Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The article below is satire. Andy Borowitz is an American comedian and New York Times-bestselling author who satirizes the news for his column, "The Borowitz Report."

Trump’s permanent ban went into effect just moments into the beta test of the new social-media platform, Truth Social.

After Trump posted his first status update, the platform determined that he had violated its terms of service and expelled him forever.

Harland Dorrinson, a spokesman for Truth Social, confirmed that the platform had banned Trump, adding, “It’s unfortunate, but our hands are tied.”

Reportedly, Trump has prepared a blistering statement about his Truth Social ban but has been unable to find anywhere to post it.

Mark Meadows, who was chief of staff to President Donald J. Trump, at the White House in 2020. (photo: Erin Scott/NYT)

Mark Meadows, who was chief of staff to President Donald J. Trump, at the White House in 2020. (photo: Erin Scott/NYT)

"We agreed to provide thousands of pages of responsive documents and Mr. Meadows was willing to appear voluntarily, not under compulsion of the Select Committee's subpoena to him, for a deposition to answer questions about non-privileged matters. Now actions by the Select Committee have made such an appearance untenable," the letter from George J. Terwilliger II stated.

"In short, we now have every indication from the information supplied to us last Friday - upon which Mr. Meadows could expect to be questioned -- that the Select Committee has no intention of respecting boundaries concerning Executive Privilege," Terwilliger added.

CNN first reported last week that Meadows had begun cooperating with the committee, handing over thousands of documents and agreeing to appear for an interview this week.

Meadows' about-face is due in part to learning over the weekend that the committee had "issued wide ranging subpoenas for information from a third party communications provider," the letter notes.

"As a result of careful and deliberate consideration of these factors, we now must decline the opportunity to appear voluntarily for a deposition," Terwilliger writes.

Terwilliger writes that Meadows would answer written questions "so that there might be both an orderly process and a clear record of questions and related assertions of privilege where appropriate."

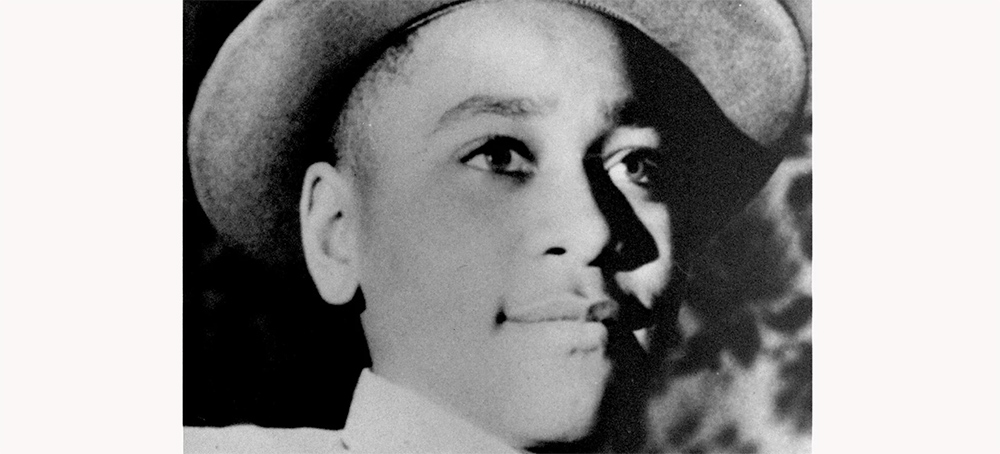

Emmett Louis Till, a 14-year-old Black boy, was kidnapped, tortured and murdered in 1955 after he allegedly whistled at a white woman in Mississippi. (photo: AP)

Emmett Louis Till, a 14-year-old Black boy, was kidnapped, tortured and murdered in 1955 after he allegedly whistled at a white woman in Mississippi. (photo: AP)

ALSO SEE: The Justice Department

Closes Its Investigation Into the Lynching of Emmett Till

The DOJ closed its investigation after finding “insufficient evidence” that a white woman had recanted her claims that led to the Black 14-year-old’s lynching.

“I’m not surprised but my heart is broken,” Till’s cousin Thelma Wright Edwards said at a press conference Monday in Chicago. “I had hope that we could get an apology, but that didn’t happen. Nothing was settled. The case is closed and we have to go on from here.”

On Monday, the Justice Department met with members of Till’s family to tell them that the agency had closed the investigation it reopened in 2018 into the teen’s murder.

In 1955, white men lynched 14-year-old Till after Carolyn Bryant Donham claimed the boy had harassed her in a Mississippi grocery store. Bryant Donham’s husband and his half-brother kidnapped, brutally beat and tortured the teen, shot him dead and threw his body into the Tallahatchie River. An all-white jury acquitted the men. Till’s killing and the photos of his brutalized body from his funeral fueled the civil rights movement.

The DOJ reopened the investigation into Till’s death after a 2017 book quoted Bryant Donham, who is still living, admitting that she had lied about what happened.

The DOJ and FBI examined whether Bryant Donham had recanted, as the book claimed, which could have led to new charges, including against her.

But after years of inquiry, officials concluded that “there is insufficient evidence” that Bryant Donham had, in fact, recanted her story, according to a press release from the DOJ.

“When asked about the alleged recantation, [Bryant Donham] denied to the FBI that she ever recanted her testimony,” the release said, adding that there is “insufficient evidence to prove that she ever told [the book’s author] that any part of her testimony was untrue.”

Officials noted that there also “remains considerable doubt as to the credibility of her version of events,” adding that Bryant Donham’s story is “contradicted by others who were with Till at the time.”

“This family has waited 66 years to learn who would answer for Emmett. And now we know: nobody. And that’s a tragedy on top of a tragedy,” said Christopher Benson, an associate professor of journalism at Northwestern University who met with the DOJ, FBI and other officials with Till’s family on Monday.

Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., Till’s cousin and best friend, who was in the house when the men kidnapped Till in the middle of the night, said that “today is a day we’ll never forget,” speaking of officials closing the investigation.

“For 66 years we have suffered pain, loss,” Parker said, noting he was only 16 years old when his cousin was kidnapped and killed.

“You did not die in vain,” he said of Till. “We can’t bring him back, but we can carry on and let America know we need to know the truth.”

Till’s cousin Ollie Gordon echoed other family members that the government’s findings “came as no surprise.”

“I did not expect they would find new evidence… or be able to validate Carolyn Bryant recanting her story,” Gordon said, urging people to “look to the future.” “Where do we go from here? Even though we don’t feel we got justice, we still must move forward. Let’s figure out how we can continue to make change.”

Demonstrators outside the Supreme Court as it hears a case on possible partisan gerrymandering by state legislatures on October 3, 2017. (photo: Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call)

Demonstrators outside the Supreme Court as it hears a case on possible partisan gerrymandering by state legislatures on October 3, 2017. (photo: Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call)

The Biden administration makes a persuasive case that Texas violated the Voting Rights Act, but the Supreme Court hates the Voting Rights Act.

The Justice Department’s complaint in United States v. Texas is a fine, workmanlike legal document that makes a strong case that Texas drew its maps in order to maximize white power within the state and minimize the impact of Black and Latino voters. It’s the sort of lawsuit that would have a good shot at prevailing — if the Supreme Court hadn’t spent the past decade dismantling nearly all of the Voting Rights Act.

As the complaint notes, between the 2010 and 2020 censuses, “Texas grew by nearly 4 million residents, and the minority population represents 95% of that growth.” Because of this population growth, Texas’s US House delegation expanded from 36 seats to 38 seats in the decennial redistricting process. Yet Texas drew its new maps so that both of the new districts will have white majorities, and it also allegedly redrew a third district to prevent Latinos from electing their preferred candidate.

The result is that white voters will gain the ability to elect two additional congressional representatives, even though Texas owes its two new seats almost entirely to Black, Asian, and Latino voters.

The Justice Department also alleges that both the new congressional maps and the new state house maps drastically underrepresent voters of color. If Latinos controlled seats proportional to their population, the complaint claims, they would control “11 Congressional seats and 45 Texas House seats.” Black voters, meanwhile, would control “5 Congressional seats and 20 Texas House seats.”

Instead, under the new maps, “Latino voters have the opportunity to elect their preferred candidates in 7 Congressional seats and 29 Texas House seats,” and “Black voters have the opportunity to elect their preferred candidates in roughly 3 Congressional seats and 13 Texas House seats.” (There is one additional congressional seat and five additional state house seats that might elect candidates preferred by a coalition of Black, Latino, and other nonwhite voters.)

Yet it’s uncertain whether the Justice Department is capable of prevailing in this lawsuit, no matter what evidence it presents at trial. That’s how hostile the Supreme Court’s Republican appointees are toward the Voting Rights Act.

As Justice Elena Kagan wrote in her dissenting opinion in Brnovich v. DNC (2021), the Court “has treated no statute worse” than the Voting Rights Act. The Court has also shielded states from federal lawsuits alleging partisan gerrymandering — a decision that potentially gives Texas a powerful weapon it can use against the Justice Department’s allegation that its new maps are an unlawful racial gerrymander.

The Supreme Court has made it nearly impossible to prove that maps were enacted with racist intent

In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Supreme Court held that federal courts may not hear lawsuits alleging that a state’s legislative maps are an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander — meaning that the lines were drawn to benefit one party at the expense of another. The Court’s precedents, however, do permit lawsuits challenging racial gerrymanders — meaning that the lines were drawn to diminish the power of one or more racial groups.

In practice, however, Rucho creates a potentially serious problem for anyone alleging racial gerrymandering.

Recall that the Voting Rights Act prohibits election laws enacted for the purpose of limiting a racial group’s voting power, or that have the effect of doing so. Suppose that the Justice Department leans into the first of these two prongs: the prohibition on laws that are enacted with racist intent.

In that case, Texas is likely to argue, as it has in previous cases accusing it of racial gerrymandering, that its new maps weren’t drawn in order to reduce the power of Black and Latino voters. It will most likely argue that the maps were drawn for the purpose of reducing the power of Democratic voters.

Such an argument might even be superficially plausible. As the Justice Department argues in its complaint, “voting in Texas continues to be racially polarized throughout much of the State” — meaning that white voters tend to vote for Republicans and Black and Latino voters tend to vote for Democrats. So it’s fairly difficult to prove conclusively that the new maps were drawn with racist intent. A set of maps drawn to maximize the power of white Texans, and a set of maps drawn to maximize the power of Texas Republicans, are likely to closely resemble each other because race is a good proxy for partisan affiliation in Texas — as it is in much of the United States.

Of course, this argument that partisan gerrymandering is distinct from racial gerrymandering could fail — and, in a fair court, it probably would fail. If state lawmakers intentionally minimized the influence of Black and Latino voters because they knew those voters were likely to be Democrats, that’s still intentional race discrimination.

But if the Justice Department wants to show that Texas’s new maps were drawn with invidious racial intent, it still must overcome another of the Court’s decisions: Abbott v. Perez (2018).

Perez held that lawmakers enjoy a high presumption of racial innocence when they are accused of drawing racially gerrymandered maps. In that case, the Court considered legislative maps that Texas’s Republican legislature drew in 2011, and then altered in 2013.

The 2011 maps never took effect because of litigation alleging that they were an unlawful racial gerrymander. Yet in 2012, while this litigation was ongoing, a federal court drew interim maps that closely resembled the racially gerrymandered 2011 maps, so that Texas had something it could use to hold an election in 2012. The purpose of these stopgap maps wasn’t to declare any portion of the 2011 maps legally valid. It was just to ensure that the 2012 election could still move forward in Texas.

Then, in 2013, the Texas legislature adopted these stopgap maps as its own — including several districts that were still being challenged as unlawful racial gerrymanders.

In upholding these 2013 maps, Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion in Perez emphasizes that “whenever a challenger claims that a state law was enacted with discriminatory intent, the burden of proof lies with the challenger, not the State.” Alito then explained that this burden is quite high.

He deemed the 2013 maps legitimate because, he claimed, the evidence showed that Texas enacted them because it “wanted to bring the litigation about the State’s districting plans to an end as expeditiously as possible.”

Alito’s argument, in other words, was that the 2013 maps weren’t enacted to preserve a racial gerrymander; they were enacted to shut down litigation challenging a racial gerrymander. And this distinction was sufficient to absolve the state legislature of any allegation of racism.

Needless to say, the sort of Court that would rely on such a meaningless distinction is unlikely to be sympathetic to DOJ’s new lawsuit against Texas — and the Court has grown significantly more conservative since Perez was decided. Perez will also shape lower court decisions applying the Voting Rights Act, because lower courts are obligated to follow Supreme Court decisions.

The Supreme Court does not care about what the Voting Rights Act actually says

Alternatively, the Justice Department can argue that Texas’s maps are illegal because they have the effect of diminishing minority voting power, even if they were not enacted with racist intent. The Voting Rights Act does not simply bar intentional discrimination, it also prohibits any election law that “results in a denial or abridgement of the right ... to vote on account of race or color.”

But in Brnovich, the Court imposed a number of novel and completely atextual limits on this provision of the Voting Rights Act. Among other things, Brnovich held that there is a strong presumption that voting restrictions that were commonplace in 1982 are valid — even though the text of the law says nothing about the year 1982. Brnovich also applied a similar presumption to laws that purport to combat fraud at the polls — even though there’s nothing in the law’s text supporting this presumption either.

One of the few silver linings of the Brnovich decision is that its holding is limited to only certain kinds of cases. The Court distinguished between cases alleging “vote-dilution” — and gerrymandering cases are considered vote-dilution cases — and cases challenging laws regulating the “time, place, or manner” in which elections are conducted. The specific extratextual limits on the Voting Rights Act that were fabricated by the Brnovich opinion do not apply to vote-dilution cases.

But the Justice Department should take no comfort in that fact. Brnovich is a troubling case not only because it imposes novel and entirely made-up new limits on certain Voting Rights Act cases. It is also troubling because of what it says about the Court’s overarching approach to the Voting Rights Act.

Simply put, if the Court is willing to make up new limits on a federal statute that appear nowhere in the text of the law, and apply those limits in “time, place, or manner” lawsuits, there’s no reason to believe that it won’t invent similarly atextual limits and impose them on vote-dilution cases. As Justice Kagan wrote in her Brnovich dissent, “the majority’s opinion mostly inhabits a law-free zone.” Once a court enters that zone, there are no longer any constraints on its judges.

Brnovich doesn’t necessarily mean that the Court will never rule in favor of a voting rights plaintiff — in this case, the Justice Department. But it does suggest that the Court will do whatever the hell it wants in voting rights cases, regardless of what the law actually says.

A man holds his daughter by the hand after she and his wife were deported from the U.S. in 2018. (photo: Orlando Estrada/AFP/Getty Images)

A man holds his daughter by the hand after she and his wife were deported from the U.S. in 2018. (photo: Orlando Estrada/AFP/Getty Images)

Trump petitioned to remove right to unionize for hundreds of immigration judges, and now union says Biden has made no attempt to restore its status

The head of the federal immigration judges’ union has accused the Biden administration of “doubling down” on its predecessor’s efforts to freeze out their association even as they struggle with a backlog of almost 1.5m court cases and staff shortages, which exacerbate due process concerns in their courts.

Mimi Tsankov, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges (NAIJ), declared herself “mystified” that Biden’s Department of Justice would not negotiate with her members despite the US president vocally and frequently touting his support for workers’ representation.

“This administration has really doubled down on maintaining the [Trump] position that we are not a valid union,” Tsankov said.

Tsankov was appointed as an immigration judge in 2006 and is based in New York, where she also teaches at Fordham University School of Law. She spoke to the Guardian only in her union role.

After what she described as “decades” of relatively smooth relations between the NAIJ and the Department of Justice, Donald Trump capped four years of rightwing immigration policy by successfully petitioning to strip hundreds of immigration judges of their right to unionize.

The hostile move was decided by the Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA), an independent administrative federal agency that controls labor relations between the federal government and its employees, on 2 November 2020, the day before the presidential election.

Despite a Democratic victory and Joe Biden taking the White House pledging to undo damage done by Trump, the union remains shut out and silenced without a date set to hear its case attempting to restore its official status.

“I cannot understand it … Working together, as the president has stated, working with federal employees, working with unions, achieves better results,” said Tsankov.

The justice department did clear the way in June for the judges’ union to at least ask for its rights back when the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) – home to the country’s immigration courts – withdrew opposition to the NAIJ’s motion for reconsideration.

However, Tsankov said the administration was still refusing to negotiate. A hearing on Tuesday will pit the union against EOIR as the dispute deepens.

The complaint in question accuses EOIR of “interfering with, restraining and coercing employees in the exercise of their rights” to organize and “refusing to negotiate in good faith”.

In a formal response to the complaint, EOIR has stated that “in essence, the NAIJ is defunct”.

Administration officials went so far as to file a motion to dismiss the NAIJ’s grievances about unfair labor practices, though the motion was denied.

Tsankov said in a phone interview last week: “Good faith, in my mind, would have said, if we really cared about this union, this administration would have started negotiating with us. But they haven’t, so we’re really mystified as to why.

“I don’t think there’s any other way to say it … They have simply doubled down on this policy, and it is counterintuitive given the positions that the president has set forth,” she said.

EOIR does not comment on continuing litigation.

The conflict rumbles on as the nation’s immigration courts tackle crushing case loads with severe shortages of vital personnel such as legal assistants and translators.

Tsankov said one of the New York immigration courts only had about 30% of the staff it needs, and other courts in cities as geographically diverse as Memphis, Salt Lake City, and Philadelphia have been short-staffed for years.

The lack of personnel makes it more difficult for judges to be fully prepared for hearings and can even affect whether those in front of the courts, often including migrants at the US-Mexico border, receive adequate notice of important changes to their cases.

She suggested that shifting political priorities between administrations might have focused resources on law enforcement instead of hiring more staff to make the immigration courts run more efficiently.

“It has a very real impact on the ability of respondents who are seeking justice … to ensure that they’re receiving a fair hearing,” said Tsankov.

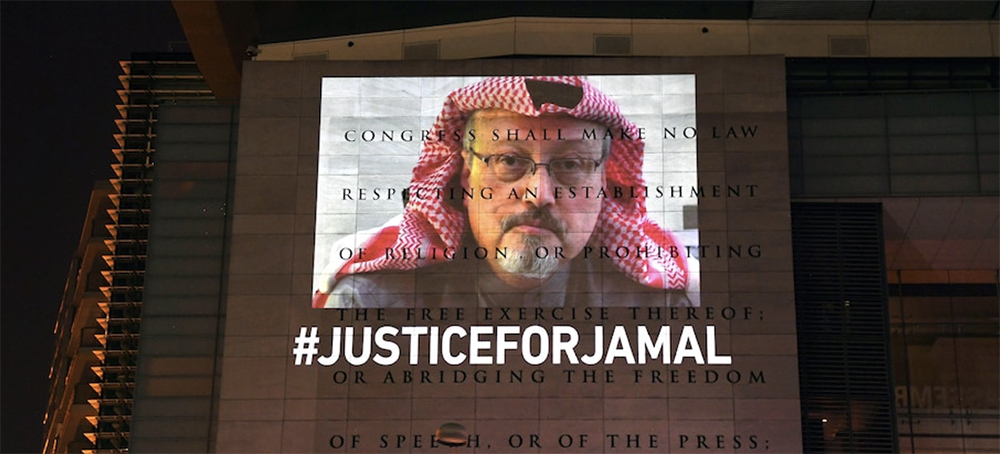

A projected story line and images (featuring Jamal Khashoggi, President Trump and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman) were projected onto the front of the Newseum in Washington, D.C., Oct. 1, 2019. (photo: Michael S. Williamson/WP)

A projected story line and images (featuring Jamal Khashoggi, President Trump and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman) were projected onto the front of the Newseum in Washington, D.C., Oct. 1, 2019. (photo: Michael S. Williamson/WP)

The detention marks the first international arrest for the grisly murder that made Saudi Arabia a global pariah for years.

French authorities detained Khalid Aedh al-Otaibi on an outstanding Turkish arrest warrant, the source said, as Otaibi prepared to travel to Saudi Arabia from Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris.

Proceedings for his extradition to Turkey have begun, Reuters reported.

Otaibi was one of 17 Saudis sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury in 2018 as a member of the operations team that had a role in the murder.

U.S. records showed that a Saudi passport held by a man with the same name as Otaibi was used to enter the United States for trips that overlapped with three visits by members of the royal family. The Post in 2018 found his contact identified with a symbol of the Royal Guard in the Arabic caller-ID app MenoM3ay.

A Saudi official, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the case, said he had no information on the arrest.

Otaibi was allegedly part of a 15-member team sent to execute the grisly murder of Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on Oct. 2, 2018. Khashoggi had become a target after voicing criticism of the young Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and had entered the consulate to obtain legal paperwork, believing he was safe in Turkey.

The arrest is the first outside of Saudi Arabia, and comes two days after French President Emmanuel Macron met with Mohammed, the first major Western leader to visit the country and meet with the prince since Khashoggi’s killing.

A Saudi court in 2019 sentenced five people to death and three to jail over the murder of the journalist, but the death sentences were later overturned after some of Khashoggi’s family members forgave his killers, enabling the sentences to be set aside according to Saudi law.

A U.N. investigator at the time accused the court proceedings of making a “mockery” of justice for allowing the masterminds behind the operation to go unpunished.

Turkey, which first publicized the news of Khashoggi’s murder and called for senior Saudi leaders to be held to account, began a trial last year for 20 people alleged to have played a role in the journalist’s killing. All of the suspects were believed to be in Saudi Arabia and were being tried in absentia. The last hearing in the case was held earlier this month.

But hopes that the trial would reveal new information about what happened to Khashoggi — or result in convictions that would embarrass the Saudi monarchy — have dimmed as Turkey has tried to mend its relationship with Saudi Arabia and halted its previous, public denunciations of the kingdom for covering up the murder as well as the role of senior officials.

The names and photos of the 15 Saudi men that played a role in Khashoggi’s disappearance were first published by Sabah, a Turkish newspaper close to the Turkish administration. The administration at the time took the lead in unraveling what had happened to Khashoggi, who had a close relationship with high-level Turkish officials.

'At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5°C will be depleted in six years.' (photo: Friedemann Vogel/EPA)

'At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5°C will be depleted in six years.' (photo: Friedemann Vogel/EPA)

This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries

There is a fundamental problem in contemporary discussion of climate policy: it rarely acknowledges inequality. Poorer households, which are low CO2 emitters, rightly anticipate that climate policies will limit their purchasing power. In return, policymakers fear a political backlash should they demand faster climate action. The problem with this vicious circle is that it has lost us a lot of time. The good news is that we can end it.

Let’s first look at the facts: 10% of the world’s population are responsible for about half of all greenhouse gas emissions, while the bottom half of the world contributes just 12% of all emissions. This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries.

Consider the US, for instance. Every year, the poorest 50% of the US population emit about 10 tonnes of CO2 per person, while the richest 10% emit 75 tonnes per person. That is a gap of more than seven to one. Similarly, in Europe, the poorest half emits about five tonnes per person, while the richest 10% emit about 30 tonnes – a gap of six to one. (You can now view this data on the World Inequality Database.)

Where do these large inequalities come from? The rich emit more carbon through the goods and services they buy, as well as from the investments they make. Low-income groups emit carbon when they use their cars or heat their homes, but their indirect emissions – that is, the emissions from the stuff they buy and the investments they make – are significantly lower than those of the rich. The poorest half of the population barely owns any wealth, meaning that it has little or no responsibility for emissions associated with investment decisions.

Why do these inequalities matter? After all, shouldn’t we all reduce our emissions? Yes, we should, but obviously some groups will have to make a greater effort than others. Intuitively, we might think here of the big emitters, the rich, right? True, and also poorer people have less capacity to decarbonize their consumption. It follows that the rich should contribute the most to curbing emissions, and the poor be given the capacity to cope with the transition to 1.5C or 2C. Unfortunately, this is not what is happening – if anything, what is happening is closer to the opposite.

It was evident in France in 2018, when the government raised carbon taxes in a way that hit rural, low-income households particularly hard, without much affecting the consumption habits and investment portfolios of the well-off. Many families had no way to reduce their energy consumption. They had no option but to drive their cars to go to work and to pay the higher carbon tax. At the same time, the aviation fuel used by the rich to fly from Paris to the French Riviera was exempted from the tax change. Reactions to this unequal treatment eventually led to the reform being abandoned. These politics of climate action, which demand no significant effort from the rich yet hurt the poor, are not specific to any one country. Fears of job losses in certain industries are regularly used by business groups as an argument to slow climate policies.

Countries have announced plans to cut their emissions significantly by 2030 and most have established plans to reach net-zero somewhere around 2050. Let’s focus on the first milestone, the 2030 emission reduction target: according to my recent study, as expressed in per capita terms, the poorest half of the population in the US and most European countries have already reached or almost reached the target. This is not the case at all for the middle classes and the wealthy, who are well above – that is to say, behind – the target.

One way to reduce carbon inequalities is to establish individual carbon rights, similar to the schemes that some countries use to manage scarce environmental resources such as water. Such an approach would inevitably raise technical and information issues, but it is a strategy that deserves attention. There are many ways to reduce the overall emissions of a country, but the bottom line is that anything but a strictly egalitarian strategy inevitably means demanding greater climate mitigation effort from those who are already at the target level, and less from those who are well above it; this is basic arithmetic.

Arguably, any deviation from an egalitarian strategy would justify serious redistribution from the wealthy to the worse off to compensate the latter. Many countries will continue to impose carbon and energy taxes on consumption in the years to come. In these contexts, it is important that we learn from previous experiences. The French example shows what not to do. In contrast, British Columbia’s implementation of a carbon tax in 2008 was a success – even though the Canadian province relies heavily on oil and gas – because a large share of the resulting tax revenues goes to compensate low- and middle-income consumers via direct cash payments. In Indonesia, the ending of fossil fuel subsidies a few years ago meant extra resources for government but also higher energy prices for low-income families. Initially highly contested, the reform was accepted when the government decided to use the revenue to fund a universal health insurance and support to the poorest.

To accelerate the energy transition, we must also think outside the box. Consider, for example, a progressive tax on wealth, with a pollution top-up. This would accelerate the shift out of fossil fuels by making access to capital more expensive for the fossil fuel industries. It would also generate potentially large revenues for governments that they could invest in green industries and innovation. Such taxes would be politically easier to pass than a standard carbon tax, since they target a fraction of the population, not the majority. At the world level, a modest wealth tax on multimillionaires with a pollution top-up could generate 1.7% of global income. This could fund the bulk of extra investments required every year to meet climate mitigation efforts.

Whatever the path chosen by societies to accelerate the transition – and there are many potential paths – it’s time for us to acknowledge there can be no deep decarbonization without profound redistribution of income and wealth.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611