Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

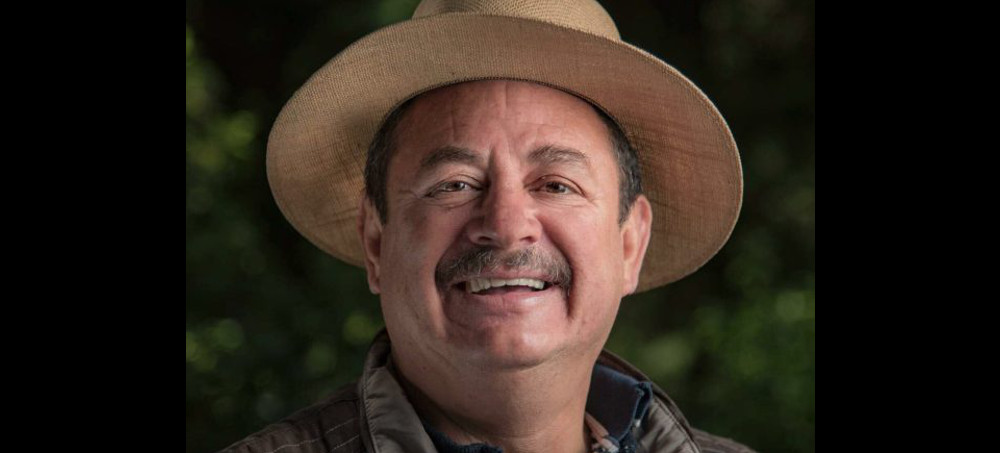

A magazine editor in San Cristóbal de las Casas, a mecca for tourists and expats, falls victim to a relentless wave of violence against the press.

López Arévalo—widely known just as Fredy—grew up on a coffee farm in the town of Yajalón, forty miles from San Cristóbal on the eastern slopes of the highlands. He came from an accomplished family. One of his brothers, Jorge, is a professor of economics at the Autonomous University of Chiapas. Another brother, Julio, was a longtime Chiapas correspondent for the Mexico City-based magazine Proceso. Fredy had worked for several Mexico City-based newspapers, covering the wars in Central America, the conflict in Colombia, and the Zapatistas, an armed Indigenous group that, on New Year’s Day, 1994, surprised the Mexican government and the world by occupying several towns, notably San Cristóbal. He eventually returned to his native Chiapas, where he started a news agency, was a broadcaster on XERA-Radio Uno, and published Jovel, a San Cristóbal monthly.

On the night Fredy arrived home, he and his wife, Gabriela, were returning from a birthday lunch that they had hosted at a seafood restaurant—replete with coconut punch—for Fredy’s eighty-three-year-old mother, Doña Blanca Luz Arévalo Abadía, in the lowland city of Tuxtla Gutiérrez. Photos posted on Fredy’s Facebook page show him beaming. A friend of his described him to me as “muy campechano,” a hearty guy with a genial disposition. As Fredy, who loved to cook, unloaded a case of avocados from the trunk of his car that evening, an assassin walked up behind him, shot him at the base of his skull, and, according to press accounts, sped off on a waiting motorbike.

On the same day that Fredy was murdered, another Mexican journalist, Alfredo Cardoso, was pulled from his home in Acapulco and shot five times. Cardoso’s death in a hospital, several days later, raised the number of Mexican media workers killed in 2021 to at least nine and affirmed the country’s standing as one of the most dangerous places in the world to practice journalism. Jan-Albert Hootsen, a Mexico-based representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists, told me that Mexico currently has the world’s highest number of unsolved murders of journalists—twenty-seven in the past decade—and government officials are often involved. This had the effect, he said, of both creating a culture of impunity and “enabling attacks on reporters.”

I lived in San Cristóbal de las Casas thirty years ago, a time when an event like Fredy’s assassination was inconceivable. A longtime San Cristóbal resident told me, “There was poverty, inequality, but it never felt as if anyone’s life was at risk.” The changes in the small city that made Fredy’s brazen murder possible shed light on what is happening not just in Chiapas but across Mexico.

Months before his murder, Fredy closed the offices and print version of his magazine, Jovel, and began posting prolifically on Facebook. His posts reflected the diversity of his interests: the search for “freedom, dignity and peace” that fuelled immigrant caravans passing through the region, bound for the United States; newly discovered archaeological sites, demonstrating possible connections between the Maya and the Olmecs; mass layoffs at San Cristóbal’s city hall; and his favorite recipes. Three days before he was killed, he posted a recipe for sangría with a quote from the Mexican poet and Chiapas native Jaime Sabines: “If you survive, if you persist, sing, dream, intoxicate yourself.”

Two days before his murder, he posted a two-part message. The first concerned an ongoing conflict between narco-traffickers and the Indigenous population around the municipality of Pantelhó, a couple of hours north of San Cristóbal. Zapatista influence in San Cristóbal itself has waned since the nineteen-nineties, but it persists in rural areas such as Pantelhó, fuelling opposition to traffickers and the government. Through the years, though, drug syndicates have taken control of the Pantelhó municipal government and large swathes of Indigenous land, forcing out several thousand Maya farmers.

In the first part of Fredy’s post, he decried the assassination of Simón Pedro Pérez López, a well-known catechist and member of the Abejas—the “Bees”—a Catholic activist and pacifist resistance group sympathetic to the Zapatistas. A motorcycle-mounted hit man had shot him outside a market near Pantelhó. He was the twelfth person, according to Fredy’s post, murdered in the previous three months. After the killings, Indigenous residents had formed an armed civil-defense group—El Machete—burned the houses of a dozen or more suspected narco affiliates, and occupied Pantelhó’s municipal offices. In the second part of Fredy’s post, he described the murder, which happened one evening in a busy section of San Cristóbal itself, of Gregorio Pérez Gómez, a Chiapas-based prosecutor investigating the violence in Pantelhó. Two men on a motorcycle had ambushed Pérez in his car outside his office and shot him dead.

When I asked a researcher at a Mexican university if there was a connection among the assassinations of Fredy, the catechist, and the prosecutor, he pointed out a fourth killing in San Cristóbal. In July, an Italian N.G.O. worker, who was said to have spoken out against the increasing violence, was shot as he bought food at a corner store while walking home from a bar, where he’d watched the Italian soccer team win the European championships. Asked if he thought there was a link between that murder and the others, the researcher, who asked not to be named, said nothing.

San Cristóbal is a profoundly conservative town with a legacy of deep racism toward its Indigenous population. Until the nineteen-fifties, the Maya were allowed neither to walk on city sidewalks nor to enter the city alone at night. No paved roads connected the city with the rest of Mexico. Since then, San Cristóbal has expanded “almost beyond reason,” the long-term resident told me. The city is now a tourist and expatriate destination. Several downtown streets are lined with bars and restaurants and shut off to vehicular traffic. Parts of San Cristóbal look like an upscale mall in Los Angeles. A large house in the town center can sell for half a million dollars.

The Maya, though, remain marginalized. The highlands surrounding San Cristóbal are still filled with milpas, the small, traditional corn, bean, and squash fields that are the defining attribute of traditional Maya life. But a hundred thousand Maya now live around the city in colonias, crowded neighborhoods where extreme poverty is the norm and the demographic skews young and jobless. Eighty per cent of colonia residents are Chamulas, the largest Maya group in the San Cristóbal region. Tsotsil—the language of the Chamulas—is the lingua franca.

As the population has grown and the corn-and-bean fields in the Maya highlands have become inadequate to sustain it, Indigenous men have had to supplement their incomes with migratory work, according to “Trapped Between the Lines,” a 2014 paper, by Diane and Jan Rus, in Latin American Perspectives. By the mid-two-thousands, Chiapas had become Mexico’s second-largest exporter of undocumented labor to the United States. After the 2008 recession and immigration crackdowns by the Obama and Trump Administrations, large numbers of Maya wound up on the margins of cities such as San Cristóbal. The Maya living in San Cristóbal’s colonias scramble for whatever temporary work they can find. “They’re fodder,” an anthropologist told me, “landless, jobless, marginalized, and hopeless.” Many have been hired by organized crime groups, often run by non-Maya. “The criminal business community is flourishing in Mexico.”

Two to three years ago, young Maya residents of the colonias began to form motorbike gangs known as motonetos. The gangs started as self-defense organizations and included both Maya and non-Maya. As they became more prominent, members began to engage in theft, extortion, and other crimes. Eventually, they developed a reputation for what the anthropologist referred to as “shock troops for local narcotraficantes.” In September, a hundred of the motonetos—many carrying long rifles—flooded the city center, firing fusillades of bullets from automatic weapons in the air. One of the bullets tore through the corrugated roof of an Indigenous family’s home on the edge of town, killing a seven-year-old child.

Nobody I spoke with in San Cristóbal seemed to know what had motivated the mass turnout of motonetos, but it’s difficult to imagine that their show of force didn’t have something to do with narcotics. A former journalist—who’d once worked with Fredy—told me that cocaine was now plentiful in the city. You could have a gram—a grapa—brought to you by a narcomenudista, a motorbike delivery man, for the peso equivalent of ten to twenty dollars. When I asked her about the narcotics trade more generally, she, like others I spoke with, asked not to be named. She said that, as a journalist, she had come to prefer life-style stories. “If you report on narcotics,” she told me, “you run a big risk.”

On October 20th, eight days before he was assassinated, Fredy put up a longer-than-usual post on Facebook. In his message—something of a rant—he claimed that sixty-five per cent of the cocaine that comes to the U.S. enters Mexico through Chiapas’s border with Guatemala, which is, he noted, the widest and most porous border that Mexico has with Central America. He claimed that journalists in Chiapas press were forbidden from even using the word narcopolítico, a politician who works for the drug cartels. Fredy was also critical of the municipal president of San Cristóbal, Mariano Díaz Ochoa. In earlier Facebook posts associated with Jovel, Fredy’s magazine, he’d linked members of the Díaz Ochoa administration to several of the leaders of the motonetos. (Díaz Ochoa declined a request for comment.)

Fredy’s posts were notable not just for their imprudence but also for their nonspecificity. Who were, for example, the municipal authorities who “felt themselves to be giants but were in fact ‘dwarves?’ ” Which narco-traffickers were battling one other municipio by municipio? Much of the vagueness of Fredy’s posts was, no doubt, driven by an attempt to survive. But it also likely reflected his underlying frustration as a journalist—indeed, of any citizen—watching the triumph of criminality without being able to say anything about it.

When I asked about the arrival of narcotics in Chiapas, the university researcher told me that he was intensely interested in how it was unfolding but, out of caution, had been forced to feign indifference when discussing the subject with sources. He told me that, in Chiapas, there was now a self-described Chamula cartel run by a Chamula capo who dressed all in black and wore a pistol at his waist. The cartel transacted its business in Tsotsil—effectively making it the “code-talker” cartel—and had an entente with a much larger and much more violent cartel based in western Mexico and spreading into Chiapas, the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación. “There’s a major smuggling corridor across the highlands,” he told me, “one that connects Guatemala with San Cristóbal, Chenalhó, Pantelhó, and the road north to the Gulf.”

The Chamulas, the researcher said, traffic not only drugs but also migrants. They pick up undocumented migrants north of the Guatemala border, load them into tractor trailers near San Cristóbal, and drive them to cities in central Mexico or on the Gulf coast. The trailers are equipped with small respirators so that the migrants can breathe, buckets so that they can relieve themselves, and mats on which they can sit. The trailers hold a hundred or more migrants. On December 9th, one of the Chamula-cartel trailer trucks—which, earlier that day, had loaded immigrants at a safe house in San Cristóbal—crashed near the lowland city of Chiapa de Corzo. Over fifty migrants—mostly from Guatemala—died, their bodies strewn all over the road. A hundred more were injured.

Guatemalans or Hondurans trying to reach the U.S. pay, on average, seventy-five hundred dollars to the human-trafficking groups, an amount they can borrow from the traffickers at exorbitant interest rates. They put up their land and houses as collateral and become de facto indentured servants. The researcher described the smuggling of migrants as “part of a chain of integrated transnational corporations.”

In the past thirty years, fewer than ten per cent of Mexico’s murder cases involving members of the press in Mexico have resulted in prosecutions, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Claiming that Fredy’s murder was a serious crime because it concerned the right to freedom of expression, Mexico’s Attorney General moved to have the federal government take over the investigation from local authorities. A member of Fredy’s family told me that, according to investigators, a neighbor’s security system showed that someone had staked out Fredy’s house for three weeks before the actual assassination and, during that time, had stayed at a hotel just around the corner. “They were trying to learn Fredy’s habits,” the family member told me. The suspected assassin was a veteran criminal from Terán, a town near Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the city where Fredy and his wife had hosted lunch for his mother that day. The family member told me that, in his opinion, the hit on Fredy was a professional job, originating from “a high level” of narco-politics. “We suppose it was because of something he wrote,” the family member told me.

On December 30th, Chiapas state authorities discovered a car parked by the side of the road in Frontera Comalapa, a town beset by cartel violence, near the border of Guatemala. In the trunk were two bodies that had been shot multiple times and showed possible signs of torture. One was wearing a cap bearing the initials C.J.N.G.—Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación. The authorities did not release their full names and identified them by aliases, El Moco and El Norteño. Chiapas state authorities claimed that they were the men who’d planned Fredy’s killing and carried it out.

The deaths of the alleged assassins raised more questions than they resolved—particularly for Fredy’s family. A family spokesperson told me that he had no confidence that the two cadavers were Fredy’s killers. He wondered why Fredy’s family and federal prosecutors had not found out about the murders until they appeared in the press, five days after they’d occurred. And why was one of the murdered men older, heavier, and lighter-skinned than the suspect whom the Chiapas state prosecutors said they were seeking? The family spokesperson said that authorities seemed anxious to shelve the case. He urged them not to do so, because, he said, there was still “a criminal network to investigate.”

It’s ultimately not clear whom Fredy offended or how. Many people in San Cristóbal told me that there is a deep feeling of foreboding in the city. The family member I spoke with described it as a sense of “descomposición.” Drug violence at the levels at which it’s appearing in a community considered a pueblo mágico is something new. In the absence of functioning police forces, courts, and media, fear and suspicion run rampant. The best epithet to Fredy may, in the end, be one of his final Facebook posts: a description of the meal he enjoyed the evening before he was shot—“fried huitlacoche dobladitas with epazote and manchego cheese, garnished with habanero paste. Ufff. Buenas noches!”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

n the middle of March, I texted my friend Tahir Luddin, an Afghan journalist who lives in the Washington area, after I saw a video he had posted on Facebook of his teen-age son running on a treadmill. My text was banal, a quick check-in to see how he and his loved ones were faring amid the isolation of the past year. “How is your family? How are you?” I wrote. “See the pictures of your children on FB. Your son is very tall!!!” Tahir did not reply. At the time, I didn’t worry and assumed that he would get back to me. Our communications were sporadic, but our bond was unusual.

n the middle of March, I texted my friend Tahir Luddin, an Afghan journalist who lives in the Washington area, after I saw a video he had posted on Facebook of his teen-age son running on a treadmill. My text was banal, a quick check-in to see how he and his loved ones were faring amid the isolation of the past year. “How is your family? How are you?” I wrote. “See the pictures of your children on FB. Your son is very tall!!!” Tahir did not reply. At the time, I didn’t worry and assumed that he would get back to me. Our communications were sporadic, but our bond was unusual.