Final Day of January: Funding Badly Needed

We don’t have enough funding. There’s really no other way to say it. Every fundraising step we take is an attempt to address that one central problem.

Please take a moment to make a donation.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Will Congress take the bold step of barring its members from trading stocks?

Congress thought it had already fixed what looked alarmingly like insider trading by its members. In 2012, lawmakers overwhelmingly voted to enact a bill known as the STOCK Act, banning themselves from using information they learned on the job for personal financial benefit. The law required sitting members—along with their staff and public officials in other branches of the government—to make more specific and timely disclosures about their financial transactions. Although the law helped the public spot conflicts of interest, it was unable to prevent them. “Members hear all kinds of news that essentially may amount to insider trading, but it’s almost impossible to enforce insider trading and to prove what happened when,” Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon, a Democrat who has been pushing for years to restrict stock trading by members of Congress, told me.

The Justice Department investigated several senators for their 2020 stock dumps but filed no charges. The allegations of pandemic profiteering did, however, have major political repercussions and helped Democrats win their narrow Senate majority last year. Among those who found their transactions under federal scrutiny were both Republican senators from Georgia, David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler (they both denied any wrongdoing), who lost in special elections last January. The Democrat who defeated Perdue, Senator Jon Ossoff, is now leading a new push to ban members from trading individual stocks altogether.

“There’s widespread bipartisan disgust with America’s political class, and stock trading by members of Congress is egregious and offensive,” Ossoff told me last week.

Legislation that he’s introduced along with Senator Mark Kelly of Arizona would require members of Congress, their spouses, and dependent children to either sell their individual stocks or place them in a blind trust. (A bipartisan companion bill was previously unveiled in the House.)

The proposal is, not surprisingly, popular with a public that loves to look down on its lawmakers: Nearly two-thirds of all respondents, including majorities of both Democrats and Republicans, backed the idea of banning members of Congress from trading stocks, according to a recent poll conducted by Morning Consult. Yet the bill is likely to be least popular among the people who actually have to vote on it. If Congress has struggled in recent years to tackle the nation’s most complex challenges, its track record of policing itself is arguably even worse. Republicans made little effort to pass ethics legislation when they last ran Washington, and although House Democrats did advance a major anti-corruption bill as part of its initial voting-rights push last year, they quickly jettisoned its major ethics provisions in a (thus far unsuccessful) bid to win passage in the Senate.

The proposed ban on stock trading by lawmakers has upended the expected ideological divide. A co-sponsor of the House measure is conservative Representative Chip Roy of Texas, a former top aide to Senator Ted Cruz. The bill has also won the backing of two groups that usually defend unfettered access to the free market, the Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity and FreedomWorks, which emerged from the Obama-era Tea Party. Carrying the libertarian flag instead is House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, whose husband, Paul Pelosi, has made millions in stock trades that have become fodder for amateur trackers on social-media platforms such as Reddit and TikTok. “We’re a free-market economy. [Members] should be able to participate in that,” Pelosi told reporters earlier this month, sounding more like Ayn Rand than a San Francisco “socialist.”

The last significant ethics legislation to clear Congress was the STOCK Act a decade ago. Even that bill, however, passed only after party leaders watered down a tougher initial proposal, and within a year of its enactment, Congress quietly acted to roll back one of its key transparency provisions.

The need to regulate stock trading by lawmakers is obvious to the bill’s supporters, who on this particular issue know well of what they speak. Members of Congress are privy to market-moving information before the general public on a near-daily basis. That is especially true in times of crisis, such as a major military buildup or the onset of a global pandemic, when the stock market is more volatile and lawmakers frequently receive classified briefings from senior government officials. They might not be able to discuss what they heard in public, but until the passage of the STOCK Act, it wasn’t clearly illegal for them to make money off it. House and Senate votes are themselves occasionally market-moving events, and lawmakers are usually the first to know whether a measure will pass or fail. One of the authors of the STOCK Act, former Democratic Representative Brian Baird of Washington State, told me that in moments of dark humor during major floor votes, a colleague would joke to him (and he emphasized that he was indeed joking): “We could make some money off this vote, right?”

In 2012, the authors of the STOCK Act believed an outright ban on stock trades was “a bridge too far,” Baird told me. But the pandemic-trading scandals propelled calls for new legislation, and more recent disclosures, including a lengthy investigation by Business Insider, have given the push added momentum. So, too, has Pelosi’s brush-off, which prompted the bill’s backers to redouble their efforts. “I fervently disagree with her,” Representative Abigail Spanberger of Virginia told me. Spanberger, a Democrat, first introduced legislation with Roy more than a year and a half ago. “There’s many professions where there are limitations placed on what someone can do financially. This requirement is an absolutely reasonable one for those of us who choose to enter this profession.”

The proposals would allow members and their families to keep control of investments in diversified mutual or index funds, U.S. Treasuries, and bonds. Kelly told me that in addition to preventing insider trading by lawmakers, requiring members to step back from active control of individual stocks would ensure that they aren’t taking votes on legislation based on how it would impact them financially.

Adding to the pressure on Pelosi, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has suggested that Republicans might implement a ban if they win back the majority this fall. Pelosi last week softened her stance, telling reporters that although she remained personally opposed to the proposal, “if members want to do that, I’m okay with that.”

The developments over the past month have created a dynamic reminiscent of other successful drives for new congressional ethics laws, Craig Holman, a lobbyist for Public Citizen and a longtime government-reform advocate, told me. “The prospects are very good,” he said. “Sometimes we have to embarrass Congress into doing the right thing, and it works once the public gets involved.”

Yet the supporters of a ban on lawmaker stock trading still have a ways to go. Public support for a bill can mask broader private opposition, and the leaders of this most recent effort are mostly members with relatively little experience in Congress. The STOCK Act ultimately passed with near-unanimous votes, but Baird told me that during the years when he was first pitching the bill to colleagues, many took offense at the mere suggestion of impropriety. Others wanted their investments to remain private, and some just didn’t want the added inconvenience of having to disclose them. “I thought naively that this would be such an obvious right thing to do that when I raised it with people, they’d respond, ‘Gosh, I didn’t know that. We should fix it,’” Baird chuckled ruefully. “Well, the response was anything but.” After the STOCK Act’s passage, Baird said he found himself in an elevator with an aide to a high-ranking Democrat who didn’t realize he was speaking with an author of the bill. “I gotta go home and fill out my effing paperwork for the goddamn STOCK Act,” the staffer complained.

Kelly told me he didn’t have much sympathy for members who opposed ethics legislation because of the hassle of complying with it. “If you don’t want the hassle, find something else to do,” he said. “There are plenty of folks who could do this job.” His retort epitomized the challenges that Kelly and his allies face. They are asking their colleagues to vote for a bill that won’t require sacrifice by their constituents, only by themselves. “Frankly, I don’t mind whose feelings I hurt when I make that case,” Ossoff said. “My colleagues need to hear it, and I think they are hearing it.”

Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, right, who sits on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, speaks to students following a mock trial on Dec. 14, 2017. (photo: Michael Robinson Chavez/WP)

Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, right, who sits on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, speaks to students following a mock trial on Dec. 14, 2017. (photo: Michael Robinson Chavez/WP)

But this one was a personal appeal. It had been sent by her distant uncle, Thomas Brown Jr., inmate #15854-004, who was serving a life sentence in Florida for a nonviolent drug crime. He was sending documents he hoped his niece could use to get him out of federal prison.

Jackson, 51, is now a judge on the influential U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and a leading contender for President Biden to nominate to replace Justice Stephen G. Breyer, who last week announced his plan to retire from the Supreme Court. She would be the first Black woman on the court if she were nominated and confirmed, and the first justice in decades with deep experience as a criminal defense attorney.

Jackson’s brush with her uncle and his prison sentence, which arose out of the nation’s war on drugs, adds to a set of life experiences that would distinguish her from previous justices. The uncle, Thomas Brown Jr., was sentenced to life under a “three strikes” law. After a referral from Jackson, a powerhouse law firm took his case pro bono, and President Barack Obama years later commuted his sentence.

Civil rights groups and other liberal advocacy organizations have promoted Jackson for Biden’s shortlist of Supreme Court contenders not only because of her gender and race — Biden has pledged to nominate a Black woman — but because of her varied personal and professional experience, particularly as a federal public defender. Nominees to the federal bench more often have worked as prosecutors and corporate lawyers.

As a public defender, Jackson represented people accused of an array of crimes who could not afford an attorney. Later, as an Obama appointee on the U.S. Sentencing Commission, she helped rewrite guidelines to reduce recommended penalties for drug-related offenses. And as a trial judge for eight years, she sentenced more than 100 people to prison.

Jackson grew up in a high-achieving household in Miami. She was a high school debate champion and went on to attend Harvard University and then Harvard Law School.

She has not spoken publicly about her uncle’s case. Though news accounts have referenced her having an uncle whose life sentence was commuted, his identity, the details of his crimes and his direct appeal to Jackson — along with her response — have not been previously reported.

Jackson’s chambers declined to comment for this article.

The following account is based on state and federal court records, clemency information and interviews with people familiar with Jackson’s experiences at different points in her life. Some agreed to speak only on the condition of anonymity to discuss private matters.

“For Ketanji, the law isn’t just an abstract set of concepts. Her family’s experience does inform her awareness of the real impact the law has on people’s lives,” said a friend and former colleague from the federal defender’s office.

By the time her uncle contacted her, that person said, she was an experienced attorney and “already knew what has become a national consensus that the nation’s drug laws were overly harsh.”

Jackson saw Brown, her father’s older brother, infrequently while growing up in the Miami area in the 1970s and 1980s, according to a person familiar with their interactions. The daughter of two teachers, Jackson spent more time with her mother’s side of the family. Her mother’s brother, Calvin Ross, rose through the ranks to become chief of the Miami police department. Her father studied law when Jackson was a young child and went on to become the local school board’s attorney.

In 1976, when Jackson was five, her uncle’s troubles began to surface in court records. Brown, then 37, was arrested and charged with carrying a concealed firearm as well as possession of heroin and possession of drug paraphernalia.

While that case was pending, Brown was standing outside a Miami laundromat as police approached. A man nearby handed something to Brown, who threw it to the ground, his defense attorney said, according to a transcript of court proceedings. Brown was arrested for alleged possession of heroin.

The latter charge was not pursued by prosecutors, but Brown pleaded guilty to the earlier gun and drug possession charges — both felonies — and was sentenced in state court to 18 months of probation.

Six years later, in 1982, Brown was back in court in the Miami area. This time, the charge was possession of at least 20 grams of cannabis, a felony at the time. Brown pleaded guilty in state court and was ordered to pay a fine of $1,500.

In 1989, when Jackson was a freshman at Harvard, Brown was 50 and mixed up in South Florida’s notorious cocaine trade. On April 18, Brown pulled his El Camino up to a Miami home, unaware that five federal agents were staking out the house. Brown left a few minutes later with a black nylon gym bag, placing it on the passenger seat. The agents followed. They soon stopped Brown and found the gym bag filled with what federal authorities later said was 14 kilograms of cocaine, wrapped in duct tape, court records show.

Brown was indicted on charges of possession of cocaine with intent to sell and conspiracy to commit that offense. Several months later, a jury in federal court found him guilty of the first of those crimes. A federal law that had recently taken effect ratcheted up punishments for repeat drug offenders, mandating life in prison in certain cases after a third drug offense.

U.S. District Judge Lenore C. Nesbitt rejected the argument from Brown’s attorney that his client should be sentenced under the old rules, which would have added 20 years for his two past drug offenses, according to a court transcript. The judge said she had no choice but to impose a life sentence because of those prior convictions. Brown’s punishment was upheld on appeal.

Jackson had not seen or heard from her uncle in more than a decade when Brown first called her at the federal defender’s office in 2005, the person familiar with their interactions said. By then, Jackson had worked as a clerk for three judges, including Breyer at the Supreme Court. She had been in private practice in Boston and D.C. and spent two years as an assistant special counsel on the sentencing commission.

“Can you help me? I’m in jail,” Brown told Jackson in their first phone call, according to the person with knowledge of their interactions. “Your dad tells me you’re a public defender.”

Jackson’s former colleague and friend recalled talking with her about the stamp-laden envelope she received later from her uncle. Jackson felt sympathy for his situation, the former colleague said.

Jackson’s office, however, represented only people convicted in federal court in D.C. Her uncle had exhausted his appeals in court, and she had no immediate options to recommend, the person familiar with their interactions said. In 2008, she referred him to a powerhouse private law firm, Wilmer Hale, after learning that attorneys there handled clemency cases free of charge.

In a statement to The Washington Post, Wilmer Hale said Jackson referred the case “years before she became a federal judge. She had no further involvement in the matter.”

Brown’s push for clemency eventually overlapped with a national bipartisan effort to undo harsh mandatory sentences that had been imposed on nonviolent drug offenders.

The Obama administration’s Justice Department played a key role in that effort by aggressively reviewing clemency petitions. In eight years, Obama commuted the sentences of more people than the past 12 presidents combined, with a focus on nonviolent drug offenders. More than 1,700 people had their sentences commuted.

Larry Kupers, the deputy pardon attorney at the Justice Department when Brown’s sentence was commuted, said it was not unusual during Obama’s presidency for high-profile law firms to represent inmates seeking clemency.

At Obama’s urging, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act in 2010, lowering some mandatory minimums for drug offenses. The law did not apply retroactively, but the Justice Department began encouraging federal inmates to petition to have their sentences commuted to fall more in line with what they would have been under the revised law.

By 2014, the clemency initiative expanded to include efforts to address “the worst of” three-strike convictions, Kupers said.

Kupers said someone with Brown’s criminal background would have fallen squarely into the category of those the Justice Department saw as eligible for relief.

That same year, Wilmer Hale filed its petition on behalf of Brown, the firm said.

As the Justice Department was focusing on clemency for those already in prison, the U.S. Sentencing Commission — with Jackson as a member — was taking steps to adjust sentencing guidelines. That effort, too, had bipartisan support.

In 2014, as a vice chair of the commission, Jackson backed a proposal to make sentencing guidelines for most federal drug trafficking offenders less severe. Months later, the commission voted to apply the reductions retroactively, a move that expedited the release of tens of thousands from federal prisons.

“It was probably the biggest decision the commission had ever made,” said Rachel E. Barkow, who served with Jackson on the commission at the time.

The commission’s actions were informed by five years of data that showed shorter sentences for crack-cocaine convictions resulted in lower recidivism, she said. The changes did not affect sentence “enhancements” under three-strikes laws, such as those Brown had received.

On. Nov. 22, 2016, two months before he left office, Obama commuted Brown’s life sentence along with those of 78 other drug offenders. Jackson learned about her uncle’s planned release when she looked up the public list of names, according to the person familiar with her interactions with Brown.

Jackson did not submit a letter or communicate with the Obama administration on her uncle’s behalf, the person said.

W. Neil Eggleston, Obama’s White House counsel at the time, told The Post he had no recollection of Jackson contacting the White House.

Brown was 78 years old and in fragile health when he was released the next year. Jackson’s parents saw him on one occasion in Florida, the person familiar with her interactions with Brown said.

Brown told them that he was moving to Georgia with a friend, the person said, and Jackson’s parents had not heard from him since. He died in 2018, less than a year after his release, according to public records.

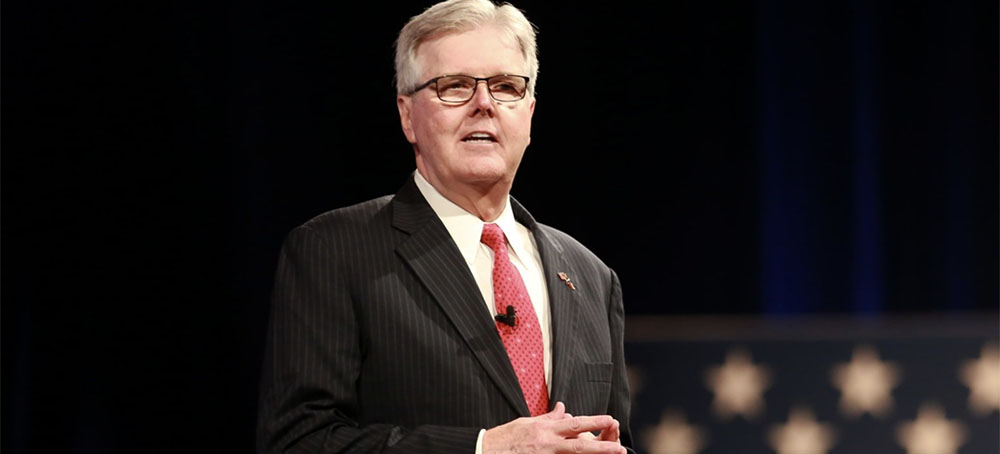

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick. (photo: Dylan Hollingsworth/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick. (photo: Dylan Hollingsworth/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Dan Patrick owns a Houston station where hosts rant about cyborg supersoldiers, Jan. 6 conspiracy theories, and coronavirus craziness.

“They’re already among us, cyborgs,” declared Spagnoletti. He returned to the theme repeatedly in his hour-long program. “Cyborg supersoldiers—we see them around, we’ve seen some of them.”

The title of this particular episode was “Beyond the Great Reset,” alluding to the long-debunked conspiracy theory that pandemic restrictions are a prelude to a new regime of biomedical totalitarianism. Yet in his hour-long broadcast, Spagnoletti pushed the twisted vision to its weirdest and most dystopian conclusions: that the goal of the shadowy global elites is not just a unified one-world government, but a fully fused human hive mind in which “electrodes snaking into your gray matter will be thieves slipping in the backdoor.”

Along the way, the local maritime lawyer also baselessly claimed the novel coronavirus is “military technology.”

Spagnoletti is no isolated crank: his former co-host, who first brought him onto the radio two years ago, was the second-place finisher in Houston’s nonpartisan mayoral election in 2019. And the microphone Spagnoletti spewed his delusions into and the station that carried them across the greater Houston area belong to one of the most powerful men in the nation’s second-largest state: Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick.

In a statement to The Daily Beast, Patrick spokesman Allen Blakemore asserted that the lieutenant governor neither tunes into the station any more, nor has any involvement in its programming.

“It would be fair to guess that he hasn’t listened to more than eight hours of programming in the past eight years,” said Blakemore. “Operations are overseen by a program manager and a sales manager.”

Blakemore refused to say whether the lieutenant governor believed Spagnoletti’s conspiracy mongering, or in any of the false claims aired on KSEV. The station itself did not respond to requests for comment. Patrick’s most recent disclosures to the Texas Ethics Commission show he remains the station’s owner and president. And even if he has not appeared on it live recently, Patrick is a constant presence on the station: in a recurring clip promoting a syndicated program, as a pitchman for a local tree pruning service, and on the minds of its employees, as hosts have joked on-air about reporting off-color comments to “our boss, the lieutenant governor.”

What is undeniable is that KSEV has helped shape the politics of the Lone Star State. And so, too, has Patrick.

Thanks to the unique structure of the Texan electorate, experts said, KSEV’s core demographic—hardcore conservatives in Harris County, who skew older and white—may be the most important voting bloc in the Lone Star State. And in the past decade and a half, they have launched Patrick into and through the Texas Senate and landed him in the most powerful role in state government.

“It’s hard to exaggerate how much influence they have in statewide politics,” political science Professor Richard Murray of the University of Houston told The Daily Beast. “And Dan Patrick is proof of that.”

In the seven years he has served alongside Patrick in office, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has built up national name recognition, personal political cachet, and a powerful fundraising operation. But experts asserted that it is Patrick, thanks to his position’s control over the agenda in the State Senate, who truly steers policy.

“I think that when you look at raw power, constitutionally granted, the lieutenant governor holds the most, because he is uniquely positioned to stop legislation and punish senators by taking away their committee assignments,” said Professor Joshua Blank, research director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin. “Patrick really does seem like the kind of ideological warrior who is looking to move the state in a more conservative direction, and he’s much more in a position to do that as lieutenant governor than as governor.”

A former sportscaster born Dannie Goeb, Patrick purchased his first block of time on KSEV in 1987, shortly after bankrupting his chain of local bars. One year later, he bought the station itself with financing from a notorious savings and loan fraudster.

Patrick denied any knowledge of his patron’s machinations to the Dallas Morning News in 2014. But the propensity for questionable business practices has apparently persisted. In November 2021, Patrick Broadcasting LP—the company through which the Republican owns the station—inked a consent decree with the Federal Communications Commission for failing to properly maintain legally required records on the paid political advertising it aired.

Blakemore, speaking on Patrick’s behalf, blamed this on KSEV’s small staff and characterized it as a “minor violation of the timeliness of their political file,” further noting that the FCC imposed no fine. The FCC told The Daily Beast that the station had missed deadlines to disclose its political advertisers for no fewer than four years. The agency said that it had established a new policy in mid-2020 to waive penalties on all stations in violation of the requirements in favor of consent decrees establishing compliance plans.

What has also been consistent over the years has been Patrick’s penchant for outrageousness. He became famous in the early 1990s for stunts like getting a vasectomy on-air—and infamous in early 2020 for his suggestion that senior citizens would willingly sacrifice their lives and health so that the economy could reopen during the worst of the pandemic. He provoked controversy again last year for appearing to blame Black Texans for the state’s spiking COVID-19 caseload.

But even Patrick’s most brazen antics fall well short of the flagrantly false and conspiratorial claims his hosts regularly vent on KSEV.

A day spent listening to the station, which broadcasts out of a faceless office complex on Houston’s western fringe, makes for a jarring journey over uneven terrain. Sunny promos for local contractors vie with apocalyptic political ads, and bland, meandering real-estate programs segue into bilious and paranoid—though no less rambling—conservative call-in shows.

A number of those shows are nationally syndicated programs hosted by the likes of Ben Shapiro and Brian Kilmeade. But Patrick’s old 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. drive-time slot has fallen to a particularly fact-averse Houston original: Chris Blayney, who goes by Chris X.

A three-year veteran of KSEV, Blayney hardly lets one of the four days a week he’s on the air pass without him spreading some falsehood or spurious speculation about politics or public health. Every hour of his show opens with a quote of the fictional far-right dictator Adam Sutler, from the 2006 film V for Vendetta (a clip, oddly enough, in which the character calls for a campaign of fear-mongering propaganda to further entrench his regime).

A particularly egregious example came on the first anniversary of the bloody Capitol riot, in which Blayney alternated between downplaying and suggesting without evidence that the plot was the work of agents provocateurs.

“The people really attacking, were they really Trump supporters?” Blayney questioned at the top of his broadcast. “It was a few hundred people that got out of control, that I think, honestly, I’ve seen enough videos now, they were instigated.”

Over the course of the show, Blayney parroted popular but unfounded Republican claims that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi oversaw congressional security on the day of the electoral vote count and that she turned down National Guard troops. He also raised other debunked talking points about alleged rioter and Oath Keeper Ray Epps and about John Sullivan, who before being charged with attacking the building was known as an unwanted hanger-on to left-wing groups in Utah.

All of this, Blayney maintained, was part of an even more diabolical conspiracy.

“The reality of today one year ago is that these Democrats are liars, and they’re charlatans, and they’re part of this charade to simply obscure the fact that they politicized a pandemic to steal an election,” he said, even though numerous Trump-linked lawsuits failed to produce a scintilla of proof of substantial misconduct in the 2020 presidential vote, and so-called “whistleblowers” largely reversed or contradicted themselves in court.

In the next hour, he compared vaccine mandates to the Holocaust, a beloved trope of the anti-vaxxer crowd. “We now know what Americans would have helped the Nazis round up Jews,” he asserted.

Blayney reiterates disproven claims about the election constantly, most recently on Jan. 24, when he berated the beleaguered Biden administration and declared “they stole the election, and now it’s a total disaster.”

Later that episode, he argued COVID-19 was a bioweapon, a notion virtually the entirety of the scientific and intelligence communities has long rejected. (There is a somewhat less fringe debate that remains ongoing about whether it might have leaked out of a lab.)

Blayney’s falsehoods about the election and the pandemic frequently come in tandem. For instance, on his Jan. 19 show, he followed up an extended rant in which he proclaimed, “I don’t believe for a second [President Joe Biden] got 81 million votes” with praise for a local doctor who has treated COVID-19 patients with ivermectin. This anti-parasitic drug has become a favorite folk remedy among conservatives, despite the lack of evidence of its efficacy against the novel coronavirus.

That Houston physician is far from the only fringe medical figure Blayney has promoted on his show.

He was an early and ardent supporter of Dr. Stella Emmanuel, the Houston doctor who became famous in 2020 for touting the unproven COVID “cure” hydroxychloroquine—as well as for claiming some medical treatments contain alien DNA, that uterine fibroids and ovarian cysts result from exposure to demon sperm, and that “reptilians” control at least part of the U.S. government. And on at least five occasions, Blayney has hosted Tracy “Beanz” Diaz, one of the first and most infamous advocates of the QAnon conspiracy theory, which holds that a cabal of Satan-worshiping pedophiles control Hollywood and the Democratic Party.

Blayney and Diaz’s conversations stuck largely to unfounded allegations about COVID-19 and election fraud, but he called Diaz “one of my favorite people on social media” and urged his audience to tune into her podcast Dark to Light—the title of which is a key QAnon catchphrase.

In a statement to The Daily Beast, Blayney denied any knowledge of Diaz’s ties to QAnon, which he called “a crazy conspiracy group.” He noted that he has acknowledged on the radio that there were Trump supporters who committed crimes at the Capitol last year, and called for their prosecution. He also asserted he is not an anti-vaxxer, even as he continued to question the effectiveness of COVID shots.

“I do not knowingly make claims on my program that are untrue,” he insisted. “Opinions often change with additional information, so mine will sometimes vary from show to show with added and updated information.”

Blakemore, Patrick’s representative, repeatedly refused to say whether the lieutenant governor believed in any of Blayney’s broadcasted claims about the pandemic, the election, or the Capitol riot. He did, however, say that Patrick is personally vaccinated against COVID-19 and did not seek ivermectin when he recently came down with the virus.

Blayney’s conspiracy-mongering never quite attains the delirious heights of Spagnoletti’s. And, unlike the cyborg-phobic host, Blayney’s show does not start with a disclaimer that “this program has been paid for all or in part by the host and KSEV is not responsible for its content.” Nonetheless, Spagnoletti delivers his tirades in what appears to be a KSEV studio, into a KSEV microphone and in front of a KSEV sign, and the ads and the call-in number are the same as for every other show on the station. “Frankly Talking” airs exclusively on KSEV, incorporates the KSEV logo into its own, and KSEV houses its episodes on its Soundcloud with the rest of its original content.

The recent episode in which Spagnoletti raved about human-robot hybrids was just one of seven he dedicated to the Great Reset, though he has gestured toward theory in far more episodes, dating all the way back to when he shared the program with Buzbee in 2020. Biden’s Build Back Better proposals, the bungled withdrawal from Afghanistan, COVID-19 vaccines and boosters, mask mandates, discussions of racism in public schools, multi-family housing development, liberal prosecutors and judges releasing rather than locking up the accused: all, according to Spagnoletti, are part of the expansive plot to dissolve all nations and human relations and reconstitute the world into a single socialist order.

“The whole thing is meant to control society, and to break it down, from the individualistic nature that is the American way of life,” he asserted on his Jan. 14 program.

Spagnoletti also frequently claims COVID-19 was manufactured to advance this insidious agenda, and has further falsely asserted that the COVID-19 shot does not provide protection against severe illness, and that those vaccinated against the virus are more infectious than the uninoculated.

He, too, has flirted on-air with Jan. 6 conspiracy theories.

“Many of them looked like FBI agents to me,” he said on his Jan. 7 broadcast this year, echoing an increasingly popular and completely unsupported article of far-right faith. “It’s the U.S. government which can become the enemy when it oversteps its bounds in order to try to manipulate people to an end.”

Blakemore noted that Spagnoletti pays for his airtime—just as Patrick did when his voice first graced the station’s frequency. The lieutenant governor’s spokesman, and Spagnoletti, also told The Daily Beast that the show has been canceled, though neither would say who made this decision or when.

Spagnoletti, for his part, denied being a conspiracy theorist or opposing COVID-19 vaccination, even as he continued to rail about the Great Reset in an email to The Daily Beast and referred to an unspecified “detriment” to getting the jab. And Blakemore refused to say whether Patrick endorsed or denounced any of the outlandish claims the host made on his station.

This is part of a pattern for Patrick and other leaders in his party, according to the University of Texas’s Professor Blank.

“You see this with Patrick and you see this with others: it’s not that there’s an active effort to spread conspiracy theories, but there is no appetite to discredit or discount them. I think that’s the position that Dan Patrick has taken,” the academic said. “If you were to hear content on Dan Patrick’s radio that pushed the truth that the election was run well and there’s very little evidence of widespread fraud, and stressing the importance of vaccines and vaccine boosters, that would land Dan Patrick in much more hot water in Texas.”

It’s difficult to determine how many people Patrick’s station exposes to such extreme and inflammatory programming. Recent ratings data for the station is hard to find, and KSEV did not supply any. The Texas Tribune reported in 2017 it was just the third-biggest talk radio channel in the Houston-Galveston market, and its listenership has almost certainly shrunk since, given industry trends and the pandemic’s impact on commuters.

Its heavily Republican listener base is by far the minority in the state’s biggest city: in 2019, then-KSEV host Tony Buzbee—a flamboyant local lawyer who shared and later ceded the mic to Spagnoletti—lost the run-off vote for Houston mayor to Democratic incumbent Sylvester Turner by a whopping 12 points.

But such results can be deceptive, asserted University of Houston Professor Murray.

The metro area’s sheer size means it is home to one of the biggest troves of Republican votes in the state. And, for nearly three decades, the victors of the GOP primaries have captured every office representing the entirety of Texas. KSEV listeners’ intense engagement and participation in politics only amplifies the signal they send to Austin and Washington, D.C., argued Murray.

“This has given him an enormous amount of power in the political process,” Murray said, referring to Patrick. “The content traffics in the outer reaches of political misinformation, that has a lot of influence with white conservatives and conservative voters, who are so influential in Texas politics.”

But Blank argued the fault for KSEV’s content lies not in its stars, but in its listeners themselves.

“It’s getting increasingly hard to separate what is actually a conspiracy theory and what is a belief held by a substantial enough portion of the population that political actors feel they can advantage themselves by shifting to address it,” said Blank. “I think it’s lamentable, don’t get me wrong. But can you imagine how many radio stations in Texas not owned by the lieutenant governor that are spouting nonsense and conspiracy theories every day? And it doesn’t really seem that there’s any penalty for anybody.”

Scott B., an undercover fed who breached far-right death squads and squashed their national web of terror cells. (Scott requested that his surname not be used for the sake of his family's safety.) (photo: Mike Belleme/Rolling Stone)

Scott B., an undercover fed who breached far-right death squads and squashed their national web of terror cells. (Scott requested that his surname not be used for the sake of his family's safety.) (photo: Mike Belleme/Rolling Stone)

Scott was a top undercover agent for the FBI, putting himself in harm's way dozens of times. Now, he’s telling his story for the first time to sound the alarm about the threat of far-right extremists in America

But first, we need to talk about the ram. Because that ram — actually, a terrified goat with diarrhea — died for all our sins of the past four centuries.

It is Halloween evening 2019, and Scott — undercover coordinator for the FBI and special agent dispatched to its Joint Terrorism Task Force — is shivering in three layers, including tactical gear, in the pitch-black woods of northern Georgia. He has infiltrated a domestic-terror group called the Base, posing as a former skinhead who calls himself PaleHorse and is expert in hand-to-hand combat. Scott and 11 Base members are walking an unmarked path to a clearing above a creek bed. He doesn’t know most of the men he’s with; they’ve come from far distances to this encampment on a farm for a four-day training block on guerrilla warfare. Five of them traveled from Northeast states with assault rifles and armor in their car trunks. Another, a young psycho who calls himself ZoomGnat, has been up for two days straight on Adderall and Red Bull and has driven from Texas without stopping. None of them call one another by their given names, only their noms de guerre: Pestilence, PunishSnake, BigSiege, etc. Several are ex-military with munitions training and the wherewithal to take out power stations. Others are self-taught tactical freaks who shoot and move as nimbly as paratroopers. The internet will teach you anything these days, including how to start a race war in three steps.

The day had broken mild but turned bone-cold later, and was now, after many hours of slanting rain, a misery of mud and wind. When they came to the clearing, the members lit torches and formed a circle around the fire. Incantations were spoken by one of the men, citing the Wild Hunt and other gross misreadings of pre-Christian and Norse mythology. And then — because this was a sacrament not to the gods but to the massacre of Jews, Blacks, and gays — it was time to sacrifice the trembling animal they’d kidnapped from a neighbor’s farm.

The goat, all 80-something pounds of him soaking wet, was shitting and bleating in prostrate fear of these men in death masks and camo. The man leading the ritual — code name: Eisen — swung the machete overhead. He hesitated a moment, then brought the blade down; it bounced off the animal with a whomp. Goats aren’t built for ritual kills, as it happens: The scruffs of their necks are double-reinforced with back straps of gristle and fur. After further attempts at holy butchery, someone had the bright idea to just shoot the thing already. But this, too, quickly became a clusterfuck. Eisen looked away as he pointed the pistol — and the members, after all, were in a circle. One of them could have died if he misfired.

And so Scott, who in real life is a sniper-grade marksman and who teaches his fellow agents how to shoot, stepped in to school the young neo-Nazi on the rudiments of gun safety. But the goat didn’t die after a single head shot; its legs kept flailing, as if to taunt Eisen for being such a weasel. Finally, Eisen put a second slug in him. Now, the dark sacrament could begin.

Someone slit the animal’s throat and filled a chalice with the blood that came glomping out. The men passed the chalice around the fire, each taking sips from the cup. By the time it got to Scott, though, the blood had somehow chunked into dim-sum lumps of plasma and — oh, hell no, he’s not drinking that mess. He dipped a pinky into the chalice and touched it to his lips as one of the men began to vomit. Not a genteel purge but the full-boat Linda Blair, the contents of his dinner spraying the trees. Sweet Jesus, Scott thought as he looked around the campfire at these misfits in training for mayhem. He was the only Christian at this devil’s mass, and the only functional adult on hand. While some of the others took hits of acid and spooked themselves by talking to the severed goat’s head, Scott stood as close to the fire as he could. “It was so fucking cold, and I couldn’t warm up in my truck: I was taping the whole thing on audio recorder.”

Scott is telling this story in the study of his farmhouse high up a hill in the Appalachians. It hunches like a fort on its timbered perch, with assault rifles and armor in the linen closet and kill-shot sight lines of the unmarked road running past his drive. As he talks, he screens footage that he took of those men through a hidden cam on his person. It was wildly risky work, taping terrorists with long guns in woods miles from his support team. It is no less risky to be showing this film and revealing these details for mass consumption. Scott has never been named in public, even at criminal trials. So thorough was the evidence he gathered covertly that every defendant he ever arrested pleaded out.

But he’s breaking his covenant now for the reason he took that footage: He is haunted by what the people onscreen will do if their movement — and their moment — aren’t thwarted. Over months of interviews with Scott and his former colleagues, hours-long conversations with domestic-terror experts, and wormhole dives down fascist portals on apps like Gab and Discord, a portrait emerged of a nation under threat from a thousand points of hate. “We’ve seen massive increases in plots and acts” committed by domestic terrorists, says Bruce Hoffman, a Georgetown professor and counterterror authority whose Inside Terrorism is the master text on the subject. “Me and my team lay awake nights kicking the walls, because there’s a million-and-a-half guys online plotting murder,” says Rita Katz, the founder and director of the SITE Intelligence Group, and the author of the forthcoming Saints and Soldiers, which tracks the rise of far-right terror in the age of Trump. “We’re in a business where we can’t be wrong once,” says Scott. “And there’s way more of them than us undercovers.”

I ask him how he endured those spectral hours in the company of such fools. Scott stiffens and pulls up pictures on his phone.

“This,” he flashes the photo of a teen with a bowl haircut and a sunk-chest, scarecrow build, “is Dylann Roof. He killed nine people in a church.”

“And this,” he flashes the photo of a crew-cut dork in glasses, “is Patrick Crusius. He’s charged with killing 23 at a Walmart in Texas. So don’t think for a second you can read these boys by how they look on Twitter.”

Then Scott fetches up a meme he pulled off one of the apps where rageful kids meet up. It is a viral poster of the so-called saints who inspire white terrorists worldwide. At the top is Saint Breivik — as in Anders Breivik, the Norwegian who slaughtered 69 people at a summer camp for kids, and another eight in Oslo with a van bomb. Just below him is Saint Tarrant — as in Brenton Tarrant, the Australian who murdered 51 people in a pair of New Zealand mosques. Two down from him is Robert Bowers, the Pennsylvania trucker who allegedly slew 11 at a synagogue in Pittsburgh. This meme is a totem pole for Nazi youth in training, the standings in a pennant race of killers. Bracketing their stat lines is a phrase in block chalk: “Will you make it onto the leaderboard … in the fight for white survival?”

Scott doesn’t look like any guardian you’ve met, unless by “guardian” you mean the cooler at a Vegas strip joint who keeps the drunks off the girls with a black-eyed glare. He’s been lifting all his life and has the setup to prove it: mail-box quads and meat-plow arms that dispose him to sleeveless tees. At six feet four and 260 pounds, he fills up a room without meaning to, though he never wastes time trying to merge with his surroundings. He’s funny and profane and could charm a lampshade off its base with his whiskey-sour drawl and Harley swagger. Small wonder that even strangers at the Quik Mart call him Tex, though he’s as much from Amarillo as you or me.

But being a giant with full tat sleeves is its own disguise: No one sees you and thinks “plainclothes cop” hiding cameras in your leathers. That’s the trademark of a crack undercover: a genius for playing yourself. “What I do isn’t acting, ’cause acting’ll get you killed,” says Scott. “I’m just out here being darker shades of me.” He tartly describes his targets — homicidal bikers who beat their victims with hammers; racist gangsters who pimp out their women under the sobriquet “Aryan angels” — as “my ass-out country cousins,” rednecks raised in the same locus he was but who went right when he went left. “If I hadn’t’ve played [foot]ball in college and been friends with lots of Black guys, I might’ve shared a few of their views,” he says. Scott drains the last of his third Jack Daniel’s — he drinks the stuff like seltzer — then laughs at the thought of espousing hate. “Yeah, nah, probably not. I ain’t big on stupid.”

Still, playing Klansmen and hired killers, he had the chops to infiltrate homegrown terror. For 28 years in law enforcement — first as an investigator a year out of college at a county sheriff’s office in the Carolinas, then as a shooting star at the FBI — he’s been working his way into, and out of, tight spaces, breaching outfits that chop up cop impostors. Sitting in the crates he brought home when he retired are the field notes and transcripts of every case he’s worked. They corroborate the accounts he’s giving here and chart the plagues of the past three decades — the flood tide of drugs from the five cartels penetrating our southern border; the poisoning of the suburbs by Big Pharma and the opioid mills they helped spawn; and the radioactive gush of white supremacy through the fire hose of social media. Scott seems almost wistful now to recall the Nineties, when the bogeyman in America was crack cocaine.

By his count, there are 600 FBI agents who are certified as UCEs (undercover employees). But some of them do the work of “backstopping” agents: creating false credentials and social media profiles for UCEs working in the field. Of the several hundred people who do face-to-face ops, most have only handled a couple of cases as the primary undercover. “There’s maybe 50 in the country who’ve done five or more ops — and then the rare few who’ve done double digits,” says Shawn McAlpin, a prolific UCE who retired to run a cannabis dispensary. Scott has done dozens, though they tend to run together; he has, after all, a type. “No one’s gonna send me in on corporate crimes; my country ass would be laughed out of the boardroom,” he says.

And so he made his name doing the dirty jobs, often juggling several ops at once. He infiltrated the Outlaws — a national biker gang that rivals the Hells Angels in size — and sent 16 members or their associates to prison for guns, drugs, extortion, and violent crimes. Hours before they swung a huge dope deal one night, they summoned Scott to their clubhouse in Taunton, Massachusetts. Scott was kitted out with his standard trousseau: a tiny camera and a recording chip secreted on his person (it would breach tradecraft to say precisely where). They ordered him — at gunpoint — to get naked.

Scott was stunned; he’d been undercover for 18 months and committed six crimes with them already. (Or so they thought.) “Not gonna lie to you: My asshole was knittin’ a sweater, going chicka-chicka-chicka as I stripped,” he says. They searched Scott and his garments, but missed the microcamera — a providence he chalks up to his god. Later, at one of the strip joints they called home, his adrenaline dump turned to rage. “Fuck you, motherfuckers,” Scott hissed, turning purple. “Tomorrow, before the drop, I’m making all you bitches strip!”

Next up was Operation Poetic Justice: a sheriff’s office in the hillbilly South dealing drugs, untaxed cigarettes, and taking bribes. “There was so much corruption, it seeped into government, because everyone was related up there,” says Mike MacLean, Scott’s FBI supervisor in Knoxville. Before Scott and his team took down 50 people, including cops and their family members, he was sitting with a deputy’s relative one night when the guy pulled a shotgun, hammers cocked. “I find out you the law, you a dead man,” said the relative, baring his toothless gums in a snarl. Months later, after the takedown, Scott sat with the man again, introducing himself as FBI. “Aw, hell, I knew you was law the whole time,” said the relative. “Yeah?” said Scott, who hears that often, post-arrest. “Then why’d you sell me coke for a year?” “Oh, that’s ’cause I like you,” said the man.

Compound that criminal dementia with fanaticism and you get the pretzel logic of white power. In the hate groups that he breached, Scott encountered credos that only cracked-out satirists could conceive. One night, he sat up drinking bourbon with a Klansman who laid out the dual-seed theory. In the Garden of Eden, it was Adam, Eve, and Abel, and Abel, born of Adam, sired the white race. Then came the snake with forbidden fruit — only, the “fruit” was Eve sleeping with the snake. The snake, being Satan, fathered Cain and the mud people, starting off with the Jews. Then, you got your Blacks, gays, commies, and Asians: They’re all the seed of Satan, too. Christians can kill them and it ain’t a sin to do so, since they’re hell spawn who don’t have souls.

The names of the demons changed as Scott roved the racist circuit: lizard people, beasts of the field, short-faced bears. The rules changed, too, even under the same flag. Aryan Nation disciples in the state of Tennessee trafficked dope and guns and pimped their girls on Backpage, often to Black and brown johns. This raised the hackles of the Right Rev. Richard Butler, who’d founded Aryan Nations in the Seventies. From his compound in Idaho, he sent cease-and-desist letters to those crystal-tweaking heathens down South. For months, he harassed them to change their name; they told him to go fuck himself. Finally, Butler capitulated: They could call themselves Aryan Nation if they studied Scripture with him. And so it came to pass: The Tennessee apostates got religion and kept selling speed to all comers. Scott busted that crew in 2018, sending 44 members to the pen. “For all their Christian bullshit, they were moving tons of product,” he says, and using the criminal proceeds to grow their base.

Asked if he’d challenged them to square the contradiction, Scott lets out a snort. “I’m talking to this neo-Nazi and said, ‘Why do y’all hate Blacks so much?’ He goes, ‘They’re lazy, and they mooch off their family and the county.’ I said, ‘OK, so where you living these days?’ ‘Um, well, right now, I’m staying by my girlfriend’s mama’s.’ ‘Right, and what do you do for work?’ ‘Well, I’m kinda between jobs at the moment.’ I just started laughing and said, ‘Is it me, or are you the very thing you just described hating?’”

If Scott had done nothing but “enterprise crimes” — drug gangs, corrupt cops, human-trafficking cases — he’d have blazed a big trail at the bureau. But he was spinning his wheels working narcotics rips and badly wanted out of that box. So in 2015, he arranged his own transfer to the Joint Terrorism Task Force in Tennessee. Created by the bureau in 1980, JTTFs are regional strike teams blending feds, cops, troopers, and linguists tracking terror threats at home. Back then, no one in Washington deemed the far-right groups a high-priority target. “For several years, our unit had been a lackluster crew, not known for having ass kickers,” says Scott. That changed in a hurry with him around. He built the case on the Aryan Nations that lasted 18 months. The windfall payoff in arrests and seizures showed DTOS — the Domestic Terror command in Washington — “that you could bring major cases against white supremacists, and that we needed more bodies” to do so, he adds.

The bureau soon doubled the size of his team; Scott spread his reach to other states. Posing as an outlaw biker, he infiltrated a Klan cell suspected of making ghost guns for sale. One night in a remote field in Scottsboro, Alabama, they blindfolded him and ordered him to his knees: He was “naturalized,” or inducted, by a green-gowned wizard. For months, he attended their Klan Kraft Klasses and played Lynyrd Skynyrd at their rallies. Scott, who shreds like a poor man’s Dave Mustaine, would get four songs in and run out of suitable numbers. “You can’t rock Hendrix for the Klan,” he says. So he’d wail Southern standards as they doused their 30-foot torch with diesel fuel.

At those Klan meetups, Scott caught wind of a man who was bent on bad intentions. “He’d post pictures of synagogues on his Facebook page and say, ‘I’m gonna do something big.’” Scott arranged to meet the man while posing as a closer. (The closer is the guy who supplies the “iron,” be it a gun or bomb for an attack.) On Jan. 12, 2017, he picked up Benji McDowell at his home in Conway, South Carolina; they drove to Myrtle Beach to talk targets. “This was right around the time Dylann Roof was on trial,” says Scott. “Benji said he wanted to do something in the style of Roof, only on a grander scale.”

Scott wasn’t sure what to make of McDowell, an overstuffed pillow of a 30-year-old stoner who came off as a soft-brained teen. Countless idiots shitpost heinous threats but lack the will or means to see them through. Scott made McDowell for one of those losers, a sense compounded when he sparked up a joint in the back seat of Scott’s sedan. “Put that out!” Scott barked at him, boiling mad. “You don’t know what I got in the trunk, or what my priors are!” McDowell was so scared that he swallowed the joint. He later threw up in a parking lot.

But that night, Scott got a call from Benji: “I want a 40-cal and hollow points.” Scott returned in February to deliver the gun — minus firing pin, of course. “He was good to go in the next week or two,” says Scott. “He had intel on an event at a temple [in Myrtle Beach] where lots of kids and families would be present.” The drop-off happened at Scott’s motel. Cops swarmed McDowell in the car park. Later, at the station, he gave a rueful confession. “I’m glad y’all stopped me when you did,” said McDowell. “I was fixin’ to do something bad.” Scott notes that McDowell got a wrist slap — 33 months in prison for an illegal weapon. “The loophole is, there’s no domestic-terror law: You can’t bust a guy for saying ‘All Jews must die.’ So you wind up working whatever charge you can just to get ’em off the street.”

He had no time to brood about sentence guidelines, though: There was another plot afoot at an industrial plant. A white man enraged at his Black superiors sought a bomb to blow up the place. Scott reached out to him through a source, posing again as a closer. But leery of leaving a voice trail, the man declined to talk. Instead, he texted Scott the thing he was after: an emoji of a bomb going ka-boom. After months of pinging from his personal phone, the perp switched his aim to the home of his bosses, who happened to be a married couple. Travis Dale Brady was pinched when he took possession of a dummy bomb delivered by the feds. “He was no wiz at op-security,” says Scott, “but stupid people kill people all the time. Like the other guy [McDowell], he had the heart and drive to do it. And last time I checked, dead is dead.”

Scott couldn’t have known it at the time, of course, but he was feeling the first tremors underfoot: a wave of white terror that built in 2017 and has been breaking on our beaches ever since. There were horrific hate-based murders in New York and Portland, Oregon, that spring. Then, come summer, the deluge: Charlottesville, Virginia. For two days, men with long guns paraded Nazi flags through the streets of that quaint town. Cops and troopers stood by, watching, as dozens were injured in a festival of hate and horror. But even the footage of James Fields Jr. plowing his Dodge into a crowd, then backing up and hitting even more pedestrians after killing Heather Heyer, didn’t center domestic terror as a frontline threat. “That whole time, I had to fight like hell to keep my Aryan Nation op alive,” says Scott. “The International Terror Section were the big dogs. We in DTOS weren’t deemed as important.”

He and his fellow agents were flummoxed. There were groups at that rally plotting mass destruction, the worst of them the Atomwaffen Division. A global gang of white boys in their teens and early twenties, they’d been baptized in fire by the teachings of James Mason, whose banned book, Siege, is a syllabus for racists. Mason, a graying neo-Nazi living quietly in northern Colorado, has been grooming sociopaths since the early Eighties. He’s one of the founding fathers of the “accelerationist” movement: a ragtag consortium of far-right ragers who think society’s on the brink of full collapse. The job of accelerationists is to speed the plow, springing attacks on people and institutions that set the stage for race war in the streets. In that banquet of blood — the “boogaloo,” as they call it — the ones with the biggest guns will prevail. Then, the terrorists can claim their caliphate: a bone-white ethnostate, armed to the teeth, that is by, for, and about the master race.

But Mason’s goons in Atomwaffen were fuzzy about their targets. One of them, Nicholas Giampa, killed his girlfriend’s parents because they didn’t want her dating a white supremacist. Another, Devon Arthurs, killed his two roommates, both Atomwaffen boys. A third member, Samuel Woodward, stabbed his date to death after a gay hookup in California.

Those slayings were the stumbles of a lethal bunch. Three members — all Marines in a cell at Jacksonville’s Camp Lejeune — were planning to take out power plants with homemade thermite bombs. They’d already formed a “death squad” and were selling no-trace rifles to conspirators around the state. A member in Las Vegas targeted a local temple; he aimed to detonate an IED, then pick off panicked congregants as they fled. These kids were such bloodcurdling posters on Gab that the feds finally acted in 2018. They sent Scott west, as part of an undercover squad, to the Destroying Texas Fest that summer. Black-metal bands with names like Satanic Goat Ritual were playing at a club in Houston; several Atomwaffen members would be there. One of the plans was for Scott, et al., to stage a “cold bump”: One of them would pick a fight with the leader, John Cameron Denton, then Scott would jump in to “save” him. As it turned out, they didn’t have to fake the brawl. Other agents infiltrated Denton’s cell and arrested him and five others for plots against reporters, Blacks, and Jews. That freed Scott for his biggest case: the seven-month op to smash the Base.

If you’re a top producer for the FBI, your career can take one of two paths. Some time in your thirties, you’re encouraged to climb the ladder by applying for the position of SSA (supervisory special agent). There’s a big bump in salary, you may get home in time for dinner, and it’s a straight shot up to the boss’s job. Alas, the great undercovers shun that route, disdainful as they are of careerist cops. “Guys like us don’t think of climbing the ladder; we crave this shit too much to want to stop,” says McAlpin, the retired UCE. Instead, stars like Scott often stay in their lane and build their brand by becoming master teachers. By the time he switched over to Domestic Terror in 2015, Scott was the tactical instructor of his division, and ran its firearms-qualification courses. He was also a tough-love mentor at the Undercover School, a two-week crucible of stress and sleep loss that breaks some of the candidates who enroll. “It’s a horrific experience because it has to be; we’re preparing you for the worst of the worst,” says Terry Rankhorn, an undercover coordinator and master instructor who retired in 2019. “You’ll have guns at your head, a rope around your neck; we’ve never killed anyone, but we’ve air-lifted students to hospitals.”

Scott was in Phoenix to train online coverts when he ran into a compadre from Ohio. He and “Jim,” a veteran cop assigned to Joint Terror, were the Hans and Franz twins of undercover: two hyper-muscled men with full-dress Harleys and enough tats to start a biker gang. Each of them had heard the buzz about the Base and wanted to get a case going fast. So one night, they bought a fifth of their favorite poison and stayed up building Scott an alias. Using fascist pen names, they made his social media a fount of Holocaust slurs. But try as they might, it proved problematic to get booted off Facebook, or “Jewbook,” as young racists like to call it. A screenshot of your ouster is a very useful chip if you’re seeking instant cred with terror groups.

So Scott took it on himself to just tag the Base directly. He wrote to the web address they posted on Gab, going by WhiteWarrior88. That night, they emailed him a questionnaire. Several days of back-and-forth led to a voice chat with some of the members, including a man calling himself Roman Wolf. Scott was asked about his combat skills and what he was willing to risk for his beliefs. Accelerationists love to boast that they’re leaderless cells, and that their crypto skills shield them from being breached. But it had taken Scott a day to reach the Base online, and a week to speak to their leader directly.

Said leader, Roman Wolf — real name: Rinaldo Nazzaro — was no blood-and-soil warlord whose hateful worldview stemmed from combat horrors. Wolf graduated prep school in New Jersey and dropped out of Villanova, where he presented himself as an anarchist opposed to government meddling. He had nothing in common with the Base kids he exhorted to “finish” what Hitler started. Those boys were dirt-floor loners in the rural South, while Wolf and his wife lived comfortably in Russia after leaving America in 2018. Everything about him sounded gassy and self-inflated, from his credentials as a mercenary in the Middle East theater to his counterterror chops at an intel firm. There is evidence that he worked for the Department of Homeland Security from 2004 to 2006, but he didn’t learn much tradecraft on the job. The firewall he built around his white-terror op has been breached, time and again, by media types. He bought land, for instance, in Washington state to stage hate camps for the Base, but the site was doxxed by a Vice reporter and swarmed by antifa types. The kids in his western cell quickly quit the group, and Wolf had to start all over in the East.

The day after his interview, Scott was asked to join the Base. Wolf put him in touch with the nearest cell leader — a guy in Rome, Georgia, named Luke Lane. “I didn’t know it then, but he was the bastard we’d been hunting under his call name, TMB [The Militant Buddhist],” says Scott. “Outta all of ’em in the cell, Lane was the most gonzo. He’d be up till dawn posting seriously crazy shit.” A week or two later, Scott drove to meet Lane near a statue of a — yes, lord — Roman wolf. Lane, 20, and Pestilence, 19, approached Scott in the standard issue of young fascists: black BDUs bloused into combat boots. Lane told Scott to put his cell on airplane mode, then wanded him with a contraption he’d never seen. “It was this detector that picks up waves from any recording device — and my team had put a tracker on my truck,” says Scott.

Two thoughts went through him in a blur: This’ll be the shortest undercover in history (it wasn’t — he’d parked under a power line, fuzzing the rod’s reception), and How are these kids buying equipment the FBI doesn’t have? That question, or something like it, came up again all weekend as he scoped out the armory they’d amassed. Each member of the Base who came to Lane’s place had a kit he could hit the ground with in Tikrit. Set aside their long guns with which they aired out Star of David targets. What stunned Scott was all their ancillary gear: bulletproof vests with ceramic plates that could stop an AK round, and loaded battle-rattles holding gas masks and mag clips and everything you’d need in a firefight. “These boys were tight,” says Scott in grudging awe. “Their shoot-and-move skills, their magazine dumps — for home-schooled dudes, they were pretty squared away.”

Scott says Lane lived on a farm that wasn’t fit for habitation. There was a house on the property encircled by trash, but that was somehow rented to a tenant. Lane and his father bunked in the loft of their converted barn, where they shared a kitchen and bathroom with Lane’s sister. The father worked construction and was gone all day, but neither his son nor Lane’s best friend had a job. Pestilence — real name: Jacob Kaderli — was an unemployed teen who somehow scrounged the cash to pay for combat gear. Helter-Skelter — real name: Michael Helterbrand — was the only Georgia member with a steady check. He worked in IT. Lane was the oddest of the three, though, says Scott: an eighth-grade dropout who’d quit school to read Mein Kampf and trade firearms online all night. Scott never saw his bedroom, but heard from the other members that it harbored an arsenal. “That’s how he had money to buy new gear,” says Scott. “Buying and selling on armslist.com.”

At night, after hours of training maneuvers and honing their Sieg Heil poses, the Base boys would sit beneath an awning by the barn, drinking Jägermeister and trading tin-foil theories. “Pestilence would be talking about the Earth being concave, that Hitler proved it by firing rockets that came down,” says Scott. “Then someone would say, ‘No, bullshit. Hitler’s living in Middle Earth, along with a race of giants.’” And Lane would declaim against the “ZOG,” or the Zionist Occupied Government [of America]. For all their pagan bluster and dreams of an ethnostate, Scott couldn’t help but ask these sex-starved boys how they planned to sire the master race. “Oh, that’s easy,” said one of them. “We’ll just kidnap bitches and rape ’em till they give us kids.”

There was a lot of this sort of thing over the next three months. Scott (rechristened PaleHorse) drove to Georgia twice a month and met his support team at their off-site. Installed in a defunct schoolhouse, the feds wired him up to record for two days straight. (They also flew a plane overhead that filmed the group’s movements from four miles up.) For 48 hours, his backups eavesdropped as the Base boys burned Bibles and U.S. flags, cut themselves to bleed on blocks of Norse runes, and raged against Jesus and “the rest of his fucking Jews.” What the feds didn’t hear were the names and dates of targets; the Georgia cell took pains to speak vaguely. Scott sensed they were hatching something, but couldn’t get them to say it. Meanwhile, his case kept getting bigger.

Sometime in August, three other men showed up; one became a fixture at the farm. He had a fringy beard and was evasive about his background, but his Manitoba twang gave him away. Patrik Mathews was a corporal in the Canadian Reserves trained in explosives who’d fled Canada after being outed as a neo-Nazi by a reporter. Half the FBI was looking for Mathews, who’d snuck across the border weeks before. Members of the Georgia cell were awed by his prowess and his commitment to the cause. Lane’s father let him stay at the farm, where, per Scott, Mathews slept in a horse stall for two months.

Then there were the other two who’d come down with him. Can’t-Go-Back — real name: Brian Lemley — was an Army vet and truck driver who’d scooped up Mathews near the border and harbored him for a while in Virginia. Eisen — real name: William Bilbrough — was another middle-earther and self-taught ninja whose martial skills weren’t worth a damn. Those three wanted to start a race war ASAP. Mathews, who’d named himself PunishSnake, had the self-assurance of the psychotic. He was, he said, “invisible,” the perfect killing machine because, as far as anyone knew, he was dead. Drunk or sober, he’d foam at the mouth about downed power lines and poisoned water supplies. That fall, when they formed their own cell in Delaware, Mathews and Lemley built a ghost gun from parts, hatched plans to assassinate cops for their weapons, and roughed out a plot on a gun rally on the Capitol steps in Virginia.

Meanwhile, Scott was under blue-flame pressure to bust the Georgia cell. It is murderously expensive to build a multistate op on a terror group that keeps growing. By October, the feds had dozens of members in their sights, and offices from New York to L.A. were opening cases against suspects in their region. Scott would man the phones once a week at 10 a.m., briefing the other teams about his progress. Sometimes, he says, “there were a hundred people on the line — and a whole bunch of backstabbing” going down. Alliances and antipathies formed between regions: “Some of us divisions were on the same sheet of music, saying ‘Where’s the imminent threat? Just play this out.’ Whereas other teams were like, ‘These guys are unstable! People are gonna die if we don’t move.’”

Well, of course, they’re unstable, Scott thought but didn’t say. That’s what I’m counting on.

It is, to corrupt Tolstoy, a truth self-evident: Every unhappy family is alike. The Base, a paranoid clan with no shared past or people skills, was rigged to explode before it fired the first shot or laid its first bomb outside a church. Scott says Lane, who’d idolized Mathews in August, was plotting to blow his brains out that fall. He’d had it with Mathews’ “fed talk” — the loosey-goosey mentions of murder and mayhem that draw the eyes and ears of the FBI. Also — and this was a problem — Mathews “knew too much,” mostly because Lane had spilled his plans to him.

That Halloween weekend, Lane and Pestilence shared those plans with Scott. Sitting around a campfire after everyone else had left, they told him to put his phone on ice. “We’ve developed targets” we’re going after, said Pestilence. Lane didn’t divulge names, but wanted to know if Scott was up for whatever. “Brothers, you know this,” said Scott. “Just tell me when and where — and give me a couple days to clear the decks.”

Just before Thanksgiving, Scott got a blast on Wire, via a channel used only by the cell. Be back here in mid-December, said Lane, and bring your whole kit “for a family-friendly camping trip.” Scott drove down there on the appointed day, making sure to arrive before the others. “Whattaya got?” he asked Lane, just the two of them by the barn. We’re gonna go whack some people, Lane whispered: an antifa couple living an hour away. “Well, dang,” said Scott, trying to stall for time. “That ain’t nothin’ I want to drive my personal truck to.” He peppered Lane with questions: Who lives in the house with them? Are there children and pets present? How close is their bedroom to the neighbors?

Lane admitted he knew none of those things; he agreed to delay the hit to do recon. “Forget it,” said Scott. “I’ll get the intel myself.” His cover job — site surveying — gave him credentials to pull deeds and housing floor plans. He slow-walked that “research” and took a stealth trip up North, training with Mathews and Lemley in Delaware. The two cells had come to truly loathe each other, and Scott worked the rift on both ends. “I don’t like the way Lane treats you guys,” he said. “We’re supposed to be on the same side.” Mathews entreated him to join their cell, then let him in on the plot.

Sitting in their flat in Newark, Delaware, Scott sipped his whiskey and nodded as they sketched it out. There was a Second Amendment rally in Virginia, they said, that figured to be a powder keg. Democrats had just taken power in the state and were planning stiff gun-control measures. While tens of thousands of people milled the Capitol steps, they’d set up in a tree line a hundred yards back and start picking off cops and troopers. A circular firing squad would spark off: Cops would shoot the gun nuts, gun nuts would shoot antifa, and bystanders would be cut down in the middle. As Scott winked at a wall cam that the feds installed while the two men were off at work, Mathews rambled on about his plans. After the rally, they’d slip away and become a roving death squad, posing as homeless men to stalk their targets. At night, gloved and hooded, they’d follow a reporter to his car, put a couple rounds in the back of his head, then move to the next city and lefty target.

Scott had gotten enough to bag the Delaware cell. But he needed a little luck now to take down the Georgia crew. It doesn’t suffice to tape people talking murder — they actually have to do something to further that plot in order for charges to stick. It was January 2020, and the window was closing fast. If Scott didn’t act before the rally in nine days, the Georgia cell would scatter once Mathews fell.

On Jan. 12, Scott drove back to Rome: Lane announced that the hit was going down. Scott’s pulse raced when he heard what they’d acquired. They had bought catch bags for their brass — sacks that clip to the ejection ports of rifles and catch the expended shells as they pour out. They had drilled a silencer for a pistol, and would go out and buy frog tape to cinch their pant legs so they didn’t leave stray skin cells at the scene. (They also said they’d grab a package of adult diapers, having heard that people shit themselves doing their first murder.) Scott, for his part, produced some images of the house, but couldn’t get the list of current tenants. “Well, whatever,” said Helter-Skelter. “If there’s kids there, let’s whack ’em. I got no problem killing commie kids.”

The original plan was for Helter to drive and the other three to go in blazing. But Helter had changed his mind: He wanted “to pop his cherry” instead of waiting in the truck. Otherwise, the blueprint remained the same. They’d rent a single room at a dive motel; there, they’d shower up, slough their dead skin off, and change into disposable murder gear. Scott would steal a truck with out-of-state plates, and someone would bring accelerants to torch the house. They’d be in and out in minutes, murder everything that moved, and leave behind a fireball for the cops.

On Jan. 15, Scott called on Lane to take him out to lunch. Driving out of the farm, he turned off the dirt road when he heard an odd noise from his pickup. “Fuck!” he said to Lane as he pulled over. “If this truck’s messin’ up on me again…”

He got out and walked to the back of the truck when another pickup passed him on the road. The driver stopped and asked Scott if he needed help. While they talked, an armored BearCat came over the hill, a gunner in the turret with an M-4. Scott and the other driver dove into the truck and tore off. A SWAT team surrounded Lane, guns drawn.

A couple of hours later, a team arrested Pestilence at his house two hours south, near Atlanta. His parents feigned innocence about their son’s intentions, but Scott claims otherwise. “Pest said he would show his dad videos of our training sessions; hell, he said his dad used to take him to the gun range.”

At five that afternoon, cops arrested Helter-Skelter as he left his IT job in Georgia. The three cell members were held without bail and booked for a raft of crimes: conspiracy to commit murder, arson, home invasion, and — eventually — animal cruelty to that goat. The next day, Jan. 16, SWAT teams in two cities rolled up Mathews, Lemley, and Bilbrough. BigSiege — real name: Yousef Barasneh — was busted with a second member for defacing houses of worship. Lanzer — real name: Richard Tobin — was charged with conspiracy in those crimes: He was the one who’d planned a nationwide assault on churches and temples. Months later, cops got ZoomGnat — real name: Duncan Trimmell — the deranged kid who’d driven all the way from Texas to take part in the Halloween gore. So, too, Dima — real name: Brandon Ashley; both were charged for beheading a goat.

In all, the bureau snared 11 members, effectively ending the group. So strong was the proof Scott gathered against them that they all took pleas and prison bids. Not so Nazzaro, the leader of the Base, who denies any part in their plots. At this writing, he sits, impregnable, at his redoubt in Russia, far beyond the reach of law enforcement. There, he recruits his next band of racists, protected by the U.S. Constitution. Still an American citizen, he has the First Amendment right to polemicize the slaughter of civilians. Does he crave the fall of government and the erasure of Blacks and Jews, or are those just the tantrums of a middle-age troll from the dark side of the moon? For all anyone knows, he’s an FSB proxy who cares only about planting false flags.

While on the subject of false flags: That antifa couple in Georgia? They were neither antifa nor a couple. Far from living together, they were total strangers who were photographed side by side at a rally. But that is what happens when you recruit child soldiers who can’t read a caption below a picture. You seed the soil for war in which everyone’s a foe, and the killers we fear the most are our own kids.