Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

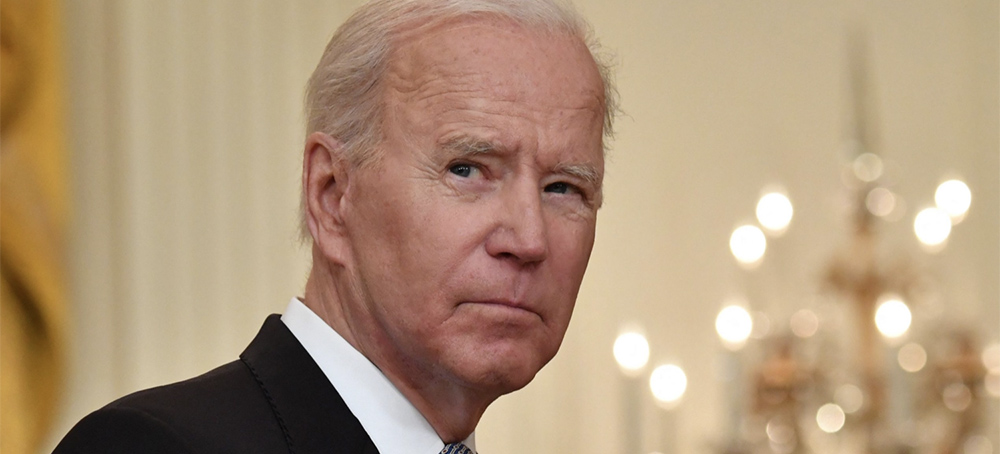

One thing I don't think gets enough emphasis, however, is the extent to which Biden has been hurt by the way the pandemic keeps dragging on -- a dismal reality for which he bears little responsibility. Oh, the messaging could have been clearer, testing and masks made more available, and so on. But Biden's biggest error on Covid-19 was underestimating the ruthlessness of his opponents, who have done all they can to undermine America's pandemic response.

Before I get to the politics of Covid response, let's talk about how pervasively the pandemic's persistence colors the nation's mood.

Some of the effects are direct and obvious. Certainly most Americans, even if they haven't developed Covid themselves, know people who have gotten seriously ill or died.

Furthermore, Covid is still making life difficult in ways large and small. Shuttered schools were a nightmare for many parents; they've reopened in most places but are still subject to unpredictable closings.

Work is also still disrupted. According to the Census Bureau's most recent Household Pulse Survey, 8.7 million Americans were not working because they were either sick with coronavirus symptoms or caring for someone else who was; 3.2 million more weren't working out of fear of contracting or spreading the virus.

And Covid is contributing to our economic problems. Fear of face-to-face contact has skewed consumer spending away from services toward goods, straining supply chains and fueling inflation. Both fear of infection and burnout among workers who have been coping with the pandemic's strains are probably major factors in labor shortages, which are also contributing to inflation.

One of the puzzles in recent polling is why public assessments of the economy are so negative despite plunging unemployment. It's true that inflation has eroded real wages -- but George H.W. Bush ran on a strong economy in 1988 even though real wages fell for most of Ronald Reagan's second term. And as I and others have noted, there's a big disconnect between Americans' assessment of their own financial situation -- which is pretty positive -- and their grim assessment of "the economy."

Partisanship surely plays a big role, with Republicans claiming that the economy is as bad now as it was in early 2009, when we were losing 700,000 jobs a month. But the pandemic probably also darkens perceptions: Aside from a general sense of malaise, people see closed shops and empty office buildings, which makes things look worse than they are.

What makes all of this especially demoralizing is that 2021 began with the hope that miraculous vaccines would end the pandemic. Despite the effectiveness of the vaccines in preventing serious illness, that didn't happen even in highly vaccinated countries. But America is doing especially badly because it isn't a highly vaccinated country: After a strong start, its vaccination drive fell far behind other wealthy nations.

And while there are various reasons individuals fail to get vaccinated, at a national level our shortfall is all about politics. Vaccination rates in blue states are similar to those in other advanced countries, while the rates in red states are far behind; at the county level there's a stunning negative correlation between Donald Trump's share of the 2020 vote and the vaccination rate.

Why do many Republicans refuse the vaccines? Because they're getting a steady stream of misinformation from right-wing media, while right-wing politicians have gradually shifted from claiming to be against vaccine mandates to being straight-out anti-vax. For example, recently the medical director for Orange County, Fla., was placed on leave simply for encouraging -- not requiring -- the staff to get vaccinated.

But why are right-wing elites so hostile to vaccines? Have they carefully considered the evidence? Don't be silly.

Their real motive is the desire to prevent Democrats from achieving any kind of policy success. And is it really implausible to suggest that some leading figures on the right actively want to make things worse, in the belief that the public will blame Biden?

But while the public does indeed tend to blame presidents for anything bad that happens on their watch, they can fight back. In 1948 Harry Truman successfully campaigned against "do-nothing" Republicans who were blocking his economic and housing agenda. Biden could, with even more justification, campaign against Republicans whose anti-vaccine posturing is putting both the national economy and thousands of American lives at risk.

Would this work? Nobody knows. What we do know is that a year of trying to be conciliatory and unifying hasn't worked. It's time for Biden to come out swinging.

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

The order, which was obtained by Politico, was never signed by the former president.

The order, which was never signed by Trump, also would have appointed a special counsel "to institute all criminal and civil proceedings as appropriate based on the evidence collected," and calls on the defense secretary to release an assessment 60 days after the action started, which would have been well after Trump was set to leave office on Jan. 20, 2021.

The Politico article includes a facsimile of the full order, but does not say how the news organization obtained the document or whose possession it was in.

The draft executive order appears to be among the files the House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol was seeking to obtain from the National Archives.

The committee had revealed what it sought in the documents in a court filing, and it included “a draft Executive Order on the topic of election integrity" and “a document containing presidential findings concerning the security of the 2020 presidential election and ordering various actions.”

Those documents were handed over to the committee this week after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Trump's request that it block the documents from being handed over.

A representative of Trump did not respond to a request for comment.

It is unclear who wrote the draft document, which is dated Dec. 16, 2020, and titled, "PRESIDENTIAL FINDINGS TO PRESERVE COLLECT AND ANALYZE NATIONAL SECURITY INFORMATION REGARDING THE 2020 GENERAL ELECTION." It parrots arguments that were made by lawyer Sidney Powell and former national security adviser Michael Flynn during a Dec. 18 meeting at the White House.

In the meeting, which was first reported by The New York Times and later confirmed by NBC News, Trump discussed naming Powell, who'd championed numerous bogus conspiracies about the election, as special counsel.

The draft order doesn't identify the person Trump would name as special counsel, but does refer to the person a "her."

Powell could not be reached for comment.

The order also bases the need for the unprecedented action on Powell's debunked allegations of widespread voter fraud and foreign interference in the election.

It cites a "forensic report" championed by Powell that falsely accused Dominion Voting System machines of being "intentionally and purposefully designed with inherent errors to create systemic fraud and influence election results." Dominion is suing Powell for defamation.

Evan Smith, co-founder and CEO of the Texas Tribune, at a panel discussion in Edinburg, Tex., in 2019. (photo: Verónica G. Cárdenas/The Texas Tribune)

Evan Smith, co-founder and CEO of the Texas Tribune, at a panel discussion in Edinburg, Tex., in 2019. (photo: Verónica G. Cárdenas/The Texas Tribune)

The Texas Tribune founder has been a “true pioneer” in finding ways to cover local communities as a non-profit.

So his move from top editor of the award-winning Texas Monthly magazine, at the urging of venture capitalist John Thornton, was considered slightly bizarre.

“The tone of the coverage was almost mocking,” Smith recalled this week, soon after he announced he would step down as the Tribune’s CEO at the end of this year. “It was ‘what does this joker think he’s doing?’”

As it turns out, Smith and company — he and Thornton recruited Texas Weekly editor Ross Ramsey to join the endeavor — had a good idea of what they were doing, or figured it out along the way.

The Austin-based Tribune has grown from 17 employees to around 80 (more than 50 are journalists), raising $100 million through philanthropy, membership and events, including its annual Texas Tribune Festival that has attracted speakers from Nancy Pelosi to Willie Nelson. Most important, it has done a huge amount of statewide news coverage with a focus on holding powerful people and institutions accountable.

These days, such newsrooms are springing up everywhere; there are now hundreds of them. They are easily the most promising development in the troubled world of local journalism, where newspapers are going out of business or vastly shrinking their staffs as print revenue plummets and ownership increasingly falls to large chains, sometimes owned by hedge funds.

In Baltimore, the Banner — funded by Maryland hotel magnate Stewart Bainum — is hiring staff and expects to start publishing soon. In Chicago, the Sun-Times is converting from a traditional newspaper to a nonprofit as it merges operations with public radio station WBEZ. And in Houston, three local philanthropies working with the American Journalism Project (also co-founded by Thornton) announced a $20 million venture that will create one of the largest nonprofit news organizations in the country.

“These newsrooms are popping up like mushrooms after a rainstorm,” Smith, 55, told me.

He’s right about the growth of nonprofit news — and he’s also one of the reasons it’s thriving. “A true pioneer,” wrote Peter Lattman, managing director of media at the Emerson Collective, the philanthropic corporation funded by Laurene Powell Jobs.

As a speaker at Trib Fest myself, I’ve seen Smith in action — a promotional force of nature, energetic organizer, prodigious fundraiser, and lively onstage interviewer.

Emily Ramshaw, who started at the Trib as a reporter and was named its top editor in 2016, called him “an innovator, a ringleader and a fearlessly ambitious local news entrepreneur.” What’s more, she told me, Smith has brought along “a whole series of news leaders who have grown up in his image.”

Rawshaw counts herself among them; she left the Trib in 2020 to found a new nonprofit news organization, the 19th, which covers the intersection of gender, politics and society.

The Trib’s new editor is Sewell Chan, most recently at the Los Angeles Times, where he was the top opinion-side editor, and previously at the New York Times and The Washington Post. Smith considers it a triumph for nonprofit newsrooms that it’s no longer unusual for them to attract the likes of Chan, or of Kimi Yoshino, who was managing editor of the L.A. Times before being named editor in chief of the Baltimore Banner.

“Now when people like Sewell Chan or Kimi Yoshino come to a nonprofit newsroom, no one is mocking their decisions,” Smith said. (He has no immediate plans for what he’ll do after stepping down as CEO, saying that it simply was the right time to make the move; he’ll remain as an adviser for another year.)

The Trib’s journalism is influential well beyond its own free website. More than 400 Texas Tribune stories appeared on the front pages of newspapers throughout the state last year, provided free of charge. The site has done investigative projects on the effect of sex trafficking on young girls, the influence of religious belief on the lawmaking of Texas legislators, and an investigation, part of its voting rights coverage, into the state’s review of voting rolls. In 2019, it announced it was joining forces with ProPublica to form a new investigative unit based in Austin.

“No state is more in need of watchdog reporting than Texas,” Smith said when that effort was launched. “It’s a target-rich environment if you’re in the business of holding people in power and institutions accountable.”

But far from the only one. With local news outlets withering in many communities — statehouse coverage, in particular, has dwindled despite its importance — and democratic norms under attack in many states, the need for that kind of watchdog reporting is acute everywhere.

If local journalism proves itself up to these challenges — and I fervently hope it will — Evan Smith will deserve a share of the credit, no matter what he decides to do next.

CareRev and similar start ups want to introduce the gig-economy model to health care, allowing hospitals to source temporary staff locally for much less than they pay for either full-time or travel nurses. (photo: SJ Objio/Unsplash)

CareRev and similar start ups want to introduce the gig-economy model to health care, allowing hospitals to source temporary staff locally for much less than they pay for either full-time or travel nurses. (photo: SJ Objio/Unsplash)

“It's like Uber, but for nurses.” Does that scare you? It should. Private hospitals are increasingly teaming up with Silicon Valley to make American health care even more exploitative.

The solution isn’t overly complicated. It all goes back to supply and demand. By creating a pool of ready skilled labor willing to work as needed instead of only full-time, healthcare systems can take advantage of professionals who want to work to tackle fluctuating needs.

Translation: Uber for nurses.

The idea has been gathering steam during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has pushed America’s capitalist health care system to its limits, dramatically exposing and exacerbating preexisting issues. The imperative for health care to turn a profit has left hospitals woefully understaffed, under-resourced, and unable to properly deal with the influx of COVID-19 patients. Thus, the question of the health care labor market has been driven to the fore, with everyone agreeing that something needs to change.

But instead of acknowledging that decades of pinching pennies and cutting corners led to this chaotic juncture and course-correcting by sacrificing future profits to permanently increase capacity, major health care companies have opted for a more predictable response. They’ve united with venture capital and Silicon Valley in a depressingly on-brand pivot to the gig economy.

Saving money on labor, regardless of the outcome for workers and patients, is the name of the game in hospital management. It’s how we got into this mess to begin with. And it seems the responsible parties know better than to let a good crisis go to waste.

The Flexibility Trap

CareRev, which received $50 million in series A funding from Transformation Capital earlier last year, is just one of several companies looking to “bring a different perspective” to health care labor. The company does not employ nurses; instead, it functions as a technology-driven platform that connects hospitals needing shifts filled to nurses and other health care specialists looking for work on their own schedule. Like Uber drivers, these nurses operate as independent contractors.

Because nurses who use CareRev are not employees of the company, they aren’t eligible for benefits through it. CareRev offers its users the ability to purchase health care through a partnership with Stride Health — the same insurance broker that works with other gig work companies like Uber. And that’s as far as benefits extend. Workers using the app are left to their own devices to manage tax contributions, retirement funds, and what to do about money when they need time off.

According to proponents of the new model, it’s not the management-by-stress techniques employed by profit-focused hospital executives that are driving the labor exodus from health care. The problem is the lack of “flexibility.” It’s not understaffed and under-resourced hospital floors, according to Ahrens, but the “red tape (of) regulatory and licensing hurdles to practice” and the “onerous onboarding and credentialing processes that keep professionals in orientations instead of actually providing care” that are making people leave the profession they once cared deeply about. CareRev advertises higher wages to nurses than standard full-time employment, but in pitching the gig model to hospital administrators, Ahrens advises that “engaging professionals beyond money by focusing on flexibility is key.”

The word “flexibility” does a lot of heavy lifting in selling gig work as innovative and emancipatory for workers. However, as political scientist and author of the book Consumer Management in the Internet Age: How Customers Became Managers in the Modern Workplace Joshua Sperber told Jacobin, “Flexibility means you’re fundamentally precarious.” Sperber noted that in traditional labor markets, workers compete with each other to fill job openings, but once in the workplace, they often find shared interests and some measure of stability. With the gig economy, workers are constantly in competition with each other for the next shift. Gig companies, says Sperber:

promote the idea that you have the choice to say yes or no, pick up what hours you want or set your own rates, and in practice, that’s never going to work because you’re competing with a whole bunch of other comparably qualified professionals. So, there’s not only increasing downward pressure on wages, but there’s also pressure to accept jobs even when they’re forty miles away.

Companies like CareRev and its competitors — ShiftMed, Trusted Health, Nomad Health, connectRN — are raising tens of millions of dollars in venture capital investment because they provide value to their customers. But their customers are not the health care workers who want to earn a living on their platforms. Their actual customers are for-profit hospitals desperate to cut labor costs.

Labor historian and history professor at University of Chicago Gabriel Winant examined the relationship between neoliberal capitalism and the health care industry in his book The Next Shift: The Fall of Manufacturing and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America. He spoke with Jacobin about how health care employers have historically viewed labor as a hindrance to their profits rather than facilitators of care to their patients:

Individual employers — hospitals, nursing homes, home care agencies — have incentives to try to hold down their staffing levels as much as possible, since this is the best way for them to make their margins work. In consequence, health care is run increasingly on a “lean” basis, at the bare minimum of staffing, and then, when there is a need to increase supply, firms like CareRev are positioned to profit; it’s good for them and good for hospitals but bad for workers and bad for patients.”

Lean, Mean Profit Machine

The lean paradigm and resulting worker burnout existed long before the pandemic. The focus on margins rather than patient care, justified by the assumption that the same efficiency that increased profit would also benefit patients, led hospitals to look to automotive manufacturing as the template for how health care should be administered.

Originating in the auto industry, “just-in-time” production is the practice of dynamically scaling labor, resources, and production to match demand — always ordering parts or workers at the last minute based on a real-time assessment of needs, and never keeping extra reserves on hand since doing so might be financially wasteful. For hospitals, this has meant reducing the number of hospital beds and carrying the absolute minimum of drugs and personal protective equipment (PPE). And since labor remains the biggest cost to any hospital, reducing full-time staff has become a key feature of “successful” hospital administration.

Hospital administrators will fight tooth and nail for the continued ability to put their patients’ health and their workers’ well-being in jeopardy for profit. We saw this clearly in Massachusetts, where nurses at Saint Vincent Hospital recently ended the longest nurses’ strike in state history over safe staffing levels. And the pandemic has only increased hospitals’ appetite for cheap and flexible labor.

Before the pandemic, hospitals were mostly content to supplement their lean staffing with travel nurses from staffing agencies. Travel nurses typically are engaged in six- or twelve-week contracts at the same hospital. Some eventually are hired on full-time. Travel nurses are also likely to be compensated for the expenses related to moving for a job. Hospitals spend more for temporary travel nurses than they do for ordinary full-time nurses, but as Winant explained:

Many travel nurses have put themselves in harm’s way out of a sense of obligation or a justifiable desire for a pay bump or both in the past two years, and there’s nothing wrong — and even something laudable — about the individual choice to do that. And of course, nurses should have the right to adventure and travel and mobility, just like everyone should. But this industry is currently tied to a model where hospitals don’t employ enough nurses or other workers even during normal times — don’t pay them enough or treat them with the respect they deserve — and the travel nurses are brought in to cover over that ugly reality when it starts to show.

The cost of travel nurses has increased substantially over the pandemic. Some hospitals are paying over $200 an hour for nurses to take shifts. Some agencies have begun to import nurses from other countries to meet the demand and potentially lower costs, but hospitals are becoming frustrated with the time it takes to get foreign-born medical professionals through immigration.

CareRev and its fellow harbingers of gigification are seeking to remedy this contradiction, allowing hospitals to source temporary staff locally for much less than they pay for either full-time or travel nurses. Hospitals can have cheap labor on hand when they need it, and they bear no responsibility for those workers when there’s no immediate demand for their skills. In that sense, the Uber-for-nurses model is the dystopian logical conclusion of just-in-time production as applied to health care.

And there are other benefits to the gig model for health care employers. As the Saint Vincent nurses demonstrated, unions have some ability to change their working conditions — directly through striking, but also indirectly through organizing to pass bills like they did in California, where safe staffing levels are now state mandated.

In the gig economy, there is no communal space for workers to meet and organize. Instead of talking with fellow nurses about looking for work and how they are treated by hospital administration, job seekers are stuck looking at their phones trying to decide if the shift located forty miles away is worth it. Gigification is the most direct method of labor atomization capitalism has ever employed.

The Burnout-to-Precarity Pipeline

The pandemic prompted a surge of unemployed and underemployed workers to risk their health and enter the gig economy. A recent Pew Research Center study found that 9 percent of Americans performed some sort of app-based gig labor in the past year. Most reported that it was not their main source of income but rather a way to make ends meet or to save some extra money in a financially stressful and uncertain time. Over a third of respondents said that gig work was essential or important for making ends meet, with 52 percent saying that their motivation in taking gig work was covering for fluctuations in income. Pew notes that majorities of gig workers are satisfied with the work and pay, and feelings about the lack of benefits are basically split down the middle.

There are people for whom the gig model is perfect for their needs. According to Pew, 35 percent of gig workers got into it because they wanted to be their own boss. It’s uncertain how many of those 35 percent actually enjoy “self-employment” once they are doing it.

The problem, in any case, is that gig work isn’t self-employment. Organizations like the Gig Workers Collective, led by Instacart worker Vanessa Bain, are trying to fight against the misclassification of employees as independent contractors. Bain related to Jacobin that the autonomy nominally granted to gig workers is superficial. Workers’ options are determined by ratings systems and algorithms. They do not get to set their own rates. Their compensation is also set by algorithms — and, in the case of CareRev, the deals negotiated with hospitals looking to cut labor costs.

It’s disingenuous for health care gig work companies like CareRev to sell themselves as an antidote for burnout, when in fact they’re helping hospitals facilitate the lean staffing ratios that are a major contributor to burnout. And in fact, this new trend is likely to exacerbate the burnout we’re seeing among health care workers. What Ahrens refers to derisively as the “red tape” of orientation and regulatory certification serves a useful function, preparing new staff for the demands of the job and the specific rhythms and procedures of individual hospital floors. Transient nursing drops uninitiated strangers into already stressful situations and can have the paradoxical effect of making work harder for full-time staff trying to care for their patients while also bringing new staff up to speed.

It’s not unreasonable to predict that the burnout-to-precarity pipeline that health care gig work companies are creating will result in a scenario where staffing consists mostly of gig workers spending the majority of their time split between the same few hospitals, functionally employed but treated like private contractors, their working conditions determined by someone else’s keystrokes.

The ultimate problem with this lean philosophy is not just that it’s inherently vulnerable to unpredictable events like a pandemic — though that is a serious flaw, as the last two years have demonstrated. The ultimate problem is that it treats workers and patients as little more than inputs in a system designed to generate profit. Do we want a health care system designed to heal us when we’re sick, or do we want a business scheme designed to enrich a few executives at everyone else’s expense? In the end, we can only choose one.

A bronze statue of Theodore Roosevelt on a horse with a Native American man on one side and an African man on the other side stands in front of the American Museum of Natural History on June 30, 2020 in New York. (photo: Liao Pan/China News Service/Getty Images)

A bronze statue of Theodore Roosevelt on a horse with a Native American man on one side and an African man on the other side stands in front of the American Museum of Natural History on June 30, 2020 in New York. (photo: Liao Pan/China News Service/Getty Images)

ALSO SEE: Theodore Roosevelt:

'The Only Good Indians Are the Dead Indians'

"The process, conducted with historic preservation specialists and approved by multiple New York City agencies, will include restoration of the plaza in front of the Museum, which will continue through the spring," a museum spokesperson said in a statement.

"The Museum is proud to continue as the site of New York State’s official memorial to Theodore Roosevelt."

The bronze sculpture of Roosevelt on horseback with Native American and African figures on either side of him has gazed out across Central Park West from a public plot of land outside the entrance of the American Museum of Natural History since 1940.

The statue had long drawn accusations of racism, and in 2020, the museum requested its removal because of its depiction of subjugation and racial inferiority, and former mayor Bill de Blasio quickly indicated his support.

"It is the right decision and the right time to remove this problematic statue," the former mayor said.

The museum said its request was prompted by the killing of George Floyd on May 25 and the demonstrations protesting racism that have followed.

The New York City Public Design Commission approved its removal and relocation in June, and in November, the museum announced the statue would be moved on long-term loan to the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in North Dakota.

Historians regard Roosevelt’s legacy as both “progressive” and “racist” as he “viewed other peoples around the world as distinctly inferior to Americans.”

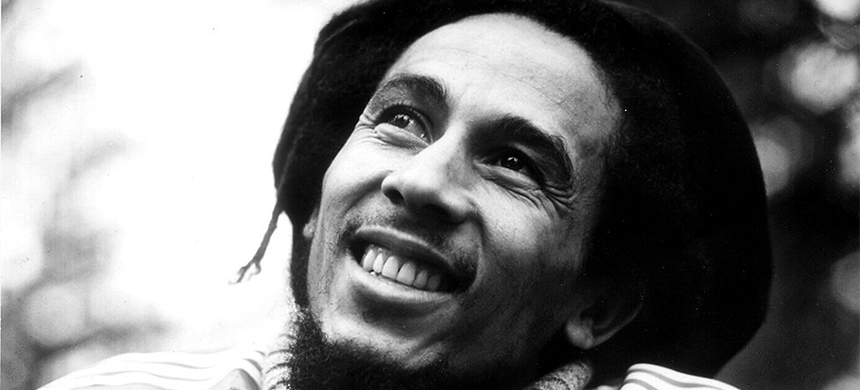

Singer, songwriter, poet Bob Marley. (photo: AP)

Singer, songwriter, poet Bob Marley. (photo: AP)

Lyrics: Bob Marley | Redemption Song

From the 1980 album, Uprising

Old pirates, yes, they rob I;

Sold I to the merchant ships,

Minutes after they took I

From the bottomless pit.

But my hand was made strong

By the 'and of the Almighty.

We forward in this generation

Triumphantly.

Won't you help to sing

This songs of freedom

'Cause all I ever have:

Redemption songs;

Redemption songs.

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery;

None but ourselves can free our minds.

Have no fear for atomic energy,

'Cause none of them can stop the time.

How long shall they kill our prophets,

While we stand aside and look? Ooh!

Some say it's just a part of it:

We've got to fullfil the book.

Won't you help to sing

This songs of freedom-

'Cause all I ever have:

Redemption songs;

Redemption songs;

Redemption songs.

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery;

None but ourselves can free our mind.

Wo! Have no fear for atomic energy,

'Cause none of them-a can-a stop-a the time.

How long shall they kill our prophets,

While we stand aside and look?

Yes, some say it's just a part of it:

We've got to fullfil the book.

Won't you have to sing

This songs of freedom? -

'Cause all I ever had:

Redemption songs -

All I ever had:

Redemption songs:

These songs of freedom,

Songs of freedom.

As the demand for oil decreases, petrochemical companies are ramping up their plastic production. (photo: Louis Vest/Flickr)

As the demand for oil decreases, petrochemical companies are ramping up their plastic production. (photo: Louis Vest/Flickr)

There are about 350,000 different types of artificial chemicals currently in the global market, from plastics to pesticides to industrial chemicals like flame retardants and insulators. While research has shown that many of these chemicals can have deleterious impacts on the natural world and human health, most substances have not been evaluated, with their interactions and impacts not yet understood or entirely unknown.

“The knowledge gaps are massive and we don’t have the tools to understand all of what is being produced or released or [what is] having effects,” Bethanie Carney Almroth, an ecotoxicologist and microplastics researcher from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, told Mongabay in a video interview. “We just don’t know. So we try to look at what we do know and add up all these little puzzle pieces to get a big picture.”

As scientists endeavor to identify and understand the impacts of chemicals and other artificial substances — referred to en masse as “novel entities” — industries are pumping them out at a staggering rate. The global production of chemicals has increased fiftyfold since 1950, and this is expected to triple by 2050, according to a report published by the European Environment Agency. While some novel entities are regulated by governmental bodies and international agreements, many can be produced without any restrictions or controls.

The mismatch between the rapid rate at which novel entities are being produced, compared to the snail’s pace at which governments assess risk and monitor impacts — leaving society largely flying blind as to chemical threats — is what prompted Carney Almroth and colleagues to make a weighty argument in a new paper published in Science and Technology: that we have breached the “planetary boundary” for novel entities, endangering the stability of the planet we call home.

Quantifying the novel entities boundary

The concept of planetary boundaries was first proposed by a team of international scientists in 2009 to articulate key natural processes that, when kept in balance, support biodiversity; but when disrupted beyond a certain threshold, can destabilize and even destroy the Earth’s ability to function and support life. Nine boundaries have been identified: climate change, biosphere integrity, ocean acidification, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol pollution, freshwater use, biogeochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorus, land-system change, and of course, the release of novel chemicals.

Many of these boundaries have clear thresholds. For instance, scientists determined that humanity would overshoot the safe operating space for climate change when carbon dioxide in the atmosphere exceeded 350 parts per million (ppm), which happened in 1988. The threshold for novel entities, however, has until recently evaded definition, largely because of the knowledge gaps surrounding these substances.

Patricia Villarrubia-Gómez, a plastic pollution researcher at Stockholm University’s Stockholm Resilience Centre, who co-authored the new paper, said these knowledge gaps aren’t present because these chemicals and other polluting substances don’t pose risks — it’s because scientists are still scrambling to understand novel entities and the myriad ways they can impact the natural world.

“It’s a very new field of study,” Villarrubia-Gómez told Mongabay in a video interview. “It’s in its infancy in comparison to other major environmental problems … most research has been done in the past seven years.”

Carney Almroth said researchers have used the Holocene, the current geological epoch that began just over 10,000 years ago, as a measuring point to quantify the thresholds of other planetary boundaries, but this approach wasn’t appropriate for novel entities.

“This boundary is different from the others because the others are all referring back to the Holocene conditions — that was 10,000 years of a very stable Earth system and Earth climate,” Carney Almroth said. Scientists “can look back and ask, ‘What were carbon dioxide levels then and where was nitrogen and phosphorus during that time period?’ and refer back to that [as a baseline]. We couldn’t do that because novel entities didn’t exist during that time period and the background baseline levels would be zero for most of them.”

Instead, the researchers gathered all of the information they could on artificial chemicals and other pollutants, looking at their impacts all along their supply chain, from extraction to production to use, and eventually, to their disposal as waste. Then they used a weight-of-evidence approach to determine that novel entities could, in fact, disrupt the planet’s stability.

“The weight of evidence indicates now that we are exceeding the boundary, but there’s more work to be done,” Carney Almroth said.

Björn Beeler, the international coordinator for the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), who was not involved in this new research, called it a “very smart academic paper” that illustrates the need to act.

“We’re about to enter an exponential growth period,” Beeler told Mongabay in a phone interview. “If you’re concerned about toxic substance exposure, the amount of toxic substances [including plastic pollution] is set to grow three- [or] fourfold in the decades ahead.”

He added: “If you’re worried about it now, it’s set to get a lot worse.”

With science falling far behind in assessing risk, and governments largely failing to regulate chemicals, humanity is flying blind into a future where the unforeseen impacts of chemical pollutants could be catastrophic.

The release of novel entities isn’t the only planetary boundary that humanity has breached. Climate change, biosphere integrity, land system change and the biogeochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorus have also pushed past the safe operating limits that keep Earth a habitable place.

An ‘existential’ threat to humanity

What is known about chemical substances and other pollutants has long raised alarms among experts — dating back to Rachel Carson and the publication of Silent Spring, which helped launch the modern environmental movement. Hazardous chemicals such as pesticides can damage soil health, contaminate drinking water, and even get carried on the wind, to impact a wider environment and disrupt populations of birds, mammals and fish. Many of the chemicals we ingest, such as pharmaceuticals, persist after being flushed down the toilet, with wastewater polluting rivers and oceans, or even the land when contaminated solid sewage sludge is used to fertilize crops.

Chemical persistence in the environment is a major thorny problem: Research has shown that polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) — highly toxic and carcinogenic substances banned by the U.S. as far back as 1977 and once widely used in coolants and oil paints — have continued building up in the blubber of killer whales (Orcinus orca), posing a genuine threat to a species that is already struggling in many parts of the world. So called “forever chemicals” — perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), that are highly toxic, carcinogenic and act like endocrine disruptors, are currently commonly used in disposable food packaging, cookware, cosmetics and even dental floss. A recent report also found them to be common in most of the drinking water in the U.S. They take hundreds or thousands of years to break down, but no U.S. limits have yet been placed on the concentration of forever chemicals in water.

“Even if we were to stop using and releasing [many novel entities], they would still be [here] for decades, or centuries, depending on what [substance] we’re talking about,” Carney Almroth said, adding that the risk of residual impacts from novel entities makes it even more imperative to stop, or at least slow down, the release of these substances.

The new paper in Science and Technology takes a specific look at plastics, which have become ever-present in daily life as food packaging, kitchenware and appliances. In recent years, much attention has been paid to the trillions of microplastics — fragments smaller than 5 millimeters, or three-sixteenths of an inch — polluting the global oceans, and the potential for larger plastic pieces to entangle or choke wildlife. New research shows that the sea breeze can even propel microplastics into the atmosphere, contaminating the very air we breathe and impacting climate change.

Plastic is highly problematic since it’s made out of a cocktail of chemicals that can leach out dangerous substances, especially when heated, cooled or scratched. A chemical compound known as bisphenol A (BPA) has been shown to act as an endocrine disruptor and interfere with hormones, impact immune systems and even promote certain cancers. One study even found that BPA can be absorbed into the human body through mere skin contact. But it’s not just BPA that’s harmful — many BPA alternatives have been found to be equally a risk to human health.

“We have been told for many, many decades that [plastics are] inert, and that they don’t release chemicals to their surroundings,” Villarrubia-Gómez said. “More and more, we’re discovering that that’s not true. Plastic leaches other chemicals … and we are in contact with [plastic] the whole day.”

Plastic isn’t just a problem in its end state. To make plastic, which uses petroleum as its base, greenhouse gases like ethane and methane need to be fracked from the ground and “cracked” into new compounds, the precursors to plastics. These industrial processes can release a number of toxic chemicals, along with various greenhouse gases, into the environment. The production of plastics is also intimately tied to the fossil fuel industry; as demand for oil drops, the petrochemical industry is ramping up its production of plastics.

“They see plastics as their next piggy bank,” Carney Almroth said. “Simultaneously, there’s a big push for an increase in plastics production and plastic use and plastic sales.”

Beeler said the release of novel entities into the environment poses a similar risk as climate change. “They’re both existential threats to humanity,” he noted. “Climate change [will determine] where you can live and how you can have a livelihood. Chemicals actually just remove your health — it’s very, very direct and personal. So I would draw them [as being at] the same crisis levels. It’s just that we’re not that socially conscious of chemicals and chemical safety, as we are of climate now.”

Determining a chemical’s risk often takes many years of methodical research, as scientists trace the causal connections between a synthetic substance and resulting environmental and health impacts. By then, that substance will often be ubiquitous, used in products across society.

‘Uptick in awareness’

While change is urgently needed to mitigate the impacts of novel entities, Carney Almroth said such an industrial paradigm shift would require a “massive overhaul of systemic societal structures.”

Industries that produce novel entities are “supported by the fact that we require constant economic growth,” she said. “This is one of the ways that they’ve been able to keep producing and using chemicals, even in the face of toxicity data, because they can show that it can grow economies, provide jobs, provide materials and so on and so forth.”

Despite the enormity of the problem, there may be opportunities for change in the near future. For instance, there are calls to form an international panel on chemical pollution, similar to those institutions focused on biodiversity and climate, such as the IUCN or the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In February and March, the U.N. Environment Assembly (UNEA) will also be meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, to discuss a number of environmental issues, including whether to mandate a new global treaty on plastics.

Beeler said that while negotiations may swing in the direction of only treating plastic as a waste issue, there are calls to address the entire plastic life cycle, taking into account all of the chemicals and pollutants plastic releases into the environment from production to waste stream.

He also said there’s also a reason for optimism in the way heightened public interest in plastic pollution has helped raise awareness of the larger problem of synthetic chemical contaminants.

“There’s been a small uptick in awareness [of] the harm from chemicals … due to the affiliation and link to plastics,” he said. “But prior to plastics, it was really [an awareness] desert — and plastics have created a little oasis of growing consciousness.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611