|

|

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The lie that the election was ‘stolen’ from Trump is building its monuments in ludicrous stories, and codifying them in laws to make the next elections easier to pilfer

Some of us pick up our pens and do what we can. We quote wise scribes such as George Orwell on how there may be a latent fascist waiting to emerge in all humans, or Hannah Arendt on how democracies are inherently unstable and susceptible to ruin by aggressive, skilled demagogues. We turn to Alexis de Tocqueville for his stunning insights into American individualism while we love to believe his claims that democracy would create greater equality. And oh! how we love Walt Whitman’s fabulously open, infinite democratic spirit. We inhale Whitman’s verses and are captured by the hypnotic power of democracy. “O Democracy, for you, for you I am trilling these songs,” wrote our most exuberant democrat.

Read enough of the right Whitman and you can believe again that American democracy may yet be “the continent indissoluble … with the life-long love of comrades”. But just now we cannot rely on the genius alone of our wise forbears. We have to face our own mess, engage the fight before us, and prepare for the worst.

Our democracy allows a twice-impeached, criminally inclined ex-president, who publicly fomented an attempted coup against his own government, and still operates as a gangster leader of his political party, to peacefully reside in our midst while under investigation for his misdeeds. We believe in rule of law, and therefore await verdicts of our judicial system and legislative inquiry.

Yet Trumpism unleashed on 6 January, and every day before and since over a five-year period, a crusade to slowly poison the American democratic experiment with a movement to overturn decades of pluralism, increased racial and gender equality, and scientific knowledge. To what end? Establishing a hopeless white utopia for the rich and the aggrieved.

On this 6 January anniversary is it time to sing anew with Whitmanesque fervor, or is the only rational response to scream? First the scream.

On 6 January 2021, an American mob, orchestrated by the most powerful man in the land, along with many congressional and media allies, nearly destroyed our indirect electoral democracy. To this day, only Trump’s laziness and incompetence may explain why he did not force Vice-President Mike Pence to resign in the two months before the coup attempt, install a genuine lackey like Mark Meadows, and set up the formal disruption of the count of electoral votes. The real coup needed guns, and military brass thankfully made clear they would oppose any attempt at imposing martial law. But the coup endures by failing; it now takes the form of voter suppression laws, virulent states’ rights doctrine applied to all manner of legislative action installing Republican loyalists in the electoral system, and a propaganda machine capable of popularizing lies big and small.

The lies have now crept into a Trumpian Lost Cause ideology, building its monuments in ludicrous stories that millions believe, and codifying them in laws to make the next elections easier to pilfer. If you repeat the terms “voter fraud” and “election integrity” enough times on the right networks you have a movement. And “replacement theory” works well alongside a thousand repetitions of “critical race theory”, both disembodied of definition or meaning, but both scary. Liberals sometimes invite scorn with their devotion to diversity training and insistence on fighting over words rather than genuine inequality. But it is time to see the real enemy – a long-brewing American-style neo-fascist authoritarianism, beguilingly useful to the grievances of the disaffected, and threatening to steal our microphones midway through our odes to joy.

Yes, disinformation has to be fought with good information. But it must also be fought with fierce politics, with organization, and if necessary with bodies, non-violently. We have an increasingly dangerous population on the right. Who do you know who really wants to compromise with their ideas? Who on the left will volunteer to be part of a delegation to go discuss the fate of democracy with Mitch McConnell, Kevin McCarthy or the foghorns of Fox News? Who on the right will come to a symposium with 10 of the finest writers on democracy, its history and its philosophy, and help create a blueprint for American renewal? As a culture we are not in the mood for such reason and comity; we are in a fight, and it needs to happen in politics. Otherwise it may be 1861 again in some very new form. Unfortunately it is likely to take events even more shocking than 6 January to move our political culture through and beyond our current crisis.

And if and when it is 1861 again, the new secessionists, namely the Republican party, will have a dysfunctional constitution to exploit. The ridiculously undemocratic US Senate, now 50/50 between the two parties, but where Democrats represent 56.5% of the population and Republicans 43.5%, augurs well for those determined to thwart majoritarian democracy. And, of course, the electoral college – an institution more than two centuries out of date, and which even our first demagogue president, Andrew Jackson, advocated abolishing – offers perennial hope to Republicans who may continue to lose popular votes but win the presidency, as they have in two of the last six elections. Democracy?

And now the song? Well, keep reading. Of all the books on democracy in recent years one of the best is James Miller’s Can Democracy Work? A Short History of a Radical Idea, from Ancient Athens to Our World. A political philosopher and historian, Miller provides an intelligent journey through the turbulent past of this great human experiment in whether people can actually govern themselves. He demonstrates how thin the lines are between success and disaster for democracies, how big wins turn into reactions and big losses, and how the dynamics of even democratic societies can be utterly amoral. Intolerant new ruling classes sometimes replace the tyrants they overthrow.

“Democratic revolts, like democratic elections,” Miller writes, “can produce perverse outcomes.” History is still waiting for us. But in the end, via examples like Václav Havel in the Czech Republic, Miller reminds us that the “ideal survives”. Democracy does require the “best laws”, Havel intoned, but it must also manifest as “humane, moral, intellectual and spiritual, and cultural”. Miller does the history to show that democracy is almost always a “riddle, not a recipe”. Democracy is much harder than autocracy to sustain. But renew it we must.

Or simply pick up Whitman’s Song of Myself, all 51 pages, from the opening line, “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” to his musings on the luck of merely being alive. Keep going to a few pages later when a “runaway slave” enters Whitman’s home and the poet gazes into his “revolving eyes”, and nurses “the galls of his neck and ankles”, and then to his embrace of “primeval”, complete democracy midway in the song, where he accepts “nothing which all cannot have”. Finally read to the ending, where the poet finds blissful oblivion, bequeathing himself “to the dirt to grow from the grass I love”. Whitman’s “sign of democracy” is everywhere and in everything. The democratic and the authoritarian instinct are both deep within us, forever at war.

After 6 January, it’s time to prepare thee to sing, to scream, and to fight.

David Blight is professor of American history at Yale University and author of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, and the forthcoming Frederick Douglass: American Prophet.

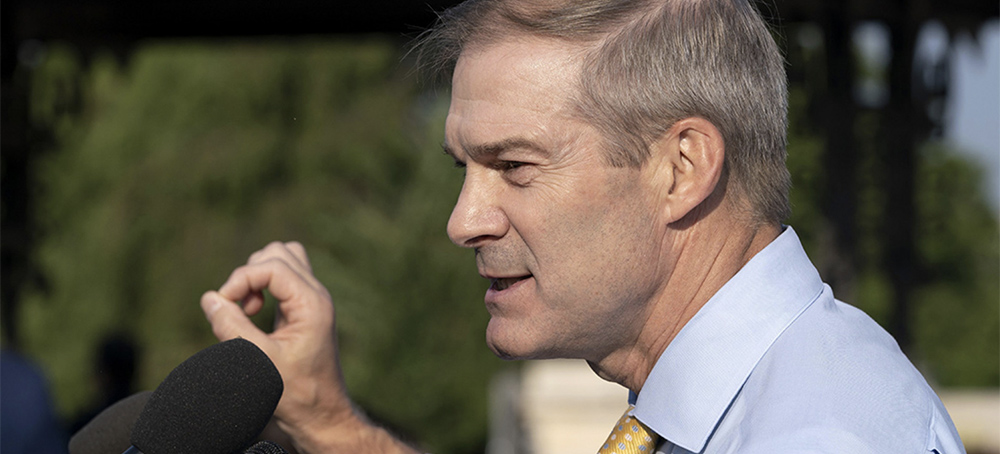

Rep. Jim Jordan was among the House Republicans who worked most closely with Trump in the run-up to the Jan. 6 session of Congress meant to finalize the 2020 presidential election results. (photo: Jacquelyn Martin/AP)

Rep. Jim Jordan was among the House Republicans who worked most closely with Trump in the run-up to the Jan. 6 session of Congress meant to finalize the 2020 presidential election results. (photo: Jacquelyn Martin/AP)

His decision follows a similar rejection by Rep. Scott Perry, the only other lawmaker whose testimony the panel has requested so far.

“Your attempt to pry into the deliberative process informing a Member about legislative matters before the House is an outrageous abuse of the Select Committee’s authority,” the Ohio Republican said in a four-page letter to Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.), the panel chair.

Jordan’s decision follows a similar rejection by Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.), the only other lawmaker whose testimony the committee has requested so far. Although Thompson initially indicated the committee might pursue various “tools” to force recalcitrant lawmakers to comply, he has since suggested that the panel may have little leverage against lawmakers who don’t cooperate voluntarily.

Instead, Thompson has indicated the panel will use the “court of public opinion” to reveal lawmakers’ conduct ahead of and on Jan. 6 — via obtained messages and testimony — and leave it to them to explain why they didn’t cooperate with investigators.

A select panel spokesperson said the committee would respond to Jordan’s letter more in the “coming days” and would “consider appropriate next steps.”

“Mr. Jordan has admitted that he spoke directly to President Trump on January 6th and is thus a material witness,” a panel spokesperson said. “Mr. Jordan’s letter to the committee fails to address these facts.”

Jordan was among the House Republicans who worked most closely with Trump in the run-up to the Jan. 6 session of Congress meant to finalize the 2020 presidential election results. He also has acknowledged speaking with Trump at least once after rioters had overtaken the Capitol.

The panel sent a letter to Jordan on Dec. 22 seeking an interview with him about his conversations with Trump on Jan. 6, communications with Trump’s allies about actions and strategies on Jan. 6, and efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

The committee recently revealed a text message from Jordan to then-White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows on Jan. 5 in which he forwarded a strategy for blocking Joe Biden’s election. According to Jordan, he was passing along a plan sent to him by a former Pentagon inspector general. His aides have declined to say whether he supported that strategy or why he decided to send it to Meadows.

Jordan has frequently insisted he has “nothing to hide” when asked if he would cooperate with the Jan. 6 select committee, and he has expressed uncertainty about whether he had one or multiple conversations with Trump on Jan. 6 — both before and after the riot.

The Amazon Fulfillment Center in Edwardsville, Illinois, that was damaged by a tornado on December 10, 2021, killing six people. (photo: Tim Vizer/AFP/Getty Images)

The Amazon Fulfillment Center in Edwardsville, Illinois, that was damaged by a tornado on December 10, 2021, killing six people. (photo: Tim Vizer/AFP/Getty Images)

Six workers were killed last month because Amazon insisted they keep working during a tornado. The corporation's poor safety record and sky-high staff turnover are caused by one thing: treating people as disposable is better for Amazon’s profits.

De’Andre Morrow was one of six Amazon workers killed at the Edwardsville, Illinois, warehouse. When the tornado struck, there were forty-six workers trapped in the building, but only one designated safe room. The safe room was located at the northern edge of the 1.1-million-square-foot facility. Some accounts have the tornado touching down at 8:28 p.m. and the Amazon warehouse collapsing at 8:33 p.m. All six workers who died that night were unable to reach this segmented safe area.

Morrow and his coworkers died during a natural disaster. But it would be a mistake to view their deaths as accidental or as isolated tragedies. These workers were killed because Amazon has an ongoing policy of threatening people’s jobs and coercing employees to continue working through dangerous situations, whether it’s a tornado, a pandemic, or just the daily grind of “making rate” during a ten-hour shift.

While Amazon has kept the national scope of worker deaths under lock and key, Cori Bush, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Elizabeth Warren are now demanding a ten-year list of all on-site deaths with an explanation. Amazon has ignored previous requests of this type in the past. What we do know is that serious worker injuries at Amazon are increasing year after year, despite the company’s chronic underreporting, and they are already 80 percent higher than industry averages.

Incessant Turnover

During the tornado in Edwardsville, one of Amazon’s contract delivery drivers was texting with their supervisor. In the hour leading up to the tornado’s touchdown, the driver was told to “just keep delivering,” despite their requests for a chance to find shelter. When their supervisor said no, the delivery worker accused Amazon of “wanting to turn this van into a casket.”

A recurring complaint from Amazon warehouse and delivery workers has been the feeling that they are completely disposable. Amazon has a nationwide weekly turnover rate of 3 percent, or roughly thirty thousand employees — equivalent to a total replacement of all its hourly workers every eight months. While many companies consider high turnover costly, Amazon’s workplace is designed for rapidly replacing workers. Jeff Bezos famously called an entrenched workforce a “march to mediocrity.” Rapid turnover also benefits Amazon’s bottom line by making long-term strategies like unionizing more difficult and stopping employees from accessing the benefits accrued over time, repeatedly touted by company spokespersons as an advantage of working there.

High turnover thus accelerates a race to the bottom whereby wages get repeatedly reset to their starting point. In a practice being mainstreamed by Amazon, workers, after their first year of employment, are offered increasing sums of cash up front if they choose to quit. In 2019, to make the point clearer, Amazon hired around 770,000 new hourly workers but had fired or lost more than 660,000 of them by the year’s end. By all accounts, these trends only accelerated with the pandemic. And that’s not to mention the fate of part-time employees.

The politics and policy of disposability can also be seen, specifically, in the death of these six workers inside the Edwardsville warehouse. Theories of disposability were popularized by critical race scholars to describe how structural violence operates to abandon racialized populations, killing by neglect. Disposability politics asks how we can understand Morrow and his coworkers’ deaths as an outcome Amazon allowed, expected, and predicted.

Dead Labor

Perhaps no one has addressed this question more acutely than James Tyner, author of Dead Labor: Toward a Political Economy of Premature Death, published in 2019. Tyner’s work traces history back to the 1600s in order to understand how the premature death of workers became something “calculable, manageable, predictable, and even profitable.” Tyner’s work explores the long-standing contradiction within capitalism between increasing work demands and keeping workers alive. As Tyner points out, citing Karl Marx, “Capital . . . takes no account of the health and the length of life of the worker, unless society forces it to do so.”

Natural disasters such as this tornado cannot themselves be controlled. But they are predictable and, in fact, predicted. Far from this being a freak accident, Illinois weathers an average of fifty-four tornadoes each year, and it’s located on the border of what’s known as “tornado alley.” When Amazon decided to construct this Edwardsville facility in 2018, it was always a question of when, not if, a tornado would hit.

During a press conference the following Monday, Amazon’s senior vice president of global delivery serviced, John Felton, said “all procedures were followed correctly.” In a sense, he was right: it is company procedure to keep scores of workers on-site during natural disasters; it is company procedure to continue working through severe weather alerts and tornado sirens; and it is company procedure to wait until a tornado has actually touched down before allowing workers to stop working and find shelter.

Looking at what Tyner calls the political economy of death, we can infer from this catastrophe that the value of workers’ lives at Amazon is less than the potential profits from a single day, or even a single hour, of their labor. If those calculations were otherwise, Amazon would have simply allowed workers to go home once the National Weather Service issued an emergency alert. These calculations, in the aggregate, are what Tyner calls an “economic bio-arithmetic,” whereby many are “left to die so that others may enjoy the fruits of (dead) laborers.” This is the price of Amazon Prime’s next-day deliveries.

Every day, Amazon shifts the burden onto employees to make these life-and-death decisions, weighing their job against their safety. In Boulder, Colorado, an Amazon driver was hailed as a “hero” and an “angel” for rescuing a family of three during the urban firestorm that consumed six thousand acres and one thousand homes last week. As the fire blazed, the driver — “Lou Ann” — drove through the evacuated emergency area in order to deliver a bike pump to the family. Newsweek reported on the incident, taking a baffled tone, writing that the Amazon driver had “apparently decided to risk life and limb to deliver a bicycle pump amid the inferno” [italics added].

Newsweek’s description is both true and egregiously devoid of a labor perspective. Of the 190 people employed at the Edwardsville delivery depot, only seven are full-time Amazon workers. Subcontract capitalism, embodied by the gig economy, depends on these illusory notions of worker choice and agency. Tyner writes, “Neither corporations nor the state take responsibility for the plight of any particular individual if, as totally free agents, he or she is assumed to be fully responsible for his or her condition.”

All workers are compelled to participate in the wage labor market in order to get by — so all labor is, to some degree, forced. Yet Newsweek ascribes this worker the status of a free agent — an autonomous actor making the unconstrained yet illogical decision to deliver bike pumps into a wildfire.

Social Murder

We have to insist on a reinterpretation of these tragic deaths in Edwardsville as what they are: murder. While they happened during a natural disaster, these were not natural deaths. Speaking of the premature death of English workers in the nineteenth century, Friedrich Engels wrote of this same common misrepresentation: “because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains.” For Amazon, workers dying is the cost of doing business, and it often costs less than keeping them alive. In a capitalist system, allowing workers to die in this way is a rational choice for Amazon’s bottom line — and it is a choice the company makes time and again.

Marx further identified this equation in Capital, writing that what interests capital

is purely and simply the maximum of labor power that can be set in motion in a working day. It attains this objective by shortening the life of labor-power, in the same way as a greedy farmer snatches more produce from the soil by robbing it of its fertility.

Marx, and more recently Tyner, both point to the idea that capitalists like Bezos, in the most literal sense, plan on their workers dying in preventable fashions. Capital, Tyner writes, “reproduces itself at the cost of the life of the laborer.”

Yet the United States is seeing a resurgence of the labor movement, with historic numbers of strikes and union drives across multiple industries. Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama, are now entering the second year of their struggle to form a union. Amid that struggle, the Bessemer warehouse also made headlines recently when two workers died on the warehouse floor, only hours apart. One of the workers had been denied sick leave just a few hours prior. In all, six people have died at the Bessemer site during 2021 alone.

If they win the necessary votes, Bessemer would be the first Amazon warehouse to unionize in the country. And ultimately, the collective bargaining power of workers is one of the only, if not the only, thing that can force Amazon to change. The company is growing exponentially and is set to surpass Walmart as the nation’s largest employer by the year’s end. In 2022, the stakes have never been higher for American workers.

No one understands this better than the workers at Amazon. As one Bessemer employee put it: “You’re a body. Once that body’s used up, they’ll just bring somebody else in and do the work.”

The aftermath of a airstrike targeting ISIS. (photo: Marcus Yam/Getty Images)

The aftermath of a airstrike targeting ISIS. (photo: Marcus Yam/Getty Images)

Yes, it’s true. After 20 years of war — actually, more like 30 years if you count American involvement in the Russian version of that conflict in the 1980s — the U.S. has finally waved goodbye to Afghanistan (at least for now). Its last act in Kabul was the drone-slaughtering of seven children and three adult civilians with a Hellfire missile. And that, as Azmat Khan recently showed in a striking report in the New York Times Magazine, was pretty much par for the course in this country’s global war on terror that, for countless civilians, has distinctly been a war of terror of the most horrific sort.

In those same years, this country led the way in the use of Hellfire-missile-armed drones globally, while our president — any president you care to name — became an assassin-in-chief, something Donald Trump showed all too clearly when he used a drone to take out Iran’s second most powerful leader at Baghdad International Airport in January 2020. And though Joe Biden has launched significantly fewer drone strikes so far than his predecessors, he’s still been ordering them, too.

Worse yet, it’s sadly clear that, however sci-fi-like those drones once seemed, they’re still piloted by actual human beings (even if from far, far away). As such, they represent a relatively early stage in the process of fully automating weapons systems on land, on sea, and in the air — and the decision-making that goes with them — a development, as TomDispatch regular Rebecca Gordon reports today, that this country is all-too-enthusiastically involved in.

Count on one thing as you read her latest piece and think about automating a global killing machine: such mechanisms, created by humans, will prove no less destructive to us than the previously piloted or driven versions of the same. Now, consider the future of automated killing, up close and personal.

-Tom Engelhardt, TomDispatch

Science fiction? Not really. It could happen tomorrow. The technology already exists.

In fact, lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) have a long history. During the spring of 1972, I spent a few days occupying the physics building at Columbia University in New York City. With a hundred other students, I slept on the floor, ate donated takeout food, and listened to Alan Ginsberg when he showed up to honor us with some of his extemporaneous poetry. I wrote leaflets then, commandeering a Xerox machine to print them out.

And why, of all campus buildings, did we choose the one housing the Physics department? The answer: to convince five Columbia faculty physicists to sever their connections with the Pentagon’s Jason Defense Advisory Group, a program offering money and lab space to support basic scientific research that might prove useful for U.S. war-making efforts. Our specific objection: to the involvement of Jason’s scientists in designing parts of what was then known as the “automated battlefield” for deployment in Vietnam. That system would indeed prove a forerunner of the lethal autonomous weapons systems that are poised to become a potentially significant part of this country’s — and the world’s — armory.

Early (Semi-)Autonomous Weapons

Washington faced quite a few strategic problems in prosecuting its war in Indochina, including the general corruption and unpopularity of the South Vietnamese regime it was propping up. Its biggest military challenge, however, was probably North Vietnam’s continual infiltration of personnel and supplies on what was called the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran from north to south along the Cambodian and Laotian borders. The Trail was, in fact, a network of easily repaired dirt roads and footpaths, streams and rivers, lying under a thick jungle canopy that made it almost impossible to detect movement from the air.

The U.S. response, developed by Jason in 1966 and deployed the following year, was an attempt to interdict that infiltration by creating an automated battlefield composed of four parts, analogous to a human body’s eyes, nerves, brain, and limbs. The eyes were a broad variety of sensors — acoustic, seismic, even chemical (for sensing human urine) — most dropped by air into the jungle. The nerve equivalents transmitted signals to the “brain.” However, since the sensors had a maximum transmission range of only about 20 miles, the U.S. military had to constantly fly aircraft above the foliage to catch any signal that might be tripped by passing North Vietnamese troops or transports. The planes would then relay the news to the brain. (Originally intended to be remote controlled, those aircraft performed so poorly that human pilots were usually necessary.)

And that brain, a magnificent military installation secretly built in Thailand’s Nakhon Phanom, housed two state-of-the-art IBM mainframe computers. A small army of programmers wrote and rewrote the code to keep them ticking, as they attempted to make sense of the stream of data transmitted by those planes. The target coordinates they came up with were then transmitted to attack aircraft, which were the limb equivalents. The group running that automated battlefield was designated Task Force Alpha and the whole project went under the code name Igloo White.

As it turned out, Igloo White was largely an expensive failure, costing about a billion dollars a year for five years (almost $40 billion total in today’s dollars). The time lag between a sensor tripping and munitions dropping made the system ineffective. As a result, at times Task Force Alpha simply carpet-bombed areas where a single sensor might have gone off. The North Vietnamese quickly realized how those sensors worked and developed methods of fooling them, from playing truck-ignition recordings to planting buckets of urine.

Given the history of semi-automated weapons systems like drones and “smart bombs” in the intervening years, you probably won’t be surprised to learn that this first automated battlefield couldn’t discriminate between soldiers and civilians. In this, they merely continued a trend that’s existed since at least the eighteenth century in which wars routinely kill more civilians than combatants.

None of these shortcomings kept Defense Department officials from regarding the automated battlefield with awe. Andrew Cockburn described this worshipful posture in his book Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins, quoting Leonard Sullivan, a high-ranking Pentagon official who visited Vietnam in 1968: “Just as it is almost impossible to be an agnostic in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, so it is difficult to keep from being swept up in the beauty and majesty of the Task Force Alpha temple.”

Who or what, you well might wonder, was to be worshipped in such a temple?

Most aspects of that Vietnam-era “automated” battlefield actually required human intervention. Human beings were planting the sensors, programming the computers, piloting the airplanes, and releasing the bombs. In what sense, then, was that battlefield “automated”? As a harbinger of what was to come, the system had eliminated human intervention at a single crucial point in the process: the decision to kill. On that automated battlefield, the computers decided where and when to drop the bombs.

In 1969, Army Chief of Staff William Westmoreland expressed his enthusiasm for this removal of the messy human element from war-making. Addressing a luncheon for the Association of the U.S. Army, a lobbying group, he declared:

“On the battlefield of the future enemy forces will be located, tracked, and targeted almost instantaneously through the use of data links, computer-assisted intelligence evaluation, and automated fire control. With first round kill probabilities approaching certainty, and with surveillance devices that can continually track the enemy, the need for large forces to fix the opposition will be less important.”

What Westmoreland meant by “fix the opposition” was kill the enemy. Another military euphemism in the twenty-first century is “engage.” In either case, the meaning is the same: the role of lethal autonomous weapons systems is to automatically find and kill human beings, without human intervention.

New LAWS for a New Age — Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems

Every autumn, the British Broadcasting Corporation sponsors a series of four lectures given by an expert in some important field of study. In 2021, the BBC invited Stuart Russell, professor of computer science and founder of the Center for Human-Compatible Artificial Intelligence at the University of California, Berkeley, to deliver those “Reith Lectures.” His general subject was the future of artificial intelligence (AI), and the second lecture was entitled “The Future Role of AI in Warfare.” In it, he addressed the issue of lethal autonomous weapons systems, or LAWS, which the United Nations defines as “weapons that locate, select, and engage human targets without human supervision.”

Russell’s main point, eloquently made, was that, although many people believe lethal autonomous weapons are a potential future nightmare, residing in the realm of science fiction, “They are not. You can buy them today. They are advertised on the web.”

I’ve never seen any of the movies in the Terminator franchise, but apparently military planners and their PR flacks assume most people derive their understanding of such LAWS from this fictional dystopian world. Pentagon officials are frequently at pains to explain why the weapons they are developing are not, in fact, real-life equivalents of SkyNet — the worldwide communications network that, in those films, becomes self-conscious and decides to eliminate humankind. Not to worry, as a deputy secretary of defense told Russell, “We have listened carefully to these arguments and my experts have assured me that there is no risk of accidentally creating SkyNet.”

Russell’s point, however, was that a weapons system doesn’t need self-awareness to act autonomously or to present a threat to innocent human beings. What it does need is:

The reality is that such systems already exist. Indeed, a government-owned weapons company in Turkey recently advertised its Kargu drone — a quadcopter “the size of a dinner plate,” as Russell described it, which can carry a kilogram of explosives and is capable of making “anti-personnel autonomous hits” with “targets selected on images and face recognition.” The company’s site has since been altered to emphasize its adherence to a supposed “man-in-the-loop” principle. However, the U.N. has reported that a fully-autonomous Kargu-2 was, in fact, deployed in Libya in 2020.

You can buy your own quadcopter right now on Amazon, although you’ll still have to apply some DIY computer skills if you want to get it to operate autonomously.

The truth is that lethal autonomous weapons systems are less likely to look like something from the Terminator movies than like swarms of tiny killer bots. Computer miniaturization means that the technology already exists to create effective LAWS. If your smart phone could fly, it could be an autonomous weapon. Newer phones use facial recognition software to “decide” whether to allow access. It’s not a leap to create flying weapons the size of phones, programmed to “decide” to attack specific individuals, or individuals with specific features. Indeed, it’s likely such weapons already exist.

Can We Outlaw LAWS?

So, what’s wrong with LAWS, and is there any point in trying to outlaw them? Some opponents argue that the problem is they eliminate human responsibility for making lethal decisions. Such critics suggest that, unlike a human being aiming and pulling the trigger of a rifle, a LAWS can choose and fire at its own targets. Therein, they argue, lies the special danger of these systems, which will inevitably make mistakes, as anyone whose iPhone has refused to recognize his or her face will acknowledge.

In my view, the issue isn’t that autonomous systems remove human beings from lethal decisions. To the extent that weapons of this sort make mistakes, human beings will still bear moral responsibility for deploying such imperfect lethal systems. LAWS are designed and deployed by human beings, who therefore remain responsible for their effects. Like the semi-autonomous drones of the present moment (often piloted from half a world away), lethal autonomous weapons systems don’t remove human moral responsibility. They just increase the distance between killer and target.

Furthermore, like already outlawed arms, including chemical and biological weapons, these systems have the capacity to kill indiscriminately. While they may not obviate human responsibility, once activated, they will certainly elude human control, just like poison gas or a weaponized virus.

And as with chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, their use could effectively be prevented by international law and treaties. True, rogue actors, like the Assad regime in Syria or the U.S. military in the Iraqi city of Fallujah, may occasionally violate such strictures, but for the most part, prohibitions on the use of certain kinds of potentially devastating weaponry have held, in some cases for over a century.

Some American defense experts argue that, since adversaries will inevitably develop LAWS, common sense requires this country to do the same, implying that the best defense against a given weapons system is an identical one. That makes as much sense as fighting fire with fire when, in most cases, using water is much the better option.

The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons

The area of international law that governs the treatment of human beings in war is, for historical reasons, called international humanitarian law (IHL). In 1995, the United States ratified an addition to IHL: the 1980 U.N. Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. (Its full title is much longer, but its name is generally abbreviated as CCW.) It governs the use, for example, of incendiary weapons like napalm, as well as biological and chemical agents.

The signatories to CCW meet periodically to discuss what other weaponry might fall under its jurisdiction and prohibitions, including LAWS. The most recent conference took place in December 2021. Although transcripts of the proceedings exist, only a draft final document — produced before the conference opened — has been issued. This may be because no consensus was even reached on how to define such systems, let alone on whether they should be prohibited. The European Union, the U.N., at least 50 signatory nations, and (according to polls), most of the world population believe that autonomous weapons systems should be outlawed. The U.S., Israel, the United Kingdom, and Russia disagree, along with a few other outliers.

Prior to such CCW meetings, a Group of Government Experts (GGE) convenes, ostensibly to provide technical guidance for the decisions to be made by the Convention’s “high contracting parties.” In 2021, the GGE was unable to reach a consensus about whether such weaponry should be outlawed. The United States held that even defining a lethal autonomous weapon was unnecessary (perhaps because if they could be defined, they could be outlawed). The U.S. delegation put it this way:

“The United States has explained our perspective that a working definition should not be drafted with a view toward describing weapons that should be banned. This would be — as some colleagues have already noted — very difficult to reach consensus on, and counterproductive. Because there is nothing intrinsic in autonomous capabilities that would make a weapon prohibited under IHL, we are not convinced that prohibiting weapons based on degrees of autonomy, as our French colleagues have suggested, is a useful approach.”

The U.S. delegation was similarly keen to eliminate any language that might require “human control” of such weapons systems:

“[In] our view IHL does not establish a requirement for ‘human control’ as such… Introducing new and vague requirements like that of human control could, we believe, confuse, rather than clarify, especially if these proposals are inconsistent with long-standing, accepted practice in using many common weapons systems with autonomous functions.”

In the same meeting, that delegation repeatedly insisted that lethal autonomous weapons would actually be good for us, because they would surely prove better than human beings at distinguishing between civilians and combatants.

Oh, and if you believe that protecting civilians is the reason the arms industry is investing billions of dollars in developing autonomous weapons, I’ve got a patch of land to sell you on Mars that’s going cheap.

The Campaign to Stop Killer Robots

The Governmental Group of Experts also has about 35 non-state members, including non-governmental organizations and universities. The Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, a coalition of 180 organizations, among them Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the World Council of Churches, is one of these. Launched in 2013, this vibrant group provides important commentary on the technical, legal, and ethical issues presented by LAWS and offers other organizations and individuals a way to become involved in the fight to outlaw such potentially devastating weapons systems.

The continued construction and deployment of killer robots is not inevitable. Indeed, a majority of the world would like to see them prohibited, including U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres. Let’s give him the last word: “Machines with the power and discretion to take human lives without human involvement are politically unacceptable, morally repugnant, and should be prohibited by international law.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Rebecca Gordon, a TomDispatch regular, teaches at the University of San Francisco. She is the author of Mainstreaming Torture, American Nuremberg: The U.S. Officials Who Should Stand Trial for Post-9/11 War Crimes and is now at work on a new book on the history of torture in the United States.

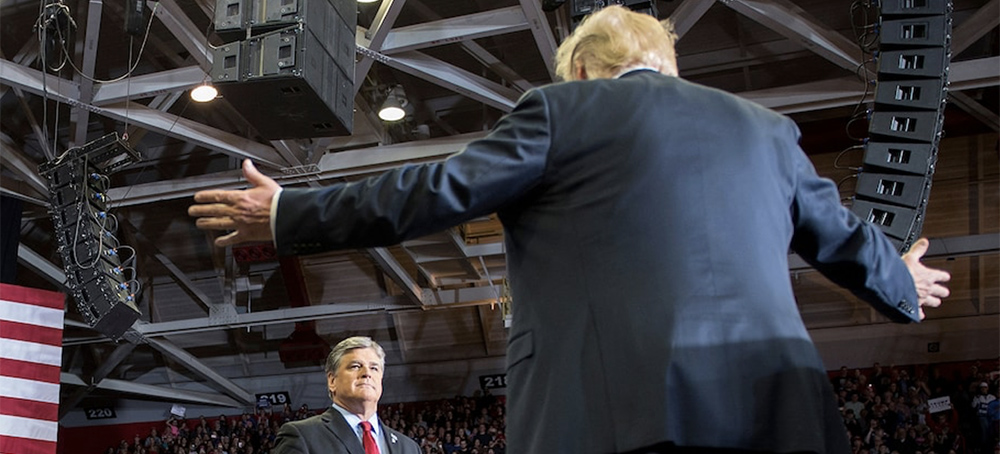

President Donald Trump greets Fox News talk show host Sean Hannity at a political rally in Cape Girardeau, Mo., in November 2018. (photo: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images)

President Donald Trump greets Fox News talk show host Sean Hannity at a political rally in Cape Girardeau, Mo., in November 2018. (photo: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images)

“There were times the president would come down the next morning and say, ‘Well, Sean thinks we should do this,’ or, ‘Judge Jeanine thinks we should do this,’ ” said Grisham, referring to Sean Hannity and Jeanine Pirro, both of whom host prime-time Fox News shows.

Grisham — who resigned from the White House amid the Jan. 6 attacks and has since written a book critical of Trump — said West Wing staffers would simply roll their eyes in frustration as they scrambled to respond to the influence of the network’s hosts, who weighed in on everything from personnel to messaging strategy.

Trump’s staff, allies and even adversaries were long accustomed to playing to an “Audience of One” — a commander in chief with a twitchy TiVo finger and obsessed with cable news.

But text messages — newly released by the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection — between Fox News hosts and former Trump chief of staff Mark Meadows, crystallize with new specificity just how tightly Fox News and the White House were entwined during the Trump years, with many of the network’s top hosts serving as a cable cabinet of unofficial advisers.

As the Jan. 6 attacks on the U.S. Capitol unfolded, Meadows received texts from Fox News hosts Laura Ingraham and Brian Kilmeade, as well as Hannity, according to the newly released communications.

“Mark, the president needs to tell people in the Capitol to go home,” Ingraham wrote. “This is hurting all of us. He is destroying his legacy.” Ingraham’s private missives, however, differed starkly from what she said on her show later that evening, when she began whitewashing the violence of the day and claiming the attacks were “antithetical” to the Trump movement.

Kilmeade urged Meadows to get Trump “on TV” to call off the rioters, writing, “Destroying everything you have accomplished.”

And Hannity asked Meadows, “Can he make a statement? Ask people to leave the Capitol.”

Other texts released by the committee reveal that Hannity also offered the White House advice in the run-up and aftermath to the attacks that resulted in five deaths. On Dec. 31, 2020, Hannity texted Meadows to warn, “I do NOT see January 6 happening the way he is being told.” And on Jan. 10, 2021 — referring to a conversation he had with Trump himself — Hannity texted Meadows and Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), a close Trump ally, to try to discuss strategies to rein in Trump.

“Guys, we have a clear path to land the plane in 9 days,” Hannity wrote. “He can’t mention the election again. Ever. I did not have a good call with him today. And worse, I’m not sure what is left to do or say, and I don’t like not knowing if it’s truly understood. Ideas?”

A former senior administration official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share candid details of private discussions, said Trump would also sometimes dial Hannity and Lou Dobbs — whose Fox Business show was canceled in February — into Oval Office staff meetings.

“A lot of it was PR — what he should be saying and how he should be saying it; he should be going harder against wearing masks or whatever,” Grisham said. “And they all have different opinions, too.”

A Trump spokesman did not respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson for Fox News declined to comment.

Michael Pillsbury, an informal Trump adviser, said he realized how powerful Fox News was in Trump’s orbit when the former president began embracing Sidney Powell — an attorney promoting Trump’s false claims of widespread voter fraud — and other election fabulists after seeing them on Dobbs’s show. Pillsbury added that while it seemed obvious that many of the claims were patently false, Trump was inclined to believe them, in part because he was watching them on TV and had affection for Dobbs in particular.

“It taught me the power of the young producers at Fox, and Fox Business especially,” Pillsbury said. “These young producers who are in their mid-20s. They come out of the conservative movement, they‘ve never been in the government. They are presented with these reckless, fantastical accounts. And they believe them and put them on for ratings.”

Alyssa Farah, a former White House communications director, said the four most influential Fox hosts were Dobbs, Hannity, Igraham, and Pirro — and in the final year of the Trump administration, Hannity was the most influential. Other former top administration officials also mentioned Mark Levin, another Fox News host, and Maria Bartiromo, a Fox Business host, as two other network stars in regular touch with the White House.

From the point of view of the staff, Farah said, the goal was simply to “try to get ahead of what advice you thought he was going to be given by these people” because their unofficial counsel “could completely change his mind on something.”

But the relationship was also symbiotic, with White House aides actively trying to influence the network, especially on issues such as spending deals and averting government shutdowns. They knew if they could get Fox hosts to echo their goals on air, that would help sway the president.

Jeff Cohen, author of “Cable News Confidential: My Misadventures in Corporate Media,” said the recent text messages represent a “smoking gun.”

“If you watch Fox News as much as I do, and I watch a few hours a night, they’re always signaling their close contact with the White House,” Cohen said referring to the Trump era. “But these texts are just the hard evidence. This is just how deeply intertwined the Fox News leadership is with Trump and the Trump White House.”

The problem, he explained, is that even though many of these hosts are opinion journalists, they are still violating public trust by not disclosing the full extent of their relationships with the Trump administration.

“Journalists and media are supposed to be public checks on power, not private advisers to power,” Cohen said. “A commentator is still a journalist, and even if the commentator doesn’t consider him or herself to be a journalist, they still have to tell the public when they played a role in something they’re commenting on.”

One former top White House official said that the hosts often had more influence with Trump based on what they said on air rather than in their various backchannels to him and his team, in part because the former president was obsessed with the following — and ratings — of their shows.

Former Trump chief of staff John F. Kelly told others in the White House that Dobbs’s show was critical to understanding the president and that Trump’s ideas and feelings about people often originated from that program. Kelly also told colleagues that if Dobbs went after a White House senior staffer, they risked their status falling quickly in the eyes of the former president.

When Kelly could not watch the prime-time Fox shows himself, he would ask other staffers to monitor them, and he would scour the White House call logs for the names of Fox News personalities.

Pirro, several Trump aides said, often became irate if the former president did not appear on her show frequently enough in her view, especially if he had been on Hannity’s show several times prior.

Fox shows were so important to the president that White House staffers were determined to get guests booked on them, even forcing staffers to take weekend shifts appearing on Pirro’s show after Pirro complained she couldn’t get a guest — and the former president also called in himself.

During the 2020 presidential campaign, Hannity called Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel and other Trump allies on a number of occasions to voice his months-long concern that the campaign was heading in the wrong direction and Trump would lose unless he turned around his operation, according to a Republican with direct knowledge of the campaign’s operations, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share details of private discussions. They added that Hannity was much more bullish on his show than in private about Trump’s electoral prospects.

As the coronavirus pandemic ramped up in early 2020, a range of Fox News hosts again mobilized to offer backchannel advice to the Trump White House. In March, Tucker Carlson flew to Trump’s private Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Fla., to warn of the seriousness of the virus. Carlson told Trump he might lose the election because of covid-19, while Trump told the prime-time host that the virus wasn’t as deadly as people were claiming.

In April, Ingraham arrived at the White House with two on-air regulars who are part of what she describes as her “medicine cabinet” for a private meeting with Trump. There, she talked up hydroxychloroquine, a controversial anti-malarial drug which public health experts have concluded is not effective as a covid-19 treatment.

An internal Trump coronavirus response team led by Jared Kushner, the former president’s son-in-law and senior adviser, also prioritized the requests of certain VIPs, including Kilmeade and Pirro. Kilmeade had called two administration officials, for instance, to pass along tips about where to obtain personal protective equipment. And Pirro had repeatedly urged administration officials to send a large quantity of masks to a specific New York hospital.

At the time, a Fox News spokeswoman said neither host had been aware that their tips were receiving preferential treatment.

Since leaving office, Trump has vociferously complained about Fox, particularly its coverage of the election and what he views as increasingly negative coverage about him. But he has kept in close touch with many of the hosts and even sees some of them at his Florida resort.

The Jan. 6 committee has asked Hannity to cooperate with its investigation, and he has hired Jay Sekulow, a longtime Trump attorney, to represent him. “We are evaluating the letter from the committee. We remain very concerned about the constitutional implications especially as it relates to the First Amendment. We will respond as appropriate,” Sekulow said in a statement last week.

But some former senior White House officials said the texts make the role of Hannity and others seem more outsize than it was. The former president appreciated that the Fox crew was fighting on his behalf on a daily basis, this person said, “but he would not be like, ‘Let me call Larry Kudlow and change our economic plan because Laura Ingraham said that.’ ”

Of course, Kudlow, who now hosts a show on Fox Business, came to Trump’s attention as a top economic adviser in part because of the business show he previously hosted on CNBC.

Brazil's then president-elect Jair Bolsonaro walks past Brazilian Army generals during a graduation ceremony at the Agulhas Negras Military Academy in Resende, Brazil, on Dec. 1, 2018. (photo: Leo Correa/AP)

Brazil's then president-elect Jair Bolsonaro walks past Brazilian Army generals during a graduation ceremony at the Agulhas Negras Military Academy in Resende, Brazil, on Dec. 1, 2018. (photo: Leo Correa/AP)

President Jair Bolsonaro’s 2022 electoral hopes have dimmed, but the military isn’t ready to give up its new riches and influence.

Bolsonaro, the far-right ideologue and a former army captain himself, made good on his pledge. In 2018, he was elected president with an outspoken retired general as his running mate.

It wasn’t always an obvious turn for the politician and Brazil’s most powerful institution. For many years, military leaders looked down on Bolsonaro, owing to his notorious acts of insubordination. By 2014, as the visit to Agulhas Negras demonstrates, things had clearly changed. The joint power play was already in motion, years before its fruition.

In office, Bolsonaro quickly appointed active-duty and reserve military officers to important civilian posts in his administration — thousands more than any democratically elected president in modern history — handing over responsibility for large swaths of the federal budget and control over the government. With Bolsonaro known to have little patience for the minutiae of his office — he works short hours — critics have consistently wondered who is really running Brazil: the generals or the president?

Not since the military dictatorship of 1964 to 1985 has the army enjoyed such power. The military has used Bolsonaro’s presidency as a vehicle to reclaim political power more subtly than in the past while also more effectively shielding itself from public resentment. Riding the far-right wave, 72 military and police candidates were elected to state and federal office in 2018. Two years later, 859 more won municipal contests.

Military officials ascended to top appointments in government. Some of them were revealed to be at the center of the Bolsonaro administration’s most brazen public corruption schemes and anti-democratic actions. So far, the military appointees have avoided prosecution, or even much scrutiny, perhaps thanks to not-so-veiled threats to Congress and members of the media.

This reality stands in sharp contrast to the public image that Bolsonaro and the military have long cultivated as correctives to the corruption of civilian politicians — despite ample evidence to the contrary. In this October’s elections, the shift in public image could become a liability for Bolsonaro and his military allies.

The military, for its part, is taking steps to ensure that its newfound power will persist no matter who wins the presidential race.

Military Showered With Benefits

Bolsonaro will have showered the Brazilian Armed Forces and police with around $5 billion in new federal money by the end of his first term, according to an analysis by the Estadão newspaper — a considerable sum in a country with an annual discretionary budget limited to around $19 billion and for a president who promised to reduce spending. Defense received the highest discretionary funding allotment of any ministry in the 2021 and 2022 budgets.

While the military has flourished, deep cuts in federal spending have been felt in health, education, environment, science, culture, small-scale agriculture, food security, and anti-poverty programs. Yet in the last three years, the Armed Forces have been spared from the budget cuts, pension reforms, and wage freezes that have impacted Brazil’s civilian ministries and public workforce.

Brazil spends more on its military than the next six Latin American countries combined but nonetheless is known for relying on antiquated equipment. That is because more than 83 percent of its budget goes to salaries and benefits, the majority of which pays for ample pensions and retirement benefits. Bolsonaro, who came into office promising dramatic austerity reforms, has cut social security benefits and public sector pensions, but the military has not been subject to the most severe measures. Military jobs have even seen pay raises.

The president has also pushed through benefits to foster goodwill among police and firefighting agencies, most of which are militarized forces, including giving significant raises to certain officers.

Bolsonaro has repeatedly backed, but failed to pass, a bill that would make it harder to prosecute members of the police and military for crimes such as homicide. Such prosecutions are already astoundingly rare in a country where officers kill more than 17 civilians per day, according to underreported official statistics, and where organized crime gangs led by security forces are a growing menace.

One of the more long-term initiatives in Bolsonaro’s pro-military agenda includes a push to incentivize state and local public schools to “militarize.” In exchange for federal funding and logistical support, the schools adopt a military-style curriculum and create a minimum number of jobs for police and military reservists, who also take over the school’s administration. Nationwide statistics are incomplete, but in the state of Paraná, the governor pledged to militarize around 10 percent of the more than 2,000 schools under his authority.

Thanks to Bolsonaro, some active-duty military officers and reservists, like those working in public schools, can use a loophole to inflate their paychecks. They can now receive their full salary or pension and simultaneously take home the full pay for other public sector work they perform even if the total pay exceeds constitutional limits for public servants, around $90,000 a year. By comparison, half of all Brazilian workers earn $2,775, the national minimum wage, or less annually.

Among the beneficiaries of this new regulation are the president, who gave himself a 6 percent raise, the vice president, and the military officials in Cabinet positions. Reserve Gen. Joaquim Silva e Luna, appointed by Bolsonaro to lead Petrobras, the state-run oil giant, earns nearly six times the limit, a fact that has even drawn criticism from within the ranks.

The Military’s Long Game

That the military would have again waded deep into Brazilian politics solely for cash perks is improbable. “This is important, but it’s not everything,” Piero Leirner, an anthropology professor who has spent his career studying the military, told The Intercept. “The fact that strikes me the most is the restructuring of the state, with a change in legal provisions to produce a convergence of decisions towards military bodies.”

Ana Penido, a defense researcher at São Paulo State University, agrees. “Many analysts have been raising the possibility that something similar to the U.S. deep state is being set up in Brazil,” she said, “that framework where it doesn’t matter if Democrats or Republicans are in charge, some things always remain the same.”

Both specialists point specifically to the Institutional Security Office, or GSI, a Cabinet-level body overseen by a military officer with responsibilities ranging from serving as the president’s chief national security adviser to directly overseeing ABIN, Brazil’s intelligence agency. The GSI was shut down by former President Dilma Rousseff in 2015, who transferred its responsibilities to civilian control, but it was immediately reestablished after her impeachment.

Bolsonaro put Gen. Augusto Heleno, a former aide to a hard-line general who attempted a palace coup during the dictatorship, in charge of the GSI. Heleno was part of an elite group of generals who advised Bolsonaro during the 2018 campaign and has remained an influential voice in the president’s inner circle through years of infighting and intrigue. In turn, he has broadened the GSI’s power considerably, expanding the agency into gathering more politicized and further-reaching intelligence and deploying ABIN spies to infiltrate important ministries.

“It is a more underground project being constructed during the Bolsonaro government that would have the ability to continue influencing power regardless of who wins the election,” said Penido.

As Bolsonaro’s political future dims, finding a way to hang on to power has become increasingly important for the military. “I don’t think they love Bolsonaro for who he is,” Penido said of the generals. “Their priority is their military ‘family,’ and they will join anyone who can prove they are competitive against Lula” — former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the Workers’ Party politician who is leading the early polls. If an alternative to Lula fails to emerge, Penido said, the military will continue to do what it can: “They are making the political calculations to try to remain in important positions of power or at least negotiate on the best possible terms.”

Leirner believes that the military has maintained so much access to power under Bolsonaro — controlling the intelligence apparatus and spreading its officials across the government — that its leadership may be able to seize the upper hand no matter who emerges in power. He said, “They have collected a vast amount of information that can compromise almost everyone in politics.”

A Yellowstone wolf watches biologists after being tranquilized and fitted with a radio collar during wolf collaring operations in Yellowstone National Park. (photo: William Campbell/Sygma via Getty Images)

A Yellowstone wolf watches biologists after being tranquilized and fitted with a radio collar during wolf collaring operations in Yellowstone National Park. (photo: William Campbell/Sygma via Getty Images)

There are now only 94 wolves left in the park's population, with the hunters wiping out almost 1 in 5 (17.5%) of the wolves.

Fifteen of these wolves were shot in Montana after leaving the park, according to figures sent to Insider from the National Parks Service. Five more died in Idaho and Wyoming. Hunting is banned inside Yellowstone.

This total is the highest number of wolves killed in a hunting season since they were introduced back to the park in 1994.

One family group — the Phantom Lake Pack — is now considered "eliminated" after most or all of its members were killed between October and December, AP report.

Naturalists and wolf advocates fear the death toll will climb even higher with months still to go in the hunting season and wolf trapping season just starting, reported The Guardian.

As a result, National Park Service Superintendent Cameron Sholly has asked Montana Governor Greg Gianforte to suspend wolf hunting for the season.

On December 16, Sholly wrote, "Due to the extraordinary number of Yellowstone wolves killed this hunting season, and the high probability of even more park wolves being killed in the near future, I am requesting that you suspend wold hunting in [hunting management units] 313 and 316 for the remainder of this season."

In 2021, Gianforte failed to take a mandatory trapper course after receiving a warning from a Montana game warden for trapping and shooting a radio-collared wolf about 10 miles north of the park.

He was not receptive to Sholly's request, writing in a letter on January 5, "Once a wolf exits the park and enters lands in the State of Montana, it may be harvested pursuant to regulations established by the [state wildlife] Commission under Montana law," the Guardian reports.

Speaking to AP, Marc Cooke with the advocacy group Wolves of the Rockies predicted that Gianforte and the state would receive criticism for not putting protections for the Yellowstone wolves. "People love these animals, and they bring in tons of money for the park."

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Evening Roundup, May 28...plus a special thank you to our Contrarian family Featuring Jen Rubin, Katherine Stewart, Brian O'Neill, Jenni...