Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

One answer might be that expectations were so high that hopes were bound to be dashed

So what’s not to be happy about? Apparently, plenty. Biden’s job approval rating is 12 points lower than when he took office – now just 41% (around where Trump’s was for most of his presidency). Most registered voters say that if the midterm elections were today, they’d support the Republican candidate. Even Trump beats Biden in hypothetical matchups. More than 60% of Americans say the Democrats are out of touch with the concerns of most Americans. And Republican congressional candidates now hold their largest lead in midterm election vote preferences dating back 40 years.

How can the economic and pandemic news be so good, and so much of Biden’s agenda already enacted – yet the public be so sour on Biden and the Democrats?

Some blame Biden’s and the Democrat’s poor messaging. Yes, it’s awful. Even now most Americans have no idea what the “Build Back Better” package is. It sounds like infrastructure, but that bill has been enacted. “Human infrastructure” makes no sense to most people.

Yet this can’t be the major reason for the paradox because the Democrats’ failure at messaging goes back at least a half century. I remember in 1968 after Nixon beat Humphrey hearing that the Democrats’ problem is they talk policy while Americans want to hear values – the same criticism we’re hearing today.

Some blame the media – not just despicable Fox News but also the corporate mainstream. But here, too, the problem predates the current paradox. Before Fox News, Rush Limbaugh was poisoning countless minds. And for at least four decades, the mainstream media has focused on conflict, controversy and scandal. Good news doesn’t attract eyeballs.

Some suggest Democrats represent the college-educated suburban middle class that doesn’t really want major social change anyway. Yet this isn’t new, either. Clinton and Obama abandoned the working class by embracing trade, rejecting unions, subsidizing Wall Street and big business and embracing deregulation and privatization.

So what explains the wide gap now between how well the country is doing and how badly Biden and the Democrats are doing politically?

In two words: dashed hopes. After four years of Trump and a year and a half of deathly pandemic, most of the country was eager to put all the horror behind – to start over, wipe the slate clean, heal the wounds, reboot America. Biden in his own calm way seemed just the person to do it. And when Democrats retook the Senate, expectations of Democrats and independents soared.

But those expectations couldn’t possibly be met when all the underlying structural problems were still with us – a nation deeply split, Trumpers still threatening democracy, racism rampant, corporate money still dominating much of politics, inequality still widening, inflation undermining wage gains, and the Delta variant of Covid still claiming lives.

Dashed hopes make people angry. Mass disappointment is politically poisonous. Social psychologists have long understood that losing something of value generates more anguish than obtaining it generated happiness in the first place.

Biden and Democrats can take solace from this. Hopefully, a year from now the fruits of Biden’s initiatives will be felt, Covid will be behind us, bottlenecks behind the current inflation will be overcome, and the horrors of the Trump years will become more visible through Congress’s investigations and the midterm campaigns of Trumpers.

Most importantly, America’s irrational expectations for quick deliverance from all our structural problems will have settled into a more sober understanding that resolving them will require a huge amount of work, from all of us.

Then, I suspect, the nation will be better able to appreciate how far we’ve come in just two years from where we were.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) at a Fox News town hall in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, April 15, 2019. (photo: Mark Makela/Getty)

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) at a Fox News town hall in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, April 15, 2019. (photo: Mark Makela/Getty)

A joint resolution of disapproval to block a proposed $650 million in U.S. arms sales to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was introduced by Republicans Rand Paul and Mike Lee, as well as Bernie Sanders who caucuses with Democrats.

While many U.S. lawmakers consider Saudi Arabia an important partner in the Middle East, they have criticized the country for its involvement in the war in Yemen, a conflict considered one of the world's worst humanitarian disasters. They have refused to approve many military sales for the kingdom without assurances U.S. equipment would not be used to kill civilians.

Activists have said Saudi Arabia has lobbied heavily against extending a mandate of United Nation investigators who have documented possible war crimes in Yemen by both the Riyadh-led coalition and the Houthi movement.

The package which was approved by the State Department would include 280 AIM-120C-7/C-8 Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAM), 596 LAU-128 Missile Rail Launchers (MRL) along with containers and support equipment, spare parts, U.S. government and contractor engineering and technical support.

In a statement Paul said, "this sale that could accelerate an arms race in the Middle East and jeopardize the security of our military technologies."

"As the Saudi government continues to wage its devastating war in Yemen and repress its own people, we should not be rewarding them with more arms sales," said Sanders in the joint statement.

Raytheon Technologies makes the missiles.

The Biden administration has said it adopted a policy of selling only defensive weapons to the Gulf ally.

When the State Department approved the sale a spokesman said the sale "is fully consistent with the administration's pledge to lead with diplomacy to end the conflict in Yemen." The air-to-air missiles ensure "Saudi Arabia has the means to defend itself from Iranian-backed Houthi air attacks," he said.

State Department approval of a sale is not necessarily the indication of a signed contract.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-CA, and other top Democrats say the vote on a multitrillion-dollar spending package is a step forward for President Biden's agenda. (photo: Jose Luis Magana/AP)

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-CA, and other top Democrats say the vote on a multitrillion-dollar spending package is a step forward for President Biden's agenda. (photo: Jose Luis Magana/AP)

The Build Back Better bill now heads to the Senate, where it’s likely to undergo some changes in order to win the support of all 50 Democratic-voting members.

The House voted 220 to 213 to pass Biden's Build Back Better bill, with one Democrat joining all Republicans in opposing the measure.

Cheers erupted on the House floor after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi declared the bill passed, followed by chants of "Nancy" by Democrats.

The bill now heads to the Senate, which is hoping for a vote before Christmas. The Senate is expected to make some changes in order to win the support of all 50 Democratic-voting members and comply with arcane budget rules. That will mean another vote in the House will be likely before the bill can become law.

The legislation includes a monthly per-child cash payment of up to $300 for most parents, child care funding, universal pre-K, an extension of Affordable Care Act subsidies and Medicare hearing benefits. It also commits $555 billion toward combating climate change, the largest such effort in U.S. history.

The bill would be financed by tax increases on upper earners and corporations, more IRS enforcement and prescription drug savings by empowering Medicare to negotiate prices for certain medications.

"We are building back better. If you are a parent, a senior, a child, a worker, if you are an American, this bill, this bill is for you. And it is better," Pelosi said on the House floor.

House Democrats had hoped to vote on the bill two weeks ago but a group of five centrist Democrats held it up over demands for a full cost estimate from the Congressional Budget Office, which released its analysis on Thursday and unlocked the votes from the holdouts.

The CBO projected the legislation would add $160 billion to the long-term deficit. But moderate Democrats were placated by Treasury Department estimates that said added IRS enforcement would yield larger savings and fully pay for the spending package.

In a lengthy speech that delayed the vote, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., blasted the legislation as the "most reckless and irresponsible spending bill in our nation's history."

He said Biden's agenda was even bigger than the New Deal and that "never in American history has so much been spent at one time."

"If I sound angry, I am," said McCarthy, who spoke for more than three hours, drawing jeers from several Democrats in the process.

On the Democratic side of the aisle, the crafting of the bill exposed deep divisions between moderates and progressives, with centrists consistently pushing to lower the price tag and strip out several provisions championed by liberals.

Some components of the bill are likely to change in the Senate, where Democrats have 50 votes and can't afford any defections.

A provision in the House bill guaranteeing paid leave is opposed by Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and is at risk of being stripped out. An expansion of the state and local tax deduction from $10,000 to $80,000 faces resistance from some senators, while immigration policies allowing legal status for young "Dreamers" and others may run afoul of budget rules.

"The BBB is very important to America. We believe it's very popular with Americans. We aim to pass it before Christmas," Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer told reporters this week.

The House vote came two weeks after Congress cleared an infrastructure package that boosts spending to $1.2 trillion for highways, roads, bridges, broadband expansion and other projects. Earlier this year, Congress passed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan to provide Covid-19 relief and stimulate the economy.

If the Build Back Better legislation makes it to Biden's desk, it will complete a legislative trifecta totaling nearly $5 trillion in approved new spending in less than a year — which Biden, Pelosi and Schumer see as important to their legacies.

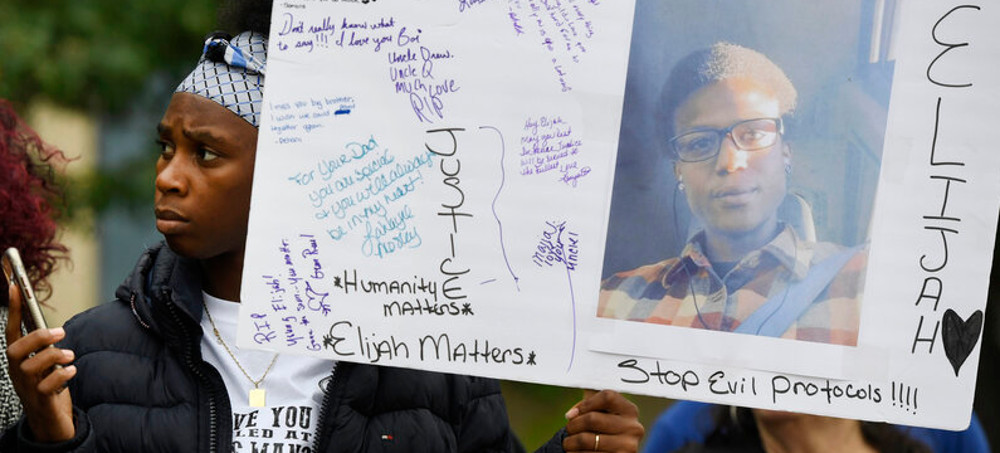

Rashiaa Veal holds a sign of her cousin Elijah McClain at an October 2019 news conference in front of the Aurora Municipal Center. (photo: Andy Cross/Getty)

Rashiaa Veal holds a sign of her cousin Elijah McClain at an October 2019 news conference in front of the Aurora Municipal Center. (photo: Andy Cross/Getty)

City leaders say they are prepared to sign the agreement as soon as the McClain family completes a separate process on dividing up the settlement.

"The city of Aurora and the family of Elijah McClain reached a settlement agreement in principle over the summer to resolve the lawsuit filed after his tragic death in August 2019," said Ryan Luby, deputy director of communications for the city in a statement sent to NPR.

Until the details are finalized, the parties cannot comment on the settlement and its terms, city officials say. A court hearing is scheduled for Friday.

NPR reached out to Mari Newman, the lawyer for Elijah McClain's father, for comment on the settlement but she declined.

However, legal representatives for Elijah McClain's mother, Sheneen McClain, told local TV station CBS4 Denver that she is thankful for the community and its "incredible support, love and commitment" to ensure Elijah McClain's death would lead to meaningful reform.

"While nothing will fill that void, Ms. McClain is hopeful that badly needed reforms to the Aurora Police Department will spare other parents the same heartache," the statement continues.

On Aug. 24, 2019, Elijah McClain was confronted by police while walking home with an iced tea he had just bought. A caller told a 911 operator they had seen someone "sketchy" in the area.

Later as police confronted McClain, who was not armed, they placed him in a chokehold, ignoring him as he cried in pain and vomited. McClain suffered cardiac arrest after paramedics injected him with ketamine, a powerful sedative, and he died six days later.

He was not suspected of any crime.

McClain's cause of death was listed as "undetermined" by the coroner.

His parents filed a federal civil rights lawsuit in August 2020 against Aurora, as well as numerous police officers, a paramedic and the medical director of Aurora Fire Rescue.

The complaint alleges that there was no reason for McClain to be given ketamine and that the dose was too large for his body weight.

In September, a state grand jury filed 32 criminal charges against three Aurora police officers and two paramedics. The charges included manslaughter, assault and criminally negligent homicide.

A civil rights investigation prompted by McClain's death found a pattern of racially biased policing in Aurora.

Julius Jones's aunt LeAnnesya Jones, left, and his cousin Rochelle Lewis embrace on Nov. 18 after Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt granted clemency for Jones. (photo: Nick Oxford/Reuters)

Julius Jones's aunt LeAnnesya Jones, left, and his cousin Rochelle Lewis embrace on Nov. 18 after Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt granted clemency for Jones. (photo: Nick Oxford/Reuters)

Between 5 and 7 p.m. Central time on Wednesday, Julius Jones, 41, was served his last meal — one that could not exceed $25, according to Oklahoma Department of Corrections policy. Two hours later, his phone and visitation privileges were suspended. As the 12-hour countdown to his scheduled 4 p.m. lethal injection began, Jones went through the motions of the state’s protocol — including a strip-search before being placed in a cell feet away from the execution chamber and check-ups every 15 minutes.

But four hours before Jones was set to be executed Thursday over the 1999 murder of Oklahoma City businessman Paul Howell, Gov. Kevin Stitt (R) commuted his death sentence to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. The governor made the decision “after prayerful consideration and reviewing materials presented by all sides of this case,” he said in a statement.

The decision brought elation for many — especially as the questionable circumstances of his case garnered national attention and drew in a slew of high-profile supporters. While Jones’s advocates range from Hollywood stars and NBA athletes to university students and community preachers, the frenzy behind his case demonstrates more than the power of social media to influence change — rather, it has put a focus on the widespread problems within death penalty cases, experts said, at a time when a majority of Americans oppose the policy.

Jones, who was recommended for a commutation and later clemency by Oklahoma’s Pardon and Parole Board, has maintained his innocence since his arrest at age 19. His attorneys have argued that Jones was framed by a former friend — claims that were featured in “The Last Defense,” a 2018 ABC documentary produced by actress Viola Davis and her producer husband, Julius Tennon. The two, who are filming in South Africa, celebrated Stitt’s decision Thursday.

“We are soooo happy for Julius and his family,” Tennon said in a written message to The Washington Post. “Praise God!!!”

The sentiment was shared in the Jones household, where Jimmy Lawson — his best friend since childhood who has spearheaded the fight for Jones — accompanied the 41-year-old’s parents in their Oklahoma City home Thursday as they watched the news waiting for updates. When the decision came, Jones’s mother broke into a dance, he said.

“If you could see a boulder lift off someone’s shoulder, that’s what it looked like for Mama Jones,” Lawson told The Post. “We saved a man’s life today.”

The eleventh-hour move was bittersweet for others, who scorned the “cruelty” of having Jones’s life seemingly cling by a thread.

Stitt “had Julius Jones undergo all the rituals and rites of execution. This is part of the cruelty and perversion of an immoral state with unmerited power to decide who lives and dies,” Marc Lamont Hill, a professor at Temple University who has advocated against the death penalty, wrote on Twitter.

The Rev. Don Heath of the Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty also took aim at the governor’s handling of the case. For weeks, Stitt had been pressured to grant a clemency request after Jones exhausted his legal appeals.

“It is definitely a mixed blessing,” he said in a statement. “We are thankful that Julius’ life was spaced. We grieve that he will have to spend the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of parole. That is also cruel and unusual.”

While Stitt’s actions have come under scrutiny, governors often take time to commute sentences or grant clemency, said Robert Dunham, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. Their timeline is often skewed by the emotions behind the situation — especially, as in Jones’s case, when the defendant’s family members are convinced of the trial’s verdict.

“The more difficult the decision is or the more painful the decision is for the person to make, the more likely it is to be made at the last minute,” he said. “None of this is emotionally good for anyone, and it is especially emotionally difficult for the families of the victims and the families of the defendant.”

Howell’s survivors, including his sister Megan Tobey — who witnessed his murder after a botched carjacking — have spoken out at hearings about the pain caused by Howell’s murder and their belief in Jones’s guilt. Stitt met with the family prior to announcing his decision.

Still, Jones’s case is notable, Dunham said, because of the circumstances of his case — including an inexperienced public defender, questionable police informants and a prosecuting office with “a culture of misconduct.” Bouts of racism also emerged among jurors who referred to Jones “by the n-word,” Dunham said.

These factors — compounded by a renewed advocacy for social justice — helped shape Jones’s experience into an “exceptionally high-profile case," he said.

"I don’t think that the attention made the case exceptional,“ said Dunham, whose nonpartisan organization provides information and analysis on death penalty issues. “None of that would have happened, but for the fact it was an exceptional case, filled with evidence of discrimination and the fact that this looked like another possibly innocent Black person being executed.”

Jones’s commuted sentence comes at a time when Oklahoma’s death penalty protocol has faced wide scrutiny. The state ended a six-year moratorium on executions in October following a string of botched lethal injections in 2014 and 2015. That same month, John Marion Grant convulsed repeatedly and vomited after the lethal injection was administered.

At the same time, attitudes toward the death penalty have changed dramatically over the decades. According to a Gallup survey published Thursday, Americans’ support for the policy continues to be lower than at any point in nearly 50 years, at 54 percent. The trend coincides with crime rates in the nation — when public concern over crime was at an all-time high in 1994, support for capital punishment peaked at 80 percent, the study shows.

Though Jones has been the latest case to shed light on issues presented in the country’s criminal justice system — becoming only the sixth person on Oklahoma’s death row to be granted clemency since 1973 — many others could still be facing a miscarriage of justice, death penalty opponents say.

“So while it’s notable that Julius Jones’s case got attention and that he became the 295th person to be granted clemency [in the United States], people should not forget that there are many other cases that have not and will not receive this kind of attention,” Dunham said. “There are still so many like Julius Jones.”

The aftermath of U.S. coalition bombings at the Sousa roundabout in Syria in January 2019. (photo: The Intercept)

The aftermath of U.S. coalition bombings at the Sousa roundabout in Syria in January 2019. (photo: The Intercept)

The aerial campaign in eastern Syria dislodged the terrorist group from the final patch of land it controlled but cost an untold number of lives.

The last ISIS fighters had finally been corralled in March 2019 in a small village called Baghuz, between the Euphrates and the Iraqi border. ISIS made its last stand there, the fighters mixed together with family members and civilians trapped by the conflict as the U.S.-led coalition pummeled the village from the air.

“It’s hard to imagine how anybody can survive,” said CBS News reporter Charlie D’Agata, who watched airstrikes from the ground near Baghuz in March 2019.

In an investigation published last weekend, the New York Times told the story of one those assaults. On March 18, 2019, the U.S. Air Force dropped a 500-pound bomb, followed by two 2,000-pound explosives, on a crowd of women and children near the river in Baghuz.

“Who dropped that?” a Defense Department analyst monitoring a drone typed in a secure chat, according to the Times story.

“We just dropped on 50 women and children,” another analyst responded.

The Times described the airstrike as “one of the largest civilian casualty incidents of the war against the Islamic State.” It came to light only after investigations, including by the independent inspector general and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, had been blocked or buried.

But this bombing of women and children was not a tragic accident in an otherwise controlled and closely monitored aerial campaign. The bombing was in fact one of the final strikes in a monthslong string of attacks that killed scores of civilians. I know this because I was in touch almost daily with an American who lived through these bombings until he was killed by an airstrike in Baghuz, likely just before the bombing the Times described.

Russell Dennison, who was among the first Americans to join ISIS as a fighter, secretly sent me more than 30 hours of recordings from August 2018 to February 2019. Dennison’s later recordings captured the roar of airstrikes he and his small family witnessed, and Dennison regularly sent me photographs of the aftermath. I tell Dennison’s story, including his descriptions of the U.S.-led coalition’s bombing campaign, in “American ISIS,” an eight-episode Audible Original documentary podcast released in July from The Intercept and Topic Studios.

While the specific bombing the Times described shows that Defense Department officials knew that they’d killed civilians and then made efforts to keep the bombing from public scrutiny, it was clear at the time that the coalition’s campaign was not sparing civilians. “But these bombings were not well covered by the international media at the time,” said Chris Woods, director of the London-based Airwars, which tracks civilian harm in war zones in Iraq, Syria, and Libya. Airwars claims to have confirmed 1,417 civilian deaths from coalition airstrikes in Syria and Iraq, though the group estimates that number could be more than 13,000.

Syria’s Deir el-Zour province, where Baghuz is located, is a remote part of the world, and ISIS’s control on the ground and the coalition bombs dropping from the air made access to the area nearly impossible for journalists and international monitors. As a result, the full extent of civilian death in the area may never be known.

Dennison may have been the only witness on the ground in Deir el-Zour who documented the bombing campaign in real time. He sent me recordings and pictures following each night’s attacks. What he described and photographed over months in Deir el-Zour suggested that the U.S.-led coalition must have been aware that civilians were perishing in large numbers.

As Dennison recorded one message to me during the bombing campaign, the deafening sounds of an exploding bomb consumed the audio. A few seconds later, Dennison can be heard, speaking into his phone.

“You hear this?” he said me. “You see, this is major American airstrikes.”

“They Were All Killed”

Dennison was a red-bearded, white convert to Islam who crossed into Syria in 2012. He joined ISIS shortly after the group split from Al Qaeda and its previous affiliate in Syria, the Nusra Front. Fighting under one of ISIS’s best-known commanders, Abu Yahya al-Iraqi, Dennison helped establish the so-called caliphate in Syria and Iraq.

After a sniper’s bullet to the leg hobbled him, Dennison moved to Raqqa, as the city attracted foreign fighters from around the world. In Raqqa, Dennison married a Syrian woman, with whom he had two daughters. In late 2017, Raqqa fell to the U.S.-led coalition, and Dennison and his wife and children followed other ISIS fighters and their families to Deir el-Zour. During a lull in the bombing campaign through much of 2018, Dennison worked for a secret ISIS unit — first revealed in “American ISIS” — that intercepted communications from militaries operating in the region. Dennison’s job was to listen to the Americans. But by December 2018, Dennison and his family were on the run again, shuffling back and forth between villages in Deir el-Zour as the coalition airstrikes intensified.

That month, Dennison told me that the coalition had intentionally bombed a hospital in Al Shafah. The bombing, according to Dennison, was similar to the one described by the Times: an initial strike followed by two more bombings. “The Americans destroyed this hospital, and they killed everybody inside it,” Dennison told me. “The second floor was full of women nurses who were responsible for the whole hospital, and they were all killed.”

At the time, the Defense Department confirmed to me that this hospital had been bombed, claiming that ISIS fighters were using the area as a staging ground. Dennison also told me that he’d seen hospitals bombed in two other villages, Sousa and Hajin, though the Defense Department would neither confirm nor deny that information at the time. (Rules of war established by the Geneva Conventions require civilian hospitals to be protected from targeting, but those same rules require the opposing force to separate civilian hospitals from military activity.)

In January 2019, as The Intercept reported at the time, the Defense Department abruptly stopped issuing detailed “strike releases” — periodic reports, which had been released since the start of the campaign against ISIS, that provided detailed information about specific bombings. They did so even as coalition bombings in Deir el-Zour increased.

As Dennison and his family moved from village to village, they shared space with other ISIS fighters and their families. In one village, he and his wife and daughters roomed with three other families. That was part of the coalition’s challenge in eastern Syria: ISIS wasn’t a traditional army. Many of the group’s fighters were married and had children, and their families traveled with them. Syrians unrelated to ISIS fighters were packed into the villages as well, leaving no delineation between combatants and civilians. Bombing ISIS fighters in Deir el-Zour meant bombing civilians. So-called collateral damage was guaranteed.

In late 2018, Dennison and his family were trapped in Al Kashmah, a village north of Baghuz, as coalition airstrikes and artillery rained down. The recordings Dennison sent me from the night of December 31, 2018, New Year’s Eve, were filled with the sounds of bombings nearby. “There’s some crazy airstrikes tonight,” Dennison said. “So I hope that me and my family, we live through this night, you know. But this is our life.”

Dennison sent me photos of the destruction from Al Kashmah. The village had been leveled, with large buildings flattened to rubble in the sand. He and his family then headed south, but as the bombings continued, Dennison decided in January to put his wife and children on a bus headed out of ISIS-controlled Syria and to a displaced persons camp run by Kurdish forces.

One early morning, as Dennison and his family prepared to walk through the cold to a waiting bus in Sousa, the coalition bombed the village’s nearby roundabout, Dennison told me. “We could hear the debris and the shrapnel and the rocks and stones fly everywhere,” he recalled. “We were only about 200 meters from this circle.” Although the Defense Department had stopped issuing detailed strike releases by this time, it did acknowledge 645 strikes in Syria around the time of the attack Dennison said he witnessed in Sousa.

Dennison and his family walked past the roundabout to the bus, their weakly charged flashlight cutting through the darkness. As they passed, Dennison could hear a young boy screaming for help. He’d been buried beneath rubble following the airstrike.

Dennison later sent me a photo of the roundabout in Sousa. The buildings surrounding it had been destroyed, leaving piles of concrete, shorn support beams, and a large crater in the ground.

“Resurgence of a New Adversary”

The U.S.-led coalition knew that its bombing and artillery campaign in Deir el-Zour was killing civilians. In February 2019, around the same time that Dennison heard the boy screaming from beneath the rubble, a senior French officer wrote an article in a French military journal criticizing the coalition’s tactics.

Col. François-Régis Legrier, who had been in charge of French artillery in the region, wrote that the coalition relied too heavily on bombings and artillery because the U.S., British, and French militaries were not willing to put soldiers on the ground. “This refusal raises a question: why have an army that we don’t dare use?” Legrier asked in his article.

The bombardment of the packed villages resulted in significant civilian casualties, Legrier alleged. “We have massively destroyed the infrastructure and given the population a disgusting image of what may be a Western-style liberation leaving behind the seeds of an imminent resurgence of a new adversary.”

Dennison never knew of Legrier or his article, but he told me something similar. He said that he likely wouldn’t survive and that ISIS might fail, but the children who lived through the bombing campaign would remember who was responsible. “People would be saddened to see the reality of what the U.S. is doing in the name of America and Western democratic freedoms and these other types of values,” Dennison told me.

My last communication with Dennison was in February 2019. He was trapped in Baghuz, the fighting all around him. In his final message to me, he described seeing a bus filled with women and children bombed as it tried to leave ISIS-controlled territory. “They don’t put two per seat. These people pack on everywhere in the Middle East, as many as they can,” Russell said. “So we’re talking 50 to 60 people.”

The women and children on the bus were trying to escape, Dennison told me. The ISIS caliphate was about to collapse under the coalition airstrikes. “This bus was targeted by U.S. warplanes and killed everybody inside, and I personally I saw this myself,” Dennison said.

I could not independently verify Dennison’s account of the bus being bombed, and for that reason, I did not include it in “American ISIS.” But Dennison’s story was similar to the bombing in Baghuz that the Times investigated.

Dennison died in an airstrike in Baghuz not long after sending me that recording about the bus. I don’t know exactly when he died, but it was likely in late February or early March, just before the U.S. dropped a bomb on a crowd of 50 women and children in Baghuz and an analyst monitoring the drone footage posed an urgent question: “Who dropped that?”

Despite a Supreme Court ruling, Coastal GasLink is on track to be built through unceded land. (photo: Michael Toledano)

Despite a Supreme Court ruling, Coastal GasLink is on track to be built through unceded land. (photo: Michael Toledano)

Despite a Supreme Court ruling, Coastal GasLink is on track to be built through unceded land.

The area that was being prepared for construction lies within the territory of the Wet’suwet’en, a First Nation in what is currently called British Columbia, Canada. As a supporting chief from the Likhts’amisyu clan, Dsta’hyl had been tasked with enforcing Wet’suwet’en law in the area.

The scene he was witnessing — construction crews preparing to build a pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory, without their consent — represented a blatant violation of those laws. And Dsta’hyl had seen enough. After warning the on-site construction managers that they were trespassing, he arrived the next day and approached a pair of orange-vested security subcontractors employed by TC Energy, the company building the fracked gas pipeline known as Coastal GasLink, or CGL. He notified them that he would be seizing one of their excavators and then stepped onto the hulking vehicle and disabled it by disconnecting its battery and other components. Though he planned to leave the vehicle in place, Dsta’hyl said he wanted to make a statement to the company, which the traditional leaders decided to evict from their territory last year.

In a video posted on social media, one of the security workers asks Dsta’hyl what he wants from them. He lets out a hardy laugh.

“For you guys to leave,” he says.

In another clip, Dsta’hyl stands on the vehicle as the workers below angle camcorders at him. “You guys are trespassing, and we want to make sure that you guys know that we mean business.”

The crew members abandoned the area shortly after, driving off in their pickup trucks and construction vehicles — short one large piece of machinery. And while Dsta’hyl had gotten his message across, the asset-seizure was short-lived.

“In the middle of the night, they stole that one back,” he said.

That incident was one of the latest standoffs between the Wet’suwet’en and Coastal GasLink over the proposed pipeline, which, if completed, would carry 2 billion cubic feet per day of fracked gas from northeastern B.C. to a proposed processing facility on the Pacific coast. Although the company says it received all necessary permits and approvals to build the pipeline, the hereditary chiefs of the five clans of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation contend that because they never gave the company permission to build on their territory, the construction efforts violate their laws — not to mention Canada’s own laws.

The tribe organizes itself into five clans, each of which is subdivided into multiple “houses.” The house chiefs oversee specific areas within the tribe’s traditional territory, which encompasses roughly 22,000 square kilometers (8,500 square miles). The hereditary chiefs make decisions that govern their territory.

“It’s quite an intricate governance system,” Dsta’hyl said, adding that the Wet’suwet’en have been practicing these laws for thousands of years.

The Wet’suwet’en government was recognized in a 1997 ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada, which held that the First Nation had never given up rights or title to their lands. And, like other First Nations in Canada’s westernmost province, the Wet’suwet’en never signed a treaty with the British Crown nor the Canadian government, meaning their territory is unceded land.

“They never surrendered or ceded their territory, so what they’re dealing with is this incursion by pipeline companies and police who are basically invading,” said Clifford Atleo (Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth) , an assistant professor of resource and environmental management at Simon Fraser University whose work focuses on Indigenous governance.

“What the Wet’suwet’en are doing is protecting their lands,” Atleo said.

Fearing the destruction of their territory, as well as harmful impacts to water, wildlife and people, some members of the Wet’suwet’en have taken direct action against a slew of proposed pipelines over the past decade. They have created dozens of checkpoints and blockades to prevent construction crews from accessing Wet’suwet’en lands and significant sites. In 2009, members of the Unist’ot’en clan established a checkpoint near a small bridge that leads onto their territory, which they maintained alongside Indigenous and non-Indigenous allies for more than ten years. Another blockade was later built on the same road in the neighboring Gidimt’en territory, where, in January 2019, a series of police raids drew international media attention.

Donning tactical gear and armed with military-style rifles, officers stormed the Gidimt’en checkpoint, arresting 14 land defenders as the officers dismantled the camp. Documents obtained by the Guardian suggest that the officers were prepared to use lethal force against Wet’suwet’en land defenders during the raid.

A year later, the Unist’ot’en camp was raided by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, or RCMP. Several people were arrested in the 2020 raid, during which officers sawed through a wooden barricade with the word “RECONCILIATION” painted on it, clearing the way for CGL crews to build on Wet’suwet’en territory.

Both incidents sparked renewed controversy regarding the tactics the RCMP employs in suppressing protests, with many critics highlighting the agency’s history of using excessive force against Indigenous land defenders as well as violent, anti-Indigenous sentiments among its ranks. The RCMP asserts that the raids and ongoing patrols in the area are necessary to enforce a court order that prohibits protestors from blocking CGL construction. A provincial court handed down the injunction three years ago, and, in the time since, both the RCMP and the company have used the legal ruling to restrict access to certain areas and to arrest land defenders who stand in the way of the project.

But Indigenous people have continued to resist the pipeline, using tactics that escalated over the weekend, when members of the Gidimt’en clan demolished a section of road that CGL has used to access Wet’suwet’en territory.

On Sunday morning, CGL employees and subcontractors were given an immediate evacuation order. “You have eight hours to vacate the territory peacefully,” said Sleydo’, a supporting chief from the Gidimt’en clan, who made the announcement over the radio. “Failure to comply will result in immediate road closure.”

But land defenders saw little movement along the road — even after the company negotiated for a two-hour extension. When members of the group approached a man camp they had ordered to disband, they discovered construction crews were not preparing to leave, and had positioned multiple construction vehicles and machinery on the road, said Jennifer Wickham, a member of the Gidimt’en clan who serves as media coordinator for the group.

In response, land defenders seized a CGL excavator and destroyed a segment of the roadway before dropping a crumpled minivan at a bridgehead. Wickham said that, given RCMP’s previous enforcement of injunctions, a police raid may be imminent.

“We absolutely expect them to do that,” she said. “As far as when, we have no idea.”

In an email, an RCMP spokesperson said the agency “is aware of the protest actions and we have, and will continue to have, a police presence in [the] area conducting roving patrols. No arrests were made and we continue to monitor the situation.”

The hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en say the injunction, RCMP’s enforcement of it, and the project itself represent an affront to First Nations sovereignty, pointing to the 1997 Supreme Court decision as proof that they have the constitutional right to expel CGL from their territory.

In what is known as the Delgamuukw case, the court confirmed that “Aboriginal title is a right to the land itself” based on occupation of the area and a system of law that predates British and Canadian colonization. The Supreme Court decision left many issues unresolved, though, such as the exact boundaries of the tribe’s traditional territories.

Despite the house chiefs’ legally recognized authority, the pipeline company never engaged in meaningful consultation with them, Sleydo’ said.

“They will send information, but they don’t actually give us the opportunity to engage with that information, and when we have responded, they disregard everything we say,” she said. “That’s not consultation and it’s definitely not consent.”

The company frequently states that it received approval from the Wet’suwet’en because it negotiated an agreement with the tribe’s elected band councils. Imposed by the Canadian government under the Indian Act of 1876, the band-council system was created to facilitate interactions between First Nations and the federal government. The councils are considered the governing bodies for their respective First Nation reserves, and elected representatives from 20 band councils along the pipeline route signed so-called “benefit agreements” with the company to allow construction. Although councils from multiple reserves within Wet’suwet’en territory approved the project, the hereditary chiefs — as representatives of older, traditional styles of government — say they retain authority over their traditional lands, and that CGL needs their permission to access the territory.

The company claims it has sought numerous meetings with the hereditary chiefs in the past two years, and that it continues to seek input from Wet’suwet’en leaders “with the sincere hope of developing a respectful and constructive relationship as we move to completion of the Project and beyond.” In an email, CGL spokesperson Natasha Westover cited safety concerns as justification for blocking Wet’suwet’en people from their territory.

“Coastal GasLink has an obligation to facilitate access for [I]ndigenous peoples to their traditional territories, however, that access may be delayed where it is unsafe [to] provide access immediately,” she said. Westover declined to provide an interview with CGL executives or other personnel for this story, despite multiple requests.

After CGL’s injunction was made permanent last winter the Wet’suwet’en house chiefs unanimously decided to evict the company from its territories.

Flowing from a glacier-fed lake, Wedzin Kwa runs through the heart of Wet’suwet’en territory. The river provides important spawning grounds for salmon, and supplies community members with unpolluted drinking water.

“You could swim in that lake and just open your mouth and drink the water, it’s so pristine,” Sleydo’ said. “And the river is so clear that you can see these very deep spawning beds that the salmon have been returning to for thousands of years.”

CGL plans to construct the pipeline beneath the river. In September, when members of the Gidimt’en clan heard that construction crews were preparing to tunnel under Wedzin Kwa, they rushed to occupy the site. They have since erected several structures, including a cabin with a full kitchen and multiple solar-powered “tiny homes.”

Because the conflicts with RCMP in recent years have escalated in the dead of winter, the Gidim’ten clan has experience erecting blockades in temperatures as low as minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and welcomed the chance to set up camp with only a light snow in the ground.

“Blockade season came early this year,” Sleydo’ said.

Despite the mounting tensions, Sleydo’ said the members of camp try to remain upbeat, laughing and telling stories around the campfire at night.

But the mood changes when the RCMP approaches the area. In the days after the outpost was established, RCMP officers tasered a person and injured a man who had locked himself to the underside of a bus. Sleydo’ said officers grabbed the man by the legs and repeatedly lifted his body and slammed him onto the ground as a way of forcing him to unclip himself from the vehicle. She said the RCMP’s use of “pain compliance” equates to torture.

“That person is still receiving ongoing medical care and has [nerve damage] in his hands,” she said.

The national police force frequently sends members of a specialized division with a reputation of using excessive force against protestors. Known as the Community-Industry Response Group, or C-IRG, the roving unit draws RCMP officers from far-flung areas of Canada to break up protest camps that form in opposition to pipelines, mining projects and logging operations.

Officers with the unit have been widely criticized in recent months for their aggressive tactics in breaking up anti-logging protests near Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island. In addition to making violent arrests and showering unarmed protestors with pepper spray, many of the officers removed all forms of identification from their uniforms during multiple raids. British Columbia Supreme Court Justice Douglas W. Thompson condemned those actions in his decision to end an injunction against the Fairy Creek protestors, writing that RCMP’s enforcement tactics “have led to serious and substantial infringement of civil liberties.”

During RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory, officers often brandish sniper rifles and bring in police dogs to intimidate land defenders, Sleydo’ said. “If we’re trying to defend a space, we’re considered a huge threat,” she said. “And they use that as an excuse to use violence and excessive force against us.”

The agency’s media relations team did not provide a phone interview despite multiple requests.

Miles Howe, an assistant professor of critical criminology at Brock University, said the RCMP often engages in “political policing,” in that the agency targets groups that are considered threats to Canada’s access to natural resources — and, by extension, the economic interests surrounding the extraction of those resources. Howe co-authored a 2019 report that used documents obtained through records requests to show that the RCMP performed extensive surveillance of Indigenous land defenders and assessed the risk posed by protestors not based on criminality, but on their ability to rally public support.

The RCMP raids in early 2020 sparked nationwide protests in Canada, leading Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to voice tepid support for Wet’suwet’en sovereignty, though he later demanded that the “barricades come down.” Months later, federal and provincial government officials agreed to engage in land-rights negotiations with the hereditary chiefs.

“So far, nothing has come from that process,” said Jennifer Wickham, who serves as media coordinator for the Gidimt’en resistance group.

Instead, the Canadian government has subsidized Coastal GasLink and continues to tout the benefits of liquified natural gas as a “transition fuel” that will set Canada on a course to reach its ambitious climate goals. Earlier this month, Trudeau took the stage at the UN climate change conference in Scotland to outline Canada’s plan to cap oil and gas emissions in order to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

“That’s no small task for a major oil and gas producing country,” he said.

But critics say Trudeau’s commitments run counter to his administration’s support of natural gas projects, which have been shown to leak large amounts of methane — a powerful greenhouse gas — into the atmosphere. Given the outsize impacts climate change often has on Native communities, Indigenous rights advocates say it is critical that First Nations are adequately consulted on resource-extractive projects that take place on their ancestral lands.

In 2014, the UN’s special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples implored the Canadian government to seek the “free, prior and informed consent” of First Nations in the early stages of a project. The U.N. Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that Natives “have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership” and that they “shall not be forcibly removed from their territories.” Earlier this year, legislators passed a bill aimed at implementing UNDRIP into Canadian law.

And yet, the government is enabling Coastal GasLink to push its pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory.

Sleydo’ said the group is “digging in for winter,” and has no intention of allowing the pipeline to cross Wedzin Kwa. The mother of three children said that, although it has been difficult being away from her family during the occupation, she refuses to pass the pipeline’s impacts down to her children.

“They will not drill under our sacred headwaters because we’re going to defend this space until the end,” she said. “We’re not going anywhere.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611