Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The country was hours away from a full-blown constitutional crisis — not primarily because of the violence and mayhem inflicted by hundreds of President Donald Trump’s supporters but because of the actions of Mr. Trump himself.

In the days before the mob descended on the Capitol, a corollary attack — this one bloodless and legalistic — was playing out down the street in the White House, where Mr. Trump, Vice President Mike Pence and a lawyer named John Eastman huddled in the Oval Office, scheming to subvert the will of the American people by using legal sleight-of-hand.

Vice President Kamala Harris. (photo: Getty)

Vice President Kamala Harris. (photo: Getty)

The 92 scholars called on Harris, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Senate President Pro Tempore Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) not to "overrule" Parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough, whose rulings are non-binding, but for the presiding officer of the Senate to issue a ruling contrary to her advice.

"As you know, the Vice President serves as Presiding Officer when she is in attendance, and the President pro tempore or his designate serves as Presiding Officer at other times," wrote the scholars.

At issue is language that MacDonough ruled on Sept. 19 were incompatible with the rules of budget reconciliation bills.

That language, if enacted into law, would have allowed the federal government to offer legal permanent residency (LPR) to around 8 million undocumented immigrants and immigrants on humanitarian parole programs who are not currently eligible to apply for permanent residency.

MacDonough said such a move would be a substantial change in policy, and would be extraneous to the strictly-budgetary requirements known as the Byrd Rule, limiting which provisions can be included in a reconciliation bill.

"When determining whether a provision is extraneous, the Presiding Officer may rely on the Senate Parliamentarian for expert advice," wrote the scholars. "However, as past Parliamentarians have emphasized, the ultimate decision on a point of order lies with the Presiding Officer, subject to appeal to the full Senate."

"The Presiding Officer therefore must exercise her own judgment in deciding whether a provision should be stricken from a budget reconciliation bill on Byrd Rule grounds," they added.

Reconciliation would allow Democrats to sidestep a Republican filibuster, and many immigration advocates believe the current political climate grants a unique opportunity for reform on the issue, which might not repeat itself in years.

While immigration provisions have not been at the center of intra-party debate on the reconciliation bill, particular groups of Democrats in the House and Senate have fought to include immigration in the bill.

MacDonough has so far struck down two separate proposals to grant LPR through relatively vague memoranda, among other things arguing that a permanent status would have such non-budgetary impacts as to outweigh its budgetary effects.

The scholars wrote that the parliamentarian cannot make a final authoritative determination on that point — that only the presiding officer or the full Senate on appeal can do so. To defeat any appeal to the presiding officer's ruling, Senate Democrats would need 51 votes, meaning Harris would have to be present and presiding over the Senate to cast the tie-breaking vote.

And the scholars argue the budgetary effects of granting LPR status to millions of people would be more than substantial.

"The outlay and revenue effects of extending LPR status to 8 million people are sweeping. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the budgetary effect of the LPR provisions would be $140 billion over the next 10 years — more than the entire effect of some statutes enacted through budget reconciliation in the past," they wrote.

The scholars listed a series of social programs and taxes that would be directly affected by granting LPR status to a large population, from the Affordable Care Act to increases in tax revenues from workers with better salaries.

Although the Byrd Rule does not allow for provisions with a "merely incidental" effect on the budget, the scholars argue the scope of a broad legalization package would have a direct and substantial impact on the federal budget.

"We see no basis in law or precedent for concluding that these outlay-related effects are 'merely incidental' to LPR status. Access to health insurance, homeownership and affordable rental housing, higher education, and income security cannot be characterized as 'chance or minor consequence[s].' They are, along with the non-budget-related benefits that the Parliamentarian canvassed, key elements of lawful permanent residence," they wrote.

Still, the group — which includes former Democratic Sen. Russ Feingold (Wisc.) — wrote that the Democrats presiding over the Senate should not "overrule" MacDonough, rather take the responsibility for implementing the Byrd Rule.

"For the Senate to reach its own conclusion on the Byrd Rule’s application to [immigration provisions] should not be seen as an 'overruling' of anyone. Rather, it would recognize that elected members of Congress are ultimately responsible for deciding whether to enact legislation, in accord with statutory constraints, the advice of civil servants, the voices of their constituents, and their own considered judgment," they wrote.

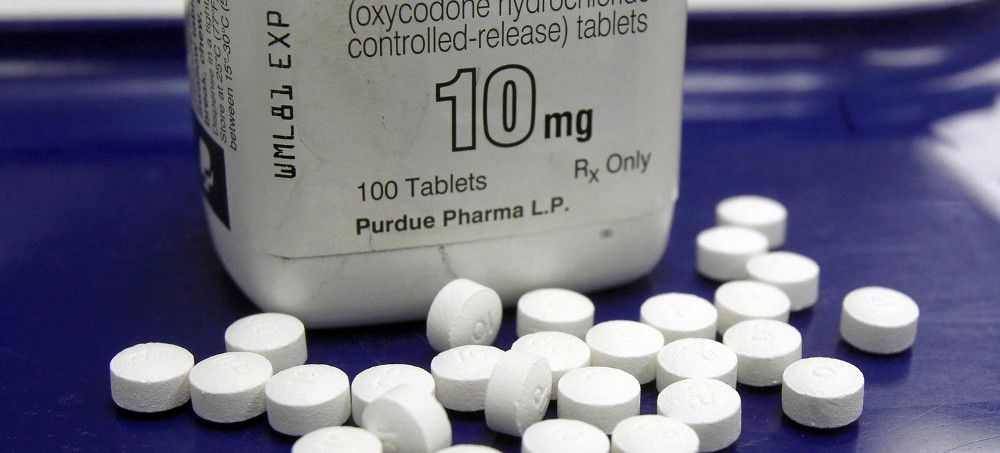

US senators are questioning the Food and Drug Administration's work with a consulting firm that helped businesses sell prescription painkillers during the nation's overdose crisis. (photo: Toby Talbot/AP)

US senators are questioning the Food and Drug Administration's work with a consulting firm that helped businesses sell prescription painkillers during the nation's overdose crisis. (photo: Toby Talbot/AP)

The consulting giant was helping Purdue Pharma and Johnson & Johnson fend off FDA regulations even as it helped shape FDA drug policy.

During that same decade-plus span, as emerged in 2019, McKinsey counted among its clients many of the country’s biggest drug companies — not least those responsible for making, distributing and selling the opioids that have ravaged communities across the United States, such as Purdue Pharma and Johnson & Johnson. At times, McKinsey consultants helped those drugmaker clients fend off costly FDA oversight — even as McKinsey colleagues assigned to the FDA were working to bolster the agency’s regulation of the pharmaceutical market. In one instance, for example, McKinsey consultants helped Purdue and other opioid producers push the FDA to water down a proposed opioid-safety program. The opioid producer ultimately succeeded in weakening the program, even as overdose deaths mounted nationwide.

Yet McKinsey, which is famously secretive about its clientele, never disclosed its pharmaceutical company clients to the FDA, according to the agency. This year ProPublica submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the FDA seeking records showing that McKinsey had disclosed possible conflicts of interest to the agency’s drug-regulation division as part of contracts spanning more than a decade and worth tens of millions of dollars. The agency responded recently that “after a diligent search of our files, we were unable to locate any records responsive to your request.”

Federal procurement rules require U.S. government agencies to determine whether a contractor has any conflicts of interest. If serious enough, a conflict can disqualify the contractor from working on a given project. McKinsey’s contracts with the FDA, which ProPublica obtained after filing a FOIA lawsuit, contained a standard provision obligating the firm to disclose to agency officials any possible organizational conflicts. One passage reads: “the Contractor agrees it shall make an immediate and full disclosure, in writing, to the Contracting Officer of any potential or actual organizational conflict of interest or the existence of any facts that may cause a reasonably prudent person to question the contractor’s impartiality because of the appearance or existence of bias.”

Agency officials rely on disclosure to ensure that they have the information they need to consider whether a contractor’s other business relationships risk slanting its judgment. “Contractors have the obligation to disclose potential conflicts, and then the government has an obligation to figure out how to deal with it,” said Jessica Tillipman, an assistant dean and government procurement law expert at George Washington University Law School.

Asked for comment, McKinsey did not assert that it disclosed potential conflicts to the FDA. But a spokesperson for the firm, Neil Grace, nonetheless maintained that “across more than a decade of service to the FDA, we have been fully transparent that we serve pharmaceutical and medical device companies. McKinsey’s work with the FDA helped improve the agency’s effectiveness through organizational, resourcing, business process, operational, digital, and technology improvements. To achieve its mission, the government regularly seeks support from additional experts who understand both the government’s mission and the industries’ practices. We take seriously our commitment to avoid conflicts and to serve the best interests of the FDA.” (McKinsey is a sponsor of ProPublica’s local virtual events programming.)

McKinsey’s failure to disclose its industry engagements deprived the FDA of the opportunity to consider whether, for example, the overlap between McKinsey’s government and pharmaceutical industry projects and the potential financial incentives at play constituted a conflict, experts said.

“For a contractor like McKinsey not to disclose the companies it is working for has all the appeal of the Addams Family on Halloween hiding Uncle Fester in the basement so as not to scare the neighborhood,” said Charles Tiefer, a professor of government contracting at the University of Baltimore Law School.

An FDA spokesperson, Shannon Hatch, said: “The FDA’s procurement activities are governed by the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR). The agency takes our role awarding contracts seriously and we work to ensure the agency maintains high standards of integrity as set forth in the FAR.”

McKinsey’s extensive opioid company consulting eventually began coming to light, starting with a 2019 ProPublica report. The firm’s opioid work has provoked widespread criticism, spawned a welter of lawsuits and led the firm to pay nearly $600 million this year to settle legal claims made by all 50 states, as well as five U.S. territories and the District of Columbia. It also prompted McKinsey to issue a statement in which the firm acknowledged that it “fell short” of its standards in advising opioid makers while also denying that it “sought to increase overdoses or misuse and worsen a public health crisis.” The firm pledged not to work on opioid-related projects going forward.

The lawsuits and public outrage have focused on the consulting firm’s efforts to help increase (or “turbocharge,” in McKinsey’s parlance) sales of Purdue Pharma’s highly addictive flagship opioid, OxyContin. But lately, concerns have begun to emerge about McKinsey’s parallel assignments, which were worth upward of $50 million over about 12 years, for the nation’s primary drug regulator. In a letter to the FDA in August, a bipartisan group of senators led by Sen. Maggie Hassan, D-N.H., asked the regulator to address “potential conflicts of interest that may have arisen” from McKinsey’s work for both the agency and “a wide range of actors in the opioid industry, including many of the companies that played a pivotal role in fueling the opioid epidemic that our country now faces.”

McKinsey, which has focused on counseling the CEOs of leading corporations for much of its nearly 100-year history, began expanding its public-sector practice in the United States around the time of its earliest FDA projects. McKinsey prides itself on its ability to act quickly and with discretion, and in its largely unregulated engagements for corporate clients, there are few impediments to the firm doing so.

In government consulting, however, the rules are far more stringent, and on several recent occasions, the firm has been caught refusing to abide by such strictures, including disclosure rules. Over the past couple of years, for example, McKinsey’s bankruptcy-advisory practice has paid more than $30 million to the Justice Department and one client’s creditors to settle allegations that it failed to disclose potential conflicts, as required by the federal bankruptcy rules. Those allegations also prompted a federal criminal investigation of the firm. McKinsey has denied wrongdoing, and the investigation, which came to light in 2019, has not led to charges.

There are signs of overlap between McKinsey’s government and industry engagements, though publicly available information about the firm’s work for drug companies is limited. In one instance in 2008, which surfaced in a lawsuit against Purdue, the FDA told Purdue that it planned to require the company to submit a drug-safety plan for its bestselling drug, OxyContin. The company recognized that regulation of this sort threatened to cut into its sales margins, and according to McKinsey documents filed in federal court, top Purdue executives tasked the consultancy with devising a response to the FDA.

According to McKinsey PowerPoint slides, the firm proposed four options, among them suing the FDA to “delay” the imposition of a safety plan and to “band together” with other opioid producers to “formulate arguments to defend against strict treatment by the FDA.” Purdue selected the latter, with McKinsey helping to implement the strategy. In 2009, McKinsey emails and slides show, its consultants prepared Purdue executives for at least two meetings with FDA officials. (One suggested answer to questions about who at Purdue would take personal responsibility for OxyContin overdoses: “We all feel responsible.”)

In the meantime, according to a 2011 FDA contract, the agency’s drug-regulation division hired McKinsey to develop a “new operating model” for the office responsible for developing drug-safety plans of the sort Purdue and its allies were fighting against, with the consultancy’s help. Among McKinsey’s tasks were defining the office’s “strategic goals and objectives,” including its “role in monitoring drug safety.”

In 2012, the FDA issued a substantially watered-down version of the opioid-safety plan.

There’s no evidence to suggest McKinsey’s consultants at the FDA influenced the opioid-safety plan. But this apparent overlap between a government contract and an assignment for a commercial client reflects the type of issue an agency would want to consider when assessing whether a potential conflict of interest exists. Agencies are likeliest to identify a conflict “where an outside business venture is related directly to the subject matter of the procurement and structured such that there is a real economic incentive for biased performance,” Keith Szeliga, a partner at the law firm Sheppard Mullin, wrote in a 2006 article in the Public Contract Law Journal.

A number of other McKinsey projects at the FDA, contracting records show, were also likely to have a financial impact on its pharmaceutical industry clients. In 2010, for example, the FDA hired the firm to help it develop a system to track and trace the distribution of potentially harmful prescription drugs. The contract required the firm to consult with “supply chain stakeholders,” a category that potentially included a number of long-standing McKinsey clients. Hassan and her fellow senators, in their recent letter to the FDA, called this “an obvious conflict of interest.”

Another contract, from 2014, tasked McKinsey with assessing the “strengths, limitations and appropriate use” of Sentinel, a system meant to monitor the safety of drugs once they’re on the market. That project likewise called for McKinsey to interview “external stakeholders,” including “industry organizations” and “drug and device industry leaders.”

The news of McKinsey’s opioid work apparently did little to dampen the FDA’s enthusiasm for the consultancy. In March 2019, just after the news broke, the agency signed a new contract with McKinsey — extending the firm’s multiyear effort to help the FDA “modernize” the process by which it regulates new drugs.

Marchers against mandates and some other things crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. (photo: Michael M. Santiago/Getty)

Marchers against mandates and some other things crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. (photo: Michael M. Santiago/Getty)

During a march against vaccine requirements, some New York City firefighters fist-bumped protesters and at least one law enforcement officer cheered.

Video journalists Sandi Bachom and Brendan Gutenschwager captured footage of the tent destruction, which took place in Union Square at around 4 p.m. A spokesperson from the New York Police Department told VICE News that the incident was under investigation and nobody was injured. The FDNY did not respond to VICE News’ request for comment about the fist-bumping incident.

The protest began earlier in the day outside the Department of Education building in Brooklyn. Hundreds of protesters then made their way over the bridge into Manhattan, chanting “Wake up, New York!” and “We the people will not comply.” They also heckled New Yorkers who were sitting outside restaurants eating.

The city's vaccine mandate for school employees took effect Monday. United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew said that as of Monday, 97% of the 78,000 full-time public school employees in New York City had been fully vaccinated.

About 43,000 vaccines had been administered since the mandate was announced in August, according to the New York Times. It’s the first citywide vaccine mandate that doesn’t give workers an option to submit to regular testing instead of getting vaccinated.

As is the case with many protests against vaccine requirements, the opposition to the mandate is coming from a small, but loud, minority. A group of teachers in New York City even made a last-ditch appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in an effort to block the mandate. The Supreme Court declined to hear their case.

Hollywood crews vote to authorize strike, a move that could halt film and TV production. (photo: Getty)

Hollywood crews vote to authorize strike, a move that could halt film and TV production. (photo: Getty)

The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees said 52,706 members or nearly 99% of those who cast ballots voted in favor of a strike authorization. The turnout was unusually high, with 90% of eligible union members participating in the vote, IATSE said.

Union members representing some 60,000 film and TV workers have been casting their votes since Friday to authorize their leaders to call a strike if they can’t reach an agreement with producers on a new three-year contract.

The extraordinary vote comes after months of talks with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers — which represents the major studios and streaming companies — reached an impasse.

“The members have spoken loud and clear,” IATSE President Matthew Loeb said. “This vote is about the quality of life as well as the health and safety of those who work in the film and television industry.”

The AMPTP said it was committed to finding a deal to avoid a production shutdown at a critical time.

“A deal can be made at the bargaining table, but it will require both parties working together in good faith with a willingness to compromise and to explore new solutions to resolve the open issues,” the alliance said in a statement Monday.

The vote doesn’t mean a strike is inevitable, but the near unanimous show of support does give union leaders potentially more leverage in contract negotiations with employers, who might be willing to make concessions for fear of disruptions caused by a walkout.

Loeb informed the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) of the election results Monday morning, saying he “emphasized the need for the studios to adequately address the union’s core issues.”

Nonetheless, the step is highly unusually for IATSE, which historically has avoided confrontations with studios in order to keep its members working. The union has not authorized a nationwide strike in its 128-year history.

Hollywood crews last staged a major strike in 1945, when workers held a series of walkouts outside Warner Bros. and other studios in a protest known as Hollywood’s Bloody Friday.

A walkout would halt production nationwide and deliver a blow to one of Southern California’s most important industries. It would disrupt efforts by the major studios to resume production activity that was delayed by the pandemic, and to feed a growing demand for content from their new streaming platforms.

Over the past few weeks IATSE members have been mobilizing support for the vote with campaigns on social media, circulating petitions and garnering public support from celebrities including Jane Fonda and Mindy Kaling, as well as California legislators.

Crews in Los Angeles have held car-painting campaigns, covering their vehicles with logos and slogans to show their solidarity.

The vote required 75% of the membership of each local to approve the authorization for it to pass. That threshold was met in all 36 union locals, with none reporting less than 96% voting in favor to authorize a strike, IATSE said.

Union leaders sought the authorization after four months of increasingly acrimonious talks between the union and the AMPTP failed to result in a new contract. Negotiations are set to resume Tuesday morning, said one person familiar with the talks who was not authorized to comment.

The union said earlier this month that the producers alliance has not been willing to negotiate terms it wants to improve the working conditions and compensation of its members. Specifically, the union is seeking improved pay, especially for streaming productions; more rest periods to reduce long hours of filming; and higher contributions to the union’s health and pension plans.

Studios have balked at the union’s demands, after having to incur massive costs as a result of new safety requirements and delays due to the coronavirus pandemic. The AMPTP said previously that it had addressed many of the union’s demands, including increasing minimum pay rates for some types of new-media productions and covering a nearly $400-million pension and health plan deficit.

IATSE leaders are negotiating two contracts simultaneously for crews on the West Coast as well as nationally. The two contracts lapsed on July 31 and were extended to Sept. 10.

A woman in Baghdad strolls past campaign posters before the parliamentary election on October 10. (photo: Wissam al-Okaili/Reuters)

A woman in Baghdad strolls past campaign posters before the parliamentary election on October 10. (photo: Wissam al-Okaili/Reuters)

An early vote emerged as one of the central demands from the bloody protests that swept across Baghdad and Iraq’s southern region in 2019.

An early election emerged as one of the central demands from the soon-turned-bloody demonstrations that swept across Baghdad and Iraq’s southern region in 2019. With the newly introduced electoral laws, which would essentially shift the focus of candidates to smaller districts, the hope was to get more response from the previously alienated people, many of whom took part in the protests.

Yet many protesters have continued to argue that a lack of systematic reform away from the largely inept and corrupt system means there is little hope for any real change to address the issues that are to this day still paralysing Iraq – a country that has only recently emerged out of almost two decades of violence and conflict, from the 2003 US-led invasion to the fight against the armed group ISIL (ISIS).

Despite having advocated for electoral reforms and an early election, many of these protesters are now calling for a boycott of the vote, preluding a potential low voter turnout.

Many supporting the boycott have pointed to an electoral environment in which activists have been subject to targeted assassination campaigns, mainly attributed to pro-Iranian militia groups, and the unwillingness of the establishment to give up its power as their motivations for disengagement.

“You either stand up against the government and then later get killed, or vote for the same establishment that you took to the street to try to uproot – that is not a real choice,” said Ahmed al-Tannoury, a university student in the southern city of Basra who joined the mass protest in 2019.

“I’m not going to vote to give any sense of legitimisation to the status quo.”

‘Ideological boycotters’

Ahmed is not the only Iraqi boycotting the elections. Many protesters who once demanded systematic change in the government told Al Jazeera they were not headed to the ballot box.

These are, as categorised by some experts, “ideological boycotters” who are using their voice against the election in pursuit of the goal of de-legitimising the establishment.

“For them, boycott means a way to stay true to the goal of the October protests,” said Taif Alkhudary, an Iraqi politics researcher at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). “Instead of voting, they want to stay out of the system and call for the complete overhaul of the system.”

Electoral boycotts aimed at de-legitimising the government, however, are not new in Iraq. There have been calls to avoid previous elections, which consequently had little effect in changing the endemic corruption among the governing elite.

“Boycotts have almost never been a defining factor to the Iraqi politics. Despite all the post-2003 boycotts, the government continued to govern,” explained Hamzed Hadad, a political analyst focusing on Iraq.

Despite a number of activists’ calling for voters to stay away from the ballot box, others formed their own political parties, some of which are participating in the upcoming election. The Imtidad Movement, for example, headed by Alaa al-Rikabi, is competing for seats in parliament, hoping to change the system from within.

As such, not everyone believes boycotts are not working in the protesters’ favour.

“At this point, you don’t have that many options, so it’s best to go out and vote so the reformists can have a seat on the table in order to reach tangible goals in the Iraqi society,” Rahman Aljebouri, a senior fellow at the American University of Iraq Sulaimani, said.

‘No point in voting’

For many people who decided not to vote, however, the dominant factor is the sense of apathy resulting from years of a shuffling game within the establishment that yielded nominal positive changes.

Having gone through years of conflict and inadequate governance, many Iraqis have lost hope for the betterment of the country through the actions of the governing class.

“Nothing is going to change, no matter what the outcome the election is,” said Mustafa, a 24-year-old resident of Nasiriya, who asked only to be identified by his first name. “I don’t think anyone in the government is going to fix this country, so there is no point in me voting.”

The same power groups that benefitted from the post-2003 muhasasa system, the ethno-sectarian power-sharing arrangement that has been a defining feature of Iraqi politics, will likely come out of the elections triumphant, according to professor Toby Dodge at LSE.

“These new laws still favour those with nationwide organisation with money and network,” said Dodge. “The big old parties that were responsible for creating the system in 2005 will continue to dominate the system.”

The defining factor

Yet a recent statement from Grand Ayatollah al-Sistani, the spiritual leader of Iraqi Shia and the group’s most influential Muslim scholar, could change the picture.

“Although it is not without some shortcomings, it remains the best way to achieve a peaceful future and avoids the risk of falling into chaos and political obstruction,” al-Sistani’s statement reads.

For many politically apathetic Shia constituents, al-Sistani’s endorsement is likely to be the defining factor in deciding whether to vote, even if they do not believe real change could be attained from the ballot box.

“The voter turnout might be slightly higher than that of 2018, when it dipped below 50 percent, especially after al-Sistani’s statement,” said Hamzeh Hadad.

“Even though voter registration has already ended, al-Sistani’s encouragement could mean more people who had already registered but previously decided not to vote would eventually vote.”

Systemic change unlikely

Regardless of the voter turnout, however, many believe systematic change to the status quo is unlikely. Some analysts have said that the international community’s diminished attention on Iraq and the subsequent lack of pressure have given the government a de facto green light not to aim for drastic changes.

“There likely won’t be any direct confrontations between the establishment and the international society because as long as Iraq remains sort of stable as it is now, the world would probably be fine with it,” said Lahib Higel, a senior Iraq analyst at Crisis Group.

In this crisis-ridden country, no political party is surely projected to win a majority vote, which means forming a coalition government would take months.

The influential Sadrist movement, led by the nationalist icon Muqtada Sadr, who emerged in Iraqi politics as a vocal opponent of any foreign influence, and the Iran-aligned Fateh group are likely to lead in parliamentary seats. A subsequent compromise prime minister candidate, such as the current interim Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhami, is, therefore, a likely outcome.

Exactly what that would mean for Iraqis’ lives remains uncertain. The violently crushed Tishreen movement and the following targeted assassination campaign against anti-Iran critics have fundamentally changed Iraqis’ will and tactics to voice their grievances.

The protests might not come back in their original form, but without addressing the systematic issues, the persisting discontent might trigger another round of public anger, analysts have said.

“Anything could happen in Iraq – unless you suddenly get 24-hour electricity and a booming economy, anything could ignite protests,” Hadad said.

Demonstrators lock themselves to Enbridge equipment during a protest against the Line 3 pipeline at a pumping station in Hubbard County, Minnesota, U.S., June 7, 2021. (photo: Nicholas Pfosi/Reuters)

Demonstrators lock themselves to Enbridge equipment during a protest against the Line 3 pipeline at a pumping station in Hubbard County, Minnesota, U.S., June 7, 2021. (photo: Nicholas Pfosi/Reuters)

Enbridge picked up the tab for police wages, training and equipment – and let county police know when it wanted demonstrators arrested

Enbridge has paid for officer training, police surveillance of demonstrators, officer wages, overtime, benefits, meals, hotels and equipment.

Enbridge is replacing the Line 3 pipeline through Minnesota to carry oil from Alberta to the tip of Lake Superior in Wisconsin. The new pipeline carries a heavy oil called bitumen, doubles the capacity of the original to 760,000 barrels a day and carves a new route through pristine wetlands. A report by the climate action group MN350 says the expanded pipeline will emit the equivalent greenhouse gases of 50 coal power plants.

The project was meant to be completed and start functioning on Friday.

Police have arrested more than 900 demonstrators opposing Line 3 and its impact on climate and Indigenous rights, according to the Pipeline Legal Action Network.

It’s common for protesters opposing pipeline construction to face private security hired by companies, as they did during demonstrations against the Dakota Access pipeline. But in Minnesota, a financial agreement with a foreign company has given public police forces an incentive to arrest demonstrators.

The Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, which regulates pipelines, decided rural police should not have to pay for increased strain from Line 3 protests. As a condition of granting Line 3 permits, the commission required Enbridge to set up an escrow account to reimburse police for responding to demonstrations.

Enbridge told the Guardian an independent account manager allocates the funds, and police decide when protesters are breaking the law. But records obtained by the Guardian show the company meets daily with police to discuss intelligence gathering and patrols. And when Enbridge wants protesters removed, it calls police or sends letters.

“Our police are beholden to a foreign company,” Tara Houska, founder of the Indigenous frontline group Giniw Collective, told the Guardian. “They are working hand in hand with big oil. They are actively working for a company. Their duty is owed to the state of Minnesota and to the tribal citizens of Minnesota.”

“It’s a very clear violation of the public’s trust,” she added.

Overtime pay for shooting rubber bullets and Mace

In July, Enbridge began drilling under the Red Lake River near Thief River Falls. A police report said 20 to 100 demonstrators had gathered next to the site for days. The Pennington county sheriff’s office sent a request for help and several police agencies sent officers to protect the fenced-in drill site.

Brandon Thyen, Chisago county sheriff, requested Enbridge reimbursement when his deputies were assigned “to protect the construction workers and equipment from activists and protesters”.

On 29 July, Houska said Line 3 opponents, who identify as water protectors, attempted to stop the drilling, under skies that were thick with wildfire smoke from the west. “We were met with rubber bullets and Mace by a big line of police officers from multiple counties shooting at us at point blank range,” she said.

At about 5pm a group of protesters ran from a nearby camp to the drill site, leaned ladders against the fence and began to climb over, according to a Wright county police report obtained by the Guardian. Police told them they were under arrest but they kept climbing. Then police fired at protesters with “less-lethal munitions” – weapons that are more likely to injure than kill someone. Wright county officers fired pepper spray at protesters and arrested four people.

Police shot Houska with rubber bullets that left bruises and welts on her skin, photos show. It’s not clear which police agency fired the rubber bullets – Wright county said it wasn’t them.

Enbridge reimbursed the Wright county sheriff’s office $26,886.44 for mileage, meals, wages and benefits for officers who worked at the drill site from 28 July to 1 August 2021. The Enbridge fund also reimbursed Anoka, Chisago, Marshall and Clay counties for sending officers to the drill site.

Houska said she overheard officers saying they would get overtime pay for responding on 29 June. “They’re excited about the piggy bank Enbridge has created for them,” she said.

Enbridge picked up tab for surveillance and cheeseburgers

On 12 March 2021, Grand Rapids police followed several vehicles in Aitkin county that they suspected contained Line 3 protesters. Investigator Brian Mattson followed a Jeep into a mall parking lot. The occupants, a “white female and Hispanic or native american male”, recorded him and questioned why he was following them. Sergeant Andrew Morgan wrote in his report that he “maintained surveillance on multiple believed rally participants”, including monitoring a vehicle that contained a “sleeping dragon” device that protesters use to lock themselves to equipment.

Enbridge reimbursed Grand Rapids $4,048.43 for the wages of nine officers who were patrolling Aitkin county that day.

From 4 to 9 June, in response to a mutual aid request, the McLeod county sheriff’s office sent police to Wadena and Aitkin counties for what they called “operation safety net”. They billed their mileage, wages and meals to the Enbridge account, a total of $15,787.57.

The evening of 8 June, the McLeod county officers dined together at the Fireside Inn in Aitkin county. Detective Andrew DeMeyer had buffalo chips and a fiesta salad for $19.15, Deputy Jonathan Robbin had a chicken strip basket, fries and mozzarella sticks for $21.35, Deputy Joshua Fahey had a half chicken with fries for $14.95, and Sgt Billy Kroll enjoyed a bacon cheeseburger, onion rings and two non-alcoholic beers for $22.45. They billed their meals to the Enbridge account.

On 7 June hundreds of protesters occupied an Enbridge pump station in Hubbard county, north of Park Rapids, blockading the site and locking themselves to equipment. The Hubbard county sheriff’s office sent a “code red” to the Beltrami county field force extrication team, which had received training from 2016 to 2020 to remove protesters who used sleeping dragons.

Enbridge reimbursed the Beltrami county sheriff’s office more than $180,000 for the training and equipment its officers would use that day. This included $17,510.99 for equipment, including ballistic helmets, and another $4,095 for shields.

Beltrami officers put on their riot helmets, grabbed their shields and boarded a school bus, according to police reports. At the site, they arrested protesters, including elderly people, and people who locked themselves to bulldozers and excavators.

Enbridge reimbursed Beltrami county sheriff’s office $17,572.22 for police wages and overtime pay for their work that day.

Beltrami also requested reimbursement for pepper spray and batons, but the manager of the escrow account wrote in an email that these were not personal protective equipment and could not be reimbursed.

Simone Senogles, member of the Red Lake Nation and leadership team member for the Indigenous Environmental Network, participated in actions on 7 June to protect the Mississippi River and drinking water.

“You wish they were actually there to protect and serve us, and not to protect and serve a pipeline and a company,” she said of police. “It’s the antithesis of democracy in my mind.”

Oil company ‘calling the shots in Minnesota’

Records obtained by the Guardian show a close working relationship between Enbridge and police.

In December 2020, Cass county’s sheriff’s office began “proactive safety patrols” of communities along the pipeline route. Up to 6 August the Enbridge account reimbursed the sheriff $849,163.40 for these patrols.

Tom Burch, Cass county sheriff, wrote in his request for reimbursement that a Cass county supervisor was assigned to the project and met several times daily with Enbridge public safety liaison staff to discuss safety concerns, intelligence gathering and public safety initiatives for the day.

Burch told the Guardian he would have initiated these patrols even if they couldn’t be reimbursed from Enbridge. “Cass County Sheriff’s Office does not work for Enbridge,” he wrote in an email. “Cass County Sheriff’s Office responds appropriately to the public safety needs for the citizens of Cass County and our communities.”

On 9 January 2021, Kevin Ott, a Grand Rapids police department officer, wrote in a report: “I was contacted by employees of Enbridge who advised me that there were multiple protesters that had occupied their job site to the east of US Hwy #169,” in Aitkin county. He arrested one man who refused to leave the site. Enbridge later reimbursed the Grand Rapids police epartment $1,306.35.

Winona LaDuke, executive director of Honor the Earth, an Indigenous environmental group, told the Guardian she was at the 9 January protest and witnessed an Enbridge employee directing police. “Enbridge has been calling the police shots in northern Minnesota,” she said.

Asked if the company is directing police, an Enbridge spokesperson, Michael Barnes, wrote in an email: “Officers decide when protesters are breaking the law – or putting themselves and others in danger.”

The Guardian requested comment from Beltrami county sheriff’s office, Grand Rapids police department and McLeod county sheriff’s office, but did not receive responses by deadline.

Citing concerns that similar funding models could be replicated in other states, lawyers are close to filing a lawsuit challenging the legality of the escrow fund. “It presents a dystopian future, that’s why we’re challenging it,” said Mara Verheyden-Hilliard, a lawyer with the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund.

In August, Houska and other water protectors met with the UN special rapporteur on human rights to share their concerns about police and the escrow fund. Houska said the financial relationship had resulted in the criminalization of protest and was setting a precedent that “should scare anyone”.

“As we see the climate crisis raging all around us, and the world is on fire, and the water protectors are in jail, at what point do we step in to prevent a precedent like this being the norm?” Houska asked.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611