Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Performing arts companies all over are striving to be politically proper these days, and practice inclusivity and diversity, and here’s a comedy with servants in it and romantic shenanigans and all is resolved in the end with a sweet chorus along the lines of “Let’s forgive each other and all be happy,” especially sweet since in 1786 when Mozart wrote it diseases were raging for which there were no vaccines and people languished in debtors’ prisons and small children worked in factories and people felt lucky to live to be 40. Mozart died at 35 from an infection treated today by antibiotics. And the piece is gorgeous and funny as can be. I sat next to my wife who once played violin on an opera tour of forty consecutive Figaros and she laughed through it all.

The Count is arranging a tryst with Susanna and the Countess sings the gorgeous lament of the betrayed wife, “Dove sono i bei momenti” (Where have those beautiful moments gone of sweetness and pleasure and why, despite his lying tongue, do the happy memories not fade?), a moment of sheer transcendent heartbreaking beauty and then you’re back to the slapstick, the baritone’s lust for the soprano, people hiding behind curtains, the seductive note, the wife plotting revenge.

With COVID going on, the Met is working like crazy to stay in business. A singer tests positive and a sub has to be ready in the wings and new rehearsals scheduled to work him or her into the complexity of the staging, and this happens over and over, and the sub cannot be Peggy Sue from Waterloo, the sub must be a pro and a principal who is up to par, and so singers have been brought in to cover the crucial roles, and a soprano might cover the Countess in Figaro and Musetta in La Bohème, two major roles and she must be prepared — in the event the lead tests positive for COVID — to go onstage tonight in one opera or tomorrow night in the other, two demanding roles in her head and a sheaf of stage directions, and maybe she’s living out of a suitcase in lockdown, and staying away from unmasked strangers, meanwhile the Met is playing to half-empty houses due to fears of the virus, and this is not a small matter. The Metropolitan Opera is the standard-bearer of the art form in America. If it goes under, something fabulous and thrilling is lost in our country. There is a battle going on; it’s a story you could write an opera about.

If you consider opera elitist, then I guess passionate feeling is elitist and we should all be content to be cool and lead a life of Whatever. Pop music is cool, but opera is out to break your heart. I saw William Bolcom’s A View From The Bridge a couple years ago and I’m still a mess. Renée Fleming did the same to me in Der Rosenkavalier.

I am no student of opera, only a tourist, and I’m from the Midwest, the home of emotional withdrawal, where I grew up among serious Bible scholars for whom the result of scholarship was schism and bitterness, and now I go to a church where I am often overwhelmed by the hymns, the prayers for healing, the exchange of peace, a church full of Piskers but sometimes the sanctuary is so joyful and we stand for the benediction and, as Mozart wrote, let us forgive each other and go and be happy, and let us also, for God’s sake, get vaccinated. Do it for the sake of the soprano’s children so she can come out and break your heart.

A view of the Social Security Administration building in New York on Oct. 20, 2020. (photo: John Nacion/NurPhoto/AP)

A view of the Social Security Administration building in New York on Oct. 20, 2020. (photo: John Nacion/NurPhoto/AP)

Social Security is inflation-adjusted, so benefits are going up 5.9 percent to keep the purchasing power of retirees the same.

There have been a vanishingly small number of pieces, however, about a basic fact connected to inflation — one that will help shield tens of millions of Americans from it and that should be seen as a historic victory for Democrats: Social Security benefits are adjusted upward in step with inflation at the beginning of each year, so even as prices rise, recipients lose little purchasing power.

You might assume that Democrats would constantly publicize how their party created Social Security and help voters understand how it works and why it’s an extraordinarily good deal for them, especially in periods like these. Instead, as recently as the Obama administration, they seemed embarrassed that they ever came up with it in the first place. President Barack Obama’s main focus regarding Social Security appeared to be finding politically palatable ways to cut benefits (although he did change course at the end of his presidency). And while Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden both formally ran on expanding Social Security, they never pushed it with the kind of fervor and clarity needed to make their policies clear to regular people. While in office, Biden has done little even as congressional Democrats are attempting to generate momentum for significant improvements to the program.

But if top Democrats won’t educate us about why Social Security is a huge boon for Americans, and therefore why we have to defend and improve it, we should educate ourselves.

The most important thing to understand about Social Security for retired workers is that it is an inflation-adjusted lifetime annuity.

The inflation-adjusted part means that Social Security benefits go up automatically each year by the same rate as inflation. For 2022, Social Security’s 66 million recipients will see a 5.9 percent cost-of-living adjustment, or COLA, starting this month. The average monthly Social Security payment for retired workers was $1,565 in 2021; thanks to the 5.9 percent COLA, it is now $1,657.

This means that retirees are protected from inflation to the degree that their income comes from Social Security. This generally means that the poorer a beneficiary is, the more inflation protection they’ll get. Thirty-seven percent of older male recipients and 42 percent of older female recipients get at least half of their income from Social Security; 12 percent of men and 15 percent of women count on Social Security for 90 percent of their income or more.

(In addition, while payments to older people are the best-known and largest aspect of Social Security, it is officially the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program. Other recipients receiving the 5.9 percent bump include people with disabilities that prevent them from working, as well as the children and surviving spouses of workers who’ve died. For instance, Paul Ryan, Sen. Mitt Romney’s running mate in the 2012 presidential election and a former Speaker of the House, received survivors payments for several years after his father died when Ryan was 16. He was so grateful that he spent his career obsessively trying to slash Social Security.)

The lifetime annuity part means that once you start collecting Social Security’s retirement benefits, you will continue to receive the same amount (adjusted for inflation) every month until your death. Almost everyone as they grow older becomes concerned about outliving their money. But Social Security provides a guarantee that at least some of it will last as long as you do.

Once you understand these aspects of Social Security, you’ll see why it works so incredibly well for so many people. If Social Security were eliminated, it would be prohibitively expensive or impossible for older people to get anything similar from an insurance company. As Nancy Altman, president of the advocacy organization Social Security Works, says, all in all Social Security combines features “that you can’t get in the private sector.” Here’s why:

• Annuities bought from insurance companies generally don’t offer any kind of inflation adjustment. As time goes on, their purchasing power erodes, and the longer you live, the worse it gets. It is possible to pay more — much more — for annuities that will go up to some degree with inflation, perhaps up to 2 percent or 4 percent or sometimes higher. But Altman points out that Social Security’s COLAs were 9.9 percent in 1979, 14.3 percent in 1980, and 11.2 percent in 1981. No insurance company would offer that kind of inflation protection and would go bankrupt if it tried.

• Social Security is designed so that the less a retiree made during their work life, the larger the percentage of their wages are replaced by the program. This is the formula as of this year:

(a) 90 percent of the first $1,024 of their average indexed monthly earnings, plus

(b) 32 percent of their average indexed monthly earnings over $1,024 and through $6,172, plus

(c) 15 percent of their average indexed monthly earnings over $6,172.

This means that the cost of buying an annuity on the private market would be proportionately much higher for lower-earning workers than for higher-earning ones.

• Social Security does not engage in any kind of underwriting: i.e., evaluating beneficiaries and charging them differently based on risk. But private insurance companies absolutely do. In particular, private market annuities are more expensive for women than for men the same age because women live longer on average.

• Women also benefit from the fact that Social Security pays 100 percent survivor benefits to spouses even if the marriage ended in divorce, as long as it lasted at least 10 years. This means that when a former spouse dies — which is statistically more likely to be the man in a heterosexual marriage — and the former spouse made more money during his career — also statistically likely — the former wife will receive the same level of benefits he did. This is difficult or impossible to find in the private market.

• Perhaps most importantly, the government can’t go out of business. Private corporations absolutely can. For instance, American International Group, often shortened to AIG, is one of America’s largest sellers of annuities. During the 2008 financial crisis, it would have collapsed entirely if it hadn’t received a gigantic government bailout.

Lastly, if you’ve made it all the way to the end of this and are worried about Social Security’s potential financial shortfall in the 2030s, don’t be. You may have noticed that the people telling you about Social Security’s impending doom are exactly the same figures who told us to be terrified about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction 20 years ago. The danger in both cases is exactly as real and frightening: i.e., effectively nonexistent. There are entire books that delve into detail about how the propaganda campaign against Social Security has functioned and why you don’t need to be concerned about its future. But the simple explanation is that Social Security’s financing has been adjusted many times before and inevitably will be again, and the U.S. generates more than enough wealth for retirees to get their full, promised benefits even as working-age adults grow richer.

What’s happening with Social Security today is therefore a government insurance program doing exactly what you would want it to do. Life is full of risks that are largely outside any one person’s control, from unemployment to illness to living an unexpectedly long life. The point of a program like Social Security is to spread the costs of these risks across all of society rather than pile it on the shoulders of individuals who got a bad roll of the dice. Let’s make sure we notice this — a true victory for people working together to make the world better for everyone — rather than take it for granted.

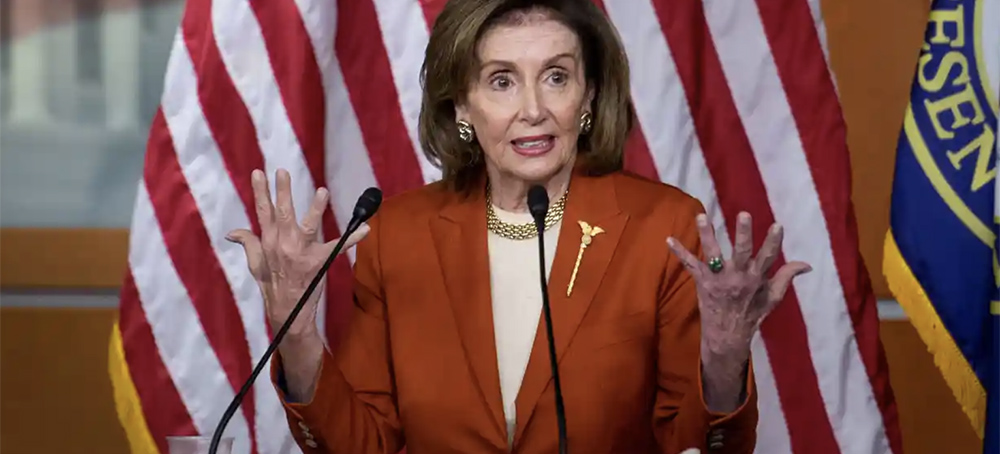

Some young TikTokers have started to watch Nancy Pelosi's financial disclosures for stock tips. (photo: Shutterstock)

Some young TikTokers have started to watch Nancy Pelosi's financial disclosures for stock tips. (photo: Shutterstock)

Feminism isn’t about championing women like Nancy Pelosi just because they’re in high-powered positions: it’s about fighting for a more equal society

Here’s a thorny philosophical quandary for you: if you’re a politician who shapes policy and is privy to confidential information that will impact the stock market, should you and your immediate family be able to trade individual stocks?

For most people the answer to this is “hell no”. Allowing lawmakers to buy and sell individual stocks raises glaringly obvious conflict of interest issues: America may be divided on a lot of things but the country is incredibly unified on this. A recent poll found that found that 76% of voters believe that members of Congress and their spouses have an “unfair advantage” in the stock market – just 5% of respondents approved of members trading stocks.

Were those 5% of respondents related to politicians, I wonder? Because the people on Capitol Hill sure seem to love playing the market. In the early days of the pandemic there were multiple scandals about well-timed stock trades by Republican and Democratic lawmakers. In one of the most egregious examples, Senator Richard Burr and his brother-in-law dumped $1.6m in stocks in February 2020 a week before the market crashed; Burr’s brother-in-law reportedly sold his holdings one minute after getting off the phone with the senator. There were the usual internal investigations into all these trades but nobody faced any meaningful consequences. Eventually the issue faded from the headlines.

Now, however, political stocks are back in the spotlight. On Wednesday two Democratic senators (Jon Ossoff from Georgia and Mark Kelly from Arizona) introduced the Ban Congressional Stock Trading Act, which would prevent congressional lawmakers and their immediate families from picking stocks. Spotting that this would clearly go down well with the public, Republicans immediately got in on the act. Josh Hawley announced a competing proposal to limit stock trading just hours after. On Friday it was reported that Ted Cruz might introduce his own legislation. “Hawley and Cruz want to one-up each other,” a source told On The Money. “They don’t want to let the other one own the issue … they’d never join the other senator’s bill because it would mean they couldn’t be the star.”

Hawley and Cruz aren’t exactly known for championing progressive issues: why are they so keen on being the face of this? Most likely, I reckon, because they don’t think the legislation will really go anywhere but championing it will make them look good. And also, of course, because it gives them a perfect opportunity to bash house speaker Nancy Pelosi who, along with her husband Paul Pelosi, are extremely active, and very successful in the market. Some young TikTokers have even started to watch her financial disclosures for stock tips. Pelosi, known as the Queen of Stonks, has become something of a meme.

Funnily enough, Pelosi (who is one of the richest people in Congress) isn’t keen on the idea of having her stock market activities limited. “We are a free-market economy. They should be able to participate in that,” Pelosi told Insider when questioned on the issue last year. She conveniently ignored the fact that there are plenty of ways that politicians can participate in the stock market without it raising such ludicrous conflict of interest issues. They can passively invest in mutual funds or put their assets in a blind trust. Let’s be very clear here: for most people, actively trading individual stocks versus passively investing in index funds is a great way to lose money. There are endless studies on this. If you’ve got a track record of picking great stocks then you’re either very lucky or you might just have information other people can’t access.

Last week, in an interview with the Guardian, Bernie Sanders lamented the fact that the Democrats have turned their back on the working class, leading Republicans to win more and more support from working people. Pelosi’s attitude toward stock trading is a perfect example of this phenomenon. Ossoff and Kelly’s bill to ban congressional stock trading is very good – and very overdue. But here’s what I’m afraid is going to happen now: Republicans will hijack the issue and endlessly message about Pelosi’s multimillion-dollar stock trades. They’ll cast her, and the Democrats, as out-of-touch elitists. Which of course, many of them are. The Democrats will lose even more support from working people – which they’ll most likely blame on progressives.

The Week in Patriarchy is a newsletter about feminism: some readers might be wondering why I’m writing about stocks this week. Here’s the thing though: gender inequality is inextricably bound up with economic inequality. Feminism isn’t about championing women like Pelosi just because they’re women in high-powered positions: it’s about fighting for a more equal society. It’s a shame that the Democrats don’t seem to realise that.

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

An old rock band can get away with playing the same hits over and over, but provocative clowns like Trump need fresh material to stay relevant.

Trump’s performance in Arizona on Saturday night—his first rally in months and his much-hyped chance to respond to the one-year anniversary of the Jan. 6 Capitol riot—was neither shocking nor terribly newsworthy.

It didn’t even merit a mention on The Washington Post’s homepage Sunday morning. The New York Times only used Trump’s speech as a peg to write a broader story under the headline: “Trump Rally Underscores G.O.P. Tension Over How to Win in 2022.”

A few years ago, Trump rallies spawned breathless coverage and drove multiple news cycles. But The Times’ story isn’t even about the rally, and their mentioning it is mostly perfunctory.

To keep readers’ attention, The Times spotlighted a cast of supporting characters, such as Kari Lake, a Trump-endorsed candidate for Arizona governor who used to be a local news anchor. The photo of her in The Times shows her wearing some sort of cape, which I think we can all find mysterious. No wonder they used her.

TV sitcom showrunners sometimes react to declining ratings by introducing a “Cousin Oliver”—which, quite often, is a cute kid whose smart-alecky sass is meant to liven up a tired atmosphere. Sometimes it works, sometimes it’s evidence a show has simply “jumped the shark.” But Trump’s never been an ensemble cast type of personality. He’s the whole show, and the surrounding players are as replaceable and ephemeral as Spinal Tap’s exploding drummers.

The Arizona rally may have been the unofficial kickoff of his 2024 campaign. But this time around, Trump will have to work harder to break through—and not just because the media is less likely to give him ample air time free of charge.

Call it the Andrew Dice Clay conundrum: If your entire schtick is based on shock value, eventually the audience grows inured, and the lack of substance becomes embarrassingly plain.

Trump made assertions in Arizona Saturday night that might once have garnered buzz (on Sunday morning, at least). But they’re getting little play. In its writeup of the rally, Politico said Trump “issued a blistering response to Democrats” and that he “opened his speech by falsely claiming ‘proof’ that the 2020 election was ‘rigged.’” A more telling fact is that this “blistering response” was not deemed worthy enough to be the site’s lead story. What might have spawned outrage and wagging tongues a few years prior now elicits a collective chorus of yawns.

Here’s the thing about moving the Overton Window: The process of shifting standards and assumptions matters greatly at the societal level. It’s bad when news consumers become desensitized to a former president erroneously claiming an election was stolen. It also cannibalizes one of Trump’s greatest assets: his ability to shock and awe. His schtick is tired, and that can often equate to a professional death sentence.

Trump’s rock-concert rallies provide enough of his greatest hits for the fans and groupies who actually attend them. But for performers to remain relevant, they require new material. And politics is more stand-up comedy than rock and roll.

The Rolling Stones can play their more-current hits a million times, yet we will still keep clamoring for “Sympathy For The Devil.” But can you imagine Chris Rock getting an HBO special and doing 2016 material? The same goes for Trump. Nobody wants to hear a political retread who rehashes his same tired conspiracy theories ad nauseam.

Trump seems like the sort of man who could appreciate the temporal, consumerist, and disposable culture of modernity. We fetishize what is new and what is next. Yet, Trump’s obsession with relitigating an election that is now two calendar years past runs contrary to this modern American tendency. In this regard, his ego trumps his marketing savvy.

To be sure, Trump also benefits from the (bogus) sense he was wronged. But it’s hard to see how such a backward-looking 75-year-old man can remain in the vanguard. On Saturday night, Trump wasn’t just stuck in 2020—he was also stuck in the 20th century. There were numerous references to communism (more so than usual), including a reference to the Jan. 6 Commission’s witness interviews, which he compared to Stalinist show trials.

You might forgive Trump for such fanciful attacks on Nancy Pelosi and Congressional Democrats, since his criticism of Joe Biden isn’t terribly effective. Trump isn’t skilled at prosecuting a substantive policy critique, and, despite Biden’s low approval ratings, it’s really hard to get too worked up about him (the best Trump could do was mock him for seeming dazed and confused). All this is to say, the new material didn’t kill on Saturday night.

The theme was “Make America Great Again…Again.” Even Trump’s apparel hinted at the likely sequel. He donned a red “Make America Great Again” hat that partially obscured his eyes most of the night, but it wasn’t the iconic version from the 2016 election. He was attempting to have it both ways by playing his “greatest hits” and floating some new material. But does lightning ever really strike twice? For every “Godfather II” masterpiece there’s dozens of “Ghostbusters II” failed sequels.

We’d be fools to count Trump out entirely. If anyone in American lore is capable of a third act—it’s him. But he needs new material, and fast, because if his Arizona rally shows anything, it’s that the old routine just doesn’t land anymore.

As demand for testing ramps up, community clinics and nonprofits struggle to keep up with the need. These groups have run testing sites throughout the pandemic in low-income and minority neighborhoods, like this one in the Mission District of San Francisco, Calif., from UCSF and the Latino Task Force. (photo: David Odisho/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

As demand for testing ramps up, community clinics and nonprofits struggle to keep up with the need. These groups have run testing sites throughout the pandemic in low-income and minority neighborhoods, like this one in the Mission District of San Francisco, Calif., from UCSF and the Latino Task Force. (photo: David Odisho/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Her symptoms were mild, but she wanted to get tested for COVID before she went back to work, so as not to spread the virus. She works for herself, and wants to keep her clients' trust.

"First I need to know that I've taken all the precautions. I need to be sure it's only a flu," she says.

Felix had spent all morning driving around to pharmacies in Richmond and surrounding cities, looking for rapid antigen tests. There were none to be found.

The COVID testing site at her neighborhood clinic, Lifelong Medical Center, was fully booked. She called and called but waited so long on hold that she got discouraged and hung up.

For Felix, a week with no work means losing up to $800 dollars in income.

"That's a lot because I need it to pay the bills," she says with a nervous laugh. "I feel desperate because I have to cancel all my work this week. If they give me an appointment it'll be tomorrow or the next day, so I have to cancel everything."

Across the country, the spread of omicron has people scrambling to get tested for COVID. The lines are long, appointments get scooped up fast, and rapid antigen tests are hard to find. This problem is hitting essential workers – often people of color – particularly hard. Unlike many office workers, they can't work from home, and their companies haven't stockpiled tests. The result is lost wages or risking infecting coworkers or family members.

Renna Khuner-Haber, who coordinates Lifelong Medical's testing sites, says the people who most need convenient home tests can't get them. The disparity is glaring, especially in the Bay Area, where tech companies send boxes of rapid antigen tests to workers who have the option to work from home in a surge.

"Rapid tests — they're not cheap. If you have a family of 10 people and everyone needs a rapid test and they're each $10, that's $100 right there. To test everyone twice, that adds up," she says.

Community testing sites try to fill the gaps

One solution that's filling in the gaps are small neighborhood clinics like Lifelong Medical, which specifically serve low-income communities, including Medicaid patients, Spanish-speaking immigrants, and essential workers who risk COVID exposure at their jobs.

Since the beginning of the year, the demand for testing at this neighborhood clinic in the working class city of Richmond has ballooned.

Lifelong runs three testing sites in the Bay Area. Its COVID hotline is getting about a thousand COVID calls daily, up from about 250 in the fall.

José Castro is one of their patients. His whole family had the sniffles, so he brought his wife and three children, ages 3, 5, and 14, to get tested. He works as a house painter and spent the previous day driving all the way to San Francisco the previous day trying to find a test.

"I waited about an hour or 90 minutes on the phone [with Lifelong] and finally got through to get an appointment. I need to have a negative test to be confident that I'm not positive so I don't transmit it to anyone at the job site," he says, in Spanish. "Also my oldest son needs a test to go back to school."

Another Lifelong patient, Victoria Martín works as a dental hygienist and worried about being exposed after someone tested positive at work. She was frustrated to have caught a cold – hopefully not COVID – even after she cancelled holiday plans.

"It's very scary. I came here yesterday and made an appointment for today," she says. "You try to stay safe by staying in a close circle and not going out, and then someone in your bubble gets it and what can you do?"

Reaching vulnerable communities and struggling to scale up

Lifelong's Richmond site can only test 60 people daily and can't scale up. Compare that to a county site a 15-minute drive away in Berkeley run by a private lab, which can do up to a thousand tests per day.

During the surge, these smaller clinics have been swamped, struggling to keep up with demand. Yet public health officials say the small scale is by design, a feature not a flaw.

"It's not always about quantity. But if we're reaching those who have no other way to access testing resources, then we're achieving our goal," says Dr. Jocelyn Freeman Garrick, who leads COVID testing for Alameda County's public health department.

With demand up 400% at county testing locations, Freeman Garrick says these smaller sites do what larger ones can't – serve vulnerable neighborhoods.

"We found at those smaller sites, their percent positivity rate was much higher than the general population so the number [of tests] may be small, but that's a pivotal role," in serving people whose jobs and living situations put them at risk, Freeman Garrick says.

Another group in San Francisco's Mission District, called Unidos en Salud, also provides COVID testing and vaccinations to undocumented people, essential workers, recent immigrants, and the uninsured, through a partnership with UC-San Francisco and the Latino Task Force.

"These sites are for communities who don't have health care and where people might not trust other sites," says Dr. Carina Marquez, who founded the partnership. Still, she adds: "Size does matter when you're in a surge."

At Unidos' Mission testing site, daily tests rose from about 200 in early December to about 980 in early January as omicron hit and people spilled over from private and county-run sites in better-resourced parts of the city.

Her organization has decided not to require appointments, even though it's a challenge to manage the line that stretches around the block.

At Lifelong, after a lull in demand since late summer, it's been hard to meet the community's testing needs.

"We're in a moment in the surge where demand is through the roof. We don't have staffing and we were never built to do that," Khuner-Haber says. "It's so hard to prioritize. Everyone is coming because they were exposed, symptomatic, or needing to return to work or school. Everybody is top priority."

With some of her employees calling in sick, Khuner-Haber has struggled to stay fully staffed and hire culturally competent, Spanish-speaking staff, who are essential to building trust with patients.

Strapped for resources

Andie Martinez Patterson, a vice president with the California Primary Care Association, says mission-minded health clinics need more resources sothey can hire more staff.

"The point for health centers is that we are open door access for anybody and in particular for vulnerable and underserved disenfranchised populations," she says. "It is the moral imperative in the mission of why community health centers exist."

Martinez Patterson says neighborhood clinics have stepped into testing and vaccination as part of their role as primary care providers.

But because these clinics primarily serve Medicaid recipients, they're not reimbursed at the same rates as other testing centers, many of which negotiated large contracts with county health departments.

"We are not reimbursed anywhere close to what we're reimbursed for in the typical primary care setting. So you, in effect, take staff, you lose money immediately to achieve the moral imperative," she says. If Medi-Cal, California's Medicaid program, reimbursed more, clinics could hire more staff and serve more people.

The state provides tests and vaccines to these sites, but she argues that the current payment structure in a fee-for-service environment means clinics lose money when providing life saving vaccines and COVID tests.

COVID is a chance to restart the policy conversation about how health centers get paid, so they can be part of public health disaster response in the future, Martinez Patterson says.

Easy testing access and follow-up care are critical

There's a big need for easy access to testing in the neighborhoods served by community clinics because the mostly low-income Latino immigrant families who live there are more likely to live in multi-generational households, where one sick family member could expose more vulnerable ones.

That was Alejandra Felix's situation. There are seven people living in her home, including her daughter, and a grandson who's too young to get vaccinated.

"There's a baby in my house. That's why I'm worried. I wear gloves and a mask in my own home, because I want to protect the baby," she says. When she got sick, she stopped cooking for her family and sent her husband to sleep on the living room couch.

"Easy walk-up access to testing is critical. You want a situation where you can bring the whole family down and get tested," says Marquez from Unidos en Salud. "Testing should be low-barrier, easy to access, with no online registration, where people can wait in line, and get results quickly. Then they need to get linked to care."

Unidos also provides follow-up care to people who test positive, offering financial assistance, food, cleaning supplies, and more medical care when appropriate.

"Sometimes people need guidance on how to isolate in crowded households, when they can go back to work and what to do on day five. Vulnerable workers and families want to prevent transmission, but a positive test has so many implications for them," says Marquez.

To improve testing access, Marquez sees potential in the promotora model, where community members are trained to conduct rapid antigen tests and counsel people, then can be called in to help deal with surges. Primary care providers, schools and clinics can also be proactive in distributing at-home tests to their patients.

Meanwhile, staff at small community clinics are just trying to keep up with the surge. At Lifelong Medical, Griselda Ramirez-Escamilla, who runs the clinic's urgent care center, says this surge is taking an emotional toll on her small staff.

"We get tired and we just got to step aside, take a breath. There are times where we cry a little," she said, tearing up from exhaustion. "It's hard! And we show up every morning. We have times where we do break down, but it's just the nature of it. We have to lift our spirits and keep moving."

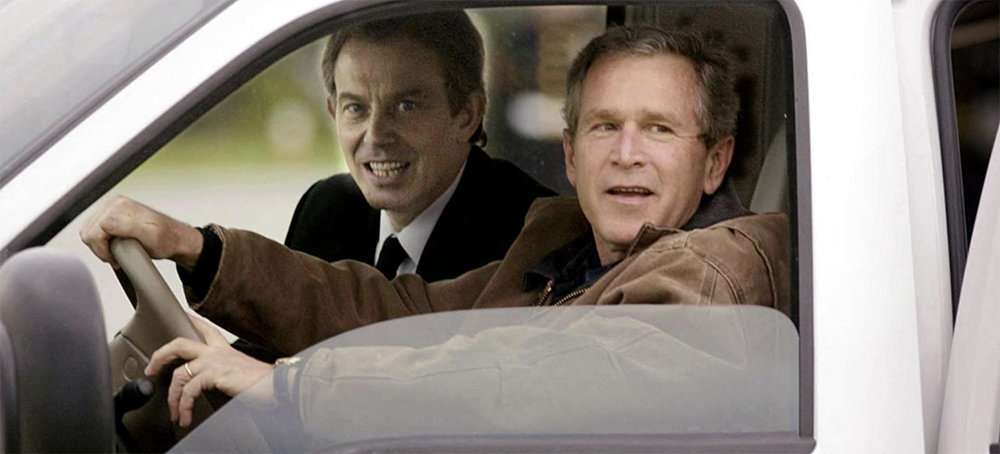

Bush (R) drives with Tony Blair (L) in his truck after Blair arrived at Bush's Crawford ranch on 5 April 2002. (photo: AFP)

Bush (R) drives with Tony Blair (L) in his truck after Blair arrived at Bush's Crawford ranch on 5 April 2002. (photo: AFP)

US president told British PM he 'didn't care' who replaced Saddam Hussein as pair plotted PR campaign to sell war a year before invasion

The former US president was blithe about the consequences of launching an invasion at a crucial meeting with the British prime minister at his Texas ranch in 2002, almost a year before the war was launched.

“He didn’t know who would take Saddam’s place if and when we toppled him. But he didn’t much care. He was working on the assumption that anyone would be an improvement,” the British memo, written by Blair's top foreign policy adviser at the time, reads.

Bush believed - but the memo says he would not say publicly - that a “moderate secular regime” in post-Saddam Iraq would have a favourable impact both on Saudi Arabia - a close US ally - and Iran.

He had said it was essential to ensure that acting against Saddam would enhance rather than diminish regional stability. Bush "had therefore reassured the Turks that there was no question of the break-up of Iraq and the emergence of a Kurdish state".

The memo also reveals how as early as April 2002, more than eight months before United Nations weapons inspectors went into Iraq, Blair was aware that they might have to “adjust their approach” should Saddam give them free rein.

This is believed to be the first reference to a strategy which ended with the creation of the infamous “dodgy dossier” of concocted intelligence making the case for war, key details of which were later admitted to be false.

The memo hardens the central findings of the public inquiry into the war led by John Chilcot which concluded in 2016 that the UK chose to join the invasion before peaceful options had been explored, that Blair deliberately exaggerated the threat posed by Saddam, and that Bush ignored advice on post-war planning.

It was written by David Manning, Blair’s top foreign policy adviser, one day after the meeting at the president’s ranch in Crawford, Texas, on Saturday 6 April 2002.

Apart from Bush and Blair, only a handful of officials were present from both sides, and much of the discussion between the two leaders was conducted one-on-one.

The president and prime minister had developed a particularly close relationship in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 al-Qaeda attacks in the US, following which Blair had pledged to "stand shoulder to shoulder with our American friends". The two trusted and confided in each other more than they did some of their own colleagues.

The UK had been a key supporter and participant in the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001. Iraq, which had long been subject to UN sanctions imposed over Saddam Hussein's weapons programmes, had also been in US sights since the launch of the so-called "war on terror".

In another memo sent to Blair weeks before the Crawford meeting, Manning reported that Condoleezza Rice, Bush's national security adviser, had told him over dinner that Bush really needed Blair's support and advice, angered as he was at the reaction he was getting in Europe.

'Exceptionally sensitive'

At the time, the plan to launch a war was a closely guarded secret even within senior US military circles. Manning notes that only a “very small cell” in US Central Command (Centcom) was involved in drawing up plans, with most high-ranking military officials kept in the dark.

He wrote: “This letter is exceptionally sensitive and the PM instructed it should be very tightly held, it should be shown only to those with a real need to know and no further copies should be made.”

The memo was addressed to Simon McDonald, foreign secretary Jack Straw’s principal private secretary, and circulated to a handful of other senior British officials.

They were Jonathan Powell, Blair’s chief of staff; Michael Boyce, the chief of defence staff; Peter Watkins, the principal private secretary to defence minister Geoff Hoon; Christopher Meyer, the British ambassador in Washington; and Michael Jay, the permanent secretary at the foreign office.

Rice told the Crawford ranch meeting that “99 percent” of Centcom was unaware of the Iraq war plans.

Manning recounts how Bush and Blair war gamed the issue of sending weapons inspectors into Iraq.

Both leaders were concerned about the level of European opposition to military action and the memo notes that Bush accepted that “we need to manage the PR aspect of all this with great care”.

Manning wrote: “The PM said we needed an accompanying PR strategy that highlighted the risks of Saddam’s WMD programme and his appalling human rights record. Bush strongly agreed.”

“The PM would emphasise to European partners that Saddam was being given an opportunity to co-operate. If, as he expected, Saddam failed to do so, the Europeans would find it very much harder to resist the logic that we must take action to deal with an evil regime that threatens us with its WMD programme.”

Blair was concerned then by the possibility that Saddam would let UN inspectors in and allow them to go about their business - which in fact subsequently happened.

Inspectors returned to the country in November 2002 and remained there until 18 March 2003, one day before the launch of the US-led attack on Iraq.

In February 2003, Hans Blix, the UN's chief inspector, told the Security Council that Iraq appeared to be cooperating with inspections, and said that no weapons of mass destruction had been found.

Blair told Manning after a private conversation with the US president: “Bush had acknowledged that there was just a possibility that Saddam would allow them in and go about their own business. If that happened we would have to adjust our approach accordingly.”

Furore over knighthood

The Manning memo was first leaked to the Daily Mail, amid the public furore over the award of a knighthood to Blair. Middle East Eye has been passed a copy of the text of the memo, which it is publishing in full.

A petition to have Blair’s knighthood rescinded has since gathered more than one million signatures.

The memo is the second written by Manning on Iraq to see the light of day. In 2004, the Daily Telegraph newspaper published details of a memo by the British diplomat to Blair concerning preparations for the Crawford summit.

Dated 13 March 2002, Manning tells Blair of his dinner with Rice and their conclusion that failure “was not an option”.

Manning writes: “It is clear that Bush is grateful for your support and has registered that you are getting flak. I said that you would not budge in your support for regime change but you had to manage a press, a parliament and a public opinion that was very different than anything in the States. And you would not budge either in your insistence that, if we pursued regime change, it must be very carefully done and produce the right result. Failure was not an option.”

Manning told Blair that the issue of weapons inspections “must be handled in a way that would persuade European and wider opinion that the US was conscious of the... insistence of many countries for a legal basis.”

On the visit itself, Blair was told that Bush would want to pick his brains. “He also wants your support. He is still smarting from the comments by other European leaders on his Iraq policy.”

Blair received a number of warnings from top advisers just before the summit. Peter Ricketts, the British government’s national security adviser, wrote to Blair that scrambling to establish a link between Iraq and al-Qaeda was “so far frankly unconvincing”.

Even if they successfully made the case that the threat posed by Iraq ought to be taken seriously because of the country’s use of chemical weapons in its 1980s war against Iran, “we are still left with a problem of bringing public opinion to accept the imminence of a threat from Iraq. This is something the prime minister and president need to have a frank discussion about”.

Straw, then foreign secretary, wrote to Blair on 25 March 2002 that the rewards of Crawford would be few and the risks high.

He warned of "two legal elephant traps". Straw wrote that regime change in Iraq per se was no justification for military action, noting “it could form part of the method of any strategy, but not a goal”.

The second was whether any military action would require a fresh mandate from the UN Security Council.

“The US are likely to oppose any idea of a fresh mandate. On the other side, the weight of legal advice here is that a fresh mandate may well be required," Straw wrote.

"Whilst that is very unlikely, given the US's position, a draft resolution against military action with 13 in favour (or handsitting) and two vetoes against could play very badly here.”

'Closest to the horse's mouth'

The Manning memo did surface during the Iraq inquiry, but was never published and only obliquely referred to by Roderic Lyne, a member of the inquiry panel, when Manning gave evidence in 2010.

Addressing Manning, Lyne said: "You were obviously the closest person to the horse’s mouth on this one.”

Lyne went on to ask Manning whether Crawford was a decision point for Blair. Manning replied that he thought at Crawford that US thinking had "gone up a gear".

Bush had created a team and asked them to give him options and a British official was later invited to Centcom's headquarters in Tampa, Florida, to see what those options were, he said.

When contacted for comment, a spokesperson for Manning told MEE: "Sir David would like to reiterate that in all correspondence relating to this period he has nothing to add to the evidence he gave to the Chilcot Inquiry.”

MEE has also approached Bush and Blair for comment.

A worker smelts lead without safety protections in Dhaka, Bangladesh. (photo: Jonathan Raa/NurPhoto/Corbis/Getty Images)

A worker smelts lead without safety protections in Dhaka, Bangladesh. (photo: Jonathan Raa/NurPhoto/Corbis/Getty Images)

And we aren’t doing much to prevent it.

Lead levels in Flint’s children spiked after the city failed to properly treat a new water source. Eventually, the state of Michigan and city of Flint were forced to agree to a $641 million settlement for residents affected by the lead poisoning, and several state officials, including former Gov. Rick Snyder, were criminally indicted for their role in exposing children to lead.

While estimates differ, a prominent study found that the share of screened Flint children under the age of 5 with high lead levels reached 4.9 percent in 2015, up from 2.4 percent before the problems with lead contamination began. According to the CDC guidance at the time, a level of lead in blood that would be considered high was 5 micrograms per deciliter (µg/dL) (the agency has since lowered the threshold to 3.5 µg/dL). That said, no level of lead exposure is considered safe, and even exposure well below public health recommendations can be quite harmful. That nearly 5 percent of young children in Flint faced exposure to rates that high is a travesty.

As scandalous as the Flint lead crisis is, it’s sobering to know that it may be just the tip of the iceberg globally.

A recent systematic evidence review, widely cited and respected in the field, pooled lead screenings from 34 countries representing two-thirds of the world’s population. The study estimated that 48.5 percent of children in the countries surveyed have blood lead levels above 5 µg/dL.

Let me repeat that: Flint became the symbol of catastrophic lead exposure in the United States. The breakdown of a long-neglected system was so terrible that it led to headlines for months and even became an issue in the 2016 presidential election. Yet children in low- and middle-income countries are, per this estimate, 10 times likelier to have high blood lead levels than children in Flint were at the height of the city’s crisis.

The lead problem is global. It’s catastrophic in scope and hurting children’s ability to learn, earn a living when they grow up, and function in society. Yet lead has gotten comparatively little attention in the global public health space. Charities globally are spending a total of just $6 million to $10 million a year trying to fight it. For comparison, individuals, foundations, and corporations in the United States alone spent $471 billion on charity in 2020.

Childhood lead poisoning is a tragedy — and it is one that would be relatively inexpensive for the world to fix.

What lead does to humans

Lead is soft, plentiful, and easy to mine and manipulate, which is why humans have been harnessing it for various purposes for thousands of years. Ancient Romans used lead for everything from water piping to pots and pans to face powder to paint to wine preservatives.

Today, common uses of lead still include cookware, paint, and piping, along with lead acid batteries (a technology still used for most car batteries, even in hybrids), and plane fuel. For decades, a major use of lead was as an additive to gasoline meant to prevent engine knocking. While the US started phasing out leaded gasoline for passenger cars in 1973 — and only finished in 1996 — the last country to officially abandon it, Algeria, did so last year.

The reason we phased it out is that — as we have known at least since Roman times — lead is extremely bad for humans.

“Lead causes toxicity to multiple organs in the human body,” Philip Landrigan, a doctor and professor at Boston College who conducted key studies on the effects of lead in the 1970s, told me. “In infants and children, the brain is the big target. But we also know very well that adults who were exposed to lead — especially people exposed occupationally [and thus exposed to high amounts] — are at very substantially increased risk of heart disease, hypertension, and stroke.”

Lead exposure can be quite deadly. Some of the best evidence here comes from a recent study examining Nascar’s decision to ban leaded gasoline from its cars in 2007. Overall, mortality among elderly people fell by 1.7 percent in counties with Nascar races after the races stopped using leaded gas. The authors estimate that Nascar and other leaded gas races had caused, on average, about 4,000 premature deaths a year in the US.

The biggest costs of lead, though, are its effects on the brains of children. The developing brain is, in Landrigan’s words, “exquisitely sensitive” to the effects of lead. “It damages neurons; the active cells in the brain that we use for reflexing, running, and jumping, everything,” he explains.

The effects of lead “seem to concentrate in the prefrontal cortex,” Bruce Lanphear, a leading medical researcher on lead’s effects based at Canada’s Simon Fraser University, told me. That part of the brain is smaller in adults who were exposed to lead as children, he added. Neuroscientists believe the prefrontal cortex plays a key role in executive functioning: the ability of people to choose behaviors in pursuit of conscious goals rather than acting on impulse. “It’s what distinguishes us from other animals, what makes us human,” Lanphear said.

For just about any variable you can imagine related to human behavior and thinking, there is probably research indicating that lead is harmful to it.

High lead exposure reduces measured intelligence substantially. “If we compare kids at the lower and higher end [of lead exposure], we saw a 5-8 point IQ difference,” Aaron Reuben, a psychologist at Duke University and lead author on a study looking at a cohort in New Zealand, told me. Higher lead levels are associated with higher rates of ADHD and negative changes in personality.

Reuben says his research has found that kids exposed to lead are “less conscientious, less organized, less meticulous. They’re a little less agreeable; they don’t get along as well with others. They’re more neurotic, meaning they have a higher propensity to feel negative emotions.”

In recent years, some writers have embraced a theory that declining lead exposure (mostly due to the gradual removal of lead from gasoline) was a leading factor in the drastic decline in crime, especially violent crime, in the United States in the 1990s. Whether or not lead explains that specific historical phenomenon, several high-quality studies have found a relationship between high lead exposure and crime and delinquency.

One found that Rhode Island schoolchildren exposed to lead were dramatically likelier to be sent to detention. Another, looking at the introduction of lead pipes in the late 19th century, found that cities with the pipes had considerably higher homicide rates. A third, looking at reductions in lead in gasoline in the late ’70s and early ’80s, found that the phase-out led to a 56 percent decline in violent crime.

This evidence is suggestive, not definitive. A recent meta-analysis argued that when you take into account the likelihood of publication bias (that is, that studies showing a strong effect of lead on crime are likelier to be published than studies finding little effect), the effect size could be quite small and not explain any of the decline in homicide rates in the US.

But the idea that lead has a high social cost does not hinge on a specific narrative about crime. Lead appears to be consistently costly across outcomes from IQ to personality to impulse control to elderly mortality.

“Lead has been really bad and very significant in the history of social behavior,” Jessica Wolpaw Reyes, an economist at Amherst College and author of that last paper, summed it up to me.

Lead exposure is still very common in the developing world

The story of lead exposure in the United States and other rich countries in recent decades has in fact been enormously positive. Yes, there have been disastrous lapses as in Flint, but they stand out precisely because they are such an exception to recent trends.

A recent paper from CDC researchers estimated that from 1976 to 1980, fully 99.8 percent of American children aged 1 to 5 had levels of lead in their blood of over 5 micrograms per deciliter. From 2011 to 2016, the share was down to 1.3 percent. In a major triumph for environmental public health, high-level lead exposure went from the norm to an aberration in just four decades, in large part due to the abandonment of lead in gasoline.

As bad as things are in developing countries today, lead exposure in those nations is much less prevalent than it was in the US 40 years ago — a sign of global progress. That said, lead exposure in developing countries appears to be quite high compared to exposure in rich countries today.

Several experts I spoke to pointed to the 2021 evidence review led by Bret Ericson that I referenced above as the best summary of what we know about how common lead exposure is in low- and middle-income countries. In 34 nations, which together account for over two-thirds of the world’s population, the researchers were able to find blood lead surveys they considered reasonably representative of the country’s children, usually conducted by nonprofits or government agencies.

Overall, those studies estimated that 48.5 percent of children had high lead levels (defined as above 5 ug/dL). Levels of exposure varied greatly, with surveys in a few countries (like Tanzania and Colombia) not finding any children with blood lead levels above 5 ug/dL, and other countries showing huge majorities with levels that high. In Pakistan, for instance, over 70 percent of children had high blood lead levels.

Lead levels this high imply incredible amounts of damage to health and well-being. The Global Burden of Disease study published in the Lancet in 2019 estimated that about 900,000 people die due to lead annually, representing 21.7 million years of healthy life lost. One attempt to quantify the economic costs of lead in low- and middle-income countries estimated that in 2011, the burden was around $977 billion annually, or 1.2 percent of global GDP.

Lead in poor countries comes from everything from batteries to turmeric

While the numbers above give a sense of the lead problem’s scale, they are not definitive. One consistent message I heard from experts is that we simply need a lot more data on lead in low- and middle-income countries.

The Ericson evidence review concluded, “there is a paucity of rigorous data on lead exposure in the general populations of [low- and middle-income countries].” Most countries in Africa, and several in Latin America and Central Asia, did not have data usable for the review.

Lead experts also disagree about what the primary sources of lead exposure in developing countries might be. Pure Earth, the largest nonprofit working on lead contamination in developing countries, has generally focused on reducing exposure from informal recycling of lead-acid car batteries. In many developing countries, such recycling happens in mom-and-pop operations in backyards, with no protection for the recycling workers or neighboring residents from the resulting fumes.

But more recently, Pure Earth has also been working on reducing exposure from cookware and spices. Stanford researchers Jenna Forsyth and Stephen Luby have found that turmeric spice in Bangladesh is very often cut with lead chromate. That’s right: The turmeric that Bangladeshis use for cooking often has lead added to it. Lead is very heavy, and in lead chromate form, it’s a vibrant yellow, which makes it an easy way to adulterate and amplify the color of turmeric. The problem likely spans beyond just Bangladesh. Consumer Reports has found that even in the US, grocery stores were selling turmeric cut with heavy metals.

Environmental scientists have worried for years about lead exposure from ceramics in Central America, where traditional processes often use lead for glazing. But Pure Earth’s Richard Fuller told me that ceramics in India often contain lead too, and in many low-income countries, aluminum cookware is contaminated as well. Aluminum pots and pans in these contexts “are generally made in local recycling places where the recyclers are throwing all this scrap metal in,” he said. “It’s almost impossible for them to not get lead in.” In turn, that lead can seep into food cooked using these tools.

But other, smaller organizations focus on different lead sources. Lead Exposure Elimination Project (LEEP), founded in 2020, has mostly focused to date on lead paint. Just as lead can make turmeric more vibrant, it can make yellows and whites in paint more vibrant too. “We decided to start with lead paint because it seemed like a significant source of exposure, and there’s an obvious approach to tackling it, which is regulation,” Lucia Coulter, a medical doctor and LEEP’s co-founder, told me.

Tackling lead paint requires introducing new laws and enforcing old ones. Jerry Toe, an official at Liberia’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) who has worked with LEEP on lead paint, told me that while the country had adopted a law banning lead paint in 2004, the Liberian EPA had still not formalized any regulations deriving from it by 2019, when he came to the issue. It took a LEEP study in Malawi for regulators in that country to conduct regular monitoring of lead levels in paints for sale.

Imran Khalid, a researcher at Pakistan’s Sustainable Development Policy Institute and director at the World Wildlife Fund Pakistan, has had a similar experience. “The implementation [of lead regulations] is quite poor,” he told me. “Our environmental laws are primarily lip service.”

Khalid has been working with LEEP on paint sampling studies in which he and other researchers obtain paint from stores and test it for lead. Zafar Fatmi, a professor at Aga Khan University in Karachi, said that in his initial testing, around 40 percent of paints had high levels of lead.

Khalid notes that some high-lead paint comes from major multinationals, which makes enforcement a challenge. “For a country like Pakistan that’s already going to the IMF [International Monetary Fund] again and again” asking for loans, he explains, “people become very hesitant [about criticizing multinationals] when environmental issues come up.”

And there are other possible sources in poor nations as well, including some of the same ones still plaguing rich countries. “A lot of homes in African countries still have lead pipes, and nobody is talking about getting rid of them or what problems they’re creating,” Jerome Nriagu, a professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Michigan and one of the first US researchers to raise alarms about lead in Africa, told me.

An urgent need for more funding and more data

Last year, the effective altruist research group Rethink Priorities released a comprehensive report attempting to assess how many groups were working on lead exposure in poor countries and how much more could be done on the issue. Their answers: Not many are working on this, and those that are could likely use millions of dollars more every year to spend on effective projects.

Pure Earth, formerly known as the Blacksmith Institute, is by far the largest player, but it spends just $4 million to $5 million a year on lead. “Summing estimated budgets of other organizations, we believe that donors spend no more than $10 million annually on lead exposure,” Rethink Priorities’ Jason Schukraft and David Rhys Bernard conclude.

Much of that funding comes from government sources like the US Agency for International Development and the Swedish equivalent Sida. Outside support for nonprofits, there’s not much public evidence that international aid agencies are investing in lead abatement. With some notable exceptions, like the Center for Global Development, groups working on global health have largely ignored the issue.

Ten million dollars a year, tops, is not much money at all to spend fighting global lead poisoning, even with increased investments directed by donors in the effective altruism community toward Pure Earth and LEEP. “It’s a fairly small community, and it’s remarkably small given the scale of the problem and the scale of the impacts,” Pure Earth’s Fuller said. That helps explain why effective altruist groups like Rethink Priorities and GiveWell have become interested in lead alleviation. It’s a neglected area, where each additional dollar can go a long way.

So what else could be done with more money and resources? One simple answer is better research. When I asked Fuller and his colleague Drew McCartor what additional studies they’d do if they could, they immediately said basic lead exposure surveys in affected countries and basic sourcing analysis to see where lead is coming from in those countries.

We have such poor data on how many people (especially children) are being exposed to lead and on how they’re being exposed to lead, that improving that data could in turn significantly enhance nonprofits’ ability to target interventions effectively. If, say, lead pipes are a bigger source of exposure in sub-Saharan Africa than previously thought, that would change how Pure Earth and other groups allocate funds; likewise, a finding that lead paint is not a significant source of exposure might change LEEP’s approach.

Rethink Priorities concluded that “existing and potential new NGOs in the area currently have the capacity to productively absorb $5 to $10 million annually in additional money,” and that sums above that amount might be productively usable too.

That’s just not a lot of money in the context of US foundations or even foreign aid budgets — especially for something we know is severely injuring children and killing adults in the developing world.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment