| |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

They'll keep the public's attention on the attempted coup

One hint came at a Houston-area Trump rally Saturday night. “If I run and if I win,” the former guy said, referring to 2024, “we will treat those people from January 6th fairly.” He then added, “and if it requires pardons, we will give them pardons, because they are being treated so unfairly.” Trump went on to demand "the biggest protest we have ever had" if federal prosecutors in Washington or in New York and Atlanta, where cases against him are moving forward, "do anything wrong or illegal." He then called the federal prosecutors “vicious, horrible people” who are “not after me, they're after you."

Trump’s hint of pardons for those who attacked the Capitol could affect the criminal prosecution of hundreds now facing conspiracy, obstruction and assault charges, which carry sentences that could put them away for years. If they think Trump will pardon them, they might be less willing to negotiate with prosecutors and accept plea deals.

His comments could also be interpreted as a call for violence if various legal cases against him lead to indictments.

But if Trump keeps at it — and of course he will —he’ll help the Democrats in the upcoming midterm elections by reminding the public of the attempted coup he and his Republican co-conspirators tried to pull off between the 2020 election and January 6. That would make the midterm election less of a referendum on Biden than on the Republican Party. (Don’t get me wrong. I think Biden is doing a good job, given the hand he was dealt. But Republicans are doing an even better job battering him — as his sinking poll numbers show.)

Last week, Newt Gingrich, who served as House Speaker from 1995 to 1999, suggested that members of the House select committee investigating the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol should face jail time if the GOP returns to power. "The wolves are gonna find out that they're now sheep, and they're the ones who—in fact, I think—face a real risk of jail for the kind of laws they're breaking," Gingrich said on Fox News.

Gingrich’s remark prompted Representative Liz Cheney, Wyoming Republican and vice-chair of the select committee, to respond: "A former Speaker of the House is threatening jail time for members of Congress who are investigating the violent January 6 attack on our Capitol and our Constitution. This is what it looks like when the rule of law unravels."

Trump and Gingrich are complicating the midterm elections prospects for all Republicans running or seeking reelection nine months from now.

Many Republican leaders believe they don’t need to offer the public any agenda for the midterms because of widespread frustration with Biden and the Democrats. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, recently asked what the Republican party’s agenda would be if it recaptured Congress, quipped “I’ll let you know when we take it back.”

But if Republicans fail to offer an agenda, the Republican party’s midterm message is even more likely to be defined by Trump and Trumpers like Gingrich: the big lie that the 2020 election was stolen along with promises to pardon the January 6 defendants, jail members of the select committee investigating the attack on the Capitol, and other bonkers claims and promises.

This would spell trouble for the GOP because most Americans don’t believe the big lie and remain appalled by the attack on the Capitol.

House minority leader Kevin McCarthy (who phoned Trump during the attack on the Capitol but refuses to cooperate with the House’s January 6 committee investigation) will have a major role in defining the Republican message for the midterms. And whom has McCarthy been consulting with? None other than Newt Gingrich. The two have been friends for years and McCarthy's current chief of staff in his leadership office, Dan Meyer, served in the same role for Gingrich when he was the speaker.

McCarthy knows Gingrich is a master huckster. After all, in 1994 Gingrich delivered a House majority for the Republicans for the first time in 40 years by promising a “contract with America” that amounted to little more than trickle-down economics and state’s rights.

But like most hucksters, Gingrich suffered a spectacular fall. In 1997 House members overwhelmingly voted to reprimand him for flouting federal tax laws and misleading congressional investigators about it — making him the first speaker panned for unethical behavior. The disgraced leader, who admitted to the ethical lapse as part of a deal to quash inquiries into other suspect activities, also had to pay a historic $300,000 penalty. Then, following a surprise loss of Republican House seats in the 1998 midterm election, Gingrich stepped down as speaker. He resigned from Congress in January 1999 and hasn't held elected office since.

I’ve talked with Gingrich several times since then. I always come away with the impression of a military general in an age where bombast and explosive ideas are more potent than bombs. Since he lost the House, Gingrich has spent most of his time and energy trying to persuade other Republicans that he alone possesses the strategy and the ideas entitling him to be the new general of the Republican right.

Gingrich has no scruples, which is why he has allied himself with Trump and Trump’s big lie — appearing regularly on Fox News to say the 2020 election was rigged and mouth off other Trumpish absurdities (such as last week’s claim that members of the House select committee should be jailed).

Gingrich likes to think of himself as a revolutionary force, but he behaves more like a naughty boy. When he was Speaker, his House office was adorned with figurines of dinosaurs, as you might find in the bedrooms of little boys who dream of becoming huge and powerful. Gingrich can be mean, but his meanness is that of a nasty kid rather than a tyrant. And like all nasty kids, inside is an insecure little fellow who desperately wants attention.

Still, as of now, the best hope for Democrats in the midterms lies with Trump, Gingrich, and others who loudly and repeatedly remind the public how utterly contemptible the Republican Party has become.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The idea that such a catastrophe is unavoidable in America is inflammatory and corrosive.

What made him so sure of our fate was that the British army’s parachute regiment had opened fire on the streets of Derry, after an illegal but essentially peaceful civil-rights march. Troops killed 13 unarmed people, mortally wounded another, and shot more than a dozen others. Intercommunal violence had been gradually escalating, but this seemed to be a tipping point. There were just two sides now, and we all would have to pick one. It was them or us.

The conditions for civil war did indeed seem to exist at that moment. Northern Irish society had become viciously polarized between one tribe that felt itself to have suffered oppression and another one fearful that the loss of its power and privilege would lead to annihilation by its ancient enemies. Both sides had long-established traditions of paramilitary violence. The state—in this case both the local Protestant-dominated administration in Belfast and the British government in London—was not only unable to stop the meltdown into anarchy; it was, as the massacre in Derry proved, joining in.

Yet my father’s fears were not fulfilled. There was a horrible, 30-year conflict that brought death to thousands and varying degrees of misery to millions. There was terrible cruelty and abysmal atrocity. There were decades of despair in which it seemed impossible that a polity that had imploded could ever be rebuilt. But the conflict never did rise to the level of civil war.

However, the belief that there was going to be a civil war in Ireland made everything worse. Once that idea takes hold, it has a force of its own. The demagogues warn that the other side is mobilizing. They are coming for us. Not only do we have to defend ourselves, but we have to deny them the advantage of making the first move. The logic of the preemptive strike sets in: Do it to them before they do it to you. The other side, of course, is thinking the same thing. That year, 1972, was one of the most murderous in Northern Ireland precisely because this doomsday mentality was shared by ordinary, rational people like my father. Premonitions of civil war served not as portents to be heeded, but as a warrant for carnage.

Could the same thing happen in the United States? Much of American culture is already primed for the final battle. There is a very deep strain of apocalyptic fantasy in fundamentalist Christianity. Armageddon may be horrible, but it is not to be feared, because it will be the harbinger of eternal bliss for the elect and eternal damnation for their foes. On what used to be referred to as the far right, but perhaps should now simply be called the armed wing of the Republican Party, the imminence of civil war is a given.

Indeed, the conflict can be imagined not as America’s future, but as its present. In an interview with The Atlantic published in November 2020, two months before the invasion of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, the founder of the Oath Keepers, Stewart Rhodes, declared: “Let’s not fuck around.” He added, “We’ve descended into civil war.” The following month, the FBI, warning of possible attacks on state capitols, said that members of the so-called boogaloo movement “believe an impending insurgency against the government is forthcoming and some believe they should accelerate the timeline with armed, antigovernment actions leading to a civil war.”

After January 6, mainstream Republicans picked up the theme. Much of the American right is spoiling for a fight, in the most literal sense. Which is one good reason to be very cautious about echoing, as the Canadian journalist and novelist Stephen Marche does in The Next Civil War: Dispatches From the American Future, the claim that America “is already in a state of civil strife, on the threshold of civil war.” These prophecies have a way of being self-fulfilling.

Admittedly, if there were to be another American civil war, and if future historians were to look back on its origins, they would find them quite easily in recent events. It is news to no one that the United States is deeply polarized, that its divisions are not just political but social and cultural, that even its response to a global pandemic became a tribal combat zone, that its system of federal governance gives a minority the power to frustrate and repress the majority, that much of its media discourse is toxic, that one half of a two-party system has entered a postdemocratic phase, and that, uniquely among developed states, it tolerates the existence of several hundred private armies equipped with battle-grade weaponry.

It is also true that the American system of government is extraordinarily difficult to change by peaceful means. Most successful democracies have mechanisms that allow them to respond to new conditions and challenges by amending their constitutions and reforming their institutions. But the U.S. Constitution has inertia built into it. What realistic prospect is there of changing the composition of the Senate, even as it becomes more and more unrepresentative of the population? It is not hard to imagine those future historians defining American democracy as a political life form that could not adapt to its environment and therefore did not survive.

It is one thing, however, to acknowledge the real possibility that the U.S. could break apart and could do so violently. It is quite another to frame that possibility as an inevitability. The descent into civil war is always hellish. America has still not recovered from the fratricidal slaughter of the 1860s. Even so, the American Civil War was relatively contained compared with what happened to Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution, to Bosnia after the breakup of Yugoslavia, or to Congo from 1998 to 2003. The idea that such a catastrophe is imminent and unavoidable must be handled with extreme care. It is both flammable and corrosive.

Marche clearly does not intend to be either of these things, and in speculating about various possible catalysts for chaos in the U.S., he writes more in sorrow than in anger, more as a lament than a provocation. Marche’s thought experiment begins, however, with two conceptual problems that he never manages to resolve.

The first of these difficulties is that, as the German poet and essayist Hans Magnus Enzensberger put it in his 1994 book Civil Wars, “there is no useful Theory of Civil War.” It isn’t a staple in military school—Carl von Clausewitz’s bible, On War, has nothing to say about it. There are plenty of descriptions of this or that episode of internal conflict. Thucydides gave us the first one, History of the Peloponnesian War, 2,500 years ago. But as Enzensberger writes, “It’s not just that the mad reality eludes formal legal definition. Even the strategies of the military high commands fail in the face of the new world order which trades under the name of civil war. The unprecedented comes into sudden and explosive contact with the atavistic.”

This mad reality is impossible to map onto a country as vast, diverse, and demographically fluid as the United States already is, still less onto how it might be at some unspecified time in the future. Marche has a broad notion that his putative civil war will take the form of one or more armed insurrections against the federal government, which will be put down with extreme violence by the official military. This repression will in turn fuel a cycle of insurgency and counterinsurgency. Under the strain, the U.S. will fracture into several independent nations. All of this is quite imaginable as far as it goes. But such a scenario does not actually go very far in defining this sort of turmoil as a civil war. Indeed, Marche himself envisages that, while “one way or another, the United States is coming to an end,” this dissolution could in theory be a “civilized separation.”

But this possibility does not sit well with the doomsaying that is his book’s primary purpose. Nor is it internally coherent. Marche seems to think that a secession by Texas might be consensual because Texas is a “single-party state.” This would be news to the 46.5 percent of its voters who supported Joe Biden in the 2020 election. How would they feel about losing their American citizenship and being told that they now owe their allegiance to the Republic of Texas? If we really do want to imagine a future of violent conflict, would it not be just as much within seceding states as among supposedly discrete geographic and ideological blocs?

The secession of California as well as Texas is just one of five “dispatches” that Marche writes from his imagined future. He begins with an eminently plausible and well-told tale of a local sheriff who takes a stand against the government’s closure for repair of a bridge used by most of his constituents. The right-wing media make him a hero figure, and he exploits the publicity brilliantly. The bridge becomes a magnet for militias, white supremacists, and anti-government cultists. The standoff is brought to an end by a military assault, resulting in mass casualties and creating, on the right, both a casus belli and martyrs for the cause. Marche’s other dispatches describe the assassination of a U.S. president by a radicalized young loner; a combination of environmental disasters, with drought causing food shortages and a massive hurricane destroying much of New York; and the outbreak of insurrectionary violence and the equally violent responses to it.

All of these scenarios are well researched and eloquently presented. But how they relate to one another, or whether the conflicts they involve can really be regarded as a civil war, is never clear. Civil wars need mass participation, and how that could be mobilized across a subcontinent is not at all obvious. Marche seems to endorse the claim of the military historian Peter Mansoor that the pandemonium “would very much be a free-for-all, neighbor on neighbor, based on beliefs and skin colors and religion.” His scenarios, either separately or cumulatively, do not show how or why the U.S. arrives at this Hobbesian state.

Marche’s other conceptual problem is that, in order to dramatize all of this as a sudden and terrible collapse, he creates a ridiculously high baseline of American democratic normalcy. “A decade ago,” he writes, “American stability and global supremacy were a given … The United States was synonymous with the glory of democracy.” In this steady state, “a president was once the unquestioned representative of the American people’s will.” The U.S. Congress was “the greatest deliberative body in the world.”

These claims are risible. After the lies that underpinned the invasion of Iraq and the abject failures of Congress to impose any real accountability for the conduct of the War on Terror, the beacon of American democracy was pretty dim. Has the sacred legitimacy of any U.S. president been unquestioned, ever? Did we imagine the visceral hatred of Bill Clinton among Republicans or Donald Trump’s insistence that Barack Obama was not even a proper American, let alone the embodiment of the people’s will?

This failure of historical perspective means that Marche can ignore the evidence that political violence, much of it driven by racism, is not a new threat. Even if we leave aside the actual Civil War, it has long been endemic in the U.S. Were the wars of extermination against American Indians not civil wars too? What about the brutal obliteration of the Black community in Greenwood, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921—should that not be seen as an episode in a long, undeclared war on Black Americans by white supremacists? The devastating riots in cities across America that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, and in Los Angeles after the beating of Rodney King in 1992, sure looked like the kind of intercommunal violence that Marche conjures as a specter from the future. Arguably, the real problem for the U.S. is not that it can be torn apart by political violence, but that it has learned to live with it.

This is happening again—even the attempted coup of January 6 is already, for much of the political culture, normalized. Marche is so intent on the coming catastrophe that he seems unable to focus on what is in front of his nose. He writes, for example, that the assault on the Capitol cannot be regarded as an insurrection, because “the rioters were only loosely organized and possessed little political support and no military support.” The third of these claims is broadly true (though military veterans featured heavily among the attackers). The first is at best dubious. The second is bizarre: The attack was incited by the man who was still the sitting president of the United States and had, both at the time and subsequently, widespread support within the Republican Party.

In this context, feverish talk of civil war has the paradoxical effect of making the current reality seem, by way of contrast, not so bad. The comforting fiction that the U.S. used to be a glorious and settled democracy prevents any reckoning with the fact that its current crisis is not a terrible departure from the past but rather a product of the unresolved contradictions of its history. The dark fantasy of Armageddon distracts from the more prosaic and obvious necessity to uphold the law and establish political and legal accountability for those who encourage others to defy it. Scary stories about the future are redundant when the task of dealing with the present is so urgent.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

A year after the attack on the Capitol, America is suspended between democracy and autocracy.

On January 6, 2021, when white supremacists, militia members, and MAGA faithful took inspiration from the President and stormed the Capitol in order to overturn the results of the 2020 Presidential election, leaving legislators and the Vice-President essentially held hostage, we ceased to be a full democracy. Instead, we now inhabit a liminal status that scholars call “anocracy.” That is, for the first time in two hundred years, we are suspended between democracy and autocracy. And that sense of uncertainty radically heightens the likelihood of episodic bloodletting in America, and even the risk of civil war.

This is the compelling argument of “How Civil Wars Start,” a new book by Barbara F. Walter, a political scientist at the University of California San Diego. Walter served on an advisory committee to the C.I.A. called the Political Instability Task Force, which studies the roots of political violence in nations from Sri Lanka to the former Yugoslavia. Citing data compiled by the Center for Systemic Peace, which the task force uses to analyze political dynamics in foreign countries, Walter explains that the “honor” of being the oldest continuous democracy is now held by Switzerland, followed by New Zealand. In the U.S., encroaching instability and illiberal currents present a sad picture. As Walter writes, “We are no longer a peer to nations like Canada, Costa Rica, and Japan.”

In her book and in a conversation for this week’s New Yorker Radio Hour, Walter made it clear that she wanted to avoid “an exercise in fear-mongering”; she is wary of coming off as sensationalist. In fact, she takes pains to avoid overheated speculation and relays her warning about the potential for civil war in clinical terms. Yet, like those who spoke up clearly about the dangers of global warming decades ago, Walter delivers a grave message that we ignore at our peril. So much remains in flux. She is careful to say that a twenty-first-century American civil war would bear no resemblance to the consuming and symmetrical conflict that was played out on the battlefields of the eighteen-sixties. Instead she foresees, if the worst comes about, an era of scattered yet persistent acts of violence: bombings, political assassinations, destabilizing acts of asymmetric warfare carried out by extremist groups that have coalesced via social media. These are relatively small, loosely aligned collections of self-aggrandizing warriors who sometimes call themselves “accelerationists.” They have convinced themselves that the only way to hasten the toppling of an irredeemable, non-white, socialist republic is through violence and other extra-political means.

Walter makes the case that, as long as the country fails to fortify its democratic institutions, it will endure threats such as the one that opens her book: the attempt, in 2020, by a militia group in Michigan known as the Wolverine Watchmen to kidnap Governor Gretchen Whitmer. The Watchmen despised Whitmer for having instituted anti-COVID measures in the state—restrictions that they saw not as attempts to protect the public health but as intolerable violations of their liberty. Trump’s publicly stated disdain for Whitmer could not have discouraged these maniacs. The F.B.I., fortunately, foiled the Wolverines, but, inevitably, if there are enough such plots—enough shots fired—some will find their target.

America has always suffered acts of political violence—the terrorism of the Klan; the 1921 massacre of the Black community in Tulsa; the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Democracy has never been a settled, fully stable condition for all Americans, and yet the Trump era is distinguished by the consuming resentment of many right-wing, rural whites who fear being “replaced” by immigrants and people of color, as well as a Republican Party leadership that bows to its most autocratic demagogue and no longer seems willing to defend democratic values and institutions. Like other scholars, Walter points out that there have been early signs of the current insurgency, including the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, in 1995, which killed a hundred and sixty-eight people. But it was the election of Barack Obama that most vividly underlined the rise of a multiracial democracy and was taken as a threat by many white Americans who feared losing their majority status. Walter writes that there were roughly forty-three militia groups operating in the U.S. when Obama was elected, in 2008; three years later there were more than three hundred.

Walter has studied the preconditions of civil strife all over the world. And she says that, if we strip away our self-satisfaction and July 4th mythologies and review a realistic checklist, “assessing each of the conditions that make civil war likely,” we have to conclude that the United States “has entered very dangerous territory.” She is hardly alone in that conclusion. The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in Stockholm recently listed the U.S. as a “backsliding” democracy.

The backsliding was never more depressingly evident than in the weeks after January 6th, when Mitch McConnell, after initially criticizing Donald Trump’s role in the insurrection, said that he would support him if he were the Party’s nominee in 2024. Having stared into the abyss, he pursued the darkness.

Not so long ago, Walter might have been considered an alarmist. In 2018, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt published their Trump-era study, “How Democracies Die,” one of many books that sought to awaken American readers to the reality that the rule of law was under assault just as it was in much of the world. But, as Levitsky told me, “Even we couldn’t have imagined January 6th.” Levitsky said that until he read Walter and other well-respected scholars on the subject, he would have thought that warnings of civil war were overwrought.

Unlike Russia or Turkey, the United States is blessed with a deep experience of democratic rule, no matter how flawed. The courts, the Democratic Party, local election officials in both parties, the military, the media—no matter how deeply flawed—proved in 2020 that it was possible to resist the darkest ambitions of an autocratic President. The guardrails of democracy and stability are hardly unassailable, but they are stronger than anything that Vladimir Putin or Recep Tayyip Erdoǧan has to contend with. In fact, in his attempt to be reëlected, Trump did draw the largest Republican vote ever—and he still lost by seven million votes. That, too, stands in the way of fatalism.

“We’re not headed to fascism or Putinism,” Levitsky told me, “but I do think we could be headed to recurring constitutional crises, periods of competitive authoritarian and minority rule, and episodes of pretty significant violence that could include bombings, assassinations, and rallies where people are killed. In 2020, we saw people being killed on the streets for political reasons. This isn’t apocalypse, but it is a horrendous place to be.”

The battle to preserve American democracy is not symmetrical. One party, the G.O.P., now poses itself as anti-majoritarian and anti-democratic. And it has become a Party less focussed on traditional policy values and more on tribal affiliation and resentments. A few figures, including Liz Cheney and Mitt Romney, know that this is a recipe for an authoritarian Party, but there is no sign of what is required to reverse the most worrying trends: a broad-based effort among Republican leaders to stand up and join Democrats and Independents in a coalition based on a reassertion of democratic values.

As the anniversary of the insurrection is observed, the greater drama is not obscure. We are a country capable of electing Barack Obama and, eight years later, Donald Trump. We are capable of January 5th, when the state of Georgia elected two senators, an African American and a Jew, and January 6th, when thousands stormed the Capitol in the name of a preposterous conspiracy theory.

“There are two very different movements at once in the same country,” Levitsky said. “This country is moving towards multiracial democracy for the first time. In the twenty-first century we have a multiracial democratic majority supportive of a diverse society and of having the laws to insure equal rights. That multiracial democratic majority is out there, and it can win popular elections.” And then there is the Republican minority, which too often looks the other way as dangerous extremists act on its behalf. Let’s hope the warnings about a new kind of civil war come to nothing, and we can look back on books like Walter’s as alarmist. But, as we have learned with the imperilled state of our climate, wishing does not make it so.

Insurrectionists loyal to Donald Trump rioted at the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. (photo: José Luis Magaña/AP)

Insurrectionists loyal to Donald Trump rioted at the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. (photo: José Luis Magaña/AP)

Messages between Mark Meadows and others suggest the Trump White House coordinated efforts to stop Joe Biden’s certification

The committee’s new focus on the potential for a conspiracy marks an aggressive escalation in its inquiry as it confronts evidence that suggests the former president potentially engaged in criminal conduct egregious enough to warrant a referral to the justice department.

House investigators are interested in whether Trump oversaw a criminal conspiracy after communications turned over by Trump’s former chief of staff Mark Meadows and others suggested the White House coordinated efforts to stop Biden’s certification, the sources said.

The select committee has several thousand messages, among which include some that suggest the Trump White House briefed a number of House Republicans on its plan for then-vice president Mike Pence to abuse his ceremonial role and not certify Biden’s win, the sources said.

The fact that the select committee has messages suggesting the Trump White House directed Republican members of Congress to execute a scheme to stop Biden’s certification is significant as it could give rise to the panel considering referrals for potential crimes, the sources said.

Members and counsel on the select committee are examining in the first instance whether in seeking to stop the certification, Trump and his aides violated the federal law that prohibits obstruction of a congressional proceeding – the joint session on 6 January – the sources said.

The select committee believes, the sources said, that Trump may be culpable for an obstruction charge given he failed for hours to intervene to stop the violence at the Capitol perpetrated by his supporters in his name.

But the select committee is also looking at whether Trump oversaw an unlawful conspiracy that involved coordination between the “political elements” of the White House plan communicated to Republican lawmakers and extremist groups that stormed the Capitol, the sources said.

That would probably be the most serious charge for which the select committee might consider a referral, as it considers a range of other criminal conduct that has emerged in recent weeks from obstruction to potential wire fraud by the GOP.

The vice-chair of the select committee, the Republican congresswoman Liz Cheney, referenced the obstruction charge when she read from the criminal code before members voted unanimously last November to recommend Meadows in contempt of Congress for refusing to testify.

The Guardian previously reported that Trump personally directed lawyers and political operatives working from the Willard hotel in Washington DC to find ways to stop Biden’s certification from happening at all on 6 January just hours before the Capitol attack.

But House investigators are yet to find evidence tying Trump personally to the Capitol attack, the sources said, and may ultimately only recommend referrals for the straight obstruction charge, which has already been brought against around 275 rioters, rather than for conspiracy.

The justice department could yet charge Trump and aides separate to the select committee investigation, but one of sources said the panel – as of mid-December – had no idea whether the agency is actively examining potential criminality by the former president.

A spokesperson for the select committee declined to comment on details about the investigation. A spokesperson for the justice department declined to comment whether the agency had opened a criminal inquiry for Trump or his closest allies over 6 January.

Still, the select committee appears to be moving towards making at least some referrals – or alternatively recommendations in its final report – that an aggressive prosecutor at the justice department could use to pursue a criminal inquiry, the sources said.

The select committee is examining the evidence principally to identify legislative reforms to prevent a repeat of Trump’s plan to subvert the election, but members say if they find Trump violated federal law, they have an obligation to refer that to the justice department.

Sending a criminal referral to the justice department – essentially a recommendation for prosecution – carries no formal legal weight since Congress lacks the authority to force it to open a case, and House investigators have no authority to charge witnesses with a crime.

But a credible criminal referral from the select committee could have a substantial political effect given the importance of the 6 January inquiry, and place pressure on the attorney general, Merrick Garland, to initiate an investigation, or explain why he might not do so.

Internal discussions about criminal referrals intensified after communications turned over by Meadows revealed alarming lines of communication between the Trump White House and Republican lawmakers over 6 January, the sources said.

In one exchange released by the select committee, one Republican lawmaker texted Meadows an apology for not pulling off what might have amounted to a coup, saying 6 January was a “terrible day” not because of the attack, but because they were unable to stop Biden’s certification.

The select committee believes messages such as that text – as well as remarks from a Republican on the House floor as the Capitol came under attack – might represent one part of a conspiracy by the White House to obstruct the joint session, the sources said.

In referencing objections to six states, the text also appears to comport with a memo authored by the Trump lawyer John Eastman that suggested lodging objections to six states – raising the specter the White House distributed the plan more widely than previously known.

Bennie Thompson, the chairman of the select committee, added on ABC last week that the investigation had found evidence to suggest the events of 6 January “appeared to be a coordinated effort on the part of a number of people to undermine the election”.

Counsel for the select committee indicated in their contempt of Congress report for Meadows that they intended to ask Trump’s former chief of staff about those communications he turned over voluntarily, before he broke off a cooperation deal and refused to testify.

Thompson has also suggested to reporters that he believes Meadows stopped cooperating with the inquiry in part because of pressure from Trump, but the select committee has not opened a separate witness intimidation investigation into the former president, one of the sources said.

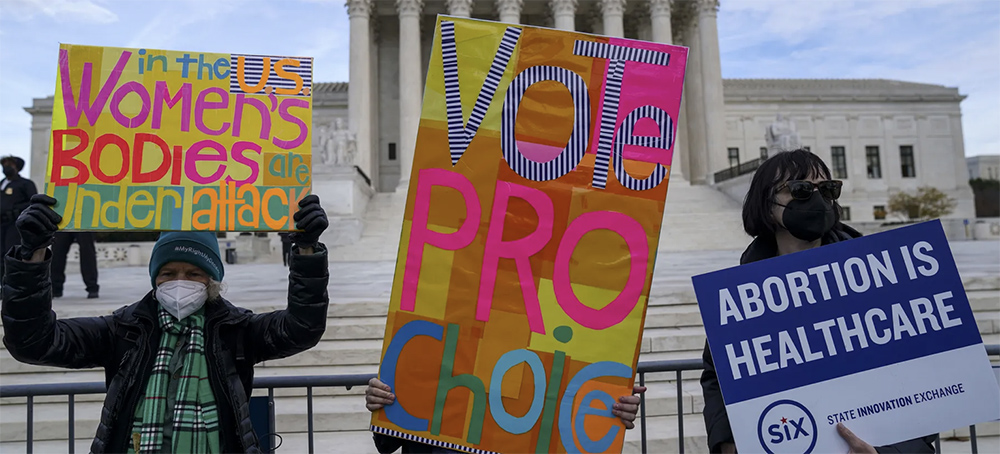

Protesters hold signs in front of the US Supreme Court during the 'Hold The Line For Abortion Justice' Women's March on December 1, 2021. (photo: Leigh Vogel/Getty Images for Women's March Inc)

Protesters hold signs in front of the US Supreme Court during the 'Hold The Line For Abortion Justice' Women's March on December 1, 2021. (photo: Leigh Vogel/Getty Images for Women's March Inc)

Brnovich v. Isaacson could trigger a flood of decisions reinstating long-dead anti-abortion laws.

That leaves the right to an abortion in limbo. Technically, decisions like Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which weakened Roe somewhat but retained core protections for abortion, remain good law. And many state anti-abortion laws are currently blocked by court orders that rely on Roe and Casey.

But those court orders are unlikely to survive the year and could very well all be lifted this summer, in the likely event that Dobbs overrules or drastically curtails Roe and Casey.

Arizona’s Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich, however, apparently doesn’t have the patience to let this process play out. In early December, Brnovich asked the Court to immediately reinstate an enjoined state law restricting certain abortions. That law would prohibit abortion providers from performing an abortion if the provider knows that “the abortion is sought solely because of a genetic abnormality of the child” — although it does include an exception if the fetus has a condition that will prove fatal within three months of birth.

The case is Brnovich v. Isaacson, and it remains pending before the justices.

Though one conservative appeals court did uphold a similar Ohio law, most courts to consider laws banning abortions if the state disagrees with the reason for the abortion have been blocked by lower courts, and there is a very strong argument that these laws violate Casey. A Supreme Court decision reinstating the Arizona law, in other words, would be another loud signal from the justices that Casey is in its final days.

Just as significantly, if Brnovich succeeds in his bid to reinstate Arizona’s law, he’s likely to open the floodgates to other Republican officials who wish to reinstate other anti-abortion laws.

A decision reinstating the Arizona law would be an announcement that the Supreme Court is open to similar requests to lift existing court orders protecting the right to an abortion. And it would send a clear signal to anti-abortion judges in the lower courts that they are free to start lifting such court orders as well.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, state lawmakers enacted 108 abortion restrictions in 2021 alone. Eight states still retain abortion bans from before 1973, when Roe was handed down, and several others have laws on the books that effectively ban all or most abortions. So, if the courts start allowing these sorts of laws to take effect, the impact on abortion rights could be swift and profound.

Given that a decision in Dobbs is at most months away, the long-term impact of an anti-abortion ruling in Isaacson is likely to be minimal. Once Roe is overruled or gutted completely, the process of unwinding court orders blocking anti-abortion laws will happen anyway. But, at the very least, the Isaacson case could have a profound impact on anyone seeking an abortion in the first half of 2022.

Arizona’s law is unconstitutional under Casey

There are several very strong arguments that the Arizona law is unconstitutional under existing precedents.

First of all, Casey held that “a State may not prohibit any woman from making the ultimate decision to terminate her pregnancy before viability,” where “viability” refers to the moment when a fetus is capable of living outside the womb.

As the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit noted in an opinion striking down an Indiana law that is similar to Arizona’s, “Casey’s holding that a woman has the right to terminate her pregnancy prior to viability is categorical.” Casey says that the state may not prohibit “any woman” from terminating a pregnancy prior to viability. That includes people who wish to terminate their pregnancy for reasons that the state disapproves of.

For what it’s worth, the Sixth Circuit, which is the only circuit to uphold an Arizona-style law, rejected the Seventh Circuit’s reasoning on the theory that these kinds of laws do not actually prohibit anyone from getting an abortion. Recall that Arizona’s law only prohibits providers from performing an abortion if they know that their patient is doing so for an impermissible reason. The Sixth Circuit claimed that this requirement that a doctor know their patient’s motive places such laws outside of Casey’s categorical rule because a patient could still obtain an abortion from a doctor who is ignorant of the patient’s motives.

But even if a judge accepts such sophistry, Arizona’s law runs into a second problem. Casey doesn’t just prohibit pre-viability abortion bans, it also prohibits any abortion law that “has the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” It’s hard to imagine a legitimate purpose — that is, a purpose other than placing obstacles in front of people seeking abortions — to a law that permits abortions, but only if the doctor doesn’t know too much about their patient.

The district court that struck down Arizona’s law also gave a third reason why it is unconstitutional. As the Supreme Court held in United States v. Davis (2019), excessively vague laws may be struck down if they fail to “give ordinary people fair warning about what the law demands of them.” And the district court pointed to several provisions of the Arizona law which, it concluded, do not clear this bar. For example, the law “does not offer workable guidance about which fetal conditions” qualify as a “genetic abnormality.”

A decision reinstating the Arizona law would embolden opponents of abortion

In any event, the fact that the Sixth Circuit disagrees with several of its fellow circuits about whether Arizona-style laws are constitutional is a good reason for the Supreme Court to hear the Isaacson case eventually. The justices often hear cases where two or more federal appeals courts have reached different answers to the same legal question, as the whole purpose of having a single Supreme Court at the apex of the judiciary is to ensure that federal law is uniform throughout the country.

But Isaacson arrives at the Supreme Court on the Court’s “shadow docket,” a mix of emergency motions and other matters that are typically decided on a short timeframe and without full briefing or oral argument. Arizona’s attorney general, in other words, hopes to bypass the ordinary process for seeking review of a lower court decision — a process that typically takes months or longer — and obtain a Supreme Court decision reinstating Arizona’s law as soon as possible.

If Brnovich can step outside the Court’s normal procedures to obtain such an order, other Republican officials will think they can do so as well. And many lower court judges will likely view such an order as a sign that they should start reinstating anti-abortion laws that were previously struck down.

Thus, in practice, the Isaacson decision could wind up accelerating the demise of Roe, triggering a wave of decisions gutting abortion rights months before Dobbs is handed down.

Indeed, there is a precedent, of sorts, for the Supreme Court gradually rolling out a major change in its understanding of the Constitution rather than implementing that change abruptly with one definitive decision.

In the lead-up to Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), the Court’s landmark marriage equality decision, multiple lower courts handed down decisions holding that states could not deny marriage rights to same-sex couples. Rather than block these decisions while the Court pondered whether to make marriage equality the law in all 50 states, the Court allowed these lower court decisions to take effect. The upshot was that, by the time Obergefell was handed down, marriage equality had already come to much of the country due to these unblocked lower court orders.

There are obvious differences between Obergefell and Dobbs — the former was an expansion of individual rights, while Dobbs is likely to end in a significant contraction of such rights — but the lead-up to Obergefell shows that the Court will sometimes implement a new constitutional rule on a piecemeal basis before implementing it nationwide. That process may already be underway as the Court drafts its Dobbs decision.

A supporter of President Donald Trump prays outside the Capitol January 06, 2021. (photo: Win McNamee/Getty Images)

A supporter of President Donald Trump prays outside the Capitol January 06, 2021. (photo: Win McNamee/Getty Images)

The violence of January 6 has united white nationalism with Christian nationalism

“Of course we are not!” true patriots are meant to answer in their heart of hearts, feeling all the feels for a country that withstood the insurrection of January 6, 2021, only to presumably bounce back better.

But the premise behind the question was flawed. To put a fine point on it: Americans have always accepted political violence as a norm. From the mass killing of Native Americans to the subjugation of generations of enslaved people, the land we stand on and the wealth we enjoy were built by violent means.

And yet, it’s fair to say that the violence that occurred in our nation’s capital one year ago today is distinct from that which has come before. In the past, American political violence was about one group of people — namely, white, Protestant ones — asserting their assumed superiority over all others. Today, it’s about that same group of people acting out in the fear that their “superiority” is slipping away — or being intentionally stolen. According to findings published four days ago by the Chicago Project on Security and Threats, nine percent of Americans — a full 21 million people — agree both that Biden’s presidency is illegitimate and that the use of force is justified to restore Trump. The single most reliable predictor that someone would find themselves among that 21 million, per CPOST’s report, is belief in the so-called Great Replacement, the idea that “The Democratic Party is trying to replace the current electorate…with new people, more obedient voters from the Third World.”

It’s this idea, in fact, that is drawing previously disparate factions on the Republican Party together in common cause. Twenty-seven years ago, the political violence of the Oklahoma City bombing splintered the party. Today — and despite a bit of grandstanding in its aftermath — the violence of January 6 has united white nationalism with Christian nationalism, creating a more mainstream alliance embraced by entirely mainstream politicians.

And while white nationalism may have always had violence at its core, the same cannot necessarily be said of Christian nationalism — until now. If constructing a gallows to hang Mike Pence could be consistent with hoisting a sign that reads “Jesus Saves,” it’s because a critical mass of conservative white evangelicals have come to conflate ideas of manifest destiny and American essentialism with the idea of America as a nation consecrated by God. In this framing, the Great Replacement subverts the will of God. And the will of God must be defended at any and all costs.

“I think it’s set off a kind of apocalyptic approach to politics,” says Robert P. Jones, head of the Public Religion Research Institute and author of White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity. “It’s a kind of desperate politics that has, in a sense, declared martial law. What happens when you’re in an emergency? You suspend the normal rules.” You may, for instance, stop turning the other cheek as Jesus instructed and instead decide to march to the Capitol, take some selfies, and then use a flagpole as a battering ram. To wit, in 2021, Jones’ research found that white Christians who believe that “God has granted America a special role in human history” were three times more likely (29 percent versus 10 percent) to also believe that violence may be necessary to save the country.

In part, this is because while the conspiracy theory that defines the Great Replacement — the idea that Democrats are plotting an electorate overhaul — is not true, it is certainly true that white Christians are being replaced greatly. “As recently as 2008, when Barack Obama first ran for president, the country was 54 percent white and Christian; that number today is 44 percent,” says Jones. “Among white evangelicals, the median age today is 57. They’re a shrinking and graying group. They are no longer the unquestioned political, cultural majority voice.”

Psychology has long taught us that people will do more to get back what they’ve lost than to gain what they don’t yet have. As White Christians lose their dominance in American life, we should all be afraid of what extremists will do to get it back.

A woman carries a child as she begs from commuters in a car in Kabul on December 26, 2021. (photo: Mohd Rasfan/AFP/Getty Images)

A woman carries a child as she begs from commuters in a car in Kabul on December 26, 2021. (photo: Mohd Rasfan/AFP/Getty Images)

While the US was ending its destructive war in Afghanistan, politicians and the media were overflowing with concern for the Afghan people. Now that US sanctions are causing mass suffering and death in the country, they’ve lost interest.

No, it’s not August 2021, as Washington withdraws from its pointless, twenty-year occupation of the country and the Taliban seizes back control. This is 2022, and the reason you may not have heard much about it is because the solution, this time, doesn’t involve military force.

Ever since the Taliban took back power in August and September 2021, Afghanistan has been in the grip of a deadly crisis unparalleled in its already tumultuous modern history. While the Taliban are, to put it mildly, far from the country’s ideal stewards, this crisis has little to do with their policies. Rather, the causes are the worst drought in Afghanistan’s history, and the US sanctions that have devastated the nation’s economy and infrastructure from the moment the American military stopped bombing and killing.

There’s nothing anyone can do about the drought. The sanctions are a different story. $10 billion worth of assets that belong to the Afghan central bank have been frozen in the foreign vaults they’re kept in, including in the United States. The country’s $440 million worth of reserves held with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are likewise blocked. For months, the IMF, World Bank, aid organizations, and others stopped the flow of foreign aid to the country — which, before the Taliban takeover, had accounted for three-quarters of public spending and 43 percent of Afghanistan’s GDP.

To say that the results have been devastating doesn’t really capture it. Doctors and civil servants went unpaid for months, as have the hundreds of thousands of security forces who lost their jobs in the political transition. The US freeze led to a devaluation in Afghan currency and exacerbated a steep rise in the cost of basic necessities, while interrupting the flow of overseas remittances, normally accounting for 4 percent of the country’s GDP.

As early as September, United Nations officials were warning that one million kids were at risk of starving to death, more than five times the number of all people killed over the course of the entire twenty years of US war in the country. By December, the UN upped that estimate to nearly twenty-three million people facing life-threatening food insecurity in the winter, and nearly nine million approaching famine.

With Afghanistan’s health care system reliant on a $600 million World Bank program funded by the United States and other foreign governments, its health system, like its economy, is also nearing collapse. Only four hundred of the health care facilities it funds are still operating, with widespread medicine shortages and medical professionals trying to deliver babies and carry out other procedures without electricity or enough equipment. This has all come about as the country’s been ravaged by no less than six epidemics, including measles, polio, and, of course, COVID-19. Like the rest of the Global South, Afghanistan is unable to secure vaccination against COVID due to Western governments’ jealous guarding of Big Pharma profits.

Ordinary Afghans have been reduced to selling any household items they have on the side of the road or, horrifyingly, their own children, in an effort to save their entire families from starving. While Washington has, after months of sitting by watching the horror they’d set in motion unfold, finally moved to allow some humanitarian exceptions to its sanctions, a small amount of foreign aid isn’t going to be enough to replace a functioning banking system or halt a collapsing economy.

This is an almost wholly man-made crisis, and the reason it’s being engineered and stubbornly held in place is because Washington and European powers, in their telling, don’t want to “reward” the Taliban for their medieval treatment of women. This is clearly not working, though, because even as the Afghan economy continues its death spiral, the Taliban are still cutting the heads off female mannequins and barring women from traveling alone and using bathhouses.

Take a moment to think about the repugnant logic of Western governments here. The ones bearing the brunt of all this are ordinary Afghan people, whom Washington and its allies are using as ransom to force the Taliban to stop repressing . . . those same people, who these governments are busy humanitarianly starving to death. This makes no sense, and it suggests that none of it has anything to do with concerns for Afghan people’s welfare, but rather is about punishing a faction of political foes that embarrassed Western militaries.

For casual observers, all this might be a bit puzzling. After all, it was only a few months ago that the press and wider political establishment took part in one of the most brazen pro-war campaigns in recent memory to undermine and reverse a US withdrawal from the horrific war there. That push, we were told at the time, was because of political and media figures’ intense, overwhelming love and concern for the Afghan people, particularly the “women and girls” relentlessly cited by people whose hearts suspiciously only started bleeding once there was a prospect of Western bombs and bullets no longer killing them.

Miraculously, these war-hawk humanitarians found a way to silence their consciences. As Adam Johnson has documented, figures like CNN anchor Jake Tapper, Atlantic columnist Caitlin Flanagan, and NBC journalist Richard Engel — who heavily reported on the chaos of the US withdrawal and even, at times, explicitly argued against it — have simply lost interest in the Afghan people’s suffering, almost totally ignoring the humanitarian disaster that’s unfolded since, and eliding the role of Western governments in the one or two instances where they have reported on it.

This is part and parcel of the broader media coverage of the war. For years, when Washington and its allies were killing kids, bombing hospitals, and otherwise creating the widespread rage that led Afghans to decide that they were better off under the deeply reactionary Taliban, TV news coverage of the war was negligible, reaching a combined total of a mere five minutes in all of 2020 across CBS, NBC, and ABC. When it looked like the war might actually, finally end, coverage then ramped up to 345 minutes in August 2021 alone. And now that the war is over and Western governments are inflicting even greater carnage by economic means, the press has lost interest again, devoting only twenty-one minutes to the country over ten segments since September.

The same is true for those members of Congress who are always quick to bring up the plight of Afghan civilians if that’s what it takes to sell a war. Intercept reporter Lee Fang went to the Capitol in December and couldn’t get a single congressperson to come out in clear opposition to the sanctions. Both Democrat Tammy Duckworth and Republican Richard Shelby justified them on the basis of the Taliban’s behavior, with Shelby claiming that “they’ll do more harm to the people of [Afghanistan] than anybody else could,” before immediately walking away. This is, of course, not remotely true: as illiberal as the Taliban are, the suffering imposed by their policies doesn’t come close to the scale of suffering from the famine and wholesale societal collapse that US policy is currently engineering.

In a familiar pattern of US foreign policy, policymakers have substituted a military war with an economic one. The conditions in Afghanistan and the program of economic strangulation behind them is identical to what Washington is currently doing in at least three other countries whose governments it dislikes: Iran, Venezuela, and Cuba.

The United States could use its enormous economic might for a variety of laudable, urgent causes, like using targeted financial sanctions to staunch the destruction of the world’s rainforests. Instead, it’s doing it to condemn millions of innocent people to starvation and disease. As is so often the case, Western governments don’t have to do much to make the world a better place — in fact, all they have to do is stop what they’re doing.

Nobel Peace Prize winner, American poet and artist Bob Dylan, circa 1970. (photo: Unknown)

Nobel Peace Prize winner, American poet and artist Bob Dylan, circa 1970. (photo: Unknown)

Lyrics Bob Dylan Hurricane.

Written by, Bob Dylan and Jacques Levy

From the 1976 album, Desire.

Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night

Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall

She sees the bartender in a pool of blood

Cries out, “My God, they killed them all!”

Here comes the story of the Hurricane

The man the authorities came to blame

For somethin’ that he never done

Put in a prison cell, but one time he could-a been

The champion of the world

Three bodies lyin’ there does Patty see

And another man named Bello, movin’ around mysteriously

“I didn’t do it,” he says, and he throws up his hands

“I was only robbin’ the register, I hope you understand

I saw them leavin’,” he says, and he stops

“One of us had better call up the cops”

And so Patty calls the cops

And they arrive on the scene with their red lights flashin’

In the hot New Jersey night

Meanwhile, far away in another part of town

Rubin Carter and a couple of friends are drivin’ around

Number one contender for the middleweight crown

Had no idea what kinda shit was about to go down

When a cop pulled him over to the side of the road

Just like the time before and the time before that

In Paterson that’s just the way things go

If you’re black you might as well not show up on the street

’Less you wanna draw the heat

Alfred Bello had a partner and he had a rap for the cops

Him and Arthur Dexter Bradley were just out prowlin’ around

He said, “I saw two men runnin’ out, they looked like middleweights

They jumped into a white car with out-of-state plates”

And Miss Patty Valentine just nodded her head

Cop said, “Wait a minute, boys, this one’s not dead”

So they took him to the infirmary

And though this man could hardly see

They told him that he could identify the guilty men

Four in the mornin’ and they haul Rubin in

Take him to the hospital and they bring him upstairs

The wounded man looks up through his one dyin’ eye

Says, “Wha’d you bring him in here for? He ain’t the guy!”

Yes, here’s the story of the Hurricane

The man the authorities came to blame

For somethin’ that he never done

Put in a prison cell, but one time he could-a been

The champion of the world

Four months later, the ghettos are in flame

Rubin’s in South America, fightin’ for his name

While Arthur Dexter Bradley’s still in the robbery game

And the cops are puttin’ the screws to him, lookin’ for somebody to blame

“Remember that murder that happened in a bar?”

“Remember you said you saw the getaway car?”

“You think you’d like to play ball with the law?”

“Think it might-a been that fighter that you saw runnin’ that night?”

“Don’t forget that you are white”

Arthur Dexter Bradley said, “I’m really not sure”

Cops said, “A poor boy like you could use a break

We got you for the motel job and we’re talkin’ to your friend Bello

Now you don’t wanta have to go back to jail, be a nice fellow

You’ll be doin’ society a favor

That sonofabitch is brave and gettin’ braver

We want to put his ass in stir

We want to pin this triple murder on him

He ain’t no Gentleman Jim”

Rubin could take a man out with just one punch

But he never did like to talk about it all that much

It’s my work, he’d say, and I do it for pay

And when it’s over I’d just as soon go on my way

Up to some paradise

Where the trout streams flow and the air is nice

And ride a horse along a trail

But then they took him to the jailhouse

Where they try to turn a man into a mouse

All of Rubin’s cards were marked in advance

The trial was a pig-circus, he never had a chance

The judge made Rubin’s witnesses drunkards from the slums

To the white folks who watched he was a revolutionary bum

And to the black folks he was just a crazy nigger

No one doubted that he pulled the trigger

And though they could not produce the gun

The D.A. said he was the one who did the deed

And the all-white jury agreed

Rubin Carter was falsely tried

The crime was murder “one,” guess who testified?

Bello and Bradley and they both baldly lied

And the newspapers, they all went along for the ride

How can the life of such a man

Be in the palm of some fool’s hand?

To see him obviously framed

Couldn’t help but make me feel ashamed to live in a land

Where justice is a game

Now all the criminals in their coats and their ties

Are free to drink martinis and watch the sun rise

While Rubin sits like Buddha in a ten-foot cell

An innocent man in a living hell

That’s the story of the Hurricane

But it won’t be over till they clear his name

And give him back the time he’s done

Put in a prison cell, but one time he could-a been

The champion of the world

Traditional cattle farming, where cattle are left free to graze on large expanses of land, is the predominant style of ranching in Acre as well as across Brazil. (photo: Dr. Eduardo Mitke/Federal University of Acre/Mongabay)

Traditional cattle farming, where cattle are left free to graze on large expanses of land, is the predominant style of ranching in Acre as well as across Brazil. (photo: Dr. Eduardo Mitke/Federal University of Acre/Mongabay)

But in the past three decades, the thriving cattle industry has become a major threat to Acre’s forests, with livestock now outnumbering the state’s human population by a factor of four.

In 1990, Acre’s human population was 400,000, with an almost identical number of cattle, according to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). By 2020, the number of people had grown to nearly 900,000, while the number of cattle was a record high 3.8 million, IBGE data showed.

The livestock population in 2020 marked an 8.3% increase from the year before, according to IBGE data, the highest increase in all the nine states that make up the Brazilian Amazon. The number of cattle within the region grew by 4.2%, while nationwide there was an overall increase of 1.5%.

A report from the Acre state government’s data analysis foundation says the “economic potential of the state’s natural resources is immeasurable” in terms of timber, fruits and medicinal plants. Yet it’s cattle that also plays a key part in Acre’s economy. While wood products contributed 38.7% to the state’s total exports in 2020, meat products were responsible for 28.3%, according to Acre government data.

“The economy in Acre is centered on agriculture, especially livestock,” Dr. Eduardo Mitke, a veterinarian and professor of cattle farming at the Federal University of Acre, told Mongabay by phone. “There’s little economic value in fruit, and the rubber industry is over. While corn and soya have been growing in Acre in the last two or three years, the strongest economic driver in the agribusiness sector is undoubtedly livestock.”

The state capital, Rio Branco, has the highest number of cattle in Acre, with 14% of the population. The municipality of Sena Madureira is the second, with nearly 365,000 head of cattle. With 236 km² (91 mi²) of forest loss in August 2021 (15% of the total recorded in the entire Amazon), Acre entered for the first time in third place in the ranking of states that most destroyed the Amazon last year, according to data from Brazilian conservation nonprofit Imazon. Only two municipalities, Sena Madureira and Feijó, accounted for 40% of the state’s deforestation.

Several factors have fueled the growth of the cattle industry in Acre, including an increase in international demand for meat products, especially from China, according to IBGE data. Dr. Mitke said productivity in the Brazilian cattle industry has also gone up by 150% in the last 30 years, allowing ranches to grow their herds. “There’s a technological revolution. It’s slow, but it’s a revolution, nonetheless,” he said. “With improved technology, we’re able to increase the number of animals per hectare, which means we can put more cattle in the same sized area and provide a potential sustainable solution to having livestock.”

Rômulo Batista, a Greenpeace Amazon campaigner, said another possible factor is the practice of land grabbing, where unscrupulous parties occupy and exploit public land and then claim it as private property. “Unfortunately, it’s increasingly common to have livestock in the Amazon as an attempt to validate land ownership,” he told Mongabay by phone. “[The people who take the land] put cattle on the land they took to say there’s some type of farm production there in an attempt to legalize it.”

Less forest, more cattle

Activists have raised concerns about the link between the growing cattle industry and deforestation. “Of all the area that has been deforested in the Brazilian Amazon that didn’t later grow back as secondary vegetation, 90% of it is some type of pasture used for livestock nowadays,” Batista said. “We’re now seeing the destruction of the Amazon, a forest with the most biodiversity in the world, just to put two species there: grass and cattle.”

Data from Mapbiomas, a network of NGOs, universities and tech firms that include Google, show that the loss of Acre’s forests over the past 10 years is strongly correlated with the annual increase in land designated for cattle, suggesting a link between the two (see chart below). In 2020, 84,925 hectares (209,854 acres) was deforested in Acre; that same year, land designated for cattle and livestock in the state increased by an almost identical amount: 84,735 hectares (209,384 acres), Mapbiomas data showed.

Several studies indicate that the cattle industry is a major driver of deforestation, including a 2013 paper that says “in recent years, 48% of all tropical rainforest loss occurred in Brazil, where cattle ranching drives around three-quarters of forest clearing.” In 2021, with its cattle population swelling, Acre recorded its highest deforestation rate in 18 years, according to data from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). In total, 10% of forest area in Acre has so far been cut down, according to data from Brazilian conservation nonprofit Imazon. “Acre is not the most deforested state in the Amazon region,” Batista said. “But it stands out because it’s a new area of deforestation. Five, 10 years ago we were always talking about [the states of] Rondônia, Mato Grosso and Pará. Now, we have our eye on Acre.”

The agribusiness sector has justified clearing land to make way for agriculture as a positive development. “Deforestation for us is a synonym of progress, no matter how shocking that is to people,” Assuero Doca Veronez, the head of Acre’s Agricultural Federation, said in a 2020 interview. At the time of the interview, he was referring to Amacro, a planned agribusiness zone in the border area between the states of Amazonas, Acre and Rondônia. The initiative was renamed in late 2021 to the Abunã-Madera Sustainable Development Area (ZDS) and repositioned as a multisectoral and sustainable initiative.

Despite reported changes to the project’s core goals, Batista said he remains concerned about the impact of the ZDS project and the way “development” is managed in Acre. “Without proper planning, livestock and infrastructure cause both cultural and environmental destruction.”

Studies suggest it’s possible to increase cattle production while relieving the pressure on the Amazon rainforest. “This paradigm of horizontal expansion of agriculture over ecosystems is outdated,” a 2020 study says, referring to the traditional method of cattle ranching commonly used in Brazil, where small herds graze on vast expanses of land. The study suggests using a more intensive method that increases production sustainably by raising more cattle on smaller areas of land.

Dr. Mitke said it’s “economically, environmentally and technically viable to have cattle in Acre while conserving the Amazon” if done in the right way. He added there’s even opportunity to reforest deforested areas while increasing cattle production.

However, he said the current trend of cattle growth in Acre isn’t sustainable, and farmers lack technical assistance and sustainable farming know-how. “The farmer [in Acre] doesn’t know how to expand without deforesting. We need to show them other farming alternatives that don’t harm the environment,” Dr. Mitke said. “We don’t have the slightest need to deforest any more. And if we don’t farm in the right way, we will undoubtedly end up destroying the Amazon.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Evening Roundup, May 28...plus a special thank you to our Contrarian family Featuring Jen Rubin, Katherine Stewart, Brian O'Neill, Jenni...