Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

He’s being attacked for not having indicted former President Trump, for not having brought cases faster against witnesses who have defied the Jan. 6 committee, and for not having moved more aggressively against political figures for their supposed involvement in the Jan. 6 insurrection.

These criticisms speak to genuine frustrations with the slow pace of department action. They are also based on two flawed assumptions.

The first is the assumption that the evidence and equities would support prosecutions and, consequently, that the absence of criminal cases reveals weakness or hypercaution on the Justice Department’s part. This may be the case—but it may not. The absence of prosecutions could also reflect inadequacies in the evidence needed to bring cases.

The second problem is the confusion of what has not happened with what has not happened yet. The Justice Department can be very busy without making a lot of noise. The fact that indictments have not materialized so far does not mean they won’t appear tomorrow—or the day after.

But nearly a year into his tenure as attorney general, though much of the criticism of Garland has been unfair or at least premature, the attorney general does have something to answer for: his relative silence.

When Joe Biden nominated Garland to be attorney general, Garland spoke explicitly about Edward Levi, the former president of the University of Chicago and a noted legal scholar who served as attorney general under President Gerald Ford.

“Ed Levi and Griffin Bell, the first Attorneys General appointed after Watergate, had enunciated the norms that would ensure the department’s adherence to the rule of law,” Garland said in his acceptance speech:

Those policies included guaranteeing the independence of the department from partisan influence and law enforcement investigations, regulating communications with the White House, establishing guidelines for FBI investigations, ensuring respect for the professionalism of DOJ’s lawyers and agents, and setting our principles to guide the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. Those policies became part of the DNA of every career lawyer and agent.

Garland’s mission as attorney general, he stressed, would be “to reaffirm those policies as the principles upon which the department operates.” And he quoted another speech from Levi’s swearing in: “Nothing can more weaken the quality of life, or more imperil the realization of the goals we all hold dear, than our failure to make clear by words and deed that our law is not the instrument of partisan purpose.”

At Garland’s first speech to the Justice Department staff, he once again invoked Levi:

The only way we can succeed and retain the trust of the American people is to adhere to the norms that have become part of the DNA of every Justice Department employee since Edward Levi’s stint as the first post-Watergate Attorney General.

As I said at the announcement of my nomination, those norms require that like cases be treated alike. That there not be one rule for Democrats and another for Republicans; One rule for friends and another for foes; One rule for the powerful and another for the powerless; One rule for the rich and another for the poor; Or different rules depending upon one's race or ethnicity. At his swearing in, Attorney General Levi said: “If we are to have a government of laws and not of men, then it takes dedicated men and women to accomplish this through their zeal and determination, and also through fairness and impartiality. And I know that this Department always has had such dedicated men and women.” I, too, know that this Department has and always has had such dedicated people. I am honored to work with you once again. Together, we will show the American people by word and deed that the Department of Justice pursues equal justice and adheres to the rule of law.

Garland is not the only senior Justice Department official to refer to Levi’s legacy in describing the mission of the Justice Department under President Biden. At her confirmation hearing, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco declared that:

My first job in the Department was as counsel to Janet Reno, the first woman Attorney General. She hung a portrait of Attorney General Edward Levi in her conference room. It signaled her commitment to continuing Levi’s post-Watergate work to ensure the Department’s independence. It symbolized for me then, and is a reminder today, that the Department’s leaders have a duty to remember and reaffirm the values of the institution. When Attorney General Levi was asked what he thought the Department needed most after Watergate, he responded, “A soul.”

There’s a very good reason the senior Justice Department leadership keeps pointing to Ed Levi as a kind of founding father of the Justice Department they seek to restore. Indeed, we are sympathetic to the Justice Department’s need to revive the norms and practices of apolitical, independent, and professional justice that Levi did more than any other single person to create. Before Biden was even elected, in fact, one of us tweeted that Garland should be attorney general because he “is the closest thing the country has right now to an Ed Levi figure to restore the Justice Department.” Another of us wrote last spring an article in the Atlantic analyzing Levi’s legacy as a model for Garland.

Yet Garland seems to be ignoring one crucial aspect of Levi’s legacy: Ed Levi spoke a lot. Garland has been, in sharp contrast, largely invisible.

You don’t establish norms, or reestablish them, merely by modeling them. You establish them by articulating them, by talking about them, and by convincing people that they are the right way to behave. Levi understood this. His speeches and congressional testimonies as attorney general were numerous, highly substantive, and made arguments on behalf of the direction he wished to see the department go. They are a unique body of work among attorneys general, considered intellectually significant enough to have been collected and published as a volume by the University of Chicago Press.

Levi himself, we have learned, personally attached great importance to his speeches and testimonies. According to John Buckley, who served as one of Levi’s special assistants at the department and worked on some of the speeches, Levi wrote them himself—working on each with one of his special assistants.

Under Levi’s predecessor, William Saxbe, the public relations office would write the attorney general’s addresses. But Levi “believed in communication” and “labored over his speeches, testimony, [and] addresses,” Buckley said in a recent interview. He would “bang away at a manual typewriter” and edit the speeches with a fountain pen. “Those were his words.”

When he left office, his speeches were sufficiently significant to Levi that he bound them in a printed volume and gave a copy to each of the special assistants. It shows, Buckley says, “how much importance he attached to everything he wrote.”

Levi understood that certain Department of Justice issues were important enough that he needed to speak candidly and in detail about them to the public. For instance, the massive extent of the FBI’s “black bag jobs” and warrantless wiretapping of American citizens, sometimes for purposes of gathering political intelligence, had come to light through investigative journalism, congressional oversight, and some long overdue Department of Justice housecleaning started under Levi’s predecessor, Saxbe. J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI was also found to have gathered salacious material on a wide range of public figures, including members of Congress, and to have engaged in abusive and sometimes bizarre efforts to disrupt and discredit groups and individuals it considered radical. The revelations understandably lowered public opinion of the department’s integrity, and raised legitimate concerns about how deep the rot went and whether it was continuing.

Levi candidly owned up to mistakes: “[W]e all realize that in the past there have been grave abuses” by the FBI. And he named and described them. The “supervision by Attorneys General” of the FBI “has been sporadic, practically nonexistent, or ineffective.” He vowed to fix that and explained very specifically how he aimed to do it.

Levi also spoke repeatedly about programmatic efforts to remedy the sources of the problems. For example, he described to Congress and the public how he had tasked a Justice Department committee to draft detailed guidelines to rein in FBI misbehavior and increase oversight in sensitive areas, such as investigations that touched on political figures and political groups, the issuance of subpoenas to members of the press, and the use of informants. He repeatedly articulated the department’s legal views, along with policies designed to have warrantless wiretapping for foreign intelligence purposes narrowly circumscribed and subject to his personal oversight. He spoke publicly and specifically about the department’s work with Congress on a broad statute to bring under judicial oversight all domestic wiretapping for national security purposes. He described the outrageous FBI conduct toward Martin Luther King Jr. and described how he had tasked non-FBI officials to credibly and independently investigate it. Levi talked about how “important” it was that “the public get assurances that there are not such abuses” happening anymore. His goal was a “reconstruction” of the department and the public’s confidence in it, and a “reaffirmation of the effectiveness, independence and integrity of law enforcement agencies.”

Garland comes from a different school of thought on public engagement. During his long service as a judge, not only did he not give speeches or interviews describing his thinking and goals. He didn’t speak publicly at all. He didn’t speak at universities, as many judges do. He didn’t write law review articles. In his earlier stint at the Justice Department, he never cut much of a public figure either, though everyone understood that he was one of the most important people in the Main Justice building. He is steeped in the department’s culture of quietness, and he took that culture with him to the judiciary—where he was far more quiet than his contemporaries on the bench.

This quietness on Garland’s part is an expression of certain long-standing Justice Department norms. The department, according to this model, speaks almost entirely in court. It does not comment on pending investigative or prosecutorial matters outside of that. It does not behave politically—and shutting up is one very good way of avoiding saying things that could be construed in a political fashion. And the current moment has undoubtedly reinforced in Garland the wisdom of silence. His predecessor, William Barr, made all kinds of public comments that brought the department’s conduct into disrepute, speculating on what may have happened during the Russia investigation, for example. And before his firing, FBI Director James Comey was widely blasted for his comments about the Clinton email investigation during the last weeks before the 2016 election. So Garland may well have an instinct that the less he says the better.

The trouble is that, while silence by the attorney general reflects the department’s norms, it is a singularly bad means of establishing—or reestablishing—them.

In Garland’s defense, in deciding whether and how to speak publicly about past abuses and the current work of the department, he is facing problems that in some ways are tougher than those that confronted Levi. When Levi took office, the question about whether a former president who had potentially violated a number of criminal laws should be prosecuted had been resolved already: President Ford had granted a blanket pardon to Richard Nixon. Politically sensitive prosecutions of Watergate defendants had been handed off to a special prosecutor’s office. By contrast, questions about prosecuting Donald Trump and his associates must be faced by Garland himself and the departmental prosecutors working under him.

Levi’s credibility and freedom to operate were almost certainly enhanced by the facts that American politics, culture and media were less polarized in the 1970s than today, and that Levi’s criticisms of past abuses at the Department of Justice and White House often involved a current Republican administration criticizing a former Republican administration. Garland—unfortunately for him—must act and speak in a time of both fierce political tribalism and a social media environment that amplifies conflict, extreme positions and lies, all while laboring under the disability that criticisms from a Democratic attorney general of Republican predecessors will be discounted by many observers who will simply assume it to be politically motivated.

Despite our sympathy with the challenges facing Garland, his unwillingness to give the public any insight into his thinking seems ripe for criticism. It reflects a decision not to sell a vision—a vision that Garland clearly possesses and embodies—about how decisions should get made when the department is functioning properly.

There are a lot of such decisions before the department on which the public understanding and public debate would benefit from hearing the attorney general’s thinking. When Garland issued a policy strictly limiting contacts between the White House and the Justice Department—a policy very similar to ones that had been in place since the late 1970s—he could have given a speech explaining his goals and his choices. These policies seek to ensure that investigative and prosecutorial decisions about specific individuals are made based on law and fact, as evaluated by department lawyers and law enforcement professionals, not based on partisan or other improper considerations emanating from the White House. These norms were flagrantly abused during the Trump administration, and are in need of public reaffirmation. But Garland gave no such speech, leaving it to the press to report on the existence of the new policy and explain its significance to the public.

There are other instances in which more speaking would have been preferable. The department has reached plea agreements with a number of Jan. 6 defendants and has faced criticism, including from skeptical judges, for some of the relatively lenient sentences it has sought in those cases. What coordinating mechanisms have been set up to make sure that, as Garland himself put it, “like cases [are] treated alike”? And has there been any policy-level guidance about how different fact patterns should be charged?

Questions about when the department will act on criminal contempt referrals from Congress about witness refusals to comply with subpoenas from the Jan. 6 committee—such as that of Mark Meadows, Trump’s former chief of staff—are also fraught. It is, of course, correct for the department to avoid specific comments about individual pending matters. But this is not simply a collection of individual cases. It is a politically explosive and undeveloped area of law and practice that implicates fundamental separation of powers questions. The public would benefit from hearing reasoned discussion from the attorney general about how the department is approaching these referrals in broad terms. How is it balancing its institutional obligations to the legislature to bring contempt cases with its own interests in preserving a robust executive privilege?

Other areas would similarly benefit from public explanation. After the Sept. 11 attacks, the FBI and the Justice Department gave regular briefings on the investigation. There has been no such comparable effort to keep the public informed of the department’s progress in the Jan. 6 investigation—an investigation of similar scope and scale. Why not?

There is another, more internal question, about which Garland might turn the focus outward: What, if anything, is the department doing within its own ranks to try to rebuild norms and protect against potential misuse of law enforcement for partisan or personal ends in the future? Levi talked about this constantly; Garland has been quiet—except insofar as he has issued a new memorandum on White House contacts. But this question is critical, because it goes to the question of whether any of the changes he’s contemplating will outlast him or meaningfully constrain a less scrupulous attorney general.

Perhaps most importantly, what does the attorney general think—in broad terms, without commenting on any specific investigation—about when it is proper for the department to revisit a criminal investigation formally closed by a prior administration? This is a matter about which prior attorneys general have spoken. It is of acute concern right now with respect to the findings of the Mueller investigation, in particular Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s findings concerning potential obstruction of justice by Trump. Barr personally determined not to prosecute on the grounds that the evidence collected by Mueller was “not sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense”—a decision widely criticized at the time as politically motivated. On entering office, Garland quickly faced calls to take a fresh look at the Justice Department’s charging decision.

So far, there have been no outward indications that the department is reconsidering Barr’s choice. That doesn’t mean that nothing is happening—Mueller left the Justice Department with a rich evidentiary record to pore over without necessarily needing to conduct further investigation. But there is a new urgency to this issue, because the window is beginning to close on the Justice Department’s ability to bring charges against Trump over obstruction.

The statute of limitations for the various obstruction of justice statutes at issue is five years. Trump’s potential obstructive acts, as documented in the Mueller report, spanned from February 2017 through January 2019—so starting in February 2022, the statute of limitations will begin to kick in.

The below chart sets out the various instances of potential obstruction of justice identified by Mueller along with the expiration date for the statute of limitations. It’s an updated version of the obstruction heat map published by Lawfare after the Mueller report’s release, identifying how Mueller evaluates the strength of the three components of the obstruction statutes—an obstructive act, a nexus between the act and an official proceeding, and corrupt intent. This updated edition includes new information about Trump’s actions toward his confidante Roger Stone, which were redacted in the original copy of the Mueller report shared with the public and only revealed in July 2020. It also incorporates Trump’s pardons of Michael Flynn, Paul Manafort and Roger Stone—all of which he granted in 2020, and which arguably constitute potential obstructive acts that reset the clock on the statute of limitations.

As the chart shows, 2022 and 2023 will be crucial years for the Justice Department’s decision-making. The department will face its first deadline in February, concerning whether or not to charge Trump for his infamous conversation with then-FBI Director Comey over the bureau’s investigation into Trump’s former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. But as the heat map shows, the strongest potential obstruction charges against Trump—as Mueller identifies them—will start to expire in June and July 2022, five years after Trump sought to engineer Mueller’s firing and then to hamstring his investigation.

As far as we can tell, Garland has not spoken in public on the subject, leaving commentators to guess and prognosticate about the approach that the Justice Department might be taking. While it would obviously be improper for the department, or the attorney general, to speak to specific charges or defendants, it does not seem unreasonable to expect the attorney general to give some window into his thinking about the fundamental questions: Is the department deferring to Barr’s resolution of the matter? Has it, in fact, taken a look and determined that charges would be inappropriate? Or are questions arising from the Mueller report matters of active consideration?

These questions cut to the heart of public confidence in the Justice Department. A significant number of Americans are waiting for the department to hold Trump legally responsible for the many abuses for which he dodged accountability before. If the department doesn’t take such action, even if for very good reasons, these people will be disappointed and frustrated. Justice Department officials might brush off such reactions, except that this disappointment will inevitably undercut Garland’s efforts to “retain the trust of the American people.”

One of the lessons of Trump’s attacks on the integrity of the Justice Department is that most Americans don’t have a strong understanding of why independence in law enforcement matters or of the norms that, since Levi, have guided the department. Perhaps Garland’s view is that the risks of criminally investigating a former president, even in this time, are too great to take, too much of a breach of the department’s traditions. But he cannot expect people to understand that, or have a reasoned discussion of it, without first explaining it to them. And in the absence of an explanation, members of the public will come up with their own ideas—like weakness or lack of commitment to accountability. That silence undercuts the project to which Garland has committed himself.

If the goal of the Justice Department under Garland, as it was under Levi, is to rebuild the expectation that the department will act apolitically on investigative and prosecutorial matters, public communications matter. Public communications from the attorney general himself matter a lot. Garland is a scholarly man, a deeply thoughtful person. He is leaving one of his most important tools in the shed: As Levi said in one speech, “The basic tool for the lawyer is the word.”

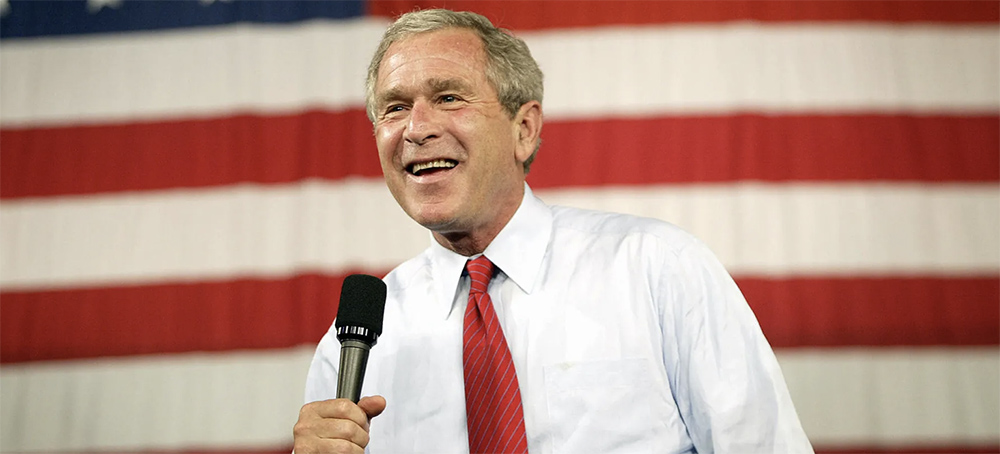

George W. Bush. (photo: Tim Sloan/Getty Images)

George W. Bush. (photo: Tim Sloan/Getty Images)

Here’s the question that comes to my mind as 2022 begins: If soon after the global war on terror began — with no special sources of inside information, nothing — I could see perfectly well that it was going to be a disaster, why couldn’t the people who mattered? It’s not like it was magic or something. It was obvious as hell.

And yet the crew running our government at the time and their neocon backers spoke of the modest terror groups then as part of a developing — it’s right there in the historical record — “World War IV.” As it happened, the 19 mostly Saudi al-Qaeda hijackers of 9/11 were anything but World War IViors. They were instead members of a small group that lucked out big-time in a truly murderous fashion. They were, however, not faintly equivalent to America’s opponents in World Wars I and II or, for that matter, the Cold War, which (thank god!) never quite became World War III.

That, in other words, was a fantasy of the first order, even if it was supported by a remarkable number of key backers of President George W. Bush and his top officials as they invaded Afghanistan and then Iraq. In doing so, they would, of course, create a war-making debacle, though at the time it was presented as a remarkable tale of all-American triumphalism. As I put it in 2003, thinking about the book I had written in the early 1990s titled The End of Victory Culture, “Given a system that eats itself for breakfast, the second coming of America’s victory culture should prove an ephemeral affair. I wouldn’t bet that a year from now, no less a decade from now, kids anywhere in America will be playing GIs and Iraqis, or Delta Force and Afghans in their backyards or streets. And maybe we should all thank our lucky stars for that.”

Still, that urge to be in World War IV did have its effect, domestically if nowhere else. After all, some two decades-plus after the 9/11 moment, we exist in a country in which the Pentagon and the “defense” industries associated with it are funded in a way that once would have been inconceivable. Meanwhile, we have a second Defense Department called the Department of Homeland Security and a global intelligence and surveillance network unparalleled in its expansiveness. As TomDispatch Managing Editor Nick Turse writes all too accurately today, we now live on a planet in which World War IV proved not just a pathetically losing effort, but a striking ongoing catastrophe. Still, as I read his piece, I couldn’t help thinking how painfully predictable it should have been that this country’s war on terror would turn into a war for terror. As he reports today, global terror groups have essentially doubled in number since 9/11.

Let me just quote myself one more time and then you can consider Washington’s all-too-mad twenty-first century of misplaced aggression with Nick. I wrote the following passage in April 2015 by which time all of this should have been beyond obvious to Americans of every stripe:

“And then, of course, there was our country’s endless string of failed wars, interventions, raids, assassination campaigns, and the like; there was, in short, the ‘global war on terror’ that George W. Bush launched to scour the planet of ‘terrorists,’ to (as they then liked to say) ‘drain the swamp’ in 80 countries. It was a ‘war’ that, with all its excesses, quickly morphed into a recruiting poster for the spread of extremist outfits…

“In the process, the president became first a torturer-in-chief and then an assassin-in-chief and, I’m sorry to tell you, few here even blinked. It’s been a nightmare of… hubris and madness, profits and horrors, inflated dreams of glory and the return, as if from an earlier century, of the warrior corporation and for-profit warfare on a staggering scale.”

Now, consider with Nick what it all adds up to as 2022 begins. Tom

-Tom Engelhardt, TomDispatch

The War on Terror Is a Success — for Terror

Terrorist Groups Have Doubled Since the Passage of the 2001 AUMF

Days earlier, Congress had authorized Bush “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determine[d] planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001 or harbored such organizations or persons.” By then, it was already evident, as Bush said in his address, that al-Qaeda was responsible for the attacks. But it was equally clear that he had no intention of conducting a limited campaign. “Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there,” he announced. “It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated.”

Congress had already assented to whatever the president saw fit to do. It had voted 420 to 1 in the House and 98 to 0 in the Senate to grant an Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) that would give him (and presidents to come) essentially a free hand to make war around the world.

“I believe that it’s broad enough for the president to have the authority to do all that he needs to do to deal with this terrorist attack and threat,” Senate Minority Leader Trent Lott (R-MS) said at the time. “I also think that it is tight enough that the constitutional requirements and limitations are protected.” That AUMF would, however, quickly become a blank check for boundless war.

In the two decades since, that 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force has been formally invoked to justify counterterrorism (CT) operations — including ground combat, airstrikes, detention, and the support of partner militaries — in 22 countries, according to a new report by Stephanie Savell of Brown University’s Costs of War Project. During that same time, the number of terrorist groups threatening Americans and American interests has, according to the U.S. State Department, more than doubled.

Under that AUMF, U.S. troops have conducted missions across four continents. The countries in question include some of little surprise like Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, and a few unexpected nations like Georgia and Kosovo. “In many cases the executive branch inadequately described the full scope of U.S. actions,” writes Savell, noting the regular invocation of vague language, pretzeled logic, and weak explanations. “In other cases, the executive branch reported on ‘support for CT operations,’ but did not acknowledge that troops were or could be involved in hostilities with militants.”

For nearly a year, the Biden administration has conducted a comprehensive evaluation of this country’s counterterrorism policies, while continuing to carry out airstrikes in at least four countries. The 2001 AUMF has, however, already been invoked by Biden to cover an unknown number of military missions in 12 countries: Afghanistan, Cuba, Djibouti, Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Niger, the Philippines, Somalia, and Yemen.

“A lot is being said about the Biden administration’s rethinking of U.S. counterterrorism strategy, and while it’s true that Biden has conducted substantially less drone strikes so far than his predecessors, which is a positive step,” Savell told TomDispatch, “his invocation of the 2001 AUMF in at least 12 countries indicates that the U.S. will continue its counterterrorism activities in many places. Basically, the U.S. post-9/11 wars continue, even though U.S. troops have formally left Afghanistan.”

AUMFing in Africa

“[W]e are entering into a long twilight struggle against terrorism,” said Representative David Obey (WI), the ranking Democrat on the House Appropriations Committee, on the day that the 2001 AUMF’s fraternal twin, a $40 billion emergency spending bill, was passed. “This bill is a down payment on the efforts of this country to undertake to find and punish those who committed this terrible act and those who supported them.”

If you want to buy a house, a 20% down payment has been the traditional ideal. To buy an endless war on terror in 2001, however, less than 1% was all you needed. Since that initial installment, war costs have increased to about $5.8 trillion.

“This is going to be a very nasty enterprise,” Obey continued. “This is going to be a long fight.” On both counts he was dead on. Twenty-plus years later, according to the Costs of War Project, close to one million people have been killed in direct violence during this country’s ongoing war on terror.

Over those two decades, that AUMF has also been invoked to justify detention operations at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba; efforts at a counterterrorism hub in the African nation of Djibouti to support attacks in Somalia and Yemen; and ground missions or air strikes in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. The authorization has also been called on to justify “support” for partner armed forces in 13 countries. The line between “support” and combat can, however, be so thin as to be functionally nonexistent.

In October 2017, after the Islamic State ambushed U.S. troops in Niger — one of the 13 AUMF “support” nations — killing four American soldiers and wounding two others, U.S. Africa Command claimed that those troops were merely providing “advice and assistance” to local counterparts. Later, it was revealed that they had been working with a Nigerien force under the umbrella of Operation Juniper Shield, a wide-ranging counterterrorism effort in northwest Africa. Until bad weather prevented it, in fact, they were slated to support another group of American commandos trying to kill or capture Islamic State leader Doundoun Cheffou as part of an effort known as Obsidian Nomad II.

Obsidian Nomad is, in fact, a 127e program — named for the budgetary authority (section 127e of title 10 of the U.S. Code) that allows Special Operations forces to use select local troops as surrogates in counterterrorism missions. Run either by Joint Special Operations Command, the secretive organization that controls the Navy’s SEAL Team 6, the Army’s Delta Force, and other elite special mission units, or by more generic “theater special operations forces,” its special operators have accompanied local commandos into the field across the African continent in operations indistinguishable from combat.

The U.S. military, for instance, ran a similar 127e counterterrorism effort, codenamed Obsidian Mosaic, in neighboring Mali. As Savell notes, no administration has ever actually cited the 2001 AUMF when it comes to Mali, but both Trump and Biden referred to providing “CT support to African and European partners” in that region. Meanwhile, Savell also notes, investigative journalists “revealed incidents in which U.S. forces engaged not just in support activities in Mali, but in active hostilities in 2015, 2017, and 2018, as well as imminent hostilities via the 127e program in 2019.” And Mali was only one of 13 African nations where U.S. troops saw combat between 2013 and 2017, according to retired Army Brigadier General Don Bolduc, who served at Africa Command and then headed Special Operations Command Africa during those years.

In 2017, the Intercept exposed the torture of prisoners at a Cameroonian military base that was used by U.S. personnel and private contractors for training missions and drone surveillance. That same year, Cameroon was cited for the first time under the 2001 AUMF as part of an effort to “support CT operations.” It was, according to Bolduc, yet another nation where U.S. troops saw combat.

American forces also fought in Kenya at around the same time, said Bolduc, even taking casualties. That country has, in fact, been cited under the AUMF during the Bush, Trump, and Biden administrations. While Biden and Trump acknowledged U.S. troop “deployments” in Kenya in the years from 2017 to 2021 to “support CT operations,” Savell notes that neither made “reference to imminent hostilities through an active 127e program beginning at least in 2017, nor to a combat incident in January 2020, when al Shabaab militants attacked a U.S. military base in Manda Bay, Kenya, and killed three Americans, one Army soldier and two Pentagon contractors.”

In addition to cataloging the ways in which that 2001 AUMF has been used, Savell’s report sheds light on glaring inconsistencies in the justifications for doing so, as well as in which nations the AUMF has been invoked and why. Few war-on-terror watchers would, for example, be shocked to see Libya on the list of countries where the authorization was used to justify air strikes or ground operations. They might, however, be surprised by the dates cited, as it was only invoked to cover military operations in 2013, and then from 2015 to 2019.

In 2011, however, during Operation Odyssey Dawn and the NATO mission that succeeded it, Operation Unified Protector (OUP), the U.S. military and eight other air forces flew sorties against the military of then-Libyan autocrat Muammar Gaddafi, leading to his death and the end of his regime. Altogether, NATO reportedly conducted around 9,700 strike sorties and dropped more than 7,700 precision-guided munitions.

Between March and October of 2011, in fact, U.S. drones flying from Italy regularly stalked the skies above Libya. “Our Predators shot 243 Hellfire missiles in the six months of OUP, over 20 percent of the total of all Hellfires expended in the 14 years of the system’s deployment,” retired Lieutenant Colonel Gary Peppers, the commander of the 324th Expeditionary Reconnaissance Squadron during Operation Unified Protector, told the Intercept in 2018. Despite those hundreds of drone strikes, not to mention attacks by manned aircraft, the Obama administration argued, as Savell notes, that the attacks did not constitute “hostilities” and so did not require AUMF citation.

The War for Terror?

In the wake of 9/11, 90% of Americans were braying for war. Representative Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) was one of them. “[W]e must prosecute the war that has been thrust upon us with resolve, with fortitude, with unity, until the evil terrorist groups that are waging war against our country are eradicated from the face of the Earth,” he said. More than 20 years later, al-Qaeda still exists, its affiliates have multiplied, and harsher and deadlier ideological successors have emerged on multiple continents.

As both political parties rushed the United States into a “forever war” that globalized the death and suffering al-Qaeda meted out on 9/11, only Representative Barbara Lee (D-CA) stood up to urge restraint. “Our country is in a state of mourning,” she explained. “Some of us must say, ‘Let’s step back for a moment, let’s just pause, just for a minute, and think through the implications of our actions today, so that this does not spiral out of control.’”

While the United States was defeated in Afghanistan last year, the war on terror continues to spiral elsewhere around world. Last month, in fact, President Biden informed Congress that the U.S. military “continues to work with partners around the globe, with a particular focus” on Africa and the Middle East, and “has deployed forces to conduct counterterrorism operations and to advise, assist, and accompany security forces of select foreign partners on counterterrorism operations.”

In his letter, Biden acknowledged that troops continue detention operations at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and support counterterrorism operations by the armed forces of the Philippines. He also assured Congress and the American people that the United States “remains postured to address threats” in Afghanistan; continues its ground missions and air strikes in Iraq and Syria; has forces “deployed to Yemen to conduct operations against al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and ISIS”; others in Turkey “to support Counter-ISIS operations”; around 90 troops deployed to Lebanon “to enhance the government’s counterterrorism capabilities”; and has sent more than 2,100 troops to “the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to protect United States forces and interests in the region against hostile action by Iran and Iran-backed groups,” as well as approximately 3,150 personnel to Jordan “to support Counter-ISIS operations, to enhance Jordan’s security, and to promote regional stability.”

In Africa, Biden noted, U.S. forces “based outside Somalia continue to counter the terrorist threat posed by ISIS and al-Shabaab, an associated force of al Qaeda” through air strikes and assistance to Somali partners and are deployed to Kenya to support counterterrorism operations. They also remain deployed in Djibouti “for purposes of staging for counterterrorism and counter-piracy operations,” while in the Lake Chad Basin and the Sahel, U.S. troops “conduct airborne intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance operations” and advise, assist, and accompany local forces on counterterrorism missions.

Just days after Biden sent that letter to Congress, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced the release of an annual counterterrorism report that also served as a useful assessment of more than 20 years of AUMF-fueled counterterror operations. Blinken pointed to the “spread of ISIS branches and networks and al-Qaeda affiliates, particularly in Africa,” while noting that “the number of terrorist attacks and the overall number of fatalities resulting from those attacks increased by more than 10 percent in 2020 compared with 2019.” The report, itself, was even bleaker. It noted that “ISIS-affiliated groups increased the volume and lethality of their attacks across West Africa, the Sahel, the Lake Chad Basin, and northern Mozambique,” while al-Qaeda “further bolstered its presence” in the Middle East and Africa. The “terrorism threat,” it added, “has become more geographically dispersed in regions around the world” while “terrorist groups remained a persistent and pervasive threat worldwide.” Worse than any qualitative assessment, however, was the quantitative report card that it offered.

The State Department had counted 32 foreign terrorist organizations scattered around the world when the 2001 AUMF was passed.. Twenty years of war, around six trillion dollars, and nearly one million corpses later, the number of terrorist groups, according to that congressionally mandated report, stands at 69.

With the passage of that AUMF, George W. Bush declared that America’s war would “not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated.” Yet after 20 years, four presidents, and invocations of the AUMF in 22 countries, the number of terrorist groups that “threaten the security of U.S. nationals or the national security” has more than doubled.

“The 2001 AUMF is like a blank check that U.S. presidents have used to conduct military violence in an ever-expanding number of operations in any number of places, without adequate oversight from Congress. But it’s also just the tip of the iceberg,” Savell told TomDispatch. “To truly end U.S. war violence in the name of counterterrorism, repealing the 2001 AUMF is the first step, but much more needs to be done to push for government accountability on more secretive authorities and military programs.”

When Congress gave Bush that blank check — now worth $5.8 trillion and counting — he said that the outcome of the war on terror was already “certain.” Twenty years later, it’s a certainty that the president and Congress, Representative Barbara Lee aside, had it all wrong.

As 2022 begins, the Biden administration has an opportunity to end a decades-long mistake by backing efforts to replace, sunset, or repeal that 2001 AUMF — or Congress could step up and do so on its own. Until then, however, that same blank check remains in effect, while the tab for the war on terror, as well as its AUMF-fueled toll in human lives, continues to rise.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

January 6, 2021. (photo: Brent Stirton/Getty Images)

January 6, 2021. (photo: Brent Stirton/Getty Images)

ALSO SEE: Capitol Rioter Admits False Statements to FBI,

but Prosecutors Haven't Charged Him With a Felony

If anyone there on Jan. 6 assumes they’re safe from prosecution because a year has passed, they’re wrong.

In fact, the feds are still actively searching for hundreds of known rioters.

FBI Director Chris Wray has described the Jan. 6 attack as an act of domestic terrorism, which led directly or indirectly to five deaths, roughly 140 injured law enforcement officers, and $1.5 million worth of damage to the Capitol building. Among the alleged perpetrators bagged so far: violent extremists from 45 states and the District of Columbia; avowed neo-Nazis, active-duty and retired members of the military; off-duty cops; loosely affiliated groups of far-right gang members like the Proud Boys; QAnon adherents; and at least one Olympic gold medalist.

Immediately after the siege, the Department of Justice launched an investigation it called “one of the largest in American history.” Steven D’Antuono, assistant director in charge of the FBI’s Washington Field Office, said at the time the bureau would “leave no stone unturned until we locate and apprehend anyone who participated in the violence.” The scope of the task at hand was described by one defense attorney as being more complex than untangling the 9/11 attacks.

So far, more than 700 people have been charged for their alleged involvement in the riot, FBI spokesperson Samantha Shero told The Daily Beast. All face federal rather than state or local charges. They have ranged from trespassing to conspiracy against the United States.

Authorities are still looking for the person they say planted pipe bombs near the offices of the Democratic National Committee on the night of Jan. 5, and have not slowed in their efforts. Meanwhile, two-thirds of Republicans continue to believe Donald Trump’s so-called Big Lie that the election was somehow stolen from him, and nearly 40 percent of that group think violence is the only way to “save” the country, according to recent polling.

But if anyone there that day assumes they’re safe from prosecution because 12 months have passed, they’re wrong. Because not only are the feds hunting for them, a digital army of volunteer investigators are also on the case—and the ad hoc crew of citizen sleuths have already collected a dozen or so scalps.

Somewhat infamously, only 14 people were arrested by the U.S. Capitol Police on Jan. 6: 10 for unlawful entry; two for assaulting a police officer; and two for weapons possession. But the cascade of arrests, charges, and—in recent months—convictions and sentences has not stopped since then. Among other more recent highlights, in October, a Capitol Police officer was charged with obstruction of justice for telling one of the alleged rioters to delete incriminating evidence of his actions that day he had posted on social media.

And the search for violent thugs who preyed on the seat of American democracy goes on. According to FBI estimates, as of Dec. 30 there were “around 250 individuals” pictured on the agency’s Jan. 6 wanted list and accused of having assaulted law enforcement officers that day who have not yet been identified or arrested, according to Shero. An additional 100 suspects are wanted for committing other “violent acts” on Capitol grounds. The bureau says it is also looking to ID 16 suspects seen on video assaulting federal officers that day, and two suspects who were filmed assaulting members of the media.

The FBI declined to share details about any rioters agents have identified but have not yet arrested. However, the bureau has publicly pegged the total number of people involved in the Capitol attack that day at around 2,000.

In a modern twist, the feds have received an assist from civilians working to identify countless unnamed Capitol rioters caught on camera during the rampage. Decentralized online groups devoted to exposing rioters have some 2,500 names on their lists, which include people spotted outside the Capitol but who never entered the building. The work of these private “sedition hunters” has been cited in court documents at least a dozen times to date, and the bureau has received more than 250,000 tips from the public at large.

“While it may appear that no overt law enforcement action is being taken on some tips that have been submitted, tipsters should rest assured that the FBI is working diligently behind the scenes to follow all investigative leads to verify tips from the public and bring these criminals to justice,” Shero said.

Of the 2,000 or so people who were there, there are at least 1,000 who “crossed the threshold in terms of going into the Capitol and being hit [with] federal crimes,” according to Seamus Hughes, deputy director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, who called the number a “conservative estimate.”

“The law enforcement agencies that I’m talking to are still working through cases, and facial recognition, and still identifying folks as we speak,” Hughes, who is also a Daily Beast contributor, said in an interview.

Six days after the Capitol siege, D’Antuono of the FBI said in a statement that the bureau had to “separate the aspirational from the intentional, and determine which of the individuals saying despicable things on the internet are just practicing keyboard bravado or they actually have the intent to do harm.”

As of August, this worked out to about three arrests a day, according to the Department of Justice.

Hughes explained that the Department of Justice was “trying to clear the decks as best they can” of lower-level cases by offering plea deals that most defendants would agree to accept. This, suggested Hughes, allows investigators and prosecutors to focus their resources on bigger fish who were involved, like members of the Oath Keepers, a right-wing anti-government alliance that purports to consist of current or former police officers and military members and is classified as an extremist group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

“They’re not slowing down by any means,” Hughes added. “They’re still working weekends. They still have agents pulled onto these cases that were pulled off of white-collar crime, ISIS cases, they’re all now on the January 6 investigation. They haven’t ramped down their resources on the investigation yet. And it’s not clear to me whether they will in the near future. This is to say that if individuals were there in the Capitol and think that enough time has passed, [that] they may have dodged a bullet, I would say the FBI is still looking for them.”

At ground level, the investigation is playing out exactly as it should be, retired FBI Supervisory Special Agent Dennis Franks told The Daily Beast.

The FBI’s Washington Field Office is heading up the investigation, with an assistant director overseeing it. There are new leads going out every day, to every division across the country, and agents are using “everything at their disposal” to crack each case, according to Franks, citing personal conversations with active and former agents.

“You get a lot of information that doesn’t pan out, but it still has to be pursued—you have to find if there’s something there or not,” said Franks. “They’re not going to set up a deadline that this has to be done by. They’ll just carry it out, follow it as long as it takes.”

Agents are tracking Jan. 6-ers down by weeding through a massive tranche of tips, utilizing facial recognition software, and subpoenaing records from internet and phone providers to obtain names of people who were in and around the Capitol building during the riot, according to court filings.

But in addition to providing tips and IDing suspected Capitol rioters the FBI may not have yet, citizen sleuths can trawl social media in ways that are generally off-limits for the feds.

“We’re not allowed to... just sit and monitor social media and look at one person’s posts… just in case,” FBI Director Christopher Wray told the House Judiciary Committee in June, citing the bureau’s civil liberties guidelines.

The work of citizen sleuths also provides a novel way for agents to keep their investigative techniques as close to the vest as possible, using “parallel reconstruction” in probable-cause affidavits when they can. Instead of explicitly including the geofencing or facial recognition tools they used, investigators can instead point to a tip from the public as the clue they needed for a positive ID.

One of the biggest questions pertaining to Jan. 6 has been the issue of coordination. A conspiracy, in legal terms, can be made up of just two people, said Franks, who worked as an assistant district attorney in North Carolina before becoming an FBI agent.

Many of the organized groups seen attacking the Capitol coalesced on the internet, with Facebook largely acting as “the big unifier,” according to Tech Transparency Project director Katie Paul, who specializes in tracking criminal activity online.

The algorithms social networks use to keep people engaged mean they’re not passive third-party platforms, but are actively facilitating this kind of organizing, Paul told The Daily Beast.

“I think as you have this older population growing increasingly digitally literate, with Facebook specifically, you run into a future where… the algorithm creates these alternative realities for people and makes it virtually impossible for them to break out of that loop of extremism,” said Paul. “In fact, the platform’s hand-feeding them more extremist content each time they click on something.”

Facebook has regularly disputed the charge that their algorithm fuels extremism, although whistleblower Frances Haugen told the U.S. Senate that the company knows its platform sows political division but has not done anything about it in choosing “profits over safety.”

Drew Pusateri, a spokesman for Facebook parent company Meta, told The Daily Beast that the “responsibility for the violence that occurred on January 6 lies with those who attacked our Capitol and those who encouraged them. We took steps to limit content that sought to delegitimize the election, including labeling candidates’ posts with the latest vote count after Mr. Trump prematurely declared victory, pausing new political advertising, and removing the original #StopTheSteal Group in November.”

After the violence at the Capitol on Jan. 6, Facebook “removed content with the phrase ‘stop the steal’ under our Coordinating Harm policy and suspended Trump from our platforms,” Pusateri said.

But one of the most striking revelations Paul said she has experienced while investigating the Capitol riot has been “how people that are affiliated with law enforcement can get looped into these kinds of worlds.”

Not only have Paul and her team spotted active and former military sharing extremist content online, they also identified a retired Capitol Police lieutenant who was “essentially cheering on the insurrection” on Facebook.

“There’s a really long way to go, especially when we know that now the military is considering even ‘liking’ or following certain extremist content as dismissible,” Paul said. (The Pentagon has identified “reading, following, and liking extremist material and content in social media forums and platforms” as potentially disqualifying, but it is still something of a “gray area,” according to an April 2021 memorandum from Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III.)

Another important area of focus in the aftermath of Jan. 6 has been to identify any elected officials who may have played an active role that day. The House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol, which was formed by Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat, is currently looking into any involvement or coordination in the run-up by elected officials. It has already subpoenaed a slew of politicians and members of Trumpworld, and will continue to do so in the coming weeks and months. The body does not itself have the authority to bring criminal charges against any of its targets, but can refer cases it recommends for prosecution to the Department of Justice, which will make the ultimate determination.

Public Wise, a Washington, D.C. watchdog group, is getting ready to launch its “Insurrection Index,” a searchable online database (now in beta form) of individuals and organizations linked in some way to the Capitol riot—not only those charged with crimes, but also those seen at associated rallies and events on the day of Jan. 6. Most importantly, according to Public Wise executive director Christina Baal-Owens, the index will identify those holding public office, or those now running for office, who were in any way involved with the events of Jan. 6 or any activities surrounding them, including helping to push Trump’s “Big Lie.” (The organization has so far identified nine Jan. 6-ers who have won local and state elections in the 12 months since.)

“As someone who has worked in politics for many years, I do believe that politics has a strangely short memory,” Baal-Owens told The Daily Beast. “And I share the fear that within a cycle or two, even things as egregious as putting a gallows up outside of the Capitol could be forgotten.”

Public Wise is now working to make the Insurrection Index “actionable,” which Baal-Owens hopes will keep insurrectionists and the Jan. 6-adjacent out of office or other positions of public trust.

As for those who are already there, it may be too late in many instances.

In October, Rolling Stone reported that multiple congressional Republicans were “intimately involved” in planning Trump’s so-called Stop the Steal rally that immediately preceded the violence at the Capitol. But prosecuting U.S. officials presents a Sisyphean task that few decision-makers at the Justice Department would be likely to take on, according to Dennis Franks.

“If something comes up, certainly I think they’ll look at it,” he said. “But unless there is overwhelming evidence that they were directly involved or somehow they can show that their words did incite, it’s going to be very difficult to bring charges against members of Congress, given all the political considerations—it would have to be a smoking gun type of thing.”

India Walton. (photo: Lindsay Dedario/Reuters)

India Walton. (photo: Lindsay Dedario/Reuters)

“I am excited to be added to the RootsAction team. I see this as a unique opportunity to continue to fight for racial, economic, and climate justice on a broader scale,” Walton said.

Norman Solomon, RootsAction’s national director, said: “India Walton has shown that it’s possible and essential to combine visionary goals with effective grassroots organizing. With our country in desperate need of genuine progressive change, her leadership will be of enormous value nationwide.”

RootsAction was founded in 2011 by two longtime progressive advocates and journalists, Norman Solomon and Jeff Cohen, and has grown to include an email list of more than 1 million supporters. The activist organization is dedicated to galvanizing people who are committed to economic fairness, equal rights, environmental protection -- and defunding endless wars. RootsAction mobilizes on a range of key issues no matter whether Democrats or Republicans are in power.

An annual festival for a growing community of Guatemalan immigrants in New Bedford, Massachusetts, took place in September 2021. Members of the musical group, Soñando por Mañana, which means Dreaming for Tomorrow in Spanish, sang both the U.S. and Guatemalan national anthems. (photo: Jodi Hilton/Marshall Project)

An annual festival for a growing community of Guatemalan immigrants in New Bedford, Massachusetts, took place in September 2021. Members of the musical group, Soñando por Mañana, which means Dreaming for Tomorrow in Spanish, sang both the U.S. and Guatemalan national anthems. (photo: Jodi Hilton/Marshall Project)

Pandemic relief programs have helped millions of families get through the economic shocks of COVID-19, but undocumented immigrants — many of whom are essential workers — have been largely shut out of such federal aid. Those undocumented workers who have received limited assistance are now losing the pandemic aid they had only started receiving in August through the Biden administration’s expanded child tax credit program, which expired and is being blocked from further implementation into Build Back Better legislation. “These families, in spite of the fact that they were essential workers, endured this really punishing income gap,” says journalist Julia Preston, who reported on an undocumented immigrant community in New Bedford, Massachusetts, who sustain the United States’ largest commercial fishing port. Preston and Ariel Goodman wrote the article “Essential But Excluded” for The Marshall Project and say the difference in income amounts on average to almost $35,000.

We turn now to look at how this is playing out in one city in New England, New Bedford, Massachusetts, the largest commercial fishing port on the Eastern Seaboard. Immigrants, many undocumented, play key roles in the fishing industry and have worked throughout the pandemic despite the risks. However, many of these same immigrant workers have been shut out of pandemic aid, and so have their children, many of whom were born in the United States and are U.S. citizens.

The Marshall Project recently published a detailed investigation into the crisis facing families in New Bedford. The article is headlined “Essential but Excluded.” It was written by Julia Preston and Ariel Goodman, who join us now. Julia Preston is a contributing writer at The Marshall Project, former reporter at The New York Times, where she covered immigration for years and was part of a Pulitzer Prize-winning team in 1998. Ariel Goodman is the Tow audience engagement fellow at The Marshall Project. She’s also my niece.

Julia Preston, let’s begin with you. This is a deep piece, because it really puts a face on who suffers in this country, not only when the child tax credit ends, as it has, but for those who missed out on it completely. If you can lay out what you found in New Bedford and who these essential but excluded immigrants are?

JULIA PRESTON: Well, the community that we found in New Bedford are mostly immigrants from Guatemala, from the highlands of Guatemala. They are — it’s a community of Mayan K’iche’-speaking Indigenous people, and they work in the plants across the waterfront, where they pack seafood there — scallops, haddock — the food that was actually keeping Americans fed during the pandemic when so many people had to stay home. It was not an option for these workers to stay home, however, because many of them are undocumented, and they were not eligible for unemployment insurance of any kind. They were not eligible for some of the enhanced stimulus payments that came from — as a result of COVID, starting under President Trump and including under President Biden, and they were not eligible for certain kinds of tax credits. But, actually, because they are taxpayers, they were eligible for the enhanced tax credit, child tax credit, that President Biden made available through the Rescue Act last March.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Julia, the estimates, as I understand it, are that as many as 74% of undocumented immigrants in the United States are considered essential workers, far higher percentage than about the 65% in the native-born labor force. What has been the difference between how the Trump administration dealt with pandemic relief and the Biden administration, from what you’ve been able to tell?

JULIA PRESTON: Well, the Trump administration worked hard to make COVID relief unavailable to most undocumented workers. And there was a revision in terms of stimulus relief at the end of last year so that at least the families that had American citizen children and American citizen spouses, if there was an undocumented taxpayer in that family, those families did become eligible, finally, for some forms of COVID relief.

But, in general, what we found in New Bedford was that in spite of the fact that these undocumented immigrants were working, they were paying their taxes, and most of their kids were American citizen children. The difference over the length of the pandemic in terms of their income from federal COVID aid and the income of a family that had American citizen taxpayers, that difference was almost $35,000. To put that in perspective, a family of seafood packing workers doesn’t make that much money in an entire year under normal circumstances, and certainly not during the pandemic. So, these families, in spite of the fact that they were essential workers, endured this really punishing income gap with American families who were able to stay home and collect unemployment insurance and protect themselves during the pandemic.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And do you have any sense of how many states, if any, have been able to plug the gap somewhat by creating state-level essential workers funds or pandemic relief funds? I know there is one in New Jersey that was passed recently for excluded workers who might be undocumented. Is this a trend across the country, or is it just a few of the blue states?

JULIA PRESTON: Well, I think New York was also one of the states that did that, but that did not happen in Massachusetts, where we were reporting. What did happen in Massachusetts and across the country was — in terms of federal aid, was the availability to undocumented workers who were paying their taxes, and who were being paid in paychecks, of the child tax credit. This child tax credit, that is the center of the debate right now in Washington, did become available because of some changes that the Biden administration made last March to the terms of the child tax credit. And so, these long-suffering families, who had basically endured the entire pandemic without any form of federal assistance, or very limited federal assistance, in August, they started to receive direct payments into their bank accounts of $300 or $360 per child, if the child was an American citizen.

And we really got a view of how significant these payments are. For many of these families, this was the difference between having food on the table for their children and not. It was the difference between being able to pay the rent and continue to be housed and not be able to do that. It was the difference between being able to pay a mobile phone bill and a Wi-Fi bill. And these are not luxuries anymore. These were fundamental, life-saving tools, and during the pandemic, these were necessary tools for their kids to go to school.

And again, we’re talking about kids who are American citizens. They were born in this country. They go to school in our communities. They’re just like our kids, our American citizen kids. And so, what you had an opportunity to see in New Bedford at the end of the process last year was the enormous positive impact that these child tax credit payments can have on the lowest-income families, and especially on these families that have worked so hard — despite their immigration status, despite the struggles that they face in the immigration system, they worked so hard to put food on our tables during the pandemic.

AMY GOODMAN: And despite the fact that many of them pay taxes.

JULIA PRESTON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, I think the power of your piece is some of the people the two of you interviewed for this piece. Let’s turn to Lucia Mateo Pérez.

LUCIA MATEO PÉREZ: [translated] I am a dreamer. I don’t just want a car. My dreams reach further than that. I never had a childhood playing with toys. I never had that because we live in extreme poverty. We are deeply discriminated against in our country for the fact that we are women and for the fact that we have brown skin, but, more than anything, for the fact that we are Indigenous.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Lucia Mateo Pérez. Her photograph is the top photograph on the piece. Ariel, if you can talk about who some of these people are? This is the flesh, the stories, the beauty of this piece.

ARIEL GOODMAN: Yeah. So, to give a sense of who people are and the kind of work that they were doing, these are people who are waking up long before the sunrise, who are going and working in cold packing plants for nine hours a day. I talked to a woman who stands on a packing line every day, you know, jackets on under her robes, picking out the imperfections of the day’s catch with tweezers. These are people who, as Julia mentioned, endured extreme hardship through the pandemic and, you know, through the continuation of the pandemic that we’re all living right now. We spoke to mothers who were forced to eat cereal for days, when their hours were cut, in order to give better food to their children.

These were stories of survival, of people who, left out of almost all federal aid, had to lean on one another, people who converted cramped apartment kitchens into food businesses that they sold to their neighbors. I spoke to someone who is a subsistence farmer in his country. And when he lost his work, he did what he knew how to do, which was grow vegetables and sell them in town. So, these are stories of survival. These are stories of deep inequality, as Julie mentioned.

But I think that the larger point here is that these are American stories. This is the story not only of how this one immigrant community survived, like so many immigrant communities are surviving by relying on one another throughout the country, but it’s the story of how food arrived on all of our tables. It’s the story of the people whose hands the cod, the flounder, the scallops passed through and were packaged by before it arrived on your table. So, yeah, I think that that’s kind of what it represents, is sort of this larger question that’s being addressed in Build Back Better, which is: How is our country going to treat the workers that their labor is essential to its function?

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, New Bedford is the scallop capital of the world. In the case of Lucia, Lucia Mateo Pérez, we know her name in your story because she is now documented. Ariel, if you can talk about that?

ARIEL GOODMAN: Yes. So, Lucia is a person who was granted asylum. She came here in 2015. She was a seafood worker for the first year of her time in the United States. But Lucia is also a person that we spoke to because she was a survivor of a fire that happened last year, a fire that displaced 40 families, the majority of whom were seafood workers. And we chose to focus on this fire because we were trying to understand, you know, going into two years of the pandemic, what are the effects of not having received aid on people. How are we seeing that not only at the beginning of the pandemic, when we heard so many stories of what it was to live for so many of these communities in the epicenter of the pandemic, but what does it mean now two years in?

And what we found were stories like the one that Lucia’s family went through, stories of deep housing insecurity, of families who had to begin living together. The place where they lived that went up in flames, two people died in this fire. According to residents, fire alarms did not go off. And now, after that, they’ve now been displaced and are — you know, the few belongings that they did have, that they were able to accumulate over years of hard work, things like couches, something to sort of create a space for their family, are all gone, and they’re forced to live in a place that is even smaller. And, you know, we’re all learning about what that means and what they’re reckoning with now with Omicron on the horizon.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Diego, the son of an out-of-work seafood worker in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

DIEGO: It’s pretty hard for me. He can’t, like, buy us some school supplies, something like that, shoes, clothes. How is he going to work? How is he going to get money for our food and stuff like that?

AMY GOODMAN: And this is T.S., an undocumented seafood worker, speaking to The Marshall Project.

T.S.: [translated] We are not free in this country. They can come and take me at any time, and my children would stay here suffering. If I had a social, it might be different, but since I don’t, I am in the hands of God.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Julia Preston, as we hear these voices, we’re hearing the voices of immigrants from the highlands of Guatemala, well known for the persecution that whole population faced for decades, after the U.S. intervened and supported the military dictatorships there. If you can relate that to current immigration reform today and what’s not happening in this country, as they face depression there and then come to the United States and face this hardship here?

JULIA PRESTON: Well, I mean, especially for this community that we saw in New Bedford, the lack of immigration status has just become, during the pandemic, incredibly punishing. And you really see how the failure of Congress to advance some kind of broader immigration reform to just bring these people into a basic legal status is really not only at this point affecting workers who were so essential to keeping us fed and keeping — you know, providing home care — they did so much work for us during the pandemic for the rest, the larger community — the failure of Congress to pass immigration reform has really — it’s not only just punishing those people, but now we have generations of American citizen kids who are growing up, and because of the failure of Congress to correct this legal status for these folks, now their American citizen kids, who were born in this country — they’re not going anywhere, they’re going to grow up here — are being punished, as well.

And so, I think that one of the points that we should see is that even while the immigration — the explicit immigration provisions in the Build Back Better bill that President Biden has put forward and that is under debate in the Senate, those have run into tremendous procedural hurdles, and it’s really not clear what’s going to happen with those provisions, the child tax credit provisions are also very important for undocumented people, to give them some kind of basic support going forward as we struggle again with another chapter of the pandemic. So, I think it’s great to focus also on the child tax credit provisions as another aspect of immigration reform that potentially could happen in this bill.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I wanted to ask Ariel — in terms of the children of these workers, there’s been a lot of emphasis in recent months on the mental health crisis among young people in the United States. In terms of the children of these workers, what kind of services are or may not be available to them? And how did you see, in your reporting, the mental health impact on them of the situation during the pandemic?

ARIEL GOODMAN: Yeah. So, while we were in New Bedford, we surveyed 39 middle school-aged children just about what their experiences were like in the pandemic. We heard a range of responses. We heard from children who talked about enduring mental health issues. You know, we’re talking people who are around 13 years old. We heard from people who simply said that all they did was have faith and try to survive. We also heard about children who had to look for work. For whatever reason, their parents in the pandemic weren’t able to provide for their families, and so many of them got part-time jobs. We spoke to teachers who had children signing into their Zoom classes from production lines in packing plants and in lots of the other sort of industrial places in New Bedford.

So, in terms of what kind of support was available to children, I mean, this is tied to this larger issue of because — when children’s parents are denied many forms of federal aid because of their status, how does this trickle down to the children? So that was some of the things that we heard.

AMY GOODMAN: What most shocked you, Julia Preston, about this? And if you could also explain the difference between the Social Security number, the social, and the ITIN?

JULIA PRESTON: Yeah. You heard the seafood worker refer to that. She said, you know, “If only I had a Social Security number, things might be different. But as it is, I’m in the hands of God.” So, undocumented workers cannot obtain Social Security numbers, valid Social Security numbers. But an undocumented worker who is working in a factory setting or any kind of institutional setting is paid with a paycheck. They are having their standard deductions, and they are paying taxes, just like everybody else who works in that kind of a context. And so the IRS has created a special number — it’s called an ITIN — so that those workers can file their taxes and pay their taxes and, if they are eligible, receive certain kinds of refunds.

In most cases, until recently, they weren’t eligible for many kinds of refunds or tax credits. And this is another form of tax — of discrimination. This is tax discrimination that these workers are facing. And it really seems particularly unfair in this context, because they are working hard, they are paying their taxes, they are doing exactly what other people do who do have legal status and valid Social Security numbers, and yet they — excuse me — and yet they are not eligible for so many of the benefits that come from being a taxpayer for other people.

And so, that was, I think, what I would say was shocking for me, was to see the level of poverty that these families were plunged into, were forced into during the pandemic, even though they were continuing to work. The kind of hardship that these families were facing, and particularly that these kids were having to endure, was really shocking. That shocked me. I’ve seen a lot, covering immigration over the years, but the level of hardship that these families endured really did — it was something I had not seen before.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you both for being with us, and we’re going to link to your piece, Julia Preston, contributing writer at The Marshall Project, Ariel Goodman, Tow fellow at The Marshall Project. We’ll link to “Essential but Excluded: Immigrants put seafood on America’s tables. But many have been shut out of pandemic aid — and so have their U.S. citizen children.”

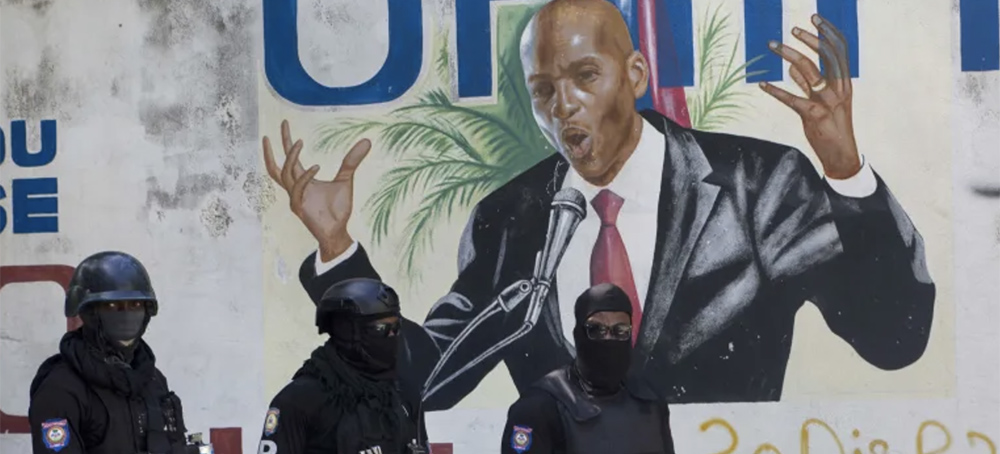

President Jovenel Moise, 53, was killed in the early hours of July 7, 2021, when a crew of armed gunmen stormed his home in Haiti's capital, Port-au-Prince. (photo: Joseph Odelyn/AP)

President Jovenel Moise, 53, was killed in the early hours of July 7, 2021, when a crew of armed gunmen stormed his home in Haiti's capital, Port-au-Prince. (photo: Joseph Odelyn/AP)

Colombian man is among dozens of suspects arrested in connection with July killing of Jovenel Moise in Haitian capital.

Mario Antonio Palacios is scheduled to have his first appearance in US federal court on Tuesday afternoon, the Miami Herald newspaper and McClatchy reported on Tuesday, citing multiple US government sources.

Palacios is a former member of the Colombian military who Haitian authorities have said was part of a mercenary group that killed Moise in July.

The Miami Herald said Palacios – who is also known as “Floro” – would be the first suspect accused of involvement in Moise’s assassination to face formal charges.

It was not immediately clear what charges Palacios faced in the US or whether he had an attorney.

Marlene Rodriguez, a spokeswoman for the US Attorney’s Office in South Florida, told The Associated Press news agency that Palacios was in US custody and would appear in federal court on Tuesday afternoon. She did not respond to additional questions including what charges he might face.

The former Haitian president was killed in the early hours of July 7, 2021, when a crew of armed gunmen stormed his home in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince.

Then-Prime Minister Claude Joseph said at the time that the assassination was “a highly coordinated attack by a highly trained and heavily armed group”.

The killing thrust Haiti, which was already struggling with a political crisis and widespread gang violence during Moise’s years in office, into deeper instability and raised fears among residents of further attacks.

Haitian authorities have arrested dozens of people, including 18 Colombians and two Americans of Haitian descent, in connection with the assassination. But their investigation has produced few concrete answers so far as to why Moise, 53, was killed.