Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Background

Inspectors general are semi-independent watchdogs that conduct audits and investigations of executive branch actions and that have special reporting obligations to Congress. When first created in 1978, they were constitutionally controversial. The Office of Legal Counsel opined that their divided obligations to the executive branch and Congress “violate the doctrine of separation of powers.” In 1998, a bipartisan panel of luminaries—including Howard Baker, Griffin Bell, Lloyd Cutler, William Barr, Andrew Card, Lawrence Eagleburger and William Webster—criticized inspectors general as “congressional ferrets of dubious constitutionality.” During Barr’s first tenure as Attorney General from 1991 to 1993, he viewed the inspector general as a “constant irritant” and “tried to slap [their] wrists … and curtail their authority.” This was an unsurprising judgment since the inspector general is an affront to the unitary executive theory to which Barr subscribes.

Fast forward to Barr’s second stint as attorney general. In 2018, Barr stated that he had “become more sanguine” about the office of the inspector general, which serves a “critical function in the government.” When Justice Department Inspector General Michael Horowitz released his 2019 report on the investigation of the 2016 Trump presidential campaign, Barr publicly disagreed with Horowitz’s conclusion that the FBI properly opened the investigation. And yet Barr reaffirmed the legitimacy of the inspector general and his report, and he indeed confirmed the inspector general’s importance to the department. “The Inspector General’s investigation has provided critical transparency and accountability, and his work is a credit to the Department of Justice,” Barr said.

Barr was not puffing, as became clear when he relied on Horowitz to squirm out of the controversy that arose when former President Trump in 2020 fired Acting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Geoffrey Berman. Critics worried that Trump intervened to protect himself from ongoing criminal investigations. This concern grew when Barr tried to replace Berman with a Trump loyalist. In the face of intense controversy, Barr backed down and appointed a career prosecutor instead. And to further alleviate criticism, Barr stated that if any senior lawyer in the Southern District experienced “improper interference with a case,” he or she should report the matter to the Justice Department inspector general, whom Barr “authoriz[ed] to review any such claim”—a step Barr claimed would “provide additional confidence that all cases will continue to be decided on the law and the facts.”

Barr’s evolution from trying to curtail inspector general authority as a challenge to the unitary executive in the 1990s to expanding its authority to make the Justice Department’s prosecutorial judgments credible in 2020 is a testament to the central and accepted role that the office of inspector general plays today in securing executive branch accountability. Inspectors general are far from perfect, of course, and some of them sometimes make mistakes or go too far. But in numerous significant matters, they have effectively investigated controversial executive branch actions, clearly and fairly reported what happened, identified wrongdoing and exonerated those wrongly accused, made recommendations about how to improve the performance of the executive branch, and reported these matters to Congress and the public.

Reforms

The three bills being considered tomorrow cover a range of issues. The main ones fall into three categories:

Independence-Enhancing Provisions

Two of the bills respond in different ways to the practice by past presidents—most notably, but not exclusively, Trump—of firing inspectors general on questionable grounds and replacing them with more congenial but less independent officials who lack Senate confirmation.

The president runs the executive branch and sometimes has good reasons to terminate an inspector general—for incompetence, malfeasance and the like. Current law allows the president to do so for any reason, but requires the president to send a letter to Congress 30 days before removal that explains the reason. This has not proven much of a limitation. The only reason that President Obama gave Congress when he fired the inspector general for the Corporation for National and Community Service in 2009 was that he lacked “the fullest confidence” in the inspector general. Trump followed this practice.

The IG Independence and Empowerment Act tries to raise the bar to presidential firings of inspectors general by limiting removal to specified grounds. One of us has previously explained why such “for cause” restrictions won’t work. First, it likely will not survive scrutiny in the Supreme Court, which increasingly frowns on presidential removal restrictions. Second, the removal limitations won’t work in any event: A determined president can find a way to invoke one of the open-ended removal criteria (such as “gross mismanagement,” “abuse of authority” or “inefficiency”) to fire an inspector general. Third, many of the most questionable presidential inspector general firings concerned “acting” inspectors general who would not receive for-cause protection.

A different bill, the Securing Inspector General Independence Act of 2021, aims to slow down the firing process by, for example, limiting the president’s power to place an inspector general on “administrative leave” during the thirty-day notice period before firing. This is a better step, though a relatively small one.

The best idea is for Congress to dry up presidents’ incentives for opportunistic firings, and to limit the adverse effects of such firings when they occur. Both bills aim to do this by disallowing presidents to replace a fired inspector general with a political friend and requiring them to fill the vacancy with a senior non-political official in the office of the fired inspector general or from another inspector general office. This approach would be effective and is clearly constitutional. It is the single most important step Congress can take to secure inspector general independence.

Extending Inspector General Jurisdiction to Justice Department Attorneys

Under current law, the Justice Department’s Office of Professional (OPR), which was created in the wake of Watergate, is charged with “investigat[ing] allegations that Department attorneys, prosecutors, and immigration judges have committed misconduct while performing their duties to investigate, litigate, or give legal advice.” This OPR authority is expressly carved out of the Justice Department inspector general’s authority. The IG Independence and Empowerment Act would eliminate this carve-out and extend inspector general authority to investigating allegations of misconduct against Justice Department attorneys.

One argument for the change is that the OPR lacks independence (the OPR reports to the attorney general) and adequate transparency, while the inspector general has lots of both. The inspector general also has more credibility before Congress and the public. Another argument for change, made by the Project On Government Oversight, is that OPR has not been effective at enforcing ethical compliance by Justice Department attorneys.

The National Association of Assistant United States Attorneys (NAAUSA) opposes this change. The main argument is that the OPR has been doing this job for decades and has relevant expertise, especially in ethics and state bar rules, that the inspector general lacks. There is some truth in this, though the inspector general has significant experience evaluating professional misconduct in a variety of contexts, and other inspectors general around the government are charged with investigating misconduct by lawyers.

The carve out from the Justice Department inspector general’s authority for lawyer misconduct is an anomaly. Justice Department lawyers, especially federal prosecutors, have extraordinary and largely unchecked power over prosecution and asset seizure. This power deserves a serious check for abuse akin to the one that applies to almost every other aspect of executive branch activity. Even the NAAUSA recognizes the need for independent scrutiny for Justice Department attorneys, since it now advocates that the OPR be made independent. It is not clear whether transferring the OPR authority to the inspector general, or making OPR a more serious and independent operation, or some other reform, is the right answer. But this is clearly an area where Congress should weigh in.

External Subpoena Authority

The IG Testimonial Subpoena Authority Act and the IG Independence and Empowerment Act would in different ways extend the inspector general’s subpoena authority to witnesses who are not current government employees. The argument for this power is that the inspector general is often stymied in its investigations by its inability to compel the testimony of former officials and non-governmental witnesses. This is true, and it is a powerful point. But this expansion of inspector general authority would be a huge change from current practice in the inspector general community, and it would significantly enhance the already quite robust power of inspectors general.

More power is not always better, and the hard question is whether this new authority would enhance inspector general power too much. Inspectors general have done excellent work without this broader authority, leaving it to the press, Congress and other investigators to fill in the holes in its report created by its lack of access to witnesses outside the government. One mark of how significant a change this new authority would make is that even its proponents would require an inspector general to consider attorney general objections before issuing the subpoena and would impose oversight by a panel of the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, the inspector general-run watchdog for inspectors general.

Once again, the right answer here is not clear. Perhaps a better first step is to require attorney general approval for the expanded subpoena authority with defined criteria for exercising such authority and a reporting requirement to Congress to explain any attorney general refusal to extend the authority.

Then-Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen at the White House on Sept. 26, 2020. (photo: Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

Then-Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen at the White House on Sept. 26, 2020. (photo: Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

The interim report by the Senate Judiciary Committee was issued Thursday. While Republicans on the panel offered their counter-findings, arguing that Trump did not subvert the justice system to remain in power, the majority report by the Democrats offers the most detailed account to date of the struggle inside the administration’s final, desperate days.

On Jan. 3, then-acting attorney general Jeffrey Rosen, his deputy Richard Donoghue, and a few other administration officials met in the Oval Office for what all expected to be a final confrontation on Trump’s plan to replace Rosen with Jeffrey Clark, a little-known Justice Department official who had indicated he would publicly pursue Trump’s false claims of mass voter fraud.

According to testimony Rosen gave to the committee, Trump opened the meeting by saying, “One thing we know is you, Rosen, aren’t going to do anything to overturn the election.”

For three hours, the officials then debated Trump’s plan, and the insistence by Rosen and others that they would resign rather than go along with it.

The Senate report says that the top White House lawyer, Pat Cipollone, and his deputy also said they would quit if Trump went through with his plan.

During the meeting, Donoghue and another Justice Department official made clear that all of the Justice Department’s assistant attorneys general “would resign if Trump replaced Rosen with Clark,” the report says. “Donoghue added that the mass resignations likely would not end there, and that U.S. Attorneys and other DOJ officials might also resign en masse.”

The details of the report were first reported by the New York Times.

A key issue in the meeting was a letter that Clark and Trump wanted the Justice Department to send to Georgia officials warning of “irregularities” in voting and suggesting the state legislature get involved. Clark thought the letter should also be sent to officials in other states where Trump supporters were contesting winning Biden vote totals, the report said.

Rosen and Donoghue had refused to send such a letter, infuriating Trump. According to the report, the president thought that if he installed Clark as the new attorney general, the letter would go out and fuel his bid to toss out Biden victories in a handful of states.

At one point in the meeting, Cipollone called Clark’s letter a “murder-suicide pact,” for the chain reaction it would be likely to set off inside the government.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), the chairman of the committee, told reporters Trump’s attempt to “take over” the Justice Department was “stopped by a handful of people who stood up for principle and against Trump’s strategy.”

“And then three days later, in desperation, Donald Trump turned the mob loose on this capital,” the senator said, a reference to the Jan. 6 riot of Trump supporters at Congress. “It was a desperate strategy by a desperate man.”

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), said the committee’s interviews show “Jeffrey Rosen conducted himself honorably and the Department of Justice operated as it is designed to.”

A lawyer for Clark did not immediately comment.

Leading up to the Jan. 3 meeting, Trump had pressed Rosen in a string of phone calls to pursue false or fanciful claims of voter fraud. Rosen had largely resisted those entreaties, while saying the department would pursue meaningful allegations of fraud.

Rosen’s predecessor, William P. Barr, had already declared, in early December, that there was no evidence of the kind of widespread voter fraud that could change the outcome of the election.

The counter-report by committee Republicans on Thursday emphasized that Trump ultimately backed away from the plan to replace Rosen with Clark and issue Clark’s letter: “President Trump’s actions were consistent with his responsibilities as President to faithfully execute the law and oversee the Executive Branch,” it says.

Given Trump’s long-running distrust of the FBI’s handling of the 2016 election, the report says, it was “reasonable that President Trump maintained substantial skepticism concerning the DOJ’s and FBI’s neutrality and their ability to adequately investigate election fraud allegations in a thorough and unbiased manner.”

Senate Majority Leader Sen. Chuck Schumer of N.Y., reaches a deal with Republicans for a short-term increase of the debt ceiling. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Senate Majority Leader Sen. Chuck Schumer of N.Y., reaches a deal with Republicans for a short-term increase of the debt ceiling. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Schumer, D-N.Y., announced the agreement on the Senate floor Thursday morning and said the leaders hope to pass the bill, which would increase the borrowing limit by $480 billion, as soon as Thursday afternoon. The Treasury Department estimates that amount should be sufficient to keep the debt payments flowing until Dec. 3.

The White House called the agreement a positive step. "It gives us some breathing room from the catastrophic default we were approaching," said Karine Jean-Pierre, the deputy press secretary.

But the agreement does nothing to resolve the broader standoff between the two parties over how to pass a long-term solution.

McConnell went to the Senate floor shortly after the deal was announced to reiterate that he wants Democrats to use the budget reconciliation process to pass a debt limit hike — a plan Democrats have repeatedly rejected.

"The pathway our Democratic colleagues have accepted will spare the American people any near-term crisis while definitively resolving the majority's excuse that they lack the time to address the debt limit through the 304 reconciliation process," McConnell said. "Now there will be no question, they will have plenty of time."

Democrats say they are not going to cave to McConnell's demands. They argue that tying the debt limit to budget reconciliation creates a dangerous precedent and allows Republicans to skirt their responsibility for debt that has already been accrued.

Reconciliation allows the Senate to pass some budget and spending related legislation without the threat of a filibuster but it has limitations. It is traditionally a tool that can only be used once every fiscal year. Recent interpretations from the Senate Parliamentarian, the non-partisan rule keeper in the Senate, allow for some narrow exceptions to the once-a-year rule, but it is still a limited tool.

Democrats are also wary of being forced into a procedural corner by McConnell. The fight over that process has not been addressed with this agreement, meaning the bitter fight will likely continue for the next two months.

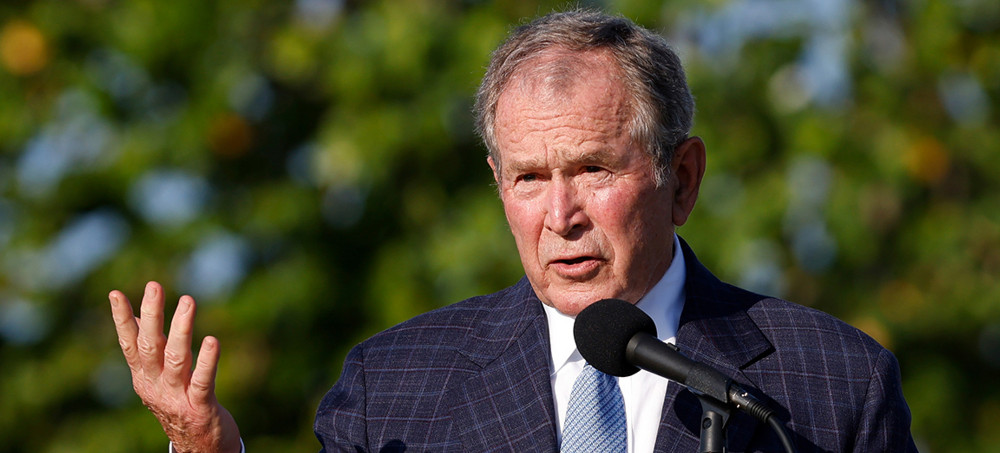

George W. Bush, who launched the war on terror following the 9/11 attacks. (photo: Cliff Hawkins/Getty)

George W. Bush, who launched the war on terror following the 9/11 attacks. (photo: Cliff Hawkins/Getty)

Note for TomDispatch Readers: In her new book, Subtle Tools: The Dismantling of American Democracy from the War on Terror to Donald Trump, TD regular Karen Greenberg takes us from Ground Zero to January 6th, exploring just how policies originally meant to fight the war on terror were “weaponized” at home as well, especially in the age of Trump. This is stuff we need to know, so do pick up a copy. If, however, you want to have your own personalized, signed version of the book (I already have mine!), visit our donation page. For a minimum gift of $100 ($125 if you live outside the USA), it’s yours — and you’ll be helping TomDispatch carry on the good fight while you’re at it. By the way, the next TD piece will appear on the Tuesday after this holiday weekend. Tom]

Just in case you didn’t realize it, the lost war in Afghanistan was their fault, not ours. If we had any fault at all, as Secretary of Defense and former Iraq War commander Lloyd Austin pointed out at a Senate hearing last week, it was not fully grasping how bad our Afghan allies — in other words, the very government and military we had created there — were. “We need to consider some uncomfortable truths,” he said. “That we didn’t fully comprehend the depth of corruption and poor leadership in the senior ranks. That we didn’t grasp the damaging effect of frequent and unexplained rotations by President Ghani of his commanders.” Oh yeah, and maybe that weird president we had not so long ago had something to do with it, too, when he reached an agreement with the Taliban at Doha, Qatar, for the withdrawal of American troops. As Austin put it: “And that the Doha agreement itself had a demoralizing effect on Afghan soldiers.”

The only people who had nothing to do with disaster in that country, it seems, were the splendid generals of the U.S. military who commanded up to 100,000 American troops and monumental air power against the Taliban at the height of the war and have never wanted to give up the ghost. As we now know, until the very last moment (almost 20 years of devastating failure after it began), they were still “advising” President Biden not to withdraw our troops from that land.

Honestly, our commanders who, like Austin, often enough made literal fortunes off their war records, should be ashamed and yet, two disastrous decades later, there isn’t an apology in sight, as TomDispatch regular Karen Greenberg (whose new book, Subtle Tools: The Dismantling of American Democracy from the War on Terror to Donald Trump, couldn’t be more appropriate to this moment) lays out with all-too-painful clarity.

-Tom Engelhardt, TomDispatch

For some, the memory of that horrific day included headshaking over the mistakes this country made in responding to it, mistakes we live with to this moment.

Among the more prominent heads being shaken over the wrongdoing that followed 9/11, and the failure to correct any of it, was that of Jane Harman, a Democrat from California, who was then in the House of Representatives. She would join all but one member of Congress — fellow California representative Barbara Lee — in voting for the remarkably vague Authorization for the Use of Force, or AUMF, which paved the way for the invasion of Afghanistan and so much else. It would, in fact, put Congress in cold storage from then on, allowing the president to bypass it in deciding for years to come whom to attack and where, as long as he justified whatever he did by alluding to a distinctly imprecise term: terrorism. So, too, Harman would vote for the Patriot Act, which would later be used to put in place massive warrantless surveillance policies, and then, a year later, for the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq (based on the lie that Iraqi ruler Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction).

But on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the attacks, Harman offered a different message, one that couldn’t have been more appropriate or, generally speaking, rarer in this country — a message laced through and through with regret. “[W]e went beyond the carefully tailored use of military force authorized by Congress,” she wrote remorsefully, referring to that 2001 authorization to use force against al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden. So, too, Harman railed against the decision, based on “cherry-picked intelligence,” to go to war in Iraq; the eternal use of drone strikes in the forever wars; as well as the creation of an offshore prison of injustice at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and of CIA black sites around the world meant for the torture of prisoners from the war on terror. The upshot, she concluded, was to create “more enemies than we destroyed.”

Such regrets and even apologies, while scarce, have not been utterly unknown in post-9/11-era Washington. In March 2004, for example, Richard Clarke, the counterterrorism chief for the Bush White House, would publicly apologize to the American people for the administration’s failure to stop the 9/11 attacks. “Your government failed you,” the former official told Congress and then proceeded to criticize the decision to go to war in Iraq as well. Similarly, after years of staunchly defending the Iraq War, Senator John McCain would, in 2018, finally term it “a mistake, a very serious one,” adding, “I have to accept my share of the blame for it.” A year later, a PEW poll would find that a majority of veterans regretted their service in Afghanistan and Iraq, feeling that both wars were “not worth fighting.”

Recently, some more minor players in the post-9/11 era have apologized in unique ways for the roles they played. For instance, Terry Albury, an FBI agent, would be convicted under the Espionage Act for leaking documents to the media, exposing the bureau’s policies of racial and religious profiling, as well as the staggering range of surveillance measures it conducted in the name of the war on terror. Sent to prison for four years, Albury recently completed his sentence. As Janet Reitman reported in the New York Times Magazine, feelings of guilt over the “human cost” of what he was involved in led to his act of revelation. It was, in other words, an apology in action.

As was the similar act of Daniel Hale, a former National Security Agency analyst who had worked at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan helping to identify human targets for drone attacks. He would receive a 45-month sentence under the Espionage Act for his leaks — documents he had obtained on such strikes while working as a private contractor after his government service.

As Hale would explain, he acted out of a feeling of intense remorse. In his sentencing statement, he described watching “through a computer monitor when a sudden, terrifying flurry of Hellfire missiles came crashing down, splattering purple-colored crystal guts.” His version of an apology-in-action came from his regret that he had continued on at his post even after witnessing the horrors of those endless killings, often of civilians. “Nevertheless, in spite of my better instinct, I continued to follow orders.” Eventually, a drone attack on a woman and her two daughters led him over the brink. “How could I possibly continue to believe that I am a good person, deserving of my life and the right to pursue happiness” was the way he put it and so he leaked his apology and is now serving his time.

“We Were Wrong, Plain and Simple”

Outside of government and the national security state, there have been others who struck a chord of atonement as well. On the 20th anniversary of 9/11, for instance, Jameel Jaffer, once Deputy Legal Director of the ACLU and now head of the Knight First Amendment Institute, took “the opportunity to look inward.” With some remorse, he reflected on the choices human-rights organizations had made in campaigning against the abuse and torture of war-on-terror prisoners.

Jaffer argued that their emphasis should have been less on the degradation of American “traditions and values” and more on the costs in terms of human suffering, on the “experience of the individuals harmed.” In taking up the cases of individuals whose civil liberties had often been egregiously violated in the name of the war on terror, the ACLU revealed much about the damage to their clients. Still, the desire to have done even more clearly haunts Jaffer. Concluding that we “substituted a debate about abstractions for a debate about prisoners’ specific experiences,” Jaffer asks, “[I]s it possible” that the chosen course of the NGOs “did something more than just bracket prisoners’ human rights — that it might have, even if only in a small way, contributed to their dehumanization as well?”

Jonathan Greenblatt, now head of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), spoke in a similarly rueful fashion about that organization’s decision to oppose plans for a Muslim community center in lower Manhattan, near Ground Zero — a plan that became known popularly as the “Ground Zero Mosque.” As the 20th anniversary approached, he said bluntly, “We owe the Muslim community an apology.” The intended center fell apart under intense public pressure that Greenblatt feels the ADL contributed to. “[T]hrough deep reflection and conversation with many friends within the Muslim community,” he adds, “the real lesson is a simple one: we were wrong, plain and simple.” The ADL had recommended that the center be built in a different location. Now, as Greenblatt sees it, an institution that “could have helped to heal our country as we nursed the wounds from the horror of 9/11” never came into being.

The irony here is that while a number of those Americans least responsible for the horrors of the last two decades have directly or indirectly placed a critical lens on their own actions (or lack thereof), the figures truly responsible said not an apologetic word. Instead, there was what Jaffer has called an utter lack of “critical self-reflection” among those who launched, oversaw, commanded, or supported America’s forever wars.

Just ask yourself: When have any of the public officials who ensured the excesses of the war on terror reflected publicly on their mistakes or expressed the least sense of regret about them (no less offering actual apologies for them)? Where are the generals whose reflections could help forestall future failed attempts at “nation-building” in countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, or Somalia? Where are the military contractors whose remorse led them to forsake profits for humanity? Where are any voices of reflection or apology from the military-industrial complex including from the CEOs of the giant weapons makers who raked in fortunes off those two decades of war? Have any of them joined the small chorus of voices reflecting on the wrongs that we’ve done to ourselves as a nation and to others globally? Not on the recent 9/11 anniversary, that’s for sure.

Looking Over Your Shoulder or Into Your Heart?

What we still normally continue to hear instead is little short of a full-throated defense of their actions in overseeing those disastrous wars and other conflicts. To this day, for instance, former Afghan and Iraq War commander David Petraeus speaks of this country’s “enormous accomplishments” in Afghanistan and continues to double down on the notion of nation-building. He still insists that, globally speaking, Washington “generally has to lead” due to its “enormous preponderance of military capabilities,” including its skill in “advising, assisting, and enabling host nations’ forces with the armada of drones we now have, and an unequal[ed] ability to fuse intelligence.”

Similarly, Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster, national security advisor to Donald Trump, had a virtual melt down on MSNBC days before the anniversary, railing against what he considered President Biden’s mistaken decision to actually withdraw all American forces from Afghanistan. “After we left Iraq,” he complained, “al-Qaeda morphed into ISIS, and we had to return.” But it didn’t seem to cross his mind to question the initial ill-advised and falsely justified decision to invade and occupy that country in the first place.

And none of this is atypical. We have repeatedly seen those who created the disastrous post-9/11 policies defend them no matter what the facts tell us. As a lawyer in the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel, John Yoo, who wrote the infamous memos authorizing the torture of war-on-terror detainees under interrogation, followed up the 2011 killing of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan with a call for President Obama to “restart the interrogation program that helped lead us to bin Laden.” As the Senate Torture Report on Interrogation would conclude several years later, the use of such brutal techniques of torture did not in fact lead the U.S. to bin Laden. On the contrary, as NPR has summed it up, “The Senate Intelligence Committee came to the conclusion that those claims are overblown or downright lies.”

Among the unrepentant, of course, is George W. Bush, the man in the White House on 9/11 and the president who oversaw the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as the securitization of key American institutions and policies. Bush proved defiant on the 20th anniversary. The optics told it all. Speaking to a crowd at Shanksville, Pennsylvania, where that hijacked plane with 40 passengers and four terrorists crashed on 9/11, the former president was flanked by former Vice President Dick Cheney. His Machiavellian oversight of the worst excesses of the war on terror had, in fact, led directly to era-defining abrogations of laws and norms. But no apologies were forthcoming.

Instead, in his speech that day, Bush highlighted in a purely positive fashion the very policies his partnership with Cheney had spawned. “The security measures incorporated into our lives are both sources of comfort and reminders of our vulnerability,” he said, giving a quiet nod of approval to policies that, if they were “comforting” in his estimation, also defied the rule of law, constitutional protections, and previously sacrosanct norms limiting presidential power.

Over the course of these 20 years, this country has had to face the hard lesson that accountability for the mistakes, miscalculations, and lawless policies of the war on terror has proven not just elusive, but inconceivable. Typically, for instance, the Senate Torture Report, which documented in 6,000 mostly still-classified pages the brutal treatment of detainees at CIA black sites, did not lead to any officials involved being held accountable. Nor has there been any accountability for going to war based upon that lie about Iraq’s supposed weapons of mass destruction.

Instead, for the most part, Washington has decided all these years later to continue in the direction outlined by President Obama during the week leading up to his 2009 inauguration. “I don’t believe that anybody is above the law,” he said. “On the other hand, I also have a belief that we need to look forward as opposed to looking backwards… I don’t want [CIA personnel and others to] suddenly feel like they’ve got to spend all their time looking over their shoulders and lawyering.”

Looking over their shoulders is one thing, looking into their own hearts quite another.

The recent deaths of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, who, among other horrors, supervised the building of Guantanamo and the use of brutal interrogation techniques there and elsewhere and of former CIA General Counsel John Rizzo, who accepted the reasoning of Department of Justice lawyers when it came to authorizing torture for his agency, should remind us of one thing: America’s leaders, civilian and military, are unlikely to rethink their actions that were so very wrong in the war on terror. Apologies are seemingly out of the question.

So, we should be thankful for the few figures who courageously breached the divide between self-righteous defensiveness when it came to the erosion of once-hallowed laws and norms and the kind of healing that the passage of time and the opportunity to reflect can yield. Perhaps history, through the stories left behind, will prove more competent when it comes to acknowledging wrongdoing as the best way of looking forward.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Karen J. Greenberg, a TomDispatch regular, is the director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law and author of the newly published Subtle Tools: The Dismantling of Democracy from the War on Terror to Donald Trump (Princeton University Press). Julia Tedesco helped with research for this piece.

Whistleblower Chelsea Manning. (photo: Eric barada/Getty)

Whistleblower Chelsea Manning. (photo: Eric barada/Getty)

Bizarre request made ahead of immigration hearing for Manning, whose previous attempts to enter Canada have been denied

The bizarre request, which was eventually denied by an adjudicator, was made ahead of an immigration hearing set to begin on Thursday for Manning, whose previous attempts to enter Canada have been denied.

Manning, a former US intelligence analyst who leaked thousands of sensitive government documents and diplomatic cables about the American wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to WikiLeaks, was sentenced to 35 years in prison in 2013.

Her sentence was commuted in 2017, but she was recently denied entry into Canada because of her conviction.

Border officials can deem persons ineligible for entry into Canada if they have been convicted of crimes abroad that would have led to a jail sentence in Canada of 10 years or more.

Last week, lawyers for the government asked that she travel to the country so that if the government won its case, she could be removed. Manning’s lawyers had said she would attend the hearing virtually, from her home in the United States.

“The purpose of a removal order is to compel an individual who is found to be inadmissible to leave Canada. Should the [Immigration Review Board] issue a removal order against an individual who does not attend their hearing from a location in Canada,” the government told the IRB in documents obtained by the National Post, arguing it would “be impractical for CBSA to enforce the order”.

But that line of reasoning made little sense to the IRB adjudicator Marisa Musto, who dismissed the government’s motion on Monday.

“If she were physically in Canada when the order was made, the requirement would be that she leave Canada. Given that she is already outside Canada, a fact which is not in question, it can be said that the ‘objective’ of [immigration laws] … would, de facto, be fulfilled,” Musto said in her ruling, calling the government’s request “confounding”.

Manning’s lawyers have fiercely contested the ban on her entering Canada, arguing that an attempt by the country’s federal government to block “one of the most well-known whistleblowers in modern history” from entering the country would offend constitutional and press freedoms.

The hearing is expected to last two days, with a judgment issued in the coming weeks.

An Afghan family in Bosnia near the Croatian border in December 2020. (photo: Marc Sanye/Getty)

An Afghan family in Bosnia near the Croatian border in December 2020. (photo: Marc Sanye/Getty)

EU members have denied people the right to seek asylum, Lighthouse Reports says, alleging physical abuse in some cases.

The findings, published on Wednesday by the Amsterdam-based investigative news organisation Lighthouse Reports, reveal that masked security forces and police units in the three EU member states have repeatedly taken coordinated, clandestine action to prevent asylum seekers from crossing their borders.

The allegations add to concerns among rights groups, which have been documenting an intensified use of pushbacks and slammed the EU’s alleged complicity in the operations.

Under international and EU human rights laws, it is illegal for states to automatically expel people without assessing their circumstances. EU law also guarantees the right to seek asylum.

The investigation by Lighthouse Reports took place over eight months, in collaboration with European media partners including the German news magazine Der Spiegel and French newspaper Libération.

With video footage, satellite imagery, witness testimony and interviews with more than a dozen serving and former police and coast guard officers, they determined that at least 189 people had been illegally denied access to the European asylum system, which they claimed was “a small sample of pushbacks”.

Pushbacks ‘commonplace’ at EU’s borders

Lighthouse Reports documented 11 pushbacks in Croatia, the newest EU member state, between May and September this year at four locations along the country’s border with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Croatian riot police carried out the pushbacks as part of a national strategy codenamed “Koridor”, which is part-funded by the EU, police whistleblowers told the outlet.

In one incident in June, a group of Afghans and Pakistanis requested asylum when they encountered Croatian police, but were forced across the Korana river, back into Bosnia and Herzegovina.

During the pushback, police allegedly beat the refugees with batons, leaving them with bruises.

Al Jazeera was unable to independently verify those claims but undated video footage shared by Lighthouse Reports appears to show several people crossing a river while being beaten by at least two armed individuals dressed entirely in black and wearing balaclavas.

Jelena Sesar, Amnesty International’s Balkans researcher, said it was “clear” the masked men were Croatian riot police, as their uniforms, weapons and equipment were identical to those issued to members of the unit.

“This is the latest evidence that unlawful pushbacks and violence against asylum-seekers and migrants are commonplace at the EU’s external borders,” Sesar said.

“In numerous countries … people in search of safety and protection are being met with barbed wire and armed border guards,” she told Al Jazeera, adding that the EU’s migration policy had “for years now prioritised border security over the rights of people and its fundamental values”.

‘Frequent violations’

In Greece, Lighthouse Reports collected publicly available video footage of 635 alleged pushbacks since March 2020.

Masked individuals were involved in 15 incidents, the news outlet alleged, including one which saw 25 asylum seekers on a rubber dinghy reportedly blocked from reaching shore on the Aegean island of Kos. They were told to “get a passport if they want to travel”. The Turkish coast guard reportedly picked up the group later.

Current and former officers in the Greek coast guard who were shown footage of that incident identified the masked individuals as members of elite coast guard units.

The whistleblowers described how orders to repel refugees were “always” given orally, because of their illegality.

In Romania, Lighthouse Reports used remote, motion-activated cameras, to film uniformed border guards forcing men and women into neighbouring Serbia in three separate incidents.

Tracked down by the investigative team, some claimed to have been physically assaulted during the pushback.

Two border guards speaking anonymously to Lighthouse Reports said Romanian police routinely conduct pushbacks to Serbia.

Catherine Woollard, director of the European Council on Refugees and Exiles, an alliance of more than 100 NGOs in 39 European countries, said the findings added to “emerging evidence that pushbacks are taking place systematically” at EU borders with the bloc’s “complicity”.

She told Al Jazeera that some member states act with “impunity” and called for EU action to protect human rights laws.

“We currently have a situation where there is tolerance or even normalisation of some of these violations, up to and including the use of extreme violence against people seeking protection,” Woolard said.

“There’s an unwillingness of the EU to act, because the general strategy in Europe is based on prevention of arrivals of people seeking protection, regardless of the costs and the consequences.

“So there is either a lack of action, which means the states can continue to carry out these pushbacks with impunity or in the worst cases, support for the member states.”

Brussels turning ‘blind eye’

Amnesty’s Sesar said it was “alarming” that the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, continues to turn a “blind eye to the staggering violation of EU law, and even continues to finance police and border operations in some of these countries”.

“These pushbacks and the funding that facilitates them must end now,” she said.

In response to the latest findings, the European Commission said it “strongly opposes any pushback practices, and has repeatedly emphasised that any such practices are illegal”.

“National authorities have the responsibility to investigate any allegations, with a view to establishing the facts and to properly follow up on any wrongdoing,” a spokesperson for the EU’s executive arm said.

Greek migration minister Notis Mitarachi denied the allegations.

“Europe remains the target of criminal gangs who are exploiting people who wish to enter the EU illegally,” he tweeted. “We make no apology for our continued focus on breaking up these human trafficking operations, and protecting Europe’s border.”

Croatia said it would investigate the allegations.

At the time of publication, the Romanian foreign affairs ministry had not responded to Al Jazeera’s request for comment.

Biologist Todd Atwood, left, and his USGS colleague examine a sedated polar bear. Thinning ice on the southern Beaufort Sea has precluded such examinations for the last three years. (photo: Todd Atwood)

Biologist Todd Atwood, left, and his USGS colleague examine a sedated polar bear. Thinning ice on the southern Beaufort Sea has precluded such examinations for the last three years. (photo: Todd Atwood)

The melting ice is affecting the bears’ behavior and physical condition, and it has made studying them through forays out onto the ice a treacherous business.

A wildlife biologist and the leader of the U.S. Geological Survey’s polar bear research program, Atwood would normally be in a helicopter, flying over the ice-bound southern Beaufort Sea looking for bears.

Instead, he was planted at his desk in Deadhorse, scrolling through weather reports; poking his head outside to look at the sky and anxiously clicking through various webcams focused on the Arctic coastline.

Retreating sea ice in the Arctic is crippling scientists’ ability to study and monitor polar bears, Atwood and other experts say. The study of the bears, top-of-the-food-chain carnivores with adorable faces, is critical for conservation of the animals and their environment.

Studies show that the decline of sea ice, driven by climate change, is affecting the behavior and physical condition of polar bears, and making it harder for the animals to find enough food to survive. But fallout from global warming also means that Atwood and other researchers have fewer opportunities to hop in a helicopter for forays over the ice. Normally, polar bear scientists track the status of the bears by spotting them from an aircraft, sedating them and landing nearby to conduct a thorough biological examination.

But increasing fog and unstable ice have made such research expeditions dangerous. And even if Atwood and his team are able to fly and succeed in locating a bear, they can only safely spend minutes on the ice instead of hours.

The condition of the sea ice has deteriorated so much that it’s been three years since Atwood and his colleagues have been able to physically examine a bear. When you’re studying polar bears, you need polar bears to study, is Atwood’s mantra.

“The implications are extensive,” he said. “We are losing the ability to track changes in the animals that might foreshadow adverse changes in the population.”

The seasonal window for field research on polar bears in Alaska has narrowed greatly over the last decade. For most of the 36 years USGS scientists have been studying polar bears on the southern Beaufort Sea, the prime time for the research stretched from the end of March to the middle of May, almost two full months when the ice was solid and smooth as a hockey rink. Now the sea ice is melting so quickly that Atwood and his team at the geological survey’s Alaska Science Center are lucky to have three weeks to conduct their research. And the ice is often pock-marked with soft spots—gaping expanses of water or areas with broken ice rubble the size of VW Beetles.

“The lengthening of open water season has caused significant changes in our ability to sample bears,” he said. “The environment in the Arctic is changing faster than the pace of improvements in research.”

More Questions, Fewer Answers

A warming climate is likely to have profound effects on polar bears.

A study last year predicted that some of the 19 polar bear subpopulations in the countries that ring the Arctic Circle could suffer devastating declines by the end of the century if climate change continues unchecked.

The less access researchers have to the animals, the less data are collected, and the more difficult it becomes to detect changes in the health of polar bear subpopulations over time, Atwood said.

In addition, there is less information that could give scientists a deeper understanding of how polar bear populations are responding to a variety of climate change stressors, including pathogens, pollutants and contaminants, as well as the effects of sea ice loss on the food chain the bears depend on.

The knowledge gained from such research helps federal and state regulatory agencies establish policies to manage polar bears under U.S. laws and international agreements. Atwood said that recognizing and monitoring health-based threats to polar bears has been identified as priority information needed by wildlife managers.

“The questions that management agencies are asking are increasing,” Atwood said. “The tools we have to answer those questions are decreasing.”

The polar bears studied by Atwood hang out on the ice covering the southern Beaufort Sea, part of the Arctic Ocean north of Alaska and the Northwest Territories, above the Arctic Circle. Researchers have documented the relationship between polar bears and climate change in the south Beaufort subpopulation, which declined by roughly 40 percent from 2005 to 2009.

The South Beaufort, where Atwood does his research, historically has been frozen over for most of the year, with some slivers of ice disappearing near the shores in late summer, usually August and September. But in recent years, the ice-free areas have greatly enlarged, and persisted for longer periods because of climate change. Over the last 25 years, the summer melt period has lengthened by as much as 82 percent, according to USGS studies, and sea ice cover has declined by more than half a million square miles.

The acceleration of sea ice melt results from a combination of warming Pacific Ocean water in the Bering Strait and record high surface air temperatures across the entire Arctic region, said Rick Thoman, a climate specialist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

“The water and air temperatures are conspiring to not only reduce the extent of ice in all seasons but also leading to thinning of the ice that remains,” he said.

The substantial decline in sea ice since 1979 is one of the most iconic indicators of climate change, according to the 2020 Arctic Report Card prepared by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

And the melting sea ice translates into a shrinking hunting ground for the seals that almost exclusively constitute the polar bears’ diet. The loss of ice has put the bears in the southern Beaufort Sea in the crosshairs of climate change. A study examining changes in sea ice, led by Atwood’s USGS colleague George Durner, concluded that “findings elevate concerns for the future status of SB (Southern Beaufort) polar bears as the transitional seasons of sea ice lengthen and the extent of optimal polar bear habitat during those seasons declines.”

Flight Time Cut in Half

Alaska is one of the fastest warming regions on Earth and is heating up faster than any other U.S. state, according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, published in 2018. By the middle of the century, the state’s daily maximum temperature could increase by between 4 and 8 degrees Fahrenheit.

The warmer Arctic waters have been linked to polar vortexes, unpredictable severe weather and heatwaves.

That’s on a global front. But in Atwood’s much smaller world the warming means more fog. And more fog means less flying time, because visibility drops to near zero in the dense, sheet-white vapor. By his count, the number of suitable flying days has dropped by more than half over the last 20 years because of fog.

Looking back at flight logs, Atwood said, he found that fog grounded the center’s research helicopters about 24 percent of the time between 2000 and 2009. That number increased to 46 percent between 2010 and 2015; and jumped to 56 percent over the last five years. It correlates with warming temperatures and disappearing sea ice.

“We are losing over half of the time we could be in the air surveying the bears,” he said.

Nothing More Than a Snapshot

The longstanding protocol for the biological assessments of polar bears calls for sedating the animals with a dart shot from a helicopter, and then waiting for the woozy bear to sprawl on the ice in an incapacitated daze. That procedure normally allowed Atwood and his team about an hour to safely examine the sedated bears, which can weigh as much as 1,500 pounds and stand 10 feet tall on their hind legs.

In that time, researchers could weigh the bear, take a tooth to determine the bear’s age, draw blood, take tissue and fecal samples; and attach a tracking device. Such extensive up-close examination has revealed an increased climate-related vulnerability to pathogens that can weaken a bear’s immune system, according to a 2017 study led by Atwood.

In earlier years, Atwood’s team would physically examine as many as 90 bears a year. “The information that we can obtain from a physical examination gives us the bear’s current state of health, a window into the bear’s future state of health, and the kinds of stressors that are in play with the bears,” Atwood said. “It tells a lot about the bear we have and gives us a good idea of what the bear population is facing.”

But for the researchers, the decline of sea ice has meant taking more risks while at the same time collecting less comprehensive data.

There is always a question whether weakened sea ice can withstand the weight of a 3,000-pound helicopter, its four-member crew and gear.

When the pilot spots ice topped by slushy water it’s a sign the ice is weak, Atwood said. Another clue is when the ice under the bear undulates as the animal moves around.

“When we see the ice flexing under the weight of a bear, obviously we can’t land on it,” Atwood said.

The loss of ice and the corresponding increase in open water is as dangerous for the polar bears as for the researchers. When a bear is shot with a dart, the anesthetizing effects can take up to five minutes. In that time the startled bear can cover hundreds of yards before collapsing, and may try to escape threats by diving into the water.

Atwood said his nightmare scenario is to have a darted bear find open water in its panicked flight, dive in, become incapacitated by the sedative and drown.

“There is far less opportunity to dart a bear now because there are no longer the long stretches of ice we once had where we could safely dart the bear,” he said. “The ice condition dictates what we can do.”

To compensate for the deteriorating conditions that limit physical examination of bears, Atwood and his team now employ a less exhaustive tactic for gathering biological data. When they encounter a bear on a safe stretch of ice, one of the researchers leans out of the helicopter and shoots the animal in the rump with a biopsy dart. Instead of putting the bear to sleep, the sharp dart takes a nip out of the bear’s skin. The sudden pinch surprises the bear, and when it bolts, the dart dislodges and falls onto the ice where it can be retrieved. The helicopter need only be on the ice for a few minutes.

This technique has been employed exclusively since 2019 because of poor ice conditions. Instead of vials of blood and sample jars full of the biological material that come from a physical examination, the dart provides a pencil eraser-sized amount of tissue. Such a small sample limits the amount of information that can be gleaned. Usually, it’s a lipid test that can provide the most information about the bear’s condition. Yet analysis of the biopsied tissue remains just a snapshot.

“It just doesn’t tell us as much as a full physical examination,” Atwood said.

Even this hit-and-run research is hampered by thinning sea ice. This year, Atwood’s team spotted 93 bears from the air. But the ice conditions allowed for darting only 60 of them. In 2019, the numbers were worse. The team sampled 24 of the 52 bears they encountered, letting the others go because of poor ice conditions. “Sometimes when we’re flying over ice that is rotten or surrounded by open water, we hope we don’t see a bear,” he said, “because there is nothing we can do.”

It Gets Even Worse

Polar bear biologist Kristin Laidre and her team perform their research more than 2,000 miles from where Atwood does his work. Yet they share the same apprehensions about the disappearing sea ice.

Laidre, a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Polar Science Center, studies polar bears on Baffin Bay, a vast expanse of ocean between northeastern Canada and Greenland that has seen recent declines in sea ice coverage. Although the sea ice retreat is not as dramatic on Baffin Bay as in the southern Beaufort, it has nevertheless forced Laidre and her team to adjust their strategy to account for the changing circumstances.

Like Atwood, Laidre fears that climate-induced changes in the Arctic are affecting polar bears, which depend on sea ice for their survival. And she shares the concern that disappearing and worsening sea ice conditions in the Arctic have combined to severely impede study of the bears, creating a void in information critical to conservation of the animals.

“We can’t rely on ice conditions now that we have had in the past to do our work,” she said.

Laidre, co-author of a recent study that details how declining sea ice is affecting the behavior, health and reproductive success of polar bears, said there has been a drop-off in research capability as the threat to scientists’ safety has increased.

“When you have unsafe conditions on the ice, it means our ability to collect data decreases,” she said. “The less information we collect affects the science we do.”

Laidre and her team are also increasingly dependent on the biopsy dart technique employed by Atwood and his colleagues. But unlike Atwood’s team, they don’t land the helicopter on the ice even for a few minutes to recover the biopsy dart. The copter hovers a few feet over the ice, just close enough to allow a crew member to hop down and grab the dart and then be hauled back into the aircraft.

Ryan Wilson, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Marine Mammals Management unit, described ice conditions in the Chukchi Sea that were even worse. Thousands of square miles of ice that once reliably covered the Chukchi, the northern buffer between Alaska and Siberia, has turned to open water or become too unstable to safely allow researcher access to the bears, Wilson said. It’s also unsafe for the biologists to fly over such vast expanses of open water with nowhere to land in an emergency.

Until 2017, Wilson said he and his team relied on physical examination of the bears, and between 2008 and 2017, they averaged examinations of 59 bears a year.

The deterioration of ice conditions was sudden and unexpected, he said, adding that he thought it would be a decade or more before the ice succumbed to the warming temperatures

“It’s striking,” he said. “What I thought would be 20 years happened in five years.”

Wilson and his team must now rely on four-year-old data in their files, information that is becoming staler by the year, for use in the agency’s 2019 Polar Bear Conservation Management Plan, which identifies the primary threats to polar bears and establishes high conservation strategies to promote the survival of the bears.

Although Wilson says his unit can still depend on that dated material to make decisions on polar bear management, those decisions are now incorporating more approximations to fill in the gaps left by the lack of up-to-date information.

“It’s going to become a bigger problem as time goes on,” he said. “If we are not actively updating our information, we might miss changes in the population that leads to mismanagement of the population.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611