Activist Group Reports that Fed Chair Powell Traded During FOMC Restricted Periods: We Fact-Checked It and It’s True

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 10, 2022 ~

An anonymous activist group called Occupy the Fed reported in a Substack article on Sunday that Fed Chair Jerome Powell traded on the final day of a Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting on April 29, 2015, when he was a Fed Governor, and also on the final day of an FOMC meeting on December 11, 2019, when he was Fed Chair.

Powell’s trading directly violates the Fed’s written policy which prohibits trading “during the period that begins at the start of the second Saturday (midnight) Eastern Time before the beginning of each FOMC meeting and ends at midnight Eastern Time on the last day of the meeting.” The FOMC meetings are typically when the most sensitive and market-moving information occurs at the Fed, including votes on hiking or lowering interest rates and other confidential actions.

Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan, Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren and Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida have resigned over their own individual trading scandals and not one of them has been charged with anything as directly in violation of Fed policy as trading on the very day the FOMC is in session.

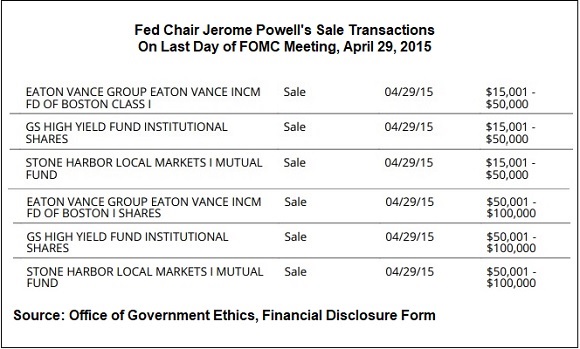

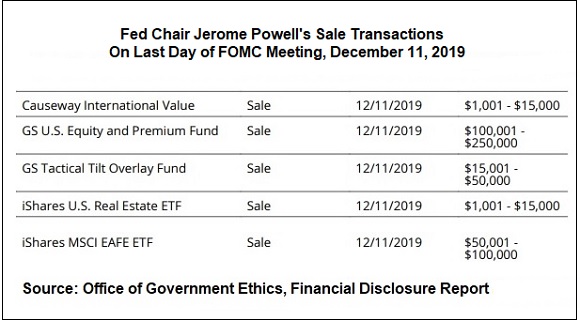

We fact-checked the Occupy the Fed report by downloading the dates of all FOMC meetings from 2015 through 2020 and comparing them to the trading transactions listed on Powell’s financial disclosure forms filed with the Office of Government Ethics (OGE) for years 2015 through 2020. We can verify that Powell traded on April 29, 2015 and on December 11, 2019. Both were the final day of the FOMC meeting. (You can read the minutes of those respective FOMC meetings here and here.)

The charts below show what Powell sold on those dates. We have eliminated any purchase transactions to avoid any possibility that the Fed would claim that these were made for dividend reinvestment purposes.

The FOMC meets eight times a year, roughly every six weeks. Multiply that by the six years of financial disclosures that the OGE has made available for Powell and you have a total of 48 FOMC meetings. Multiply the 48 meetings by two, since the FOMC meets for two days, and Powell had 96 opportunities to screw up and accidentally trade on an FOMC meeting date. But it happened on only two days during that six-year span of time – according to what we know thus far. And in both the years of 2015 and 2019, highly unusual activities were occurring at the Fed.

The year 2015 would mark the first time that the Fed had raised interest rates since it slashed them to the zero-bound range in 2008. There was a great deal of media talk in April regarding what was going to happen in various markets when the Fed raised its benchmark Fed Funds rates. The Fed didn’t raise its benchmark rate until December 17, 2015.

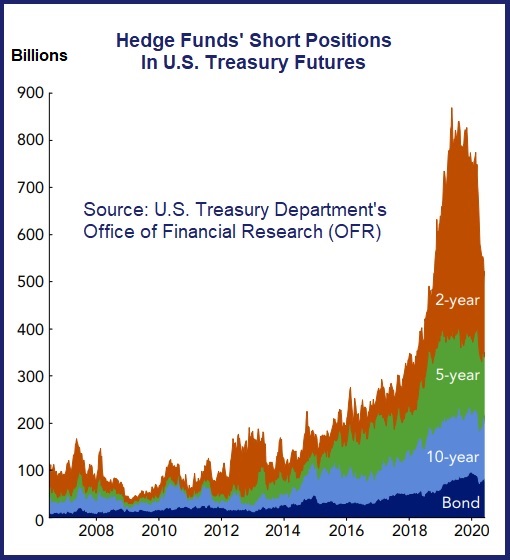

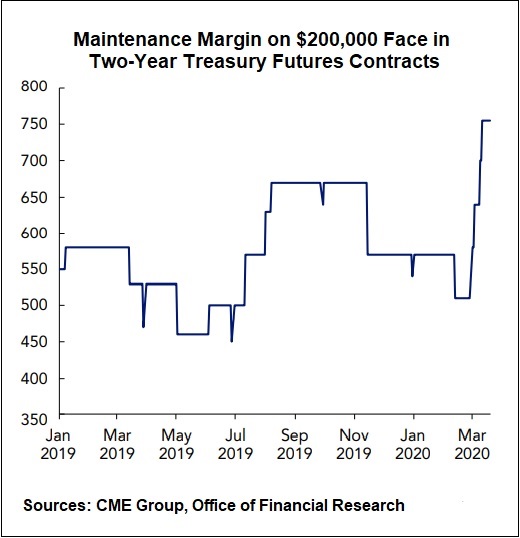

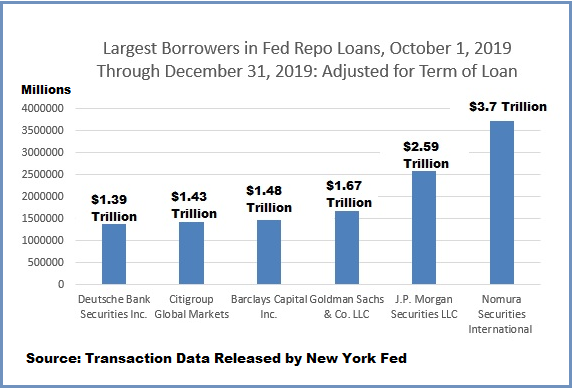

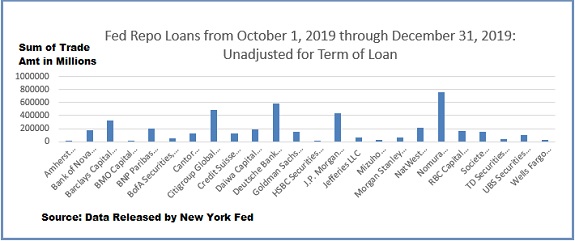

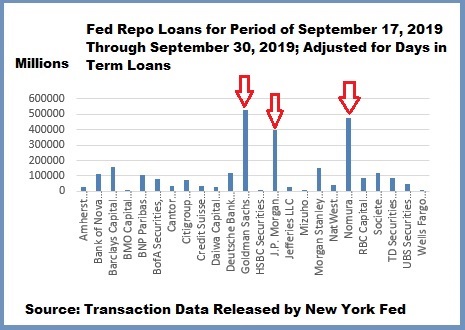

The year 2019 marked the beginning of an unprecedented, emergency repo lending operation by the Fed. While the Fed made public that the repo loans were being provided to its 24 primary dealers, only the Fed knew that six large trading houses on Wall Street were getting the lion’s share of those loans. One of the six was Goldman Sachs. On December 11, 2019, the final day of the FOMC meeting, Powell sold between $115,000 and $300,000 of two Goldman Sachs proprietary mutual funds. The funds are listed as “GS” rather than Goldman Sachs on his financial disclosure forms. (See chart below.)

According to the Fed’s own H.4.1 report, on December 11, 2019, the same day that Powell dumped between $167,000 and $430,000 of predominantly stock mutual funds and ETFs, the Fed had an outstanding balance of $212.95 billion in emergency repo loans that had been used to prop up trading houses on Wall Street, including Goldman Sachs.

A larger question in all of this is why Powell is even allowed to be holding Goldman Sachs proprietary funds since Goldman Sachs is supervised by the Fed.

The Occupy the Fed report also makes the following charge against Powell:

“Instead of providing specific dates for the majority of his transactions, Powell improperly groups trades of like securities behind the phrase ‘Multiple’ on every OGE form he has filed.”

A report last year in the Washington Post indicated that a Fed spokeswoman had indicated to them that these “multiple” transactions “were for automatic dividend reinvestments – essentially transactions on autopilot and not subject to individual decisions.”

Very little is known about the Occupy the Fed group that scooped mainstream media with this story other than that it appears to be a fairly new group. Its Twitter account shows that it was opened in January 2021. Its Substack account shows it began on January 17, presumably of this year since only two articles are listed. Under “Who are we” on the Substack account, the following description is provided:

“We’re a group of like-minded regular people (workers, professionals, seniors, savers and others) who are disgusted and fed up with systemic corruption at the Federal Reserve and the total perversion of our American capitalist democracy. We’ve taken no money from special interests. We are doing this on personal time and expense because we’ve had enough.”

We have reached out to the Fed’s communications office for an explanation of Powell’s trading on these two FOMC meeting dates. We’ll update this article if we receive a response.

Powell’s term as Fed Chair expired this past Saturday and he is currently serving as Chair Pro Tempore. President Biden has nominated Powell to serve a second four-year term as Fed Chair but that requires an up vote by the Senate Banking Committee and the full Senate. Those votes have yet to happen, making Powell the first Fed Chair in a quarter century to be serving in a Pro Tempore capacity.

This latest report from Occupy the Fed simply adds to the withering criticism around Powell’s leadership of the Fed. Senator Elizabeth Warren, who sits on the Senate Banking Committee, called Powell a “dangerous man to head up the Fed” over his record of weakening Dodd-Frank legislative protections covering Wall Street megabanks. Powell has also presided over the worst trading scandal in the Fed’s history. His cozy relationship with Blackrock while the Fed awarded them three no-bid contracts has also raised eyebrows. Adding to all of this is the general consensus that Powell has fallen way behind the curve on the inflation that is ravaging Americans’ ability to make ends meet.

Trust in the Fed has been seriously weakened under Powell. That is reason enough for President Biden to reconsider this nominee.

Editor’s Update: The Fed has provided a detailed response. See the response and our critique here.