Pandemic Fundraising is No Fun

We did everything humanly possible to avoid our worst December year-end fundraising drive ever. In the end it did not work. It was more likely the Coronavirus that stole Christmas than the Grinch. December’s poor numbers were a continuation of what we were seeing in November which was record-low as well.

The great frustration is that we have truly wonderful Reader-Supporters, people who consistently support the organization and have for years. We just don’t have quite enough of them.

Our New Year’s Resolution has to be to shore up our funding. From all appearances that will require a concerted and determined effort. Pulling RSN through the Pandemic will not be fun or easy, but we must find a way.

Onward

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

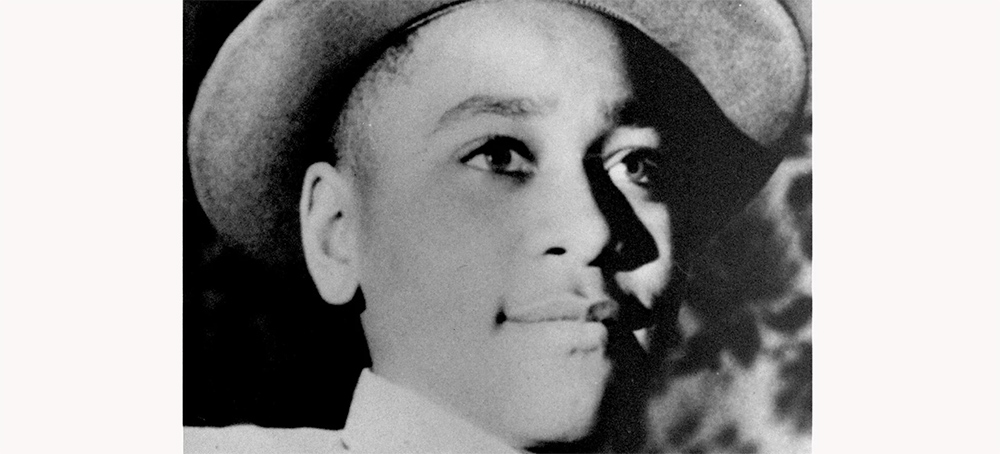

The Jim Crow era may be gone but its spirit is alive and well.

Till’s murder is often referred to as the “spark” for the Civil Rights Movement in the US. The photo of his disfigured face, which his mother had insisted on showing through an open-casket funeral, caused outrage throughout the country. The reopening of his case would have been an opportunity to bring justice to his family, which they had been denied when the white men accused of his murder – Roy Bryant and JW Milam – were first tried in 1955.

The two are now dead, but the woman who inspired the killing, Carolyn Bryant Donham, is still alive. A 2017 book quoted her recanting her claims that Till had made physical sexual advances, which had led to her husband, Roy, and his half-brother Milam, killing the 14-year-old boy.

The DOJ’s decision to close Till’s case without indicting her not only reflects the indifference America continues to show towards killings of Black boys and men, but also its inability to hold white women accountable for their role in anti-Black violence.

White womanhood and keeping Black men ‘in their place’

Sixty-six years ago, Till’s mutilated body was fished out of the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi. Roy Bryant and Milam were arrested and tried for the murder but an all-white jury acquitted them. In that trial, Donham testified that Till had grabbed her and intended to rape her – something she allegedly said was not true in an interview detailed in Tim Tyson’s 2017 book The Blood of Emmett Till.

A year after the 1955 verdict, Bryant and Milam admitted to killing Till in an interview with Look magazine. In their confession, they said their original intention was to “just whip him … and scare some sense into him”, but Till’s refusal to show any signs of fear and “know his place” forced them to kill him.

Milam said it plainly: “I like n****rs – in their place … I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, n****rs are gonna stay in their place … And when a n****r gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he’s tired of living. I’m likely to kill him.”

Keeping Black men in their place was central to how white America enforced anti-Black racism and designed segregation during the Jim Crow era, which lasted from the end of the Civil War in the 1860s to the late 1960s. It was a deliberate social hierarchy made to keep Black males out of society, while allowing white men sexual access to white and Black women.

Till’s murder and the subsequent murders of Black men and boys by lynch mobs have never been about the guilt or innocence of the accused. Lynching is a form of racial terrorism designed to halt Black people’s struggle for equality and civil rights.

Race relations scholar, John Dollard, remarked in his 1939 study of Southern towns that white Southerners believed that the two most egregious offences that a Black man could ever commit were to try to gain economic independence from whites or to rape a white woman.

During the Jim Crow era, a charge of “reckless eyeballing”, in which a Black man might look at a white woman longer than a few seconds or insinuate sexual interest in her, was considered rape and punishable by death. To protect white womanhood, any degree of violence was thought to be justified – including lynching.

It is important to recognise that white women have not only justified some of the most heinous crimes against Black men in the US, but that they themselves have committed violence against Black men. They have organised lynchings and defended Jim Crow-era policies.

In this sense, it is difficult to see how Donham is not to blame for Till’s murder. She knew that accusing a Black boy of intending to rape a white woman would inspire white men to lynch him and the lynching would be perceived as justifiable by a white society.

The DOJ’s decision not to bring charges for Till’s murder should not have been based solely on whether or not Donham recanted her testimony. Even her more serious claims about what Till did were not offences that justified his murder. The DOJ’s refusal to try her as an accomplice to murder allows her actions of inciting the killing of a young Black boy to go unpunished.

Jim Crow echoes of today

The DOJ’s decision came more than a decade after another reinvestigation of Till’s case, this time by the FBI, led to the same outcome. In 2007, a jury in Mississippi, which unfortunately was not presented with all evidence against Donham, decided against indicting her for murder.

These repeated failures of the US authorities to deliver justice for the murder of a Black boy allow white America to find comfort in knowing that the deadly racialisation of Black men during the Jim Crow era still has currency today.

It is no wonder that today, in a society several decades removed from Jim Crow, the lynching of Black men and boys continues, whether in the form of police killings or vigilante murders. And every so often, the justice system and the white public choose to rationalise these violent deaths as necessary and justifiable.

The failure to indict Donham has also confirmed that white womanhood in the US is unassailable and unaccountable for the violence it enacts against Black men and boys. And white women know it. In recent years, a series of incidents reflecting the unabashed use of white womanhood’s privilege, which have been publicised on social media, have given rise to the so-called “Karen” meme – a collective image of a privileged white woman who uses her perceived vulnerability to summon the police against an individual of colour or a group who she wants targeted.

In one of these incidents, Amy Cooper, a white woman, was taped calling the police on Christian Cooper, a Black man who had criticised her for walking her dog without a leash in New York’s Central Park. During the call, the woman feigned being attacked and requested urgent help. She faced charges of filing a false police report, but those were dropped after she completed a “therapeutic programme” addressing racial biases.

Amy Cooper, like Donham, was well aware of the potentially violent effect of her words. In a country where Black men are three times more likely to be killed by police compared with white men, an encounter with NYPD officers may have had a violent, if not fatal, outcome for Christian Cooper.

Jim Crow tropes of Black men as inherently violent, preying on vulnerable white women, who are in constant need of protection, are clearly still alive. Indeed, the Jim Crow era may be gone on paper, but its spirit lives on in American society. Black people are still getting murdered with impunity and are still so often struggling to access justice.

In fact, over the past years, there has been an ostentatious rollback of Black civil rights, decimation of affirmative action initiatives, rise of Black poverty and unemployment, and the emergence of explicitly white supremacist political platforms on the state and national level. In this context, the failure to deliver justice for Till’s murder reflects a white society recommitting itself to public displays of white supremacy and racial violence against Black people.

The New York Times said the subpoenas for Ivanka and Don Jr. 'were served on 1 December, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.' (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

The New York Times said the subpoenas for Ivanka and Don Jr. 'were served on 1 December, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.' (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

Letitia James reportedly issues subpoenas to pair as part of fraud investigation into former president’s business empire

The document was filed by lawyers for Trump in response to Letitia James’s decision to subpoena the former president himself.

Trump alleges that James’s investigation is politically motivated.

The Times said the subpoenas for Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump Jr “were served on 1 December, according to a person with knowledge of the matter”.

The paper also noted that Eric Trump, another of Trump’s adult children, was questioned in the case in October 2020. James’ office went to court to enforce a subpoena on the younger Trump brother and a judge forced him to testify after his lawyers abruptly canceled a scheduled deposition.

James’s civil investigation is focused on tax affairs at the Trump Organization, specifically whether assets were inflated or understated to influence tax valuations.

In one such alleged instance, in 2016, the Guardian reported on differing valuations of a golf club outside New York City. The headline: How Trump’s $50m golf club became $1.4m when it came time to pay tax. Trump denies wrongdoing.

The former president’s business and tax affairs are also the subject of a criminal investigation in Manhattan, in progress for more than three years and joined by James joined last May.

Last year, the then Manhattan district attorney, Cyrus Vance Jr, gained access to Donald Trump’s tax records after a multiyear fight that twice went to the US supreme court.

Before he left office at the end of last year, Vance convened a new grand jury to hear evidence as he weighed whether to seek more indictments in the investigation, which resulted in tax fraud charges in July against the Trump Organization and its longtime chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg.

Weisselberg pleaded not guilty to charges alleging he and the company evaded taxes on lucrative fringe benefits paid to executives.

Both investigations are at least partly related to allegations made in news reports and by Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal lawyer, that Trump had a history of misrepresenting the value of assets.

James’ office issued subpoenas to local governments for records pertaining to Trump’s estate north of Manhattan, Seven Springs, and a tax benefit Trump received for placing land into a conservation trust. Vance issued subpoenas seeking many of the same records.

James’ office has also been looking at similar issues relating to a Trump office building in New York, a hotel in Chicago and a golf course near Los Angeles. Her office won a series of court rulings forcing Trump’s company and a law firm to turn over records.

James and the Trump Organization did not immediately comment on the subpoenas for Ivanka and Donald Trump Jr.

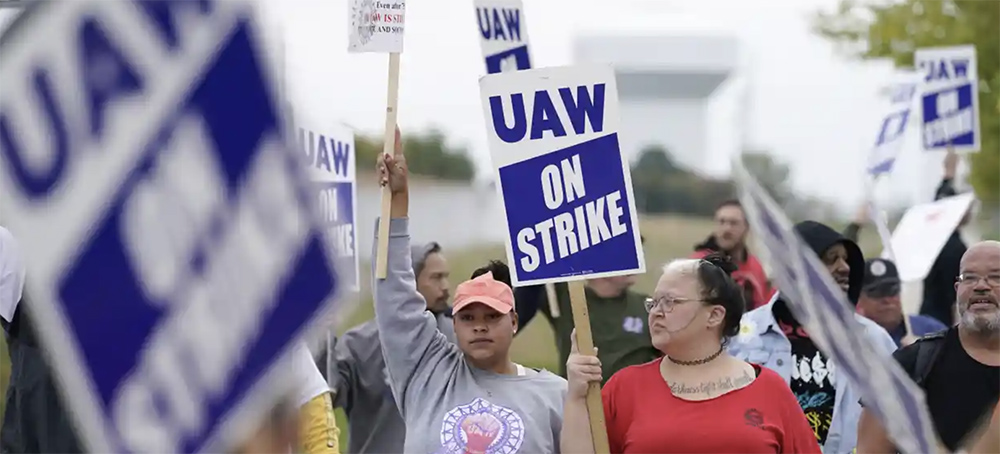

"Public approval for unions is the highest it's been in more than a half century." (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

"Public approval for unions is the highest it's been in more than a half century." (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

So far, increasingly militant workers are lacking something vital: a leader who can unite them all. Will that change?

Millions of workers are angry – angry that they didn’t get hazard pay for risking their lives during the pandemic, angry that they’ve been forced to work 70 or 80 hours a week, angry that they received puny raises while executive pay soared, angry that they didn’t get paid sick days when they got sick.

Out of this comes a question that looms large for America’s workers: will this surge of worker action and anger be a mere flash in the pan or will it be part of a longer-lasting phenomenon? The answer to this important question could turn on whether all this anger and energy are somehow transformed into a larger movement. At least for now, America’s labor leaders seem to be doing very little to tap all this energy and hope and to build it into something bigger and longer lasting. Yes, we are seeing unionization drives at this workplace and that one, but we are not seeing any bigger, broader effort to channel and transform all this worker energy and discontent into a new movement, one perhaps with millions of engaged and energetic nonunion workers, that would work in conjunction with the traditional union movement.

Worker advocates I speak to keep wondering: what are labor leaders waiting for? If not now, when?

In Joe Biden, we have the most pro-union president since Franklin Roosevelt, and public approval for unions is the highest it’s been in more than a half century. For decades, union leaders have said they are eager to reverse labor’s long decline – more than 20% of workers were in unions three decades ago, now just 10% are. Unless unions step up and do something bold, they’ll relegate themselves to continued decline.

Many labor leaders evidently think it’s impossible or improbable to turn this year’s energy and anger into a new movement or a big, new group. But building a movement from scratch isn’t impossible. 350.org was founded in 2008 by several college students and environmentalist author Bill McKibben, and within two years, it organized a mammoth Day of Climate Action with a reported 5,245 actions in 181 countries. After the horrific shootings at Marjorie Stoneman high school in Florida in 2018, a handful of students founded March for Our Lives, and within five weeks, their group had organized nationwide rallies with hundreds of thousands of people calling for gun control. Black Lives Matter also grew into a powerful national movement within a few years. None of these movements were one-shot or one-month affairs – they have become powers to contend with in policy and politics.

So why isn’t the labor movement seizing on this year’s burst of worker energy to build something bigger? I was discussing this with friend who is a professor of labor studies, and she said she thought that most of today’s union leaders were “constitutionally incapable” of building big or being bold and ambitious. She said that after decades of being on the defensive, of being beaten down by hostile corporations, hostile GOP lawmakers and hostile judicial decisions, many labor leaders seem unable to dream big or think outside the box on how to attract large numbers of workers in ways beyond the traditional one-workplace-at-a-time union drives.

But building big and outside the box isn’t impossible for labor. Just look at the Fight for $15. The strategists and SEIU leaders behind it had a vision: they wanted to push the issue of low wages into the national conversation and lift the pay floor for millions of workers. They started small, with walkouts by 200 workers at a dozen fast-food restaurants in New York City, and within two years, they built a powerful national movement that held strikes and protests in hundreds of cities. This movement ultimately got a dozen states to enact a $15 minimum wage, lifting pay for over 20 million workers.

Perhaps some brilliant, visionary workers or worker advocates will step forward to seek to channel this year’s burst of worker anger and energy into a new movement. Social media could certainly help build it, perhaps with the assistance of groups like Coworker.org, which has considerable experience engaging and mobilizing disgruntled rank-and-file workers via the internet.

For many workers, a big new group or movement could be a waystation toward unionizing: helping educate and mobilize workers to unionize, guiding them on next steps and what their rights are, and promising a pool of ready support if they seek to unionize. This new group or movement could send out bulletins telling members how they could help other workers in their community or nearby communities – perhaps help unionization drives at Amazon or Starbucks or strikers at Kellogg’s or Warrior Met Coal in Alabama or food delivery workers who are cheated out of tips and don’t have access to bathrooms.

Members of this new group could be called on to protest outside the offices of members of Congress or state lawmakers about myriad issues, perhaps raising the federal minimum wage or enacting paid family leave or the Protecting the Right to Organize Act. Or they could join rallies for voting rights or immigrant rights or against police abuses or to combat global warming.

Working America, an arm of the AFL-CIO, does some of this, mainly urging its members to vote and to contact lawmakers. To truly help reverse labor’s decline and capitalize on today’s worker anger, much more will be needed – an organization that is far more connected to workers and does far more organizing, protesting and mobilizing.

America’s labor movement is terribly balkanized, with many unions engaged in turf battles and upset that another union has (perhaps) stepped into its territory. As a result, they too often find it hard to work together. But if America’s unions are serious about wanting to strengthen worker power and reverse labor’s decline, it’s time to put past divisions behind them and figure out how to build back something bigger.

There are three main reasons that America’s labor movement has declined: first, corporate America’s fierce resistance to unions, second, the decades-long slide in factory jobs, and, third, the Republican party’s decades-long fight to weaken unions and make it tougher to unionize.

But there’s another factor behind labor’s decline that is rarely discussed – many labor leaders don’t do nearly enough to inspire workers and expand the union movement. Today’s workers could use some vigorous, visionary leaders like Mother Jones, Sidney Hillman, John L Lewis and A Philip Randolph to lead and inspire, and build something bigger. Perhaps many union leaders haven’t been hearing what I often hear from rank-and-file union members: “Lead or get out of the way.”

A scene from the January 6th riots at the Capitol. (photo: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images)

A scene from the January 6th riots at the Capitol. (photo: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images)

Where the crisis in American democracy might be headed.

January 6, 2021, should have been a pivot point. The Capitol riot was the violent culmination of President Donald Trump and his Republican allies’ war on the legitimacy of American elections — but also a glimpse into the abyss that could have prompted the rest of the party to step away.

Yet the GOP’s fever didn’t break that day. Large majorities of Republicans continue to believe the lie that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, and elected Republicans around the country are acting on this conspiracy theory — attempting to lock Democrats out of power by seizing partisan control of America’s electoral systems. Democrats observe all this and gird for battle, with many wondering if the 2024 elections will be held on the level.

These divisions over the fairness of our elections are rooted in an extreme level of political polarization that has divided our society into mutually distrustful “us versus them” camps. Jennifer McCoy, a political scientist at Georgia State University, has a term for this: “pernicious polarization.”

In a draft paper, McCoy and co-author Ben Press examine every democracy since 1950 to identify instances where this mindset had taken root. One of their most eye-popping findings: None of America’s peer democracies have experienced levels of pernicious polarization as high for as long as the contemporary United States.

“Democracies have a hard time depolarizing once they’ve reached this level,” McCoy tells me. “I am extremely worried.”

But worried about what, exactly? This is the biggest question in American politics: Where does our deeply fractured country go from here?

A deep dive into the academic research on democracy, polarization, and civil conflict is sobering. Virtually all of the experts I spoke with agreed that, in the near term, we are in for a period of heightened struggle. Among the dire forecasts: hotly contested elections whose legitimacy is doubted by the losing side, massive street demonstrations, a paralyzed Congress, and even lethal violence among partisans.

Lilliana Mason, a Johns Hopkins University political scientist who studies polarization and political violence in America, warned of a coming conflagration “like the summer of 2020, but 10 times bigger.”

In the longer term, some foresaw one-party Republican rule — the transformation of America into something like contemporary Hungary, an authoritarian system in all but name. Some looked to countries in Latin America, where some political systems partly modeled on the United States have seen their presidencies become elected dictatorships.

“The night that Trump got elected, one of my Peruvian students writing about populism in the Andes [called me] and said, ‘Jesus Christ, what’s happening now is what we’ve been talking about for years,’” says Edward Gibson, a scholar of democracy in Latin America at Northwestern University. “These are patterns that repeat themselves in different ways. And the US is not an exception.”

Others warned of a retreat to America’s Cold War past, where Democrats stoke conflict with a great power — this time, China — and abandon their commitment to multiracial democracy to appeal to racially resentful whites.

“The losers in the resolution of past democratic crises in the United States have, more often than not, been Black Americans,” says Rob Lieberman, an expert on American political history at Johns Hopkins.

America’s dysfunction stems, in large part, from an outdated political system that creates incentives for intense partisan conflict and legislative gridlock. That system may well be near the point of collapse.

Reform is certainly a possibility. But the most meaningful changes to our system have been won only after bloodshed and struggle, on the fields of Gettysburg and in the streets of Birmingham. It is possible, maybe even likely, that America will not be able to veer from its dangerous path absent more eruptions and upheavals — that things will get worse before they get better.

Part I: Conflict

Barbara Walter is one of the world’s leading experts on civil wars. A professor at the University of California San Diego, she has done field research in places ranging from Zimbabwe to the Golan Heights, and has analyzed which countries are most likely to break down into violent conflict.

Her forthcoming book, How Civil Wars Start, summarizes the voluminous research on the question and applies it to the contemporary United States. Its conclusions are alarming.

“The warning signs of instability that we have identified in other places are the same signs that, over the past decade, I’ve begun to see on our own soil,” Walter writes. “I’ve seen how civil wars start, and I know the signs that people miss. And I can see those signs emerging here at a surprisingly fast rate.”

Walter uses the term “civil war” broadly, encompassing everything from the American Civil War to lower-intensity insurgencies like the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Something like the latter, in her view, is more likely in the United States: One of the book’s chapters envisions a scenario in which a wave of bombings in state capitols, perpetrated by white nationalists, escalates to tit-for-tat violence committed by armed factions on both the right and the left.

Countries are most likely to collapse into civil war, Walter explains, under a few circumstances: when they are neither fully democratic nor fully autocratic; when the leading political parties are sharply divided along multiple identity lines; when a once-dominant social group is losing its privileged status; and when citizens lose faith in the political system’s capacity to change.

Under these conditions, large swaths of the population come to see members of opposing groups as existential threats and believe that the government neither represents nor protects them. In such an insecure environment, people conclude that taking up arms is the only recourse to protect their community. The collapse of the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s — leading to conflicts in Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo — is a textbook example.

Worryingly, all four warning signs Walter identifies are present, at least to some degree, in the United States today.

Several leading scholarly measures of democracy have found recent signs of erosion in America. Our political parties are increasingly split along lines of race, religion, and geography. The GOP is dominated by rural white Christians — a group panicked about the loss of its hegemonic place in American cultural and political life. Republican distrust and anger toward state institutions, ranging from state election boards to public health agencies to the FBI, have intensified.

Walter doesn’t think that a rerun of the American Civil War is in the cards. What she does worry about, and believes to be in the realm of the possible, is a different kind of conflict. “The next war is going to be more decentralized, fought by small groups and individuals using terrorism and guerrilla warfare to destabilize the country,” Walter tells me. “We are closer to that type of civil war than most people realize.”

How close is hard to say. There are important differences not only between the United States of today and 1861, but also between contemporary America and Northern Ireland in 1972. Perhaps most significantly, the war on terror and the rise of the internet have given law enforcement agencies unparalleled capacities to disrupt organized terrorist plots and would-be domestic insurgent groups.

But violence can still spiral absent a nationwide bombing campaign or a full-blown war — think lone-wolf terrorism, mob assaults on government buildings, rioting, street brawling.

Historical examples abound, some even in advanced democracies in the not-so-distant past. For about a decade and a half beginning in 1969, Italy suffered through a spree of bombings and assassinations perpetrated by far-right and far-left extremists that killed hundreds — the “Years of Lead.” Walter and other observers have pointed to this as a possible glimpse into America’s future: not quite a civil war, but still significant political violence that terrified civilians and threatened the democratic system.

Since Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential victory, America has seen a surge in membership in far-right militias. During the Trump era, some prominent militias directly aligned themselves with his presidency — with some groups, like the heavily armed Oathkeepers and street-brawling Proud Boys, participating in the attack on the Capitol. In May, the attorney general and the secretary of homeland security both testified before Congress that white supremacist terrorism is the greatest domestic threat to America today.

Fears of white displacement — the anxieties that Walter and other scholars pinpoint as root causes of political violence — have already fueled horrific mass shootings. In 2018, a gunman who believed that Jews were responsible for mass nonwhite immigration opened fire in a Pittsburgh synagogue, killing 11. The next year, a shooter who claimed Latinos were “replacing” whites in America murdered 23 shoppers at an El Paso Walmart that has a heavily Latino clientele.

Other forms of political conflict, like the 2021 Capitol riot, may not be as deadly but can be just as destabilizing. In 1968, a wave of demonstrations, strikes, and riots initiated by left-wing students ground France to a halt and nearly toppled its government. During the height of the unrest in late May, President Charles de Gaulle briefly decamped to Germany.

In the coming years, the United States is likely to experience some amalgam of these various upheavals: isolated acts of mass killing, street fighting among partisans, protests that break out into violence, major political and social disruption like on January 6, 2021, or in May 1968.

The most likely flashpoint is a presidential election.

Our toxic cocktail of partisanship, identity conflict, and an outmoded political structure has made the stakes of elections feel existential. The erosion of faith in institutions and growing distrust of the other side makes it more and more likely that neither party will view a victory by the other as legitimate.

After the November 2020 contest, Republicans widely accepted Trump’s “big lie” of a stolen election. With the January 6 riot and its aftermath, we now have an example of what happens when a Trumpist Republican Party loses an election — and every reason to think something like it could happen again.

An October poll from Grinnell-Selzer found that 60 percent of Republicans are not confident that votes will be counted properly in the 2022 midterms. Election officials have been inundated with an unprecedented wave of violent threats, almost exclusively from Trump supporters who believe the 2020 election was fraudulent.

And Republican elites are tossing fuel on the fire. With Trump describing slain rioter Ashli Babbitt as a martyr, Tucker Carlson producing a pro-insurrection documentary called Patriot Purge, and GOP members of Congress doing their best to obstruct the House probe into the attack’s origins, party leaders and their media allies are legitimizing political violence in the face of electoral defeat.

The behavior by Republican leaders is all the more worrisome because elites can play a major role in either inciting or containing violent eruptions. In their forthcoming book Radical American Partisanship, Mason and co-author Nathan Kalmoe ran an experiment testing the effect of elite rhetoric on Americans’ willingness to engage in violence. They found that if you show Republican partisans a message attributed to Trump denouncing political violence, their willingness to endorse it goes down substantially.

“Our results suggest loud and clear that antiviolence messages from Donald Trump could have made a difference in reducing violent partisan views among Republicans in the public— and perhaps in pacifying some of his followers bent on violence,” they write. “Instead, Trump’s lies about the election incited that violence” on January 6, 2021.

Doubts about the legitimacy of election results can also run the other way. Imagine an extremely narrow Trump victory in 2024: an election decided by Georgia, where an election law inspired by Trump’s lie gives the Republican legislature the power to seize control over the vote-counting process at the county level. If Republicans use this power and attempt to influence the tally in, say, Fulton County — a heavily Democratic area including Atlanta — Democrats would cry foul. There would likely be massive protests in Atlanta, Washington, DC, and many other American cities.

One can then imagine how that could spiral. Armed pro-Trump militias like the Oathkeepers and Proud Boys show up to counterprotest or “restore order”; antifa marchers square off against them. The kind of street fighting that we’ve seen in Portland, Oregon, and Charlottesville, Virginia, erupts in several cities. This is Mason’s “summer of 2020, but 10 times bigger” scenario.

Maybe these melees stay contained. But violence may also beget more violence; before you know it, America could be engulfed in its own Years of Lead.

It’s all speculative, of course. And this worst-case scenario may not even be likely. But Walter urges against complacency.

“Every single person I interviewed who’s lived through civil war, who was there as it emerged, said the exact same thing: ‘If you had told me it was going to happen, I wouldn’t have believed you,’” she warns.

Part II: Catastrophe

In McCoy and Press’s draft paper on “pernicious polarization,” they found that only two advanced democracies even came close to America’s sustained levels of dangerously polarized politics: France in 1968 and Italy during the Years of Lead.

The broader sample, which includes newer and weaker democracies in addition to more established ones, isn’t much more encouraging. The scholars identified 52 cases of pernicious polarization since 1950. Of these, just nine countries managed to sustainably depolarize. The most common outcome, seen in 26 out of the 52 cases, is the weakening of democracy — with 23 of those “descending into some form of authoritarianism.”

Almost all the experts I spoke with said that America’s coming period of political struggle could fundamentally transform our political system for the worse. They identified a few different historical and contemporary examples that could provide some clues as to where America is headed.

None of them is promising.

Viktor Orbán’s America

Since coming to power in 2010, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has systematically transformed his country’s political system to entrench his Fidesz party’s rule.

Fidesz gerrymandered parliamentary districts and packed the courts. It seized control over the national elections agency and the civil service. It inflamed rural Hungarians with anti-immigrant demagoguery in propaganda outlets and attacked the country’s bastions of liberal cultural power — persecuting a major university, for example, until it was forced to leave the country.

The party’s opponents have been reduced to a rump in the national legislature, holding real power only in a handful of localities like the capital city of Budapest. A desperate campaign by a united opposition in the 2022 election faces an uphill battle: a polling average from Politico EU has shown a Fidesz advantage for the past seven months.

There was no single moment when Hungary made the jump from democracy to a kind of authoritarianism. The change was subtle and slow — a gradual hollowing out of democracy rather than its extirpation.

The fear among democracy experts is that the US is sleepwalking down the same path. The fear has only been intensified by the American right’s explicit embrace of Orbán, with high-profile figures like Tucker Carlson holding up the Hungarian regime as a model for America.

“That has always been my view: we’ll wake up one day and it’ll just become clear that Democrats can’t win,” says Tom Pepinsky, a political scientist at Cornell who studies democracy in Southeast Asia.

In this scenario, Democrats fail to pass any kind of electoral reform and lose control of Congress in 2022. Republicans in key states like Georgia, Arizona, North Carolina, and Wisconsin continue to rewrite the rules of elections: making it harder for Democratic-leaning communities to vote, putting partisans in charge of vote counts, and even giving GOP-controlled state legislatures the ability to override the voters and unilaterally appoint electors to the Electoral College.

The Supreme Court continues its assault on voting rights by ruling in favor of a GOP state legislature that does just that — embracing a radical legal theory, articulated by Justice Neil Gorsuch, that state legislatures have the final say in the rules governing elections.

These measures, together with the built-in rural biases of the Senate and Electoral College, could make future control of the federal government a nearly insurmountable climb for Democrats. Democrats would still be able to hold power locally, in blue states and cities, but would have a hard time contesting national elections.

Political scientists call this kind of system “competitive authoritarianism”: one in which the opposition can win some elections and wield a limited degree of power but ultimately are prevented from governing due to a system stacked against them. Hungary is a textbook example of competitive authoritarianism in action — and, quite possibly, a glimpse into America’s future.

The Latin American path to a strongman

The rising hostility between the two parties has made it harder and harder for either party to get the necessary bipartisan support to pass big bills. And with its many veto points — the Senate filibuster being the most glaring — the American political system makes it exceptionally difficult for any party to pass major legislation on its own.

The result: Congressional authority has weakened, and there’s a rising executive dependence on unilateral measures, such as executive orders and agency actions. Only rarely do presidents repudiate powers claimed by their predecessors; in general, the authority of the executive has grown on a bipartisan basis.

So long as America is wracked by partisan conflict, it’s easy to see this trend getting worse. In response to an ineffectual Congress and a party faithful that demands victories over their hated enemies, presidents seize more authority to implement their policy agenda. As clashes between partisans turn more bitter and more violent, the wider public begins crying out for someone to restore order through whatever means necessary. Presidents become increasingly comfortable ruling through emergency powers and executive orders — perhaps even to the point of ignoring court rulings that seek to limit their power.

Under such conditions, there is a serious risk of the presidency evolving into an authoritarian institution.

“My bet would be on deadlock as the most plausible path forward,” says Milan Svolik, a political scientist at Yale who studies comparative polarization. “If there’s deadlock ... to me it seems [to threaten democracy] by the huge executive powers of the presidency and the potential for their abuse.”

Such a development may be more acceptable to Americans than we’d like to think. In a 2020 paper, Svolik and co-author Matthew Graham asked both Republican and Democratic partisans whether they would be willing to vote against a politician from their party who endorses undemocratic beliefs. Examples include proposals that a governor from their party “rules by executive order if [opposite party] legislators don’t cooperate” and “ignores unfavorable court rulings from [opposite party] judges.”

They found that only a small minority of voters, roughly 10 to 15 percent, were willing even in theory to vote against politicians from their own party who supported these kinds of abuses. Their research suggests the numbers would likely be substantially lower in a real-world election.

“Our analysis reveals that the American voter is not an outlier: American democracy may be just as vulnerable to the pernicious consequences of polarization as are electorates throughout the rest of the world,” Svolik and Graham conclude.

Globally, some of the clearest examples of a descent into presidential absolutism come from Latin America.

Unlike most European democracies, which employ parliamentary systems that select the chief executive from the ranks of legislators, most Latin American democracies adopted a more American model and directly elect their president.

In the late 20th century, social and economic divisions in countries like Brazil and Argentina led to legislative gridlock and festering policy problems; presidents attempted to solve this mess by assuming a tremendous amount of power and ruling by decree. Political scientist Guillermo O’Donnell termed these countries “delegative democracies,” in which voters use elections not to elect representatives but to delegate near-absolute power to one person.

“Presidents get elected promising that they — strong, courageous, above parties and interests, machos — will save the country,” O’Donnell writes. “In this view other institutions — such as Congress and the judiciary — are nuisances.”

The rise of delegative democracy in Latin America exposed a flaw at the heart of American-style democracy: how the separation of executive and legislative power can grind government to a halt, opening the door to unpredictable and even outright undemocratic behavior.

“I think what we’re going to have is continued dysfunction ... that could lead people to say, as we’ve seen in so many other countries, especially in Latin America, ‘let’s just have a strongman government,’” says McCoy, the scholar of “pernicious polarization.”

In some cases, like contemporary Ecuador, presidents were granted new powers by national referenda and pliant legislatures. But in others, like Peru in the 1990s, the president seized them more directly. An outsider elected in 1990 amid a violent insurgency and a crisis of public confidence in the Peruvian elite, President Alberto Fujimori frequently clashed with a legislature controlled by his opponents. In response, he took unilateral actions culminating in 1992’s “self-coup,” where he dismissed the legislature and ruled by decree for seven months — until he could hold elections to legitimize the power grab. His regime, authoritarian in all but name, persisted until 2000.

Much like the slide toward competitive authoritarianism, a move toward Fujimorism in America would happen gradually — one executive order at a time — until the US presidency has become a dictatorship in many of the ways that count.

A civil rights reversal

Americans do not need to go abroad in search of examples of democratic breakdown.

Jim Crow, primarily remembered as a form of racial apartheid, was also a kind of all-American autocracy. Southern states were one-party fiefdoms where Democratic victory was assured, in large part due to laws denying Black people the right to vote and participate in politics.

The Jim Crow regime emerged out of a national electoral crisis — the contested 1876 election, in which neither party candidate was initially willing to admit defeat. In 1877, Democrats agreed to award Republican Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency on the condition that he withdraw the remaining federal troops stationed in the South. The result was the end of Reconstruction and the victory of so-called Redeemers, Southern Democrats who aimed to rebuild white supremacist governance in the former Confederacy.

The Compromise of 1877 is perhaps the most dramatic example of a common pattern in American history, ranging from the Northern Founders’ Faustian bargain with enslavers to the New Deal’s sops to racist Southern Democrats to the politics of welfare and crime in the 1980s and ’90s: When major political factions clash, their leaders come to arrangements that sacrifice Black rights and dignity.

“In the [early and middle] 20th century, polarization looks low,” Lieberman, the Johns Hopkins scholar, explains. “That’s because African Americans are essentially written out of the political system, and there’s an implicit agreement across the mainstream to keep that off of the agenda.”

America is obviously very different today. But as in the past, divides over race and identity are the fundamental driver of deep partisan polarization — and whites are still over 70 percent of the population. It’s not hard to conjure up a scenario, borrowing from both our distant and not-so-distant past, in which minority rights are once again trampled so whites can get along.

Imagine a future in which, with the benefit of structural advantages, Republican electoral victories pile up. Protests against GOP rule and racial inequality once again turn ugly, even violent. In response, an anxious Democratic Party feels that it has little choice but to engage in what the Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon calls “white appeasement politics”: Think Bill Clinton’s attack on the rapper Sister Souljah, his enactment of welfare reform, and his “tough on crime” approach to criminal justice.

Democrats dial back their commitment to policies aimed at addressing racial inequality, including abandoning any serious attempts at reforming the police, defending affirmative action, reducing discrimination in the housing market, or restoring the Voting Rights Act. They also move to ramp up deportations (which has happened in the past) and substantially lower legal immigration levels.

Democrats and Republicans primarily compete over cross-pressured whites, while Black and Latino influence over the system is diminished. America’s status as a multiracial democracy would be questionable at best.

“That is a real possibility,” warns Hakeem Jefferson, a political scientist at Stanford who studies race and American democracy.

And there’s another twist to this scenario that some experts brought up: Democrats attempting to unify the country through conflict with a foreign enemy. The theory here is that low polarization in postwar America wasn’t solely an outgrowth of a racist detente; the threat of nuclear conflict with the Soviets also played a role in uniting white America.

There’s one obvious candidate for an adversary. “I’ve always thought Americans would come together when we realized that we faced a dangerous foreign foe. And lo and behold, now we have one: China,” the New York Times’s David Brooks wrote in 2019. “Mike Pence and Elizabeth Warren can sound shockingly similar when talking about China’s economic policy.”

The result would be a new equilibrium, one where China displaces immigration and race as the defining issue in American public life while the white majority returns to a state of indifference to racial hierarchy.

Is this scenario likely? There are good reasons to think not.

Jefferson thinks the makeup of the modern Democratic Party, in particular, poses a significant barrier to this kind of backsliding. Racial justice and pro-immigration groups are powerful constituencies inside the party; any Democrat needs significant Black and Latino support to win on the national level. The progressive turn on race among liberal whites in the past few years — the so-called Great Awokening — means that even the white Democratic base is likely to punish racially conservative candidates in primaries.

And the best research on China and polarization, a 2021 paper by Duke professor Rachel Myrick, finds ramping up tensions with Beijing is more likely to divide Americans than to unite them. “I have difficulty imagining the set of circumstances under which we’re going to see bipartisan cooperation in a way that’s analogous to the Cold War,” she tells me.

But in the long arc of American history, few forces have proven more politically potent than the politics of fear and racial resentment. While their reconquest of the Democratic Party may seem unlikely now, stranger things have happened — like the party of Lincoln becoming the party of Trump.

Part III: Change

Between 1930 and 1932, the Finnish government was shaken to its core by a fascist uprising.

In 1930, a far-right nationalist movement called Lapua rocketed to prominence, rallying 12,000 followers to march on the capital, Helsinki. The movement’s thugs kidnapped their political opponents; the country’s first president, who had finished his term just five years prior, was one of their victims.

In 1931, the Lapua-backed conservative Pehr Evind Svinhufvud won the country’s presidential election. The movement became even more militant: In March 1932, Lapua supporters seized control of the town of Mäntsälä.

But the attack on Mäntsälä did not cow the Finnish leadership: It galvanized them to action. Svinhufvud turned on his Lapua supporters and condemned their violence. The armed forces surrounded Mäntsälä and forced the rebels to put down their arms. Leading political parties worked to limit Lapua’s influence in the legislature. The movement withered and ultimately collapsed.

The Finnish story is one of three examples in a 2018 paper examining democratic “near misses”: cases where a democracy almost fell to autocratic forces but managed to survive. The paper’s authors, University of Chicago legal scholars Tom Ginsburg and Aziz Huq, find a clear pattern in these near misses — that political elites, including both politicians and unelected officials, can change the way a crisis unfolds.

“Sustained antidemocratic mobilization is hard to defeat, but a well-timed decision by judges, generals, civil servants, or party elites can make all the difference between a near miss and a fatal blow,” they write.

In the United States, we have plenty of reasons for pessimism on this front.

During the Trump years, shocking developments and egregious violations of long-held norms would invariably give rise to a hope that this, finally, was the moment where Republican elites would abandon him. The aftermath of the Capitol riot, a literal violent uprising, could have been their Mäntsälä — a moment when it became clear that the extremists had gone too far and the American conservative establishment would pull us back from the brink.

In the days following the attack, that seemed like a live possibility. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell gave a fiery speech on January 19 condemning the uprising and Trump’s role in encouraging it. Other establishment Republicans who had previously defended Trump, like Sen. Lindsey Graham, also openly criticized his conduct.

But McConnell and the bulk of the Republican Party reverted to form, refusing to support any real consequences for Trump’s role in the insurrection or make any effort to break his hold on the GOP faithful. There is no American Svinhufvud with the power to change the Republican Party’s direction.

With one of America’s two major parties this far gone, it’s clear that preserving democracy will not be a bipartisan effort, at least not at this moment. But Democrats do currently control government, and there are things they can do to improve America’s long-term outlook.

Some of the needed reforms are obvious. To reduce the risk of catastrophe, Congress could eliminate the Senate filibuster, pass new restrictions on executive powers, and ban both partisan gerrymandering and partisan takeovers of the vote-counting process.

Even more fundamental reforms may be necessary. In his book Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop, political scientist Lee Drutman argues that America’s polarization problem is in large part a product of our two-party electoral system. Unlike elections in multiparty democracies, where leading parties often govern in coalition with others, two-party contests are all-or-nothing: Either your party wins outright or it loses. As a result, every vote takes on apocalyptic stakes.

A new draft paper by scholars Noam Gidron, James Adams, and Will Horne uncovers strong evidence for this idea. In a study of 19 Western democracies between 1996 and 2017, they find that ordinary partisans tend to express warmer feelings toward the party’s coalition partners — both during the coalition and for up to two decades following its end.

“In the US, there’s simply no such mechanism,” Gidron told me. “Even if you have divided government, it’s not perceived as an opportunity to work together but rather to sabotage the other party’s agenda.”

Drutman argues for a combination of two reforms that could move us toward a more cooperative multiparty system: ranked-choice voting and multimember congressional districts in the House of Representatives.

In ranked-choice elections, voters rank candidates by order of preference rather than selecting just one of them, giving third-party candidates a better chance in congressional elections. In a House with multimember districts, we would have larger districts where multiple candidates could win seats to reflect a wider breadth of voter preferences — a more proportional system of representation than the winner-take-all-status quo.

But it’s very hard to see how these reforms could happen anytime soon. Extreme polarization creates a kind of legislative Catch-22: Zero-sum politics means we can’t get bipartisan majorities to change our institutions, while the current institutions intensify zero-sum competition between the parties. Even Sen. Mitt Romney, an anti-Trump Republican, voted against advancing the For the People Act, which regulates (among other things) partisan gerrymandering and campaign finance — a relatively limited set of changes compared to those proposed by many political scientists.

Drutman told me that the most likely path forward involves a massive shock to break us from our dangerous patterns — “something that sets enough things in motion that it creates a possibility [for radical change].”

This brings us back to the specter of political violence that hangs over post-January 6 America.

Is there a point where upheaval and instability, should they come, get to be too unbearable for enough of our political elites to act? Will it take the wave of far-right terrorism Walter fears for Republicans to have a Mäntsälä moment and turn on Trumpism? Or a truly stolen election, with all the chaos that entails, for Americans to flood the streets and demand change?

America’s political system is broken, seemingly beyond its normal capacity to repair. Absent some radical development, something we can’t yet foresee, these last few unsettling years are less likely to be past than prologue.

A young climate activist joins tens of thousands of others in a protest march in Glasgow during the COP26 summit. (photo: Jonne Roriz/Bloomberg News)

A young climate activist joins tens of thousands of others in a protest march in Glasgow during the COP26 summit. (photo: Jonne Roriz/Bloomberg News)

From climate change to nukes, the world is showing no signs of the cooperation we need to survive.

In the case of the film, it does not give away too much to suggest that doing the right thing is a challenge. The film is not just a parable about our inertia when it comes to the ever worsening, nearly irreversible climate crisis—it is a reminder that the idea that the planet will effectively unite in the interest of self-preservation is itself a romantic myth.

The coronavirus pandemic has shown that bona fide global cooperation is more fanciful and out of reach than ever.

It was a very different sort of Hollywood product, President Ronald Reagan, who—with Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev—helped promote this fantasy of an enlightened global community. During a 1985 summit in Geneva, their conversation took an odd turn. As reported by Gorbachev himself, “President Reagan suddenly said to me, ‘What would you do if the United States were suddenly attacked by someone from outer space? Would you help us?’” Gorbachev responded, “No doubt about it.” Reagan replied, “We too.”

Our modern experience with shared existential threats tells another story.

The climate crisis is, of course, one part of the tale. The ancient Greeks contemplated whether deforestation or draining swamps might impact rainfall. But warnings that humans could cause global warming by producing carbon dioxide have themselves been around a long time. Nineteenth-century scientists understood the concept and, in 1896, Svante Arrhenius published the first paper explicitly warning of this threat.

We know the rest of the story. Although today there is very nearly universal agreement among scientists that global warming is real but that its consequences are likely to be severely disruptive—costing billions of dollars and threatening millions of lives—the governments of the planet Earth have moved far too slowly. In just this past year, we effectively exceeded the warming targets set during the Paris 2015 climate talks, we have seen record-breaking heat, faster sea-level rise, shrinking polar ice caps, and devastating weather… and still the COP 26 talks in Edinburgh produced underwhelming results.

Here in the U.S., Sen. Joe Manchin and his GOP allies blocked major new funding for climate programs—and he actively defended the fossil-fuel interests so prominent in his home state of West Virginia. We could be on a path to sea levels rising as much as seven feet by the end of the century and right now it seems unlikely we’ll be able to reverse those trends.

Other climate-related existential threats—from lack of water to famine—have more typically produced conflict than cooperation between neighboring states. Making matters worse is that most of our international institutions were designed to be weak—to let big countries like the U.S. have their way, to support the initiatives of a rich few states, and not to be able to impose their will on individual countries in an effective way. As a result, many responses to global threats are either weak or ad hoc.

But it’s not just climate. Another existential threat we have faced for almost eight decades is that posed by nuclear weapons. We know that nuclear warfare would be horrific, and that a nuclear exchange by superpowers like the U.S. and Russia or China could destroy the planet. While we have had arms agreements and efforts to contain the spread of such weapons, look at the headlines. Iran is nearing the capacity to manufacture nuclear warheads. North Korea reminds us regularly it has joined the nuclear club. Israel and India got such weapons half a century ago. Pakistan did in 1998.

Today, there are more than 13,000 nuclear warheads known to exist worldwide, almost 12,000 of which belong to the U.S. and Russia. What’s more, we have let some key arms agreements lapse in recent years, and have made precious little progress on the big, bold ideas that enlightened self-interest (or common sense) might dictate, like eliminating nuclear weapons altogether. What’s more, there have been proponents, such as former President Trump, of investing in “smaller”—which is to say more usable—nuclear weapons, which would increase the risks we face. In other words, more than three-quarters of a century after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the threat of nuclear catastrophe remains and, in many respects, it is getting worse.

And you’ll be very disappointed if you think we’ve got good global mechanisms in place to address next-generation threats from cyber to AI-empowered weapons to biowarfare.

COVID-19, of course, is another menace that has defied cooperation for nearly two years of death and despair.

For all the rhetoric about the need for global solutions, the response of the international community to containing the spread of the pandemic has been woefully inadequate. The U.S. has committed over 1 billion doses to the international community, but the need is perhaps 11 times that. Even those commitments are slow in delivery and distribution. Nations, including the U.S., have been careful to build vaccine, testing, and PPE stockpiles before sharing with other countries.

The result has been major outbreaks in the developing world, where estimates are that the poorest countries may not receive the vaccine until 2023. Only a tiny percentage of people in those countries have received even one dose of vaccine. While vaccinating half the world’s population is not an accomplishment to be minimized, the reality is that 40 countries have vaccinated less than a quarter of their populations. Other issues like export bans, production levels, intellectual-property barriers, and supply-chain blockages are solvable, but are often gummed up by industries or politicians acting just like those in Don’t Look Up do: based on self-interest, ignorance, or a toxic combination of both.

The result of course, has been the emergence of new variants in the undervaccinated parts of the world that ultimately affect the whole planet and prolong the pandemic. For Americans, the short-sightedness of government leaders is familiar. While the Biden Administration has done a remarkable job in getting Americans vaccinated, they have faced resistance at every step of the way from red-state governors who seem willing to sacrifice their own people in order to pander to the leaders of their party and the most extreme elements of their base. The vaccine and the know-how to contain the disease are available everywhere. But people living in counties that voted for Donald Trump are almost three times as likely to die of COVID-19 as those in areas that voted for President Biden.

There you have it in microcosm. If the U.S. can’t get its act together to combat a disease that has infected more than 50 million Americans and has killed about 825,000, how can we expect the planet earth to do any better? You would think survival mattered enough to look past our differences. Apparently not.

Higher life forms elsewhere in the universe will no doubt look at this and see it as an invitation, Reagan and Gorbachev had it wrong. We’re not a planet that is likely to come together to put up much of a fight against alien invaders.

Supporters of former Brazilian judge and Justice Minister Sergio Moro arrive at an event where Moro announced his affiliation to the Podemos party in Brasília, Brazil, on Nov. 10, 2021. (photo: Evaristo Sa/AFP/Getty Images)

Supporters of former Brazilian judge and Justice Minister Sergio Moro arrive at an event where Moro announced his affiliation to the Podemos party in Brasília, Brazil, on Nov. 10, 2021. (photo: Evaristo Sa/AFP/Getty Images)

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Jair Bolsonaro, and Sergio Moro, three major candidates in Brazil’s 2022 election, have a turbulent and intertwined past.

The right worshipped Moro for his role as the judge who put former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva behind bars on corruption charges. The popularity propelled Moro to high office, as justice minister under far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who won the 2018 election after the frontrunner, Lula, was made ineligible by Moro’s conviction.

For all three men, the tables have now dramatically turned. The Supreme Court freed Lula and vacated Moro’s rulings, determining that the judge acted with bias after The Intercept revealed compromising, secret chat logs showing illicit collusion between Moro and the prosecutors. Attempts to revive the cases against Lula have subsequently been thrown out, leaving Moro’s legacy damaged. It was yet another hit to Moro’s credibility, which was decimated during his brief, controversial, and at times humiliating tenure in the Bolsonaro government, culminating in an anti-climactic, acrimonious departure in 2020.

Following a high-paying consulting gig in Washington and even work on behalf of an Israeli billionaire accused of corruption and rights abuses, Moro is now running for president himself. Facing off against both his far more charismatic archnemeses, though, the former judge is struggling to break into double digits in polling.

A resurgent Lula, on the other hand, is ascendant, polling at nearly 50 percent with the lowest negative numbers of any major candidate. For his part, Bolsonaro, battered by an ailing economy and his administration’s disastrous handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, is only managing to attract just over 20 percent of voters.

Running From Scandals

During his book tour, the unofficial launch of his presidential campaign, Moro conspicuously dodged inconvenient questions about the mounting scandals that undercut his carefully crafted image. Interviews tend only to be granted to friendly outlets. At the book launch, Moro refused to take questions from the press and pre-signed books to avoid a fan meet-and-greet where questions could’ve been sprung on him.

The autobiography, “Against the System of Corruption,” lays out the official narrative of his professional life but brazenly elides the secret chat logs first published by The Intercept in June 2019. Moro has refused to acknowledge the archive’s authenticity, though he has claimed no wrongdoing was exposed in the chats. In his book, Moro also presents himself as an earnest political outsider who was deceived by a president that proved to be unscrupulous — a self-serving framing that ignores decades of Bolsonaro’s corruption and indecency.

The reputational damage caused by Moro’s partnership with Bolsonaro was easy to see coming: The chat records show that prosecutors from the Operation Car Wash, the very corruption investigation that Moro had overseen, clearly predicted the eventual outcome. “As Justice Minister, I think it will give rise — with reason — to arguments about the politicization of Car Wash,” one prosecutor wrote in concurrence with his colleagues.

From his perch in the Justice Ministry, Moro helped Bolsonaro shake off investigations into his family and worked alongside politicians accused of corruption. Moro’s positions and authority were repeatedly undermined by Bolsonaro. His first signature legislative package included a Bolsonaro-backed proposal that actually served to promote corruption by making it easier for police officers to escape punishment for crimes committed in the line of duty.

Moro himself has admitted to potential crimes under Brazilian law, including negotiating a special pension for his ministerial role. Bolsonaro accused the former justice minister of trying to negotiate a Supreme Court appointment in exchange for lending his credibility to the far-right administration.

This week, as part of the evidence collection in an investigation into potential wrongdoing by Operation Car Wash officials, a high court ordered the Washington-based consulting firm Moro worked for to turn over records about what the former judge did and the pay he received.

In a promotional interview last week, Moro declined an invitation to appear alongside Ciro Gomes, a center-left presidential hopeful, for a public conversation. Gomes, a former governor and federal minister, is known for an incisive debating style and an impressive ability to corner adversaries with wonky data points on a broad range of subjects. Moro, by contrast, has been criticized for his political inexperience and a lack of specifics in his platform.

“Ciro first needs to drop this offensive and aggressive posture in order for us to open up a dialogue,” Moro said. Gomes, a vocal critic of Car Wash, responded on YouTube the next day: “He doesn’t want to debate me because I’m going to say he’s corrupt.”

Recent polls show the two candidates neck and neck in the fight for a distant third-place finish — making neither likely to advance to a second-round runoff should Lula and Bolsonaro stay in the race.

Moro, Media Darling

While Brazil’s mainstream media often ignores Lula or casts him in a negative light, Moro suffers no shortage of glowing coverage — despite his lackluster polling numbers and vague policy proposals.

In November, Moro joined the relatively small, right-wing Podemos political party, the first formal requirement in a presidential bid. As journalist Fagner Torres noted, in the weeks following the affiliation ceremony, Moro was featured on the front page of the influential O Globo newspaper once every three days. Other major newspapers, radio stations, and television networks were similarly attentive. There has been little, if any, critical coverage of Moro’s scandals.

“Moro represents a part of Brazilian society, which includes a large share of the media, that does not accept Lula and is ashamed of its previous support for Bolsonaro,” said Fabio de Sa e Silva, an assistant professor of Brazilian studies at the University of Oklahoma. “His strategy will be to try to sustain the character that was created for him. I think this character is out of step with Brazil today, but it is a character that corresponds with many of the interests of some powerful groups in Brazil.”

For Moro, the media brought him to fame through his anti-corruption stances — and corruption has continued to be his focus, rather than the economic and health problems foremost on Brazilians’ minds. It has so far worked in the press, including the international business press, if not quite the polls: Moro is hailed as a “third way” candidate: a nonpartisan, unifying alternative to the left-right “polarization” between Lula and Bolsonaro.

Moro is using this media narrative to try to capture the same winning coalition Bolsonaro built in 2018, when the far-right candidate enjoyed positive media coverage. Moro’s critics, though, said his try for the same coalition reveals a campaign that essentially puts a more polite patina on the same sort of far-right politics leveraged by the brash Bolsonaro.

Sa e Silva pointed to right-wing military figures who had served in the Bolsonaro government but became disenchanted and now embrace Moro’s candidacy. “It is further evidence that Moro, if he truly represents an alternative path,” Sa e Silva said, “is an alternative path to Bolsonarismo and not away from so-called polarization.”

A Conciliatory Lula

In contrast to Moro, Lula has been charting a course of conciliation for 2022 — much as he did during his first presidential victory in 2002. Although he has not officially confirmed he is running for president, he is far along in the process of courting Geraldo Alckmin of the center-right Brazilian Social Democracy Party, to be his vice president. The alliance with a former rival is designed to soften opposition to Lula’s candidacy from the nation’s business elite and indicate a desire to build a broad coalition.

In stark contrast to Bolsonaro’s growing global isolation, Lula has been traveling the world, being fêted by world leaders. Yet Brazilian mainstream media outlets were slow to cover the warm receptions Lula received on his trips.

Instead, the Brazilian press has taken a hostile posture toward Lula. When the former president did an interview with the Spanish newspaper El País that won positive headlines in Europe, Brazilian corporate media focused on an incomplete clip from his interview about the recent election in Nicaragua to accuse Lula of being an enemy of democracy — even comparing him to Bolsonaro.

“The media was very hostile to Lula during Operation Car Wash and has not been friendly so far this election cycle,” said Marcelo Semer, a state appeals court judge and author. “The Bolsonaro administration has been a complete tragedy, but the media still clearly prefers Moro — the candidate who is most ideologically aligned with Bolsonaro — to win next year. It is normalizing Moro’s candidacy and protecting him just like Bolsonaro was protected in 2018.”

An imagined windfarm. (image: Thomas Jackson/Getty Images)

An imagined windfarm. (image: Thomas Jackson/Getty Images)

Despite stereotypes, there's really only one characteristic they all share: They hate being told what to do.

I’m drawn to the big landscapes that surround them, but most of all, I think, I value my membership in these cranky, intimate communities. I like that my neighbors come from many different walks of life, and that they regularly (and sometimes uncomfortably) puncture my assumptions about their experiences and interests and political leanings — just as I puncture theirs. I like that I know the librarians by name, and that they know when I have books overdue.

Since the 2016 election, the national media has frequently used the term “rural Americans” as shorthand for middle-aged, white Trump supporters. The conflation obscures the fact that about one out of five rural Americans identify as Black, Latino, or Indigenous, and that immigrants are responsible for much of the recent population growth in rural areas. An estimated 15 to 20 percent of LGBTQ Americans live in rural places, and rural youth are now just as likely to identify as LGBTQ as their urban peers.

Rural Americans are also politically diverse; while it’s accurate to say that I live in a deep-red county, it’s also accurate to say that I live in a powder-blue town surrounded by precincts that range from pale pink to brick red. And though both rural and urban Americans are more politically polarized than they used to be, the politics of rural voters don’t always fit neatly into partisan categories. Many rural people are deeply skeptical of both parties. Others are suspicious of government regulations, but also critical of the environmental damage done by unregulated industry. (The decline of local news, which is most acute in rural places, means that nuanced reporting on rural issues is scarce, and that media stereotypes often go unchallenged.)

In my experience, there’s only one characteristic that essentially all rural people share: We hate being told what to do, whether by a neighbor who doesn’t like our political yard signs or a state wildlife official charged with enforcing new hunting regulations. When it comes to addressing climate change, this reflexive independence can pose a stubborn obstacle, but it also holds opportunity — renewable energy, for instance, can appeal to those who prize autonomy. Turning opportunity into progress, though, requires a willingness to see rural people clearly.

Rural Americans value the protection of their air, water, and soil as much — or even more — than their urban counterparts, but boy do they use different words for it. While progressive urban activists might consider “conservation” and “environmental” to be more or less interchangeable, for instance, many rural people may cautiously accept the former but reject the latter, assuming that those who call themselves conservationists will be less confrontational and friendlier to hunting, fishing, and farming. (That said, plenty of people worldwide are wary of the term “conservation,” too, given the movement’s history of violating the land claims of Indigenous and other rural people.)

“‘Environmentalism’ is seen as intrusive, top down, and driven by people who don’t make their living from the land,” says Virginia farmer and rural economic development consultant Anthony Flaccavento. “Anyone who has the term in the name of their organization is going to have a hell of a time, even if they’re trying to come down on the side of farmers and fishermen.”

Farmers who support sustainable agricultural practices may nonetheless react to terms like “regenerative agriculture,” offended by the implication that other forms of agriculture are somehow non-regenerative. Campaigns against the environmental and economic sins of “Big Ag,” however warranted and well-documented, are similarly unlikely to sit well with farmers who are forced, however unwillingly, to depend on Big Ag for a living.

“Climate change” is another loaded term, given that many rural people associate climate fixes with government regulation. As Kate Yoder reported for Grist recently, urban climate activists may make more headway with potential rural allies by talking about the need to mitigate and adapt to floods, fires, and heatwaves — independent of their root causes.

Like almost all urban-rural misunderstandings, these and other language barriers result from both real grievances and deliberately inflated resentments. But by avoiding hyper-polarized words and phrases, climate activists can start a conversation that would otherwise be shut down.

Over the past 40-plus years, U.S. economic policies have widened the gaps between rich and poor, Black and white, and rural and urban. Farmers and farmworkers have been hit hard by corporate consolidation, losing land and livelihoods to international agricultural conglomerates; many of the manufacturers that employed generations of rural families have moved overseas. Recent history has compounded these troubles, as rural employment rates have never recovered from the Great Recession, and rural economies have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

The cost of rural living is rising, too: In my small town, for instance, telecommuters with far deeper pockets than I have are driving up real estate prices, and trailer parks are being replaced with second homes. These and other genuine economic disparities aren’t just practical problems; they’re often emotionally agonizing, and in recent years they’ve increased the risk of farmers and farmworkers dying by suicide. They’ve also created a rural audience receptive to divisive messages, with some eager to blame their troubles on city people, Democrats, government workers, and — in the case of some white rural residents — people of color. (The sheriff in my county recently attracted national attention, and not a little local support, by threatening to arrest any public employees, from schoolteachers to county commissioners, who tried to enforce COVID-related health regulations.)

Meanwhile, the real causes of rural suffering, such as inadequate healthcare, chronically underfunded schools and the persistent technology gap, are rarely prioritized by either party — fueling yet more toxic resentment. The result, says Flaccavento, is that “many rural people, especially white folks, may simultaneously have a greatly exaggerated sense of grievance and real and long-standing grievances that have not been addressed.”

Bridging the rural-urban divide is rarely easy. Rural resentment of city dwellers is pervasive and sometimes poisonous. Rural places can be hard to get to, and can take years to get to know. At the same time, rural places are often heartbreakingly gorgeous and surprisingly diverse, and they’re almost guaranteed to upend whatever expectations you might bring to them. By taking the time to understand rural issues, and by seeking climate solutions that restore livelihoods as well as landscapes, the climate movement can broaden its reach and increase its power. Which looks more and more like a matter of survival, no matter where you happen to live.

Some of the most promising solutions to the climate crisis lie in the rural places I call home. The conservation of Indigenous lands and privately owned rural landscapes is central to the Biden administration’s America The Beautiful plan, an ambitious initiative designed to benefit the climate as well as biodiversity. Much of our wind and solar energy production — existing and potential — is located in rural areas, as are our best remaining opportunities to sequester carbon in forests and grasslands.

Yet surveys of rural Americans find that most of us are wary of concerted climate action. We value clean water, wildlife, and parks as much as urban dwellers, and we’re at least as well-informed about environmental policy. We’re also facing some of the worst effects of climate change, from megafires to storm surges to landslides to drought-induced crop failures. But in our experience, environmental regulations tend to burden the wrong people. Government policies designed to stablize the climate, many of us worry, will mean more of the same.