Remembering RobbieA Memorial Day reflectionFriends, Robbie was the kindest person I ever knew. I met him in our dormitory the day we entered college in 1964. He saw me struggling to carry my big luggage crates up the two flights of stairs to my dorm room and, without saying a word, grabbed one and hauled it to the second floor. “Thank you!” I stammered when we reached the landing. “Don’t mention it,” he said with a broad smile, and then offered his hand. “I’m Robbie.” “Bob,” I said, shaking his hand. “Good to meet you, Bob!” He must have noticed I was exhausted by the effort, and lonely to boot. “It’s close to dinner time,” he said. “Wanna walk over to the dining hall?” “Sure!” That was the start of our friendship. Robbie was intuitively kind. He combined a remarkable warmheartedness with a degree of compassion I had never known before. And it wasn’t only toward me. Every young man in our dorm, and many in our class, came to admire and depend on Robbie. Robbie went missing in action in Vietnam on October 12, 1972. His body has never been recovered. I think of Robbie on Memorial Day, as I do of others who died while serving in the United States Armed Forces. I was strongly opposed to the Vietnam War. I demonstrated and marched against it. I was too short to be drafted, but I detested it — the cruel absurdity of that war, the lies with which it was sold to the American people, the utter waste of it. In the end, more than 58,000 Americans and millions of Vietnamese lost their lives in it. Many more were grievously wounded. But when I think of Robbie, I also remember his sense of duty. Duty was inseparable from his kindness. Whatever the situation, Robbie was eager to help. What do we owe one another as members of the same society? Our current president apparently believes we owe each other nothing. To him, everything is a transaction — a deal in which each of us is in it for as much money and power as we can get. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump denigrated Senator John McCain, whose plane was shot down over Hanoi in 1967. McCain became a prisoner of war. The North Vietnamese offered him early release because McCain’s father was commander of all U.S. forces in Vietnam at the time. But the young McCain refused the offer in order to uphold the Code of Conduct, which stipulated that prisoners of war should be released in the order they were captured. As a result, he remained in North Vietnam for nearly five additional years, during which time he was put into solitary confinement and tortured. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said during the 2016 presidential campaign. Then he altered his comment: “He’s a war hero because he was captured. I like people that weren’t captured, OK?” Trump avoided serving in Vietnam by claiming he had a bone spur in his heel. As Michael Cohen, Trump’s “fixer,” told members of the House Oversight Committee in 2019:

Finally now, in 2025, Trump is going to Vietnam. He and his family business are planning a $1.5 billion golf complex outside Hanoi and a Trump skyscraper in Ho Chi Minh City — the Trump family’s first projects in Vietnam. According to The New York Times, the two projects are part of a global moneymaking enterprise that no family of a sitting American president has ever attempted on this scale. Robbie was never in it for himself. He did what he did because he felt he had an obligation to do it, for the nation he loved. It’s why I remember and honor Robbie on Memorial Day. |

Search This Blog

Monday, May 26, 2025

Remembering Robbie

Sunday, May 25, 2025

This Weekend in Politics, Bulletin 138

This Weekend in Politics, Bulletin 138

… Trump gave a bizarre, rambling, slurring, often incoherent speech at the West Point graduation. In addition to the huge military parade scheduled in DC for his birthday next month, Trump continued to politicize an institution that is supposed to be apolitical by wearing one of his red MAGA campaign hats during the speech. … Here were some of the things he said to the young graduates:

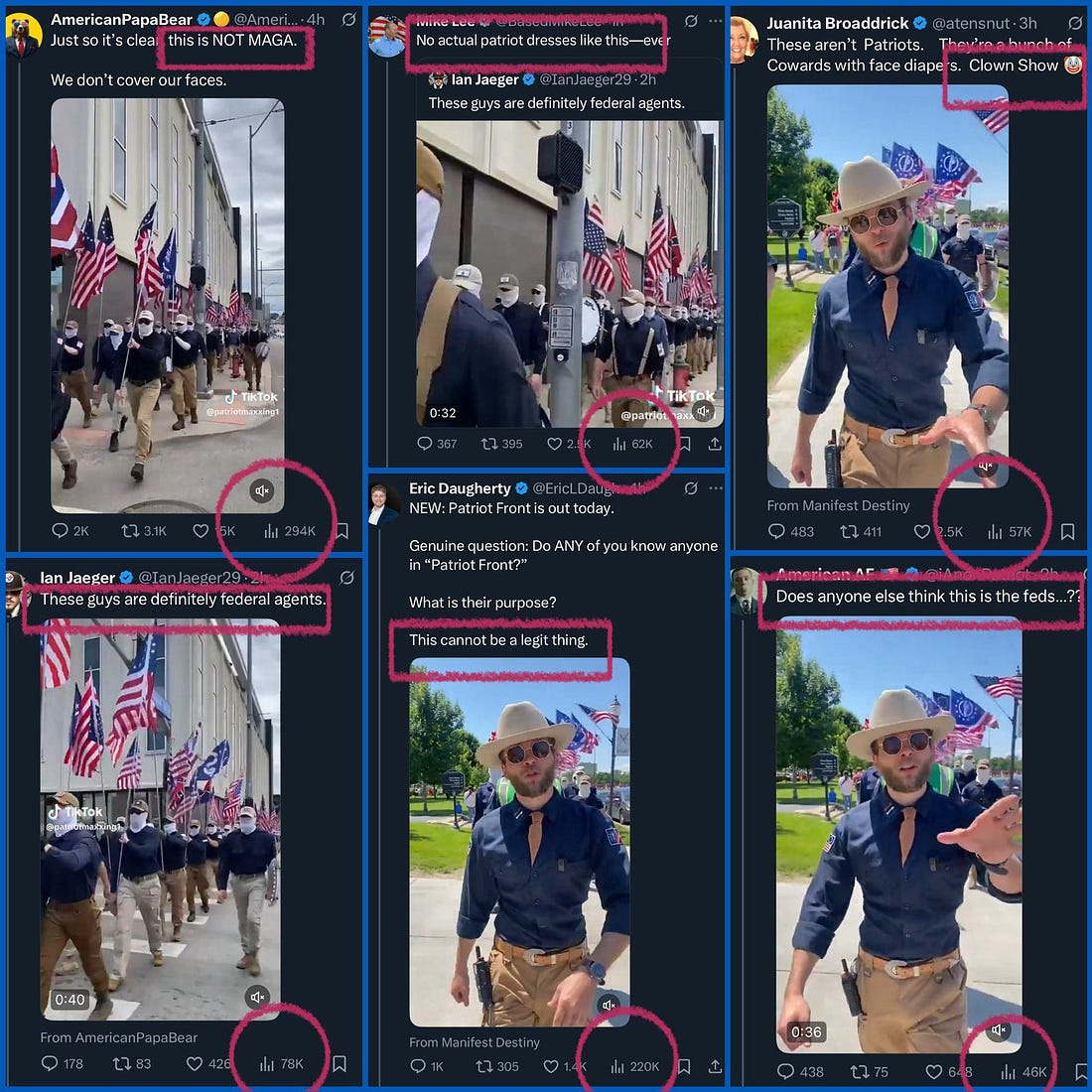

… Trump then left without shaking the hands of any of the graduates. Joe Biden and Barack Obama shook the hands of every single one when they spoke there. But Trump headed to Bedminster for golf, where he later posted a photo of his playing partner getting attacked in the genitals by the swan guarding Ivana’s grave near the 16th hole. … Gen. Ben Hodges (Ret.), former Commanding General of US Army Europe, on Trump wearing a campaign hat: “What a rotten example for these new Officers. How are any of the Academies or ROTC programs going to teach Cadets about Duty, Honor and Country with him and Secretary Hegseth as their Leaders?” … Tom Nichols, retired Prof at US Naval War College: “Trump has been actively trying to politicize the US military since his first campaign. Those cadets have been taught that this is inappropriate, but now the Commander-in-Chief is telling them that rules are for other people.” … Richard Stengel, former Undersecretary of State: “1. He disrespects West Point by wearing his MAGA hat. The cadets all remove their hats out of a tradition of respect. 2. He disrespects them by talking about trophy wives and yachts. 3. He disrespects them by saying he ‘rebuilt the military’ in 4 months. The military he inherited is larger than the next top 10 nations combined. 4. He disrespects the military by erasing the memory of soldiers of color who fought for freedom even when they did not have it.” … This was the headline from the The Independent (UK) about the speech: … And here is the NYT headline sanewashing the speech for Trump, very similar to many other legacy media headlines about it: … Rep. Jasmine Crockett (D-TX) on MSNBC: “It is time for Republicans to start calling him out and start questioning his mental acuity, and whether or not he is equipped to serve mentally. We know when it comes down to his criminality, he is not qualified to serve, but this is just absolutely deplorable.” … Crockett also said when Democrats take the House after the 2026 midterms, she wants to run for Oversight Chair: “I am hoping an praying that my colleagues see that I can provide what we need as a team moving forward, hoping we can instill some confidence in the America people knowing they have a real fighter who won’t back down - and I get death threats every day. But I will fight fearlessly and ferociously for the American people.” … She was asked what she would do as Chair: “We will investigate. We will look at whether this president has violated the emoluments clause. We will make sure we look into all these business deals they have going on. Think about how much money they’re raking in, whether we’re talking about the next golf resort they’re setting up in Qatar or this crypto scam. There is no shortage of things for us to dig into.” … Former Kentucky swimmer Riley Gaines, who has parlayed a 5th place finish at the NCAAs into a career as a MAGA social media influencer, was on Sean Hannity’s show complaining about Kermit the Frog’s commencement speech to Univ of MD grads: “Imagine being a 22 year old student who is graduating with a degree in aerospace engineering, and a fraud from the Muppets is on stage telling you to stay connected with your people. I mean, you can’t even make this stuff up. Instead of honoring entrepreneurs, or veterans or innovators they picked Kermit the Frog!” … “We have students who are drowning in debt, struggling to find jobs, and universities are handing the mic to puppets. Not puppets like many Democratic elected leaders, a real puppet. It’s all theater. I see this as the same institutions who have been pushing political agendas and cancel culture now want to use a puppet to inspire students. It’s unserious, it’s out of touch, and frankly it’s insulting.” … Legendary Muppets creator Jim Henson came up with the Kermit puppet character when he was an 18 year old student at Maryland. Henson’s wife also graduated from Maryland. That is why Kermit gave the speech, which the graduates loved. Kermit did not mention trophy wives in his speech, otherwise maybe Gaines would have liked it better. Reminder that we make the entire Weekend Bulletins available to free subscribers, with about the first 30% of the daily ones during the week available for free. Everyone is also able to post comments to the weekend ones. If you missed Friday’s Bulletin, you can find it here. Meidas+ is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. … Fortune interviewed Nicholas Pinto, who secured a spot at Trump’s crypto dinner after buying $360,000 of his tokens. He was asked about the food: “Trash. Walmart steak. Everyone at my table was saying the food was some of the worst food that they ever had. I was hoping for either Big Macs or pizza. That would have been better than the food that we were served. The only good part was the bread and the butter.” … Pinto text to Fortune from the event: “Most of the people here are sketchy, I’m not gonna lie.” … What did Pinto think about Trump’s speech? “Pretty much, like, bullshit.” … Speaker Mike Johnson was asked on CNN why he wasn’t saying anything about Trump’s crypto dinner scam: “Look, I don't know anything about the dinner. I was a little busy this past week, so I'm not going to comment on something I haven't even heard about.” … Apparently, the Speaker of the House is the only one in DC who hasn’t heard about it. He must just watch Fox News. … Retired AF Gen. Blaine Holt told Newsmax that Trump’s Palace in the Sky jet from Qatar is going to cost taxpayers plenty: "It's going to cost a lot of money to take the skin off the aircraft, to reinforce it where it needs to be, find any surveillance items that may be lingering around the airplane. All the electronics, communications gear, everything else involved that goes into that. Probably going to run a few dollars.” … NYT published a lengthy story detailing how Vietnam broke some of their own laws to rush approval of a Trump golf resort and a Trump Tower Ho Chi Minh City because they believe that’s what they have to do to get new US tariffs lifted: “To fast-track the Trump development, Vietnam has ignored its own laws, granting concessions more generous than what even the most connected locals receive.” … Le Van Troung was coerced into signing a consent form to allow a burial site with 5 generations of his ancestors to be plowed over to make room for the golf course, as well as rich farmland that has sustained local families for centuries: “There’s nothing I can do. Trump says it’s separate — the presidency and his business. But he has the power to do whatever he wants.” … “Vietnamese officials, in a letter obtained by NYT, explicitly stated that the project required special support from the top ranks of the Vietnamese govt because it was ‘receiving special attention from the Trump admin and Trump personally.’ Vietnamese officials have waved the development along in a moment of high-stakes diplomacy. They face intense pressure to strike a trade deal that would head off Trump’s threat of steep tariffs, which would hit about 30% of Vietnam’s exports.” … “The process usually takes 2-4 years. But records show that initial planning documents were filed only 3 months before Wednesday’s event, which was held on newly leveled land under an archway announcing ‘THE GROUNDBREAKING CEREMONY OF TRUMP INTERNATIONAL, HUNG YEN.’ Vietnam’s foreign ministry did not respond to questions about the legality of the project.” … WH response to the story: “All of the president’s trade discussions are totally unrelated to the Trump Organization.” … Sen. Rand Paul was on Fox today complaining about the House budget bill: "Somebody has to stand up and yell, 'the Emperor has no clothes!' Everybody is falling in lockstep on this - 'Pass the big beautiful bill. Don't question anything.' Well, conservatives do need to stand up and have their voices heard. If we don't stand up on it, I really fear the direction the country is going." … Paul: "If you increase the debt ceiling $4-5 trillion, that means they're planning on $2T this year and more than $2T next year. That's just not conservative. So I've told them if they strip out the debt ceiling, I'll consider even with the imperfections voting for the rest of the bill." … They aren’t going to do that. Because the only way to do that is to take out Trump’s massive tax cuts or dramatically cut Social Security and Medicaid even more, and take out the $150B in new defense spending. Not happening. … Elon Musk’s X has been a technical disaster over the weekend, with the site going completely down for over an hour with a number of other glitches and problems continuing unabated. Users across the ideological spectrum have been complaining bitterly about it, including Musk’s biggest fan in the Senate, X-addict Mike Lee: “Something is terribly wrong with X.” … Bloomberg: “Elon Musk said he needs to be ‘super focused’ on his companies, pointing to issues at X as evidence of a need for ‘major’ improvement at the social network. Users reported problems with X Friday and Saturday, according to DownDetector. A post from the company’s engineering team also said it was facing issues from a data center outage.” … Musk posted this about it: “I’m back to spending 24/7 at work and sleeping in conference/server/factory rooms. I must be super focused on X/xAI and Tesla (plus Starship launch next week), as we have critical technologies rolling out. As evidenced by the X uptime issues this week, major operational improvements need to be made.” … This was the guy Trump brought in to make govt more efficient. … WaPo: “Politics has been central to Musk’s identity over much of the past year, but his latest obsession has faded into disenchantment over the personal costs and difficulties in producing results, said 2 people familiar with his thinking. Musk has also become deeply concerned for the personal safety of himself and his family. [WHAT FAMILY?] He also did not anticipate the level of backlash against him personally or against his companies, including incidents of violence at Tesla facilities. Along with that push is a pull for renewed involvement in his 2 main businesses, Tesla and SpaceX.” … The white nationalist group Patriot Front marched in KC this weekend. When this well-documented group did this during the Biden Admin, people like Elon Musk, Sen. Mike Lee, Joe Rogan and many others claimed it was a false flag operation by the FBI to try and discredit right-wingers. Rogan told Musk on his show that we would not see them again once Trump took office, and Musk agreed: “I bet when Kash gets in they disband.” … But Kash Patel and Dan Bongino have been running the FBI for months, and PF is still marching. Is MAGA now going to finally admit these are white nationalists? Nope. … Former FBI Director James Comey was asked about right-wingers who are upset with Kash Patel for yet not arresting anyone connected to Jeffrey Epstein and Deep State political enemies of Trump: "He's found himself now in a reality-based world where statements have to be under oath in front of judges and there are severe consequences for lying — not the case with a podcast." PARDON MY INTRUSION! HARVARD ACCEPTS THE BEST & THE BRIGHTEST! LIVING WITHIN PROXIMITY OF THE BEST TEACHING FACILITIES IN THE NATION, WE SOMETIMES TAKE THEM FOR GRANTED....EXCEPT WHEN LIFE THREATENING CONDITIONS EXIST! A FRIEND WAS IN THE VA HOSPITAL OVER THANKSGIVING WEEK WITH AN UNRESOLVED PROBLEM & A 'CONSULT' WAS REQUESTED...ONE WOULD THINK THE 'CONSULT' WOULD BE AFTER THE HOLIDAY..NO! I WAS THERE! A GAGGLE OF DOCTORS ARRIVED ON THANKSGIVING DAY, EACH WITH A DIFFERENT LAB COAT IDENTIFYING THEIR AFFILIATION...THEY OFFERED A QUICK, SIMPLE RESOLUTION, EASILY EXPLAINED! NOT ONE OF THOSE DOCTORS WAS WHITE! AMERICANS ARE LAZY & PROVE IT REPEATEDLY! A FRIEND'S DAD LIVING IN MAINE HAD A LIFE THREATENING CONDITION THEY WERE UNABLE TO DIAGNOSE OR TREAT. HE WAS SENT TO MASS GENERAL WHERE A DOCTOR WEARING A BURKA IMMEDIATELY DIAGNOSED HIS CONDITION & TREATED HIM. … Trump posted: “Why isn’t Harvard saying that almost 31% of their students are from FOREIGN LANDS, and yet those countries, some not at all friendly to the US, pay NOTHING toward their student’s education, nor do they ever intend to. NOT TRUE! Nobody told us that! We want to know who those foreign students are, a reasonable request since we give Harvard BILLIONS OF DOLLARS, but Harvard isn’t exactly forthcoming. We want those names and countries!” … JD Vance made it clear with an X post that the Trump admin is using govt power to coerce a right-wing takeover of major universities: “The voting patterns of university professors are so one-sided that they look like the election results of N. Korea. And on top of all of this, many universities explicitly engage in racial discrimination (mostly against whites and asians) that violates the civil rights laws of this country. Our universities could see the policies of the Trump admin as a necessary corrective to these problems, change their policies, and work with the admin to reform. Or, they could yell ‘fascism’ at basic democratic accountability and drift further into irrelevance.” … Netflix is out with a new documentary about former NFL QB Brett Favre, which included his sexting scandal where he made unwanted advances to a NY Jets employee while he was married, and his welfare fraud scam in Mississippi. Favre complained that Netflix is only targeting him because he is “an outspoken Trump supporter.” … Another MAGA victim. … NBC: “Mexican singer Julión Álvarez announced the postponement of his Sat concert at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, TX, saying his work visa had been revoked. Álvarez, show promoter CMN and management company Copar Music said the show had been canceled due to unforeseen circumstances and that Álvarez was ‘unable to enter the US in time for the event.’ Alvarez said they were formally notified on May 23 that the work visas for his band were canceled ahead of the May 24 concert. 50,000 tickets were sold for the show.” … Alvarez said he will refund the money and cancel the show if the visa issue can’t be straightened out quickly so he can do the show on another date. … NYT: “Under intense scrutiny about his mental health and his ability to function in his job, Sen. John Fetterman has been in damage control mode, attending hearings and votes that he had been routinely skipping over the past year. Fetterman does not enjoy participating in these hearings that he has sat through in recent weeks as he seeks to prove that he is capable of performing the job he was elected to do until 2028. In fact, at a critical moment for the country, he appears to have little interest in the day-to-day work of serving in the Senate.” … “In an interview, Fetterman said he felt he had been unfairly shamed into fulfilling senatorial duties, such as participating in committee work and casting procedural votes on the floor, dismissing them as a ‘performative’ waste of time. Instead, he said he was ‘showing up because people in the media have weaponized’ his absenteeism on Capitol Hill to portray him as mentally unfit, when in fact it is a product of a decision to spend more time at home and less on the mundane tasks of being a senator.” … “Fetterman has also foregone events in his state. He has avoided hosting town halls with his constituents because he does not want to get heckled by protesters. ‘I just want to be in a room full of love,’ he has told people. At the same time, Fetterman has shed staff. And he has grown more isolated from his Democratic colleagues. Despite attempts from his friends in Congress to draw him out, Fetterman still does not attend the weekly Democratic caucus lunch in the Capitol.” … Kierstyn Zolfo, with the progressive grass roots group Indivisible, who lives in Bucks County: “The regrettable fact is that John Fetterman is not doing the job he was elected to perform. It makes me very sad, because I have supported him for so long, and I worked so hard to get him elected. But he’s just not getting the job done.” … El Pais: “Both the Miami Herald and FL public radio WLRN dedicated editorials to the country’s first Latino Sec of State. ‘Rubio used Venezuelans in his hometown for political gain. Now, he’s betrayed them,’ read the article in the Herald headline. ‘Venezuelans and other migrant groups see leaders like Marco Rubio no longer have their backs — because today, boosting deportations matters more than bolstering democracy,’ wrote WLRN Americas editor Tim Padgett.” … Groups have filled billboards in recent days targeting Rubio and other Republicans in FL who have supported Trump’s immigration policies. One billboard: “Little Marco sold out all Venezuelans. He told Trump to end TPS. He’s a traitor to all those fleeing dictatorships.” … The Trump admin has adopted a strategy to try and bypass the EU to negotiate directly with member countries who they perceive as being more friendly to them like Hungary, Italy, and Poland. It isn’t going to work, but as with all things the Trump strategy is divide and conquer. … Trump campaign advisor Jason Miller was on GB News: “You have to separate out Brussels from the rest of the European countries - from the member countries. President Trump has had his greatest success with bilateral trade agreements. The EU is controlled by these bureaucrats in Brussels. They’re putting up a resistance fight. The president is sending a very clear message that if they don’t come to the table there is going to be ramifications.” … When asked about which bilateral trade agreements Trump has reached that were so successful, Miller cited the BS deal with UK and concepts of deals with some Asian countries that they are still working on. … Economist Justin Wolfers: “Maybe men are just too emotional to run trade policy.” … President Zelensky: “Today, rescuers have been working in more than 30 Ukrainian cities and villages following Russia’s massive strike. Nearly 300 attack drones were launched by Russians overnight. In addition, almost 70 missiles of various types were fired, including ballistic ones. Each such terrorist Russian strike is a sufficient reason for new sanctions against Russia. Russia is dragging out this war and continues to kill every day. The world may go on a weekend break, but the war continues, regardless of weekends and weekdays. This cannot be ignored.” … “The silence of America, silence of others around the world, only encourages Putin. Without truly strong pressure on the Russian leadership, this brutality cannot be stopped. Sanctions will certainly help. Determination matters now – the determination of the US, of Europe, and all those around the world who seek peace. The world knows all the weaknesses of the Russian economy. The war can be stopped, but only through the necessary force of pressure on Russia. Putin must be forced to think not about launching missiles, but about ending the war.” … Oliver Carroll, foreign correspondent for The Economist: “Another heavy night of Russian air strikes on Ukraine. At least 8 dead and 15 injured. Three kids were killed in their beds in Zhytomyr region. The capital was targeted by ballistic missiles and drones again. I still remember the ‘VLADIMIR, STOP!’ phase of Trumpian diplomacy.” … UK journalist Theo Mullis in Kviv: “It amazes me how much the psychology of this echos that of a domestic violence case. I was a police officer for 7 years. I seen a lot of that stuff, and the most dangerous moment is when the survivor tries to break away. That’s what we see from Russia - the impotence, the violent rage, the spitefulness. The sense that if I can’t have you no one will. These attacks on Kviv over the last couple of nights are spiteful outbursts. Exactly the same as when a domestic violence abuser gets drunk and attacks their partner - the psychology is the same.” … Independent journalist ‘Jay in Kviv’: “Russia is merely the broken down, alcoholic wife beater that just cant let go. Sadly, the US now plays the part of the corrupt cop that looks the other way for a small bribe.” … Trump has threatened additional sanctions by Truth Social post on 4 separate occasions over the past 4 months if Russia didn’t stop the bombing, starting with his first day in office. Putin has ignored him, and Trump has done nothing. He played golf yesterday and today with zero statement or response to this weekend’s bombings. … Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA): “The US cannot fail to respond as Putin escalates his barbaric assault on innocent Ukrainians. Congress must act immediately and decisively. Peace through strength begins with action. We need full, crippling sanctions targeting Putin, his regime, and those bankrolling this campaign of terror until the Russian war machine collapses in on itself." … Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov rejected Pope Leo XIV's offer to mediate peace talks with Ukraine at the Vatican: "It would be a little inelegant for Orthodox countries to discuss issues related to eliminating the root causes of the war on Catholic ground. It would not be very comfortable for the Vatican itself to host delegations from Orthodox countries in these circumstances." … As usual, everything that comes out of the Kremlin is a lie. Just like our government now. … Rudy Giuliani surfaced on Steve Bannon’s podcast, where he wanted to talk about Jake Tapper’s Biden book. Rudy said he was lobbying Trump and AG Pam Bondi to appoint him as special counsel to prosecute Joe Biden and his family. … Kayleigh McEnany seemed to like the idea of a special counsel, but maybe not Rudy leading the charge. … Joe Exotic, the subject of the Netflix documentary Tiger King, continues to look for new and creative ways to lobby the Trump admin to give him a pardon. His husband was recently deported to Mexico, and he promises Trump that if he lets him out of prison he will go to Mexico and earn $5 million to buy US citizenship for him from Howard Lutnick: “President Claudia Sheinbaum, call President Trump and tell him to release me so I can go to Mexico and work to buy Jorge a Trump Gold Card.” Meidas+ is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. |

Evening Roundup, May 28...plus a special thank you to our Contrarian family

Evening Roundup, May 28...plus a special thank you to our Contrarian family Featuring Jen Rubin, Katherine Stewart, Brian O'Neill, Jenni...

-

01 January 22 Live on the homepage now! Reader Supported News FOCUS: Robert Reich | The Road Ahead Robert Reich, Robert Reich's Su...

-

29 January 22 When You Back RSN You Are Backing Proven Fighters Pressuring the networks, not allowing the real story to go unnoticed, ma...

-

06 October 21 Live on the homepage now! Reader Supported News WHAT’S THE COST OF A CORPORATE INFORMATION MONOPOLY? — Everything? In effect...