Live on the homepage now!

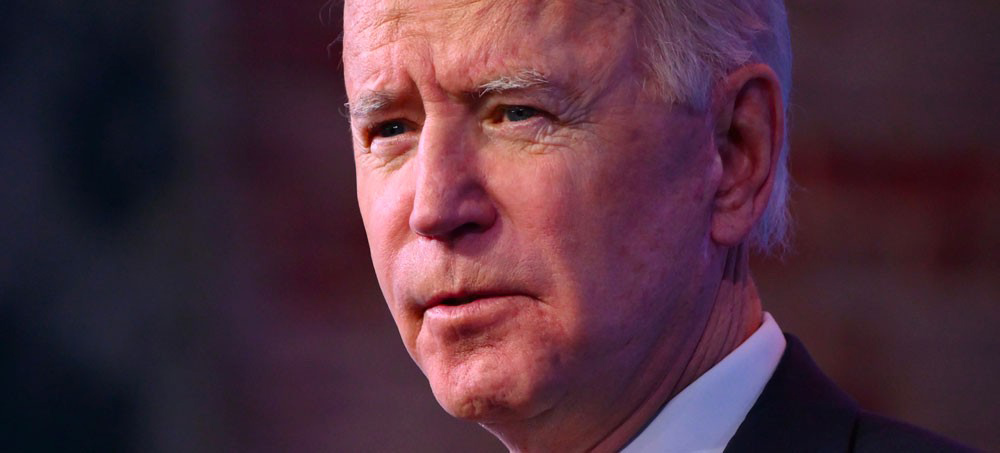

When US President Joe Biden says, “I don't know whether we can get this done But one thing for certain, like every other major civil rights bill that came along, if we miss the first time, we can come back and try a second time.” There seems to be an acceptance that the Democratic Party has failed and that it is time to move on. But this is not a problem the United States can move on from. To say that it is now acceptable to restrict the ability of certain ethnic groups to vote, specifically African Americans is to cast the nation back a hundred years to its darkest days of segregation. This will cause in today’s America a major ever widening social calamity with the potential for vast social unrest. But restricting the rights of Black voters is just one component in the broad matrix of steps planned by conservative activists, lawmakers and law enforcement sympathizers to end voting and elections as Americans have known them. From state’s legislatures granting themselves the authority to flatly ignore popular vote counts and determine election winners by legislative fiat to the threatening and intimidating of election workers across the country to the crafting a wide array of laws to selectively thin the ranks of opposition voters. This is a full scale frontal assault on free and fair elections in the United States of America. It’s not going under the radar it’s coming directly to a polling place near you in broad daylight. The two pieces of legislation under consideration by Democrats in Congress, the For the People Act (HR1) and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act (HR4) will not stop all the anti-democracy plots underway, but they will form a defendable bulwark for attorneys and election workers on the front lines. At this stage two US Senators, Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona are holding open the door for the assault by thwarting the legislative efforts of 269 of their fellow Democrats. So far both President Joe Biden and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer have been willing to afford their two antagonists the substantial grace and courtesy traditionally granted to members of the Senate. But it is neither required nor apparently at this stage productive to continue doing so. Should Biden and Schumer grow weary of their frustration they can apply significant additional pressure and if necessary they can make it personal and painful. So far Uncle Joe has been operating under the mantle of “Healing the soul of the nation.” But there is another chapter in the playbook titled, “Do damage.” Make no mistake about it, this is going to get rough — big time, for sure. Punches are going to get thrown, oxen are going to get gored and that may be just the beginning, damage will get done, you can be absolutely certain. Biden and Schumer need to get serious about a plan to win a battle that the country cannot afford to lose and it isn’t likely to be pretty. Marc Ash is the founder and former Executive Director of Truthout, and is now founder and Editor of Reader Supported News. Reader Supported News is the Publication of Origin for this work. Permission to republish is freely granted with credit and a link back to Reader Supported News.

Officials say there is no ongoing threat to the community. A 911 call came in at 10:41 a.m. after a gunman entered the Congregation Beth Israel synagogue during services and took four people hostage, Colleyville Police Chief Michael Miller said Saturday evening. Law enforcement called in a SWAT team and negotiators talked with the hostage-taker throughout the day. The man released one hostage around 5 p.m. local time. "It's very likely this situation would have ended very badly early on in the day had we not had professional, consistent negotiation with the subject," FBI Dallas Special Agent in Charge Matt DeSarno told reporters. A special FBI hostage rescue team flew in from Quantico, Va., Miller said. The team moved in at 9 p.m. and rescued the three remaining hostages and the suspected hostage-taker was left dead. Some 200 law enforcement personnel took part in the operation, police said. "Prayers answered. All hostages are out alive and safe," Texas Gov. Greg Abbott wrote on Twitter late Saturday. "We're thankful that this came to a very positive resolution," police chief Miller said. The hostage-taker was heard on a livestream of the Shabbat service A Shabbat service was scheduled at the Congregation Beth Israel at 10 a.m. A Facebook livestream of the service ended just before 2 p.m. The stream did not feature people on screen, but a man could be heard, speaking loudly and angrily at times. The Associated Press reported that the man was heard on the livestream demanding the release of Aafia Siddiqui, a Pakistani neuroscientist serving an 86-year sentence in a Texas prison. Siddiqui was convicted in 2010 of shooting at U.S. soldiers and officials in Afghanistan after they arrested her on suspicion of terrorism in 2008. Law enforcement officials would not confirm the suspect's identity, motives or demands, saying it was an ongoing investigation but there was no indication of any ongoing threat. DeSarno said the man was "singularly focused on one issue" in his demands and it was not specifically related to the Jewish community. The long history of antisemitic attacks The incident spurred memories of the long history of antisemitic attacks in the U.S. and around the world, including in recent years when a man opened fire on congregants at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018, killing 11 people. The Dallas Police Department deployed additional patrols to Dallas synagogues and other sites, Mayor Eric Johnson said Saturday. President Biden thanked law enforcement for the rescue operation. "There is more we will learn in the days ahead about the motivations of the hostage taker," Biden said in a statement. "But let me be clear to anyone who intends to spread hate—we will stand against anti-Semitism and against the rise of extremism in this country."

Electoral analysts had said the Republican-backed map would ensure the party won at least 12, and perhaps 13, of the state's 15 congressional seats, in part by splitting Cincinnati's county into multiple districts to dilute Democratic voting power there. In a 4-3 decision, the state's high court found that the map violated new provisions in the Ohio Constitution that were approved by voters in 2018, including language that prohibits any map that "favors or disfavors a political party or its incumbents." "When the dealer stacks the deck in advance, the house usually wins," Justice Michael Donnelly wrote for the majority. "That perhaps explains how a party that generally musters no more than 55 percent of the statewide popular vote is positioned to reliably win anywhere from 75 percent to 80 percent of the seats in the Ohio congressional delegation." The court's three Democrats were joined in the majority by Chief Justice Maureen O'Connor, a Republican. Three Republican justices dissented from the decision, arguing that the court was encroaching on the authority of the state legislature. Under U.S. law, states must redraw congressional lines every 10 years to account for changes in population. In most states, legislatures oversee the process, leading to the practice of gerrymandering, in which one party engineers political maps for partisan advantage. There are more than a dozen pending lawsuits challenging congressional maps in several states. In North Carolina, a three-judge panel earlier this week rejected Democratic claims that the state's new congressional map illegally favored Republicans, though the plaintiffs are appealing the decision to the state Supreme Court. Republicans need to flip only a few seats in the Nov. 8 elections to retake control of the U.S. House of Representatives, where Democrats hold a 221-212 edge including vacancies. Two days ago the Ohio Supreme Court also invalidated Republican-drawn maps for the state legislature's two chambers, finding they, too, were unconstitutional gerrymanders. The office of Republican Governor Mike DeWine, who approved the map, did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The state's Republican legislative leaders could not immediately be reached for comment.

Insider's investigation of financial disclosures found that 52 members of Congress and at least 182 of the highest-paid Capitol Hill staffers were late in filing their stock trades during 2020 and 2021. Lawmakers and senior congressional staffers who blow past the deadlines established by the 2012 Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act are supposed to pay a late fee of $200 the first time. Increasingly higher fines follow if they continue to be late — potentially costing tens of thousands of dollars in extreme cases. But accountability and transparency are decidedly lacking. No public records exist indicating whether these officials ever paid the fines. Congressional ethics staff wouldn't confirm the existence of nonpublic ledgers tracking how many officials paid fines for violating the STOCK Act. And 19 lawmakers wouldn't answer questions from Insider about whether they'd paid a penalty. Ten other lawmakers said they'd paid their fines, but they declined to provide proof, such as a receipt or canceled check. This lack of transparency makes it impossible to independently determine whether STOCK Act lawbreakers truly face consequences, and if so, to what degree. It's a situation that ethics experts say leaves the public in the dark, lets Congress off the hook, and renders the STOCK Act — intended to promote transparency, extinguish conflicts of interest, and defend against insider trading — toothless. It also shows how Congress sets a lower standard for itself on financial conflict-of-interest matters than on other concerns. For instance, consider that the House routinely issues automatic fines when members violate COVID-19 mask mandates and makes the information public. But when it comes to a member's personal finances, the House doesn't do a particularly good job of policing itself on a law it helped write. "The enforcement of the financial-disclosure requirements is virtually nonexistent," said a former investigative counsel in the House's independent Office of Congressional Ethics, who was granted anonymity in order to speak candidly. Even some federal lawmakers say change is needed. "From a transparency standpoint, it would be helpful to have that information be public," said Democratic Rep. Abigail Spanberger, of Virginia, who introduced the TRUST in Congress Act, which would require members of Congress to place certain personal investments in a blind trust. "I don't have a sense of how much it is being enforced." Congress is significantly more opaque than other parts of the government when it comes to the personal financial interests of its members and staffers. The federal government's executive branch, for example, publicly releases details about the fines it collects from employees who filed financial documents late. As conceived, the STOCK Act is supposed to encourage members of Congress and their top aides to think twice about their personal financial trades, knowing they'd be subject to greater oversight by the public and their colleagues. When they disclose information months or even more than a year later, it becomes difficult to scrutinize their actions. "The transparency provision allows us to find incidents of potential misdeeds," Spanberger said, "but that transparency only works if people abide by the rules." Penalty payments rest on an 'honor system' Under the STOCK Act, lawmakers and their senior staff who earned at least $132,552 a year in 2021 must report stock trades of more than $1,000 within 30 days of the transaction — or within 45 days if they didn't learn about the trade until a little later, often because it was made by a broker or spouse. If they file their disclosures more than 30 days after their due date, then they have to pay a late fee in the form of a check to the Treasury or apply for a waiver. The waiver process operates like an appeal. It gives people the opportunity to explain why they were late and to ask Senate or House committees to be excused from the penalty. The notification and collection of late fees differ in the Senate and House. Senate staffers who file their disclosures late receive an email from the lawmaker-led Senate Select Committee on Ethics telling them to pay the late fee or to apply for a waiver, according to a copy of such an email reviewed by Insider and interviews with staffers. The Senate Ethics Committee didn't respond to questions about how often this happens, how closely staff monitor filings, or whether senators also receive emailed notifications. Over in the House, members and senior staff who are late filing their stock trades do not receive emailed notifications alerting them to the issue. Instead, the burden falls on the lawmaker or staffer to notice they're late and then notify the committee. The former investigative counsel at the Office of Congressional Ethics described the late-penalty-compliance process on the House side as "not the simplest thing in the world." "The committee does not look for late filings. There is no notification or follow-up," the person said. "If you are late and beyond the grace period, you actually have to start making a bunch of calls to figure out how to pay the fine. The instructions aren't even on the ethics-committee site. And then you have to walk the check down." A senior congressional aide who requested anonymity to candidly discuss House procedures confirmed that members did not get notifications when they were late. Instead, they explained, each member office was expected to figure out not only whether they were late but also how to pay the late fee. "This entirely depends on the honor system," the aide said. Little transparency Without the existence of a public ledger, Insider sought to confirm through other means whether members of Congress and their top aides were paying late fees as the law requires. Reporters reached out to all 49 members of Congress who filed their information late. Of the total, 13 had filed their disclosures within a 30-day grace period, meaning they were late, but not late enough to face a fine. Of those who remained, 13 members said they'd paid the penalty. But only four of them — Democratic Rep. Lori Trahan, of Massachusetts, Democratic Rep. Mikie Sherrill, of New Jersey, Democratic Rep. Kim Schrier, of Washington, and Republican Rep. Blake Moore, of Utah — provided documentation to Insider proving that they'd written and dropped off a check for a late fee. Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly, of Arizona, provided Insider with a document that showed he requested and received a waiver to avoid paying the late filing fee. The senator requested the waiver because he had moved an "asset he already held into his newly established, ethics-committee-approved qualified blind trust," his spokesperson said. It's unclear whether any of the checks for late fees made it to the Treasury. Attempting to determine whether they did involved months of inquiries. In July, Insider filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Treasury that asked for records of "all fees and/or fines paid to Treasury by members of the US House of Representatives, members of the US Senate, and congressional employees." Initially, the Treasury's Bureau of the Fiscal Service deemed the request "too broad for the Fiscal Service to conduct an adequate search." Insider then asked the Treasury to produce fine-payment records for 22 specific members of Congress known to have recently violated the STOCK Act's disclosure provisions. Treasury officials searched its systems for evidence of payment. "We found no matches," said Thomas E. Santaniello, the manager of FOIA and Legislative Affairs for the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, who referred additional questions to the House and Senate ethics committees. Insider sought an explanation from Tom Rust, the staff director and chief counsel for the House Ethics Committee. But he declined to comment on the fine procedures or say who had or hadn't paid fines. Congress' Legislative Resource Center declined to comment on whether the office received late fees or kept a record of such payments. Sen. Chris Coons, of Delaware, a Democrat who chairs the Senate Select Committee on Ethics, and Sen. James Lankford, of Oklahoma, the top Republican on the committee, declined to comment on whether there was a record of lawmakers or staff who received fines for violating the STOCK Act. Coons told Insider to direct other questions to Shannon Kopplin, the chief counsel for the Senate Ethics Committee, but she didn't respond. Not a top priority for ethics officials Insider shared its findings with Democratic Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, of New York, who championed the passage of the STOCK Act under President Barack Obama and has pushed to make it stronger. Gillibrand said she wasn't surprised that some people weren't following the law. But they must realize that they're duty bound to report their transactions, she said. "They certainly should be fined, and they should be paying their fines," Gillibrand said. "I would like to see more oversight on that." Sen. Jeff Merkley, of Oregon, a Democrat who — like Gillibrand — wants to ban Congress from trading individual stocks, said that if the general public can't see who's paying fines, then lawmakers won't take the issue seriously. "That $200 fine may not be a huge amount to many of our members, but it should be routinely, emphatically enforced," Merkley said. "No excuses." Politicians should "play by the same rules as everyone else," Eric Schultz, senior advisor to Obama, said in a statement to Insider. "Mistrust of government runs very deep these days, and only when lawmakers hold themselves to a high standard can we start to rebuild that trust," Schultz said. On the House side, some of the late-filing violations get looked into by the Office of Congressional Ethics, an independent investigative agency. No similar office exists on the Senate side. Investigators at the Office of Congressional Ethics examine allegations of misconduct when they receive complaints or otherwise flag potential ethics violations. They make their investigation public in most cases only if they determine they have reason to believe wrongdoing occurred. But it's the House Committee on Ethics — made up of House members — that decides whether to pursue the Office of Congressional Ethics' findings. These elected officials have the power to reprimand lawmakers, discipline staffers, or do nothing at all. Between its creation in 2008 through the end of October 2021, the Office of Congressional Ethics initiated 226 investigations, a government report showed. Most of the investigations have targeted issues, such as campaign finances, travel expenses, and official allowances. In the fiscal year 2020, 4% of its overall investigations involved financial disclosures. At least one of the investigations became public this year. In October, investigators determined that Democratic Rep. Tom Malinowski, of New Jersey, failed to properly report dozens of stock trades from 2019 and 2020 that together were worth at least $671,000 and as much as $2.76 million. The House Ethics Committee said it was reviewing the matter, and Malinowski has since placed his money in a qualified blind trust, which the House Ethics Committee approved. Naree Ketudat, Malinowski's spokesperson, said the congressman paid a $200 fine for filing late, but then when he attempted to pay another one, the clerk's office refunded him. The clerk's office did not respond to questions about why this happened. No reports exist showing how often the Office of Congressional Ethics investigated financial-disclosure matters before the STOCK Act's passage. But one former attorney who worked in the office said nothing changed after lawmakers passed the law. "We were not looking into it. There was just nobody paying attention to it. No one was filing complaints," said Kedric Payne, who was the former deputy chief counsel at the Office of Congressional Ethics around the time that the STOCK Act was passed. Most of the investigations they dealt with between 2012 and 2014 involved campaign-finance issues, Payne said. "When you have the ethics committee, who has failed to go after these blatant violations — it sends a message that anything goes," Payne added. Not all STOCK Act violations appear nefarious. When Insider reached out to members about late filings, many said they forgot to file on time or didn't notice a filing was missing until they were reviewing financial documents. Others worked with a money manager who failed to notify them of trades in a timely fashion. Insider also spoke with numerous House staffers about their late filings. Many of them said they were the ones to initially reach out to the House Committee on Ethics to disclose that they'd violated the STOCK Act. Senate staffers, in contrast, receive notices from the Senate Select Committee on Ethics when they're late disclosing stock trades. But James Thurber, a professor at American University and congressional-ethics expert, said lawmakers should be more forthcoming. "They're waiting for a problem to blow up, and then they react to it, rather than being forthright and abiding by the rules," he said. "That is controversial and illegal." Reforms on the table Experts and lawmakers said the findings underscored the need to make the STOCK Act stronger and to possibly bar members from trading individual stocks altogether. Tyler Gellasch, a fellow at the Global Financial Markets Center at Duke University School of Law, said the law doesn't go far enough to create more accountability for lawmakers trading stocks. He's calling for Congress to pass a more extensive measure that would require lawmakers to use a third party, such as a blind trust, to participate in trading stocks. (Congressional lawmakers have this option, subject to approval by either the House or Senate ethics committees on a case-by-case basis.) Gellasch said the legislation should also require lawmakers and senior congressional staffers to instantaneously file disclosure forms once they make a stock purchase and to disclose the exact amount and day and time the transaction occurred. Today, lawmakers are only required to disclose the values of their trades in broad ranges, and they have up to 45 days to disclose their stock trades. "If you are a member of Congress, you have this duty to not take advantage of information you learned because of your job," said Gellasch, who previously served as congressional staffer to former Democratic Sen. Carl Levin, of Michigan, and helped draft the STOCK Act. Virginia Canter, the chief ethics counsel at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, said Congress' laissez-faire approach to the STOCK Act "sends the message that they are held to a lesser standard than other government employees, and that they are above the law." Canter called lawmakers' stock-trading habits "an accident waiting to happen." Their difficulties complying with the transparency and accountability provisions in the STOCK Act underscored why members shouldn't trade individual stocks, she added. Spanberger agreed: "We have regulations, we have rules, we have standards for a reason. And not enforcing them or abiding by them creates fertile ground for people to behave improperly."

ALSO SEE: Bodycam Videos Show Moments After Deputy Jeffrey Hash called 911 after he shot Jason Walker on Saturday, Jan. 8, in Fayetteville, North Carolina. The almost four-minute call records Hash as saying, “I just had a male jump on my vehicle and broke my windshield. I just shot him. I am a deputy sheriff.” “You said you shot him?” the dispatcher asked the deputy. “Yes, he jumped on my car, please,” he responded. When the dispatcher asked for his name, Hash said, “I am a lieutenant with the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office.” Later in the call, the dispatcher asks Hash if he is near the victim, he replies, “I am. He’s gone. He’s gone, ma’am.” “Is he breathing?” the dispatcher inquires. The deputy answered, “No, ma’am, he is not. He’s gone.” Hash then asks for “units out ’cause there’s people gathering.” During the call, the deputy tells the dispatcher that his vehicle is a red Ford F-150. He then states, “He shattered my windshield.” Also heard on the call is an exchange that Hash had with a witness, Elizabeth Ricks, the woman who tried to assist Walker after he was shot. The call captures Hash telling her to leave the scene. “Just keep moving, ma’am,” he says to Ricks. She replies to him, “I’m a trauma nurse.” To her qualifier, he says, “I’m a deputy sheriff. Come here. He jumped on my vehicle. I just had to shoot him.” The dispatcher joins in the conversation and asks for clarity on what actually happened, to which Hash submitted his version. “I was driving down the road and he came flying across Bingham Drive, running, and then I stopped so I wouldn’t hit him and he jumped on my car and started screaming; pulled my windshield wipers off, and started beating my windshield and broke my windshield,” Hash recalled. “I had my wife and my daughter in my vehicle.” The dispatcher asked, “Did he have any weapons, sir?” Hash said that Walker did not have a firearm, and again, asserted his version of the story, “He just tore my wipers off and started beating. … He busted my windshield.” Turning her attention to the victim, who Hash had already said was not breathing, the dispatcher about how many people are present at the site of the crime. “There’s tons of cars and people gathering around,” he stated. The 911 call continued to pick up conversations from those who gathered around Walker’s body. One key voice is Ricks, the trauma nurse Hash told to “keep moving.” Ricks can be heard saying that the man is still alive. Hash finally asks for help, saying, “He has a light pulse right now. I need EMS now.” The dispatcher asks where the man was shot, but neither Hash nor Ricks has the information. Hash reveals to the dispatcher, “I’m seeing blood on his side, ma’am.” Ricks is heard trying to save him, notwithstanding Hash’s request for EMS’s arrival on the scene. The call records her in the background asking for a shirt or something to stop the bleeding. Others in the background-repeat the dispatcher’s questions about where Walker was shot, but Hash continues to say that he doesn’t know and repeats his version of what happened, “He was on the front of my vehicle. He jumped on my car.” Ricks snaps, “I don’t care about that, where is the entry point?” Hash responded to her and says to the dispatcher, who tells him to stop talking to the people on the scene, “People are hostile right now.” Hash’s “hostile” comment was captured on the two-minute cellphone video of the aftermath of the shooting, recorded by Chase Sorrell, Ricks’ boyfriend. Ricks and Sorrell are key witnesses to the fatal shooting. The Fayetteville Observer reports that the two say they were driving about two car lengths behind Hash when the nurse saw Walker standing on the side of the road. Ricks maintains that Walker waited for one car to go by before he started to cross the street. That is when Hash’s truck came by and struck the 37-year-old Black man, and Hash got out the car and shot the man four times, the nurse says. After that, she got out of her car to attempt to save his life as he lay dying next to the back wheels of the Ford pickup truck. Ricks’ account of Walker being hit by a car contradicts police claims released earlier this week. Fayetteville Police Chief Gina Hawkins said on Sunday, Jan. 9, the pickup truck had a “black box” that would have registered if the vehicle struck “any person or thing.” She also added that one eyewitness said to her office that Walker was not hit by the truck. The Fayetteville newspaper reports that Ricks says she gave a witness statement to police at the scene of the shooting. Since the shooting, Hash has acquired representation. Parrish Daughtry, his lawyer, shared on Tuesday that her client was “devastated” about the incident. She said, “Lt. Hash is devastated for Mr. Walker’s family, his own family, the greater community and devastated by these events. Beyond that, I’m really prohibited from discussing the facts.” Walker’s family also acquired the services of a lawyer. Ben Crump, the civil rights attorney that has represented victims in many high-profile cases such as those of George Floyd and Trayvon Martin, will represent the interests of the family of the deceased.

His office released the following statement, “We have reason to believe that this was a case of ‘shoot first, ask later,’ a philosophy seen all too often within law enforcement. We look to the North Carolina SBI for a swift and transparent investigation so that we can get justice for Jason and his loved ones.” The North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation is solely handling the investigation around Walker’s death. The Fayetteville City Council voted unanimously during its first regular session meeting on Monday, Jan. 10, to invite the U.S. Department of Justice to assist in this case.

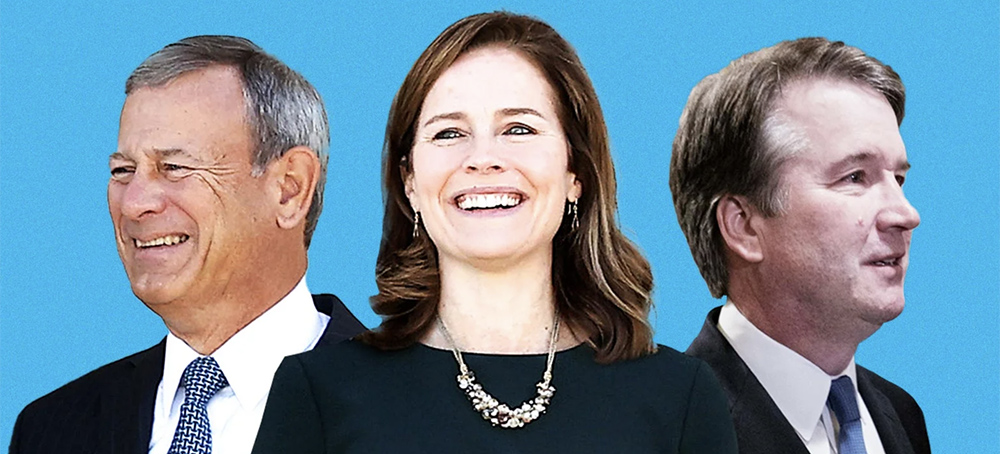

The Court is barely even pretending to be engaged in legal reasoning. The first, National Federation of Independent Business v. Department of Labor, blocks a Biden administration rule requiring most workers to either get vaccinated against Covid-19 or to routinely be tested for the disease. The second, Biden v. Missouri, backs a more modest policy requiring most health care workers to get the vaccine. There are some things that differentiate the two cases. Beyond the fact that the first rule is broader than the second, the broader rule also relies on a rarely used provision of federal law that is restricted to emergencies, while the latter rule relies on a more general statute. But the Court gives little attention to substantive differences between the laws authorizing both rules. Instead, it applies an entirely judicially created doctrine and other standards in inconsistent ways. The result is two opinions that are difficult to reconcile with each other. The NFIB case relies heavily on something known as the “major questions doctrine,” a judicially invented doctrine which the Court says places strict limits on a federal agency’s power to “exercise powers of vast economic and political significance.” As the NFIB opinion notes, the vaccinate-or-test rule at issue in NFIB applies to “84 million Americans” — quite understandably a matter of vast economic significance. But, if this manufactured doctrine is legitimate, then it’s not at all clear why it doesn’t apply with equal force in both cases. As Justice Clarence Thomas points out in a dissenting opinion in the Missouri case, the more modest health workers’ rule “has effectively mandated vaccination for 10 million healthcare workers.” That’s still an awful lot of Americans! What if the Biden administration had pushed out a rule requiring 20 million people to get vaccinated? Or 50 million? The Court does not tell us just how many millions of Americans must be impacted by a rule for it to count as a matter of “vast economic and political significance.” And it’s hard to draw a legally principled distinction between 10 million workers and 84 million. Similarly, in NFIB, the Court notes that the agency which created the broad rule at issue in that case is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) which, as its name suggests, deals with health threats that arise in the workplace, and Covid-19 is not unique to the workplace. “COVID–19 can and does spread at home, in schools, during sporting events, and everywhere else that people gather,” the majority opinion notes. But, as the three liberal justices point out in dissent, OSHA regulates threats that exist both inside and outside the workplace all the time, including “risks of fire, faulty electrical installations, and inadequate emergency exits.” It’s not at all clear why Covid-19 is any different. And the only explanation that the majority opinion gives — that a vaccination “cannot be undone at the end of the workday,” unlike the donning of fire-safety gear — applies with equal force to both the OSHA rule and the narrow health worker’s rule that the Court refused to block. Doctors’ vaccinations can’t be undone any more than an office worker’s can be. The Court, in other words, appears unable to articulate a principled reason why some vaccination rules should stand and others should fall. In the past, when the Court was unable to come up with principled ways to separate good rules from bad ones, it deferred to the federal agencies that promulgated those rules. The Court reasoned that it is better to have policy decisions made by expert agencies that are accountable to an elected president than to have purely discretionary decisions made by unelected judges with no relevant expertise. But the one thing that is apparent from NFIB and Missouri is that this age of deference is over. The opinions suggest that the Court will uphold rules that five of its members think are good ideas, and strike down rules that five of its members think are bad ideas. The Court is fabricating legal doctrines that appear in neither statute nor Constitution To understand the two vaccination cases, it’s helpful to start with the specific statutory language the Biden administration relied upon when it issued both rules. In the NFIB case, a federal law that generally requires OSHA to go through an arduous process to approve new workplace regulations also gives the agency the power to devise an “emergency temporary standard.” It can do so to protect workers from “grave danger from exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful” if such a standard is “necessary to protect employees from such danger.” Meanwhile, in the Missouri case, a different federal law instructs the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to issue rules that it “finds necessary in the interest of the health and safety of individuals who are furnished services” in institutions that accept Medicare or Medicaid funding (a category that includes most health providers and pretty much all hospitals and other major providers). There are striking similarities between these two statutes. Both use open-ended language, delegating powers that could be wielded in a wide variety of circumstances to protect against a wide variety of health threats. And both also state that the relevant federal agencies should only issue rules that are “necessary” to protect against such threats. And yet the Court analyzes these two very similar statutes in strikingly different ways. As mentioned above, NFIB relies heavily on the so-called major questions doctrine, a judicially created doctrine that is not mentioned in the Constitution or in any other federal law, and that sometimes limits federal agencies’ power to issue especially consequential regulations. “We expect Congress to speak clearly when authorizing an agency to exercise powers of vast economic and political significance,” the Court declares in NFIB, quoting from a decision last August that struck down a moratorium on evictions. Historically, this doctrine has been used primarily to help the Court interpret vague or ambiguous statutes delegating regulatory power to a federal agency. When it is unclear whether a particularly ambitious regulation falls within an agency’s statutory authority, the Court would sometimes err on the side of saying that the regulation is not permitted. But the issue in NFIB isn’t really that the statute is vague. As the three liberal justices note in a co-authored dissent, the six conservative justices in the majority do “not contest that COVID–19 is a ‘new hazard’ and ‘physically harmful agent’; that it poses a ‘grave danger’ to employees; or that a testing and masking or vaccination policy is ‘necessary’ to prevent those harms.” Rather, the majority appears to believe that, because OSHA is not engaged in an “everyday exercise of federal power,” the Court must look for reasons to strike its actions down. As mentioned above, the NFIB majority justifies doing so by claiming that OSHA’s authority is limited to the workplace, and the threat of Covid-19 “is untethered, in any causal sense, from the workplace.” Thus, unlike previous decisions that applied the major questions doctrine only when a statute is vague (that is, if it is unclear whether Congress intended to allow an agency to regulate), NFIB suggests that this doctrine applies to any open-ended statute that gives an agency broad powers. And it applies even if it’s apparent from that statute’s language that Congress intended to give the agency broad, open-ended authority. That’s a sweeping change. But say we take it at face value, and then look at the decision in Missouri. Under NFIB, the major questions doctrine only applies to matters of “vast economic and political significance.” But the Missouri opinion provides no explanation of why a rule that impacts 10 million workers does not qualify as a question of such significance. And if the major questions doctrine does apply, then the CMS rule appears to be just as vulnerable to this doctrine as the OSHA rule. If anything, the text of the CMS statute is even more open-ended than the language at issue in NFIB. OSHA’s statute for emergency regulations only permits it to address a “grave danger” and only when that danger arises from a “physically harmful” substance or agent that intrudes upon the workplace. CMS’s statute, by contrast, gives it far more sweeping authority to act in the “interest of the health and safety of individuals” who receive health care in facilities that take Medicare or Medicaid funding. And yet the major questions doctrine goes unmentioned in the Missouri opinion. Similarly, in NFIB, the Court swipes at OSHA’s broad rule because, it claims, “OSHA, in its half century of existence, has never before adopted a broad public health regulation of this kind.” But in Missouri, the majority opinion concedes that CMS’s “vaccine mandate goes further than what the Secretary has done in the past to implement infection control,” and it also notes that state governments, not CMS, have historically imposed vaccination requirements on health care workers. The two opinions cannot even agree on the significance of when the two rules were issued. In NFIB, the fact that there was “a 2-month delay” between when President Joe Biden announced that OSHA would issue a rule and when OSHA actually issued the rule is mentioned as a subtle dig against the administration. But in Missouri, the majority has no problem with a two-month delay. The Missouri opinion, in other words, appears to have been drafted by someone who was blissfully unaware of what the Court had to say in NFIB. The two opinions simply cannot be reconciled. They apply completely different legal rules and make no effort to explain why the analysis in one opinion does not apply in the other. At best, the Court is unable to keep track of what it is doing. At worst, it appears to have started with the result it wanted in both cases, and then worked backward to come up with some kind of reasoning to justify those outcomes. The Supreme Court wants to be President Biden’s boss In fairness, there is some language in the NFIB opinion that the Biden administration might find comforting. Although the Court rejects OSHA’s broad rule, it does indicate that OSHA could issue a narrower rule in some cases. “Where the virus poses a special danger because of the particular features of an employee’s job or workplace,” the Court writes, “targeted regulations are plainly permissible.” Similarly, NFIB rejects the slash-and-burn approach to curtailing OSHA’s authority that is favored by the very most conservative members of the federal bench. The majority opinion concedes that “Congress has indisputably given OSHA the power to regulate occupational dangers.” So, small victories: The opinions in NFIB and Missouri suggest that the Court will still permit the Biden administration to govern some of the time. But they also suggest that the Court will exercise a broad veto power over this administration’s regulatory actions. As Judge Jane Stranch wrote in a lower court opinion backing the OSHA mandate, the major questions doctrine that the Court relies upon to strike that mandate “is hardly a model of clarity, and its precise contours — specifically, what constitutes a question concerning deep economic and political significance — remain undefined.” The same can be said about other legal doctrines (such as one known as “nondelegation”) that the Court has also floated as justification to strike down federal regulations in recent cases. The elevation of these doctrines is dangerous. When courts hand down such vague and open-ended rules, they effectively transfer power to themselves. As the NFIB and Missouri cases show, doctrines like major questions are hard to apply in a principled way, and very easy to apply selectively. And they can justify striking down nearly any significant rule that a majority of the justices dislike. The justices, in other words, have set themselves up as the final censors of any regulatory action. The Biden administration may still propose new rules, but those rules are likely to stand only if five justices agree with them.

The oil spill was discovered December 27 east of New Orleans and came from a 16-inch diameter pipeline operated by Collins Pipeline Co. that had significantly corroded, officials said Wednesday. In fact, an October 2020 inspection revealed corrosion along 22 inches of pipe at the spill site, but repairs were delayed and fuel continued to flow through the pipe. “It’s especially maddening to learn that Collins Pipeline’s initial analysis deemed the pipe in such poor condition that it warranted an immediate repair,” Bill Caram of the Pipeline Safety Trust told the AP. The initial inspection more than a year ago revealed that the pipe had lost 75 percent of its metal near the worst parts of the corrosion. This would have required immediate repairs, but a second inspection concluded the damage was not bad enough to require repairs under federal law. This delay has had serious consequences for wildlife and the surrounding environment. The spill occurred near a levee along the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet Canal between Chalmette and Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge, Nola.com reported. Most of the diesel spilled into two ponds or “borrow pits,” the AP reported, while some contaminated soil in an environmentally vulnerable area. This led to the deaths of 2,300 fish, 39 snakes, 32 birds, some eels and a blue crab, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries said. In total, more than 200 animals besides fish were killed. Further, almost 130 other animals were impacted and captured to help them recover. This included 12 turtles, 20 snakes and 72 alligators, Nola.com reported. “We weren’t expecting to find so many alligators in that one area,” Wildlife and Fisheries’ oil spill response coordinator Laura Carver told Nola.com. “Thankfully they’re pretty sturdy animals.” Impacted birds were not so lucky. Of the nearly two-dozen birds captured for treatment, only two survived. Collins Pipeline Co. is owned by PBF Energy Inc., which is one the largest independent petroleum refineries in the U.S., according to The Hill. PBF Energy said that it was waiting on federal approval to repair the pipeline when the spill took place. The federal government finally ordered the pipeline shut down until repairs were completed on December 30. The cause of the spill was “likely localized corrosion and metal loss,” federal officials said, as The Hill reported. The company has since repaired the line, and operations started again last Saturday, the AP reported. “Although we continue to remediate and monitor the area, on-water recovery operations have been completed,” PBF Vice President Michael Karlovich told the AP in an email. Overall, Collins Pipeline Co. has faced six enforcement cases from the federal government since 2007. The full extent of the damage caused by the oil spill is not yet known, according to The Hill.

Follow us on facebook and twitter! PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611 |

No comments:

Post a Comment