The Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, who has died at 95, gave his movement a global reach and influence

Before he got sick, Thich Nhat Hanh urged his followers not to put his ashes in a vase, lock him inside and “limit who I am”. Instead, the Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk, poet and peace activist apparently told them: “If I am anywhere, it is in your mindful breathing and in your peaceful steps.”

And after the 95-year-old’s death on Saturday, the breadth of the legacy of his extraordinary life was laid bare as news of his death reverberated around the world, drawing tributes from leading figures from across psychology, religion and social justice.

The Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, said he lived “a truly meaningful life”, adding: “I have no doubt the best way we can pay tribute to him is to continue his work to promote peace in the world.”

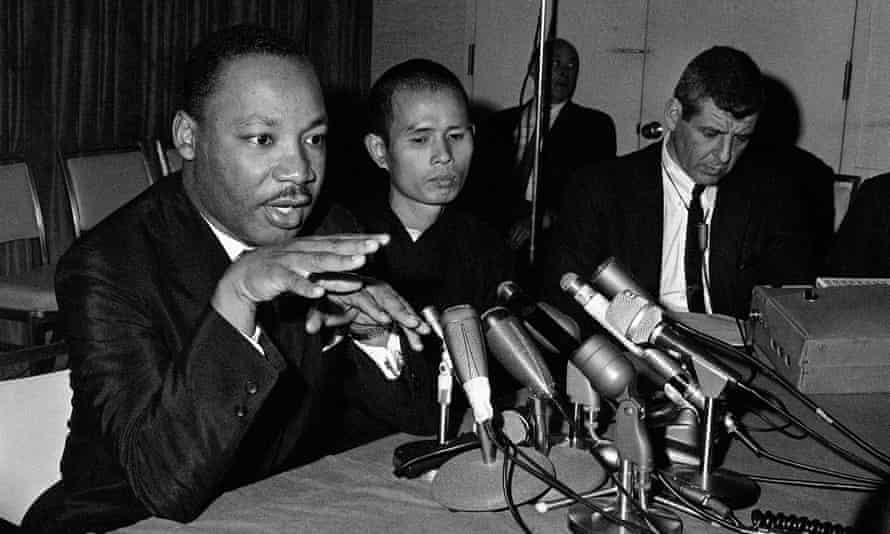

Hanh, known as the “father of mindfulness” and a leading advocate of “engaged Buddhism”, rose to prominence and was exiled from his home country over his opposition to the Vietnam war. After persuading Martin Luther King to speak out against it, the civil rights leader nominated him for the Nobel peace prize in 1967, writing that he did not know of anyone more worthy “than this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam”.

Hanh’s influence even reached the tech world. In 2013 he spoke at Google’s headquarters in Silicon Valley, telling workers: “We have the feeling that we are overwhelmed by information. We don’t need that much information.”

His influence also spanned clinical psychology, with his 1975 book The Miracle of Mindfulness laying the foundations for what would later be used to treat depression and described as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

“He was there at the very start of bringing mindfulness from east to west,” said Mark Williams, emeritus professor of clinical psychology at Oxford University and founding director of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre. Williams first heard about mindfulness from Marsha Linehan, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Washington, who he said kept Hanh’s book in her pocket and referred to it as her “bible”.

He said: “I first met her in the late 80s but this was published in 1975 so she had been using that book to influence her, and it was her work and her advice that influenced us in seeking to incorporate mindfulness into our approach to preventing depression, which then became known as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.”

Today, mindfulness is a ubiquitous term of modern life, but without Hanh’s influence western mindfulness would not, he believes, be what it is today.

Williams said: “What he was able to do was to communicate the essentials of Buddhist wisdom and make it accessible to people all over the world, and build that bridge between the modern world of psychological science and the modern healthcare system and these ancient wisdom practices – and then he continued to do that in his teaching.”

Those who met Hanh said his presence was unlike anything else they had encountered.

Anabel Temple, a member of Heart of London Sangha, part of Hanh’s monastery network, first came across his teachings in his book Being Peace 30 years ago. She travelled with him in China and Vietnam in 2005, when he returned after four decades of exile, and has been to his Plum Village monastery in France many times. Scrolling through her phone, she shows dozens of photos of Hanh – also known as “Thay”, or teacher – travelling.

“He had that sort of way. You go into a room and there were hundreds of people there in a Dharma talk, but he had that ability to feel he was singling you out personally in that room, speaking directly to you,” she said.

The last time Temple saw him was at Plum Village before a stroke, which left him unable to speak, in 2014. Four years later he returned to Vietnam and because of his ill health was permitted by the authorities to spend his final days at the Tu Hieu temple.

It is not yet clear how the government of one-party Vietnam, which is wary of organised religion, will react to his funeral, which began yesterday and will last five days.

“Thay was such humility, such dignity, such presence,” said Temple. “He was funny, angry, sad. He took childlike delight in things and also a profound peace and calmness and an extraordinary humanity.”

Suryagupta, chair of the London Buddhist Centre, first encountered him at a retreat in England about 25 years ago. “He is definitely a giant of a man and I had the good fortune to be on retreat with him in my early days of exploring Buddhism,” she said.

“What was so striking was, whenever he walked into a space, sometimes there would be hundreds of people there, without saying a word literally as soon as he walked in his presence would instil this sort of stillness and quietness in the crowd… and a softness, you felt yourself relax and be alert somehow in his presence.” Suryagupta said his inclusivity was a central feature of his teaching. “He showed that Buddhism was really available for everybody and as a Black woman that was really important to me.”

He died peacefully surrounded by his followers in Tu Hieu temple – the same temple that his spiritual journey started – where they will hold a week-long funeral.

Marianne Williamson, author and former US presidential candidate, said: “He was a great spiritual teacher obviously who brought millions of people around the world into a deeper understanding of the tenets of Buddhism and how to apply them in our daily lives.”

But she is certain that his legacy will live on. “His gift to the planet was so significant I don’t think it will in any way lessen with his death. With some people, and certainly there are those we all know of today, their negativity permeates the consciousness of the planet,” she said. “With Thich Nhat Hanh, his love and compassion permeated the consciousnesses of the planet and now it’s our responsibility to carry it forward from here.”