She's now in private school and misses public school. But Steenman is keeping her out not because of masks, but because of lesson plans she says make students feel bad about their race.

"The school bus goes right in front of my house and my kid is dying to ride it," she told CNN. "But not until I have deemed that the curriculum is safe and will do no harm."

Steenman is counting on a new Tennessee law to force schools to end that curriculum -- and ban at least one book in the elementary school library written from the perspective of Mexican Americans.

The former fighter pilot leads a chapter of Moms For Liberty in this wealthy, Republican-leaning suburb of Nashville.

She says her group has ballooned in size since April, from less than 20 parents meeting at her house to more than 3,000 connecting on Facebook. The chapter has grabbed headlines for belligerent protests at school board meetings. They have attacked a high school LGBTQ

pride float -- one tweet wondered if students passing out pride literature were doing "

recruitment." And another meeting featured a tirade by a Moms For Liberty member against a children's book about the lives of

seahorses, which she said was too sexual.

But the group's main concern is how American history is taught in school, particularly to younger kids.

In a multi-page complaint to the state department of education filed this summer, Moms For Liberty says the Williamson County Schools curriculum violates state law because it includes "anti-American, anti-White and anti-Mexican teaching."

In May, Gov. Bill Lee signed HB 580, a law aimed at banning so-called critical race theory from schools. Educators argue that critical race theory is not taught or included in the K-12 curriculum and is usually an elective class in college or law school.

Section 51, part 6 of the Tennessee law makes lesson plans illegal if students "feel discomfort, guilt, or anguish."

Steenman says the Williamson County curriculum makes students feel bad about their race, meaning the law should invalidate it.

The Tennessee Department of Education declined a request for comment from CNN on the complaint.

The books at the center of the debate

With a pile of kid's books marked with highlighters and flagged with Post-It notes spread out on her dining room table, Steenman told CNN the books in the school and the way they're taught leave children of White parents feeling guilty.

"A letter was brought to my attention that was written by the parents of a biracial second-grade boy. And he's half Thai, half White -- has as a White father, a Thai mother," she said. "And then he is suddenly ashamed of his White half, his White father. He only wants to identify as Thai and he does not want to be an American."

Steenman doesn't like a lot of the curriculum at Williamson County Schools. But four books in the second-grade lessons plans are the target of her campaign.

Three of the books, about the civil rights movement, are problematic for the way they're taught, she says. One is a

children's book about the March on Washington written for young readers.

Two tell the story of Ruby Bridges, a 6-year-old who integrated an elementary school in New Orleans in 1960. "Ruby Bridges Goes To School," written for elementary school students by Bridges herself, is fine for kids to read, Steenman says. But she says teachers should not be allowed to lead discussions of the pictures in the book -- one of which is the famous

Norman Rockwell painting of Ruby, the US Marshals who had to protect her from an angry segregationist White crowd, and the ugly slur hurled at her by adults.

"There's no need to emphasize it," she says of the slur. "Just, you know, if they want to read 'this book has a famous painting,' fine. And then just move on."

There's no safe way to teach "Separate Is Never Equal," a 2014 picture book about a landmark legal case that integrated the southern California schools in the 1940s, Steenman says. The book should be banned, because it features contemporaneous quotes uttered by White segregationists in court.

"They [students] are sitting there listening to this, and all they're hearing is 'Mexicans are dirty, inferior in scholastic ability. They have skin problems and lice' and it just goes on and on and on about it," Steenman said as she flipped through the pages. "And I submit that's what they're going to take from that book, because they're just not ready."

This idea that second-graders can't handle history -- that hearing about it could, in fact, make them racist or hate their own race -- is central to the Moms For Liberty complaint against the Williamson County public schools.

The debate over "Separate Is Never Equal," is a surprise to Duncan Tonatiuh, the award-winning author of the book.

"The villain here is racism and segregation," Tonatiuh told CNN while flipping through the pages. "At the end of the book, what I wanted to show is the Mexican American children and the White children being in school together and playing together and interacting with each other."

Tonatiuh has won a number of awards for writing engaging stories for a young audience. He said he's read the book to many elementary school students and the response has been nothing like what Steenman fears.

"When I shared the story with kids, I don't see kids saying, 'oh, this makes me feel shame,'" he said. "They say, 'that's not right. That's not fair. That's not how people should treat people.' That's the reaction that I get."

National education experts are worried about the fear from mostly White parents spreading in places like Williamson County, Tennessee.

"There isn't a crisis in how we teach history in this country," said Kim Anderson, executive director of the National Education Association, which represents thousands of teachers across the US. She says the idea that kids shouldn't hear the realities of the past is a scary one.

"You would never go into a school in, in Germany and say, oh, why do you teach about Nazi-ism?" she said. "You would, you would never ask that question because they do teach about it because teachers want kids in Germany to understand what that history was."

What is past, and what is present

Steenman says she doesn't know what age is appropriate for students to hear about the dogs, firehoses, bullets people like Ruby Bridges faced decades ago.

She's not sure how relevant that history is to Williamson County today.

"I'm not going to argue [whether] racism still exists," she says. "I don't personally know any."

Months before Moms For Liberty showed up, public school moms Revida Rahman and Jennifer Cortez had started their own group -- One Willco -- after a string of racial incidents rocked the district. The district sent students on field trips to a nearby plantation site (there are several in the area) and Rahman's husband chaperoned one trip. She said he was shocked to hear little mention of how plantations actually worked.

"It didn't have a context other than being a fun place," she said "We have not known plantations to be a fun place."

On the playground, Rahman said her children and other children of color have faced bullying.

"My son had an incident at his middle school, where students locked arms. And, and if you were White, they would break the arms to let kids go through," she said, recalling a story she learned from her son in the pickup line at school right after it happened. "If you were Black, they kept their hands together and told you that you needed to go back to Mexico."

"They said they were building a wall," Cortez said.

The Williamson County School District is 97% White, according to U.S. Department of Education

data. It's a well-to-do district overall, with a high level of college educated parents and a large household median income.

Last month, the Williamson County school community and one of its sports rivals were

shocked by a threatening social media message sent to a Black player by a White one wearing a Klan hood.

The effort to leave recent American history out of the curriculum could make it harder for students of color trying to go to school now, according to One Willco. Racism is an active issue that needs to be confronted, the moms said.

"They're bullying our school board. They're bullying our elected officials," Cortez said of Moms For Liberty. "They're causing real harm in our communities."

Interpreting 'discomfort'

Rahman worries the law passed in May is broad and could be used to target teachers and take history out of schools.

"When you say discomfort, if the teacher can have some discomfort, where do you draw the line in that process?" she said. "That's, what's concerning about the law. It's not inclusive of everybody. I don't think it's divisive, talking about these uncomfortable topics."

A spokesperson for the school board in Williamson County told CNN school leaders in the county have launched a "Reconsideration Committee" to review the books Moms For Liberty has complained about. One board member familiar with the process said new Tennessee law is hard to interpret, but this board member said they expect the state will ban at least one of the books Moms For Liberty cited.

"Discomfort" clauses like the one in Tennessee are a fixture in the push to pass legislation aimed at racial history education across the country.

It's a crisis moment in classrooms, according to the NEA's Anderson.

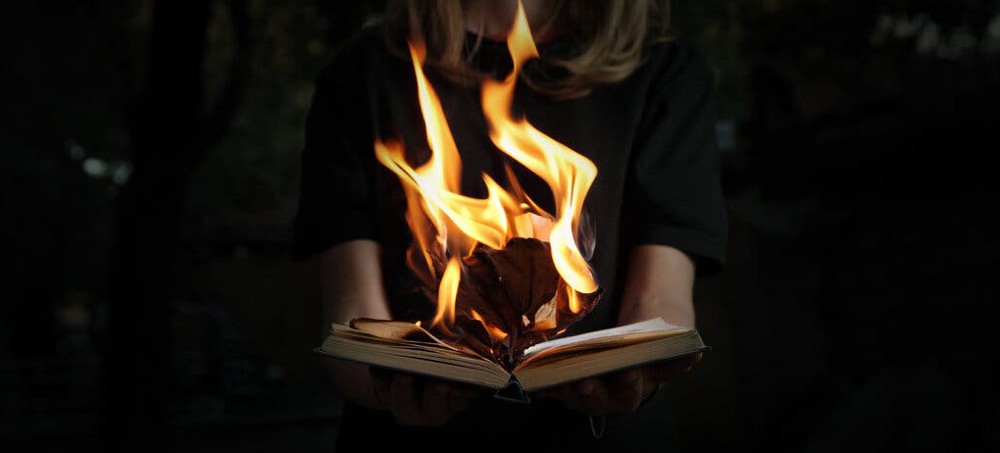

"We're heading toward a pretty scary time," she said. "If we're talking about politicians, banning books, uh, I thought we were long past those days."