Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Dispatches from a moral panic

The event, called the Festival of Hope, was a fundraiser for the anti-child-sex-trafficking group Operation Underground Railroad, which was founded in Utah in 2013 and has achieved immense popularity on social media in the past year and a half, attracting an outsize share of attention during a new wave of concern about imperiled children. It is beloved by parenting groups on Facebook, lifestyle influencers on Instagram, and fitness guys on YouTube, who are impressed by its muscular approach to rescuing the innocent. (The nonprofit group is known for taking part in overseas sting operations in which it ensnares alleged child sex traffickers; it also operates a CrossFit gym in Utah.) Supporters commit to “shine OUR light”—the middle word a reference to the group’s acronym—and to “break the chain,” which refers to human bondage and to cycles of exploitation.

Oakdale, a small city near Modesto, is set among ever-dwindling cattle ranches and ever-expanding almond farms. By 9:30 a.m. on a Saturday in late summer, more than 100 booths lined the perimeter of the rodeo arena. Vendors sold crepes and jerky and quilts and princess makeovers and Cutco knives. (They paid a fee to participate, a portion of which went to OUR, as did the proceeds from raffle tickets.) Miniature horses with purple dye on their tails were said to be unicorns. A man with a guitar played “Free Fallin’ ” and then a twangier song referring to alcohol as “heartache medication,” which was notable only because it was so incongruously depressing; everyone else was enjoying a beautiful day in the Central Valley. The air was filled with the perfect scent of hot dogs, and with much less wildfire smoke than there had been the day before.

At the OUR information booth and merchandise tent, stickers and rubber Break the Chain bracelets were free, but snapback hats reading Find Gardy—a reference to a Haitian boy who was kidnapped in 2009—cost $30. Shellie Enos-Forkapa had planned the day’s event with help from three other Operation Underground Railroad volunteers, two of whom she had originally met through the local parent-teacher association. She was wearing an official Festival of Hope Benefiting Operation Underground Railroad T-shirt and earrings shaped like red X’s, a symbol often paired with the anti-trafficking hashtag #EndItMovement. “Oakdale has been so welcoming,” Enos-Forkapa told me. “They’re behind the cause.”

The women were busy dealing with festival logistics, but during a brief lull another volunteer, Ericka Gonzalez, drew me over to a corner of the tent to show me a video on her phone, which she thought might be called “Death to Pedos” but wasn’t. It was called “Open Your Eyes,” and Gonzalez pulled it up in the Telegram messaging app. “From the time we were little kids we revered the rich and famous,” the voice-over began, as images of celebrities and of battered children flashed on the screen. As I started to take notes, she pulled the phone away and wondered aloud if she had done something she shouldn’t have.

I watched the rest of the video a few minutes later, on my own phone. “We are digital soldiers, fighting the greatest war the world has never seen,” the voice-over explained. The bad guys: Barack Obama, Ellen DeGeneres, Lady Gaga, Chuck Schumer, Tom Hanks, Oprah Winfrey, Hillary Clinton. The good guys, a much smaller team: Donald Trump, Ivanka Trump, Barron Trump, Jesus, and an unidentified soldier holding a baby swaddled in an American flag. And, by implication, me, the viewer. “Our weapon is truth,” the voice-over continued as music swelled in the background. “We’ll never give up, even if we have to shake everyone awake one by one.”

The provenance of the video was unclear—it was not affiliated with Operation Underground Railroad and bore no resemblance to the official materials its volunteers had been handing out—but the term digital soldier rang a bell. It was a reference to a QAnon conspiracy theory that emerged in 2017 on an out-of-the-way message board and describes Donald Trump as a lone hero waging war against a “deep state” and a cabal of elites who are pedophiles and child murderers; these conspirators will soon be exposed—and perhaps brutally executed—during a promised “storm.” Notably, the video isn’t asking for money, and isn’t presenting an argument. It’s more like a daily devotional for people who already believe in its premise, or something like it.

Anxiety about the nation’s children, which is at a steady simmer in the best of times, boiled over in the summer of 2020, when the digital soldiers of QAnon occupied the otherwise innocuous hashtag #SaveTheChildren. Around the same time, major social-media platforms had started blocking overt QAnon accounts and hashtags. From their new beachhead, the digital soldiers were able to disseminate a cascade of false information about child trafficking on Instagram and Facebook: Children were being trafficked on the hospital ship USNS Comfort, then docked in New York City, and through tunnels underneath Central Park.

As outrageous as these allegations were, their timing may have made them sound less fantastical to some. They coincided with the release of popular documentaries about the real sex-trafficking crimes allegedly committed by Jeffrey Epstein, the disgraced financier who was arrested in July 2019 and committed suicide that August, and who was known for his wide circle of rich and famous acquaintances. (His death had set off a new slew of conspiracy theories.) In this context, the suddenly ubiquitous #SaveTheChildren posts created the illusion of an organic movement rising up to confront a massive social problem. Americans who knew little about QAnon became heavily involved, and when QAnon moved on to other concerns—a stolen election, a poisonous vaccine—these volunteers stayed devoted to the cause of opposing child sex trafficking.

Today, buying a raffle ticket to support this effort feels as natural to many people as picking up a Livestrong bracelet at a car-wash cash register did 15 years ago. Small businesses sponsor fundraisers. Happy couples add Operation Underground Railroad donation links to their online wedding registries. All over the country, community volunteers promote awareness of child sex trafficking: In Colorado, at a Kentucky Derby party. In Arkansas, at an Easter bake sale. In Texas, at a “Big A$$ Crawfish Bash.” In Idaho, at a Thanksgiving-morning “turkey run.” In Utah, at an annual winter-holiday fair.

In some ways, this is just the most recent expression of a fear that has been part of the American landscape since the early 20th century—roughly the moment, as the sociologist Viviana Zelizer has argued, when children came to be viewed as “economically useless but emotionally priceless.” As in previous moral panics, messages about the threat of child sex trafficking are spread by means of friendly chitchat, flyers in the windows of diners, and coverage on local TV news.

But the present panic is different in one important respect: It is sustained by the social web. On Facebook and Instagram, friends and neighbors share unsettling statistics and dire images in formats designed for online communities that reward displays of concern. Because today’s messaging about child sex trafficking is so decentralized and fluid, it is impervious to gatekeepers who would knock down its most outlandish claims. The phenomenon suggests the possibility of a new law of social-media physics: A panic in motion can stay in motion.

“PEDOPHILES CAN BE ANYONE,” Laura Pamatian, at the time a Palm Beach–based volunteer team leader for Operation Underground Railroad, wrote on Facebook in June. “They look just like you and me. They work with us … they sit next to us at our favorite restaurant … they are shopping with us at the grocery store.” To raise awareness, and funds, for Operation Underground Railroad, Pamatian helped organize a statewide motorcycling event. “It’s about saving children who are being raped and abused by pedophiles 10, 20, 30 times a day!” she wrote. “And I don’t say that to sensationalize the topic, I say it because it’s TRUE and it’s happening and NO ONE is talking about it!” Her volunteer chapter claimed that “upwards of 300,000” children are victims of sex trafficking in the United States every year.

All over the country, well-meaning Americans are convinced that human trafficking—and specifically child sex trafficking—is happening right in their backyard, or at any rate no farther away than the nearest mall parking lot. A 2020 survey by the political scientists Joseph Uscinski and Adam Enders found that 35 percent of Americans think the number of children who are victims of trafficking each year is about 300,000 or higher; 24 percent think it is “much higher.” Online, people read that trafficking is a problem nobody else is willing to discuss: The city they live in is a “hot spot,” their state one of the worst in the country. Despite what the mainstream media are saying, this is “the real pandemic.”

Of course, child sex trafficking does happen, and it is horrible. The crime is a serious concern of human-rights organizations and of governments all over the world. Statistically, however, it is hard to get a handle on: The data are often misleading, when they exist at all. Whatever the incidence, sex trafficking does not involve Tom Hanks or hundreds of thousands of American children.

When today’s activists talk about the problem of trafficking, knowing exactly what they’re referring to can be difficult. They cite statistics that actually offer global estimates of all forms of labor trafficking. Or they mention outdated and hard-to-parse figures about the number of children who go “missing” in the United States every year—most of whom are never in any immediate danger—and then start talking about children who are abducted by strangers and sold into sex slavery.

While stereotypical kidnappings—what you picture when you hear the word—do occur, the annual number hovers around 100. Sex trafficking also occurs in the United States. The U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline has been operated by the anti-trafficking nonprofit Polaris Project and overseen and partially funded by the Department of Health and Human Services since 2007. In 2019, it recorded direct contacts with 14,597 likely victims of sex trafficking of all ages. (The average age at which these likely victims were first trafficked—“age of entry,” as the statistic is called—was 17.) The organization itself doesn’t regard its figure for direct contacts as one that should be used with too much confidence—it is probably low, but no more solid data exist.

There is a widely circulated number, and it’s even bigger than the one Laura Pamatian and her volunteer chapter publicized: 800,000 children go missing in the U.S. every year. The figure shows up on T-shirts and handmade posters, and in the captions of Instagram posts. But the number doesn’t mean what the people sharing it think it means. It comes from a study conducted in 1999 by the Justice Department, and it’s an estimate of the number of children who were reported missing over the period of a year for any reason and for any length of time. The majority were runaways, children caught up in custody disputes, or children who were temporarily not where their guardians expected them to be. The estimate for “nonfamily abductions” reported to authorities was 12,100, which includes stereotypical kidnappings, but came with the caveat that it was extrapolated from “an extremely small sample of cases” and, as a result, “its precision and confidence interval are unreliable.” Later in the report, the authors noted that “only a fraction of 1 percent of the children who were reported missing had not been recovered” by the time they were counted for the study. The authors also clarified that a survey sent to law-enforcement agencies found that “an estimated 115 of the nonfamily abducted children were victims of stereotypical kidnapping.” The Justice Department repeated the study in 2013 and found that reports of missing children had “significantly decreased.”

Plenty of news outlets have pointed out how misleading the 800,000 figure is. Yet it has been resilient. It appeared on colorful handmade posters at hundreds of Save the Children marches that began taking place in the summer of 2020, many of which were covered credulously by local TV news. Narrating footage of a march in Peoria, Illinois, a reporter for the CBS affiliate WMBD did not mention the QAnon hashtags on some of the signs and passed along without comment information from the organizer, Brenna Fort: “Fort says her research shows that at least 800,000 children go missing every year.” The segment ended by zooming in on a plastic baby doll wearing a cloth diaper on which someone had written NOT FOR SALE in red marker.

The last moral panic centered on widespread physical dangers to America’s children began in the early 1980s. Several high-profile and disturbing stories became media spectacles, including the 1981 murder (and then beheading) of 6-year-old Adam Walsh, who was abducted from a Sears department store in Hollywood, Florida. The Adam Walsh story was made into a TV movie that aired on NBC in October 1983, the same year that the 1979 disappearance of 6-year-old Etan Patz was fictionalized in the theatrically released movie Without a Trace.

Adam’s father, John Walsh, who later spent more than two decades as the host of America’s Most Wanted, claimed that 50,000 children were abducted “for reasons of foul play” in the United States every year. He warned a Senate subcommittee in 1983: “This country is littered with mutilated, decapitated, raped, strangled children.” In response, Congress passed two laws—establishing a nationwide hotline and creating the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. The panic prompted the building of shopping-mall kiosks where parents could fingerprint or videotape their children to make them easier for police to identify. According to the sociologist David Altheide, it also led to the advertising of dental-identification implants for people who did not yet have their permanent teeth, as well as the creation of a cottage industry of missing-child insurance to cover the cost of private detectives in the event of an abduction. As a 1986 story in The Atlantic recounted, the nonprofit National Child Safety Council printed photos of missing children on 3 billion milk cartons; a person would have had to be paying close attention to notice that all the photos were of the same 106 faces. (The photos also appeared on grocery bags, Coca-Cola bottles, thruway toll tickets, and pizza boxes.) “Ordinary citizens may have encountered explicit reminders of missing children more often than for any other social problem,” the sociologist Joel Best wrote in 1987.

The fear of stranger abduction was partly a product of the cultural environment at the time. “Family values” political rhetoric drove paranoia about the drug trade, pornography, and crime. Second-wave feminism had encouraged more women to enter the workforce, though not without societal pressure to feel guilt and anxiety about leaving their children at home alone, or in the care of strangers. The divorce rate was rising, and custody battles were becoming more common, leading to the complicated legal situation of “family abduction,” or “child snatching.”

Yet there was still a backstop, a way for the panic to end. The Denver Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its 1985 story laboriously debunking the statistics that had caused such widespread alarm. The actual number of children kidnapped by strangers, according to FBI documentation, turned out to be 67 in 1983, up from 49 in 1982. A two-part PBS special explained the statistics and addressed the role that made-for-TV movies and media coverage had played in stoking the fire; a study conducted in 1987 by Altheide and the crime analyst Noah Fritz found that three-quarters of viewers who had previously considered “missing children” a serious problem changed their minds immediately after watching it. With the arrival of better information, the missing-children panic faded.

But decades later, fears have flared again. “You know how they used to have the kids on the milk cartons way back in the day?” Jaesie Hansen, a Utah-based mother of four who sells Operation Underground Railroad and #SaveOurChildren decals on Etsy, asked me in July. “That wouldn’t even be a possibility now, because there’s so many kids. There’s not enough milk cartons to put them on.”

“The government can control a vaccine and a virus, but they can’t control this,” Ashley Victoria, a sixth-grade teacher and designer of rhinestone-covered denim jackets, told me at her booth at the Oakdale festival. The powerful are failing, or the powerful don’t care, or the powerful are part of it all, she suggested. “I am a conspiracy theorist,” she went on, before referencing persistent internet rumors of Hillary Clinton’s involvement in sex crimes committed by Jeffrey Epstein. “I’m not going to sit here and say it’s all true, but it’s going to come out somehow.”

As I looked over a display of hoop earrings decorated with giant pom-poms at a neighboring booth, Victoria chatted with their maker about the supposedly suspicious deaths of the celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain, the fashion designer Kate Spade, and the DJ Avicii. “They were trying to expose Hollywood, and they all committed suicide,” she said. “Mm-hmm.”

The earring designer promised to send Victoria a copy of the 10-part documentary The Fall of the Cabal, which is full of QAnon-related theories and has been scrubbed from social-media and video-hosting platforms but still circulates in group chats and Telegram channels. The conversation then turned to a popular conspiracy theory about the online home-goods retailer Wayfair, which had spread across social media in the summer of 2020. The two of them discussed it excitedly, the way a pair of friends might riff on an underrated TV show or a deep cut from a beloved album. “Nobody talks about it anymore,” the earring designer complained. Victoria countered that she had been talking about it just the other day.

The Wayfair rumor they were referring to had taken flight in response to confusing listings on the retail site; some throw pillows were priced absurdly high due to an error, while industrial-size cabinets appeared overpriced to those with little knowledge of that market. On Twitter, some suggested that the listings were actually for the purchase of children. That notion—that a major American corporation was selling children online, more or less in plain sight—was also discussed in conspiracy forums on Reddit, where it was subsumed into the broader QAnon mythology about a ravenous sex-trafficking cabal. (“There is, of course, no truth to these claims,” a Wayfair spokesperson said at the time.)

QAnon may have catalyzed the spread of the Wayfair speculations, but the story had independent sources of energy. It was passed along by mom influencers who might otherwise post about manicures or nutritional supplements; it was shared among circles of women marketing essential oils or specialty shampoos, and on Instagram, where friends happily reposted one another’s well-designed Stories or infographics. Many of these women, when I spoke with them, emphatically denied supporting QAnon or even having a good understanding of what it was.

Jaesie Hansen, the Etsy seller, traced her interest in the child-sex-trafficking cause to the Wayfair theory, which she had come across mostly because she’d been stuck at home during the pandemic and was spending more of her day on social media. “I have no idea if that was true,” she said. “But I do know that that went viral, and that was when I started to look into it a lot more … If I hadn’t dove deeper into the whole Wayfair scandal last year, I probably wouldn’t have understood how big of a problem [child sex trafficking] actually is.” While Hansen acknowledges that the coronavirus is a serious issue, child sex trafficking around the world seems at least equally serious to her, and she doesn’t feel that it’s receiving adequate attention from the media. “I want to hear as much about that as I do about people dying of COVID,” she said.

Yet the panic and the pandemic are inextricably intertwined. Rumors of child sex trafficking shot across the internet during the months when pandemic shutdown measures were first implemented, a time when parents and children alike found themselves with more opportunities for idle digital browsing and emotion-led sharing. Referring to the dangers of kids being out of school and chattering online all day, Operation Underground Railroad’s founder and president, Tim Ballard, has regularly described this period as a “pedophile’s dream,” and claimed that predators were thinking of it as “harvest time.” The threat of trafficking became a pet cause for anti-vaccine groups that recruit by exploiting every kind of parental concern. (As a Florida state senator noted in August 2020, some in the anti-mask movement falsely claim that “wearing a mask increases the risk of kidnapping and child sex trafficking.”)

The new panic also provided an alternative to the Black Lives Matter protests happening around the country last summer, for those who may not have been sympathetic to that movement or its methods. (One Facebook graphic showed the phrase “Defund the police” altered to read “Defend the children.”) More recently, the panic has intersected with paranoia about immigration and the increase of migrants at the southern border, echoing arguments that a wall between the United States and Mexico would be a humanitarian effort to prevent child trafficking.

Though social-media platforms have made significant progress in removing QAnon from spaces where a well-intentioned person might stumble across it, disproportionate concern about child trafficking has already been absorbed and normalized—sustained by shocking rumors on social platforms (Were children being trafficked on the Walmart app? Were they suffering, hidden, on the container ship Ever Given, stuck in the Suez Canal?) and by word of mouth among circles of trust. This past August, in Magnolia, Texas, a suburb northwest of Houston, Tisha Butler and her family celebrated back-to-school season with a chili cook-off to benefit Operation Underground Railroad, hosted in the front yard of the martial-arts school they own and operate. Butler conducts women’s self-defense workshops every Saturday and invites survivors of domestic violence to take private lessons for free. “I’ve worked with survivors of trafficking,” she told me. “It’s very empowering for someone that survived something like that to learn the skills to protect yourself.” The chili-cook-off teams were mostly local business owners or the parents of students at the dojo; one was a group of moms who had started taking their kids to tae kwon do. Some of them had learned about OUR through Butler and were willing to support the cause because of their belief in her as a person who genuinely cares about helping children and women stay safe.

“We always think, Oh, it’s not me; I live in a good neighborhood; I come from a safe area, but it happens every day,” Butler told me, sitting in her office after a secret round of voting to determine the winner of the cook-off. “If you’re not aware, then you are a prime target.” Like many other volunteers, Butler brought up her own children when discussing her interest in the child-sex-trafficking cause. “Having daughters, imagining them being forced to have sex with 10 to 50 people a day—it’s sickening.”

Amid normal conversations about an understandable worry, startling pieces of misinformation can appear without warning. In July, I attended a benefit motorcycle ride in Clearwater, Florida, organized with the help of a women’s biker group called the Diva Angels. The members meet weekly at a Quaker Steak & Lube, in part to raise awareness about the charity group rides. Rebecca Haugland, a Diva Angel and an OUR supporter, talked with me straightforwardly about her long-standing concern for her son and daughter and, now, her two granddaughters; she’d raised her kids to understand that she’d support them if they spoke up about an adult who was making them uncomfortable, and she wants to help make the state of Florida a better place. “One of the biggest things that’s going on right now,” she also told me, “is the organ harvesting—children’s organs. They’ll take them and feed them and take care of them and raise them for their organs.”

The reliance of the present panic on social media suggests a largely leaderless phenomenon. But Operation Underground Railroad has won out as a favorite of the new activists, and serves as an authority, a common reference point, and a center of gravity. The group was founded by Ballard almost a decade ago, well before the crescendo of interest in child trafficking. In his early career, Ballard says, he spent a short time working for the CIA, then 11 years as an undercover operator and special agent for the Department of Homeland Security, partly as a member of the Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force. (Spokespeople for the CIA and DHS said they could not confirm Ballard’s employment record without his written permission, which he did not provide.) Ballard has frequently explained that he became frustrated with the limitations of American legal jurisdiction and decided to strike out on his own. Operation Underground Railroad would not be confused for a government operation; it quickly made its name conducting sting operations overseas in which Ballard or a colleague posed, often hammily, as an American pedophile. The team coordinated with local law enforcement, then contacted suspected traffickers, arranged a meeting, and lay in wait. When the marks arrived and accepted payment, law enforcement stormed in and arrested the suspects. The entire episode was generally captured on film, and much of the footage has been posted on YouTube or has appeared in feature-length documentaries. (In its early years, the group was known for inviting minor celebrities, including The Walking Dead star Laurie Holden, to participate in rescue operations.)

While no one doubts Ballard’s enthusiasm for the work, critics have questioned the efficacy of OUR’s “raid and rescue” approach, which was popularized in the 1990s by various anti-trafficking NGOs, notably the Christian nonprofit International Justice Mission. Trafficking experts note that, while dramatic, such operations fail to address the complex social and economic problems that create the conditions for trafficking. If the goal is to stamp out international child trafficking, they argue, the raids are of little value. As OUR’s own footage demonstrates, the group’s strategy involves asking targets to bring it the youngest children possible in exchange for large amounts of cash—in other words, potentially provoking the very behavior the group is ostensibly attempting to curb.

In the United States, OUR does not conduct “missions”—it is careful to avoid coming off as a vigilante group—but it does donate money to police departments. The funds are earmarked for child-trafficking-related resources, including dogs trained to sniff out hidden portable hard drives (because they might contain child-sex-abuse material). But as Vice’s Tim Marchman and Anna Merlan detailed in a recent investigation, police departments have not found OUR’s contributions particularly useful. Many of the donations are insubstantial, and one state law-enforcement agency told the reporters that the money wasn’t worth the trouble of being associated with OUR. A more significant challenge to OUR’s reputation: The district attorney of Davis County, Utah, opened a criminal investigation into the organization last year; according to a source close to the investigation, one focus of the probe is on potentially misleading statements made in OUR fundraising materials, including exaggerations about the group’s involvement in arrests made by law enforcement. The Utah attorney general’s office—which had received $950,000 over four years from OUR for a wellness program for personnel in its Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force—cut all ties to the group when it learned of the Davis County investigation. (An Operation Underground Railroad spokesperson declined to answer in detail a list of questions related to its record, and Ballard did not return requests for an interview. With respect to the ongoing Davis County investigation, the organization provided this response: “O.U.R. has not been asked to cooperate with any investigation regarding its business operations but will do so if asked.”)

Still, over the past year and a half, OUR has become the go-to organization to invoke when planning an awareness-raising golf tournament or bake sale or 10-mile truck pull. As John Walsh did in the 1980s, Ballard commands attention with graphic, emotional appeals; he peppers speeches with terms like child rape and pedophiles and bad guys, and apologizes for not apologizing for saying what he means. He is the author of several books, including one arguing that Abraham Lincoln was able to win the Civil War because he had read the Book of Mormon. (Ballard is himself a Mormon.) Fans regard him as an action hero: a real-life Batman, or a real-life Captain America. These are natural comparisons, because Ballard is charismatic and physically imposing—his extreme biceps, extreme blue eyes, and extreme bleach-blond hair represent a notable update of Walsh’s furrowed brow and Joe Friday cadence. “He’s just a badass,” Rhandi Allred, a Utah mother of five, told me. “When I grow up, I want to be like Tim Ballard.”

Ballard is now a celebrity with a national fandom. In his capacity as OUR’s founder, he was invited by President Trump to join a White House anti-trafficking advisory board. He has been the CEO of Glenn Beck’s Nazarene Fund, which purports to rescue Christians and other religious minorities overseas from captivity and refugee camps. He has been befriended by the Pittsburgh Steelers head coach, Mike Tomlin, who wrote the foreword for Ballard’s 2018 book, Slave Stealers. OUR’s annual fundraising has risen steadily with its founder’s profile, from $6.8 million in 2016 to $21.2 million in 2019, the last year for which tax records are available.

At the end of July, Ballard was the star of Operation Underground Railroad’s second annual Rise Up for Children event, for which volunteer teams across the country organize marches and fundraisers. He spoke during a concert held in Lehi, Utah, which I watched via a livestream available on YouTube. The comments section quickly filled with heart and prayer-hand emoji. Onstage, he announced that OUR would soon be releasing another documentary, about its rescue missions in Colombia, and then played the trailer, which was cut like an action thriller—guns, beaches, boats, a crack of thunder, the puff of a cigar. “There are people out there who would mock us and point at us, ‘Oh, you’re just trying to be famous,’ ” Ballard said after it finished, “those with other agendas that would put obstacles in our way to rescue children, which is absolutely insane to me.”

Ballard clearly relishes the role of the hero, and he cannily repays his followers for their admiration. Their participation in the cause is framed as itself heroic, even historic. At the Rise Up concert, Ballard explained to the audience that the abolitionist movement of the 19th century had been driven by people just like them. “They got loud. Then they got louder. Then they got so loud that it reached the ears of leaders like President Abraham Lincoln.” For a monthly $5 donation, OUR boosters can earn the designation “abolitionist”; missing children are pointedly described as victims of “modern-day slavery.” This, too, seems to provide relief for supporters who may take issue with the Black Lives Matter movement but still yearn to be on the right side of history.

Another key to OUR’s appeal is its capacious attitude toward truth. After the Wayfair conspiracy theory surfaced, dozens of anti-trafficking organizations signed an open letter stating that “anybody—political committee, public office holder, candidate, or media outlet—who lends any credibility to QAnon conspiracies related to human trafficking actively harms the fight against human trafficking.” Operation Underground Railroad was conspicuously not among the signatories. Rather than dispel the Wayfair rumor, Ballard flirted with it. In July 2020, he posted an Instagram video in which he spoke directly to the camera while an American flag rippled behind his right shoulder. “Children are sold that way,” he said. “For 17 years, I’ve worked as an undercover operator online. No question about it, children are sold on social-media platforms, on websites, and so forth.” The video has been viewed more than 2.7 million times.

This August, a spokesperson for Operation Underground Railroad wrote in an email: “O.U.R. does not condone conspiracy theories and is not affiliated with any conspiracy theory groups, like QAnon, in any way, shape, or form.” Yet Ballard himself seems at home in this milieu. A forthcoming Ballard biopic, Sound of Freedom, will star Jim Caviezel, the actor who played Jesus in The Passion of the Christ. In the spring, Caviezel appeared at a “health and freedom” conference alongside various right-wing figures—including L. Lin Wood, a lawyer and key architect of the 2020 election-fraud conspiracy theories, and Mike Lindell, the MyPillow founder and a major Trump donor, who famously tried to pitch the former president on a COVID-19 miracle cure made from a highly poisonous shrub. Video of Caviezel’s speech was shared by OUR supporters on YouTube and Facebook. In it, Caviezel told the audience that Ballard had planned to come with him for the interview but was unable to attend, because he was “pulling kids out of the darkest recesses of hell right now.” He then explained how adrenaline can be harvested from children’s bodies as they scream and die.

The sociologist Stanley Cohen coined the term moral panic in his 1972 book Folk Devils and Moral Panics. Cohen presented panics as intense but temporary—specifically, as “spasmodic.” (His interest in the phenomenon was piqued by an overreaction, on the part of the British media, to youth subcultures that favored motorcycle jackets and beachside fistfights.) He posited that moral panics run out of steam because people get bored; or they go out of fashion, like a cut of pants or a type of salad; or it becomes clear that the instigators are crying wolf; or whatever they’re saying is accepted as a fact that most people can live with.

Yet even fleeting moral panics can have lasting consequences. The white-slavery panic of the early 1900s led to the passage of the Mann Act—a law that criminalized transporting across state lines “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery.” It was wielded against Black men who traveled with white women, and later against sex workers who were accused of trafficking themselves. The 1980s hysteria about child sex abuse preceded the Child Protection and Obscenity Enforcement Act, which made sharing child-sex-abuse material over a computer illegal, but also broadened the list of crimes for which the government could obtain wiretaps. Today, the difficult problem of child-sex-abuse material on the internet is being offered as a rationale for law enforcement to obtain backdoor access to encrypted communication, or for Congress to obligate social-media companies to constantly surveil their users’ posts and private messages.

A panic can leave a mark even if it falls short of changing the law. Among other things, as Cohen wrote, it can change “the way the society conceives itself.” What does it mean that a deluded understanding of child trafficking is now the pet cause of the local florist and law firm and mortgage brokerage and foam-insulation contractor? What does it mean if American communities are cleaved along a neat divide, separating those who see themselves as caring about the lives of children from those who, because they reject the conspiracy theories and inflated numbers, apparently do not?

And what does it mean if a moral panic doesn’t prove to be spasmodic? Cohen floated the idea of “a permanent moral panic resting on a seamless web of social anxieties,” then swatted down his own suggestion, pointing out that permanent panic is an oxymoron. Cohen died in 2013 and never had the opportunity to consider the way the internet gives each of us the power to take on work as champions of morality and marketers of fear. His analysis of prior panics can tell us only so much about what to expect from this one.

I don’t want to panic about a panic. Not all, or anywhere close to all, of the organizers or attendees of events like the Festival of Hope are invested in the issue of child sex trafficking because of sinister rumors they’ve heard or inflated statistics they’ve repeated. Many of them are expressing casual support for an obviously correct moral position—the same way you might buy a brownie to help homeless vets or drop a canned good in a collection box to help poor families. Most of the people I met were simply happy to support “anything to do with kids” or “goodness in the world,” which they seemed to feel was in short supply. They were warm and friendly, the kind of people you’d hope to have around if you got a flat tire or had a fainting spell.

If there was a sentiment that almost everyone shared, it was that child trafficking is a disgusting problem at any scale, and that ignoring it speaks ill of us all. The undeniable truth of that statement points to another reason this panic may not soon recede. There are too many issues on which Americans can’t agree, such as how (or whether) to manage a deadly pandemic and how (or whether) to confront racism. But one type of justice isn’t complicated, and one definition of freedom is clear. If children are disappearing from all over the country, how could we possibly think about anything else?

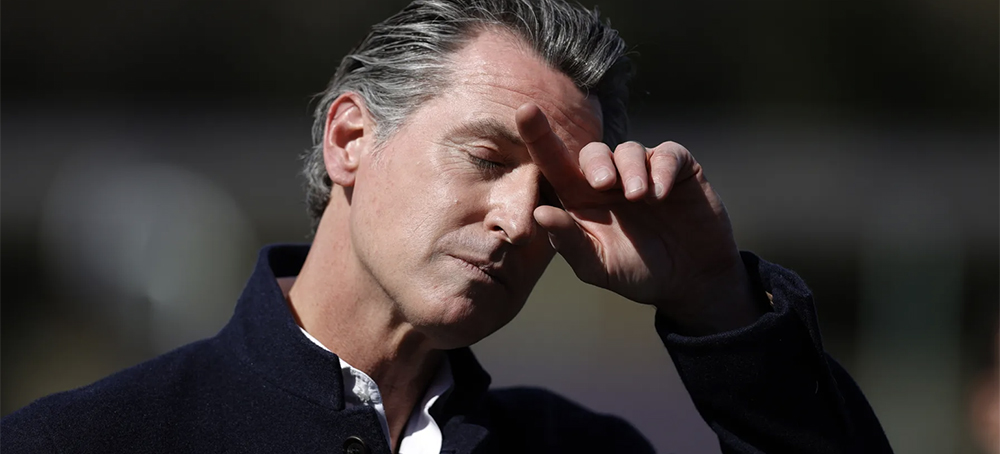

California Gov. Gavin Newsom pauses during a news conference after touring Barron Park Elementary School on March 2, 2021 in Palo Alto, California. (photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

California Gov. Gavin Newsom pauses during a news conference after touring Barron Park Elementary School on March 2, 2021 in Palo Alto, California. (photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

"I am outraged by yesterday's US Supreme Court decision allowing Texas's ban on most abortion services to remain in place, and largely endorsing Texas's scheme to insulate its law from the fundamental protections of Roe v. Wade," Newsom said in a statement.

"But if states can now shield their laws from review by the federal courts that compare assault weapons to Swiss Army knives, then California will use that authority to protect people's lives, where Texas used it to put women in harm's way," the statement continued.

The Friday ruling from the Supreme Court allowed Texas' abortion law that bars the procedure after the first six weeks of pregnancy to remain in place but said abortion providers have the right to challenge the law in federal court. However, the ruling limits which state officials can be sued by the abortion providers, which could make it difficult for them to resume providing abortions after the sixth week of pregnancy.

That is due to the law's novel enforcement mechanism, which allows private citizens -- from anywhere in the country -- to bring civil suits against anyone who assists a pregnant person seeking an abortion in violation of the law.

If lower courts are only allowed to issue orders blocking the select state officials from enforcing the ban, it is unclear if that will be enough to allow clinics to resume the procedure, as they might still face state court litigation from private citizens seeking to enforce the ban.

In light of the Supreme Court's decision, Newsom said he directed his staff to draft a bill that would allow private citizens to seek injunctive relief "against anyone who manufactures, distributes, or sells an assault weapon or ghost gun kit or parts in the State of California."

The bill would also provide for statutory damages of at least $10,000 in addition to attorney's fees, the governor's statement said.

"If the most efficient way to keep these devastating weapons off our streets is to add the threat of private lawsuits, we should do just that," Newsom said.

Rocky Howton goes through the rubble of his home in Dawsom Springs, Kentucky, on Saturday. (photo: Austin Anthony/WP)

Rocky Howton goes through the rubble of his home in Dawsom Springs, Kentucky, on Saturday. (photo: Austin Anthony/WP)

ALSO SEE: Over 80 Killed in Tornadoes in Central US;

Biden Declares Emergency in Kentucky

While the link between global warming and disasters like wildfires and flooding are more definitive, experts say, warmer temperatures could intensify cool-season thunderstorms and tornadoes in the future.

As rescuers searched Saturday amid the rubble of violent tornadoes that barreled through multiple states, killed scores of people, and leveled homes and businesses, climate scientists said people around the world needed to brace for more frequent and intense weather-driven catastrophes.

“A lot of people are waking up today and seeing this damage and saying, ‘Is this the new normal?’ ” said Victor Gensini, a meteorology professor at Northern Illinois University, adding that key questions still remain when it comes to tornadoes because so many factors come into play. “It’ll be some time before we can say for certain what kind of role climate change played in an event like yesterday.”

Still, he said the warm December air mass in much of the country and La Niña conditions created ideal conditions for a turbulent event. Thunderstorms — the raw material for tornadoes — happen when there is warm, moist air close to the ground and cooler, drier air above, creating a path for humidity to travel upward.

The tornadic thunderstorm carved a 250-mile path of destruction through northeast Arkansas, southeast Missouri, northwest Tennessee and western Kentucky, hurling debris into the sky for more than three straight hours. At times, the wreckage reached an altitude of 30,000 feet. As the twister blasted through Mayfield, Ky., it sheared entire homes off their foundations, indicating its top-tier intensity.

Whether or not scientists can pin down a link between this week’s horrific storms and climate change, Gensini said there’s no doubt that the tornadoes will go down as “one of the most devastating long-track tornadoes” in U.S. history — probably the worst since the Tri-State Tornado of 1925, which tore across three states over several hours and killed hundreds of people.

Meteorologists at the National Weather Service are surveying damage to determine whether this week’s storm was a single tornado or several. If it was a single tornado traveling on the ground without interruption for 250 miles, it will rank as the longest tornado track in U.S. history and the first to cross through four states.

As the death toll is expected to swell, it will become the deadliest December tornado outbreak on record and potentially among the most deadly in any month. Until Friday night, the deadliest December outbreak occurred on Dec. 5, 1953, which killed 38 people in Vicksburg, Miss.

Temperatures in the zone ravaged by tornadoes rose into the 70s to near 80 degrees Friday afternoon, providing the conditions for severe thunderstorms to develop that night. Dozens of record highs were set that day in the states hardest hit by the storms: In Memphis, temperatures soared to 79 degrees, breaking a 103-year-old record.

In a warming world, Gensini said: “It’s absolutely fair to say that the atmospheric environments will be more supportive for cool-season tornado events.”

But Gensini and other climate and weather experts noted that tornadoes are among the most difficult events to link definitively to global warming, partly because they are relatively small and short-lived events compared with the wildfires, heat waves and other climate disasters.

“Tornadoes are, unfortunately, one of the extreme events where we have the least confidence in our ability to attribute or understand the impact of climate change on specific events,” said Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist who directs climate and energy programs at the Breakthrough Institute, a climate research center based in Oakland, Calif. “There is not much evidence to date that the number of strong tornadoes is different today than it was over much of the past century.”

The most recent National Climate Assessment, assembled by experts at numerous federal agencies, underscored this dynamic in 2018.

“Observed and projected future increases in certain types of extreme weather, such as heavy rainfall and extreme heat, can be directly linked to a warmer world,” the authors wrote. “Other types of extreme weather, such as tornadoes, hail, and thunderstorms, are also exhibiting changes that may be related to climate change, but scientific understanding is not yet detailed enough to confidently project the direction and magnitude of future change.”

The report went on to say tornado activity in the United States has become “more variable” in recent decades, with a decrease in the number of days per year that saw tornadoes but an increase in the number of tornadoes on these days.

Harold Brooks, a senior research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Severe Storms Laboratory, said extreme tornadoes are becoming “clumpier” over time, meaning they have become more concentrated in day-long bursts. He said it wasn’t clear whether there was a connection to climate change.

And warmer Decembers will probably lead to more December thunderstorms.

“Studies suggest that the frequency and intensity of severe thunderstorms in the U.S. could increase as climate changes, particularly over the U.S. Midwest and Southern Great Plains during spring,” Hausfather said.

The additional factors required to transform a thunderstorm into a tornado — among them, a change in wind speeds at different altitudes, with more intense winds up above — are so complex that scientists have a hard time drawing a straight line between warming temperatures and more frequent tornadoes. In fact, the number of intense tornadoes in the United States “hasn’t changed back into the fifties,” Brooks said, around 500 a year.

There may be some evidence that wintertime tornadoes are becoming more frequent, Brooks said. But the tornadoes are rare enough — and hard enough to measure and classify — that it is difficult to achieve statistical confidence.

What is unequivocal, Gensini said, is that the steady warming of the planet is making a broad array of extreme weather disasters more likely and more intense.

“When you look at these things in the aggregate, it becomes pretty clear that changes are happening,” he said. “There are definitely shifts in the probability of these things happening.”

That includes longer severe weather seasons and more instability in the atmosphere during “shoulder” seasons when such disasters historically would have been less common, he said. It also could include more variability than in the past — some years could be very intense and marked by multiple catastrophes, while others could prove mild when it comes to severe weather.

That is in line with the findings of a major report the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released this summer, which found that as humans have continued to pump planet-warming gases into the atmosphere, weather-related disasters are growing more extreme and affecting every region of the world.

While the report didn’t draw a conclusion about the relationship between tornadoes and climate change, it noted that the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation in the United States was increasing.

One thing that’s different now: More people and more “things” lie in the paths of future tornadoes and other extreme weather events.

“As populations continue to grow, as cities get larger, as we continue to have more things — this is what you get,” Gensini said. “I know for certain there will be more disaster as our human footprint continues to grow.”

Nine-year-old Mahmud Qassoum remains in intensive care with a serious head injury after being hit by a US drone strike targeting a suspected Al-Qaeda-linked militant in Syria. (photo: Omar Haj Kadour/AFP)

Nine-year-old Mahmud Qassoum remains in intensive care with a serious head injury after being hit by a US drone strike targeting a suspected Al-Qaeda-linked militant in Syria. (photo: Omar Haj Kadour/AFP)

Ahmad Qassum was driving home with his family when a US drone targeting an Al-Qaeda-linked militant in Syria struck and left all six of them wounded.

Shrapnel from the attack, he said, turned his vehicle into a "pool of blood".

It wounded his wife and four children, including his nine-year-old son Mahmud who is still in intensive care for a serious head injury.

"I didn't know who to save first," Qassum said, recalling the moments immediately after the attack.

Idlib is a region dominated by the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham alliance, which is led by Syria's former Al-Qaeda affiliate.

For years, a US-led international coalition in Syria and Iraq has conducted air raids that are aimed at jihadists but often kill and maim civilians.

They include a drone strike on Friday that the Pentagon said killed a "senior leader" of the Al-Qaeda-linked Hurras al-Deen faction.

"The initial review of the strike did indicate the potential for possible civilian casualties," Pentagon spokesperson John Kirby said.

Washington has "launched a civilian casualty assessment report," he told reporters on Monday.

'Compensation'

Qassum's family was driving back to the northern town of Afrin when the strike hit a man riding the motorcycle ahead of them.

They had spent a few days visiting relatives in Idlib, their first such trip in nine months, before their family holiday took a tragic turn.

"What did we do that justifies the Americans bombing us?" Qassum said, one hand wrapped in a bandage, while the other fiddled with a rosary bead.

"We want compensation... and those who did this to us should be held to account."

The US-led coalition has disclosed at least 1,417 civilian deaths since it started operations against the Islamic State group (IS) in Syria and Iraq in 2014.

But the actual number of civilians killed is believed to be higher.

A New York Times investigation last month found the US concealed a March 2019 strike near IS's last Syria bastion of Baghuz that killed 70 people, mainly women and children.

Drawing from confidential documents, interviews with personnel directly involved and officials with top security clearance, the newspaper found the strike "was one of the largest civilian casualty incidents of the war against the Islamic State," albeit never publicly acknowledged by the US military.

The Pentagon said last month it had opened an investigation into the incident.

'Victims'

At an Idlib medical facility set up by the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), Mahmud was lying on a hospital bed, his head wrapped in a bandage.

The left side of the boy's face was dotted with small cuts.

He was unconscious for three days after the drone strike and required head surgery but is now in stable condition, his father and doctor said.

Qassum held up a phone to his son's face so he could chat with his sister who is living in Turkey, while an attendant checked his vitals.

"I didn't eat for the three days that Mahmud was unconscious," Qassum said.

"He is more precious to me than my own soul."

Doctor Ahmad al-Bayush said Mahmud was being kept in intensive care for monitoring and would be discharged soon.

Back in his wife's family home in the Idlib town of Al-Rami, Qassum sat around a large traditional furnace, fielding calls and messages from concerned relatives.

From time to time, he would check on his wife, who was lying down in an adjoining room.

Fatima Karhou, 47, was left effectively immobile, with her leg wrapped in a cast and hooked to a metal rod, after shrapnel from the strike tore through her body.

One of her cheeks had two sutured gashes, while the rest of her face was marked with smaller shrapnel cuts.

"It's true that we didn't die, but we are still victims," she told AFP, barely able to breathe between words.

"We are civilians and we can't do anything but raise our complaints to God."

George Floyd, 46, died after being arrested by police on 25 May in Minneapolis, Minnesota. (photo: Getty Images)

George Floyd, 46, died after being arrested by police on 25 May in Minneapolis, Minnesota. (photo: Getty Images)

The program was required to obtain data representing 60% of law enforcement officers, to meet a standard of quality set by the Office of Management and Budget, or else stop the effort by the end of 2022. In 2019, the data covered 44% of local, state, federal and tribal officers, and last year the total increased to 55%, according to the program's website. So far this year, the data represents 57% of all officers, the FBI said Wednesday.

"Due to insufficient participation from law enforcement agencies," the GAO wrote, "the FBI faces risks that it may not meet the participation thresholds" established by OMB, "and therefore may never publish use of force incident data."

The Justice Department said in its response to the report that "the FBI believes the agreed upon thresholds will be met to allow the data collection to continue, and is taking steps to increase participation in data collection efforts." The response by Assistant Attorney General Lee J. Lofthus also said that Justice "sent a letter to federal law enforcement agencies encouraging their participation."

On Wednesday, the FBI said in an emailed response to questions that "each day is a new snapshot in time," and that as of Oct. 18, the data represented 54% of officers. But by Wednesday, the "participation rates are at 57.15% for 2021," the FBI said.

"I'd be surprised if they didn't make 60%," said Bill Brooks, chief of the Norwood, Mass., police and a member of the International Association of Chiefs of Police board of directors. He said a key problem is that many agencies that have no force incidents are failing to input "zero reports" each month, so the agency is counted as not participating. The IACP has long supported the data collection, and low participation numbers "make us look like we're hiding something, when in reality I don't think that's the case."

As of Sept. 30, 81% of federal officers were represented in the data, even though only 43 of 114 federal agencies, or about 38%, had participated by then, according to the FBI's website. Two of the largest federal agencies, the Department of Homeland Security's Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, have been sending in data this year but the Justice Department's largest agency, the Bureau of Prisons, had not.

The GAO report also says the Justice Department has largely ignored a requirement included in the 1994 crime bill to "acquire data about the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers" and "shall publish an annual summary of the data acquired." No such summary has been published in at least the past five years, the GAO found. Justice Department officials suggested to the GAO that the national use-of-force program could provide that data, but the program does not differentiate between incidents involving reasonable force and those involving excessive force.

The impetus for the use-of-force data program was the fact that no government agency was tracking how often police killed citizens. Law enforcement officials, criminologists and other policing experts, said solid data was needed to know just how often police used force, and whether high-profile incidents such as the killing of Eric Garner in New York, Laquan McDonald in Chicago and Tamir Rice in Cleveland, all in 2014, were aberrations or the norm.

"Transparency and police data are what lead to accountability," said Nancy La Vigne, executive director of the Council on Criminal Justice's Task Force on Policing, last summer. "When you don't know what use-of-force cases are happening, it's difficult to know if you're making improvements."

The Washington Post began tracking fatal police shootings in 2015 through media reports and information from police. The Post has found roughly 1,000 fatal shootings per year, more than twice what was being reported annually to the FBI through its Uniform Crime Reporting system.

In 2016, the FBI declared its intent to start capturing its own data. Then-FBI Director James B. Comey said Americans "actually have no idea whether the number of black people or brown people or white people being shot by police" has gone up or down, or if any group is more likely to be shot by police, given the incomplete data available.

The FBI conducted a pilot program to collect data in 2017, and opened it up to all law enforcement agencies in 2019. The request for data is not minimal: the FBI wants the location and circumstances of every force incident, and detailed information on both the subject and the officers involved.

The FBI has said it will not publicly report data from any specific agency or incident, only by state. The OMB has said no data can be released if less than 40% of all officers are covered. If up to 59% of all officers are covered, the FBI "may publish limited information," the OMB said, "such as the injuries an individual received in the use of force incident, and the type of force that the law enforcement officer used." If more than 60% of officers are covered by the data, the FBI "may publish the most frequently reported responses to questions, expressed in either ratios, percentages or in a list format." At 80% of officers, "the FBI may unconditionally publish collected data," the OMB said.

Although the response rate covered 44% of officers in 2019 and 55% last year, the FBI has not released any use-of-force information so far. The names of participating agencies and the number of participants per state are available on the FBI website.

The number of agencies participating has steadily risen, the FBI's website shows, from 27% of state and local police departments in 2019 to nearly 41% of departments so far this year. The FBI estimates there are 18,514 state, local, tribal and federal police agencies in the United States, with a total of 860,000 sworn police employees.

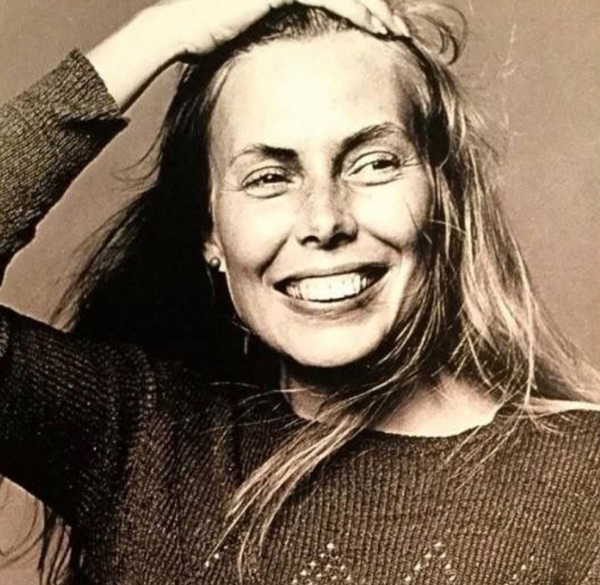

Portrait American poet, songwriter and singer Joni Mitchell, circa 1970. (photo: Martin Mills/Getty Images)

Portrait American poet, songwriter and singer Joni Mitchell, circa 1970. (photo: Martin Mills/Getty Images)

"I don't understand why Europeans and South Americans can take more sophistication. Why is it that Americans need to hear their happiness major and their tragedy minor, and as jazzy as they can handle is a seventh chord? Are they not experiencing complex emotions?"

~ Joni Mitchell

Lyrics Joni Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi.

Written by Joni Mitchell

From the 1970 album, Ladies of the Canyon.

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

With a pink hotel , a boutique

And a swinging hot spot

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you've got

Till it's gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

They took all the trees

Put 'em in a tree museum

And they charged the people

A dollar and a half just to see 'em

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you've got

Till it's gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

Hey farmer farmer

Put away that DDT now

Give me spots on my apples

But leave me the birds and the bees

Please!

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you've got

Till it's gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

Late last night

I heard the screen door slam

And a big yellow taxi

Took away my old man

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you've got

Till it's gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

Arnold Norman Yellowman says he is deeply concerned by the pollution surrounding his family in Aamjiwnaang First Nation. (photo: Jillian Kestler-D'Amours/Al Jazeera)

Arnold Norman Yellowman says he is deeply concerned by the pollution surrounding his family in Aamjiwnaang First Nation. (photo: Jillian Kestler-D'Amours/Al Jazeera)

The fight to end environmental racism in Canada.

Yellowman, 38, has developed a deep - and profoundly undesired - connection with the pollution surrounding his family in Aamjiwnaang First Nation. When trucks rumble along the road at night, the vibrations resonate throughout the home he shares with his partner and their three young children. When he steps out onto his sunny back porch, he can sense the chemicals in the wind.

“That’s the north wind. It comes from Esso or Imperial Oil,” Yellowman tells Al Jazeera, tracing his finger across the sky. “If the wind blows from this direction, it’s Suncor - used to be Dow. And if the wind blows over this way, it’s Shell, ethanol, Dupont. If it blows from the south, it’s Nova Chemicals.”

Yellowman, who has lived in Aamjiwnaang for close to three decades, worries acutely about the health effects of growing up in one of Canada’s most heavily industrialised areas.

Chemical Valley is centred around Sarnia, Ontario, a city of about 74,000 people at the southern tip of Lake Huron, just across the border from the US state of Michigan. Aamjiwnaang, home to about 900 people living on the reserve, is a short drive from the city centre past rows of towering oil storage tanks, gas flares spitting flames into the sky, and other fenced-in infrastructure. Speakers are affixed atop tall wooden poles throughout the community, ready to blare warning sirens in an emergency.

In 2016, more than three dozen petroleum refineries, petrochemical plants and energy facilities operated within a 25km (15.5-mile) radius of the First Nation, according to a recent report by environmental group Ecojustice. That figure included 23 facilities that emitted more than 50 tonnes of air pollutant per year. In total, Sarnia-area facilities emitted more than 45,300 tonnes of air pollutant that year - about 10 percent of total emissions across the province of Ontario. Chemical Valley accounts for about 40 percent of Canada’s chemical industry.

“Aamjiwnaang is quite infamous worldwide in that it is surrounded completely by industries and pollution,” says Niladri Basu, a professor at McGill University in Montreal and Canada Research Chair in Environmental Health Sciences. “It’s no surprise that the community feels like it’s being contaminated, because all they smell and hear and see is the pollution.”

Yellowman recalls stories of miscarriages and stillbirths in his community; of dialysis and chemotherapy; of overdose and suicide. “I think about my children often ... We have to worry about so many different factors,” he says, “about even allowing them to go outside in their yard.” As a child himself in the 1990s, he recalled playing in a “foggy mist” that had drifted across the highway.

“I didn’t know it was the coolant back then, but it just comes across the highway and you just go and play - and there’s a lot of stories like that,” he adds.

Chemical Valley is among Canada’s most notorious examples of environmental racism, a concept that refers to the disproportionate siting of hazardous projects and polluting industries among populations of colour and Indigenous communities.

From mercury poisoning in Grassy Narrows First Nation, to the building of major oil and gas pipelines on unceded, Indigenous lands, to the placement of landfills near historic African-Canadian communities on the east coast, environmental racism has manifested across Canada for decades - even before the term itself was coined.

US civil rights leader Benjamin Chavis is credited with first using the phrase in 1982, and Robert Bullard, distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, was instrumental in later defining it. Bullard has pointed to the southern United States, in particular, as a “sacrifice zone” where “environmental decision making and local land-use planning operate at the intersection of science, economics, politics and special interests in a way that places communities of colour at risk”.

Ingrid Waldron, Canada’s preeminent expert on the topic and author of There’s Something In The Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous & Black Communities, says rural and isolated areas are most affected.

“These are [people] who, through colonialism and other processes, have been situated in those types of communities, and it is a combination of geography ... as well as race and socioeconomic status, that then results in the spatial patterning of industries disproportionately in these communities,” Waldron tells Al Jazeera.

After decades of inaction on the issue, Canada recently started examining its history of environmental racism, as affected residents, environmental groups and legislators have demanded concrete action to address lasting harm. The governing Liberals - in their party platform released ahead of snap September elections that they won, albeit with minority status - pledged to “identify and prioritize the clean-up of contaminated sites in areas where Indigenous, racialized, and low-income Canadians live”, and to probe the link “between race, socio-economic status, and exposure to environmental risk, and develop a strategy to address environmental justice”.

This promise came just months after Bill C-230, a private member’s bill calling for the development of a national strategy to combat environmental racism, passed its second of three readings in the House of Commons. But Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s decision to call the federal election halted Bill C-230 in its tracks, and the sponsoring MP, Lenore Zann, was ultimately defeated by her Conservative opponent in the Nova Scotia district of Cumberland-Colchester.

If the Liberals follow through on their election promise by tabling legislation on environmental justice, however, progress on the issue could be much swifter.

In an email, a spokesman for Canada’s federal minister of environment and climate change said Ottawa was committed to advancing legislation “to assist in addressing environmental justice issues” as part of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. Gabriel Brunet told Al Jazeera that a proposed law - separate from Bill C-230 - would include “biomonitoring surveys”, which could involve probing the effects of pollution on vulnerable populations. The legislation would also facilitate “the making of geographically targeted regulations that could, for example, be used to help address pollution ‘hot spots’ that may disproportionately affect marginalized communities”, Brunet said.

“We plan on tabling this legislation as soon as possible,” he said, without providing an exact date.

The genesis of Canada’s drive to combat environmental racism lies on the country’s eastern seaboard, in the Atlantic province of Nova Scotia, home to some of the earliest Black communities in the country. By the mid-18th Century, according to government figures, there were about 400 enslaved and 17 free Black people living in Halifax, which is today the largest city in the province.

The Black population continued to expand throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries as large groups of settlers, including people who had been enslaved in the US, began arriving in Nova Scotia. Yet, while many were hoping for a fresh start, racist policies pushed them to the margins of society.

The story of Africville is a case in point: Located in the Halifax area, it developed into a thriving Black community during the 19th century and well into the 20th, even as municipal authorities failed to provide basic amenities such as sewage systems, clean water, garbage disposal and emergency services - all while continuing to collect taxes from residents. At the same time, the city surrounded Africville with facilities unwanted in other communities, including an infectious diseases hospital, a prison, a dump and a slaughterhouse.

Today, the only remaining physical evidence of the community is the Africville Museum, built inside a reconstructed Seaview United Baptist Church - once the beating heart of Africville. Outside the museum, a trailer is painted in bold colours with the face of long-time activist Eddie Carvery and the words “All Power to the People”. Inside, exhibits tell the story of a community abandoned by the city that was meant to serve it.

Former resident Beatrice Wilkins, who is on the board of the Africville Heritage Trust, which manages the museum, remembers how children were always told to “be careful” when going out in the neighbourhood.

“There were certain places you couldn’t go, like we were warned to stay off the dump. We were warned not to go up around the Rockhead Prison, and the infectious diseases hospital ... because you never know what you could pick up,” she tells Al Jazeera. “Those things were put right into our physical community, and there was nothing we could do about it, because we were nobody - and the city just did whatever they wanted.”

In 1958, Africville was officially designated a “slum”, and in the years that followed, Halifax city council pushed residents out, using “the threat of expropriation to negotiate the purchase of their land”, according to the heritage trust.

Although residents were supposed to be consulted about the relocation plan, more than 80 percent were reportedly never contacted by the committee tasked with carrying it out. Between 1964 and 1970, families were removed from their homes and many were placed in public housing projects, the heritage trust noted in its online retelling of the story of Africville. “Homes were demolished and the church bulldozed in the middle of the night. The means of displacement served as a metaphor for how the community of Africville was regarded: the city moved some of the residents’ belongings in municipal dump trucks.”

Amanda Carvery-Taylor, whose family has a long history in the area and who recently authored a compilation titled A Love Letter to Africville, says this was a devastating blow, displacing and isolating members of the once tight-knit community. While Africville had been poor, under-serviced and encircled by polluting industries, none of these things defined it, she says.

“There’s a feeling that these things were Africville, but they weren’t,” Carvery-Taylor tells Al Jazeera. “They were surrounding Africville, and definitely undesirable, but the community was very happy to be together. That was the main thing, was just them being together, having a safe place that they could live and exist ... There were definitely fine-china Sunday dinners with your gloves on and your hats, and church.

“Everything was stunning in Africville,” she adds. “It was absolutely beautiful, so it was just like they were surrounded by bad things. But when they were razed in the ‘60s, it basically devastated the community. It destroyed, or attempted to destroy us.”

In the decades that followed, Africville residents pushed the city for restitution, culminating in 2010 with a public apology from the mayor of Halifax and $3m in funding to rebuild the Seaview church and provide other support for the Black community. Debate persists as to whether any of this was enough, with some former Africville residents and their descendants calling for reparations to this day.

Current Halifax Mayor Mike Savage says the city is continuing to explore various ways of supporting former Africville residents, but “whether that means traditional reparations”, he says he does not know. In April, the city council approved a motion to embark on a “visioning process” for Africville, part of which would examine what has happened since the 2010 apology and compensation package, and what more needs to be done. Savage told Al Jazeera this would be a long-term endeavour.

“If we are going to be serious about first of all understanding history, and secondly making the future better than the past, as a city we have to do things differently,” he says. “We can’t just assume the way we’ve always done things, the way we’ve engaged, has been sufficient.”

Alongside Africville, other problematic sites in Nova Scotia include the Boat Harbour treatment facility, which saw millions of litres of effluent piped daily into a Mikmaq harbour until it was shut down last year; the African Nova Scotian community of Lincolnville, where a landfill site has raised serious concerns about water quality; and a 1940s-era dump for residential, industrial and medical waste in the Black community of southern Shelburne.

Waldron, whose book on environmental racism was the basis of a 2019 documentary co-directed and co-produced by actor Elliot Page, has spent years documenting the phenomenon in the province. She serves as executive director of the Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities and Community Health (ENRICH) project, which has mapped the proximity of dozens of waste disposal sites and other toxic industries to First Nations and African Nova Scotian communities.

“These are people that are not seen - as people of colour and Indigenous people - we are not seen as worthy of protection in the same way that white people are,” Waldron says.

Louise Delisle, an activist who lives around the corner from the former Shelburne dump, which ceased regular operations in the 1990s and was permanently closed in 2016, recalls being forced as a child to shelter indoors when the garbage was being incinerated. “When that dump was afire, we had to be inside because of the smoke, and the smell, and the ash ... You can imagine, with tonnes and tonnes of garbage burning, what the smell would be like, and the ash from that burning, the wind blowing, the seagulls - thousands of seagulls. Growing up here that way was not easy.”

Delisle remains deeply concerned about the long-term health effects of living so close to the dump. Each time one of her neighbours dies of cancer, she records it in her own personal database, which now has dozens of entries. Delisle lost her brother to stomach cancer, her father to prostate cancer, and her mother to breast cancer and a blood disorder. Several other relatives have been diagnosed with, or died from, various cancers. She believes this is the legacy of Shelburne’s toxic environment.

“It really tears you apart inside, because you never stop grieving. You’re in a constant state of grief all the time,” Delisle tells Al Jazeera. “It’s always somebody. We’re losing at least two people a month, and sometimes more than that, to cancer. That’s to this day.”

Past studies in other regions have cited the potential adverse effects of landfills on the environment and human health, with risks ranging from respiratory illnesses to cancer. But it remains difficult to establish a definitive, proven connection. Today, Waldron is part of a team embarking on a new study to determine whether the Shelburne dump - as opposed to other factors, such as socioeconomics and lifestyle - might be responsible for the spate of cancer cases in that community.

“[Across the province], there’s a clear association to me, a strong association between the presence of these industries near these communities and serious health issues,” Waldron says.

According to Basu, the McGill University professor, making direct links between proximity to specific chemicals and polluting industries, and negative health effects, is one of the biggest challenges when investigating environmental racism.

“In a case like Aaamjiwnaang, you have hundreds if not thousands of chemical stressors, and you’re not exposed individually but in complex mixtures. So then how do you actually backtrack that chemical and figure out which facility it came from?” he tells Al Jazeera.

Basu was among a group of researchers that measured chemical exposure in Aamjiwnaang about a decade ago at the request of the community. Their study, which involved collecting hair, urine and blood from residents but was limited in scope, found that mothers and children were exposed to several pollutants, including mercury, which the World Health Organization says is “highly toxic to human health”.

“We looked for a number of different chemicals and not surprisingly these were found in all individuals by and large,” says Basu, who described the findings as a “good first start” but acknowledged that more research is needed.

“The big caveat here is that all the chemicals we looked at are not safe at any level, so just finding them in peoples’ bodies should raise some questions about what people are being exposed to and sort of the long-term consequences of chronic exposures to these types of chemicals,” he says.

Another more recent study Basu was involved in, released in 2019, found that Indigenous people globally were among the populations at highest risk of being affected by pollution, with oil and gas exploration, mineral extraction, toxic waste dumping and industrial development among the top sources of exposure.

“A lot of it may go back to just historical issues and ways in which lands and treaties were developed, whereby polluting industries were placed beside the Indigenous communities without their consent or involvement,” he explains.

Warnings about the effects of pollution in Aamjiwnaang have escalated in recent years, with experts calling on Canadian and Ontarian authorities to do more to investigate.

In 2017, the province’s environmental commissioner said Aamjiwnaang residents have been exposed to toxic chemicals such as benzene and sulphur dioxide, and were breathing in “some of the worst air pollution” in the country. “There is strong evidence that the pollution is causing adverse health effects, which neither the federal nor provincial government have properly investigated,” Dianne Saxe wrote in her annual protection report.