Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

In an excerpt from Gangsters of Capitalism, Jonathan M. Katz details how the authors of the Depression-era “Business Plot” aimed to take power away from FDR and stop his “socialist” New Deal

For 33 years and four months Butler had been a United States Marine, a veteran of nearly every overseas conflict back to the war against Spain in 1898. Respected by his peers, beloved by his men, he was known as “The Fighting Hell-Devil Marine,” “Old Gimlet Eye,” “The Leatherneck’s Friend,” and the famous “Fighting Quaker” of the Devil Dogs. Bestselling books had been written about him. Hollywood adored him. President Roosevelt’s cousin, the late Theodore himself, was said to have called Butler “the ideal American soldier.” Over the course of his career, he had received the Army and Navy Distinguished Service medals, the French Ordre de l’Étoile Noir, and, in the distinction that would ensure his place in the Marine Corps pantheon, the Medal of Honor — twice.

Butler knew what most Americans did not: that in all those years, he and his Marines had destroyed democracies and helped put into power the Hitlers and Mussolinis of Latin America, dictators like the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo and Nicaragua’s soon-to-be leader Anastasio Somoza — men who would employ violent repression and their U.S.-created militaries to protect American investments and their own power. He had done so on behalf of moneyed interests like City Bank, J. P. Morgan, and the Wall Street financier Grayson M.P. Murphy.

And now a bond salesman, who worked for Murphy, was pitching Butler on a domestic operation that set off the old veteran’s alarm bells. The bond salesman was Gerald C. MacGuire, a 37-year-old Navy veteran with a head Butler thought looked like a cannonball. MacGuire had been pursuing Butler relentlessly throughout 1933 and 1934, starting with visits to the Butler’s converted farmhouse on Philadelphia’s Main Line. In Newark, where Butler was attending the reunion of a National Guard division, MacGuire showed up at his hotel room and tossed a wad of cash on the bed — $18,000, he said. In early 1934, Butler had received a series of postcards from MacGuire, sent from the hotspots of fascist Europe, including Hitler’s Berlin.

In August 1934, MacGuire called Butler from Philadelphia and asked to meet. Butler suggested an abandoned café at the back of the lobby of the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel.

First MacGuire recounted all he had seen in Europe. He’d learned that Mussolini and Hitler were able to stay in power because they kept soldiers on their payrolls in various ways. “But that setup would not suit us at all,” the businessman opined.

But in France, MacGuire had “found just exactly the organization we’re going to have.” Called the Croix de Feu, or Fiery Cross, it was like a more militant version of the American Legion: an association of French World War veterans and paramilitaries. On Feb. 6, 1934 — six weeks before MacGuire arrived — the Croix de Feu had taken part in a riot of mainly far-right and fascist groups that had tried to storm the French legislature. The insurrection was stopped by police; at least 15 people, mostly rioters, were killed. But in the aftermath, France’s center-left prime minister had been forced to resign in favor of a conservative.

MacGuire had attended a meeting of the Croix de Feu in Paris. It was the sort of “super-organization” he believed Americans could get behind — especially with a beloved war hero like Butler at the helm.

Then he made his proposal: The Marine would lead half a million veterans in a march on Washington, blending the Croix de Feu’s assault on the French legislature with the March on Rome that had put Mussolini’s Fascisti in power in Italy a decade earlier. They would be financed and armed by some of the most powerful corporations in America — including DuPont, the nation’s biggest manufacturer of explosives and synthetic materials.

The purpose of the action was to stop Roosevelt’s New Deal, the president’s program to end the Great Depression, which one of the millionaire du Pont brothers deemed “nothing more or less than the Socialistic doctrine called by another name.” Butler’s veteran army, MacGuire explained, would pressure the president to appoint a new secretary of state, or “secretary of general affairs,” who would take on the executive powers of government. If Roosevelt went along, he would be allowed to remain as a figurehead, like the king of Italy. Otherwise, he would be forced to resign, placing the new super-secretary in the White House.

Butler recognized this immediately as a coup. He knew the people who were allegedly behind it. He had made a life in the overlapping seams of capital and empire, and he knew that the subversion of democracy by force had turned out to be a required part of the job he had chosen. “I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle man for big business, for Wall Street, and for the bankers,” Butler would write a year later. “In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism.”

And Butler knew another thing that most Americans didn’t: how much they would suffer if anyone did to their democracy what he had done to so many others across the globe.

“Now, about this super-organization,” MacGuire asked the general. “Would you be interested in heading it?”

“I am interested in it, but I do not know about heading it,” Butler told the bond salesman, as he resolved to report everything he had learned to Congress. “I am very greatly interested in it, because, you know, Jerry, my interest is, my one hobby is, maintaining a democracy. If you get these 500,000 soldiers advocating anything smelling of fascism, I am going to get 500,000 more and lick the hell out of you, and we will have a real war right at home.”

Eight decades after he publicly revealed his conversations about what became known as the Business Plot, Smedley Butler is no longer a household name. A few history buffs — and a not-inconsiderable number of conspiracy-theory enthusiasts — remember him for his whistleblowing of the alleged fascist coup. Another repository of his memory is kept among modern-day Marines, who learn one detail of his life in boot camp — the two Medals of Honor — and to sing his name along with those of his legendary Marine contemporaries, Dan Daly and Lewis “Chesty” Puller, in a running cadence about devotion to the Corps: “It was good for Smedley Butler/And it’s good enough for me.”

I first encountered the other side of Butler’s legacy in Haiti, after I moved there to be the correspondent for the Associated Press. To Haitians, Butler is no hero. He is remembered by scholars there as the most mechan — corrupt or evil — of the Marines. He helped lead the U.S. invasion of that republic in 1915 and played a singular role in setting up an occupation that lasted nearly two decades. Butler also instigated a system of forced labor, the corvée, in which Haitians were required to build hundreds of miles of roads for no pay, and were killed or jailed if they did not comply. Haitians saw it for what it was: a form of slavery, enraging a people whose ancestors had freed themselves from enslavement and French colonialism over a century before.

Such facts do not make a dent in the mainstream narrative of U.S. history. Most Americans prefer to think of ourselves as plucky heroes: the rebels who topple the empire, not the storm troopers running its battle stations. U.S. textbooks — and more importantly the novels, video games, monuments, tourist sites, and films where most people encounter versions of American history — are more often about the Civil War or World War II, the struggles most easily framed in moral certitudes of right and wrong, and in which those fighting under the U.S. flag had the strongest claims to being on the side of good.

“Imperialism,” on the other hand, is a foreign-sounding word. It brings up images, if it brings any at all, of redcoats terrorizing Boston, or perhaps British officials in linen suits sipping gin and tonics in Bombay. The idea that the United States, a country founded in rebellion against empire, could have colonized and conquered other peoples seems anathema to everything we are taught America stands for.

And it is. It was no coincidence that thousands of young men like Smedley Butler were convinced to sign up for America’s first overseas war of empire on the promise of ending Spanish tyranny and imperialism in Cuba. Brought up as a Quaker on Philadelphia’s Main Line, Butler held on to principles of equality and fairness throughout his life, even as he fought to install and defend despotic regimes all over the world. That tension — between the ideal of the United States as a leading champion of democracy on the one hand and a leading destroyer of democracy on the other — remains the often unacknowledged fault line running through American politics today.

For some past leaders, there was never a tension at all. When the U.S. seized its first inhabited overseas colonies in 1898, some proudly wore the label. “I am, as I expected I would be, a pretty good imperialist,” Theodore Roosevelt mused to a British friend while on safari in East Africa in 1910. But as the costs of full-on annexation became clear, and control through influence and subterfuge became the modus operandi of U.S. empire, American leaders reverted seamlessly back to republican rhetoric.

The denial deepened during the Cold War. In 1955, the historian William Appleman Williams wrote, “One of the central themes of American historiography is that there is no American Empire.” It was essential for the conflict against the Soviet Union — “the Evil Empire,” as Ronald Reagan would call it — to heighten the supposed contrasts: They overthrew governments, we defended legitimate ones; they were expansionist, we went abroad only in defense of freedom.

As long as the United States seemed eternally ascendant, it was easy to tell ourselves, as Americans, that the global dominance of U.S. capital and the unparalleled reach of the U.S. military had been coincidences, or fate; that America’s rise as a cultural and economic superpower was just natural — a galaxy of individual choices, freely made, by a planet hungry for an endless supply of Marvel superheroes and the perfect salty crunch of McDonald’s fries.

But the illusion is fading. The myth of American invulnerability was shattered by the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. The attempt to recover a sense of dominance resulted in the catastrophic “forever wars” launched in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Somalia, and elsewhere. The deaths of well over half a million Americans in the coronavirus pandemic, and our seeming inability to halt or contend with the threats of climate change, are further reminders that we can neither accumulate nor consume our way out of a fragile and interconnected world.

As I looked through history to find the origins of the patterns of self-dealing and imperiousness that mark so much of American policy, I kept running into the Quaker Marine with the funny name. Smedley Butler’s military career started in the place where the United States’ overseas empire truly began, and the place that continues to symbolize the most egregious abuses of American power: Guantánamo Bay. His last overseas deployment, in China from 1927 to 1929, gave him a front-row seat to both the start of the civil war between the Communists and the Nationalists and the slowly materializing Japanese invasion that would ultimately open World War II.

In the years between, Butler blazed a path for U.S. empire, helping seize the Philippines and the land for the Panama Canal, and invading and helping plunder Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and more. Butler was also a pioneer of the militarization of police: first spearheading the creation of client police forces across Latin America, then introducing those tactics to U.S. cities during a two-year stint running the Philadelphia police during Prohibition.

Yet Butler would spend the last decade of his life trying to keep the forces of tyranny and violence he had unleashed abroad from consuming the country he loved. He watched the rise of fascism in Europe with alarm. In 1935, Butler published a short book about the collusion between business and the armed forces called War Is a Racket. The warnings in that thin volume would be refined and amplified years later by his fellow general, turned president, Dwight Eisenhower, whose speechwriters would dub it the military-industrial complex.

Late in 1935, Butler would go further, declaring in a series of articles for a radical magazine: “Only the United Kingdom has beaten our record for square miles of territory acquired by military conquest. Our exploits against the American Indian, against the Filipinos, the Mexicans, and against Spain are on a par with the campaigns of Genghis Khan, the Japanese in Manchuria, and the African attack of Mussolini.”

Butler was not just throwing stones. In that article, he repeatedly called himself a racketeer — a gangster — and enumerated his crimes:

I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street.…

I helped purify Nicaragua for the international banking house of Brown Brothers in 1909-12. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras “right” for American fruit companies in 1903. In China, in 1927, I helped see to it that Standard Oil went its way unmolested.

During those years, I had, as the boys in the back room would say, a swell racket. I was rewarded with honors, medals, promotion. Looking back on it, I feel I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was operate in three city districts. We Marines operated on three continents.

Butler was telling a messier story than the ones Americans like to hear about ourselves. But we ignore the past at our peril. Americans may not recognize the events Butler referred to in his confession, but America’s imperial history is well remembered in the places we invaded and conquered — where leaders and elites use it and shape it to their own ends. Nowhere is more poised to use its colonial past to its future advantage than China, once a moribund kingdom in which U.S. forces, twice led by Butler, intervened at will in the early 20th century. As they embark on their own imperial project across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, Chinese officials use their self-story of “national humiliation” to position themselves as an antidote to American control, finding willing audiences in countries grappling with their own histories of subjugation by the United States.

The dangers are greater at home. Donald Trump preyed on American anxieties by combining the worst excesses of those early-20th-century imperial chestnuts — militarism, white supremacy, and the cult of manhood — with a newer fantasy: that Americans could reclaim our sense of safety and supremacy by disengaging from the world we made, by literally building walls along our border and making the countries we conquered pay for them.

To those who did not know or have ignored America’s imperial history, it could seem that Trump was an alien force (“This is not who we are,” as the liberal saying goes), or that the implosion of his presidency has made it safe to slip back into comfortable amnesias. But the movement Trump built — a movement that stormed the Capitol, tried to overturn an election, and, as I write these words, still dreams of reinstalling him by force — is too firmly rooted in America’s past to be dislodged without substantial effort. It is a product of the greed, bigotry, and denialism that were woven into the structure of U.S. global supremacy from the beginning — forces that now threaten to break apart not only the empire but the society that birthed it.

On Nov. 20, 1934, readers of the New York Post were startled by a headline: “Gen. Butler Accuses N.Y. Brokers of Plotting Dictatorship in U.S.; $3,000,000 Bid for Fascist Army Bared; Says He Was Asked to Lead 500,000 for Capital ‘Putsch’; U.S. Probing Charge.”

Smedley Butler revealed the Business Plot before a two-man panel of the Special House Committee on Un-American Activities. The executive session was held in the supper room of the New York City Bar Association on West 44th Street. Present were the committee chairman, John W. McCormack of Massachusetts, and vice chairman, Samuel Dickstein of New York.

For 30 minutes, Butler told the story, starting with the first visit of the bond salesman Gerald C. MacGuire to his house in Newtown Square in 1933.

Finally, Butler told the congressmen about his last meeting with MacGuire at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel. At that meeting, Butler testified, MacGuire had told him to expect to see a powerful organization forming to back the putsch from behind the scenes. “He says: ‘You watch. In two or three weeks you will see it come out in the paper. There will be big fellows in it. This is to be the background of it. These are to be the villagers in the opera.’” The bond salesman told the Marine this group would advertise itself as a “society to maintain the Constitution.”

“And in about two weeks,” Butler told the congressmen, “the American Liberty League appeared, which was just about what he described it to be.”

The Liberty League was announced on Aug. 23, 1934, on the front page of The New York Times. The article quoted its founders’ claim that it was a “nonpartisan group” whose aim was to “combat radicalism, preserve property rights, uphold and preserve the Constitution.” Its real goal, other observers told the Times, was to oppose the New Deal and the taxes and controls it promised to impose on their fortunes.

Among the Liberty League’s principal founders was the multimillionaire Irénée du Pont, former president of the explosives and chemical manufacturing giant. Other backers included the head of General Motors, Alfred P. Sloan, as well as executives of Phillips Petroleum, Sun Oil, General Foods, and the McCann Erickson ad agency. The former Democratic presidential candidates Al Smith and John W. Davis — both of them foes of FDR, the latter counsel to J.P. Morgan & Co. — were among the League’s members as well. Its treasurer was MacGuire’s boss, Grayson Murphy.

Sitting beside Butler in the hearing room was the journalist who wrote the Post article, Paul Comly French. Knowing the committee might find his story hard to swallow — or easy to suppress — Butler had called on the reporter, whom he knew from his time running the Philadelphia police, to conduct his own investigation. French told the congressmen what MacGuire had told him: “We need a fascist government in this country, he insisted, to save the nation from the communists who want to tear it down and wreck all that we have built in America. The only men who have the patriotism to do it are the soldiers, and Smedley Butler is the ideal leader. He could organize a million men overnight.”

MacGuire, the journalist added, had “continually discussed the need of a man on a white horse, as he called it, a dictator who would come galloping in on his white horse. He said that was the only way to save the capitalistic system.”

Butler added one more enticing detail. MacGuire had told him that his group in the plot — presumably a clique headed by Grayson Murphy — was eager to have Butler lead the coup, but that “the Morgan interests” — that is, bankers or businessmen connected to J. P. Morgan & Co. — were against him. “The Morgan interests say you cannot be trusted, that you are too radical and so forth, that you are too much on the side of the little fellow,” he said the bond salesman had explained. They preferred a more authoritarian general: Douglas MacArthur.

All of these were, in essence, merely leads. The committee would have to investigate to make the case in full. What evidence was there to show that anyone beside MacGuire, and likely Murphy, had known about the plot? How far had the planning gone? Was Butler — or whoever would lead the coup — to be the “man on a white horse,” or were they simply to pave the way for the dictator who would “save the capitalistic system”?

But the committee’s investigation would be brief and conducted in an atmosphere of overweening incredulity. As soon as Butler’s allegations became public, the most powerful men in media did everything they could to cast doubt on them and the Marine. The New York Times fronted its story with the denials of the accused: Grayson M.P. Murphy called it “a fantasy.” “Perfect moonshine! Too unutterably ridiculous to comment upon!” exclaimed Thomas W. Lamont, the senior partner at J.P. Morgan & Co. “He’d better be damn careful,” said the ex-Army general and ex-FDR administration official Hugh S. Johnson, whom Butler said was mooted as a potential “secretary of general affairs.” “Nobody said a word to me about anything of the kind, and if they did, I’d throw them out the window.”

Douglas MacArthur called it “the best laugh story of the year.”

Time magazine lampooned the allegations in a satire headlined “Plot Without Plotters.” The writer imagined Butler on horseback, spurs clinking, as he led a column of half a million men and bankers up Pennsylvania Avenue. In an unsigned editorial, Adolph Ochs’ New York Times likened Butler to an early-20th-century Prussian con man.

There would only be one other witness of note before the committee. MacGuire spent three days testifying before McCormack and Dickstein, contradicting, then likely perjuring himself. He admitted having met the Croix de Feu in Paris, though he claimed it was in passing at a mass at Notre-Dame. The bond salesman also admitted having met many times with Butler — but insisted, implausibly, that it was Butler who told him he was involved with “some vigilante committee somewhere,” and that the bond salesman had tried to talk him out of it.

There was no further inquiry. The committee was disbanded at the end of 1934. McCormack argued, unpersuasively, that it was not necessary to subpoena Grayson Murphy because the committee already had “cold evidence linking him with this movement.”

“We did not want,” the future speaker of the House added, “to give him a chance to pose as an innocent victim.”

The committee’s final report was both complimentary to Butler and exceptionally vague:

In the last few weeks of the committee’s official life it received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country There is no question but that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.

The committee said it had “verified all the pertinent statements made by General Butler.” But it named no one directly in connection with the alleged coup.

Was there a Business Plot? In the absence of a full investigation, it is difficult to say. It seems MacGuire was convinced he was a front man for one. (He would not live long enough to reveal more: Four months after the hearings, the bond salesman died at the age of 37.)

It seems possible that at least some of the alleged principals’ denials were honest. MacGuire’s claim that all the members of the Liberty League were planning to back a coup against Roosevelt does not make it so. The incredulity with which men like Thomas Lamont and Douglas MacArthur greeted the story could be explained by the possibility that they had not heard of such a plan before Butler blew the whistle.

But it is equally plausible that, had Butler not come forward, or had MacGuire approached someone else, the coup or something like it might have been attempted. Several alleged in connection with the plot were avid fans of fascism. Lamont described himself as “something like a missionary” for Mussolini, as he made J.P. Morgan one of fascist Italy’s main overseas banking partners. The American Legion, an alleged source of manpower for the putsch, featured yearly convention greetings from “a wounded soldier in the Great War … his excellency, Benito Mussolini.” The capo del governo himself was invited to speak at the 1930 convention, until the invitation was rescinded amid protests from organized labor.

Hugh S. Johnson, Time’s 1933 Man of the Year, had lavishly praised the “shining name” of Mussolini and the fascist stato corporativo as models of anti-labor collectivism while running the New Deal’s short-lived National Recovery Administration. Johnson’s firing by FDR from the NRA in September 1934 was predicted by MacGuire, who told Butler the former Army general had “talked too damn much.” (Johnson would later help launch the Nazi-sympathizing America First Committee, though he soon took pains to distance himself from the hardcore antisemites in the group.)

Nothing lends more plausibility to the idea that a coup to sideline Roosevelt was at least discussed — and that Butler’s name was floated to lead it — than the likely involvement of MacGuire’s boss, the banker Grayson M.P. Murphy. The financier’s biography reads like a shadow version of Butler’s. Born in Philadelphia, he transferred to West Point during the war against Spain. Murphy then joined the Military Intelligence Division, running spy missions in the Philippines in 1902 and Panama in 1903. Then he entered the private sector, helping J.P. Morgan conduct “dollar diplomacy” in the Dominican Republic and Honduras. In 1920, Murphy toured war-ravaged Europe to make “intelligence estimates and establish a private intelligence network” with William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan — who would later lead the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner to the CIA. This was the résumé of someone who, at the very least, knew his way around the planning of a coup.

Again, all of that is circumstantial evidence; none of it points definitively to a plan to overthrow the U.S. government. But it was enough to warrant further investigation. So why did no one look deeper at the time? Why was the idea that a president could be overthrown by a conspiracy of well-connected businessmen — and a few armed divisions led by a rabble-rousing general — considered so ridiculous that the mere suggestion was met with peals of laughter across America?

It was because, for decades, Americans had been trained to react in just that way: by excusing, covering up, or simply laughing away all evidence that showed how many of those same people had been behind similar schemes all over the world. Butler had led troops on the bankers’ behalf to overthrow presidents in Nicaragua and Honduras, and gone on a spy run to investigate regime change on behalf of the oil companies in Mexico. He had risked his Marines’ lives for Standard Oil in China and worked with Murphy’s customs agents in an invasion that helped lead to a far-right dictatorship in the Dominican Republic. In Haiti, Butler had done what even the Croix de Feu and its French fascist allies could not: shut down a national assembly at gunpoint.

In his own country, in his own time, Smedley Butler drew a line. “My interest, my one hobby, is maintaining a democracy,” he told the bond salesman. Butler clung to an idea of America as a place where the whole of the people chose their leaders, the “little guy” got a fair shot against the powerful, and everyone could live free from tyranny. It was an idea that had never existed in practice for all, and seldom for most. As long as Americans refused to grasp the reality of what their country actually was — of what their soldiers and emissaries did with their money and in their name all over the world — the idea would remain a self-defeating fairy tale. Still, as long as that idea of America survived, there was a chance its promise might be realized.

The real danger, Butler knew, lay in that idea’s negation. If a faction gained power that exemplified the worst of America’s history and instincts — with a leader willing to use his capital and influence to destroy what semblance of democracy existed for his own ends — that faction could overwhelm the nation’s fragile institutions and send one of the most powerful empires the world had ever seen tumbling irretrievably into darkness.

Twenty-one U.S. presidential elections later, on Jan. 6, 2021, Donald Trump stood before an angry crowd on the White House Ellipse. For weeks, Trump had urged supporters to join him in an action against the joint session of Congress slated to recognize his opponent, Joe Biden, as the next president that day. Among the thousands who heeded his call were white supremacists, neo-Nazis, devotees of the antisemitic QAnon conspiracy theory, far-right militias, and elements of his most loyal neo-fascist street gang, the Proud Boys. “It is time for war,” a speaker at a warm-up rally the night before had declared.

On the rally stage, the defeated president spoke with the everyman style and bluntness of a Smedley Butler. He mirrored the Marine’s rhetoric, too, saying his purpose was to “save our democracy.” But that was not really his goal. Trump, and his faction, wanted to destroy the election — to dismantle democracy rather than cede power to a multiethnic, cross-class majority who had chosen someone else. Trump lied to the thousands in winter coats and “Make America Great Again” hats by claiming he still had a legitimate path to victory. His solution: to intimidate his vice president and Congress into ignoring the Constitution and refusing to certify the election, opening the door for a critical mass of loyal state governments to reverse their constituents’ votes and declare him the winner instead. In this, Trump echoed the French fascists of 1934, who claimed their attack on parliament would defend the popular will against “socialist influence” and “give the nation the leaders it deserves.”

Trump then did what the Business Plotters — however many there were — could not. He sent his mob, his version of Mussolini’s Black Shirts and the Croix de Feu, to storm the Capitol. “We fight like hell,” the 45th president instructed them. “And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”

It was not just Trump’s personal embodiment of fascist logic and authoritarian populism that should have prepared Americans for the Jan. 6 attack. Over a century of imperial violence had laid the groundwork for the siege at the heart of U.S. democracy.

Many of the putschists, including a 35-year-old California woman shot to death by police as she tried to break into the lobby leading to the House floor, were veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Some wore tactical armor and carried “flex cuffs” — nylon restraints the military and police use for mass arrests of insurgents and dissidents. The QAnon rioters were devotees of a supposed “military intelligence” officer who prophesized, among other things, the imminent detention and execution of liberals at Guantánamo. A Washington Post reporter heard some of the rioters chanting for “military tribunals.”

Even many of those opposed to the insurrection struggled to see what was happening: that the boundaries between the center and the periphery were collapsing. “I expected violent assault on democracy as a U.S. Marine in Iraq. I never imagined it as a United States congressman in America,” Rep. Seth Moulton, a Massachusetts Democrat, wrote as he sheltered in the Capitol complex. George W. Bush, the president who ordered Moulton into Baghdad, observed: “This is how election results are disputed in a banana republic — not our democratic republic.” Watching from home, I wished Smedley Butler was around to remind the former president how those “banana republics” came to be.

A few weeks after the siege, I talked to Butler’s 85-year-old granddaughter, Philippa Wehle. I asked her over Skype what her grandfather would have thought of the events of Jan. 6.

Her hazel eyes narrowed as she pondered: “I think he would have been in there. He would have been in the fray somehow.”

For an unsettling moment, I was unsure what she meant. Butler had much in common with both sides of the siege: Like Trump’s mob, he had often doubted the validity of democracy when practiced by nonwhites. (The most prominent Trumpist conspiracy theories about purported fraud in the 2020 election centered on cities with large immigrant and Black populations.) Like many of the putschists, Butler saw himself as a warrior for the “little guy” against a vast constellation of elite interests — even though he, also like most of the Capitol attackers, was relatively well-off. Moreover, the greatest proportion of veterans arrested in connection with the attempted putsch were Marines. An active-duty Marine major — a field artillery officer at Quantico — was caught on video pushing open the doors to the East Rotunda and accused by federal prosecutors of allowing other rioters to stream in.

But I knew too that Butler had taken his stand for democracy and against the Business Plot. I would like to think he would have seen through Trump as well. Butler had rejected the radio host Father Charles Coughlin’s proto-Trumpian brand of red-baiting, antisemetic conspiratorial populism, going so far as to inform FBI director J. Edgar Hoover of an alleged 1936 effort involving the reactionary priest to overthrow the left-leaning government of Mexico. When a reporter for the Marxist magazine New Masses asked Butler “just where he stood politically” in the wake of the Business Plot, he name-checked several of the most left-leaning members of Congress, and said the only group he would give his “blanket approval to” was the American Federation of Labor. Butler added that he would not only “die to preserve democracy” but also, crucially, “fight to broaden it.”

Perhaps it would have come down to timing: at what point in his life the attack on the government might have taken place.

“Do you think he would have been with the people storming the Capitol?” I asked Philippa, tentatively.

This time she answered immediately. “No! Heavens no. He would have been trying to do something about it.” He might have been killed, she added, given that the police were so unprepared. “Which is so disturbing, because of course they should have known. They would have known. They only had to read the papers.”

A portion of the U.S./Mexico border wall. (photo: Apu Gomes/Getty Images)

A portion of the U.S./Mexico border wall. (photo: Apu Gomes/Getty Images)

“A review is underway to ensure that the activities in question during the prior Administration remain an isolated incident and that proper safeguards are in place to prevent an incident like this from taking place in the future,” Luis Miranda, a spokesperson for CBP, told Yahoo News.

CBP’s internal probe was prompted by Yahoo News’ reporting earlier this month on Operation Whistle Pig, a leak investigation targeting reporter Ali Watkins and her then boyfriend, James Wolfe, a Senate staffer. The investigation was launched by Jeffrey Rambo, a border patrol agent assigned to CBP’s Counter Network Division who was looking at whether Wolfe provided classified information to Watkins and other reporters.

As many as 20 national security reporters were also investigated during this time, according to an FBI counterintelligence memo included in the Department of Homeland Security inspector general report obtained by Yahoo News.

The DHS inspector general investigation was launched in response to an article in the Washington Post identifying Rambo as a border patrol agent who used a fake name to meet with Watkins, then a reporter for Politico. During the meeting, he questioned her about her sources and about her relationship with Wolfe, and also discussed leak investigations.

At the end of their two-year probe, investigators referred Rambo, his supervisor Dan White and a colleague Charles Ratliff for potential criminal charges including conspiracy and misuse of government computers. White was also referred for multiple potential counts of making false statements. Federal prosecutors declined prosecution, citing, among other reasons, the lack of policies and procedures governing their work.

Rambo told Yahoo News he was authorized every step of the way, and records included in the DHS investigative report show that his supervisor Dan White ordered him to expand his probe into journalists. White is still working at the Counter Network Division, and Rambo is currently employed as a border patrol agent in San Diego.

The Counter Network Division regularly investigated potential contacts, including journalists, as part of a process it referred to as “vetting.” As part of this process, the subject would be run through multiple databases, including a terrorism watch list.

The division regularly conducts database checks on reporters “to determine personal connections,” Rambo’s supervisor Dan White told investigators, according to the DHS investigation report obtained by Yahoo News.

Charles Ratliff, another CBP employee brought in to assist Operation Whistle Pig, used the vast resources and databases available to the division to build what investigators later described as a phone tree of contacts — mapping out connections between people to identify a hidden network. Such work, which was used to track terrorists, was also directed at Americans, including congressional members and staffers and journalists..

“When Congressional “Staffers” schedule flights, the numbers they use get captured and analyzed by CBP,” Rambo’s supervisor, White, told investigators.

“White stated that Ratliff “does this all the time –inappropriate contacts between people.”

Ratliff regularly compiled reports on members of Congress with alleged ties to someone in the Terrorist Screening Database, according to the investigative report obtained by Yahoo News.

CBP marshaled those same resources to identify journalists' confidential sources, which was then passed to the FBI.

Pulitzer Prize-winning Associated Press reporter Martha Mendoza was one of the journalists vetted by the Counter Network Division — targeted only because she’d reported on forced labor, one of the issues related to CBP’s work. Huffington Post founder Arianna Huffington was also swept up in its dragnet.

“There is no specific guidance on how to vet someone,” Rambo later told investigators. “In terms of policy and procedure, to be 100 percent frank there, there’s no policy and procedure on vetting.”

The Counter Network Division also investigated NGOs, members of Congress and their respective staffs. Enough Project, a nonprofit named by CBP as one of those organizations investigated by Rambo’s team, told Yahoo News it was troubled by the revelations.

“If the Enough Project was in fact targeted for ‘extreme vetting’ by a United States government agency for our work to improve mineral supply chains originating in the Democratic Republic of Congo and investigate corruption that robs the Congolese people of their country’s natural resource wealth, it would be deeply troubling,” the organization said in a statement to Yahoo News. “Such invasive and arbitrary targeting of human rights defenders would be a violation of privacy, a hindrance to this important work, and a waste of public resources.”

A CBP official who asked not to be named told Yahoo News that the National Targeting Center has put in place new procedures and training designed to ensure that the First and Fourth amendments are not being violated. The official declined, however, to specify what those measures were.

Congressional oversight committees have also begun looking into the division’s activities.

Rep. Benny Thompson, chair of the House Homeland Security Committee and Carolyn Maloney, chair of the Committee on Oversight and Reform, sent a letter to the DHS inspector general requesting the report.

“We write you regarding disturbing reports that the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Counter Network Division used government databases to “vet” journalists, government officials, congressional members and their staff, NGO workers, and others by obtaining travel records as well as financial and personal information,” they wrote in a Dec. 14 letter to the DHS inspector general.

“The Office of Inspector General (OIG) investigated at least one Counter Network Division employee, Mr. Jeffrey Rambo, who used government databases to gather information on an American journalist Ali Watkins,” Thompson and Maloney wrote the DHS, citing reporting by Yahoo News.

Chairs Thompson and Maloney requested a copy of the Office of the Inspector General report for its investigation into Rambo and any other reports related to conduct by the Counter Network Division by Dec. 21, 2021. The DHS inspector general has to date not provided the committees with the requested information, according to congressional sources.

Sen. Ron Wyden, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, which has oversight over CBP, has also requested a copy of the inspector general report, but a spokesman for Wyden said he has still not received a copy.

The inspector general did not respond to a request for comment from Yahoo News about the congressional requests.

The DHS has declined to answer any questions posed by Yahoo News about Operation Whistle Pig and the activities of the Counter Network Division. However, in a statement, the department said that DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas “is deeply committed to ensuring the protection of First Amendment rights and has promulgated policies that reflect this priority.”

“We do not condone the investigation of reporters in response to the exercise of First Amendment rights,” the statement continued. “CBP and every component agency and office in the Department will ensure their practices are consistent with our values and our highest standards.”

Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary. (photo: Stefani Reynolds/NYT)

Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary. (photo: Stefani Reynolds/NYT)

The Biden administration’s U-turn on distributing millions of COVID tests free of charge — after White House spokesperson Jen Psaki ridiculed the idea two weeks ago — is a case study in how meaningless claims of “political impossibility” often are.

Sometime during the roughly two weeks since Psaki gave her press conference, the laws of political reality appear to have shifted — and what was worthy of mockery by the White House press secretary less than a month ago seems to have been quite possible all along. Though details are still emerging, Biden administration officials this week made clear that they plan to send out half a billion free, rapid at-home tests in January. We’ll have to wait and see how the White House intends to make such a plan work, and whether or not its promised quantity of tests is actually adequate to meet needs.

What we do know is that it was always possible to make free testing available on a large scale and that, with the Christmas season in full swing, the White House’s foot-dragging represents a significant failure (even if it has essentially conceded the concept of free testing). Given the administration’s track record to date and Joe Biden’s own established preference for means-testing, it’s still possible the rollout next month will come with strings attached or needless eligibility criteria. Regardless, the case for making rapid COVID-19 tests free to anyone and everyone who wants them remains as ironclad, from a public health perspective, as it did a few weeks ago.

A bigger takeaway from the administration’s sudden pivot is that the greatest barrier to large-scale or activist state policies is quite often just plain and simple political will. The bipartisan preference for a small-c conservative approach to governance, even during a world-historic crisis, is just that: a preference, and no more bound by immovable laws than any voluntarily assumed belief system.

Examples of big institutional and policy changes that are regularly dismissed as unfeasible by political elites in both parties can frequently be seen working well in other countries, and not just in relation to COVID. Universal health care, federally guaranteed paid parental leave, publicly funded childcare, and a vast range of other transformative and popular policies would be perfectly within reach for people across the United States, were it not for organized elite and corporate opposition to them.

It’s not, of course, the case that any president can simply will such things into existence. But as even a relatively small example like that of free COVID testing shows, it is very much is the case that the realm of what’s possible is itself a political question — and that all kinds of things become decidedly more possible once people who wield power and influence stop treating them as if they were unthinkable.

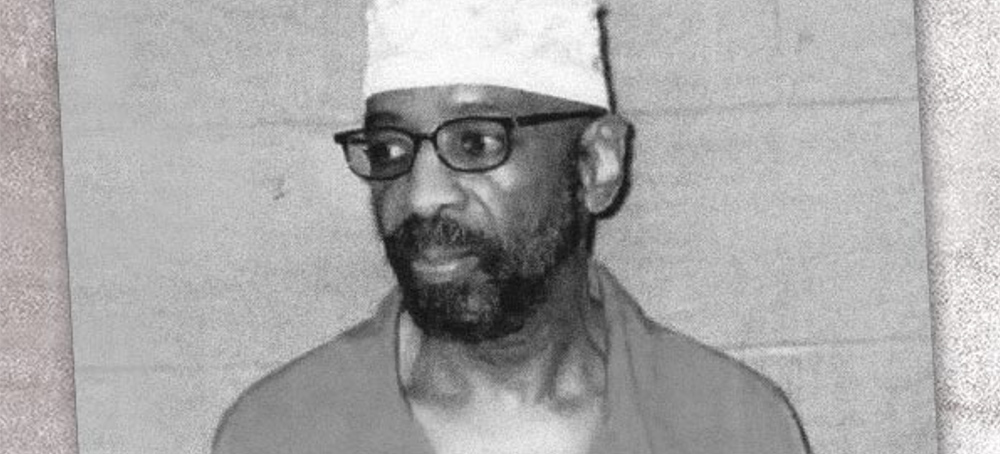

Russell 'Maroon' Shoatz. (photo: Atlanta Black Star)

Russell 'Maroon' Shoatz. (photo: Atlanta Black Star)

The death announcement on Dec. 23 revealed a judge granted him a “compassionate release” on Oct. 26 due to stage 4 colorectal cancer. The court allowed him to relocate from a Pennsylvania state prison to hospice care for treatment.

Shoatz’s son, Russell Shoatz III, spoke to the press about the prison’s inability to properly care for his father and that his release speaks to that inadequacy. He said, “What’s in the transcripts are the evidence that the prisons don’t have the capabilities to take care not just of their healthy prisoners.”

“They definitely don’t have the ability to take care of their geriatric prisoners,” he continued. “And that they have effectively killed my father.”

His funeral service and Janazah prayer were held on Monday, Dec. 20, at the Philadelphia Masjid in West Philly. He was laid to final rest at the Friends Southwestern Burial Ground in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania.

Shoatz had been incarcerated for 50 years after receiving a life sentence for an attack on a Philadelphia police station in 1970. The altercation left one officer wounded and another one dead.

Advocates working to change life without parole rules call such sentences Death by Incarceration. Shoatz dedicated much of his life to this work. In 1983, the Amsterdam News reports, he became president of the Pennsylvania Association of Lifers (PAL). This collective lobbied to abolish life-without-parole sentences and solitary confinement.

During his imprisonment, he earned the nickname “Maroon,” based on the African-Jamaican group that self-emancipated from Spanish slavery in 1655 (after the British acquired the land) and established a community in the mountains of the island. Shoatz escaped twice: once in 1977 and again in 1980. After being brought back the second time, he was placed in solitary confinement.

He stayed in solitary confinement for 22 consecutive years from 1992 to 2014.

After release from solitary confinement, he sued the Department of Corrections for cruel and unusual punishment. From the state, he received $99,000 in damages and a permanent reprieve from solitary confinement.

Protesters gather for a demonstration in front of Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections in solidarity with people incarcerated at David Wade Correctional Center on July 23, 2021, in Baton Rouge, La. (photo: Alexander Charles Adams/Intercept)

Protesters gather for a demonstration in front of Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections in solidarity with people incarcerated at David Wade Correctional Center on July 23, 2021, in Baton Rouge, La. (photo: Alexander Charles Adams/Intercept)

Officials say the total number of people in restrictive housing has gone down, but the state doesn’t keep enough data to substantiate that claim.

Officers were seeking to restrain Parker, who, along with scores of other incarcerated people, had been on hunger strike to protest solitary confinement conditions at Louisiana’s David Wade Correctional Center in July.

When he wouldn’t kneel, the officers yelled, pepper-sprayed and shackled him, and wrote him up.

The charge? “Aggravated disobedience.”

The punishment? A month and a half in solitary confinement.

The suffocating walls, the eerie darkness, and the rock-hard, stone-cold floor of the 3.5-foot by 8.5-foot cell were familiar to Parker. A year and a half earlier, in January 2020, Parker had been written up for hitting another prisoner with a broomstick at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center. Parker denied the allegations, but he was found guilty in a disciplinary hearing and was sentenced to 90 days in disciplinary segregation — a form of solitary confinement in which he would be locked in his cell for 23 hours a day.

To serve out his time, he was transferred to David Wade, which has been used as a disciplinary camp in the Louisiana prison system and is currently the subject of a class-action lawsuit that claims incarcerated people are kept in restrictive housing for extended periods of time, refused adequate mental health care, and regularly mocked and humiliated by guards. (Lawyers for the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections, or DPSC, have argued in legal filings that it provides adequate mental health care and uses restrictive housing “appropriately” to “deliver public safety” at David Wade.)

Parker was told that he would be transferred back to Elayn Hunt at the end of his 90 days.

But instead, he spent over 18 months in isolation, where he says he was denied medications for his medical conditions, stripped of his possessions — including his wedding ring — and pepper-sprayed and abused by guards.

“Pain was part of my sentence,” Parker wrote in a letter shared with The Intercept and The Lens, adding that it had taken a toll on him. “Unlike the inmates they’ve paralyzed with fear,” he continued, “I will be a voice for the frightened, the beaten, the broken, the forgotten!”

Though his time at David Wade lasted far longer than his disciplinary sentence, the fact that Parker was even given a specific sentence in the first place is the result of a new “disciplinary sanctions matrix” meant to provide a transparent rubric for punishment throughout the Louisiana prison system. Previously, prisoners could be sentenced to what was called “extended lockdown” for indefinite periods of time. Now the matrix mandates a range of punishment for specific disciplinary infractions and supposedly sets upper limits on the use of disciplinary segregation. The reform, developed in partnership with the Vera Institute of Justice — a national criminal justice reform organization — was piloted at two facilities starting in 2018 and introduced across the system in early 2020. It became official department policy in March 2021. In spite of the new policies, many prisoners, like Parker, are still facing indefinite lockdown.

Interviews with 17 people in four Louisiana prisons, reviews of individual disciplinary records, and analyses of limited data provided by DPSC show that Parker’s case is not an anomaly. Despite the limits on solitary confinement outlined in the matrix, the prison system has continued to put people in solitary confinement for indefinite periods of time for minor and ambiguously defined offenses that are often nonviolent. In letters shared with The Intercept and The Lens, more than a dozen people who were transferred to David Wade from Elayn Hunt to serve out disciplinary charges wrote that they were kept in solitary confinement long past their sentences, in dire conditions. The matrix has allowed DPSC to continue doing what it’s always done, they argued, now under the banner of reform.

DPSC records, obtained through public records requests, show that people were being held in segregation at similar rates to before the implementation of the matrix — often for nonviolent charges — and frequently for months on end. They also show that rather than being released to the general population, people are sometimes moved from disciplinary segregation to “preventative segregation.” That form of restrictive housing is not used in response to any specific disciplinary infraction but rather when a classification board determines that a prisoner is “a danger to the good order and discipline of the institution.” Practically, there is little difference between the two.

DPSC has intermittently responded to questions pertaining to the allegations made by incarcerated people and advocates regarding the matrix. In an email, a spokesperson for DPSC called Parker a “continual disciplinary problem,” noting that he has had 280 write-ups, and defended officers’ use of pepper spray as necessary to “quell a disturbance.” Seth Smith, DPSC chief of operations, granted an interview to The Intercept and The Lens in March, during which he answered questions about the matrix.

The agency did not respond to a detailed list of questions regarding the findings of this investigation, sent to them last month, until shortly after this article was published. In an email, Ken Pastorick, a spokesperson, said that the department “has dramatically reduced the overall use of restrictive housing” and that its goal “has always been, and remains, to reduce the usage of restrictive housing.”

But he said there have been “growing pains” in the process, citing Covid-19 and “resource challenges on housing and operations.” He also declined to comment further on specific allegations made by incarcerated people.

Publicly, DPSC has admitted that despite the intent of the matrix to provide clear sanctions guidelines, prisoners are frequently held in solitary confinement beyond what is called for due to lack of bed space in other less restrictive settings and inadequate staffing.

Still, prison officials suggest that the policy has reduced the number of people in restrictive housing overall. That claim, however, is hard to measure. Officials point to a 2020 study showing that the number of people held in restrictive housing in Louisiana in 2019 was dramatically lower than it had been in 2017 — data that is self-reported by DPSC and defines “restrictive housing” only as periods of solitary confinement lasting 15 days or longer.

Additionally, in spite of an agreement with Vera, Louisiana has provided data on the use of restrictive housing in only two of eight facilities since the disciplinary matrix was implemented. These two facilities represent less than half of the population being held in state prisons. The records also only cover part of the time the matrix was in effect.

In a report following the completion of the partnership in December 2020, Vera said that Louisiana prisons made “notable progress” in reducing the use of solitary but did not provide any quantitative measures showing whether or how much it has in fact declined. (In a similar report in Washington state, Vera described the percentage decreases in use of restrictive housing, the average lengths of stay, and the demographics of people placed in segregation.)

Asked to elaborate on the claim about “progress,” a Vera spokesperson said that the reforms enacted so far provide “a path” toward reducing solitary confinement but that additional reforms are necessary to “achieve substantial and sustainable segregation reduction.” In response to a question about the finding that people are being held in segregation beyond the amount of time they’ve been sentenced to under the matrix, the spokesperson reiterated that DPSC could “continue to implement reforms.”

Some advocates have long been skeptical of Louisiana’s commitment to reform. Haller Jackson, a former attorney who was released from the Louisiana State Penitentiary in June 2020 after serving a five-year sentence, described the policy as “an effort at rebranding.”

The matrix was advertised as an effort to “correct a process that was rife with due process abuse and kangaroo courts,” he said. “But as a practical matter, it hasn’t changed a damn thing.”

A “Bold Vision” for Reforms

Louisiana has been called the “prison capital of the world,” incarcerating more people per capita than any other state in a country that imprisons more of its citizens than anywhere else in the world. Its flagship facility is the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary — a former slave plantation better known as “Angola” in reference to its ancestral farmhands’ homeland.

Inside the walls of these prisons, “egregious and extensive” rates of solitary confinement for arbitrary and inconsistent reasons led to local and national calls for reform in the early 2010s.

In 2017, DPSC partnered with Vera to “develop a bold vision” for reducing solitary confinement. The organization found that between 2015 and 2016, solitary was almost four times as common in Louisiana as the national average, often used for “indeterminate and prolonged periods of time,” with conditions that were “often harmful to the health and safety” of prisoners and disciplinary processes that were “vaguely defined” and “inconsistently enforced.” The collaboration was supported by a $2.2 million grant from the Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Assistance to support Vera’s prison reform efforts in 10 states, including Louisiana.

The partnership aimed to “reduce the use of segregation by 25 percent, eliminate its use for specific vulnerable populations, reduce the length of time people spend in segregation, improve conditions in these units, and address any racial and ethnic disparities in the system’s use of segregation.”

That effort culminated in the matrix, a dense, 29-page document that enumerates 30 categories of charges that can result in placement in “disciplinary segregation” or other consequences, such as loss of visitation, wages, days off, and forfeiture of “good time.” (Good time, a form of “meritorious credit” that accrues to incarcerated individuals who avoid behavioral sanctions, can lead to reduced sentences and early release.)

Smith, of DPSC, said that the previous system led to vastly different punishment outcomes for the same violation at different Louisiana prisons: “It was very open-ended possibilities of what could happen.”

Another issue, Smith said, was that “the rulebook had no upper limits on segregation, so guys could be put there indefinitely.”

Under that system, solitary could be used for “really about close to anything,” said former Vera senior program associate David Cloud, adding that the disciplinary process was “a hot mess.” (Cloud was Vera’s lead author for a 2019 report that described the collaboration.) There was also no transparency, noted Sara Sullivan, the former Vera project head: “People had no idea why they were in solitary or how long it would be until they got out.” Cloud and Sullivan no longer work at Vera.

The goal of the matrix, Sullivan said, “was to add some consistency and transparency to that process, as well as to reduce the amount of time people were spending in restrictive housing.”

But even Vera had concerns about the specifics of the matrix. In its 2019 report, it noted that the matrix “did not explicitly reserve disciplinary segregation as a last resort for only serious acts of violence and permitted months of segregation for a range of minor and nonviolent behaviors.”

Early data suggested that the new policy “may not reduce entries into segregation as significantly as intended,” Vera warned.

“The Matrix Told Me to Do It”

Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina, said that the policy’s intent is laudable. “On paper, the matrix could be good,” she said, noting that in most prison systems, “we can’t parse out a rubric for why people are sent to solitary and how long they go for.”

But in practice, many of the enumerated offenses are poorly defined, subject to wide interpretation. Those include “work offenses,” such as failure to “perform their assigned tasks with reasonable speed and efficiency,” and “unsanitary practices,” defined as failing to uphold “as presentable a condition as possible under prevailing circumstances.” The final category, “general prohibited behaviors,” is a catchall that includes “any behavior not specifically enumerated herein.”

The breadth of the categories creates a lot of room for discretion — and potential for abuse — in the disciplinary process, said Brinkley-Rubinstein. “You can throw your hands up and say, ‘The matrix told me to do it.’”

In interviews, people who’ve been sentenced to disciplinary segregation under the matrix described how it has worked in practice.

Dominick Imbraguglio was sentenced to two days in solitary confinement at Angola in February 2020 after being caught with what officers believed was a lock pick. Inexplicably, those two days turned into more than a year. Then, in May 2021, his confinement was renewed for “original reason of lockdown,” according to his disciplinary record. He has now spent 22 months in disciplinary segregation, said his wife, Krystal Imbraguglio, even though the matrix prescribes a 365-day maximum for time spent in solitary confinement.

Imbraguglio has a history of anxiety, depression, and ADHD, and he’s on a daily drug combination of antidepressants, sedatives, and antipsychotics. In recent months, he’s been plagued by phantom voices and visual hallucinations — symptoms that can result from prolonged solitary confinement — but says that he’s been denied treatment. “It’s mental torture, pure and simple,” said Krystal. “Dom’s pain is only scratching the surface to a much larger pile of injustice and corruption here.”

Frederick Ross, who is incarcerated at Angola, was sentenced to three days in solitary confinement in March 2020 for masturbating in his cell (officially sentenced for “sexual offenses” or “disorderly conduct,” defined as “all boisterous behavior”). But despite being “overwhelmed with the segregation,” Ross — who has depression and a history of self-harm — said that he was denied mental health care while in solitary. (In March, a federal judge found that Louisiana prison officials had violated the constitutional rights of people with disabilities, including mental illnesses, by not providing adequate health care at Angola.) Instead, he was placed alone in a “timeout tank” under video surveillance. Later, Ross said, he began to “spiral out of control,” fighting with other people. His segregation was subsequently extended to 395 days, he said.

Even after his sentence was formally finished, Ross said that his charges were “renewed” due to lack of bed space. (Angola’s general population units were over capacity throughout 2020. No 2021 data is available.) As of this writing, he’s spent over 600 consecutive days in segregation. When asked about Ross’s allegations, DPSC admitted that he was in fact kept in restrictive housing due to limited bed space.

Aljerwon Moran was sentenced to 15 days in disciplinary segregation after a violent altercation with another incarcerated person at Angola last November. It was the first time he was disciplined for a violent offense; he said the fight was started by the other person in what he believes to be retaliation for months of self-advocacy against what he called “death-threatening” conditions due to Covid-19. Officially, he was sentenced for “defiance” (defined as efforts to “obstruct, resist, distract, or attempt to elude staff”) and “aggravated disobedience.”

In segregation, he was placed in a cell with soiled linens and an overflowing toilet, he said. After requesting a move, he said that prison guards placed him in a shower, sprayed him with Mace, wrestled him to the ground, nearly suffocated him by putting a knee on his neck, and dragged him by handcuffs. He was subsequently charged $16.55 for the Mace and a torn jumpsuit, appearing in court a week later with a black eye and bruises across his face.

Incarcerated people also say that under the matrix, they were sent to solitary confinement without ever being told why.

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, Quierza Lewis spoke out against the Angola administration about Covid safety concerns, including lack of masks, distancing precautions, and testing. In August 2020, Lewis was thrown in solitary confinement for over a month — officials told him that he was under investigation as a “terroristic threat,” he said. He had four disciplinary hearings, his record shows, but he said that he didn’t receive a notice before any of them; that he wasn’t permitted self-representation or witnesses; and that he did not know or ever hear from his counsels — the incarcerated people appointed by the board to act on his behalf. To date, he’s received no documentation explaining his confinement, contrary to DPSC policy.

“It’s inhumane, it’s unconstitutional, and it’s a death trap,” Lewis said of the matrix.

Lack of Visibility

According to Louisiana’s contract with Vera, DPSC was supposed to hand over statewide data on the use of segregation from April 2019 through September 2020 so that the organization could analyze the efficacy of the new policy. The Intercept and The Lens made multiple requests for this data; in response, Pastorick, the DPSC spokesperson, said that the department does “not have a document that has that information in it, and we do not create reports with that.”

DPSC’s failure to keep consistent records created obstacles for the Vera team. Sullivan, the former Vera project lead, said that the organization was “very challenged to get administrative data” from the department when the matrix was rolled out. “Louisiana’s data collection procedures are not really centralized — it’s mostly at the facility level, and it’s not particularly consistent between facilities. We got data from some, but not others,” she said. “It has greatly limited our ability to assess the success of the reforms.”

Ultimately, DPSC provided Vera with data from only two facilities: Angola and Raymond Laborde Correctional Center, or RLCC. The provided data covered July 2019 through December 2020 at Angola and June through November 2020 at RLCC. But the state didn’t release any prior-year data that could allow researchers to see whether things had changed at those facilities. Pastorick attributed DPSC’s failure to report the numbers to the Covid-19 pandemic, “which limited time and resources to respond.”

The Intercept and The Lens obtained those records through a public records request and found that over three-quarters of the placements in disciplinary segregation at RLCC were due to nonviolent offenses. They also show that the proportion of people in restrictive housing at that prison hardly budged during the five months captured by the records — and the number of people backlogged remained the same. Those placed in segregation typically stayed between three and five months, the records show.

The records from Angola, meanwhile, reveal that it was exceedingly common for people to be held in restrictive housing beyond the time they were sentenced to under the matrix.

Between January 2020 (when the matrix was first piloted at Angola) and October 2020, the number of people who were supposed to be held in restrictive housing based on their disciplinary sentences outlined in the matrix decreased by about 70, but the number of people held in solitary actually increased. By October, over half of the people being held in restrictive housing at Angola — nearly 200 individuals — were being held beyond their disciplinary sentences. (After this story was published, DPSC said that the number of people currently backlogged at Angola is down to 35.)

The majority of those backlogged were waiting to be moved to preventative segregation, where they would still be held in their cells for over 23 hours a day.

The numbers support the allegations made by Kermit Parker and others: Stays in solitary confinement were functionally indefinite.

Yet several incarcerated people who have sought recourse for their experiences under the matrix — and for the putative violation of their rights — said they’ve had no luck. Moran, Lewis, Ross, and others said they filed grievances and appeals that were ignored or rejected for a number of reasons (including having “failed to provide any clear and convincing evidence to substantiate your allegation of cruel and unusual punishment”) or for no clear reason at all.

Moreover, incarcerated people appointed to provide legal counsel to their peers said that they have faced retaliation for filing formal complaints through the prison’s administrative remedy procedure, or ARP. On March 15, 2021, three people — Lawrence Kelly, Ned Biagas, and Warren Holmes — were placed in solitary confinement after a highly ranked official “stormed in [to the legal aid office] wanting to know who had helped file somre [sic] ARP’s that he was holding in his hand,” Kelly wrote in an email. The legal aid office was subsequently closed entirely, Kelly said.

In its report at the end of its collaboration with DPSC, Vera wrote that the data it did receive “is in no way a reflection of segregation across the system.” The report continued: “The department can only address segregation issues if they know how they are using the practice.” The report also notes that under the matrix, “several frequent and non violent infractions can still land incarcerated people in segregation.”

Cloud, who left Vera in December 2019, said hearing that much has remained the same “makes you feel that the problems are much bigger than any bureaucratic tweaks we can make.”

“I guess I’m really not that shocked,” he added. “It’s like that stupid adage: Shit’s changed, but nothing’s changed.”

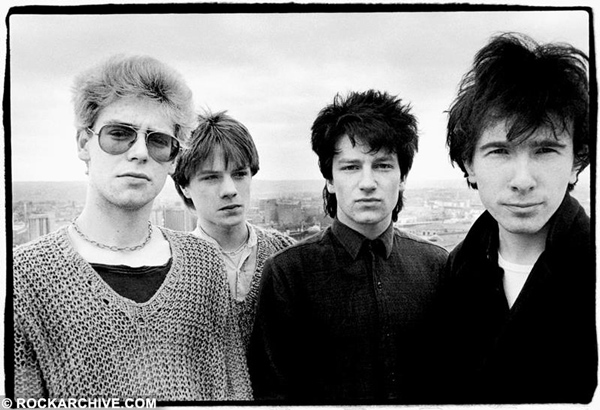

U2 (Bono, The Edge, Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen Jnr.) Cork, Ireland, circa 1980. (photo: David Corio)

U2 (Bono, The Edge, Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen Jnr.) Cork, Ireland, circa 1980. (photo: David Corio)

Lyrics U2 New Year's Day.

Written by, U2 colaborative effort.

From the 1983 album, The Unforgettable Fire.

Yeah

All is quiet on New Year's Day

A world in white gets underway

I want to be with you

Be with you, night and day

Nothing changes on New Year's Day

On New Year's Day

I will be with you again

I will be with you again

Under a blood red sky

A crowd has gathered in black and white

Arms entwined, the chosen few

The newspapers says, says

Say it's true, it's true

And we can break through

Though torn in two

We can be one

I, I will begin again

I, I will begin again

Oh, oh

Oh, oh

Oh, oh

Oh, oh

Oh, oh

Oh, oh

Oh, oh

Ah, maybe the time is right

Oh, maybe tonight

I will be with you again

I will be with you again

And so we're told this is the golden age

And gold is the reason for the wars we wage

Though I want to be with you

Be with you night and day

Nothing changes

On New Year's Day

On New Year's Day

On New Year's Day

California Conservation Corps firefighters watch a fireline at the Bear fire near Oroville in September, 2020. Founded in 1976, the youth corps now has more than 1,500 members. Fighting fires is an increasing part of their work. (photo: Max Whittaker/NYT)

California Conservation Corps firefighters watch a fireline at the Bear fire near Oroville in September, 2020. Founded in 1976, the youth corps now has more than 1,500 members. Fighting fires is an increasing part of their work. (photo: Max Whittaker/NYT)

The California Conservation Corps shows what a national Civilian Climate Corps might achieve: a big win for the environment and meaningful work for youth—outdoors.

Even in the downpour, eight-foot-high piles of just-ignited woody debris burn fiercely, their crackling accompanied by the constant whine of chainsaws. The 14 members of the California Conservation Corps’ Tahoe Fire Crew No. 1 are felling hundreds of blackened “hazard trees” marked with orange spray-painted numbers. At risk of toppling, they need to be cut down before workers can clean up the zone.

A warning is called—“Second cut. Tree falling!”—and another 80-foot-tall dead pine drops across the road.

Working in the mud among piles of logs and stumps, the blue-helmeted corps members are soaking wet and grime-streaked. The chainsaw operators wear dark Kevlar chaps and yellow jackets stained with dirt and wet sawdust.

“We’re sure living up to the promise,” 21-year-old crewmember Elizabeth Wing says with the bare hint of a smile. The “promise” is the official motto of the California Conservation Corps: “Hard work, low pay, miserable conditions, and more.”

“I’ve had a lot of crappy jobs, but not this one,” explains Martin Castellon, who was raised in Tijuana and San Diego, and spent his 26th birthday shoveling snow for the corps. “Sure, we have some crappy conditions. But it makes you appreciate it all the more.”

As part of the Build Back Better plan that is currently stalled in Congress, President Joe Biden has called for the creation of a national Civilian Climate Corps to improve the environmental resilience of the United States, while providing good jobs for hundreds of thousands of young Americans. Even at the national level, the basic idea isn’t new. In 1933, during the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps that, in its nine years of operation, employed three million young men—it excluded women and most Blacks—and built the trails and infrastructure of the country’s national parks. The corps would later provide a pool of trained and disciplined troops to serve in World War II.

Adapting Roosevelt’s model but making it more inclusive, former California Governor Jerry Brown established the California Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1976, during the early days of the environmental movement and his own first stint as governor. Today “the Cs” (as members call the corps) recruits young men and women between 18 and 25 years old. It has more than 1,500 members working out of 24 centers across the state.

Changing lives

CCC members come from a wide range of backgrounds. They used to work in retail, construction, machine shops, restaurants, tire stores. Some have completed some college. Most wanted something more.

“I was just drifting job to job and wanted to be part of something larger than myself,” says 26-year-old Louie Valez. “I saw an ad on Facebook and just jumped and haven’t looked back since.” This past summer his fire crew was at the Dixie fire for two months and the Caldor fire for a month, working long shifts—sometimes 24 hours—protecting houses. “It has been wild,” he says.

If new corps members don’t have a high school degree (about 15 to 20 percent don’t), they’re required to get one through one of the charter school partners that hold classes at the CCC’s residential and non-residential centers. That adds 10 hours of classroom work to their 40-hour work week. Those who complete at least a year in the program also qualify for up to $8,000 in scholarships for college or professional training. Even their “lousy pay” was improved in October—boosted from $1,905 a month to $2,265.

Climate change, which has led to more frequent, more intense fires around the world, has significantly affected the California corps. Five years ago, members mostly had jobs in forestry, energy, transportation, fisheries, and the culinary arts; only one crew was dedicated to firefighting. Now, 400 CCC members, more than a quarter of the corps, form 12 crews that work with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire).

At the height of the state’s fire season in September, the CCC had 40 crews at CalFire base camps, rolling hoses, restocking supplies, helping with water and meals, collecting trash and more. Twenty-six fire crews were also on the front lines clearing fire breaks with chainsaws and hand tools.

Corps members are also trained in flood control, ready to fill and strategically place tens of thousands of sandbags during the next major deluge.

Climate change “wasn’t our focus 35 or 40 years ago, but the environment has always been,” notes CCC director Bruce Saito. He hopes the California corps—along with 130 similar state and local organizations—will be integrated into Biden’s Civilian Climate Corps, if it comes into being. With 45 years of field experience, the California corps could offer valuable lessons to a national one.

Creating conservationists

While CCC members join for a wide variety of reasons, once involved in the work many develop an environmental ethic.

“If you’d asked me two years ago what a conservationist is, I’d have had no idea,” says Naomi Muratalla, who works out of a center in Stockton that covers the Sacramento Delta. “At 19, I was working as a caregiver for elderly folks with disabilities, and it was kind of overwhelming. I joined the [CCC] program and moved into a residential center. You work with the people you live with, and now my crew’s like my family.

"Honestly, it’s changed my life. I thought I wanted a medical career but now I want to build trails and plant trees, and in 20 years I can come back and say, I planted this grove.”

Wearing heavy leather gloves, Muratalla uses a pick and shovel to fit river rocks into a pathway at the Micke Grove Zoo, in a county park in the agricultural town of Lodi. Her crew is reconfiguring a turtle pond to include a butterfly garden. Another crewmember in waders stands in the pond varnishing a wooden visitor overview they have rebuilt. The turtles wait in big blue tubs in a nearby enclosure.

“The thing is with the Cs, it’s not a bunch of troubled youth like a lot of people think,” says John Alviso, 24, a fire crew member and former U.S. Army reservist. “It’s people who want to learn and get a career and are willing to work hard to do that.”

The physical effort is a big draw for some corps members. “I was going to art school online and living in my parent’s attic in the Bay Area and I just wanted something more active,” Wing explains. She ended up in the CCC’s Backcountry Trails Program, where crews spend an average of six months fixing hiking trails in the most remote parts of the state.

Not just fires

Aside from fires, the Cs have responded to other kinds of disasters over the years, including earthquakes, the Los Angeles riots, and floods. Since the onset of the COVID pandemic, the state has sent corps members to staff food banks and vaccination centers. CCC members also have responded to out-of-state disasters in Iowa, Nebraska, Texas, Louisiana, and Puerto Rico.