Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Conservatives on the Supreme Court have engineered a system that allows half the country’s population to be stripped of a fundamental constitutional right.

I should caution that the back-and-forth of arguments before the Court can be deceiving. The Obama administration’s difficulty arguing its case in favor of the Affordable Care Act led observers to declare it would be struck down—that didn’t happen. An oral argument can be a preview of how the justices will rule, but it is not always, and so the decision in this case remains unknown until it is handed down. That said, conservative activists had not spent decades attempting to strike down Obamacare. Ending legal abortion in America, though, has long been the main goal of the conservative legal movement.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a Trump appointee, compared the “infringement on bodily autonomy” of forcing a woman to carry to term to vaccine mandates, an argument foiled by the obvious reality that pregnancy and abortion are not contagious. Justice Samuel Alito implicitly compared Roe to Plessy v. Ferguson, the decision holding racial segregation constitutional, as he suggested that cases that had been wrongly decided should be reversed without regard for precedent. Given that Roe and Plessy take opposite views of states’ authority to deny basic liberties to their residents, it was a strange comparison. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, another Trump appointee, made Alito’s invocation of Plessy even more ironic when he offered that the problem was that the Court had been “forced” to “pick sides on the most contentious social debate in American life,” rather than leaving it “to the people, to the states, or to Congress.” Plessy applied this argument to racial segregation, arguing that the states were “at liberty to act with reference to the established usages, customs, and traditions of the people.” Black voters in Louisiana were soon entirely disenfranchised; they were not among “the people” who could determine what those customs and traditions were.

The flowery paeans to democracy began early in the oral argument. Mississippi Solicitor General Scott G. Stewart, defending his state’s strict ban on abortion, began by declaring that precedents guaranteeing abortion rights had “damaged the democratic process” and that “when an issue affects everyone and when the Constitution does not take sides on it, it belongs to the people.”

Perhaps, at first glance, that seems fair. But even setting aside the question of whether people’s fundamental constitutional rights should be settled by popularity contests, and the fact that the Court has previously ruled that the Constitution does take sides on the question of whether women can be forced by the state to carry a pregnancy to term, this argument for democracy is offered in bad faith. Religious freedom is also a contentious issue, and the Roberts Court has shown little modesty in settling such debates as it pleases, in accordance with the customs and traditions of its conservative majority. Furthermore, the Mississippi law’s proponents understand that they have the tools to limit any popular backlash to overturning Roe, and the justices know this because they helped forge those tools themselves.

In 2019, the Supreme Court continued its long streak of antidemocratic rulings, holding that partisan gerrymandering was not unconstitutional. Given the racial polarization of American politics, it is a simple matter for Republican legislators to draw districts that systematically disenfranchise Black voters, and then insist they were discriminating on the basis of party, not race. Plessy is more popularly known, but perhaps the 1898 decision in Williams v. Mississippi is more germane here. In Williams, the Court held that infamous devices intended to disenfranchise Black voters, such as the poll tax, grandfather clause, and literacy test, did “not on their face discriminate between the races.” This case rarely gets included when justices list the Court's more noxious rulings, not only because it is less well known, but because most of the Republican appointees would rather not acknowledge that they have explicitly echoed its reasoning.

The Roberts Court’s jurisprudence has set off a bipartisan race to the bottom, with Democrats and Republicans seeking to rig maps to their advantage in states they control, insulating themselves from popular discontent. This is grim but rational: Under this system, legislative and congressional majorities rest on the ability of lawmakers to disempower their own constituents.

Republicans control more states, however, and geographic polarization allows them to easily draw maps to maintain their power in state legislatures and federal House districts. Should they lose a statewide election, such as a governorship, they can simply strip the Democratic governor of key powers and then wait until a Republican is back in office. If a state referendum goes the wrong way, Republicans can rely on the legislature, or the courts, to nullify it, as they have with Florida’s poll tax (a device explicitly barred by constitutional amendment) or marijuana legalization in South Dakota.

The Court’s gutting of the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance powers means lawmakers are entitled to impose burdens on voting to narrow the electorate where gerrymandering fails. The people can do less and less to ensure that lawmakers’ decisions reflect their preferences, unless the people are consistent Republican voters. Nor are states given a free hand when implementing policies they believe would strengthen democracy—those are not among the contentious issues the Court’s conservative majority feels should be left to the people. If Democrats wish to compete in this environment, they need simply alter their stances to reflect the views of voters whose ballots actually count.

To paraphrase Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg—whose decision not to retire under President Barack Obama was an important factor in this outcome—the Court has turned democracy on its head, allowing lawmakers to choose their electorate, rather than the electorate choosing its lawmakers. Democracy, for our august justices, is just another way of saying: Heads we win, tails you lose. Democrats in Congress have failed to use their fragile trifecta to change this system, and Republicans believe it ensures that the correct people will rule. And so Americans will be governed by it for the foreseeable future.

If the Republican-appointed justices—only one of whom was appointed by a president who originally won the popular vote—sound somewhat cavalier about stripping half the country’s population of a fundamental constitutional right, well, they have good reason to be confident. They have engineered a system that allows “the people,” whose will they invoke with venomous cynicism, little power to respond.

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) speaks to reporters after a meeting with White House officials at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, U.S., October 27, 2021. (photo: Elizabeth Frantz/Reuters)

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) speaks to reporters after a meeting with White House officials at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, U.S., October 27, 2021. (photo: Elizabeth Frantz/Reuters)

In a letter Friday to President Joe Biden, the Vermont Independent called on the president to act immediately to prevent the portion of an “outrageous increase” in Medicare premiums that's attributable to Aduhelm, a newly approved Alzheimer's medicine from drugmaker Biogen, priced at $56,000 a year.

If Biden agreed and found a way to do it, a planned January increase of $21.60 a month to Medicare's “Part B” premium for outpatient care would be slashed closer to $10. The monthly premium for 2022 would drop from $170.10 to about $159.

Biden's massive social agenda legislation takes significant steps to curb prescription drug costs, but Democrats are running the risk that seniors smarting from one of the biggest increases ever in Medicare premiums will turn against them in the 2022 midterm elections. That increase would claw back a big chunk of next year's Social Security cost-of-living allowance, a boost of about $92 a month for the average retired worker, to help cover rising prices for gas and food.

“Biogen’s $56,000 price of Aduhelm is the poster child for how dysfunctional our prescription drug pricing system has become,” Sanders wrote to Biden. “The notion that one pharmaceutical company can raise the price of one drug so much that it could negatively impact 57 million senior citizens and the future of Medicare is beyond absurd. With Democrats in control of the White House, the House and the Senate we cannot let that happen.” A copy of the letter was provided to The Associated Press.

There was no immediate comment from the White House. Biden is planning a speech Monday on the prescription drug provisions of his legislation, including an annual cap of $2,000 on out-of-pocket costs for Medicare recipients, $35 monthly copays for insulin, inflation rebates that would also help people with private insurance, and the first-ever Medicare-negotiated prices. The catch is that those benefits will phase in over time and the Medicare premium hike would hit after the New Year. It's not clear if Biden will address the premiums.

The boost in premiums “could not come at a worse time for older Americans all over this country who are struggling economically," Sanders wrote.

The jump of $21.60 a month is the biggest increase ever for Medicare premiums in dollar terms, although not percentage-wise. As recently as August, the Medicare Trustees’ report had projected a smaller increase of $10 from the current $148.50. Medicare said it had to boost the rate higher to set aside a contingency fund in case the program formally approves coverage for Aduhelm.

Alzheimer’s is a progressive neurological disease with no known cure, affecting about 6 million Americans, the vast majority old enough to qualify for Medicare.

Aduhelm is the first Alzheimer’s medication in nearly 20 years, although it doesn’t cure the disease. The Food and Drug Administration approved the drug this summer, determining that Aduhelm's ability to reduce clumps of plaque in the brain is likely to slow dementia. That decision was highly controversial, since the FDA overrode its own outside advisers. Many experts say Aduhelm's benefit has not been clearly demonstrated. The Department of Veterans Affairs declined to list the medicine on its roster of approved drugs.

Medicare has begun a formal assessment to determine whether it should cover the drug, and a final decision isn’t likely until at least the spring. For now, Medicare is deciding on a case-by-case basis whether to pay for Aduhelm.

Sanders asked Biden to order Medicare to hold off on approving coverage of Aduhelm until there is scientific consensus about its benefits.

Biogen has defended its pricing, saying it looked carefully at costs of advanced medications to treat cancer and other conditions. A nonprofit think tank focused on drug pricing pegged Adulhelm’s actual value at between $3,000 and $8,400 per year — not $56,000 — based on its unproven benefits.

Protesters address the Torrance City Council after Christopher De'Andre Mitchell was killed by police. A prosecutor is reopening an investigation into whether the shooting was justified. (photo: Axel Koester)

Protesters address the Torrance City Council after Christopher De'Andre Mitchell was killed by police. A prosecutor is reopening an investigation into whether the shooting was justified. (photo: Axel Koester)

“To go back and open up all the cases, because you have an absolute grudge against police officers and you’re trying to carry a badge of honor — ‘Look at me, look at me, I’m going to prosecute police officers, I’m going to hold them accountable’ — is turning the table completely upside down,” said Todd Spitzer, the district attorney of Orange County, Calif. A Republican, he is an outspoken supporter of the union-backed campaign to recall his Democratic counterpart in nearby Los Angeles.

“These counties where the ‘woke D.A.s’ are elected,” Mr. Spitzer said, “they are utterly destroying police morale. They are making it impossible to recruit police.”

The number of progressive district attorneys vowing new accountability for police has grown from a first wave of 14 in 2016 to more than 70, representing one-fifth of the U.S. population, according to Fair and Just Prosecution, a group that supports criminal justice reforms. Nearly half of the prosecutors are women, and nearly half are people of color.

Bringing charges against police officers for old use-of-force cases — especially those formally closed by their predecessors — is among the boldest of a range of changes many are seeking. Other policies have included compiling lists of officers deemed discredited as witnesses, requiring a search for corroboration to bring charges of resisting arrest, or reassessing past convictions for potential exonerations or sentence reductions.

Legal scholars say the efforts amount to a decisive test of the criminal justice system. “The stakes are enormous,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the University of California, Berkeley School of Law and a member of a panel advising the Los Angeles district attorney on the review of past use-of-force cases. Noting the election of the progressive prosecutors coincides with increased awareness about officer misconduct, he asked, “Will these combine to reform policing, or will we just revert to where we were?”

The progressive prosecutors reflect “the anti-cop political moment,” said Hannah E. Meyers, director of policing research at the conservative Manhattan Institute. “But if we are serious about reform,” she asked, “is this endeavor really the way to have a system for putting the best cops in those positions and for justice when police act badly?”

Danielle Bellamy outside her home in Salt Lake City. (photo: Kim Raff/ProPublica)

Danielle Bellamy outside her home in Salt Lake City. (photo: Kim Raff/ProPublica)

Utah’s safety net for the poor is so intertwined with the LDS Church that individual bishops often decide who receives assistance. Some deny help unless a person goes to services or gets baptized.

Bellamy, desperate for help, had tried applying for cash assistance from the state of Utah. But she’d been denied for not being low-income enough, an outcome that has become increasingly common ever since then-President Bill Clinton signed a law, 25 years ago, that he said would end “welfare as we know it.”

State employees then explicitly recommended to Bellamy that she ask for welfare from the church instead, she and her family members said in interviews.

Bellamy’s family was on the verge of homelessness. The rent on their apartment continued to rise — a result of Utah being the fastest-growing state in the nation, a trend driven in part by young, upper-middle-class people from California and elsewhere flocking to Salt Lake City’s snow-capped slopes to enjoy its outdoor activities, tech jobs and low taxes.

Worse, Bellamy suffers from a severe autoinflammatory disease and, barely able to stand, is regularly hospitalized for days at a time. Her younger daughter, Jaidyn, had to drop out of high school to care for her, helping her get up, lie down, bathe and change out the wound vacuums attached to her body.

Although maintaining a safety net for the poor is the government’s job, welfare in Utah has become so entangled with the state’s dominant religion that the agency in charge of public assistance here counts a percentage of the welfare provided by the LDS Church toward the state’s own welfare spending, according to a memorandum of understanding between the church and the state obtained by ProPublica.

What that means is that over the past decade, the Utah State Legislature has been able to get out of spending at least $75 million on fighting poverty that it otherwise would have had to spend under federal law, a review of budget documents shows.

The church’s extensive, highly regarded welfare program is centered at a place called Welfare Square, ensconced among warehouses on Salt Lake City’s west side. There, poor people — provided they obtain approval of their grocery list from a lay bishop, who oversees a congregation — can get orders of food for free from the Bishops’ Storehouse, as well as buy low-priced clothes and furniture from the church-owned Deseret Industries thrift store. (Bishops can also authorize temporary cash assistance for rent, car payments and the like; recipients often have to volunteer for the church to obtain the aid.)

Welfare Square was built in 1938 amid the Great Depression, an intentional repudiation by church leaders of government welfare as epitomized by President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. We “take care of our own,” they famously said.

But Bellamy, a Black single mother, is not one of the church’s own — and, unlike the government, a church is often allowed to discriminate based on religion.

The bishop of her local congregation, called a ward, decided that as a precondition of receiving welfare, she would have to read, understand and embrace LDS scripture, Bellamy told ProPublica. Church representatives came by her apartment to decide what individual food items she did and did not need while pressuring her to attend Sunday services, she said.

A church spokesperson, who was not authorized to speak on the record for this story, said that Bellamy’s is just one experience, and there are likely thousands of people across Utah who would swear by the help they’ve received from the church and the guidance they’ve been given toward a more self-sufficient life. He said that because some bishops are more rigid about providing aid than others, some people may wind up in situations like Bellamy’s, but that most in the church default to compassion.

The spokesperson also said that conversations about welfare are between individuals (like Bellamy and others whose stories also appear in this article) and their bishop, and that the church would not break what it regards as a sacred confidentiality.

Bellamy cooperated at first with what was being asked of her. She felt she’d go along “if that’s what I needed to do for some type of goodness to come to my family,” she said, adding that she knew that many in her community had benefited greatly from church welfare and their LDS faith.

Yet she ultimately balked, especially at the thought of being baptized in front of strangers. “I’m sorry,” she said, “I don’t believe in it. And it’s important what I believe in.”

For her refusal, she says, she and her family were denied welfare by the church, just as they had been by the state.

Utah After Welfare Reform

ProPublica is investigating the state of welfare across the Southwest, where the skyrocketing cost of living has made cash assistance for struggling families — an issue that has been brought to the fore again amid debate over President Joe Biden’s child tax credit — more desperately needed than ever.

What the 1996 welfare reform law did, in essence, was dramatically shrink the safety net for the poorest Americans while leaving what aid remained in the hands of individual states, issuing each a “block grant” of federal welfare funding and significant discretion over how to spend, or not spend, the cash.

Ever since, welfare has taken on each state’s personality.

There’s perhaps no better place to examine the past and future of public assistance than Utah, the only state with a private welfare system to rival the government’s. After all, the welfare program of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints served as a model for the welfare reform movement of the 1980s and ’90s, when it was spotlighted by then-President Ronald Reagan during a visit to LDS welfare facilities and in the writings of a young conservative named Tucker Carlson.

The first thing Utah did under the 1996 law was to become increasingly closefisted about helping poor people, creating a labyrinthine system of employment and self-improvement programs that applicants must partake in — including resume-writing seminars, screenings for drug use, counseling sessions and continual paperwork — as well as strict income limits they must not surpass. As of 2019, the state was providing direct assistance to about 3,000 families out of nearly 30,000 living in poverty, a precipitous decline from the mid-’90s, when Utah’s program served roughly 60% of these parents and children. (Utah denied welfare applications, on average, more than 1,300 times every month last year, including during the pandemic.)

A single mother of one here is eligible for $399 a month in state assistance, and only if she has a net income of $456 a month or less.

Utah doesn’t do more for those in need in part because a contingent of its lawmakers, the overwhelming majority of whom are Latter-day Saints themselves, assume the church is handling the poverty issue; they also are loath to raise taxes to do the state’s share, a review of Utah’s legislative history demonstrates.

Thanks to “the LDS Church’s welfare system, literally millions, tens of millions and maybe even hundreds of millions of dollars are saved by the state,” former state Sen. Stuart Reid said in 2011, when the Legislature passed a resolution honoring church welfare on its 75th anniversary.

Indeed, Utah has been counting millions in church welfare work every year as part of the state’s own welfare budget, as a way of meeting the minimum level of effort the state is required to put into addressing poverty so it can collect on federal dollars from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, or TANF. According to the memorandum of understanding between the church and the state, Utah takes credit for a percentage of the hours that church volunteers spend producing and packaging food and clothing for the poor at Welfare Square and similar facilities.

It also claims as state welfare a percentage of the church’s efforts to produce and ship out humanitarian aid in the wake of disasters — aid that may not even help Utahns.

Officials at Utah’s public assistance agency, which after welfare reform was named the Department of Workforce Services, said they do not know how long they’ve had this “third-party” understanding with the church. But they emphasized that it’s legal under the 1996 law and subsequent federal regulations, and that other states engage in the same practice. (That law was the first federal legislation to allow and encourage religious groups to be involved in the provision of government-funded social services, a policy championed by then-Sen. John Ashcroft and later by President George W. Bush.)

ProPublica found that the deal with the church was brokered in 2009 during the Great Recession, when Utah hired a for-profit company called Public Consulting Group Inc. to identify private organizations that could help the state spend less on welfare while still receiving full federal funding, according to Utah’s contract with PCG.

When the state denies help to low-income Utahns, state caseworkers sometimes, though not always, suggest that they seek welfare from the church instead, according to interviews with more than three dozen former caseworkers and applicants.

“You would explain to them, ‘Have you talked to an LDS bishop?’” said Robert Martinez, an eligibility worker for the Department of Workforce Services from 2013 to 2019.

Martinez said he always gave applicants other nongovernmental options to consider, and there was no coercion to go the religious route. Still, he emphasized to them, the church has a lot more money to offer than the minimal aid dispensed by the state. (In fact, the church appears to have more money than what is by most accounts the largest philanthropic organization in the world, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.)

Liz Carver, director of workforce development at the Department of Workforce Services and the lead TANF official at the agency, acknowledged in multiple interviews that caseworkers might in some instances propose church welfare to customers, which is what the department calls citizens who apply for public assistance.

But, she said, welfare caseworkers not just in Utah but nationwide refer applicants to a range of community organizations, faith-based or not, all the time. It’s part of a larger conversation with these individuals about what brought them to ask for help that day, she said, and about which needs the government can assist with under the federal regulations and which it can’t.

Utah, Carver noted, is one of the most charitable states in the nation, characterized by a strong ethic of neighbors helping neighbors, which makes the agency’s public-private offerings stronger.

Regarding the state’s fiscal arrangement with the church, Carver said, “We’d have to ask the state Legislature for more money if we couldn’t count this partnership” toward state welfare.

“I mean, we could be counting millions of hours of [church members’] volunteer time, bishops helping their communities, all that stuff,” she continued, suggesting that the current amount of church assistance that Utah is claiming as the state’s is minimal and necessary.

Christina Davis, communication director for the department, added in an emailed statement that the fact that caseworkers may refer Utahns to the church and other private groups is a separate and unrelated issue from the state’s budgetary agreement with the church welfare program.

She also stressed that tens of thousands of low-income households in Utah receive other forms of help from the state, including food stamps and Medicaid.

Finally, Davis pointed out that the number of poor people who are provided direct assistance has been significantly scaled back not just in Utah but across the country.

The problem with Utah’s dependence on church aid to pick up that slack, civil rights advocates say, is that although the founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, once instructed his membership to clothe the naked and feed the hungry whether they are “in this church, or in any other, or in no church at all,” the thousands of individual bishops who today run point for LDS welfare services may have different views.

Most are continually generous with aid. But some might feel justified in politely denying assistance to poor people who aren’t Latter-day Saints — or to LGBTQ people — even in some cases turning away struggling church members who haven’t been attending services or paying 10% of their income to the church in tithes.

“There’s this term in the church called ‘bishop roulette,’” said David Smurthwaite, a former bishop in Salt Lake City, referring to the differing choices about welfare that get made by each bishop in congregations across the state.

Smurthwaite said that church leadership did equip him with a slate of questions to ask low-income people who came to his office asking for help. But, he said, bishops are “not professional welfare providers, not professional therapists, yet we get put in the hot seat for these kinds of experiences.”

Bishops are called to their lay role on a temporary basis, typically for around five years. Unlike most clergy in other faiths, they often have day jobs. And like with anyone else, their politics can infuse their religion.

There’s also much less accountability than there would be for a government program. Welfare decisions by bishops are subject mainly to the broad tenets of the church’s “General Handbook,” usually with counsel from other church leaders but without oversight from the public.

“If a state’s premier social safety net is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” said W. Paul Reeve, chair of Mormon studies at the University of Utah, “what does that mean if you’re not one?”

Separation of Church and State

The very first words of the First Amendment are not about freedom of speech or the right to protest, but rather a warning against government establishment of religion.

That is why the state of Utah’s welfare-provision system being intertwined with the LDS Church is “troubling,” said Douglas Laycock, a law professor at the University of Virginia and a leading expert on the separation of church and state. “I can’t think of anything at all analogous,” he said, adding that if someone sues, it would be a “novel” case.

Laycock noted, though, that if Utah’s granting and denying of welfare applications isn’t itself religious in nature, it may not matter legally that the state then tells some applicants deemed ineligible about a private source of aid — even one, like the church, that may judge them based on religion.

Nathan S. Chapman, a constitutional law professor at the University of Georgia, said a key question is whether Utah has “partnered” with the LDS Church to enough of an extent that the overall system for providing welfare in the state is “insufficiently religiously neutral” and thus denies vulnerable people “true private choice” as to whether to partake in religion so they can receive assistance.

But he also said the state could argue that it is not constitutionally obligated to provide welfare to citizens, and that there is a marketplace of private aid providers including not just the LDS Church but also others that are less publicized in Utah, like Catholic Community Services.

ProPublica interviewed more than two dozen low-income Salt Lake City-area residents about their experiences with Utah’s safety net. Almost all who weren’t active church members — and even many who were — felt that welfare in Utah is religiously prejudicial, at least in practical terms, because the state has left a vacuum of social services that’s filled by individual bishops and their potential biases.

Candice Simpkins, who grew up in the church, says she struggled to pay her bills and afford groceries after the birth of her daughter but knew from reading a state website that her income was slightly too high for her to qualify for public assistance. When she went to a bishop for help instead, she says, she was told that she wouldn’t be in her situation if she hadn’t had sex out of wedlock, and that she would have to start attending church services. (Feminist Mormons say that women especially are affected by the capriciousness of welfare in Utah. Bishops are all men, and some view both premarital sex and divorce, each of which can lead to precarious financial situations, as the fault of women, critics say.)

A close friend of Simpkins’, whom she called in tears after her interaction with the bishop, corroborated her description of what happened.

In another case, Jo Alexander, who is lesbian, says she was desperate for a hotel room during a period of homelessness. But she knew she couldn’t get public assistance from the state because she had received it around two decades ago as a young woman and therefore had exceeded her lifetime limit under another of the rules implemented under welfare reform. As a result, she went to a bishop.

Despite being raised as a member of the church, she was denied. She says it is known in the community that she is gay and she believes that was the reason for her rejection. (A friend confirmed her account, though there are no public records of these private conversations with bishops.)

And Miranda Twitchell, who is currently homeless, says the rules and procedures for obtaining state aid are so convoluted and seemingly endless that she had nowhere to turn except the church for immediate help when she needed food and a bed — and that’s when she decided to follow a piece of advice shared on the streets: “Get baptized, get help.”

Some low-income people in Salt Lake City say they have gotten baptized just to obtain welfare, even though they don’t believe in the ritual. Most who had done so were afraid to speak on the record for this story, believing the church would learn that their conversion stories were inauthentic and retaliate by not helping them in the future.

The LDS spokesperson defended the church’s approach to welfare in part by emphasizing that the church should not be confused with a government agency or considered a replacement for the government in the provision of public assistance. (Indeed, the LDS “General Handbook” clearly states that church members should turn to the government first for financial help, before going to their bishop.)

The church does look after its own membership, the spokesperson said, given that it is a religious institution. If a nonmember seeks help, there’s less of a preexisting relationship with that person, and a bishop may ask the individual to come to services to see firsthand what his or her needs are. There, relationships are established with church members, who then extend a hand of fellowship.

Finally, he said, one of the church’s larger goals is for people who are struggling financially to learn self-reliance and industriousness, not dependency. This may be one reason that some felt rejected when they asked for ongoing assistance.

Experts on charitable giving note that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its members arguably do more than any other religious community to help people in poverty. (In Utah, the church has given tens of millions to fight homelessness.)

Several active Latter-day Saints in the Salt Lake City area said that when faced with financial hardship, they may actually have a better safety net than anyone in any state, because they can count on the church for help with food, clothes, furniture, rent, utilities, car payments and repairs, tanks of gas, medical bills, moving expenses, job searches and general life problems.

Benjamin Sessions, executive director of Circles Salt Lake, an anti-poverty community organization, said that a struggling family he works with recently called him in the middle of the night while huddling in their car with nowhere to go. Sessions called up a local LDS leader he knows personally, who simply said, “What do you need? Get me a list.”

Help from the church is “dramatic and it’s quick,” Sessions said. “If you ask me to choose between calling up someone at the state versus someone at the church, I would call the church 10 out of 10 times.”

Others say it is a strength of this country that there are so many religious groups, including the Salvation Army, Catholic Charities, synagogues and mosques, that provide food and shelter to the poor.

“If someone has to listen to preaching to get free food, is it less than optimal? Sure,” the Cato Institute’s Michael D. Tanner told The Atlantic. “But it’s probably not the thing I’m most worried about.”

Yet most other faith-based organizations do not make religious rites such as worship or baptism a prerequisite of basic survival help, the way that some LDS bishops do, experts on religious charity say.

Even some lifelong church members in the Salt Lake City area told ProPublica that they were denied welfare by the church for religious reasons.

Amberlyn Robinson, who had been such a loyal churchgoer that she says she missed services only twice that she can remember during her entire childhood, fell deep into medical debt as a young woman after having a miscarriage that was nearly as expensive as it was traumatizing. She looked at her family’s finances and decided that the only way to pay the bills would be to be less consistent about tithing 10% of their limited income from her then-husband’s two jobs in retail, even though she worried God would smite her as a consequence.

Her bishop then denied her financial assistance, citing her failure to pay tithes as one reason — which left Robinson baffled as to how an inability to afford tithing could show anything but her need, she says, and made her so resentful that she ultimately left the faith.

Danilyn Levorsen, who was also born and raised in the church, struggles with rent and bills as the cost of living in and around Salt Lake City surges.

Her husband, who has severe disabilities that add to the family’s expenses, is a fan of the supernatural. He volunteers at a haunted house, Halloween is his Christmas, and he has intense tattoos.

When he asked a bishop for help, Levorsen says, the bishop responded by criticizing his alternative lifestyle and dark clothing.

“I hear on the news all the time that the church is shipping food to other countries,” she said, adding that she completely understands and supports those efforts, given the poverty in the world.

“But this is supposed to be their golden city, here,” she said. “And this is how they do us?”

It’s the State’s Responsibility

The onus to provide a safety net for America’s poorest families and children — and equal access to such services under the law irrespective of religion, gender, race or class — ultimately falls on the government, not a church that has a right to choose whom to serve.

Joel Briscoe, a former bishop in Salt Lake City and now a Democratic state legislator, said that as a bishop he always had people coming to him after they had tried and failed to get help from the state, especially food stamps. He could only do his best to make up for public assistance being “ludicrous, the amounts are so small,” he said.

Utah’s stinginess with aid stems in part from its focus on putting welfare applicants to work — no matter how much work a family is already putting into just getting by.

In Bellamy’s case, a state employee told her daughter Jaidyn that the family could get assistance only if she stopped staying at home to care for her mom and instead got a job, the family said. (She now works at a child care center. Bellamy’s older daughter, Imani, works overnight shifts as a home health care aide.)

Bellamy noted that the state has helped her with food stamps; she has also had many neighbors from the LDS church show her great kindness throughout her life, she said.

While denying so many families direct assistance, Utah was, as of a 2012 Government Accountability Office report, leading the nation in aid that its government was supposed to be providing the poor but was instead outsourcing to a third-party nongovernmental organization.

States do not have to report the extent to which they engage in this accounting maneuver, but a 2016 follow-up GAO report found that 15 others do it. By that time, Georgia was the outlier among several states that aggressively count as their own spending the charitable activities of groups such as United Way, the YMCA, food banks and domestic violence shelters.

Scott Dzurka, former president and CEO of the Michigan Association of United Ways, told the publication Bridge Michigan that his organization eventually decided to stop allowing its work to be counted by the state as welfare. “We looked long and hard at that,” he said, “and raised concerns that really our resources may in fact be working against what we were trying to do, which was to supplement state poverty efforts, not replace them.”

The LDS Church declined to comment on this issue.

For a brief period during Barack Obama’s presidency, the administration and Congress were both moving to prevent states from “gaming the system” by counting outside spending as their own. But Rep. Tom Price, who went on to briefly head the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under President Donald Trump, helped kill the legislation that would have ended the practice.

Because states are largely allowed to count welfare dollars how they want, Utah has also been able to spread this money around among its lawmakers’ favored projects, many of which are aimed at preventing low-income people from having sex out of wedlock rather than providing them with direct aid. (This is despite mounting evidence that cash assistance — money — alleviates poverty — a lack of money — much more effectively than less direct interventions like parenting classes.)

Welfare funding in Utah goes to the Utah Marriage Commission, among many other similar initiatives. These include a 4-H program called Teen Spheres of Influence that state budget documents say makes teens “3.4 times more likely to delay sexual intercourse through high school,” as well as a relationship program called “How to Avoid Falling for a Jerk or Jerkette.”

Davis, the Department of Workforce Services spokesperson, reiterated that all uses of TANF funds in Utah are consistent with federal regulations implemented under welfare reform, which explicitly pressed states to reduce pregnancies among the poor unless they are in married, two-parent households.

Still, Utah continues to evolve, diversifying, becoming less of an LDS state centered on traditional family life. One area south of Salt Lake City is now so jammed with tech companies that it has been rechristened the Silicon Slopes. Meanwhile, thousands of the region’s residents have become homeless over the past decade and are being pushed from one up-and-coming neighborhood to the next by the police and the health department.

Farther up the mountainside, past the lovely houses around the state Capitol, you’ll find their latest encampment set against a cliff above the blazing lights of the Marathon Oil refinery to the northwest. Most here say they were denied survival help by the state first and the church second, or vice versa. Many say their rejection by the church was due to their unkempt appearance, their refusal to attend church services they find hypocritical, or an assumption by bishops that they would spend financial assistance not on food, but on drugs.

Michelle Low grew up in the faith but says she had a dysfunctional home life and became addicted to drugs while still a child, and then became homeless. She is now trying not to ask the state for help because of the strict lifetime limit on receiving aid; she wants to be able to apply for it down the road if she needs to. (But she says she could use the aid to buy warm clothes and shoes and to pay her cousin rent so she’d have somewhere to live indoors.)

Instead, Low asked the church for assistance, despite the many moral and intellectual questions she has had since childhood about church doctrine. But a bishop she spoke with said he couldn’t help her unless she made the choice to live together with and marry her child’s father, she says.

The bishop said they could be married right there in his office.

To which Low said, “He isn’t the right guy for me, and also I don’t want to get married in an office.”

“See,” she says, “it’s always ‘We’ll help you if.’”

"Strong majorities of Americans support abortion rights and do not want to overturn Roe." (photo: Bryan Dozier/Rex/Shutterstock)

"Strong majorities of Americans support abortion rights and do not want to overturn Roe." (photo: Bryan Dozier/Rex/Shutterstock)

The demise of abortion rights is the outcome of years of Republican work to make it harder for people to vote and stack the bench with rightwing judges

On Wednesday, the supreme court heard arguments in a case challenging Mississippi’s ban on abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy, even for rape and incest survivors. Under the longstanding legal framework of Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, two of the supreme court cases that shape abortion rights in the US, states cannot outlaw abortion before the point of fetal viability, when the fetus can survive outside of the woman’s body (states can put restrictions on abortion before that point, so long as those restrictions don’t pose an “undue burden” on women seeking abortions). The Mississippi law violates that longstanding supreme court precedent.

Yet the court agreed to hear it anyway, which was the first bad sign – why hear a case that so clearly flies in the face of what the court has already ruled? Wednesday’s oral arguments only contributed to the sense of doom, as a majority of the justices seemed ready and willing to overturn Roe.

This didn’t happen by accident. The rightwing stranglehold on the courts has been a long-term project achieved by devious means. Republicans blocked Barack Obama from appointing dozens of judges to the federal bench, leaving those slots open for Donald Trump to fill. He stacked the courts with conservative reactionaries, many of whom were so unqualified that they failed to get the basic endorsement of the American Bar Association (ABA). Instead of appointing qualified candidates over rightwing stooges, the Trump administration simply cut the ABA out of the judicial vetting process.

The most egregious of these Republican blockades came when Obama tried to appoint Merrick Garland to the supreme court seat vacated by Antonin Scalia. The right cried foul: it was wrong to change the balance of the court, they said, and it was an election year and therefore unfair to allow Obama a supreme court appointment; voters should decide the next president to pick a supreme court judge.

A majority of voters wanted Hillary Clinton to have that role. But our undemocratic and archaic electoral college rules handed the victory to Donald Trump – the second time in less than two decades that the winner of the majority vote lost the White House.

Trump, who ran on a promise of appointing anti-abortion judges who would overturn Roe v Wade, set about doing just that. He appointed Neil Gorsuch to the seat that should have been Garland’s. Then he appointed Brett Kavanaugh, despite the judge facing credible accusations of sexual assault. Finally, and most insultingly, Trump and his Republican Senate allies rammed through the appointment of the explicitly anti-abortion Amy Coney Barrett to the seat vacated by the feminist icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg – in his last year of office, and despite the supposed rule about a president letting the voters decide before an election.

Trump voters – a minority of Americans in both 2016 and 2020 – are about to get what they want: an America in which women and girls are forced into pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood; an America in which women are second-class citizens, not entitled to control over the very bodies they live in, forced to risk their lives in the name of “pro-life” misogyny.

The rest of us are stuck dealing with these minority religious views imposed on us.

Strong majorities of Americans support abortion rights and do not want to overturn Roe. And in any case, the supreme court is supposed to be a bulwark against tyranny, an institution that defends and upholds constitutional rights, not one that punts those rights to the states.

This court is not that. And that’s because of the shameful rightwing devastation of American democracy. Three members of the conservative supreme court majority, after all, were appointed by a traitorous president who fomented an attempted coup against the United States, and who has continued to undermine the electoral process by claiming that the last election, which he lost fair and square, was stolen. His party has devolved into a cult of personality, so tied to one narcissistic tyrant that it didn’t even bother releasing a political platform in the last presidential election. And because the Republican party knows it will lose if it has to play on an even playing field, its members have been systemically undermining voting rights for years.

The demise of abortion rights in the US is the outcome of years of anti-democratic organizing to make it harder for people to vote, gerrymander districts, pull power from various elected offices when Democrats win them, and stack the bench with rightwing judges who will allow it all to happen.

It’s terrifying. And of course forcing women into subservience and traditional roles is part of this process – that’s been the strategy in authoritarian nations throughout history, and it’s a pattern we’re seeing play out now, as the same nations that are scaling back democratic norms and processes are also going after women’s rights.

That American women are facing a hostile supreme court and are looking at a future without abortion rights – and potentially without the constitutional right to contraception – isn’t a matter of law or “life”. It’s a sign of a democracy in decline.

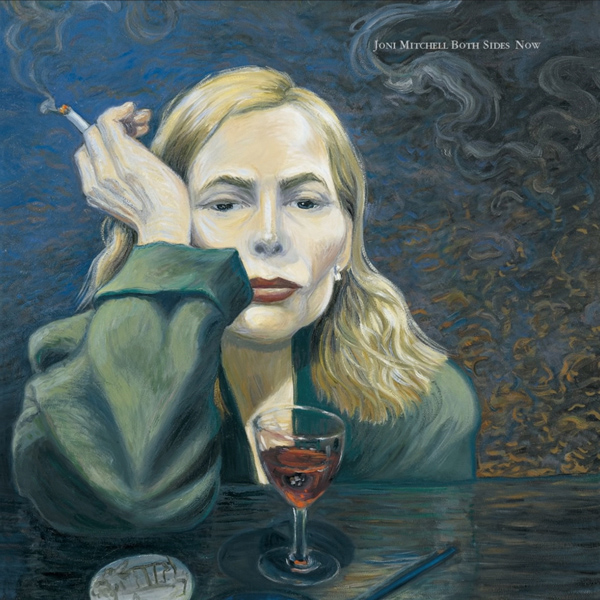

Sunday Song: Joni Mitchell | Both Sides Now

Joni Mitchell, YouTube

An updated Joni Mitchell portrait circa 2010 from her retrospective album, Both Sides Now. (photo: Self portrait, Joni Mitchell)Excerpt: "Rows and floes of angel hair and ice cream castles in the air."

An updated Joni Mitchell portrait circa 2010 from her retrospective album, Both Sides Now. (photo: Self portrait, Joni Mitchell)Excerpt: "Rows and floes of angel hair and ice cream castles in the air."

05 december 21

Lyrics Joni Mitchell, Both Sides Now.

Written by, Joni Mitchell.

From the albums Clouds, 1969 and Both Sides Now, 2000.

Rows and floes of angel hair

And ice cream castles in the air

And feather canyons everywhere

I've looked at clouds that way

But now they only block the sun

They rain and snow on everyone

So many things I would have done

But clouds got in my way

I've looked at clouds from both sides now

From up and down, and still somehow

It's cloud illusions I recall

I really don't know clouds at all

Moons and Junes and Ferris wheels

The dizzy dancing way you feel

As every fairy tale comes real

I've looked at love that way

But now it's just another show

You leave 'em laughing when you go

And if you care, don't let them know

Don't give yourself away

I've looked at love from both sides now

From give and take, and still somehow

It's love's illusions I recall

I really don't know love at all

Tears and fears and feeling proud

To say "I love you" right out loud

Dreams and schemes and circus crowds

I've looked at life that way

But now old friends are acting strange

They shake their heads, they say I've changed

Well something's lost, but something's gained

In living every day

I've looked at life from both sides now

From win and lose and still somehow

It's life's illusions I recall

I really don't know life at all

I've looked at life from both sides now

From up and down, and still somehow

It's life's illusions I recall

I really don't know life at all

A gray wolf in Oregon's northern Wallowa County in February 2017. Officials in Oregon are asking for help locating the person or persons responsible for poisoning an entire wolf pack in the eastern part of the state earlier this year. (photo: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife/AP)

A gray wolf in Oregon's northern Wallowa County in February 2017. Officials in Oregon are asking for help locating the person or persons responsible for poisoning an entire wolf pack in the eastern part of the state earlier this year. (photo: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife/AP)

Months after launching an investigation, Oregon State Police say they’ve “exhausted all leads.”

In a Dec. 2 release, the OSP said it is “seeking public assistance in locating the person or persons” behind the poisonings.

The situation began in early 2021.

In eastern Oregon, on Feb. 9, troopers with the OSP’s Fish and Wildlife Division went to investigate a collared gray wolf presumed dead by wildlife officials tracking the animal, according to the release. They presumed correctly.

Troopers found the wolf, along with two other males and two females — all five members of the Catherine Pack — laying lifeless in the snow. The pack died in Union County, southeast of Mount Harris, the release said.

Police combed the area for evidence and a dead magpie bird was also taken in as evidence, and shipped off to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Forensics lab in Ashland, to figure out what killed them.

One month later, troopers were back in the vicinity. Another wolf’s collar was “emitting a mortality signal in the same general location” the release said.

This wolf, a member of the Keating Pack, died alone except for a skunk and a magpie found “very close to the scene.”

As the snow melted in the following days, more evidence was revealed: evidence of poisoning.

By April, the lab results were in. All the animals died from poison, according to the release.

Two more gray wolves would be killed in Union County. A male, in April near Elgin. And then in July, a young female, close to La Grande — the same area the Catherine Pack was killed.

Different kinds of poison were used in those two most recent killings, officials said.

However, “based upon the type of poison and locations, it was determined the death of the young female wolf may be related to the earlier six poisonings.”

At the end of 2020, there were an estimated 173 wolves in Oregon and 22 wolf packs, according to the state Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Anyone with information regarding the poisonings is encouraged to call the OSP hotline at 1-800-452-7888.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611