Epitaph: Where Once RSN Existed

There are no guarantees in this life. Right now, we have a vibrant publication with a voice for social justice. To ensure that RSN continues, I am entrusted with raising enough funding to meet the organization’s obligations.

It falls to me, and to you.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The family might have thrived indefinitely after Osama’s death but for the ambitions of Mohammed bin Salman.

Bin Laden has roots in Jeddah, the Red Sea port city where, in 1931, his father, Mohammed bin Laden, a poor migrant from Yemen, founded and built a construction company that grew eventually into the largest in the kingdom, as part of the family’s flagship conglomerate, the Saudi Binladin Group. It built palaces, renovated mosques in the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and expanded across the Arab world. And, of course, it was part of the upbringing of Osama bin Laden, another of Mohammed’s sons, who studied business administration and apprenticed at the family firm before taking up jihad full time.

Bakr bin Laden’s recent travails offer a coda to the story of 9/11’s aftermath inside Saudi Arabia. The recent fall—or at least the economic punishment—of the bin Laden family has coincided with the rise to power of M.B.S., but it also reflects the twilight of the sprawling generation to which Osama belonged. It is a story of privilege, succession, and wildly diverse outlooks within a family whose name is an indelible part of American history.

Mohammed bin Laden died in a private-plane crash, in Saudi Arabia’s southern desert, in 1967, at the age of about sixty. He left behind fifty-four children, whom he had fathered by more than twenty wives. At the time of Mohammed’s death, his eldest son, Salem, was twenty-one and living in London, where he wore jeans and played rock-and-roll guitar and harmonica. Although hardly prepared for his new responsibilities, Salem took charge of the family and its businesses in the manner of a sheikh, and ran it as his fiefdom. He proved to be a charismatic globe-hopper who piloted Learjets, flew hot-air balloons and ultralights, and sang corny tunes (“On Top of Old Smokey” was a favorite) on just about any stage that he could find. Salem bought property in England and in the United States, including a home near Disney World, west of Orlando. In Saudi Arabia, he charmed the family firm’s most important patron, King Fahd, who reigned from 1982 until he suffered a debilitating stroke, in 1995. Fahd effectively controlled contracts that were important to the Saudi Binladin Group, and Salem became part of his court.

In the nineteen-eighties, Salem visited Osama, his younger half brother, in Pakistan, where he had joined the mujahideen fighting against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. At the time, Osama’s participation in that war, which had the backing of both King Fahd and Ronald Reagan’s C.I.A., was an uncontroversial matter. But, in 1988, Salem died in a freak ultralight accident outside San Antonio. He was forty-two. His death unmoored the bin Ladens, and, in the aftermath, Osama became increasingly radical and defiant of the Al Saud royal family, on the ground that it wasn’t Islamic enough and was too close to the United States.

During the several years that I spent researching a book about the bin Ladens, many family members and friends told me that Salem had had a way of keeping Osama in line, and that after his death Osama’s ego and sense of entitlement to leadership swelled. He seemed to believe that he was qualified to run the family after Salem. But he was not from the inner circle of Mohammed’s children. He was the only child of a teen-age girl whom his father had married and divorced hastily in the late nineteen-fifties. Osama was by no means the only child of Mohammed’s in this position, as his father married and divorced many women. Mohammed did fully enfranchise all his children as his heirs, and made them eligible for what was, during the nineteen-seventies, a tax-free allowance of several hundred thousand dollars a year. But Osama was not among the oldest or the best-connected of his father’s sons. In the end, Bakr, one of Salem’s full brothers, took charge of the family.

Bakr had lived in the United States for several years, where he obtained a degree in civil engineering from the University of Miami. Soon after he took over the family and the company, the Saudi government moved to expel Osama and strip him of citizenship, because of his unrelenting criticism of the royal family. Bakr correspondingly removed him as a shareholder in the family firms. In 1991, Osama went into exile, settling in Sudan and, later, in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, from where he plotted 9/11.

Bakr’s greatest achievement as the family patriarch was to preserve access to lucrative royal contracts after King Fahd’s stroke. The new de-facto ruler was Fahd’s half brother Abdullah bin Abdulaziz, the crown prince. After 9/11, Abdullah protected the bin Ladens, refusing to punish them for Osama’s terrorism or to blame them for the ignominy that Saudi Arabia suffered, particularly in the United States. The contracts kept coming. Bakr pulled this feat off “thanks in part to a keen understanding of what the Al Saud wanted,” just as his father and Salem had done, the Wall Street Journal reporters Bradley Hope and Justin Scheck write in their book, “Blood and Oil.” “If that meant building a palace for a new wife in a matter of months, they’d get the job done. Payment could come much later or never at all; the Bin Ladens wouldn’t make a peep.”

Osama certainly had a few sympathizers among his many brothers and sisters, but the majority of them abhorred his violence and resented the damage he caused them. His killing, in Pakistan, by U.S. Navy SEALs, in May, 2011, relieved the family of any further association with his millenarian terrorism. The bin Ladens might have thrived indefinitely after Osama’s death but for the ambitions of M.B.S., who sought to marginalize rival factions in the Saudi élite while simultaneously authoring economic and social reforms, establishing himself as the most visible and powerful leader in the kingdom. Early in his rise, in 2015, according to a Reuters investigation, the crown prince met with Bakr and asked to become “a partner” in the Saudi Binladin Group, and suggested that Bakr take the company public by listing shares on the Saudi stock exchange. On September 11th of that year, one of the firm’s cranes fell in Mecca, killing more than a hundred people and injuring some four hundred. The Saudi government temporarily suspended contract awards to the bin Ladens. (The eerie coincidence of the date of the accident is one of a number of odd resonances in the bin Laden family history; another is the recurrence of traumatic plane crashes.)

In 2017, M.B.S. staged a broad crackdown on businessmen, in the name of fighting corruption. Bakr and two of his brothers, Saad and Saleh, were among the hundreds of wealthy Saudis detained, many of them at the Ritz-Carlton in Riyadh, where they had to answer allegations of financial crimes. According to the Reuters investigation, the authorities ultimately seized deeds to bin Laden family homes, private jets, luxury cars, cash, and jewelry.

The next year, a Saudi-government-owned entity took a 36.2-per-cent stake in the Saudi Binladin Group. Then the coronavirus pandemic hit, and the company struggled amid the accompanying economic shocks. There were layoffs and missed payrolls; last year, the firm reportedly hired Houlihan Lokey, the investment bank, to restructure its whopping fifteen-billion-dollar debt load.

The bin Ladens figure in our history as a family because their collective experience of a borderless, technology-enabled, and media-saturated world inadvertently inspired in Osama a vision of terrorism that would exploit the world’s growing connectivity. His innovations as a terrorist—his adoption of a satellite phone to run cells on several continents, and his use of fax machines and satellite TV networks to defeat the censors of Arab authoritarians—arose from his upbringing in a family that embodied the opportunities and the stresses of modernization in Saudi Arabia.. He was an obscurantist who understood globalization.

Salem and then Bakr bin Laden molded that era among the wider bin Laden clan. The family’s difficulties today still attract coverage in the financial press, but, if there is any benefit in the reversals that M.B.S. has forced upon the bin Ladens, it may be that they will hasten their retreat from prominence and allow them, over time, some measure of anonymity. They may fade away, but the family will always offer a more interesting story of Arabia in the oil age than the notorious member who defiled their name.

Anti-abortion demonstrators listen to former president Donald Trump as he speaks at the 47th annual 'March for Life' in Washington, DC. (photo: Olivier Douliery/AFP/Getty Images)

Anti-abortion demonstrators listen to former president Donald Trump as he speaks at the 47th annual 'March for Life' in Washington, DC. (photo: Olivier Douliery/AFP/Getty Images)

Judges nominated by Donald Trump have staked out strong anti-abortion stances in their short time on the bench.

When the Supreme Court allowed Texas’s 6-week abortion ban to take effect on Sept. 1 — with three of Trump’s nominees in the five-justice majority — it was widely seen as the latest example of that bargain paying off for anti-abortion advocates.

But the Supreme Court’s refusal to intervene was the last in a series of legal dominos that had to fall for the Texas law, SB 8, to go into effect. How the fight unfolded before it reached the justices showed the lasting reverberations of a successful push by Trump, Senate Republicans, and the conservative legal movement to reshape the federal judiciary. Federal appeals judges confirmed to lifetime appointments since 2016 — including two members of the three-judge panel that teed up the SB 8 legal fight for the Supreme Court — have staked out anti-abortion stances and sided with states trying to restrict access to the procedure.

The Justice Department filed a new constitutional challenge to SB 8 just over a week after it took effect. Regardless of what happens next in the federal district court in Austin, the Biden administration will face the same barrier as the abortion providers who unsuccessfully tried to stop the law before Sept. 1: the conservative US Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit.

Trump deepened conservative majorities in the 5th Circuit and other appeals courts that cover Republican-led states where lawmakers have either passed restrictive abortion laws or are mulling new ones. Federal judges are not bound to the policy preferences of the president who appointed them, but they are more likely to align with their politics and values, especially on the appeals courts.

Two weeks before SB 8 took effect, Trump-appointed judges on the 5th Circuit joined a ruling that upheld a different Texas law that restricted abortions. Earlier this year, judges nominated by Trump wrote opinions or joined the majority in validating an Ohio law that prohibits pregnant people from obtaining an abortion on the grounds that the fetus is diagnosed with Down syndrome and permitting Tennessee to enforce a 48-hour waiting period before a person can get an abortion. During the early months of the pandemic in 2020, Trump-nominated judges sided with states that sought to restrict abortions and other medical procedures on the grounds that healthcare providers needed to conserve protective equipment.

“The Trump circuit judges have been just as anti-abortion as he promised,” said Elliot Mincberg, a senior fellow at the liberal advocacy group People for the American Way, who tracks rulings made by Trump-nominated judges.

Most cases don’t reach the Supreme Court, which means circuit courts are often the last stop. It’s why Trump and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, then the majority leader, prioritized filling these powerful seats. That effort received significant financial and organizational support from conservative groups, including anti-abortion advocates.

The Biden administration is swiftly moving to fill open seats in the lower courts. But lifetime appointments mean the administration can’t do anything until a judge leaves or dies; Republican-appointed judges are far less likely to retire with a Democrat in office, and vice versa.

The 5th Circuit, which covers Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, had a conservative reputation before Trump took office. Trump bolstered the bench, nominating six of the 17 active judges; the court has 12 judges confirmed under Republican presidents. Those new members included Judges Stuart Kyle Duncan and Kurt Engelhardt, who were part of the three-judge panel that entered the order that allowed SB 8 to take effect.

Texas abortion providers filed a constitutional challenge to the law after Gov. Greg Abbott signed it in May. SB8 bans nearly all abortions after fetal cardiac activity can be detected, usually around the sixth week of a pregnancy. Pregnancy terms are counted from the first day of a person's most recent period, so week 6 is typically two weeks after a missed period, which is when many people realize they're pregnant. The law deputized private citizens to enforce the law by allowing them to sue anyone they suspected of performing an abortion or aiding a pregnant person in obtaining one; it provided hefty financial incentives and minimized the legal risk for filing a claim.

US District Judge Robert Pitman — the same judge now assigned to the Justice Department’s case — had been poised to hold a hearing on Aug. 30 about whether to block SB 8 while that case was pending. The defendants, who had unsuccessfully argued to have the suit tossed out, asked the 5th Circuit to intervene. On Aug. 27, Judges Duncan, Engelhardt and Edith Jones, a Ronald Reagan appointee, entered a one-paragraph order putting all district court proceedings on hold.

The abortion providers raced to the Supreme Court, petitioning the justices to lift the 5th Circuit order or halt the law themselves. Come midnight on Sept. 1, SB 8 took effect — not because the justices did something, but because they were silent and didn’t disturb the 5th Circuit’s order. It would be another 24 hours before the Supreme Court released its own 5–4 order confirming the decision to let SB 8 stand while the abortion providers’ case played out in the lower courts.

On Sept. 10, the 5th Circuit released another order from the same three-judge panel, which kept the case on hold while the court fully considers an appeal of Pitman’s early rulings that would allow the abortion providers’ lawsuit to go forward.

Civil rights groups had opposed the nominations of Duncan and Engelhardt in part because of their anti-abortion backgrounds. Before becoming a judge, Duncan worked in state attorneys general offices in Texas and Louisiana as well as for the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a conservative legal advocacy group, where he helped lead the fight against the contraception mandate in the Affordable Care Act. Engelhardt had been a member of a group of lawyers opposed to abortion in Louisiana before he became a district judge in the state in 2001.

Last year, Duncan joined the majority of a 2–1 order that allowed Texas to temporarily halt abortions as part of an executive order from Abbott that paused nonessential medical procedures during the pandemic.

Trump-nominated 5th Circuit judges have sided with Texas and anti-abortion advocates in earlier cases over the state’s efforts to restrict access to the procedure. On Aug. 18 — as the fight over the 6-week abortion ban was unfolding— the 5th Circuit ruled that Texas could enforce a 2017 law that prohibited doctors from performing a type of abortion method; providers had argued it would significantly limit options for pregnant people in their second trimester. Judge Don Willett, a Trump nominee, cowrote the majority opinion.

Judge James Ho, another Trump nominee, joined the majority and wrote separately to emphasize his support of the 2017 law. He’s made his anti-abortion position clear in several cases. In a 2018 concurring opinion, he described it as a “moral tragedy.”

When the court upheld an injunction blocking Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban in 2019, Ho wrote separately that he was “forced” to join his colleagues in reaching that result because of US Supreme Court precedent, but he wasn’t happy about it. He blasted the federal district judge who originally blocked the Mississippi law. (The justices are set to hear the case, which could have nationwide consequences, in the next term.)

“The opinion … displays an alarming disrespect for the millions of Americans who believe that babies deserve legal protection during pregnancy as well as after birth, and that abortion is the immoral, tragic, and violent taking of innocent human life,” Ho wrote.

In the 6th Circuit, which covers Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee, Judge Amul Thapar — Trump’s first federal appeals court nominee — has emerged as a leading anti-abortion voice on that bench. On Sept. 10, that court issued a decision blocking a Tennessee law that imposed a set of early-term abortion bans. Thapar joined the decision but wrote separately to say that he wasn’t happy about it. The court was bound by Supreme Court precedent to strike down any previability abortion ban, he acknowledged, but he then urged the justices to change that.

“Roe and Casey are wrong as a matter of constitutional text, structure, and history,” he wrote. “By manufacturing a right to abortion, Roe and Casey have denied the American people a voice on an important political issue.”

Judge Ralph Erickson of the 8th Circuit, a Trump nominee, issued a similar call in January for the Supreme Court to revisit the precedent that protects the right to an abortion before viability — the point in a pregnancy when a fetus is considered able to survive outside the womb, usually around 24 weeks. The 8th Circuit covers Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska.

“By focusing on viability alone, the Court fails to consider circumstances that strike at the core of humanity and pose such a significant threat that the State of Arkansas might rightfully place that threat above the right of a woman to choose to terminate a pregnancy,” Erickson wrote.

Other judges have noted the anti-abortion positions of their newest colleagues. In February, the 6th Circuit issued a 2–1 decision blocking Tennessee’s 48-hour waiting period for the procedure. Thapar dissented. Judge Karen Nelson Moore, a Bill Clinton nominee, called out Thapar’s “zeal to uphold what appears to be yet another unnecessary, unjustified, and unduly burdensome state law that stands between women and their right to an abortion.”

The full court agreed to rehear the case, and last month it issued a 9–7 decision allowing Tennessee to enforce the waiting period. All six of Trump’s nominees to the court were in the majority; Thapar wrote the opinion.

Attorney General Merrick Garland at a Sept. 9 news conference. (photo: Samuel Corum/Bloomberg News)

Attorney General Merrick Garland at a Sept. 9 news conference. (photo: Samuel Corum/Bloomberg News)

Garland announced the changes during an online speech to the International Association of Chiefs of Police, culminating a four-month Justice Department review aimed at bolstering public confidence in federal efforts to rein in unconstitutional and abusive policing.

Since he was appointed to the nation’s top law enforcement job by President Biden earlier this year, Garland — a former federal appeals-court judge and Supreme Court nominee — has launched sweeping “pattern or practice” investigations of police departments in Minneapolis, Louisville and Phoenix.

Such probes can result in federal intervention, in the form of a court-approved consent decree that sets a detailed reform plan. Local political leaders, police chiefs and law enforcement unions have complained that the plans often stretch on years longer than anticipated, harming police morale and frustrating community residents.

Monitoring teams — usually composed of former police officials, lawyers, academics and police-reform consultants — have typically billed local taxpayers between $1 million and $2 million per year. Some consultants have served on federal oversight teams in more than one city at the same time, drawing criticism over conflicts of interest.

“It is also no secret that the monitorships associated with some of those settlements have led to frustrations and concerns within the law enforcement community. We hear you, and we take those concerns seriously,” Garland said.

He emphasized that “monitors must be incentivized to efficiently bring consent decrees to an end. Change takes time, but a consent decree cannot last forever.”

Under the new rules — outlined in a nine-page memo from Associate Attorney General Vanita Gupta, who oversaw the review — monitoring teams would be subject to unspecified term limits set before their hiring, as well as periodic performance reviews by the federal judge in charge of the settlement, who could make changes.

The monitor would be allowed to continue past the negotiated term limits only through a reappointment from the judge, according to the memo.

The monitors would have to meet federal standards before being hired and undergo training once on the job, and they would be restricted from serving as a principal monitor in multiple localities simultaneously.

After five years, the judge would conduct a termination hearing to determine whether the federal oversight could be lifted or, if not, determine specific ways to help the jurisdiction reach full compliance, officials said.

Another rule would allow the Justice Department and the judge to slim down the scope of the consent decrees — which typically mandate that local jurisdictions meet hundreds of requirements before the federal oversight is lifted — to make them less onerous as law enforcement agencies demonstrate progress.

That change would hand back greater autonomy to local agencies in some areas, even as the federal monitors continue to ask for improvements in others.

Justice Department officials said they hope the new rules help jurisdictions feel as though the progress they make has been recognized, which could help keep them motivated.

Law enforcement groups reacted favorably to the changes.

“Pattern or practice investigations are serious business, and if the Justice Department conducts such an investigation and finds areas that require remedy, then it’s critically important that the remedy is effectively administered,” said James Pasco, executive director of the National Fraternal Order of Police. “Unfortunately, that hasn’t always been the case over the years, in every instance. These changes go a long way in improving the manner in which public safety is enhanced in cities large and small.”

Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, said his group has lobbied for nearly two decades for the Justice Department to provide greater oversight of federal monitors.

“This memo addresses many, if not all, of the major concerns we have had,” Wexler said. “This will help restore credibility into this process.”

Some of the new requirements have been tried in existing consent decrees, including in Baltimore. But now they will be mandatory in all new agreements, starting immediately, officials said.

Garland ordered the review of federal monitors in April when he released a memo restoring the agency’s ability to pursue consent decrees, three years after the Trump administration banned the strategy. In 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said he viewed the intervention into local jurisdictions as federal overreach.

Garland’s aides have called consent decrees an important tool to force changes among some of the nation’s most unaccountable law enforcement agencies. But the efforts have achieved mixed results, often moving more slowly than civil rights groups and police-reform advocates have demanded.

The Justice Department spent more than 12 years overseeing police-reform efforts in Los Angeles, 11 in Detroit, nearly a decade in New Jersey and seven years in D.C. and Prince George’s County, Md.

Among ongoing agreements, federal authorities are still monitoring efforts that began in the U.S. Virgin Islands in 2009, in Seattle in 2012, in New Orleans and Puerto Rico in 2013 and in Portland, Ore., and Albuquerque in 2014.

Gupta said her team conducted more than 50 meetings with stakeholders, including local political leaders, law enforcement officials, former and current monitors and community members. Her memo emphasized the importance of community input in the consent decree process and instructed monitors to engage with residents, including through the use of town-hall-style meetings and social media.

Officials said Gupta and Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke, who oversees the department’s civil rights division, will convene another meeting with stakeholders within 90 days to begin developing the new training guidelines and assessment tools to help jurisdictions measure progress.

In a statement, Gupta called consent settlements “vital tools in upholding the rule of law and promoting transformational change,” and she said the Justice Department “must do everything it can to guarantee that they remain so by working to ensure that the monitors who help implement these decrees do so efficiently, consistently and with meaningful input and participation from the communities they serve.”

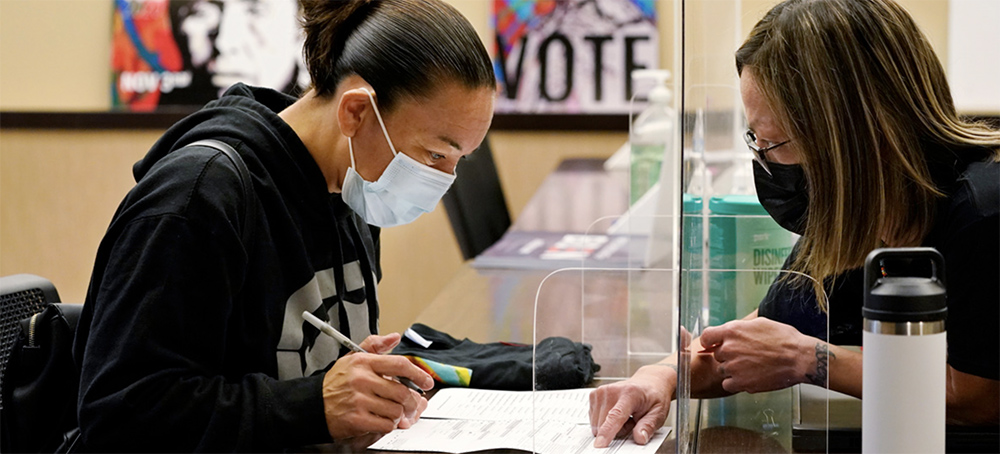

Lummi Tribal member Patsy Wilson fills out her ballot with assistance from volunteer Kelli Jefferson on Nov. 3, 2020, in Lummi Nation, Washington. NAVRA will allow tribal members to register, pick up and drop off their ballots at designated tribal buildings. (photo: Elaine Thompson/AP)

Lummi Tribal member Patsy Wilson fills out her ballot with assistance from volunteer Kelli Jefferson on Nov. 3, 2020, in Lummi Nation, Washington. NAVRA will allow tribal members to register, pick up and drop off their ballots at designated tribal buildings. (photo: Elaine Thompson/AP)

Indigenous communities face disproportionate barriers to voting, but the act would help protect this important right.

The bipartisan legislation follows the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on a prominent voting rights case. In Brnovich v. DNC, the court upheld two Arizona voting policies that disqualify any ballot cast in the wrong precinct, as well as a 2016 law that made it a felony for anyone but a family or household member or caregiver to return another person’s mail ballot. Ballot harvesting or collecting is often used by get-out-the-vote groups to increase Indigenous turnout. Activists and attorneys say the July ruling will make it harder for people of color — especially Indigenous populations — to vote.

NAVRA seeks to fulfill the federal government’s trust responsibility to protect Native Americans’ right to vote by tackling the unique challenges that Indigenous communities face. “We have to address ongoing discriminatory policies at the state and local levels,” Native American Rights Fund staff attorney Jacqueline De León (Isleta Pueblo) said. “We need a federal policy that sets a baseline of access and prevents continuing abuses.”

These six provisions of the proposed legislation are intended to increase Indigenous voters’ access to the ballot box.

1) NAVRA improves access to voter registration, polling places and drop boxes in Indian Country.

The law requires states to designate at least one polling place and registration site for both state and federal elections in every precinct in which tribal voters reside on tribal lands. NAVRA also requires federally funded or operated facilities, such as Indian Health Services, to serve as designated voter registration sites.

2) It mandates the acceptance of tribally or federally issued IDs where IDs are required.

Some states have restrictive voting ID policies that place a disproportionate hardship on Indigenous voters. In North Dakota, for example, the Spirit Lake Nation and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe sued over a state policy that required voters to present identification that includes a residential street address, even though many tribal members live on reservations that lack residential street addresses or have to use P.O. boxes for mail service. NAVRA authorizes the use of tribal IDs for voting purposes.

3) It permits tribes to designate buildings to use as addresses for registration.

This would allow tribal members without a residential address, stable address or mail delivery to register, pick up and drop off their ballots at designated tribal buildings.

4) The law will establish Native American voting task forces.

NAVRA would establish state-level voting task forces to address some of the issues unique to Indian Country, including inadequate broadband access and the lack of mailing addresses. It would also increase voter outreach and help with voter identification and language assistance.

5) It requires pre-approval of any changes in election procedures.

States would not be able to reduce, remove or consolidate voting access on tribal land without first obtaining tribal consent, U.S. attorney general consent, or an order from the D.C. Federal District Court.

6) NAVRA also mandates culturally appropriate language assistance.

The law would allow language access to be provided orally if written translation of a tribe’s language is not culturally permitted.

Learn more about the Native American Voting Rights Act of 2021.

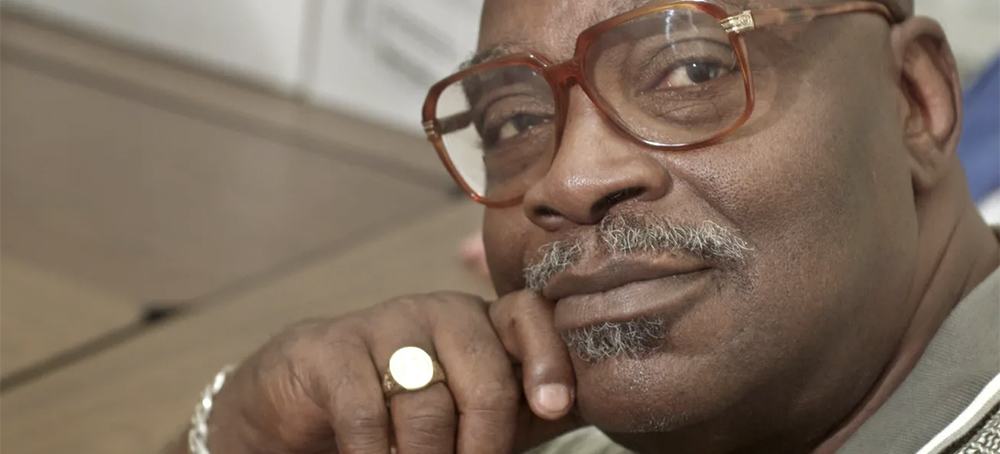

Frank "Big Black" Smith. (photo: Shawn Dowd)

Frank "Big Black" Smith. (photo: Shawn Dowd)

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman.

Today we spend the hour marking the 50th anniversary of the deadliest prison uprising in the history of the United States. A state cover-up of the mass killing began that day. We will air long-suppressed testimony of survivors who were tortured by guards, and speak with one of the survivors, as well as a negotiator and a filmmaker who helped uncover what really happened.

And a warning to our listeners and viewers: Today’s show will include graphic, painful, brutal descriptions and images.

Yes, 50 years ago today, September 13th, 1971, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller waged war on the men held in Attica state prison in western New York, ending a four-day prisoner uprising.

The rebellion started on September 9, 1971, when prisoners overpowered guards and took over much of Attica to protest the conditions at the maximum-security prison. At the time, prisoners spent most of their time in their cells and got one shower per week.

Days of tense negotiations followed in the prison yard. The rebellion was on its way to being resolved through diplomacy. But on the morning of September 13th, Governor Rockefeller ordered state troopers to storm the prison. Through a haze of tear gas, police opened fire, killing 29 prisoners and 10 hostages. Three prisoners and a guard were killed by prisoners in the days before the retaking. In all, there were 43 deaths.

This is a trailer for the new documentary called Betrayal at Attica on HBO Max that examines the hidden history of what really happened in the Attica uprising through the men who lived it, the Attica Brothers, and their defense attorney, Elizabeth Fink, who died in 2015. The film draws on an archive of evidence that was once owned by Liz Fink, available now for the first time.

ELIZABETH FINK: I stole all this stuff. I shouldn’t say that. I expropriated it from them as the chief counsel for the prisoners, who were the plaintiffs. They were going to destroy it. We’re at this point right now where they are refusing to admit they have all these files, and they are lying about what they have.

LOUDSPEAKER: Those of you who have not done so, surrender peacefully. You will not be harmed. Place your hands [inaudible] on your head.

ELIZABETH FINK: It’s all going to be blown up, because I took it all, and also because of you.

AMY GOODMAN: In the documentary Betrayal at Attica, prisoners describe how they were tortured when the uprising was brutally suppressed. These are actually deposition interviews from the 1974 civil suit against the state of New York filed by the Attica Brothers Legal Defense.

In this clip, Frank “Big Black” Smith, who became a spokesperson of the prisoners and helped protect the hostages, as well, describes what happened to him. A warning: His answer and the images that accompany it are graphic, brutal, emotional.

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: I was made to crawl after I was knocked to the ground, pushing me, kicking, calling me all kind of [bleep], telling me to walk, telling me to run, drug, dragged.

ATTORNEY: Where did they take you?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: They took me to —

ELIZABETH FINK: Want a handkerchief?

ATTORNEY: Took you to where?

ELIZABETH FINK: You’ve got to let him do his thing now. Want a break? Take some water?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Took me, and they made me lay on the table in the yard, and they beat my on my nuts, threatened me and dropped cigarette butts on me and hot shells on me and spit on me.

STENOGRAPHER: Hot what? I’m sorry.

ELIZABETH FINK: Shells.

STENOGRAPHER: OK.

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Telling me they was going to cut my testicles and my genital out. That’s what was happening to me.

ATTORNEY: OK. How long did that go on?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: A long time, three to six hours, all day.

ATTORNEY: Was the football under your — under your chin?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Under my chin, yes.

ATTORNEY: All day?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Yes.

ATTORNEY: All day?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Yes.

ATTORNEY: The shells were on your chest all day?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: All during — I was moving, trying to get them off me, and the cigarettes off me. A bunch of times, they’d beat, call me a bunch of names, because my legs was dead. They was numb. I couldn’t walk. They finally drug me and took me to the hallway, and I had to go through the same thing everybody else was going through, because I was about the last person out of the yard. They made me run through the gauntlet.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Frank “Big Black” Smith, who survived the brutal state suppression of the 1971 Attica uprising 50 years ago today, in a clip from the new documentary, Betrayal at Attica, which brings to light new evidence about what really happened. Big Black said the officers put a football under his chin and told him if it dropped, they would kill him. He went on to fight for justice in a civil suit for prisoners and also pushed for compensation for the guards’ families. Big Black died in 2004.

For more, we’re joined by Tyrone Larkins. He was incarcerated in upstate New York’s Attica prison at the time of the uprising. He was 23 years old. He was shot three times. After 29 years of incarceration, Tyrone was released via parole in 1997 with a college education through Marist College. He’s also featured in a Showtime documentary, brand new, called Attica by Stanley Nelson, which just premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Tyrone Larkins, welcome to Democracy Now! This is a painful time, I’m sure, for you, even now, half a century later. Can you start off even before September 9, 1971, when the prisoner rebellion began, and describe the prison conditions at Attica and the political climate at the time? What led to this uprising?

TYRONE LARKINS: Give me a second. Hearing the overview of Frank’s voice and what happened, it — wow — it took me back 50 years ago today. Let’s make note that this happened exactly 50 years ago today on a Monday morning. And as I was on my way to where I was going to do this taping at, I seen a cloudy sky, and it reminded me of September 13th, 1971. And so, I’m a little discombobulated now, but I am ready to go. And your question was: How did it all start? Am I correct?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes. How did it all start, even before September 9th, the beginning of the prisoner uprising?

TYRONE LARKINS: OK. I got to Attica. I was transferred to Attica in January 1971 from Sing Sing, Ossining, which was known then as Ossining Correctional Facility. And when I got into Attica, I seen that this was — I mean, from the time I got off the bus, me and about 40 other people that was transferred seen that this was the roughest place I’ve ever seen in my life.

The only time the prison guards spoke to us was to give us a description of the institution, to tell us when you bang on — they bang on the wall once with their stick, it means go, and when they bang on the wall with their stick twice, it means to stop. And that basically was the extent of the conversation.

You can feel the roughness and the tightness of the facility in the air, I mean, after coming from Sing Sing, which was relatively — I wouldn’t say open, but a little more humane.

When I finally got settled into the facility, at my cell, I was given a roll of toilet paper, a bar of soap, and was told that this roll of toilet paper would have to last me for one month and that I will possibly get a second bar of soap in two weeks’ time. And that was it.

I should say at this juncture that Attica, prior to the disturbance itself — and I use the word “disturbance” loosely, because we was in the climate of international things that was happening throughout the world. First of all, from an ethnic pride sense, a lot of the African American prisoners, such as myself, adhered to James Brown was singing — “Say it loud: I’m Black, and I’m proud” — that gave us a racial identity, as opposed to be adhering to what a nigger is and stop doing what niggers do. And that made us feel good. Then you had the “Hell no, we won’t go” slogans was permeating all over the world in regards to the Vietnam situation. So, we was getting a certain sense of politicalization and ethnic reality at the same time. And we started adhering to things of that nature. And this was counterculture to the powers that be in Attica Correctional Facility.

And to give you an example of that, the first time I seen it fully in full operation, the racial divide, was in the summer of 1971. It was a hot day. And the officers came out into the yard — I was locking in B Block at the time — and had a wheelbarrow full of ice and emptied the wheelbarrow full of ice on the ground and said “white ice,” which meant that that ice was for the white prisoners. And after they picked their ice up, a second wheelbarrow was rolled to the yard, and the officers dumped it on the ground and said “black ice,” and that was for the Black and — well, let me say, people of color prisoners that was locked up in Attica at the time. And this caused a definite racial divide.

However, I would say, in later part of June, early part of July, when ice was thrown on the ground and it was depicted white ice and black ice, nobody in the yard would pick it up — nor white inmates, nor Black inmates, nor Hispanic inmates, nor Indian inmates. Nobody would pick up any ice that was depicted for a racial people. As a matter of fact, the fact that the ice was thrown on the ground, as opposed to being left in the wheelbarrow, was an insult in itself.

In June — excuse me, ratcheting it up to the end of July — or, August, I should say, pardon me, when George Jackson was killed, was murdered, as we would like to call it, in San Quentin prison, on the so-called information that he had a gun in his hand and was trying to escape, that created a unified concern for basically everybody that was in Attica. As a matter of fact, the day after he was killed, it was organized that everybody in the facility would not eat. We had a hunger strike. We went to the mess hall as we were supposed to, picked up the silverware or plastic silverware as they gave out, but nobody picked up any food. And it was extremely quiet. You didn’t hear no noise, no chatter, no nothing. And when it was time to go, we left out of the facility, the eating facility, which was known as the mess hall.

On September 8th, 1971, two guys that was locked up was horsing around in the yard, in A Block yard. And the officers rushed over to them to threaten them to stop it, so forth, etc. And a circle of inmates, a gathering of inmates, got around the officers and said, “You’re not doing anything to anybody.” And they backed off. Well, later on that night, the men, the two men who was horsing around, was literally dragged out of their cells and was beaten all the way to a special housing unit. And you could hear the cries throughout the A Block yard.

Well, the next day, September 9th, the guys that was coming from — that was on the same jail company or housing company where these two guys was pulled out of, was coming back from the mess hall, and they was told that they was not going to the yard for their morning recreation. They was going back to the cell blocks. And that was the spark that started the whole thing.

And they took control of A Block, and they took control basically of the facility. I personally was locking in B Block and was working in the metal shop. And the next thing I know, I seen guys from A Block, B Block, C Block in the metal shop. And I knew it was a full-scale — well, we called it a prison riot, but let me say that it elevated from a prison riot to a prison demonstration. And I know those words, sometimes people will not like to interchange it, but it was, because the mere fact that we, as people that was confined, took on the situation of electing our best and our brightest to represent us, to talk to the administration of the powers that be of the problems in Attica, and that we had some hostages also.

And we adhered to all the factors that was involved. There was no problem in that yard. And sooner rather than later, we had observers come in, because we asked for people from the outside to come into the prison itself. And their level of participation ratcheted up from being an observer to being our negotiators with the powers that be. Well, now, we know that didn’t work out too well, because of what happened on Monday, this Monday, the 50 years ago, exactly on the 13th — exactly on a Monday the 13th, September 13th, 1971.

I woke up in the morning after a fitful night of sleep because the mist and the rain came. And it was a mist and a rain over the yard that morning. And the next thing I know — I guess it was 8:30, 9:00 — I heard a big helicopter hovering, and I seen it hovering over the yard. And the announcement came: “Put your hands on your head. Lay down. You will not be harmed.” And there was some gas that they released from this helicopter that literally knocked me to my knees, and it cleaned my sinuses out.

But at the same token, the ground all around me was jumping and shaking. And I’m thinking I was in some type of a movie or something. But what was jumping all around me was bullets. And I took three shots. And I fell out, but then I regained my consciousness. Somebody — it was a correction officer or a state trooper — was kicking me in my side. And I was told, “Get up and start crawling,” and “Let’s go to the exit, to A Block door.”

And once I got literally thrown into A Block yard by correction officers or national guardsmen or state troopers — I don’t know who it was — I was thankful to see that there was people with stretchers that came and grabbed me by the nape of my neck and pulled me out of a crowd of other individuals who was laying on top of me and on the side of me, and put me on the stretcher and took me out the yard.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to —

TYRONE LARKINS: I’m sorry.

AMY GOODMAN: Tyrone, we thought at this moment we would play a clip from Betrayal at Attica —

TYRONE LARKINS: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: — which is the actual video depositions of prisoners, like yourself, and what happened to them after the state troopers opened fire, killing 39 men — among them, prisoners and guards. These clips are extremely graphic, and so are the images it shows.

MICHAEL HULL: In 1974, Attica Brothers Legal Defense filed a $2.8 billion civil suit against the state of New York for damages on behalf of 1,281 inmates. After years of delay by the appointed judge, pretrial discovery depositions got underway in 1991. These tapes are from that deposition. They have never been available to the public.

GEORGE ALEXANDER SHORTS JR.: George Alexander Shorts Jr.

ATTORNEY: Do you recall where you were on the morning of September 13th, 1971?

GEORGE ALEXANDER SHORTS JR.: Yes.

ATTORNEY: Where were you?

GEORGE ALEXANDER SHORTS JR.: In Attica prison.

SURVIVOR 1: I was hit.

SURVIVOR 2: I was kicked in the side, the back and the buttocks.

SURVIVOR 3: My head was in the dirt.

SURVIVOR 4: I was kicked in the side. I was kicked in the hip, kicked in the back.

ATTORNEY: You had any inmates being kicked in A Yard?

WALTER DUNBAR: I don’t recall that.

SURVIVOR 1: I was hit in the testicles.

ATTORNEY: By what?

SURVIVOR 1: A shotgun.

ATTORNEY: Can you tell me about how many times you feel you were hit during that?

SURVIVOR 1: I couldn’t even say. All I know, I was hit. I was hit — what? You know, when you’re hit like that, you’re not trying to count. You know, you’re scared to death. I wetted on myself. I was hit in the head, the back, my arms, trying to block, in the lip.

ATTORNEY: Lip?

SURVIVOR 1: Face, yes.

ATTORNEY: Did you wear glasses at that time?

SURVIVOR 5: Yes, I did.

ATTORNEY: Did you have them on?

SURVIVOR 5: No, they had taken them and stomped on them.

SURVIVOR 2: Then my glasses was taken off me, stomped.

SURVIVOR 5: We were forced under gunpoint to crawl the length of the yard on your knees and elbows.

SURVIVOR 2: I was told to take off all of my clothes. I was hit and told to run, [bleep].

SURVIVOR 1: Then he put the gun to my head, cocked the gun and said, “[bleep], I’m gonna kill you.” And that’s when I started pleading for my life.

SURVIVOR 2: There was a correction — two correctional officers there telling me the same thing: “Run, [bleep], run.” And that’s exactly what I did.

SURVIVOR 1: And I was told, “When I hit this door with this stick, [bleep], you better start moving.” And when he hit the door, I started to move.

ATTORNEY: Did you hear what kind of language was being uttered in that yard?

WALTER DUNBAR: Emphatic language: “Get over there. Get down. Move along.” That sort of thing.

ATTORNEY: Did it have, after it, words such as [bleep], when you said, “Get down there. Move along”?

WALTER DUNBAR: No, I didn’t hear that. If I did, I’d report it to you.

AMY GOODMAN: So, these were testimony in depositions. Tyrone Larkins, it is utterly painful. And in the documentary, Betrayal at Attica, it goes on and on, what happened to these men, and, of course, also your story that we’re hearing today.

TYRONE LARKINS: Yes. Yes. After going to the — well, actually, I laid on the stretcher with quite a few individuals in the yard that was between the giant wall, the hospital and special housing unit. And as I was coming in and out of consciousness, because the pain was — it was great, the pain was great — I seen a line of men that was being escorted or ran like cattle and being beaten by sticks, naked, going to a special housing unit, which is called HBZ. And at the last one I seen, I seen one guy, he fell, and a bunch of correction officers was over him and beating him until he got up and continued to ran — to run, rather, I should say. Sorry, I’m a little emotional, and my words may be getting a little jumbled, because I’m going directly back 50 years.

And then I was taken to the hospital. And I thank god for that, because the medical personnel that took care of me, it was a doctor — I forget his name. I know he mentioned it. And he said he was from Meyer Memorial Hospital. And he told me, “Look, I’m going to try to fix you up, but let me look at the extent of your wounds and see what can be done, to see if you need to go to the outside hospital or if I can do local procedures here.” Well, I guess he felt that he can do the local procedures there and in Attica, because I was taken immediately up to the hospital ward. And they started the preliminary examinations, things of that nature, and started the repairing or the rebuilding of myself.

AMY GOODMAN: Tyrone Larkins, we’re going to break. And when we come back, we’re going to be joined by one of the negotiators. Many believe if the negotiators had been able to continue their work without New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller calling on the state troopers to open fire, this could have resolved peacefully. Tyrone Larkins, formerly incarcerated at Attica prison, was shot by state troopers 50 years ago today, September 13, 1971. We’ll also speak with the HBO Max documentary filmmaker of the film Betrayal at Attica. Stay with us.

El Mozote, El Salvador, the site of a massacre during the country's civil war. (photo: Jose Cabezas/AFP/Getty Images)

El Mozote, El Salvador, the site of a massacre during the country's civil war. (photo: Jose Cabezas/AFP/Getty Images)

The judge investigating the 1981 El Mozote massacre has been fired by El Salvador’s government as the right-wing populist president, Nayib Bukele, consolidates power. For victims, survivors and their families, that means justice could never come.

Forty years after the massacre, former senior military officers, including the minister of defense at the time, have been facing charges ranging from kidnapping and rape to murder. The military and the Salvadoran elite have repeatedly sought to block any accountability for the massacre, and the current president, Nayib Bukele, a 40-year-old right-wing populist who is often compared to Donald Trump and reminds some of Hungary’s Viktor Orban, may have just succeeded. He has made no secret of his desire to terminate the investigation.

On Aug. 31, the legislature, controlled by Bukele’s party, fired every judge in the country older than 60. Guzmán is 61. Within El Salvador, the prevailing view is that one of the aims was to end the investigation.

Bukele’s decimation of the judiciary is his latest move to increase his power and presents a challenge to the Biden administration. “Human rights will be the center of our foreign policy,” the U.S. president declared in a speech on the same day, announcing the end of the Afghan war. It will be achieved through diplomacy, he said, not military might. The United States has had a long and complicated relationship with El Salvador for the past four decades, and it is not clear what sanctions Washington is prepared to invoke.

Bukele is not likely to buckle easily. In May, after the Supreme Court overturned several of his executive orders, the legislature dismissed five justices and replaced them with loyalists. In response, Vice President Kamala Harris tweeted that the United States had “deep concerns about El Salvador’s democracy.” Bukele answered with a string of tweets: “With all due respect,” he wrote, “we’re cleaning our house and this isn’t your responsibility.”

On Sept. 3, El Salvador’s Supreme Court ruled that Bukele may run for reelection in 2024, despite a term-limits provision in the constitution. He also touched off another controversy last week by adopting bitcoin as an official currency; since 2001, it has been the U.S. dollar. Many observers believe that this move is designed to cushion El Salvador’s economy in the event the Biden administration imposes financial sanctions.

The U.S. State Department condemned the “decline in democratic governance” in El Salvador and called on Bukele to respect “the separation of powers and the rule of law.”

The assassination in March 1980 of the country’s revered Roman Catholic prelate, Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero, by a right-wing death squad touched off a simmering revolution. Several leftist guerrilla and political organizations united under the banner of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) to bring to an end decades of rule by an alliance of the oligarchy and military. In the name of stopping the spread of communism, the United States backed the government, with hundreds of millions of dollars in economic and military aid.

In December 1981, the Atlacatl, a Salvadoran army battalion, pillaged, plundered and raped its way through El Mozote and several other peasant villages in the northeastern part of the country. The soldiers summoned villagers to the square and forced them to lie face down in the dirt. The old men were taken away, tortured for information about whether their sons had joined the guerrillas and then executed. Women were raped and executed. A few women with infants, along with adolescents, were forced into the convent behind the Roman Catholic Church. The soldiers fired on them and threw grenades. A forensic exhumation years later found the bodies of at least 143 individuals, 90% of them under the age of 12; their average age was 6.

The massacre was exposed by reporters from The New York Times and The Washington Post who arrived on the scene with a photographer weeks after it occurred. There were still bodies in the cornfields and in mud houses being chewed over by vultures. The Reagan administration denied that government troops had carried out the massacre. The American Embassy in El Salvador suggested that the guerrillas were to blame, and the administration’s conservative supporters claimed it was “guerrilla propaganda.” Classified U.S. documents released by the Clinton administration confirmed the role of the Atlacatl battalion.

The struggle for justice on the part of the survivors and the relatives of the victims has been arduous, marked by defeats, victories and more defeats. In 1991, the legal aid office of the Roman Catholic Church petitioned the court to conduct an investigation. When the court asked the Ministry of Defense for the names of the officers in charge of the operation, it was told “no information” about any “supposed operation” could be found.

Two years later, a peace agreement ended the decade-long civil war, and a United Nations Truth Commission concluded that the government was responsible for at least three-quarters of the 75,000 civilians killed during the war. Acting quickly, and without hearings, the National Assembly, controlled by the right-wing political parties, passed a sweeping amnesty law.

The victims challenged the law in the Salvadoran Supreme Court. They lost. In 2011, they filed a case with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In its 152-page opinion, the court said there was no dispute that “the Armed Forces executed all of those persons it came across: elderly adults, men, women, boys and girls, they killed animals, destroyed and burned plantations, homes, and devastated everything community-related.” As for the amnesty law, the court found that it was in contravention of the Salvadoran government’s “international obligation to investigate and punish the grave human rights violations relating to the massacres of El Mozote and nearby places.”

Armed with this decision, the victims went back to the Salvadoran Supreme Court. In 2016, it ruled the amnesty law invalid. Guzmán reopened the investigation and began taking testimony from survivors. (Although the case is often referred to as a trial, it is roughly the equivalent of what in the United States is called a preliminary inquiry, at the end of which Guzmán can either dismiss the charges or recommend that the men be criminally prosecuted.) Because Guzmán is one of the only judges in the region and has had a heavy load of civil and criminal cases, the El Mozote investigation has proceeded slowly.

Amadeo Sanchez told the judge that he was 8 at the time of the massacre and had survived by fleeing into corn and sisal fields with his father. They heard the shooting and screams of young girls being raped. When Sanchez returned to the village, he found the bodies of his mother and two siblings as well those of aunts, uncles and cousins. In one adobe house, he testified, he saw the body of a woman who had been shot in the head. Next to her was a 1-day-old boy. His throat had been cut, Sanchez told the judge, making a slicing motion with his hand. On the wall, soldiers had scrawled, “Un niño muerto es un guerrillero menos” — “One dead child is one less guerrilla.”

Another witness, Maria Rosario, told the judge that 24 members of her family had been killed, including her mother. When she testified, she looked at the defendants, who were sitting on folding chairs in rows. She wanted to scream “assassins,” she said in a 2018 interview. “But I couldn’t allow myself to do that because the judge was right in front of me. You just endure the pain that you feel.”

Bukele has been as determined as his predecessors and the military high command to quash the investigation. When Guzmán sought to execute a search warrant at military bases for documents pertaining to the massacre, Bukele ordered the armed forces not to comply; soldiers were stationed at various bases to block the judge’s entry. In a televised address to the nation last year, Bukele accused Guzmán of being a member of the FMLN, which has become a political party since the peace agreement. The claim is baseless.

He also accused the victims’ lawyer, David Morales, of becoming a millionaire from his representation. The 55-year-old Morales began seeking justice for the victims when he was an intern in the legal aid office of the Roman Catholic Church; he now works for a nongovernmental human rights organization, Cristosal. Morales, who has finished presenting witnesses to the court, said that, before Bukele’s dismissal of the judges, he had expected a ruling by Guzmán to be imminent. But unless domestic and international pressure forces Bukele to reverse his order, Morales now fears that the investigation is over.

Cattle. (photo: Patricia Monteiro/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Cattle. (photo: Patricia Monteiro/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Production of meat worldwide emits 28 times as much as growing plants, and most crops are raised to feed animals bound for slaughter

The entire system of food production, such as the use of farming machinery, spraying of fertilizer and transportation of products, causes 17.3bn metric tonnes of greenhouse gases a year, according to the research. This enormous release of gases that fuel the climate crisis is more than double the entire emissions of the US and represents 35% of all global emissions, researchers said.

“The emissions are at the higher end of what we expected, it was a little bit of a surprise,” said Atul Jain, a climate scientist at the University of Illinois and co-author of the paper, published in Nature Food. “This study shows the entire cycle of the food production system, and policymakers may want to use the results to think about how to control greenhouse gas emissions.”

The raising and culling of animals for food is far worse for the climate than growing and processing fruits and vegetables for people to eat, the research found, confirming previous findings on the outsized impact that meat production, particularly beef, has on the environment.

The use of cows, pigs and other animals for food, as well as livestock feed, is responsible for 57% of all food production emissions, the research found, with 29% coming from the cultivation of plant-based foods. The rest comes from other uses of land, such as for cotton or rubber. Beef alone accounts for a quarter of emissions produced by raising and growing food.

Grazing animals require a lot of land, which is often cleared through the felling of forests, as well as vast tracts of additional land to grow their feed. The paper calculates that the majority of all the world’s cropland is used to feed livestock, rather than people. Livestock also produce large quantities of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

“All of these things combined means that the emissions are very high,” said Xiaoming Xu, another University of Illinois researcher and the lead author of the paper. “To produce more meat you need to feed the animals more, which then generates more emissions. You need more biomass to feed animals in order to get the same amount of calories. It isn’t very efficient.”

The difference in emissions between meat and plant production is stark – to produce 1kg of wheat, 2.5kg of greenhouse gases are emitted. A single kilo of beef, meanwhile, creates 70kg of emissions. The researchers said that societies should be aware of this significant discrepancy when addressing the climate crisis.

“I’m a strict vegetarian and part of the motivation for this study was to find out my own carbon footprint, but it’s not our intention to force people to change their diets,” said Jain. “A lot of this comes down to personal choice. You can’t just impose your views on others. But if people are concerned about climate change, they should seriously consider changing their dietary habits.”

The researchers built a database that provided a consistent emissions profile of 171 crops and 16 animal products, drawing data from more than 200 countries. They found that South America is the region with the largest share of animal-based food emissions, followed by south and south-east Asia and then China. Food-related emissions have grown rapidly in China and India as increasing wealth and cultural changes have led more younger people in these countries to adopt meat-based diets.

The paper’s calculations of the climate impact of meat is higher than previous estimates – the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization has said about 14% of all emissions come from meat and diary production. The climate crisis is also itself a cause of hunger, with a recent study finding that a third of global food production will be at risk by the end of the century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at their current rate.

Scientists have consistently stressed that if dangerous global heating is to be avoided, a major rethink of eating habits and farming practices is required. Meat production has now expanded to the point that there are now approximately three chickens for every human on the planet.

Lewis Ziska, a plant physiologist at Columbia University who was not involved in the research said the paper is a “damn good study” that should be given “due attention” at the upcoming UN climate talks in Scotland.

“A fundamental unknown in global agriculture is its impact on greenhouse gas emissions,” Ziska said. “While previous estimates have been made, this effort represents a gold standard that will serve as an essential reference in the years to come.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611