Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg's metaverse is no utopian vision — it's another opportunity for Big Tech to colonize our lives in the name of profit.

Silicon Valley has a long history of big dreams that are not realized, from the libertarian utopia that the internet was framed as in its early days to the ubiquitous autonomous vehicles that were supposed to have replaced car ownership by now. The metaverse is likely to suffer the same fate, but that doesn’t mean it will have no impact at all. As Brian Merchant has explained, the tech industry is in desperate need of a new framework to throw money at after so many of its big bets from the past decade have failed, and the metaverse could be poised to take that place.

In the few weeks since Zuckerberg’s keynote address, other companies have embraced aspects of the metaverse, but also have shown how malleable the term can be. On November 2, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella made his own metaverse pitch centered around enterprise and gaming. He cast a wide net arguing the concept encompassed existing video chat and collaboration tools, as well as games like Halo and Minecraft, and that those metaverse applications would be enhanced by virtual environments. As Nadella put it, the metaverse allows Microsoft to “embed computing in the real world, and to embed the real world into computing.”

I’m not sure that’s as attractive a statement as Nadella wants us to believe, but his focus on games and work may be a good reflection of what the metaverse could ultimately amount to. It remains to be seen whether we’ll all be pushed into virtual environments similar to how internet use has become a mandatory part of getting by in the modern world, but it’s much easier to see how video game companies and our workplaces could incentivize or even mandate our participation.

Taking Inspiration From Games

The growing hype around the metaverse is inspired, first and foremost, by recent developments in the video game industry. We can’t ignore how science fiction like Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, where the term “metaverse” originates, or Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One, a copy of which used to be given to all new employees at Facebook’s Oculus division, inspired the concept, but the business case comes from games.

Last year, venture capitalist Matthew Ball wrote an influential essay making the investors’ pitch for the metaverse and Fortnite was at the center of it. He argues that “Fortnite began as a game, but it quickly evolved into a social square.” Players came to play, but stayed to hang out and chat as the game built out additional spaces beyond the core hundred-player battle royale experience.

Companies have held events to promote movies like Star Wars, and major artists like Travis Scott and Ariana Grande have held virtual concerts. Corporations are also able to exploit their intellectual property by offering in-game items based on, for example, Marvel or DC characters. That’s also how Fortnite makes most of its money: players convert real money to V-bucks which they can use to buy virtual goods or the Battle Pass that provides regular game updates.

Ball believes the metaverse will extend beyond what’s currently offered on Fortnite, but sees it as a good demonstration of a “proto-Metaverse’ because of the socialization and commercial activity happening on it. Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney has seized on the metaverse narrative to raise additional funds for the company, but also to present himself in opposition to the existing tech industry. Instead of their closed ecosystems, he claims the metaverse will be an open and interoperable platform.

As part of the effort to show contrast, Epic sued Apple over its App Store terms, but as the judge in the case noted, the company would see considerable gains if it got its way. It’s a reflection of a trend in the tech industry’s history where promises of openness and individual empowerment often give way to corporate interests, if it’s not just PR from the beginning.

In the broader gaming space, EA, Square Enix, Take Two, and Ubisoft are jumping on the bandwagon with recent positive statements about NFTs fueled by the ridiculous amount of investor money being thrown at blockchain-based games. Some of these companies are considering making “play-to-earn” games that bring the speculative mania of NFTs into games by incentivizing players to keep playing for the chance to get valuable NFTs they can resell. In effect, gaming becomes their job because the virtual goods can yield ridiculous amounts of money. But the metaverse may do much more to change how people work.

A New Attack on Workers

The tech industry has a history of altering how people think about employment. In the 1980s, Silicon Valley companies were associated with a push for less hierarchical workplace structures, such as at companies like Apple, while in the aftermath of the recession it birthed the gig economy, which used the app-based delivery of services to misclassify workers as independent contractors, denying them the rights and benefits of employee status. The metaverse could alter things in several ways.

As the recent Microsoft announcements and Facebook’s own Horizon Workrooms demonstrate, applications for work are considered central to the metaverse, but why the sudden interest in virtual office environments? During the pandemic, many workforces, including those in tech, went remote to reduce the spread of COVID-19, but now many workers don’t want to go back. Employers deployed a whole range of software to track their employees since they weren’t in the office and metaverse applications would offer new and improved ways of doing that. If you can’t be in the physical office, you’ll be expected to be present in the virtual one — and monitored every minute you’re there.

But the transformation could be much more significant than an expansion of surveillance. Companies like Uber and Amazon not only rolled out algorithmic management systems through the 2010s to limit workers’ autonomy and increase production targets, but they also expanded the number of workers engaging in piece work through the gig economy and platforms like Mechanical Turk. Ball writes that the metaverse will be “the next great labour platform,” while Zuckerberg said it will give “people access to jobs and more places, no matter where they live.”

In the context of Silicon Valley’s reliance on contract workers and outsourcing, that’s not a good thing to hear. Gig workers have warned that lowering their working standards was the first step in an effort to do so in the wider economy, and the workplace technologies heralded by the metaverse’s champions could be key to enabling the next big assault on workers’ rights.

Returning to play-to-earn, similar schemes have been around for years. In the early 2000s, workers primarily in the Global South engaged in gold farming where they would earn in-game currency in massive multiplayer online games, then sell it to players often located in Western markets. Ball uses this as an example of how work can be done in the metaverse, but as Merchant said in a recent interview on Tech Won’t Save Us, this is a vision where existing “disparities will be enshrined and transported over to this virtual world.” Their vision for virtual labor might sound promising, but it would make it even harder for workers to demand their rights be respected and have any leverage over their employers.

The Metaverse Must Be Stopped

The metaverse is an expansive vision that would see digital technologies colonize many more aspects of our lives. As we saw during the pandemic, tech companies’ revenues and profits soar when we’re forced to spend more time using digital services instead of being out in the physical world. But while it won’t soon reach the scale contained in the visions of Ball and Zuckerberg — if it ever does — it could be a reality for gamers and in certain workplaces much sooner.

Video game companies have successfully altered how games are made and the monetization strategies embedded within them for years to maximize profits, while employers can easily make specific services mandatory for workplace use, as they did with Slack and Zoom, giving them a foothold to expand into the consumer market. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t avenues to stop them.

In 2017, EA was forced to withdraw microtransactions and loot boxes from Star Wars Battlefront II after anger from players because the monetization features were designed in a “pay-to-win” fashion that incentivized people to spend real money. Following the controversy there were also regulatory responses in a number of countries, and Gamesindustry.biz contributing editor Rob Fahey believes play-to-earn games could face similar scrutiny. Beyond that, there is a growing tech labor movement that is using its collective power to push back on its employers when they take actions that cross ethical lines or put their colleagues at risk.

Silicon Valley tends to feel it can do whatever it wants. Its major companies have ignored regulations with little consequence and shaped how we communicate to increase profits despite causing social harm. As the pressure for the metaverse to become reality grows, we need to be ready to oppose it. But we should also start thinking beyond the tech industry’s visions for technological solutions that serve their business interests and instead imagine how tech can be developed for the public good.

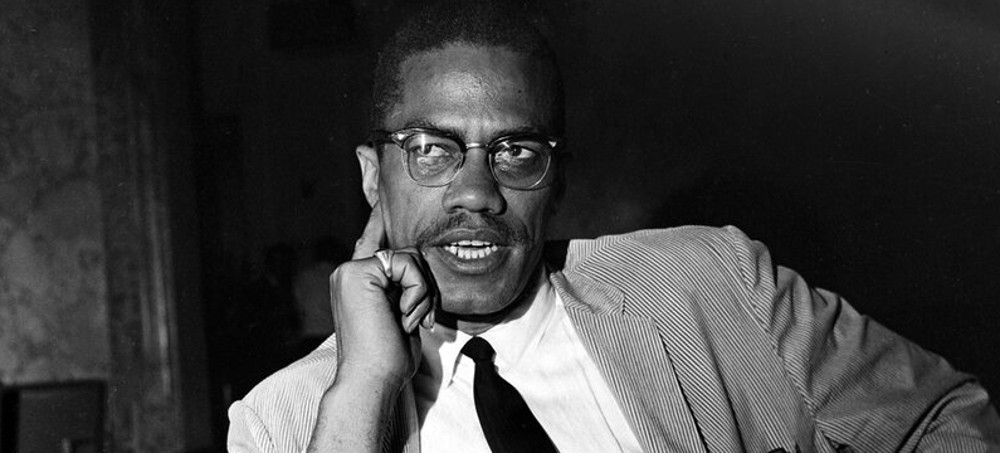

Malcolm X speaks at a news conference in the Hotel Theresa in New York on May 21, 1964. Two of the three men convicted in his 1965 killing are set to be cleared Thursday after insisting through the years that they were not guilty. (photo: AP)

Malcolm X speaks at a news conference in the Hotel Theresa in New York on May 21, 1964. Two of the three men convicted in his 1965 killing are set to be cleared Thursday after insisting through the years that they were not guilty. (photo: AP)

District Attorney Cy Vance and lawyers representing the two men announced that they "will move to vacate the wrongful convictions" of Muhammad Aziz and Khalil Islam on Thursday — a move that debunks the official account about the assassination of the fiery orator who was murdered onstage in 1965 in a hail of bullets in front of hundreds of people, including his daughters and pregnant wife.

Aziz and Islam, members of the Nation of Islam, were sentenced to life in prison a year later alongside Mujahid Abdul Halim, then known as Talmadge Hayer and Thomas Hagan.

While Halim confessed to the murder during the trial, he testified that neither Aziz nor Islam was involved. But he declined to name the men who had joined him in the attack.

Meanwhile Islam, then known as Thomas 15X Johnson, and Aziz, then known as Norman 3X Butler, always maintained their innocence.

Halim eventually gave the names of four men who he said were his accomplices in 1978. But his testimony failed to persuade officials to reopen the investigation of the murder and a judge rejected a motion to vacate the convictions.

Halim was released in 2010 after spending more than 40 years in prison. Islam was released in 1987 and died in 2009. Aziz, who was released on parole in 1985, is still fighting to clear his name with the help of the Innocence Project.

Suspicion and speculation that the FBI and NYPD had mishandled the case, deliberately withholding or ignoring information that would have ensured Islam and Aziz's freedom, has persisted for more than a half-century. And in 2020, a documentary called Who Killed Malcolm X? raised a slew of new questions ultimately prompting Vance to launch a new investigation.

"The day of the murder, which was a Sunday morning, I was laying over the couch with my [injured] foot up and I heard it over the radio," Aziz remembers in Who Killed Malcolm X?

According to the Innocence Project, "In addition to multiple alibi witnesses, a doctor who treated Aziz at Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx just hours before Malcolm's murder took the stand in Aziz's defense."

Over the last 22 months, Vance's team has unearthed FBI documents that would have cast doubt on the involvement of Aziz and Islam. That evidence was available at the time of the trial but was withheld from the defense and prosecution.

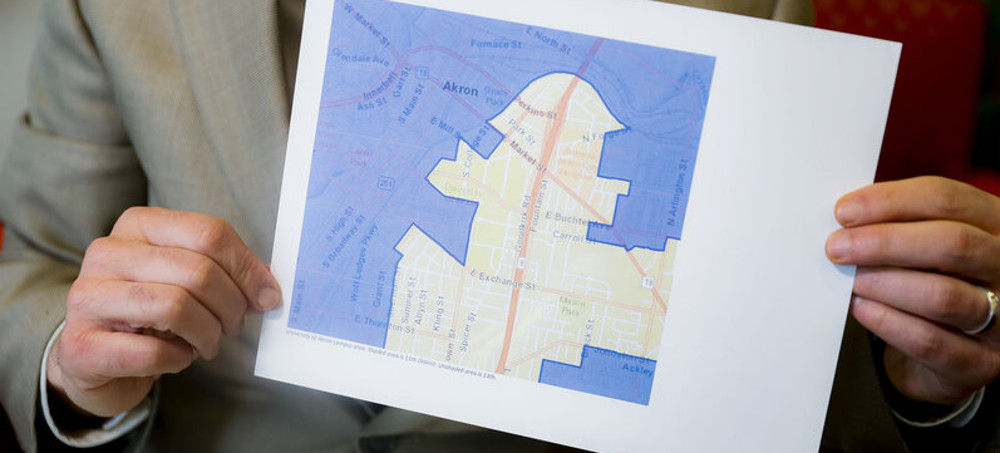

David Niven, a professor of political science at the University of Cincinnati, holds a map depicting a gerrymandered Ohio district. (Photo: John Minchillo/AP)

David Niven, a professor of political science at the University of Cincinnati, holds a map depicting a gerrymandered Ohio district. (Photo: John Minchillo/AP)

This partisan free-for-all could perpetuate Republican minority rule in Congress and state legislatures for the next decade – if not longer

Don’t expect a tight rematch next year. Utah’s new congressional map, approved by the state legislature this week, divides Salt Lake county into four pieces, attaching pieces to conservative rural counties hundreds of miles away. It ignores the recommendation of an independent commission established by initiative in 2018, and scatters voters here across four districts so uncompetitive and safely Republican that the non-partisan Princeton Gerrymandering Project graded it an F.

It’s a similar story in Oklahoma, where the new Republican map cracks Oklahoma City into three different congressional districts, dismantling the competitive fifth district – captured in 2018 by a Democrat, Kendra Horn – and ensuring a big Republican advantage for every seat. The cartography needed to be more creative in New Hampshire, where Republicans took two competitive districts that have largely elected Democrats over the last 15 years and guaranteed themselves one by moving 75 towns and 365,000 people into a new district.

The quiet evisceration of the few remaining competitive seats in conservative-leaning states has flown under the radar compared with greedier Republican gerrymanders in Texas, Ohio, North Carolina and Georgia, where the estimated net of seven to 10 Republican seats would be enough to flip the US House of Representatives in 2022 and perhaps keep it in Republican hands for the next decade.

Yet Republicans could reinforce their primacy through 2031 – and cut off an important road that helped Democrats retake the House in 2018 – by turning battleground seats into safe strongholds not only in Oklahoma City and Salt Lake City, but with creative cracking and packing of Democratic voters in the suburbs of Indianapolis, Little Rock, Omaha, Louisville, Nashville, Kansas City and Spartanburg.

Nebraska’s second congressional district, for example, one of just 16 remaining “crossover” districts where the vote for the US House and president diverged, becomes slightly more Trumpy, trading suburbs close to Omaha for rural counties to the west. This district has national implications, as it is one of two nationwide that award presidential electors. The subtle shift matters; Biden carried this district by fewer than 23,000 votes.

In Indiana’s fifth, Republicans locked in a map giving them a 7-2 advantage by shifting Democratic suburbs in Marion county into an adjacent Democratic district – packing the liberal voters into a single Indianapolis district. By reworking that seat, the Republican party pinned Democrats into two overwhelmingly Democratic districts, eliminated the last competitive seat that might have become closer over the next decade, and assured themselves 78% of the seats in a state Trump won in 2020 with 57%.

In Arkansas, where the new congressional map divides Black neighborhoods in Little Rock across multiple districts to ensure a partisan edge for Republicans, the Republican governor found the racial gerrymander so distasteful that he refused to sign it. (It became law anyway, without his signature.)

Kansas has not yet introduced a new congressional map, but during the 2020 campaign, the state senate president vowed to gerrymander the state’s single Democratic member of Congress out of office if Republicans won a veto-proof supermajority in the state legislature. They did.

South Carolina, meanwhile, has slow-walked new maps and pushed the process into next year, most likely to narrow the window for litigation challenging the plan. Republicans are expected to reinforce the first district seat, won by a Democrat in 2018 by 4,000 votes, and then recaptured by the Republican challenger in 2020 by 5,500 votes.

Democrats have done some gerrymanders of their own this cycle. It’s just that Republicans are better equipped to make gains. Oregon Democrats claimed the state’s new seat for themselves; that pickup will be mitigated by a new conservative seat nabbed by Republicans in Montana. Illinois Democrats added one liberal seat and eliminated a conservative seat; Ohio Republicans did the opposite move. Democrats might make a move on the last conservative seat in Maryland and look to gain two or three seats in New York; but that only counters Republican pickups in North Carolina – where new Republican maps will require Democrats to win by seven percentage points to have a shot at even half of the 14 congressional seats.

The maps offer no additional gains for Democrats. Republicans still net seats in Texas, Georgia, Florida, New Hampshire and Kansas, in addition to likely gains in Tennessee and Kentucky, and sandbagging competitive seats in Utah, Oklahoma, Nebraska, South Carolina and Indiana. It shrinks the map dangerously for Democrats, at a time when Republicans need to win only five seats to capture the House. And it portends a future in which an election similar to 2020 – in which Democratic US House candidates won 4.6m more votes than Republicans – could place the House under Republican rule regardless of the people’s will.

This partisan free-for-all could perpetuate Republican minority rule in Congress and state legislatures for the next decade, if not longer. Much of it was made possible by the gerrymanders of a decade ago, still providing Republican advantages in states like North Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Ohio and Wisconsin. It has been enabled by the US supreme court, which closed the federal courthouses to partisan gerrymandering claims in 2019 and gave lawmakers a green light for ever more egregious redistricting schemes. These maps have been enacted by Republicans at the same time that they have blockaded congressional action on democracy reform and the Freedom to Vote Act that would end this anti-democratic behavior by all sides. And all of this could hasten a constitutional crisis in 2024 if a gerrymandered US House and gerrymandered state legislatures refuse to certify electors, or send multiple slates of electors, to Congress.

When Utah’s governor refused entreaties to veto his state’s gerrymandered congressional maps, which effectively preclude competitive elections until at least 2032, he told voters that they should simply elect people who might be interested in fair maps next time around. Easy, right? Only how are they supposed to do that when the current legislators control the maps and draw themselves every advantage?

Republican legislators are barricading themselves into castles of power and pulling up the drawbridge. It’s close to checkmate. Voters are running out of avenues – and time – to do anything to stop it.

Andy Browne sued the city of Minneapolis after being shoved to the ground by a Minneapolis police officer days after George Floyd's police killing after he questioned the officers' slow response. (Photo: Minnesota Reformer)

Andy Browne sued the city of Minneapolis after being shoved to the ground by a Minneapolis police officer days after George Floyd's police killing after he questioned the officers' slow response. (Photo: Minnesota Reformer)

Lawsuits filed in the wake of George Floyd’s killing are piling up and hurting city finances

It was just days after Floyd was killed by police on the street on May 25, 2020, and the man had thrown debris at mourners and hurled a brick through the front door of Cup Foods on that corner.

A tattoo and his cell phone led volunteers patrolling the memorial to believe he was a white supremacist. They detained the man and called the police so he would be taken away and charged with vandalism.

After 30 minutes, with no police in sight, they called the police dispatcher again, who told them to take him a couple of blocks away, to 38th Street and Oakland Avenue.

The citizens loaded him into the back of Browne’s pickup and drove there.

When six officers finally arrived — after more than an hour and two more calls to dispatch — Browne asked one of them, “What’s with the dicking around with changing spots?”

The officer responded by shoving Browne to the ground, and then the four squad cars sped off, video of the incident shows. The citizens had no choice but to release the suspect into the night.

Afterward, Browne filed a complaint with the police department and sued six officers, alleging excessive force and retaliation.

Browne said he simply wanted to know why it took 90 minutes to get a police response for someone who damaged property and was trying to incite violence.

“I’m a Minneapolis taxpayer,” he said. “This is my community.”

Claims could cost city $111 million

Browne’s lawsuit is just one of many 2020 general liability claims that a recently released actuarial study estimates could ultimately cost the city more than $111 million.

The city of Minneapolis was hit with a flurry of lawsuits dating to the weeks after Floyd’s killing — when protests and riots rocked the metro — by everyone from Floyd’s family to protesters and journalists injured by police.

The bulk of the cost, $84 million, stems from 13 officer-misconduct claims of $2 million or more each — all tied to incidents in the 15 days following Floyd’s death. Six more misconduct claims were made with estimated losses of between $250,000 and $2 million.

“I’ve got plans for a fair amount of that,” joked Robert Bennett, an attorney who represented the family of Justine Ruszczyk Damond, who was shot by former officer Mohamed Noor in 2017 after she called 911 to report a possible crime. Her family won a $20 million settlement from the city in 2019.

Bennett represents John Pope, who was 14 years old when Derek Chauvin hit him in the head with a flashlight twice before kneeling on his back for 17 minutes as he pleaded that he couldn’t breathe. That was in 2017, three years before Floyd would die under Chauvin’s knee. Bennett also represents Soren Stevenson, who lost an eye after being hit by police with a rubber bullet while protesting Floyd’s killing.

The study estimates the city will pay out about $15 million per year through 2025 for its general liability claims. And that assumes the largest claims — more than $2 million — won’t be settled and paid until after 2025.

Minneapolis is self-insured, so legal settlements are paid out of city funds.

The city had been averaging about $7 million per year in projected losses since 2015, but that figure jumped to $24 million in 2017, and then skyrocketed to $111 million last year. That’s 10 times what used to be in a bad year for the city.

The amount needed to settle all outstanding general liability claims against the city increased from $43 million to $119 million by the end of last year, primarily due to MPD officer-misconduct claims associated with the protests and riots following Floyd’s death. The city settled with Floyd’s family for a historic $27 million this year.

$29 million in workers’ comp payouts projected

Meanwhile, the city is also paying out big bucks due to an increase in workers’ comp claims, primarily post-traumatic stress disorder claims by police employees.

The city had been averaging about $10 million in projected workers’ comp payouts annually since 2015. That figure jumped to $29 million last year, largely driven by police employee claims, according to the study.

The city averaged 169 police workers’ comp claims from 2014 to 2019; that number spiked to 370 in 2020.

Historically, the average PTSD claim cost the city $170,000. Current PTSD claims are estimated to cost $175,000 per claim, which totaled more than $20 million for 115 claims last year.

The study estimated 20 PTSD claims would be paid out each of the next five years at a cost of $175,000 per claim, or $17.5 million total over five years. But that number is likely outdated:

Attorney Ronald Meuser Jr. has said he represents about 200 Minneapolis cops and firefighters who filed workers’ comp claims in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder. And millions of dollars worth of workers’ comp settlements have been approved by the City Council this year.

The study estimated the self-insurance fund’s outstanding losses — or the cost of unpaid claims — for workers’ comp and general liabilities at nearly $173 million, compared to $79 million at the end of 2019.

The estimated cost of unpaid claims for all six funds in the self-insurance fund (such as the health and dental insurance funds) was $206 million.

The self-insurance fund’s net position for all six funds — which is akin to your savings account, minus your mortgage and car balances, if you had to pay them off today — was negative $98 million at the end of 2020, down nearly $78 million from the prior year.

Browne settled

As part of his lawsuit, Andy Browne’s attorney obtained body camera video showing the cop shoving Browne.

The bodycam showed that as the cops were driving away, the cop told his partner, “I can’t let him approach me like that. He just can’t talk to me that way.”

“You’re running really hot right now,” his partner replied.

Browne eventually settled with the city, after getting what’s called a Rule 68 offer, which is designed to encourage early settlements.

He was told if he didn’t take the $10,000 offer, he’d have to foot the bill even if he won and the judgement was less than that.

It wasn’t about money, he said. His goal was to get the story out.

“I was just trying to get a bad apple out of my neighborhood,” Browne said.

A prisoner is escorted through California's San Quentin State Prison. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty)

A prisoner is escorted through California's San Quentin State Prison. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty)

An Associated Press investigation has found that the federal Bureau of Prisons, with an annual budget of nearly $8 billion, is a hotbed of abuse, graft and corruption, and has turned a blind eye to employees accused of misconduct. In some cases, the agency has failed to suspend officers who themselves had been arrested for crimes.

Two-thirds of the criminal cases against Justice Department personnel in recent years have involved federal prison workers, who account for less than one-third of the department’s workforce. Of the 41 arrests this year, 28 were of BOP employees or contractors. The FBI had just five. The Drug Enforcement Administration and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives each had two.

The numbers highlight how criminal behavior by employees festers inside a federal prison system meant to punish and rehabilitate people who have committed bad acts. The revelations come as advocates are pushing the Biden administration to get serious about fixing the bureau.

In one case unearthed by the AP, the agency allowed an official at a federal prison in Mississippi, whose job it was to investigate misconduct of other staff members, to remain in his position after he was arrested on charges of stalking and harassing fellow employees. That official was also allowed to continue investigating a staff member who had accused him of a crime.

In a statement to the AP, the Justice Department said it “will not tolerate staff misconduct, particularly criminal misconduct.” The department said it is “committed to holding accountable any employee who abuses a position of trust, which we have demonstrated through federal criminal prosecutions and other means.”

Attorney General Merrick Garland has said his deputy, Lisa Monaco, meets regularly with Bureau of Prisons officials to address issues plaguing the agency.

Federal prison workers in nearly every job function have been charged with crimes. Those employees include a teacher who pleaded guilty in January to fudging an inmate’s high school equivalency and a chaplain who admitted taking at least $12,000 in bribes to smuggle Suboxone, which is used to treat opioid addiction, as well as marijuana, tobacco and cellphones, and leaving the items in a prison chapel cabinet for inmates to retrieve.

At the highest ranks, the warden of a federal women’s prison in Dublin, California, was arrested in September and indicted this month on charges he molested an inmate multiple times, scheduled times where he demanded she undress in front of him and amassed a slew of nude photos of her on his government-issued phone.

Warden Ray Garcia, who was placed on administrative leave after the FBI raided his office in July, allegedly told the woman there was no point in reporting the sexual assault because he was “close friends” with the person who would investigate the allegation and that the inmate wouldn’t be able to “ruin him.” Garcia has pleaded not guilty.

Garcia’s arrest came three months after a recycling technician at FCI Dublin was arrested on charges he coerced two inmates into sexual activity. Several other workers at the facility, where actresses Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin spent time for their involvement in the college admissions bribery scandal, are under investigation.

Monaco said after Garcia’s arrest that she was “taking a very serious look at these issues across the board” and insisted she had confidence in the bureau’s director, Michael Carvajal, months after senior administration officials were weighing whether to oust him.

In August, the associate warden at the Metropolitan Detention Center in New York City was charged with killing her husband — a fellow federal prison worker — after police said she shot him in the face in their New Jersey home. She has pleaded not guilty.

One-fifth of the BOP cases tracked by the AP involved crimes of a sexual nature, second only to cases involving smuggled contraband. All sexual activity between a prison worker and an inmate is illegal. In the most egregious cases, inmates say they were coerced through fear, intimidation and threats of violence.

A correctional officer and drug treatment specialist at a Lexington, Kentucky, prison medical center were charged in July with threatening to kill inmates or their families if they didn’t go along with sexual abuse. A Victorville, California, inmate said she “she felt frozen and powerless with fear” when a guard threatened to send her to the “hole” unless she performed a sex act on him. He pleaded guilty in 2019.

Theft, fraud and lying on paperwork after inmate deaths have also been issues.

Earlier this month, three employees and eight former inmates at the notorious New York City federal jail where financier Jeffrey Epstein killed himself were indicted in what prosecutors said was an extensive bribery and contraband smuggling scheme. The Justice Department closed the jail in October, citing deplorable conditions for inmates. Last year, a gun got into the building.

One of the charged employees, a unit secretary, was also accused of misrepresenting gang member Anthony “Harv” Ellison as a “model inmate” to get him a lesser sentence.

The Bureau of Prisons, which houses more than 150,000 federal inmates and employs about 37,500 people, has lurched from crisis to crisis in the past few years, from the rampant spread of coronavirus inside prisons and a failed response to the pandemic to dozens of escapes, deaths and critically low staffing levels that have hampered responses to emergencies.

In interviews with the AP, more than a dozen bureau staff members have also raised concerns that the agency’s disciplinary system has led to an outsize focus on alleged misconduct by rank-and-file employees and they say allegations of misconduct made against senior executives and wardens are more easily brushed aside.

“The main concern with the Bureau of Prisons is that wardens at each institution, they decide if there’s going to be any disciplinary investigation or not,” said Susan Canales, vice president of the union at FCI Dublin. “Basically, you’re putting the fox in charge of the henhouse.”

At the federal prison in Yazoo City, Mississippi, the official tasked with investigating staff misconduct has been the subject of numerous complaints and multiple arrests. The bureau has not removed him from the position or suspend him — a deviation from standard Justice Department practice.

In one instance, a prison worker reported that the official assaulted him inside a housing unit, according to a police report obtained by the AP. Internal documents detail allegations that the official grabbed the officer’s arm and trapped him inside an inmate’s cell, blocking his path.

The same official was arrested in another instance when a different employee contacted the local sheriff’s office, accusing him of stalking and harassing her. The AP is not identifying the official by name because some of the criminal charges were later dropped.

In both instances, the victims said they reported the incidents to the prison complex warden, Shannon Withers, and to the Justice Department’s inspector general. But they say the Bureau of Prisons failed to take any action, allowing the official to remain in his position despite pending criminal charges and allegations of serious misconduct.

A bureau spokesperson, Kristie Breshears, declined to discuss the case or address why the official was never suspended.

Breshears said the agency is “committed to ensuring the safety and security of all inmates in our population, our staff, and the public” and that allegations of misconduct are “thoroughly investigated for potential administrative discipline or criminal prosecution.”

The bureau said it requires background checks and carefully screens and evaluates prospective employees to ensure they meet its core values. The agency said it requires its employees to “conduct themselves in a manner that fosters respect for the BOP, Department of Justice, and the U.S. Government.”

Mexican marines observe the burning of kilos of cocaine that were seized in the port city of Veracruz, Mexico, on January, 16, 2018. (Photo: Victoria Razo/Getty)

Mexican marines observe the burning of kilos of cocaine that were seized in the port city of Veracruz, Mexico, on January, 16, 2018. (Photo: Victoria Razo/Getty)

In the years after the U.S. pledged to invest in human rights and rule of law, the Pentagon spent millions training elite Mexican units how to fight.

Drawing international condemnation, the disappearances in Tamaulipas are significant not only for the acts the Mexican marines are accused of perpetrating but also because the marines, as an institution, have been the U.S. government’s most trusted drug war ally in Mexico for more than a decade, receiving extensive training, operational support, and praise from the U.S. military and law enforcement agencies. A new database released this week provides the most detailed picture to date of what the U.S. government’s relationship to the Mexican marines has looked like on the ground, revealing the extensive tactical training that the Pentagon has provided to the marines’ elite units and other elements of the Mexican military.

Launched by the Mexico Violence Resource Project at the University of California, San Diego, the database allows users to search through more than 6,000 instances of U.S. military training for Mexican security forces spanning nearly two decades and totaling nearly $144 million in U.S. taxpayer funding. According to Michael Lettieri, a managing editor of the Mexico Violence Resource Project and lead analyst and designer of the project, the data, drawn from annual Pentagon and State Department reports to Congress, reveals that tactical and lethal training for Mexican military units — especially the Mexican marines — by the U.S. military has increased substantially over the past decade while human rights instruction has sharply decreased.

“One hand is saying, ‘We’re building up the justice system and the civilian police,’ and the other hand is saying, ‘We’re making your military really good at killing people,’” Lettieri told The Intercept. “I don’t know that it’s an incoherent foreign policy, but it’s certainly a slightly deceptive one.”

Last month, top officials from the U.S. and Mexico met to discuss replacing the Mérida Initiative, a $3.5 billion aid package that has been the public face of U.S.-Mexico security cooperation since 2007, with a new bilateral security framework. More than 300,000 people have been killed in Mexico since former President Felipe Calderón deployed the military in a stated war on drug trafficking in 2006. More than 100,000 others have disappeared. Security forces at all levels have a well-documented history of systemic human rights abuses.

In 2011, the U.S. and Mexico agreed to a reorganization of Mérida that would strengthen “law enforcement institutions, enhance criminal prosecutions and the rule of law, build public confidence in the justice sector, improve border security, promote greater respect for human rights, and prevent crime and violence.” The shift was seen among some close trackers of the U.S.-Mexico security relationship as a potential move away from the militarized drug war model that has fueled unprecedented levels of violence and instability in the country.

The database complicates that picture. Significant chunks of Mérida spending have indeed gone to civil society programs in Mexico in the past decade, largely through the U.S. Agency for International Development and the State Department; however, the government’s own records show that the Pentagon has taken the opposite track since 2011, doubling down on tactical training while moving away from human rights instruction. While the database captures the language proficiency and technical training courses one might expect to find in a binational security partnership, it also features extensive records of recent and large-scale training operations involving U.S. personnel in Mexico, including dozens of “unit-level pre-deployment training” missions involving upward of 140 marines at a time, combat shooting courses, martial arts courses, airborne parachute courses, tactical driving courses, asset interdiction courses, aerial warfare courses, and more.

“The top-line story that everybody’s giving is, all the Mérida spending is going to justice reform and it’s not just about shooting the baddies anymore,” Lettieri said. “I would say what the Pentagon is doing is ‘here’s how you shoot the baddies.’”

The information in the database, first organized by Security Force Monitor, a Columbia Law School project, shows that from 2007 to 2012, the U.S. provided tactical training to an average of 261 members of Mexican security forces annually. After 2012, that number jumped to 1,454. The Mexican marines were the primary beneficiary of the explosion in training, representing nearly 60 percent of the Pentagon’s students and receiving nearly half — $46.3 million — of the $101.2 million spent post-2011. From 2013 to 2019, while tactical training was surging, the Pentagon provided human rights training to just 27 students, only 12 of whom came from the Mexican military. Combined Pentagon and State Department funding on human rights training post-2012 came out to a mere $212,000.

Lettieri went into the project neither searching for nor expecting to find the post-2011 increase in tactical training, but as he continued to work with the data, the shift became clear. “When you look at it over time, it just jumps off the page that it’s tactical,” he said. It wasn’t just the marines, known in Mexico as SEMAR, receiving tactical training, he discovered. The army, known as SEDENA, also received extensive Pentagon support at the tactical level. The finding was significant because Washington has couched its embrace of the marines as allies in the drug war in Mexico in the perceived unreliability of the army as a trustworthy partner in matters of operational security and human rights. SEDENA has long been one of Mexico’s most powerful institutions; it has also been tied to many of the country’s worst state crimes, including the 2014 disappearance of 43 college students in the state of Guerrero.

The database provides just one glimpse into a much wider world of security exchanges between the U.S. and Mexico, Lettieri said, most of which is inaccessible to the public. It does not include, for example, information on the enormous array of arms Mexico purchases from the U.S. or where those arms ultimately end up, nor does it reveal anything about the extensive training and cooperation that occurs between state and local law enforcement agencies on the two sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. Thanks to the joint State Department and Pentagon report on foreign military training that’s delivered to Congress each year, “we have some ability to understand this section of U.S. interaction with Mexico,” Lettier said. Still, he added, “There’s a whole bunch of stuff we don’t know very much about.”

“That’s a key takeaway here,” he said. “There’s a whole bunch of money being spent, but we don’t have even this minimal kind of accountability.”

Two climate protesters disrupt coal export operations at the Port of Newcastle in Australia by abseiling off a machinery on Nov. 17. (Photo: Blockade Australia)

Two climate protesters disrupt coal export operations at the Port of Newcastle in Australia by abseiling off a machinery on Nov. 17. (Photo: Blockade Australia)

“My name is Hannah, and I am here abseiled off the world’s largest coal port,” 21-year-old Hannah Doole declared on a live-streamed video as she hovered high over massive piles of coal bound for export. “I’m here with my friend Zianna, and we’re stopping this coal terminal from loading all coal into ships and stopping all coal trains.”

Since officials met in Glasgow, Scotland, earlier this month to plot the planet’s path away from fossil fuels, Australia, the world’s second-biggest coal exporter, has showed little sign of changing course. Prime Minister Scott Morrison on Monday said the coal industry will be operating in the country for “decades to come.”

When he agreed last month to go carbon-neutral by 2050, the man who once brought a lump of coal into Parliament promised that his plan — which was short on details and long on speculative technology — would not crimp coal exports nor cost miners their jobs.

In the face of that apparent lack of urgency from government, protesters are increasingly taking matters into their own hands. A string of protests has disrupted the Port of Newcastle and surrounding railroads in the past two weeks, prompting police to establish a strike force to crack down on the high-profile stunts.

The protesters, from an activist group called Blockade Australia, plan to converge on Sydney, the commercial capital, in June next year, bringing the city to a halt.

“This is us responding to the climate crisis. This is humans trying to survive,” Doole said on Wednesday. “We are trying to induce the social tipping points, which will give us a chance at another generation,” she remarked on camera, pausing to laugh ironically, before adding: “What a wild thing to want.”

Despite the progress made at the COP26 climate summit, optimism about the agreement hangs on whether countries will actually deliver on the promises made in Glasgow. Coal production in China, the world’s largest consumer of coal, has surged to the highest levels in years as the country addresses power outages.

Matt Kean, the environment minister for New South Wales state, speaking on Sydney radio 2GB on Wednesday, said police need to “throw the book” at anti-coal activists, describing their dramatic stunts as “completely out of line.”

On Monday, another protester locked herself to a railway line leading to the port, preventing coal cars from entering. On Tuesday, two activists strapped themselves to another piece of coal-loading machinery. They hung in the air for several hours before being arrested.

Interfering with a railway or locomotive with the intention of causing a derailment can result in prison sentences up to 14 years, police said, while other possible charges carry jail terms of up to 25 years. A local police minister described the protests as “nothing short of economic vandalism.” (A spokeswoman for the Port of Newcastle said other operations at the port were continuing, beyond the rail lines and coal-loading facilities.)

Doole and Zianna Faud, 28, were arrested and taken to a local police station about 9 a.m. local time. The live-streamed video showed authorities approaching on a metal gangway above the protesters, who were suspended on ropes below, with a police officer appearing to read them their rights.

According to a spokeswoman for the activist group, Faud appeared before Newcastle magistrates court on Wednesday, where she faced charges of hindering the working of mining equipment, which carries a maximum sentence of seven years imprisonment, and entering enclosed lands. She pleaded guilty and was given community service and a roughly $1,090 fine, and ordered not to associate with her co-accused, Doole, for two years.

Doole and three other activists were refused bail and will be seen by the court tomorrow.

“We are running rings around the police and the push back shows that direct action is effective,” Faud said in a statement following her release.

In the video, Doole said she considered the dangers before the protest — imagining herself running across piles of coal with police helicopters in pursuit. Then, she thought back to the time, a couple of summers ago, when thousands of Australians fled from their homes as wildfires raged and skies turned blood red. She and her family hunkered down in their property as towns around them burned.

“Getting chased by a police helicopter, that’s not fun. … But you know what scares me more?” she said. “I just think back to that New Year’s Eve, when I thought I was going to die in a fire, caused by climate change. And that’s the barest glimpse of what’s going to happen.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611