17 December 21

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

FIGHTING FOR FUNDING IS FIGHTING FOR JUSTICE — We fight for justice all day long, every day. What our organization is experiencing is economic injustice. What we use the money for is what we do every day. And many of you ignore that vital funding need. This organization fights for justice. Help.

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News

Sure, I'll make a donation!

The Members of Congress Aiding the Coup on January 6

Katie Benner, Catie Edmondson, Luke Broadwater and Alan Feuer, The New York Times

Excerpt: "Two days after Christmas last year, Richard P. Donoghue, a top Justice Department official in the waning days of the Trump administration, saw an unknown number appear on his phone."

Two days after Christmas last year, Richard P. Donoghue, a top Justice Department official in the waning days of the Trump administration, saw an unknown number appear on his phone.

Donoghue had spent weeks fielding calls, emails and in-person requests from President Donald Trump and his allies, all of whom asked the Justice Department to declare, falsely, that the election was corrupt. The lame-duck president had surrounded himself with a crew of unscrupulous lawyers, conspiracy theorists, even the chief executive of MyPillow — and they were stoking his election lies.

Trump had been handing out Donoghue’s cellphone number so that people could pass on rumors of election fraud. Who could be calling him now?

It turned out to be a member of Congress: Rep. Scott Perry, R-Pa., who began pressing the president’s case. Perry said he had compiled a dossier of voter fraud allegations that the department needed to vet. Jeffrey Clark, a Justice Department lawyer who had found favor with Trump, could “do something” about the president’s claims, Perry said, even if others in the department would not.

The message was delivered by an obscure lawmaker who was doing Trump’s bidding. Justice Department officials viewed it as outrageous political pressure from a White House that had become consumed by conspiracy theories.

It was also one example of how a half-dozen right-wing members of Congress became key foot soldiers in Trump’s effort to overturn the election, according to dozens of interviews and a review of hundreds of pages of congressional testimony about the attack on the Capitol on Jan. 6.

The lawmakers — all of them members of the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus — worked closely with the White House chief of staff, Mark Meadows, whose central role in Trump’s efforts to overturn a democratic election is coming into focus as the congressional investigation into Jan. 6 gains traction.

There was Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio, the pugnacious former wrestler who bolstered his national profile by defending Trump on cable television; Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona, whose political ascent was padded by a $10 million sweepstakes win; and Rep. Paul Gosar, an Arizona dentist who trafficked in conspiracy theories and spoke at a white nationalist rally.

They were joined by Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas, who was known for fiery speeches delivered to an empty House chamber and unsuccessfully sued Vice President Mike Pence over his refusal to interfere in the election certification; and Rep. Mo Brooks of Alabama, a lawyer who rode the Tea Party wave to Congress and was later sued by a Democratic congressman for inciting the Jan. 6 riot.

Perry, a former Army helicopter pilot who is close to Jordan and Meadows, acted as a de facto sergeant. He coordinated many of the efforts to keep Trump in office, including a plan to replace the acting attorney general with a more compliant official. His colleagues call him General Perry.

Meadows, a former congressman from North Carolina who co-founded the Freedom Caucus in 2015, knew the six lawmakers well. His role as Trump’s right-hand man helped to remarkably empower the group in the president’s final, chaotic weeks in office.

Congressional Republicans have fought the Jan. 6 committee’s investigation at every turn, but it is increasingly clear that Trump relied on the lawmakers to help his attempts to retain power. When Justice Department officials said they could not find evidence of widespread fraud, Trump was unconcerned: “Just say that the election was corrupt + leave the rest to me and the R. Congressmen,” he said, according to Donoghue’s notes of the call.

November

On Nov. 9, two days after The Associated Press called the race for Biden, crisis meetings were underway at Trump campaign headquarters in Arlington, Virginia.

Perry and Jordan huddled with senior White House officials, including Meadows; Stephen Miller, a top Trump adviser; Bill Stepien, the campaign manager; and Kayleigh McEnany, the White House press secretary.

According to two people familiar with the meetings, which have not been previously reported, the group settled on a strategy that would become a blueprint for Trump’s supporters in Congress: Hammer home the idea that the election was tainted, announce legal actions being taken by the campaign, and bolster the case with allegations of fraud.

Gosar embraced the fraud claims so closely that his chief of staff, Tom Van Flein, rushed to an airplane hangar parking lot in Phoenix after a conspiracy theory began circulating that a suspicious jet carrying ballots from South Korea was about to land, perhaps in a bid to steal the election from Trump, according to court documents filed by one of the participants. The claim turned out to be baseless.

December

On Dec. 1, 2020, Attorney General William Barr said publicly what he knew to be true: The Justice Department had found no evidence of widespread election fraud. Biden was the lawful winner.

The attorney general’s declaration seemed only to energize the six lawmakers. Gohmert suggested that the FBI in Washington could not be trusted to investigate election fraud. Biggs said that Trump’s allies needed “the imprimatur, quite frankly of the DOJ,” to win their lawsuits claiming fraud.

They turned their attention to Jan. 6, when Pence was to officially certify Biden’s victory. Jordan, asked if the president should concede, replied, “No way.”

On Dec. 21, Trump met with members of the Freedom Caucus to discuss their plans. Jordan, Gosar, Biggs, Brooks and Meadows were there.

“This sedition will be stopped,” Gosar wrote on Twitter.

January

On Jan. 5, Jordan was still pushing. That day, he forwarded Meadows a text message he had received from a lawyer and former Pentagon inspector general outlining a legal strategy to overturn the election.

“On January 6, 2021, Vice President Mike Pence, as President of the Senate, should call out all the electoral votes that he believes are unconstitutional as no electoral votes at all — in accordance with guidance from founding father Alexander Hamilton and judicial precedence,” the text read.

On Jan. 6, Washington was overcast and breezy as thousands of people gathered at the Ellipse to hear Trump and his allies spread a lie that has become a rallying cry in the months since: that the election was stolen.

Brooks, wearing body armor, took the stage in the morning, saying he was speaking at the behest of the White House. The crowd began to swell.

“Today is the day American patriots start taking down names and kicking ass,” Brooks said. “Are you willing to do what it takes to fight for America?”

Trump approached the dais soon after. “We will never give up,” Trump said. “We will never concede.”

Roaring their approval, many in the crowd began the walk down Pennsylvania Avenue toward the Capitol, where the certification proceeding was underway. Amped up by the speakers at the rally, the crowd taunted the officers who guarded the Capitol and pushed toward the building’s staircases and entry points, eventually breaching security along the perimeter just after 1 p.m.

By this point, the six lawmakers were inside the Capitol, ready to protest the certification. Gosar was speaking at 2:16 p.m. when security forces entered the chamber because rioters were in the building.

As the melee erupted, Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, yelled to his colleagues who were planning to challenge the election: “This is what you’ve gotten, guys.”

When Jordan tried to help Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., move to safety, she smacked his hand away, according to a congressional aide briefed on the exchange.

“Get away from me,” she told him. “You fucking did this."

A spokesman for Jordan disputed parts of the account, saying that Cheney did not curse at the congressman or slap him.

The back-and-forth was reported earlier by Washington Post reporters Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker in their book “I Alone Can Fix It.”

The Aftermath

Perry was recently elected leader of the Freedom Caucus, elevating him to an influential leadership post as Republicans could regain control of the House in 2022. The stolen election claim is now a litmus test for the party, with Trump and his allies working to oust those who refuse to back it.

All six lawmakers are poised to be key supporters should Trump maintain his political clout before the midterm and general elections. Brooks is running for Senate in Alabama, and Gohmert is running for Texas attorney general.Some, like Jordan, are in line to become committee chairs if Republicans take back the House.

In many ways, they have tried to rewrite history. Several of the men have argued that the Jan. 6 attack was akin to a tourist visit to the Capitol. Gosar cast the attackers as “peaceful patriots across the country." A Pew research poll found that nearly two-thirds of Republicans said their party should not accept elected officials who criticize Trump.

Still, the House select committee investigating the Capitol attack appears to be picking up steam, voting this week to recommend that Meadows be charged with criminal contempt of Congress.

Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss. and the chairman of the committee, said the panel would follow the facts wherever they led, including to members of Congress.

“Nobody,” he said, “is off-limits.”

READ MORE

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-WV, rushes past reporters after attending a lengthy Democratic Caucus meeting as the Senate continues to grapple with end-of-year tasks at the Capitol in Washington, Thursday, Dec. 16, 2021. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-WV, rushes past reporters after attending a lengthy Democratic Caucus meeting as the Senate continues to grapple with end-of-year tasks at the Capitol in Washington, Thursday, Dec. 16, 2021. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Power of One: Manchin Is Singularly Halting Biden's Agenda

Lisa Mascaro and Farnoush Amiri, Associated Press

Excerpt: "Sen. Joe Manchin settled in at President Joe Biden's family home in Delaware on a Sunday morning in the fall as the Democrats worked furiously to gain his support on their far-reaching domestic package."

Sen. Joe Manchin settled in at President Joe Biden’s family home in Delaware on a Sunday morning in the fall as the Democrats worked furiously to gain his support on their far-reaching domestic package.

The two-hour-long session was the kind of special treatment being showered on the West Virginia senator — the president at one point even showing Manchin around his Wilmington home.

But months later, despite Democrats slashing Biden’s big bill in half and meeting the senator’s other demands, Manchin is no closer to voting yes.

In an extraordinary display of political power in the evenly split 50-50 Senate, a single senator is about to seriously set back an entire presidential agenda.

“We’re frustrated and disappointed,” said Sen. Dick Durbin, the majority whip. “Very frustrated,” said another Democratic senator granted anonymity to frankly discuss the situation Thursday.

Biden said in a statement Thursday night that he still believed “we will bridge our differences and advance the Build Back Better plan, even in the face of fierce Republican opposition.”

But with his domestic agenda stalled out in Congress, senators are coming to terms with the reality that passage of the president’s signature “Build Back Better Act,” as well as Democrats’ high-priority voting rights package, would most likely have to be delayed to next year.

Failing to deliver on Biden’s roughly $2 trillion social and environmental bill would be a stunning end to the president’s first year in office.

Manchin’s actions throw Democrats into turmoil at time when families are struggling against the prolonged COVID-19 crisis and Biden’s party needs to convince voters heading toward the 2022 election that their unified party control of Washington can keep its campaign promises.

The White House has insisted Manchin is dealing with the administration in “good faith,” according to deputy White House press secretary Andrew Bates.

Manchin, though, has emerged as an uneven negotiator — bending norms and straining relationships because he says one thing one day and another the next, adjusting his positions, demands and rationale along the way.

Democratic senators have grown weary of their colleague, whose vote they cannot live without — but whose regular chats with Republican leader Mitch McConnell leave them concerned he could switch parties and take away their slim hold on power.

“Mr. Manchin and the Republicans and anybody else who thinks that struggling working families who are having a hard time raising their kids today should not be able to continue to get the help that they have, then that’s their view and they’ve got to come forward to the American people and say, ‘Hey, we don’t think you need help,’” said Sen. Bernie Sanders, the independent from Vermont. “Let them tell the American people that.”

The senator appears to both relish and despise all the attention he has commanded over many months at Biden’s home in Delaware with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, in regular visits with Biden at the White House and in his daily strolls through the Capitol, where he banters amiably, swats back questions or simply clams up -- which becomes a statement of its own, leaving Manchin-whisperers to wonder what his silence means.

“I got nothing — n-o-t-h-i-n-g,” he drawled to the reporters waiting outside the Democrats’ closed door lunchroom Thursday as it became clear there would be no Christmas deal.

But between his endless hallway utterances is a consistent through-line in Manchin’s months-long commentary about what he wants in — and out — of Biden’s big package before giving his vote. The short version is he’s not quite there yet.

Like the chief executive he once was — as governor of a state that surveys show ranked 47th in the nation for health care outcomes and 45th in education — Manchin ultimately decides where the attention goes next. And he has been effective.

So far, Manchin has gotten much of what he wanted: Biden halved what had been a $3.5 trillion proposal to $1.75 trillion, once Manchin gave his nod to that figure.

Manchin insisted the corporate tax rate Biden proposed raising to 28% would not inch past 25% — in fact, it ended up not being raised at all, thanks to opposition from another hold-out Democrat, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona.

The coal-state senator insisted the new renewable energy incentives to fight climate change would not come at the expense of fossil fuels. The White House scrapped plans for a nationwide renewable energy standard that environmental advocates viewed as the most significant tool for curbing climate change.

And Manchin’s demands for “no additional handouts” have limited some of the proposed social programs, and appear destined to tank plans to launch the nation’s first-ever paid family and medical leave program for workers whose employers don’t provide the paid time off to temporarily care for loved ones.

But what Manchin actually does want is much more unclear. And it all raises the question of whether Manchin even wants Congress to pass any “Build Back Better Act” at all.

For progressives, the stalemate Manchin engineered was exactly what lawmakers have feared after Congress signed off on a companion $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill rather than force the two bills to move together to Biden’s desk.

Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan called it “tragic.” Rep. Cori Bush of Missouri said, “We must not undermine our power as a government nor the power of the people by placing the fate of Build Back Better at the feet of one Senator: Joe Manchin.”

Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who helmed Biden’s latest compromise version to House passage, downplayed the Manchin negotiations as part of the process. “This is legislating,” she said.

But this week, Manchin introduced a new demand, suggesting the enhanced child tax cut, which has been one of the most significant federal policies Democrats enacted this year -- lifting some 40% of the nation’s children from poverty — must run for the full 10 years of a traditional federal budget window rather than just one, as the House approved in a cost-cutting compromise.

It’s a non-starter — the price of a decade-long child tax cut would consume the bulk of Biden’s bill.

All this while Democrats also need support from Manchin, and Sinema, for Senate rules changes so they can overcome the 60-vote threshold needed to overcome a Republican filibuster to pass voting rights.

Manchin met with McConnell on Thursday, as they often do.

“As you know, he likes to talk,” the Republican leader told reporters. “It would not surprise you to know that I’ve suggested for years it would be a great idea, representing a deep red state like West Virginia, for him to come over to our side.”

McConnell added, “I don’t think that’s gonna happen.”

READ MORE

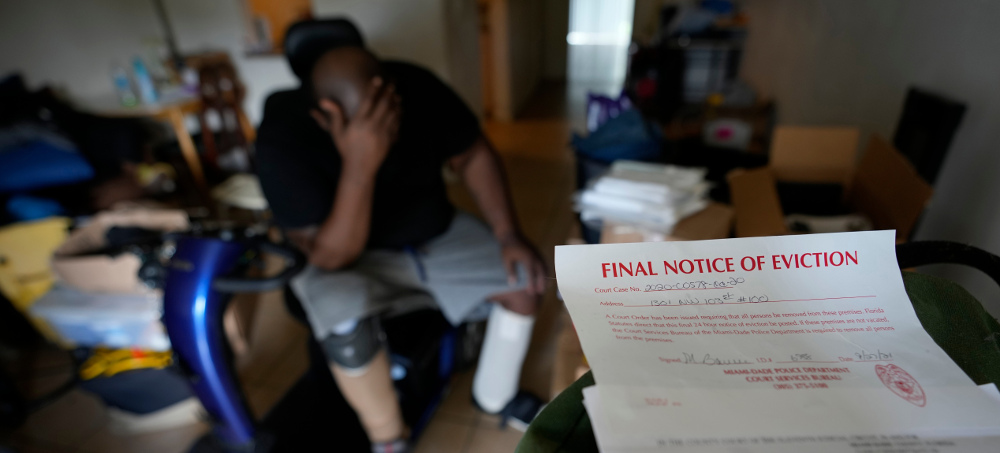

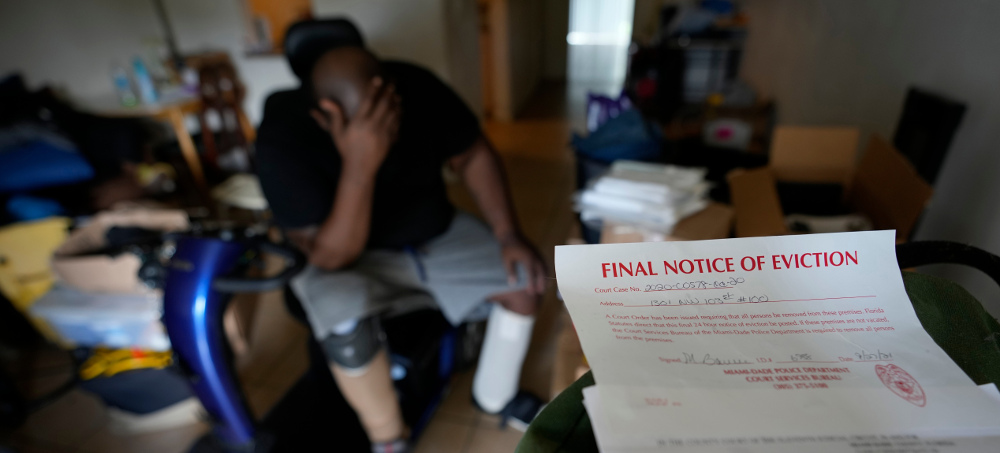

As the pandemic's moratoriums come to an end, the man some call 'Lock-'em-out Lennie' is once again knocking on doors in Arizona. (photo: Adriana Zehbrauskas/The Washington Post)

As the pandemic's moratoriums come to an end, the man some call 'Lock-'em-out Lennie' is once again knocking on doors in Arizona. (photo: Adriana Zehbrauskas/The Washington Post)

The Return of the 10-Minute Eviction

Eli Saslow, The Washington Post

Saslow writes: "The city's last eviction moratorium of the pandemic had expired and the rent forgiveness program was running out of money, so Lennie McCloskey changed into his bulletproof vest and headed out to work. He climbed into his truck and counted through his daily stack of eviction orders."

As the pandemic’s moratoriums come to an end, the man some call ‘Lock-’em-out Lennie’ is once again knocking on doors in Arizona

The city’s last eviction moratorium of the pandemic had expired and the rent forgiveness program was running out of money, so Lennie McCloskey changed into his bulletproof vest and headed out to work. He climbed into his truck and counted through his daily stack of eviction orders. “Fifteen, sixteen — jeez Louise,” he said as he stacked them on the passenger seat. He strapped an extra magazine of ammunition to his belt and picked up his radio to call dispatch.

“Constable 33, heading out,” he said. “Looks like a busy day.”

“Okay,” the dispatcher said. “Guess it’s back to business as usual.”

Nobody in Phoenix was better or more practiced at the business of eviction than Lennie, who had personally removed more than 20,000 Arizonans from their homes during the past two decades as the area’s longest-serving elected constable. “Lock-’em-out Lennie,” colleagues occasionally called him, because the 65-year-old former judo champion was capable of coaxing tenants out of their homes with subtle intimidation or with grandfatherly kindness. He arrived at each apartment with treats to pacify dogs and stickers to give children. The tenants he ushered outside each day into their first moments of homelessness were often inconsolable, or defiant, or suicidal, or mentally ill, or violent and aggressive, but Lennie was calm. “You have to take your own emotions out of it,” he’d told colleagues during one national training. “It’s our job to carry out the court order.”

Now he looked at the first address in his pile and navigated by memory toward a low-income apartment complex on the outskirts of Phoenix. There were 25 other constables across Maricopa County who spent their days carrying out evictions, but few areas were as busy as Lennie’s district, a six-by-six-mile grid of discount shopping centers and faded stucco apartments that catered to working-class families. The average rent had gone up by 40 percent since the beginning of the pandemic, and now some of the apartment complexes had wait lists and new names like Canyon Oasis, Chateau Gardens, Desert Lakes and Paradise Palms. Lennie pulled up to the leasing office of a 300-unit building and carried his stack of eviction orders inside to the property manager.

“Looks like you’re getting rid of four here today?” he said.

“Should be five,” the property manager told him. “Moratorium’s over, but nobody wants to pay.”

“Well, some might want to,” Lennie said.

She shrugged. “They didn't, and I got a list of new people ready to write checks.”

“Understood,” Lennie said, and she pointed him toward the first apartment on his list, a basement unit next to an empty swimming pool. He put on his heavy-duty gloves, felt for his holstered firearm and knocked on the door. “Hello! Maricopa County constable,” he said. Inside he could hear whispering, a dog barking, and then silence.

He leaned against the door and listened to the sound of footsteps shuffling across the floor. For much of the past 20 months, Lennie had been working to keep people in their homes during the pandemic, brokering deals between landlords and tenants and connecting both sides with federal assistance programs during the moratorium, but lately he was back to doing several dozen evictions each week. It wasn’t yet the post-pandemic tsunami of evictions that some had predicted but rather a return to normal — except normal seemed different to Lennie now, more relentless and unpredictable. Landlords acted increasingly impatient after months of falling behind on their collections. Tenants were more resistant to leaving their homes after months of government assistance. And Lennie could feel his own behavior shifting, too, in ways he was still trying to understand. “It’s not like I’ve gone soft, but maybe a little bit more lenient,” he said. “More compassionate or understanding.”

He waited at the entryway for a few more seconds, took out his baton, and started banging on the door.

“Hello!” he shouted. “Maricopa County peace officer! Open up now!”

***

Lennie had done more than 300 evictions since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s federal moratorium expired in early August, and during that time he’d given up on predicting who might come to the door. In the past several months, he’d evicted a 93-year-old from a retirement facility, a group of drug addicts living in an apartment cluttered with bowls of counterfeit cash, a man claiming to be a “sovereign citizen” above the law who barricaded himself inside the apartment, a laid-off restaurant worker, a schizophrenic, a hoarder, a recent Somali refugee, a man with a pet reindeer, a woman who tried hiding inside her dresser cabinet, and six families living in a two-bedroom apartment subdivided by drapes and shower curtains.

But no matter who he found waiting inside, Lennie’s job remained the same: to search the home, force everyone out and change the locks — all within a government-recommended time of about 10 minutes.

Now the apartment door swung open in front of him, and this time what Lennie saw was a shirtless, middle-aged man holding a half-eaten bowl of cereal. The dark apartment behind him was cluttered with cardboard boxes, broken furniture and open piles of trash. “Can I help you?” the man asked.

“Good morning,” Lennie said. “I’m here because I have a court order that says by law I need to evict you out of here.”

The man glanced at Lennie’s badge and then down at his gun. “Uh-huh. Okay,” he said. He took a few bites of cereal while Lennie waited.

“Sorry, but we don’t have much time,” Lennie said.

“Oh, you mean I’m getting evicted today?” the man said. “Right now?”

Lennie nodded. “You can make an appointment with the landlord to come get your things later, but we only have a few minutes before we change the locks. Grab any essentials you can’t live without.”

The tenant stepped into the living room, and Lennie followed him inside to search the apartment. The ceiling was covered with graffiti. The plaster walls were pockmarked with large dents and holes. A woman was hiding behind the bathroom door, and she came out as Lennie walked by. “Hello, ma’am,” he said, and she scowled back at him.

“Just the essentials,” Lennie repeated. “Medications. Pets. Walking shoes. Photo albums. Car keys. A change of clothes.”

The tenants began stuffing T-shirts into a backpack. Lennie checked his watch as the building’s maintenance worker started to change the locks. “We about ready?” Lennie asked the tenants a few moments later, and when nobody answered he tried again. “Time to wrap up,” he said, and eventually the tenants walked out of the apartment with the backpack, a Chihuahua, a small TV and a box fan.

“Good luck,” Lennie said as he closed the door behind them. He locked the deadbolt. He shook the door handle to test the new lock. He looked down at his watch: nine minutes.

“Okay. One down,” he told the maintenance worker. “Who’s next?”

It was a teenage couple, seated side by side on a mattress in their living room and playing video games. “Sorry. Only the essentials,” Lennie said, and six minutes later they walked out with nothing but cellphone chargers and their PlayStation.

Next was an empty apartment, where Lennie walked inside and found a child’s bedroom still intact: a plastic basketball hoop, a dozen withered balloons, a wall poster of Kobe Bryant, a fish tank with three goldfish circling against the glass. “All clear,” Lennie told the maintenance worker. “Lock it up.”

Next it was a mother and her two children, ages 6 and 13, gathered in front of their dryer. “I need to finish this load,” the mother told Lennie, and he nodded and reached into his pocket for a referral card to a local shelter. “Maybe they can help,” Lennie said.

“I tried that,” she said. “I tried everything.”

“Do you have anywhere to go?” he asked.

“Does it matter?”

“The law says I have to carry out this order,” Lennie said. “But yeah. It matters to me.”

She grabbed the load of laundry and pointed her kids to a Toyota in the parking lot. “We’ll be in the car for a few days,” she said.

Eight minutes. Eleven minutes. Four minutes. Six minutes. “They’re over fast but sometimes you keep thinking about them,” Lennie said as he climbed back into his truck and headed toward his ninth eviction of the morning, at a newer apartment complex. He pulled into the parking lot and ate a power bar. He sat in the car for an extra moment with his mask off, taking deep breaths, but then the property manager came up to his window and waved.

“Here for the eviction?” she asked, and Lennie nodded, handed her the court order, and pointed to the apartment number.

“Tell me they moved out already,” he said. “Tell me it’s an easy one.”

***

He followed the property manager through the courtyard to a two-bedroom apartment with an entry mat that read: “Welcome! Friends Gather Here.” On the porch Lennie noticed a small collection of toy trucks and a child’s fairy garden built from straw dolls and succulent plants. “Oh no,” he said, and he shut his eyes for a moment and then knocked, until a man wearing a collared shirt and a carrying briefcase answered the door.

“Hi,” Lennie said. “Ricardo Hernandez?”

“Yes, sir. Can I help you? I’m just leaving for work.”

“I’m sorry to say I’ve got a court order for eviction. I’m here to ask you to leave.”

A little girl came up from behind Ricardo and grabbed onto his leg. Lennie waved to her. She looked up at his bulletproof vest and then hid behind her father and started to cry. “Oh no. It’s okay, sweetheart,” Lennie said. He reached into his pocket and felt beyond the handcuff keys and the flashlight and the absorbent medical gauze for his collection of sheriff-badge stickers, and then he held one out toward her.

“Come on, really?” Ricardo said, glaring first at the sticker and then at Lennie.

Lennie shrugged. “Kids love stickers,” he said, and the girl took it and put it on her dress. Lennie gave her a thumbs-up and turned back to Ricardo.

“I know this is hard,” he said. “We’ll give you a few minutes to get your personal items.”

“We’ve got three kids,” Ricardo said. “We’ve been here three years and never caused any trouble. Our rent was getting paid, but I’ve been late because of this whole pandemic.”

“And I believe you,” Lennie said. “But, unfortunately, that doesn’t stop the eviction.”

“I have the money,” Ricardo said.

Lennie looked down at the eviction paperwork. “Says here the judgment is for $2,300.”

“I’m telling you, I have the money,” Ricardo said, and Lennie nodded and looked at him for a long moment.

For his entire career he’d been listening to tenants offer excuses and beg for more time, and usually Lennie’s answer had been the same. Rent had to be paid on schedule. The eviction order had already been filed. The law was the law. His job was to execute the order. “Sorry, Charlie,” he had sometimes told tenants, but now he looked beyond Ricardo into the home and saw a baby rolling around in a pack-and-play in the living room and a framed photograph on the wall of a family of five sitting on a tree branch in matching flannel shirts. The locksmith stood next to Lennie on the porch, twirling a drill in his hands. Lennie stepped back from the doorway and then smiled.

“Okay,” he said. “If the property manager lets you pay up now, I’m good with that. That would be good for everybody.”

“Thanks,” Ricardo said, and he peeled his daughter off his leg and walked toward the rental office as he told Lennie about everything that had happened to his family during the pandemic. He’d lost his job as a general manager at a restaurant and scrambled to find work at Costco, but then the new baby arrived, and then the property company had sent a letter saying their rent was going up by $200 per month because of “increased demand.” Ricardo had tried to make up the gap by starting a commercial cleaning company, but some of his clients had been slow to pay as his October rent went into default and his November bill came due.

“Believe it or not, I’ve been there,” Lennie said, and he told Ricardo about how his side business as an electrician had suffered during the economic collapse in 2008, just as he and his wife were preparing to adopt a son. He’d fallen so far behind on his mortgage that one afternoon he’d returned home from a day of doing evictions to find a foreclosure notice taped to his own front door, and then he’d barely scrambled together enough money in savings and loans to keep his home.

“We’re all a few bad breaks away,” Lennie told the property manager as they sat down in her office. “If Ricardo here is able to pay up in full, can he stay?”

The manager looked at Ricardo and sighed. “We’ve been trying to contact you since October. Emails. Knocking on your door. Letters. Offers of payment plans. We’ve been more than fair.”

“I’m always working,” Ricardo said.

“Okay, so there’s been some bad communication,” Lennie said. “But, if he’s still able to take care of it?”

“At this point he’d have to pay late fees and also all of December,” the property manager said. She started to punch numbers into a calculator while Ricardo took out his phone and sent messages to clients who owed him money. Lennie smoothed the creases out of his pants and glanced up at the clock. Eighteen minutes already. Twenty. “All right, here’s the total,” the property manager finally said, and she wrote it down on a sticky note and held it up so Ricardo could see: $6,130.78. “It needs to be a cashier’s check,” she said.

“Whoa. Come on. It’s, it’s just —” Ricardo said, trying to gather himself. “It’s just very challenging to get that much money right now.”

“How about 24 hours?” Lennie suggested, looking at the property manager. “I don’t need to be the bad guy here. If you want to give him a day, I can be flexible. I’ll come back tomorrow.”

“It’ll be the same situation,” she said.

“Sure. Could be,” Lennie said. “But who knows? Maybe you get more with honey than with vinegar.”

She drummed a pen against her desk and looked at Ricardo for a moment. “Fine. Twenty-four hours,” she said, and Ricardo clapped his hands together and went outside to make phone calls. Lennie gathered up his eviction papers and stood to leave.

“Thanks for working with him,” he said.

“Don’t get your hopes up,” she said. “I don’t know how you do this every day.”

***

He was used to people assuming his job was unbearable, but the truth was that despite its heartaches, dangers and starting salary of $48,000, Lennie mostly enjoyed being a constable. It had introduced him to hidden corners of the city and to all kinds of people, including a community of local constables who had become some of his closest friends. They got together each week for breakfast, so one morning Lennie pulled into a diner to join a group of his colleagues before they all started their shifts.

The constables at the table were elected to office by their own local districts, which made for a diverse group. Most of them were Republican, like Lennie, but some were Democrats. One was a landlord who had lost rental income during the pandemic; another had a background in social work and tenants’ rights. Many were former police officers who carried handguns; a few preferred to dress like civilians and carry only clipboards, for their paperwork. But lately all of them came to commiserate about a job that had become more fraught and unpredictable during the past few months.

“So, I walk into this apartment the other day, and the guy’s loading an AK-47,” one constable said. “I couldn’t understand half of what he was saying. Just gibberish.”

“I swear the pandemic’s made everyone mental,” another constable said. “They think their world is ending.”

“In some ways it is,” Lennie said. “If we’re there, it’s probably the worst day of their lives.”

“You have to help them see a tomorrow.”

“You have to get them out of the house.”

It was a familiar debate among the constables — empathy vs. enforcement — and more and more Lennie found himself stuck somewhere in between. Some constables thought tenants had taken advantage of the moratorium, and it was true that Lennie had gone to apartments during the pandemic where tenants acted as if they were above the law, damaging property and spending their rental assistance on flat-screen TVs and new cars while their landlords suffered. But, much more often, he had encountered renters who were newly jobless, working from home, grieving, terrified of the virus, or already sick as they exhausted their savings to pay what little they could.

“A lot of people are still playing catch-up,” he said. “They have good intentions.”

“It’s about treating them with kindness and respect,” another constable said.

“But, as a taxpayer, there’s a part of me that says: Why are we wasting my money to help deadbeats?” a retired constable said. “Maybe it’s their own fault they can’t pay.”

“They don’t have two brain cells to rub together,” another said. “Some of these people can’t be helped.”

“But maybe some can,” Lennie said, and a few minutes later he paid the bill and left for his shift.

***

A mother and her autistic child in a ransacked one-bedroom. A vacant apartment with 49 empty bottles of Corona scattered across the floor. A woman who offered to pay with fake money and then lunged at Lennie, until he tackled and restrained her. “You’re a tool of capitalistic corruption!” she shouted at him as he pinned her to the floor. “You dogging the American people. You’re killing us. You’re a monster. How do you people sleep?” But within 10 minutes Lennie had gotten her calmed down and out the front door, and then he navigated back toward Ricardo’s apartment complex to see whether he had paid.

“Did we get a happy ending?” he asked the property manager.

“Depends,” she said, and then she explained that she’d received no payment and no more information from Ricardo, so she’d already rented out his unit, increasing the price from $1,700 to $2,200, and a new tenant had snapped it up within 15 minutes. “Demand right now is off the chain,” she said. “We need him out. We need to proceed.” Lennie sighed, nodded and followed the locksmith back down the gravel pathways to Ricardo’s porch.

“They’re ready to go ahead with the order,” he said once Ricardo came to the door.

“I tried to call them,” Ricardo said, and his wife joined him in the doorway. Her eyes were red, and the baby was fussing in her arms. “We’re good for the money,” she said. “We actually got it, but then somebody hacked into the bank account, so now it’s frozen, and they changed the account number, and I’m waiting for the new one, and—”

Ricardo cut in: “Six-thousand is a lot. We just need a little more time.”

Lennie winced and shook his head. “Management already rented it out, but we’ll give you 10 minutes to grab some essentials,” he said.

Ricardo crossed his arms, stared at Lennie for a moment, and then nodded. “Okay. Ten minutes,” he said, and then he began hurrying through the house to find all the essentials necessary for a 7-year-old, a 4-year-old, a 1-year-old and a dog.

He went to the bedroom to pack diapers, wipes, shoes and toiletries. His wife went to the refrigerator for milk, snacks and baby food. “What if the whole damn kitchen is essential?” she asked as she threw open cabinets and slammed them shut. The 4-year-old came into the kitchen carrying her leftover Halloween candy, two stuffed animals and her roller skates. “What about my TV?” she asked Ricardo, and he leaned down to squeeze her shoulder and shook his head. “It’s too big. We’ll get it later,” he said, and she started to cry. Ricardo offered her his cellphone to distract her. Lennie held out another sticker, and the girl took it and looked up at him. “Don’t watch my TV,” she told him. “Don’t change the channel. Don’t sleep in my bed.”

Five minutes. Six. “We need more time,” Ricardo said, cursing to himself, but to Lennie the final 10 minutes inside someone else’s home usually felt interminable. There was little for him to do and nothing helpful he could say, so he stood in a corner and tried to make polite conversation as he encouraged things along.

“I like this lamp,” he told Ricardo.

“Huh?” Ricardo said, as he came out of the bathroom carrying five toothbrushes and then followed Lennie’s gaze to a floor lamp in the living room. “Oh, yeah. Thanks.”

“Where’d you get it?”

“Costco,” Ricardo said as he packed the toothbrushes into a travel case.

“No kidding?” Lennie said. “I should go get one of those.”

“I’ll sell it to you,” Ricardo said. “How about $6,200?”

Nine minutes. Ten. Ricardo grabbed car seats, dog food and his gun safe and carried them outside to the porch. Twelve minutes. Fifteen. “I’m trying not to rush you, but unfortunately we don’t have a whole lot more time,” Lennie said.

“Shoes!” Ricardo reminded his wife. “Pajamas! Pack-and-play!” She started to fold up the crib and then saw a pile of crackers left behind on the floor. She grabbed a broom and started to sweep it up.

“That’s okay,” Lennie said. “You don’t need to do that.”

“I can’t help myself,” she said, and she started to cry. Lennie stood against the wall, watching her, trying to think of something to say. “You ever hear about those robot vacuums?” he asked, finally. “They just go around and keep the dust out and everything.”

“Uh-huh,” she said. She finished sweeping, folded the crib and tossed it onto the porch with the rest of the essentials. Ricardo carried the children outside, and Lennie locked the door and walked with them toward their truck.

“This is just wrong,” Ricardo told him as he started the engine. “It’s ridiculous. It’s cruel. It’s barbaric.”

“I’m sorry,” Lennie said, but the moratorium was over and that meant it was also routine. He watched them drive away, double-checked the locks, and then continued to the next address on his list.

READ MORE

Claudette Colvin arrives outside juvenile court to file paperwork to have her juvenile record expunged, Tuesday, Oct. 26, 2021, in Montgomery, Alabama. A judge on Thursday, Dec. 16, has approved a request to wipe clean the court record of Colvin, who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a segregated Alabama bus in 1955. (photo: Vasha Hunt/AP)

Claudette Colvin arrives outside juvenile court to file paperwork to have her juvenile record expunged, Tuesday, Oct. 26, 2021, in Montgomery, Alabama. A judge on Thursday, Dec. 16, has approved a request to wipe clean the court record of Colvin, who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a segregated Alabama bus in 1955. (photo: Vasha Hunt/AP)

She Refused to Move Bus Seats Months Before Rosa Parks. At 82, Her Arrest Is Expunged

Associated Press

Excerpt: "A judge has approved a request to wipe clean the court record of a Black woman who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a segregated Alabama bus in 1955, months before Rosa Parks gained international fame for doing the same."

A judge has approved a request to wipe clean the court record of a Black woman who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a segregated Alabama bus in 1955, months before Rosa Parks gained international fame for doing the same.

A judge granted the request by Claudette Colvin, now 82, in a brief court order made public Thursday by a family representative.

Parks, a 42-year-old seamstress and activist with the NAACP, gained worldwide notice after refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man on Dec. 1, 1955. Her treatment led to the yearlong Montgomery Bus Boycott, which propelled the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. into the national limelight and often is considered the start of the modern civil rights movement.

A 15-year-old high school student at the time, Colvin refused to shift seats on a segregated Montgomery bus even before Parks.

A bus driver called police on March 2, 1955, to complain that two Black girls were sitting near two white girls in violation of segregation laws. One of the Black girls moved toward the rear when asked, a police report said, but Colvin refused and was arrested.

The case was sent to juvenile court because of Colvin's age, and records show a judge found her delinquent and placed her on probation "as a ward of the state pending good behavior." Colvin never got official word that she had completed probation through the ensuing decades, and relatives said they assumed police would arrest her for any reason they could.

At the time she asked a court in October to expunge her record, Colvin said she did not want to be considered a "juvenile delinquent" anymore.

"I am an old woman now. Having my records expunged will mean something to my grandchildren and great grandchildren. And it will mean something for other Black children," Colvin said at the time in a sworn statement.

Now that Juvenile Court Judge Calvin L. Williams has approved the request, Colvin said in a statement that she wants "us to move forward and be better."

"When I think about why I'm seeking to have my name cleared by the state, it is because I believe if that happened it would show the generation growing up now that progress is possible, and things do get better. It will inspire them to make the world better," she said.

Colvin never had any other arrests or legal scrapes, and she became a named plaintiff in the landmark lawsuit that outlawed racial segregation on Montgomery's buses.

READ MORE

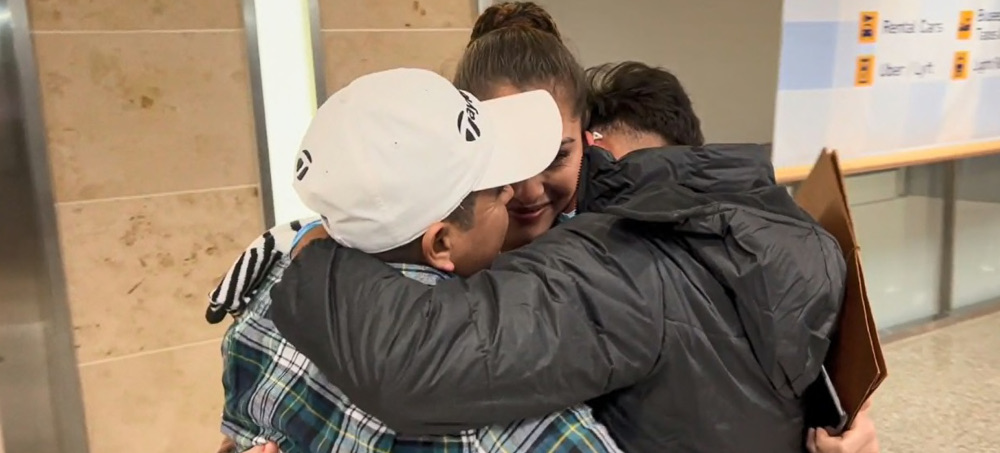

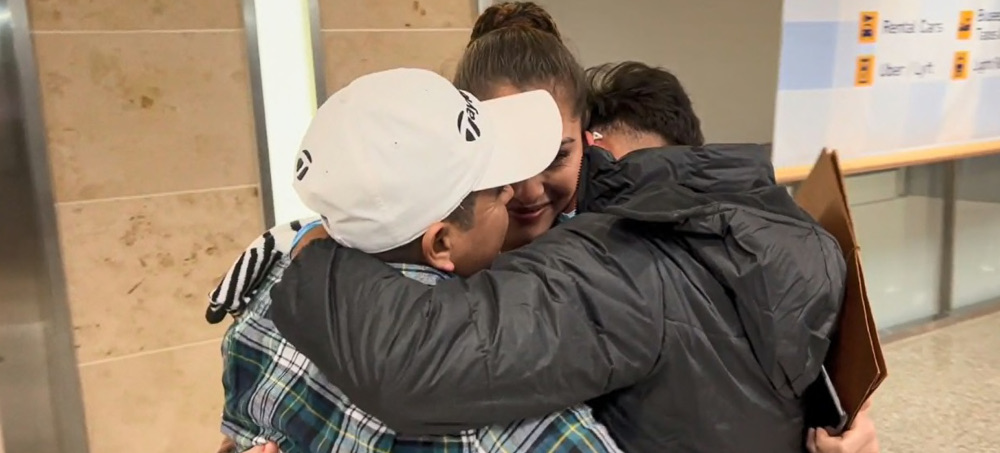

The family was apart for over two months after their separation at the border. (photo: Jamia Bonmati/Telemundo)

The family was apart for over two months after their separation at the border. (photo: Jamia Bonmati/Telemundo)

A Teen Gave ICE His Birth Certificate. Agents Destroyed It and Isolated Him, the Family Says.

Damià Bonmatí and Belisa Morillo, Telemundo

Excerpt: "A teen from Nicaragua said he was 'terrified' after being separated from his parents for several weeks after the family said border authorities questioned his birth certificate and whether he was under 18."

“I felt terrified of being alone, in another country, without a mother and without a father," said the 16-year-old Nicaraguan immigrant after weeks away from his parents.

A teen from Nicaragua said he was "terrified" after being separated from his parents for several weeks after the family said border authorities questioned his birth certificate and whether he was under 18.

“I felt terrified of being alone, in another country, without a mother and without a father. When we came here I didn’t think I was going to go through this,” the 16-year-old told Noticias Telemundo Investiga.

The teen's name was withheld since he's afraid the incident may affect his request for asylum.

The teen's family and attorney said he was separated from his parents at the border and processed as an adult, where he was locked up in two Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers for several weeks. In one of them, Pine Prairie Processing Center, in Louisiana, the teen said he spent 18 days in a solitary cell, without seeing sunlight and without social interaction.

“I felt like I lost my mom, my dad, siblings, friends, everything. I felt like I was never going to leave the place. I looked at that closed door and entered into a depression, my body was shaking all over and it would not go away," he said. "I couldn’t even cry anymore. I wanted to die at that moment."

The teen and his family arrived at the Texas border in mid-September seeking asylum from police repression in Nicaragua.

By law, Border Patrol processes parents and their children together. If there are unaccompanied minors, they must be sent to a shelter system of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and not to prisons contracted by ICE.

‘They told me they were going to deport me’

The conflict began at the Border Patrol station in Eagle Pass, Texas, according to the family’s account. One night in mid-September they managed to cross the almost dry river with other Nicaraguans, celebrating their arrival in the United States and surrendering to border authorities at dawn to make a case for asylum.

But when the family gave authorities the teen's birth certificate, they said the border agents doubted that they were a family. The son burst into tears, according to his own account.

“They started telling me, ‘Tell us your real age.’ And about 20 times I repeated the same thing: 16 years, 16 years," he said, "They got angry with me and told me that they were going to take me and my family in prison for 10 years, and that they were going to deport me."

The teenager said that he signed a rudimentary and improvised sheet of paper that the agents gave him, in which they only wrote his name and that he was 18 years old. He claims that he felt intimidated and forced to do so amid screams and threats from two border patrol officers.

Asked for comment by Noticias Telemundo Investiga, Border Patrol did not respond to the teen's specific case, but said that it collects biometric and biographical information and official documents to determine the age and family relationship of migrants. The agency stated: "When assessing the validity of a family relationship, CBP also relies on articulable observations, such as interactions between the adult and child, to assess whether a family relationship exists."

‘We didn’t see him again’

The teen's mother, Luz Zelaya, said that agents tore up the son's birth certificate, a printed document that states that the minor was born in a municipality in eastern Nicaragua in 2005. It was issued by local authorities days before his departure, at the end of August, the family said.

Zelaya said an agent said the document "is of no use," tore it into pieces and threw it in the trash. "‘You’re lying to me. I’m not stupid,' he tells me," said Zelaya, who's 29 and had her child when she was a young teen. She and her son traveled with her husband of over a decade, who is not the teen's biological father.

After the incident, "we didn’t see him again," she said about her son.

The minor's family said he was detained for a few days by the Border Patrol in Texas, along with about 80 adult men, in a room where “one had to stand, could not even sleep bent over,” the teen said.

They then chained his hands and feet and around the waist, the teenager said, to put him on a plane bound for an ICE detention center for single adults, Adams County Detention Center, in Mississippi.

A spokesman for Customs and Border Protection responded in an email that “migrants in custody who claim or appear to be unaccompanied minors are treated as such until proven otherwise. For example, later it can be determined that they are adults or part of a family unit.”

In the teen's case, however, he wasn't prosecuted as a minor but as an adult.

'Spending 24 hours there was terrible'

After passing through the detention center in Mississippi, the minor was transferred to Pine Prairie Processing Center, in Louisiana, where he said that to his surprise, he was taken directly to a cell in solitary confinement.

He said the cell consisted of a bed, a toilet and a shower that were so close they were almost touching. He spent most hours with his face covered by the blanket so as not to see where he was, he said, and tried to sleep long hours to reduce the time he was conscious and awake.

“There was nothing to do. Spend 24 hours in there, locked up, with the doors locked, without going out. It was terrible. There was no hope of leaving that place," the teen told Noticias Telemundo Investiga.

Upon arriving at that center, the teen said that he interacted with another alleged minor, 17, also Nicaraguan, who was in a solitary cell for about five days. Noticias Telemundo Investiga has not been able to contact this other young man to verify his age.

‘Instances like these are exceptional’

An ICE spokesperson told Noticias Telemundo Investiga: “While ICE has found cases of adults who claim to be minors, and minors who were initially processed as adults, instances like these are exceptional.”

The Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general concluded that ICE needs to improve its oversight of solitary confinement and segregation in detention facilities.

Solitary confinement or segregated cells have been the target of human rights organizations for years. The United Nations said in 2020 that its prolonged use in adults is “psychological torture.” By “prolonged” they meant more than two weeks.

The teen said he was in a segregated cell for 18 days and only managed to get out into an empty courtyard to see sunlight in the last four days. His parents, who were also detained by ICE, were released before their son and were able to proceed with the process of applying for asylum.

Once the parents were released, they contacted an attorney and undertook an arduous task to prove their son was a minor. They sent ICE letters from his teacher in Nicaragua, recent high school photos, and his birth certificate. But the boy was still in the Louisiana cell.

"He was unlawfully detained with adults when ICE had proof that he was a minor. It’s been a lack of transparency with ICE throughout this whole process," said Meredith Soniat du Fossat, a lawyer for American Gateways, an organization that provides assistance to immigrant families.

The attorney said that in her communications with ICE, she was never given a formal explanation for why the teen was in isolation. The teen said his guard told him through an interpreter that it was because he was a minor.

A spokesperson for ICE, which does not comment on specific cases, said to Noticias Telemundo Investiga in a statement: "An individual claiming to be a minor would be held in an appropriate custodial environment and removed from the general population while verification takes place." The spokesperson did not address whether a solitary cell is a part of those protective measures.

It was the minor’s national identity document, which the family worked to obtain from Nicaragua, that changed the situation. The teen said the guard told him that they had already verified that yes, he was a minor.

After about a month and a half in an adult detention facility, the teen was transferred within hours into the custody of HHS, which cares for unaccompanied minors, and was sent to a shelter on the Texas border where he would spend about two weeks.

On Nov. 23, more than two months after being separated from his parents, the teenager got on a plane in McAllen, Texas, heading to his family’s new home. On the plane he took a souvenir selfie, his image looking older and more tired than the images he took of his family's border crossing in September.

At the three airports he went through that day, he looked around strangely. He did not understand the announcements in English that his flight was delayed and the airline escort, who did not speak Spanish, successfully said, “Bathroom?” and he nodded. Carrying a black bag on his right shoulder, he made his way down several empty corridors to his final destination.

‘Thank God, everything was resolved’

At that last airport, in Minnesota, his parents were waiting for him.

The three of them embraced, swinging from one side to the other, as if they wanted to verify that what was happening was real.

"Finally!" the parents said, almost in unison. The father closed his eyes for a few seconds and the mother shed a few tears. The father was carrying a folder with documents about his son in case authorities asked for them.

“Thank God, everything was resolved,” said the mother. "We demonstrated that it was all a misunderstanding."

They got into the old car of a fellow immigrant the parents had recently met who had driven them to the airport. The three of them were crammed into the back, scorched by the car's heat, which couldn't be adjusted. They watched in the dark the outline of small rural towns, where migrant labor is a big part of the agricultural and food processing industry.

Little by little, the three of them fell asleep, resting their heads on one another's shoulders. They looked like an exhausted family.

READ MORE

More than 100 Democrats in the House have called on President Biden to lift U.S. regulations on Cuba. (photo: Getty)

More than 100 Democrats in the House have called on President Biden to lift U.S. regulations on Cuba. (photo: Getty)

More Than 100 House Democrats Urge Biden to Lift Restrictions on Cuba Amid Crisis

The Hill

Excerpt: "More than 100 Democrats in the House have called on President Biden lift U.S. regulations on Cuba in order to help address 'the worst economic and humanitarian crisis in recent history.'"

More than 100 Democrats in the House have called on President Biden lift U.S. regulations on Cuba in order to help address "the worst economic and humanitarian crisis in recent history."

The lawmakers, led by Democratic Reps. Jim McGovern (Mass.), Barbara Lee (Calif.) and Bobby Rush (Ill.), urged Biden in a letter to do away with specific licenses that are required to send medical supplies to Cuba as well as lift restrictions on banking and related financial transactions.

The U.S. embargo against Cuba does technically allow for humanitarian aid to be shipped to the island nation. However, fear of accidentally violating U.S. law stops humanitarian aid from being sent from the U.S. and other countries, according to the lawmakers.

Protests broke out in Cuba this year against the ruling Communist Party as the COVID-19 pandemic placed pressure on living conditions. In the largest anti-government protest that Cuba has seen in decades, Cubans called for President Miguel Díaz-Canel to step down. Protesters also demonstrated against the lack of food and medicine in the country.

The government cracked down on protesters by deploying security officers and government supporters to picket the homes of activists and dissidents.

The House Democrats asked that Biden lift restrictions on family remittances and travel to Cuba in order to allow Cuban-Americans to send financial support and to visit the country in order to reunite with their family members.

They stated that revenue generated from remittances into Cuba goes toward food, fuel and other essential goods that Cubans need.

"In addition to these immediate steps, we believe that a policy of engagement with Cuba serves U.S. interests and those of the Cuban people. It should lead to a more comprehensive effort to deepen engagement and normalization, including restarting diplomatic engagement at senior levels as well as through the re-staffing of each country's respective embassies," they wrote, adding that it would be a "gesture of good faith" and "in the best interests of the United States."

Apart from helping to alleviate the worsening conditions in Cuba, the U.S. representatives argued that approaching Cuba from a position of "principled engagement" instead of "unilateral isolation" would allow the U.S. to bolster human rights in Cuba.

"Engagement is more likely to enable the political, economic, and social openings that Cubans may desire, and to ease the hardships that Cubans face today," they wrote.

During his time in office, former President Obama moved to normalize relations with Cuba, with the Communist country being removed from the U.S. State Sponsors of Terrorism list. However, former President Trump moved to put a stop to some of the Obama-era agreements and issued tightened travel restrictions.

READ MORE

Wildlife commissioners signed onto a multi-state plan as states in the northern Rockies push to ease federal protections. (photo: Reuters)

Wildlife commissioners signed onto a multi-state plan as states in the northern Rockies push to ease federal protections. (photo: Reuters)

Montana Could Soon Allow Grizzly Bear Hunting for First Time in Decades

Associated Press

Excerpt: "Montana wildlife officials could soon allow grizzly bear hunting in areas around Glacier and Yellowstone national parks, if states in the US northern Rockies succeed in their attempts to lift federal protections for the animals."

Wildlife commissioners signed onto a multi-state plan as states in the northern Rockies push to ease federal protections

Montana wildlife officials could soon allow grizzly bear hunting in areas around Glacier and Yellowstone national parks, if states in the US northern Rockies succeed in their attempts to lift federal protections for the animals.

Grizzlies in the region have been protected as a threatened species since 1975 and were shielded from hunting for most of that time. But several states are pushing for restrictions to be eased.

Montana governor Greg Gianforte last month announced the state intends to petition the Biden administration to lift threatened species protections for Glacier-area grizzlies. Wyoming governor Mark Gordon is leading a similar push to end protections for Yellowstone area bears.

The two regions have the most bears in the US outside Alaska, the only state that currently allows hunting.

As officials seek to make the case that protections are no longer needed, Montana wildlife commissioners on Tuesday voted to sign onto a multistate plan to maintain more than 900 bears in the Yellowstone area. Wyoming already has signed onto the plan, which would allow limited hunting. Idaho officials are expected to consider it next month.

Montana commissioners also gave preliminary approval to revisions to Glacier-area bear population targets that could allow hunting of grizzlies in northwestern portions of the state if federal protections end. The rule calls for maintaining a population of more than 800 bears.

Details on any future hunting seasons would be established at a later date.

Wildlife advocates have objected to the bid to lift protections, saying state officials in the northern Rockies are intent on driving down populations of grizzlies and another predator, gray wolves.

But state officials, backed by livestock and hunting groups, say bear populations need to be more closely controlled. They cite increasing conflicts between bears and humans, including attacks on livestock and occasional maulings of people

As many as 50,000 grizzly bears once ranged the western half of the US. Most were killed by hunting, trapping and habitat loss following the arrival of European settlers in the late 1800s. Populations declined to fewer than 1,000 bears in the lower 48 states by the time they were given federal protections in 1975.

The last grizzly hunts in the US outside Alaska were in the early 1990s, under an exemption to protections that allowed 14 bears to be killed each fall in Montana.

When Yellowstone grizzlies briefly lost protections under Donald Trump’s administration, Wyoming and Idaho scheduled hunts for 22 bears in Wyoming and one in Idaho, with hunting permits offered by lottery. A federal judge stepped in at the last minute and restored protections, a decision later upheld by the ninth US circuit court of appeals.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service recommended in March to keep threatened-species protections for grizzlies. The agency cited a lack of connections between the bears’ best areas of habitat and people killing them, among other reasons.

READ MORE

Contribute to RSN

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Update My Monthly Donation

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611