Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Business leaders like JP Morgan and Irénée du Pont were accused by a retired major general of plotting to install a fascist dictator

America had hit rock bottom, beginning with the stock market crash three years earlier. Unemployment was at 16 million and rising. Farm foreclosures exceeded half a million. More than five thousand banks had failed, and hundreds of thousands of families had lost their homes. Financial capitalists had bilked millions of customers and rigged the market. There were no government safety nets – no unemployment insurance, minimum wage, social security or Medicare.

Economic despair gave rise to panic and unrest, and political firebrands and white supremacists eagerly fanned the paranoia of socialism, global conspiracies and threats from within the country. Populists Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin attacked FDR, spewing vitriolic anti-Jewish, pro-fascist refrains and brandishing the “America first” slogan coined by media magnate William Randolph Hearst.

On 4 March 1933, more than 100,000 people had gathered on the east side of the US Capitol for Roosevelt’s inauguration. The atmosphere was slate gray and ominous, the sky suggesting a calm before the storm. That morning, rioting was expected in cities throughout the nation, prompting predictions of a violent revolution. Army machine guns and sharpshooters were placed at strategic locations along the route. Not since the civil war had Washington been so fortified, with armed police guarding federal buildings.

FDR thought government in a civilized society had an obligation to abolish poverty, reduce unemployment, and redistribute wealth. Roosevelt’s bold New Deal experiments inflamed the upper class, provoking a backlash from the nation’s most powerful bankers, industrialists and Wall Street brokers, who thought the policy was not only radical but revolutionary. Worried about losing their personal fortunes to runaway government spending, this fertile field of loathing led to the “traitor to his class” epithet for FDR. “What that fellow Roosevelt needs is a 38-caliber revolver right at the back of his head,” a respectable citizen said at a Washington dinner party.

In a climate of conspiracies and intrigues, and against the backdrop of charismatic dictators in the world such as Hitler and Mussolini, the sparks of anti-Rooseveltism ignited into full-fledged hatred. Many American intellectuals and business leaders saw nazism and fascism as viable models for the US. The rise of Hitler and the explosion of the Nazi revolution, which frightened many European nations, struck a chord with prominent American elites and antisemites such as Charles Lindbergh and Henry Ford. Hitler’s elite Brownshirts – a mass body of party storm troopers separate from the 100,000-man German army – was a stark symbol to the powerless American masses. Mussolini’s Blackshirts – the military arm of his organization made up of 200,000 soldiers – were a potent image of strength to a nation that felt emasculated.

A divided country and FDR’s emboldened powerful enemies made the plot to overthrow him seem plausible. With restless uncertainty, volatile protests and ominous threats, America’s right wing was inspired to form its own paramilitary organizations. Militias sprung up throughout the land, their self-described “patriots” chanting: “This is despotism! This is tyranny!”

Today’s Proud Boys and Oath Keepers have nothing on their extremist forbears. In 1933, a diehard core of conservative veterans formed the Khaki Shirts in Philadelphia and recruited pro-Mussolini immigrants. The Silver Shirts was an apocalyptic Christian militia patterned on the notoriously racist Texas Rangers that operated in 46 states and stockpiled weapons.

The Gray Shirts of New York organized to remove “Communist college professors” from the nation’s education system, and the Tennessee-based White Shirts wore a Crusader cross and agitated for the takeover of Washington. JP Morgan Jr, one of the nation’s richest men, had secured a $100m loan to Mussolini’s government. He defiantly refused to pay income tax and implored his peers to join him in undermining FDR.

So, when retired US Marine Corps Maj Gen Smedley Darlington Butler claimed he was recruited by a group of Wall Street financiers to lead a fascist coup against FDR and the US government in the summer of 1933, Washington took him seriously. Butler, a Quaker, and first world war hero dubbed the Maverick Marine, was a soldier’s soldier who was idolized by veterans – which represented a huge and powerful voting bloc in America. Famous for his daring exploits in China and Central America, Butler’s reputation was impeccable. He got rousing ovations when he claimed that during his 33 years in the marines: “I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle man for big business, for Wall Street and for bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism.”

Butler later testified before Congress that a bond-broker and American Legion member named Gerald MacGuire approached him with the plan. MacGuire told him the coup was backed by a group called the American Liberty League, a group of business leaders which formed in response to FDR’s victory, and whose mission it was to teach government “the necessity of respect for the rights of persons and property”. Members included JP Morgan, Jr, Irénée du Pont, Robert Sterling Clark of the Singer sewing machine fortune, and the chief executives of General Motors, Birds Eye and General Foods.

The putsch called for him to lead a massive army of veterans – funded by $30m from Wall Street titans and with weapons supplied by Remington Arms – to march on Washington, oust Roosevelt and the entire line of succession, and establish a fascist dictatorship backed by a private army of 500,000 former soldiers.

As MacGuire laid it out to Butler, the coup was instigated after FDR eliminated the gold standard in April 1933, which threatened the country’s wealthiest men who thought if American currency wasn’t backed by gold, rising inflation would diminish their fortunes. He claimed the coup was sponsored by a group who controlled $40bn in assets – about $800bn today – and who had $300m available to support the coup and pay the veterans. The plotters had men, guns and money – the three elements that make for successful wars and revolutions. Butler referred to them as “the royal family of financiers” that had controlled the American Legion since its formation in 1919. He felt the Legion was a militaristic political force, notorious for its antisemitism and reactionary policies against labor unions and civil rights, that manipulated veterans.

The planned coup was thwarted when Butler reported it to J Edgar Hoover at the FBI, who reported it to FDR. How seriously the “Wall Street putsch” endangered the Roosevelt presidency remains unknown, with the national press at the time mocking it as a “gigantic hoax” and historians like Arthur M Schlesinger Jr surmising “the gap between contemplation and execution was considerable” and that democracy was not in real danger. Still, there is much evidence that the nation’s wealthiest men – Republicans and Democrats alike – were so threatened by FDR’s policies that they conspired with antigovernment paramilitarism to stage a coup.

The final report by the congressional committee tasked with investigating the allegations, delivered in February 1935, concluded: “[The committee] received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country”, adding “There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.”

As Congressman John McCormack who headed the congressional investigation put it: “If General Butler had not been the patriot he was, and if they had been able to maintain secrecy, the plot certainly might very well have succeeded … When times are desperate and people are frustrated, anything could happen.”

There is still much that is not known about the coup attempt. Butler demanded to know why the names of the country’s richest men were removed from the final version of the committee’s report. “Like most committees, it has slaughtered the little and allowed the big to escape,” Butler said in a Philadelphia radio interview in 1935. “The big shots weren’t even called to testify. They were all mentioned in the testimony. Why was all mention of these names suppressed from this testimony?”

While details of the conspiracy are still matters of historical debate, journalists and historians, including the BBC’s Mike Thomson and John Buchanan of the US, later concluded that FDR struck a deal with the plotters, allowing them to avoid treason charges – and possible execution – if Wall Street backed off its opposition to the New Deal. “Roosevelt should have pushed it all through and then welshed on his agreement and prosecuted them,” presidential biographer Sidney Blumenthal recently said.

What might all of this portend for Americans today, as President Biden follows in FDR’s New Deal footsteps while democratic socialist Bernie Sanders also rises in popularity and influence? In 1933, rather than inflame a quavering nation, FDR calmly urged Americans to unite to overcome fear, banish apathy and restore their confidence in the country’s future. Now, 90 years later, a year on from Trump’s own coup attempt, Biden’s tone was more alarming, sounding a clarion call for Americans to save democracy itself, to make sure such an attack “never, never happens again”.

If the plotters had been held accountable in the 1930s, the forces behind the 6 January coup attempt might never have flourished into the next century.

SB 167 was filed in recent weeks in response to the fierce debates that have emerged across Indiana. (photo: Michael Conroy/AP)

SB 167 was filed in recent weeks in response to the fierce debates that have emerged across Indiana. (photo: Michael Conroy/AP)

Assistant Attorney General Matthew Olsen, testifying just days after the nation observed the one-year anniversary of the violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, said the number of FBI investigations into suspected domestic violent extremists has more than doubled since the spring of 2020.

“We have seen a growing threat from those who are motivated by racial animus, as well as those who ascribe to extremist anti-government and anti-authority ideologies,” Olsen said.

Olsen’s assessment tracked with a warning last March from FBI Director Christopher Wray, who testified that the threat was “metastasizing.” Jill Sanborn, the executive assistant director in charge of the FBI’s national security branch who testified alongside Olsen, said Tuesday the greatest threat comes from lone extremists who radicalize online and look to carry out violence at so-called “soft targets.”

The department’s National Security Division, which Olsen leads, has a counterterrorism section. But Olsen told the Senate Judiciary Committee that he has decided to create a specialized domestic terrorism unit “to augment our existing approach” and to “ensure that these cases are properly handled and effectively coordinated” across the country.

The formulation of a new unit underscores the extent to which domestic violence extremism, which for years after the Sept. 11 attacks was overshadowed by the threat of international terrorism, has attracted urgent attention inside the federal government.

But the issue remains politically freighted, in part because the absence of a federal domestic terrorism statute has created ambiguities as to precisely what sort of violence meets that definition.

Several Republican senators, for instance, suggested Tuesday that the FBI and the Justice Department had given more attention to the Jan. 6 insurrection than to the 2020 rioting that erupted in American cities and grew out of racial justice protests.

Republican Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas accused the department of “wildly disparate” treatment. Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the Senate’s top Republican, played video clips of the 2020 violence as a counter to the video of the Jan. 6 Capitol rioting played by Democratic Sen. Richard Durbin, the committee’s chairman.

The officials said the department treats domestic extremist violence the same regardless of ideology.

Gov. Tony Evers speaks during a press conference Tuesday, July 6, 2021, in Waukesha, Wisconsin. (photo: Angela Major/WPR)

Gov. Tony Evers speaks during a press conference Tuesday, July 6, 2021, in Waukesha, Wisconsin. (photo: Angela Major/WPR)

The state is a preview of what the GOP will do nationally — if given the chance

Evers hasn't been able to get most of his nominees to the state's higher education system approved by the Republican-controlled state Senate. GOP lawmakers haven't voted on his picks — or, in three cases, haven't insisted the Republican-appointed officials whose terms have already expired duly vacate their seats so Evers can replace them, reports the Wisconsin State Journal. Just like Antonin Scalia's Supreme Court seat, these seats will be held open until they can be filled by the next Republican governor. And Evers' entire tenure has been like this. Wisconsin Republicans have fought him tooth-and-nail on measures to control the pandemic and even started his term by removing key powers his GOP predecessor had enjoyed.

Though famously a swing state, Wisconsin effectively exists under one-party rule — and it's a preview of what the Republican Party aims to do on a national scale.

The foundation of Republican control of Wisconsin is one of the most extreme gerrymanders in American history. Back in 2018, Republicans lost the popular vote in the state Senate races by 52.3 percent to 46.9 percent, yet gained two seats for a 19-14 majority. In the state Assembly, they lost the popular vote 53.0 to 44.8, yet lost only one seat to retain a 63-36 supermajority — and that was a wave election year for Democrats. It is de facto impossible for Democrats to win given any remotely realistic distribution of votes.

That ridiculous Saddam Hussein-esque cheating led to a legal challenge to the gerrymander as a violation of Wisconsin residents' constitutional rights. But the conservative Supreme Court majority tossed the case in 2019 on obvious political grounds, giving Wisconsin Republicans free rein to cheat some more. (Virtually the sole principle in conservative jurisprudence is this: "If it benefits Republicans, that means it's constitutional.")

As a result, new maps based on the latest census data are nearly as bad. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project gives the proposed maps drawn up by the Wisconsin legislature for the Senate and Assembly an "F" for partisan fairness. The project estimates that in a 50-50 election, Republicans would have a 13.6 percent advantage in Assembly seats and a 19.7 percent advantage in the Senate. In both houses, a majority of seats are rated as safely Republican. For the last decade, the people of Wisconsin have had effectively no say in their government, and now they'll have no say for the next decade. Vote for whomever you want, you'll get GOP rule every time.

Now, Evers did win the Wisconsin governorship in 2018 by a whisker because a statewide race is comparatively immune to gerrymandering. But when that happened, Republicans promptly passed a suite of bills gutting his power. That's why he's struggled to fight the pandemic and to get appointees in place. Whenever Democrats win power at any level, the Republican response in Wisconsin (and anywhere they can manage it) is to change the rules.

Democrats aren't immune to the gerrymandering temptation. States like Maryland have a long tradition of rigging district boundaries to benefit Democrats. Historically, they usually did it to protect party machine incumbents in liberal states, not run Republicans out of power forever, though recently, Democrats are starting to respond in kind with congressional maps they control. Still, for all that, Democrats have proposed a law that would ban partisan gerrymandering across the country. That Republicans don't support it shows they think they stand to gain by preserving their ability to cheat.

But the issue in Wisconsin is bigger than gerrymandering, and it should be noted that what Republicans are doing there and in other states has a long tradition in this country. The legal foundation of Jim Crow was various facially-neutral laws that in practice prevented Black people from voting and the opposition from winning any power. The rule established by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and several other racist Supreme Court rulings was that Southern white supremacists could discriminate to their heart's content so long as they pretended they weren't doing exactly that.

However, it would be novel to carry out a similar project on a national scale, and that's what Republicans are trying now. Their gerrymandering in congressional maps at present is not nearly as extreme as it was after 2010, mainly because the current version didn't happen after a sweeping GOP victory, but that won't matter if they just rig the electoral system altogether. Republicans have nearly bulletproof gerrymanders of legislatures in swing states like Wisconsin, Michigan, Georgia, and Arizona. Mobilized by former President Donald Trump's "Big Lie" — that he didn't lose the 2020 election — they're gradually taking direct control of election administration. Deranged right-wing extremists, mobilized by frenzied propaganda about imaginary liberal election fraud, have flooded into previously sleepy election administration positions. The fact that Trump and his top cronies won't be punished for the Jan. 6 putsch has only emboldened them.

The legal theory that state legislatures have total power over their Electoral College votes, and hence can hand them to whatever candidate they want — even after the votes have been counted — is quickly becoming dogma among Republican legal apparatchiks. And if that ploy doesn't work, Republican states could simply refuse to send electors, which would kick the result into the House, where each state gets one vote (according to the traditional procedure, at least), and the GOP would win because they control so many low-population states. SCOTUS, of course, will likely bless any GOP cheating strategy that has even a glimmer of facial legality — they rejected Trump's attempts to overturn the election in 2020, but only because those suits were so undeniably harebrained and loony.

Here we have several strategies by which Republicans can keep control of political power regardless of vote totals — just like they've done in Wisconsin. And if the world's most powerful office comes firmly under their control, it would be a trivial matter to cement control of the rest of the levers of national power as well. Will elected Democrats who are still empowered to do their jobs realize before it's too late?

First responders at the scene of the fire that engulfed a residential building in New York, killing 17 people, on Jan. 9, 2022. (photo: Scott Heins/Getty Images)

First responders at the scene of the fire that engulfed a residential building in New York, killing 17 people, on Jan. 9, 2022. (photo: Scott Heins/Getty Images)

The fire, New York’s deadliest in decades, shows why pandemic-era housing policy Band-Aids aren’t enough.

The blaze was indeed reportedly sparked by a malfunctioning space heater. This alone was not enough to kill 17 tenants, including eight children, and leave dozens more hospitalized in critical condition. According to reports, the fire itself was contained to one apartment. Dense black smoke, meanwhile, spread through the entire 19-story building, through an apartment door that, were it in line with New York City codes since 2018, should have been self-closing.

The 1970s building complex, Twin Parks North West, has no outdoor fire escapes and a history of management neglect, violations, and complaints — including over lack of heat and ventilation. Corporate ownership turnover has only compounded problems. Under normal circumstances, residents said, false fire alarms blared so frequently throughout the day that they had become accustomed to ignoring them.

The Bronx fire was not only a tragedy, but also an injustice, suffered by predominantly poor, working-class, African immigrant families living on Section 8 vouchers, a form of government rental assistance for low-income people. This injustice highlights the need — made ever clearer during the Covid-19 pandemic — to drastically shift power over housing stock away from landlords and investors and into the hands of tenants.

The struggle for housing justice has taken on a new urgency in the pandemic, with a powerful surge in both tenant organizing and mass rent strikes, coupled with a necessary focus on the immediate need for eviction moratoria, their extensions, and the demand for federal rental assistance. As longtime housing advocates have consistently stressed, pandemic-era Band-Aids aren’t enough. Their claims are borne out by the fact that New York Gov. Kathy Hochul and leaders in Albany are allowing the state’s eviction moratorium to end January 15, as Covid cases continue to spike and hundreds of thousands of tenants owe back rent and could lose their homes.

The coming eviction wave and the deadly fire in which New York’s poorest choked to death in their own homes cannot be seen as distinct crises. They are proof of an intolerable system, a state of consistent structural violence by which tenants’ lives are deprioritized in service of landlord and investor bottom lines. They are the evidence that structural shifts in housing policy cannot wait.

It is hardly a coincidence that the West Bronx, where the fire took place, has been described as “ground zero for eviction filings” since March 2020 — eviction proceedings that are stalled only while the moratorium stands.

New York political leaders — both Hochul and Adams — have vowed robust support and permanent housing for those made homeless by the fire. As the New York Times reported, the specific rental assistance vouchers used in the Bronx development are not transferable, rendering it difficult for displaced residents to find permanent housing. “We will not forget you. We will not abandon you,” Hochul said Monday.

Yet survivors of a previous apartment fire in the Bronx in March 2020, which killed four people, remained without stable housing 18 months after the deadly event, City Limits reported in September. Chestnut Holdings, the management company in that case — the owner of one of the city’s largest portfolios of rent-stabilized apartments — has failed to complete necessary renovations, prompting legal action from tenants who fear that the property owners are trying to force them to abandon their rent-regulated homes.

We have scant grounds to put faith in the city and state government’s promises of safe, permanent places to live for those forced from their homes. Just days ago, the new governor and new mayor — a centrist Democrat and a belligerent former cop, respectively — stood side by side and announced a plan to address homelessness by sending more police to respond to unhoused people taking shelter in the New York subway. As such, they continue a long and violent tradition of criminalizing the poor.

On Monday, Adams called the most recent Bronx fire a “tragedy beyond measure” — which it is. He later said that the “one message” people should take from the tragedy was to close doors in the name of fire safety, implicitly placing blame on the family who fled their burning apartment for failing to close the door behind them, enabling the smoke to spread. He did not note that the door should have been self-closing.

Adams also did not mention that a member of his transition team for housing issues, Rick Gropper, is the co-founder of Camber Property Group — one of the group of investors that bought the Bronx building as part of a $166 million, eight-building deal in early 2020. In such profit-driven property relations, affordable housing is treated as an asset and leveraged for access to tax credits. It all but assures that tenants are afterthoughts.

“They’re focused on when to collect their checks and who lives in which apartment. I have to fix everything in my apartment,” a 51-year-old resident of Twin Parks North West, Yamina Rodríguez, whose family survived the fire, told The City. Another resident, Tawanna Davis, who was rescued by firefighters from her apartment on the 15th floor, said of the lack of owner accountability: “Now we have so many different managements we don’t even know what [it’s] called.”

This may not be the 1970s, when landlords in the Bronx quite literally burned down dilapidated, redlined buildings to claim fire insurance payouts, but the neglect and risk faced by poor tenants today is no less systematically produced. The issue is, of course, not specific to New York. Just last week, a fire raged through a dangerously overcrowded public housing unit in Philadelphia, leaving 12 people dead.

Following the Philadelphia fire, the New York Times put it plainly: “Across the country, a crisis in affordable housing has been festering for years, and with the lifting of eviction moratoriums and the dwindling of rental assistance funds offered during the coronavirus pandemic, it is only getting worse.”

Tenant organizers have shown extraordinary strength and solidarity throughout the pandemic. Rent strikes of historic size have not only helped ensure that whole buildings receive rental assistance, but also in numerous cases have helped hold neglectful landlords to account. The ending of eviction moratoria makes this work all the more necessary. Rent strikes, though, remain a high-risk activity so long as landlords hold the power to summarily evict tenants.

For these reasons, housing rights advocates and progressive politicians in New York are pushing hard for the passage of a “good cause” eviction bill into law, which would give tenants the right to lease renewals, cap rent increases on existing tenants, and prevent landlords from removing a renter without an order from a judge, even if their lease has expired or they never had a lease. It would also protect tenants who are demanding repairs or complaining about lack of heat and hot water.

When Hochul announced her $25 billion affordable housing plan last week, which aims to create and preserve 100,000 units of affordable housing and 10,000 supportive housing apartments, she said nothing of eviction laws. “Good cause” eviction is not a fix-all solution to violent property relations, but at the very least the law would mitigate the risk of fighting a landlord over living standards. In a scenario of true housing justice — a reality distant from our own — very little, and certainly not lack of payment, would count as “good cause” to evict someone from their home.

Residents in public housing and those dependent on Section 8 vouchers for rent have the least leverage over the condition of their homes. There’s no impetus for property owners to improve living conditions; the federal rent checks and tax credits will flow either way.

Events like the Bronx fire should motivate a significant and structural government response. All too often, they do not. Over four years since a fire in London’s Grenfell Tower public housing high-rise killed 72 people, there has been vanishingly little systemic change.

Political leaders on this side of the Atlantic will do no better if they are not pushed — pushed by activists like those already on the ground in the Bronx, some of whom are immigrant organizers from Gambia, the birthplace of a significant number of Twin Parks North West’s tenants.

Adams can put his energies into policing poverty and telling apartment residents to close our doors in case of fire. To his door and the doors of his allies in the real estate industry, meanwhile, we must bring the fight to decommodify housing and take tenants’ lives out of profiteers’ hands.

Members of Teamsters Local 63 join union workers to rally in downtown Los Angeles, in support of unionizing Alabama Amazon workers, March 22, 2021. (photo: Al Seib/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images)

Members of Teamsters Local 63 join union workers to rally in downtown Los Angeles, in support of unionizing Alabama Amazon workers, March 22, 2021. (photo: Al Seib/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images)

American workers have power. That won’t last forever.

American employees in 2022 have more leverage over their employers than they have had since the 1970s, the result of a confluence of factors. The pandemic that began in 2020 has prompted a widespread reevaluation about what place work should have in the lives of many Americans, who are known for putting in more hours than people in most other industrialized nations. There’s also been a groundswell of labor organizing that began building momentum in the last decade, due to larger trends like an aging population and growing income inequality. This movement has accelerated in the past two years as the pandemic has brought labor issues to the fore.

“I feel like there’s a change in the culture of Americans” to become more pro-labor, said Catherine Creighton, director of the Co-Lab at Cornell University’s Industrial and Labor Relations school.

“The pandemic created a huge shift where people can take the time to say, ‘What’s going on in my life?’ And it just stopped the clock for a moment, for people to say what’s important and not important,” she said.

Huge numbers of US workers have been quitting their jobs or leaving the workforce entirely, as a booming economy has created more demand for workers. This so-called Great Resignation, or Great Reshuffle, has continued even as expanded state and national unemployment benefits have run out. The ensuing labor shortages have shifted the balance of power from employers to employees — at least for those with in-demand skills or in in-demand industries.

These conditions create a fertile ground for Americans to seek higher wages, better benefits, and improved working conditions. But that leverage will only last as long as the worker shortage. Whether these improvements continue into the future for all workers will require a mix of policy change and union growth. Considering that lawmakers are currently at a standstill in the Senate over everything from the infrastructure bill to voting rights, union organizing seems like the most promising way to push these kinds of changes forward.

“I’ve been working for the union for 40 years and there’s never been a better time to organize than right now,” D. Taylor, international president of the hotel and food service worker union Unite Here, told Recode, citing a pro-labor administration, labor shortages, and growing economic inequality.

He said that while workers are using the current situation to eke out better pay and benefits, those gains are temporary and could be wiped out in coming years by inflation and layoffs.

“The only fundamental way to change the economic livelihood and the rights of workers is through the union movement,” he said.

Why now is the time

Of the many effects Covid-19 has had on America, how it’s changed the way we think about work might be among the most indelible.

The pandemic made work harder for many people and highlighted the longstanding struggles of workers across many industries. The ongoing public health emergency and its ensuing repercussions for health care workers finally shined a light on the industry’s long-ignored concerns: lengthy hours, incommensurate pay for health care workers like nurses, and the dangerous but crucial nature of their work. People who serve food and sell groceries for wages that are often too low to live on sustainably suddenly became inadvertent front-line workers, heralded for their bravery in the first waves of the pandemic (but largely forgotten in the subsequent ones). And workers who toil in e-commerce warehouses or offer delivery services became integral cogs to the US economy in an extreme way, as their existing complaints about inhumane treatment in the workplace went uncorrected.

Even white-collar workers, whose labor is often higher paid and objectively safer than many blue-collar employees, are experiencing high rates of burnout and mental health issues, prompting them to question work’s meaning in their lives and whether it was ever necessary that they commute daily from their homes to work on computers somewhere else.

And now, a record number of Americans have been quitting their jobs — 4.5 million in November alone, representing 3 percent of all employment.

The rates of job openings and quits are near or at their highest levels

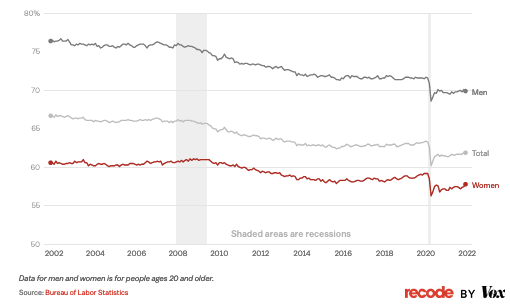

There are also millions more open jobs than there are Americans willing to fill them. That’s partly because there are 3.6 million fewer people on payrolls than there had been pre-pandemic. Labor force participation rates — the share of the population that’s working or looking for work — are far below pre-pandemic levels.

The share of the population that's working or looking for work hasn't recovered

The reasons for the decline are myriad. Older Americans — who were already on track to depart the workforce as they age — are retiring early, with people over the age of 55 accounting for about half of the decline in the labor force participation rate since February 2020. Many women have left jobs to stay home to watch children, and as the omicron variant continues to close schools and quarantine students, it’s keeping many of these women from returning.

Some people are making ends meet by doing gig work or by starting their own businesses, which doesn’t always show up on BLS employment situation data geared to payrolls, and can lack safeguards offered by traditional jobs, such as health care. Others are living off investments in the stock market and alternative assets. People have rented out rooms in their homes or loaned their cars. They’re surviving off savings they built by staying home during the pandemic and by collecting government benefits. Many are getting by on a spouse’s income, by moving in with family, or simply by making do with less.

At the same time, the economy is booming, meaning companies would need more workers even if they weren’t quitting in unprecedented numbers. This has given workers a lot more sway in the market.

“Because of the extraordinary circumstances, we are seeing a transfer of power,” Heidi Shierholz, the president of the Economic Policy Institute, said. “We’re in a really abnormal situation.”

Businesses are having no choice but to adapt.

“When I talk to leaders of companies, they’re literally panicking because they can’t fulfill their services. They can’t deploy their product. They can’t meet their growth goals because they don’t have trained talent,” Tsedal Neeley, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, told Recode. She said companies that preemptively make work better for their employees — higher pay, remote flexibility, other financial and social incentives — will have a business advantage over those that wait for their workers to demand those benefits.

“We have not completely grasped the tsunami of changes that have fallen upon us and that will continue to fall upon us,” Neeley said. “Work has changed. Workers have changed.”

Companies that can’t find enough workers have had to cut back hours and circumscribe their offerings because of worker shortages. Anecdotally, job listings on the hiring platform Indeed are increasingly urgent, using language like “immediate start” or “start today.” Employers are waiving requirements they used to have for job candidates, like degrees, experience, and even background checks. Workers who play their cards right have the opportunity to get the jobs they actually want.

As this is all happening, Americans are increasingly interested in — and approving of — unions, which will be able to fight for lasting change on behalf of workers.

Kenneth Hagans, a catering employee at the Caesars Superdome stadium in New Orleans, is trying to form a union with his coworkers in order to improve pay (he makes $12.50 per hour) and to attain benefits (he doesn’t have any). Even though he said his employers are short-staffed, they have not raised pay, relying instead on temp workers.

Hagans, who is 60 years old, has health problems and works two jobs when he’d like to just work one. He believes now is the time to form a union due to the poor financial circumstances many Americans find themselves in.

“Look at what’s going on in America — it’s not just happening to me, it’s happening in this whole country — people are being paid low wages, and everything is going up,” he said. “You went to the grocery store — you see how high groceries are. You buy a car — you see it’s $5,000 or $10,000 more to buy a new car today. So the wages need to come up.”

Unite Here’s Taylor believes that such factors could lead to an increase in union membership in coming years. Membership rates have been declining for decades, but ticked up slightly in 2020 — not because union membership increased but because union members were more likely to hold on to their jobs in the recession than non-union members. 2021 numbers come out later this month.

Recently, a company-owned Starbucks in the US voted to unionize, and more locations around the country have followed suit. Other ongoing high-profile unionization efforts and actions by workers at companies as far afield as online retailer Amazon, tech review site Wirecutter, and food manufacturing company Kellogg’s could lead to even more momentum in union formation.

“It lets people know, ‘Hey, wait, I can do something about this?” Cornell’s Creighton said. “Even though it’s a handful of people, it can create a spark.”

That said, more robust union formation faces severe obstacles.

“The way the law is written and has been interpreted over the last 86 years has made it so that it’s almost impossible, in the private sector in America, to form a union,” Creighton said. “Even with all of these labor shortages, which are helping give current workers more leverage, it’s still very difficult.”

National legislation that would make it easier to unionize is languishing in the Senate. Unite Here’s Taylor thinks strong union efforts will still prevail.

“If the labor movement, if unions aggressively organize [and] are prepared to have very difficult battles with corporate America — I do [think union membership will go up],” he said. “I think it really rests in our hands, even though all the factors are there to be successful.”

What the American worker stands to gain

So far, the labor shortfall in the past two years alone has already brought significant gains to many workers.

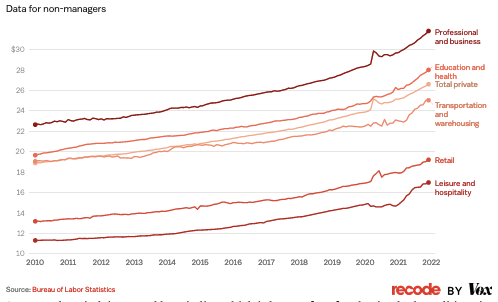

From February 2020 to December 2021, hourly pay for non-manager positions rose 11 percent on average for all employees (about double the typical growth for the equivalent time period). Wages grew most swiftly in the lowest-paying fields, like leisure and hospitality, which has seen pay go up 14 percent over pre-pandemic levels, though it remains objectively relatively low. (Inflation has pretty much wiped out these gains.)

Average hourly earnings have recently grown rapidly

Some workers in leisure and hospitality, which is known for often having bad conditions in addition to low pay, are getting more regular schedules and a clearer path to advancement because employers are eager to fill empty positions.

The specter of unionization has also forced changes.

Michelle Eisen, a barista at the first unionized company-owned Starbucks, in Buffalo, New York, said that when her store filed a petition to organize a union back in August, the company began answering some of their demands by solving supply chain issues, hiring more people, and offering seniority pay.

Eisen, who spoke to me while taking a break from picketing outside her store on Friday, January 7, says there’s still a lot of work to be done. Foremost is worker health and safety: She and other workers at her store walked out earlier that week because they had been exposed to Covid-19 by a colleague and weren’t allowed to quarantine with pay if they didn’t show symptoms. Starbucks corporate has disputed this claim, saying they did offer isolation pay.

Eisen and her colleagues have been contacted by hundreds of other Starbucks employees at locations around the country, leading her to believe her store’s unionization will lead to others.

Of her own decision to form a union, she said that poor working conditions had brought her to her limit last year. “I had two options: It was to either leave a company that I’d spent 10 years with — with people that I liked, in a store that I liked, with a customer base that I really enjoyed and cared about — or we can try to make some changes from the inside,” Eisen told Recode.

These kinds of positive changes for workers aren’t limited to the service industry. Hiring bonuses and incentives have become increasingly popular. Some more progressive employers are seriously entertaining ideas about offering time off for mental health issues, shifting to four-day workweeks, and whether we should be working at all during the apocalypse. A college in Buffalo, New York, just moved to a 32-hour workweek.

Still, there is a long way to go and a lot more improvements to be made.

As long as the shortfall of employees continues — which experts told us could last at least a year, but likely longer — workers have a chance to make their jobs better, either by quitting and finding more suitable work or by joining a union.

It’s possible that US policy will change the future of work as well. Some politicians are floating ideas of offering universal basic income, which would set a basic standard of living for all Americans, regardless of their work status. There could be a future in which all Americans have access to parental leave and paid time off — not just those lucky enough to have jobs that provide those benefits.

Neeley, however, has little faith that policy will change. But right now, that might not matter. She said work is getting better because employers have no choice.

“Organizations have to respond or react to market forces or these exogenous shocks that started with Covid,” Neeley said. “If you want to hire, if you want to retain, if you want to meet your basic objectives in your organization, whether it’s a small business or these large enterprises, you need people.”

For some white-collar workers, that’s meant they’ve been able to attain long-sought-after perks like remote work, which enables them to save time commuting and have a better work-life balance.

At the height of the pandemic, more than half the workforce exclusively worked from home, according to survey data from Gallup. Now, approximately a quarter of employed people are doing so, while another 20 percent are working from home some of the time, in what’s called a hybrid model. We’ve learned from the pandemic that many more could work remotely — and the current situation is primed for workers to demand it.

But the unique advantages of this time won’t necessarily last. Depending on what workers, organizers, and politicians do with this moment, we could end up with a culture of work that’s better, or not.

“Now is the time where people are realizing, due to labor shortages and what they’ve been through in the last few years, that they could have momentum to change their working lives,” Creighton said. “It’s very important we do something now. Because if not now, when?”

In a February 2, 2002 photo, detainees from Afghanistan sit in their cells at Camp X-Ray at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. (photo: Lynne Sladky/AP)

In a February 2, 2002 photo, detainees from Afghanistan sit in their cells at Camp X-Ray at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. (photo: Lynne Sladky/AP)

Clive Stafford Smith reflects on how his clients remain in the detention centre without charges or a trial, 20 years on.

My clients have been locked up without charges or a trial for almost two decades now, somehow proof to the American people that the government is combating “Islamic extremism” – when in truth we are provoking it.

I took a walk early on a Sunday morning – before the tropical sun got too high in the sky – 4 miles (6.4km) along Sherman Avenue in search of Camp X-Ray, the notorious tangle of wire that was home to the first “war on terror” detainees almost 20 years ago.

I wanted to see what remained.

The FBI had “investigated” Camp X-Ray in 2009, supposedly searching for evidence of the abuse of prisoners. Perhaps they should have intervened when the well-documented torture was going on.

I thought the Camp had been torn down, but I was mistaken. The scar on our collective conscience remains.

The site immediately carried me back to my father’s favourite poem, Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Dad used to recite it to me when I was perhaps six, before I went to sleep, resounding with the futile vanity of a king who thought the world was awed by his power. The statue he built to himself inexorably collapsed, leaving only the feet with their boastful pedestal: “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! / Nothing beside remains. Round the decay / Of that colossal Wreck …”

There is a fair amount left of Camp X-Ray, as it is only 20 years on. The wire fence, topped with a DNA helix of razor wire, still runs around an area perhaps 200 square metres (2,153 square feet) in size, sitting in a hollow that must have trapped the tropical heat.

There are no longer any hooded prisoners in their iconic orange uniforms, cowed by soldiers and their attack dogs. But I could make out seven or eight open cages, each with a tin roof like a lean-to parking space. At the corners were the wooden guard towers, redolent of a German Prisoner of War camp in World War II, with plywood walls turned to a dirty brown. I noticed a tree that has grown inside the wire – perhaps now 10 metres (33 feet) tall, a tribute to the passage of time since the original folly.

All around, though, the signs remained: “Photography and Videography Forbidden”. To be sure, it would be a shameful reminder of the birth of the disastrous Guantanamo experiment, but why should this be kept secret? Why not learn from history?

‘A sorry lie’

Indeed, the history of Guantanamo teaches us that some things never change. On April 30, 1494, Christopher Columbus sailed into the Bay, in search of a better world. He stayed less than 24 hours, recognising that El Dorado was not to be found in this tropical wasteland. The US was never likely to learn why Osama bin Laden launched 9/11 on the World Trade Center here either.

The Guantanamo detention camp was born a sorry lie and it remains one. The US military first announced the prison to the world in carefully censored choreography on January 11, 2002. Along with two colleagues, I sued to open it up to proper public inspection just about a month later. It took more than two years to reach the US Supreme Court, but we won Rasul v Bush before conservative justices who were shocked that the Bush administration would claim the right to hold prisoners entirely beyond the rule of law. I was allowed here to meet a client for the first time in November 2004.

Back then, US Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld assured us that the 780 detainees were the “worst of the worst” in the world. I knew the government would have made some mistakes, they always do, but I was operating primarily on principle – there is nobody who may be denied the right to notice of the charges against him and a fair trial.

Nevertheless, I thought I would encounter many men who had been captured on the battlefield of Afghanistan, and that we would have some explaining to do.

Instead, to my surprise, there were very few “terrorists” here.

I found Mohammed el-Gharani, a 14-year-old who had been snatched from Karachi where he was studying English: the closest he had ever been to Kabul was a little more than 1,400 kilometres (872 miles) by the fastest road. I came across Ahmed Errachidi, a Moroccan chef from London who had a long and documented history of bipolar disorder and, during one of his psychotic episodes, had announced that a large snowball was about to destroy the Earth.

I met Sami al-Haj, an Al Jazeera cameraman, who had been confused with another journalist, accused of the heinous offence of interviewing Osama bin Laden. He should therefore presumably have found himself in a cell with Robert Fisk of the Independent, Peter Arnett of CNN, and John Miller of ABC News – all journalists who also felt they should interview the man.

‘Sold like slaves in an auction’

It took a while to figure out what was going on, but in the end, it turned out to be a familiar story: just as American prosecutors buy their informants with lavish promises of rewards, so we were littering bounty leaflets around Afghanistan and Pakistan. As President Pervez Musharraf bragged in his autobiography, In the Line of Fire, “We have … handed over 369 [detainees] to the United States. We have earned bounties totalling millions of dollars.” My clients had been sold, like slaves in an auction.

After almost 20 years, one might think that the mighty CIA would have sorted out the intelligence wheat from the Musharraf chaff.

Sadly, this is not the case: 39 detainees remain today, and 15 of them have been cleared for release, reflecting unanimous agreement by the six top US intelligence agencies that they pose no threat to the US or its coalition. Those 15 add up to about 300 years of false imprisonment based on the initial lie.

Take Ahmed Rabbani, he was also sold to the US for a reward, on September 10, 2002, again in Karachi. He came ready-tagged as a much-wanted “terrorist” called Hassan Ghul. He insisted he was merely a taxi driver. The CIA did not know what to believe – but better safe than sorry. They took him 1,000 kilometres to the Dark Prison in Kabul for 540 days and nights of torture.

I met Ahmed more than 10 years ago, when he told me his story about how he was hanged by his wrists in a deep pit, a medieval torture called Strappado where the shoulders gradually dislocate. It was much used by the inquisition. Ironically, we would later learn from the US Senate torture report that the US captured the real Hassan Ghul and brought him to the Dark Prison to join Ahmed in January 2004. Ghul was held there for two days, and he “cooperated”, and was later sent back to Pakistan and freed – whereupon he went back to his “extremist ways”, and was killed in a drone attack in 2012.

Better safe than sorry? Only Ahmed and his pregnant wife would be sorry.

Ahmed was not freed, he was sent to Guantanamo Bay, where he remains 19 years later. Seven months after his original detention, his wife gave birth to their son Jawad, who has now celebrated his 18th birthday without ever having touched his father.

Ahmed was recently cleared, along with four other clients of mine, but I still represent one who is not, who is no more a “terrorist” than my grandmother.

In so many ways, Guantanamo has not changed since I first arrived here.

To be sure, it is less efficient – I used to be allowed to spend 55 hours a week with my clients, a boon since I do not come here for a tropical holiday; now they have cut it to a maximum of 23 hours, which makes a banker seem relatively hard-working. It used to be more cost-effective – but as the number of detainees shrank, the annual cost per prisoner has soared to $13m. This is almost 200 times as expensive as the second most costly prison in the world, in Colorado in the US, that costs $78,000.

But Guantanamo is and always has been a huge blot on the reputation of the US. The Afghan war was not lost recently in Kabul; it was doomed from the moment the world saw pictures of torture and abuse. If that is what democracy means, many mused, the Taliban cannot be so bad.

“It’s an international public relations disaster,” said an anonymous US senior Defense Intelligence Agency official in early 2004 to journalist David Rose. “For every detainee, I’d guess you create another 10 terrorists or supporters of ‘terrorism’.”

After almost 20 years, the intelligence agent would surely revise his view. The notorious prison has prompted thousands of disaffected youths to hate the US and wish us ill. It is perhaps the most foolish own goal in US history.

Cargo ship. (photo: USDA)

Cargo ship. (photo: USDA)

Global shipping is moving invasive species around the world. Can world governments agree on necessary preventative measures?

The crew of beetles aboard the Pan Jasmine is not an isolated incident. That same month bee experts north of Seattle were scouring forest edges for Asian giant hornet nests. These new arrivals, famously known as “murder hornets,” first turned up in the Pacific Northwest in 2019, also likely via cargo ship. The two-inch hornets threaten crops, bee farms and wild plants by preying on native bees. Officials discovered and destroyed three nests.

And this past autumn Pennsylvania officials urged residents to be on the lookout for spotted lanternflies, handsome, broad-winged natives of Asia discovered in 2014 and now present in at least nine eastern states. Believed to have arrived with a shipment of stone from China, the lanternfly voraciously consumes plants and foliage, threatening everything from oak trees to vineyards.

These are only a few of the more charismatic invasive species that have arrived in the U.S. by cargo ship. But less visible invaders are also coming in and may include pathogens, crabs, seeds, larvae and more — some with the potential to upend ecosystems and agricultural crops.

“Commercial shipping is one the biggest ways invasive species are transported globally,” says Danielle Verna, an environmental monitoring expert who has researched the issue for more than a decade. Her work has taken her to busy ports in Maryland, Alaska and San Francisco Bay, which is considered one of the world’s most biologically invaded estuaries.

Verna, who primarily studies invasive species in marine waters, explains that commercial shipping enables organisms to effortlessly cross geographic boundaries at speeds that cannot occur naturally, which increases their survival rate. And as the volume of shipping increases, so do opportunities for invaders.

“The more shipping we do, and the more connections we make, the more potential we create for the spread of species,” says Verna.

Canadian researchers made the same point in 2019, when they predicted a global surge in invasive species by mid-century, caused by projected increases in overseas commerce. Added to that, climate change and the global shipping glut tied to the pandemic can also benefit new introductions.

By Land and by Sea — The Pathways for Pests

A cargo ship is a mighty thing. It can stretch a fifth of a mile and carry more than 10,000 containers, each holding thousands of items that have already moved by train or truck across great distances.

At any point during these journeys, native species can latch onto items or their packaging and wind up on the deck of a ship headed for another continent.

The ship itself can also be a host, especially for marine species. It’s a daunting array of vectors, but as Verna has learned, some paths are better traveled than others.

“You have to look at the trade partner and the traffic patterns,” she says, pointing out as an example that some Asian habitats resemble ones along the U.S. West Coast. Identifying such similarities can help predict where invasive hotspots may develop.

For marine species, Verna says the type of ship also matters. Research shows tankers and bulk carriers or “bulkers” — those carrying unpackaged commodities such as grains or coal — appear especially prone to species transport. Their hull shape, slower speed and duration in ports allow species to gather on a ship’s underside, in a process called biofouling. It inadvertently moves alga, crustations, invertebrates and others to new habitats, where they can affect both native species and infrastructure such as storm drains or even coastal power plants.

Tankers and bulkers also tend to carry more ballast water, which can be sucked aboard on one side of the ocean and discharged on the other. Along with biofouling, it’s a key way marine species reach new habitats. A particularly costly example is the European green crab, currently competing with native Dungeness crabs along the U.S. and Canadian west coasts.

Research by Verna and others on the effect of tankers and bulkers shows that the type of ship arriving in a port can be a better predictor of biological invasions than the simple volume of ships. It also means seemingly unrelated shifts in trade activity can invite a rise in foreign species. For instance, the arrival of more tankers and bulkers as coal and natural gas exports increased in Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf Coast drove up ballast discharge in local estuaries.

But while tankers and bulkers may matter most for marine invaders, container ships pose unique opportunities for the plants and insects that, like the lanternfly, can quickly spread across a landscape. In this case, the commodities and their packaging pose the greatest concern. Plants and anything made of wood are especially hazardous.

For example, in 2017 Wisconsin officials warned that log furniture imported from China and sold locally was infested with wood-boring beetles. Officials had been alerted by consumers who found sawdust as they unpacked their new furniture. The beetles and their larvae can survive for two years inside the furniture before emerging as adults, officials warned.

Rima Lucardi, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service in Georgia who has studied invasive species for 20 years, also points to the importance of wood packaging materials, which accompany most ocean-bound goods arriving in the United States. These include crates, pallets, skids and cases — the types of materials that got the Pan Jasmine kicked out of U.S. waters. Lucardi says species like the beetles found aboard that ship commonly stow away in packaging materials and can, if given the chance, disrupt ecosystems and economies in places like the Southeast’s lumber-producing forests.

Research increasingly shows both the outside and inside of containers provide the nooks and seams where parasites, snails, insects and other organisms can lurk or lay eggs. Such surfaces have likely spread the brown marmorated stink bug around the world, which now damages U.S. crops and was even recently blamed for delaying car shipments to Australia.

Lucardi’s work recently led her inside the shipping containers that deliver so many of the goods that surround us. Acting on a request by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which along with the U.S. Department of Agriculture inspects inbound cargo, Lucardi examined the intake grilles of refrigerated containers arriving at the sprawling Garden City Terminal in Savannah, Georgia, the largest container port in the country.

“Refrigerated shipping containers are much like any refrigerator,” says Lucardi, explaining that they need constant air exchange, which means they can suck up insects and plant propagules from anywhere along their routes.

Lucardi’s research found thousands of seeds from roughly 30 species, including wild sugarcane, a federally prohibited noxious weed that has invaded parts of Florida. While conducting the work, Lucardi also experienced the fast-paced port environment that whisks goods — and invasive species — from ports to almost infinite inland locations.

“A container can get put on a truck or train within 24 hours of arriving,” says Lucardi.

That busy port environment is another important piece of the invasive species puzzle. As just one example of a range of possible impacts, at ports across the globe artificial lighting attracts swarms of native insects on a nightly basis, any number of whom may get sucked into a container’s intake grille, fly inside a container or lay eggs on a container’s surfaces.

Lucardi says these and other vectors bring non-native species to U.S. ports every day, although less than 1% become established. But that small fraction has already transformed the landscape — and even human cultures — in regions across the country.

An Old Threat, Compounded by Climate and the Pandemic

Ships have moved species about the world for ages. Researchers believe that in the 1840s a strain of the pathogen Phytophthora infestans, which causes potato blight, followed trade routes from Mexico to Belgium, where it began damaging crops. It quickly reached Ireland, where the Irish Lumper was the spud of choice. With the Lumper offering a veritable monocrop, P. infestans decimated crops and gardens, leading to famine, death and mass emigration to the United States, where people like my own great-grandmother built new lives in cities like Boston.

But that’s hardly all. In the late 19th century, a fungus that likely arrived with Asian nursery stock began killing American chestnuts. Once known as the “perfect tree” for its quality lumber, superior tannins and abundant nuts, the chestnut was wiped out in just decades. From Maine to Georgia and west to Illinois, 4 billion trees died, forever altering the landscape. In an example of cascading co-extinctions, three species of chestnut-dependent moths also disappeared.

More recently the Asian emerald ash borer, which likely harbored away in wood packaging materials, has destroyed tens of millions of U.S. trees since just 2002. Similarly, millions of hemlock trees in the eastern United States are succumbing to the woolly hemlock adelgid, which likely arrived on Japanese ornamental plants. As the hemlock slowly disappears, the region loses its most common native conifer, a unique habitat niche, and a source of long-term carbon sequestration.

The emerald ash borer and wooly adelgid are also getting a leg up from climate change, which has warmed winters and allowed the insects to expand their North American range. Verna and Lucardi say such climate-induced expansions are expected to continue, and not just in forests. Evidence suggests warming waters are carrying European green crabs north toward Alaska.

Both scientists also acknowledge that shipping delays associated with the pandemic may further aid invasives, whether through ships spending longer times stuck in ports or containers remaining stationary for longer periods in shipyards.

Prevention, Prevention, Prevention

Over decades the United States and other countries have spun an intricate web of regulations meant to reduce the spread of species by cargo ship. The story of the Pan Jasmine shows that in at least some cases the system can work. But governing a global fleet of thousands of ships, moving among hundreds of ports, is slow and tortuous work.

Few know that better than Marcie Merksamer, an environmental biologist and ballast water expert who has studied the issue for two decades and helped shape implementation of an international ballast water-management treaty. The agreement, governed by the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization, was written in 2004 but is only now taking effect.

Merksamer says the gap between writing the rules and implementing them includes a 13-year effort to convince enough countries to sign the treaty for it to be ratified. In that time, governments, industry, intergovernmental agencies and others wrangled over an ocean of details, from the technological to the political.

“It’s very complicated,” says Merksamer. “Regulations that work for an island nation like Fiji don’t necessarily work for a larger country like Norway.”

In the end the new rules require ships to adhere to a discharge standard that, in the interim, requires them to exchange ballast water in deep seas far from coastlines. That will later change to a requirement to equip all ships with high-tech water-treatment systems proven effective at treating organisms in ballast water.

More than 80 countries have signed on — representing 90% of global shipping tonnage — and the treaty is in what the IMO terms an “experience-building phase.” Merksamer describes this as a time for industry and regulators to try the rules, test the new treatment systems, and gather feedback and data. The phase was scheduled to end in 2022, but the IMO is considering delaying that until 2024, when the treaty would become more stringent.

But that’s not all, explains Merksamer. During this same long interval, the United States, which is not party to the IMO treaty, plotted its own course toward ballast-water regulation after years of lawsuits and proposed legislative solutions by industry and conservation groups. In 2018 Congress finally responded with the Vessel Incidental Discharge Act, which amended the Clean Water Act to clarify regulatory roles. Rulemaking for that law is ongoing, but it’s expected to eventually create standards for commercial operations.

Similar tales surround other vectors. For instance, in 2011 the IMO finalized international voluntary guidelines to reduce biofouling on commercial vessels. The guidelines lack the force of the ballast-water treaty but are intended to create global consistency. Then in 2014, New Zealand introduced the world’s first mandatory national standards for biofouling. They align with the IMO guidelines but require ships entering the country to meet a “clean” standard or face on-site cleaning.

Regarding the topsides of ships, international rules for wood packaging materials were established by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization in 2002 and have since been amended several times. They mandate a standardized stamp showing materials have been treated with either heat or the highly toxic methyl bromide fumigant. In the United States, Custom and Border Protection agents — like the ones who booted the Pan Jasmine out of New Orleans — inspect for the stamps. And while the story of the Pan Jasmine and other 2021 seizures are encouraging, critics point out that agents only inspect a fraction of the cargo arriving each year.

Regulation of shipping containers is far less developed. The FAO promotes voluntary cleanliness guidelines, but in 2015 it paused movement toward an international standard. Concurrent North American efforts have also only focused on voluntary practices, while a coalition of industry groups recently voiced opposition to development of any international rules. However, Australia and New Zealand now tout a partnership with industry that requires inbound containers to be cleaned inside and out and sprayed with insecticides.

With research by Lucardi and others shining a light on containers as vectors, many observers are hoping for a more anchored global policy. And while the regulatory sphere is convoluted and evolving, a unanimous thread is its focus on prevention.

Prevention is the number-one way to manage invasive species, says Verna. “It presents upfront costs, but they’ll be lower than most follow-up management actions.”

The sentiment resonates as officials across the country scramble after errant hornets, beetles, flies and crabs, and as residents grieve the loss of native denizens like chestnuts and hemlocks.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment