Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

On the eve of the President’s first anniversary in office, members of the chamber he served for so long voted for paralysis over action.

His faith in the Senate’s potential was not just empty pride. Since Biden was first elected to that chamber, from Delaware, in 1972, he had witnessed a variety of examples of feuds over big issues in which senators ultimately accepted personal political risk in the name of a larger national purpose. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appealed across the aisle to Howard Baker, of Tennessee, the Republican Minority Leader, to support a treaty transferring the Panama Canal to local control (a move primarily intended to improve Washington’s dealings with Latin America). Baker’s aides warned him that collaborating with Carter would doom his dream of becoming President, but Baker, it is said, weighed the national-security implications and replied, “So be it.” He backed the treaty and there was no Baker Presidency. (As a consolation prize, Baker is remembered as the “Great Conciliator.”)

When disputes erupted within parties, senators spoke admiringly of those who found their way to manage their ambitions within the larger goals. In 1993, during Bill Clinton’s first year in office, he pressed Democrats to support higher taxes in his economic program, but Senator Bob Kerrey, of Nebraska, wouldn’t budge. Clinton, in a profane, private phone call, accused him of dooming the prospects of his Presidency. Kerrey resented it, but eventually backed Clinton, saying, in a speech on the Senate floor, “I could not and should not cast the vote that brings down your Presidency.”

When Biden entered the Presidential race in 2019, he had abundant firsthand knowledge of how far the Senate in the era of the Republican leader Mitch McConnell had fallen from its self-image. As Vice-President, he had witnessed McConnell’s famous pledge to stymie the Obama Administration at every turn; his blockage of Barack Obama’s right to nominate a Supreme Court Justice; his exponential growth of the use of the filibuster. But that evidence competed in Biden’s accounting with his own history of finding a way to work with unsavory and obstreperous counterparts, including the segregationists Strom Thurmond and James Eastland. Biden had even found a way to a deal with McConnell in the final days of 2012, agreeing to leave tax cuts in place in order to avert the Republicans’ threat to default on the debt ceiling. It had irritated fellow-Democrats, but served as fresh evidence of Biden’s contention that nobody was truly immune to negotiation.

As the election approached in 2020, even as the toxicity of the Trump era infected more of Washington, Biden held fast to his contention that he could persuade enough of his opponents to join him. “All you need,” he told me in an interview that summer, “is three, or four, or five Republicans who have seen the light a little bit.” He added, “I don’t think you can underestimate the impact of Trump not being there. The vindictiveness, the pettiness, the willingness to, at his own expense, go after people with vendettas.”

It took a long, costly year in the White House for Biden to confess that he had bet wrong on the Senate he once knew. On Wednesday, during a marathon press conference on the eve of his first anniversary in office, Biden conceded, “I didn’t anticipate there’d be such a stalwart effort to make sure that the most important thing was that President Biden didn’t get anything done.” Speaking to reporters in the East Room of the White House, he returned to the subject several times. “My buddy John McCain is gone,” he said, lamenting the absence of the late senator from Arizona, who had been a frequent partner on legislation and, not incidentally, one of the few Republican senators who ever challenged the calumnies and cruelties of Donald Trump. At one point, Biden posed a question to the audience that seemed at least as much a question to himself: “Did you ever think that one man out of office could intimidate an entire party, where they’re unwilling to take any vote contrary to what he thinks should be taken, for fear of being defeated in a primary?”

There were, of course, some who had urged Biden against believing that he could win Republican support. During the campaign, a Democrat who had served in the White House asked, of Biden’s assumptions, “Does he see his role as someone who can bring in the Never Trumpers and build some bipartisan consensus? I know from experience that’s a trap. We walked right into it. Your people lose faith, the Republicans never give you credit, you waste a lot of time—and you end up with the Tea Party.”

In the end, of course, it was not just Republicans who dented Biden’s hopes for the Senate; members of his own party lent a hand. For months, Biden and other Democratic leaders indulged and romanced the dissidents within, chiefly Joe Manchin, of West Virginia, and Kyrsten Sinema, of Arizona—cutting one proposal after another to meet their demands on infrastructure, voting rights, and social-safety-net programs under the Build Back Better plan. In public, Senate colleagues avoided criticizing the holdouts, who would eventually be needed for votes in the future. Manchin stoked that belief, telling reporters, in a faint echo of Kerrey’s comments from 1993, that, for all his objections, he intended to “make Joe Biden successful.” As Democrats pushed to finalize the Build Back Better plan, patience was running thin. “You have made your mark on this bill, you’ve dramatically cut its cost,” Dick Durbin, the second-ranked Democrat in the Senate, told CNN, referring to Manchin. “Now close the deal.” Instead, Manchin killed it, announcing on Fox News that he could never support the bill as written.

In that light, it was a fitting bit of scheduling that, while Biden was in front of reporters at the White House on Wednesday, Manchin was speaking in the Senate, in an effort to prevent his party from changing Senate rules to allow passage of voting-rights legislation in the face of Republican resistance. All fifty Republicans later voted against the voting-rights bill, but Manchin did not suggest a way around it; on the contrary, he urged his colleagues, in effect, to embrace a high-toned paralysis. “The Senate’s greatest rule is the one that is unwritten,” he said. “It’s the rule of self-restraint, which we have very little of anymore.” By the end of the evening, Manchin and Sinema had voted with the Republicans against changing the rules, a moment that seemed to crystallize the frustrations of Biden’s first year of dealing with the Senate he revered.

For voters, activists, and reporters who have come of age in the era of intractable divisions, it can be difficult to relate to a time when Congress found a way to compromise. “It is so dramatically different from the place I worked,” Ira Shapiro, a Senate staffer from 1975 to 1987 and the author of “Broken: Can the Senate Save Itself and the Country?,” told me on Wednesday. “There were certainly times when the Senate brought legislation to the floor when you didn’t know what the outcome would be, whether it was energy legislation, or labor-law reform, or the Civil Rights Act of ’64.” Shapiro went on, “You were counting on debate on the floor, persuasion in the cloak rooms, time for the interest groups to do their lobbying, coalitions to form, and compromises to be offered. But those were times when people were operating in good faith, and bipartisan compromises were possible.”

Biden’s pitch, as a candidate, always contained the sources of both his strength and his vulnerability. His odes to unity and his faith in government seemed positively countercultural, after four years in which Trump had bathed Americans in his sulfurous brand of cynicism. During the campaign, Biden’s broad, if vague, assurances that Washington could be redeemed effectively contrasted with Trump’s undisguised politico creed—a jumble of whataboutism, contempt for human rights and American ambition, a Putinist assumption that everyone operates in bad faith. Even voters who found Biden uninspiring gravitated to him out of sheer exhaustion with the Trumpian gloom.

As Biden passed his first anniversary, the assessments of his tenure mapped, in predictable fashion, on to the terrain of Washington. The White House pointed to the creation of 6.4 million jobs, more than had been created in any previous year; to an unemployment rate of 3.9 per cent that was far below the level when he took office; and to generational investments in infrastructure. But his approval ratings were dismal—lower than those of any post-Second World War President except for Trump at the end of his first year—and no matter how many times it was noted that the President was only at the end of the first quarter of his term, columnists already seemed to be competing to declare game over as early as possible. If Washington ever had a “cooling” saucer, it has rarely been harder to find.

Among the assessments of Biden’s first year, it was tempting to fault him for a stubborn naïveté, but Ira Shapiro understands the impulse to see the Senate redeem itself. “I doubt that Biden was under any illusions about the changes in the Senate, or about McConnell. I think he believed that the multiple crises in the country were clear enough that people, in good faith, would come together and make our government work. And he would’ve thought—most of us would’ve thought—that the fundamental assault on our democracy would be clear enough that at least Sinema and Manchin, and, perhaps, one or two Republicans, would recognize the threat.” He added, “The tragedy is we’re still living in McConnell’s America, aided and abetted by Manchin and Sinema.”

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema arrives for a Senate vote in the U.S. Capitol on Thursday, October 28, 2021. (photo: Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call/Getty)

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema arrives for a Senate vote in the U.S. Capitol on Thursday, October 28, 2021. (photo: Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call/Getty)

“I’m livid. I can only call her a turncoat,” one former volunteer said. “I feel betrayed.”

Dunn, a leader in the local chapter of the Indivisible progressive activist group in Prescott, Arizona, was introduced to Sinema at a campaign event and was blown away by the Senate candidate’s poise and her impressive life story. Her group hosted Sinema multiple times for events. Dunn volunteered, by her estimation, for more than 100 hours to elect Sinema and other Democrats that election cycle.

“I was very impressed. I had literature, I did canvassing for her, I contributed, I campaigned. We did everything we possibly could to get her elected. We were very excited about her. We knew she was a Democrat who had centrist tendencies, and that wasn’t a bad thing. Here in Arizona and especially our area, you have to be realistic over who you could elect. We were thrilled. She seemed like the real thing,” she told VICE News.

But now?

“I’m livid. I can only call her a turncoat,” Dunn said. “I feel betrayed.”

Sinema’s Wednesday vote against changing the filibuster, which kept the 60-vote margin for most major bills and effectively killed Democrats’ efforts to pass voting rights legislation, is the latest in a long line of votes that have enraged and upset some of the people who worked hard to put her in office. Dunn said for her, it was the “last straw.”

VICE News talked to more than a dozen Arizona Democratic activists and former staffers who actively worked to elect Sinema during her 2018 race. Many expressed their frustration not just with her voting record but also with her inaccessibility, her seeming delight at infuriating her party’s base, and her unwillingness to meet. All said that they’d likely vote against her in a primary if she runs in 2024.

Dunn first met Sinema at an event hosted at the home of her friend Toni Denis, who chaired the Yavapai County Democratic Party and now heads the Arizona Federation of Democratic Women. Denis donated more than $3,000 to Sinema in 2018 and says she spent roughly 30 hours a week for months working to elect Sinema and the rest of the Democratic ticket that election.

She’s done with Sinema too.

“I’m crushed that she won’t support doing away with the filibuster, and especially that she won’t explain any of her decisions,” Denis told VICE News on Thursday, saying Sinema’s vote on this and other issues has been a “slap in the face” to those who helped elect her.

“The people who supported her and who did work for her campaign put in a lot of hours in canvassing and getting signatures for her are bitterly disappointed,” she continued.

It’s not just a handful of local progressive activists who are fed up with Sinema, who with their help won a close race in 2018 and became the first Democratic senator elected in the state in more than three decades.

Only 8 percent of Arizona’s registered Democrats held a favorable opinion of Sinema as of Jan. 14, according to a tracking poll from the Democratic firm Civiqs—and that was before she voted to uphold the filibuster this week. Her favorable rating was at 70 percent with Arizona Democrats as recently as the 2020 elections, but it took a nosedive when she voted against raising the federal minimum wage early last year and plunged again when she skipped the Senate vote to create a bipartisan commission to investigate the Jan. 6 Capitol riot (she said she missed it because of a “personal family matter”). Her hesitation about parts of the Build Back Better plan, the vehicle Biden and Democrats are using to try to pass their top legislative priorities, hasn’t helped either.

Some former staffers are frustrated too. They’re glad Sinema’s 2018 defeat of Republican Sen. Martha McSally helped give Democrats Senate control, but they told VICE News they’ve been disappointed with her as a senator.

One former Sinema staffer said she could be “really rough on people” and “likes to have somebody she’s pissed off at” on staff. That wasn’t enough for them to stop supporting her—but her Senate votes have been.

“I certainly don’t think she deserves to be reelected,” said the former staffer, who asked to remain anonymous because of their current job in Democratic politics. “I’m extremely disappointed in her.”

Another former staffer was even harsher in their criticism. They said they went to work for Sinema over two other candidates, and looking back on it, wish they’d taken a different job even though those two other candidates lost that cycle.

“I really wanted to win. But at the end of the day, the win didn’t feel good,” said the former campaign staffer who asked to remain nameless because they could get in trouble at their current job.

“I cannot wait to donate to her primary challenger. There is a running joke that Sinema staffers text each other: ‘That line on the resume gets worse and worse by the day,’” said that staffer. “People need to know she sucks.”

Sinema will almost certainly face a primary in 2024 if she runs again. Rep. Ruben Gallego has been publicly making noises about a bid, and slammed her Wednesday vote. The Primary Sinema Project, a group that launched last summer, has raised $330,000—including $100,000 in just the last week since her filibuster speech.

Some of Sinema’s biggest national backers are done with her too.

EMILY’s List, which backs Democratic women who support abortion rights, spent $1.7 million on her last race and helped funnel much more to her with their fundraising network. But they publicly warned Sinema this week that if she didn’t change her position on the filibuster, they wouldn’t support her anymore. So did NARAL Pro-Choice America, a major abortion rights group.

“We believe the decision by Sen. Sinema is not only a blow to voting rights and our electoral system but also to the work of all of the partners who supported her victory and her constituents who tried to communicate the importance of this bill,” EMILY’s List said in a statement.

Indivisible, the national grassroots Democratic organization, says its volunteers sent a half-million text messages, made a quarter-million calls, and knocked on at least 5,000 doors for Sinema—and that’s not counting their volunteers’ work directly for Sinema’s campaign and the state Democratic Party. They were among the groups pushing hardest for Sinema to change her filibuster position, and their local leaders are furious.

When Indivisible asked its Arizona members this week if they’d support a primary against Sinema, 94 percent of those who responded said yes.

Multiple former supporters also say it’s not just Sinema’s votes that have pissed them off—it’s how she’s conducted herself. Many pointed to her enthusiastic, meme-ready thumbs-down when she voted against raising the minimum wage last May. Others said her decision to give a speech defending the filibuster right before President Biden was set to arrive at the Senate to try to convince Democrats to back him on the carve-out for the voting rights legislation infuriated them.

“I was outraged. It was such an obvious tweak on Biden, a needless show of power in the way where she was obviously trying to humiliate the president,” said Chris Vaaler, who heads Indivisible’s Scottsdale chapter. “It’d been a slow process, a gradual process of just becoming more and more nervous, a feeling of unease that was steadily increasing. But that was when it went over the edge.”

Sinema’s staff point out that she’s been consistent on her support for the filibuster and has long had a centrist voting record. She’s long been a moderate Democrat, joining the Blue Dog Coalition as soon as she won her House seat a decade ago, and this isn’t the first time she’s broken with leadership and backed the GOP on key bills, including some changes to Obamacare and keeping the individual tax cuts passed under President Trump.

She campaigned that way in 2018, too, running immigration ads that frustrated some local activists. But that positioning undoubtedly helped her: She won by two percentage points, even as the much more liberal candidate for governor lost by 14. And to be fair, most other Senate Democrats agreed with Sinema that the filibuster shouldn’t be changed just a few years ago.

"During three terms in the U.S. House, and now in the Senate, Kyrsten has always promised Arizonans she would be an independent voice for the state—not for either political party,” Sinema spokeswoman Hannah Hurley told VICE News. “She’s delivered for Arizonans and has always been honest about where she stands, and has said that different people of good faith can have honest disagreements about policy and strategy, and that honest disagreements are normal."

But she’s never been in the spotlight like this before.

David Lucier said he’s known Sinema for a decade, going back to their work together on a bill to provide in-state tuition to military veterans. He volunteered on Sinema’s race in 2018, then was invited to serve on her veterans’ advisory council. But he grew increasingly frustrated with her stances, and was one of five veterans who resigned in protest from the council in October.

“Personally and professionally I just feel betrayed, like I’ve been stabbed. It’s a horrible, horrible feeling. I still feel badly about it,” he said Thursday. “There is absolutely no trust at this point. She had all the way up until last night to do something, revise her position or compromise. She failed to do it.”

Rep. Lauren Boebert, R-CO, speaks at a news conference held by members of the House Freedom Caucus on Capitol Hill in Washington, July 29, 2021. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Rep. Lauren Boebert, R-CO, speaks at a news conference held by members of the House Freedom Caucus on Capitol Hill in Washington, July 29, 2021. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

The Colorado Republican left the visitors “confused” after a short encounter.

Members of the group, which was meeting with Rep. Tom Suozzi, were wearing yarmulkes, and the person coordinating the group is Orthodox, with a traditional beard.

One witness said the group, along with other members of Congress, was waiting for an elevator. When the doors opened, Boebert stepped out of the elevator and looked the group of visitors “from head to toe,” the witness said. Boebert then asked if they were there to conduct “reconnaissance.”

“When I heard that, I actually turned to the person standing next to me and asked, ‘Did you just hear that?’” a rabbi who was with the group told BuzzFeed News.

“You know, I’m not sure to be offended or not,” the rabbi said. “I was very confused.” The rabbi added that “people are very sensitive” now, especially after what happened in Texas this past weekend, when an armed man held four people hostage at a synagogue.

Boebert told BuzzFeed News that she was referencing the many comments that have been directed at her from Democrats about Capitol tours prior to the Jan. 6 attack, adding that some people present “got it.”

“I saw a large group and made a joke. Sadly when Democrats see the same they demonize my family for a year straight,” she said in a text.

“I’m too short to see anyone’s yarmulkes,” she added.

Suozzi brought the group to the US Capitol to commemorate the 41st anniversary of the end of the Iran hostage crisis. Members of the group have been backing Suozzi’s efforts to recognize the hostages with a Congressional Gold Medal.

"The bottom line is that everyone, especially members of Congress, have to be very, very thoughtful in the language they use,” Suozzi said in a statement about the incident. “Because when you're a member of Congress, you have an important role to play in society. You can't be cavalier in the comments you make especially if they could be perceived as being antisemitic, or discriminatory."

Boebert has repeatedly come under criticism from Democrats and others for her comments in the year she’s been in office. In November, anti-Muslim remarks she directed at Rep. Ilhan Omar led to a flurry of debate among House Democrats over whether or not to formally reprimand her.

She has, at the same time, grown in influence in the right wing of her party. Boebert was tapped as the communications chair of the House Freedom Caucus. In her announcement, she said she’ll “work diligently to make sure the caucus’s message, and the powerful messages of each member, are delivered to the American people.”

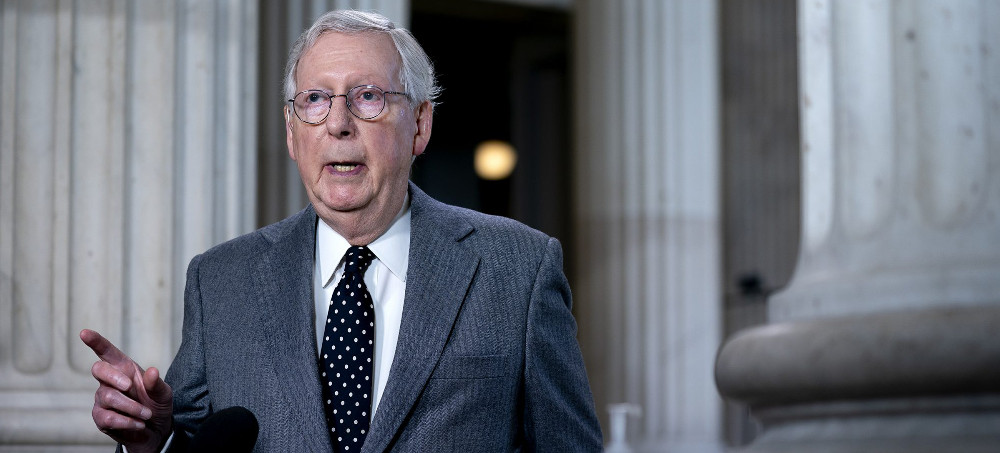

Amid concerns about voting access, Senator Mitch McConnell's remarks were roundly criticized by the Congressional Black Caucus, Democratic lawmakers and others. (photo: Getty)

Amid concerns about voting access, Senator Mitch McConnell's remarks were roundly criticized by the Congressional Black Caucus, Democratic lawmakers and others. (photo: Getty)

ALSO SEE: Three Lessons for the Voting Rights Struggle

From the Latest Senate Setback

Republican Senate minority leader’s comments came after party members blocked voting rights bill and changes to filibuster rule

The Kentucky Republican was speaking after Republican senators once again blocked Democrats’ voting rights legislation on Capitol Hill on Wednesday evening.

Speaking to reporters after the bill failed and the Senate rejected a change to the filibuster rule that could facilitate its passage, McConnell was asked for his message to voters in minority communities who are concerned that voting restrictions being enacted in many states will keep them from the ballot box without new federal laws.

“The concern is misplaced, because if you look at the statistics, African American voters are voting in just as high a percentage as Americans,” McConnell said.

In fact, studies indicate that voting restrictions, like those passed by 19 states in the past year, disproportionately impact voters of color.

Democratic Illinois congressman Bobby Rush swiftly called out McConnell’s comment, saying in a tweet: “African Americans ARE Americans. #MitchPlease”

One of Rush’s Democratic colleagues, Diana DeGette of Colorado, echoed that assessment, describing McConnell’s comment as “disgusting”. “African-American voters ARE AMERICANS … to suggest otherwise is about as racist as it gets,” DeGette said in a tweet.

Former Kentucky state senator Charles Booker, who is campaigning for the US senate against Republican Rand Paul, tweeted: “I am no less American than Mitch McConnell” and also said: “I need you to understand that this is who Mitch McConnell is. Being Black doesn’t make you less of an American, no matter what this craven man thinks.”

Pastor and activist Talbert Swan quipped that he “can’t qwhite put my finger on” what distinction McConnell might be drawing, tweeting: “I wonder what’s the difference he sees between ‘African-American voters’ and ‘Americans.’”

And Malcolm Kenyatta, a Democratic Senate candidate in Pennsylvania, argued that McConnell’s words were not a slip of the tongue but were instead an accurate reflection of the Republican party’s mindset toward Black voters.

“Mitch McConnell’s comments suggesting African Americans aren’t fully American wasn’t a Freudian slip – it was a dog whistle. The same one he has blown for years,” Kenyatta said.

ICE Field Office Director, Enforcement and Removal Operations, David Marin and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's (ICE) Fugitive Operations team make an arrest at a home in Paramount, California, March 1, 2020. (photo: Lucy Nicholson/Reuters)

ICE Field Office Director, Enforcement and Removal Operations, David Marin and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's (ICE) Fugitive Operations team make an arrest at a home in Paramount, California, March 1, 2020. (photo: Lucy Nicholson/Reuters)

But so far, some immigrants and their advocates say, the reality is falling short of the administration's rhetoric.

"We're a year in, and it's not working," says Inna Simakovsky, an immigration lawyer in Columbus, Ohio, in an interview. "I just want them to actually do the right thing, and do what they promised."

As the Biden administration approaches its one-year mark, there's mounting frustration among immigrant advocates at what they see as a growing list of broken promises.

Ambitious plans to overhaul the immigration system have stalled. Trump-era restrictions on asylum are still in place at the southern border — including the public health order known as Title 42, which allows authorities to quickly expel most migrants, and the return of a policy that forces some asylum-seekers to "Remain In Mexico" until their immigration court hearings. And the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) pulled out of settlement talks over financial compensation for families that were forcibly separated during the Trump administration.

The Biden administration can, however, point to some victories — including detailed guidelines laying out who should be a priority for arrest and deportation, and who should not.

"The guidance recognizes the incontrovertible fact ... that the majority of undocumented individuals have contributed so significantly to our communities across the country for years," Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas told NPR last year.

But immigration lawyers in some parts of the country say the execution of that guidance is not living up to expectations.

"If there's anyone that deserves prosecutorial discretion, this is the case"

When Simakovsky heard about the new enforcement guidelines, she thought immediately about one of her clients in Columbus. Carol came to Ohio from Africa on a student visa more than 20 years ago, and never left. She asked us not to use her last name, or say where she's from, because her asylum case is still pending.

Carol and her husband own a house and pay their taxes. She works in banking; her husband is a nurse. They have four kids, all U.S. citizens.

But Carol knows that their lives in the U.S. are precarious.

"If my kids are playing sports, I'll be sitting in a corner crying because I don't know if next year I'll see him play," she says in an interview. "So it's like you live day by day. You don't know what will happen."

On paper, Simakovsky says Carol and her husband are exactly the kind of people that the enforcement guidance from Immigration and Customs Enforcement should help: They have no criminal records, long-standing ties to their community, and a potential pathway to permanent legal status through their children. So Simakovsky wrote to ICE requesting what's known as prosecutorial discretion — when prosecutors agree to put a case on hold, or drop it altogether.

The answer was no.

"It's crazy," Simakovsky says. "If there's anyone that deserves prosecutorial discretion, this is the case."

ICE did not respond to a request for comment on Carol's case.

Officials say immigration enforcement guidance is working as intended but advocates say not at all

Biden administration officials insist that the immigration enforcement guidance is working as intended. Immigration arrests in the interior of the country are down significantly compared to the Trump or Obama administrations, while the number of immigrants in ICE detention is relatively low by recent standards.

In a statement, an agency spokesperson said the new guidance is intended to "better focus the Department's resources on the apprehension and removal of noncitizens who are a threat to our national security, public safety, and border security and advance the interests of justice by ensuring a case-by-case assessment of whether an individual poses a threat. ICE's attorneys are directed to consider the exercise of discretion, consistent with this guidance."

ICE says in a statement that it has received roughly 47,000 requests for prosecutorial discretion so far — and that it has granted 70% of those requests. But immigration lawyers around the country remain skeptical.

"The language coming from Washington is not at all the actual practice that we're experiencing in Boston," says Michael Kaplan, a lawyer at the firm Rubin Pomerleau.

Kaplan represents two Central American women who won their asylum cases in immigration court. When the new guidance came out, Kaplan says he immediately asked the ICE office in Boston to drop its appeals in their cases. Kaplan says he heard nothing back for months, until ICE eventually declined his request.

"Maybe I'm naïve. I still have hope that maybe I'll win the lottery with it, and be able to to help one of my clients in that way," Kaplan tells NPR. "But some attorneys are really finding it pointless."

Other immigration lawyers say it's still too early to draw conclusions.

"We have heard from some practitioners that they are getting requests approved but many are still running into obstacles with ICE even for cases that seem to fit the guidance to a T," says Jen Whitlock, policy counsel for the American Immigration Lawyers Association. "It seems to depend a lot on geographical jurisdiction."

Immigration lawyers across the country are confused about how the new guidance is being applied

In interviews, half a dozen immigration lawyers from different parts of the country expressed confusion and disappointment about how the new guidance is being applied. Several suggested that ICE staff hired during the Trump administration, which took a harder line on interior enforcement, could be undermining the new policy.

But a senior Biden administration official disputed that theory. In a background interview, the official said it was inevitable that immigration lawyers would be frustrated with the outcome in a handful of cases. ICE has more than 1200 lawyers on staff. The official says they are very busy, and it might take time for all of them to get up to speed on the new policy.

Still, some immigrants say they can't afford to wait.

"My life will end when I return to Mexico," says Miguel Araujo in Spanish through an interpreter. Araujo says he was forced to flee Mexico more than 40 years ago, because his work exposing collusion between the government and drug cartels made him a target.

"They want me in Mexico so they can assassinate me, the same way they assassinated my brother, and the same way they have assassinated hundreds of activists in all parts of the country," he says.

Araujo's case for prosecutorial discretion isn't perfect. There's a decades-old drug conviction in his past. And the government of Mexico has made it clear that they want him back, filing what's known as a "Red Notice" with INTERPOL seeking his return.

But Araujo's lawyers insist he is no threat to public safety. They describe him as a well-known journalist and restaurant owner in Northern California, where he's spent more than half of his life.

"There's nothing shameful or wrong about taking a second look at the case, and that didn't happen here," says Francisco Ugarte, a lawyer in the San Francisco Public Defender's Office, which is representing Araujo. "When we see the way the government is litigating these cases ... you have to call into question whether they're fulfilling the promises of this current administration," Ugarte says.

Araujo, who is 73, says he can't understand why the Biden administration is still fighting to deport him.

"It's very confusing," he says. "On one hand, they want to be our friends, and extend the hand of a friend. And with the other, they're beating us down, and they're sending us back."

A man inspects the wreckage of a building after it was damaged in Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, in Sanaa, Yemen, Tuesday, Jan. 18, 2022. (photo: Hani Mohammed/AP)

A man inspects the wreckage of a building after it was damaged in Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, in Sanaa, Yemen, Tuesday, Jan. 18, 2022. (photo: Hani Mohammed/AP)

At least 100 people reported killed and injured in attack on facility in Saada as Saudi-coalition intensifies air strikes

"There are more than 100 killed and injured... the numbers are going up," said Basheer Omar, spokesperson for the ICRC in Yemen, citing hospital figures.

Gruesome scenes came to light in Saada, heartland of the Houthi movement, as rescue workers pulled bodies from destroyed prison buildings and piled up mangled corpses, according to footage released by the rebels.

The Saudi-led military coalition has intensified air strikes on what it says are Houthi military targets after the rebels conducted an unprecedented air assault on coalition member the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on Monday, as well as further cross-border missile and drone launches at Saudi cities.

Rescue workers were still pulling bodies out of the rubble around midday following the dawn strike in northwestern Yemen, which could end up being the worst since the 8 October 2016 Saudi-led bombing of a Sanaa funeral.

A Reuters witness said several of those killed were African migrants.

Further south in Hodeidah, video footage showed bodies in the rubble and dazed survivors after an air attack from the Saudi-led pro-government coalition took out a telecommunications hub. Yemen suffered a nationwide internet blackout, a web monitor said.

A statement from Save the Children said three children and more than 60 adults were killed in air strikes in Yemen on Friday. It gave no further details.

Citing even higher figures than the ICRC, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) said Saada's hospital had received about 200 people wounded in the prison attack and "they are so overwhelmed that they cannot take any more patients".

"There are many bodies still at the scene of the air strike, many missing people," Ahmed Mahat, MSF head of mission in Yemen, said in a statement. "It is impossible to know how many people have been killed. It seems to have been a horrific act of violence."

Warnings of reprisals

Saudi Arabia leads a western-backed military coalition that intervened in Yemen in 2015 to restore the government of President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi, which was kicked out of power by the Iran-aligned Houthis in 2014.

UAE presidential adviser Anwar Gargash warned the country would exercise its right to defend itself after Monday's Abu Dhabi attack, which was claimed by the Houthis.

"The Emirates have the legal and moral right to defend their lands, population and sovereignty, and will exercise this right to defend themselves and prevent terrorist acts pursued by the Houthi group," he told US special envoy Hans Grundberg, according to the official WAM news agency.

Yemen's war has been a catastrophe for millions of its citizens, who have fled their homes, with many close to famine in what the UN calls the world's worst humanitarian crisis.

The UN has estimated the war killed 377,000 people by the end of 2021, both directly and indirectly through hunger and disease.

Chemicals created to kill agricultural pests are being sprayed by aircraft into native forest areas. (photo: iStock)

Chemicals created to kill agricultural pests are being sprayed by aircraft into native forest areas. (photo: iStock)

According to IBAMA, some pesticides work as defoliants. The dispersion of those chemicals over native forest is the initial stage of deforestation, causing the death of leaves — and a good part of the trees. The material is burned and surviving trees are removed with chainsaws and tractors.

“Although human-induced forest degradation takes a few years to happen, the process is advantageous to criminals because chances of being caught are very low. We can only see the damage when the clearing is already formed,” notes an IBAMA official who spoke with Mongabay on the condition of anonymity. “A dead forest is easier to remove than a living one. Certain (not all of them) pesticides practically leave only big trees standing.”

In the next step, the offenders drop grass seeds by aircraft. “This is the great bargaining chip for land grabbing. In order for illegal land to be sold as a ‘farm in formation,’ the soil must be covered with grass,” added the agent.

Glyphosate, carbosulfan (prohibited on aerial spraying) and 2,4-D (a component of Agent Orange, used massively in the Vietnam War and which still results in cases of birth defects in the country) were some of the pesticides found by the environmental agency in clearings in the Arc of Deforestation (the Legal Amazon area where the agricultural frontier advances towards the forest), according to a survey by Repórter Brasil and Agência Pública.

“Causing forest degradation through pesticides is a major aggression to the environment. The 2,4D herbicide, for instance, is capable of killing large trees, and the carbosulfan insecticide is highly toxic. Animals will eat poisoned leaves and fruits from the forest [while the vegetation dies]. And it’s very dangerous for anyone nearby when pesticides are thrown,” said Eduardo Malta, a biologist at the NGO Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), in an interview.

In an IBAMA video sent to Mongabay, two inspectors show a rural property on which they detected, during an overflight, an area of about two hectares (4.9 acres) with dry, brownish vegetation. Upon landing at the site, they found dozens of empty gallons of the Planador XT herbicide — which had been dumped into the area by helicopter at the owner’s behest.

“Although that product is authorized to be applied by agricultural aircraft, its use is prohibited in native forests,” states one of the IBAMA agents in the video. “In addition, the containers [thrown on the soil] were not washed or disposed of properly, and the rains could end up transporting the residues. Adults, children [of farm workers] and animals live on the site. Everyone has their health put at risk.”

Cattle farms buying pesticides — what for?

As the IBAMA video shows, not only do land grabbers release pesticides to deforest, but farmers also do so on their own properties. Faced with the increased number of cases, IBAMA began to map those areas through INPE’s (Brazilian space agency) forest degradation alert system. When cross-referencing the data, the environmental agency found that many of the clearings were located on farms that were purchasing pesticides, mainly in the state of Mato Grosso.

Such properties, however, were livestock farms and not agricultural ones, so it did not make sense to purchase those products.

“The criminals noticed that forest degradation was not our priority because we only arrived at those places much later, when the clearings were already formed. So they began practicing more of those,” the IBAMA representative told Mongabay. “The truth is we were more focused on fighting clear-cut deforestation due to the increasing rates in recent years. It was a learning experience for us.”

The reduced number of field agents to cover all six Brazilian biomes, and not just in the deforestation area, is a big problem. In 2019 they were only 591, which is 55% less than compared to 2010 (when it was 1,311).

2010 was the last year that IBAMA opened new vacancies for enforcement agents.

“It is unfortunate the irresponsibility of those people towards human life and the environment. Pesticides were not made for that purpose, there are no scientific studies on the consequences of dumping those products in the native forest, and the effects on living beings, water and soil,” said the agent. “In addition to IBAMA, Embrapa [a public agricultural research company linked to the Ministry of Agriculture] and the Ministry of the Environment, among others, must participate in the effort of raising awareness and educating rural producers and the population. The agency alone in this battle is an inglorious fight.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611