuels, and its ever-declining costs aren’t prone to the same boom and bust cycles that have defined the age of oil,” wrote the New Republic’s Kate Aronoff in a piece about how transitioning away from fossil fuels could help tackle inflation.

You never see this fact discussed in corporate media. It appears journalists are too busy combing gas stations for people who are annoyed about how expensive it’s getting to fill up their tank-size SUVs.

The New York Times, for example, interviewed an auto repair shop owner last month who “recalled recently filling his 2003 Cadillac Escalade and seeing the price go above $100, where it used to be $45.”

This is a ridiculous editorial decision when you consider that a 2003 Cadillac Escalade gets thirteen-fourteen miles per gallon. Were no Hummer owners available? Unmentioned: The last time it would have typically cost $45 or less to fill up a 2003 Escalade fuel tank was in 2003.

4. Addressing Health Care and Housing Costs

The government has other tools at its disposal to manage rising cost of living and exorbitant corporate profits. Biden, for example, has claimed that the investments in health care, housing, and other sectors in the Democrats’ Build Back Better social spending and climate bill will help address inflation in the longer term. His claim is partially true.

In truth, lawmakers have ways to address the fact that prices have risen faster in health care over the past thirty years than in any other sector. After promising for years to pass legislation to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices, Democrats have included a significantly watered-down drug pricing provision in Build Back Better. While the new provision will lower out-of-pocket costs for certain drugs and impose price inflation caps, Democrats could do much more than what they’ve settled on.

Biden could also use march-in rights to lower the cost of patented drugs when companies are keeping costs prohibitively high — a process by which the Health and Human Services Secretary could license patented drugs developed using federal funding to other manufacturers. Democrats could also fight to implement a single-payer health system, which, even the Republican-led Congressional Budget Office agrees would reduce costs and massively expand health care access.

Housing is also increasingly unaffordable, due to a myriad of factors including restrictive zoning laws and decades of underinvestment in public housing. Biden claims Build Back Better would solve housing inflation, but it likely won’t, as Jerusalem Demsas reports for Vox, because it doesn’t adequately tackle the lack of housing supply that is causing high prices.

Representative Ilhan Omar (D-MN) and Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) have introduced a bill to put $40 billion into the Housing Trust Fund to build more affordable housing, an essential antidote to housing inflation. But so far, the legislation hasn’t gone anywhere.

5. The Fed Tradeoff

The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate to use monetary policy to maintain price stability and achieve maximum employment. The bank manages that balancing act mainly by adjusting interest rates — the cost of borrowing money — and buying government bonds.

In August 2020, Fed chairman Jerome Powell announced at the central bank’s annual symposium in Jackson Hole that the bank was changing its approach to inflation. For decades, the Fed had kept interest rates high, leading to low inflation or even deflation, and more importantly kept unemployment high enough to suppress the bargaining power of workers. But Powell said that he would keep interests low until the labor market reached full employment, and wasn’t worried that it might cause high inflation.

Now, Powell is under pressure from inflation “hawks” to taper bond purchases and raise interest rates sooner.

The pressure campaign seems to be having an impact. Fed Governor Christopher Waller implied in a recent statement to reporters that workers taking advantage of a tight labor market was making him concerned about inflation. Similarly, Biden Treasury secretary Janet Yellen also recently expressed some concern that rising wages could be a problem if inflation persisted.

But if the Fed raises interest rates, making it more expensive for businesses to borrow money and discouraging spending, it will slow down the labor market recovery.

Higher than usual inflation is less devastating than mass unemployment, which would be the impact of an interest rate hike, or cutting back social spending in an attempt to keep prices down, according to economists J.W. Mason and Lauren Melodia.

“After 2007, the United States experienced many years of high unemployment and depressed growth, thanks in large part to a stimulus that most now agree was too small,” they recently wrote in the Washington Post. “Policymakers belatedly learned that lesson, and as a result, the United States is making a rapid recovery from the most severe economic disruption in modern history. Yes, inflation is a real problem that needs to be addressed… But as bad as inflation is, mass unemployment is much worse. Given the alternatives, policymakers made the right choice.”

6. Price Controls

Congress could tackle inflation without triggering mass unemployment if lawmakers are actually concerned about rising cost of living for working Americans. It could also do so without killing or further gutting the Democrats’ Build Back Better reconciliation bill, even though the US Chamber of Commerce is arguing that the legislation would make matters worse. Instead, lawmakers could address inflation by implementing price controls, meaning placing legal limits on the amounts that prices of certain goods can increase.

As a recent report from the Roosevelt Institute detailed, the United States has used price controls during wartime in the past, and Congress could grant Biden the statutory authority to do so now.

One benefit of price controls, according to Todd Tucker, the author of the Roosevelt Institute report, is that they would prevent corporations from using the guise of inflation to jack up prices beyond the increased cost of input and report fat profits, as they have been doing in recent weeks.

“The thing about crises is that the normal forces of supply and demand don’t work well,” Tucker told The Daily Poster. “Firms who have a lot of power in the economy know that, and can use that information to charge people much more than the increased costs that they are experiencing because of the crisis.”

Price controls can tackle that problem, said Tucker: “The government and the public aren’t at the mercy of private forces here.”

READ MORE

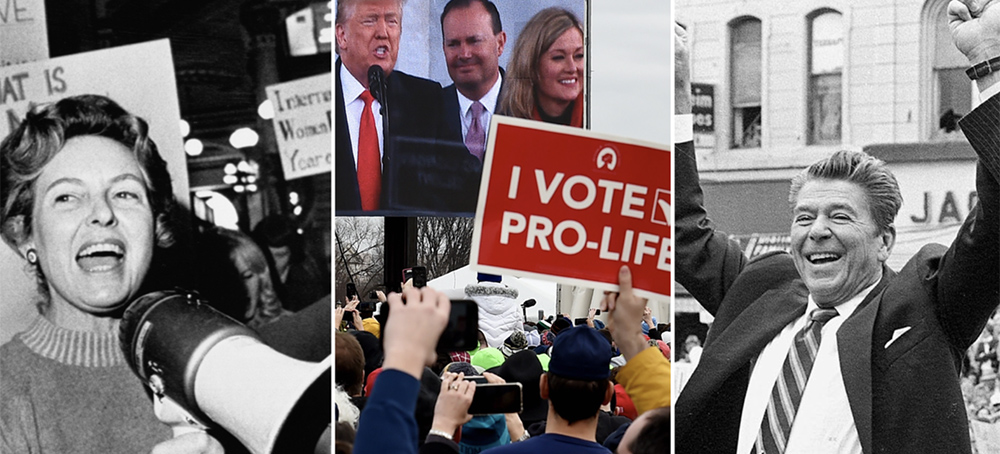

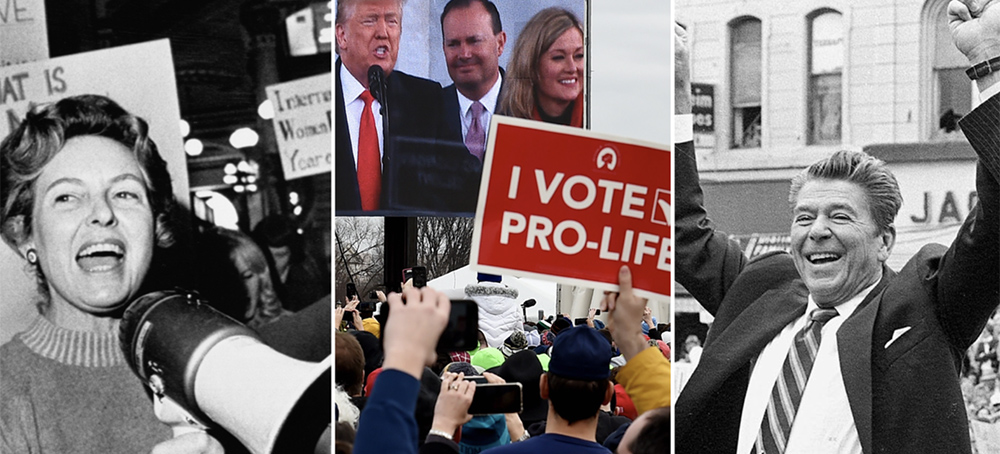

From left to right: Phyllis Schlafly, anti-abortion supporters of Donald Trump, Ronald Reagan in 1980 campaigning on an anti-abortion platform. (image: Getty Images/AFP)

From left to right: Phyllis Schlafly, anti-abortion supporters of Donald Trump, Ronald Reagan in 1980 campaigning on an anti-abortion platform. (image: Getty Images/AFP)

‘Historical Accident’: How Abortion Came to Focus White, Evangelical Anger

Jessica Glenza, Guardian UK

Glenza writes: "Public opinion on abortion in the US has changed little since 1973, when the supreme court in effect legalized the procedure nationally in its ruling on the case Roe v Wade."

A short history of the Roe decision’s emergence as a signature cause for the right

Public opinion on abortion in the US has changed little since 1973, when the supreme court in effect legalized the procedure nationally in its ruling on the case Roe v Wade. According to Gallup, which has the longest-running poll on the issue, about four in five Americans believe abortion should be legal, at least in some circumstances.

Yet the politics of abortion have opened deep divisions in the last five decades, which have only grown more profound in recent years of polarization. In 2021, state legislators have passed dozens of restrictions to abortion access, making it the most hostile year to abortion rights on record.

This schism played out in the US supreme court on Wednesday, when the new conservative-dominated bench heard oral arguments in the case of Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the most important abortion rights case since Roe.

In somber arguments, justices questioned whether the state of Mississippi should be allowed to ban nearly all abortions at 15 weeks gestation, nine weeks earlier than the current accepted limit. While the ruling, expected by the end of June next year, is far from a foregone conclusion, justices in the conservative majority appeared to signal their support for severely restricting abortion access, a right Americans have exercised for two generations.

The divisive question among the conservative majority appeared to be whether abortion should be restricted to earlier than 15 weeks, weakening Roe, or if the precedent set in Roe should be overturned entirely.

Summarizing Mississippi’s argument, the conservative justice Brett Kavanaugh, who was controversially nominated to the court by Donald Trump in 2018, said “the constitution is neither pro-life nor pro-choice … and leaves the issue to the people to resolve in the democratic process.” If the issue is returned to the states, 26 states would be “certain or likely” to ban or severely restrict abortion access.

The religious right in the US has been laying the foundations of this decisive challenge to abortion rights for years. According to historians and researchers, it has taken decades of political machinations for the campaign to reach this zenith. The movement has intersected with nearly every major issue in American politics for the last five decades, from segregation to welfare reform to campaign finance.

The conservative anti-abortion movement “was a kind of historical accident”, said Randall Balmer, a professor of American religious history at Dartmouth University and author of the recently released book Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of the Religious Right.

It wasn’t until Republican strategists sought to “deflect attention away from the real narrative”, which Balmer argues was racial integration, “and to advocate on behalf of the fetus”, that largely apolitical evangelical Christians and Catholics would be united within the Republican party. Balmer argues that advocacy was nascent in 1969.

Although the supreme court decision in Brown v Board of Education called for an end to racial segregation in schools in 1954, many schools continued de facto segregation 14 years later.

Then, the supreme court weighed in again, and ordered schools to integrate “immediately”. This prompted white southerners to form “segregation academies”, whites-only private Christian schools which registered as tax-exempt non-profit charities. African American parents in Mississippi sued, arguing this was taxpayer-subsidized discrimination. They won, and in 1971, tax authorities revoked the non-profit status of 111 segregated private schools.

In Balmer’s view, revoking the non-profit status of segregated private schools catalyzed evangelical Christian leaders, but even in the early 1970s defense of racial segregation was not a populist message. However, defense of the fetus could be.

Republican operations began to test abortion as a vessel for the collective anxieties of evangelical Christians, and Roe as a shorthand for government intrusion into the family after the sexual revolution of the 1960s. Eventually, abortion became the reason for evangelicals to deny the Democratic president Jimmy Carter, himself an evangelical Christian, a second term.

Evangelical opposition to abortion “wasn’t an anti-abortion movement per se”, said Elmer L Rumminger, an administrator at the then whites-only Christian college Bob Jones University, said in Balmer’s book. “For me it was government intrusion into private education.”

At the same time, the anti-feminist Republican activist Phyllis Schlafly was connecting anxiety about women’s changing roles in society with abortion. In a 1972 essay, she described the feminist movement as “anti-family, anti-children, and pro-abortion,” and the writing of contemporaneous feminists as “a series of sharp-tongued, high-pitched whining complaints by unmarried women”.

By the 1978 midterm congressional elections, Paul Weyrich, one of the architects of modern conservatism, was testing abortion as a campaign issue with evangelical Christians with a small fund from the Republican National Committee. Roman Catholic volunteers distributed hundreds of thousands of leaflets in church parking lots in Iowa, New Hampshire and Minnesota, and their efforts prevailed. Four anti-abortion Republicans ousted Democrats.

The groundwork laid by Schlafly and Weyrich made “Roe shorthand for a host of worries about sex equality and sexuality”, wrote Mary Ziegler, a law professor at Florida State University and author of After Roe: The Lost History of the Abortion Debate.

“Even as late as August 1980, the Reagan-Bush campaign wasn’t certain abortion would work for them as a political issue,” said Balmer. However, as Reagan sailed to victory, he was carried in part by religious voters hooked on the promise of a constitutional amendment to ban abortion. When a constitutional amendment failed, a new strategy took hold: control the supreme court.

Historians said segregation was only one part of a complex and multifaceted movement, which has long seen itself as a human rights campaign. By the 1970s, “there was an anti-abortion movement which was influential and pretty effective in the states that was ready for the new right to work with,” said Ziegler.

In the coming years, Reagan would recast the politics of reproduction through a new racist prism, as he introduced the mythical stereotype of the “welfare queen”. The image allowed politicians to portray “all single mothers as persons of color and all persons of color as dependent on public assistance”, wrote the reproductive rights activists Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger in their 2017 book Reproductive Justice: An Introduction.

The image divorced family wellbeing and welfare support from abortion access and rights. Thus, the “broad middle ground” of issues that anti-abortion and pro-choice voters agreed on became “firmly partisan”, said Laura Briggs, author of How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics, and professor and chair of women, gender and sexuality studies at University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

By the 1990s, anti-abortion activists had professionalized. So called “right to life” organizations rallied the base, and religious law firms dedicated themselves to fighting abortion in courts. The supreme court weighed in on abortion again in 1992, in another watershed case called Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey. The case allowed states to restrict abortion, as long as such restrictions did not create an “undue burden” on the right to abortion and served the purpose of either protecting the woman’s health or unborn life.

States hostile to abortion passed “Trap” laws, or targeted regulations of abortion providers, which required abortion clinics to become the “functional equivalents of hospitals”, according to legal scholars. States instituted 24-hour waiting periods for abortion, state-mandated inaccurate information and invasive sonograms.

Many clinics went out of business as they struggled to meet the expensive new requirements, and pregnant people struggled to obtain abortions as they had to travel further and spend more to find a provider.

These laws would also play an outsized role in the Dobbs hearing. Conservative justices debated whether they could keep the “undue burden” standard while jettisoning a central tenet of Roe, that women can terminate a pregnancy until a fetus can survive outside the womb, or “viability”.

“Why is 15 weeks not enough time?” asked Chief Justice John Roberts, a conservative, in the hearings.

The politics of reproduction spurred new debates on acceptable restrictions on birth control, stem cell research and sex education during the George W Bush administration. But it was the election of Barack Obama, America’s first Black president, that supercharged Republican opposition.

In 2010, the Tea Party swept the midterm elections. More extreme candidates entered Congress and statehouses through the practice of challenging incumbents in districts gerrymandered to be reliably Republican. And, in a decision not typically thought of as an anti-abortion victory, the chief counsel for National Right to Life successfully argued a supreme court case that would unleash vast sums of dark money into American elections – Citizens United v Federal Election Commission.

“The anti-abortion movement, over time with other conservative allies, worked to change things like the rules of campaign finance for the conservative movement,” said Ziegler. “Anti-abortion lawyers played an integral part in cases like Citizens United.”

By the time Donald Trump ran for president, evangelical Protestants had become more anti-abortion than the Catholic voters who were once the bedrock of anti-abortion advocacy. Seventy-seven per cent of white evangelical Christians say the procedure should be illegal, compared with just 43% of Catholics, according to the Pew Research Center.

Trump harnessed the anger of white evangelicals for a victory in 2016, with a mix of hardline anti-abortion politicsand xenophobic nativism. Trump abandoned his 1999 stance as “very pro-choice”, saying there should be “punishment” for women who have abortions, and promised to nominate conservative supreme court justices who would “automatically” overturn Roe v Wade.

Today, overwhelmingly white “Christian nationalist” voters believe their religion should be privileged in public life, a goal to be attained “by any means necessary”, according to social researchers such as Indiana University associate professor Andrew Whitehead.

Supreme court decisions are notoriously difficult to predict, but abortion rights activists believe Wednesday’s hearing shows that conservative justices are ready to significantly weaken or perhaps overturn Roe v Wade.

If that happens, young, poor people of color will disproportionately suffer, forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term. Such an outcome is so severe human rights advocates have said state abortion bans would violate United Nations conventions against torture and place the US in the company of a shrinking number of countries with abortion bans.

On Wednesday, the court’s three outnumbered liberal justices argued neither the science, the enormous consequences of pregnancy nor the American polity had changed since the court last decided a watershed abortion rights case. But, because of the work of anti-abortion politicians, the makeup of the court’s bench had.

“Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception that the constitution and its reading are just political acts?” asked the liberal justice Sonia Sotomayor. “I don’t see how it is possible.”

READ MORE

In this 2010 photo, Army Lt. Gen. Lloyd Austin appears at a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on his reappointment to be commander of the U.S. forces in Iraq. (photo: Rod Lamkey Jr./AFP/Getty Images)

In this 2010 photo, Army Lt. Gen. Lloyd Austin appears at a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on his reappointment to be commander of the U.S. forces in Iraq. (photo: Rod Lamkey Jr./AFP/Getty Images)

“Crisis of Accountability”: Pentagon Reopens Probe of Syrian Airstrike That Killed Dozens of Civilians

Democracy Now!

Excerpt: "Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has ordered a new investigation into one of the deadliest U.S. airstrikes in recent years after the New York Times exposed an orchestrated cover-up by U.S. military officials to conceal the attack."

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has ordered a new investigation into one of the deadliest U.S. airstrikes in recent years after the New York Times exposed an orchestrated cover-up by U.S. military officials to conceal the attack. The March 2019 airstrike killed dozens of women and children during a bombing of one of the last strongholds of the Islamic State of Syria. Evidence has shown that U.S. military officials spent two-and-a-half years covering up the attack by downplaying the death toll, delaying reports, and sanitizing and classifying evidence of civilian deaths. “This is not the case of one little mistake,” says Priyanka Motaparthy, director of the Counterterrorism, Armed Conflict and Human Rights Project at Columbia Law School. “This really points to a crisis of accountability in the Pentagon.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, Democracynow.org, the War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has ordered a new high-level inquiry into one of the deadliest known U.S. airstrikes in recent years. In March 2019, a secretive U.S. special operations unit called Task Force 9 bombed the Syrian town of Baghuz, killing dozens of women and children. The bombing came as the U.S. was attacking one of the last strongholds of the Islamic State in Syria. The military then spent two and a half years covering up the attack, even though the high civilian death toll was almost immediately apparent to military officials. One legal officer even flagged the attack as a possible war crime. U.S. military officials downplayed the death toll, delayed reports and sanitized and classified evidence of civilian deaths. U.S.-led coalition forces also bulldozed the blast site. The Pentagon reopened its investigation only after The New York Times exposed what happened.

This comes as U.S. Central Command acknowledged Sunday that civilians may also have been killed last week when a U.S. drone strike targeted an alleged Al Qaeda leader. We are joined right now by Priyanka Motaparthy, director of the Project on Armed Conflict, Counterterrorism and Human Rights at Columbia Law School. She recently co-wrote a letter to Defense Secretary Austin calling on him to review the civilian death toll of U.S. air strikes in Yemen in light of the military coverup in Syria. Professor, welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us. Why don’t we start off with Syria, what it took to get this official investigation. Explain exactly what you understand happened in March of 2019.

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: Thank you for having me. What we understand at this point really comes from The New York Times reporting and what they reported is that in March 2019, 70 individuals in Baghuz, Syria, were killed, a large number of them women and children. Immediately after that airstrike, it was reported by at least one Air Force lawyer as a potential war crime. Yet in the period between then and now, it seems like every effort to investigate this strike, to report it up the chain, to have very serious review happen of what occurred in this strike, of why these women and children were killed, to determine their status and whether or not this was a war crime, it seems like at every step these investigations failed. The efforts to report them failed. The efforts to draw attention to this very serious incident has failed.

Where we stand now is that the Pentagon has ordered yet another investigation into this incident. But what we really need to see is for this investigation to be credible, for it to be meaningful in any way, it would have to be different from any investigation we have seen at this point, whether that is into what happened in Syria or really any investigation they have carried out elsewhere as well.

AMY GOODMAN: In addition to everything else, the bulldozing of the site of the attack in March 2019, can you respond to this? Also, the Pentagon spokesperson John Kirby saying, “No military in the world works as hard as we do to avoid civilian casualties.” Start off with the bulldozing of the site, clearly to destroy the evidence.

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: First of all, the bulldozing of the site is just one piece of a larger puzzle where again, every aspect of what was supposed to happen failed. The site was bulldozed. Records were apparently—strike logs were apparently falsified or incorrectly registered. The strike was reported but no serious investigation happened. This is not the case of one little mistake, one extraordinary incident, one unique case where one thing went wrong. This really points to a crisis of accountability in the Pentagon. You see that by the fact that, as you said, the strike was bulldozed. That was happening on the ground. In the control room, the reporting did not go as it should have gone. In terms of the record-keeping, that also did not go the way it was meant to go and the way that we are told it goes.

We are told, as you said, that this military does more than any other military in the world to avoid civilian casualties, to prevent civilian casualties, and yet, again and again, that is not what we see. We continue to see civilians getting killed. Thorough investigations are not happening. And that is a key part of what needs to happen. How can you say that your military is doing more than any other military in the world when you are not doing the basic elements needed to properly investigate what happens, why civilians are getting killed and taking the basic steps to ensure that it doesn’t happen again? If you are not properly investigating these types of incidents, then you’re not able to make the corrections you need to make to ensure that civilians don’t get killed in the future. That is why we are looking not just at what happened in Baghuz, but really a 20-year record of civilian harm that has happened in Syria but also in places like Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere around the globe.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to talk about Yemen in a minute, but can you talk about this secretive U.S. special operations unit called Task Force 9 that carried out this particular attack?

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: Really what I know about Task Force 9 again comes from that New York Times article. What we read from that article was that there was a real lack of coordination between that task force and other parts of CENTCOM that were operating in Syria, in the exact same theater, in the exact same very small piece of land at that point in time. What The New York Times reported about Task Force 9 raises some very serious questions. They reported that Task Force 9 repeatedly described its operations as self-defense operations even when there was no incoming fire, even when their troops were not on the ground. A number of other concerns as well were raised in that article. So certainly part of this investigation needs to be looking into what this particular task force was doing, not just in this one incident but really in the variety of incidents, the variety of operations it was carrying out. Because when I read this article, it was very hard to think this is an isolated problem. It does not appear to be an isolated problem because it is hard to imagine these types of mistakes happening just as one-off incidents.

AMY GOODMAN: You mentioned other countries. Let’s talk about Yemen. Late last month, the Saudi-led military coalition launched air raids on the capital Sana’a with reports of massive explosions in the city’s northern neighborhoods. Saudi officials said they were targeting Houthi military sites in retaliation for the rebel group’s earlier drone strikes on sites in Saudi Arabia including a major oil hub in Jeddah. The latest violence coming after thousands of people marched through the streets of Sana’a protesting U.S. support for the Saudi-led military coalition.

PERSON: [translated] We the Yemeni people took to the streets today to denounce the military escalation carried out by America, the economic blockade and the continuation of aggression. We had thought that when Joe Biden took office, he would keep his promises on stopping the war in Yemen and open the airport in Sana’a. It turned out that all that talk was a lie.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what is happening in Yemen, Professor Priyanka Motaparthy.

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: The war in Yemen is in its seventh year. Let’s remember that first of all there is the war that we are all familiar with, that we see daily in the news which has caused the massive humanitarian crisis which has caused thousands of civilian casualties and where the U.S. has played a key role supporting the Saudi-led coalition, support that by the way continues to this day and under this administration. Arms sales to Saudi Arabia continue. Counterterrorism partnerships with the Emirati government continue. There has really been no accountability for what has happened in Yemen, for the war crimes, potential war crimes committed by all parties to this conflict. In terms of the U.S. role there, the U.S. has played a very harmful role in supporting this conflict at the same time as it is trying to serve as a peace broker. So certainly, the U.S. has a lot to do in terms of looking at the harmful nature of its support to the conflict in Yemen and really trying to rejigger what is happening there.

AMY GOODMAN: The role overall of the U.S. in Yemen and who you think needs to engage in this investigation, when we’re talking about one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises in the world?

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: First of all, the U.S. is supporting the Saudi-led military coalition. Let’s also remember that the U.S. is carrying out its own military operations in Yemen, its own counterterrorism operations in Yemen targeting what it describes as Al Qaeda targets, potential ISIS targets. There have also been civilians killed in those strikes that we have reported to the Pentagon. So the U.S. both has work to do looking at its role in supporting one aspect of the conflict but it also has work to do examining and really being transparent about its role directly carrying out military operations in Yemen.

AMY GOODMAN: You mentioned Somalia. What most needs to be investigated there?

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: Again, as in Afghanistan, as in Syria, as in Yemen, in Somalia as well there have been many incidents where independent observers, journalists and human rights groups have reported civilian deaths and civilian injuries as well as other civilian harm in U.S. operations in Somalia. Again, we only see the U.S. admitting fault, acknowledging its role in causing civilian deaths in just a very small fraction of these. There are a number of incidents that they have yet to take a serious look at. We are not aware of any amends, any compensation being paid to families where they have acknowledged causing deaths, killing members of those families.

AMY GOODMAN: Afghanistan, as you mention—we all now know about this drone attack in the last days of the U.S.—during the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan because all the media was in Kabul. Would you say what we saw there and the admissions by the Pentagon because of the reporters on the ground interviewing the family and finding out the number of children who were killed, that this is an example of what has happened in Afghanistan for the last 20 years?

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: That strike was in many ways of a piece with exactly what we have seen in Afghanistan for the last 20 years where incorrect intelligence led to targeting and killing of civilians. In other cases civilians have been killed as collateral damage. But either way, there has been a common response that these strikes were justified, that they were based on good intelligence, that they were righteous, as I believe one general has said. In this case, what was unique is that, as you said, there were journalists in Kabul, excellent investigative journalists who went, who really followed this story up, who visited the family just shortly after that attack, and was able to really piece together in a very detailed way not only who was killed and the fact that seven children were killed, some of them very, very young, but really pieced together the details of who this individual was who was apparently targeted—he was a humanitarian aid worker—and what he was doing the day that the strike was carried out. And to get a counter-narrative from the military in which they alleged he went to some kind of safe house and was packing his car with explosives. What they were able to do was really contrast these narratives, one of supposition and assumption about his hostile intent and one, the reality that he was an aid worker going about his days. What was unusual was that we were able to contrast these narratives and understand the truth of what happened in this case. But there are many, many other cases, families living in more remote areas, whose harm did not happen in such an intense period where there was so much media scrutiny of what was happening in the country and their cases did not get the same level of scrutiny, will not get the same response. That is just a tragedy.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, I want to ask you about the drone whistleblower Daniel Hale. In July, the former U.S. Air Force intelligence analyst was sentenced to 45 months in prison, almost four years in prison. He has pled guilty to leaking government documents revealing the U.S. military’s drone program. In November 2013, he spoke at a drone summit in D.C. organized by CODEPINK.

DANIEL HALE: Before I begin, one last thing. I just would just like to, in a way, say I am sorry. I am not up here for any good reasons. To the people in the audience who are victims or who are families of victims or who have families who live in countries where U.S. militarism and specifically unmanned systems are conducting kinetic strikes, I am sorry. Because I am up here because I was for a time, a short period of time during my military career as an analyst, working with unmanned systems deployed to Afghanistan. At the very least, you all deserve an apology.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Daniel Hale, the drone whistleblower, now being held at a communication management unit in prison at United States Penitentiary, Marion in southern Illinois. Professor Motaparthy, who should be in jail and who should be free?

PRIYANKA MOTAPARTHY: What we want to do is we want to understand why Daniel Hale did what he did, what motivated him and what were the results of his actions. Frankly, what he did was to bring to the American public and to the global public a level of transparency about what was really happening in some of these drone strikes and the way that civilian casualties were being undercounted through the systems that the U.S. military was using. What he disclosed, among other things, was that individuals who are not identified who were killed in these strikes, people who were killed whose identity was not known, they were also been described as enemies killed in action. That is part of the reason that we consistently undercount the number of civilians killed in U.S. military operations overseas and understand them to be more successful or more justified than they may be in reality. Daniel Hale played a key part in exposing that undercounting of civilian deaths. Certainly, he did a great service to the American public in exposing that information.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Priyanka Motaparthy, thank you for being with us, Director of the Project on Armed Conflict, Counterterrorism and Human Rights at Columbia Law School. Next up, ahead of an international meeting on killer robots, the Biden administration rejects calls for an international ban on the use of lethal autonomous weapons. Stay with us.

READ MORE

Attorney Sidney Powell at a news conference on election results in Alpharetta, Ga., in December 2020. (Elijah Nouvelage/Reuters)

Attorney Sidney Powell at a news conference on election results in Alpharetta, Ga., in December 2020. (Elijah Nouvelage/Reuters)

Sidney Powell Nonprofit Raised $14 Million Spreading Falsehoods

Emma Brown, Rosalind S. Helderman, Isaac Stanley-Becker and Josh Dawsey, The Washington Post

Excerpt: "In the months after President Donald Trump lost the November election, lawyer Sidney Powell raised large sums from donors inspired by her fight to reverse the outcome of the vote."

In the months after President Donald Trump lost the November election, lawyer Sidney Powell raised large sums from donors inspired by her fight to reverse the outcome of the vote. But by April, questions about where the money was going — and how much there was — were helping to sow division between Powell and other leaders of her new nonprofit, Defending the Republic.

On April 9, many members of the staff and board resigned, documents show. Among those who departed after just days on the job was Chief Financial Officer Robert Weaver, who in a memo at the time wrote that he had “no way of knowing the true financial position” of Defending the Republic because some of its bank accounts were off limits even to him.

Records reviewed by The Washington Post show that Defending the Republic raised more than $14 million, a sum that reveals the reach and resonance of one of the most visible efforts to fundraise using baseless claims about the 2020 election. Previously unreported records also detail acrimony between Powell and her top lieutenants over how the money — now a focus of inquiries by federal prosecutors and Congress — was being handled.

The split has left Powell, who once had Trump’s ear, isolated from other key figures in the election-denier movement. Even so, as head of Defending the Republic, she controlled $9 million as recently as this summer, according to an audited financial statement from the group. The mistrust of U.S. elections that she and her former allies stoked endures. Polls show that one-third of Americans — including a majority of Republicans — believe that Trump lost because of fraud.

Matt Masterson, a former senior U.S. cybersecurity official who tracked 2020 election integrity for the Department of Homeland Security, said Powell’s fundraising success demonstrates one reason so many people continue to spread falsehoods about the 2020 election: It can bring in cash.

“Business is good and accountability is low, which means we’re just going to see continued use of this playbook,” Masterson said. “Well-meaning folks that have been told that the election was stolen are giving out money that they might not otherwise be able to give.”

Last week, The Post reported that federal prosecutors have subpoenaed financial and other documents related to Defending the Republic and a political action committee by the same name, also headed by Powell. The House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection sees Powell as a leading beneficiary of election-related falsehoods and has been seeking to determine how much money she raised, said a person familiar with the committee’s work who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss confidential conversations.

The group’s financial statement, publicly filed last month in Florida, shows the organization raised $14.9 million between Dec. 1, 2020, and July 31. Of that, it spent about $5.6 million, mostly on legal fees and unspecified awards and grants. It gave $550,000 to help fund the Republican-commissioned ballot review in Arizona, according to a separate accounting by the contractor that led the review.

The group’s assets at the end of that period included nearly $5.3 million in cash and $4 million in mutual funds, the audit says.

The report did not cover the period before Defending the Republic was officially established on Dec. 1. It remains unclear how much Powell, who began urging donations to her cause as early as Nov. 10, may have raised in those first weeks and whether that money was eventually transferred to Defending the Republic.

It is also not clear who, other than Powell, is now running Defending the Republic. Powell and a lawyer for the organization, Howard Kleinhendler, declined to answer detailed questions for this report.

“Defending The Republic is pleased that its audited financials clearly refute and put to rest previously reported allegations of financial impropriety,” Kleinhendler said in a statement to The Post. “Defending The Republic will continue to focus on its important work for #WeThePeople.”

'The president was fascinated'

Powell, a 66-year-old former federal prosecutor from Dallas, first gained celebrity among Trump supporters for representing Michael Flynn, the Trump national security adviser who was charged with lying to the FBI in the Russia investigation. Flynn was ultimately pardoned by Trump.

But after the election, Powell amassed legions of new followers — in two months more than doubling her Twitter following, to 1.3 million — by alleging a vast and fantastical election-fraud conspiracy involving China, Venezuela and secret algorithms inside machines made by Denver-based Dominion Voting Systems.

Trump watched as she repeated those claims on television, said Michael Pillsbury, an informal Trump adviser at the time who was asked to research some of Powell’s allegations. “The president was fascinated,” Pillsbury told The Post. “How could you not be? It just wasn’t true.”

Powell’s wild claims, and the series of lawsuits she promised to file to block Joe Biden’s victory in battleground states, gave Trump a way to believe he could still win, Pillsbury said. And her perceived closeness with the president — at one point, he tweeted that she was part of a “truly great team” of his lawyers — helped to burnish Powell’s credibility with donors. (Trump’s attorneys would later say Powell was acting on her own and not as part of their team.)

A week after the Nov. 3 election, Powell appeared on Fox Business Network’s “Lou Dobbs Tonight” and asked supporters to send money via a new website, defendingtherepublic.org.

At the time, there was no formal organization called “Defending the Republic.” Instead, according to an archived version of the site, it redirected to ldfftar.org, the site for Legal Defense Fund for the American Republic. There, visitors were urged to donate to that group to help Powell “block the certification of the election results so that justice can be done.”

A business using the acronym in that Web address was registered that same day in Delaware and applied to the IRS soon after for nonprofit tax status as a 501(c)4 social welfare organization. Such groups may not make politics their primary focus. The president of that business, Robert Matheson, did not respond to requests for comment.

By Nov. 25 — the day Powell filed the first two of her election-fraud lawsuits in battleground states, in Michigan and Georgia — her own website was live, an archived version shows. It indicated to donors that their money would go to a “legal defense fund” with 501(c)4 nonprofit status. Donors were asked to make checks payable to Sidney Powell P.C., Powell’s law firm.

It was not until Dec. 1, in Texas, that Defending the Republic was incorporated as a business, according to state records. Powell was listed as its agent and as a director, and Flynn and his brother Joseph were added as directors later that month.

Soon, Powell’s lawsuits were flopping, rejected by a series of judges.

Nonetheless, her star remained ascendant. Powell, Michael Flynn and Patrick Byrne — the wealthy founder of online retail giant Overstock — participated in a meeting in the Oval Office on Dec. 18 in which they tried to persuade Trump to appoint her as a special counsel to investigate the election. Trump considered the move but ultimately decided against it, according to previous reports.

Two days after the Jan. 6 siege of the Capitol, Dominion filed a $1.3 billion lawsuit against Powell and Defending the Republic. Dominion argued that she had defamed the company by claiming its voting machines were manipulated to elect Biden.

Powell was raising money during that period by saying donations were needed not just to advance her election-related litigation but also to help defend herself from the legal onslaught.

In late February, a new Defending the Republic was incorporated in Florida.

Mike Lindell, the MyPillow founder who had become a leading voice claiming election fraud, was listed in corporate documents as a director of the Florida-based entity. As soon as he found out, he asked to be removed, he told The Post in an interview.

“They had talked to me in the beginning, and I said, ‘No, I’m doing my own thing,’ ” he said.

Mass resignation

On March 5, Powell called Byrne and asked that he join the enterprise in Florida, Byrne told The Post. Flynn called later that day and said Byrne’s business experience was needed, Byrne said. Byrne, who was at home in Utah and had just finished working on a book about his efforts to investigate the 2020 election, said he agreed to help through July.

Byrne said the Florida group was to be a successor to the Texas entity, which he said Powell had organized hastily and without naming staff. He said the idea was to consolidate efforts and most of the money in the Florida enterprise, leaving the Texas entity with enough funds to defend itself against litigation such as the Dominion lawsuit.

Within several weeks, Byrne, as chief executive, had arranged to lease office space in a squat Spanish-style former bank next to a tattoo parlor in Sarasota, Fla., and hired a small staff.

According to documents reviewed by The Post, that team included Weaver, a co-founder of Jericho March, a Christian group that held pro-Trump marches following the 2020 election. Emily Newman, a lawyer and former White House liaison to the Health and Human Services Department, was its president and also served on the board of directors, along with Joseph Flynn. Michael Flynn was an adviser.

Almost immediately, tension erupted between Powell and the staff. One flash point was a March 22 court filing Powell made seeking to have the Dominion case dismissed. Lawyers for Powell and Defending the Republic wrote that she could not be held liable in part because “reasonable people would not accept such statements as fact,” a position that drew scorn and was soon satirized on “Saturday Night Live.”

In an email to Byrne and others shortly after midnight on April 8, she admonished Defending the Republic employees, accusing them of seeming “panicked” and “immature” in the wake of that filing.

“The job that every American who has donated to our cause expects me to do is to get the truth out in our cases and hopefully win the litigation as I did in Flynn,” Powell wrote. “I need and deserve the full team behind me on this. I MUST run the litigation. That is why I started all of this. We do not have time, money or energy to waste. Drama needs to go.”

In text messages to The Post last week, Byrne rejected Powell’s characterizations of his team and said Powell’s email outburst was a final straw for him and his employees.

Other frustrations were detailed in a resignation email Byrne sent Powell on April 9. Just about everyone was quitting, he wrote, including the executive team and himself. Michael Flynn, the client who had been her original entree into Trump’s world, was also resigning, as was his brother.

Michael Flynn did not respond to a request for comment. Joseph Flynn confirmed that he and his brother resigned in April but declined to comment further.

Byrne wrote in the April 9 email that those who left were upset that Powell was trying to control the organization and was not making good on an agreement to step back and let others lead. He hinted at concerns about the organization’s finances, writing that “a detailed accounting of every donation that has come in to any bank account must be made, and subsequent flows accounted for.”

The Post reviewed four employees’ resignation letters from that day, including the one in which Weaver urged a complete audit of the nonprofit’s finances and access to all bank accounts for any future CFO. “I strongly recommend that any new Chief Financial Officer be promptly given access to all bank accounts,” wrote Weaver, who did not respond last week to a request for comment.

A week after the falling out over the Florida nonprofit, a limited liability company established days earlier by Powell closed on a property in the historic Old Town neighborhood of Alexandria, Va., a brick house that had been an antique shop. The company, 524 Old Towne, paid $1.2 million. The sellers understood that the buyer was Powell and that she intended to establish a law office there, Politico reported and The Post confirmed.

When a reporter visited on Saturday, shades were drawn, a sign promised 24-hour video surveillance and the front steps were cordoned off with a chain and a sign that said “private residence.” A man who was tending to a wreath on the front door declined to identify himself and said no one was home.

Within days of his resignation, Byrne launched a new nonprofit with Michael Flynn, the America Project, which almost immediately began raising money to help fund the ballot review in Arizona. The group ultimately contributed $3.25 million to that effort. Byrne said he has spent nearly $12 million from his own fortune on efforts to expose what he says is a “deeply flawed” election system.

On May 11, a Defending the Republic lawyer sent a five-page letter accusing Byrne of defaming Powell and spending in “wasteful and possibly fraudulent” ways. Threatening legal action, the letter demanded Byrne repay nearly $530,000. Among its accusations was that in hiring Weaver, Newman and two other employees, Byrne arranged for $50,000 signing bonuses that vested — or became permanent — 15 days after the new hires signed employment contracts. All four resigned two days after the vesting date, the letter said.

In a reply the following day, Byrne shrugged off the letter as “comedy-art.” He wrote that the signing bonuses were necessary to persuade people to “forgo jobs and job offers to come to Florida” to work for Powell. He told The Post that he has long used such bonuses in his business operations, and that the employees left the nonprofit not because their bonuses had vested but because of their frustrations with Powell.

Byrne lobbed accusations of his own in the May email, writing that Powell had put $1 million into an operating account but otherwise “blocked all transparency” into Defending the Republic’s funds. And, he added, Powell herself had changed her story about the organization’s finances.

“Sidney told me she had received $15 million, then she used the number $12.5 million,” Byrne wrote. He wrote that he did not know how much money Powell had raised because “she refused all oversight and would not answer questions about it.”

A few days later, in a court filing, Dominion accused Powell of “raiding” the nonprofit’s coffers for her personal legal defense. And about a week after that, the Florida offshoot of Defending the Republic was dissolved.

Defending Sidney Powell

With Flynn and others out, and the election-fraud lawsuits rejected, Defending the Republic was spending considerable time defending Powell and the organization itself.

On June 15, Florida regulators served the Texas-based nonprofit with a complaint alleging that it had not registered to solicit contributions in Florida. Ten days later, the group submitted an application to register, which required detailing its finances.

In that application, Defending the Republic projected contributions of $7.2 million during the fiscal year ending Sept. 30. It disclosed that Powell received an unspecified amount of compensation from the organization.

Powell was deposed the following month as part of a defamation lawsuit filed against her in Colorado by a former Dominion employee. She testified that her law firm had not yet been paid for bringing election-related lawsuits. However, asked whether the firm would receive payment through donations made to Defending the Republic in the future, she replied, “I certainly hope we will.”

The firm was still “trying to collect information that would be needed for anyone to consider compensating us,” Powell said. She said that she had not been paid personally for her work on the election challenges, either. Generally, she said, “I make sure everybody else gets paid for what they have done, and then if there’s any left, I have that as my compensation.”

A lawyer representing Defending the Republic, Brandon Johnson, was deposed the following month in the same case. He said he could not account for donations made before the group was formally registered on Dec. 1, 2020, the period when she was directing people to her website.

“We did not exist,” Johnson said. “We did not have a bank account.”

Asked whether Defending the Republic received a “lump sum” from another organization that had received funds collected before Dec. 1, Johnson said he did not know.

Johnson also said Defending the Republic’s work had broadened to encompass more than just election-related issues, including work on potential challenges to vaccine and mask mandates. In October, the group announced it had filed a lawsuit challenging the U.S. military’s vaccine mandate.

Johnson did not respond to requests for comment.

In August, Defending the Republic reached a settlement with the Florida regulators and agreed to pay a $10,000 fine, documents show. But around the time state scrutiny receded, federal investigators were asking questions.

The grand jury subpoena reviewed by The Post was issued in September, demanding records going back to Nov. 1, 2020, related to Defending the Republic’s fundraising and accounting.

Trump has not met with Powell since leaving the White House, and he complains frequently that she raised money using his name but ultimately did not make it possible for him to return to the White House, according to a Trump adviser who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private conversations.

A Trump spokesman told The Post that Powell has been a “strong supporter” of the former president and added: “Every dollar raised in Republican politics is raised using President Trump’s name, whether or not he’s involved.”

On Thursday, U.S. District Judge Linda V. Parker ordered Powell, Johnson, Newman and six other lawyers involved with a failed suit to overturn the election in Michigan to pay about $175,000 to cover the legal fees of their opponents, state officials and the city of Detroit. Parker had previously called the lawyers’ suit “a historic and profound abuse of the judicial process” and recommended grievance proceedings that could result in disbarment.

Powell and the others complained the fees were unreasonable, but Parker wrote that they were appropriate to deter “similar misconduct in the future.”

She added that she was confident they could afford the fines, given that they had solicited donations from the public to fund their litigation. To illustrate, she pointed to Defending the Republic’s website.

READ MORE

Image of a drone carrying weapons. (photo: Twitter/SIPRIorg)

Image of a drone carrying weapons. (photo: Twitter/SIPRIorg)

US Companies Dominate Arms Sales Worldwide

teleSUR

Excerpt: "On Monday, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute revealed that the United States once again hosted the highest number of arms companies ranked in the top 100, as the arms sales of the 41 U.S. companies accounted for 54 percent of world's top 100's total arms sales."

The U.S.-based companies accounted for 54 per cent of the Top 100’s total arms sales in 2020, the SIPRI report pointed out.

On Monday, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) revealed that the United States once again hosted the highest number of arms companies ranked in the top 100, as the arms sales of the 41 U.S. companies accounted for 54 percent of world's top 100's total arms sales.

Within the SIPRI Arms Industry Database, “Arms sales” are defined as sales of military goods and services to military customers domestically and abroad. All changes in those sales are expressed in real terms and all figures are given in constant 2020 U.S. dollars.

According to the SIPRI latest report on the global arms, U.S. companies continue to dominate the ranking. Together, the arms sales of the 41 U.S. companies amounted to US$285 billion, which meant an increase of 1.9 percent compared with 2019. And since 2018, the top five companies in the ranking have all been based in the United States.

“These U.S. companies accounted for 54 per cent of the Top 100’s total arms sales in 2020,” the SIPRI report pointed out, adding that the combined sales of 26 European-based companies amounted to US$109 billion.

The U.S. arms industry is undergoing a wave of mergers and acquisitions. To broaden their product portfolios and thus gain a competitive edge when bidding for contracts, many large U.S. arms companies are opting to merge or acquire promising ventures.

"This trend is particularly pronounced in the space sector. Northrop Grumman and KBR are among several companies to have acquired high-value firms specialized in space technology in recent years," said Alexandra Marksteiner, researcher with the SIPRI Military Expenditure and Arms Production Programme.

Globally, sales of arms and military services by the industry's 100 largest companies totalled US$531 billion in 2020, an increase of 1.3 percent in real terms compared with the previous year. And this number is 17 percent higher than in 2015, marking the sixth consecutive year of growth in arms sales by the top 100. The report also points out that the arms sales have increased even as the global economy contracted by 3.1 percent during the first year of the pandemic.

"The industry giants were largely shielded by sustained government demand for military goods and services. In much of the world, military spending grew and some governments even accelerated payments to the arms industry in order to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis," Marksteiner said.

READ MORE

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi (left), President U Win Myint (middle) and First Lady Daw Cho Cho in 2018 at the Myanmar Presidential Residence in Naypyitaw. (photo: The Irrawaddy)

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi (left), President U Win Myint (middle) and First Lady Daw Cho Cho in 2018 at the Myanmar Presidential Residence in Naypyitaw. (photo: The Irrawaddy)

Myanmar Junta Sentences Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint to Four Years in Prison

The Irrawaddy

Excerpt: "A Myanmar junta court on Monday sentenced the detained civilian leaders State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint to four years in jail each after the pair were found guilty on charges of sedition and breaching COVID-19 restrictions."

ALSO SEE: Aung San Suu Kyi's Conviction Is a Further Blow

to Democracy in Myanmar

A Myanmar junta court on Monday sentenced the detained civilian leaders State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint to four years in jail each after the pair were found guilty on charges of sedition and breaching COVID-19 restrictions.

Dr. Myo Aung, the ousted Chairman of Naypyitaw Council, was also sentenced to two years for sedition under Article 505(b) of the Penal Code during the hearing in the Myanmar capital Naypyitaw.

Over ten months after Suu Kyi was detained following the junta’s February 1 coup that ousted the civilian National League for Democracy (NLD) government, these are the first verdicts to be handed down against her. She faces another ten cases filed by the military regime, all widely-believed to be trumped-up charges. They include illegal possession of walkie-talkies, corruption cases and alleged breaches of the Official Secrets Act.

With ongoing weekly trials, more verdicts against Suu Kyi are expected later this month. If found guilty, she faces a total of 104 years in prison. Many observers believe the charges to be politically motivated and an attempt by the junta to exclude her from politics permanently.

“The harsh sentences handed down to Aung San Suu Kyi on these bogus charges are the latest example of the military’s determination to eliminate all opposition and suffocate freedoms in Myanmar,” said Amnesty International’s deputy regional director for campaigns Ming Yu Hah.

“The court’s farcical and corrupt decision is part of a devastating pattern of arbitrary punishment that has seen more than 1,300 people killed and thousands arrested since the military coup in February,” she added.

The Amnesty deputy regional director also urged the world not to forget about the thousands of detainees in Myanmar who lack Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s high profile and who are currently imprisoned “simply for peacefully exercising their human rights”.

76-year-old Suu Kyi, 69-year-old U Win Myint and Dr. Myo Aung are currently being detained at an unknown location in Naypyitaw. Although there was no mention of whether they will be sent to prison, it is thought that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi will most likely be kept under house arrest.

She was previously detained under house arrest for almost 15 years by the former military regime, before being released in 2010.

On Monday, the regime court said that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, U Win Myint and Dr. Myo Aung were responsible for the statements of the NLD’s Central Executive Committee issued in the second week of February, according to sources close to the court.

The NLD’s statements on February 7 and 13 denounced the junta for using force to seize power and called on the public to resist military rule.

Article 505(b) of Myanmar’s Penal Code punishes anyone deemed to be causing fear or alarm through an offense against the state or for disturbing “public tranquility” with up to two years in prison.

The State Counselor was also sentenced to two years in jail for breaching COVID-19 restrictions by “waving” at a convoy of NLD supporters passing her Naypyitaw residence ahead of the November 2020 general election. Suu Kyi was wearing a mask and a face shield at the time.

Sources close to the accused said it is likely that they will appeal the verdicts.

On Monday, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was also in court to hear the cases against her for illegal possession of walkie-talkies, under which she is accused of breaking the Import and Export Law and the Telecommunications Law.

Both the defense and prosecution gave their final arguments on the cases.

Suu Kyi faces another charge of breaching COVID-19 restrictions under the National Disaster Management Law on Tuesday, when defense witness Dr. Zaw Myint Maung, the detained former Mandalay Region Chief Minister, is expected to appear.

READ MORE

The Reliant power plant on the wetlands of Ormond Beach is one of more than 400 toxic facilities in California at risk for severe flooding events before 2100. (photo: Ricardo DeAratanha/LAT/Getty Images)

The Reliant power plant on the wetlands of Ormond Beach is one of more than 400 toxic facilities in California at risk for severe flooding events before 2100. (photo: Ricardo DeAratanha/LAT/Getty Images)

Toxic Tides: Climate Change Expected to Cause 400 Toxic California Sites to Flood by 2100

Adam Mahoney, Grist

Mahoney writes: "Communities of color are five times more likely than the general population to live within half a mile of a toxic site that could flood."

Communities of color are five times more likely than the general population to live within half a mile of a toxic site that could flood.

To many Americans, California is defined by its ranging coastline and the sandy beaches and multi-million dollar homes that line its 840-mile stretch. As sea levels continue to rise, it’s no secret then, that the state and its inhabitants are facing a crisis. Hollywood knows this, too, as movie after movie over the last decade has depicted the state’s biggest monuments being taken by the sea.

Lucas Zucker and Amee Raval have bigger fears, however, than the Santa Monica Pier being eaten by the ocean. “People tend to only think about certain destinations, your Malibus and Santa Barbaras — places where celebrities live — these loom large in the public imagination and they shape how policymakers think about sea-level rise,” Zucker, a policy director at Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy, or CAUSE, told Grist.

But, Zucker says, if you actually took the 840 mile trip along the coast, you’d see a different reality. “You would see huge swaths of the coast that have been primarily used for heavy industry, commercial shipping, and toxic military bases,” he explained. And those swaths would be home to majority Black and Latino communities, who are no strangers to the effects of pollution and toxic chemicals.

These two environmental justice activists, whose communities are nearly 400 miles apart, represent a group of California residents in predominantly Black and Latino communities that are five times more likely than the general population to live within half a mile of a toxic site that could flood by 2050, according to a new statewide mapping project led by environmental health professors at UC Berkeley and UCLA (including Grist board member Rachel Morello-Frosch). The study outlines more than 400 hazardous facilities that will face major flooding events by the end of the century, exposing residents to elevated levels of toxic water and dangerous chemicals.

The Toxic Tides project is a first-of-its-kind look at the consequences of sea-level rise on California’s historically neglected environmental justice communities in hopes of urging more federal and state officials to address the expected crisis and transition away from the use of these toxic facilities. “It adds to the urgency,” Raval, policy director at the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, or APEN, told Grist. “We’re equipped and supported now with the data and the research to legitimize our community concern and our vision for a just transition.”

CAUSE, based in Ventura County, and APEN, based in Richmond and Oakland, along with three other environmental justice groups and academic researchers, spent three years combing through federal toxic landmark databases in addition to interviewing community members throughout the entire state to produce the new maps. In all, the coalition created a series of searchable maps and databases to weave together California’s flooding hotspots, which industrial facilities face particular risk, and how lower-income communities of color would be disproportionately impacted. The hotspots they found were unsurprising, Raval told Grist, but nonetheless damning.

“We know who the polluters are. The same big polluters that are destabilizing our climate and driving sea-level rise,” Raval said. “When these toxic facilities flood, they will release even more toxins into our air, water, and land.”

The project outlined three major hotspots: Wilmington, Richmond, and Oxnard, California. In Wilmington, a pocket of South Los Angeles dubbed an “island in a sea of petroleum,” at least 20 industrial facilities, landfills, oil terminals, and incinerators are expected to regularly flood this century. In Oxnard, there are at least nine hazardous sites prone to flooding. Up the coast in Richmond, there are more than a dozen toxic sites at risk, including the Chevron oil refinery, which produces more than 10 million gallons of oil every day, making it the 27th biggest refinery in the country.

Because of the immediate impact to be felt by affected community members, advocates like Zucker and Raval knew how important it was to not just present this data to policymakers, but to the people who live there. This was particularly important in the three areas spotlighted by the project, all of which are home to thousands of non-English speakers. As an environmental justice organizer, Raval says, it’s vitally important to meet people where they are and to meet their specific needs. The group spent months explaining their findings to residents up and down the state in an effort to combine their research “with making those authentic partnerships with community members and advocates who live this reality every day.”

Beyond educating and organizing their communities, the Toxic Tides coalition is actively working to secure funds to help clean up and transition away from these toxic sites, while not reinforcing existing social inequalities and environmental injustices. The groups are advocating for funds set aside in the newly passed Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s Superfund cleanup provisions to be used on many of the sites outlined in the project. On a state level, the coalition is hoping to leverage California’s recent $30 billion budget surplus to be used on these frontline environmental justice communities.

“We can’t be dismissed or not taken seriously anymore,” Zucker said. “Our communities already knew of all this was going on in our backyards, but now we have the numbers and the data visualizations to back it up to scholars, planners, and elected officials.”

READ MORE

Contribute to RSN

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Update My Monthly Donation

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

t’s not as if Americans are entirely unaware of how consolidated our economic landscape is, or that this is a perilous way to do business. The financial crisis taught us how dangerously concentrated our financial sector has become, particularly since Washington responded to the near-catastrophic collapse of banks deemed “too big to fail” by making them even bigger. Today, America’s five largest banks control a stunning 48 percent of bank assets, double their share in 2000 (and that’s actually one of the lessconsolidated sectors of our economy). Similarly, the debate over health insurance reform awakened many of us to the fact that, in many communities across America, insurance companies enjoy what amounts to monopoly power. Some of us are aware, too, through documentaries likeFood, Inc., of how concentrated agribusiness and food processing have become, and of the problems with food quality and safety that can result.

n school, many of us learned that the greatest dangers posed by monopolization are political in nature—namely, consolidation of power in the hands of the few and the destruction of the property and liberty of individual citizens. Most of us probably also learned in seventh-grade civics class how firms with monopoly power can gouge consumers by jacking up prices. (And indeed they often do; a recent study of mergers found that in four out of five cases, the merged firms increased prices on products ranging from Quaker State motor oil to Chex brand breakfast cereals.) Similarly, it’s not hard to understand how monopolization can reduce the bargaining power of workers, who suddenly find themselves with fewer places to sell their labor.