17 January 22

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News FREE OF CORPORATE INFLUENCE, BUT NOT FREE Yes we have succeeded in building a great information source — free of shady financing. We do however have to pay the bills, (the honest way). Join the many who support this wonderful project. Get behind RSN.

Marc Ash • Founder, Reader Supported News Sure, I'll make a donation!

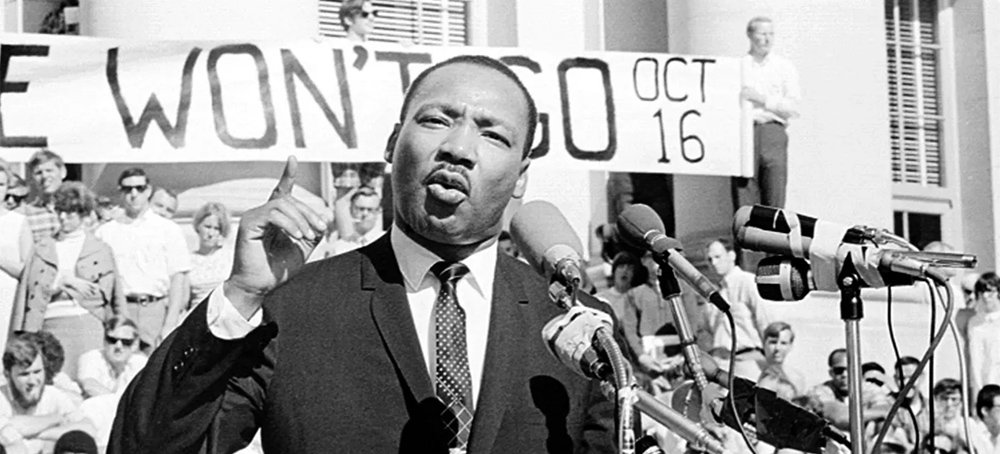

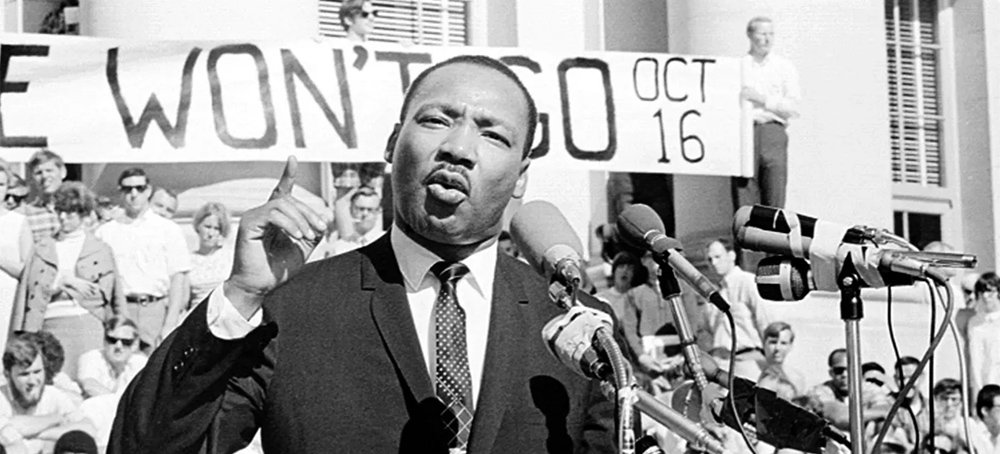

Juan Cole | Why MLK Would Have Launched Nonviolent Disobedience to Pass the Freedom to Vote Act

Juan Cole, Informed Comment

Cole writes: "Everything that the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., struggled for is at risk in today's America, where one of the two major parties has succumbed to the deadly disease of Trumpism, which is built on white grievance."

Everything that the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., struggled for is at risk in today’s America, where one of the two major parties has succumbed to the deadly disease of Trumpism, which is built on white grievance. As the Republican Party has become more and more inflected by white nationalism, its officials have begun attempting to undo the gains of the Civil Rights Movement led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., which ended the Deep South’s practices of segregation and denying the vote to African-Americans. The Republican-captured Supreme Court, now also an instrument of white nationalism and corporate supremacy, struck down in the 2013 ruling Shelby County v. Holder the oversight provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The Southern states initiated a gold rush to restrict the right to vote with new tactics, rather than the old literacy tests, using voter ID requirements and reducing the number of polling stations in heavily minority counties. The Brennan Center for Justice writes of 2021, “Between January 1 and December 7, at least 19 states passed 34 restrictive laws. The restrictive laws make it more difficult for voters to cast mail ballots that count, make in-person voting more difficult by reducing polling place hours and locations, increase voter purges or the risk of faulty voter purges, and criminalize the ordinary, lawful behavior of election officials and other individuals involved in elections.” There are two bills in Congress that would roll back the sinister and reactionary laws passed by Republican statehouses. The John Lewis Voting Rights Act would restore Department of Justice preclearance oversight of election laws in states with a tradition of suppressing the Black vote. The Freedom to Vote Act requires early voting days, no-excuse mail voting, and other provisions that protect this essential right from the provincial blowhards now tinkering with it. Because all fifty Republican senators oppose both of these bills, they can’t get past the Senate’s 60-vote threshold to close off filibustering and allow a floor vote. Because two Democrats, Sens. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) oppose a carve-out of the filibuster for voting rights, the President cannot get the legislation he backs passed. CNN explains that in the late 1700s, the Senate could vote to end debate on a bill and bring it to a floor vote by a simple majority. Even in the twentieth century, a filibuster to prevent a vote required the senator to stay on the floor speaking with no food or bathroom breaks. The current 60-vote rule for cloture or ending debate only dates from 1975, and from that time it was permitted to filibuster by simply registering an objection to cloture, rather than physically speaking at the podium. One possible way forward for the Democrats is to go back to requiring senators to filibuster in person. As we honor Dr. King today, it is worth remembering what he said about the filibuster: “I think the tragedy is that we have a Congress with a Senate that has a minority of misguided senators who will use the filibuster to keep the majority of people from even voting. They won’t let the majority senators vote. And certainly they wouldn’t want the majority of people to vote, because they know they do not represent the majority of the American people. In fact, they represent, in their own states, a very small minority.” As for voting rights, they were at the heart of King’s campaigns of civil disobedience. He said in Montgomery, Alabama in 1956, “We must continue to gain the ballot. This is one of the basic keys to the solution of our problem. Until we gain political power through possession of the ballot we will be convenient tools of unscrupulous politicians. We must face the appalling fact that we have been betrayed by both the Democratic and Republican parties . . . Until we gain the ballot and place proper public officials in office this condition will continue to exist. In communities where we confront difficulties in gaining the ballot, we must use all legal and moral means to remove these difficulties. We must continue to struggle through legalism and legislation. There are those who contend that integration can come only through education, for no other reason than that morals cannot be legislated. I choose, however, to be dialectical at this point. It isn’t either education or legislation; it is both legislation and education.” If voting rights keep being endangered, nonviolent noncooperation on a mass scale may well reemerge. King said of the boycotts, marches and other campaigns of the Indian freedom struggle in British colonial India, “I had heard of Gandhi, but I had never studied him seriously. As I read I became deeply fascinated by his campaigns of nonviolent resistance. I was particularly moved by the Salt March to the Sea and his numerous fasts. The whole concept of “Satyagraha” (Satya is truth which equals love, and agraha is force: “Satyagraha,” therefore, means truth-force or love force) was profoundly significant to me. As I delved deeper into the philosophy of Gandhi my skepticism concerning the power of love gradually diminished, and I came to see for the first time its potency in the area of social reform.” The ballot and education are necessary for achieving social and racial justice. But where these are blocked, the truthforce may be brought into play. And in this moment, all of us are in danger of being robbed of the franchise, of the validity of our votes, by corrupt and tyrannical Trumpists. It isn’t just the African-Americans who face a new Jim Crow.

READ MORE

Martin Luther King III, the eldest son of the late civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., his wife Arndrea Waters King and daughter Yolanda Renee King take part in the annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Peace Walk on the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge on Monday. (photo: Astrid Riecken/WP) Martin Luther King III, the eldest son of the late civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., his wife Arndrea Waters King and daughter Yolanda Renee King take part in the annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Peace Walk on the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge on Monday. (photo: Astrid Riecken/WP)

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Family Marches in DC for Senate Action on Voting Rights Bill

Katherine Shaver, The Washington Post

Shaver writes: "Members of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s family demanded Monday that the Senate scrap the filibuster and pass voting rights legislation as they led a D.C. march on the holiday honoring the civil rights icon." March organizers are calling on the Senate to end the filibuster to allow for a vote on voting rights legislation. Members of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s family demanded Monday that the Senate scrap the filibuster and pass voting rights legislation as they led a D.C. march on the holiday honoring the civil rights icon. King’s son, Martin Luther King III, his wife Arndrea Waters King and their 13-year-old daughter, Yolanda Renee King, joined several hundred other activists and residents in a frigid walk across the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge. The bridge, they said, symbolized President Biden’s and Congress’s support for the recently approved $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill. “To the president and United States senators, you were successful with infrastructure, which is a great thing,” King III told the crowd gathered outside Nationals Park before they headed over the bridge. “But you need to use the same energy to ensure all Americans have an unencumbered right to vote.” As a wintry breeze blew, D.C. resident Lydia Davis said she and a friend marched to honor King and advocate for access to the ballot box, as well as other rights he fought for. “I’m 64, and all the issues we’re marching for are the same things,” said Davis, a D.C. schools substitute teacher. “I’m marching so my daughter doesn’t have to march 10 years from now.” The group continued as part of the annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Peace Walk on its two-mile route along Martin Luther King Avenue SE. They then were scheduled to attend a news conference at Union Station with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and other House members to call on the Senate to avoid a filibuster and pass the voting rights bill Tuesday. “From the Civil War to the Jim Crow era, the filibuster has blocked popular bills to stop lynching, end poll taxes, and fight workplace discrimination,” organizers said on their website. “Now it’s being used to block voting rights. The weaponization of the filibuster is racism cloaked in procedure and it must go.” The King family also participated with hundreds of others in a march Saturday in Phoenix, according to media reports. Participants on Monday hoisted signs saying “Black votes matter,” “Jews for the freedom to vote,” and “Voter suppression is un-American.” The Rev. Ray East, 71, said the wintry temperatures and slushy mess left from the previous evening’s snow and freezing rain didn’t discourage him from joining the peace walk, as he has for about the past 10 years. With voting rights legislation pending in Congress, he said, participating this year felt even more pressing. “I can’t think of another time in my life when we were at a juncture like this — where we have the opportunity for us to do the right thing and act on the side of justice and democracy,” East, a District resident, said as he brought up the rear of the crowd. “When Dr. King was marching, I was a teenager. Now it’s about voting and how important it is for people to be enfranchised.” Speaking of which, East said, “It’s a good time to talk about D.C. statehood.” Many participants, including King III, said they couldn’t advocate for voting rights without including a call to give the District voting representation in Congress. The “Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act,” passed by the House last week, is scheduled for Senate consideration Tuesday. However, its passage is in doubt because Democrats lack the votes to change the rules to avoid a filibuster from Republican opponents. Supporters’ efforts suffered a blow last week when Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin III (W. Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (Ariz.) said they would oppose attempts to change the filibuster rules. The Democratic senators’ opposition also marked a defeat for President Biden, who had personally appealed for congressional support to end the filibuster following a major voting rights speech in Atlanta. Biden said the Senate should eliminate the filibuster if necessary to at least debate the legislation, calling recent state limits on voting access a “threat to our democracy” and “Jim Crow 2.0.” Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) has said he could start debate on the voting rights bill with a simple majority of 51 votes because of rules that govern the way it passed the House. However, unless the Senate changes the filibuster rules, 60 votes would still be required to end debate and move to a vote. The Senate is split 50-50, and voting rights measures have had united opposition from Republicans. GOP-led legislatures, many spurred by President Donald Trump’s false claims that the 2020 election was stolen, have recently passed voting restrictions, including expanding ID requirements and limiting early voting and voting by mail. Democrats and civil rights leaders say those changes will suppress the vote, particularly among minorities, while Republicans say they need to prevent voter fraud and restore public faith in the electoral process. The pending legislation would establish national standards for voter registration, early voting, voting by mail and permissible voter IDs. It also would make Election Day a federal holiday and restore federal legal authority over certain voting changes in states and jurisdictions with a history of discrimination, according to reports.

READ MORE

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images) Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

The Trump Org Stiffed a Hotel. His Kids May Pay the Price.

Jose Pagliery, The Daily Beast

Pagliery writes: "The D.C. attorney general wants to drag the Trump Organization back into a lawsuit. His evidence? An unpaid $49,000 hotel bill." The D.C. attorney general wants to drag the Trump Organization back into a lawsuit. His evidence? An unpaid $49,000 hotel bill.

Former President Donald Trump and his family company have a long history of stiffing contractors, but there’s one bill they almost certainly wish they had paid. Ahead of the 2017 presidential inauguration, the Trump Organization reserved a block of rooms at the Loews Madison Hotel. When at least 13 people didn’t show up, the Trump Organization refused to pay the bill, something it has done many times in the past. The company then dodged a credit collection agency and eventually squirmed out of it by pushing the $49,358 bill off to the nonprofit presidential inaugural committee, the PIC. That dodged payment is now the crux of the attorney general for the District of Columbia’s latest effort to put the Trump Organization back in its crosshairs in an ongoing investigation into how the Trump kids used the Presidential Inauguration Committee to throw lavish parties of their own. “It was their friends. It should never have been sent to the PIC. That’s misuse of funding. The Trump Organization being involved in any way and getting the PIC to pay any sort of balance anywhere on their behalf? It just doesn’t seem legitimate,” said Stephanie Winston Wolkoff, who coordinated inaugural events and is now the government’s lead witness in this case. Winston Wolkoff is no friend of the Trumps—any more. Although she was close to the family for more than a decade and eventually became “Trusted Adviser” to First Lady Melania Trump, there was a fallout after Winston Wolkoff felt that the Trump White House made her the scapegoat for inauguration misspending. The New York Times identified a company associated with her, WIS Media Partners, as the recipient of a whopping $26 million, and Winston Wolkoff later overcame Justice Department resistance to publication of her tell-all book called Melania and Me. D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine continues to investigate how the inauguration committee allegedly misspent more than $1 million and was allegedly used to essentially enrich Trump’s own company on his way into the White House. And the Attorney General’s office is trying to recover from a courtroom defeat late last year. In November, D.C. Superior Court Judge José M. López seemed to doom the local attorney general’s investigation when he cut the Trump Organization loose from the lawsuit. His reasoning, which surprised those following the case, was that the family’s company wasn’t directly involved—even though Don Jr., Ivanka, and other staffers at the company’s New York office were on a lot of the paperwork. So he dropped the Trump Organization from the lawsuit. The judge’s Nov. 8 order hinged on the company’s claims that Texas financier Gentry Beach didn’t have the authority to list the Trump Organization when he pulled out an American Express credit card and made the large and expensive reservation. However, Beach was no stranger to the Trump Organization. He was Donald Trump Jr.’s college pal and was handpicked to serve on the nonprofit’s finance committee. He was also outed by journalists even before the inauguration for being part of a nonprofit—directed by Eric Trump, Don Jr. and another wealthy Texan—that seemed to be auctioning off access to the Trumps. Since then, Racine’s office has filed documents in court seeking to reverse that, pointing to numerous receipts and memos that show how even the debt collector wouldn’t be duped into letting the Trump Organization weasel its way out of this one. In the typical fashion of an aggressive collections agency, Campbell Hightower … Adams in Arizona started bombarding the company with phone calls and emails in June 2017, picking up where the Loews Madison Hotel had left off. A collector, identified only as “Sherie,” jotted down notes when she repeatedly communicated with Don Jr.’s executive assistant, Kara Hanley. “Unfortunately, this was not an agreement made by anyone at The Trump Organization. Best, Kara,” Hanley wrote on June 8. “A contract was signed and then 13 people did not show up for the rooms you reserved [sic] so according to the contract terms, those rooms still have to be paid for. What am I missing?” Sherie wrote back. A few weeks later, Sherie notified the Trump Organization that she had just found out that yet another Don Jr. executive assistant, Lindsey Santoro, had initially requested the rooms and added Beach as the main contact for the deal. That information seemed to cement even further that the company was indeed involved. And when the hotel contacted the collections agency in July to request that the bill suddenly change the listed debtor to “58th Presidential Inauguration Committee”—with an odd special note saying “It just cannot say ‘The Trump Organization’”—Sherie grew suspicious. “I hesitate as they all seem to be pointing fingers and making excuses as to why they won’t pay it and this seems to be another ploy so the Trump Organization’s name is not on it,” Sherie wrote back on July 10. Records show the bill was eventually paid by the Presidential Inaugural Committee at the direction of Rick Gates, a Trump political operator ally who served on the committee—and eventually served jail time for committing unrelated crimes caught by special counsel Robert Mueller's Russia investigation. The District of Columbia’s AG hopes this evidence proves that the Trump Organization should remain part of the lawsuit, which seeks to seize money it deems was misused and divert it instead to another nonprofit. Otherwise, the civil investigation would continue only against the PIC (which is no longer active) and the Trump International Hotel Washington (which is being sold anyway). In court filings, a lawyer for the Trump Organization and Trump Hotel blasted the AG’s last-ditch effort as merely “rehashed arguments” that seek “several bites at several apples.” On Dec. 14, attorney Rebecca Woods reiterated that Don Jr.’s buddy, Beach, didn’t have the explicit authority to make the deal. She also wrote that investigators shouldn’t be allowed to now seek sworn testimony from him or Santoro, the executive assistant. When approached by The Daily Beast, the AG’s office pointed to the arguments it made in court. The Trump Organization’s lawyer didn’t respond to a request for comment. The collection agency didn’t return calls on Friday. Notably, none of these documents described yet another layer of Trump Organization involvement: how company chief financial officer Allen Weisselberg puzzlingly assumed the responsibility of auditing the nonprofit PIC’s finances. Last summer, D.C. investigators wanted to interview him under oath, but he was then indicted for criminal tax fraud in New York City. The local attorney general’s request is now up to the judge—but a different one this time. On New Year’s Eve, the case was reassigned to D.C. Superior Court Judge Yvonne Williams, a former NAACP lawyer appointed to the bench by President Barack Obama. READ MORE

The Stone of Hope, a granite statue of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., stands at his memorial in Washington, DC, on January 14, 2022. (photo: Mandel Ngan/Getty Images) The Stone of Hope, a granite statue of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., stands at his memorial in Washington, DC, on January 14, 2022. (photo: Mandel Ngan/Getty Images)

Could a 54-Year-Old Civil Rights Law Be Revived?

Jerusalem Demsas, Vox

Demsas writes: "Decades after Martin Luther King Jr.'s fight, American cities still segregate communities by race and class." Decades after Martin Luther King Jr.’s fight, American cities still segregate communities by race and class. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on April 4, 1968, helped usher in the passage of the Fair Housing Act (FHA), a law that promised to not only stop unjust discrimination but also reverse decades of government-created segregation. The FHA, which made discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, and disability illegal in the process of buying and selling homes, had already failed to pass Congress in two earlier versions. As Michelle Adams wrote for the New Yorker, the 1968 version would likely have met the same end if not for the political impact of the assassination. But just a few months after the act’s passage, Richard Nixon was elected, and, as Nikole Hannah-Jones explained, the federal government’s “betrayal” of the FHA’s promise began. Nixon’s Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary George Romney did attempt to use the FHA to meet its goal and actually desegregate white communities, telling “HUD officials to reject applications for water, sewer, and highway projects from cities and states where local policies fostered segregated housing.” But Nixon put a quick stop to this policy. And as Hannah-Jones documents, he wasn’t the last; since then, “a succession of presidents — Democrat and Republican alike — followed Nixon’s lead.” In the 21st century, segregated communities are kept that way not through laws that explicitly attempt to keep certain areas white but through a more insidious method — exclusionary zoning and land-use regulations that make it illegal to build affordable types of housing, laws that allow wealthy Americans to block things from being built, and a failure to consistently use federal civil rights laws to desegregate. All of this has resulted in the prices of housing and rent skyrocketing. Over the last year, diminished supply as a result of these laws has pushed the cost of shelter higher than ever, straining the pockets of working-class, middle-class, and even some high-income Americans. To attack these regulations with the FHA, plaintiffs would have to prove that these laws have a “disparate impact” on a protected group — for instance, proving that a community blocking 300 units of moderately priced housing was discriminating on race, national origin, or family status. But Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation and a leading thinker on economic integration, has an idea: Amend the Fair Housing Act to include economic discrimination as a legally prohibited form of discrimination. No longer would litigators have to jump through hoops to prove that banning new affordable housing construction hurts people of color disproportionately. Instead, plaintiffs would just have to show that towns that blocked these developments were discriminating against poor people — regardless of their race, national origin, or family status. “It’s immoral for governments to erect barriers that exclude and discriminate based on income and, as a matter of basic human dignity, economic discrimination belongs in the Fair Housing Act,” Kahlenberg explained. While Democrats have often talked eloquently about the importance of fair housing, they have never seriously attempted to take on exclusionary zoning at the federal level. Left in limbo is George Romney’s idea that the federal government should withhold funds from localities still actively engaged in exclusionary zoning practices and thereby undermining the economic wellbeing of the entire country. Even now, as billions of infrastructure dollars are heading to states and local governments, it’s barely up for discussion. (Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that economically segregationist communities are often ones led by Democrats — in wealthy cities and suburbs, economic discrimination is a normal facet of life.) Enacting an Economic Fair Housing Act wouldn’t be as sweeping as Romney’s idea from the 1970s, and any new protections would still need to be enforced. Kahlenberg has been advising Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D-MO) as the latter has begun drafting a bill to amend the FHA to include economic discrimination in the housing market. “I think one of the greatest tributes that we can make to Dr. King’s legacy is for us, this year, to pass an Economic Fair Housing Act,” Cleaver told me over the phone. I spoke with Kahlenberg about the potential for an Economic Fair Housing Act and whether this would really push the ball on increasing affordable housing. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity. Jerusalem Demsas You’ve written a lot about exclusionary zoning built explicitly on the attempt to segregate based on race. Has that all morphed into economic discrimination? Richard Kahlenberg In certain communities, there is still an intent to segregate by race, so I don’t want to downplay that, but having said that, there’s certainly evidence that the issue of exclusionary zoning is not only about race. We know in predominantly white communities that wealthy whites will use zoning to exclude lower-income whites. We also know, for example, in Prince George’s County, Maryland, a predominantly Black community, that there are efforts by wealthier Black people to exclude lower-income Black people through exclusionary zoning. In some white, liberal communities, you will hear people say they are delighted to have a Black doctor or lawyer move in next door. And so they feel virtuous for no longer excluding directly based on race, without acknowledging that they’d be highly uncomfortable with working-class Black people or white people moving into the neighborhood. So I think it’s important that we recognize that there’s exclusion going on by both race and class, which is why we need some new tools to beef up the existing laws. Jerusalem Demsas I think one of the most interesting parts of when you look at Supreme Court history in this space is the entrenching of the idea that apartments and multi-family housing are inherently a nuisance. In Euclid v. Ambler (1926) the Court wrote: “depriving children of the privilege of quiet and open spaces for play, enjoyed by those in more favored localities — until, finally, the residential character of the neighborhood and its desirability as a place of detached residences are utterly destroyed. Under these circumstances, apartment houses … come very near to being nuisances.” And in the American context, thinking of multi-family housing as inherently a nuisance is pretty normalized. Can you talk a little bit about how this idea has played an important role in perpetuating economic segregation? Richard Kahlenberg The Euclid decision that you mentioned is fascinating because while the Supreme Court ultimately upheld economically discriminatory zoning, citing this idea that apartments are a nuisance, the lower court recognized that this is clear class discrimination. And that is what’s going on — the notion that an apartment is a nuisance is a class-laden concept connected to the idea that there is a negative effect on wealthier people when lower-income people are in proximity. Jerusalem Demsas So what is your solution here? You’re proposing an Economic Fair Housing Act, what is that? Richard Kahlenberg So the idea of the Economic Fair Housing Act would extend the 1968 Fair Housing Act protection against racial discrimination to include protection against income discrimination by the government. When local governments adopt “snob zoning” laws, they’re effectively saying we don’t want lower-income people in our community, and that’s a form of economic discrimination. The Economic Fair Housing Act would allow plaintiffs who are harmed by government-sponsored income discrimination to sue in federal court the way one currently can under the Fair Housing Act for racial discrimination. The new law would draw upon the concept of “disparate impact,” which is used in the Fair Housing Act. So a plaintiff wouldn’t have to show that the government’s intent is to discriminate based on income, but only that exclusionary zoning has the effect of discriminating based on income. As with racial disparate impact suits, the burden would shift to the local government to prove that its policy is necessary to achieve a valid interest. Jerusalem Demsas There are a lot of judges who might say that there is a valid interest in upholding exclusionary zoning, building on the established idea that apartments — and by extension working-class and middle-class people — are nuisances. Richard Kahlenberg I think many judges will see through the pretexts offered by local governments. If, say, governments indicate they want to minimize traffic and parking congestion, a reasonable court is likely to press them: Is it really “necessary” to ban all duplexes and triplexes? But to guard against conservative judges watering down the standard, it would be possible to include some process-oriented and results-oriented guardrails in the legislation. In this report, I suggested a ban on duplexes and triplexes could make a zoning policy presumptively illegitimate as a matter of process, and zoning policies in a community that had a very small share of affordable housing might be presumptively illegitimate as a matter of outcomes. Jerusalem Demsas My understanding with the Fair Housing Act is that the difficulty of enforcement happens in a couple of places. One is that the “disparate impact” standard is actually quite difficult to reach, and there are many judges that are hostile to that analysis. And secondly that it requires just a ton of resources to suss out the disparate impact. You often have to determine the counterfactual of what would have happened if a different legal system existed or what type of people would have lived in a development if it had not been blocked. It sometimes requires a mix of statisticians, economists, and sociologists in addition to lawyers to do that analysis. So, how does adding economic discrimination help solve that core issue? Richard Kahlenberg I think it would make a big dent. The criticisms you cite of the Fair Housing Act are legitimate. Having said that, when the law was passed in 1968, I think it had two big impacts. One is the impact on culture. If you go back to polling in the 1960s, a majority of white people said that whites should have the right to keep Black people out of neighborhoods. Today, virtually no one would say that, and so having a law on the books can change culture and delegitimize discrimination. I think it did a good job of delegitimizing racial discrimination, and the aim is that the Economic Fair Housing Act would play a similar role. In terms of the consequences, if we look at levels of racial segregation in this country, they remain far too high, but they have declined about 30 percent since 1970. Black-white segregation is often measured with a dissimilarity index, and it stood at 79 in 1970, and it’s at 55 in 2020. Meanwhile, income segregation has been headed in the opposite direction. It’s basically doubled since 1970. And so, while the Fair Housing Act is imperfect, it has had a positive impact on issues of racial discrimination in housing. And I think an Economic Fair Housing Act could have similar effects. In terms of the statistical analysis required, one of the arguments for an Economic Fair Housing Act is that it would be easier to show that exclusionary zoning policies have a disparate economic impact. Jerusalem Demsas Oh, interesting. Why is that? Richard Kahlenberg Well, right now it’s a bit of a bank shot. These laws are effectively aimed at excluding based on income and then you have to show how race and income interact. So it just removes one step in the process. Jerusalem Demsas When the federal government has attempted to impose desegregation on communities, particularly with school desegregation, we see a ton of backlash, much of which is successful at maintaining segregation. Are you worried that legislation like this will just result in states and localities getting more wily at getting around this new law and not solve the underlying problems in the long run? Richard Kahlenberg So I would say a couple of things. One, if you look at the history of school desegregation, there was enormous backlash to federal efforts to desegregate. But, at the end of the day, school desegregation in the South worked. That is to say, although there was political resistance, over time the South went from being the most segregated part of the country in terms of their schools, to the most integrated part of the country, and we saw the achievement gap between Black and white students fall considerably during the era of desegregation. So, although it took a long time — there was enormous inaction between Brown in 1954 and when federal government efforts to desegregate actually took off in the late 1960s — it was enormously effective for an important group of students who benefited from the policy. More to the point, the Fair Housing Act was very controversial at the time. There were US senators who lost their jobs over supporting [fair housing]. But today, the concept is broadly accepted, and you wouldn’t gain political traction from saying you want to repeal the federal Fair Housing Act. Jerusalem Demsas Contrasting this with other attempts by the federal government to address this problem — for instance, the grants the White House has proposed to provide planning and technical grants for localities that want to willingly re-zone — it seems like the winds are turning toward offering carrots (and very small carrots at that) rather than engaging in anything that could appear punitive. Do you think the political winds are shifting away from being able to enact policies like the Economic Fair Housing Act? Richard Kahlenberg Well, let me answer that in a couple of ways. I’m very supportive of efforts to either essentially bribe localities into doing the right thing through a Race to the Top program if you don’t reduce exclusionary zoning. I think that’s a good effort, but I think that the Economic Fair Housing Act offers something both substantively and politically that’s better. I think part of the problem with the existing federal proposals is that they suggest that exclusionary zoning is bad policy because it blocks opportunity and makes housing less affordable and damages the planet. All of those things are true, but what I think the Economic Fair Housing Act tries to do is say it’s not just bad policy, it’s immoral for governments to erect barriers that exclude and discriminate based on income ... because it’s shameful what’s going on. I also think the Economic Fair Housing Act framing will do a better job of raising awareness of the issue. I’m working on a book now called The Walls We Don’t See because people’s eyes glaze over when you talk about zoning. People understand that when white people were throwing rocks at buses carrying Black children to school in order to desegregate, that’s wrong. It’s dramatic. The Economic Fair Housing Act does a better job than those other efforts to make people see what’s going on. It’s also more comprehensive than Build Back Better’s Unlocking Possibilities Program, which would reach a small number of places that are incentivized to make reforms. But this is comprehensive, it’s everywhere. So, I think this would be more effective than all those other approaches. But going back to the point I was making earlier, I think the economic framing is absolutely essential. I’ve been reading Heather McGhee’s book, The Sum of Us, which I think is just brilliant. One of her points is that if you want to make progress in society, you have to show white people how racism hurts them, and this is a classic example of where zoning began as racial in character and shifted to economic in order to exclude by race and ended up pulling in a lot of working-class whites as well. Jerusalem Demsas Can you speak more to the political coalition-building benefits of the economic framing approach? Richard Kahlenberg If you look at what drove Donald Trump, a lot of it was what Michael Sandel called the politics of humiliation. And it is humiliating for working-class white people with less education to feel as though cultural elites are looking down on them — as they do. I would never say it’s as bad as racism, but there is a way that economic framing helps unite these two groups that have been at war with each other for decades — working-class white people and people of color. In a common sense, they are being looked down upon for different reasons by well-to-do white people. So I think the politics are powerful here. We’ve seen that in Oregon and California where there are these fascinating political coalitions of conservative rural white legislators and urban liberal legislators of color who, not always, but in large measure have come together to defeat wealthier white suburban legislative interests in making the case for reform. Jerusalem Demsas The Economic Fair Housing Act which you have been fighting for for years is now getting legislative attention. Richard Kahlenberg I’m excited that there’s interest on Capitol Hill and that Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, who is chair of the subcommittee on housing in the House, is working on draft legislation to create an Economic Fair Housing Act. He held hearings back in October on exclusionary zoning, and there’s a comment that he made at the beginning of the hearing which I found to be very profound. He said he was in Kansas City, he worked on zoning matters as a local official, and he said you just learn a lot about human nature and what people are really like when issues of zoning come up. I think someone like him, who understands the importance of zoning and the way it affects disadvantaged people, working-class people, middle-class people who are excluded from higher-opportunity neighborhoods — I’m excited that someone like him is interested in moving forward with this type of legislation.

READ MORE

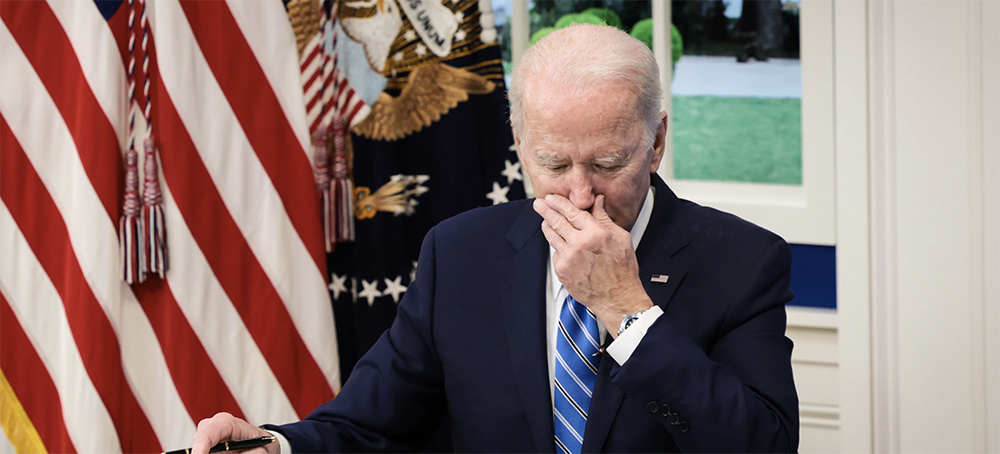

President Joe Biden listens during a video call at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C., on Dec. 27, 2021. (photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images) President Joe Biden listens during a video call at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C., on Dec. 27, 2021. (photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

Congressional Democrats Join Republicans to Undermine Biden Administration's Surprise Medical Billing Rule

Austin Ahlman, The Intercept

Ahlman writes: "Congressional Democrats are joining Republicans in a last-ditch effort to undermine the newly implemented No Surprises Act, which bans surprise medical bills." Worried an aggressive new rule could cut into providers’ earnings, key members of Congress including Massachusetts Representative Richard Neal are helping private industry weaken the administration’s position in federal court. Congressional Democrats are joining Republicans in a last-ditch effort to undermine the newly implemented No Surprises Act, which bans surprise medical bills. A key provision in the law could become a first step toward allowing the federal government to standardize rates for medical procedures covered under private insurance plans, an objective the private health care industry has fought for decades. Late last year, in the months leading up to the bill’s enactment, opponents filed a flurry of lawsuits claiming that by enforcing the rule in a manner widely viewed as consistent with the text of the legislation, the Biden administration had overstepped Congress’s intentions. The leading opponents of the provision, which mandates that insurers and health care providers settle billing disputes based primarily on the median in-network rate for a procedure, are organizations representing the private health care industry, like the American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association. Along with a number of health care providers, the groups have filed lawsuits that federal courts are expected to decide in the coming months, before the first round of disputes under the new law reaches the arbitration stage. The legal arguments rely on murky case law about congressional intent, but nonpartisan experts familiar with the No Surprises Act told The Intercept that the rule is consistent with the law’s text. Instead, they point to the law’s possible consequences to explain why providers are fighting so hard to undermine its implementation. The move has the potential to drive down the high prices U.S. providers charge compared to other countries, stoking fears in the health care industry that it would lead to standardized rates. The drop in prices would at least partially be returned to Americans in the form of lower health insurance premiums. A series of letters and statements by members of Congress from both parties, including Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La.; Sen. Maggie Hassan, D-N.H.; and Rep. Richard Neal, D-Mass., has nonetheless sought to support filers’ claims. Their apparent aim is to bolster providers’ legal arguments that the Biden administration went beyond Congress’s intent in crafting the rule that governs the resolution of unpaid medical bills. But the law’s author, Rep. Frank Pallone, D-N.J., has decried attempts to undermine its implementation. On Twitter last month, he called one of the lawsuits “an outrageous attempt to block the most significant patient protection enacted since the Affordable Care Act.” Prior to implementation of the No Surprises Act, providers regularly billed patients covered by out-of-network insurers directly for the difference between their rate for a treatment and the insurer’s allowed amount. These bills were often substantially higher than the true cost of the procedure or the price a provider would charge an in-network patient. That practice, known as “balance billing,” will remain banned regardless of the outcome of litigation. Instead, providers and insurers will enter forced baseball-style arbitration if they cannot agree on the price for treatment. Each side will send the arbiter a payment offer, and the arbiter will pick the offer they think is most fair. At issue in the lawsuits is the administration’s interpretation of this process. Under the Biden administration’s proposed rules, arbiters must prioritize the median in-network rate when deciding disputes, forcing providers to justify any departure from their typical rates. The rule effectively stops them from price-gouging consumers who are out-of-network. Providers claim the text of the No Surprises Act requires the administration to weigh a number of other potentially extenuating factors, such as the physician’s level of experience, equally to the median in-network rate. But nonpartisan experts like Jack Hoadley, a professor emeritus at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy who has followed the act’s implementation closely, told The Intercept that the administration’s rule matched up with his expectations and his own read of the statute. Analysts for the Brookings Institution wrote last year, before the law’s implementation, that while median rates are “only one of several factors that arbitrators are supposed to consider, so there remains some risk that arbitrators will ultimately place substantial weight on other factors,” it is “reassuring that median in-network rates are the first, and most concrete, point of guidance to arbitrators.” In other countries, price controls for medical treatments are common. And in the United States, Medicaid and Medicare have been able to negotiate prices for some time. But U.S. legislators have historically been averse to regulations aimed at standardizing the rates private insurers pay. As a result, the majority of the excessive cost Americans pay for health care can be attributed to the steep, unregulated prices charged by providers. Any move toward standardizing these rates poses a threat to providers that rely on inflating patients’ bills and forcing them to cover massive surcharges far above the actual cost of the procedure. The providers’ investors in particular stand to lose if the new rule is enacted. According to Karen Pollitz of the Kaiser Family Foundation, there is substantial evidence that “venture capital investors were strategically investing in practices that are prone to surprise, out-of-network billing,” because “they knew they could charge whatever they want.” Democrats have led investigations in the House of Representatives focused on the role that private equity and venture capital firms have played in incentivizing practices like balance billing. Pollitz told The Intercept this particular practice will be curtailed, even if the lawsuits disputing the new rule succeed. Should the administration prevail in court, though, providers will be pushed much harder to fix the root problem of surprise medical bills: unregulated and wildly varying treatment prices. Despite plaintiffs’ questionable legal reasoning, members of Congress from both parties have joined the fray on behalf of providers in hopes of bolstering the argument that the Biden administration snubbed congressional intent with its aggressive new rules. In a May letter addressed to Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, and Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, Sens. Hassan and Cassidy — two legislators who played major roles in crafting the No Surprises Act — warned the administration against implementing the act’s dispute resolution process in a way that favored the median in-network rate. The letter makes an explicit argument for the provider’s preferred interpretation of the text, claiming that legislators “wrote this law with the intent that arbiters give each arbitration factor equal weight and consideration.” Cassidy released a similar follow-up letter in late December, but Hassan, whose office did not respond to a request from The Intercept to clarify her position on the administration’s interpretation of the rule, did not sign. After the Biden administration issued the arbitration rule at the end of September, House Ways and Means Committee Chair Neal and ranking member Kevin Brady, R-Texas, sent the administration another letter mirroring the language used by Hassan and Cassidy. Their letter argues that “Congress deliberately crafted the law to avoid any one factor” — like the median in-network rate — “tipping the scales” during arbitration. As leaders of the Ways and Means Committee, which played a substantial role in crafting the bill, they carry increased authority in litigation over congressional intent. Neal, who has taken hundreds of thousands of dollars from the American Hospital Association over his more than three decades in Congress, played a uniquely critical role in the act’s passage as part of coronavirus relief legislation in December 2020. At the time, he threatened to sink the bill if it did not contain a provision forcing insurers and providers to go straight to arbitration in disputed cases. The chair, whose office did not respond to a request for comment, is now siding with providers who say the process he demanded does not adequately favor them. In November 2021, a large, bipartisan group of House members also sided with providers in the dispute. Reps. Tom Suozzi, D-N.Y.; Brad Wenstrup, R-Ohio; Raul Ruiz, D-Calif.; and Larry Bucshon, R-Ind., led 150 of their colleagues in a letter that claimed to lay out, in starkly legalistic terms, the congressional intent behind the No Surprises Act. While the letter’s signatories — 79 Republicans and 73 Democrats — were disproportionately conservative, a few committed progressives, like Barbara Lee, D-Calif., and Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich., also signed. “Congresswoman Tlaib has been a strong leader in fighting for comprehensive health care coverage, Medicare for All, lowering prescription drug costs, and eliminating medical debt. She supports completely ending surprise medical billing, and supports the efforts of Congress and the Biden Administration to work together to stop surprise billing that hurts so many residents,” a spokesperson for Tlaib wrote to The Intercept. “She had no intention of undermining meaningful action to bring relief to families across the country, and will continue to fight for bold action on this issue.” Lee’s office did not respond to The Intercept’s request to clarify her position. But the bill’s author, House Energy and Commerce Chair Pallone, and Senate Health Education, Labor, and Pensions Chair Patty Murray, D-Wash., have pushed back. In an October letter of their own, the two applaud the administration in similarly legalistic writing. They write that the arbitration rule “is consistent with our intent and our determination that the QPA,” or payment amount, “represents a reasonable rate for services in a vast majority of cases.” In the past, courts have typically deferred to executive agencies when faced with ambiguous statutes, but the Trump-stacked federal courts and the conservative Supreme Court are likely to be hostile to any regulation that appears to open the door for federal rate-setting. For their part, health care analysts have largely been dismissive of the providers’ reasoning. Pollitz, who authored a thorough guide on how the No Surprises Act will be rolled out this year, suggested that industry experts expected the administration to enact the dispute resolution resolution provisions similarly to how they ultimately implemented the rule. In her view, the administration’s guidance is consistent with the statute. “I guess courts will hear arguments otherwise and decide, but the administration did not just pull this out of thin air by any means,” she told The Intercept.

READ MORE

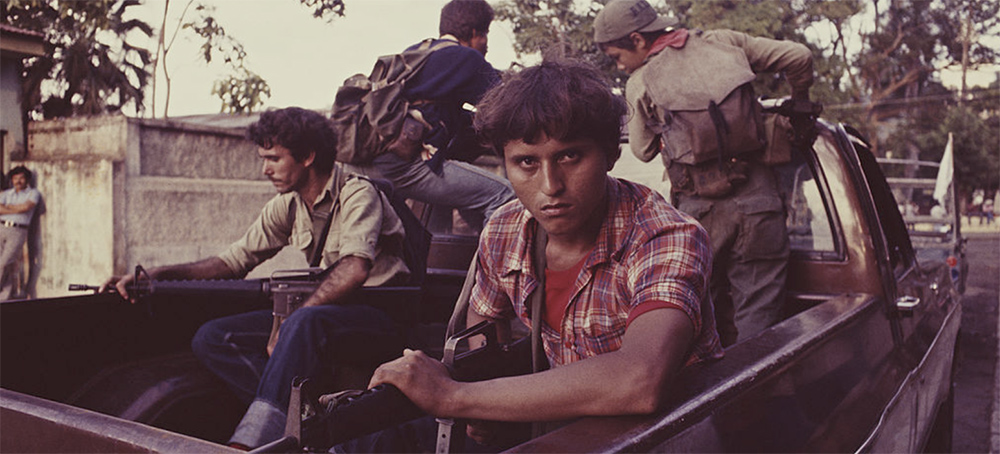

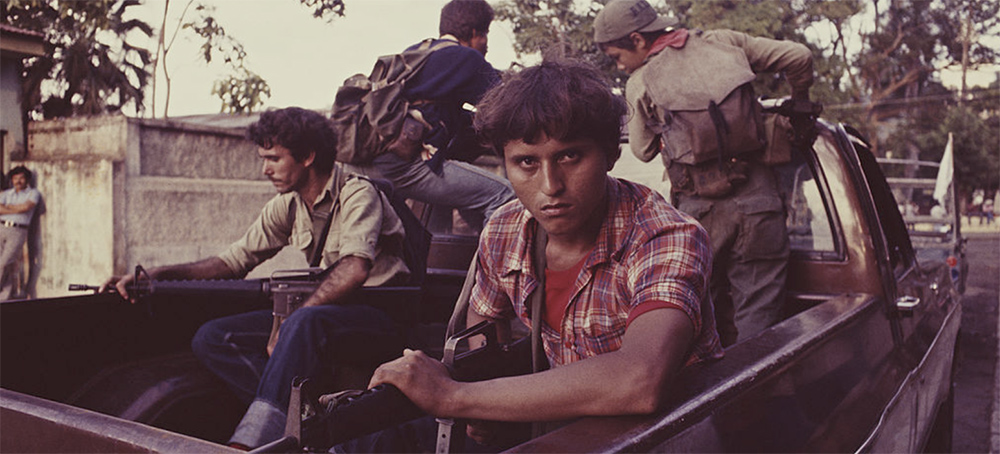

Guerrilla fighters in El Salvador during the country's civil war, 1983. (photo: Scott Wallace/Getty Images) Guerrilla fighters in El Salvador during the country's civil war, 1983. (photo: Scott Wallace/Getty Images)

El Salvador's Democracy Was Hard-Won. Now President Nayib Bukele Threatens It.

Hilary Goodfriend, Jacobin

Goodfriend writes: "Today marks 30 years since the end of El Salvador's civil war, which claimed over 75,000 lives. Nidia Díaz, a leftist guerrilla tortured by state forces during the conflict, discusses the war and how the democratic gains of that struggle are being undermined." Today marks 30 years since the end of El Salvador's civil war, which claimed over 75,000 lives. Nidia Díaz, a leftist guerrilla tortured by state forces during the conflict, discusses the war and how the democratic gains of that struggle are being undermined. January 16, 2022, marks the thirtieth anniversary of the signing of the peace accords that brought El Salvador’s civil war to a negotiated close. The twelve-year conflict between the US-backed right-wing military dictatorship and the leftist guerrilla insurgency left seventy-five thousand dead and eight thousand disappeared, with hundreds of thousands more displaced. In 1993, the United Nations Truth Commission report attributed at least 85 percent of that violence to state security forces and their associated paramilitaries. The peace accords did not modify the unequal and dependent structures of accumulation in El Salvador, but they did open a new arena of peaceful political struggle. The agreement demilitarized the Salvadoran state, establishing the constitutional bases for liberal democratic institutions. It enabled the demobilization of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), the leftist front the guerrillas were operating under, and its conversion into a legal political party, which, nearly twenty years later, came to govern the country for two terms (2009–2019). Today those democratic gains are being rolled back. Authoritarian populist Nayib Bukele became the first postwar president to not commemorate the signing of the peace accords, which he dismissed as a “farce.” Instead, he frames both the war and the peace agreements as a conspiracy between two equally corrupt and elite factions. Over the course of his two and a half years in power, Bukele has dedicated his government to the remilitarization of the state, the dissolution of the separation of powers, and the criminalization of his opposition, resurrecting the specters of dictatorship. On January 16, 1992, Nidia Díaz was among the ten FMLN representatives who negotiated and signed the peace accords at the Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City. Díaz, the nom de guerre permanently adopted by María Marta Valladares, represented the Revolutionary Party of Central American Workers, one of the five political-military organizations that constituted the FMLN. By that point, she was well known for I Was Never Alone, the published account of her capture, detention, and torture by the state. Díaz would go on to become the FMLN’s vice presidential candidate in 1999. She has served as a representative of the FMLN in the Central American Parliament and the Salvadoran Legislative Assembly, where she led the FMLN legislative group from 2018 to 2021. In this interview with Jacobin contributing editor Hilary Goodfriend, Díaz reflects on the war and the negotiation process, the achievements and limitations of the accords, and their current reversals. HG: To address the peace process, we should probably begin with the war. Why, in that historical moment, did people take up arms in El Salvador? ND: Why did we Salvadorans confront each other, as children of the same nation? The causes have a structural origin, accumulated over two centuries — to give a starting point, particularly since the year 1932, a historic milestone that culminated in a popular insurrection that was quashed by the dictatorship that ruled for sixty years. That insurrection failed, but because it was crushed militarily in a massacre of over thirty-two thousand indigenous peasants. It was a period of vagrancy; there was no work. There was a global depression that had a national impact. There was exclusion and marginalization. Wealth was concentrated in the land, in a few hands. The oligarchy sought to maintain its power. Ten years passed. A 1944 strike, the brazos caídos strike, brought down the dictator, but the dictatorial forms of domination remained. There were efforts to legalize the Left in the 1960s, but they failed. The international context also had an influence: the Cuban Revolution, the processes of armed struggle in Colombia, and more. The Left began to rethink its path to power. It was no longer just legal participation in elections. Instead, it could also be the path of armed struggle. There was a big debate within the Communist Party, which had waged enormous struggles, both legal battles and from underground. The whole debate was over the construction of a party, the revolution, and the strategy and tactics of struggle. By 1975, all five of the organizations that would form the FMLN five years later had been formed. This whole struggle was underground — it was guerrilla warfare. But it was more focused on empowering the development of social struggle and popular organization because we really didn’t want a war — we wanted a social and political struggle. We combined forms of struggle. The exhaustion of the political struggle was demonstrated by the electoral frauds of 1972 and 1977. The massacres began. People rallied around the National Opposition Union, which was an alliance between the Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, and the legal face of the Communist Party — this was the form the Left took. The sectors in power moved to halt this popular advance; by this point, they formed death squads. In 1977, they carried out a large massacre to impose another dictator who had massively lost the elections, General Humberto Romero. Afterwards, they established a curfew, martial law. Everyone condemned that massacre, even Monseñor Óscar Romero, who had just been named archbishop of San Salvador and who everyone thought was conservative. Days later, they killed Father Rutilio Grande — who is about to be beatified. At that time, President Jimmy Carter governed in the United States. Carter suspended aid to El Salvador in 1979 over human rights violations. On October 15, the last military coup in El Salvador took place, to depose the dictator. A revolutionary civilian-military junta was proposed, and many leftists entered the government. But by the end of December, the Left began to resign from the junta. The traditional military members start coming back. The second junta then committed itself to genocide. That year [1980], the Revolutionary Mass Coordinating Committee (CRM) was founded, and, on January 22, it’s repressed, there’s a massacre. Days later, the leader of the Christian Democratic Youth is assassinated. On March 24, they kill Saint Óscar Romero, who had become not only the “voice for the voiceless” but also a facilitator of peace, because he had the capacity to dialogue with diverse sectors and was seeking a political resolution to the large confrontation that was coming. On April 18, the Revolutionary Democratic Front (FDR) was founded, an alliance between the Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, the political face of the Communist Party, the CRM — a big alliance, a broad front against dictatorship. At the same time, the FMLN unification process was underway. By now there is more dialogue between the five organizations, which had been vying to be the vanguard of the process. They were convinced that no single group was going to have traction. There had to be unity between the revolutionary forces. On October 10, the Farabundo Martí Front was founded. Immediately, it formed an alliance with the FDR, which proposed a program for revolutionary government and created a diplomatic commission to seek a political solution to the conflict. Unfortunately, Ronald Reagan won the election in the United States, and he restored military aid [to the right-wing Salvadoran government] immediately. The oligarchy then assassinated the leadership of the FDR. The climate of confrontation grew. This brought us to undertake a vast insurrectional effort on January 10, 1981. Although there was debate over whether it would be a protracted people’s war, we were social warriors above all, convinced that all this would be over soon. But we were wrong, because the empire got involved directly so as not to repeat what happened in Vietnam. Since they saw the Central American region as their backyard, they went all in. The first counterinsurgency project was to totally crush the insurrection. But that didn’t happen: we retreated, we organized, we resisted, and we began to advance. So when many people believed that the FMLN no longer had the capacity for anything, it reemerged with certain actions. It was the international community that, in August 1981, with the Franco-Mexican Declaration, recognized the FMLN as a representative force of the people’s struggle and legitimized the causes that provoked the civil war: political exclusion, socioeconomic marginalization, inequality, and North American intervention. Four different US counterinsurgency projects failed, though they were providing $2 million a day in aid by the end of the war. HG: How was is that, after planning to take power militarily, the conflict ended with a negotiated solution? ND: Everything depended on the balance of power. In defeating four counterinsurgency strategies, we had a revolutionary program to achieve: the democratic revolutionary government. In 1984, we changed to a “provisional government with broad participation.” In 1989, we no longer waited to be in power to hold free elections; we made a proposal to participate in elections in the midst of the war. But the war continued, and the factor that prolonged it was the North American intervention. If they had cut off aid and hadn’t salvaged that army, we would have defeated them militarily, because, in 1983, we wiped out the positions of the civil defenses, the paramilitary groups. So yes, we had our hopes, but reality was different. Many people say, “Why did you negotiate instead of taking power?” Well, the more prolonged the war became, the less people wanted it. War is a state of exception that destroys human life. There is a high social cost. We ended up with eighty thousand dead, eight thousand disappeared, many exiled. Families were torn apart; we had many political prisoners. So we took advantage of the balance of forces in which we were situated as two equal parties to negotiate a political solution. But I want to say this: if we hadn’t continued the armed struggle until the very last day, we wouldn’t have forced the oligarchy and the army to reform themselves, to cede. Because even a comma was decided with bullets. And for that reason, that national liberation struggle had a high price in blood. It was never a farce, not for anyone. It was between the Salvadoran state and the representative forces of a people. After the Franco-Mexican Declaration, we sent a letter to the UN General Assembly that was read by Daniel Ortega, president of Nicaragua, in which we offered to open talks [on October 4, 1981]. But the first dialogue wasn’t until 1984. The counterinsurgent project was in crisis; the US was reassessing its aid, which at that point was a little over $1 million a day. It had trained all the battalions, and they had immorally legalized the presence of fifty-five permanent military advisors in the country, although in reality it was more like three hundred — one of them was the American who participated in my capture: Félix Rodríguez, Cuban American. In this context, [President José Napoleón] Duarte offered to talk. On October 15, 1984, the first dialogue took place in La Palma, mediated by the Catholic Church and the whole diplomatic corps. Duarte proposed we lay down our arms and adhere to the new 1983 constitution. We said no — because I was at this first dialogue, too — we hadn’t gone to discuss our weapons, we had gone to discuss the causes of the war, and we could not adhere to that constitution because it gave supreme power to the military and did not recognize basic rights and freedoms. The meeting ended there. The following month, there was another dialogue in Ayagualo; the FMLN proposed a constitutional reform to demilitarize the country, and Duarte rejected it in ten minutes. The talks broke off. Three years later, another dialogue occurs: Esquipulas II. They wanted us to lay down our arms in order to talk. We didn’t accept. Finally, they relented, and Duarte agreed to talk while we remained armed. In the midst of those meetings, they killed the president of El Salvador’s Human Rights Commission. The FMLN broke off the talks, saying we can’t engage in dialogue while they’re killing people. The three talks with Duarte ended there. Dialogue was reopened in 1989, now with [President Alfredo] Cristiani. The first talks were without mediation — just the two delegations, face-to-face. We agreed to meet again in October in Costa Rica. There the Catholic Church was back, with observers from the UN and the Organization of American States, but the army wouldn’t sit at the table. From the first Cristiani delegation in September 1989 to the signing of the peace accords, General [Mauricio] Vargas would show up, but he’d sit in the back. He couldn’t be at the same table as the insurgents. At the global level, we were under a lot of pressure from social democrats to sign the agreements for nothing, because the Berlin Wall had fallen, all was lost in the socialist world, etc. They believed that our problem was an East-West conflict, but we had different structural problems, and we said no, but that we would go to another meeting. The oligarchy and the Right said that there had to be a ceasefire in order to open talks. We said no, but that we’d go to another meeting. We scheduled one for November, but, on October 30, they put a bomb in the National Union Federation of Salvadoran Workers [killing nine labor organizers, including union leader Febe Elizabeth Velásquez]. We broke off talks and prepared an offensive to change the balance of forces. At that moment, we were looking to concentrate all our efforts in order to change the course of history. So, on November 11, 1989, we launched a vast offensive called, “Febe Elizabeth Lives. Hasta el tope y punto.” They responded with repression, choosing to bomb the city’s periphery; they killed the Jesuits, they killed a lot of people. Four months later, the balance was realigned, and the possibility for real negotiations opened, now with the intervention of the United Nations as a third party. We negotiated from April 4, 1990, to January 1992, practically two years. HG: Can you comment on the contents of the accords, their scope and their limits? ND: To begin with, a negotiating format was established of equal conditions of the parties, with four objectives: finalize the armed conflict through political agreements that addressed the causes that started the civil war; that those agreements propel the democratization of the country; that they include full respect for human rights; and, with that basis, achieve democratic coexistence and the reunification of society. With that, a ten-point agenda was established: the demilitarization of the country; human rights; the judicial system; the electoral system; constitutional reforms; the socioeconomic problem — all of that covered the entire society, those six agreements. The others were the ceasefire, the process of FMLN demobilization; the process of reducing the army; and the FMLN’s conversion into a political party. Also, electoral verification and observation, and the calendar, the schedule. The FMLN agreed that for every 20 percent of the political agreements fulfilled, there would be a demobilization of 20 percent of the guerrilla forces, who were integrated into economic or political activities, or the National Civilian Police. Our negotiations took place in war, not in peacetime. We sought for each of the agreements to have constitutional backing, at least when it came to the political elements. We did not achieve the balance of power necessary to make economic constitutional reforms. We were reforming a counterinsurgent constitution for a bourgeois state. We weren’t making a new constitution. But all those agreements went in the direction of a social, constitutional, democratic state. The constitution already included important rights from the 1950s. In fact, in the socioeconomic order, it was established that private property would be respected insofar as it had a social function. Four different forms of property were recognized. The economic points that we had wanted to include were the reduction of private property from 254 hectares to 100 hectares; the human right to food and the human right to water, as public goods; the right to strike for public sector workers; the freedom to unionize for peasants. But we lost those. We did make an agreement to begin democratizing the economy just a little, related to the creation of a socioeconomic forum to discuss issues like salaries, pensions, the legalization of urban land titles; public land was to be given to the peasants, and all combatants and people who lived in areas of conflict would get land and credit. The oligarchy and the military resisted the reforms. After the agreements were signed, there were two transitions: the democratic transition of the peace accords, including respect for participation, for liberties, clean electoral contests — whichever project or program achieved greater hegemony among the people would win, but no more fraud, and never again the militarization of voting centers — strengthening institutions, separation of powers, the system of checks and balances, etc. And the other part: the neoliberal economic transition, which made the poor poorer and the rich richer. When the FMLN won the elections eighteen years later, we found the economy contracting at 3.6 percent. It was a tremendously unequal country, living off remittances; we no longer grew basic grains, we imported everything. It was a violent country, because one deficit of the peace accords was not having practiced a culture of peace. What came was a culture of violence. By not fulfilling the Truth Commission’s recommendations, impunity continued, the judicial branch wasn’t adequately cleaned up, and the drug trade entered, as well as arms sales. The gangs came from the United States. We encountered all that when we entered the executive office — which is not the same as taking power. HG: Nayib Bukele’s government rejects the peace accords. He is known for his authoritarian consolidation of power, but also for his high approval ratings. In your view, how does the current moment compare to the authoritarian period prior to the conflict? What are the similarities and what are the differences that you would highlight? ND: To begin with, the main difference is the socioeconomic system, in the sense that the oligarchy no longer bases its wealth in land, but rather in financial speculation and some commerce. But it remains an oligarchy. Also, the high level of remittances now sustain the consumer economy. But in the form of the regime of domination, it’s true that the military is no longer in office, but power has an authoritarian form when an economic group controls the political power — one group that’s established, and another that is emerging. How do we compare this to the past? What were the causes of political exclusion? The centralization of power. They controlled the legislature, the executive, the judiciary, etc., and their interests prevailed, without concern for respecting rights, freedoms, institutionality. There was no separation of powers, no checks and balances, no system of freedoms and civil and political rights. Before, for example, whoever criticized would be disappeared, killed. Even having a stamp of Saint Romero was a crime. All forms of peaceful social struggle were criminalized. The climate of persecution was real. Now, comparing it with today, the regime has attempted to control people’s thinking. Whoever opposes or criticizes is now seen as an enemy — not as a political adversary, but someone to be destroyed. In the peace accords, holding political prisoners is prohibited. So he uses lawfare, judicial warfare; he uses the judicial branch to trump up charges against politicians, even if they are unjustified or not defined in the penal code. He has usurped the judicial branch, when the peace accords guaranteed its independence. What happened on May 1, 2021, [when Bukele seized control of the Supreme Court and other top judicial officials] was a flagrant violation of the peace accords, a rupture. Now, they removed a judge for not agreeing to hear a frivolous lawsuit, or they removed the judge who oversaw the El Mozote trial. Then there’s what happened on February 9, 2020, when the president wanted to force the legislators to vote. To use the army like he did and like he does, when it no longer should have those functions, is serious. He also breaks with the peace accords when he wants to double the size of the army, when it was agreed that an army in peacetime should be decreasing, not increasing, and should not engage in public security functions. He doesn’t care about violating the constitution and those reforms. Later, he justifies himself, saying he doesn’t believe in them, that it was a corrupt pact, that it only served to enrich them. He tries to justify his own theft. For example, he changed the functions of the Institute for Access to Public Information; he cleaned out the Government Ethics Tribunal. In the end, he’s trying to obtain resources to facilitate accumulation for his group in power. All those laws that oversee the new institutions that are the product of the peace accords were made in COPAZ, the National Peace Commission. They weren’t a whim. In COPAZ, you had the FMLN and the government as parties, and, as observers, the Catholic Church and the UN and the parties that were in the legislature at that moment. All the laws — the law for the National Civil Police, the army, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, the Human Rights Ombudsman, etc. — were made in COPAZ and sent to Congress. There was a debate process. Now Bukele comes along and says, “I don’t agree with these responsibilities and powers,” and he tries to annul the laws and the constitution. He’s dismantling the democratic process that permitted his very election. We see the persecution of the church today, of journalists. He wants to outlaw the real opposition parties, the FMLN as the Left in this country, and also the party that the oligarchy has used until now. Today, the new right is reconfiguring itself in [Bukele’s] New Ideas party. His [proposed] reelection is a trampling of the constitution that one way or another has allowed the system to work. “Which system?” you might ask. The capitalist system, it’s true. But it’s what allows you to struggle for now. The fundamental problem is, what do you want power for? And what does Bukele want power for? We’re facing a situation of the flagrant violation of institutionality and the law, not with the goal of a more revolutionary, more transparent, more participative, more just democracy, but to make themselves richer, to have more power over the population. The FMLN has always fought for a more transparent, more participative democracy. We’re in favor of implementing the referendum, for example, but not to centralize power but really democratize the country. What [Bukele’s government] presented in its proposal for constitutional reform is more centralization of power in the service of economic interests. HG: Some observers try to classify Bukele as a counter-hegemonic actor, especially since he’s adopted an apparently anti-imperialist discourse in his disputes with the Biden administration. How would you characterize this? ND: He has a secondary contradiction with the hegemonic power. Trump tolerated that Bukele did not comply with two of the requisites of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle. Of the plan’s five points — prosperity, security, migration, transparency, and institutionality — he did not fulfill two, but Trump didn’t care. Now, facing demands that he be accountable, that he not permanently violate his institutions, he says, “They want to tell me what to do.” There’s the contradiction, but it has a limit. The United States is never going to place a blockade on El Salvador like they have in Cuba, but they are paying attention because of the pressure that the administration is under from more progressive sectors. Biden has an electorate to please, just like Trump. But I have never seen a central or principal contradiction between the United States and Bukele. At first, Bukele presented himself as a man of the Left. But what have we seen in his foreign policy? He broke off relations with the Saharawi Republic, and he didn’t allow the opening of a Palestinian embassy; he broke off relations with Venezuela, he removed the Cuban social programs. He saw that ambassador that Trump sent to El Salvador as a buddy. He’s conservative. Before taking office, when he went to Israel, to the wall, he — the son of Palestinians — stood on the Jerusalem side and not the Bethlehem side. All the delegitimization and rejection of the people’s struggle, saying that it’s a farce, and the rejection of the constitutional reforms and institutions created by the peace accords and the laws that back them, is to justify his robbery of the state, and his authoritarian, messianic regime. He says he is sent by God, he says he’s the coolest man in the world, etc., but in the end he isn’t working toward more democracy, social justice, or rights. He doesn’t want to be questioned, and the institutions designed to question or investigate, like the human rights ombudsman, the Auditing Court, or the general ombudsman, have been neutralized, because if they say something, they’re out. He wants to sow fear, so that people do not resist. It’s a form of neutralizing the Left, neutralizing a struggle. But we live in a moment when people have also begun to question. People will go out into the streets to defend the peace accords. They will go out and express themselves, like they did on September 7, when the Bitcoin law went into effect, on September 15, October 17, December 12, and now January 16. More democratic sectors are joining in. Bukele has an incredible ability to manipulate, to communicate with the people. But many people are starting to understand. People are tired. We need to defend history, historical memory. Today he is destroying monuments. He doesn’t recognize the liberation struggle, nor the agreements between the state and the FMLN as a representative force that was recognized by the international community. He doesn’t respect the memory of our heroes and heroines. He sees them as criminals, living and dead. If the people don’t have historical memory, because of the absence of a real historical memory program and because the FMLN could not create a hegemonic culture among the people, then we have this situation today.

READ MORE

A French scientist shows microplastic waste collected on the Aquitaine coast on the beach of Contis, southwestern France. (photo: Mehdi Fedouach/AFP/Getty Images) A French scientist shows microplastic waste collected on the Aquitaine coast on the beach of Contis, southwestern France. (photo: Mehdi Fedouach/AFP/Getty Images)

Microplastics Can Pollute Rivers for Seven Years Before Entering Ocean, Study Finds

Cristen Hemingway Jaynes, EcoWatch