Police reports complicate Herschel Walker's recovery story

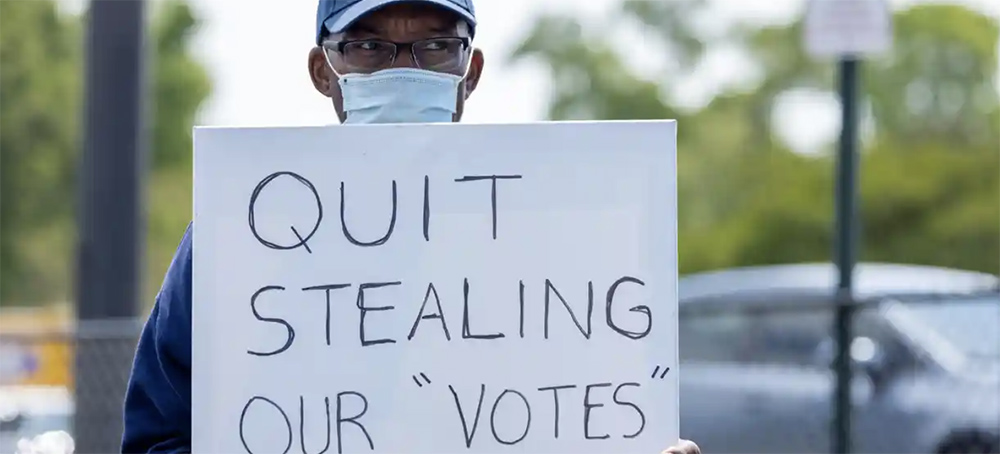

WASHINGTON (AP) — One warm fall evening in 2001, police in Irving, Texas, received an alarming call from Herschel Walker’s therapist. The football legend and current Republican Senate candidate in Georgia was armed with a gun and scaring his estranged wife at the suburban Dallas home they no longer shared.

Officers took cover outside, noting later that Walker had “talked about having a shoot-out with police.” Then they ordered the onetime Dallas Cowboy to step outside, according to a police report obtained by The Associated Press through a public records request.

Much of what happened that day remains shrouded from view because the report, which Irving police released to the AP only after ordered to do so by the Texas attorney general’s office, was extensively redacted.

What is apparent, though, is that Walker’s therapist, Jerry Mungadze, a licensed counselor with a history of embracing practices that experts in the field say are well outside the mainstream, played a pivotal role in extracting Walker from the situation.

The incident adds another layer to Walker’s already turbulent personal history, which includes struggles with mental health and accusations that he repeatedly threatened his ex-wife. And it will test voters’ acceptance of Walker’s assertion that he is a changed person.

Mungadze rushed to the scene to calm Walker down, the report states. In the end, police confiscated a handgun from Walker’s car, but declined to seek charges or make an arrest. Walker’s wife filed for divorce three months later.

Walker’s violent history has done little to deter Republican support for his candidacy. He has been championed by former President Donald Trump and endorsed by the Senate's top Republicans. Last week, Nikki Haley, the former South Carolina governor, tweeted that Walker was “living proof that hard work and determination pay off.”

Walker’s campaign dismissed the newly surfaced information.

“The very same media who praised Herschel for his transparency nearly two decades ago are now running ... stories stereotyping, attacking, and going so far as to question his diagnosis,” Mallory Blount, a Walker spokesperson, said in a statement.

Mungadze rushed to the scene to calm Walker down, the report states. In the end, police confiscated a handgun from Walker’s car, but declined to seek charges or make an arrest. Walker’s wife filed for divorce three months later.

Walker’s violent history has done little to deter Republican support for his candidacy. He has been championed by former President Donald Trump and endorsed by the Senate's top Republicans. Last week, Nikki Haley, the former South Carolina governor, tweeted that Walker was “living proof that hard work and determination pay off.”

Walker’s campaign dismissed the newly surfaced information.

“The very same media who praised Herschel for his transparency nearly two decades ago are now running ... stories stereotyping, attacking, and going so far as to question his diagnosis,” Mallory Blount, a Walker spokesperson, said in a statement.

Mungadze declined to comment.

Mungadze, a licensed therapist who holds a doctorate in philosophy, diagnosed Walker with dissociative identity disorder, following a separate 2001 episode in which Walker says he sped around suburban Dallas fantasizing about executing a man who was late delivering a car he had purchased. The two became close friends.

A former pastor, Mungadze's professional and academic writings lean heavily into the occult, exorcism and possession by demons, which he has called a “theological and sociological reality."

In one method of analysis he has pioneered, which experts have singled out as unscientific, patients are asked to color in a drawing of the brain, with Mungadze drawing conclusions about their mental state from the colors they choose.

He was also featured in a 2014 British TV documentary as a practitioner of gay conversion therapy, a scientifically discredited practice that attempts to change the sexual orientation or gender identity of LGBTQ people.

“It’s really disturbing that a prominent individual like Walker would be seeing someone who just looks like the most dubious caregiver,” said Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Walker has at times been open about his struggle with mental illness, writing at length about it in his 2008 book, “Breaking Free.” Mungadze wrote the book’s foreword.

Walker describes himself dealing with as many as a dozen personalities — or “alters” — that he had constructed as a defense against bullying he suffered as a stuttering, overweight child.

Comparing his condition to a “broken leg,” Walker wrote that Mungadze assured him “it was possible to achieve emotional stability based on the approach and methods he had developed.”

A review of court records and police reports documents a far more turbulent path than portrayed in Walker’s book, which was framed as a turnaround story.

About a year into his treatment, a former Dallas Cowboys cheerleader told Irving police in May 2002 that she believed Walker had been lurking outside her house. The woman said she had a “confrontation” with him roughly a year earlier, which led to Walker making threatening phone calls, according to a police report. The threats subsided, but after Walker spotted her at a local business, she told police he followed her home. The woman asked police not to contact him because it would “only make the problem worse.” She declined to comment for this story.

Walker’s wife has said that she was a repeated target of abuse.

Now going by the name Cindy Grossman, in their divorce proceedings she alleged violent outbursts, "physically abusive and threatening behavior.” When his book was released, she told ABC News that at one point during their marriage, her husband pointed a pistol at her head and said, “I’m going to blow your f’ing brains out.”

She returned to court in 2005 for a protective order after Walker repeatedly voiced a desire to kill her and her boyfriend, according to court records.

Walker “stated unequivocally that he was going to shoot my sister Cindy and her boyfriend in the head,” her sister later said in an affidavit, which the AP first reported in July. Not long after the threat, Walker confronted Grossman in public, according to court filings, which indicate he “slowly drove by in his vehicle, pointed his finger at (Grossman) and traced (her) with his finger as he drove.”

A judge granted the protective order and stripped Walker of his right to carry firearms for a period of time. Grossman did not respond to a request for comment at a number listed for her.

The pattern of behavior is alleged to have continued until at least 2012.

That’s when a woman named Myka Dean told Irving police that Walker “lost it” when she tried to end an “on-off-on-off” relationship with him, which she said had lasted for 20 years. Walker, she told officers, threatened to wait outside her apartment and “blow her head off,” according to a January 2012 police report.

Dean, who died in 2019, told police she didn’t want to get Walker in trouble. But the officer decided to document the incident because of the “extreme threats” Walker made.

Walker’s campaign denied that he made the threats.

“Herschel emphatically denies these false claims. He is still friendly with Ms. Dean’s parents, who knew nothing of the allegations and are supportive of his campaign,” Blount said.