Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The article below is satire. Andy Borowitz is an American comedian and New York Times-bestselling author who satirizes the news for his column, "The Borowitz Report."

The esteemed virologist said that, in calling Senator Roger Marshall, of Kansas, a moron, “I didn’t mean to offend. I was just trying to be accurate from a scientific standpoint.”

“As a scientist, I believe it’s important to use the correct nomenclature,” Fauci said. “You need to call a virus a virus, and a bacterium a bacterium. In this same way, I am confident that I was correct in calling Senator Marshall a moron.”

Fauci said that he does not use the word “moron” capriciously, but only after extensive scientific experimentation proves that it applies.

“Take Rand Paul, for example,” Fauci said. “I didn’t determine that he was a moron until after forty-five seconds of hearing him speak.”

President Joe Biden (R) and Vice President Kamala Harris (L) arrive for a visit to Ebenezer Baptist Church, in Atlanta, Georgia on January 11, 2022. (photo:Jim Watson/AFP)

President Joe Biden (R) and Vice President Kamala Harris (L) arrive for a visit to Ebenezer Baptist Church, in Atlanta, Georgia on January 11, 2022. (photo:Jim Watson/AFP)

Joe Biden made history by calling for changes to the filibuster for voting rights. Activists and civil rights groups aren’t having it.

That said, Bulldogs fans weren’t the only ones blowing off the White House visit, during which the president laid a wreath at the tomb of Martin Luther King Jr. and spoke at Morehouse College in Atlanta. A coalition of voting rights activists and civil rights leaders held a press conference Monday to declare that they would not attend the president’s speech, expressing displeasure at the half-measures Biden has taken to pass a voting rights bill.

Led by Black Voters Matter, the call with leaders from the Asian American Advocacy Fund, GALEO Impact Fund, New Georgia Project Action Fund, and others demanded deeds, not words.

“Take voting rights seriously,” said James Woodall, former president of the Georgia NAACP. “We’re asking for him to take this seriously and to outline an actual plan. They should be in D.C. taking a vote on this today,” he said. “Also, go Dawgs.”

Stacey Abrams, presumptive Democratic nominee for governor and a national leader on voting rights, also did not attend Biden’s appearance in Georgia, citing a scheduling conflict. She did not elaborate.

Biden used some of the strongest language yet to attack partisan intransigence in the U.S. Senate, likening those who vote to sustain a filibuster against voting rights legislation to secessionists and segregationists.

“History has never been kind to those who have sided with voter suppression over voters’ rights and will be less kind to those who sided with election subversion,” Biden said. “How do you want to be remembered? … Do you want to be on the side of Dr. King or George Wallace? Do you want to be on the side of John Lewis or Bull Connor? Do you want to be on the side of Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson Davis?”

Biden, for the first time, called on senators to set aside the filibuster in order to pass voting rights legislation in the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. He had previously avoided language about the filibuster, unwilling to wade into the issue publicly. “I’m tired of being quiet,” he said.

Civil rights leaders have pointed to unprecedented actions taken or threatened by legislators in the wake of Biden’s electoral victory in 2020 and the U.S. Senate wins by Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock in January 2021. The Republican-controlled Georgia legislature rewrote the state’s election laws in 2021 to enforce stricter rules for identification in absentee voting and to enable the state elections board to take over local elections boards, among other changes, passing the so-called Election Integrity Act.

S.B. 202 criminalizes “ballot harvesting” activities like pre-filling information on absentee ballot applications. It also requires absentee ballot drop-off boxes to be placed indoors and locked away from the public after business hours, making it much more difficult for people working 9-to-5 jobs to drop a ballot off directly instead of mailing it in.

The law also shortens the window for requesting an absentee ballot, giving voters less time to fill out and mail back a ballot. And the law criminalizes “line warming” activities such as providing food or drinks to people waiting to vote.

About 80 percent of voters cast ballots early in 2020, either by voting at an early-voting station or as an absentee voter. Doing so prevented long lines on Election Day and raised overall turnout.

The federal voting rights bills before the U.S. Senate would create a national baseline for voting access, preempting state laws. All states would have to allow at least two weeks of early voting, with polls open for at least 10 hours a day, including on weekends. Absentee ballots for mail-in voting would be required everywhere, with applications made online and standardized laws for signature matching and identification. Critically, it would prevent partisan election “reviews” like the Arizona audit and prevent election officials from being relieved of duty by partisan politicians.

Gov. Brian Kemp hit back at Biden immediately after the speech at Morehouse. “Ignoring facts and evidence, this administration has lied about Georgia’s Election Integrity Act from the very beginning in an effort to distract from their many failures and rally their base around a federal takeover of elections. But make no mistake, we will not back down,” Kemp tweeted. “The Election Integrity Act makes it easy to vote and hard to cheat with common-sense reforms. But Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, and Stacey Abrams have never let the truth get in the way of forcing their radical agenda on Georgians and Americans.”

Though Democrats narrowly won statewide races in 2020 and 2021, congressional redistricting in Georgia leaves the state with nine safe Republican seats to five safe Democratic seats. State Senate redistricting resulted in 33 districts that would tend to vote for Republicans and 23 that would tend to vote for Democrats. Lawsuits quickly followed Kemp’s signing of the redistricting legislation last year. Rep. Lucy McBath, whose 6th Congressional District gained tens of thousands of regular Republican voters, is now challenging Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux in the 7th District, composed primarily of Gwinnett County.

After Gwinnett — a suburban Atlanta county and long a Republican stronghold — flipped decisively to Democratic control in 2020, a state senator introduced legislation to radically reshape the county’s Board of Commissioners, expanding the commission to allow Republicans in the northern part of the county to compete again for a seat while weakening the role of the chair and changing school board elections to be nonpartisan races.

The senator, Clint Dixon, backed off the proposal after fierce local criticism, but he remains a co-sponsor of a plan to carve the wealthy and predominantly white Buckhead neighborhood out of the city of Atlanta. The Buckhead de-annexation bill comes over the objection of every legislator representing Buckhead and Atlanta, violating a Georgia rule about local support for local legislation.

Meanwhile, election law changes last year undid bipartisan local elections boards in rural Georgia, ceding political appointments to partisan county commissioners. One case — Lincoln County, north of Augusta — resulted in a new elections board proposing to close six of its seven polling locations. The board’s chair, Lilvender Bolton, said the move was necessary to manage Covid-19 concerns. But the rural county of about 8,000 residents — a third Black, a quarter in poverty — has no public transportation system, and the move would leave most of its voters more than 15 miles from the remaining poll.

Woodall and other local leaders say they are demanding federal action because these moves by Republicans are meant to whittle away at the margins of the vote in a state where the next election is likely to be decided by a percentage point. In the days of Justice Department preclearance, Republicans would not have risked these electoral changes.

“What we need is oversight,” Woodall said. “If we get these legislative proposals through, you will see a strengthening of democracy.”

'An increasingly well-armed populace has, the polls tell us, become ever more willing to imagine using violence.' (photo: iStock)

'An increasingly well-armed populace has, the polls tell us, become ever more willing to imagine using violence.' (photo: iStock)

In case you haven’t noticed — and I know you have — this country, as I wrote recently, is being (un)built before our very eyes. As a start, an increasingly well-armed populace has, the polls tell us, become ever more willing to imagine using violence to see its political aims met. I’m sure you won’t be surprised to find out, in the wake of the (first?) Trump era, that Republicans (especially his supporters) express that urge far more readily and strongly than Democrats. It’s what Stephen Marche, author of The Next Civil War, is calling “the politics of the gun” and it’s on the rise, along with armed militias.

Somehow, despite everything in election 2020, the bedrock American political system still worked. The question is: Will it ever again? In fact, if you want to catch the mood of the moment — a moment that none of us has experienced before, not in the Civil Rights era, not in the Vietnam War years — just consider this: only recently three retired generals wrote a Washington Post op-ed suggesting that parts of the military, in a future crisis like January 6th (only worse), might not even support or defend the elected government of the country, while fears of a future coup continue to rise.

Meanwhile, a year in which the Covid-19 pandemic took hundreds of thousands more American lives proved a remarkable boon for Republican politicians of just about every sort, most of whom have only fed the flames (with the lives of their supporters) and — no surprise here either — it also proved a boon for billionaires. (Elon Musk added $121 billion to his staggering wealth in 2021 alone.) In other words, we’re in a country and a world of startling inequality, growing desperation, surging illness and disease, and increasing disrepair. In the process, American democracy is distinctly in the crosshairs. And it’s this very world that seems to be feeding the flames of hell in this country that TomDispatch regular and co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign Liz Theoharis focuses on today, considering how even the Bible, at least the Christian nationalist version of it, has played its part in the dismembering of America. Tom

-Tom Engelhardt, TomDispatch

Which Way America?

Confronting Christian Nationalism in the Spirit of Desmond Tutu

The world lost a great moral leader this Christmas when Archbishop Desmond Tutu passed away at the age of 90. I had the honor of meeting him a few times as a child. I was raised by a family dedicated to doing the work of justice, grounded in the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and also sacred texts and traditions. We hosted the archbishop on several occasions when he visited Milwaukee — both before the end of apartheid and after South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was formed in 1996.

In the wake of one visit, he sent a small postcard that my mom framed and placed on the bookcase near our front door. Every morning before school I would grab my glasses resting on that same bookcase and catch a glimpse of the archbishop’s handwritten note. This wasn’t inadvertent on my mom’s part. It was meant as a visual reminder that, if I was to call myself a Christian — which I did, serving as a Sunday school teacher from the age of 13 and a deacon at 16 — my responsibility was to advocate for policies that welcomed immigrants, freed those held captive by racism and injustice, and lifted the load of poverty.

Given our present context, the timing of his death is all too resonant. Just over a year ago, the world watched as a mob besieged the U.S. Capitol, urged on by still-President Donald Trump and undergirded by decades of white racism and Christian nationalism. January 6th should have reminded us all that far from being a light to all nations, American democracy remains, at best, a remarkably fragile and unfinished project. On the first anniversary of that nightmare, the world is truly in need of moral leaders and defenders of democracy like Tutu.

The archbishop spent his life pointing to what prophets have decried through the ages, warning countries, especially those with much political and economic power, to stop strangling the voices of the poor. Indeed, the counsel of such prophets has always been the same: when injustice is on the rise, there are dark forces waiting to demean, defraud, and degrade human life. Such forces hurt the poor the most but impact everyone. And they often cloak themselves in religious rhetoric, even as they pursue political and economic ends that do anything but match our deepest religious values.

Democracy At Stake

“What has happened to us? It seems as if we have perverted our freedom, our rights into license, into being irresponsible. Perhaps we did not realize just how apartheid has damaged us, so that we seem to have lost our sense of right and wrong.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu

By now, lamenting the condition of American democracy comes almost automatically to many of us. Still, the full weight of our current crisis has yet to truly sink in. A year after the attempted insurrection of January 6, 2021, this nation has continued to experience a quieter, rolling coup, as state legislatures have passed the worst voter suppression laws in generations and redrawn political maps to allow politicians to pick whom their voters will be. The Brennan Center for Justice recently reported that more than 400 voter suppression laws were introduced in 49 states last year. Nineteen of those states passed more than 30 such laws, signaling the biggest attack on voting rights since just after the Civil War. And add to that another sobering reality — two presidential elections have now taken place without the full protections of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

This attack on democracy, if unmet, could alter the nature of American elections for at least a generation to come. And yet, so far, it’s been met with an anemic response from a painfully divided Congress and the Biden administration. Despite much talk about the need to reform democracy, Congress left for the holidays without restoring the Voting Rights Act or passing the For the People Act, which would protect the 55 million voters who live in states with new anti-voter laws that limit access to the ballot. If those bills don’t pass in January (or only a new proposal by Republican senators and Joe Manchin to narrowly reform the Electoral Count Act of 1887 is passed), it may prove to be too late to save our democracy as well as any hopes that the Democratic Party can win the 2022 midterm elections or the 2024 presidential race

Sadly, this nation has a strikingly bipartisan consensus to thank for such a moral abdication of responsibility. Democratic Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, in particular, have been vocal in refusing to overturn the filibuster to protect voting rights (though you know that, were the present Republicans in control of the Senate, they wouldn’t hesitate to do so for their own grim ends).

And of course, democracy isn’t the only thing that demands congressional action (as well as filibuster reform). Workers have not seen a raise in the minimum wage since 2009 and the majority of us have no paid sick leave in the worst public-health crisis in a century. Poor and low-income Americans, 140 million and growing, are desperately in need of the child tax credit and other anti-poverty and basic income programs at precisely the moment when they’re expiring and the pandemic is surging once again. And Manchin has already ensured weakened climate provisions in President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda that he claims he just can’t support (not yet anyway). If things proceed accordingly, in some distant future, sadly enough, geological records will be able to show the impact of our government’s unwillingness to act quickly or boldly enough to save humanity.

As Congress debates voting rights and investing in the people, it’s important to understand the dark forces that underlie the increasingly reactionary and authoritarian politics on the rise in this country. In his own time, Archbishop Tutu examined the system of white-imposed apartheid through the long lens of history to show how the Christianity of colonial empire had become a central spoke in the wheel of violence, theft, and racist domination in South Africa. He often summed up this dynamic through parables like this one: “When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible and we had the land. They said, ‘Let us pray.’ We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible and they had the land.”

In our own American context, they have the Bible and, as things are going, they may soon have the equivalent of “the land,” too. Just look carefully at our political landscape for evidence of the rising influence of white Christian nationalism. While it’s only one feature of the authoritarianism increasingly on vivid display in this country, it’s critical to understand, since it’s helped to mobilize a broad social base for Donald Trump and the Republicans. In the near future, through control over various levers of state and federal power, as well as key cultural and religious institutions, Christian nationalists could find themselves well positioned to shape the nation for a long time to come.

Confronting White Christian Nationalism

“There are very good Christians who are compassionate and caring. And there are very bad Christians. You can say that about Islam, about Hinduism, about any faith. That is why I was saying that it was not the faith per se but the adherent. People will use their religion to justify virtually anything.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Christian nationalism has influenced the course of American politics and policy since the founding of this country, while, in every era, moral movements have had to fight for the Bible and the terrain that goes with it. The January 6th assault on the Capitol, while only the latest expression of such old battlelines, demonstrated the threat of a modern form of Christian nationalism that has carefully built political power in government, the media, the academy, and the military over the past half-century. Today, the social forces committed to it are growing bolder and increasingly able to win mainstream support.

When I refer to “Christian nationalism,” I mean a social force that coalesces around a matrix of interlocking and interrelated values and beliefs. These include at least six key features, though the list that follows is anything but exhaustive:

* First, a highly exclusionary and regressive form of Christianity is the only true and valid religion.

* Second, white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity are “the natural order” of the world and must be upheld by public policy (even as Latino Protestants swell the ranks of American evangelicalism and women become important gate-keepers in communities gripped by Christian nationalism).

* Third, militarism and violence, rather than diplomacy and debate, are the correct ways for this country to exert power over other countries (as it is our God-given right to do).

* Fourth, scarcity is an economic reality of life and so we (Americans vs. the world, white people vs. people of color, natural-born citizens vs. immigrants) must compete fiercely and without pity for the greater portion of the resources available.

* Fifth, people already oppressed by systemic violence are actually to blame for the deep social and economic problems of the world — the poor for their poverty, LGBTQIA people for disease and social rupture, documented and undocumented immigrants for being “rapists and murderers” stealing “American” jobs, and so on.

* Sixth, the Bible is the source of moral authority on these (and other) social issues and should be used to justify an extremist agenda, no matter what may actually be contained in the Good Book.

Such ideas, by the way, didn’t just spring up overnight. This false narrative has been playing a significant, if not dominant, role in our politics and economics for decades. Since childhood — for an example from my own life — I’ve regularly heard people use the Bible to justify poverty and inequality. They quote passages like “the poor you will always have with you” to argue that poverty is inevitable and can never be ended. Never mind the irony that the Bible has been one of the only forms of the mass media — if you don’t mind my calling it that — which has had anything good to say about the poor (something those in power have tried to cover up since the days of slavery).

In many poor communities — rural, small town, and urban — churches are among the only lasting social institutions and so one of the most significant battlegrounds for deciding which moral values will shape our society, especially the lives of the needy. Indeed, churches are the first stop for many people struggling with poverty. The vast majority of food pantries and other emergency assistance programs are run out of them and much of the civic work going on in churches is motivated by varying interpretations of the Bible when it comes to poverty. These range from outright disdain and pity to charity to more proactive advocacy and activism for the poor.

Geographically, the battle for the Bible manifests itself most intensely in the Deep South, although hardly confined to that region, perhaps as a direct inheritance of theological fights dating back to slavery. For example, although there are more churches per capita than in any other state and high rates of attendance, Mississippi also has the highest child poverty rate, the least funding for education and social services for the needy, and ranks lowest in the country when it comes to overall health and wellness. It’s noteworthy that this area is known as both the “Bible Belt” and the “Poverty Belt.”

This is possible, in part, because the Bible has long been used as a tool of domination and division, while Christian theology has generally been politicized to identify poverty as a consequence of sin and individual failure. Thanks to the highly militarized rhetoric that goes with such a version of Christianity, adherents are also called upon to defend the “homeland,” even as their religious doctrine is used to justify violence against the most marginalized in society. These are the currents of white Christian nationalism that have been swelling and spreading for years across the country.

A moral movement from below

“We live in a moral universe. You know this. All of us know this instinctively. The perpetrators of injustice know this. This is a moral universe. Right and wrong do matter. Truth will out in the end. No matter what happens. No matter how many guns you use. No matter how many people get killed. It is an inexorable truth that freedom will prevail in the end, that injustice and repression and violence will not have the last word.” — Archbishop Desmond Tutu

In the Poor People’s Campaign (which I co-chair with Reverend William Barber II), we identify Christian nationalism as a key pillar of injustice in America that provides cover for a host of other ills, including systemic racism, poverty, climate change, and militarism. To combat it, we believe it’s necessary to build a multiracial moral movement that can speak directly to the needs and aspirations of poor and dispossessed Americans and fuse their many struggles into one.

This theory of change is drawn from our study of history. The most transformative American movements have always relied on generations of poor people, deeply affected by injustice, coming together across dividing lines of all kinds to articulate a new moral vision for the nation. This has also meant waging a concerted battle for the moral values of society, whether you’re talking about the pre-Civil War abolition movement, the Populist Movement of the late nineteenth century, labor upsurges of the 1930s and 1940s, or the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Today, to grasp the particular history and reality of America means recognizing the need for a new version of just such a movement to contend directly with the ideology and theology of Christian nationalism and offer an alternative that meets the material and spiritual needs of everyday people.

Archbishop Tutu was clear that injustice and heretical Christianity should never have the last word and that the world’s religious and faith traditions still have much to offer when it comes to building a sense of unity that’s in such short supply in a country apparently coming apart at the seams. At the moment, unfortunately, too many people, including liberals and progressives, sidestep any kind of religious and theological debate, leaving that to those they consider their adversaries, and focusing instead on matters of policy. But as Archbishop Tutu’s deeds and words have shown, to change our world and bring this nation to higher ground means being brave enough to wrestle with both the politics and the soul of the nation — which, in reality, are one and the same.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

'The interview was six years in the making. Trump and his team have repeatedly declined interviews with NPR until Tuesday.' (photo: Getty)

'The interview was six years in the making. Trump and his team have repeatedly declined interviews with NPR until Tuesday.' (photo: Getty)

"While there were some irregularities, there were none of the irregularities which would have risen to the point where they would have changed the vote outcome in a single state," Sen. Mike Rounds, R-S.D., said Sunday on ABC's This Week. "The election was fair, as fair as we have seen. We simply did not win the election, as Republicans, for the presidency. And if we simply look back and tell our people don't vote because there's cheating going on, then we're going to put ourselves in a huge disadvantage."

But Trump — who has endorsed dozens of candidates for the 2022 midterm elections and still holds by far the widest influence within the GOP — is trying hard not to let them move on.

"No, I think it's an advantage, because otherwise they're going to do it again in '22 and '24, and Rounds is wrong on that. Totally wrong," Trump told NPR in an interview Tuesday, referring to his false and debunked claims that the 2020 election was stolen.

The interview was six years in the making. Trump and his team have repeatedly declined interviews with NPR until Tuesday, when he called in from his home in Florida. It was scheduled for 15 minutes, but lasted just over nine.

After being pressed about his repeated lies about the 2020 presidential election, Trump abruptly ended the interview.

Trump's mixed messages on getting vaccinated

The interview began with the pandemic and vaccinations.

Trump, whose administration oversaw the development of the COVID-19 vaccines, recommended that people get vaccinated but said he's firmly against mandating that they do so.

"[T]he mandate is really hurting our country," Trump claimed, adding, "A lot of Americans aren't standing for it, and it's hurting our country."

He continued, "The vaccines, I recommend taking them, but I think that has to be an individual choice. I mean, it's got to be individual, but I recommend taking them."

The opposition to mandates is popular with Republicans, and the Supreme Court is currently weighing the Biden administration's vaccine-or-test mandate for large employers. But his comments come during the record omicron surge, as the unvaccinated are far more likely to be hospitalized or die from the disease, and as Republicans are far more likely to be unvaccinated.

Epidemiologists and health experts warn that if more people don't get vaccinated and the virus continues to morph, it could prolong the pandemic — and delay any sense of getting back to normal.

The former president said he wants to see therapeutics, used to treat the virus after someone is infected, produced and distributed more widely.

Trump's firm grip on the Republican Party, but tenuous grasp on reality

Trump is not just any former president.

Even many members of his own party have blamed him for inciting the deadly Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, but since then Trump has only tightened his grip on the GOP.

He remains one of the most popular figures in the Republican Party and is considered the front-runner for the 2024 presidential nomination, if he decides to run again.

When he ran in 2016, Trump was seen as having a shoestring campaign, fighting an uphill battle with few allies among Republican elected leaders.

Today, it's a different story. Trump's political organization has become a juggernaut. Not only are most Republican elected leaders falling in line, but he has also installed allies controlling many levers of political power across the country. In state after state, Trump allies are running local Republican parties, serving as state representatives and in charge of political action committees.

It's a political army ready to be mobilized at his beck and call. What he says — what his message is to them — matters because they follow.

To secure his power, he will do whatever he can to cast aside those who don't show fealty. That includes threats, bullying and intimidation, like badgering and name-calling.

Referring to South Dakota's Rounds in a statement after he appeared on ABC, for example, Trump said Rounds "just went woke," called him a "jerk," "weak," "ineffective" and questioned whether he was "crazy or just stupid."

He also called him a RINO, an acronym for an insult some conservatives reserve for more moderate Republicans they disagree with — Republicans in name only.

In the interview with NPR, he partially blamed Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell for Rounds and other senators feeling as though they can speak out and say — correctly — that Trump lost the election.

"Because Mitch McConnell is a loser," Trump said.

Trump has called McConnell worse — and all because the Kentucky Republican has crossed Trump, blaming him for the insurrection on Jan. 6 and saying President Biden won, even if McConnell doesn't do so forcefully every day.

It's par for the course for Trump, who has demanded unflinching loyalty — and who chafes at truths he disagrees with, especially about him losing.

Won't accept losing an election he lost

Many Republicans prefer to focus on Biden as this year's congressional elections approach. Trump is pressing candidates in a different direction.

Josh Mandel, a pro-Trump Republican from Ohio, launched his campaign for U.S. Senate just weeks after Trump supporters attacked the U.S. Capitol last year.

"I think over time we're gonna see studies come out that [show] evidence of widespread fraud," Mandel, a former state treasurer who is angling for Trump's endorsement, told WKYC-TV.

In the year since Mandel made that prediction, the opposite has happened.

Even more evidence shows a free and fair election.

In one disputed state, Arizona, Trump allies held a widely criticized review of millions of ballots, but even Doug Logan, who led Cyber Ninjas, the firm that ran the review, couldn't find much.

"The ballots that were provided to us to count in the Coliseum very accurately correlate with the official canvass numbers," Logan said.

As he does with any information or person he doesn't like or disagrees with, Trump dismissed the findings in the NPR interview.

"Lying or delusional"

In the interview, Trump repeated a number of false claims about voting systems in the U.S., including that the discredited GOP-led ballot review in Arizona showed evidence of malfeasance — despite the fact that it also reaffirmed Biden's victory.

Republican officials in Maricopa County, however, debunked the characterizations of Trump and his allies in a 93-page rebuttal issued last week.

"The people who have spent the last year proclaiming our free and fair elections are rigged are lying or delusional," said Bill Gates, the GOP chair of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors.

Asked why even Republicans in the state accepted the findings, Trump reverted to an old attack.

"Because they're RINOs," he said, "and frankly, a lot of people are questioning that."

Tammy Patrick, a former Maricopa County election official and now an elections expert at Democracy Fund, was presented by NPR with a number of Trump's claims about voting and noted that in the 14 months since the election, no proof of any of his claims has come to light.

"It hasn't been presented in any of the courts. It hasn't been surfaced in any official election audits, not by the Department of Justice, not by the FBI," Patrick said. "Allegations of fraud hinge upon being able to produce actual instances of fraud — not merely thoughts, feelings or beliefs about it."

To Republicans who know how elections work, the election has always been obvious.

"The facts show that it was President Biden who won fair and square," said Trey Grayson, who used to run elections as the Republican secretary of state in Kentucky. "It wasn't rigged."

He's thinking about those Republican T-shirts that said, "F*** your feelings."

"And here we are looking at the 2020 election," Grayson said, "and we are the ones who are basing it on feelings, not on facts, not on the law."

The Pennsylvania example

Most Republican voters now say they feel the election was stolen, according to surveys. That gives Trump leverage with Republican candidates who want to win primaries this year.

In Pennsylvania, numerous Republicans are running for governor and senator. They've made lots of moves to prove their fealty to the former president. One candidate for governor is Bill McSwain, who happened to be a U.S. attorney during the 2020 election.

"Bill McSwain left office without announcing any investigations or outcome of investigations for the 2020 election in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania," said Chris Brennan of the Philadelphia Inquirer, who has covered his story.

But then McSwain prepared to run for office. Last summer, he produced a letter for Trump, appealing for his support — and implying that he was blocked somehow from investigating unspecified claims of fraud.

"But it doesn't actually say that," Brennan said. "So even he, when you carefully read it, does not claim that he was blocked from investigating fraud."

Trump nonetheless made the letter public and gave his own interpretation at multiple rallies.

"We have a U.S. attorney in Philadelphia that says he wasn't allowed to go and check," Trump said at a rally in Florida.

Grayson has watched similar stories unfold in multiple states.

"I think he's been really active in moving 2022 candidates toward his point of view," Grayson said. "The way I look at it is, I can't imagine that the party on its own would be pushing this narrative if he weren't pushing it."

Repeatedly in the interview, Trump presses his party to adhere to his point of view and false claims, and he adapts his arguments to account for more and more proof that he lost. That's a typical strategy among purveyors of disinformation and misinformation.

Trump did correctly note in the interview that he received more votes than any sitting president ever. But his broader point that that is somehow evidence that he won in 2020 is nonsensical, said Patrick, seeing as the election saw record turnout.

"Each election compares those candidates facing off in that election — it doesn't matter how the numbers compare to the last election," Patrick said. "It doesn't matter how many points a team scored the last game or how many times Alabama has won the national championship. What matters is who has the most points or votes at the end of the game."

For the record, the University of Georgia won the college football national championship Monday, defeating Alabama, 33-18. And Biden got 7 million more votes than Trump in the popular vote in 2020 and got 306 electoral votes to Trump's 232.

Repeated losses in the independent judiciary

Trump doesn't have a case of widespread fraud.

He and his lawyers tried to prove that he did — and they failed. Many judges, including some appointed by him, ruled that way in dozens of cases.

Here's a section of the interview on this:

NPR'S STEVE INSKEEP: Let me read you some short quotes. The first is by one of the judges, one of the 10 judges you appointed, who ruled on this. And there were many judges, but 10 who you appointed. Brett Ludwig, U.S. District Court in Wisconsin, who was nominated by you in 2020. He's on the bench and he says, quote, "This court allowed the plaintiff the chance to make his case, and he has lost on the merits."

Another quote, Kory Langhofer, your own campaign attorney in Arizona, Nov. 12, 2020, quote, "We are not alleging fraud in this lawsuit. We are not alleging anyone stealing the election." And also Rudy Giuliani, your lawyer, Nov. 18, 2020, in Pennsylvania, quote, "This is not a fraud case." Your own lawyers had no evidence of fraud. They said in court they had no evidence of fraud. And the judges ruled against you every time on the merits.

TRUMP: It was too early to ask for fraud and to talk about fraud. Rudy said that, because of the fact it was very early with the — because that was obviously at a very, very — that was a long time ago. The things that have found out have more than bore out what people thought and what people felt and what people found.

When you look at Langhofer, I disagree with him as an attorney. I did not think he was a good attorney to hire. I don't know what his game is, but I will just say this: You look at the findings. You look at the number of votes. Go into Detroit and just ask yourself, is it true that there are more votes than there are voters? Look at Pennsylvania. Look at Philadelphia. Is it true that there were far more votes than there were voters?

INSKEEP: It is not true that there were far more votes than voters. There was an early count. I've noticed you've talked about this in rallies and you've said, reportedly, this is true. I think even you know that that was an early report that was corrected later.

TRUMP: Well, you take a look at it. You take a look at Detroit. In fact, they even had a hard time getting people to sign off on it because it was so out of balance. They called it out of balance. So you take a look at it. You know the real truth, Steve, and this election was a rigged election.

When pressed, it was excuse after excuse — it was "too early" to claim fraud, his attorney was no good, things just seem suspicious.

But it all comes back to the same place: He has no evidence of widespread fraud that caused him to lose the election.

The tone of the interview changed. Trump then hurried off the phone as he was starting to be asked about the attack on the Capitol, inspired by election lies.

A judge is considering whether Trump can be held liable for his actions in court.

If he can be, then Trump or his lawyers would someday have to answer the questions he didn't answer before he cut short his conversation with NPR.

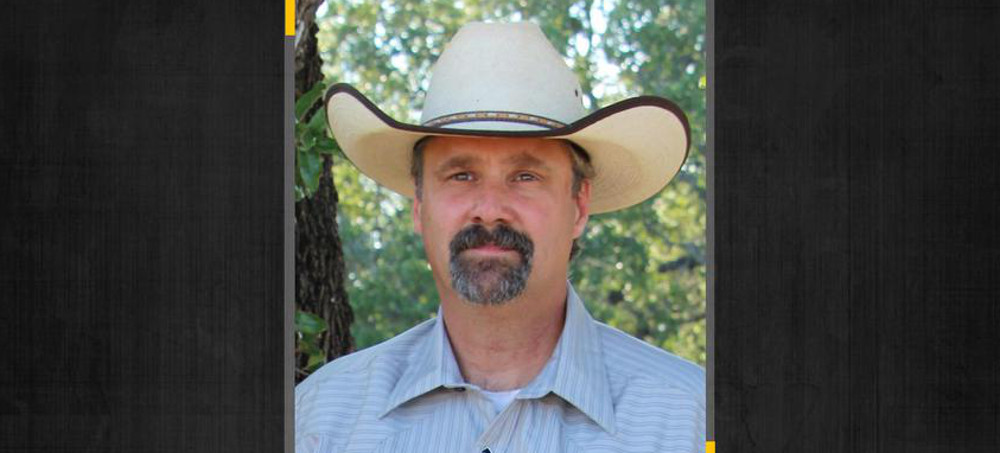

Real County Sheriff Nathan Johnson. (photo: Real County)

Real County Sheriff Nathan Johnson. (photo: Real County)

Search warrants show that Real County Sheriff Nathan Johnson is under scrutiny by state investigators, accused of illegally confiscating cash and a pickup truck from immigrants stopped by his deputies.

Last month, investigators with the Texas Rangers and the Texas Attorney General’s Office raided four Real County Sheriff’s Office locations as part of an investigation into Sheriff Nathan Johnson, according to search warrants obtained this week by The Texas Tribune. The investigating Texas Ranger said Johnson admitted to regularly seizing money from undocumented immigrants during traffic stops, even if they were not accused of any state crime, before handing them over to United States Border Patrol agents.

One sheriff's deputy told investigators that “seizing currency from undocumented immigrants and the driver has been standard operating procedure for as long as he has been employed by the Real County Sheriff’s Office,” Texas Ranger Ricardo Guajardo wrote in the warrant requests.

Guajardo accused Johnson of felony-level theft by a public servant and abuse of official capacity, alleging the sheriff’s cash and vehicle seizures were in violation of the state’s relatively lenient civil asset forfeiture laws.

Johnson did not respond to specific questions Monday, stating that his and county attorneys are reviewing the newly released affidavit. In November, he told investigators money and cars are sometimes held as evidence for potential criminal cases, according to Guajardo. After his offices were raided in December, Johnson said in a Facebook post that he didn’t know what prompted the investigation, had not been arrested and would continue to serve his constituents.

“Especially in the last year, I have taken a strong stand against human smuggling, drug smuggling, and illegal alien traffic in our community and will continue to do so,” Johnson wrote.

It’s unclear if any charges have been or will be filed against Johnson. The attorney general’s office did not respond to questions Monday, and the Texas Department of Public Safety said it had no information to release.

The search warrants were carried out at two sheriff’s offices and two impound lots last month to seek evidence investigators believe will bolster their case against Johnson. The warrants include computers, cellphones, seized evidence regarding money or vehicles, financial statements and other data going back to 2017, when Johnson took office.

The investigation into the Republican sheriff is underway as a political firestorm rages over immigration policy, with the state and country facing record-high levels of U.S.-Mexico border crossings. Blaming the rise on President Joe Biden, Gov. Greg Abbott has sent thousands of state police and military personnel to “arrest and jail” people suspected of having crossed the border illegally on state criminal charges.

Real County is home to about 3,400 residents and is near but not on the border, sitting about 100 miles northeast of Del Rio, the epicenter of migrant crossings in Texas last year and a focus of Abbott’s border security operation.

In Texas, police can take cash and property believed to be related to criminal activity, even if the person involved is never charged with a crime. Such seizures, however, require an already controversial forfeiture process during which prosecutors must file a civil lawsuit against the property for police to keep it.

Johnson, however, told Guajardo in November that he did not initiate such proceedings, the warrant stated. Instead, in two instances when Real County was assisted by neighboring law enforcement agencies, the sheriff classified seized property as abandoned or labeled it as evidence for potential charges, according to the warrant.

Aside from potential criminal charges, avoiding the state’s forfeiture laws creates constitutional concerns and bad optics, according to Arif Panju, the managing attorney for the Texas office of the Institute for Justice, a legal organization against civil asset forfeiture.

“If you’re doing it outside the judicial process, you can see the perverse incentive that would exist,” Panju said. “If you could seize these things, not go to a court, seize it unilaterally and then keep it in your budget … that is again policing for profit with zero oversight.”

Guajardo began investigating Johnson in October after discussions with the attorney general’s office, the warrant said, focusing on two traffic stops.

Body camera footage of a May 2021 traffic stop taken by a sheriff's deputy from neighboring Edwards County showed Johnson directing his deputies to seize money and a truck from undocumented immigrants. The seized money was to be filed as abandoned cash and deposited into the Real County general fund, Guajardo detailed. Johnson said he would try to find the truck’s registered owners, but after 30 days the vehicle would also be considered abandoned.

During another traffic stop in October, more than $2,700 in cash taken from three immigrants’ wallets was said to be marked as evidence while waiting to see if human smuggling charges against the driver would stick. The other two men were referred to Border Patrol, where they asked what had happened to the money in their wallets. Guajardo said the seizing deputy couldn’t say under what authority the money was taken, just that Johnson told him to take it.

When Guajardo questioned Johnson about the October seizure, the sheriff said no legal forfeiture paperwork was filed in money seizures, but that money and vehicles were being held as evidence due to trafficking crimes. Days after the traffic stop, Johnson said he consulted with the local district attorney and was told he needed to initiate forfeiture proceedings after property seizures.

Before then, Guajardo wrote that Johnson said “his office was seizing all currency to include currency in possession of undocumented immigrants before being released to the custody of the United States Border Patrol.”

'Thanks to the current government's policies to strengthen the real economy, Argentina has been enjoying a remarkable recovery from COVID-19.' (photo: Getty)

'Thanks to the current government's policies to strengthen the real economy, Argentina has been enjoying a remarkable recovery from COVID-19.' (photo: Getty)

Unlike the United States, which could spend one-quarter of its GDP protecting its economy from the COVID-19 fallout, Argentina entered the pandemic with the deck stacked against it. Yet, thanks to the current government’s policies to strengthen the real economy, the country has been enjoying a remarkable recovery.

When countries suffer such acute pain, officeholders tend to receive more blame than they deserve. Often, the result is a more fractious politics that makes addressing real problems even harder. But even with the deck stacked against them, some countries have managed to deliver strong recoveries. Consider Argentina, which was already in a recession when the pandemic hit, owing to a large extent to former President Mauricio Macri’s economic mismanagement. Everyone had seen this movie before. A right-wing, business-friendly government had won the confidence of international financial markets, which duly poured in money. But the administration’s policies turned out to be more ideological than pragmatic, serving the rich rather than ordinary citizens. When those policies inevitably failed, Argentinians elected a center-left government that would spend most of its energy cleaning up the mess, rather than pursuing its own agenda. The resulting disappointment would then set the stage for the election of another right-wing government. Regrettably, a pattern repeated over and over. But there are important differences in the current cycle. The Macri government, elected in 2015, inherited relatively little foreign debt, owing to the restructuring that had already occurred. International financial markets were thus was even more enthusiastic than usual, lending the government tens of billions of dollars despite the absence of a credible economic program. Then, when things went awry – as many observers had anticipated – the International Monetary Fund stepped in with its largest-ever rescue package: a $57 billion program, of which $44 billion was quickly dispersed in what many saw as a naked attempt by the IMF, under pressure from US President Donald Trump’s administration, to sustain a right-wing government.

What followed is typical of such political loans (as I detailed in my 2002 book, Globalization and Its Discontents). Domestic and foreign financiers were given time to take their money out of the country, leaving Argentinian taxpayers holding the bag. Once again, the country was heavily indebted with nothing to show for it. And, once again, the IMF “program” failed, plunging the economy into a deep downturn, and a new government was elected. Fortunately, the IMF now recognizes that its program failed to achieve its stated economic objectives. The Fund’s “Ex-Post Evaluation” places a significant portion of the blame on Macri’s government, whose “redlines on certain policies may have ruled out potentially critical measures for the program. Among those measures were a debt operation and use of capital flow management measures.” The IMF’s usual apologists will attribute the program’s failure to a lack of communication or clumsy implementation. But better communication is no fix for poor program design. The market understood this, even if the US Treasury Department and some in the IMF did not. Given the mess that Argentinian President Alberto Fernández’s government inherited in late 2019, it appears to have achieved an economic miracle. From the third quarter of 2020 to the third quarter of 2021, GDP growth reached 11.9%, and is now estimated to have been 10% for 2021 – almost twice the forecast for the US – while employment and investment have recovered to levels above those when Fernández took office. The country’s public finances have also improved, even with a countercyclical recovery policy, owing to the strong economic growth, higher and more progressive tax rates on wealth and corporate income, and the debt restructuring of 2020. There also has been significant growth in exports – not just in terms of value but also in volume – following the implementation of development policies designed to foster growth in the tradable sector. These include reforms to credit policies; a reduction in export duties to zero in value-added sectors, coupled with higher rates on primary commodities; and investments in public infrastructure and research and development (the kinds of policies that Bruce Greenwald and I advocate in our book Creating a Learning Society). Despite this significant progress in the real economy, the financial media has chosen to focus wholly on issues such as country risk and the exchange-rate gap. But those problems are hardly surprising. Financial markets are looking at the mountain of IMF-furnished debt coming due. Given the enormous size of the loan that needs to be refinanced, an agreement that merely extends the amortization timeline from 4.5 to ten years is hardly sufficient to alleviate Argentina’s debt worries. Moreover, Argentina is still experiencing the effects of the speculative portfolio capital that poured in during Macri’s presidency. Much of this was trapped by that government’s capital controls, resulting in constant pressure on the parallel exchange rate.

Cleaning up the previous government’s financial mess will take years. The next big challenge is to reach an agreement with the IMF over the Macri-era debt. The Fernández government has signaled that it is open to any program that does not undermine economic recovery and increase poverty. Though everyone should know by now that austerity is counterproductive, some influential IMF member states may still push for it. The irony is that the same countries that always insist on the need for “confidence” could undermine confidence in Argentina’s recovery. Will they be willing to go along with a program that does not entail austerity? In a world still battling COVID-19, no democratic government can or should accept such conditions. Over the past few years, the IMF has gained new respect with its effective responses to global crises, from the pandemic and climate change to inequality and debt. Were it to reverse course with old-style austerity demands on Argentina, the consequences for the Fund itself would be severe, including other countries’ diminished willingness to engage with it. That, in turn, could threaten global financial and political stability. In the end, everyone would lose.

People enjoy the day on the coast along Havana's Malecon on July 3, 2020. (photo: Getty)

People enjoy the day on the coast along Havana's Malecon on July 3, 2020. (photo: Getty)

Cuba, a small island besieged by the United States, is taking concrete measures to reorient its economy in the fight against climate change. It’s an example that the whole world should take seriously.

But unlike in many countries, where climate action is always something promised for the future, in Cuba, serious action is being taken now. Between 2006 and 2020, several international reports identified the island nation as the world leader in sustainable development. And in spring 2017, the Cuban government approved Tarea Vida (“Life Task”), its long-term plan to confront climate change. The plan identifies at-risk populations and regions, formulating a hierarchy of “strategic areas” and “tasks” in which climate scientists, ecologists, and social scientists work alongside local communities, specialists, and authorities to respond to specific threats. To be progressively implemented in stages from 2017 to the year 2100, Tarea Vida also incorporates mitigation actions like the shift to renewable energy sources and legal enforcement of environmental protections.

In summer 2021, I went to Cuba to learn about Tarea Vida and produce a documentary to be shown during the COP26 international climate change conference in Glasgow. My visit coincided with a surge in COVID-19 cases on the island, and the public health measures imposed to reduce contagion, as well as the July 11 protests. Despite these conditions, we moved freely throughout Havana interviewing climate and social scientists, policymakers, leaders of Cuba’s Civil Defense, people in the street, and communities vulnerable to climate change.

On Havana’s Santa Fe coastline, I came across a fisherman living with his family among abandoned buildings. He described how, when the water floods the ground floor, their home is like a ship at sea. Despite the threat, they intend to stay: “This house can be reduced to one block; I’m not moving,” he said. The first “task” in Tarea Vida includes protecting these vulnerable communities through relocating households or entire settlements. The Cuban state pays for relocation, including the construction of new homes, social services, and public infrastructure. However, it is not mandatory, meaning that these residents must be involved in the decision-making and construction process. There are also examples of communities proposing their own adaptation strategies, enabling them to remain on the coast.

Tarea Vida is the culmination of decades of environmental protection regulation, the promotion of sustainable development and scientific investigation. Within Cuba, it is conceived of as a new basis for development, part of a cultural change and a broader process of decentralization of responsibilities, powers, and budgets to local communities. Here, we see that environmental considerations are integral to Cuba’s national development strategy, rather than just a side concern. Tarea Vida is also driven by necessity; climate change is already impacting life on the island. “Today in Cuba, the country’s climate is undergoing a complete transition from a humid tropical climate toward a subhumid climate, in which the patterns of rain, availability of water, soil conditions, and temperatures will be different,” explains Orlando Rey Santos, a ministerial adviser who led Cuba’s delegation to COP26. “We will have to feed ourselves differently, build differently, dress differently. It is very complex.”

“From Rainforest to Cane Field”

Centuries of colonial and then imperialist exploitation and the imposition of the agro-export model led to chronic deforestation and soil erosion in Cuba. The expansion of the sugar industry reduced the island’s forest cover from 95 percent pre-colonization to 14 percent at the moment of the revolution in 1959, turning Cuba “from rainforest to cane field,” as Cuban environmental historian Reinaldo Funes Monzote titled his award-winning book. Redressing this historical legacy became part of the project for revolutionary transformation post-1959, which sought to break the chains of underdevelopment.

Despite the revolutionaries’ early aspirations, Cuba continued to be dominated by the sugar industry through its trade with the Soviet bloc. Productive activities that contributed to pollution and erosion continued, including on account of Cuba’s embrace of the so-called “Green Revolution” of mechanized agriculture — an approach adopted in many developing countries to increase agricultural output.

However, the detrimental effects were gradually recognized and incrementally redressed, particularly from the 1990s. There has been an increasing concern with protecting the natural endowments of the Cuban archipelago, which boasts extraordinary biodiversity and coastal resources of global importance. The environmental agenda was backed up by Cuba’s scientific and institutional capacity and facilitated by its political-economic framework.

In his work on Cuban environmental law, Oliver A. Houck observed that: “post-revolutionary Cuban law promoted public and collective values from the start. Environmental laws fit easily into this framework.” As early as May 1959, the Agrarian Reform Law gave the state responsibility for protecting natural areas, initiated reforestation programs, and excluded forest reserves from distribution to agricultural collectives. Cuba’s socialist system prioritizes human welfare, and the social character of property facilitates environmental protection and the rational use of natural resources.

This process was not automatic — rather, it required geographers and environmentalists to drive the post-1959 government’s environmental agenda. Outstanding among them was Antonio Núñez Jiménez, a socialist and professor of geography in the 1950s. He served as a captain in Che Guevara’s Rebel Army column and headed the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, among other roles. Influenced by Núñez Jiménez, Fidel Castro also propelled Cuba’s environmental movement. Tirso W. Sáenz, who worked closely with Guevara in the early 1960s and headed Cuba’s first environmental commission from 1976 told me, “Fidel was the main driving force for the incorporation of environmental concerns into Cuban policy.” The Cuban Communist Party has also openly endorsed environmental protection and sustainable growth, which, according to Houck, “provides significant legitimacy to environmental programs.”

In 1976, Cuba was among the first countries in the world to include environmental issues in its constitution, and the National Commission for the Protection of the Environment and the Rational Use of Natural Resources was set up. That was eleven years before the UN’s Brundtland Report introduced the notion of “sustainable development” to the world. In the following decades, studies and projects were undertaken and environmental regulations introduced to protect fauna and flora. In 1992, Fidel Castro delivered an uncharacteristically short and appropriately alarming speech at the Earth Summit in Brazil. He blamed exploitative and unequal international relations, resulting from colonialism and imperialism, for the rapacious environmental destruction fueled by capitalist consumer societies, threatening the extinction of mankind.

That year, a commitment to sustainable development was introduced to the Cuban constitution. Scientific investigations into the impact of climate change in Cuba were initiated. In 1994, a new Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment (CITMA) was established. It devised a National Environment Strategy, which was adopted in 1997, the same year Law 81 was approved in the National Assembly. Laura Rivalta, a University of Havana law graduate specializing in environmental regulations, explains that this law gave CITMA broad powers to “control, direct, and execute environmental policy” while putting “boundaries and limits” on the activities of foreign companies operating in Cuba. “The new Cuban Constitution approved in 2019 establishes the right to enjoy a healthy and balanced environment as a human right,” she adds.

Not Beholden to Profit

Four factors underpin Cuba’s capacity to develop such an ambitious state plan. First, Cuba’s state-dominated, centrally planned economy helps the government to mobilize resources and direct national strategy without having to incentivize private profit — unlike other countries that rely on “market solutions” for climate change.

Second, Tarea Vida builds on Cuba’s world-leading record of anticipating and responding to risks and natural disasters. This has already been frequently demonstrated in its response to hurricanes and, since March 2020, in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Third is Cuba’s Civil Defense system, established following the devastating Hurricane Flora of 1963. During my visit to the national command, Lieutenant Colonel Gloria Gelis Martínez described their “operational and technical procedures for early warning of the impact of extreme meteorological events. We have surveillance zones and maximum alert zones where we monitor the approach of an event and its impact.” A National Defense Council coordinates this system and is reproduced at provincial, municipal, and neighborhood levels throughout the country. Meteorologist Eduardo Planos explained:

At the local level, risk-study centers focus on the specific phenomenon, and the neighborhood is organized. The social organizations in each area take preventative measures. Local governments set up local defense councils, which organize how the system works, distribute basic foodstuff so people don’t go without, and check electrical installations and the evacuation plan.

Fourth is Cuba’s capacity to collect and analyze local data. Rey Santos highlights what this means practically:

Studies indicate that the average rise in sea level will be around 29 centimeters by 2050. However, we have carried out the same analysis for 66 points of the national territory, as there are differences depending on local conditions. To carry out such an analysis, taking IPCC data on global sea level rises to each location in Cuba can only be done if you are backed up by strong science.

Tarea Vida Is Working

The 2017-2020 “short-term” results of Tarea Vida are currently under evaluation. This period coincided with Donald Trump’s presidency and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Trump administration severely tightened US sanctions against Cuba, further obstructing its access to resources and finances. The pandemic further battered the economy through the loss of tourism revenues. Nonetheless, there have been tangible achievements: a massive 11 percent of the most vulnerable coastal homes have been relocated; coral farms have been set up; 380 km² of mangroves have been recovered, serving as a natural coastal defense; and 1 billion pesos were invested in the country’s hydraulic program. Reforestation programs since 1959 have raised forest cover to 30 percent.

What can other Global South countries learn from this? The Copenhagen Accord of December 2009 pledged climate funding to the developing world, rising to USD$100 billion annually by 2020. But this commitment hasn’t been met. “They count funding twice, count money promised but not delivered, count as donations money that’s given to a country that is actually returned because it is a loan,” complains Rey Santos. “International financing is totally weighted in favor of mitigation, which is a business. There is much less money for adaptation. Funding is extremely low for small island developing states [SIDS], which are among the most vulnerable groups.” He describes “beautiful” climate change plans produced to comply with international commitments, then filed away. In contrast, “in Cuba, Tarea Vida is a living process, a product of the system that generated it.”

Cuba’s access to international finance is more limited than other countries due to the US blockade, which prevents it from accessing multilateral development banks. It instead depends on bilateral cooperation and the United Nations for finance and cooperation. US pressure and sanctions don’t just hit Cuba directly, they are also targeted against its potential partners in third countries. For example, the United States prohibits the sale to Cuba of equipment in which 10 percent or more of the components are made by US companies.

The Cuban approach to climate adaptation and mitigation offers an alternative to the globally dominant paradigms based on the private sector or public-private partnerships. It has increasing relevance to tourism-dependent Caribbean SIDS (Small Island Developing States) and other Global South countries emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic with levels of indebtedness that will obstruct future access to international financing. This will bring them closer to the financial and resource restraints that Cuba has confronted for decades due to US sanctions. Tarea Vida relies on low-cost domestic solutions, not external funding.

Rey Santos cautions against trying to advance a climate agenda without addressing structural problems like extreme poverty and deep social and economic inequality. He says it is impossible to convert the world’s energy matrix from fossil fuels to renewable energies without reducing consumption levels when there are insufficient resources to produce the solar panels and wind turbines required or insufficient space to host them. “If you automatically made all transportation electric tomorrow, you would have the same problems of congestion, parking, highways, and heavy consumption of steel and cement,” he points out. “There must be a change in the way of life, in our aspirations. This is part of the debate about socialism, part of Che Guevara’s ideas on the ‘new man.’ Without forming that new human, it is very difficult to confront the climate issue.” A plan like Tarea Vida requires a vision that is not directed toward profit or self-interest. “It must be premised on social equity and rejecting inequality. A plan of this nature requires a different social system, and that is socialism,” he concludes.

Clearly, this political economy framework doesn’t exist in other SIDS. But with the COP26 summit in Glasgow again showing governments’ lack of determination to act on the climate and their refusal to encroach on private interests, the Cuban approach of using environmental science, natural solutions, and community participation can provide examples of best practice to those who do want to confront climate disaster.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611