Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

If presidents do not get to replace justices in an election year, then Coney Barrett’s confirmation is illegitimate; if presidents do, then Gorsuch’s is illegitimate. You can’t have it both ways

It appears that Justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett share these worries. In separate remarks this month, both justices sought to assure the public that, in Coney Barrett’s words, “this court is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks”. Thomas said much the same, seeking to disabuse his listeners of the belief that justices “are just always going right to [their] personal preference”.

Triggering the justices’ concerns was the withering criticism that has been directed at the court’s recent decision to leave in place, at least for now, a Texas law that turns ordinary citizens into de facto bounty hunters empowered to sue anyone who performs or “aids and abets” an abortion for a woman past her sixth week of pregnancy. The Texas law cannot be squared with the court’s ruling in Planned Parenthood, which recognized that a “woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy before viability … is a rule of law and a component of liberty we cannot renounce”. To renounce that principle, the court warned, would cause “profound and unnecessary damage to the Court’s legitimacy, and to the Nation’s commitment to the rule of law”. But that is precisely what the court did in letting Texas’s transparently unconstitutional law take legal effect.

But far from recognizing or examining their own role in contributing to the erosion of the court’s legitimacy, the two justices turned to other precincts to assign blame. It’s the media, Thomas whined, that are “destroying our institutions” – this from a justice who dissented from the court’s refusal to hear Trump’s challenge to a Pennsylvania state court decision that extended the deadline for the receipt of mail-in ballots by three days. Thomas acknowledged that the volume of mail-ins at stake had no material bearing on the outcome of the Pennsylvania race; all the same, he was prepared – in a stunning display of either partisanship or tone-deafness – to have the supreme court, scant weeks after the 6 January insurrection, offer tacit support to Trump’s attack on the 2020 election results. And, in now blaming the media for the court’s self-inflicted wounds, Thomas is effectively echoing Trump’s toxic rhetoric about “fake news”. Who is the institution-destroyer here?

Alas, Justice Coney Barrett joined Thomas in attacking the press. The media, she charged, makes decisions such as the Texas case “seem results-oriented”. It is worth noting that the justice made her remarks at the McConnell Center at the University of Louisville, with Senator Mitch McConnell, the center’s namesake, in attendance. It was McConnell, of course, who in the wake of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death six weeks before the 2020 election, pushed through Coney Barrett’s nomination, in transparent violation of the very justification he had offered four years earlier to deny President Obama the right to name a justice to fill a court vacancy that ultimately went to Neil Gorsuch. That McConnell’s cynical manipulation of the rules was designed to compose a court that would produce dependably conservative results appears lost on Coney Barrett. Indeed, it was her vote that was determinative in the Texas case. Had Ginsburg still been on the court, the decision would have gone 5-4 the other way. McConnell secured the results he wanted.

If Coney Barrett were genuinely concerned with promoting the court’s legitimacy, she might consider resigning. Or rather, she and Gorsuch might agree to flip a coin to decide who should leave the court. If presidents do not get to replace justices in an election year, then Coney Barrett’s confirmation is illegitimate; and if presidents do get to replace, then Gorsuch’s confirmation must be illegitimate. You can’t have it both ways – not if you believe that the composition of the court should be the product of a principled process.

Coney Barrett appears to willfully overlook the fact that she has been elevated to a rarefied position through a tarnished process that will taint all decisions in which her vote plays a crucial role. And just as we might hope that a person who, through no fault of their own, has come into possession of a good not rightfully theirs, would return that object, Coney Barrett and Gorsuch could do the right thing for the nation by agreeing that one of them should step down.

Clearly, this isn’t going to happen. Yet it would powerfully bolster the legitimacy of a court the very composition of which smacks of illegitimacy.

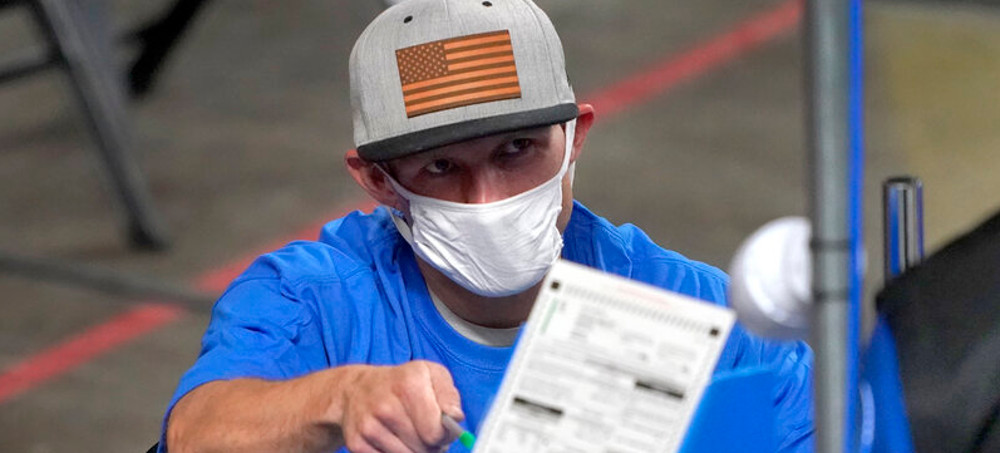

Ballots from the 2020 presidential election are examined in May as part of a controversial recount of the Maricopa County, Arizona, vote. (photo: Matt York/AP)

Ballots from the 2020 presidential election are examined in May as part of a controversial recount of the Maricopa County, Arizona, vote. (photo: Matt York/AP)

According to a draft copy of the findings obtained by NPR member station KJZZ, a hand recount of the nearly 2.1 million ballots cast in Maricopa County hewed closely to the official canvass of the results approved by county leaders.

In fact, the new hand recount for Biden exceeded the county's tally by 99 votes, while Trump received 261 fewer votes than the official results.

Randy Pullen, a spokesman for the election review, confirmed the validity of the draft. "It's not the final report, but it's close," he said Thursday.

The draft copy was obtained by KJZZ from a source familiar with the review less than 24 hours before a scheduled presentation in the Arizona state Senate. The contractors hired to conduct the review will explain their findings.

Trump and his allies have latched on to the so-called Arizona audit as evidence of their wide-ranging and baseless claims that the 2020 election was rigged.

Republicans in other states have visited the election review in Maricopa County, and initiated similar investigations in their states, despite a lack of evidence of widespread fraud or other issues with last year's election.

But the Maricopa report itself throws cold water on the grandest claims of fraud.

"What has been found is both encouraging and alarming," the draft states. "On the positive side there were no substantial differences between the hand count of the ballots provided and the official canvass results for the county."

Pullen confirmed that the hand recount was "relatively close" to the official tally.

"Was there massive fraud or anything? It doesn't look like it," he added.

However, the draft report raises concerns about the county's elections systems and record-keeping and accuses Maricopa County officials of stonewalling their effort to perform "a complete audit."

"Had Maricopa County chosen to cooperate with the audit, the majority of these obstacles would have easily been overcome," the report states.

Senate President Karen Fann and Sen. Warren Petersen, both Republicans, eventually issued subpoenas to obtain the ballots and voting materials needed for the investigation.

Pullen said other reports that will be presented in detail Friday have not been leaked and that "anomalies" found in voting records are vast enough to cast doubt on the final vote count — despite the hand recount's confirmation of the result.

Maricopa County supervisors have refused to aid the contractors hired by Fann, accusing them of bias and inexperience after errant claims were made about the county's election.

"The contractors hired by the Senate president are not auditors, and they are not certified by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission," Maricopa County Board Chair Jack Sellers, a Republican, said in May. "It's clearer by the day: The people hired by the Senate are in way over their heads. This is not funny; this is dangerous."

County officials responded on Twitter to the release of the draft copy of the report, writing that while it affirmed the results, "the report is also littered with errors & faulty conclusions about how Maricopa County conducted the 2020 General Election."

The county's criticism of the reviewers is a sentiment shared by election experts across the country who've warned that any findings by lead contractor Cyber Ninjas — a Florida-based cybersecurity firm that had no prior experience in elections and is led by a CEO who has embraced conspiracies of election fraud — can't be trusted. The same goes for subcontractors conducting other aspects of the Senate's review, they say.

"This partisan effort in Arizona appears to be ending the same as it begun — highly biased, incompetent individuals running the process, delay after delay after delay, and very importantly, completely un-transparent," David Becker, founder of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, said earlier Thursday.

The contractors involved in the review and Arizona state Senate Republicans have drawn the scrutiny of the U.S. Justice Department, made errant claims about illegitimate votes that were promptly debunked, and disclosed that prominent Trump supporters engaged in efforts to delegitimize the former president's defeat provided millions of dollars to fund the process.

U.S. troops in Afghanistan. (photo: Getty)

U.S. troops in Afghanistan. (photo: Getty)

Everyone wants you to do it. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The World Health Organization. Your mother. Even Popeye. It’s good for preventing everything from the common cold to Covid-19. And it only takes about 20 seconds.

Americans are washing their hands more than ever. It’s one of the few positive results of a pandemic that has now killed 1 in every 500 people in this country.

Washing with soap and water will remove germs and prevent their spread. It’s incredibly effective. But soap and water have their limitations. There are some things they just won’t wash away.

Recently, Matthieu Aikins and his colleagues at the New York Times reported on a U.S. drone strike aimed at an ISIS-K suicide bomber that instead killed Zemari Ahmadi, a longtime worker for a U.S. aid group, and nine other people, six of them under 11 years old. “Neighbors and an Afghan health official confirmed that bodies of children were removed from the site,” wrote Aikins. “They said the blast had shredded most of the victims; fragments of human remains were seen inside and around the compound the next day by a reporter, including blood and flesh splattered on interior walls and ceilings.”

You can try to wash away “blood and flesh splattered on interior walls and ceilings” with soap and water. You can try using bleach. Cleaning gore off walls and ceilings is tough enough, but getting blood off your hands is infinitely more difficult.

As an American whose tax dollars went into buying that MQ-9 Reaper drone and the missile it fired, I can attest that no amount of scrubbing has removed Zemari Ahmadi’s blood from my hands. It’s going to be there forever. Nor has my hand-washing routine wiped clean the blood of his three children, Zamir, 20, Faisal, 16, and Farzad, 10; Ahmadi’s cousin Naser, 30; the children of Ahmadi’s brother Romal: Arwin, 7, Benyamin, 6, and Hayat, 2; and two 3-year-old girls, Malika and Somaya.

Today, TomDispatch regular Kelly Denton-Borhaug, an expert on violence and religion, delves deep into the complex questions that surround morality, accountability, and America’s last 20 years of war. What happens to a people when violence is done in their name? What does it do to the soul of a nation and the souls of its citizens? And ultimately, who is to blame?

Washing your hands might save you from Covid-19, but it can’t wipe away violence done in your name. Conflicts may end, but complicity remains.

President Biden formally announced the end of the Afghan War, while at the same time threatening future violence. “We will maintain the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan,” he said. “We have what’s called over-the-horizon capabilities… We’ve shown that capacity just in the last week. We struck ISIS-K remotely, days after they murdered 13 of our service members and dozens of innocent Afghans.”

ISIS-K had, indeed, slain “innocent Afghans” in a prior bombing. But Biden had killed innocent Afghans, too. The strike he referenced is the one that killed Zemari Ahmadi and all those children. Soap and water won’t change that. It’s a stain on America’s soul that neither Joe Biden nor I can wash away.

-Tom Engelhardt, TomDispatch

The heart-wrenching last days of that war amounted to a cautionary tale about the nature of violence and the difficulty Americans have honestly facing their own version of it. As chaos descended on Kabul, and as the Biden administration’s efforts to evacuate as many Afghans and Americans as possible were stretched to the limit, one more paroxysm of senseless violence took center stage.

A suicide bomber sent by the Islamic State group ISIS-K struck Kabul’s airport, killing and maiming Afghans as well as American troops. The response? More violence as a Hellfire missile from an American drone supposedly took aim at a member of the terror group responsible. The U.S. military announced that its drone assassination had “prevented another suicide attack,” but the missile actually killed 10 members of one family, seven of them children, and no terrorists at all. Later, the Pentagon admitted its “mistaken judgment” and called the killings “a horrible tragedy of war.”

How to react? Most Americans seemed oblivious to what had happened. Such was the pattern of the last decades, as most of us ignored the staggering number of civilian casualties from our country’s bombing and droning of Afghanistan. As for the rest of us, well, what else could you do but hold your head and cry?

In fact, those final events in Afghanistan crystallized an important truth about our post-9/11 history: the madness of making war the primary method for dealing with potential global conflict and what’s still called “national security.” Throughout these years, our leaders and citizens alike promoted delusional dreams of violence (and glory), while minimizing or denying the nature of that violence and its grim impact on everyone touched by it.

With respect to the parables of the New Testament gospels, Jesus of Nazareth is reported to have said, “Those who have ears, let them hear.” In this case, however, Americans seem unable to listen.

Parables are compact, supposedly simple stories that, upon closer examination, illustrate profound spiritual and moral truths. But too few in this country have absorbed the truth about the misplaced violence that characterized our occupation of Afghanistan. Our culture remained both remarkably naïve and blindly arrogant when it came to widespread assumptions about our violent acts in the world that only surged thanks to the further militarization of this society and the wars we never stopped fighting.

The Costs of War in Well-Being, Money, and Morality

Over the last 20 years, according to a report from the National Priorities Project, the U.S. dedicated $21 trillion to an obsessive militarization of this country and to the post-9/11 wars that went with it. Nearly one million people died in the violence, while at least 38 million were displaced. Meanwhile, more than a million American veterans of those conflicts came home with “significant disabilities.” Deployment abroad brought not just death but devastation to all-too-many military families. Female spouses too often bore the brunt of care for returning service members whose needs were unfathomably wrenching. The maltreatment of children in military families “far outpaced the rates among non-military families” after increasing deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq and children of deployed parents showed “high levels of sadness.”

Many analysts have pointed to the culture of lies and self-deceit that characterized these years. American leaders, political and military, lost their own moral grounding and were dishonest with the citizenry they theoretically represented. But we citizens also share in that culpability. Andrew Bacevich recently asked why the American people didn’t hold their leaders to a more stringent accounting of the wars of the last 20 years. Why were Americans so willing to go along with the unremitting violence of those conflicts year after year, despite failure after failure? What he called the “Indispensable Nation Syndrome” was, he suggested, at least partially to blame — a belief in American exceptionalism, in our unique power to know what’s best for the world and grasp what the future holds in ways other nations and people couldn’t.

In the post-9/11 period, such a conviction mixed lethally with a deepening commitment to violence as the indispensable way to preserve what was best about this country, while fending off imagined threats of every sort. Americans came to believe ever more deeply, ever more thoughtlessly, in violence as a tool that could be successfully used however this country’s leaders saw fit.

The unending violence of our war culture became a kind of security blanket, money in the bank. Few protested the outlandish Pentagon budgets overwhelmingly approved by Congress each year, even as defeats in distant lands multiplied. Violence would protect us; it would save us. We couldn’t stockpile enough of it, or the weapons that made it possible, or use it more liberally around the globe — and increasingly at home as well. Such a deep, if remarkably unexamined, belief in the efficacy of violence also served to legitimate our wars, even as it helped conceal their true beneficiaries, the corporate weapons producers, those titans of the military-congressional-industrial complex.

As it happens, however, violence isn’t a simple tool or clothing you can simply take off and set aside once you’ve finished the job. Just listen to morally injured military service members to understand how deep and lasting violence turns out to be — and how much harder it is to control than people imagine. Once you’ve wrapped your country in its banner, there’s no way to keep its barbs from piercing your own skin, its poison from dripping into your soul.

Canaries in the Coal Mine of War, American-Style

Listening intently to the voices of active-duty service members and veterans can cut through the American attachment to violence in these years, for they’ve experienced its costs and carried its burden in deeply personal ways. Think of them as the all-too-well-armed canaries in the coal mine of our post-9/11 wars, taking in and choking on the toxicity of the violence they were ordered to mete out in distant lands. Their moral injuries expose the fantasy of “using violence cleanly” as wishful thinking, a chimera.

Take Daniel Hale who, while serving in the Air Force, participated in America’s drone-assassination program. Once out of the service, his moral compass eventually compelled him to leak classified information about drone warfare to a reporter and speak out against the drone brutality and inhumanity he had witnessed and helped perpetrate. (As the Intercept reported, during five months of one operation in Afghanistan, “nearly 90% of the people killed in airstrikes were not the intended targets.”)

Convicted of violating the Espionage Act and given 45 months in prison, he wrote, in a letter to the judge who sentenced him, “Your Honor, the truest truism that I’ve come to understand about the nature of war is that war is trauma. I believe that any person either called upon or coerced to participate in war against their fellow man is promised to be exposed to some form of trauma. In that way, no soldier blessed to have returned home from war does so uninjured.” Having agonized about “the undeniable cruelties” he perpetrated, though he attempted to “hold his conscience at bay,” he eventually found that it all came “roaring back to life.”

Or listen to the voice of former Army reservist and CIA analyst Matt Zeller. Having grown up in a family steeped in the American military tradition and only 19 years old on September 11, 2001, he felt “obligated” to do something for his country and signed up. “I bought into it,” he would later say. “I really believed we could make a difference. And it turns out… you don’t come back the same person. I wasn’t prepared for any of that. And I don’t think you really can be.” Describing his post-service efforts to assist Afghans “endangered by their work with the United States” who were fleeing the country, he said, “I feel like this is atoning for all the shit that I did previously.”

Such voices disrupt the dominant narrative of the post-9/11 era, the unshakeable belief of our military and political leaders (and perhaps even of most Americans) that committing violence globally for two decades in response to that one day of bloody attacks on this country would somehow pay off and, while underway, could be successfully contained, distanced, and controlled. There was a deep conviction that, through such violence, we could purchase the world we wanted (and not just the weapons the military-industrial complex wanted us to pay for). Such was the height of American naïveté.

The Inequality and Inhumanity of Violence

Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung has defined violence as an “avoidable assault [on] basic human needs and more generally [on] life.” But how many Americans in these years ever seriously considered the possibility that the violence of war could be avoided? Instead, in response to that one day of terrible violence in our own land, perpetual conflict and perpetual violence became the American way of life in the world, and the consequences at home and abroad couldn’t have been uglier.

Who bothered to consider other avenues of response in the wake of 9/11? The U.S. invaded Afghanistan five weeks after that day, while the Bush administration was already preparing the way for a future invasion of Iraq (a country which had nothing whatsoever to do with 9/11). I’ll never forget the confusion, shock, and fear in the early weeks after those attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The world was grieving with us, but the dominant urge for violent revenge took shape with breathtaking speed, so quickly that it all seemed the natural course of events. Such is the nature of violence. Once it’s built into the structures of human society and government planning, it all too often takes precedence over any other possible course of action whenever conflict or danger arises. “There’s no other choice,” people say and critical thinking shuts down.

We in the United States have yet to truly face the personal as well as national costs of the violence that was so instantly woven into the fabric of our response to 9/11. Within a few days, for instance, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was already talking about a global war on terror targeting 60 countries! Most Americans blithely believed that we could strike in such a fashion without being truly affected ourselves. People generally failed to consider how such a recourse to endless violence would conflict, morally speaking, with the nation’s own deepest values.

But philosophers know that such violence almost invariably turns out to be grounded in inequality and so sharply conflicts with this country’s most basic values, especially the idea that human beings are equal. To act violently against the other, people must believe that the object of violence is somehow less worthy, of less value than themselves. In these years, they had to believe that the endless targets of American violence, like those seven dead children in Kabul, not to speak of the future lives and psychic well-being of the soldiers who were sent to deliver it, didn’t truly matter. They were all “expendable.”

No wonder military training always includes a process of being schooled in dehumanizing others. Otherwise, most people just won’t commit violence in that fashion. The sharp assault on their own values, their own humanity, is too great.

The commemorations of the 20th anniversary of 9/11 spotlighted the limits of the world that two decades of such wars have embedded in our national soul. With rare exceptions, there was a disparity when it came to grief. Countless reports mourned the victims and first responders who died here that day, but few were the ones who extended remembrance and grief to the hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions who have died in our wars in distant lands ever since. Where was the grief for them? Where was the sense of regret or introspection about what 20 years of unmitigated violence has wrought around the world and what it has undoubtedly changed in the moral character of this country itself?

For, believe me, all of us have been impacted morally by our government’s insistent attachment to violence. It’s helped destabilize our own core humanity, its toxicity penetrating all too deeply into the soul of the nation.

Recently, I was asked whether I agreed or disagreed with the statement, “I can be trained to kill and participate in killing and still be a good person.”

As a theologian, an American, and a human being, I find myself filled with dread when I attempt to sort this out. One thing I do know, though. I may be a civilian, but along with the members of the U.S. military, I can’t escape sharing complicity in the killing that’s gone on in my nation’s name, in that war on terror that became a war of terror. I remain part of the group that committed those crimes over so many seemingly endless years and that truth weighs ever more heavily on my conscience.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Kelly Denton-Borhaug, a TomDispatch regular, has long been investigating how religion and violence collide in American war-culture. She teaches in the global religions department at Moravian University. She is the author of two books, U.S. War-Culture, Sacrifice and Salvation and, more recently, And Then Your Soul is Gone: Moral Injury and U.S. War-Culture.

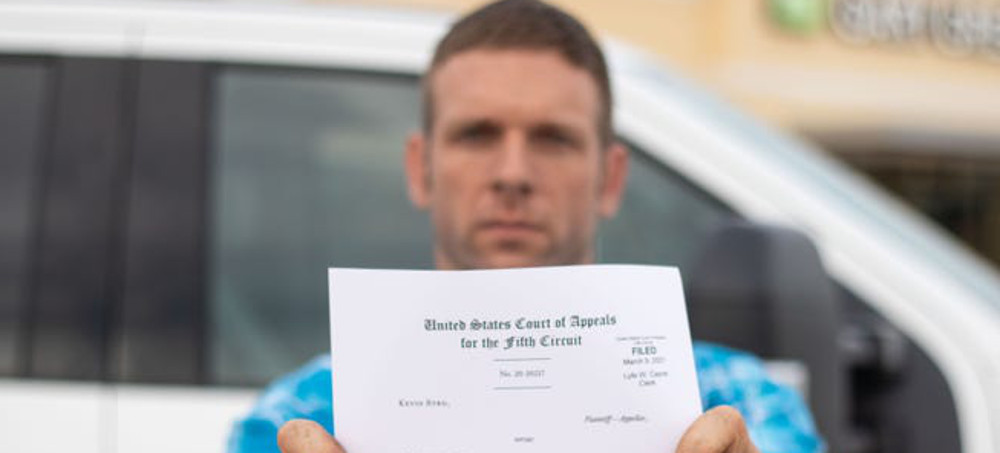

Kevin Byrd sued Ray Lamb, a Department of Homeland Security officer, for violating his Fourth Amendment rights by threatening him with a gun and unlawfully detaining him. (photo: AP)

Kevin Byrd sued Ray Lamb, a Department of Homeland Security officer, for violating his Fourth Amendment rights by threatening him with a gun and unlawfully detaining him. (photo: AP)

Byrd had gone to the bar early in the morning on Feb. 2, 2019, to find more information about a car crash that left his former girlfriend – and the mother of his child – in the hospital.

Byrd says that as he tried to leave the parking lot, agent Ray Lamb, the father of a driver involved in the car accident, jumped out of a truck with a gun in his hand. According to a lawsuit that Byrd would later file, Lamb attempted to smash his car window and threatened to "blow his head off.”

“I thought I was going to lose my life,” Byrd said.

Now, Byrd's odyssey has taken him all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in a case that challenges the legal protections that shield federal law enforcement officers from civil liability. The court will soon decide whether it will hear Byrd's case.

Violating your civil rights

Some lower courts in recent years have given federal law enforcement officers legal immunity from lawsuits that's nearly absolute, even when they violate people’s rights in the most egregious ways.

Byrd filed a federal suit in August 2019, asserting that there was “no legal basis whatsoever” for Lamb “to hold him at gunpoint.”

Byrd was right.

Lamb countered that Byrd’s “allegations consist of mere words, scratches on a window and standing in front of a car,” which do not rise to a “constitutional claim.”

A federal judge in Houston didn’t buy Lamb’s defense and refused to grant the Homeland Security agent qualified immunity. But Lamb appealed, and the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals threw out Byrd’s case. The court said it did not need to address qualified immunity, saying that because Lamb was a federal agent, Byrd could not sue him at all.

Hold federal officers accountable

Byrd is now asking the Supreme Court to review his case and to ensure that lower courts hold federal law enforcement officers accountable when they violate citizens’ rights.

Qualified immunity makes it difficult to win civil damages against local and state police. It’s even tougher to sue any of the approximately 130,000 federal agents working for the FBI, Homeland Security and other agencies.

A 1988 law prohibits suing federal police in state courts. And while the Supreme Court created an avenue to sue in federal court in 1971, that ruling has been weakened so much in recent years by a more conservative Supreme Court that it is almost meaningless in some of the nation’s 12 federal circuits.

When the 5th Circuit threw out Byrd’s case, one of the judges, Don Willett, wrote that he had to go along with the ruling because of Supreme Court precedents.

Nonetheless, Willett, nominated by former President Donald Trump and confirmed by a Republican-led Senate, criticized the Supreme Court’s direction on this issue, saying that “private citizens who are brutalized – even killed – by rogue federal officers can find little solace” in those precedents.

Each of the federal circuit courts interprets prior high court rulings in its own way. In several, judges have shown more common sense, allowing citizens to find a remedy when a federal cop violates their rights.

But citizens in the 5th Circuit, covering Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi, and in the 8th Circuit, which covers seven states running south from Minnesota and North Dakota, are barred from doing so.

As Willett put it, in some places “federal officials operate in something resembling a Constitution-free zone.”

In this country, your constitutional rights should not depend on where you live. Nor should police officers, including those who wear a federal badge, be above the law.

Police reforms in Congress are at an impasse, and even if they are revived, none addresses this important issue. It’s now up to the Supreme Court to protect Americans from police who violate their rights.

The justices need to send a clear message: There's no place in the United States for a Constitution-free zone.

Created in 2018, the Our Black Girls website centers the stories of missing Black girls and women. (photo: Ourblackgirls.com)

Created in 2018, the Our Black Girls website centers the stories of missing Black girls and women. (photo: Ourblackgirls.com)

A journalist in California is doing what she can to try to change that, by telling as many of their stories as she can — and hopefully helping them get the justice they deserve.

Our Black Girls centers on the often-untold stories of Black girls and women who have gone missing or, in some cases, were found dead under mysterious circumstances. Launched by journalist and activist Erika Marie Rivers in 2018, the website is a one-woman show: Rivers spends her nights combing missing persons databases, archived news footage, old articles and whatever other information she can find to piece together these stories. And she does it all after her day job.

Rivers, 39, has worked in entertainment journalism for more than a decade. For her regular job at a music news website, she works an evening shift from 4 p.m. to midnight — but her nights don't end there. After she finishes her first job, she dives into her second, often working on stories for Our Black Girls well into the night.

Since the website's inception three years ago, Rivers has published an article roughly every other day. It's a grueling schedule, but she keeps it up because, as she explains, she could have easily been one of these missing girls and women. Anyone could.

In so many of the stories that Rivers writes about, the victims are "walking down the street or they're going to the store or 'they'll be right back,' and they just disappear," she says. "It could happen to me at any time."

"And I know that there are a lot of stories like that about girls and women who look like me, so why am I not seeing them as much as I'm seeing everything else? And then it became, why am I waiting for somebody else to pick up this banner when I'm the one who's passionate about it?"

There are other blogs and organizations that focus on missing Black people, but as Rivers says, "I can do it, that's the point."

Each post on Rivers' site chronicles the story of how a Black girl or woman went missing — and provides a fuller picture of who she is and how much she is loved, based on information from friends and family.

Sometimes, victims' loved ones will reach out to Rivers to express their gratitude after seeing the post; often, they're frustrated by their local police department's lack of action and are just grateful that someone somewhere has noticed and cares.

Other people reach out because they're surprised they've never heard of a case, even though it's something that happened right in their town.

On one occasion, Rivers wrote about a man who had murdered an entire family, and the daughter of a woman killed by the same man in a separate incident reached out to her, hoping to share her mother's story, too.

Rivers hopes that publicizing these stories will reignite interest, and authorities will be forced to take another look.

"I don't want to be just the latest person who writes about these girls and these women," she says. "I want there to be an end to their story or an end to this chapter, whether we find out what happened, whether somebody got justice, whatever it is."

The media ignores missing Black and Indigenous women

Black girls and women go missing at high rates, but that isn't reflected in news coverage of missing persons cases. In 2020, of the 268,884 girls and women who were reported missing, 90,333, or nearly 34% of them, were Black, according to the National Crime Information Center. Meanwhile, Black girls and women account for only about 15% of the U.S. female population, according to census data. In contrast, white girls and women — which includes those who identify as Hispanic — made up 59% of the missing, while accounting for 75% of the overall female population.

In light of these numbers, the disproportionate media attention on missing white girls and women is glaring. Often described as "missing white woman syndrome," the term most recently made headlines when MSNBC host Joy Reid discussed the Gabby Petito case. Petito was reported missing after her boyfriend returned from a cross-country trip without her; her case attracted nationwide coverage but put a spotlight on the harsh reality that people in other demographic groups don't receive the same attention when they vanish.

Authorities converged in Wyoming to search for Petito and found her remains at a national park. In the same state, more than 400 Indigenous girls and women went missing between 2011 and the fall of 2020, according to a state report. Indigenous people made up 21% of homicide victims in Wyoming between 2000 and 2020, despite being less than 3% of the state's population. The disparity can be seen in the media: Only 18% of Indigenous female victims received coverage. However, among white victims, 51% were in the news.

To be clear, Rivers explains, it's not about asking for more attention or being in "competition" with white people — it's about other groups getting the same attention as white victims and having their lives honored in the same ways.

"I'm talking about getting investigations up to par with what is already going on," she explains. "And I think when we bring that awareness, especially when it comes to Indigenous women and with Black women, and we're like, 'Hey, we exist as well.' It's not to say stop searching for that white woman. It's like, search for our women as much as you do anybody else and make sure that whatever energy that you place into one case is the same energy that you place into others."

You can help support efforts to find the missing

Rivers isn't the only one trying to highlight these cases. Two Black women founded the Black and Missing Foundation in 2008 to bring attention to the thousands of Black people who go missing every day in the U.S. And podcasts like Crime Noir, Black Girl Gone and Black Girl Missing are working tirelessly to honor these stories as well.

There is power in forming community. "We really are our sister's keeper," Rivers says.

For others who want to be a part of the solution, Rivers suggests staying informed of what's happening, especially in your own community, and sharing the information that you do see. That can mean retweeting a missing person's alert or sharing it on Facebook. Contact your local news organizations and investigative agencies and ask for updates.

You can also support those who are doing the work through blogs and podcasts, as well as via Instagram accounts and Facebook groups dedicated to keeping people informed on the cases of missing Black girls and women.

However, Rivers warns against sensationalizing someone's real-life tragedy — an ever-present risk in the true crime community.

Remember that "these were actual human beings with families and with hopes and dreams and purpose," she says. "These are real humans that laughed, cried, smiled and did not expect to not see tomorrow, did not expect to vanish off the face of the Earth. And I want to make sure that they are respected and honored."

Every post on Our Black Girls ends the same: "She is our sister and her life matters." And that is something that must be remembered.

A Haitian family escapes from the Hotel Coahuila after defending themselves with broken glass. (photo: Stephania Corpi Arnaud/BuzzFeed News)

A Haitian family escapes from the Hotel Coahuila after defending themselves with broken glass. (photo: Stephania Corpi Arnaud/BuzzFeed News)

“If you send me to Haiti, I have no one there to help me,” said a father, holding a shard of glass to keep Mexican authorities from entering a hotel room holding his family. “I can’t go back.”

Returning to Mexico was a last resort for the Haitians after crossing the Rio Grande and setting up camp under a bridge in Del Rio, Texas. Food, water, and medicine were lacking. Border Patrol agents on horseback chased them. Children were getting sick. There was no avoiding COVID-19. President Joe Biden’s administration started loading people onto planes and flying them back to Haiti, a place many of the immigrants haven’t lived in for years.

Though Mexico has easier access to supplies and shelter (under the bridge, people slept on rocks, dirt, and cardboard), authorities there inflict nights of terror on those hiding from deportation. It’s the largely unseen impact of the Biden administration’s hardline handling of the Haitian immigration to the United States and years of Mexico being pressured by the US to stop immigrants from ever reaching the border.

They came to the Hotel Coahuila around 2 a.m. National Guard and Mexican immigration agents marched in wearing bulletproof vests and helmets and holding long guns. The quiet street below was suddenly filled with smashing sounds, then the crack of shattered glass and the shrieks of a Haitian family.

Hotel security footage viewed by BuzzFeed News shows part of what happened inside: a Haitian father, standing in the doorway of his hotel room — his son and wife inside — with authorities to his left and right in the hallway.

In his bloody hand is a large chunk of sharp glass. It was part of a dresser mirror, possibly used to try to block the tiny room’s wooden door that broke in the struggle between the family and the agents.

He used the glass, despite it digging into his skin, to hold at bay at least a dozen armed soldiers and agents in the narrow hallway.

There is nothing in Haiti for his family, he told them, while holding the glass with two hands close to his chest, sometimes using one hand to make a motion dismissing the agents. He kept his back to the group of officials to his left, down the hall, but frequently peered over his shoulder to see where they were. A bright beam from an agent’s flashlight lit up the floor.

The father held off the agents for about 10 minutes as raids were conducted throughout the hotel. He was successful. Eventually, the authorities left him and his family alone.

Others were not as fortunate. The agents sped off with two vans of other immigrants they had pulled out of about 10 rooms of the hotel.

Moments later, the father, carrying his son in one hand and dripping blood from the other, ran down the hotel’s small steps, followed by his partner and another couple with a child. They then ran to the front of the hotel and into the dark streets to hide again. They weren’t going to wait for Mexican authorities to return.

Inside the hotel, the doors of the rooms the Haitians were pulled out of were left open. The lights were still on, blankets were crumpled on the ground, and leftovers from dinners in styrene containers were left out. Inside the second-floor room where the father fended off the authorities lay a toppled broken dresser and shards of glass, and there was blood on the floor.

It was a scene that had been repeating itself in recent days after thousands of immigrants who were living underneath the Del Rio Bridge came to Mexico. During the day, caravans of local police, soldiers, and immigration agents patrolled the streets of Ciudad Acuña looking for immigrants who came to buy food or take out money family members had sent them. At night, armed Mexican authorities entered cheap motels, knocking on doors and asking for identification.

For many, being returned to Haiti is not an option. The island nation has been plagued by earthquakes, corruption, and poverty, forcing thousands to abandon their homes and leave behind family in search of better economic opportunities. The ones who have left are expected to be the main breadwinners for their families back in Haiti, who are relying on them making it to the US.

The search for immigrants continued in Ciudad Acuña on Wednesday afternoon, with trucks carrying National Guard troops rushing through narrow streets and immigration agents stopping people they suspected were immigrants.

Two agents demanded a Black woman show her documents proving she has some kind of legal status in Mexico, which she did. Still, the agents told the woman she had to go to their offices so they could review her ability to be in Mexico.

Outside the Ciudad Acuña offices of the National Institute of Migration, an 18-year-old Haitian woman, Helena, was turning herself in.

She asked to be sent to Tapachula, a city in Southern Mexico that’s a popular crossing area for immigrants. Tapachula is often described by immigrants as being a prison because Mexican authorities make it very difficult to leave.

Helena’s boyfriend had been sent there by Mexican authorities and she wanted to reunite with him, but the bus companies refused to sell her a ticket and she feared being on the streets alone.

“The situation here is tough, but it’s better than Haiti, even though that is my country,” Helena told BuzzFeed News moments before agents took her in. “All that is waiting for me in Haiti is poverty and misery.”

The Haitians who left Del Rio were joined in Mexico by some Venezuelans and Cubans. And there was Viviana, a 43-year-old single mother from the Dominican Republic, who traveled to the US–Mexico border with her cousin and his family.

She and her cousin were taken in by a Mexican family. She spends her days in the home’s courtyard and sleeps in a small room in the back. She asked to only be identified by her first name.

After about four days of living underneath the bridge, Viviana read the news that the Biden administration had flown people back to Haiti on planes, confirming what had only been a rumor at the camp.

Tiffany Burrow, operations director for the Val Verde Humanitarian Border Coalition’s migrant respite center, said more than 1,000 immigrants had been released in Del Rio since Monday. It’s unclear how the Department of Homeland Security decides which immigrants are allowed to stay in the US and which ones are put on flights to Haiti. Some of those who have been released include families with newborns and people who are pregnant.

The Biden administration has kept in place a Trump-era policy that allows them to expel some immigrants and asylum-seekers at the border without the opportunity to request protection. In addition to the policy, known as Title 42, US authorities are also using a process called “expedited removal” to deport recent undocumented immigrants more quickly.

Even if there’s a chance Viviana could be released into the US, the prospect of being sent back to the Dominican Republic — to her two sons and parents counting on her to lift them out of poverty — made her decide to go back to Mexico.

“No one wants to leave their country, it’s a tough choice,” Viviana told BuzzFeed News. “But I have people relying on me to feed them.”

Many of the immigrants under the bridge in Del Rio left for South America years ago after a devastating earthquake rocked Haiti. Haitians now at the border said it was hard to find a job that paid well because they were undocumented in countries like Brazil and Chile, which was made worse by the economic toll of the pandemic.

The number of Haitians encountered in the Del Rio sector of the border started to dramatically increase in June, reaching 4,094 — more than double that of May. In August, 5,196 Haitians were encountered by agents, according to data from Customs and Border Protection. In all of 2020, the Del Rio sector had only encountered 2,000 immigrants from Haiti.

On Sunday, the day the return flights to Haiti started, Viviana and her cousin waded across the Rio Grande into Mexico. They slept outside a church on the first night. The next day, Mexican police officers spotted them. They ran and hid in the front yard of a home. Viviana begged the owner to help hide them. She agreed.

“It’s scary out there, even for me, because it seems as if the military is on every corner waiting to catch people,” the owner, who declined to be identified, said. “I try to help the ones I can because you never know when it will be you who needs help.”

Viviana’s 22-year-old cousin, Christian, who is half Haitian and half Dominican, said they don’t know how long they’ll have to hide in the courtyard.

“We can’t stay hiding like this forever,” Christian told BuzzFeed News. “I have a son I want to give a better life to, an education.”

Nearly a third of Australia's koalas were wiped out in just the past three years. (photo: Getty)

Nearly a third of Australia's koalas were wiped out in just the past three years. (photo: Getty)

Nearly a third of the koalas were wiped out in just the past three years, according to new figures released by a conservation group, although some experts say real numbers are difficult to establish.

Nearly a third of Australia's koalas were wiped out in just the past three years, according to new figures released by a conservation group, though some experts say real numbers are hard to establish.

What's not in doubt, they agree, is that the animal's population is in decline as Australia confronts climate change and other issues.

The country has lost an estimated 30 percent of its koalas since 2018 as a result of wildfires, drought, heat waves and land clearing, the Australian Koala Foundation said in a release Monday.

The nonprofit conservation group urged the government to do more about what it called a “disturbing trend."

It estimates the koala population to now be in the range of 32,000-58,000 — down from an estimated 46,000-82,000 in 2018.

It said the worst decline was seen in the southeastern state of New South Wales, where it estimates the numbers have dropped by as much as 41 percent. The foundation said every region across Australia saw a decline in population.

The conservation group doesn’t explicitly state how the data was obtained, but said it's the first organization to estimate koala numbers across the country. NBC News has reached out to the foundation for comment and for details on its methodology.

The koala, a herbivorous marsupial that lives mostly in eastern and southern regions of the country, has become synonymous with Australia around the world.

It was listed as a vulnerable species in parts of the country in 2012. Last June, a parliamentary inquiry determined that koalas in New South Wales could become extinct by 2050 unless the government immediately intervenes to protect them and their habitat.

Images of burned and thirsty koalas in charred trees and bushes became symbolic of the devastating toll of the catastrophic wildfires that swept large swaths of the country in late 2019 and early 2020, killing or displacing an estimated 3 billion total animals.

Chris Dickman, a professor of ecology at the University of Sydney, said that although talk of a 30 percent decline in three years "is dramatic," it "does seem plausible."

"Field surveys and modeling indicate that koalas were in a worrying decline before the drought and megafires of 2019-20," he said. "Where the fires were severe and the forest canopy was burnt, it is difficult to see how any koalas could have survived for very long, and the rate of decline would have been increased."

But some experts said that while Australia's koala population endured a heavy toll in recent years, the real numbers are tricky to establish.

Corey Bradshaw, an ecology professor with Flinders University in Adelaide, told NBC News by phone Wednesday there is “no question the koalas are in trouble” as part of a long-term trend of population decline, but he questioned the numbers released by the Australian Koala Foundation.

He pointed to a 2016 paper that puts the population of koalas in Australia at 329,000 as a more authoritative assessment, although he conceded that number doesn’t account for the koalas lost in recent wildfires.

"There are a lot of fragmented small populations, a lot of inbreeding and a lot of disease,” he added.

Bradshaw described koalas as "inevitably stuffed" on Twitter.

Ben Moore, senior lecturer with the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at Western Sydney University, also said the numbers released by the foundation are “very much on the low side.”

But, he said, the trend the figures illustrate is real and a “concern.”

“Every study of koala numbers consistently shows their numbers are declining,” he added. “Exactly the magnitude of the decline is hard to say.”

Dr. Natasha Speight, lead researcher of the Koala Health Research Group at the University of Adelaide's School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, said via email Wednesday that it is difficult to accurately estimate the numbers of koalas in wild populations, and hence the proportion of the entire population that has been lost.

But, she said, it's likely that the koala numbers in Australia have dramatically declined in the past three years, particularly due to the wildfires.

“Compounding this is the high number of koalas lost every year due to motor vehicle collisions, chlamydiosis and as a result of habitat loss,” Speight said, adding that there are concerns for the species' future.

She said there is a strong need for an official assessment of the numbers of koalas and their health status in each state across the country, to determine what measures need to be put in place to protect the animals and their habitat into the future.

In light of its report, the Australian Koala Foundation urged the government to do more to protect the species and put forward a koala protection act.

"I just think action is now imperative. I know that it can just sound like this endless story of death and destruction, but these figures are right. They're probably worse," the group's chair, Deborah Tabart, told Reuters Tuesday.

In June the Australian government called for public comment on a national recovery plan for the koalas in three regions of the country. Comments on the plan are due Friday.

According to the Australian Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, koalas in some regions of the country face increasing threats from issues including urban expansion, habitat loss, and their susceptibility to drought and climate change.

NBC News has reached out to the department for comment on the figures released by the Australian Koala Foundation.

Australia’s conservation efforts did see a boost last week when authorities said the bandicoot, a small furry marsupial, had been brought back from the brink of extinction on the country's mainland.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611