Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

But new information that emerged this week in the Sept. 11 case undermines that FBI narrative. The two intelligence agencies secretly arranged for nine FBI agents to temporarily become CIA operatives in the overseas prison network where the spy agency used torture to interrogate its prisoners.

The once-secret program came to light in pretrial proceedings in the death penalty case. The proceedings are examining whether the accused mastermind of the Sept. 11 plot, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and his four co-defendants voluntarily confessed after years in the black site network, where detainees were waterboarded, beaten, deprived of sleep and isolated to train them to comply with their captors’ wishes.

At issue is whether the military judge will exclude from the eventual trial the testimony of FBI agents who questioned the defendants in 2007 at Guantánamo and also forbid the use of reports that the agents wrote about each man’s account of his role in the hijacking conspiracy.

A veteran Guantánamo prosecutor, Jeffrey D. Groharing, has called the FBI interrogations “the most critical evidence in this case.” Defense lawyers argue that the interrogations were tainted by the years of torture by U.S. government agents.

In open court Thursday, another prosecutor, Clayton G. Trivett Jr., confirmed the unusual arrangement, in which nine agents were "formally detailed" to the agency “and thus became a member of the CIA and worked within CIA channels.”

He said that the agents served as “debriefers,” a CIA term for interrogators, and questioned black site prisoners “out of the coercive environment” and after the use of “EITs.”

EITs, or enhanced interrogation techniques, is a CIA euphemism for a series of abusive tactics that the agency used against Mohammed and other prisoners in 2002 and 2003 — tactics that were then approved but are now illegal. They include waterboarding, painful shackling and isolating a prisoner nude, shivering and in the dark to break his will to resist interrogation.

Trivett offered no precise time period but made clear that the FBI agents were absorbed by the CIA sometime between 2002, when the black sites were established, and September 2006. On their return to the FBI, they took on the status of CIA assets, he said, and so their identities are classified.

Five of the nine agents had roles in the interrogations of some of the defendants in the case, Trivett said, and their names have been provided to defense lawyers on the basis that they not be disclosed.

The FBI declined to comment on the arrangement, as did the CIA.

A defense lawyer, James G. Connell III, added more details in the same court hearing.

He said that the nine agents “stopped being FBI agents and became CIA agents temporarily” under a memorandum of understanding that established a different arrangement than the more typical assignment of a representative of one law enforcement agency to work out of the organization of another.

A former CIA historian, Nicholas Dujmovic, said there was a precedent for “taking employees from another government agency and quickly making them CIA employees for specific functions.”

In the 1950s, the CIA transformed U.S. Air Force pilots into CIA employees during their stints flying U-2 spy planes and then returned them to the Air Force without the loss of seniority or benefits. “President Eisenhower thought it was important that U-2s not be piloted by U.S. military pilots,” Dujmovic said. The process was called “sheep dipping,” he said.

Earlier testimony showed the FBI participating remotely in the CIA interrogations through requests sent by cables to the black sites seeking certain information from specific detainees, including Mohammed after he was waterboarded 183 times to force him to talk.

The pretrial hearings are in their ninth year and the military judge, Col. Matthew N. McCall of the Air Force, is the fourth judge to hear testimony at Guantánamo. In arguing over potential trial evidence, the prisoners’ lawyers have repeatedly accused prosecutors of redacting information that the defense needs to prepare for the capital trial. In the military commissions, prosecutors are the gatekeepers of potential trial evidence and can withhold information they deem not relevant to the defense’s needs.

In one example, Connell showed the judge a November 2005 cable the FBI sent to the CIA that contained questions for three of the defendants while they were in a black site — out of reach of the courts, lawyers and the International Red Cross.

The FBI released the cable to the public this month under an executive order by President Joe Biden to declassify information about the FBI investigation of the Sept. 11 attacks.

Connell had earlier received a version of the same cable from prosecutors. But it was so redacted that it obscured the fact that the FBI wanted Mohammed and the other defendants questioned in the black sites.

Trivett sought to play down the disclosure of the FBI-CIA collaboration as routine business at a time when the U.S. government was devoting tremendous resources to investigating the Sept. 11 attacks. “This is not some big bombshell,” he told the judge.

A lawyer for Mohammed, Denny LeBoeuf, cast the collaboration as part of a conspiracy to portray FBI accounts of interrogations of the defendants at Guantánamo in 2007 as “clean team statements,” a law enforcement expression.

“They were never clean,” LeBoeuf said. “Torture isn’t clean. It is filthy. It has sights and sounds and consequences.”

Production of Pfizer's experimental COVID-19 antiviral pills in Freiburg, Germany. (photo: AFP/Getty Images)

Production of Pfizer's experimental COVID-19 antiviral pills in Freiburg, Germany. (photo: AFP/Getty Images)

New antiviral drugs are startlingly effective against the coronavirus—if they’re taken in time.

The Emory researchers named their drug molnupiravir, after Mjölnir—the hammer of Thor. It turns out that this was not hyperbole. Last month, Merck and Ridgeback announced that molnupiravir could reduce by half the chances that a person infected by the coronavirus would need to be hospitalized. The drug was so overwhelmingly effective that an independent committee asked the researchers to stop their Phase III trial early—it would have been unethical to continue giving participants placebos. None of the nearly four hundred patients who received molnupiravir in the trial went on to die, and the drug had no major side effects. On November 4th, the U.K. became the first country to approve molnupiravir; many observers expect that an emergency-use authorization will come from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in December.

Oral antivirals like molnupiravir could transform the treatment of COVID-19, and of the pandemic more generally. Currently, treatments aimed at fighting COVID—mainly monoclonal antibodies and antiviral drugs like remdesivir—are given through infusion or injection, usually in clinics or hospitals. By the time people manage to arrange a visit, they are often too sick to receive much benefit. Molnupiravir, however, is a little orange pill. A person might wake up, feel unwell, get a rapid COVID test, and head to the pharmacy around the corner to pick up a pack. A full course, which needs to start within five days of the appearance of symptoms, consists of forty pills—four capsules taken twice a day, for five days. Merck is now testing whether molnupiravir can prevent not just hospitalization after infection but also infection after exposure. If that’s the case, then the drug might be taken prophylactically—you could get a prescription when someone in your household tests positive, even if you haven’t.

Molnupiravir is—and is likely to remain—effective against all the major coronavirus variants. In fact, at least in the lab, it works against any number of RNA viruses besides SARS-CoV-2, including Ebola, hepatitis C, R.S.V., and norovirus. Instead of targeting the coronavirus’s spike protein, as vaccine-generated antibodies do, molnupiravir attacks the virus’s basic replication machinery. The spike protein mutates over time, but the replication machinery is mostly set in stone, and compromising that would make it hard for the virus to evolve resistance. Once it’s inside the body, molnupiravir breaks down into a molecule called NHC. As my colleague Matthew Hutson explained, in a piece about antiviral drugs published last year, NHC is similar to cytosine, one of the four “bases” from which viral RNA is constructed; when the coronavirus’s RNA begins to copy itself, it slips into cytosine’s spot, in a kind of “Freaky Friday” swap. The molecule evades the virus’s genetic proofreading mechanisms and wreaks havoc, pairing with other bases, introducing a bevy of errors, and ultimately crashing the system.

A drug that’s so good at messing with viral RNA has led some to ask whether it messes with human DNA, too. (Merck’s trial excluded pregnant and breast-feeding women, and women of childbearing age had to be on contraceptives.) This is a long-standing concern about antiviral drugs that introduce genomic errors. A recent study suggests that molnupiravir, taken at high doses and for extended periods, can, in fact, introduce mutations into DNA. But, as the biochemist Derek Lowe noted, in a blog post for Science, these findings probably don’t apply directly to the real-world use of molnupiravir in COVID patients. The study was conducted in cells, not live animals or humans. The cells were exposed to the drug for more than a month; even at the highest doses, it caused fewer mutations than were created by a brief exposure to ultraviolet light. Meanwhile, Merck has run a battery of tests—both in the lab and in animal models—and found no evidence that molnupiravir causes problematic mutations at the dose and duration at which it will be prescribed.

With winter approaching, America is entering another precarious moment in the pandemic. Coronavirus cases have spiked in many European countries—including some with higher vaccination rates than the U.S.—and some American hospitals are already starting to buckle under the weight of a new wave. Nearly fifty thousand Americans are currently hospitalized with COVID-19. It seems like molnupiravir is arriving just when we need it.

It isn’t the only antiviral COVID pill, either. A day after the U.K. authorized Merck’s drug, Pfizer announced that its antiviral, Paxlovid, was also staggeringly effective at preventing the progression of COVID-19 in high-risk patients. The drug, when taken within three days of the onset of symptoms, reduced the risk of hospitalization by nearly ninety per cent. Only three of the nearly four hundred people who took Paxlovid were hospitalized, and no one died; in the placebo group, there were twenty-seven hospitalizations and seven deaths. Paxlovid is administered along with another antiviral medication called ritonavir, which slows the rate at which the former drug is broken down by the body. Like Merck, Pfizer is now examining whether Paxlovid can also be used to prevent infections after an exposure. Results are expected early in 2022. (It’s not yet known how much of a difference the drugs will make for vaccinated individuals suffering from breakthrough infections; Merck’s and Pfizer’s trials included only unvaccinated people with risk factors for severe disease, such as obesity, diabetes, or older age. Vaccinated individuals are already much less likely to be hospitalized or die of COVID-19.)

Paxlovid interrupts the virus’s replication not by messing with its genetic code but by disrupting the way its proteins are constructed. When a virus gets into our cells, its RNA is translated into proteins, which do the virus’s dirty work. But the proteins are first built as long strings called polypeptides; an enzyme called protease then slices them into the fragments from which proteins are assembled. If you can’t cut the plywood, you can’t build the table, and Paxlovid blunts the blade. Because they employ separate mechanisms to defeat the virus, Paxlovid and molnupiravir could, in theory, be taken together. Some viruses that lead to chronic infections, including H.I.V. and hepatitis C, are treated with drug cocktails to prevent them from evolving resistance against a single line of attack. This approach is less common with respiratory viruses, which don’t generally persist in the body for long periods. But combination antiviral therapy against the coronavirus could be a subject of study in the coming months, especially among immunocompromised patients, in whom the virus often lingers, allowing it the time and opportunity to generate mutations.

Merck will be producing a lot of molnupiravir. John McGrath, the company’s senior vice-president of manufacturing, told me that Merck began bolstering its manufacturing capacity long before the Phase III trial confirmed how well the drug worked. Normally, a company assesses demand for a product, then brings plants online slowly. For molnupiravir, Merck has already set up seventeen plants in eight countries across three continents. It now has the capacity to produce ten million courses of treatment by the end of this year, and at least another twenty million next year. It expects molnupiravir to generate five to seven billion dollars in revenue by the end of 2022.

How much will all these pills soften the looming winter surge? As has been true throughout the pandemic, the answer depends on many factors beyond their effectiveness. The F.D.A. could authorize molnupiravir within weeks, and Paxlovid soon afterward. But medications only work if they make their way into the body. Timing is critical. The drugs should be taken immediately after symptoms start—ideally, within three to five days. Whether people can benefit from them depends partly on the public-health infrastructure where they live. In Europe, rapid at-home COVID tests are widely available. Twenty months into the pandemic, this is not the case in much of the U.S., and many Americans also lack ready access to affordable testing labs that can process PCR results quickly.

Consider one likely scenario. On Monday, a man feels tired but thinks little of it. On Tuesday, he wakes up with a headache and, in the afternoon, develops a fever. He schedules a COVID test for the following morning. Two days later, he receives an e-mail informing him that he has tested positive. By now, it’s Friday afternoon. He calls his doctor’s office; someone picks up and asks the on-call physician to write a prescription. The man rushes to the pharmacy to get the drug within the five-day symptom-to-pill window. Envision how the week might have unfolded for someone who’s uninsured, elderly, isolated, homeless, or food insecure, or who doesn’t speak English. Taking full advantage of the new drugs will require vigilance, energy, and access.

Antivirals could be especially valuable in places like Africa, where only six per cent of the population is fully vaccinated. As they did with the vaccines, wealthy countries, including the U.S. and the U.K., have already locked in huge contracts for the pills; still, Merck has taken steps to expand access to the developing world. It recently granted royalty-free licenses to the Medicines Patent Pool, a U.N.-backed nonprofit, which will allow manufacturers to produce generic versions of the drug for more than a hundred low- and middle-income countries. (Pfizer has reached a similar agreement with the Patent Pool; the company also announced that it will forgo royalties for Paxlovid in low-income countries, both during and after the pandemic.) As a result, a full course of molnupiravir could cost as little as twenty dollars in developing countries, compared with around seven hundred in the U.S. “Our goal was to bring this product to high-, middle-, and low-income countries at fundamentally the same time,” Paul Schaper, Merck’s executive director of global pharmaceutical policy, told me. More than fifty companies around the world have already contacted the Patent Pool to obtain a sublicense to produce the drug, and the Gates Foundation has pledged a hundred and twenty million dollars to support generic-drug makers. Charles Gore, the Patent Pool’s executive director, recently said that, “for large parts of the world that have not got good vaccine coverage, this is really a godsend.” Of course, the same challenges of testing and distribution will apply everywhere.

Last spring, as a doctor caring for COVID patients, I was often dismayed by how little we had to offer. We tried hydroxychloroquine, blood thinners, and various oxygen-delivery devices and ventilator maneuvers; mostly, we watched as patients got better or got worse on their own. In the evenings, as I walked the city’s deserted streets, I often asked myself what kinds of treatment I wished we had. The best thing, I thought, would be a pill that people could take at home, shortly after infection, to halt the cascade of biological processes that sends them to the hospital, the I.C.U., or worse.

We will soon have not one but two such treatments. Outside of the vaccines, the new antiviral drugs are the most important pharmacologic advance of the pandemic. As the coronavirus becomes endemic, we’ll need additional tools to treat the inevitable infections that will continue to strike both vaccinated and unvaccinated people. These drugs will do that, reducing the damage that the coronavirus can inflict and, possibly, cordoning off avenues through which it can spread. Still, insuring that they are meaningfully and equitably used will require strength in the areas in which the U.S. has struggled: early and accessible testing; communication and coördination across health-care providers; fighting misinformation and building trust in rapid scientific advances. Just as vaccines don’t help without shots in arms, antivirals can’t work without pills in people.

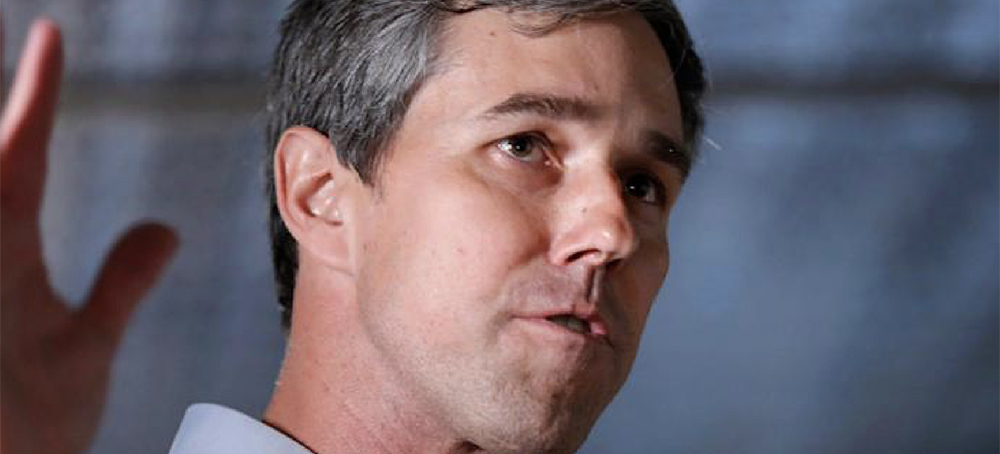

On the first day of his 2020 presidential campaign, O'Rourke was endorsed by 4 lawmakers not from his home-state. (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

On the first day of his 2020 presidential campaign, O'Rourke was endorsed by 4 lawmakers not from his home-state. (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

O'Rouke made the comment during a presidential debate in response to a question about advocating a mandatory assault-weapon buyback program, as Insider previously reported.

"If it's a weapon that was designed to kill people on a battlefield ... Hell yes, we're gonna take your AR-15, your AK-47," O'Rourke said during the presidential debate.

In an interview on CNN's "State of the Union" on Sunday, O'Rouke, who is running for Texas governor, doubled down on his stance: "I still hold this view."

"Look, we are a state that has a long, proud tradition of responsible gun ownership," he said."And most of us here in Texas do not want to see our friends, our family members, our neighbors shot up with these weapons of war."

O'Rourke said that some Texas residents have raised concerns about the permitless carry bill that state Gov. Greg Abbott signed in June, which the Dallas Morning News reported allows individuals 21 and over to carry a handgun without a license or training.

"We don't want extremism in our gun laws. We want to protect the Second Amendment, we want to protect the lives of our fellow Texans," O'Rourke said during the interview. "And I know when we come together and stop this divisive extremism that we see from Greg Abbott, we're going to be able to do that."

O'Rourke also responded to the acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse who was charged with shooting two men and injuring another with an AR-15 style rifle at a protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin, following the shooting of Jacob Blake last year.

During the trial, Rittenhouse argued that he was acting in self-defense. After his not guilty verdict, a gun rights organization said that it "will be awarding Kyle Rittenhouse with an AR-15 for his defense of gun rights in America."

"This entire tragedy makes the case that we should not allow our fellow Americans to own and use weapons that were originally designed for battlefield use," said O'Rourke. "That AR-15, that AK-47 has one single solitary purpose. And that is killing people as effectively, as efficiently, and as great of number in as little time as possible."

25 February 1975: The mayor of Chicago, Richard J Daley, is cheered by his number one fan, Mrs Daley (left), as he begins his victory speech at his campaign headquarters in downtown Chicago. (photo: Bettmann/Getty Images)

25 February 1975: The mayor of Chicago, Richard J Daley, is cheered by his number one fan, Mrs Daley (left), as he begins his victory speech at his campaign headquarters in downtown Chicago. (photo: Bettmann/Getty Images)

Cities have long been the sites of major advancement for progressive and socialist politics. But for over a century, city leaders have tried to halt those advancements with a potent tool: redistricting.

The advancement of democratic socialists and independent politics in cities, however, faces a looming threat: municipal redistricting.

Redistricting is often seen as a competition between Democrats and Republicans, and gerrymandering in city councils (where Democrats dominate) receives less attention. The data, however, paint a different picture. To explore the consequences of municipal redistricting for independent politics, my research team digitized and analyzed ward maps from the cities of Chicago, St. Louis, and Milwaukee from their founding in the 1800s to the present. We tracked the movement of wards within each city over time, paying attention to instances when wards were redistricted from one end of a city to another, as well as instances when wards never moved.

Our study’s findings are troubling for progressive elected officials. Municipal redistricting has been used by the Democratic Party to discipline and suppress elected officials advocating for racial and economic equality.

For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley teleported the 21st and 34th wards on the city’s white north side to the far south side, where the African American population was growing tremendously. This mattered because Chicago’s mayor can appoint individuals to complete the term of a city council member who either retires or dies. By moving a white city council member’s ward to a nearly all African American ward in the 1950s and 1960s, the mayor coerced the white incumbent city council member into midterm retirement. Consequently, Daley appointed his own handpicked African American city council members to complete their terms.

On the surface, this appeared to be a victory for racial equality in political representation. But a closer look at the historical record reveals that Daley’s appointed black elected officials opposed Martin Luther King Jr’s march on Chicago, opposed civil rights legislation, and unanimously supported the mayor’s economic development agendas. Historians refer to this group of black city council members, who remained largely silent on issues of civil rights and racial justice in the 1960s, as the “Silent Six.” Mayor Daley used municipal redistricting to undermine the growth of independent socialist black politics in Chicago.

Similar processes unfolded in St. Louis, where the city council used redistricting in 2001 to discipline alderwoman Sharon Tyus, who had been a thorn in the side of the mayor’s office for years. Tyus called out racially discriminatory hiring practices among city agencies, as well as the hypocrisy of the city’s proposals to fund a new sports stadium while neglecting St. Louis’s low-income black communities.

In 2001, St. Louis teleported Tyus’s Ward 20 from the north to the far southeast side of the city, effectively ending Tyus’s term in office. Although Tyus was disciplined out of St. Louis politics for nearly a decade, she came back by winning election in the 1st ward in 2010. Tyus holds office today, but African Americans are still underrepresented in St. Louis’s city council.

In Milwaukee, a city with a long history of socialist party representation, municipal redistricting was used to help preserve the city’s white-dominated and pro-corporate governing coalition. From 1910 to 1970, the Milwaukee Common Council contracted from having twenty-seven seats to having just fifteen due to population loss. In this same time period, Milwaukee fought hard to annex white and more affluent suburbs to increase its tax base.

In 1955, Milwaukee annexed the towns of Granville and Lake by offering multiple incentives. One was a promise to provide these towns with their own ward upon incorporation into the city, such that these white and more affluent communities could have greater say in city policy. To accomplish this, in 1956, Milwaukee teleported its 19th and 20th wards to the newly annexed neighborhoods of Lake and Granville. To this day, elected officials representing Lake and Granville continue to be a voice for moderate or conservative causes in Milwaukee.

Perhaps the most surprising discovery from our study was the fact that, in Chicago, many of the wards that have never moved for more than one hundred years are home to some of the city’s most white and affluent communities, as well as communities that have historically been home to police officers. This included neighborhoods such as the predominantly Irish Catholic Bridgeport and Beverly, as well as elite neighborhoods like the Gold Coast, Lakeview, and Lincoln Park.

One might argue that these Chicago communities had the most stable populations and that, therefore, their wards should have moved the least. Census data, however, revealed that the populations of these communities changed significantly over the decades. Thus, the stable location of these wards over time reflected conscious efforts to protect these predominantly white and affluent communities from gerrymandering.

Today, in Chicago, some in the media and city council have framed the upcoming ward redistricting debate as a battle to increase the total number of black, Latino, or Asian American representatives. History, however, suggests that more is at stake than the racial composition of the city council. Ward remaps have squashed the most progressive elected officials under the guise of “equal racial representation.” As cities begin ward redistricting, we can’t simply accept claims about the racial equity of proposed ward maps at face value. Those redrawn maps may have disastrous consequences for elected officials who have fought hardest against the status quo and for racial and economic justice.

'I blamed myself for a long time,' said one survivor. (photo: Getty Images)

'I blamed myself for a long time,' said one survivor. (photo: Getty Images)

“I blamed myself for a long time,” one survivor told VICE News. “I think a lot of that was because of the way that the school handled it.”

Then, in 2014, when she was 15 years old, Wombwell tried to report that she had been raped in the woods near her school, Myers Park School in Charlotte, North Carolina, by a classmate. And, in response, the school principal suggested that Wombwell could be suspended for having sex on campus if her account turned out to be untrue, according to interviews with Wombwell and a lawsuit she filed in 2019.

Wombwell didn’t pursue an investigation. “Nothing happened,” recalled Wombwell, now 22.

Wombwell is one of multiple women to say that they tried to report sexual assault to officials at Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, only to meet with indifference or even aggression. One woman, Serena Evans, said that after she was raped in a Myers Park bathroom in 2016, she, too, was threatened with suspension. Another former student told VICE News that she reported being raped to Myers Park officials in late 2014 and they seemed to believe her—but said that, essentially, there was next to nothing she or they could do about it. And yet another woman has anonymously filed a still-pending lawsuit against Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, in a case that sounds deeply similar to Wombwell’s.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools is now in the midst of yet another scandal over a school’s handling of sexual assault allegations. Earlier this month, a 15-year-old student at Hawthorne Academy of Health Sciences, another high school in the district, accused the school of suspending her after she reported a male classmate for sexual assault.

In addition to being suspended, the girl was told to take a weekend class called Sexual Harassment Is Preventable.

“Up until this point, when I thought about the fact that they threatened to suspend me if I did an investigation, I always sort of thought it was a threat to stop me from speaking out,” Wombwell said. “And so to see them actually suspending a student—I can’t help but see myself in her and wonder what would have happened to me if I had decided to go through with an investigation.”

Wombwell said that the rape, and the way the administration failed to really handle it, shaped the rest of her high school career. She couldn’t go to football games, she said, because her alleged rapist was in the marching band. When he showed up at prom, she got so upset she left early. She still struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I blamed myself for a long time,” she told VICE News. “I think a lot of that was because of the way that the school handled it.”

In late 2016, when Evans told a Myers Park administrator that, just days earlier, she’d been raped in a school bathroom, she felt like she was walking through a dream. In her shock and pain, the world had gone fuzzy.

But she says the administrator’s response still tore through that haze.

The administrator, Evans and her mother told VICE News in an interview, said that if her alleged rapist was found innocent, Evans would be suspended for having been in the boys’ bathroom. Evans’ mother, Kay Mayes, said that the administrator also warned them to keep quiet about what had happened.

Inside her head, Evans recalled screaming, “Why don’t you believe me?”

In emails to Myers Park administrators from the months after the alleged rape, Mayes pleaded for Evans’ alleged attacker to undergo counseling. But, by March 2017, Mayes had had enough.

“I no longer believe that you (the school, CMS) are going to give me any info and updates, nor do anything about the situation on Serena's behalf,” she wrote. “I am tired of waiting around for you all to reach back out.”

“CMS [Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools] cannot provide information about matters involving student discipline or specific cases in which there are ongoing investigations, pending or settled litigation, or otherwise involve confidential student or staff data,” a spokesperson for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools told VICE News in an email, in response to a detailed list of allegations in this story. “Likewise, CMS cannot provide information about specific personnel matters such as employee suspensions.”

“District and Board of Education leadership take allegations of sexual misconduct seriously,” the spokesperson added.

Evans, now 20, said that she did “everything right.”

“I was a star athlete. I never skipped class, never skipped school, I got good grades,” said Evans. “I had never been into the woods. I didn’t party, didn’t do drugs. I didn’t hook up with a bunch of people. This can still happen to people that literally do everything right. I think that’s what’s really hitting people now.”

Evans has not sued Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, and Wombwell settled her lawsuit after, she said, it became clear that real change would not come from the courts. (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools did not reply to a specific question about the settlement, but the Charlotte Ledger has previously reported that the settlement didn’t include an admission of wrongdoing on the district’s part.)

The other woman who has sued over sexual assault allegations at Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools is known in court documents only as “Jane Doe.” According to her ongoing lawsuit, Doe was a junior in 2015 when a male student pulled her into the woods near campus and sexually assaulted her.

When Doe emerged from the woods, “Doe appeared both distressed and disheveled. Her hair was in disarray, she had mud on her clothing, her glasses were broken, and there was semen on her shirt,” an amended version of the lawsuit’s complaint alleges. But even after Doe allegedly told a local school resource officer that she’d been sexually assaulted, two of the defendants in the lawsuit did not take “a statement from Ms. Doe or otherwise meaningfully investigate her complaint.”

Instead, per the lawsuit, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg officials accepted the alleged attacker’s claim that the encounter was consensual. “Furthermore, none of the defendants offered to transport Ms. Doe to a hospital or otherwise assist her in reporting the rape to local law enforcement.”

The school resource officer also allegedly “warned Ms. Doe that if she was not telling the truth about the sexual assault she could be charged with a crime”—an echo of the warning Wombwell said she’d received the year before. The officer denied this allegation in one legal filing.

In court papers, the defendants have broadly denied wrongdoing.

Administrators for the school said in those filings that they didn’t take a statement from Doe because her parents prohibited it; they also didn’t take her to the hospital, they said, “or otherwise assist her in reporting a rape to law enforcement because she did not report a rape at that time.” The school resource officer said that he filed a noncriminal police report of Doe’s account, which “reflects what she told him.” He also claimed that he didn’t go to the hospital because Doe’s mother wanted “a detective to come to interview her daughter.”

The case remains open. But Doe ended up leaving Myers Park, as well as her job at the local mall. According to the complaint, her fear of running into her alleged assailant, “given the lack of consequences for his sexual attack against her, has affected what jobs she takes, where she works, and what shifts she accepts.”

The mother of the student from Hawthorne Academy who reported being sexually assaulted, whom VICE News is not naming, said that her daughter is just trying to go to school like normal. But realizing that this isn’t the first time a Charlotte-Mecklenburg school has been accused of mishandling a sexual misconduct allegation has been extremely frustrating, she said.

“My daughter constantly questioned whether she had done the right thing or not. And I wanted her to know that she did,” the mother said. “And I wanted CMS [Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools] to be aware that these issues are still going on.”

Police had also investigated her daughter’s claims and the male classmate had confessed to the cops, the student’s mother told VICE News. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department didn’t return a VICE News request for charges connected to the case, but local news outlet WBTV reported that a minor was charged with sexual battery in connection to the report.

Hawthorne Academy, however, found that there was no evidence that the district’s sexual harassment policy had been violated, per a document provided to VICE News. Instead, the school found that there was “evidence of a violation” of a rule against falsifying information.

The mother said that Hawthorne Academy Assistant Principal Nina Adams basically told her, “What the police investigation concludes had nothing to do with the school investigation. We didn’t find anything. We have to dismiss the case.”

Her daughter’s suspension has been put on hold, the mother said. Days after WBTV shared their accounts, the outlet reported that another Hawthorne Academy student had also been urged to stay quiet about being sexually assaulted. The student said that the school claimed to have looked at video footage of the location where the incident allegedly occurred and said they didn’t find anything.

Adams didn’t reply to a VICE News request for comment.

After WBTV reported on Wombwell and Doe’s stories in June, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education posted a statement to Facebook about the cases.

“No matter what we say or how we say it, it will sound to some as if we are making excuses,” the statement read, adding that the WBTV story “contained numerous misstatements of fact that compel us to correct the record.” For example: “Neither case was rape.”

When it comes to Wombwell, publicly known as Jill Roe at the time, the statement asserted that the then–Myers Park principal didn’t learn about her claims until two months after the alleged incident.

“He immediately investigated the incident, including meeting with Ms. Roe and her parents. After that meeting, measures were put in place to keep the students separated,” the statement read. “Neither Ms. Roe or her parents voiced disagreement over those measures or took any further action—they did not contact the learning community superintendent; they did not contact the superintendent; and they did not contact board members. Instead, Roe filed a lawsuit five years later.”

The statement was soon deleted.

“It landed in such a way that it sounded like ‘Don’t trust victims,’ and that was a terrible message, so that’s why it was taken down,” said Elyse Dashew, chair and at-large representative for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. She said she did not write the statement. “That was not the message that was intended.”

In July, school board members were set to meet with survivors and experts to address the burgeoning crisis over sexual assault at Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. But after Wombwell asked to attend, the meeting was cancelled entirely. In an email obtained by VICE News, a board member said that they “should not meet with individuals that have potential or past claims against the district.” (By that point, Wombwell had already settled her lawsuit against the district.)

Wombwell and Evans have now launched a group, Amplify Survivors, that’s meant to support people who were sexually assaulted, and they’re continuing to call for further accountability from Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. A Change.org petition about Wombwell’s case has garnered more than 75,000 signatures. But despite their efforts, Wombwell and her fellow advocates say they’ve seen little change.

In early October, more than 100 students walked out of another school in the district, Olympic High School, after a football player was allowed to keep playing for the school team despite the fact that he’d been recently charged with a felony sex crime. Another student had also been recently charged with raping a girl at Olympic High School.

Afterward, two players on the volleyball team said they were suspended for one game for participating in the walkout, which the school’s athletic director described as an “unapproved protest.” (That director didn’t reply to a VICE News request for comment.)

“Honestly, I’m just disgusted that they let a football player who has sexual assault allegations against him play with an ankle monitor,” one suspended player told the Charlotte Observer. “But because I speak out for feeling unsafe, I get punished and not allowed to play in a game.”

"Even after all of this advocacy work to try and get CMS' attention and to stop these things from happening, the Olympic case happened after we'd been protesting for months. The new Hawthorne case happened after we'd been protesting for months,” Wombwell said. “For these things to still be happening, even under this amount of public pressure, it's really disheartening.”

A current student at a Charlotte-Mecklenburg school said that at a recent meeting with school officials, administrators warned them that posting on social media about sexual assault allegations in the district could imperil the student’s ability to go to college.

Informed of the student’s allegation, Dashew sounded confused.

“What?” she said. “I would ask the student to share that concern with a school board member, so that we can address it … That, yep, definitely raises some questions.”

Dashew declined to answer multiple questions about specific allegations against Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. She was, she said, constrained by confidentiality concerns.

“It’s really, really frustrating that we can’t speak to the specifics of certain issues,” Dashew said. “Also, with things like student suspensions, we don’t actually administer those suspensions, and so oftentimes we don’t necessarily know about them unless it comes to us in an appeal. And so that’s why we’ve been really, really cautious about speaking out.”

Still, in the wake of the reports, district Superintendent Earnest Winston assembled a task force to review the district’s policies around Title IX, the landmark civil rights law that protects against sex-based discrimination. When Aidan Finnell, a 16-year-old student at Myers Park, joined the group, she was initially optimistic. But Finnell said that, now, she’s not confident that its suggestions will be implemented.

“There was a really big emphasis on how things needed to be kept hush-hush and secret,” she said of the task force. “It just turned more into students saying the same things over and over again, in a room full of adults, and being told that most of what we were saying wasn’t possible or that we’d said it before.”

One adult at the task force meetings also suggested that news reports of sexual misconduct at the district could not be trusted, Finnell said.

“The superintendent anticipates a report from his Title IX task force in the next few weeks,” a Charlotte-Mecklenburg spokesperson told VICE News in an email. “He will review the report and plans to enact reforms as appropriate.”

Since the news about Hawthorne broke, the school’s principal and assistant principal have been suspended, with pay; officials did not give a reason for the suspensions. But that’s also what happened to the principal who ran Myers Park High School at the time of Wombwell, Evans, and Doe’s allegations—before he was moved to another job with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools.

He makes the same six-figure salary.

“We’re literally talking to a brick wall,” Evans said. “It’s not just a Charlotte thing. It’s not just a CMS thing. It is a national issue.”

People gather during the distribution of humanitarian aid among refugees near the transport and logistics centre Bruzgi on the Belarusian-Polish border in the Grodno region, Belarus November 21. (photo: Maxim Guchek/BelTA/Reuters)

People gather during the distribution of humanitarian aid among refugees near the transport and logistics centre Bruzgi on the Belarusian-Polish border in the Grodno region, Belarus November 21. (photo: Maxim Guchek/BelTA/Reuters)

Women refugees say they have miscarried, been separated from their children by border guards, and been hospitalised.

“Me and my son survived only by miracle,” Shirin told Al Jazeera from a hospital in a Polish border town, a day after she was loaded into an ambulance.

Her body was covered in injuries and blisters from the cold.

“I will never forget what I have seen in the woods,” she said. “I have seen so many children and babies there. Their mothers were screaming and praying for a miracle. The adults could barely survive, so what chance do babies have?

“These images will be haunting me until I die.”

Shirin fled the Kurdish region of Iraq with Ali, her only child, and her husband Afran* on October 22.

But when Belarusian police saw them attempting to cross the border into Poland, they intervened and pushed Afran back deeper into Belarus, according to her testimony.

Shirin crossed the border alone and spent 21 days in the woods with Ali.

“My son was crying: ‘Please, my father, please, my father,’ but we didn’t know if he was alive or dead. We ended up alone, freezing, with no food.”

Shirin cried and shook as she told Al Jazeera her story. Both her legs and one arm were bandaged. She was unable to walk.

She still does not know where her husband is.

‘I don’t know where she is’

Thousands of women and children have made attempts to reach the European Union by entering Poland in recent weeks, as a migration crisis that began in August escalates.

Crowds of people are now stranded between the border that separates Belarus and Poland. They travelled to Minsk, the Belarusian capital, on a promise that they would be able to breach the fence and enter the EU country.

Poland and its Western allies say Belarus encouraged people, mostly from the Middle East, to the country in an attempt to push them towards the border and destabilise Europe – an act of revenge for Western sanctions on the administration of President Alexander Lukashenko.

There is no official data about the numbers of people at the Belarus-Poland border, but Agnieszka Kosowicz, head of the Polish Migration Forum, an NGO supporting refugees and migrants in Poland, told Al Jazeera that “2,666 women have applied for asylum in Poland this year alone, out of a total of 6,697″.

She said while women’s stories are covered less often by the media than those of men, women represent a significant percentage of the migrating population.

“We know for sure that women are present at the border based on local volunteers’ everyday testimonies.

“Volunteers talk about women so weak they cannot walk or attend to their children, about women who cry over their children who are hungry, and women who mourn lost babies – children they lost as a result of miscarriage, or literally lost their children while walking in the forest at night,” she said.

Azin Govand*, a 27-year-old asylum seeker from the Iraqi Kurdish region who is now in Minsk, has not seen her three-year-old daughter Shewa* or her husband since Belarusian authorities allegedly separated the family at the border.

At the same time, Azin said the authorities pushed her back into Belarus.

“I haven’t heard from my husband and daughter for more than seven days,” Azin told Al Jazeera by phone, from a Belarusian number.

“I recently saw a picture of a baby girl dressed in the same clothes as my daughter on social media. The girl was lying on the floor near the border, face down,” she said. “It could have been my daughter. I don’t know where she is.”

Kosowicz said several families have been split up at the border or become separated in the forests.

This includes, for example, when a parent is taken to hospital while the children are left in the forests, or people getting lost, or as people are pushed back by border officials on both sides of the frontier.

Amid the chaos, cases of miscarriage have been documented. Other women have been found with young babies with severe medical problems.

A one-year-old Syrian baby boy is believed to be the youngest victim of the refugee crisis at the border. The cause of his reported death has not yet been established.

Nazanin*, an Iraqi Kurdish woman who was recently rescued from the Polish woodlands near the Belarus border after having spent a month there, told Al Jazeera that “only God saved her [seven-month-old] baby from dying.”

She and her husband had fled Zakho, a region near the border with Turkey and Syria, because they were exposed to shooting and shelling.

“The baby was freezing,” Nazanin said. “She was crying because of the cold every night.

“We only had a T-shirt and one sweater for the baby, no other clothes, and no nappies,” she said.

“We were told the journey would be short, and ran out of food quickly. We haven’t eaten for 10 days, and walked seven or eight kilometres (four to five miles) without shoes,” she said, pointing to her frostbitten feet.

“During all that time, we had to drink dirty water given to us by Belarusian guards, or water that we found in the swamps. We were all sick.”

‘Horrific’ scene

Karol Wilczynski, director of the Salam Lab NGO working against Islamophobia in Poland, who has been helping the stranded refugees, told Al Jazeera that he has seen several women and babies in need.

“The most horrific and moving scene I have ever witnessed was that of a 49-year old grandmother with her two-year-old granddaughter,” Wilczynski said. “When we found them, the grandmother was unconscious and had severe hypothermia – only 34 degrees (93.2F) of body temperature. By some miracle, the baby survived.”

He said an emergency services operator refused to send an ambulance and threatened to call border guards “to deal with the refugees”.

“We then called Border Aid, a group of paramedic volunteers, who said the grandmother would have died if she had stayed there any longer. I cannot imagine what would have happened to the baby,” Wilczynski said.

He has been volunteering with Grupa Granica, an umbrella organisation providing aid at the border which supported 1,000 people from November 8 to 12.

“Out of the 1,000 people, 10 percent were children, and more than 25 percent were women,” he said. “Out of the remaining 65 percent of men, a huge part were vulnerable.”

Sarkawt*, 36, spent about a month in the woods, with his wife Nazdar* and their three children aged six, eight, and nine.

The cold and lack of drinkable water hit Nazdar, who collapsed and was hospitalised.

The children suffered frostbite.

“Even though we don’t know what will happen to [Nazdar], I thank God every day for saving all three of my babies,” Sarkawt told Al Jazeera.

“In the woods, I took my jacket off and put it on my babies. Sometimes, I tried to make a fire, but sometimes, it was too swampy, and I couldn’t,” he said.

“In the woods, we saw many women and children,” he said. “On the Belarusian side, the guards would sell us food and water but would ask for astronomical prices. They would sell us a bottle of water or one biscuit for the children for $50 because they knew the mothers would pay,” he said.

Kosowicz said she is in contact with one woman who delivered premature twins after crossing into Poland.

“I also remember women who could not take a few steps away from the group to urinate, and women who had their periods and could not attend to their basic hygienic needs in privacy,” she said.

“Each time we hear a new story, it is dramatic.”

An oil sands mine in Alberta, Canada adjacent to boreal forest outside of Fort McMurray. (photo: Michael Kodas/Inside Climate News)

An oil sands mine in Alberta, Canada adjacent to boreal forest outside of Fort McMurray. (photo: Michael Kodas/Inside Climate News)

Oil companies have replaced Indigenous people’s traditional lands with mines that cover an area bigger than New York City, stripping away boreal forest and wetlands and rerouting waterways.

She and her family would pass the mine in their boat when they traveled up the Athabasca River, and the fumes from its processing plant would sting their eyes and burn their throats, despite the wet cloths their mother would drape over the children’s faces.

By the time L’Hommecourt was in her 30s, oil companies had leased most of the land where she and her mother went to gather berries from the forest on long summer days or hunt moose when the leaves turned yellow and the air crisp.

Today, that same land, near her Indigenous community of Fort McKay, is surrounded by mines that have swallowed an area larger than New York City, stripping away boreal forest and muskeg and rerouting waterways.

Oil and gas companies like ExxonMobil and the Canadian giant Suncor have transformed Alberta’s tar sands—also called oil sands—into one of the world’s largest industrial developments. They have built sprawling waste ponds that leach heavy metals into groundwater, and processing plants that spew nitrogen and sulfur oxides into the air, sending a sour stench for miles.

The sands pump out more than 3 million barrels of oil per day, helping make Canada the world’s fourth-largest oil producer and the top exporter of crude to the United States. Their economic benefits are significant: Oil is the nation’s top export, and the mining and energy sector as a whole accounts for nearly a quarter of Alberta’s provincial economy. But the companies’ energy-hungry extraction has also made the oil and gas sector Canada’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. And despite the extreme environmental costs, and the growing need for countries to shift away from fossil fuels, the mines continue to expand, digging up nearly 500 Olympic swimming pools-worth of earth every day.

COP26, the global climate conference in Glasgow earlier this month, highlighted the persistent gap between what countries say they will do to cut emissions and what is actually needed to avoid dangerous warming.

Scientists say oil production must begin falling immediately. Canada’s tar sands are among the most climate-polluting sources of oil, and so are an obvious place to begin winding down. The largest oil sands companies have pledged to reduce their emissions, saying they will rely largely on government-subsidized carbon capture projects.

Yet oil companies and the government expect output will climb well into the 2030s. Even a new proposal by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to cap emissions in the oil sector does not include any plan to lower production.

Some lawyers and advocates have pointed to the tar sands as a prime example of the widespread environmental destruction they call “ecocide.” They are pushing for the International Criminal Court to outlaw ecocide as a crime, on a par with genocide or war crimes. While the campaign for a new international law is likely to last years, with no assurance it will succeed, it has drawn attention to the inability of countries’ existing laws to contain industrial development like the tar sands, which will pollute the land for decades or centuries.

Julie King, an Exxon spokeswoman, said that “ExxonMobil is committed to operating our businesses in a responsible and sustainable manner, working to minimize environmental impacts and supporting the communities where we live and work.”

Leithan Slade, a spokesman for Suncor, pointed to agreements the company has signed with First Nations, adding that “Suncor sees partnering with Indigenous communities as foundational to successful energy development.”

Despite those agreements, the mines’ ecological impacts are so vast and so deep that L’Hommecourt and other Indigenous people here say the industry has challenged their very existence, even as it has provided jobs and revenue to Native businesses and communities.

“The basis of all our Indigenous culture is on the land,” said L’Hommecourt, 58.

It was the threat to her mother’s traditional land that 20 years ago set her on a path of resistance. She attended a hearing for a mine that was slated to consume much of that land, and she spoke out angrily about the development. She ended up being recruited to work as an environmental coordinator for the Fort McKay First Nation, the Indigenous group of which she is a member, to help protect whatever shreds of land she could.

“That’s when I made my choice,” she said. “I’m going to fight for my mom’s land.”

Vast Black Holes

The only way to fully appreciate the scope of the tar sands is to see the mines from the air. Flying across the region from the north, the twisting channels of the Peace-Athabasca Delta, one of the world’s largest inland deltas, dominate the landscape, snaking through forest and marshlands with not a road or power line in sight.

That terrain gives way to a mixture of forest, muskeg and drylands, where the sandy soil rises to the surface. Out of nowhere, straight lines emerge—a wide, unpaved highway and paths leading to squares carved out of the forest, where companies have explored for oil.

Then the mines come into view. Billowing plumes of smoke fill the sky. Flames shoot out of flare stacks. The forest’s green is replaced by vast black holes pockmarked with giant puddles. From the air, the dump trucks and shovels look like toys, lines of Tonkas digging in oversized sandboxes. The mines are terraced, with massive berms holding back lagoons full of waste above the newly dug pits. As the plane nears its descent, the cabin fills with a tarry stench.

“It’s just the most completely ludicrous approach to industrial and energy development that is possible, given everything we know about the impact on ecosystems, the impact on climate,” said Dale Marshall, national program manager with Environmental Defence, a Canadian advocacy group.

To extract bitumen from the sand, oil companies heat it and then treat it in a slurry of water and solvents. In other parts of Alberta, where the sands are too deep to mine, the bitumen is melted in place and extracted through wells by pumping high-pressure steam underground. These deeper deposits cover a much larger area than the mines, more than 50,000 square miles.

The extraction requires enormous amounts of energy: In 2018, the latest year for which figures are available, oil sands producers consumed 30 percent of all the natural gas burned in Canada. Collectively, the mines’ and deep-extraction projects emit greenhouse gas emissions roughly equal those of 21 coal-fired power plants, and that’s just to get the crude out of the ground.

The operations also pump out noxious air pollutants, including nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, traces of which have been detected by scientists in soils and snowpack dozens of miles away.

The mines guzzle vast quantities of water, with nearly 58 billion gallons drawn from the region’s rivers, lakes and aquifers in 2019, according to government figures. When all that water comes out the other end, it is so heavily laced with hydrocarbons, naphthenic acids and carcinogenic heavy metals that it cannot be released where it came from. Instead, oil companies have been collecting these acutely toxic “tailings” in waste ponds, some of which routinely leak their contents into groundwater.

In 1973, a report to the Alberta Department of the Environment identified waste as a problem and recommended placing limits on the ponds’ size and duration of use. The idea was that the toxic components would settle out of the water over a matter of years. The reality is that the tailings will take decades or even centuries to separate naturally.

As a result, the ponds have grown exponentially in size and now cover more than 100 square miles. Every day, they swell with millions of gallons of new toxic waste. Regulatory filings show that the ponds are expected to continue to expand well into the 2030s. While companies are required by law to eventually reclaim them, only a fraction have been reclaimed so far.

Next to one pond, a coal-black mountain of debris towers over the water. High voltage lines buzz overhead. Air cannons ring the pond and blast several times each minute, creating a constant explosive din. Industrial iron scarecrows are dressed with safety vests and helmets. The noise and display are meant to scare off the millions of migratory birds that arrive in northern Alberta each year, exhausted from their annual odysseys.

Sometimes even these defenses fail or the birds ignore them and land anyway—tens of thousands each year, according to a 2016 report to provincial regulators, obtained this year by The Narwhal, a nonprofit Canadian news organization.

Ottilie Coldbeck, a spokeswoman for the Alberta Energy Regulator, which oversees the industry, said the research in the report “was not considered complete.”

Some conservationists worry that endangered whooping cranes, which migrate here annually, might land in a pond, and since fewer than 900 remain, the landing of a single flock could decimate the species in one errant swoop.

An Insatiable Appetite for Oil

White explorers and traders set their sights on the tar sands as soon as they arrived. In 1789, Sir Alexander Mackenzie reported seeing veins of “bituminous quality” exposed along the Athabasca River. Within a century, prospectors and geologists had identified “almost inexhaustible supplies” of petroleum in the area. The only obstacle seemed to be the people living above it.

In 1891, the superintendent general of Indian Affairs recommended drafting a treaty, “with a view to the extinguishment of the Indians’ title,” to open access to petroleum and other minerals. When a team was sent up the Athabasca eight years later to sign what would become Treaty 8, a member of the party named Charles Mair described giant escarpments rising on either side, “everywhere streaked with oozing tar, and smelling like an old ship.”

The Indigenous people used the substance to seal canoes and even burned it like coal, but Mair saw something different. “That this region is stored with a substance of great economic value is beyond all doubt,” he wrote. “When the hour of development comes, it will, I believe, prove to be one of the wonders of Northern Canada.”

But it would be many years before that hour struck, and the tar sands remained largely beyond reach until Americans, driven by nationalistic ambitions, invested vast sums of capital. In 1967, J. Howard Pew, of the Sun Oil Company, opened the first commercial mine, declaring, “No nation can long be secure in this atomic age unless it be amply supplied with petroleum.” A decade later, a second mine opened, called Syncrude, backed by a consortium of American oil companies and the Canadian government.

For years, there were only two mines, but the 21st century brought an insatiable global appetite for oil and fears that conventional sources of crude were running out. Oil prices surged, and Alberta’s massive pool of bitumen offered an opportunity to oil companies: No risky exploration was required, and unlike in other parts of the globe, Canada provided a stable, business-friendly government. Multinational giants poured in cash, boosted their reserves and drew tens of billions of dollars in new investment.

Over the course of only a decade the mines began to multiply. Eight active tar sands mines now form a 40-mile chain along the Athabasca River, their giant shovels gobbling up the earth like an invasion of mechanical caterpillars.

The town of Fort McKay, population 765, sits in the middle of all this. Even as the mines devoured the land, most of the people who lived here hung on as well as they could, squeezed into smaller and smaller spaces.

L’Hommecourt keeps a cabin 20 miles outside of Fort McKay as the crow flies, but more than an hour’s drive, because the road has to loop between and around several mines and two deeper extraction projects.

Despite L’Hommecourt’s best efforts as an environmental coordinator, the mines have continued to encroach on her cabin, which sits on the land where she used to go with her mother. More and more workers have showed up in the area, stopping her along the road to tell her that she couldn’t hunt moose or that she was trespassing.

“‘You’re the trespasser,’” she tells them. “‘I shouldn’t have to be answering your questions, you answer mine. That’s my attitude.”

The land, she said, is where she can think in her language, Dene, “where in the outside world it’s all English.”

“You get that sense of belonging here,” she said, “and that’s what I want for our peoples, to have their land back.” She added, “If you have your land back, you have everything.”

A Devil’s Bargain

When Pew’s Great Canadian Oil Sands mine opened in 1967, the people of Fort McKay were not happy, said Jim Boucher, who led the First Nation as chief for three decades until 2019.

Sun Oil, now Suncor, took over an important summer hunting and gathering ground called Tar Island, he said. “There was no discussion, no consultation.”

The Fort McKay First Nation includes both Dene and Cree—the two main Indigenous groups that have lived in the region for centuries. For most of the 20th century, the fur trade provided the nation’s members with one of their few sources of income. But it collapsed just as the oil industry was taking hold, and they had few alternatives but to turn to the oil companies and their rapidly expanding mines.

“We had no choice,” Boucher said.

After becoming chief in 1986, Boucher formed the Fort McKay Group of Companies to work with the oil industry, and over the following decades he oversaw partnerships with energy companies that would eventually net hundreds of millions of dollars for the community.

Now the oil sands are the axis around which Fort McKay revolves. The industry has allowed the community to build subsidized housing and to pay for education and elder care, achievements that Boucher rattles off proudly. Enrolled members receive quarterly dividends, and some, including Boucher, have grown relatively wealthy.

Many First Nations have also fought development. Several have filed lawsuits against companies or regulators—The Beaver Lake Cree Nation, south of Fort McMurray, sued the federal and provincial governments in 2008, saying its treaty rights had been violated by the cumulative effects of development. Despite receiving a favorable ruling five years later, the case is still awaiting trial, with a court date scheduled for 2024.

Attempting to block development can be prohibitively expensive, though, and is usually unsuccessful.

“It’s David and Goliath here, we’re dealing with multi-billion dollar companies,” said Melody Lepine, director of government and industry relations for the Mikisew Cree First Nation. The regulatory process, she said, is built to approve the companies’ projects, even if it takes years. “It’s very, very difficult to get anybody to say, ‘No, you’re not going to get approved.’”

Each of the area’s First Nations has signed “impact benefit agreements” with the oil companies that can include limits on certain practices, like water withdrawals, quotas for hiring Indigenous people and direct payments to the nations. But even as the impact agreements have secured benefits for the First Nations, they’ve created a Devil’s bargain, deepening reliance on an industry that is consuming the land that was once the base of the Indigenous economy and culture. The British sociologists Martin Crook, Damien Short and Nigel South have argued that the concept of “ecocide” offers a “powerful tool” to recognize the particular damage caused by resource extraction to many Indigenous groups, because of their cultural, spiritual and subsistence ties to ecosystems.

“They’re making us dependent on things that they make, things that they build,” L’Hommecourt said. “They want us to be dependent on those things so that we can give them our money, so we can give them our land and say, ‘Yeah, OK. I’ll trade it off.’”

L’Hommecourt, who is Boucher’s cousin, said she holds no resentment toward the former chief for tying their people’s fate to the industry.

“He did what he had to do, and as a chief I commend him,” L’Hommecourt said. “They call us the richest little First Nation in Canada.”

Boucher lost his grandfather’s cabin, where he learned to hunt and trap as a boy, to Syncrude’s mine. A cabin Boucher later built for his father, to the north, now sits on a postage stamp of land, he said, surrounded by newer mines.

“It’s empty, that’s how the cabin is to me,” Boucher said. “So I don’t go there anymore. No joy.”

‘They Took It All Away’

The mines cover a staggeringly large area, but their impact on the environment reaches even farther.

The town of Fort Chipewyan sits where the Peace and Athabasca rivers empty into Lake Athabasca, about 90 miles north of the closest mine, and the land here seems to offer a glimpse of what existed before the oil and gas companies arrived. There are no roads to the community, except for a frozen winter road that has become harder to maintain as temperatures warm. The mostly Indigenous residents can still hunt and trap in unbroken stretches of boreal forest, where wolves and wolverines prowl and towering spruce and jack pines shade a thick, spongy mat of lichen and moss below. The town abuts Canada’s largest national park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that is home to herds of wood bison and which the World Heritage Committee said in June was threatened by the expansion of the tar sands.

But while the nights are quiet and the air smells clean, the industry’s presence is strong even here. Kids zoom around town on ATVs, while the local supermarket displays boxes of 87” flatscreen TVs—”toys,” as some residents call them, that only those who work in the industry can afford to buy.

And despite its distance from the development, the flesh of the animals that drink from the lake is laced with some of the same compounds and heavy metals that collect in the waste ponds upstream.

When Alice Rigney, an elder with the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, was a young girl, the waste ponds had not yet been dug. Her family would head to their homestead in the delta ahead of the freeze and stay until Christmas. When the delta flooded in the spring, she said, the men would trap muskrats and the women would keep a fire going to dry the pelts and smoke the meat. Then came the spring bird hunt, flocks of thousands coming from the south.

But in the late 1960s, the lake levels dropped and the delta no longer flooded. A dam began to fill its reservoir up the Peace River, and the tar sands development began up the Athabasca. One day, she and her brother took a snowmobile out on the ice to go fishing for walleye, and then cooked their catch over an open fire, as always. But as the fish began to cook, black grease dripped out.

“The taste was gas or fuel,” Rigney said. They later learned that there had been an oil spill under the ice upstream, and the fishery had to be shut temporarily, she said.

People here have long suspected that the tar sands mines were poisoning the land and everything it feeds. Everyone seems to know someone who has died of cancer or another disease—Rigney survived breast cancer, which ran in her family, and her husband survived colon cancer. But in 2004, the appearance of a rare cancer brought increased attention.

Rigney was working as a physical therapist’s assistant at the health clinic one day when a doctor approached her for help arranging travel, saying a jaundiced patient needed to be flown to Fort McMurray for treatment. The man’s illness was soon diagnosed as an aggressive type of bile duct cancer called cholangiocarcinoma. He died shortly after.

Other people began to develop the cancer, of which only a few dozen cases are diagnosed each year in Canada. In 2010, a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found elevated levels of numerous “priority pollutants,” including mercury, lead, nickel and other heavy metals, in the river downstream of oil sands development, as well as in Lake Athabasca and in snow samples.

Three years later, another study in the same journal examined lake sediments surrounding Fort McMurray and found that levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, a group of chemicals that includes cancer-causing compounds, started rising in the 1960s and 1970s, when oil sands development began. The researchers found elevated levels in a lake dozens of miles from the mines.

The Athabasca Chipewyan and Mikisew Cree First Nations commissioned Stéphane McLachlan, an environmental scientist at the University of Manitoba, to test the tissues of animals, and in 2014 he released a report, finding elevated levels of toxic pollutants—including arsenic, mercury and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—in the flesh of moose, ducks and muskrats in the region. For the most part, the study found, community members were not exposed to levels high enough to affect their health, but that was only because many people had stopped eating as much wild game as they had before, out of fear that it was contaminated.

Although the study could not demonstrate that the cancers were caused by pollution from the mines, the researchers found that cancer rates in the community were correlated with working in the mines and with consuming larger quantities of traditional foods, particularly fish.

Provincial officials acknowledge that the mines’ waste ponds leak into groundwater. To “limit the risk” that this seepage will spread farther, the Alberta Energy Regulator requires companies to install drains, wells, sumps and underground walls to capture and contain the contamination, said Coldbeck, the agency spokeswoman.

Both federal and provincial officials have disputed research that has linked groundwater contamination to the waste ponds, citing other studies that indicate the compounds may be naturally occurring in groundwater because they are contained in bitumen.

But last year, the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, an environmental body created alongside the North American Free Trade Agreement, assessed all the published studies of water contamination and concluded that there was “scientifically valid evidence” that the waste ponds were leaching contaminants into groundwater. The analysis noted that some research has concluded that the contamination reached the Athabasca River, but that scientists were still debating the findings.

Asked about the report, Coldbeck said her agency “does not have any evidence to suggest” that contaminated groundwater has reached the Athabasca River. In response to a question about health concerns, she said that the agency “is committed to ensuring that Alberta’s oil sands are developed in a safe and responsible manner,” and referred questions to Alberta Health, the province’s public health agency.

A spokesperson for Alberta Health did not reply to multiple requests for comment.

A spokeswoman for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers declined to comment for this article, pointing instead to reports the group has issued on its engagement with Indigenous communities and on greenhouse gas emissions.

Meanwhile, surveys of cancer cases in Fort Chipewyan carried out in 2009 and 2014 came up with mixed results. Both showed higher than normal rates of certain cancers, including biliary tract cancers. One study determined that overall cancer rates were elevated. The other did not.

The most recent case of the bile duct cancer was diagnosed in 2017, when Rigney’s nephew fell ill. Warren Simpson battled the illness for two years, but died in November 2019.

Rigney blames the oil development for her nephew’s death and all the others, even as she acknowledges that there’s nothing to prove the connection. The way she views it, Simpson was just the latest piece of her life that industrial development took from her.

“The delta was such a vibrant place,” she said. “And they took it all away, I mean all.” She added, “What else is there to take?”

‘My Heart Is in the Boreal Forest’

The global oil industry is increasingly under assault, and Canada’s tar sands, because of the developments’ high greenhouse gas emissions, are a prime target of climate activists. Because new tar sands projects require billions of dollars invested up front, many financial analysts say the era of opening new mines is over.

But even if production from the mines holds steady or declines gradually their massive footprints are likely to expand for decades, because companies must continue to clear land to keep up production. For the people living here, it matters little whether land is destroyed by a new mine or an existing one.

When the mines do begin to decline, at some point in the future, the industry will face the challenge of what to do with the waste it has produced and how to pay for cleaning it up. The provincial government has secured $730 million from companies as collateral for a clean-up, but that would hardly even begin to cover the costs. While regulators’ official estimate of the current liability for Alberta’s mining industry is $27 billion, an internal report obtained in 2018 by Canadian journalists estimated clean-up costs of more than $100 billion. While that figure includes coal mines, they account for only a fraction of the costs.

Over the years, the people of Fort McKay have discussed moving the entire community to their reserve at Moose Lake, about 40 miles northwest, to get away from the development—Alberta’s government recently agreed to restrict, but not prohibit, deep-extraction tar sands sites within a 6-mile buffer around the lake. But for now, it seems, Fort McKay will remain where it is.

L’Hommecourt said she is torn about whether she will remain here. “My heart is in the boreal forest,” she said.

But her kids want to move away, and if they do, she might, too. The mines are coming closer to the cabin, more roads are getting blocked off.

Regulatory filings show that Imperial Oil plans eventually to reroute the creek that runs past her cabin to make way for its Kearl mine. If it did so, the land where the cabin sits would be buried by land cleared from elsewhere within the mine. A spokeswoman for Imperial, Exxon’s Canadian affiliate, declined to comment specifically on the filings, but said the company “has collaborative and unique relationship agreements with these local communities that provide mutual benefits.”

The cabin itself has been a symbol of L’Hommecourt’s resistance. It sits on an old trappers’ trail that Imperial’s workers began using about 10 years ago as an unpaved access road for exploration, marking it off with a “No Trespassing” sign. L’Hommecourt built her cabin in the middle of that road.

“I just said ‘I don’t care,’” L’Hommecourt said. “I’m gonna put my house right here and this is where it’s going to be.” When company workers come by, she said, “I just tell them, ‘turn around and go back, and if you have a problem with it, get your VP or whoever it is that you report to and then tell them to come and see me.”

So far, no one has shown up.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611