When Repos Blew Up in 2019, Hedge Funds Were $800 Billion Short U.S. Treasury Futures; Then Margins Blew Out

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 3, 2022 ~

New details have emerged to provide a fuller picture of the turmoil that was taking place in the dark corners of markets when the overnight repo market blew up on September 17, 2019 and the Fed had to run to the rescue with trillions of dollars in cumulative loans that went on for months.

Imagine if you were the Federal Reserve and had been thoroughly disgraced by waging more than a two-year court battle to prevent the press in America from doing its job and publishing the granular details of the Fed’s 2007 to 2010 bailout of Wall Street and its foreign bank derivative counterparties. Then the Fed was further disgraced after losing the court battles when in 2011 the details of the $29 trillion bailout were published. Chances are that the Fed would not be anxious to let the public or Congress hear the latest details of bailing out hedge funds for the one percent that were using leverage of 50 to 1 obtained from the very banks the Fed is supposed to be supervising.

That background might help to explain why there was a complete news blackout by mainstream media, including by reporters assigned to cover the Fed, when the Fed began releasing the names of the trading units of the Wall Street megabanks that were pigs at its emergency repo bailout trough from September 17, 2019 through December 31, 2019.

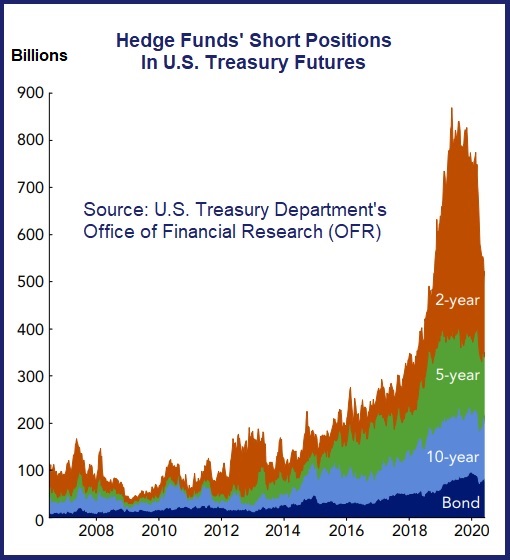

That background might also help to explain why the Treasury Department’s Office of Financial Research (OFR) wrote a research paper attempting to shift hedge fund turmoil in the Treasury futures market to March of 2020 – after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. – but slipped up and included two graphs that move the onset of the turmoil to smack dab in September of 2019.

As we next describe what happened, it’s important to remember that thanks to the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999, Wall Street has been allowed to structure itself into a daisy chain of systemic contagion. The same trading houses giving 50-to-1 margin loans to hedge funds on their Treasury securities as their so-called “prime brokers,” are the same “primary dealers” used by the New York Fed for its open market operations and contractually bound to be buyers of Treasury securities when the government issues new debt. The primary dealers that are the sugar daddies to hedge funds and get a regular pat on the head from the New York Fed, are, for the most part, owned by the megabanks on Wall Street which also own giant, federally-insured, deposit-taking banks that hold trillions of dollars of mom and pop savings accounts and insured money market accounts.

But in addition to holding trillions of dollars of insured mom and pop savings, these same taxpayer-backstopped megabanks also hold hundreds of trillions of dollars in dodgy derivatives which remain, for the most part, a black hole to regulators despite the promise of the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 to clean up this mess.

We mention this because when any part of this highly interconnected daisy chain teeters, the key players begin to back away from providing more lending to the others because the lack of transparency prevents any player from knowing who has the bulk of the risk and might blow up.

This situation has moved the Fed from its original mandate as lender-of-last-resort to commercial banks that are the backbone of the U.S. economy to lender-of-last-resort to the high rollers on Wall Street.

The OFR report explains how hedge funds were getting 50-to-1 leverage from their prime brokers (who are not named in the report but include JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, and Citigroup Global Markets and others) and engaging in a strategy called the basis trade. The OFR report describes the strategy as follows:

“The basis trade relies on a relationship between the cash Treasury market, where investors purchase Treasuries today; the Treasury futures market, where investors agree on a fixed price to pay for Treasuries they will receive in the future; and the repo market, where investors borrow or lend Treasuries against cash today. Theoretically, borrowing a Treasury today in the repo market, for which the investor pays interest at the repo rate, should cost the same amount as purchasing that Treasury today in the cash market with the agreement to sell that Treasury in the futures market at a later date. Very small variations from that ideal can be profitable if the investment is leveraged using borrowed capital.

“Basis trades are three-legged trades that span crucial financial markets: cash Treasury markets, Treasury futures markets, and repo markets. As we show, basis trades use long cash Treasury positions and short futures positions to construct a payoff that, absent financing risks and other frictions, would be a net position similar to a Treasury bill. (In futures markets, long positions are a bet prices will go up; short positions are a bet prices will go down.) One immediate difference between the return on a basis trade and the return on a bill is the possible variation margin on the futures position. (Futures traders make variation margin payments when the value of cash and collateral in their accounts falls below set margin levels.) More importantly, basis traders generally finance the long cash position in the repo market, which exposes the basis trade to rollover and liquidity risks. The return on basis trade is thus equivalent to a synthetic bill plus a risk premium. This risk premium is positive on average but can vary significantly and can turn negative during times of stress in funding markets.”

The OFR report also offers this on the subject of leverage: “Hedge fund leverage is constrained only by the haircuts on the collateral, and for Treasury securities haircuts are typically around 2 percent. This implies a maximum leverage ratio for hedge funds of 50 to 1.”

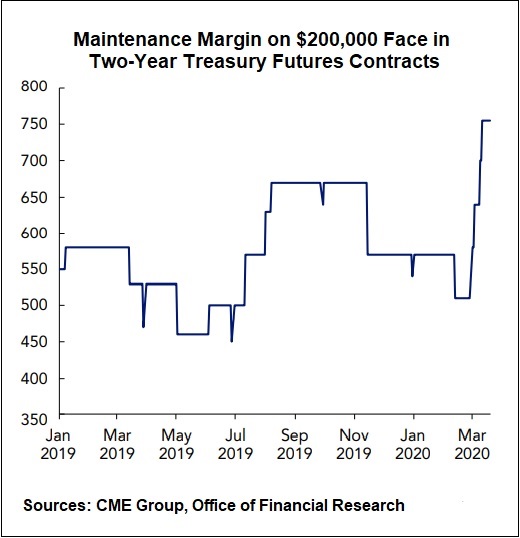

As we previously indicated, the OFR is attempting to shift all of this to the blow up in the Treasury market in March of 2020 but it slipped up and included the chart above and the chart below. The chart above shows that in 2019, hedge funds’ short positions in U.S. Treasury futures had skyrocketed to more than $800 billion. The chart below shows that the key players became alarmed and started demanding increased maintenance margin on the trades. (Maintenance margin is the minimum equity an investor must maintain in a margin account after the purchase has been made. The amount required at purchase is called the “initial” margin.)

Notice how the sharp rise in maintenance margin first occurred in the month of September 2019 and had started to abate as the Fed pumped in tens of billions of dollars a day in repo loans but then surged again in 2020 as pandemic panic took hold.

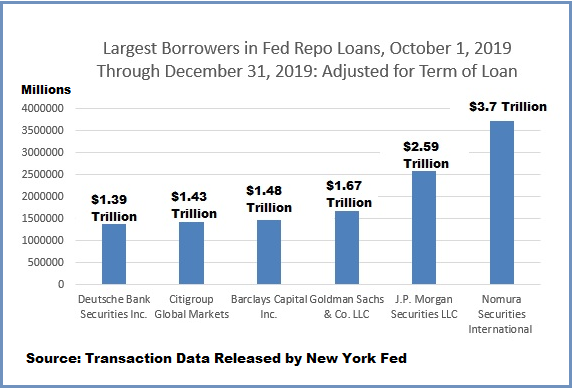

The chart below shows the names of the six largest borrowers and their borrowing amounts from the data released by the New York Fed. (These are the cumulative total of the loans, adjusted for the terms of the loans.) This is the information that mainstream media refuses to release to the public – possibly out of fear that it contradicts the Fed’s narrative that the repo crisis in 2019 grew out of corporations withdrawing their quarterly tax payments from the banks. But the largest borrower in the last quarter of 2019 from the Fed’s emergency repo operations was Nomura Securities International, part of the large Japanese investment bank. It certainly wasn’t a major holder of corporate tax payments for U.S. corporations.

A Bloomberg News article on March 19, 2020 named Field Street Capital Management as one of the hedge funds that had lost significant sums on the basis trade.

Yesterday, we checked out Field Street’s Form ADV on file with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Field Street lists as its prime brokers the following: Bank of America Securities; J.P. Morgan Securities; and Merrill Lynch Professional Clearing Corp. (part of Bank of America). Bank of America Securities and J.P. Morgan Securities are two of the Fed’s primary dealers; they were also heavy borrowers during the Fed’s repo bailout; and they are two of the four largest derivatives holders among all U.S. banks.

Field Street’s Form ADV also indicates that J.P. Morgan Securities is not just one of its prime brokers but is also a “marketer” of the hedge fund. As the chart above shows, J.P. Morgan Securities was the second largest borrower from the Fed’s repo bailout during the last quarter of 2019.

This does not mean that the basis trades blowing up were the sole cause of the repo crisis in the fall of 2019.

As we have previously indicated, Nomura was heavily exposed to derivatives; Deutsche Bank, a major counterparty to the derivatives of Wall Street’s megabanks, was in a death spiral; and $2.7 billion in credit default swaps blew up the very day before the Fed launched its repo bailout.

In other words, the ill-conceived, incompetently regulated, and opaque structure of Wall Street appears to have been coming apart at the seams in September 2019.

It is nothing short of a travesty against the American people that Congress has failed to investigate the matter, that mainstream media refuses to accurately report what happened, and that the Fed thinks Americans are stupid enough to believe its dumb corporate tax payment excuse (something corporations do every quarter).

We’ll be forwarding this article this morning to the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee, both of which oversee the Fed.

No comments:

Post a Comment