Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

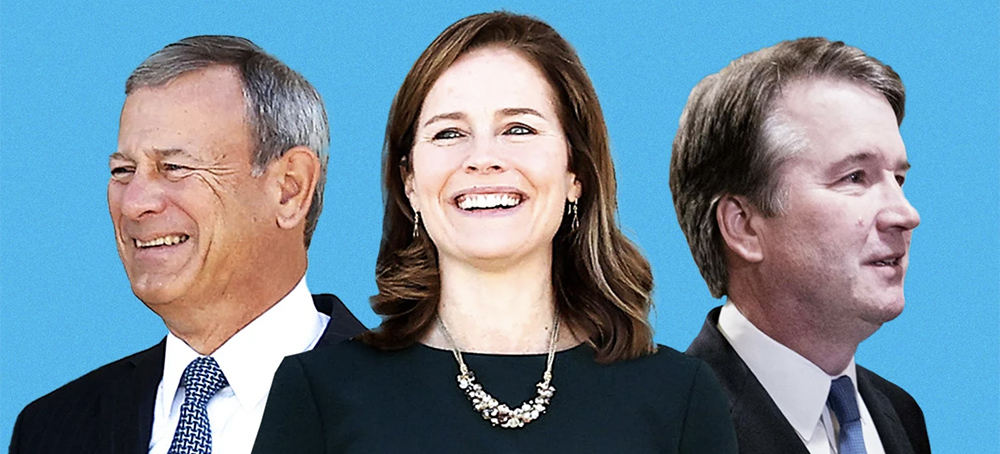

Amy Coney Barrett, Brett Kavanaugh, and John Roberts agree with the liberals about one thing.

This group’s concerns were not unitary. The chief justice, unsurprisingly, doesn’t like it when state courts ignore the directives of the Supreme Court. Kavanaugh was worried about the implications for gun owners and gun dealers if blue states were to pass copycat laws of S.B. 8, allowing citizens to collect bounties by suing gun owners anywhere in the country. And Barrett evinced fear that those suffering constitutional harms could find themselves in state courts someday, unable to air and effectuate federal constitutional rights. In short, Roberts worries, as he always does, about Supreme Court supremacy, and Barrett and Kavanaugh are smart enough to see that the wisdom of nullifying fundamental constitutional rights at the state level will always turn on whose ox is being gored.

Good enough, for the present moment, if it means that Texas is likely to lose its fight to evade judicial scrutiny for S.B. 8, a law that not only bans abortion at six weeks but also lets bounty hunters sue providers and their “abettors” for $10,000. But this alliance tells us nothing about how Roe v. Wade will fare when the court squarely takes on abortion rights in next month’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. What we know now is that there are certainly going to be reliably three votes—Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch—for the proposition that abortion rights are made up and unworthy of protection, and indeed that any mechanism that ends abortion, be it state nullification, fictitious heartbeat claims, or unsubstantiated racial eugenics claims, is a good thing. Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch are not, in Thomas’ own words, “evolving” as jurists.

The question remains, and it’s an important one, what happened to Barrett and Kavanaugh? Both justices were perfectly happy to sign off on the shabby one-paragraph shadow docket order that allowed S.B. 8 to go into effect in September. The issue before the court this week—still raising “complex and novel antecedent procedural questions”—is jurisdictional and hypertechnical. And yet these concerns should have been evident to anyone looking at the issue all summer: S.B. 8 was explicitly designed to avoid federal scrutiny; it could be copied to violate other rights; it represented a direct threat to Supreme Court authority. Somehow, none of these features swayed Kavanaugh or Barrett back in August. What changed to put these two justices into play now?

One answer is public condemnation: the outcry over the shadow docket throughout September and October, the backlash against the justices’ partisan speeches, and the tanking poll numbers for the Supreme Court. It is possible that the two newest justices worry about things like their own court’s legitimacy. In large ways (they’d like to be employed in 20 years on a court that doesn’t have 60 members) and small (they really want to be fêted at D.C. cocktail parties and restaurants right now), neither of them is entirely willing to go Full Vader on America at this point. That means it’s possible that public outcry and organizing around the court affects them.

Another data point to support this theory: On Friday, Kavanaugh and Barrett joined Roberts and the liberals in a 6–3 order rejecting a challenge to Maine’s vaccine mandate, which permits no religious exemptions. Barrett wrote a brief opinion, joined by Kavanaugh, explaining the perils of intervening “on a short fuse without benefit of full briefing and oral argument.” Clearly, these two junior justices are cognizant of the fury over their abuse of the shadow docket and, unlike Alito, eager to contain it.

Kavanaugh’s primary reason for questioning S.B. 8’s gambit was revealed in Monday’s arguments as … a concern for gun owners. We’ll take it. Barrett, who is quickly establishing herself as one of the most able questioners on the bench, may genuinely care about the ongoing preservation of constitutional rights and the role of the judiciary. We’ll take it. But what does any of this signal headed into a term in which gun rights, religious freedom, (possibly) affirmative action, climate change, and voting rights may all be in the crosshairs?

Most obviously, the S.B. 8 litigation sends a warning to other conservative litigants before the court: Don’t overplay your hand. The law’s proponents were brash from the start, boasting that they designed the law to evade judicial review. And after the justices allowed it to take effect in September, S.B. 8’s defenders took their arrogance to a new level. In one stunning brief, Jonathan Mitchell—the conservative lawyer and former Texas solicitor general who drafted S.B. 8, then teamed up with the state to defend it—rejected the Supreme Court’s power to say what the law is. States, he wrote, “have every prerogative to adopt interpretations of the Constitution that differ from the Supreme Court’s.” (When Roberts quoted this very language during arguments, Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone declined to defend it.)

Mitchell also took aim at the authority of the court’s precedents. “The Supreme Court’s interpretations of the Constitution,” he wrote, in the same brief, “are not the Constitution itself—they are, after all, called opinions.” Mitchell also engaged in some wink-wink-nudge-nudge hedging about the future of Roe v. Wade, writing: “Abortion is not a constitutional right; it is a court-invented right that may not even have majority support on the current Supreme Court. A state does not violate the Constitution by undermining a ‘right’ that is nowhere to be found in the document, and that exists only as a concoction of judges who want to impose their ideology on the nation.”

It is safe to assume that Kavanaugh and Barrett do not appreciate litigators smearing the many justices who have upheld Roe over five decades as rogue and lawless and ideologues. That list, after all, includes the current chief justice, as well as both of their predecessors. (Kavanaugh also clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy, who repeatedly voted to save Roe.) Nor do they necessarily appreciate litigators assuming that Kavanaugh and Barrett are already in the tank for overturning Roe. As a rule, justices do not like being treated as trivial pawns in a larger political game.

Perhaps most critically, these justices do not seem to appreciate arguments that exude disdain for their institution. It’s easy to see why Mitchell thought he could get away with this rhetoric; the majority’s shadow docket order raised the possibility that five justices agree with his position that Roe is absolute trash undeserving of any respect, effective immediately. But whatever his merits as a lawyer, Mitchell is an exceedingly bad politician: After Donald Trump nominated him as the chairman of the obscure Administrative Conference of the United States, he couldn’t even win confirmation from a GOP-controlled Senate. The anti-abortion movement’s apparent faith in his ability to drag Roe to the curb before the court has signed off may be misplaced.

Most litigators are not as insolent as Mitchell. But his attitude is evident among many of the parties asking the court to overrule Roe in Dobbs. His own brief, a misogynistic screed that impugns the integrity of every justice who supports Roe, declares that women can “control their reproductive lives” by simply “refraining from sexual intercourse.” This attitude and approach are the cornerstone of Mississippi’s litigation strategy too. The state first persuaded SCOTUS to take up Dobbs by asking the justices merely to weaken Roe. Then, once the court had taken up the case, Mississippi demanded that SCOTUS overturn Roe altogether—a bait-and-switch for the ages. (Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch also insisted that God chose her case as the vehicle for abolishing abortion rights. One might reasonably assume that Kavanaugh and Barrett prefer to think that their votes are not predetermined by a higher power who works through elected Mississippi officials.)

Most conservative litigators don’t swagger into the Supreme Court like they own the place. The lawyers asking SCOTUS to expand the Second Amendment may know they’re going to win; so do the lawyers asking SCOTUS to gut climate regulations, turbocharge religious freedom, eradicate affirmative action, and undermine voting rights. But for the most part, these attorneys still perform humility before the justices. By doing so, they take part in the grand pageantry that allows Kavanaugh and Barrett to view themselves as humble servants of the law rather than partisan actors in a zero-sum political game. Silly as this pageant may seem, it is especially important in momentous cases that implicate the court’s legitimacy. S.B. 8’s proponents thought they could forgo these formalities, assuming the fall of Roe is a foregone conclusion. It might still be. But on Monday, Kavanaugh and Barrett reminded them, in surprisingly blunt fashion, not to count the votes before they’re cast.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment