Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

This began a period in which American politics was dominated by the traumatized reaction to the September 11 attacks, with virtually all Democrats joining Republicans in backing the Bush administration’s retaliatory actions against the Afghan Taliban government, which had harbored much of Al Qaeda’s leadership. On September 14, a formal authorization of military force swept through the Senate unanimously and drew just one dissenting vote (that of California Democrat Barbara Lee) in the House. While Bush’s decision to expand his “global war on terror” beyond Afghanistan to Iraq lost a lot of Democratic and even some Republican support, the fear of looking weak on national security gripped much of the Donkey Party up to and beyond the 2004 presidential election — a tortured legacy that remains with us to this day.

Before the Storm

The climate of quasi-militarism that suffused U.S. politics after 9/11 was an abrupt change in the weather. Americans were generally thought to have overcome the “Vietnam Syndrome” of reflexive hostility to foreign military interventions. But any open-mindedness to war was limited to conflicts involving quick and successful engagements with limited U.S. casualties, such as the Persian Gulf War of 1991 and the NATO Kosovo mission of 1998–99.

During the months prior to 9/11, the United States seemed to be fully enjoying the “peace dividend” of reduced defense costs and the end a decade earlier of international commitments associated with the Cold War. I can recall receiving a briefing on a private national poll that concluded there was no outstanding international issue, involving either security or commerce, that was likely to affect voting decisions by any significant bloc in the electorate. The major parties were not notably divided on matters of war and peace; nor were there big intra-party differences. Reflexively anti-Clinton Republicans were much more likely than Democrats to oppose the last prior military engagement, in Kosovo. And in the 2000 presidential contest, despite posturing a bit about the allegedly poor state of military preparedness under Clinton, George W. Bush also argued for greater “humility” in U.S. foreign policy. The avenging warlord Bush would become within a year of his inauguration was nowhere in sight, except perhaps as a glimmer in his vice-president’s eye.

Bush’s pre-9/11 record as president was focused entirely on a domestic agenda designed to satisfy both loyal Republican constituencies and selected swing voters. On the eve of the attacks Bush’s job approval rating stood at 51 percent. By September 22, it had hit 90 percent, the highest Gallup has every recorded (and a point higher than his father’s at the close of the Persian Gulf War).

The Loyal Opposition Splits Over Iraq

The U.S. invasion of Afghanistan achieved its initial goals quickly, with the Taliban being driven from power in less than two months. It was not evident then that Operation Enduring Freedom had devolved into a combined nation-building-and-counter-insurgency effort that would last 20 years and end in failure. The American mission in that country enjoyed near-universal support in both parties until well into the Obama administration and (as we will see) particularly intense support from Democrats.

But soon after Kabul was “liberated,” the Bush administration shifted its attention to Iraq. Bush’s advisers believed that the GWOT and its impact on both public opinion and the opposition party might enable them to undertake an attack on Saddam Hussein’s regime that many of them had favored since the president’s father decided against attempting a regime change at the end of the Gulf War. The administration’s decision to seek a formal congressional authorization for an invasion of Iraq may have in part represented a strategy to split (and if possible, co-opt) Democrats immediately prior to the 2002 midterm elections. If so, it worked.

In the run-up to the October 2002 authorization vote in Congress, the ranking Democrat (Joe Biden) and Republican (Dick Lugar) on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee devised a compromise that would have probably halted the rush to war by creating hoops Bush would have to jump through before sending in the troops. Conceivably, it might have avoided an invasion altogether. But at the crucial juncture, Biden had trouble getting antiwar Senate Democrats to support the compromise. And then, in anticipation of a 2004 presidential run, House Democratic Leader Dick Gephardt stabbed Biden in the back by appearing (along with another putative 2004 Democratic presidential candidate, Joe Lieberman, who had long pined for an Iraq invasion) with Bush in a Rose Garden event endorsing the president’s preference: a de facto blank check version of the authorization. As George Packer noted a bit later, the moment perfectly reflected what 9/11 had done to the Democratic Party:

The two complementary tendencies that doomed [Biden’s] effort on Iraq have characterized Democrats since the war on terrorism began: on one side, the urge to take cover under Republican policies in order not to be labelled weak; on the other, a rigid opposition that invokes moral principle but often leads to the very results it seeks to prevent.

Ultimately, Democrats were deeply split on Bush’s war authorization. A majority (126 to 81) of House Democrats voted against it, while a majority of Senate Democrats (29 to 21) voted for it. Aside from Gephardt and Lieberman, supporters of the measure included all the Democratic senators who would run for president in 2004 and 2008: Biden plus Hillary Clinton, Chris Dodd, John Edwards, and John Kerry.

The Rise of “Security Moms”

Any hope the Democratic “Iraq hawks” might have harbored of positioning the party to overcome Bush’s popularity was dispelled by the 2002 elections. For only the second time since 1934, the president’s party gained House seats in a midterm. And for the first time ever, the president’s party flipped control of a congressional chamber — the Senate — in a midterm.

Postelection analysis of the upset dwelled heavily on national security issues, as Peter Beinart recalled later, with a certain U.S. senator as his witness:

Democrats got creamed in midterm elections that year because the women voters they had relied on throughout the Clinton years deserted them. In 2000, women favored Democratic congressional candidates by nine points. In 2002, that advantage disappeared entirely. The biggest reason: 9/11. In polls that year, according to Gallup, women consistently expressed more fear of terrorism that men. And that fear pushed them toward the GOP, which they trusted far more to keep the nation safe. As then-Senator Joe Biden declared after his party’s midterm shellacking, “Soccer moms are security moms now.”

The campaign that seemed to exemplify the Democratic dilemma in 2002 was in Georgia. U.S. Senator Max Cleland, who lost both legs and an arm in combat in Vietnam, was defeated by Republican Saxby Chambliss after a savage campaign in which the incumbent was pounded relentlessly for favoring a “weak” homeland-security bill written by none other than Joe Lieberman, who, in Jeffrey Toobin’s apt words, had managed to serve “simultaneously as a punching bag and a cheerleader for the Bush White House.”

The 2002 results hung over the 2004 Democratic presidential-nominating contest like a cloud of nerve gas. Before anti–Iraq War voters began to consolidate behind Vermont Governor Howard Dean (who did not have the handicap of a voting record on war and peace), many “netroots” activists initially fell in love with Wesley Clark, a NATO commander during the Kosovo operation who opposed the war. Clark would be the prototype for antiwar Democratic candidates in the near future. But the eventual nominee, John Kerry, benefited enormously from his own record of military heroism in Vietnam, with his later high-profile anti–Vietnam War protest activity nicely rounding out his résumé.

The Kerry general-election campaign would show better than any one example how bedeviled Democrats had become during the period following 9/11. (Disclosure: I was on the periphery of Kerry’s campaign as a researcher and writer.) Spooked by 2002, Kerry’s handlers built up his credentials as a military hero as the campaign against Bush unfolded. They heavily promoted a biography (Douglas Brinkley’s Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War) that presented the candidate to the general electorate almost entirely through his war and immediate postwar record.

At the Democratic National Convention in Boston, the messaging focused heavily on Kerry the decorated veteran. A revealing incident occurred when his friend the aforementioned Max Cleland gave the Kerry campaign a draft nominating speech in which he began with the words “Max Cleland, reporting for duty.” The campaign talked Cleland into letting the nominee use the line at the beginning of his acceptance speech. (Kerry was initially reluctant for the very good reason that a salute and “reporting for duty” were perquisites for current, not former, military members.) And thus, indelibly, the 2004 Democratic presidential nominee was introduced to millions of Americans as a man of war.

Kerry’s campaign was incautiously setting him up for exactly what transpired in the dog days of August 2004: a spate of ads from a group calling itself Swift Boat Veterans for Truth maligning Kerry’s war record and attacking his antiwar protests as treasonous. Having placed too much weight on Kerry’s military heroism and failed to contextualize his protests against the same war in which he fought, the campaign compounded its errors by refusing to respond, reinforcing the impression that Democrats were afraid to talk about national security — a charge Republicans made explicit through a variety of anti-Kerry smears during their own convention.

Kerry did try to counterpunch by accusing Bush of botching efforts to capture or kill Osama bin Laden while focusing on a doomed occupation of Iraq, promoting a good war/bad war treatment of Afghanistan and Iraq that would become routine for Democrats until very recently. But in the end, Democratic divisions and equivocations on national security were too neatly symbolized by their nominee’s clumsy explanation of votes on amended and unamended war-funding measures: “I actually did vote for the $87 billion, before I voted against it.” When attendees of the RNC danced and flourished flip-flops at every mention of Kerry’s name, the damage was multiplied, and if anyone missed that show, there was a Bush-Cheney ad using footage of the Democrat engaging in his favorite pastime of wind surfing:

The 2004 exit polls showed that 58 percent of voters trusted Bush to “handle terrorism,” but just 40 percent felt the same way about Kerry. In a close election decided by just over 100,000 votes in Ohio, that may have been the difference.

The “Fighting Dems”

As public opinion slowly turned against the Iraq War and Democrats began to unite in opposition to Bush’s open-ended engagement, Democrats still often felt defensive about their alleged reputation for weakness on national security. They continued to call for greater military aggressiveness in Afghanistan even as they called for a draw-down or even a withdrawal from Iraq.

In 2006, congressional Democrats made a big production out of attracting war veterans — some from Vietnam but others from the Gulf War or the more recent Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts — to challenge Republican incumbents or contest open seats. Fifty-nine such “Fighting Dems” won House primaries, while another 31 ran and lost or withdrew; two veterans won Senate primaries. While only six (five House candidates and one Senate candidate) ultimately prevailed, they were thought to have given the entire party a coat of insulation against claims that donkeys are peaceful animals with an insufficient willingness to bite and smite America’s enemies. Democrats did regain control of both Houses of Congress in 2006.

The symbol of Democratic anti–Iraq War pugilism in that era was 2006 Senate winner Jim Webb of Virginia. First in his class at Annapolis and then a Marine officer highly decorated for combat service in Vietnam, Webb had a distinguished academic and literary career before joining the Reagan administration, in which he eventually was appointed secretary of the Navy. After resigning from that post (reportedly in protest against plans to reduce the size of the Navy), Webb began an eccentric career in political kibbitzing for and against candidates from both parties, before his anger at George W. Bush’s Iraq policies made him a Democrat and then a Senate candidate against George Allen, whom Webb had endorsed six years earlier.

Webb’s 2006 victory made him an instant national celebrity, and he was tapped to give his new party’s response to Bush’s State of the Union Address in January of 2007. His well-received remarks were a sort of Fighting Dem apotheosis, quoting the famously militaristic presidents Andrew Jackson and Theodore Roosevelt on behalf of “populist” domestic policies and then attacking Bush for strategic ineptitude in Iraq:

The majority of the nation no longer supports the way this war is being fought; nor does the majority of our military. We need a new direction. Not one step back from the war against international terrorism. Not a precipitous withdrawal that ignores the possibility of further chaos. But an immediate shift toward strong regionally-based diplomacy, a policy that takes our soldiers off the streets of Iraq’s cities, and a formula that will in short order allow our combat forces to leave Iraq.

Webb, who had recently published a book entitled Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America and would soon pen A Time to Fight: Reclaiming a Fair and Just America, was a perennial favorite of lefty “populists” during the latter stages of the post-9/11 decade. By the time he finally ran for president in the 2016 cycle, his bizarre defense of the display of Confederate symbols had reminded observers his service in the Reagan administration was no accident and that progressive militarism was and is problematic.

Obama’s Strategic Ambiguity

On the eve of the 2008 election, as George W. Bush’s presidency ground to an ignominious end amid disasters at home and abroad, his approval ratings as measured by Gallup had dropped from that 90 percent peak after 9/11 all the way to 25 percent . The GOP nominee to succeed him, John McCain, was a more credible warlord figure than W., however, and possessed in addition a “maverick” image that made him less of an inheritor of Bush’s and his party’s unpopularity.

Unlike most of his rivals for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination (e.g., Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, Chris Dodd, and John Edwards), Barack Obama, a freshman senator from Illinois, did not have to defend past support for the Iraq War. In fact, he spoke at an antiwar rally as an Illinois state senator the day the war authorization was introduced in Congress. But he kept a prudent distance from the progressive “netroots” activists who had cut their teeth on the Dean and Clark campaigns four years earlier and coupled his criticisms of McCain’s support for an Iraq War “surge” with his own calls for a refocus on victory in Afghanistan.

As his primary campaign settled into a close battle with Hillary Clinton (who was running ads suggesting Obama was too inexperienced to deal with a national security crisis), Obama balanced support from relatively dovish pols like Ted Kennedy and Gary Hart with endorsements from close-to-the-military Democrats like Sam Nunn and Lee Hamilton. He also let it be known that he was being advised by a 60-member group of former high-ranking military officers. And his choice of Joe Biden as a running mate added a veteran foreign-relations expert with solid Establishment credentials to the campaign and then his administration. He maintained a consistent pattern of strategic ambiguity when it came to competing wings of Democratic national security thinking. But he continued the good war/bad war tradition of post-9/11 Democrats criticizing one war but supporting another by launching his own troop surge in Afghanistan in 2009. And he attempted to finally end the Democratic Party’s fear of looking weak on terrorism with his dramatic announcement in May of 2011 that Osama bin Laden had been found and killed in Pakistan by U.S. special forces.

In his 2012 reelection campaign, Obama was on the offensive on national security issues, criticizing Mitt Romney for inexperience and inconsistency much as Republicans had criticized past Democratic nominees dating back to Michael Dukakis. “He was for and against the removal of Qaddafi, for and against setting a timetable to withdraw our troops from Afghanistan, for and against enforcing trade laws against China, and while he once said he would not move heaven and earth to get Osama bin Laden, he later claimed that any president would have authorized the mission to do so,” said Ben LaBolt, press secretary for the Obama campaign.

Did Trump Break the Mold?

Donald Trump’s harsh criticism of Bush’s “forever wars” in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the thorough trouncing he administered to traditional conservatives in the 2016 primaries and beyond, appeared initially to break the mold of post-9/11 national security politics. But Trump and his allies haven’t missed a beat in accusing Democrats of weakness and fecklessness in dealing with terrorists and other enemies, which they often conflate with immigrants and refugees. The 45th president mastered the crude demagogic appeal of threatening unimaginable and uninhibited violence against any foreign adversary big or small who crosses the United States or its truculent leader.

So once again Democrats found themselves under fire for “weakness” whenever they failed to match Trump’s wild bellicosity or willingness to throw money at the Pentagon. And now that Joe Biden has ended the war on Afghanistan that marked the beginning of America’s War on Terror, Republicans in and out of office are savaging him for his failures to reverse a long, losing battle against the Taliban or to save the compromised Afghan allies that many of these same Republicans do not wish to invite to resettle in the U.S.

Democrats focused on Biden’s perilous efforts to battle COVID-19 while enacting the most ambitious domestic-policy agenda since LBJ’s Great Society initiatives are betraying a familiar desire to change the subject or find some symbolic burst of violence their president can unleash to prove his mettle and salvage his party’s reputation. While the crisis in Kabul is no 9/11, it is having a similarly traumatic effect on a Democratic Party that still struggles to convince Americans that multilateral diplomacy, economic strength, and efforts to deal with the root causes of terrorism are not only adequate but irreplaceable in the task of keeping the country secure. That Democrats are willing to face existential threats like climate change and global inequality that most Republicans hardly acknowledge as real should make up for decades of smears. But it doesn’t. And so, for the foreseeable future, when the war drums are sounded, you can expect Democrats to dance to their beat or deny they hear them at all. It’s a 20-year habit that will be hard to break.

Gov. Greg Abbott with Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and House Speaker Dade Phelan at the Texas Capitol on June 16, 2021. (photo: KSAT)

Gov. Greg Abbott with Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and House Speaker Dade Phelan at the Texas Capitol on June 16, 2021. (photo: KSAT)

Abbott, a Republican, said during a signing ceremony in the East Texas city of Tyler that the law is intended to combat voter fraud. Critics have said it will make it harder for Black and Hispanic voters - important voting blocs for Democrats - to cast ballots.

During the months-long fight over the legislation, Democratic lawmakers fled the state in a failed bid to stop it. Now, the fight has moved into federal and state courts in Texas, as civil rights organizations challenged the law in three separate lawsuits filed on Tuesday.

At least 18 states have enacted 30 laws restricting voting access this year, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, following Republican former President Donald Trump's false claims that the 2020 election was stolen from him through widespread voting fraud.

The Texas law makes it tougher to cast ballots through the mail by preventing officials from sending unsolicited mail-in ballot applications and adding new identification requirements for such voting. It also prohibits drive-through and 24-hour voting locations, limits early voting, empowers partisan poll-watchers and restricts who can help voters requiring assistance because of disabilities or language barriers.

"It ensures that every eligible voter will have the opportunity to vote," Abbott said at the signing ceremony. "It does also, however, make sure that it is harder for people to cheat at the ballot box in Texas."

Texas is the second most-populous state and the largest controlled by Republicans.

After Abbott signed the law, Biden wrote on Twitter, "We're facing an all-out assault on our democracy."

Biden urged Congress to pass national voting rights legislation that would counter the new state laws, something his fellow Democrats have tried but failed to do this year. Biden previously likened the Republican-backed voting restrictions to the so-called Jim Crow laws that once disenfranchised Black voters in the racially segregated South.

His administration sued Georgia in June to challenge that state's new voting restrictions, which the Justice Department called a violation of the rights of Black voters.

Plaintiffs in two federal lawsuits, filed against Texas officials in San Antonio and the state capital Austin, included the League of United Latin American Citizens, the Texas Alliance for Retired Americans and Texas community development groups.

They said the law unduly burdens the right to vote in violation of the U.S. Constitution's First, 14th and 15th Amendments, while also saying it is intended to limit minority voters' access to the ballot box in violation of a federal law called the Voting Rights Act.

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law filed a third lawsuit in state court in Houston, arguing that the measure violates provisions of the Texas Constitution protecting the rights to vote, freedom of speech and expression, due process and equal protection under law.

"The scourge of state-sanctioned voter suppression is alive and well, and Texas just became the most recent state to prove it," said Damon Hewitt, the group's president and executive director.

The measure won final approval in the Republican-controlled state legislature on Aug. 31 in a special legislative session. Dozens of Democratic lawmakers fled the state on July 12 to break the legislative quorum, delaying action for more than six weeks.

Election experts have said voting fraud is rare in the United States. Opponents of the Texas measure said Republicans presented no evidence of widespread voter fraud.

Catera Whitson (C) and Kyler Melancon (R) ride in the back of a high water truck as they volunteer to help evacuate people from homes after neighborhoods flooded in LaPlace, Louisiana on August 30, 2021. (photo: Patrick T. Fallon/Getty Images)

Catera Whitson (C) and Kyler Melancon (R) ride in the back of a high water truck as they volunteer to help evacuate people from homes after neighborhoods flooded in LaPlace, Louisiana on August 30, 2021. (photo: Patrick T. Fallon/Getty Images)

At the dawn of the new millennium, we directed our national resources in the exact wrong direction. But it’s not too late to turn things around.

The U.S. government has turned the whole globe into a potential battlefield, chasing some ill-defined danger “out there,” when, in reality, the danger is right here — and is partially of the U.S. government’s own creation. Plotting out the connections between this open-ended war and the climate crisis is a grim exercise, but an important one. It’s critical to examine how the War on Terror not only took up all of the oxygen when we should have been engaged in all-out effort to curb emissions, but also made the climate crisis far worse, by foreclosing on other potential frameworks under which the United States could relate with the rest of the world. Such bitter lessons are not academic: There is still time to stave off the worst climate scenarios, a goal that, if attained, would likely save hundreds of millions of lives, and prevent entire countries from being swallowed into the sea.

One of the most obvious lessons is financial: We should have been putting every resource toward stopping climate disaster, rather than pouring public goods into the war effort. According to a recent report by the National Priorities Project, which provides research about the federal budget, the United States has spent $21 trillion over the last 20 years on “foreign and domestic militarization.” Of that amount, $16 trillion went directly to the U.S. military — including $7.2 trillion that went directly to military contracts. This figure also includes $732 billion for federal law enforcement, “because counterterrorism and border security are part of their core mission, and because the militarization of police and the proliferation of mass incarceration both owe much to the activities and influences of federal law enforcement.”

Of course, big government spending can be a very good thing if it goes toward genuine social goods. The price tag of the War on Terror is especially tragic when one considers what could have been done with this money instead, note the report’s authors, Lindsay Koshgarian, Ashik Siddique and Lorah Steichen. A sum of $1.7 trillion could eliminate all student debt, $200 billion could cover 10 years of free preschool for all three and four year olds in the country. And, crucially, $4.5 trillion could cover the full cost of decarbonizing the U.S. electric grid.

But huge military budgets are not only bad when they contrast with poor domestic spending on social goods — our bloated Pentagon should, first and foremost, be opposed because of the harm it does around the world, where it has roughly 800 military bases, and almost a quarter of a million troops permanently stationed in other countries. A new report from Brown University’s Costs of War Project estimates that between 897,000 and 929,000 people have been killed “directly in the violence of the U.S. post‑9/ 11 wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere.” This number could be even higher. One estimate found that the U.S. war on Iraq alone killed one million Iraqis.

Still, the financial cost of war is worth examining because it reveals something about the moral priorities of our society. Any genuine effort to curb the climate crisis will require a tremendous mobilization of resources — a public works program on a scale that, in the United States, is typically only reserved for war. Now, discussions of such expenditures can be a bit misleading, since the cost of doing nothing to curb climate change is limitless: When the entirety of our social fabric is at stake, it seems silly to debate dollars here or there. But this is exactly what proponents of climate action are forced to do in our political climate. As I reported in March 2020, presidential candidates in the 2020 Democratic primary were grilled about how they would pay for social programs, like a Green New Deal, but not about how they would pay for wars.

In June 2019, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D‑N.Y.) estimated that the Green New Deal would cost $10 trillion. Her critics on the Right came up with their own number of up to $93 trillion, a figure that was then used as a talking point to bludgeon any hopes of the proposal’s passage. But let’s suppose for a moment that this number, calculated by American Action Forum, were correct, and the price of a Green New Deal came to 4.43 times the cost of 20 years of the War on Terror? So what? Shouldn’t we be willing to devote far more resources to protecting life than to taking it? What could be more valuable than safeguarding humanity against an existential threat?

The reality is that warding off the worst-case scenario of climate change, which the latest IPCC report says is still possible, will require massive amounts of spending upfront. Not only do we have to stop fossil fuel extraction and shift to decarbonized energy, but we have to do so in a way that does not leave an entire generation of workers destitute. Several proposals for how to achieve this have been floated: a just transition for workers; a revamping of public transit and public housing; public ownership of energy industries for the purpose of immediately decarbonizing them; global reparations for the harm the United States has done. Any way you look at it, meaningful climate legislation will require a huge mobilization of public resources — one that beats back the power of capital. And of course, dismantling the carbon-intensive U.S. military apparatus must be part of the equation.

In our society, it’s a given that we spend massive amounts of these public resources on military expansion year after year, with the National Defense Authorization Act regularly accounting for more than half of all discretionary federal spending (this year being no exception, despite President Biden’s promise to end “forever wars”). Over the past 20 years, the mobilization behind the War on Terror has been enabled by a massive propaganda effort. Think tanks financed by weapons contractors have filled cable and print media with “expert” commentators on the importance of open-ended war. Longstanding civilian suffering as a result post‑9/ 11 U.S. wars has been ignored. From abetting the Bush administration’s lies about weapons of mass destruction to the demonization of anti-war protesters as “terrorist” sympathizers, the organs of mass communication in this country have roundly fallen on the side of supporting the War on Terror, a dynamic that is in full evidence as media outlets move to discipline President Biden for actually ending the Afghanistan war.

What if a similar effort had been undertaken to educate the public about the need for dramatic climate action? Instead of falsehoods and selective moral outrage, we could have had sound, scientifically-based political education about the climate dangers that Exxon has known of for more than 40 years. We could have spent 20 years building the political will for social transformation. It may seem ridiculous to suggest that the war propaganda effort could have gone toward progressive ends: After all, the institutions responsible — corporate America, major media outlets and bipartisan lawmakers — were incentivized against such a public service, and would never have undertaken similar efforts for progressive ends.

But this gets at something crucial — if difficult to quantify — about the harm done by 20 years of the War on Terror. The push for militarization has been used to shut down exactly the left-wing political ideas that are vitally needed to curb the climate crisis. As I argued in February 2020, U.S. wars have repeatedly been used to justify a crackdown on left-wing movements. World War I saw passage of the Espionage Act, which was used to crack down on anti-war protesters and radical labor organizers. The Cold War was used as pretext for crackdowns on a whole host of domestic movements, from communist to socialist to Black Freedom, alongside U.S. support for vicious anti-communist massacres around the world. The War on Terror was no different, used to justify passage of the PATRIOT Act, which was used to police and surveil countless protesters, including environmentalists. The Global Justice Movement was sounding the alarm about the climate crisis in the late 1990s, and was not only subjected to post‑9/ 11 government repression, but was then forced to refocus on opposing George W. Bush’s global war effort.

The War on Terror also makes it nearly impossible to attain the kinds of global cooperation we need to address the climate crisis. It is difficult for countries to focus on making the transformations needed to curb climate change when they are focused on trying to survive U.S. bombings, invasions, meddling and sanctions. And it’s difficult to force the United States to reverse its disproportionate climate harms when perpetual war and confrontation is the primary American orientation toward much of the world, and the vast majority of U.S. global cooperation is aimed at maintaining this footing.

Such grim reflections on the climate harms wrought by 20 years of the War on Terror do not amount to a nihilistic “I told you so.” We vitally need to apply these grisly lessons now, as the nebulous “War on Terror” is still being waged, from drone wars in Somalia to the bombing campaign against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Meanwhile, while Biden claims to be “ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries,” he is overseeing an increasingly confrontational posture toward China, an approach championed by members of Congress in both parties. As dozens of environmental and social justice organizations noted in July, it is inconceivable that the world can curb the climate crisis without the cooperation of the United States (the biggest per-capita greenhouse gas emitter) and China (the biggest overall greenhouse gas emitter). Instead of militarizing the Asia-Pacific region to hedge against China, the United States could acknowledge this stark reality and launch an unprecedented effort for climate cooperation with China.

The possibilities for an alternative global orientation are both vast and difficult to know. What we do know is that the status quo of the War on Terror is not working. In addition to the hospitals the United States has bombed, the homes it has destroyed, the factories it has obliterated, and the people it has terrorized, the American military project has deeply worsened the climate crisis. And that crisis is now, undeniably, on our shores.

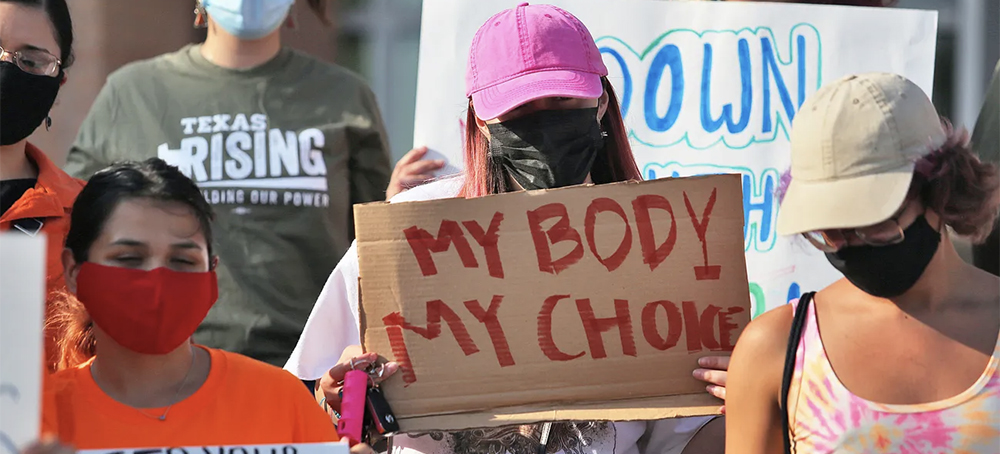

Abortion rights supporters in Texas. (photo: AP)

Abortion rights supporters in Texas. (photo: AP)

Site was removed from GoDaddy before being censored by new host Epik, known for providing services to far-right groups

The site ProLifeWhistleblower.com was removed from its original web host by the provider GoDaddy on Friday before being suspended by its new host, an agency known for providing services to far-right groups.

“For all intents and purposes it is offline,” Ronald Guilmette, a web infrastructure expert, told the Guardian. “They are having technical difficulties. My personal speculation is that they are going to have trouble keeping it online moving forward.”

As of Tuesday, ProLifeWhistleblower.com redirects to Texas Right to Life’s main website.

Created by Texas Right to Life, an evangelical Christian group, the site allowed people to anonymously submit information about potential violations of the new law – which makes it illegal to help women in Texas access abortion after the sixth week of pregnancy.

In recent days, internet users have protested against the site by flooding it with false reports, memes and even porn in the hopes of rendering it less effective.

The website’s difficulties were compounded when GoDaddy, which provides the servers where the website lives, said the site had violated its privacy policies that bar the sharing of third-party personal information including data related to medical issues such as abortion.

The site was then moved to Epik, according to domain registration data first reported by Ars Technica. Epik is known for its “anything goes” attitude towards web hosting, servicing sites that other companies have deplatformed elsewhere for hate speech and other content violations – including 8chan, Gab and Parler.

According to reports from the Daily Beast, Epik contacted the website about potential violation of its own rules concerning the collection of medical data about people obtaining abortions.

“We contacted the owner of the domain, who agreed to disable the collection of user submissions on this domain,” it said in a statement to the Daily Beast.

Epik representatives did not respond to a message seeking comment on Tuesday. As of the time of publishing at 2pm PST on Tuesday, Epik remained the host for ProLifeWhistleblower.com, according to domain registration data available online, although the site does not appear to be operational.

A Texas Right to Life spokeswoman, Kimberlyn Schwartz, said on Tuesday that the website was in the process of moving to a new host, but was not yet disclosing which one.

The original website allowed anyone to submit an anonymous “report” of someone illegally obtaining an abortion, including a section where images can be uploaded for proof.

“Any Texan can bring a lawsuit against an abortionist or someone aiding and abetting an abortion after six weeks,” the website reads, and those proved to be violating the law liable for a minimum of $10,000 in damages.

Schwartz said they were working to get the tipster website back up but noted that in many ways it was symbolic since anyone can report a violation. And, she said, abortion clinics appear to be complying with the law.

“I think that people see the whistleblower website as a symbol of the law but the law is still enforced, with or without our website,” Schwartz said, adding, “It’s not the only way that people can report violations of the law.”

Rebecca Parma, Texas Right to Life’s senior legislative associate, said they expected people to try to overwhelm the site with fake tips, adding “we’re thankful for the publicity to the website that’s coming from all of this chatter about it.”

Wendy Catalan Ruano and others from Movimiento Cosecha Indiana lead a march Saturday, April 24, 2021, through downtown Indianapolis. The event previews a larger march in Washington D.C. on May 1, where activists will call for protections for undocumented immigrants living in the United States. (photo: Jenna Watson/IndyStar)

Wendy Catalan Ruano and others from Movimiento Cosecha Indiana lead a march Saturday, April 24, 2021, through downtown Indianapolis. The event previews a larger march in Washington D.C. on May 1, where activists will call for protections for undocumented immigrants living in the United States. (photo: Jenna Watson/IndyStar)

"People don't understand what it's like to be in a place like this," Martinez said. "It's like we're in a cage. We haven't been outside at all. There's nothing here."

Martinez, of Logansport, has been in immigration detention at Boone County Jail in Kentucky for more than a year. He's detained as he waits on the adjudication of a visa from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Depending on the outcome — approvals, denials, appeals, or deportation — the process can take months or even years before detainees like Martinez can be released, experts told IndyStar.

During that time he's been in immigration detention, and due to COVID-19 restrictions, Martinezhas not been able to see his mother, siblings, nieces and nephews, who he looked after. He's faced discrimination from jail guards and the stress and isolation in detention are starting to take a toll on his physical and emotional health.

In a statement emailed to IndyStar, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials did not answer questions about recreational conditions for detainees at Boone County jail but said the agency is "firmly committed to the health and welfare of those in custody."

Boone County Jail officials in Kentucky denied claims that immigrant detainees are not given recreation time.

In an emailed statement to IndyStar Boone County, Burlington, Kentucky Jailer Jason Maydak said due to the pandemic and to follow social distancing guidelines, the jail is allowing smaller groups of inmates and immigration detainees in the recreation area.

“Occasionally, in order to get everyone’s recreation time in, we do run into the night hours,” Maydak said. “We do rotate the cells and hours that the inmates go to recreation so not everyone is getting just night hours.”

As he waits, Martinez, 39, often thinks about what his life could be like if he were released. He thinks about going back to Logansport, reuniting with his mother and siblings and providing for them, going back to work, purchasing a home and starting a family.

He is among thousands of undocumented immigrants who are held indefinitely at about 200 immigration detention centers (both private facilities and contracted county jails) across the country. At least one of those facilities is located in Indiana.

The uncertainty and not knowing how long he'll have to remain behind bars makes it all worse, Martinez said.

"It's depressing to know that, you know, they'll rush to get you out of the country but they're not in a rush to help you out," said Martinez, who came to the United States from El Salvador when he was 9 years old. "I try to take it week by week. Just waiting to see if I'll get a phone call with good news or not, you know? But it's frustrating."

In recent months, advocates have been calling for local and federal officials to end immigration detentions. They say the conditions at immigration detention centers are inhumane, traumatizing and the long-term separations break families apart.

In many cases, those individuals detained are in civil immigration proceedings and have not been convicted of a crime. Advocates say some immigrants who are detained, have come to the United States seeking asylum; others have lived in the United States most of their lives and have U.S. citizen children, spouses and other immediate relatives.

"Moris is a really good example of someone whose whole life is here, whose whole family is here in the United States and who is a complicated dreamer," said Hannah Cartwright, Martinez's attorney, and Mariposa Legal co-founder and executive director told IndyStar. "If our laws were different, he would already be a U.S. citizen, probably, but instead he's in this limbo where he doesn't have immediate access to immigration status and yet he's in some ways more American than me."

The patriarch of a mixed-status family

Martinez's parents fled violence and extreme poverty in El Salvador in the late '80s. They left Martinez behind until they found stability in the United States. To be reunited with his parents Martinez made the journey from El Salvador to California with a family friend who looked after him on the way, he said.

Not long after, the family moved to Indiana and they have lived in Logansport since.

Martinez graduated from Delphi Community High School in 1998. He worked as a supervisor at a manufacturing company and hoped to purchase the two-bedroom home he'd been renting.

He's the only one in his family without legal immigration status in the U.S.

His parents, who worked at the Tyson meat plant, obtained legal permanent resident status (green cards) through the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA) program —a federal law approved by Congress in 1997, which allowed immigrants from Nicaragua, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala and other countries to get work permits and protection from deportation. His younger siblings, nieces, and nephews are U.S. citizens.

As a minor, Martinez had Temporary Protected Status — a temporary status and work permit provided to immigrants of specifically designated countries that are experiencing ongoing armed conflict, environmental disaster, or extraordinary and temporary conditions. By the time he applied for a green card through the NACARA program, his age and marital status back then no longer qualified him for the program.

There are many mixed-status families, like Martinez's, in Indiana.

According to the American Immigration Council, in 2016, 100,000 undocumented immigrants called Indiana home. About 144,000 people in Indiana, including 67,700 U.S. citizens, lived with at least one undocumented family member between 2010 and 2014. During the same period, about 3% of children in the state were U.S. citizens living with at least one undocumented family member.

When Martinez was 21 years old, his father died of cirrhosis. Martinez then had to step up and look after his mother and siblings. He became the patriarch of the family.

"My main focus has been trying to get out so I can help my mom," Martinez said. "I feel like I owe her, you know, because this whole time I've been in here like, and I've been able to do nothing for her."

'We're not all perfect'

In 2011, Martinez was assaulted after leaving a bar in Logansport. He spent a week in intensive care and has deficits in memory and chronic headaches from the assault The man who attacked was convicted of battery the following year.

Alcoholism did not escape Martinez.

After the assault, he developed a drinking problem and had multiple encounters with law enforcement.

He served a three-year sentence in Cass County Jail for driving after forfeiture of his driver's license, which had been suspended after he accumulated traffic offenses, multiple driving under the influence offenses, and driving without a license.

He was set to be released in July of 2020 but was placed in immigration detention instead. He was first sent to Clay County Jail in Brazil, Ind. and was later transferred to the immigration detention center in Kentucky.

Martinez is aware of the choices he's made but hopes people in the community and immigration officials will understand that this country is his home, this country is all he knows, he said.

"Maybe people can look at it differently. I know we're not all perfect," he said. "We all make mistakes, you know, but at least let us pay for our mistakes here and not in a place where we don't know anything or anyone."

The need for immigration reform

For the past three months, Martinez has been waiting on approval of his U Visa application.The U Visa can be granted to undocumented immigrants who are victims of certain crimes, who have suffered mental or physical abuse, and are helpful to law enforcement or government officials in the investigation or prosecution of criminal activity.

But previously, Cartwright tried different avenues to get Martinez released from detention without success.

Last year, due to COVID-19 restrictions, ICE did not allow Martinez to marry his U.S. citizen fiancée while in custody. The marriage would have put him on a path to apply for a green card, Cartwright said.

Cartwright also asked ICE to review Martinez's case but the request was denied. His asylum application was denied and due to his previous charges, and he didn't qualify for the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

The back and forth between requests and applications has extended the time he remains in detention.

In an effort to drop the number of immigration arrests and deportations, in February the Biden administration issued an interim enforcement memo stating that ICE officers would need preapproval before issuing deportation orders for undocumented immigrants who are not recent border crossers, a national security threat or a criminal offender with an aggravated felony conviction.

Cartwright said Martinez does not meet the enforcement detention priorities.

The complexity of Martinez's case shows why there's an urgent need for immigration reform, she said.

"In this type of situation Moris's alcohol problems got exacerbated after he was the victim of this crime and putting him in a cage for over a year, is not the way of responding to that," she said. "When instead we could respond and say, 'this is an undocumented immigrant who was the victim of something terrible... but now we're going to put him on a path to be able to to be healthy and have a way of staying here in the United States.'"

ICE detention takes a toll on families

There are more than 24,000 people detained at ICE detention facilities in the United States as of Aug. 20, according to ICE data.

In Indiana, the Clay County Jail detains people for ICE under a contract with the U.S. Marshals Service and ICE also has an intergovernmental service agreement with the Marion County Jail. At the Boone County Jail in Kentucky where Martinez is detained, ICE is also under a contract with the U.S. Marshals Service.

The average time people spend in immigration detention depends on each case. It can be a few days, months, or years, said Dave Faherty, a supervising attorney at the National Immigrant Justice Center.

The uncertainty of detention can have long-lasting negative and traumatizing effects on individuals and their families. In-person visitation can be difficult and costly for families, too, he said, as detainees are often transferred to detention centers out of state.

"It hard to tell my clients, who are mothers with young children, when they'll get released because that is totally out of our hands," Faherty said. "And other clients with partners and wives and husbands. It's a strain on their relationship and for individuals being away for a very long time too, it's hard to readjust back into family life."

Martinez's mother, Maria Martinez told IndyStar the stress of not knowing whether her son is OK in detention, or whether he'll be able to stay in the United States, is taking a toll on her health.

"People don't understand how sad this situation is for me and I feel it. I have pain in the back of my head, I am constantly thinking about him, it never goes away," she said. "What I miss the most about him is that he always made sure I had everything I needed. I never had to ask, he was always the one there for me since my husband passed away."

Calls to end immigration detention

Locally and across the country immigrant advocates have been calling for the end of immigration detention.

The Biden administration in May ordered ICE to close two detention centers in Georgia and Massachusetts after allegations of abuse at both facilities.

In Indiana, advocates earlier this year asked the Marion County Sheriff to stop detaining people for ICE at the Marion County Jail.

And during the pandemic coronavirus cases spiked at several ICE detention centers across the country.

A complaint filed in May with the Department of Homeland Security Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties claimed that immigrants' lives are at risk in the custody of ICE at Clay County Jail due to the lack of precautions taken at the facility to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Movimiento Cosecha Indiana, an immigrant-led activism group advocating for immigrant youth and families, has been protesting and demanding the closure of ICE detention centers, a stop to deportations and family separations, and protections for millions of undocumented people living in the U.S.

In Indiana, undocumented people can't drive legally and do not qualify for unemployment insurance or federal and state emergency funds.

"(Immigration detention) is inhumane it's something that strips us of our dignity and it's something that's tied to things that could be resolved by the state" said Dara Marquez, a field organizer with Cosecha Indiana. "Undocumented immigrants aren't a new thing. We've been here for more than 20 years and there's absolutely nothing that's going to shift that."

Anyone who has a family member in immigration detention in Indiana and is seeking an immigration attorney can reach Mariposa Legal from 1-5 p.m. Monday-Friday at 317-426-0617 for a free consultation.

Israeli soldiers checking the documents of Palestinians as they cross into the West Bank from Israel on Monday as part of a manhunt for six Palestinian militants who broke out of Gilboa prison in northeastern Israel. (photo: Ammar Awad/Reuters)

Israeli soldiers checking the documents of Palestinians as they cross into the West Bank from Israel on Monday as part of a manhunt for six Palestinian militants who broke out of Gilboa prison in northeastern Israel. (photo: Ammar Awad/Reuters)

Palestinians in the besieged Gaza Strip have also celebrated the news.

The notorious Gilboa prison where the inmates escaped from is located about four kilometers from the West Bank and is one of the most highest-security and heavily guarded prisons for Palestinians in Israel. The facility has been described as a dungeon for Palestinians serving life sentences for “anti-Israeli activities”.

A Palestinian prisoner’s organization says four of the men were serving life sentences adding that the resistance members on the run range in age from 26 to 49 years old, with one of them detained by Tel Aviv since 1996.

Among the six former inmates is also Zakaria Zubeidi, 46, who had been jailed since 2019 and was a former commander of the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades in the West Bank town of Jenin during the second Palestinian uprising, which began in September 2000.

The Israeli regime’s military and other forces have started a search for the six Palestinians. The Israeli Prisons Service says five of the inmates belong to the Islamic Jihad resistance movement and one is a former commander of a resistance group affiliated with the mainstream Fatah party. It was not immediately clear whether they had help from outside to orchestrate the operation.

Islamic Jihad called the breakout “a heroic act that will shock the Zionist defense system.” The group commended them in a statement for “snatching their freedom with their fingertips from under the eyes and ears of the occupier.”

Several other Palestinian factions hailed the jailbreak as a slap in the face of the Israeli regime. The Qassam Brigades, the military wing of the Gaza-based Palestinian resistance movement Hamas, hailed the escape as “heroic”. Lebanon’s Hezbollah also extended its congratulations to the Palestinian people and resistance groups on the success of the prison break describing it as one of a kind.

The mother of one of the prisoners, Umm Mahmoud Al-Arada, said that she doesn't know where her son is, but hopes he has traveled to another country.

Israeli media have cited Israeli authorities as saying they are planning to move 400 other inmates to other prisons to avoid any other embarrassing jailbreaks for the regime.

Arik Yaacov, the service’s northern commander, claims the escapees appeared to have opened a hole from their prison cell toilet floor to access passages formed by the prison's construction. Reports say they fled via an underground tunnel that the inmates are believed to have spent months digging. Photos have circulated in Israeli media of a hole in the ground outside the prison, purporting to show the end of the escape route.

Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett's office says the premier has spoken with Israeli security officials and emphasized that this is a “grave incident” that requires an across-the-board effort by the regime’s forces to hunt down the escapees.

A military spokesman says Israeli forces believe the freed Palestinians might try to reach the occupied West Bank, where the Palestinian Authority exercises limited self-rule in some area, or the Jordanian border some 14 km to the east.

Israeli security forces have launched a manhunt for the Palestinian prisoners. Regime forces have been deployed in large numbers, setting up roadblocks after the rare jailbreak from the prison in northern Israel. Security forces are patrolling streets in the north and the occupied West Bank, as helicopters are flying above.

A Florida manatee in the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge. (photo: Keith Ramos/USFWS)

A Florida manatee in the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge. (photo: Keith Ramos/USFWS)

It came as little surprise, however, to scientists studying the manatees’ primary food source: seagrasses.

“Scientists have said time and time again that seagrass is declining, that there is a hell of a lot of nutrients in these waters, that there’s a big problem here that needs to be solved,” said Benjamin Jones, a seagrass ecologist and co-founder of the U.K.-based research organization Project Seagrass, in an interview with Mongabay. “But still nothing has really been done.”

The spate of deaths is still being investigated by the FWS as an unusual mortality event (UME), and so its cause is not yet official. Yet wildlife officers suspect the mass death is linked to the dieback of seagrass in the Indian River Lagoon, a major overwintering location for the Florida manatee, and where most of the deaths occurred.

Though West Indian manatees eat some other water plants, seagrass is their primary food source, particularly during cold months. Since 2009, seagrass in the lagoon has decreased by 58%, according to Charles Jacoby, supervising environmental scientist for the St. Johns River Water Management District.

Experts say the manatees’ deaths are a warning sign that the world needs to pay more attention to the health of these underappreciated habitats.

Unnoticed importance

The plants included in the term “seagrass” aren’t taxonomic bedfellows, though all are submerged flowering plants. They include brackish-tolerant and marine species in many shapes and sizes. As such, seagrasses are an ecological grouping, lumped together for the lush canopy they create on the seafloor. Seagrass meadows grow in shallow coastal waters around the world, from cool temperate latitudes to the tropics — and in all of these places they are on the decline.

In 2009, the first global assessment of seagrass loss, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, estimated that at least 29% of known seagrass areas had disappeared in the last 200 years, and that this loss is accelerating.

The decline has remained largely invisible to humans, at least until it manifests in something that catches our attention, such as the manatee deaths. Yet, seagrass meadows serve as vital habitat for thousands of marine species, from large animals that find food there — like sharks and turtles, as well as manatees — down to smaller fish, shellfish, and crustaceans.

Seagrass meadows are also important nurseries for baby fish. By one estimate, one-quarter of the world’s 25 largest fisheries depend on seagrass meadows to nurture fish during their juvenile years. When these meadows disappear, it’s no surprise that fisheries can collapse and, as in Florida’s case, animals starve.

Unlivable conditions

From Australia to Southeast Asia to Europe and the Americas, experts say the reason for these declines is fairly universal: deteriorating water quality. Because seagrasses are plants just like those on land, they need sunlight to photosynthesize. When coastal development washes sediment into the water, or when nutrients from agricultural fertilizer and sewage cause algal blooms, seagrasses can’t get enough light.

“That’s kind of the slow kill — it accumulates over time,” said Siti Maryam Yaakub, a Singapore-based marine ecologist with the environmental consulting group DHI, who works on ecological restoration and nature-based solutions.

As seagrasses struggle to get by with less light, they become more susceptible to more intense stressors. After years of poor water quality, a storm or heat wave — made more intense globally by climate change — can suddenly wipe out an entire seagrass meadow.

In the Indian River Lagoon, declines were caused by nutrient runoff from local roads, septic tanks, and fertilizer use. Over the winter of 2020-2021, these inputs caused an intense algal bloom, which may have been the final blow to struggling seagrass.

Generally, the best way to prevent this is good catchment management, making sure that land-based pollution doesn’t run off into the sea. But Yaakub says there is often “a disconnect between what happens on land and on the coast.”

“Anything marine falls under the ministry of fisheries, and then forestry takes care of plants on land,” she said. “And they just don’t meet in the middle.”

The solutions, however, are not as universal.

“Part of the big problem with seagrass is that no one strategy works for everywhere, really,” said Jones, whose research has focused on seagrass meadows both in the U.K. and in the Indo-Pacific. “You need to be on the ground, looking at what the threats are, and asking local communities what they think are the biggest things.”

Take, for example, restoration projects that aim to replant seagrass meadows. According to Yaakub, these efforts often fail if they fail to address the stressors that caused seagrass die-offs in the first place, whether that might be fertilizer from farming further inland, changing water circulation in a bay due to a land reclamation project, or sediment washing into the water because people have cut down local forests.

There are some bright spots in the world: in a research paper published in June, researchers found that seagrasses in 65% of Pacific Island countries and territories were either increasing or showing no signs of decline. The co-authors suggest this may be because these places, spanning Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia, exert fewer human impacts and have strong cultural connections to ocean ecosystems.

However, even these relatively resilient seagrass meadows face an uncertain future on a warming planet.

The climate conundrum

In Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the U.S., seagrasses have mounted a shaky recovery thanks to the cooperation of seven jurisdictions — Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia — to reduce nutrient runoff into the Bay’s watershed. Seagrass meadows in the Chesapeake rebounded from just 38,000 acres (15,400 hectares) in 1984 to nearly 109,000 acres (44,100 hectares) in 2018. (For comparison, prior to European colonization, scientists estimate that the Chesapeake’s seagrasses covered between 200,000 and 600,000 acres, or 81,000-243,000 hectares.)

Yet over 2019 and 2020, intense storms and increased rainfall muddied water clarity, and inundated some salt-favoring seagrasses with too much freshwater. This caused the Chesapeake’s seagrass coverage to drop back down to just over 60,000 acres (24,300 hectares).

In this, the Chesapeake may be a good case study for seagrasses under climate change, as rising temperatures cause stronger storms and more frequent heat waves, in the water as well as on land. Seagrasses in the bay are at the very limit of their heat tolerance, a situation that many other temperate and tropical seagrasses may find themselves in before the end of the century. According to Jessie Jarvis, a professor at the University of North Carolina Wilmington who has worked on seagrass research and restoration in the Chesapeake and beyond, that leaves seagrasses even less prepared for our rapidly warming world.

“When you add chronic stress, like the poor water quality in the Bay for decades, any time you have an acute event like these storms … because they’re already stressed they have less resilience,” Jarvis said.

If there is good news, it is that seagrasses that grow in healthy temperature limits and good water quality can adapt well to climate change, using extra CO2 to boost photosynthesis. If they do, they can serve as a highly efficient tool to mitigate the planet’s warming: seagrasses store more than double the carbon of the average terrestrial forest. Though the total area of seagrass meadows covers less than 0.2% of the world’s oceans, these grasses currently store about 20 billion metric tons, or 10%, of its carbon.

Rethinking protection

But to maintain seagrasses, experts say governments and the public alike need to start recognizing their importance. Jones says he was inspired to found Project Seagrass during his graduate work on U.K. seagrass meadows, when the sampling equipment he carried onto the train often led to conversations with curious strangers. Many of these people, he found, had no idea what seagrasses were.

This ignorance can be compounded by a “surprisingly negative mindset about the grasses” when they are noticed, says Brooke Landry, chair of the Chesapeake Bay Program Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Workgroup.

Though any Chesapeake-adjacent public school attendee gets a thorough education on the bay’s seagrasses, Landry told Mongabay that many transplants to the area don’t have the same knowledge. They don’t want seagrasses on their property, touching them while they swim, or interfering with boating.

Yet Landry says the same people must recognize that if they enjoy eating fish and shellfish, or love charismatic creatures like turtles and, yes, manatees, then they also need to love seagrass.

The mass die-off in Florida, therefore, could serve as a signal to rethink conservation as an effort that goes beyond just the health of creatures to which humans have ascribed value.

This is particularly the case when it comes to manatees and other long-lived mammals, for which conservation efforts have long focused primarily on preventing immediate death: things like vessel strikes or fishing net entanglement. However, “what we haven’t been thinking about is the carrying capacity of habitats,” Helen Marsh, professorial research fellow at James Cook University in Australia, told Mongabay. Marsh’s career has focused on the research and conservation of dugongs (Dugong dugon), a manatee relative that occurs in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Though preventing immediate death is still very important, “maybe what [the mass mortality event] is telling us is that we need to broaden our conservation outlook and to think more about habitats,” Marsh said. “We should be thinking more about the conservation of the plant communities on which these animals depend.”

This was originally published on Mongabay.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611