Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

He ripped paper into quarters with two big, clean strokes — or occasionally more vigorously, into smaller scraps.

He left the detritus on his desk in the Oval Office, in the trash can of his private West Wing study and on the floor aboard Air Force One, among many other places.

And he did it all in violation of the Presidential Records Act, despite being urged by at least two chiefs of staff and the White House counsel to follow the law on preserving documents.

“It is absolutely a violation of the act,” said Courtney Chartier, president of the Society of American Archivists. “There is no ignorance of these laws. There are White House manuals about the maintenance of these records.”

Although glimpses of Trump’s penchant for ripping were reported earlier in his presidency — by Politico in 2018 — the House select committee’s investigation into the Jan. 6 insurrection has shined a new spotlight on the practice. The Washington Post reported that some of the White House records the National Archives and Records Administration turned over to the committee appeared to have been torn apart and then taped back together.

Interviews with 11 former Trump staffers, associates and others familiar with the habit reveal that Trump’s shredding of paper was far more widespread and indiscriminate than previously known and — despite multiple admonishments — extended throughout his presidency, resulting in special practices to deal with the torn fragments. Most of these people spoke on the condition of anonymity to share candid details of a problematic practice.

The ripping was so relentless that Trump’s team implemented protocols to try to ensure that he was abiding by the Presidential Records Act. Typically, aides from either the Office of the Staff Secretary or the Oval Office Operations team would come in behind Trump to retrieve the piles of torn paper he left in his wake, according to one person familiar with the routine. Then, staffers from the White House Office of Records Management were generally responsible for jigsawing the documents back together, using clear tape.

The Presidential Records Act requires that the White House preserve all written communication related to a president’s official duties — memos, letters, notes, emails, faxes and other material — and turn it over to the National Archives.

Typically, the White House records office makes decisions on archival vs. non-archival materials, according to an Archives official. The Presidential Records Act lays out a process allowing a president to dispose of records only after obtaining the assent of records officials.

It is unclear how many records were lost or permanently destroyed through Trump’s ripping routine, as well as what consequences, if any, he might face. Hundreds of documents, if not more, were likely torn up, those familiar with the practice say.

“It is against the law, but the problem is that the Presidential Records Act, as written, does not have any real enforcement mechanism,” said James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association. “It’s that sort of thing where there’s a law, but who has the authority to enforce the law, and the existing law is toothless.”

One person familiar with the National Archives process said that staff there were stunned at how many papers they received from the Trump administration that were ripped, and described it internally as “unprecedented.”

One senior Trump White House official said he and other White House staffers frequently put documents into “burn bags” to be destroyed, rather than preserving them, and would decide themselves what should be saved and what should be burned. When the Jan. 6 committee asked for certain documents related to Trump’s efforts to pressure Vice President Mike Pence, for example, some of them no longer existed in this person’s files because they had already been shredded, said someone familiar with the request.

Early in the administration, the torn paper became such a problem that the administration officials responsible for records management went to then-White House counsel Donald McGahn and then-deputy White House counsel Stefan Passantino, who handled ethics issues, to urge them to remind Trump and other senior West Wing staff about the importance of preserving documents to comply with the records act.

A former senior administration official said Trump was warned about the records act by McGahn, as well as his first two chiefs of staff, Reince Priebus and John Kelly, who lamented to allies that Trump would “rip up everything,” according to a person who heard his comments. Passantino also warned other aides about preserving documents.

Passantino declined to comment. McGahn did not respond to requests for comment.

A Trump spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

Priebus urged aides not to put what he called “crazy” documents on Trump’s desk — articles, for instance, from far-right websites spouting conspiracy theories, according to a person with direct knowledge of his request. He told others that Trump would read them and sometimes tear them up.

“He didn’t want a record of anything,” a former senior Trump official said. “He never stopped ripping things up. Do you really think Trump is going to care about the records act? Come on.”

Problems with records preservation persisted throughout Trump’s term and became particularly acute at the time of the transition to the Biden administration.

Other administrations have also run afoul of the Presidential Records Act. White House aides in both Democratic and Republican administrations, for example, have long used personal devices to text with reporters as well as other staff, rather than government-issued devices, while others have been caught using personal email for official work.

But people familiar with Trump’s conduct said it ran far deeper than occasionally skirting up against the boundaries of the law.

“The biggest takeaway I have from that behavior is it reflects a conviction that he was above the law,” said presidential historian Lindsay Chervinsky. “He did not see himself bound by those things.”

Former aides said Trump was haphazard in what he ripped, often tearing up papers that were not classified or even particularly sensitive. Some said they viewed it more as a quirk and not a deliberate attempt to avoid public scrutiny, in part because he was so indiscriminate with what he tore.

While he occasionally left tiny scraps, three people who watched him described a regular process — he would tear a sheet of paper in half once, and then rip it once more into quarters.

“I have seen Trump tear up papers, not into small, small pieces, but usually twice — so take a piece of paper, rip it once, and then rip it again and then throw it into the garbage pail,” said Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal lawyer who in 2018 pleaded guilty to campaign finance violations as well as lying to Congress.

The habit dates back to the former president’s time as a businessman, when he used email extremely rarely. Cohen said that Trump seemed to enjoy the actual process of ripping paper, especially if he did not like the contents of the memo.

“When something irritated him, he would tear the document,” Cohen said. “The physical act of ripping the paper for Donald was cathartic, and it provided him a relief, as if the issue was no longer relevant. Basically, you rip the piece of paper and you’re done — that’s how Donald’s brain works.”

The practice continued into the White House. Aides jokingly referred to “The Boxes” — large boxes filled with reams of paper that Trump often traveled with. Two people familiar with the boxes said they contained a true miscellany of paper — physical newspapers, articles, memos, briefing books, a media summary from the day including printed screenshots of cable news headlines — and that Trump would often rifle through them on long flights.

Sometimes he would read something and sign it in his signature Sharpie, placing it in a folder to be sent to a certain recipient, one of these people said. Other times, he would rip the paper once he was done and toss it on the floor.

This person added that they once saw Trump tear up a piece of paper and then slip it into the pocket of his suit jacket.

Trump’s troubling habit became the focus of internal concern early in his administration, one former Trump official said, when records personnel noticed that a range of official documents logged as going to the Oval Office or the White House residence were not being returned to be filed in accordance with White House record-keeping rules.

When staffers first started going to look for these missing records — which spanned a range of topics, including conversations with foreign leaders — they sometimes found them in a pile of ripped paper in the Oval Office or the White House residence.

But on other occasions torn documents were found in classified burn bags, which are used to dispose of documents, according to one former Trump White House official. Records personnel would routinely dump the contents of burn bags on a table and try to puzzle out which of the torn documents needed to be taped together and preserved, the former official said.

Burn bags, which resemble paper grocery bags, are available throughout the White House complex. There are two types for classified and unclassified material, and different requirements for each in determining what can be destroyed, experts said. The classified bags are marked with diagonal red stripes.

Both types of bags are ultimately destroyed, but the mechanism for how they are destroyed and safeguarded is different. There were regular “burn runs,” in which classified bags would be collected from offices and sent to the Pentagon for incineration.

Grossman said that Trump’s chaotic approach to handling physical documents leaves gaping holes in the historical record, not to mention being disrespectful to the archivists and general public.

“We don’t know how much of it was or was not successfully taped back together,” Grossman said. “Also, how much did the taxpayers pay to have a bunch of highly qualified archivists sit at a desk and tape things back together?”

Some experts also said Trump hurt his own legacy with his document destruction practices — leaving less behind for historians to examine.

“For a president to just wantonly tear things up is just a little shocking, that there’s not even a little egotistical thought about legacy,” Chartier said.

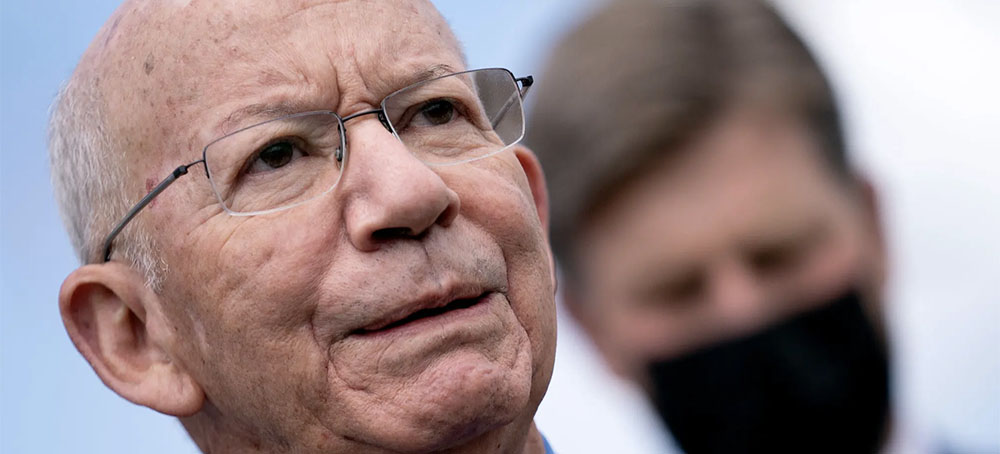

Representative Peter DeFazio, an 18-term Democrat from Oregon, decided to retire because his district is now "winnable by another Democrat." (photo: Stefani Reynolds/NYT)

Representative Peter DeFazio, an 18-term Democrat from Oregon, decided to retire because his district is now "winnable by another Democrat." (photo: Stefani Reynolds/NYT)

With two-thirds of the new boundaries set, mapmakers are on pace to draw fewer than 40 seats — out of 435 — that are considered competitive based on the 2020 presidential election results, according to a New York Times analysis of election data. Ten years ago that number was 73.

While the exact size of the battlefield is still emerging, the sharp decline of competition for House seats is the latest worrying sign of dysfunction in the American political system, which is already struggling with a scourge of misinformation and rising distrust in elections. Lack of competition in general elections can widen the ideological gulf between the parties, leading to hardened stalemates on legislation and voters’ alienation from the political process.

“The reduction of competitive seats is a tragedy,” said former Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., who is chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee. “We end up with gridlock, we end up with no progress and we end up with a population looking at our legislatures and having this feeling that nothing gets done.” He added: “This gridlock leads to cynicism about this whole process.”

Both Republicans and Democrats are responsible for adding to the tally of safe seats. Over decades, the parties have deftly used the redistricting process to create districts dominated by voters from one party or to bolster incumbents.

It’s not yet clear which party will ultimately benefit more from this year’s bumper crop of safe seats, or whether President Biden’s sagging approval ratings might endanger Democrats whose districts haven’t been considered competitive. Republicans control the mapmaking for more than twice as many districts as Democrats, leaving many in the G.O.P. to believe that the party can take back the House majority after four years of Democratic control largely by drawing favorable seats.

But Democrats have used their power to gerrymander more aggressively than expected. In New York, for example, the Democratic-controlled Legislature on Wednesday approved a map that gives the party a strong chance of flipping as many as three House seats currently held by Republicans.

That has left Republicans and Democrats essentially at a draw, with two big outstanding unknowns: Florida’s 28 seats, increasingly the subject of Republican infighting, are still unsettled and several court cases in other states could send lawmakers back to the drawing board.

“Democrats in New York are gerrymandering like the House depends on it,” said Adam Kincaid, the executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, the party’s main mapmaking organization. “Republican legislators shouldn’t be afraid to legally press their political advantage where they have control.”

New York’s new map doesn’t just set Democrats up to win more seats, it also eliminates competitive districts. In 2020, there were four districts where Mr. Biden and former President Donald J. Trump were within five percentage points. There are none in the new map. Even the reconfigured district that stretches from Republican-dominated Staten Island to Democratic neighborhoods in Brooklyn is now, at least on paper, friendly territory for Democrats.

Without that competition from outside the party, many politicians are beginning to see the biggest threat to their careers as coming from within.

“When I was a member of Congress, most members woke up concerned about a general election,” said former Representative Steve Israel of New York, who led the House Democrats’ campaign committee during the last redistricting cycle. “Now they wake up worried about a primary opponent.”

Mr. Israel, who left Congress in 2017 and now owns a bookstore on Long Island, recalled Republicans telling him they would like to vote for Democratic priorities like gun control but feared a backlash from their party’s base. House Democrats, Mr. Israel said, would like to address issues such as Social Security and Medicare reform, but understand that doing so would draw a robust primary challenge from the party’s left wing.

Republicans argue that redistricting isn’t destiny: The political climate matters, and more races will become competitive if inflation, the lingering pandemic or other issues continue to sour voters on Democratic leadership.

But the far greater number of districts drawn to be overwhelmingly safe for one party is likely to limit how many seats will flip — even in a so-called wave election.

“The parties are contributing to more and more single-party districts and taking the voters out of the equation,” said former Representative Tom Davis, who led the House Republicans’ campaign arm during the 2001 redistricting cycle. “November becomes a constitutional formality.”

In the 29 states where maps have been completed and not thrown out by courts, there are just 22 districts that either Mr. Biden or Mr. Trump won by five percentage points or less, according to data from the Brennan Center for Justice, a research institute.

By this point in the 2012 redistricting cycle, there were 44 districts defined as competitive based on the previous presidential election results. In the 1992 election, the margin between Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush was within five points in 108 congressional districts.

The phenomenon of parties using redistricting to gain an edge is as old as the republic itself, but it has escalated in recent decades with more sophisticated technology and more detailed data about voter behavior. Americans with similar political views have clustered in distinct areas — Republicans in rural and exurban areas, Democrats in cities and inner suburbs. It’s a pattern that can make it difficult to draw cohesive, competitive districts.

No state has quashed competition ahead of the midterm elections like Texas. In the 2020 election, there were 12 competitive districts in the state. After redistricting, there is only one.

Though Mr. Trump won 52 percent of the vote in Texas in 2020, Republicans are expected to win roughly 65 percent — 24 of the state’s 38 congressional seats. (Texas gained two seats in the reapportionment after the 2020 census.)

The Texas state legislators who control redistricting shored up Republican incumbents including Representatives Dan Crenshaw, Beth Van Duyne and Michael McCaul, but in doing so also drew safer districts for Democrats such as Representatives Colin Allred and Lizzie Fletcher.

“The fact that it’s going to be harder for us to pick up congressional seats is a big concern,” said Gilberto Hinojosa, chair of the Texas Democratic Party. “That doesn’t mean that we think that it’s not important to mount challengers, it’s just a reality that it’s going to be harder.”

Democrats did the same where they could. Oregon legislators took the state’s competitive Fourth District and turned it into a seat that strongly favors their party.

The change was so dramatic that Representative Peter DeFazio, an 18-term Democrat, told reporters last year that he chose to retire because the district is now “winnable by another Democrat.”

Redrawing Mr. DeFazio’s district enraged Oregon Republicans.

“Competitive districts benefit all of us,” said Shelly Boshart Davis, an Oregon state representative who was the former Republican co-chairwoman of the state House’s redistricting committee. “We hear voters that feel marginalized all the time, that say, ‘I don’t feel my voice gets heard.’”

A lack of competition has unintended consequences. Without a competitive race at the congressional level, local parties are deprived of an infusion of money and organizing. Candidates for governor or Senate don’t benefit from being able to piggyback on the energy and activity at the local level.

“Anybody running statewide has to pull the wagon entirely themselves because you don’t have competitive races going on locally,” said Matt Angle, a Democratic activist in Texas.

It can sometimes take years to see the full impact of eliminating a competitive district.

Ten years ago, North Carolina Republicans took a battleground district in the state’s western tip and, by slicing off a piece of the liberal city of Asheville, turned it into a district that John McCain would have carried by 18 points in the 2008 presidential election. The incumbent centrist Democrat, Heath Shuler, retired rather than seek re-election in a district he had little shot at winning.

He was replaced by Mark Meadows, who went on to be a founding member of the right-wing House Freedom Caucus before becoming the last White House chief of staff for Mr. Trump and a central figure in Mr. Trump’s campaign to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

The post ‘Taking the Voters Out of the Equation’: How the Parties Are Killing Competition appeared first on New York Times.

Joe Rogan, July 2016. (photo: Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

Joe Rogan, July 2016. (photo: Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

The podcaster, whose series The Joe Rogan Experience is one of the platform’s most popular podcasts, has come under fire for promoting the spread of Covid-19 “misinformation”.

Musician Neil Young led a boycott of the service, which has since seen his music, alongside Joni Mitchell’s, Graham Nash’s and India Arie’s, taken down.

While Young, Mitchell and Nash criticised Rogan for promoting “misinformation”, Arie said that her decision stemmed from the “problematic” Rogan’s “language around race”.

The Grammy Award-winning musician elaborated by saying her request was inspired by Rogan’s repeated use of the N-word in old podcast episodes.

After the musician shared a compilation of the podcaster using the racial slur, the podcaster faced renewed criticism, and issued an apology on Instagram, telling his followers: “There’s nothing I can do to take that back – I wish I could.”

Despite Young’s initial ultimatum, Spotify has remained loyal to Rogan, who has a $100m deal with the platform. However, the platform said it would add Covid-19 content advisory labels in response to the backlash. Rogan has supported this move.

Now, though, JRE Missing – a website that automatically detects deleted episodes of podcasts – has found that Spotify has quietly removed 113 episodes of Rogan’s podcast.

Deleted episodes include ones featuring far-right commentators, including Alex Jones, and former Breitbart editor Milo Yiannopoulos.

Jones was banned by Spotify for creating “hate content”, although it permitted Rogan to have him as a guest on his show. The episode has now been deleted.

Last month, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle also revealed they had “expressed concerns” to Spotify, with whom they have a deal worth a reported $18m (£13.3m), about the spreading of “disinformation”.

In the wake of this statement, an old episode in which Rogan shared his candid views on Meghan Markle and Prince Harry, resurfaced online.

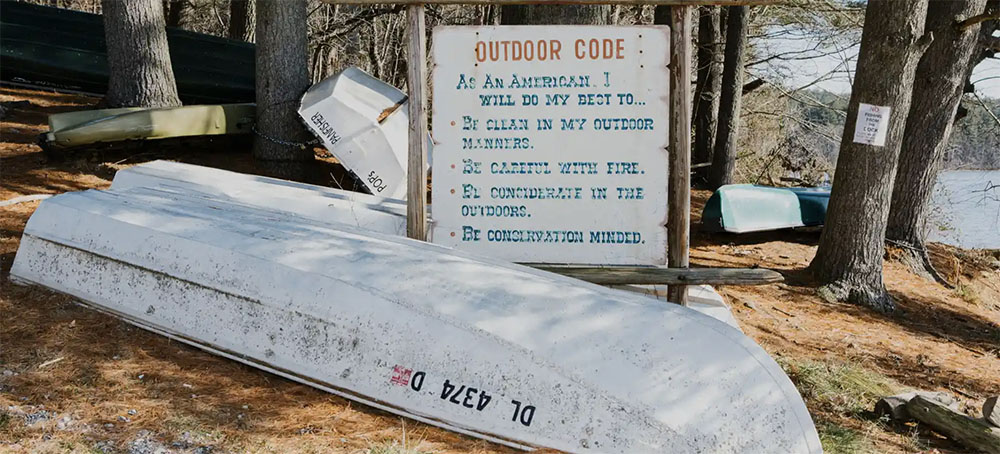

Recreational boats and a sign for the 'outdoor code' at the shoreline of the Octoraro reservoir. (photo: Guardian UK)

Recreational boats and a sign for the 'outdoor code' at the shoreline of the Octoraro reservoir. (photo: Guardian UK)

Corporations are trying to privatize dozens of public water utilities around the US, capitalizing on the financial troubles of cities

“No to Big Water”, the signs say, and “Save CWA”.

The signs show the local opposition to a hostile takeover effort by Aqua Water, one of the country’s biggest private water companies, against the public utility Chester Water Authority (CWA), which owns the reservoir and bordering woodland.

The CWA relies on the watershed to provide drinking water to about 200,000 people in Delaware and Chester counties. It’s an award-winning public utility that is financially robust and delivers safe, clean and affordable water. It does not need a bailout.

Campaigners say the battle here, which started in 2017, should be a wake-up call for residents around the US, as privatization often means higher bills.

“This takeover is about putting money over people’s needs – it’s corporate greed,” said Delaware county resident Santo Mazzeo, 42, a high school maths teacher with three children working two jobs to make ends meet.

“Water is the stuff of life, it’s a fundamental human right which should be run by the people for the people, not for profits,” added Mazzeo, who in his spare time delivers the anti-takeover signs to neighbours.

But CWA is vulnerable because the sale could help rescue one small city in Delaware county on the brink of bankruptcy.

Private companies mostly target financially distressed local governments and utilities looking for cash injections to clear debts, upgrade infrastructure or fund popular public services without raising taxes. Industry friendly laws means this often comes at a cost for residents: nationwide, one in 10 people currently depend on private water companies, whose bills are on average almost 60% higher than those supplied by public utilities.

In Pennsylvania, Aqua already owns numerous utilities and its most recent rates proposal would, if approved by the state regulator, lead to almost half a million households paying on average 17% more for their drinking water than they currently pay. Wastewater bills would rise by 33%.

CWA warns that the Aqua deal could cost its customers more than $1bn in higher bills over the next 20 years – and threatens public access to the reservoir and its landholdings, 2,000 acres that protects the watershed and wildlife.

“We pride ourselves on providing quality water that our residents can afford. We’re not in any trouble, and we’re the best custodians of this precious natural resource because we don’t have to worry about shareholders or dividends,” said Cindy Leitzell, chair of the CWA board.

Nationwide, dozens of new privatisation deals are under consideration, according to Global Water Intelligence, with 14 major acquisitions (each worth at least $10m) pending across five states, with a combined value of almost $800m, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

“For more than a decade, these corporations have waged a successful lobbying campaign to support state laws that facilitate privatisation and ensuing water rate hikes…. the public must be on the guard to protect their essential water services from the corporate vultures trying to exploit fiscal distress,” said Mary Grant, the right to water campaign director at Food and Water Watch (FWW).

Analysis by FWW of four of Aqua’s largest Pennsylvania acquisitions found rates increased by an average of 280% – the equivalent of 8% per year – after adjusting for inflation.

“Water corporations have become increasingly aggressive and even the best-run water systems like CWA are under attack, which should sound the alarms for communities nationwide,” Grant said.

‘First class operation’

Federal funding for water systems peaked in 1977, and since then municipal utilities have mostly depended on rate hikes and credit to fund infrastructure upgrades, water safety mandates and climate adaptation. As a result, the cost of water and sewage has risen sharply over the past decade or so, making this basic service an increasing burden for many Americans, a Guardian investigation found.

Still, the funding shortfall remains gob smacking, which has been further exacerbated by billions of dollars in unpaid bills during the pandemic.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, drinking water, wastewater and stormwater systems need at least $744bn over the next 20 years just to comply with existing federal law. An additional $1tn is required by 2050 to protect water infrastructure from extreme weather events and sea level rise linked to global heating, according to the National Association of Clean Water Agencies.

But CWA is not struggling. Its well-planned upgrades – such as building a new pump station on higher ground to avoid flooding and a multimillion dollar state of the art leak detection system – have helped avoid unexpected costs and catastrophes. CWA recently increased its rates for the first time since 2010.

“This is a first class operation which is not financially stressed in any shape or form because we’ve always looked ahead and don’t answer to shareholders. Quality and quantity are problems in this industry, but we have both, which makes us a prize that Aqua wants,” said Paul Andriole, CWA’s vice-chair.

At its water treatment plant, where a dozen or more awards are displayed in the lobby, 60m gallons of water drawn from the reservoir and Susquehanna river are processed every day. It’s a 24/7 operation with an in-house laboratory to aid compliance with environmental standards.

“We meet or exceed EPA standards, we do not have quality or safety violations that could justify our sale. It’s a struggle but we can handle it,” said Anita Martin, chief lab technician.

Should CWA save Chester from bankruptcy?

CWA was created by the city of Chester – Pennsylvania’s oldest city and a former industrial powerhouse which has experienced significant economic and population decline since the mid 20th century.

The majority Black city is an environmental justice hotspot: its 32,000 or so residents are burdened with poor air quality caused by heavy industries including the country’s largest trash incinerator, and have limited access to green spaces and healthy affordable groceries.

The city of Chester has been subject to state financial oversight since the mid-1990s due to mounting debts and inflated police pensions, but was pushed to the brink of bankruptcy in 2020 after a major revenue stream, the casino, was closed due to Covid.

A large cash injection – along with reducing retiree benefits – is crucial to making the city solvent, according to Michael Doweary, the court-appointed receiver. “This is a difficult situation but CWA is the city’s only asset large enough to generate enough money to meet its debt obligation and reinvest in the city, which for years has been on a shoestring budget.”

But, critics say the sale would hurt city residents, about a third of whom live in poverty.

Based on Aqua’s proposed statewide rate increase for its existing customers, Chester city residents could be saddled with bills more than double what they pay now, according to a comparison tool devised by CWA. The average water bill burden would be 3.3% of median household income, a level generally deemed unaffordable by the UN. (The mayor has said some of the sale money could be used to offset rate increases for a decade.)

Kearni Warren, 45, an energy justice organiser who lives in Chester, said: “We don’t have clean air, green spaces or healthy food options, but affordable clean water is the one healthy thing we do have, and the city wants to sell it off… It will harm residents and thousands of ratepayers outside the city.”

Chester city created CWA but the vast majority (81%) of its customers now live outside city boundaries – in the suburbs of Chester and Delaware counties which have separate local governments. Given this, the city’s right to sell CWA has been contested.

Last September an appeals court ruled that the fate of CWA rested in the hands of the city, as it created the utility. CWA lodged an appeal to the Pennsylvania supreme court.

In an amicus brief supporting the appeal, FWW argues that Aqua’s actions constitute a hostile takeover, and that CWA should be treated as a public trust responsible for managing water supplies for the benefit of the people, not as a commodity.

Why do private water customers pay more?

In 2016, Pennsylvania became the first state to pass legislation that allows private companies to buy public utilities for more than they are worth – relying on what’s known as fair market value rather than depreciated value. Companies can recoup the over-priced investments by passing on the cost to all their customers through statewide rate hikes, meaning residents pay while shareholders reap the rewards.

The law led to a merger frenzy in Pennsylvania and at least 11 states have since passed similar laws, driving up water and wastewater bills, according to the Government Accountability Office. In some states, healthy public utilities – not just those in financial trouble – are eligible for takeover.

In Pennsylvania, a third of residents are served by private water companies – triple the national average – and their bills are on average 84% more than those with public providers.

In 2017, a year after the fair market law (Act 12) was passed, Aqua made an unsolicited bid to CWA for $320m – which the nine-person board unanimously rejected after concluding there would be no benefit to its residents.

As Aqua persisted, in 2019 CWA made a counter offer worth $60m to help bail out the city in exchange for protection from future hostile bids. Aqua filed a lawsuit to stop the deal.

There are now three offers on the table, including $410m from Aqua – the second highest but city’s preferred bid, which includes a $12m advance irrespective of the litigation outcome. Michael Doweary, Chester city’s court appointed receiver, said his team is exploring ways to keep the water authority in public hands, but CWA’s $60m bid isn’t enough. (Aqua’s rival, Pennsylvania American Water, has bid $425m.)

With more than a dozen pending lawsuits, the case could be tied up in court for years. If sold, it would be up to the court to determine the city’s share of the proceeds.

Aqua is now a subsidiary of Essential Utilities, the second largest publicly traded US water and wastewater corporation, currently valued at $12.5bn.

It provides drinking water and wastewater to about 3.25 million people (1m households) in eight states, with over half in Pennsylvania, where the company is headquartered and has close ties to the state government.

Aqua has at least half a dozen new deals pending regulatory approval in the state. In addition, the Guardian understands that the company has approached Bucks county’s water and sewer authority (BCWSA), another robust public utility, about a possible $1bn offer, which would be among the biggest water privatisation deals in US history, affecting half a million residents. (Aqua said it has not made a bid; the county commissioner office and BCWSA declined to comment.)

In a statement, Aqua said its actions related to CWA did not amount to a hostile takeover and that it was committed to keeping the reservoir open to the public. It said that public utilities like CWA are unregulated and typically untransparent about rates and capital investments. “Aqua’s rates reflect its true cost of service, which includes investments necessary to provide high quality service, safe working conditions and protection of the environment. Lower rates often indicate deferred maintenance and old, outdated facilities, which can lead to service interruptions and water quality and wastewater discharge violations.”

New Garden Township is a scenic rural area in Chester county with well-to-do families, retirement villages and migrant communities concentrated around multiple mushroom farms.

Its wastewater system, which supplies about half the township’s residents, was Aqua’s first in the state after the fair market law changes – in a deal worth $29m. Some of the money was used to build a new police station and offset future tax increases.

If Aqua’s rate hike is approved by the regulator, residents will see average wastewater bills rise by approximately 37% later this year – much higher than the rate cap promised during initial negotiations. This has generated anger and mistrust among residents opposed to the takeover. Going forward, residents will probably share the cost of Aqua’s future acquisitions – including CWA, the community’s water provider.

Margo Woodacre, 72, a retired social worker and part-time English teacher, said: “It’s the dishonesty and unfairness that’s made me go door to door educating businesses and residents, so they know what’s coming if we lose CWA.”

The Washington Commanders have a new name and new uniforms. (photo: Jonathan Newton/WP)

The Washington Commanders have a new name and new uniforms. (photo: Jonathan Newton/WP)

The NFL franchise unveiled its new name, logo and uniforms on Wednesday, more than 18 months after it dropped its former name of 87 years. The "Washington Redskins," as the team was formerly known, is offensive to many Indigenous people who viewed the name and branding as both a slur and a disparaging stereotype grounded in America's history of violence against Native peoples.

Suzan Harjo, a 76-year-old advocate central to the fight to change the team's name, called the change "a huge step forward."

For Harjo, it was a victory that came after decades of disappointment. When owner Daniel Snyder announced in 2020 the team's plans to change its name after yielding to corporate pressure, she didn't hold her breath. She'd seen many hopeful signs since her efforts to change derogatory team and school names began in the 1960s, but progress was long elusive.

In 2009, she watched as the Supreme Court declined to consider her petition to resolve a years-long legal challenge to the name that lower courts had dismissed on a legal technicality. Even when then-President Obama weighed in on the issue and said he would "think about changing" the name if he owned the team, Snyder didn't budge.

"You could be glib about it and say, well, you know, look how long it took," she said, "but at bottom, it is remarkable."

And it's one she says represents a societal sea change.

"A lot of people now get it," she said. "That it's not all right to use disparaging terms, derogatory names, slurs, images, behaviors."

The name has brought deep pain for Native Americans

In her experience, the "R-word," as Harjo calls it, is inseparable from harmful, racist attitudes that have translated into "emotional and physical violence" against Native Americans.

"If it's permissible to say such things to us, such names, then it is permissible to do anything to us," she said.

"I had lots of things in my personal life using that word," said Harjo, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. "When I was a girl, you barely could make it through your young life without getting attacked by a bunch of white people — whether they were boys or girls or men or women. And they would always go to that word."

The origin of the term has long been debated by linguists and historians. Some say "redskin" didn't start out as an insult. But to many Native Americans, Harjo among them, the word refers to the grotesque act of hunting down and skinning their ancestors' scalps for cash bounties.

A tipping point came amid protests for racial justice

Snyder had ignored years of advocacy and litigation from Native American activists in pushing for the change, saying that his team's name was a "badge of honor" that respected a long tradition. But in 2020, the tipping point arrived. The murder of George Floyd sparked a moment of racial reckoning in America that drove FedEx, the team's title sponsor, to threaten to sever its ties with the team unless it changed its name.

At no point during the conversations around selecting a new name, did the NFL team consult the National Congress of American Indians, after such commitments had been made to include the organization's leaders in the process, according to NCAI president Fawn Sharp.

The Washington Commanders have not responded to a request for comment about their name-change process.

Hundreds of teams still use disparaging names

Sharp, like the rest of the public, learned of the new team name when it was announced last week. And she thinks the "Commanders" moniker is on brand.

"It seems right in line with how they are relating to tribal nations," said Sharp, who is also vice president of the Quinault Indian Nation in Washington state. "On the one hand, saying they're going to be inclusive. But on the other hand, making this [change] with not one meeting with us, as promised — it's definitely taking a command role."

Even so, she says the formal name change marks "the end of a dark era." It means younger generations will no longer walk into a stadium in the nation's capital that "exploits some of our most sacred practices," Sharp said.

Still, she knows the movement isn't over given that hundreds of teams across high school, college and professional sports continue to make use of disparaging names, mascots or logos referencing Native Americans.

But Harjo thinks it's only a matter of time before more professional sports teams follow suit — namely the Atlanta Braves, Kansas City Chiefs and the Chicago Blackhawks.

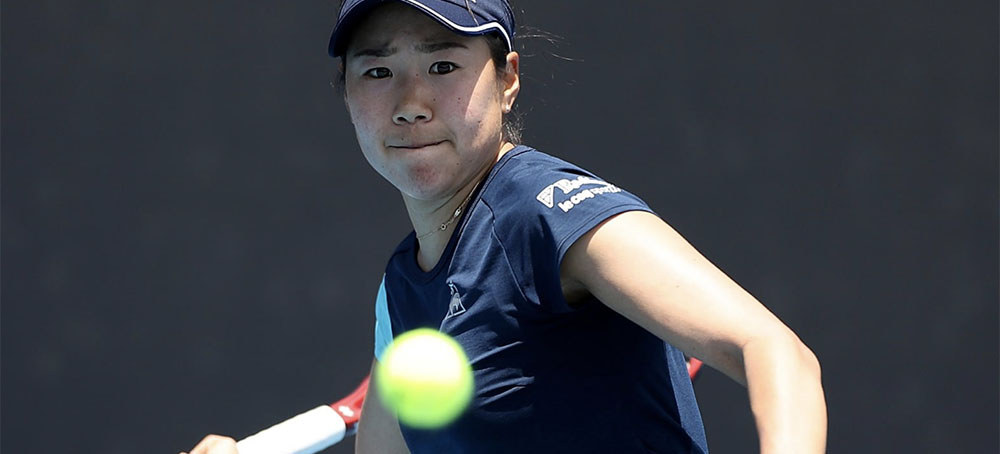

Tennis star Peng Shuai. (photo: Mark Kolbe/Getty Images)

Tennis star Peng Shuai. (photo: Mark Kolbe/Getty Images)

The Chinese tennis star gave an interview to a French newspaper that is unlikely to quell concern for her welfare.

The IOC, which has been heavily criticized for its seeming blindness to China’s human-rights abuses, and its apparent censuring of Peng, released as statement without saying whether Peng was accompanied by her usual Chinese government handlers, though IOC Director of Communications Mark Adams on Monday said the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (BOCOG) were not informed of the meeting.

“During the dinner, the three spoke about their common experience as athletes at the Olympic Games, and Peng Shuai spoke of her disappointment at not being able to qualify for the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020,” the IOC statement said, without mentioning why they met.

The two-time Olympian had earlier given an interview—with a government official at her side—denying she was sexually assaulted by a powerful politician.

“I would like to know: Why such concern?” the 36-year-old athlete said of worries that she was essentially forced from public view after posting an accusation on the Chinese social media platform Weibo.

Peng’s comments to French newspaper L’Equipe are unlikely to quell concern that she is not free to speak her mind. A member of China’s Olympic committee was with the doubles champion as she spoke from a hotel room in Beijing.

Fears over Peng’s welfare have swirled since her November post about a former Chinese vice premier. The World Tennis Association suspended tournaments in China, saying Peng was being censored.

“That afternoon, I was very afraid. I didn’t expect it to be like this,” she wrote in the post. “I didn’t agree to have sex with you and kept crying that afternoon.”

In the interview with L’Equipe, Peng said her post had been misinterpreted.

“I never said anyone had sexually assaulted me in any way,” she said, claiming that she—and not the government—had deleted the Weibo message.

She also declared that too big a deal was being made of her withdrawal from public view.

“I never disappeared. It’s just that a lot of people, like my friends, including from the IOC, messaged me, and it was quite impossible to reply to so many messages,” she said, according to a translation by the Sydney Morning Herald.

“But with my close friends, I always remained in close contact. I discussed with them, answered their emails, I also discussed with the WTA. But, at the end of the year, their website’s communication computer was changed and many players had difficulty logging in at that time.

“But we always kept in touch with colleagues. That’s why I don’t know why the information that I had disappeared spread.”

Peng reportedly met this weekend with International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach.

Big sugar. (image: Alex Bandoni/Greg Lovett/Krisanapong Detraphiphat/ProPublica/Hill Street Studios/Getty Images/The Palm Beach Post)

Big sugar. (image: Alex Bandoni/Greg Lovett/Krisanapong Detraphiphat/ProPublica/Hill Street Studios/Getty Images/The Palm Beach Post)

A city commissioner race in Florida provides a window into how the sugar industry cultivates political allies, who help protect its interests.

Supporters argued that the legislation was critical to protecting Florida’s agricultural businesses from “frivolous lawsuits.” But some lawmakers were skeptical, noting that residents of the state’s heartland who were bringing suit against sugar companies would feel their case anything but frivolous. At issue was the practice of cane burning, a harvesting method in which the sugar industry burns crops to rid the plants of their outer leaves. Florida produces more than half of America’s cane sugar and relies heavily on the technique, but residents in the largely Black and Hispanic communities nearby claim the resulting smoke and ash harms their health.

So, on a Wednesday morning in March, lawmakers heard testimony on the new bill. In a committee room in Tallahassee, Joaquin Almazan stepped to the microphone as a newly elected city commissioner in Belle Glade, the largest city in the sugar-rich Glades region, where the smoke drops “black snow” on residents throughout every burning season.

Almazan had won his seat just one week before the hearing. His victory was also a victory for the sugar industry, a political powerhouse that employs more than 12,000 workers in the area during harvest season. His rival, Steve Messam, opposed cane burning and sought to end the practice.

In a small town of 8,000 voters where political campaigns are generally sleepy, the contest emerged as the marquee race in an election for three seats on the city commission, contributing to record turnout and fueling big spending. In fact, each side raised more than $16,000, making the March election the most expensive in at least 15 years, according to an analysis of campaign finance records by The Palm Beach Post and ProPublica, which examined documents going back to 2006. That’s five times the amount of money typically raised by city commissioner candidates, after adjusting for inflation. While Messam relied on mostly small donations from more than 200 donors, Almazan tapped a much smaller pool of 40 contributors, with much of his campaign money coming from sugar and farming interests.

Those industry donors were among more than two dozen entities that gave identical amounts to candidates running for the two other city commission seats. Like Almazan, the two favored contenders in those races supported the sugar industry’s methods, saying that ending cane burning would lead to devastating job losses.

At the same time, political action committees aligned with the industry spent thousands of additional dollars to influence the election, with one group promoting business-friendly candidates and another attacking Messam.

The local campaign, which was underway while major legislation was pending before the state Legislature, provides a window onto how the industry cultivates political allies in the Glades who, in turn, help protect its interests in Tallahassee.

“A voice that is for or against the ag industry is 10 times more powerful coming from the Glades area than someone who is from outside the local area,” said Rick Asnani, a West Palm Beach-based political consultant, explaining the industry’s investment in local elections. “It is absolutely appropriate and logical that an industry is going to protect their industry, their reputation and their backyard.”

And indeed, once elected, Almazan emphasized his lifelong residence in the Glades when he asked lawmakers to support the bill.

“It’s sad, as we’ve seen too many times previously: Wealthy, out-of-town, so-called environment special interest groups are claiming to know what’s best for our community,” he told lawmakers. “In fact, they repeatedly argue against our city, our best interests, and repeatedly advocate for other solutions that will only bring us economic destruction, unemployment and food insecurity, and shutter local businesses.”

His testimony and that of other elected officials and residents in the Glades in support of the legislation would lead several Democrats to withdraw their objections, and the proposal sailed through the Legislature.

In response to questions for this story, Almazan said his run for office — and his testimony — were a natural extension of his advocacy as a member of the International Association of Machinists, a union representing sugar workers. “The union encourages its members to rise to challenges,” he said in a statement, “and I felt that by running for the City Commission I could do that.”

Asked about the donations from the agricultural industry, he said they’d been given because “I support similar interest, Community, workers and jobs.”

Now, nine months later, some Democratic lawmakers want to roll back last year’s key changes, which were aimed at barring so-called nuisance lawsuits against farmers. Under the state’s Right to Farm law, certain farming activities are protected from legal action, and the legislation added “particle emissions” to the list. The term is interchangeable with particulate matter, a known byproduct of cane burning and a type of pollution tied to heart and lung disease. Last month, state Rep. Anna Eskamani and state Sen. Gary Farmer introduced legislation to strike that language, hoping to bolster residents’ ability to sue.

It’s a reflection of the views of some Glades residents and environmental groups, who have battled the sugar industry for years over burning crops. They argue that the resulting smoke and ash harms their health — a claim that the sugar companies deny. Last year, The Post and ProPublica deployed their own air monitors to produce a first-of-its-kind investigation into cane burning. The readings showed repeated spikes in pollution on days when the state had authorized cane burning and smoke was projected to blow toward the sensors. These short-term spikes often reached four times the average pollution levels in the area. Experts said the results highlighted a need for more scrutiny from government agencies, which have access to better equipment and data.

The news organizations also found that in 2016, the state health department’s own researchers recommended deeper study of the potential health effects of cane burning on Glades residents, after finding that the burns release toxic air pollutants. Six years later, the department has yet to produce such a study and has not responded to questions about why.

In the Glades, the opposition to cane burning crystallized in 2015 into a “Stop the Burn” campaign, which was backed by the Sierra Club. The campaign involved rallies to press the industry to use an alternative method of cane harvesting that doesn’t involve fire. But the group’s events rarely amounted to more than a ripple in the state’s political landscape, where sugar companies are among the largest donors.

The “Stop the Burn” campaign’s claims drew attention when Messam, one of the group’s leaders, filed to run for an open seat on the Belle Glade city commission. He was born in the nearby town of Pahokee and grew up in the region, the son of Jamaican immigrants. His father worked in the sugar fields, cutting down cane by hand for 75 cents a row, he said.

When Messam left to attend Central Michigan University on a football scholarship, he said his teachers thought he had asthma because his breathing sounded difficult. His symptoms abated over time in Michigan. But when he returned home on Christmas break, during cane-burning season, “my allergies went haywire,” he later told supporters in a Facebook Live video on his campaign page. “At the time, I didn’t make the connection.”

In 2015, Messam and his family moved to Belle Glade from Greenacres, a city closer to the more populous part of Palm Beach County, east of the cane fields. He was working nearby as a senior vice president of his brother’s construction company, Messam Construction, and serving as a pastor at First Church of God South Bay. Before long, his wife, LoMiekia, who also grew up in the region but had spent much of the prior decade living outside Florida, started to get respiratory tract infections and their young son, Noah, developed allergies and needed a nebulizer to help him breathe. Doctors advised them to move, LoMiekia said in the video.

Messam said he reached out to the Sierra Club to learn more about what activists call “green harvesting,” in which sugar cane is harvested without burning. Harvesters cut the cane with the leaves still attached and separate them from the sugar-rich stalks. Some of the world’s leading sugar-producing nations, including Brazil, India and Thailand, have embraced this method as they move to end or sharply limit cane burning. Florida’s sugar companies, however, maintain that burning is safe and heavily regulated, and that it cannot be changed without significant economic impact.

In running for city commissioner, Messam saw a different future for Belle Glade. Switching to green harvesting in Florida would “be a win-win for the environment and the economy,” Messam said. While he understood that local officials have little power to regulate farming — those decisions are made at the state level — he knew that local voices carry weight in Tallahassee.

Relying on mostly small contributions, Messam raised a total of more than $16,000 from more than 200 donors. The Sierra Club’s political action committee in Florida made a $500 donation, and some of the group’s local supporters and a plaintiff in the sugar cane burning lawsuit also pitched in. Educators made up much of the campaign haul. His brother’s company contributed $1,000, the maximum under state law.

By contrast, his opponent in the race, Almazan, opposed the “Stop the Burn” effort and tapped his connections in labor circles and the agricultural sector.

In addition to being a member of the machinists union, he’s also the community action director of the Sugar Industry Labor Management Committee, a political organization that advocates for the union and local sugar companies, according to the union website. “Of course jobs in the sugar industry are important to me,” he said in an email to The Post, highlighting his union membership. “My dad retired from the sugar industry after 35 years and was proud to have raised his family here. I’m proud to have spent more than 30 years in the industry. My son is also building his career here.”

The sugar and agriculture industries also backed two other city commissioner candidates running for separate seats: Bishop Andrew “Kenny” Berry of Grace Fellowship Worship Center and incumbent Vice Mayor Mary Ross Wilkerson, who was first elected in 1998.

In 2018, candidates for city commission had raised about $3,200 each on average. The three industry-backed candidates in the 2021 race, however, each raised more than $15,000. The vast majority of each campaign’s funds — $13,100 — came from the same 28 individuals, committees and businesses, according to a Post/ProPublica analysis. Agriculture interests represented the single largest pool of money, making up about 40% of these contributions. Among them were the Sugar Cane Growers Co-Op; the Palm Beach Farm PAC, run by farmer and state Rep. Rick Roth, a co-introducer of last year’s legislation; and Hundley Farms, a grower in the Glades that produces sugar cane.

Some locals, including an incumbent facing an industry-backed challenger, took note of the heightened political activity in Belle Glade.

“I’ve never seen the sugar industry involved in any of the political affairs, when it came to campaigns and elections, like this time around here. Period,” said then-City Commissioner Johnny Burroughs Jr., speaking to voters in a Facebook Live video the night before the election. His campaign was struggling as industry allies supported his rival.

Asked about the industry donations, Almazan said in a statement, “I’m very thankful for the endorsements I received from major unions including the Palm-Beach Treasure Coast AFL-CIO and the Firefighters as well as support from family, friends, neighbors, local businesses and farmers who together are the backbone of our community.”

Berry and Wilkerson, the other two candidates who received significant contributions from sugar and agriculture groups, did not respond to a request for comment on their campaign donations.

According to campaign finance records, neither U.S. Sugar nor Florida Crystals, the state’s largest sugar producers, played a direct role in the election. But their allies did.

As the campaign progressed, Glades Together, a local political action committee, distributed voter guides and fliers promoting Almazan, along with the two other industry-backed candidates. The literature did not mention cane burning, instead emphasizing the local economy. “Our jobs and our future,” one flier read. “Do your part to protect ag jobs.”

The organization was formed by Sherrie Dulany, a former Belle Glade City Commissioner and school teacher. “When it became clear that outside organizations such as the Sierra Club were getting involved in our local election, we organized an effort to promote unity and our local economy,” Dulany told The Post and ProPublica in an email.

The sole source of the group’s funding during the election was Liberate Florida, a statewide political action committee financed largely by other PACs, including Florida Prosperity Fund. Among the latter group’s top donors is U.S. Sugar, which gave $75,000 in February, just as the Belle Glade election was heating up.

Meanwhile, a group called Urban Action Fund launched mailers targeting Messam. Like Glades Together, the group received funding from a political action committee with ties to Florida Prosperity Fund. The mail pieces didn’t mention sugar or cane burning but used black-and-white photos of Messam at “Stop the Burn” events.

“Steve Messam is part of the Sierra Club!” said one mailer. “We don’t need Steve Messam and outsiders who want to see our jobs and us go!”

“The Sierra Club’s job killing plan will hurt Glades families,” another mailer warned, leaving unsaid what the plan was or how it would impact the local economy. “Unemployment will make crime worse and hurt social services.”

John T. Fox, who chaired Urban Action Fund until it closed on Oct. 12, did not respond to an inquiry from The Post and ProPublica. The news organizations also sought comment from Florida Prosperity Fund’s chair, Brewster Bevis, who also serves as the president and CEO of Associated Industries of Florida, a group representing business interests in the capital. A spokesperson said the organization “does not discuss political activity.”

The attacks grated on Messam. And on March 7, two nights before the election, he logged on to Facebook Live to address them. For an hour, he went point by point, rebutting what he called a “smear campaign.” More than 1,000 people watched.

Messam argued that green harvesting would create jobs and a new industry to convert sugar cane waste into new products. Sugar companies in the Glades do use leftover sugar cane fiber to make biodegradable paper plates and take-out containers, though industry allies argue there is no large-scale commercial use for the leaf material, the part of the plant that is burned. Producers in Brazil, however, have found ways to use this material as a source of renewable energy.

On election day, Almazan won, taking 60% of the vote. When asked about their role in the election, both U.S. Sugar and Florida Crystals pointed to their efforts to encourage their employees to vote.

U.S. Sugar did not respond to questions about its donation to Florida Prosperity Fund, but company executive Judy Clayton Sanchez did offer a general statement on the election. “Glades residents elected three qualified candidates who have a track record of leadership in our community,” she said. “Elected candidates were full-time local residents with our communities’ best interest at heart and a history of protecting our rural way of life — not outsiders being influenced, directed and/or paid by out-of-town activists’ groups with anti-farming agendas.”

“While disappointing, it is not surprising that The Palm Beach Post would publish a story that challenges the validity of a fair and democratic election,” Florida Crystals said in a statement about this story. “The Palm Beach Post is not only attempting to undermine a free, fair and accessible election but also to harm the reputations of three highly regarded Glades leaders, the consequence of which will be a chilling effect on future leaders who will rethink entering public service.”

In the weeks after the election, agricultural and environmental groups pressed their cases in Tallahassee.

But, as the bill to protect farmers from lawsuits moved forward, former Pahokee Mayor Colin Walkes, who is on the leadership team of the Sierra Club’s “Stop The Burn” campaign, pushed back on assertions like Almazan’s — that outsiders were getting involved. He told lawmakers that locals were driving the anti-burn efforts.

“I want to dispel the myth that we, the locals who are opposed to the bill, are opposed to our industry,” Walkes said during a March 30 hearing. “We want to make sure that our industry thrives, but we want to ensure that we are taking care of the people that help the industry to thrive.”

On April 15, as lawmakers gave the legislation its last committee hearing, Almazan and his fellow elected officials from the Glades visited the state Capitol again. They were bused in by a group tied to the Belle Glade Chamber of Commerce. Belle Glade Mayor Steve Wilson led the charge.

Not passing the Right to Farm Act changes, Wilson claimed, would decimate the Glades.

Farming and the sugar industry are “key to the Glades community,” he said. “It’s our No. 1 economic engine. And if you stop that, trust me, you stop the community, a striving community.”

Wilson continued: “Do you think the people in the Glades are that naive, they will put themselves, their family members, their children at risk for the sake of industry or politicians?”

Almazan agreed.

“I’ve lived all around our sugar fields, and my son’s out there,” he told lawmakers. “I wouldn’t raise my kids to be in a bad environment if I thought it was unhealthy. I would have been moved out of there a long time ago.”

Rep. Ramon Alexander, a Democrat from Tallahassee, had already voted against the bill in an earlier committee meeting, but changed his second vote to a “yes.” He noted that the locals supported the changes.

“On one end, we’re talking about the environment, which is important. On the other hand, we’re talking about grits, eggs, bacon and collard greens,” Alexander said. “My point is they are in that community, and this is their way. If you don’t work, you don’t eat, and I’m not going to take grits, eggs, bacon and collard greens off of somebody else’s table.”

Two of his Democratic colleagues also withdrew their objections after listening to the testimony.

“I came in this morning with a ‘no’ vote,” said Rep. Dianne Hart, a Democrat from Tampa, who noted the opposition from environmentalists. “However, I cannot in good conscience tell you what’s best for your community.” She later told the news organizations that she felt it was important to defer to the opinions of people like Almazan who live in the community.

At the hearing, Rep. Mike Gottlieb, a Democrat from Davie, agreed.

“I’ve been sitting here on my phone looking at environmental studies and particulate matter and so on and so forth,” he said, “but when you hear the testimony of the people who are living there and working there for 40 years … they’re not telling us about horrible environmental hazards that are causing death or premature death or breathing issues.”

He then addressed the bill’s sponsor: “I was a ‘no’ as I walked in here today, but hearing you and hearing the people who testified on behalf of your bill, I’m up today.”

A week later, the bill went to a vote in the House, which joined the Senate in passing the measure. The overall tally: 147-8.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment