Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

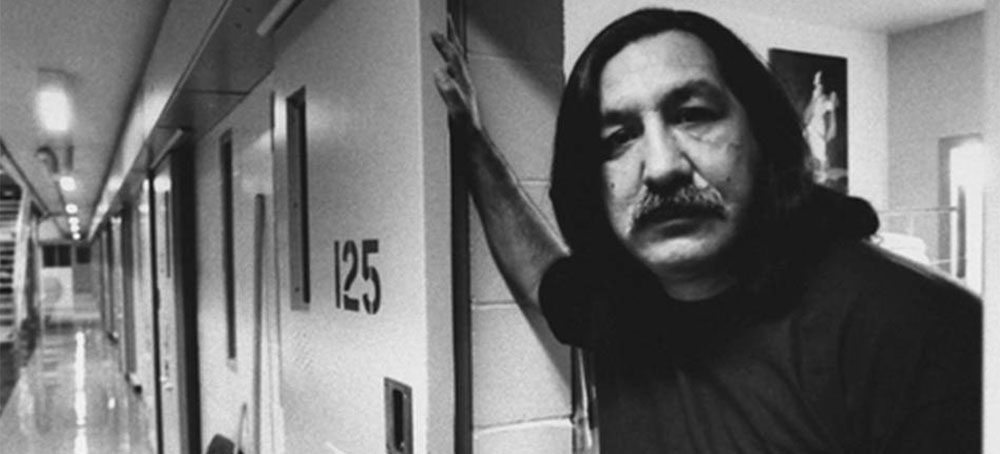

The jailed Native American activist Leonard Peltier has tested positive for COVID, less than a week after describing his prison as a “torture chamber.” Peltier, who suffers from multiple health conditions, says he and others held at the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex in Florida have yet to receive their COVID booster shots and describes worsening neglect and uncertainty. In a statement, Leonard Peltier writes, “Left alone and without attention is like a torture chamber for the sick and old.”

The 77-year-old Leonard Peltier is a Lakota and Chippewa Native American from the state of North Dakota. He’s been jailed for 46 years. In 1977, he was convicted of killing two FBI agents during a shootout on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in 1975. At the time, Peltier was a member of AIM, the American Indian Movement. He has always maintained his innocence. Amnesty International considers him a political prisoner who was not granted a fair trial.

The 1975 shootout occurred two years after AIM occupied the village of Wounded Knee for 71 days. The occupation of Wounded Knee is considered the beginning of what Oglala people refer to as the “reign of terror.” During that time, some 64 Native Americans were murdered. Most of them had ties to AIM. Their deaths went uninvestigated by the FBI.

Over the past 25 years, Indigenous and human rights groups lobbied both President Clinton and President Obama to pardon Leonard Peltier, but they refused. Now President Biden is facing pressure to do so. On Wednesday, Senator Brian Schatz, who’s chair of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, wrote a letter to Biden urging him to commute Peltier’s sentence.

We’re joined now by Leonard Peltier’s lawyer, Kevin Sharp. Kevin Sharp is a former federal judge who resigned from the bench to fight against mandatory minimum laws. He’s joining us from Nashville, Tennessee.

Welcome to Democracy Now! Do we call you Judge Sharp even though you have left your judgeship?

KEVIN SHARP: You know, it’s one of the few things I get to hang onto, the title.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Judge Sharp, first, if you can tell us about Leonard’s condition? And then talk about why you took on his case.

KEVIN SHARP: Well, the condition part is tough, because it’s difficult to get information out of the BOP, the Bureau of Prisons. There are — he tested positive on Friday, and so there were people there that I was able to talk to. Over the weekend, you have a very skeleton crew, and there’s really not much information I could get, although they would talk to me briefly, except to say he’s doing OK and has not had to have been moved yet. So, so far, so good. As soon as this segment is over, I’m going to call the prison again, and I should be able to get a hold of his counselor. But that’s where we are. He has COVID. He’s feeling really poorly. This is the information I had on Friday. And he’s been quarantined. And so, that’s kind of where we are.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Judge Sharp, talk about why you took on Leonard Peltier’s case.

KEVIN SHARP: You know, that’s interesting, because when I stepped down from the bench, I started working on clemency for a young man that I had sentenced to life in prison. I thought that — it was a mandatory minimum sentence, very unfair. And I started working on clemency for him. And ultimately we were able to get clemency from President Trump. But Kim Kardashian got involved in that case. And with Kim’s involvement came a lot of media attention.

That media attention caught the attention of a woman, Willie Nelson’s ex-wife, Connie Nelson, in Texas, who asked someone to send me all of the information on Leonard’s case. I sat down to read the stacks, just reams of information on Leonard’s case, not really coming at it with any preconceived notion. I didn’t know much about it. I was only 12 years old when the events happened, so I didn’t know much. And I came at this looking at it from the viewpoint of a federal judge. And what I saw was shocking. The constitutional violations just continued to stack up, and I was really outraged that this man was still in prison, knowing what everyone now knew. And so, with that, I agreed to take on this case pro bono.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Kevin Sharp, I sort of laid out the case of Leonard Peltier. But can you, after reviewing it, looking at all the documents, knowing what you know as a judge and a lawyer, lay out Leonard Peltier’s case? What most shocked you about it? And then, what are your grounds now for asking for the commutation of his sentence?

KEVIN SHARP: Well, they relate to each other. The things that most shocked me was the level of outright misconduct by the U.S. Attorney’s Office, the then-U.S. Attorney’s Office, and the then-FBI, what they did in the form of intimidating and threatening witnesses, hiding exculpatory evidence, suborning perjury. And all of that is known. When Leonard appealed all of these issues over the years, some of it was known, some of it wasn’t, but the standards were different. And if this case were brought up today, no question: This verdict gets overturned.

And ultimately, even the U.S. Attorney’s Office had to admit that they don’t know who killed the agents. And so, we’re sitting here with the prosecutor saying, “We don’t know who did it, but, sure, life sentence for this man seems fine.” As a matter of fact, in the early '90s, 60 Minutes did a segment on this, and they talked to the assistant U.S. attorney who tried the case, and specifically asked him about perjury of one of the witnesses, a woman named Myrtle Poor Bear. And initially, the AUSA said, “I didn't know it was perjured testimony,” but then he looks in the camera and says, “But so what if I did? It doesn’t bother my conscience one whit.” And at that, I’m looking at that and going, they knew it, and he’s admitting it here on national television.

What they did was outrageous and completely ignoring the Constitution of the United States so that they could get a conviction. Part of the reason for that, that kind of fervor to get a conviction at any cost, is because his co-defendants were acquitted based on self-defense. So he’s really their last chance at getting a conviction. And so, it was a conviction at any cost.

Now, once it was discovered, one of the things they had done was withhold exculpatory evidence. That’s evidence that tends to show the person is not guilty of the crime you’re accusing them of committing. And that exculpatory evidence in this case was a ballistics test that they had testified did not exist, when in fact it did exist. And it wasn’t discovered for years afterwards. So, by withholding that ballistics test, it deprived Mr. Peltier of a fair trial. The Constitution requires that that be shown. So, you know, these things just stack up, and that’s what so outraged me.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go back to Election Day 2000. I had a chance to interview then-President Bill Clinton. He had called our radio station, Pacifica station WBAI, in an attempt to get out the vote for Hillary Clinton for Senate and Al Gore for president. So I used the opportunity to ask him about the case of Leonard Peltier.

AMY GOODMAN: President Clinton, since it’s rare to get you on the phone, let me ask you another question. And that is: What is your position on granting Leonard Peltier, the Native American activist, executive clemency?

PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON: Well, I don’t — I don’t have a position I can announce yet. I think if — I believe there is a new application for him in there. And when I have time, after the election is over, I’m going to review all the remaining executive clemency applications and, you know, see what the merits dictate. I will try to do what I think the right thing to do is based on the evidence.

AMY GOODMAN: So, I now want to turn to Leonard Peltier in his on words. Shortly after I interviewed President Clinton in 2000, I spoke to Leonard when he was being held at the Leavenworth federal penitentiary in Kansas.

LEONARD PELTIER: My name is Leonard Peltier. I’m a Lakota and Chippewa Native American from the state of North Dakota. I am currently serving two life sentences for the deaths of two FBI agents in Leavenworth United States Penitentiary.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you kill the FBI agents?

LEONARD PELTIER: No, I did not. No.

AMY GOODMAN: Maybe we could go back to that day that these FBI agents were killed, and you could tell us what happened.

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, at that time, there was a — what is known as today as a region of terror going on against traditional people from the so-called progressives under a tribal chairman named Dick Wilson, who was very corrupt, who organized his own private police force, kind of like a Contra group, and started terrorizing his own people, own traditionalists on the reservation. So the traditionalists asked for the help of the American Indian Movement. And the end result, after long protests and my getting no responses from any law enforcement agency in the country, Wounded Knee II was then occupied, and there was a 71-day siege.

After that, he, Dick Wilson, again intensified his goon squads. And the General Accounting Service, an agency of the United States government, did an investigation, and before the funding was — ran out, they found over 60 murdered Indian people, traditionalists. And so, on June 26th, we didn’t know it at the time, but we knew later from Freedom of Information documents, that the FBI, with the goon squads, were planning on attacks on the Jumping Bull Ranch and another ranch in Kyle — that’s another community on the reservation — that they were declaring American Indian Movement strongholds. And on June 26th, a firefight started. And the end result was two FBI agents and one Indian, young Indian man, was killed.

And they indicted four of us — Bob Robideau, Dino Butler, Jimmy Eagle. After a year, they dropped the charges on Jimmy Eagle. And Bob and Dino went to trial in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and was found not guilty by reasons of self-defense. I was later — my trial was mysteriously moved from Cedar Rapids, which I was supposed to go to trial at the same place under the same judge as my co-defendants — was mysteriously moved to Fargo, North Dakota.

Later documents show that the FBI then went judge shopping to get a judge to work closely with them. And Judge Paul Benson agreed to do it. And I was not allowed to put up a defense. They manufactured evidence. The murder weapon was perjury by government witnesses. And the judge erred in his rulings, which prevented me from putting up a defense.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that was Leonard Peltier in 2000, almost — well, over two decades ago. He was at Leavenworth. I spoke to him in 2012. It was the day after a major fundraiser for him at the Beacon Theatre, a major concert fundraiser, and there was an event the next day. And it was in that room that he was able to call in. I spoke to him on the phone from prison. At that point he was in Florida, and this was during the Obama administration.

AMY GOODMAN: Leonard, this is Amy Goodman from Democracy Now! I was —

LEONARD PELTIER: Oh, hi, Amy. How are you?

AMY GOODMAN: Hi. I’m good. I was wondering if you have a message for President Obama?

LEONARD PELTIER: I just hope he can, you know, stop the wars that are going on in this world, and stop getting — killing all those people getting killed, and, you know, give the Black Hills back to my people, and turn me loose.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you share with people at the news conference and with President Obama your case for why you should be — your sentence should be commuted, why you want clemency?

LEONARD PELTIER: Well, I never got a fair trial, for one. … They wouldn’t allow me to put up a defense, and manufactured evidence, manufactured witnesses, tortured witnesses. You know, the list is — just goes on. So I think I’m a very good candidate for — after 37 years, for clemency or house arrest, at least.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that was Leonard Peltier nine years ago in prison from Florida. Judge Sharp, now Leonard Peltier’s lawyer, can you talk about the significance of what he said in these two conversations — and also, the first one, speaking to him during Clinton, in fact, wasn’t President Clinton close to granting him clemency? — and then under Obama, and what you hope will be different under President Biden?

KEVIN SHARP: Well, yes. Let me kind of take those in pieces. What Leonard said was accurate. Most of what he said, some of it was because he was there, so he’s got his own personal accounts, and some of it is backed up by documents turned over during the Freedom of Information Act — or, through a Freedom of Information Act request. We now know that the witnesses were intimidated. He’s absolutely right about that. We now know that exculpatory evidence showing this was not his weapon that killed the agents — we now know that was hidden. We now know that Myrtle Poor Bear was forced to lie. We know that the young boys who were the major witnesses, eyewitnesses against him, recanted that testimony. It wasn’t true. So we know those things. Yet here we are 46 years later still talking about whether or not this man should be freed.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office, the federal government, says, “We do not know who killed the agents.” They ended up — because of all of the misconduct that was discovered in the trial, they changed their theory from one that he shot these agents to aiding and abetting. Well, then the question becomes: Who did he aid and abet? Because his co-defendants were acquitted based on self-defense. So, who did he aid and abet? When asked that question, the assistant U.S. attorney, in one sense, a flippant response was, “I don’t know. Maybe himself.” Well, that’s impossible. You cannot aid and abet yourself.

So, all of those things stacked up with time tell you this — enough is enough. And I realize I say that, but it is absolutely true. This has to end. And, yes, my understanding from talking to the people involved at the time of the Clinton administration was that the papers were on his desk to be signed. Why they weren’t signed, I don’t know. I don’t know. The same with President Obama. I don’t know how close he got. But it tells you there is a constituency.

The big misconception about this is that Leonard Peltier was convicted of shooting two agents. He was not. They had to drop that, because there was — the evidence that they had presented that he had shot two agents was false. It was perjury. It was manufactured. So they had to drop that case and come up with a new theory, and that theory was aiding and abetting. And when Leonard talked about not being able to put on his defense, one of the things that Judge Benson said was — when he excluded the evidence related to the misconduct in the reign of terror, was that the FBI is not on trial here. But once he did that, you have to put all of this in context. That’s why Judge Heaney, who was on the 8th Circuit, who heard his appeal — and although upheld the conviction, later came out himself in favor of commuting this sentence — said the federal government has to take responsibility for what happened here. And absolutely, they do. Context matters. But the lack of evidence that this man killed someone also matters.

And so it’s time. We’re now 46 years later. We’ve got a 77-year-old man with multiple health issues, and his tribe, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, saying, “We will embrace him. Please send him home to us.” And that’s what I’m asking the president to do: Send him home.

AMY GOODMAN: Judge Sharp, what did J. Edgar Hoover have to do with this case, the former head of the FBI at the time?

KEVIN SHARP: You know, that comes back into COINTELPRO, where there was a division inside the FBI tasked with running counterintelligence against our own citizens. And they did that with respect to Martin Luther King, the student nonviolent movement, the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement. If they considered them to be subversive, then they were running counterintelligence against them. And so, although Hoover was gone by 1975, we’re only one director removed from Hoover, and the tactics — if not a group within the FBI that had that name, the tactics still existed. And that’s exactly what was happening. It’s very Vietnamesque.

AMY GOODMAN: And I wanted to read a part of Senator Schatz’s letter, the senator from Hawaii, who appealed to President Biden. He is chair of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. He wrote, “Mr. Peltier meets appropriate criteria for commutation: (1) his old age and critical illness, (2) the amount of time he has already served, and (3) the unavailability of other remedies.” Explain what he’s saying.

KEVIN SHARP: Well, there is the ability to release prisoners under compassionate release and as part of the commutation powers of the president of the United States. And he’s asking the president, based on those criteria, to end this and send Leonard home. And he’s absolutely right about that. This is — and I hear this from executives, who say, “Well, the criminal justice system worked. I’m not going to step in and inject myself into the criminal justice system.” What they are doing, though, is abdicating their responsibility as part of the criminal justice system, the president or governor, in the case of a state, that they are the criminal justice system, and they have the ability to step in and correct a wrong like this, where the legal remedies — particularly because of the standard of review at the time, the legal remedies are no longer available. Now it’s time for the BOP and the president of the United States to fix this and send him home.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to end by reading more from Leonard Peltier’s statement on the current conditions inside the Coleman prison. Leonard Peltier writes, “I’m in hell, and there is no way to deal with it but to take it as long as you can. I cling to the belief that people are out there doing what they can to change our circumstances in here. The fear and stress are taking a toll on everyone, including the staff. You can see it in their faces and hear it in their voices. The whole institution is on total LOCKDOWN.”

He says, “In and out of lockdown last year at least meant a shower every third day, a meal beyond a sandwich wet with a little peanut butter — but now with COVID for an excuse, nothing. No phone, no window, no fresh air — no humans to gather — no loved one’s voice. No relief. Left alone and without attention is like a torture chamber for the sick and old.”

He writes, “Where are our human rights activists? You are hearing with me, and with me, many desperate men and women! They are turning an already harsh environment into an asylum, and for many who did not receive a death penalty, we are now staring down the face of one! Help me, my brothers and sisters, help me my good friends.”

Those are the words of jailed Native American leader Leonard Peltier after 46 years in prison, now at the Coleman prison in Florida. Judge Kevin Sharp is his new judge and — is his new lawyer and is appealing for clemency from President Biden. Finally, Kevin Sharp, has President Biden responded to your plea?

KEVIN SHARP: He has not. And I noticed in the press conference last week a reporter asked him about that and — or asked the press secretary about that, and she begged off of that, said, you know, she was unable to answer that question. So, you know, I know that it’s on the president’s radar, and he has the opportunity to fix this. And he has the opportunity to be a president with courage and a president who cares about the United States Constitution. It’s, you know, pick up the pen and sign the paper, and let’s end this. Let’s stop talking about this. The FBI says, “We are not the FBI of the 1970s.” And I believe them. But now let’s show it. Show it and support clemency for Mr. Peltier.

AMY GOODMAN: Kevin Sharp is a former federal judge and now an attorney who represents Leonard Peltier. Again, the latest news, Leonard Peltier is sick with COVID.

Next up, President Biden is meeting with New York’s new mayor, Eric Adams. Both want to put more police on the street. We’ll look at the national debate over policing with Patrisse Cullors, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, author of a new book, An Abolitionist’s Handbook. Stay with us.

Anti-abortion activists pray outside the US Supreme Court in Washington, DC, on October 2, 2021. (photo: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP/Getty Images)

Anti-abortion activists pray outside the US Supreme Court in Washington, DC, on October 2, 2021. (photo: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP/Getty Images)

Almost as soon as Justice Barrett was confirmed, the Court handed down a revolutionary “religious liberty” decision. It hasn’t slowed down since.

Months earlier, when the seat she would fill was still held by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Court had handed down a series of 5-4 decisions establishing that churches and other houses of worship must comply with state occupancy limits and other rules imposed upon them to slow the spread of Covid-19.

As Chief Justice John Roberts, the only Republican appointee to join these decisions, explained in South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom (2020), “our Constitution principally entrusts ‘[t]he safety and the health of the people’ to the politically accountable officials of the States.” And these officials’ decisions “should not be subject to second-guessing by an ‘unelected federal judiciary,’ which lacks the background, competence, and expertise to assess public health and is not accountable to the people.”

But this sort of judicial humility no longer enjoyed majority support on the Court once Barrett’s confirmation gave GOP justices a 6-3 supermajority. Twenty-nine days after Barrett became Justice Barrett, she united with her fellow Trump appointees and two other hardline conservative justices in Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo (2020), a decision striking down the very sort of occupancy limits that the Court permitted in South Bay. The upshot of this decision is that the public’s interest in controlling a deadly disease must give way to the wishes of certain religious litigants.

Just as significantly, Roman Catholic Diocese revolutionized the Court’s approach to lawsuits where a plaintiff who objects to a state law on religious grounds seeks an exemption from that law.

Before Roman Catholic Diocese, religious objectors typically had to follow a “neutral law of general applicability” — meaning that these objectors must obey the same laws that everyone else must follow. Roman Catholic Diocese technically did not abolish this rule, but it redefined what constitutes a “neutral law of general applicability” so narrowly that nearly any religious conservative with a clever lawyer can expect to prevail in a lawsuit.

That decision is part of a much bigger pattern. Since the Court’s Republican majority became a supermajority, the Court has treated religion cases as its highest priority.

It’s made historic changes to the law governing religion even before it moved on to other major priorities for the conservative movement, such as restricting abortion or expanding gun rights. The Court has also taken on new religion-related cases at a breakneck pace. In the eight years of the Obama presidency, the Court decided just seven religious liberty cases, or fewer than one per year. By contrast, by the second anniversary of Barrett’s confirmation as a justice, the Court most likely will have decided at least seven — and arguably as many as 10 — religious liberty cases with Barrett on the Court.

In fairness, many factors contribute to this uptick in religion cases being head by the Court, and at least some of these factors emerged while Barrett was still an obscure law professor. The Court’s decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), for example, opened the door to new kinds of lawsuits that would have failed before that decision was handed down. And lawyers for Christian conservative litigants have no doubt responded to Hobby Lobby by filing more — and more aggressive — lawsuits.

This piece did not attempt to quantify the number of times the Court has been asked to decide religious liberty cases, only the number of times it decided to take the case.

But the bottom line is that the federal judiciary is fast transforming into a forum to hear the grievances of religious conservatives. And the Supreme Court is rapidly changing the rules of the game to benefit those conservatives.

The Court’s new interest in religion cases, by the numbers

As mentioned above, the Supreme Court heard fewer than one religious liberty case every year during the eight years of the Obama presidency.

In deriving this number, I had to make some judgment calls regarding what counts as a “religious liberty” case. For the purposes of this article, I’m defining that term as any Supreme Court decision that is binding on lower courts, and that interprets the First Amendment’s free exercise or establishment clause. I also include decisions interpreting two federal statutes — the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act — both of which limit the government’s ability to enforce its policies against people who object to them on religious grounds.

I focused on these two constitutional provisions and these two federal laws because they deal directly with the obligations the government owes to people of faith and its ability to involve itself in matters of religion.

My definition of a “religious liberty” case excludes some Supreme Court cases involving religious institutions that applied general laws or constitutional provisions. Shortly after Obama became president, for example, the Court denied a religious group’s request to erect a monument in a public park. Yet, while this case involved a religious organization, the specific legal issue involved the First Amendment’s free speech clause, not any religion-specific clause. So I did not classify that case as a religious liberty case.

In any event, using this metric, I identified seven religious liberty cases decided during Obama’s presidency,¹ the most consequential of which was Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.

Interestingly, the Court did not decide significantly more religious liberty cases in the three years that Donald Trump was president prior to the pandemic, just four in total.² The Court then did decide a rush of pandemic-related religious liberty cases in 2020, including South Bay and Roman Catholic Diocese.

But things really took off once Justice Barrett was confirmed in the week before the 2020 election. As noted above, the Court handed down Roman Catholic Diocese, a hugely consequential case that reimagined the Court’s approach to the Free Exercise Clause, less than a month after Barrett took office. Just a few months later, the Court handed down Tandon v. Newsom (2021), which clarified that all lower courts are required to follow the new rule laid out in Roman Catholic Diocese.

Notably, both Roman Catholic Diocese and Tandon were decided on the Court’s “shadow docket,” a mix of emergency decisions and other expedited matters that the Court typically decided in brief orders that offered little analysis. In the Trump years, however, the Court started frequently using the shadow docket to hand down decisions that upended existing law.

On the merits docket, the ordinary mix of cases that receive full briefing and oral argument, the Court decided two religious liberty cases during Barrett’s first term on the Court, Tanzin v. Tanvir (2020) and Fulton v. City of Philadelphia (2021) — though Barrett was recused in Tanzin and the Court announced it would hear Fulton before Barrett joined the Court. Three other religious liberty cases (Ramirez v. Collier, Carson v. Makin, and Kennedy v. Bremerton School District) are still awaiting a decision on the Court’s merits docket.

Meanwhile, three other shadow docket cases arguably belong on the list of important religious liberty cases decided since Barrett joined the Court, although these cases produced no majority opinion and thus did not announce a legal rule that lower courts must follow. In Does v. Mills (2021) and Dr. A v. Hochul (2021), the Court rejected claims by health care workers who sought a religious exemption from a Covid vaccination mandate. And, in Dunn v. Smith (2021), the Court appeared to back away from a gratuitously cruel decision involving the religious liberties of death row inmates that it handed down in 2019.

So, to summarize, by the time the Court’s current term wraps up in June, the Court will likely hand down decisions in three merits docket cases — Ramirez, Carson, and Kennedy, although it is possible that Kennedy will not be scheduled for argument until next fall. Add in the two merits docket decisions from last term and the landmark shadow docket decisions in Roman Catholic Diocese and Tandon, and that’s seven religious liberty decisions the Court is likely to hand down before Barrett celebrates her second anniversary as a justice.

Meanwhile, the Court only handed down seven religious liberty cases during all eight years of the Obama presidency.

So what do all of these religion cases actually say?

As the Does and Dr. A cases indicate, the Court’s 6-3 Republican majority still hands occasional defeats to conservative religious parties. It also sometimes hands them very small victories. Fulton, for example, could have overruled a seminal precedent from 1990, and given religious conservatives a sweeping right to discriminate against LGBTQ people. Instead, the Fulton opinion was very narrow and is unlikely to have much impact beyond that particular case.

But, for the most part, the Court’s most recent religion cases have been extraordinarily favorable to the Christian right, and to conservative religious causes generally. Many of the Court’s most recent decisions build on earlier cases, such as Hobby Lobby, which started to move its religious jurisprudence to the right even before Trump’s justices arrived. But the pace of this rightward march accelerated significantly once Trump made his third appointment to the Court.

Broadly speaking, three themes emerge from these cases.

Exceptions for conservative religious objectors

First, the Court nearly always sides with religious conservatives who seek an exemption from the law, even when granting such an exemption is likely to injure others.

The Hobby Lobby decision, which held that many employers with religious objections to birth control could defy a federal regulation requiring them to include contraceptive care in their employees’ health plans, was an important turning point in the Court’s approach to religious objectors. Prior to Hobby Lobby, religious exemptions were not granted if they would undermine the rights of third parties. As the Court suggested in United States v. Lee (1982), an exemption that “operates to impose the employer’s religious faith on the employees” should not be granted. (Indeed, Lee held that exemptions typically should not be granted at all in the business context.)

Initially, the new rule announced in Hobby Lobby, which permits religious objectors to diminish the rights of others, only applied to rights established by federal law. Under the federal RFRA statute, religious objectors are entitled to some exemptions from federal laws that they would not be entitled to if their state enacted an identical law. As mentioned above, religious objectors must comply with state laws so long as they are “neutral” and have “general applicability” — meaning that they apply with equal force to religious and secular actors.

That brings us to Roman Catholic Diocese and Tandon, which redefined what qualifies as a neutral law of general applicability so narrowly that hardly any laws will qualify. (A more detailed explanation of this redefinition can be found here and here.)

Indeed, Roman Catholic Diocese and Tandon permitted religious objectors to defy state public health rules intended to slow the spread of a deadly disease. If the Court is willing to place the narrow interests of religious conservatives ahead of society’s broader interest in protecting human life, it seems likely that the Court will be very generous in doling out exemptions to such conservatives in the future.

Fewer rights for disfavored groups

While the Court has been highly solicitous toward conservative Christian groups, it’s been less sympathetic to religious liberty claims brought by groups that are not part of the Republican Party’s core supporters.

The most glaring example of this double standard is Trump v. Hawaii (2018), in which the Court’s Republican appointees upheld then-President Trump’s policy banning most people from several Muslim-majority nations from entering the United States. The Court did so, moreover, despite the fact that Trump repeatedly bragged about his plans to implement a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on.”

The Trump administration claimed that its travel plan was justified by national security concerns, and the Court held that it typically should defer to the president on such matters. But that does not change the fact that singling out Muslims for inferior treatment solely because they are Muslim violates the First Amendment. And, in any event, it’s hard to imagine the Supreme Court would have shown similar deference if Trump had attempted a shutdown of Roman Catholics entering the United States.

Similarly, in Dunn v. Ray (2019), the Court’s Republican appointees ruled against a Muslim death row inmate who sought to have his imam present at his execution, even though the state permitted Christian inmates to have a spiritual adviser present. As Justice Elena Kagan wrote in dissent, “the clearest command of the Establishment Clause ... is that one religious denomination cannot be officially preferred over another.”

In fairness, the Court does not always reject religious liberty claims brought by Muslims, even if those claims prevail less often than in similar cases brought by conservative Christians. In Holt v. Hobbs (2015), for example, the Court sided with an incarcerated Muslim man who wished to grow a short beard as an act of religious devotion.

After Dunn triggered a bipartisan backlash, moreover, the Court appeared to back away for a while. Nevertheless, during November’s oral argument in another prison-religion case, this one brought by a Christian inmate who wishes to have a pastor lay hands on him during his execution, several justices appeared less concerned with whether ruling against this inmate would violate the Constitution — and more concerned with whether permitting such suits would create too much work for the justices themselves.

Thus, while the Court typically sides with conservative Christians in religious liberty cases, people of different faiths (or even Christians pursuing causes that aren’t aligned with political conservatism) may be less likely to earn the Court’s favor.

The wall of separation between church and state is in deep trouble

Several of the justices are openly hostile to the very idea that the Constitution imposes limits on the government’s ability to advance one faith over others. At a recent oral argument, for example, Justice Neil Gorsuch derisively referred to the “so-called separation of . . . church and state.”

Indeed, it appears likely that the Court may even require the government to subsidize religion, at least in certain circumstances.

At December’s oral arguments in Carson v. Makin, for example, the Court considered a Maine program that provides tuition vouchers to some students, which they can use to pay for education at a secular private school when there’s no public school nearby. Though the state says it wishes to remain “neutral and silent” on matters of religion and not allow its vouchers to go to private religious schools, many of the justices appeared to view this kind of neutrality as unlawful. “Discriminating against all religions,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh suggested, is itself a form of anti-religious discrimination that violates his conception of the Constitution.

For many decades, the Court held the opposite view. As the Court held in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), “no tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion.”

But Everson’s rule is now dead. And the Court appears likely to require secular taxpayers to pay for religious education, at least under some circumstances.

Why is the Court hearing so many religion cases?

There are several possible explanations for why the Court is hearing so many more religion cases than it used to, and only some of these explanations stem from the Court’s new 6-3 Republican majority.

The most significant non-political explanation for the uptick in cases is the pandemic, which triggered a raft of public health orders that religious groups sought exemptions from in the Supreme Court. Though a less ideological Court would not have used one of these cases to revolutionize its approach to the free exercise clause, as it did in Roman Catholic Diocese, the Court likely would have weighed in on many of these cases even if it had a Democratic majority.

Similarly, some explanations for the uptick in cases predate the confirmation of Justice Barrett. The Hobby Lobby decision, for example, sent a loud signal that the Court would give serious consideration to religious liberty claims that once would have been turned away as meritless. That decision undoubtedly inspired lawyers for conservative religious litigants to file lawsuits that they otherwise would not have brought in the first place.

The Court also started frequently using the shadow docket to hand down highly consequential decisions well before Barrett joined the Court. Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned that the Court was using shadow docket cases to grant “extraordinary” favors to Trump as recently as 2019.

But there’s no doubt that the Court’s new majority is eager to break things and move quickly. Ordinarily, for example, if the Court were going to fundamentally rethink its approach to an important provision of the Constitution, it would insist upon full briefing, conduct an oral argument, and spend months deliberating over any proposed changes. Instead, Roman Catholic Diocese was handed down less than a month after the Court had the votes it needed to rewrite its approach to the free exercise clause.

There are also worrisome signs that the Court’s new majority cares much less than its predecessors about stare decisis, the doctrine that courts should typically follow past precedents. Just look at how the Court has treated Roe v. Wade if you want a particularly glaring example of the new majority’s approach to precedents it does not like.

Roman Catholic Diocese was handed down just six months after the Court’s contrary ruling in South Bay. And there’s no plausible argument that the cases reached different outcomes because of material distinctions between the two cases. The only real difference between the two cases was that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg sat on the Court in May 2020, and Amy Coney Barrett held Ginsburg’s seat by November. That was enough reason to convince this Court to abandon decades of precedent establishing that religious institutions typically have to follow the same laws as everyone else.

The Court’s current majority, in other words, is itching for a fight over religion. And it holds little regard for established law. That means that a whole lot is likely to change, and very quickly.

A mural in Derry, Northern Ireland, UK commemorating the Bloody Sunday massacre of January 30, 1972. (photo: murielle29/ Flickr)

A mural in Derry, Northern Ireland, UK commemorating the Bloody Sunday massacre of January 30, 1972. (photo: murielle29/ Flickr)

Fifty years ago today, British soldiers killed 13 unarmed civilians on a civil rights march in Derry. Britain’s most senior judge, Lord Widgery, then published an official report on the massacre filled with lies, giving judicial sanction to murder.

In the aftermath, there should have been no question about what had taken place in Derry. The only questions to be determined were how and why. Had the soldiers of the Parachute Regiment’s (“Paras”) First Battalion simply run amok? Or was the massacre the predictable outcome of a criminally reckless plan devised by senior officers?

Instead, the families of the victims had to wait nearly four decades for Lord Mark Saville to acknowledge that all those killed were unarmed civilians, and for the British prime minister David Cameron to apologize for their deaths. Throughout that period, the official line of the British state, as expressed in the report published by Lord John Widgery in April 1972, was that the soldiers had only begun shooting after coming under sustained fire, and that they sincerely believed their targets to be armed gunmen.

Widgery served as the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, the country’s most eminent judicial figure, between 1971 and 1980. His report was an orchestrated litany of lies, to borrow a celebrated phrase from a far more honorable magistrate, the New Zealand judge Peter Mahon. It deserves to be remembered as the most shameful episode in the modern history of the British legal system.

By falsifying the events of Bloody Sunday, Widgery ensured that the relatives of those killed would have to spend decades campaigning to establish the basic facts. The British establishment eventually discarded his report when it was no longer expedient to engage in barefaced denial of the truth. But it had already done incalculable damage by that point. Tasked with enforcing the rule of law, Widgery left a trail of carnage and broken lives in his wake.

Checks and Balances

Those who see the British political system as an example to the world — the “cradle of democracy,” no less — often refer to the checks and balances that are supposed to prevent any abuse of power. If one part of the British state poses a threat to civic freedoms, another will step in to correct the injustice.

There is also supposed to be a check on executive power from outside the state itself: the “fourth estate,” represented by the British media. In the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, however, Britain’s leading broadsheet newspapers rushed to hold the marchers responsible for their own deaths. The Times absolved the army of any blame in its editorial:

Those who are inciting the Catholics to take to the streets know very well the consequences of what they are doing. Londonderry had a taste of those consequences last night. The dead are witness to them.

The Daily Telegraph insisted that the civil rights movement was little more than a front for the Irish Republican Army (IRA):

It does not murder; it simply creates the conditions favorable to the murders attempted by others and leaves the army in the last resort with no alternative but to fire. Its courage may be less than that of the IRA; its guilt is not.

The Guardian ignored the account of its own reporter, Simon Winchester, who had been in Derry for the march. Its lead writer also blamed the people who had organized the civil rights demonstration:

The disaster in Londonderry last night dwarfs all that has gone before in Northern Ireland. The march was illegal. Warning had been given of the danger implicit in continuing with it. Even so, the deaths stun the mind and must fill all reasonable people with horror. As yet it is too soon to be sure of what happened. The army has an intolerably difficult task in Ireland. At times it is bound to act firmly, even severely. Whether individual soldiers misjudged their situation yesterday, or were themselves too directly threatened, cannot yet be known. The presence of snipers in the late stages of the march must have added a murderous dimension. It is a terrible warning to all involved.

After Bloody Sunday, the Sunday Times could have run an excellent, thoroughly researched article by its reporter Murray Sayle that was ready within a week. Sayle’s work would have removed all excuse for evasive agnosticism about the circumstances of the massacre. But his editors decided to spike it, citing concerns that it might prejudice the inquiry to be chaired by Lord Widgery. The London Review of Books finally published Sayle’s article three decades later.

“Entirely Satisfied”

Widgery was thus helping to conceal the truth before he had even got down to work in earnest. There was considerable debate in Derry about whether people should cooperate with the inquiry at all. The prevailing view held that it would be impossible for any judge, no matter how prejudiced, to ignore the sheer volume of evidence that discredited the army’s version of events. This seemed like a reasonable argument at the time; however, those making it had underestimated Lord Widgery’s imaginative prowess.

In his 1992 book, Bloody Sunday in Derry: What Really Happened, Eamonn McCann composed a devastating rebuttal of the Widgery report, which we can only summarize briefly here. Widgery’s treatment of what happened in Rossville Flats, where the Paras claimed their first victim, seventeen-year-old Jack Duddy, gives a flavor of his methodology.

The soldiers claimed to have come under intense fire from IRA snipers; one reported hearing about eighty shots. These gunshots were supposed to have come from several directions in a courtyard that was surrounded on three sides by nine-story blocks of council flats. The soldiers reported taking cover behind their armored personnel carrier (APC) — a vehicle that, as McCann dryly observed, “is considerably more bulky than, say, a Ford Transit van.” Yet not one of these alleged IRA bullets managed to hit its target, and none of the soldiers called for backup during this supposedly life-threatening encounter.

McCann summed up their testimony as follows:

The APC drives into the Rossville Flats courtyard. The soldiers disembark to arrest hooligans. They immediately come under fire from the flats. The flats are, at the nearest point, within 15 yards of the APC. Some of the soldiers take cover behind the vehicle. None of them is hit. The APC is not hit. The senior man on the spot does not bother to tell anyone that any of this is happening. Afterwards, every soldier’s account of the pattern of hostile fire contradicts every other soldier’s account.

This was not the only eyewitness testimony available to Lord Widgery. The list of civilian eyewitnesses who contradicted the army version included a Catholic priest, a schoolteacher, a Guardian reporter, and an English-born veteran of the Royal Navy. It would be difficult to imagine a more respectable cross section of society. Widgery dismissed their evidence out of hand and accepted what the soldiers had told him despite its glaring implausibility:

I am entirely satisfied that the first firing in the courtyard was directed at the soldiers. Such a conclusion is not reached by counting heads or by selecting one particular witness as truthful in preference to another. It is a conclusion gradually built up over many days of listening to evidence and watching the demeanour of witnesses under cross-examination.

As McCann noted, Widgery made no attempt to justify this assessment on logical grounds: “His reference to the demeanour of witnesses and his ‘many days’ (three days in fact) of listening to the relevant evidence is his entire account of his process of reasoning.”

After a torrent of verbiage about the imaginary gunfight in the Rossville Flats courtyard, Widgery suddenly dried up when it came to Glenfada Park, where the Paras had discharged two-fifths of all the bullets fired by soldiers that day, killing four people and wounding five more. Having composed passages A) and B) about events in Rossville Flats and nearby Rossville Street, Widgery omitted to include a passage C) about Glenfada Park. His findings about what happened in the area came in a later section dealing with the men who had been killed there.

Widgery began by announcing that he would “deal with the cases of these four deceased together because I find the evidence too confused and too contradictory to make separate consideration possible.” He went on to declare that he found it “difficult to reach firm conclusions” when confronted with “such confused and conflicting testimony.” Yet he rejected a claim by “Soldier H” that he had shot repeatedly at a man firing with a rifle from the window of a nearby flat: “19 of the 22 shots fired by Soldier H were wholly unaccounted for.”

If, by Widgery’s own assessment, one of the soldiers had brazenly lied about nineteen of the shots he discharged in a compressed space where four men died from bullet wounds, it does not require any great imaginative leap to put two and two together. McCann’s judgement is unanswerable: “He took these four cases together and dealt with them perfunctorily precisely because the evidence was in no way confused or contradictory, but definite and devastating. This is the reason there is no passage C).”

“A Balance of Probabilities”

In the same section, Widgery gave credence to a claim by British soldiers that they had found nail bombs on the body of teenager Gerald Donaghy. Donaghy had been brought, badly injured, into a nearby house, where a doctor examined him. A Belfast Telegraph reporter was also present at the scene. Nobody saw any nail bombs in the pockets of his tight-fitting jeans.

Some of the people in the house attempted to bring Donaghy to a hospital. Soldiers stopped their car at a checkpoint and brought it to a first aid post, where the medical officer pronounced Donaghy dead. He didn’t find any nail bombs, either. Mirabile dictu, a soldier then claimed to have discovered four such projectiles on the corpse, one of which was sticking out of Donaghy’s pocket, visible at the merest glance.

Widgery’s evaluation of this evidence noted that there were two possibilities: either all the people who examined Donaghy before the soldiers did, including two doctors, had missed the nail bombs, or else somebody had planted the evidence on his corpse afterwards. Widgery declared this to be a “relatively unimportant detail” but summoned the energy to pronounce judgement on the matter since it was “no doubt of great concern to Donaghy’s family”:

I think that on a balance of probabilities the bombs were in Donaghy’s pockets throughout. His jacket and trousers were not removed but were merely opened as he lay on his back in the car. It seems likely that these relatively bulky objects would have been noticed when Donaghy’s body was examined; but it is conceivable that they were not and the alternative explanation of a plant is mere speculation. No evidence was offered as to where the bombs might have come from, who might have placed them or why Donaghy should have been singled out for this treatment.

McCann’s rebuttal of this argument is worth quoting at length:

Widgery’s complaint about the absence of evidence as to the origin of the bombs and the identity of the person who planted it is nonsensical. The only persons who could have tendered this evidence would have been those responsible for the planting. It was not to be wondered at that they did not come forward. Widgery’s final reason for rejecting the plant theory — that there was no evidence why Donaghy should have been singled out for such treatment — suggests a lack of concern for both logic and common sense. One wonders what Widgery might have said to the defence counsel in a bank robbery case who offered as an argument for his client’s innocence that there was no evidence he had any particular grudge against that particular bank.

On the basis of such reasoning, Widgery confidently declared his “strong suspicion” that some of those killed or injured by the Paras “had been firing weapons or handling bombs in the course of the afternoon.”

“Isolated Allegations”

The Widgery report was an artful piece of work, lawyerly in the most pejorative sense of the term. Its author would not have attained the rank of chief justice without excellent rhetorical skills and a razor-sharp mind. He deployed those talents in the service of a cover-up.

One of Widgery’s favorite tricks was the confidently stated non sequitur. At the very end of the report, Widgery dismissed all claims that soldiers had been “firing carelessly from the hip or shooting deliberately at individuals who were clearly unarmed.” These were, he said, “isolated allegations in which the soldier was not identified.” As McCann pointed out, the word “isolated” had no relevance to what was being discussed:

The most obvious meaning which might attach to it would refer to the allegations having been made separately by different individuals. But how else might such allegations be made so that Widgery might accord them some seriousness — by a massed choir of Bogsiders chanting in unison? Similarly, to give weight to the fact that the people of the Bogside and Creggan could not identify individual Paras who opened fire is nonsensical. What did Widgery expect? Names? With his ready agreement, the solders did not give their names to his Tribunal.

Widgery will have known perfectly well that his brief conclusions would count for more in the propaganda war than the tortuous reasoning on which they were purportedly based, unfolded over the space of 20,000 words. He accused the march organizers of having “created a highly dangerous situation in which a clash between demonstrators and the security forces was almost inevitable” and claimed to have found “no reason to suppose that the soldiers would have opened fire if they had not been fired upon first.”

The Daily Mail greeted the report with an editorial hoot of triumph:

Against cynical propagandists the British Government replies with judicial truth. It is like trying to exterminate a nest of vipers by the Queensberry rules. Even so, over the past two and a half years of mounting terrorism, the record shows — and it is a record which now includes Lord Widgery’s report — that our troops are doing an impossible job impossibly well.

Eamonn McCann’s summary was rather more to the point. He dismissed the idea that Widgery’s social and political background had prevented him from forming a clear picture of what happened that day:

The inconsistencies, illogicalities and untruths in the report cannot be attributed to an inability to discover and tell the truth. The distance between the report and the reality yawns far too widely for that. It is a politically motivated unwillingness to tell the truth, not an inability to see the truth, which explains the Widgery report.

Widgery’s judicial colleagues applied the same standards of logic and evidence that he had laid down in other notorious cases related to the Irish conflict, such as those of the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four. In fact, it was Widgery himself who rejected the first appeal by the Six, claiming that they had suffered “no ill treatment beyond the normal” when police officers tortured them into signing false confessions.

The Rule of Law

Half a century later, the list of those willing to credit the army’s original version of events about Bloody Sunday is thankfully short. But there has still been no reckoning with the implications of the Widgery report for the British legal system. In 2010, one of Widgery’s successors as Lord Chief Justice, Tom Bingham, published a widely praised book called The Rule of Law. The name “Widgery” was entirely absent from its pages.

Bingham’s omission was all the more striking because he did not write as a complacent reactionary, arguing, for example, that the 2003 invasion of Iraq was unlawful and criticizing Tony Blair for belittling the importance of civil liberties in the face of terrorism. He also strongly defended the Human Rights Act of 1998 against criticism from British Conservatives. Yet when it came to the most fundamental human right — the right to life — and the abject failure of his esteemed predecessor to uphold that right, Bingham observed a tactful silence.

Perhaps the lessons of Widgery cut too close to the bone. It is one thing for judges to present themselves as guardians of law and liberty against the abuses of political officeholders. It is quite another to recognize that judges themselves have marched in lockstep with those responsible for the murder of innocent people.

Lord Saville’s 2010 report, and David Cameron’s acknowledgment that the killings were “unjustified and unjustifiable,” did not mean that the guardrails of liberal democracy had belatedly started to work. By the time Saville completed his work, Sinn Féin was part of a regional power-sharing government under British rule, and the majority of Irish nationalists now supported the Good Friday Agreement. It would have been entirely counterproductive for the British state and its ruling class to publish a report doubling down on Widgery’s fabrications.

The real test of those guardrails had come in 1972. Not only was that year the bloodiest one of the Troubles — it was also a time of heightened social conflict in Britain itself, with the first miners’ strike delivering a sharp blow to Edward Heath’s government. Over the course of the decade, right-wing commentators openly discussed the idea of using the British army as a tool of domestic repression.

In 1974, the future Sunday Telegraph editor Peregrine Worsthorne went to Chile on a trip that its military junta paid for. Worsthorne claimed that the junta enjoyed “very widespread popularity among all classes” and even praised the conditions in a forced labor camp to which he paid a visit. He concluded his article with an emphatic message for the home front:

All right, a military dictatorship is ugly and repressive. But if a minority British Socialist Government ever sought, by cunning, duplicity, corruption, terror and foreign arms, to turn this country into a Communist State, I hope and pray our armed forces would intervene to prevent such a calamity as efficiently as the armed forces did in Chile.

When the Labour MP Chris Mullin composed his novel A Very British Coup in 1982, he gave its arch-conspirator the name “Sir Peregrine.”

This was the climate of opinion in which Lord Widgery got to work. He would have wanted to make it absolutely clear to soldiers of the British Army that they would face no legal consequences for gunning people down in broad daylight on the streets of the United Kingdom. Widgery was determined to uphold the rule of power, not the rule of law, and every paragraph of his report bears the stamp of that objective.

Family and friends of Lauren Smith-Fields gather in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on 23 January. (photo: Ned Gerard/AP)

Family and friends of Lauren Smith-Fields gather in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on 23 January. (photo: Ned Gerard/AP)

Officers did not investigate the deaths of Lauren Smith-Fields and Brenda Lee Rawls in a timely manner or notify relatives

According to family members, investigations into the deaths of Lauren Smith-Fields, 23, and Brenda Lee Rawls, 53, both on 21 December, were mishandled by officers who did not investigate in a timely manner or notify relatives.

Smith-Fields was found unresponsive in her apartment after a date with a man she met through the dating app Bumble. The man, who is white and whose name has not been released as he has not been charged with a crime, called 911.

Police did not notify Smith-Fields’s family. When she did not respond to text messages or calls, her mother and brother drove to her apartment. They found a note on her door reading: “If you’re looking for Lauren, call this number.”

Smith-Fields’s landlord subsequently told her family about her death and passed on the number of the detective assigned.

When Smith-Fields’s family asked officers about the man who was with her, her mother told the New York Times, the investigating detective said not to worry and that “he’s a really nice guy”.

Amid widespread outrage, a medical examiner said Smith-Fields died from an accidental overdose of fentanyl combined with prescription medication and alcohol. The acting Bridgeport police chief, Rebeca Garcia, said police were now focusing on “the factors that led to her untimely death”.

Confirmation of the cause of Rawls’s death is pending, according to the Connecticut chief medical examiner. She was reportedly found unresponsive by an acquaintance who said her body was taken by police and coroner’s officials.

Family members were not notified directly by law enforcement. After calls to police, hospitals and funeral homes, the state medical examiner, who had already performed an autopsy, confirmed her death.

“It’s almost like they’re not aware of her death, or they just don’t care and that made us angry,” Dorothy Washington, Rawls’s sister, told CNN. “She was raised and born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, paid her taxes, voted and they treated like she was nothing. Like she was roadkill.”

On Sunday, Joseph Ganim, the mayor of Bridgeport, shared his condolences with the families of the two women. He was, he said, “extremely disappointed with the leadership of the Bridgeport police department”.

Ganim also called for disciplinary action against the two officers, “for lack of sensitivity to the public and failure to follow police policy”.

“The Bridgeport police department has high standards for officer sensitivity, especially in matters involving the death of a family member,” Ganim said. “It is an unacceptable failure if policies were not followed.

“To the families, friends and all who care about the human decency that should be shown in these situations in this case by members of the Bridgeport police department, I am very sorry.”

Bridgeport police did not immediately comment.

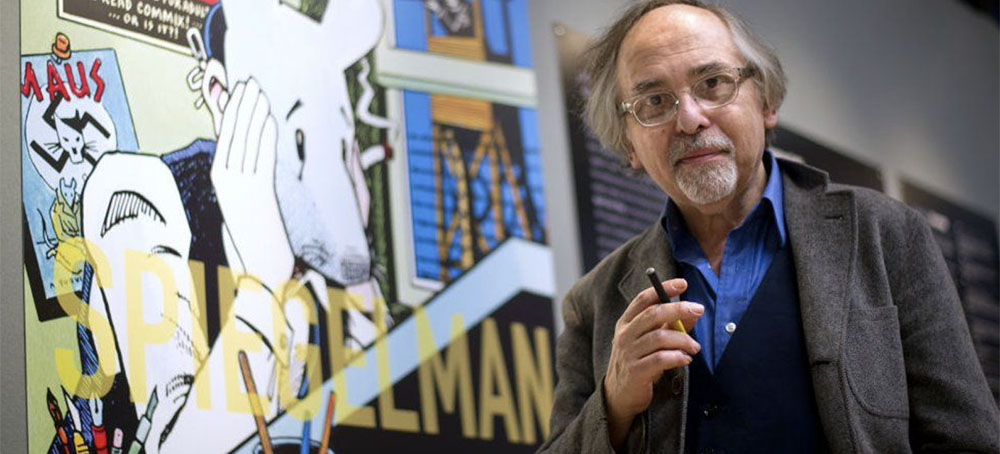

Art Spiegelman's graphic novel tells the story of how his parents survived in Nazi concentration camps during World War Two. (photo: Getty Images)

Art Spiegelman's graphic novel tells the story of how his parents survived in Nazi concentration camps during World War Two. (photo: Getty Images)

A Pulitzer prize-winning novel about the Holocaust has topped Amazon's best-seller's list after a school board in Tennessee banned it.

Board members voted in favour of banning the novel because it contained swear words and a naked illustration.

But now The Complete Maus, which includes all volumes, is a best-seller.

Other editions are topping Amazon sub-categories, including Comics … Graphic Novels.

Six million Jewish people died in the Holocaust - Nazi Germany's campaign to eradicate Europe's Jewish population.

Author Art Spiegelman's parents were Polish Jews who were sent to Nazi concentration camps during World War Two.

His novel, which features hand-drawn illustrations of mice as Jews and cats as Nazis, won a number of literary awards in 1992.

The book's renewed popularity came earlier this month after the McMinn County Board of Education removed it from the curriculum.

Board members said that they felt the inclusion of swear words in the graphic novel were inappropriate for the eighth grade curriculum.

In the meeting's minutes, the director of schools, Lee Parkinson, was quoted as having said: "There is some rough, objectionable language in this book."

Members also objected to a cartoon that featured "nakedness" in a drawing of a mouse.

Initially, Mr Parkinson argued that redacting the swear words was the best course of action.

But citing copyright concerns, the board eventually decided to ban the teaching of the novel altogether.

Some board members did back the novel's inclusion in the curriculum.

In an interview with CNBC the author of the novel, Mr Spiegelman, said he was "baffled" by the decision and called it an "Orwellian" course of action.

He told The New York Times that he agreed that some of the imagery was disturbing. "But you know what? It's disturbing history," he said.

The move to ban the novel comes amid a national debate over the curriculum in US public schools. Parents, teachers and school administrators have been grappling with how to teach race, discrimination and inequality in the classroom.

People hold candles during a protest against the murder of journalist Lourdes Maldonado and freelance photojournalist Margarito Martinez, which occurred in Tijuana within the span of a week, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Jan. 25, 2022. (photo: AP)

People hold candles during a protest against the murder of journalist Lourdes Maldonado and freelance photojournalist Margarito Martinez, which occurred in Tijuana within the span of a week, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Jan. 25, 2022. (photo: AP)

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show in Mexico, where a wave of murders of journalists in the last two weeks prompted reporters and their supporters to take to the streets in protests nationwide Tuesday.

PALOMAR FIERRO: [translated] I’m here with a lot of grief, because more than 100 journalists have been murdered in the last couple of years, no matter how many times we’ve protested. I was in several protests, one in 2008 dubbed “We want to be alive,” one right after the killing of Javier Valdez. Despite all our protests, the killing of journalists continues. I come here with more sadness than indignation.

AMY GOODMAN: Mexico is one of the deadliest countries in the world for journalists. Yesterday, people gathered in Tijuana, a city bordering the United States, for the funeral of reporter Lourdes Maldonado López, a well-known broadcast journalist, who had already faced multiple attacks on her life when she was shot dead in front of her home Sunday. She was the third Mexican reporter killed in the first weeks of 2022. On January 17th, another Tijuana journalist, Margarito Martínez, was shot dead in front of his residence after he had just returned from an assignment. He covered police and crime and worked as a fixer for international media. On January 10th, the body of reporter José Luis Gamboa was found in the state of Veracruz after he was stabbed to death.

The murder of Lourdes Maldonado has drawn widespread attention. She was reportedly enrolled in a protection program for journalists overseen by the Mexican government. She had a panic button in her house. In 2019, she went to a press briefing with the Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and pleaded for his help.

LOURDES MALDONADO LÓPEZ: [translated] I am here asking for your support, for your help and labor justice, because I fear for my life. I know that there’s nothing I can do against the corruption I’m experiencing in Tijuana and with this powerful person without your support, Mr. President.

AMY GOODMAN: That was 2019. This is Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador responding this week to the murder of Lourdes Maldonado.

PRESIDENT ANDRÉS MANUEL LÓPEZ OBRADOR: [translated] I wanted to address this murder, deplorable and painful like many other cases, but this one in particular. We are going to investigate thoroughly. I’m saying this because yesterday there were reports that she was here, reports saying she went to the president asking for protection, and now look what happened, as if we dismissed her, as if we didn’t care and left her without protection.

AMY GOODMAN: This comes as Lourdes’s dog refused to move from guarding the entrance to her home this week, after she was killed.

For more on the calls from Mexican authorities to investigate these killings and what should be done, we go to Tijuana to speak with Jan-Albert Hootsen. He’s the Mexico correspondent for the Committee to Protect Journalists. He attended Lourdes’s funeral yesterday.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Jan. This is a horrible loss for so many, not only in Mexico. You were at the funeral. Can you describe it for us? You spent time with the family. Tell us who was there and what the family is demanding.

JAN-ALBERT HOOTSEN: Hi. Thanks to be here.

Yes, I was yesterday at Lourdes’s funeral here in Tijuana. It was a relatively small-scale event. I think there were about 40 people, and at least half of them were journalists. It’s a big story here in Tijuana because most of the journalists here in the city actually knew Lourdes. So, for them, it was extra tragic. They had to gather at the graveyard here in Tijuana and basically cover the murder of their own friend and colleague.

The family of Lourdes was there. There were family members from the United States, who lived in San Diego, just across the border, and family members from here from Tijuana. They spoke briefly with the media amongst myself. And they were asking for justice. Her brothers said that they forgave the people who did this, and otherwise they are very anxiously waiting for the Mexican authorities to provide them with an update about what happened.

And I think, going back to your other question, what should be done, I think that’s the first thing that should be done. Authorities here in the state of Baja California need to provide clarity on who might be involved and what might be the motive behind this killing, because we don’t know that so far.

AMY GOODMAN: So, can you talk about the kind of reporting that she did, and also the fact that she had a panic button in her house?

JAN-ALBERT HOOTSEN: Sure. She was a online radio and television show host. She worked for a streaming provider called Sintoniza Sin Fronteras. And as such, she had several shows each week, in which she was heard commenting on local events. She never pulled any punches. It was about politics. It was about crime and security, Tijuana being one of the most dangerous cities in Mexico right now. She also addressed the murder of her colleague Margarito Martínez one week earlier.

And according to the Baja California state authorities, which I spoke with earlier this week, she was enrolled in a protection scheme, and she had a panic button at home in her house. But, you know, at 7 p.m., when she got back, when she was attacked, apparently she didn’t have the panic button with her. And another thing that actually we need more clarity about is that the Baja California state authorities told me that she had regular police check-ins, meaning a patrol car would check in with her residence every once in a while to see if she was OK. And apparently this wasn’t enough, and they were not present at the time when she was attacked. So, this means that whatever security measures the Mexican state had provided her, they’ve been woefully insufficient.

AMY GOODMAN: One of Lourdes Maldonado’s last broadcasts was January 19th. It was dedicated to the Tijuana photojournalist, Jan, who you just mentioned, Margarito Martínez, who was assassinated outside his home last week. This is a clip of Lourdes on her own program Brebaje, which means “Potion,” paying homage to Margarito, not knowing she’d be killed days later herself.

LOURDES MALDONADO LÓPEZ: [translated] Margarito’s death, his assassination, has left a big hole in journalism. He was recognized around the world for his work, reporting on the violence in Baja California, on the murders. He had tremendous knowledge on these issues.

AMY GOODMAN: Jan-Albert Hootsen, you know, we, in addition to having you on, were trying to reach some Mexican journalists in Tijuana, but no one would come on, fearful for what it could mean, how much danger they face. Can you talk about the danger they face and what this federal protection program is for journalists and why one is needed in Mexico, why it’s one of the deadliest places in the world for media workers?

JAN-ALBERT HOOTSEN: Sure. I was actually yesterday at the home of Margarito Martínez. I spoke with his wife for quite a long time. The place where he was killed, it’s very chilling. You walk up to her home, and there is a spot, a very large spot, that was very clearly cleaned, with flowers and with candles standing right next to it, sort of like a silent witness to what happened to Margarito.

And the kind of journalism that Margarito Martínez was specialized in was the crime and security beat. What he did is he would get up in the morning and listen to radio frequencies of the Tijuana municipal and Baja California state police, as well as the Red Cross. And whenever any incident would come in — Tijuana has on average five homicides a day — then he would jump in his car and just go to the place where the incident was reported, get out as soon as he can, take pictures, drive back home and then upload those pictures to one of the — one or more of his many employers. And that particular kind of journalism is quite dangerous in Mexico, and especially Tijuana, because it happens very often that when a journalist takes photos of these incidents, there might be someone there who doesn’t like them to do it — for example, gang members or the family members of the people who were killed, who were shot. And journalists will be followed. They will be harassed by the police. They might receive death threats. So, it’s really a daily struggle for people like Margarito.

And one of the things that I think is very important, and which I think the Mexican state needs to clarify, is that Margarito actually got in touch with the Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Journalists and Human Rights Defenders. That’s an institution that functions under the coordination of the Mexican federal government. It was created 10 years ago this year. And it is a small institution that’s focused on coordinating protection efforts with state governments and with federal agencies. The problem with this mechanism is that it’s woefully insufficient. It’s highly centralized in Mexico City; it doesn’t have any regional representation in Mexico. And even if it were — even if it did have enough money, which it really doesn’t, because it’s only working with a budget of approximately just over 15 million U.S. dollars a year — even if it had enough money, and even if it had enough public officials working for it that were well trained, then there was still the issue of impunity, the issue of crimes not being properly investigated by the Mexican authorities, which is what keeps incentivizing these killings. Apologies for the background noise —I’m here in Tijuana, and there’s a little bit of a siren back there just now.

AMY GOODMAN: We totally understand. Can you talk about the effect of the U.S.-backed so-called war on drugs, its rise in Mexico, and whether it is connected to violence against journalists and human rights defenders?

JAN-ALBERT HOOTSEN: There’s a case of, about five years ago, the murder of a journalist, Miroslava Breach, in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua. And in the years after she was murdered — she was a correspondent for national newspaper La Jornada — there have been numerous investigations into the circumstances of her death, and one of those investigations focused on the ballistic evidence. And the people who looked into that, they were able to link the murder weapon, the pistol Miroslava Breach was killed with, directly to the United States. It was a gun that was bought across the border, smuggled into Mexico and then used for numerous crimes, including the murder of Miroslava Breach.

In the case of the murder of Margarito, Baja California state authorities have already been able to link that gun to at least five crimes. And there’s a very high probability that that gun, too, has been smuggled into Mexico and then used by criminal gangs here.

I think we cannot see the violence against journalists in Mexico as something independent from the war on drugs, because the numbers, at CPJ, that we have indicate that the violence against journalists exploded just at a time when Mexico declared its U.S.-backed drug war against organized crime groups. The United States is a player in this violence, whether it likes it or not, because this is a transnational problem, and we just have no other way than to view the war on drugs as probably the main factor that fuels this violence from a sort of transnational, international perspective.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, USA Today reports the Mexican government estimates more than half a million guns are smuggled from the U.S. each year. Can you end on that note, Jan-Albert?

JAN-ALBERT HOOTSEN: Absolutely. One of my colleagues, Ioan Grillo, a British reporter here in Mexico, actually wrote a book about that called The Iron River. And it’s a phenomenon that is apparently unstoppable. There are so many guns flowing southward. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of gun stores just across the border. The ease with which smugglers can buy guns in the United States and then smuggle them over the border to Mexico is staggering.

And the current government under President López Obrador has actually been very vocal about the United States having to take measures against that. I think it’s a very tall order. It is a matter of bilateral cooperation. In the United States, there isn’t a lot of incentive currently to change it, you know, despite all the mass shootings in the U.S., but I don’t think there’s any other way than to — to drop the violence than to at least address this issue in a bilateral sense.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Jan-Albert Hootsen, we want to thank you so much for being with us, Dutch journalist and Mexico correspondent at the Committee to Protect Journalists, speaking to us from Tijuana, where Lourdes Maldonado was just memorialized at her funeral yesterday. She is one of three journalists to have been murdered in Mexico so far this year, in the first weeks of 2022.

Next up, we go to Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in occupied East Jerusalem, where Israeli forces recently evicted a Palestinian family and demolished their home. We’ll speak to the Sheikh Jarrah resident Mohammed El-Kurd, well-known Palestinian poet and activist. Stay with us.

People walk along a flooded street after the passing of Hurricane Irma in North Miami, Fla, on Sept. 11, 2017. (photo: Carlo Allegri/Reuters)

People walk along a flooded street after the passing of Hurricane Irma in North Miami, Fla, on Sept. 11, 2017. (photo: Carlo Allegri/Reuters)