Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Khan, then age 31, soon came across a text that revealed what was going on. “Congrats bro your best friend is getting married!” the message read. “You must be so happy man.”

He could not believe what he had just read.

Khan immediately logged onto Facebook to check the page of his childhood best friend, Ahmed. He quickly realized that Ahmed had unfollowed him and restricted his access to the profile. Meanwhile, the pages of his other friends were congratulating Ahmed on his engagement and the wedding that he had apparently announced for that summer. Ahmed, whose full name is being withheld at Khan’s request and who did not respond to requests for comment, had shared every moment of his life with Khan since they were kids. Yet he had not even told Khan about his engagement.

“I just realized then that he’d cut me off without saying a word. He even unfollowed me on Facebook, on Instagram. I can’t even explain how shattered or humiliated I felt,” Khan said. “People were messaging me from around the world saying they were looking forward to seeing me at his wedding. I didn’t even know how to reply to them.”

Khan lay back in bed, tears stinging his eyes. He had experienced so many small betrayals over the years since his problems with the U.S. government began: acquaintances quietly severing ties, phone calls and messages left unreturned, and even parents of friends telling their children it’s too much trouble to associate with him.

A handsome, athletic young man who had been accustomed to being the center of attention since his high school days, Khan — though he had never even been accused of a crime — was now a pariah. He had plummeted into a downward spiral of depression, anxiety, and sleepless nights. Each friendship lost, or rumor about him overheard, had dealt another blow to his self-esteem. Learning secondhand about his childhood best friend’s marriage, to which he would not be invited, was the worst blow yet.

The slow unraveling of Khan’s personal life had begun almost a decade before, with a sudden visit from the FBI. Khan had been an international student attending Northeastern University in Boston to study business management. In 2011, after graduating, he returned to the U.S. on a visitor visa. While staying with family, he was approached by the FBI with an offer to become a paid informant for the bureau. Khan declined.

After leaving the country a few weeks later, Khan and his legal team believe he was placed on the U.S.’s no-fly list as well as the terrorist watchlist. “I would say that it is very likely that he is on the watchlist,” said Naz Ahmad, a staff attorney at the Creating Law Enforcement Accountability and Responsibility, or CLEAR, project at CUNY School of Law, who has worked on Khan’s case. Proving his place on a secret watchlist, by its very nature, is impossible without government confirmation, but Ahmad said the harassment of Khan’s associates at U.S. ports of entry as well as comments made to his previous attorney by officials pointed strongly to the listing.

Since the day he left the country, Khan has not returned to the U.S., where he once spent every summer with family in Connecticut, graduated from college, and even became a diehard Boston Celtics fan. “I would say that the five years of my life that I spent in Boston were the best years of my life, hands down. I would recommend Boston to anyone,” Khan said. “I’d been coming to the United States in general since I was a kid, visiting Disney World, traveling all over the country. I loved it. The time I spent there made a big influence in making me the person that I am.”

After that fateful FBI visit, many of Khan’s contacts who traveled to the U.S. started to be repeatedly detained at the U.S. border, sometimes for hours. Those stopped included friends and acquaintances in Pakistan, as well as people with whom he was only casually connected on social media. A consistent feature of the stops, something that at least five of Khan’s contacts confirmed, is that they were asked about their relationship with him at the border. The contacts said U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers suggested to them during interrogations that Khan was a dangerous person, a possible terrorist. The officials made it clear that he was the source of their problems at the border.

For many of his friends, the pressure was too much. People whom Khan had known for years started calling him to apologize that they were going to have to unfriend him on social media. At weddings in Karachi, other guests started asking that he be excluded from group photographs. His invitations to events started drying up. Spouses and parents of his friends began telling them that being associated with Khan was not worth the trouble. They even wondered whether, against all indications based on his ordinary life as head of an advertising business in Pakistan, Khan had really done something wrong to warrant all this scrutiny.

“They’re harassing all my friends for hours whenever they travel and made it such that even my best friends didn’t want to talk to me anymore,” Khan said. “It’s like I’m in a virtual prison being on this list. The FBI has all this power over you. They own your life. They’re the gatekeepers of your prison, even though you haven’t done anything wrong to justify being put in there.”

Over the past two decades, since the 9/11 attacks, one of the FBI’s core activities has been recruiting informants. While up-to-date numbers are unavailable, past estimates have put the number of informants working in the country in excess of 15,000. Many of these people are Muslim Americans or immigrants from Muslim-majority countries in the United States. For those who decline an offer to inform, the consequences can be serious.

“There are a number of people who have accused the FBI of putting them on the no-fly list for refusing to be an informant,” said Michael German, a former FBI agent who is now a fellow in the Brennan Center for Justice’s liberty and national security program. “Agents need to have informants, which is why they go on these fishing expeditions. When people refuse, they often become vindictive. They take the attitude that, ‘We gave you a chance to prove yourself on our side and your refusal to aid us means you’re against us.’”

In late 2016, The Intercept reported on a cache of documents provided by an FBI whistleblower revealing how U.S. national security agencies use the immigration system and border crossings as a means of gathering intelligence and recruiting informants. The documents laid out in detail how the FBI and Customs and Border Protection cooperated to target lists of people from countries of interest, with the FBI helping identify individuals for additional screening, questioning, and follow-up visits.

No active investigation or suspicion of criminal activity is needed to make such approaches; the FBI merely has to suggest that the person in question could provide useful intelligence. According to the latest available public documentation, officials can collect information on someone, which is followed by a “nomination” of that person to the lists; the FBI is one of the nominating agencies. Then comes a process, including purported vetting, that frequently lands people on watchlists despite a dearth of hard evidence tying them to terrorism.

One FBI presentation said, as officials also told Khan, that the authorities aren’t looking for “bad guys” to push to become informants, but rather for “good guys.” Individual agents were given broad discretionary power in how they handled such situations. The result, FBI whistleblower Terry Albury recently told the New York Times, was a culture of racism and malice, with agents pressuring individuals into spying on their communities and frequently destroying the lives of innocent people in the process.

“It is very typical to hear about someone pressured to become an informant who refuses and suffers retaliation in the form of being placed on the no-fly list,” said Hina Shamsi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Security Project. “What is worse in this case is that as a noncitizen all of these problems are exacerbated: The already constitutionally inadequate recourse available to citizens and permanent residents placed on the list is not even available to him.”

Khan reeled from the latest blow of not being invited to his best friend’s wedding. Though he cannot prove that he is on a watchlist, let alone know who put him there, Khan could not help but think that his life had been destroyed over a decision taken at a whim by an FBI agent he had met years ago, whose offer to become an informant he had turned down. Khan had no way to clear his name or fix his shattered reputation. To this day, he has never been accused of any wrongdoing.

“I’ve lived a clean life and never got into any kind of trouble at all anywhere in the world. This really affected me. I love America, and I loved every part of my life there. Even today I wish I could go watch the Celtics at TD Garden, see my old college, and go visit my friends and family,” he said. “No one has ever even accused me of doing anything, so I can’t see where the justice is in any of this. It feels like one guy in the FBI just decided that he was going to ruin my life for no reason.”

On the morning of February 9, 2012, Khan, then 26, woke up to the sound of banging on the front door of his aunt’s house in New Britain, Connecticut. His aunt, uncle, and cousins had gone out for the day, leaving him home by himself. He was in the United States on a visitor visa, having arrived the previous October, and was nearing the end of his allotted six-month stay. As the banging on the front door continued, Khan’s cellphone rang with the number of his cousin displayed on the caller ID. Thinking that it was her at the door and that perhaps she had forgotten something on the way to work, he picked up the phone. “Hey, should I come open the door?”

“This is not your cousin,” a man’s voice curtly replied. “This is the FBI. Come to the door now and do not hang up the phone.”

Khan’s heart immediately began racing. He had no idea why the FBI would be showing up at his front door or how they could spoof his family’s phone numbers to contact him. He went downstairs holding the phone as instructed, while the officers continued aggressively banging on the door. When he opened it, two men in suits were standing there waiting for him. They showed him their badges, one from the FBI and another of a Connecticut State Police detective. The officers were Andrew Klopfer, the FBI agent, and then-CSP Detective Andrew Burke, according to Khan and an email from one of his attorneys confirming his recollection of the men’s names.

Khan, trying his best to suppress his terror over this sudden visit, tried to clarify what was going on. His lanky 6-foot-3 frame filled out most of the doorway, the side of which he gripped as he spoke to the officers.

“I asked how I could help them, and they said that they just wanted to speak to me. Then they said that they needed to take me to another location so that we can talk and that it’s for my own security, as well as their security,” Khan said. “I asked if I needed a lawyer or something and they told me that wouldn’t be necessary. By this point I was already so nervous and scared, I was shaking. I was just trying to figure out why these guys were here and looking for me.”

The officers told Khan that they were going to take him to a local diner in town so that they could have breakfast and talk. Still wearing his pajamas, he asked if he could change. After refusing initially, the officers relented, following him into the house and waiting on the bottom floor while he went upstairs. Khan then followed them out to their car.

“They put me in the front seat. First thing they said to me was that I’m a really tall guy and that they didn’t think I’d be this tall,” Khan said. “They said that people had been watching me for the past week and that cars had been tailgating me and asked if I’d noticed. I told them I hadn’t.”

The officers drove Khan about 15 minutes to a local diner. After sitting him down in a booth, they told him to order something for breakfast. Still terrified and struggling to comprehend the surreal turn his morning had taken, Khan ordered a glass of juice and an omelette. The officers, who ordered themselves breakfast as well, peppered him with questions about what he did in Pakistan, why he was visiting the United States, where he went to college, and what his family’s financial situation was like.

After about 20 minutes, Klopfer, the FBI agent, got to the point of the encounter: They wanted Khan to work for them.

“They said they want me to do work and provide them information, and it could be either in the U.S. or in Pakistan. I asked them what the job was that they were specifically describing here, and they said directly that they wanted me to be an informant and spy on mosques in the U.S. or in Pakistan,” Khan said. “At this time, I didn’t even know exactly what ‘informant’ meant, so I asked them. They told me that it meant being on the side of the good guys, referring to themselves, and going in and getting information for them.”

Khan had come from a relatively well-off family in Pakistan who had paid for him to be educated in the United States. He told the officers that he did not need a job. He wouldn’t be well-suited for it anyways, he added, describing himself as loud, sociable, and not the type of person who could keep dark secrets to himself. The officers said the FBI could provide him with U.S. citizenship, money, and other perks; they promised that whoever worked for them would become a powerful person with connections that would make them “untouchable.” (The FBI declined to comment for this story or to make Klopfer available to answer questions. Neither Burke nor the Connecticut State Police responded to a request for comment.)

At one point, the officers reminded him that the government was paying for his juice and omelette. By now, however, with the purpose of the meeting clear, Khan was only focused on getting home as soon as possible and finding help.

“I told them it’s not a big deal. ‘OK, it’s 10 bucks. I’ll pay for it. I’ll even pay for your meal,’” Khan said. “The only thing on my mind at that point was thinking how to get out of this situation and getting home to tell my aunt what the hell is going on right now.”

Although he wanted U.S. citizenship — offering him the chance to spend more time in a country he loved, with family and friends — the idea of becoming an informant was out of the question. Even though he did not attend mosque regularly, he did not want to be sent by the FBI to spy on people at prayers. The officers continued to make offers, and Khan kept rebuffing them.

“I told them, ‘I respect you and what you do. You put your lives at risk to protect us and the people of the United States, but I’m not one of those people who is cut out to be a spy or is interested in the kinds of things you’re offering me,’” Khan recalled. “I said, ‘I have a clean record and lived here for years without ever doing anything wrong.’ They told me, ‘That’s why we want you.’ They said, ‘We don’t go after troublemakers, we want the good guys to work for us.’”

Seeing that their efforts to entice him by offering immigration help and money were getting nowhere, the officers soon began taking a different tack. They asked him the names of several terrorist organizations based in Pakistan: Did he know these groups? The organizations were mainly based in Pakistan’s tribal regions, far from Khan’s urban hometown of Karachi, and he told them he had never met anyone who had connections to the groups.

After about two hours of tense conversation, the officers put Khan back in the car and drove him home. Wracked with anxiety, he had been unable to take a single bite of his food. Now he was just glad that this frightening ordeal was about to be over. Before leaving, Khan said, Klopfer gave strict instructions not to tell anyone about the meeting, not his family and especially not a lawyer. They said they would be in touch again soon.

As soon as the officers drove away, Khan immediately dialed his aunt to tell her what had happened: that the FBI had picked him up at home, that they were offering him money and perks to work for them as an informant, and that he was scared. She and his cousin rushed home from work and called a lawyer in Bridgeport to set up an appointment for later that day. When they arrived, the lawyer, Christian Young, took the numbers of the FBI and Connecticut State Police officers who had picked Khan up. Young called the officials and told them not to contact Khan again without calling him first.

A week later, according to Khan, Klopfer called Young and said that he wanted to interview Khan again before a federal prosecutor. Young advised Khan to take the meeting and said that he would be there with him to make sure it went smoothly, Khan said. (Young declined to comment for this story.) The interview was scheduled for just over a week later. Wanting to make a confident impression, unlike the last meeting in which the officers had showed up at his house in the early morning unannounced, Khan came wearing a suit and tie.

“By this time, I already knew that Andrew Klopfer was pissed off at me,” Khan said, noting that the FBI agent was much more standoffish than their first meeting. “I did exactly what he didn’t want me to do by telling my aunt and getting a lawyer. I was no good to them anymore for what they had wanted me to do.”

For about two-and-a-half hours, Klopfer, Burke, Khan, and his lawyer sat with then-Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephen B. Reynolds in a boardroom at the FBI office in Bridgeport. In the presence of Reynolds, whose identity Khan and an attorney later working on the case confirmed, the officers asked Khan all the same questions about his life and background that they had asked at the diner. (The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Connecticut declined to comment. Neither Reynolds nor the Department of Justice responded to requests for comment.)

A description of this meeting, which also referenced Khan’s previous meeting with the FBI at the diner, was obtained years later as part of a Freedom of Information Act request submitted by Ahmad, the attorney with CLEAR. The document describes Khan’s views as expressed at the meeting about a variety of issues, including details of his life as a student in the United States, relationships with family members, and future career plans, as well as his political views.

Any references to terrorism or offers to work as an informant are either not in the documents or concealed by the many redactions, which the FOIA response says were made because the underlying material “would disclose techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigation.” According to Khan, the redactions correlate with those parts of the conversation when the officers switched from mundane questions about life and politics to asking him about specific terrorist groups and attacks. When the officers began to take this line of questioning, Khan turned to Reynolds and addressed him directly.

“I told him that my parents had spent a lot of money to educate me in America and I’d loved it here. I’d never got into a fight or had a DUI or had any debts. I’d been a law-abiding citizen and didn’t want any trouble with you guys. But it seems like if I wasn’t brown, Pakistani, and Muslim, I wouldn’t be here,” Khan said. “The U.S. attorney said it’s not like that and that this is not a racist situation. He said there are always broader circumstances to be aware of and that we have a right to ask you questions about terrorists for security purposes.”

Khan told Reynolds that he needed to pay a visit to the hospital to see his ailing uncle later in the day. Reynolds announced that Khan was free to leave and wished his uncle a speedy recovery. Leaving the office, Khan noticed that neither Klopfer nor Burke said anything to him or made eye contact on the way out.

For a moment, it seemed like his problems were done with. Khan still had a few weeks left on his current six-month trip to the U.S. His lawyer told him to stay until the last day, to underline that he had done nothing wrong and was not fleeing. Khan took his advice and spent the remaining weeks with family and friends. With time, the frightening morning visit from the FBI began to fade in his mind.

A month later, at the boarding area of John F. Kennedy International Airport, in New York, Khan got an SSSS — short for “secondary security screening selection” — flag on his boarding pass for the first time in his life. He received a bit of extra scrutiny at the security checkpoint, but otherwise things seemed normal. He boarded his flight back to Pakistan with his mind clear, already making plans in his head for his next visit.

That moment at Kennedy Airport, in early April 2012, would be the last time Khan ever set foot in the U.S. Unbeknownst to him, it was also the beginning of a dark new chapter in his life: From that moment on, his reputation, his social life, and the promise of his future would begin to unravel.

For Khan — and his circles — the trouble began almost immediately after he arrived back in Pakistan, weeks after his last meeting with the FBI and assistant U.S. attorney. Though, because of the secrecy of the process, Khan has no evidence that Klopfer, Burke, or anyone else put him on a watchlist, his friends started having problems at the U.S. border and Khan’s name kept coming up. In May 2012, a childhood friend, Faisal Munshi, a dual Pakistani-Canadian citizen, was pulled aside at the U.S. border and questioned about Khan.

The owner of a large food supply business and holder of the Pakistani franchise rights to a multinational pizza chain, Munshi was headed to the U.S. from Toronto to attend the company’s biennial conference in Las Vegas. “All the franchisees from across the world go there, and I was planning to attend as I always did,” Munshi said.

He was interrogated for hours about Khan, including questions about a plane ticket he had bought him while they were college students in 2007.

“They told me that they knew I had bought this guy Aswad Khan a ticket to come see [me] in Toronto three or four years ago, and I told them that, yes, it was true I bought him a ticket with my air miles because he was my childhood friend and a bunch of us were going to gather to hang out over spring break,” Munshi said.

After several hours of questioning by CBP agents, he was told that authorities were denying him entry into the U.S. CBP agents told Munshi that he could raise his objections with the Traveler Redress Inquiry Program, an administrative mechanism operated by the Department of Homeland Security for people experiencing difficulties traveling to clarify their status. When Munshi wrote in, he received an inconclusive message that neither confirmed nor denied his presence on any list.

A year later, Munshi tried to attend another company conference in the U.S., this time with plans to fly in from Dubai. The attempt ended in failure again, with Munshi being told by officials in the Dubai airport’s departures lounge that he had not been cleared to fly onward.

Increasingly concerned about these ominous restrictions on his movement, Munshi, who is married to an American citizen and has traveled to the U.S. regularly throughout his life, returned to Canada and sought out legal advice. A lawyer suggested that he try crossing at a land border next time. In 2014, two years after his first denial of entry into the U.S., Munshi drove to a border crossing at Buffalo, New York, in the hopes of being admitted to attend his sister in-law’s college graduation. This is when his situation became much more alarming.

“Driving to Buffalo and being detained there was the worst experience of my life,” Munshi said. “I could not believe how I was treated, with the assumption that I was a criminal. They kept me for six hours, shuffling me around into different rooms, one of them where they left me to freeze for an extended time, and separated from my parents. I met one immigration officer after another, and whenever I asked what the problem was, they’d just tell me it was above their pay grade.”

Thinking that it might help to underline that he was an ordinary person who posed no threat, Munshi had brought a letter from the U.S. corporate headquarters of his U.S.-based corporate parent confirming his identity and role as the head of the ubiquitous pizza shop’s Pakistan operations.

“The border agents asked me why I had been trying to come into the United States, and I told them that I had family there and also run a big business in Pakistan headquartered in the U.S., and I frequently need to attend conferences and meetings,” Munshi said. “They then asked me if I use the income from this business to finance terrorism. I told them I obviously don’t. I come from a good family and that they can look me up online themselves to see my background.”

After several hours, Munshi was informed by border agents that he had been denied entry again. The officials provided no reason and made no specific allegations against him over six hours of questioning. The only clue he had to why he had suddenly become unwelcome in the U.S., a country that he been traveling to his whole life, was the question he had received during that first interview: the airline ticket he had bought for his friend Aswad Khan.

Munshi was not alone. Another childhood friend of Khan, a Pakistani citizen married to a Canadian, was also detained at the U.S. border and questioned about Khan on multiple occasions since 2012. Like several others who spoke to The Intercept who had the same experience, he asked for anonymity for fear of reprisals.

“One time, when I landed at Chicago airport around the start of 2017, there were two agents waiting at the passport area who approached and told me they’d been waiting for me,” Y. told The Intercept. “They took me to an interrogation area and showed me a picture of Aswad that they’d printed.”

CBP agents questioned Y. for several hours along with his wife. Officials asked about his friendship with Khan, how Khan earned a living, and what he used his income for. “I told the agents that they’re making a mistake with these questions about Aswad and that they had the wrong guy,” Y. said. “They told me that they’re going to ask whatever questions they wanted. Then they said point-blank in front of my wife that if they’re asking these types of questions about Aswad, that means he’s a person I shouldn’t be associating myself with.”

Like several others who spoke to The Intercept, Y., who travels frequently to the U.S. for work, deleted Khan’s contact off his phone and his social media accounts. He called Khan to apologize at the time, saying that he was shaken by the harassment he had begun facing. The experience put a strain on their friendship, though, unlike many others, Y. had at least talked to Khan about it.

In his community in Karachi, rumors were spreading well beyond his close friends that being in any way connected with Khan was a certain route to getting in trouble at the U.S. border.

“People gossip and eventually it came to a point where a lot of people would not even want to meet Aswad,” said Munshi. “They started thinking that maybe he really did do something wrong, and that’s why he had these problems with the U.S. government. They started thinking that maybe it was because of him that his friends and other people he knew were starting to have the same problems too. People started deleting him off Facebook. They were afraid to even be associated with him.”

In Khan’s mind everything went back to his encounter with the FBI. Ever since then, more than a dozen of his friends told him about serious problems when traveling to the U.S., including questions about him and even statements from CBP agents telling people to keep their distance from Khan if they wanted to avoid trouble. Others never told Khan about any troubles but instead disappeared from his life without a word. Khan began noticing friends and acquaintances were removing their Facebook and Instagram connections to him. His phone calls and text messages went unanswered. Invitations to weddings and parties began to dry up. For a young man known throughout his life as a social butterfly, it felt like the world was caving in.

In 2018, Khan, still struggling to figure out how to clear his name, filed paperwork with the Department of Homeland Security’s redress program. Like Munshi, his friend, the written response from the agency he received in July of that year was vague, stating that the agency “can neither confirm nor deny any information about you which may be within federal watchlists.” He had run up against one of the limits governing noncitizens and nonresidents who seek information about their watchlisting: The government does not even have to confirm whether he is on the no-fly list, let alone what is justifying keeping him there.

“What is very frustrating is that they have found a way to make his life miserable from thousands of miles away 10 years after they met him,” said Ahmad, the staff attorney at CLEAR. “It should be very obvious from all the information that they’ve gathered at this point that he’s not a threat. Yet they continue to target him, and he has very little legal recourse to defend against that.”

Slowly but surely, Khan’s reputation was destroyed by scrutiny from U.S. authorities, particularly by what he and his attorneys believe is his placement on the terror watchlist. He did not face any harassment or scrutiny from the Pakistani government at home, yet because of the U.S. government’s harassment of his friends and acquaintances, he now lived under a cloud of suspicion.

“Friends I had my whole life started ghosting me over these rumors that started from people who had been questioned at the U.S. border,” Khan said. “I became depressed, I felt like I had no way out of this. I started questioning my existence, I looked to God for help. I felt like for no reason the FBI just took everything away from me.”

The issue of reputational harm has come up in previous lawsuits that targeted the watchlisting system, though the courts have so far upheld the practice as constitutional. An article this June in the national security law publication Lawfare about one such case put it, “[W]hile the Supreme Court has recognized a liberty interest in a person’s reputation, reputational injuries must involve a combination of factors: a statement that stigmatizes the plaintiff in the community and has been publicly disseminated, and the government must take some additional action that has altered or extinguished the plaintiff’s legal rights.”

The secrecy of the watchlists means that the reputationally damaging information about would-be claimants — the very fact that they are on a list — has been ruled by courts to not count as having been publicly disseminated. And yet the reputational damage is real. It is the ruin of his name and his friendships that continues to torment Khan.

“Aswad had graduated from college and was looking for a job at the time this happened, and it really affected his personal life,” said Ahmad, the CLEAR attorney. “Losing your friends, not even being invited to your best friend’s wedding — it’s a harm you can’t really quantify. That’s something that people don’t really appreciate: how what the government does can really affect people’s personal lives.”

The government’s terrorist watchlisting system remains opaque. The most consequential revelation to date was a 2014 leak, published by The Intercept, about its size and characteristics. Disclosures in a lawsuit from 2017 established that the watchlist had grown to 1.2 million people, the vast majority of whom were neither U.S. citizens nor permanent residents. Being placed on the watchlist can have any number of effects on a person, such as preventing them from traveling to suffering abuse and detention in foreign countries. Khan believes his placement on the list caused him to be personally ruined by suspicions of association with terrorism.

“People get put on these lists and just get left there. There is no pressure to take them off; in fact there is pressure to not take them off in case one day in the future they possibly do something,” said German, the former FBI agent. “It’s easy enough to put someone on a watchlist and forget about it. The fact that it has continuing impact on a person’s life is meaningless to them.”

Khan is still in Pakistan. His past life of frequent visits to the U.S. and elsewhere are now a distant memory. Though he used to enjoy traveling, he has only left Pakistan once since his encounter with the FBI. He has not attempted to return to the U.S. since his last trip, for fear of what might happen when confronted by U.S. authorities. The experience of boarding an international flight and confronting the possibility of a border crossing anywhere in the world fills him with anxiety. Unaware what type of rumors have been spread about him by the U.S. government with foreign authorities, let alone people in his own life, he has become wracked by depression and paranoia. Nearly a decade after his fateful morning visit from the FBI, his life has not returned to normal.

A year after Ahmed’s wedding ceremony in Italy, which he did not attend, Khan ran into his childhood best friend at a party in Karachi. The two had not spoken or seen each other for nearly two years. In the meantime, Khan had heard from others that Ahmed had told some friends that he had felt pressured to sever their friendship because “the U.S. government is after him,” and that his absence at his wedding was to protect the other guests from the possible consequences of being associated with him.

When the two saw each other at that party, Ahmed took him aside to talk. After a few moments, Ahmed broke down and cried.

“He said he didn’t want any bad feelings with me, and that when I had gotten into trouble, he just got scared. It was a hard conversation for us to have,” Khan said. “I had never felt hurt in my life like I had when he cut me off without saying a word. But I told him it was OK. It is what it is.”

“‘You believed what they said about me, and you got scared. I get it. You thought I was a terrorist.’”

Abortion rights supporters and opponents debate outside the Supreme Court on Wednesday. (photo: Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Abortion rights supporters and opponents debate outside the Supreme Court on Wednesday. (photo: Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Few senators as of yet are fully endorsing ideas like mandatory retirement for the justices or expanding the number of seats on the nine-person court. But a growing faction, long hesitant to embrace structural changes, say they are now prepared to consider such moves.

That sentiment is growing among Democratic senators, according to interviews with more than a third of the 50-member caucus Thursday, even as President Biden has shown little indication that his resistance to overhauling the Supreme Court has softened.

Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) said many Democratic senators have been reluctant to entertain proposals about changing the Supreme Court in the past because “we do respect the separation of powers under the Constitution.”

But Wednesday’s oral arguments, in a case involving a Mississippi law that would bar most abortions after 15 weeks, changed those sentiments, he said. “It is hard to watch that — and I did watch a fair amount of it — and not conclude that the court has become a partisan institution,” Schatz said. “And so the question becomes, well, what do we do about it? I’m not sure. But I don’t think the answer is nothing.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) made a similar point. “What happened yesterday forces all of us to rethink our views about the makeup of the court,” she said. Referring to justices who appeared prepared to overturn precedent and scale back abortion rights, Warren added, “They‘ve undermined confidence in the court and force us in Congress to rethink how to build a court that the American people can trust.”

In one sense, elected officials are starting to catch up to the progressive Democratic base which, in recent years, has loudly advocated for overhauling the structure of the Supreme Court. These rank-and-file Democrats have been motivated largely by anger against Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), whose maneuvering the last four years successfully installed three conservative justices, two of whom replaced Justices Anthony M. Kennedy and the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who were favorable to abortion rights.

When Justice Antonin Scalia died in February 2016, McConnell, then majority leader, took the unprecedented step of refusing to consider President Barack Obama’s nominee, holding the seat open until President Donald Trump could fill it upon taking office with Justice Neil M. Gorsuch.

And when Ginsburg died shortly before Trump’s term ended, McConnell changed tactics and pushed through Justice Amy Coney Barrett with unusual speed. Those two justices — along with Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh — have cemented a conservative majority that now appears poised to significantly cut back abortion rights.

Republicans contend that Democrats are threatening to overhaul the high court solely because they dislike its opinions, calling that a dangerous attack on judicial independence. They dismiss complaints that anything was wrong with the recent confirmations, saying that is sour grapes by Democrats because events have not gone their way.

Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), responding earlier this year to a Democratic bill to expand the court, tweeted that “packing the court is an act of arrogant lawlessness” and added, “Those behind this effort spit in the face of judicial independence.”

Democrats are driven in part by what they see as contradictions between what Supreme Court nominees tell senators during their confirmation hearings and their actions on the bench once they have secured a lifetime appointment.

A particular point of contention this week was comments from Kavanaugh, who said pointedly during the oral argument that the Supreme Court had overturned long-standing precedents in the past, including in Brown vs. the Board of Education, which found that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional.

For Democrats, that was at odds with his tone during his bruising confirmation fight in the Senate three years ago, when he assured senators that he believed Roe vs. Wade, the landmark 1973 case that established a constitutional right to an abortion, was settled law.

“Kavanaugh’s cavalier talk yesterday about precedent, and the clear political motivations of the plaintiffs in this case, are going to undermine faith in the judiciary,” Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) said. “We’ve got to think about ways to sort of depoliticize the courts. And one of the ways to do that is to make sure that no one president gets to stack the bench.”

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) said lawmakers should seriously consider term limits or mandatory retirement for the justices. Some other courts, Blumenthal noted, have similar restrictions for their judges.

Other Democratic senators pointed to judicial ethics as one area of particular concern, noting that justices essentially police themselves and face no accountability to the public for their actions.

“I’m not ready to say we need to change the number of justices,” Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.) said. “But I do think this is a different era. And we need to take a look at how the court functions.”

There remains, however, a massive gulf between a fulsome debate about structural changes to the Supreme Court and actual enactment of such ideas.

For one thing, the Senate would almost certainly need to dismantle the filibuster — which requires a 60-vote threshold for most legislation to advance — to push through revisions. And experts say it’s an open question whether term limits for justices can be imposed through legislation or would require a constitutional amendment.

“Even if you could do term limits, if you could do it tomorrow, it doesn’t help pregnant people in Texas right now, or in Mississippi or across the country. It doesn’t help Black voters in Georgia,” said Christopher Kang, co-founder and chief counsel of Demand Justice, a liberal advocacy group that focuses on the judiciary. “The only thing that is actually going to provide balance to the court and do something in the near term is Supreme Court expansion.”

During the 2020 presidential campaign, several Democratic candidates, though not Biden, embraced the notion of expanding the court. That marked a notable shift of opinion on “court-packing,” which long had a negative connotation stemming from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s failed 1937 effort to add as many as six justices.

Candidate Pete Buttigieg, now secretary of transportation, suggested increasing the number of justices to 15 — five selected by Democrats, five by Republicans and five chosen by the other 10.

In response to such calls for change, Biden, who has made his reservations about them clear, assembled a commission shortly after taking office that is tasked with reviewing various proposals. It meets again next week and will prepare a final report to Biden later this month.

“If you look at the history of the Supreme Court, it was important to the president to have a range of viewpoints that he could look at and assess and look at the historic nature of a lot of these issues,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said.

Perhaps the most controversial of the proposed Supreme Court changes is increasing the number of justices. Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) and other Democrats introduced a bill in April to expand the size of the Supreme Court to 13 justices.

Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), a former executive at Planned Parenthood in Minnesota, endorsed Markey’s bill in September. She said she was motivated to embrace changes to the Supreme Court partly by its decision earlier this year to keep intact a restrictive new abortion law in Texas.

“Yesterday, we saw the court is politicized. The question is, what are we going to do about it?” Smith said Thursday. “Are we going to take action to rebalance the court, or are we just going to sort of bury our heads in the sand and pretend that it hasn’t happened?”

Still, senators appear more likely to consider term limits rather than court expansion. That broadly reflects public sentiment; a Marquette Law School poll from November found that 48 percent of American supported increasing the number of justices on the Supreme Court, while 52 percent were opposed.

In contrast, 72 percent favored fixed terms for Supreme Court justices, rather than lifetime appointments, compared with 27 percent of adults who opposed them.

Not all Democratic senators interviewed Thursday embraced the idea of far-reaching changes to the Supreme Court.

Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Christopher A. Coons (D-Del.), both members of the Judiciary Committee, either deferred to the ongoing review by Biden’s commission or said discussions of changes to the court would have to wait until the impact of this term’s decisions were evaluated.

Others oppose the proposed changes outright.

Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) emphasized Thursday that he did not support enlarging the Supreme Court but said he has not considered other options, such as term limits for justices. But Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.) said flatly that he did not support changes such as term limits or mandatory retirement for justices.

“Where does this stuff stop, okay?” Tester said. “I just think mandatory retirement gets into a bigger problem.”

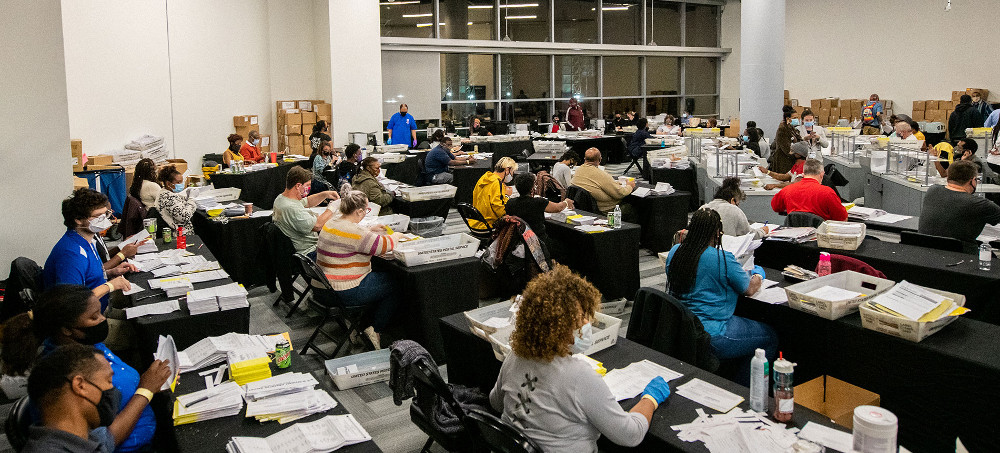

Employees of the Fulton County Board of Registration and Elections, processing ballots in Atlanta, November 4, 2020. (photo: Brandon Bell/Reuters)

Employees of the Fulton County Board of Registration and Elections, processing ballots in Atlanta, November 4, 2020. (photo: Brandon Bell/Reuters)

Desperate to overturn his election loss, Donald Trump and his team spun a sprawling voter-fraud fiction, casting two rank-and-file election workers, a mother and her daughter, as the main villains. The women endured months of death threats and racist taunts – and one went into hiding.

At its center were two masterminds: a clerical worker in a county election office, and her mom, who had taken a temporary job to help count ballots. The alleged plot: Wandrea “Shaye” Moss and mother Ruby Freeman cheated Trump by pulling fake ballots from suitcases hidden under tables at a ballot-counting center. In early December, the campaign began raining down allegations on the two Black women.

Trump’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, falsely claimed that video footage showed the women engaging in “surreptitious illegal activity” and acting suspiciously, like drug dealers “passing out dope.” In early January, Trump himself singled out Freeman, by name, 18 times in a now-famous call in which he pressed Georgia officials to alter the state’s results. He called the 62-year-old temp worker a “professional vote scammer,” a “hustler” and a “known political operative” who “stuffed the ballot boxes.”

Freeman made a series of 911 emergency calls in the days after she was publicly identified in early December by the president’s camp. In a Dec. 4 call, she told the dispatcher she’d gotten a flood of “threats and phone calls and racial slurs,” adding: “It’s scary because they’re saying stuff like, ‘We’re coming to get you. We are coming to get you.’”

Two days later, a panicked Freeman called 911 again, after hearing loud banging on her door just before 10 p.m. Strangers had come the night before, too. She begged the dispatcher for assistance. “Lord Jesus, where’s the police?” she asked, according to the recording, obtained by Reuters in a records request. “I don’t know who keeps coming to my door.”

“Please help me.”

Freeman quit her temporary election gig. Moss took time off amid the tumult. The 37-year-old election worker, known for her distinctive blonde braids, changed her appearance. Moss often avoided going out in public after her phone number was widely circulated online. Trump supporters threatened Moss’s teenage son by phone in tirades laced with racial slurs, said her supervisor, Fulton County Elections Director Richard Barron.

Freeman and Moss did not grant interviews for this report. This account of the campaign against them – including previously unreported details of their ordeal – is based on interviews with Barron, another colleague and a person with direct knowledge of their ordeal, along with an examination of police reports, state records, 911 call records, internal county emails and social media posts. Reuters also reviewed the video footage that Trump and his allies used to attack Freeman and Moss and hours of testimony by the former president’s surrogates at state hearings.

The threats hurled at Freeman and Moss are part of a broader campaign of fear against election administrators that has been chronicled by Reuters this year. Previous reports detailed how Trump supporters, inspired by his false stolen-election claims, have terrorized election officials and workers in battleground states. In all, Reuters has documented more than 800 intimidating messages to election officials in 14 states, including about 100 that could warrant prosecution, according to legal experts.

The story of Moss and Freeman shows how some of the top members of the Trump camp – including the incumbent president himself – conducted an intensive effort to publicly demonize individual election workers in the pursuit of overturning the election.

Some of these targets – including the top election officials in Georgia, Pennsylvania and Arizona – are notable political figures in their states. Others, like Moss and Freeman, have been rank-and-file workers. Moss’s full-time job pays about $36,000 a year. Freeman’s temp gig paid $16 an hour.

Their modest incomes left the two women with little power to defend themselves against the billionaire president and his legions of backers. After Freeman went into hiding, she initially stayed with friends. They soon asked her to leave, fearing for their own security, so she moved from one Airbnb to another, never staying in one place for too long, said a person with direct knowledge of her movements. Freeman went to great lengths to conceal her identity and location, the person said. She stopped using credit cards and started using a system for electronic money transfers that caters to people wanting to keep a low profile, the person said.

The constant threats so terrified the two women that they did not return calls from Fulton County District Attorney’s Office investigators who wanted to talk to them this summer as part of their probe into whether Trump illegally interfered with Georgia’s 2020 election, Barron said. “They wouldn’t even answer the phone,” he said.

No arrests have been made in connection with the threats against the women, and almost no one has been held accountable for threatening election workers nationwide, as Reuters reported on Sept. 8. After the news organization reported the continuing harassment of election officials and their families in June, the U.S. Department of Justice launched a task force to investigate threats to election workers. It has said it takes all threats of violence seriously.

The threats against the mother and daughter followed a hearing of Georgia lawmakers on Dec. 3, 2020, where the Trump campaign falsely claimed that a surveillance video from a ballot-processing room at State Farm Arena in Atlanta amounted to “shocking” evidence of “fraud.” A volunteer Trump campaign attorney, Jacki Pick, said two unnamed Fulton County election workers had engaged in maneuvers involving "suitcases" of ballots pulled out from under a table and illegally counted through the night. She identified them as the “lady with the blonde braids” – Moss – and an “older” woman with the “name of Ruby” on her shirt – Freeman.

In a statement, Pick defended her presentation. “There was nothing normal about what the video showed,” she said.

Giuliani, who spearheaded Trump’s effort to overturn the election results, appeared at another hearing with Georgia lawmakers the next week, on Dec. 10. He showed snippets of the video and repeatedly identified Moss and Freeman by name, calling them “crooks” who “obviously” stole votes.

But the full video revealed the women were legally counting ballots, a state investigation found.

“I will go to my grave knowing that Rudy Giuliani looked the state senators in the eye and just flat-out lied,” said Gabriel Sterling, a senior Georgia election official and a Republican, in an interview with Reuters.

Trump and Giuliani did not respond to comment requests.

Some conservative media outlets covered the false story as fact, giving it credibility among millions of Trump supporters. The Gateway Pundit, a far-right website known for promoting conspiracy theories, cast Freeman and Moss as “crooked” operatives who counted “illegal ballots from a suitcase stashed under a table!” Other Republican officials reinforced the Trump team’s message.

“Caught on candid camera,” tweeted Congressman Jody Hice, a Georgia Republican. “Say it with me... F R A U D.”

Hice did not respond to requests for comment. The Gateway Pundit declined to comment.

As the Trump camp spread falsehoods about the two women, Freeman told police her phone wouldn’t stop ringing with menacing messages. By Dec. 4, she had received about “300 emails, 75 text messages, a large amount of phone calls and multiple Facebook posts,” according to a police incident report.

And people kept coming to her house, she told a 911 dispatcher on Dec. 6.

“Somebody was banging on my door, and now somebody is banging on the door again,” she said.

Facts and falsehoods

Before the Trump team upended her life, Moss had loved her job, colleagues say. She began working at the Fulton County Elections Office as a temporary worker. After several years, she was offered a full-time job in 2017. She cried when she got the promotion, Barron recalled. Four years later, the official county letter offering her the position remains pinned to her cubicle wall.

As a registration officer, Moss handles voter applications, including those for absentee ballots, and helps process the actual votes on election day, in addition to other clerical duties such as working in the mail room. Her data-entry work, Barron said, may be “the fastest in Georgia.”

Her mother, Freeman, had also worked in local government, as a staff member at a center that coordinated 911 emergency calls for Fulton, a county of one million people that includes Atlanta. After retiring, she started a small boutique business selling fashion accessories.

Heading into the election, Fulton County had been hit hard by COVID-19. Many election staff were sick. One died. The first big test, a June primary election, went off poorly, marred by long lines and malfunctioning voting machines. Moss asked her mother if she could help with November’s election. Freeman signed up as a temp.

Election Day – Nov. 3, 2020 – got off to a difficult start. Moss arrived at Atlanta’s State Farm Arena before dawn. The floors were drenched from a ceiling leak in the space where mail-in ballots were processed. The leak was fixed by about 8:30 a.m., causing a brief delay in the count.

Though minor, the mishap made national headlines. Georgia’s biggest and most heavily Democratic county was a crucial battleground for Democrats hoping to flip the traditionally red state. Before the vote, Trump had been insisting that a winner be declared on Election Day. He aimed to cast doubt on the validity of absentee ballots, which are often tallied late and were widely expected to favor Democrat Joe Biden. News of the leak-related delay added tension to the closely watched Georgia race.

By about 10 p.m. that night, workers had been on the job for nearly 18 hours. Ralph Jones, the voter-registration chief, told some staff they could go home to get rest, he said, halting the scanning of uncounted ballots for the night. Most packed up and left. Some news reporters and election observers, who monitor vote-counting for both political parties, did the same.

Just a few workers remained, including Moss and Freeman. The arena’s surveillance footage showed them sealing and packing the remaining absentee ballots in black plastic boxes for storage overnight, a standard security measure against tampering.

The close election and national spotlight added urgency to the counting. Brad Raffensperger, the Republican secretary of state, criticized Fulton County on TV for pausing the processing of ballots when many other counties had already finished. Chris Harvey, the state elections director at the time, called Barron, urging him to keep going, Sterling said.

At about 11 p.m., Barron phoned registration chief Jones and told him to resume counting, Barron said. Moss walked over to a table draped with black cloth, leaned down and pulled out the containers of mail-in ballots her team had sealed up about an hour earlier. Workers unpacked them and counted votes into the night under the watch of an independent monitor and a state investigator, according to state and county officials and a Reuters review of the surveillance video.

For the next month, Trump and his supporters attacked the legitimacy of the state’s election, which Biden won by 11,779 votes.

On Dec 3, Georgia’s Republican lawmakers held their first hearings on “election integrity.” That morning, Trump went on Twitter to tout a live broadcast of the hearings by far-right news channel One America News Network. “Georgia hearings now on @OANN. Amazing!” he told his 88 million followers in a tweet at 11:09 a.m.

At a little past 1 p.m., Pick, the volunteer Trump campaign attorney, told the lawmakers she had “evidence” of “fraud” – excerpts of footage from the arena’s surveillance video, which she showed at the hearing. Pick, a Republican donor, said a “lady with the blonde braids,” referring to Moss, had told the media and Republican observers to leave. Once those people were “cleared out,” Pick said, the same woman pulled out “suitcases” of ballots hidden under a black table.

“So what are these ballots doing there separate from all the other ballots?” Pick asked. “And why are they only counting them whenever the place is cleared out with no witnesses?” She said the site’s “multiple” scanning machines could have allowed workers to process enough ballots to account for Biden’s margin of victory.

As Pick spoke, a Trump legal adviser, Jenna Ellis, tweeted about the “SHOCKING...VIDEO EVIDENCE” being presented at the hearing, declaring a “FRAUD!!!” Minutes later, the Trump campaign tweeted a One America News clip of Pick’s presentation.

“Wow! Blockbuster testimony,” Trump tweeted. “This alone leads to an easy win of the State!”

By evening, Pick’s excerpts of the State Farm Arena video had gone viral. Sean Hannity, the highest-rated host on conservative cable-news giant Fox News, called it a “bombshell” with “what appears to be extensive law violations.”

Ellis, Fox News and One America News did not respond to comment requests.

The Gateway Pundit identified one of the workers as Ruby Freeman. Other far-right outlets followed suit.

“What’s Up, Ruby? Crooked Operative Filmed Pulling Out Suitcases of Ballots in Georgia IS IDENTIFIED,” read a Gateway Pundit headline. It posted six photos of her, including one captioned, “CROOK GETS CAUGHT.” The story, shared by 38,000 people on Facebook, also identified Freeman’s business, LaRuby’s Unique Treasures. A follow-up Pundit story identified the woman in the blonde braids as Shaye Moss.

At about 10 p.m. that night, the threats began. Strangers rang, emailed and texted her with threats and racist taunts. They tagged her friends on Facebook and said “horrible” things about her, she later told police.

She read the 911 dispatcher the “What’s Up, Ruby?” headline, saying she believed the Gateway Pundit story might have triggered the harassment.

Over the next three days, local and state officials dismantled the Trump campaign’s claims. The so-called suitcases were standard ballot containers and the votes were valid and counted properly, they said. A Georgia secretary of state’s investigator concluded that observers and media hadn’t been asked to leave the arena and that “there were no mystery ballots that were brought in from an unknown location and hidden under tables.”

‘She should be shot’

On Dec. 4, the day after Pick’s presentation, Freeman told police she had received hundreds of threats at her home in neighboring Cobb County, according to a county police report.

The Trump campaign continued to portray Moss and Freeman as criminals. At a Dec. 5 rally in Valdosta, Georgia, Trump played excerpts of the State Farm Arena video on a giant screen, narrated by a host for far-right news channel One America News. The footage revealed a “crime” committed by “Democrat workers,” Trump said.

The next day, Dec. 6, a Gateway Pundit story described Freeman and Moss as “infamous in the annals of voter corruption.” That evening, Freeman called the police again.

She was scared, she said. Strangers had started to show up at her home, ordering pizzas for delivery to her address in an attempt to lure her out, according to a Cobb County Police incident report. She showed the officer 428 emails and text messages on her cell phone, almost all of them threats, the report said.

Cobb County Police said no one was arrested in response to the reported threats and declined further comment.

Freeman’s home address had been posted on Twitter and Parler, a social media platform popular among conservatives. Some Trump supporters publicly called for her and her daughter’s execution or hurled racial and misogynistic slurs at them on Facebook and other online forums.

“The coon c---s should be locked up for voter fraud!!!” wrote a Parler user. “She should be shot,” said a Facebook commenter under a Dec. 7 Gateway Pundit story. “YOU SHOULD BE HUNG OR SHOT FOR YOUR CRIMES,” wrote another Facebook commenter.

As the threats continued, Giuliani told the Dec. 10 hearing of Georgia lawmakers that he would “like to focus on the two people that are involved in this” – Freeman and Moss. In addition to “stealing votes,” he accused them of hacking into Georgia’s voting machines while passing USB thumb drives between them, “as if they’re vials of heroin and cocaine. I mean it’s obvious to anyone who is a criminal investigator or prosecutor, they’re engaged in surreptitious illegal activity.”

The Nov. 3 ceiling leak at State Farm Arena was, according to Giuliani, a “phony excuse” to clear observers and media from the voting area so Freeman and Moss could go “about their dirty, crooked business.” The leak was real – a urinal had overflowed – but state investigators found there was nothing to his claims about the women.

On Jan. 2, Trump placed his call to Secretary of State Raffensperger and other Georgia election officials, urging them to find enough votes to swing the election his way. They refused. Trump later denounced Raffensperger, a fellow Republican, who along with his family was inundated with death threats from the president’s supporters.

A recording of that call was leaked to reporters and published the next day, drawing global attention. Trump is heard claiming Freeman pulled suitcases “stuffed with votes” from under a table and scanned each ballot “three times.” She was “a professional vote scammer and hustler,” he said.

Two days later, on Jan. 4, Freeman again called the police and reported that strangers had come to her home, threatening that it was “just a matter of time” before they come for her and her family, according to a recording of a 911 call obtained by Reuters.

Freeman was so frightened that she refused to give her number to the 911 operator. “I’m just afraid right now of giving my number to anybody, even the police,” she said.

‘Safe house’

Barron, the supervisor of the two women, had kept in close touch as tormentors hounded them through December. The harassment increased after Trump’s call with Georgia officials went public, he said, especially for Freeman.

“Once President Trump mentioned her in that call to Raffensperger, it got even worse,” Barron said. “And it just kept going.”

By the end of January, dozens of stories in far-right and conservative publications had repeated Trump’s allegations against Moss and Freeman. On Parler, Freeman’s name featured in 1,512 comments and 204 posts, according to a Reuters review of archived posts on the social media platform.

“Only a matter of time before some vengeful person slips in through an open window of Ruby Freeman’s home and bludgeons her to death” with a voting machine, read a Parler comment on Jan. 4.

On Jan. 25, Barron emailed Fulton County police chief Wade Yates and other officials. The family needed protection, he said. “Can we do anything to help her and her family with security?” he asked, referring to Moss, in the email, reviewed by Reuters. Yates suggested hiring an armed guard at a cost of $22.50 per hour, according to an email. “We can work out funding details next week,” he said.

The women, however, never received funding for security, Barron said. And the cost was too high to pay for themselves, he said, exceeding Freeman’s $16 hourly wage.

Asked why Freeman and Moss didn’t receive a security detail, Fulton County Police said in a statement that it can’t approve budgeting in such a case and referred questions to the county government. The county government said it did not provide security for the women because the messages they received did not rise to the level of criminal threats that could be prosecuted. The decision was not financial in nature, it added.

In February, Moss told NPR about some of the harassment aimed at her and her mother for a report about the Trump camp’s pressure on Fulton County. After that, she kept a low profile.

In the spring and summer, Moss worked remotely a few days at a time to avoid going out in public. She spoke of feeling like she was being followed, Barron said. Moss also took sick days when the stress became overwhelming. Threatening calls came to an old cell phone of hers, which her teenage son used for remote school learning during the pandemic, he added.

Freeman left her home and went into hiding in an undisclosed location after Trump’s Jan. 2 call triggered more threats, Barron said. Moss blamed herself for upending her mom’s life, Barron said, and expressed regret for asking her to help with the elections.

The threats continued through the summer. In a July 1 email, Moss told Fulton County’s senior election officials she was shaken. A few weeks earlier, someone had put photos of her car and license plate online, Barron said, and strangers were contacting her family and friends.

“They are impersonating people like reporters, journalists, etc. to get info on me from them saying they are attempting to make a citizen's arrest,” Moss wrote in the email. “My mom is currently in a safe house,” she added.

On Aug. 14, a fresh Gateway Pundit article repeated Trump’s old allegations against them. “These two election workers took ballots out from under a table on Election night and jammed thousands of ballots into the tabulators numerous times,” it said.

New threats ensued. One reader, posting a comment under the story, evoked the history of lynching Black people in the American South: “Those two should be strung up from the nearest lamppost and set on fire.”

‘Target on our back’

Trump’s conspiracy claims turned Fulton County, a Democratic stronghold containing most of Atlanta, a majority black city, into a hotbed of threats against other election workers.

Nearly 100 messages to election officials documented by Reuters this year targeted officials and workers in the county, whose fast-growing population is making Georgia more competitive for Democrats.

Between 2004 and 2020, the share of white voters in Georgia dropped from 70% to 60%, and Democrats made significant gains, winning last year in the counties around Atlanta and turning the once-reliably Republican state into an electoral battleground, with Fulton on the front line.

“We know we have a target on our back,” said Robb Pitts, 79, chairman of Fulton County’s Board of Commissioners and a two-decade veteran of Atlanta’s city council. Pitts, who is Black, reported receiving threats himself, including a racist email in his inbox calling for his execution. “Who would have thought that this kind of thing would be happening in this country?”

The threats are happening elsewhere, too. In a Reuters survey of 30 county election offices in six hotly contested states in the 2020 presidential race, 13 said they were aware of threats or harassment directed at local election officials and staff.

Barron, Fulton County’s elections director for eight and a half years, said he was sickened by the racial slurs and threats against his Black staff members. “This is the best group of people I’ve ever worked with,” said Barron, who is white.

The son of a retired state judge, Barron began his career in elections in 1999 recruiting and training poll workers in Travis County, Texas. He served in other election roles before landing the top job in Fulton County’s elections office in 2013. After the intense scrutiny of the 2020 vote and the barrage of threats against him and his staff, Barron says he’s had enough.

He plans to leave his job at the end of the year. He said he’s disgusted by the vilification of election workers like those on his staff.

“It’s not worth it anymore,” he said.

But Moss is staying, Barron said. He says he understands why. As a single mom, she needs the paycheck and the health insurance.

Anti-abortion and abortion rights advocates demonstrate in front of the Supreme Court, June 25, 2018. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Anti-abortion and abortion rights advocates demonstrate in front of the Supreme Court, June 25, 2018. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Why it matters: The GOP has the best political environment in a decade leading into the midterms — and the last thing top party operatives want is for the Democratic base to become energized if the Supreme Court narrows or overturns Roe v. Wade.

- As one longtime GOP political operative put it to Axios, it's one “big flare-up” that could “derail what could be a 2010-level victory next year for the party and the movement."

- "Republicans and operatives in the party, I don’t think they’re ready. They better get ready before this decision comes out," the operative said.

What they’re saying: Rep. Nancy Mace (R-S.C.), who represents a district that includes suburbs of Charleston, acknowledged that overturning Roe would bring the issue front and center and urged Republicans to handle such an event cautiously.

- “We’ve got to have compassion on both sides of the aisle and recognize at some point, this is an infant and this is life, and also on my side, recognize that we've got to be advocates for women who've been raped,” she told Axios.

The details: Despite the entrenched red state/blue state divide, overturning Roe could persuade suburban women who would have otherwise likely voted for Republicans to vote for Democrats, two operatives told Axios.

- A Republican campaign strategist said such a ruling would be a messaging challenge for GOP candidates, and said they should calibrate their statements differently for general election voters than they would for primary voters.

- “In primaries, the issue will be a talked about as a huge victory, and in general elections it will be about giving people a voice in their state’s abortion policies,” the strategist said.

- States would be able to ban or severely restrict abortion access if the Supreme Court strikes down Roe, which seemed to be a real possibility during oral arguments yesterday. In that situation, operatives say, Republican-led states may want to tread lightly, to avoid a political backlash to especially stringent restrictions.

By the numbers: A November poll by Quinnipiac University found that 63% of Americans agree with the 1973 Roe decision, including 87% of Democrats and 65% of independents but just 37% of Republicans. 53% of Republicans disagreed with the ruling.

- One Republican operative pointed to suburbs surrounding smaller cities like Charleston and Des Moines as places to watch if Roe falls.

- Former Republican Rep. Tom Davis, who chaired the National Republican Congressional Committee, said there’s "no question that if this happens, it will be a front and center issue for voters.”

- While he doesn’t believe Republicans would lose the House over the issue, Davis said “there’s no question that in higher-income districts, it could have an effect.”

But, but, but: History is on Republicans’ side, as the party in power tends to lose seats in Congress. That history, coupled with redistricting and a slew of Democratic retirements, means Democrats would need to defy the odds to keep the House.

- Other operatives believe that pocketbook issues will continue to be the more salient issue.

- “[Democrats] are desperate to find anything to talk about other than skyrocketing inflation and the President’s plummeting approval ratings, and think a couple Supreme Court cases will do the trick. But they won’t,” Kevin McLaughlin, former NRSC director, told Axios.

Michelle Helm, left, holds her daughter, Tiara, who sued police officers in Rainbow City, Alabama, after one used a Taser on her in January 2015. (photo: Lynsey Weatherspoon/The Marshall Project)

Michelle Helm, left, holds her daughter, Tiara, who sued police officers in Rainbow City, Alabama, after one used a Taser on her in January 2015. (photo: Lynsey Weatherspoon/The Marshall Project)

Suddenly, Helm collapsed. Her body convulsed. Her head thrashed against the concrete floor.

She was gripped by one of the seizures that had plagued her since a car accident. When the high school junior came to, she found four Rainbow City police officers on top of her, pinning her down. Scared and disoriented, she begged to be let go and fought to get free.

The officers, who initially tried to keep her from hurting herself, decided she had become combative, according to multiple court records. They tightened their holds, leaving red marks on her arms. One wrapped his forearm around her neck in a headlock.

A fifth officer arrived — armed with a Taser. He warned her he would use it if she didn’t settle down and behave. She cursed at him. He pressed the Taser into her abdomen and pulled the trigger. Her body jerked. She screeched in pain.

Paramedics took Helm to a hospital in nearby Gadsden, where she was soon released, court records show. Officers never arrested her or charged her with anything.

Little of what happened to Helm is in dispute. Having a seizure is not a crime. She was not a threat to the police or general public, as a judge later ruled. Using a stun gun on someone who has been having seizures isn’t department policy or standard medical procedure. In fact, medical experts warn against even holding down people having seizures because they can perceive restraints as assaults.

There was no internal affairs investigation of the January 2015 incident, according to the police chief, who was one of the officers involved. The officer who used the Taser on Helm was promoted about a year later.

Helm said she never got an apology from police, or even an acknowledgment that they mistreated her. “That somebody could ever do something like that on purpose — never will that be okay,” she said.

Eventually, Helm and her family turned to the last resort of people who think they were wronged by police: a lawsuit.

Every year, thousands of people file lawsuits against the police in federal court, alleging that officers violated their civil rights. It can take years to go to trial.

Most don’t get that far. Federal judges dismiss the majority of cases in favor of police. Officers are often protected by “qualified immunity” — a legal doctrine that shields government workers from being sued for their actions on the job, except in rare circumstances.

About 5% of plaintiffs who claim police abuse make it to trial, according to Craig Futterman, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School. Of those, only a third prevail in court.

“There is an extraordinary imbalance in terms of both power and presumed credibility,” Futterman said.

In July 2015, Helm filed a civil rights lawsuit in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, claiming police used excessive force, falsely imprisoned her and three officers failed to intervene to protect her from harm.

Helm had no idea back then, she said in an interview, that she would grow into an adult as her case slogged through the federal civil court system.

*******

Helm said she can almost draw a line through her life. Before the concert. And after.

She grew up in Rainbow City, 26 square miles of rolling rural roads with views of the Coosa River. It’s home to just over 10,000 people — and a 25-officer police department.

Daniel Helm, her father, was a carpenter who was fatally electrocuted on the job when Tiara was almost 3. Her mother, Michelle Helm, supported five children cleaning houses and preparing IRS forms at Jackson Hewitt Tax Service.

Tiara had just turned 15 when a drunk driver hit her as she was walking home in October 2012. She had her first “grand mal” seizure about a year later. A doctor diagnosed epilepsy and thought the car accident was related, Michelle Helm said in court testimony.

During a seizure, Tiara’s body stiffens and her feet contort inward. She growls and spits. Her head thrashes and her eyes roll back. She sometimes bites her tongue or her lip.

“I feel like I’m suffocating,” she said. “I black out.”

Despite her seizures, her mom allowed Helm to do normal teenage things, like play varsity soccer. And attend one of the biggest concerts her little town had ever seen.

When Helm went back to school after the incident, her peers kept asking what happened. A false rumor spread that her seizure was drug-induced. She stopped going to school.

Their small town suddenly felt much smaller. Strangers approached mother and daughter at Walmart, offering their opinions on what happened that night.

Tiara Helm said she hated herself for quitting school and soccer. “I felt like everything I had going for me was out the window,” she said. She worked at Sonic and a drive-thru BBQ joint in nearby Gadsden.

By summer 2015, around the time she and her mom filed their civil rights suit, Helm tried heroin and meth. Drugs made her feel something besides numb, she said.

She also started cutting herself. She found a razor blade in her best friend’s garage and carved the words “why me” inside her left forearm. The words, now a faded white scar, remain visible.

The lawsuit ground on. Defense lawyers asked a federal judge to decide the case without holding a trial. They argued the officers were protected under qualified immunity.

In March 2019, U.S. District Judge Annemarie Carney Axon, appointed by former President Donald Trump in 2018, ruled that a jury should decide Helm’s claims against the police. She noted that Helm wasn’t a flight risk or a threat to the officer who used a Taser on her “or, for that matter, to anyone else.”

The officers appealed, and the case dragged on for another two years. During this time, Helm said, she really spiraled down: “I was angry, so that pushed me to be ugly to my mom, ugly to my sisters, ugly to myself.”

Over a two-year span, police arrested Helm for possession of drug paraphernalia, marijuana and Suboxone, and for not giving police her full name during a traffic stop. In June 2020, outstanding warrants landed her in the Etowah County Detention Center. Six months later, she pleaded guilty in drug court to drug possession and obstruction of justice and enrolled in rehab.