Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The debt ceiling deal reveals the arbitrary nature of the supposed customs of the upper chamber

If all of this sounds gimmicky, it’s because it is. The filibuster has been the subject of significant debate this year, with members of both parties treating it as a hallowed institution. When it comes to the debt ceiling, Republicans have been insistent that Democrats raise the debt ceiling on their own, while refusing until now to allow a simple majority vote. The debt ceiling deal reveals how fundamentally subjective and arbitrary the supposed traditions and customs of the upper chamber are, and it provides the latest example of how the Senate is a broken institution incapable of responsive and logical solutions to our nation’s problems.

The House text of the debt ceiling measure provides for its expedited consideration, short circuits Senate debate and defangs a potential filibuster on the substance of the bill. This is all happening with Mitch McConnell’s buy-in, which is crucial. But it strongly suggests that certain institutional dividing lines aren’t as bright as some members of the world’s most exclusive club have suggested.

With this workaround, Senate Democrats have invited a fair question: If certain filibuster exceptions can be made for the debt ceiling, then why not for the other existential matters pending before Congress? Already, voting rights and democracy reform activists are pointing out the potential hypocrisy. Given the precarious situation at the Supreme Court, abortion rights advocates aren’t likely too far behind, with immigration reform activists likely to try to follow suit. Do these issues not also merit privileged consideration?

This ordeal has reaffirmed how the reflexive institutional conservatism of the Senate prevents matters that Democrats prioritize from due consideration. There’s an asymmetry to how the Senate’s structure treats the parties’ respective agendas that consistently gives the GOP the upper hand. Judge confirmations, tax cuts and regulatory overhauls can all be accomplished with simple majorities. Rational gun legislation, protecting DACA immigrants, modest police reform and rescuing the nation from the fiscal cliff (among other things) require some level of buy-in from an intransigent opposition. It’s an imbalance unlikely to change anytime soon unless Democrats decide to do something about it.

The debt ceiling debacle has also blown a giant hole right through one of the principal arguments of certain senators who fervently defend the filibuster: that bipartisanship is a prerequisite for important matters that make it out of the Senate. To be clear: Democrats are the ones raising the debt ceiling. Republicans are just promising not to obstruct — this time, anyway. This is not a sustainable path, and it will only breed more distrust in the Senate, an institution already suffering from an approval deficit. Democrats who continue to treat the filibuster as some sacred feature of the Senate instead of what it is — a fairly arbitrary rule that can clearly be altered on a whim — should be asked what they’re actually defending.

Hard issues can’t be sidestepped forever, and patchwork solutions inevitably give way to more severe problems. My hope is that Democrats in Congress won’t have to learn this lesson the hard way. If nothing else, they should move next year toward defusing the debt ceiling bomb through the end of President Biden’s term. It’s more than fair to wonder whether a future GOP House majority would go along with averting fiscal calamity while a Democrat occupies the White House.

What’s abundantly clear is that the Senate is not giving Americans its best. That must change before what’s left of its credibility also falls over the cliff.

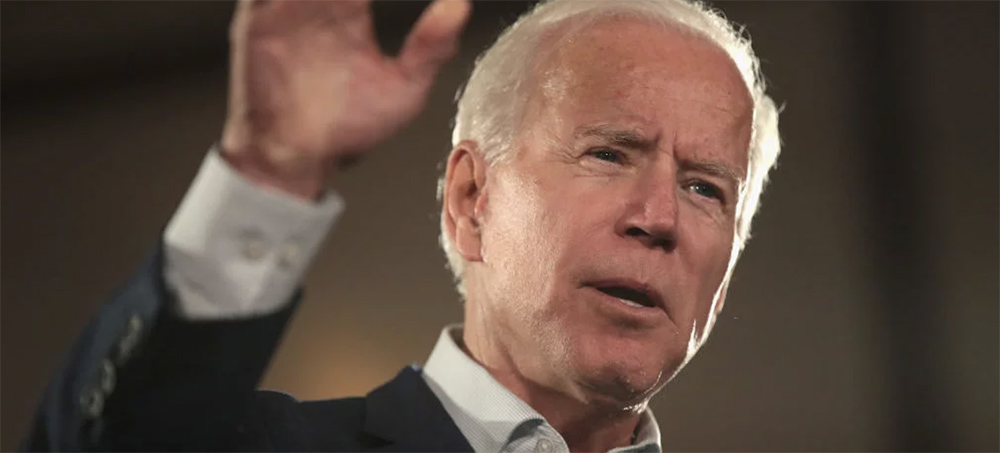

Joe Biden. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Joe Biden. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: President Biden may soon vote to approve the largest military spending bill since World War II, with a 5% increase over last year’s military spending bill. The $768 billion military budget is $24 billion higher than what Biden requested despite the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. The package includes funds aimed at countering China’s power and to build Ukraine’s military strength. It also includes nearly $28 billion in nuclear weapons funding.

The bill is headed to the Senate, then to President Biden, after the House approved the bill late Tuesday night with more Republicans than Democrats voting for it. Among those who voted no was progressive New York Congressmember Jamaal Bowman, who tweeted, quote, “It is astounding how quickly Congress moves weapons but we can’t ensure housing, care, and justice for our veterans, nor invest in robust jobs programs for districts like mine.” Bowman also criticized how the compromise bill strips funding that would have established an office for countering extremism in the Pentagon, saying the bill, quote, “must also protect the Black men and women who are disproportionately the target of extremism and a biased military justice system,” unquote.

Also absent from the bill is a provision to require women to register for the draft.

Separately, the Senate voted down a bipartisan bid by Senators Bernie Sanders, Rand Paul and Mike Lee to halt $650 million in U.S. arms sales to Saudi Arabia amidst the devastating ongoing war on Yemen.

For more, we’re joined by Bill Hartung, director of Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy, author of a new report, “Arming Repression: U.S. Military Support for Saudi Arabia, from Trump to Biden,” his latest book, Prophets of War: Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex.

Bill Hartung, welcome back to Democracy Now! First of all, if you can just respond to the House passage of the largest weapons spending bill in U.S. history since World War II?

WILLIAM HARTUNG: Well, I think it’s an outrage, if you look at what we really need. You know, in the roundup, you talked about the need to spend on pandemic preparedness. The world is on fire with the impacts of climate change. We’ve got deep problems of racial and economic injustice in this country. We’ve got an insurrection and violence trying to undermine our democracy. So the last thing we need to do is be throwing more money at the Pentagon. And it’s a huge amount. It’s more than we spent in Vietnam, the Korean War, the Reagan buildup of the ’80s, all throughout the Cold War. And as you said, even at the time as Biden has pulled out U.S. troops from Afghanistan, the Pentagon budget keeps going up and up.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Bill Hartung, could respond specifically to the fact that the budget is $24 billion more than what was requested? Is it common to have such a huge difference in terms of the amount requested and the amount granted, $24 billion?

WILLIAM HARTUNG: Well, Congress often adds money for pet projects — Boeing aircraft in Missouri, attack submarines in Connecticut and Virginia — but nothing at this level. You know, $24 billion is the biggest congressional add-on that I can think of in recent memory. So it’s kind of extraordinary, especially, as we said, when the endless wars should be winding down.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And can you talk about some of the key figures in Congress who have been pushing for an increase?

WILLIAM HARTUNG: Well, you’ve got people like James Inhofe, who’s the Republican lead on the Senate Armed Services Committee, who’s basically said we need to spend 3 to 5% more per year in perpetuity, which would push the budget over a trillion dollars within five to six years. He is always touting a report called the National Defense Strategy Commission report, which was put together primarily by people who were from the arms industry, from think tanks funded by the arms industry. Basically, it was a kind of a special interest collection that were pushing this.

And then you have Mike Rogers from Alabama, who’s the key player on House Armed Services. He’s got Huntsville in his state, and Huntsville is sort of the missile capital of America — Army missiles, missile defense systems. He also gets hundreds of thousands of dollars from the weapons industry for his reelection. So, there’s a strong kind of pork barrel special interest push by the military-industrial complex that help bring about this result.

AMY GOODMAN: The Senate voted down a bipartisan bid by Senators Bernie Sanders, Rand Paul and Mike Lee to halt the $650 million in U.S. arms sales to Saudi Arabia, this amidst the devastating ongoing war on Yemen. I want to play a clip of Senators Paul and Sanders addressing the Senate Tuesday.

SEN. RAND PAUL: The U.S. should end all arms sales to the Saudis until they end their blockade of Yemen. President Biden said he would change the Trump policy of supporting Saudi’s war in Yemen, but it’s not all that apparent that policy has changed. … We commission these weapons, and we should not give them to countries who are starving children and are committing, essentially, genocide in Yemen.

SEN. BERNIE SANDERS: President, I find myself in the somewhat uncomfortable and unusual position of agreeing with Senator Paul.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that was Senator Sanders and Paul. Bill Hartung, you’re the author of the new report headlined “Arming Repression: U.S. Military Support for Saudi Arabia, from Trump to Biden.” Can you talk about the significance of this, what was voted down?

WILLIAM HARTUNG: Well, these missiles are air-to-air missiles, which can be used to enforce the air blockade that’s been put over Yemen. So, the Saudis have bombed the Sana’a airport runways. They’ve tried to keep ships from coming in with fuel. And as a result, costs of medical supplies now are out of the reach of the average person of Yemen. People haven’t been able to leave the country for medical treatment. Norwegian Refugee Council and CARE say 32,000 people have probably died just for lack of being able to leave the country for that specialized care. Four hundred thousand children are at risk, according to the World Food Programme, of starvation because of the blockade. Millions of Yemenis need humanitarian aid just to survive, and the Saudi blockade is making it increasingly difficult to get that aid or to get commercial goods that they need.

So, basically, this is a criminal enterprise run by Mohammed bin Salman. And Joe Biden said, when he was a candidate, Saudi Arabia, we’d treat it like an pariah; he wouldn’t arm them. In his first foreign policy speech, he said the U.S. should stop support for offensive operations in Yemen. And yet he’s approved a contract for maintenance of Saudi planes and attack helicopters, and now this deal for the missiles. So he’s basically gone back on his pledge to forge a new relationship with Saudi Arabia and to use U.S. leverage to end the blockade and the war itself.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Bill, before we conclude, just to go back to the military budget, could you comment specifically on the $28 billion earmarked for nuclear weapons?

WILLIAM HARTUNG: Well, unfortunately, this bill doubles down on the Pentagon’s buildup of a new generation of nuclear weapons, a new generation of nuclear warheads, which is, of course, the last thing we need at a time of global tensions. You know, in particular, there was even a provision that said it’s not allowed to reduce the number of intercontinental ballistic missiles, which are the most dangerous weapons in the world because they could easily be used by accident if there were a false alarm of attack, because the president has only minutes to decide whether to use these things. So, I think that’s one of the biggest stains on this bill, is basically continuing to stoke the nuclear arms race, not only at great cost but at great risk to the future of the planet.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, the China and Russia being used as justification for weapons sales and increased military budget, can you compare the U.S. military budget to theirs?

WILLIAM HARTUNG: Well, the U.S. spends about 10 times what Russia spends, about three times what China spends. It has 13 times as many active nuclear warheads in its stockpile as China does. We’ve got 11 aircraft carriers of a type that China doesn’t have. We’ve got 800 U.S. military bases around the globe, while China has three. So this whole idea that China and Russia are military threats to the United States has primarily been manufactured to jump up the military budget. And so far, unfortunately, at least in the halls of Congress and the Biden administration, that’s been successful.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Hartung, we want to thank you for being with us, director of the Arms and Security Project at the Center for International Policy. We’ll link to your new report, “Arming Repression: U.S. Military Support for Saudi Arabia, from Trump to Biden.” Hartung’s latest book, Prophets of War: Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex.

Next up, calls are growing for President Biden to extend the moratorium on student debt payments as millions face a debt crisis during the pandemic. We’ll speak with the Debt Collective’s Astra Taylor about her new animated film, Your Debt Is Someone Else’s Asset. Stay with us.

A poll worker talks to a voter before they vote on a paper ballot on Election Day in Atlanta on Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020. A federal judge, on Thursday, Dec. 9 2021, has rejected motions to dismiss eight lawsuits that challenge Georgia’s sweeping new election law. (photo: Brynn Anderson/AP)

A poll worker talks to a voter before they vote on a paper ballot on Election Day in Atlanta on Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020. A federal judge, on Thursday, Dec. 9 2021, has rejected motions to dismiss eight lawsuits that challenge Georgia’s sweeping new election law. (photo: Brynn Anderson/AP)

Republicans are going full Jim Crow to hold onto power

The purges of at least six county election boards is a direct, but less publicized result of new election rules that Georgia’s GOP-controlled legislature passed after Democrats swept the state’s senate races and helped deliver the White House to President Joe Biden. While most attention has been paid to fact that the new election law is a naked effort to keep Black and Hispanic voters from the polls, the law also lets Republicans take control of local election authorities altogether.

It’s an important step because Georgia’s elections are run by local officials including voting boards like one in Spalding County, where Reuters reports that four Black local election officials—all Dems—have been replaced by white Republicans, who immediately banned Sunday early voting in the county.

From Reuters

But this was an entirely different five-member board than had overseen the last election. The Democratic majority of three Black women was gone. So was the Black elections supervisor. Now a faction of three white Republicans controlled the board – thanks to a bill passed by the Republican-led Georgia legislature earlier this year. The Spalding board’s new chairman has endorsed former president Donald Trump’s false stolen-election claims on social media.

The panel in Spalding, a rural patch south of Atlanta, is one of six county boards that Republicans have quietly reorganized in recent months through similar county-specific state legislation. The changes expanded the party’s power over choosing members of local election boards ahead of the crucial midterm Congressional elections in November 2022.

The unusual rash of restructurings follows the state’s passage of Senate Bill 202, which restricted ballot access statewide and allowed the Republican-controlled State Election Board to assume control of county boards it deems underperforming. The board immediately launched a performance review of the Democratic-leaning Fulton County board, which oversees part of Atlanta.

As Georgia shifts from a solidly red state with a legislature controlled by conservative whites to a swing state with a browning population, Republicans feel their grip on power slipping. Atlanta politics is still dominated by Democrats, even as white voters slightly outnumbered Black voters in the 2020 presidential election. Georgia now has more Black woman legislators than any other state, and all of them are Democrats. Stacey Abrams, the powerhouse political organizer, has a $100 million war chest and is running for governor again next year.

At least 55 migrants were killed and 59 others were injured when a truck migrants were traveling in crashed into a bridge in Chiapas, Southern Mexico on December 9, 2021. (photo: Stringer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

At least 55 migrants were killed and 59 others were injured when a truck migrants were traveling in crashed into a bridge in Chiapas, Southern Mexico on December 9, 2021. (photo: Stringer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

A crash that killed more than 50 migrants this week highlights the dangers that they face in Mexico, and how U.S policy to deter them isn't working.

But they made it less than three hours in the tractor trailer, packed in so tightly that every other person was standing. As the truck rounded a curve in the southern city of Tuxtla, Gutierrez the next day, the driver lost control and slammed into a lightpost. The trailer detached from the main cabin and flipped over, flinging migrants onto the asphalt and a nearby wall, killing at least 55 and sending another 106 to the hospital.

Fifteen-year-old Byron woke up surrounded by dead bodies, with an elderly man offering him water.

“I am poor,” Byron told VICE World News as he sat dazed in the Red Cross Hospital, explaining his decision to migrate. He said he thought he was traveling “direct to New York” in the tractor trailer (only his first name has been used because he’s a minor).

The tragic accident on Thursday in the state of Chiapas, which borders Guatemala, underscores the risks migrants from fragile, violence-ravaged states in Central America as well as other countries in the region and beyond are continuing to take to reach the U.S., despite policies aimed at deterring them. It also highlights the weaknesses of a U.S. strategy that relies on Mexico to stop the flow of migrants before they reach the countries’ shared border. The tractor trailer passed through at least two government checkpoints during its two-hour trip, including one just a mile before the accident site.

Adult migrants traveling in the trailer were being charged around $13,000 to reach the U.S., according to survivors VICE World News spoke with. Unaccompanied minors were charged the lesser price of $4,000, because under the Biden administration they can turn themselves into U.S. Border Patrol agents once they reach the U.S.-Mexico border and be allowed in. Most migrants pay the fee in installments over the course of the trip.

With 1.7 million migrants apprehended at the U.S. border last fiscal year, the most ever recorded, the human smuggling industry is booming. Even by conservative estimates, it’s estimated to be worth billions of dollars.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador accused the U.S. on Friday of moving too slowly to address the root causes of migration. “They don’t act in an executive manner when this deserves urgent attention.”

Mexico’s Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard said that Mexico, Guatemala, the United States and other countries would work together to identify the members and leaders of the “transnational criminal organization responsible for this human tragedy.”

Flanked by Guatemala’s Foreign Minister Pedro Brolo, U.S. Ambassador Ken Salazar and ambassadors from Honduras, Ecuador, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic, Ebrard said that each country would carry out its own investigation and then share information, both to investigate the crash and “to fight human trafficking in all its manifestations.”

But few of the accident victims described themselves as being trafficked. Instead, they said they had taken out loans and put up land as collateral to pay for the journey in the hopes of reaching the U.S. and making a better life for themselves and their families. “It doesn’t matter what happened, we have to keep trying. To improve our lives,” said Elvia, Bryon’s 16-year-old cousin.

Ninety-eight percent of the accident victims were from Guatemala, according to Mexican authorities. Most likely arrived in Mexico in recent days through blind spots on the Guatemala-Mexico border. Led by smugglers, they met up Wednesday in San Cristobal de las Casas, a touristy town in southern Mexico. Around 1 p.m. that afternoon, they climbed into the back of the tractor trailer to continue their journey north.

Smugglers adjust their fees depending on the mode of transportation, and traveling in tractor trailers tends to be one of the cheaper options. There are also VIP options, including in recent years express buses that are safer and deliver Guatemalans to the border in a matter of days.

The Mexican attorney general’s office said that the primary cause of the accident was speeding. The trailer is registered to a company that boasts 24-7 monitoring of the cargo to ensure its security. The driver of the tractor trailer fled following the accident and hasn’t been found.

“I have never seen so much death. It was a slaughter,” said Jorge Goméz, whose house sits in front of the highway and was one of the first people to respond to the accident. He said dozens of victims died on impact. Others were found alive beneath dead bodies. Some survivors fled immediately because they were scared, he said, adding that passersby stole the cell phones of the dead.

“It makes me angry. Furious,” Goméz said. “A thousand meters away is a checkpoint. How is it possible that they let the trailer pass?”

By Friday afternoon, less than 24 hours later, the scene of the accident was barely noticeable. Cars and trucks sped by the only evidence of the tragedy: Piles of bloodied surgical gloves and a small shrine with candles and some flowers.

Byron was already thinking about his next attempt to reach the U.S. His dream is to own a restaurant, he said. Still beat up and bandaged, he asked, “Can we get directly to the U.S. from here?”

Low pay and grueling conditions are causing public school teachers to leave the profession at an alarming rate. (photo: NeONBRAND/Unsplash)

Low pay and grueling conditions are causing public school teachers to leave the profession at an alarming rate. (photo: NeONBRAND/Unsplash)

Chronic disinvestment in public education, a corporate reform model that punishes student poverty, and the pandemic’s disruption of school life are making it impossible for teachers to do the job they love. Many educators are reaching their breaking points.

Kristin Colucci, who teaches English in Lawrence Public Schools in Massachusetts, described the situation at her high school to Jacobin: “One teacher quit, another retired, and there have been no teachers assigned to those classes. Students are literally sitting there by themselves. The message being sent: the class and the students are not worthy of this education.”

Edu-conomists who warn against teacher pay increases like to point out that shortages are district-specific and that overall teacher turnover may actually be lower right now than in recent years. That’s not saying much.

Teacher turnover has been on the rise in the United States since the mid-1980s. In the last decade, we’ve seen a growing crisis of teacher vacancies and declining enrollment in teacher preparation programs. Due to racialized problems like high student debt and poor working conditions, people who are not white are less likely to enter the profession and more likely to leave it, meaning students are deprived of the significant benefits of exposure to a diverse teaching workforce.

Shortages of qualified teachers interfere with learning, inflicting outsize harm on special education students and students in high-poverty districts and racially isolated schools. But the hardships that disproportionately impact marginalized groups of students and teachers are indicative of broad underlying ills that make it harder for all kids to experience the learning conditions they deserve.

When educators accumulate years on the job, they acquire invaluable knowledge about how to gain students’ respect and make high-level scholarship possible. Unfortunately, circumstances stemming from chronic disinvestment and a corporate reform model that punishes poverty make it untenable for many teachers to remain in the classroom.

Institutionalized Babysitting

Teaching is a hard job. Planning and executing lessons that will motivate students with divergent interests and skill sets takes a great deal of time, research, and imagination. Then there’s the labor of evaluating and thoughtfully responding to work from up to ninety students across multiple different classes, providing tailored instruction for English learners and special education students, building rapport with shy or angry kids, fairly dividing one’s attention, maintaining order and ensuring safety, collaborating with colleagues and families, and staying abreast of new developments in the subjects one teaches and the field of education generally.

Nevertheless, many teachers are eager to meet these challenges. The very fact that anyone pursues teaching when, with comparable education, they can earn significantly more money in other fields demonstrates that people are willing to give up a great deal because they are drawn to the vocation of nurturing young minds.

The trouble is that, at every step of the way, teachers are prevented from actually performing this vocation. Their “other duties as assigned” include playing nonteaching roles like bus and lunch cop, because districts are unable or unwilling to hire more staff. Teachers are required to attend meetings at which they play icebreaker games and watch clips of cartoon animals so their administrators can get credit for giving professional development. They may have a single forty-minute preparation period in which to plan and grade for four or five different classes (which is laughable). But they frequently find they can’t use that time for planning and grading because paperwork is piled on them, often at the last minute. In addition to myriad clerical and administrative tasks, they must document instructional interventions and, at many schools, submit detailed weekly lesson plans designed to satisfy their bosses’ checklists rather than excite and challenge learners.

This micromanagement sends a demoralizing message: school, district, and state leaders don’t believe you’ll really do your job if they don’t peer over your shoulder every five minutes. But most educators will tell you that student engagement and trust are the potent incentives keeping them prepared and diligent in their work. Incessantly requiring them to prove that they are, in fact, working is an insulting waste of their time. As is true in any other workforce, there are sure to be some teachers whose practice might benefit from added accountability structures. But applying these structures indiscriminately adds indignity and unnecessary stress to an already high-stakes profession.

“Teach the Standards, Not the Books”

All this teacher data collection is mandated by the same top-down reform initiatives that compel educators to constantly harvest student data in the form of standardized test scores and remediation product outcomes — and offer that data up the chain to be criticized by people who have never set foot in their classrooms.

I became an English teacher because I wanted to help students explore thrilling story-worlds, weave airtight arguments, and unravel sophistical rhetoric. Like an alarming number of my peers, I left the profession after just five years, finding I wasn’t allowed to teach in a way that could inspire my students. Instead of facilitating deep inquiry and lively debate, I was forced to make rushed deposits of scripted curriculum in order to meet standards written by Bill and Melinda Gates–funded reformers.

I was willing to work weekends and ten-hour weekdays for shabby pay in the service of my students — but not in the service of my administrator’s need to convince her bosses we’d “covered” RI.11-12.1 through SL.11-12.6. I was told it didn’t matter if my classes only got to experience fiction through decontextualized excerpts; my job was to “teach the standard, not the book.” But I wanted to teach the books: whole, breathing texts can fascinate young people and ignite their genius. State standards grids make them yawn and pull out their phones, or boil over with justified indignation.

Pandemic Classrooms

I stopped teaching before the arrival of COVID-19. In pandemic classrooms, educators are experiencing all the problems created by underfunding and corporate education reform, plus a new set of ordeals.

As is true for other school personnel, teachers’ workloads are metastasizing due to staffing shortages. John Forte, who teaches history in Trenton Public Schools in New Jersey, told Jacobin that he and his colleagues “have to cover [teacherless] classes constantly, leading to decreased prep time.” Karin Baker, who teaches English and social studies in Amherst-Pelham Regional Public Schools in Massachusetts, explained to Jacobin that because her school is missing a custodian, teachers must clean the floors “when they get too bad.”

Educators also have novel responsibilities like developing ad hoc hybrid learning arrangements as students enter quarantine, enforcing masking and physical distancing, doing their own contact tracing, and finding sensitive ways to communicate about COVID-19 norms with COVID-skeptical students. Additionally, in today’s extreme political climate, parent outrage (ginned up in bad faith) has added another layer of anxiety to lesson planning.

“A Huge Mismatch”

In the underresourced areas where school staffing shortages are most extreme, teachers were already doubling as nurses and social workers. This is even more true now, as the need for mental health care is skyrocketing due to the preventable trauma associated with being a poor kid in the United States in 2021. Students have experienced personal tragedy, profound instability, and extreme turmoil in the last two years. In high-poverty places hard hit by the pandemic, kids have lost caregivers and other loved ones at an almost unfathomable rate, putting them at risk for problems associated with grief, worry, exhaustion, institutionalization, and material need.

Forte told Jacobin that his “students are dealing with lots of social and emotional problems like trauma,” and Baker described students “who are unable to participate in classes because they are too consumed by their emotional issues.” In my role as a school adjustment counselor, I am seeing widespread anxiety and a high number of students presenting with suicidality and other expressions of despair. A sense of nihilism colors the learning environment as young people struggle to come to terms with our upside-down world.

Winifred Martin is a licensed social worker who supports students in Springfield Public Schools in Massachusetts. Martin told Jacobin that the high-needs students she works with “want to feel loved and inspired” and quoted a student who told her they long “to be seen.”

But while young people require space to process and adapt to their realities, heal, and rediscover joy, many districts are hamstringing educators’ ability to provide that space. Instead, school, district, and state leadership bodies are intensifying the pressure to rapidly remediate, forcing teachers to implement developmentally inappropriate programs aimed at raising standardized test scores. As child development scholar Nancy Carlsson-Paige explained to Jacobin:

Concerns about children and youth as they return to school have been focused on the narrow idea of “learning loss” and not on the needs of the whole child — not on their physical, emotional, social, and mental health needs, and not even on their genuine learning needs. Schools are stuck in a rigid and limited definition of education that has taken hold increasingly over the last twenty years, leaving them largely incapable of providing what children and youth so urgently need at this time.

A higher than usual incidence of student fights and other disciplinary issues may be adding stress to working and learning conditions. Lawrence Public Schools is a district under Massachusetts receivership, or state takeover, due to low test scores — which are reliably associated with the economic precarity widely experienced by Lawrence students. A teacher in Lawrence who, fearing retaliation, asked to remain anonymous, reported significant student conflict and connected this to a lack of support for students and staff. He told Jacobin that “this year, as most years, feels like criminal malpractice” at the high school where he teaches and that “our test scores are consistently prioritized over student learning.”

Researchers say confrontational behavior can be linked to play deprivation. Education reform has thrust ineffective drill-based instruction on poor children starting at a very young age, robbing them of the developmentally vital experience of learning through self-directed activity. The hysteria over pandemic learning loss has pushed teachers to cram lessons with content for which students are wholly unprepared — rather than allowing them to design student-centered curriculum using their expert knowledge of children’s needs and interests.

A teacher in Auburn School Department in Maine, who also requested anonymity, told Jacobin:

We’re . . . using a new literacy curriculum which is very rigid. . . . So, I have fourth graders who are being asked to do work that’s completely new to them, but they’re asking about letter formation. . . . It’s a huge mismatch. The district is trying really hard to raise our test scores but not acknowledging that kids have been living through a pandemic, and it’s just very unrealistic, and the pressure comes down to teachers.

President Joe Biden’s Department of Education could address this problem by attempting to follow through on Biden’s campaign commitment to end the use of standardized testing in public schools. Instead, the department has opted for business as usual. Never mind that under corporate education reform and state disinvestment, business as usual has been steadily draining K-12 classrooms of the vibrant, beautiful things that make students and teachers want to wake up in the morning and come to school.

Breaking Points

Teachers are not even close to adequately compensated for their multifaceted, indispensable labor of love — or for the stressful busywork that interferes with that labor. While wages in other job markets typically rise along with demand, teachers’ inflation-adjusted wages have diminished over time. Some districts have used pandemic relief money to improve salaries and keep teachers in classrooms. But fearing a “fiscal cliff” when the relief expires, others have declined to do so. Stephen Owens, a K-12 policy analyst at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, told Jacobin:

Districts are right to be wary of a “fiscal cliff” if and only if states continue shortchanging public education. There is another vision, however, where states use the federal money to step up investments in the system that educates 90 percent of the nation’s children. . . . States could increase funding to pick up the slack when the COVID dollars are no longer available.

Before COVID-19, paltry salaries were supplemented by powerful nonpecuniary rewards, like the pride teachers feel when facing a classroom of smiling students eagerly engaged in dialogue. Social distancing, remote learning, and innumerable added stressors upon reopening have made it much harder to feel those rewards. All of this is compounded by the fact that educators are risking their health to teach in person, using up their sick days to quarantine, and often feeling that the leaders in charge of their working conditions do not value their safety.

This is not an unsolvable riddle. Federal and state governments can enable districts to make their buildings safer, purchase supplies, hire support staff, and pay teachers fairly so they don’t need second jobs to sustain themselves. The US Department of Education can forgive student debt and make higher education universally accessible so people of all different backgrounds can become teachers. Biden can support the bipartisan legislators calling for an end to the reform movement’s obsession with data for data’s sake. Above all, education leaders can begin to allow teacher and student input to truly drive decision-making.

Or, we can continue to watch as passionate, experienced educators reach their breaking points.

A woman is attached to an oxygen tank at a hospital in Kabul. One expert said the country's Covid-19 response had almost ground to a halt. (photo: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

A woman is attached to an oxygen tank at a hospital in Kabul. One expert said the country's Covid-19 response had almost ground to a halt. (photo: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Health experts issue dire warning as staff go unpaid and medical facilities lack basic items to treat patients

With the country experiencing a deepening humanitarian crisis since the Taliban’s seizure of power in August amid mounting levels of famine and economic collapse, many medical staff have not been paid for months and health facilities lack even the most basic items to treat patients.

Dr Paul Spiegel, director of the Center for Humanitarian health at Johns Hopkins University, said that on a recent five-week trip to the country he had seen public hospitals – which cater for the most vulnerable – lacking fuel, drugs, hygiene products and even basic items such as colostomy bags.

He said the Covid-19 responsehad almost ground to a halt and called for a more nuanced response to western sanctions in order to avert a deeper public health disaster.

“It’s really bad and it is going to get a lot worse,” Spiegel, a former chief of public health at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees among other high-profile humanitarian assignments, told the Guardian.

“There are six simultaneous disease outbreaks: cholera, a massive measles outbreak, polio, malaria and dengue fever, and that is in addition to the coronavirus pandemic.”

Some parts of the primary healthcare system were being funded through a two-decades-old scheme, Spiegel said, but large parts remained largely unsupported, even as health officials, international organisations and NGOs have been required to restart programmes on hold after the Taliban regained control of the country in August.

“I’ve been everywhere during my career. What is shocking is that you don’t normally have an abrupt halt to everything. The UN organisations and NGOs supporting healthcare in Afghanistan are not just dealing with acute emergencies, they’re having to respond to getting the basics running.

“For example, there are supposed to be 39 hospitals dealing with Covid-19 cases of which 7.7% is fully functioning. And it’s not just the hospitals. It’s the whole thing that glues together public health systems: surveillance systems, testing and there’s very little oxygen to treat those who do have Covid.”

He described the main referral hospital for infectious diseases in Kabul as “on its knees”.

“None of the staff have received salaries for months, though most are still coming in. There is hardly any medicine and they are cutting tress in the courtyard to heat the rooms because there is no gas. They’ve also sent their ventilators to the Afghan Japan hospital to treat Covid cases but that is also struggling.”

His comments reflected mounting concern over the collapse of healthcare across Afghanistan, a country of 23 million people. Exacerbating the issue is that Afghanistan’s economic issues, with the IMF warning of a contraction of some 30%, have plunged ever more people into poverty, which has had a knock-on effect for those needing healthcare but unable to afford to seek it.

Outside of Kabul and other major cities, Spiegel said the situation was even worse.

“There is a provincial hospital in Sarobi outside Kabul I visited. There was insufficient water and soap for hygiene protocols,” he said.

“There was a small child who had been born at the hospital with an anal fistula. She was so sick that they had put a colostomy in but they had no bags and so they were using whatever material find – like toilet paper – to collect from the colostomy.”

Dave Michalski, head of programme at Doctors Without Borders in Afghanistan, last week warned in an interview with NPR that there likely to be Afghans in need of healthcare who were not able to access even the reduced levels available.

“How many people are being blocked [from seeking healthcare],” he asked. “How many people are not taking the bus to the next province to find healthcare that is working because their own provincial health care system is closed or because there are no drugs on the shelves.

“And if you don’t have the money to travel around to find a private health care facility … and many private health care facilities are also in trouble because of supply lines.”

The UN children’s organisation Unicef has warned that the growing crisis in the country’s health system is exacerbating Afghanistan’s mounting malnutrition issues.

“The current humanitarian situation in Afghanistan is dire, especially for children. Winter has already set in and, without additional funding, Unicef and partners will be unable to reach the children and families that need us the most,” said Alice Akunga, Unicef’s Afghanistan representative.

“As families struggle to put nutritious food on the table and health systems are further strained, millions of Afghan children are at risk of starvation and death. Others struggle to access water and sanitation, are cut off from their schools and at heightened risk of violence.”

Spiegel said the west needed to find a different approach to the imposition of sanctions on the Taliban: “There needs to be much more nuanced way of implementing sanctions than using such a blunt instrument [as they are currently configured],” he said.

“While understanding concerns about the Taliban … the reality is that a lot of people will die because of them.”

A red wolf pauses briefly to smell the air after stepping foot into the wild for the first time at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. (photo: Running Wild Media/Endangered Wolf Center)

A red wolf pauses briefly to smell the air after stepping foot into the wild for the first time at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. (photo: Running Wild Media/Endangered Wolf Center)

Saving animals from extinction is a creative process, according to Endangered Wolf Center’s Regina Mossotti.

I’ve never managed to spot a red wolf in the swampy flatlands of eastern North Carolina, my home state — and the only place in the world where Canis rufus still lives wild. Although red wolves were once abundant throughout the US, ranging from eastern Texas through the Southeast and southern New England, they are now the most endangered wolf on the planet. Fewer than 10 of them are known to exist outside captivity. About 240 others are housed in a network of zoos and nature centers, part of an Association of Zoos and Aquariums species survival plan keeping them from extinction.

The second most endangered canids, Mexican gray wolves, are faring only slightly better, with about 200 found in the wild, primarily in the Southwest.

Captive breeding programs at places like the Endangered Wolf Center play a vital role in pulling both species back from the brink. But if the ultimate goal is for their populations to recover so that they will one day live free, then it is essential that their wildness be preserved — including their innate fear of people.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Three red wolves released into their recovery area in North Carolina last spring were hit by cars and killed within weeks, and a fourth was shot on private land a few months later.

After years of decline, conservation groups and government agencies agree that it’s more crucial than ever to rebuild these populations. The US Fish and Wildlife Service is moving forward with plans to release more wolves in the coming year.

The Endangered Wolf Center, located outside St. Louis, is home to eight canid species, including swift foxes, South American maned wolves, and African painted dogs. I was there to learn about their recovery species, Mexican wolves and American red wolves, and to observe their annual health exams. I joined animal keepers from across the country for training on how to help these critically endangered wolves retain wild traits while they’re living under human care. (The center currently houses 15 red wolves and 28 Mexican wolves.)

Regina Mossotti, the director of animal care and conservation at the center, calls caring for captive wolves while keeping them from becoming habituated to humans “a delicate dance.” To give these animals the best chance of surviving outside captivity, keepers use tools and techniques developed over decades to shape habitats and activities that enrich the wolves’ captive lives, which can include deer carcasses, duck scents, and thorough but speedy health checks.

“Saving animals from extinction is a creative process,” Mossotti explains.

After the workshop, I talked to Mossotti about the difficult balancing act of caring for endangered wolves while also enabling them to remain wild at heart. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Meaghan Mulholland

Is it really possible for wolves to retain their innate wild instincts while living under human care?

Regina Mossotti

People often compare wolves to dogs. Dogs have been domesticated for tens of thousands of years. These wolves we are raising in captivity just left the wild a few decades ago, so they are very wild, still. And we’re doing everything in our power to make sure that those natural instincts are retained.

We wouldn’t have red wolves or Mexican wolves today without these captive programs. We pulled the last few remaining wolves out of the wild [in the 1970s], declaring them functionally extinct. And these last wolves were put in zoological institutions across the country where we started these breeding programs in an effort to save them. The [Mexican and red] wolves that we have in the wild today were released from zoos, and we see them doing everything they’re supposed to be doing: they’re hunting, having puppies, staying away from people, and protecting their territory. Those natural instincts are so strong. That’s what helps make these programs successful.

When the US Fish and Wildlife Service founded these programs, they had to be super creative and come up with ways to raise these animals in zoological settings that also maintained the wolves’ natural behaviors — being shy around humans, for one. Running away from people is such an important survival skill for them. So we had to develop techniques that removed humans from the equation — or, at least, we had to make sure that they didn’t associate humans with positive things.

Meaghan Mulholland

What are some of those techniques for keeping these wolves wild, or ready to be released?

Regina Mossotti

First, we create large habitats for them. Some of the enclosures at our center are half an acre to an acre. This gives the wolves the ability to stay away from people, if they want to. They can hide.

The space also allows them to have multigenerational packs. That’s important because it mimics their behavior in the wild. [In] a multigenerational pack, the litter born the year before gets to help the mom and dad raise the next. They see how to feed, how to protect, how to play with, and how to discipline those puppies — so when they get the chance to start their own family someday, they are awesome leaders that can make sure their puppies are successful and survive.

One of the questions we get asked most is, “How will captive wolves know how to hunt?” They get to hunt anything that goes into their enclosure. Squirrels, possums, raccoons — you name it — some of those animals wander in, and the wolves get to practice their natural hunting skills that way.

We also get deer carcasses donated from trusted hunters, so we’re able to feed [them] natural prey. Even though it’s not alive, they learn the taste of it, and they work together as a pack to eat it. It’s kind of like humans sitting around the family dinner table — it helps bond the pack while they’re eating, and it helps them to know a source of food when they’re released.

We have to be thoughtful about how we can make sure we’re changing their water and giving them food without them seeing us. These animals are so shy that after we quickly put food and water in, it takes them hours afterward to come out and eat it. By the time they’re eating their food, we’re gone. They’re not associating it with people.

Meaghan Mulholland

Are they expecting food at certain times, though?

Regina Mossotti

We really analyze where and when we need to be around our animals, and how we can minimize habituation to humans. One of the ways that we do that is varying when we feed and how we feed, so that it’s not something that they get used to. If you have a dog at home, and you feed him at 6 o’clock, he knows quickly that at 6 o’clock every day, it’s dinner time. Well, wolves will get habituated to that sort of thing, too. If they don’t know when food is coming during the day, it helps alleviate or remove some of that habituation.

Meaghan Mulholland

How else do you prepare these animals for the wild?

Regina Mossotti

One of the most important things that we do is provide enrichment. This just means things that help them use natural behaviors and stimulate their brains. Things that will help them be successful in the wild, whether it is how to eat together as a family — if we’re giving a whole deer carcass, for example — or how to mark their territory, because out in the wild they’d have to mark and protect territory from other wolves. For that we use scents in their enclosures — maybe scents from another pack, or something they might find out in the wild, like lavender or duck.

Caching, or being able to save food, is a really important thing that wolves do when times get tough. It’s very difficult for wolves to hunt out in the wild; they’re actually only successful maybe 10 percent of the time. When they’re lucky enough to get dinner — an elk or deer — it lasts their pack, depending on the size, probably at least a week. Sometimes they are dealing with the fact that they may not get more food for a while, or they may have to hide it from bears or mountain lions who want to steal it. Having large enclosures, they get to practice doing that, too.

We’re also able to help them learn to problem solve. We can find a log that has holes in it, maybe, and put food in it, and they’ll have to figure out how to move the log for the food to fall out. We also help them figure out how to forage — to find food when maybe it’s tough to locate big game that they would normally be hunting.

Meaghan Mulholland

You’re using only natural materials that they would find in the wild, right? Not dog toys or things zoos might otherwise use.

Regina Mossotti

Right. That’s partly why we have to be so creative with enrichment. You go to a pet store and find cool puzzle feeders for your dog — the dog rolls it around, and food drops out. But we can’t use those. We have to come up with ways of doing that kind of stuff with natural elements, whether it’s antlers, deer hides, or trees. And we have to make sure that we don’t use anything that could attract them to where people are, [like] a campsite.

If you have a lion at a zoo, you might use Axe body spray as scent enrichment, something new and unusual. The lions would be intrigued and roll on it and investigate it. We’re not going to use anything like that, because we don’t want to attract the wolves to humans, or for them to associate anything interesting with humans.

Meaghan Mulholland

The center performs yearly health examinations for these animals. What does rounding them up look like?

Regina Mossotti

The animal care staff that goes in to corral these animals are just forming a human wall. That’s how shy wolves are — they just want to be at the opposite end of wherever people are, as far away as possible. We can use that human wall to slowly and calmly urge them into these smaller areas, and then quickly shut a door to seal them in. And then our staff go into that smaller area and gently hold them in place with our equipment. [Editor’s note: A padded, Y-shaped pole is used to apply gentle pressure to the wolf’s shoulders — the wolf submits readily]. We also put a towel over their face — it’s like magic, the towel. They completely calm down.

That’s when we give them their vaccines, and we’re able to draw blood and check that they’re healthy. Then we are able to gently put a muzzle on their face, so we can lift them into a crate. Then we’ll put the crate on a scale, and get the wolf’s weight to make sure they are eating healthily.

And then once we’re finished, we open the door of the crate, and they run out and go back to their family.

We have fine-tuned these techniques over 15 years so that we’re making sure we are doing it as safely as possible. Every single individual is so important for us to save the species from extinction.

It’s maybe five minutes total. But it is so important to their overall care, and to their successfully being released into the wild, because it reinforces that humans — those two-legged things that they might see out in the wild — they want to stay away from them.

Meaghan Mulholland

Some of the most recently released red wolves were killed by vehicle strikes. Is anything being done to condition them to be afraid of cars?

Regina Mossotti

That’s actually something we’re trying to figure out right now. [Recovery partners are thinking about] everything from having reflective collars on the wolves to creating wildlife overpasses or underpasses to cross roads. From the human care side, we’re still evaluating how we can help with that. When we’re doing their annual exams, for example, we do drive up in vehicles, so if they hear cars, it’s associated with people doing something they don’t like.

Meaghan Mulholland

What about wolves that aren’t deemed good candidates for release? Can they still play a role in helping the species survive? By parenting future generations that might live successfully in the wild, for example.

Regina Mossotti

Yes. That happens and it’s amazing. Their family dynamics are so similar to ours, really. It’s so fun to watch, from a distance, the personalities of the puppies as they grow, and see how they interact with their brothers and sisters and mom and dad. They are so nurturing and caring — just the opposite of what we think about them in popular culture.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment