Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

As distrust in the government and its elected officials rises, a growing number of Americans are taking the law into their own hands.

Chillingly, he writes, the objective of the Jan. 6 rioters was not to push back against an authoritarian House and Senate. It was to substitute the mob’s authority for that of the forces they believed had stolen the 2020 election, including election officials, state authorities, federal and state judges, and the entire Justice Department. The rioters felt justified in storming the seat of government because the government was not doing its job. Because Vice President Mike Pence had declined to decertify the election results, they were persuaded that they needed to do it for him. Hence the gallows. It’s why “Hang Mike Pence” became the battle cry. Having failed to “stop the steal,” the state had failed them. So it was time to take matters into their own hands. Restoring individual liberty by overthrowing a hapless government was the new freedom.

2021 was a banner year for citizen vigilantism, from the self-styled insurrectionists, who believed that freedom required maiming and killing police officers at the Capitol, to Kyle Rittenhouse, who believed that if the police in Kenosha couldn’t put down a race riot, it was incumbent on teens to take up weapons of war to do it in their stead. It was a banner year for violent vigilantism, as a young man at a rally in Idaho this fall stepped up to ask when it would be OK to start shooting Democrats. “When do we get to use the guns?” The questioner asked Turning Point USA’s Charlie Kirk. “How many elections are they going to steal before we kill these people?” Election workers describe violent threats from stop-the-steal “patriots” that have driven them from office in record numbers. The menace of those who believe that the time has come to take the law into their own hands has become part of the daily political calculation of what it means to be part of a democracy.

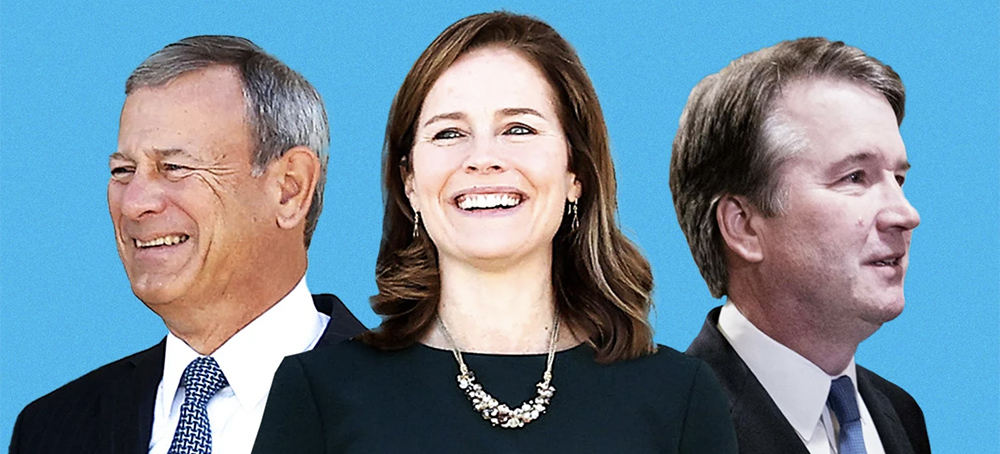

2021 was also a banner year for vigilantism blessed by the U.S. Supreme Court, which voted not once but twice to permit Texas’ novel S.B. 8 to remain in effect. S.B. 8 is an anti-abortion law, sure, but also one that supplanted virtually all state enforcement with citizen vigilantes, who are now tasked not just with suing abortion providers but also anyone who aided or abetted an abortion, up to and including counselors and Lyft drivers. (These vigilantes stand to collect at least $10,000 in cash for their efforts.) During oral arguments in the case in November, it was Chief Justice John Roberts, no fan of abortion rights, who asked Judd Stone, the solicitor general of Texas, to “assume that the bounty is not $10,000 but a million dollars.” That Roberts himself used the word bounty confirmed that this is precisely what the state put in place. Texas built a bounty system, allowing citizens to be deputized as law enforcement, not simply because the state sought to evade judicial review but also because who’d be better to turn in their friends and neighbors than a vigilant, empowered citizenry?

“It is beyond unfortunate that the Supreme Court’s reaction to a country that is so torn apart that it had an insurrection on Jan. 6, their reaction is ‘oh, this seems like a good time to allow vigilante litigation,’ ” appellate lawyer Richard Bernstein told Courthouse News after S.B. 8 was approved by the majority. “They have sanctioned a form of state-sponsored political warfare that the rest of the society is left to keep from getting out of hand with no help from the Supreme Court.” And yet merely through this act of sanctioning the political warfare, the Supreme Court is very much helping the ascendant vigilante faction.

At the time it was enacted, I classed S.B. 8 as part of the larger trend of rewarding and encouraging vigilantism, whether through an ever-widening definition of what “stand your ground” defenses can mean or newly passed election laws that allow citizens to police how their fellow citizens vote. Scott Pilutik, writing this fall, flagged multiple state laws that would conscript ordinary Americans into law enforcement proxies:

In Tennessee, students and teachers can now sue schools if they “encounter a member of the opposite (biological) sex in a multi-occupancy restroom.” In Florida, any student who claims to have been “deprived of an athletic opportunity” because a transgender athlete took their place is now bestowed with a private cause of action against the school. Missouri recently passed the “Second Amendment Preservation Act,” which not only serves as an assault on the supremacy clause, but grants $50,000 in damages to any party whose right to bear arms is deprived. And Kentucky citizens can now file a complaint with the attorney general if a teacher within their school district teaches critical race theory resulting in withdrawn funding from the school.

In April, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law a bill that creates civil immunity for people who drive their cars into crowds of protesters (later declared unconstitutional). This past fall Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed an elections bill into law that broadened protections for partisan poll watchers, allowing them to sue poll workers hired by the government. Amanda Hollis-Brusky, politics chair at Pomona College in California, described the regime as creating an “alternative structure of government.” The object of these enforcement mechanisms is to “invite intensely organized partisan interest groups to basically organize the behavior of citizens and funnel that through the courts rather than the state.”

This shifting of powers, from police to private actors, and from state actors to the courts, is part of the broader rise of vigilantism that sometimes goes unnoticed in the larger debate over public mistrust of institutions. It’s not just a rolling loss of public confidence in free and fair elections, or in law enforcement, or in educational policies set forth by school boards, but a move to the courts system to enforce private causes of action.

It is hardly shocking that as American trust in any and all institutions collapses, what surges into the vacuum is self-help of the sometimes-armed variety. “If our election systems continue to be rigged, and continue to be stolen, then it’s going to lead to one place, and it’s bloodshed,” GOP Rep. Madison Cawthorn promised this past summer. That is the language of Jan. 6 and it’s the language of early American policing and a long American history of extrajudicial violence from the Fugitive Slave Acts to state-sanctioned lynchings to the Tulsa race riot. So deeply is the spirit of vigilantism braided into American ideas of power and law enforcement that it is readily mistaken for patriotism and rule of law.

The spirit of vigilantism is encouraged—paradoxically—by government power at the same time it blossoms with the mistrust of government. But through another lens, it becomes clear that even this paradox is nothing of the sort. The sense that white skin affords anyone and everyone the right to be a law unto himself, and that Black skin comes with no such privileges, is part of America’s founding legal principles. When you hear that there has been an explosion in laws allowing you to hit protesters with your car, or shoot unarmed people at a racial justice march, or stride around public spaces armed to the teeth, you can be certain that the self-appointed law enforcers will be treated differently based on race.

Reporting recently on the growing lawlessness of the self-styled “constitutional sheriffs” who arrogate to themselves the power to decide what the law is, the Washington Post’s Christy E. Lopez warns that recent activities ranged from supporting the Jan. 6 rioters to recruiting other constitutional sheriffs to seize Dominion voting machines in 2020. And in this high water moment of QAnon and the cult of do-your-own-research, the sense that there are no facts, there is no science, and no agreed-upon norms of conduct allows citizens to substitute their own subjective views about what the law should be in the place of mutually agreed-upon and fixed ideas about what the law actually is. Just as COVID turned every American into a licensed epidemiologist, legally sanctioned vigilantism turns everyone into an expert on and arbiter of whatever law or institution they’re railing against at the moment. And if the Rittenhouse verdict taught us anything at all, it may be that jurors are evermore inclined to accept those subjective judgements as reasonable. This is not, in other words, a static state of affairs. Vigilantism creates doubt about state authority, and doubt about state authority fosters evermore vigilantism.

If professor Erwin Chemerinsky, writing on the recent surge in vigilantism, is correct in arguing that the only sane path forward is to work toward restoring faith in government, one is left to wonder what role the Supreme Court has played and will continue to play in fostering the sense that by and large, government is the problem as opposed to the solution. And here is where it’s almost impossible to ignore the anti-government rhetoric that seems to be ascendant among the court’s conservative wing, whether it’s the increasingly vocal doubt about the wisdom of Chevron deference to reasonable agency interpretations of the law, or the embrace of the nondelegation doctrine that calls for courts to strike down any and all laws that delegate too much power to the federal bureaucracy. This anti-government spirit is showing up in claims that government officials expressly seek to harm and demean citizens with vaccine mandates or in false and debunked rhetoric about election fraud.

The court didn’t begin to greenlight citizen self-help in the S.B. 8 decisions. This is a decadeslong project. At oral arguments about vastly expanding the rights of gun owners this fall, Justice Samuel Alito suggested that state licensing agents were apt to grant gun rights to “celebrities and state judges and retired police officers” but not to “the kind of ordinary people who have a real, felt need to carry a gun to protect themselves.” Alito further noted that “all these people with illegal guns, they’re on the subway, they’re walking around the streets. But the ordinary, hard-working, law-abiding people I mentioned, no, they can’t be armed.” The bad guys, in Alito’s telling, aren’t the criminals anymore. The bad guys are the corrupt or clueless state licensing agents and the corrupt and clueless police departments. This is the language of bad faith and incompetence that pervades their discussions of public health officials and election officials.

It would be a special kind of tragedy if the very same Supreme Court that relies wholly on public confidence in its institutional legitimacy were helping plant the seeds of institutional mistrust of other democratic pillars of representative democracy—the sanctity of elections, the rule of law, the urgency of public health, regulatory authority, and the continued need for, as Justice Elena Kagan has tartly put it, “most of government” to be viewed as constitutional and vital. The long strain of individualism, libertarianism, vigilantism, and citizen law enforcement that has characterized the American legal story for centuries has always had the capacity to reassert itself on a dime. Jan. 6 was proof positive that it bubbles forever just under the surface and explodes periodically into violent, lawless action.

The Supreme Court will either play a role in quelling that tendency in the year ahead, or continue to signal that every citizen is largely a law unto themselves, that the rule of law is for sheeple and suckers and socialists and atheists—but for everyone else, the sole remaining question might just be only “when do we get to use the guns?”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611