Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

It was interesting to hear this annual argument between two people who loved each other dearly. I knew that, doctrinally, Dad was correct but Mother’s position was one of love, and love prevailed, and we had Christmas year after year.

I’ve had some dismal Christmases. The Christmas of the goose, when I took the goose out of the oven and hot grease spilled on my wrist and I dropped it and the glass baking dish broke and the goose skidded across the kitchen floor collecting cat hair and glass fragments. One year we did a Dickensian Christmas, had a tree with candles, did a group reading of A Christmas Carol and discovered that Scrooge has all the good lines, and nobody wants to be a Cratchit, they are such wimps. The reading was interrupted by screams — the tree was on fire. Candles make sense if you have a freshly cut tree and ours had been harvested in September in Quebec. But the fire rescued us from Dickens so all was well.

One of my favorite Christmases was the “Orphans Christmas” many years ago when we had ten guests at dinner, all of them musicians far from their families, a very lively bunch, and I, the lone writer, cooked the rib roast and waited on table. They were friends of my wife and all knew each other from freelance gigs so it was an accidental family, and they were full of stories and the conversation never sagged and the repartee sparkled and I didn’t have to say a word, which, as a Minnesotan, I appreciated. I come from withdrawn people, I know how to stifle myself.

Welcoming visitors is a Christmas tradition going back to the ones from the East who brought frankincense and myrrh, and this year we are entertaining our London relations who brought cookies and arrived during a Minnesota blizzard, which they thought was perfectly wonderful. My son-in-law came in on a bitterly cold morning and said, “Delightful.” They brought merriment with them, which is the best you can hope for from a guest, and all week long the flat, what we think of as an apartment, has been full of talk and laughter. I’ve learned the expression “two shakes of a rat’s tail,” which means Very Soon. We put tomahtoes, not tomatoes, in the salad and learned that “smart” means stylish, not intelligent, and heard words such as “smashing” and “brilliant” that we laidback Midwesterners hesitate to use. One morning over breakfast, I got a long fascinating lecture about the Saxons and Normans and the Battle of 1066, with some footnotes about the decorous execution of Charles the First in 1649. I can’t recall another time when beheading was discussed at breakfast. Fascinating. It was a chilly day and Charles dressed warmly so he wouldn’t shiver, which the crowd might interpret as cowardice. He himself gave the signal for the ax to descend and his head was severed with one blow.

These Londoners are ambitious hikers and don’t sit around waiting to be entertained, they go out and look and come back exhilarated, even euphoric, by what they’ve seen. An old Soo Line freight car, a display of Victorian lamps, a Christmas tree lot, the light at dusk.

I am a quiet man, descended from a culture in which a great deal is left unsaid. Children were shushed and so learned to shush themselves. When I was young, I thought enthusiasm betrayed naivete, and I am still trying to escape from this straitjacket. Christmas cannot make us merry unless we’re willing to step out of our self-imposed restraints and celebrate, which I used to do with whiskey and wine but put all that away twenty years ago. But the day dawned on the 22nd and the north began to tilt toward the sun and life resumes. Meanwhile we have each other and if someone knocks on your door, invite them in, and it’ll be Christmas.

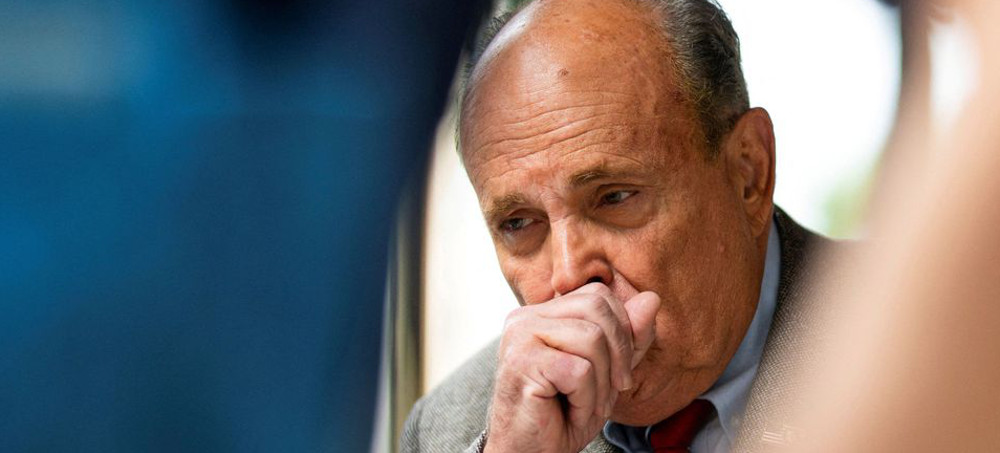

Former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani coughs as he speaks to media about the U.S. evacuation of Afghanistan. (photo: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters)

Former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani coughs as he speaks to media about the U.S. evacuation of Afghanistan. (photo: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters)

The defamation lawsuit was filed on Thursday in federal court in Washington, D.C., by Wandrea "Shaye" Moss, a voter registration officer in Fulton County, and her mother, Ruby Freeman, who was a temp worker for the 2020 election.

The lawsuit targets San Diego-based Herring Networks, which owns and operates One America News Network, as well as the channel's chief executive Robert Herring, president Charles Herring, and reporter Chanel Rion.

Giuliani, Trump's former personal lawyer, was also named as a defendant. Giuliani has frequently appeared on OAN's programs and has been one of the biggest promoters of Trump's false claims that voter fraud cost him the 2020 election.

The complaint alleges that OAN broadcast stories in which Moss and Freeman were falsely accused of conspiring to produce secret batches of illegal ballots and running them through voting machines to help then-candidate Joe Biden defeat Trump.

There is no evidence to support such claims, which have been repeatedly debunked by Georgia election officials.

In a brief interview, OAN chief executive Robert Herring Sr. told Reuters he was not concerned about the lawsuit and that his network had done nothing wrong.

"I know all about it and I'm laughing," he said of the lawsuit. "I'm laughing about the four or five others who are suing me. Eventually, it will turn on them and go the other way."

Charles Herring, Rion and Giuliani did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The defamation lawsuit is the second filed this month by Moss and Freeman, who also sued the Gateway Pundit, alleging the far-right website's unfounded reports incited months of death threats and harassment against them.

The Gateway Pundit did not immediately respond to an email sent through its website seeking comment.

In addition to removing the reports about Freeman and Moss from OAN's websites and other media channels, the lawsuit seeks compensatory and punitive damages.

The OAN and Gateway Pundit lawsuits both revolve around false allegations first raised by a volunteer Trump campaign attorney at a Dec. 3 hearing of Georgia state legislators. Freeman and Moss worked in heavily Democratic Fulton County, which includes Atlanta, where a strong showing by Biden helped give the Democrat a narrow Georgia victory.

Trump, a Republican, and his surrogates used surveillance video of the vote count at State Farm Arena to falsely accuse Freeman and Moss of processing "suitcases" full of fake ballots for Biden late at night on Election Day, Nov. 3, 2020, after most poll workers and election observers left.

According to the complaint, Giuliani then "amplified the video by posting about it on social media," while "OAN, its hosts, and its staff" took Giuliani's assertions and "published them to millions of its viewers and readers."

State officials including Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger quickly and forcefully denied the allegations, explaining that the "suitcases" were standard ballot containers and the votes were properly counted under the watch of an independent monitor and a state investigator.

Giuliani has falsely claimed that the video footage showed the two women engaging in "surreptitious illegal activity" and acting suspiciously, like drug dealers "passing out dope."

In early January, Trump himself singled out Freeman, by name, 18 times in a telephone call in which he pressed Georgia officials to alter the state's results. He described Freeman as a "known political operative" who "stuffed the ballot boxes."

People that both support and oppose the nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett demonstrate in front of the Supreme Court of the United States, October 26, 2020, in Washington, D.C. (photo: Samuel Corum/Getty)

People that both support and oppose the nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett demonstrate in front of the Supreme Court of the United States, October 26, 2020, in Washington, D.C. (photo: Samuel Corum/Getty)

There are few fights as urgent in American politics as the one to reduce the reactionary, undemocratic power of the Supreme Court. To win that fight, reformers should examine how FDR took his case for court reform to the masses.

Those who felt the commission was a mere academic exercise, a Band-Aid on a constitutional bullet hole, felt largely vindicated. But as law professors Samuel Moyn and Ryan D. Doerfler write in the Atlantic:

If the commission was intended to be the place where Court reform went to die, its effect in the long term may be the opposite. With calls to change the Court still very much alive, ideas that were once fringe have now moved to the center of Court discourse. And with radical action by the Supreme Court continuing in the coming years — likely starting with the overruling of Roe v. Wade but not stopping there — we may look back on the commission as helping to set reform in motion, rather than stopping it in its tracks.

That is to say, the fight for meaningful court reform will not necessarily end with the mere demise of a commission. A collective push for judicial change is needed, one that does not fizzle out when the law faculty meeting ends. The situation is too urgent.

Chief Justice John Roberts and associate justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett (all products of the modern conservative legal movement) are projected to “radically reshape the nation” with their pro-business, anti-regulatory jurisprudence. If we want to move toward social democracy, we need a court that uses the law to advance, not hinder, the welfare and protection of the poor and working class.

The judicial reform movement of the modern era is in what sociologists Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow define as the preliminary stage, one in which “people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge.” At this initiation point, history often acts as a guide. Regarding court reform, a similar moment exists: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s attempt to restructure a conservative court and salvage the New Deal.

The story of Roosevelt’s effort to “pack the court” is often remembered in the popular imagination for the numerical rhyme associated with its conclusion: “the switch in time to save nine.” But the original court fight — one of direct presidential intervention, broad resistance, impassioned liberal messaging, and an ultimate, albeit lackluster, victory for progressive interests — offers a substantive case study in a fight to restructure a branch of American government that emphasizes a connection between implementing of social democratic measures and the law.

A Forceful Presidential Recognition

Congress is attempting to push through massive spending programs to aid working families in the aftermath of global financial upheaval. A conservative-leaning high court is expected to block measures meant to address widespread economic precarity. The year is 1937, and President Roosevelt, recognizing the judicial threat to his legislative agenda, delivers a fireside chat to millions of Americans, proposing the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill.

“This plan of mine” — the appointment of an additional justice for every sitting justice who was over seventy years old (six, in FDR’s case) — “is not attacking of the court,” the president’s voice crackled over radio speakers in homes across the country. “It seeks to restore the court to its rightful and historic place in our system of constitutional government and to have it resume its high task of building anew on the Constitution ‘a system of living law.’”

The plea to the American public came amid expected resistance from a powerful bloc of conservatives on the court. George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, James McReynolds, and Willis Van Devanter (a group dubbed “The Four Horsemen”), along with a right-leaning chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, were, according to the president and his advisers, likely to strike down upcoming legislation including the establishment of Social Security and the National Labor Relations Board. (Their judicial kill list already included the Railway Pension Act and the National Industry Recovery Act.) Now, the five unelected officials serving for life were on the verge of denying the elderly a stable income and workers a collective bargaining tool in the post-Depression economy.

The expected conservative rulings were par for the course in terms of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century jurisprudence. After the end of Reconstruction and during the Gilded Age, on behalf of the robber barons of the era, the court struck down attempts to disrupt the established order of inequality. Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Co (1895), for example, rendered the first peacetime tax on income unconstitutional. But in 1937, the court’s lingering conservatism was hindering a presidential agenda.

“The courts,” FDR proclaimed via radio from the White House, “have cast doubts on the ability of the elected Congress to protect us against catastrophe by meeting squarely our modern social and economic conditions.” The broadcast amounted to an awesome use of the bully pulpit to underscore the need for a system of law that allowed the state to loosen the grip of laissez-faire attitudes.

Today, Biden finds himself in a similar position as he attempts to guide his party through the passage of massive social spending and regulatory measures in a postcrisis economy, alongside a court stacked with conservative justices appointed by the opposition. Measures in the Democrats’ reconciliation bill meant to address, for example, economic inequality (a wealth tax) and pending climate doom (higher regulatory scrutiny for carbon emitters) are seen as dead on arrival before a six-three conservative bloc — not to mention action on voting rights and labor protections, both curbed by another anti-democratic measure, the filibuster, but just as likely to be struck down by the current court.

The difference between then and now rests in the response: whereas FDR clamored for direct sweeping change, President Biden has not only failed to deliver a single major address on court reform — he refuses to take a clear stance on the Judiciary Act of 2021, a law that would, in part, add three justices to the bench.

A Message to Address Broad Resistance

John Nance Garner, a traditionally conservative Texan and FDR’s vice president, put a finger up to the bridge of his nose and pinched— his other hand gestured a thumbs down. The reaction came in response to the news of the president’s plan to restructure the court.

With widespread condemnation of the court-packing plan at hand, liberals of Roosevelt’s era took their case to the American people. One foot soldier was a young Lyndon Baines Johnson, then running in his first campaign for elected office. Standing before farmers of Texas’s Tenth Congressional District, Johnson told the agrarian downtrodden that their fates were all but linked with the court.

“John Miller,” Robert Caro quotes Johnson as saying in his biography of the eventual president, “didn’t you just now tell me you was going under when the soil conservation came in, and they started payin’ you to let your land lie out? Well, whose program is it that’s paying the farmers to let their land lie out?” Johnson answered his own question without pause: “Roosevelt’s program.”

He continued, “Take the CCC” — the Civilian Conservation Corps, a federal program putting hundreds of thousands of men to work on environmental conservation projects. “Now, it’s helping you, Herman.”

With a hostile court, Roosevelt’s programs, based on a broad interpretation of constitutional power that redefined and strengthened the government’s role in social and economic life, were at risk of being overturned. If the striking down of a law materialized, Johnson illustrated, it would impact you, the worker. And it wasn’t from a polished Washington dais, but from the ground on which the laborer toiled that Johnson laid out the benefits of passing the Judiciary Act.

The leaders emerging in the modern judicial fight should note Johnson’s campaign tactic. Some on the progressive left have begun taking up the rhetorical mantle of judicial reform, albeit with room for improvement. This includes Representative Mondaire Jones, Democrat from New York, a vocal opponent of the court (“Our democracy has been under assault for decades, and the Supreme Court has dealt many of the sharpest blows,” he wrote on Twitter last year) and Representative Ro Khanna, Democrat from California, who spearheaded efforts to impose term limits on Supreme Court justices.

While the lawmakers’ efforts are a worthy starting point, they are also children of the Washington press release and social media punditry that is disconnected from the suffering of average Americans. Court-reform messaging needs to focus on the intersection of the court’s decisions and individuals’ material conditions — how current jurisprudence either halts or hinders tangible elements of a social democratic society.

A Semi-Victory?

Eventually, FDR’s message seemed to break through — perhaps not to the public at large (the scramble to restructure the third branch of government lasted less than six months) but to the court itself. Historians debate the ultimate reason the court fight ended. The simplest and most popular explanation lies at the heart of the rhyme associated with the saga, contending that the three court decisions favoring FDR involving minimum wage, Social Security, and the National Labor Relations Act, which came about once Justice Owen Roberts began voting with the more liberal justices, helped end the efforts to pack the court.

But there was another element at hand: a key conservative justice, Willis Van Devanter, decided to retire. Whatever the reason, FDR’s bottom-line objective — safeguarding progressive legislation from unfavorable judicial review — was successful.

But his ultimate goal — restructuring an institution in which measures meant to advance the general welfare of average Americans hinge on nine votes — failed. Today’s judicial reform movement has the opportunity to revive the fight for that goal.

Elements of FDR’s fight can be put to use today: the use of the bully pulpit to signal the gravity of the judicial emergency at hand and the dispatch of elected and campaigning officials to convey the benefits that a fairer judicial system would bring to voters, particularly low-wage workers. But the contemporary struggle to move toward a more social democratic court must last longer than the six months waged in the fight of 1937 — and can’t end in capitulation to establishment party forces.

It is unclear what direction the nascent movement to restructure the court will take after the demise of the presidential commission. Whatever the strategy, the Left should seize a moment in which judicial reform ideas are entering the mainstream and dominating portions of the political conversation for the first time since 1937. If we don’t, the court — an inherently anti-democratic institution currently stacked with right-leaning justices serving life terms — will continue to block measures meant to foster a more just, less exploitative society.

Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-WV) walks to a Democratic policy luncheon on Capitol Hill on Dec. 16. (photo: Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-WV) walks to a Democratic policy luncheon on Capitol Hill on Dec. 16. (photo: Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

His offer comes as fellow a Democrat, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, raises new concerns, illustrating that the party has work to do

Despite its endorsement from the most conservative Democrat, the tax on billionaires still faces long odds to approval as part of the final legislation, as it has been greeted skeptically by other Democratic lawmakers in both the House and Senate. It was also left out of the House Democrats’ version of Build Back Better after Manchin publicly criticized it in October.

Manchin’s offer to the White House — details of which The Washington Post reported earlier this week — included a list of spending and revenue proposals that he supports. Manchin listed the tax on billionaire wealth as an option toward the bottom of his list, the people said. It is unclear whether Manchin’s plan included a revenue estimate. The people spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the private offer.

Manchin’s inclusion of the measure reflects the potential common ground that remains between the president and the senator in his party most uneasy about the White House’s sprawling economic agenda, which could cost as much as $2 trillion over 10 years and remake significant parts of the American economy. Alan J. Auerbach, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley, has been advising Manchin personally about tax policy, two people familiar with the matter said. Auerbach declined to comment.

But other considerable obstacles remain.

For months, Manchin has been largely supportive of the White House’s tax and revenue plans, focusing his criticisms on spending measures he says are poorly designed and that would trigger more inflation and explode the national debt. Those concerns have yet to be resolved. But Manchin is not the only Democrat with policy issues that remain unaddressed.

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), long the biggest hurdle to Democrats’ tax aspirations, has again in recent days raised concerns about some of the revenue measures the party is pursuing.

In particular, Sinema has questioned whether owners of “pass-through” entities — companies structured so the owner “passes through” income onto their personal income tax returns — should be exempted from a new “surtax” intended to fall on the very rich, two people familiar with the matter said. These people spoke on the condition of anonymity to reflect private conversations.

The White House was forced to dramatically revamp its tax proposals after Sinema previously ruled out increasing the corporate tax rate, which Biden initially sought to raise from 21 percent to 28 percent. To make up for the lost revenue, the White House and Sinema agreed to a number of measures, including the new “surtax” that would impose a 5 percent levy on top of income earned above $10 million in a given year and an additional 3 percent levy on income above $25 million per year. Roughly 22,000 people, or 0.02 percent of U.S. households, would be affected by the measure.

The surtax as drafted would apply to both ordinary income and capital gains income. Exempting pass-through entities from that measure could deprive Democrats of billions of dollars they are counting on to ensure their plan does not add to the national debt. It is unclear whether Sinema will make the request conditional for advancing the broader economic legislation.

Spokespeople for Manchin and Sinema declined to comment. The White House also declined to comment.

While the specifics of what Manchin would support remain unclear, Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) has unveiled a tax aimed at the accrued wealth of America’s approximately 700 billionaires. The measure is aimed at addressing the massive gains of the wealthiest Americans with a federal tax and probably would be unprecedented in how few people it affected. Some Democrats, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), have expressed concerns that the measure was hastily drafted and not thoroughly vetted. Congress’s nonpartisan scorekeeper has estimated it could raise as much as $550 billion over 10 years, or pay for more than one-quarter of the Democrats’ spending bill.

Sinema has been supportive of the tax measure on billionaires after extensive conversations with Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). The New York Times reported in October that Manchin criticized the billionaire tax by saying he did not “like the connotation that we’re targeting different people,” adding that many of these people “create a lot of jobs and invest a lot of money and give a lot to philanthropic pursuits.”

Supporters of former president Donald Trump rallied in Detroit in November, claiming widespread election fraud. (photo: Steve Nerving/Metro Times)

Supporters of former president Donald Trump rallied in Detroit in November, claiming widespread election fraud. (photo: Steve Nerving/Metro Times)

Research identifies at least 262 bills were introduced in 41 states this year with the intent to hijack the election process

A year that began with the violent insurrection at the US Capitol is ending with an unprecedented push to politicize, criminalize or in other ways subvert the nonpartisan administration of elections. A year-end report from pro-democracy groups identifies no fewer than 262 bills introduced in 41 states that hijack the election process.

Of those, 32 bills have become law in 17 states.

The largest number of bills is concentrated in precisely those states that became the focus of Trump’s Stop the Steal campaign to block the peaceful transfer of power after he lost the 2020 presidential election to Joe Biden. Arizona, where Trump supporters insisted on an “audit” to challenge Biden’s victory in the state, has introduced 20 subversion bills, and Georgia where Trump attempted to browbeat the top election official to find extra votes for him has introduced 15 bills.

Texas, whose ultra-right Republican group has made the state the ground zero of voter suppression and election interference, has introduced as many as 59 bills.

“We’re seeing an effort to hijack elections in this country, and ultimately, to take power away from the American people. If we don’t want politicians deciding our elections, we all need to start paying attention,” said Joanna Lydgate, CEO of the States United Democracy Center which is one of the three groups behind the report. Protect Democracy and Law Forward also participated.

One of the key ways that Trump-inspired state lawmakers have tried to sabotage future elections is by changing the rules to give legislatures control over vote counts. In Pennsylvania, a bill passed in the wake of Trump’s defeat that sought to rewrite the state’s election law was vetoed by Democratic governor Tom Wolf.

Now hard-right lawmakers are trying to bypass Wolf’s veto power by proposing a constitutional amendment that would give the legislature the power to overrule the state’s chief elections officer and create a permanent audit of election counts subject to its own will.

In several states, nonpartisan election officials who for years have administered ballots impartially are being replaced by hyper-partisan conspiracy theorists and advocates of Trump’s false claims that the election was rigged. In Michigan, county Republican groups in eight of the 11 largest counties have systematically replaced professional administration officials with “stop the steal” extremists.

Several secretaries of state, the top election officials responsible for presidential election counts, are being challenged by extreme Republicans who participated in trying to overturn the 2020 result. Trump has endorsed for the role Mark Finchem in Arizona, Jody Hice in Georgia and Kristina Karamo in Michigan who have all claimed falsely that Trump won and should now be in his second term in the White House.

Jess Marsden, Counsel at Protect Democracy, said that the nationwide trend of state legislatures attempting to interfere with the work of nonpartisan election officials was gaining momentum. “It’s leading us down an anti-democratic path toward an election crisis,” she said.

Ahmad Abdul Qader, a soldier, walks along the slow-flowing Sirwan River on the border with Iran near Halabja, Iraq. (photo: Marcus Yam/LA Times)

Ahmad Abdul Qader, a soldier, walks along the slow-flowing Sirwan River on the border with Iran near Halabja, Iraq. (photo: Marcus Yam/LA Times)

“They grow big. Their juice is sweet. They’re incomparable. I don’t say this as a nationalist, as someone who loves their country. It’s just fact,” he said, speaking about them like you would a long-lost love.

In a sense, he was. This corner of Diyala province, which stretches from the center of Iraq to the country’s east, was once famous for its pomegranates. Everywhere you drove, you’d encounter acres of trees laden with blood-red baubles. Yassin had three fields and a vineyard.

Not these days. Standing in one of his plots, Yassin pointed out a few desiccated-looking trees and the churned brown of recently tilled fields. Like other farmers in Diyala, he had given up. Over the last few months he cut down most of his pomegranate trees; he just finished plowing over his vineyard.

“If you saw this area 10 years before, I swear you would think you’re in Eden,” he said.

“But there’s just no water. We couldn’t do it any more.”

Diyala is perhaps the starkest example of Iraq’s impending Great Thirst. The country — fed not by one but two mighty rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates — is thought to be where humans first started cultivation: Mesopotamia, the land of plenty.

But another year of crippling drought and of competition with equally parched neighbors means there isn’t enough water to go around. Both Turkey and Iran have activated dams and tunnels to divert water from tributaries of the Tigris and Euphrates, leaving downstream Iraq — which relies on the two rivers’ largesse for 60% of its freshwater resources — with an acute shortage.

This year, inflows from Turkey fell by almost two-thirds; from Iran they’re about one-tenth of what they were, said Mahdi Rashid Hamdani, Iraq’s minister of water resources, said in an interview.

In desperation, Baghdad has appealed to its neighbors to help mitigate the crisis. In October, the Water Ministry invoked an agreement with Ankara that’s supposed to ensure Turkey’s “fair and equitable” contributions to the Tigris and Euphrates. In Tehran, the appeal has been met with silence, Iraqi officials say.

“Iran hasn’t cooperated with us at all. It diverted rivers to areas inside the country and doesn’t work with us to share the damage from the drought,” Hamdani said, adding that his ministry has completed procedures for a lawsuit against Iran and asked the Iraqi Foreign Ministry to contact the International Court of Justice. A spokesman for the Foreign Ministry did not respond to questions on the matter.

The water scarcity is compounded by wider shifts in the environment. This year, temperatures in Iraq reached 125 degrees, and the country is experiencing 118-degree days more frequently and earlier in the year. Berkeley Earth, a California-based climate science organization, found that temperatures in Iraq have increased at double the world average.

Last year, Iraq ranked No. 5 on the United Nations’ list of countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. By 2050, the World Bank said in a report last month, a temperature increase of 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) and a precipitation decrease of 10% could cause Iraq to lose fully one-fifth of its available fresh water.

Under those circumstances, nearly one-third of Iraq’s irrigated land won’t have water.

That’s already the reality in Diyala. Almost all of the province was dropped from the government’s agricultural plan for summer crops, excluding farmers there from water appropriations in favor of irrigating strategic crops such as barley and wheat. The same thing happened in October. Instead, Diyala’s farmers have had to rely on roughly 200 wells to slake their orchards’ thirst as well as their own.

For many here, the changes mean the end of a way of life.

In 2010, Yassin, having saved enough money from his engineering work in the northeastern city of Sulaymaniya, decided to take up farming on his family’s land near Miqdadiya, a city in Diyala about 50 miles northeast of Baghdad. His father, a farmer, discouraged him, warning that he would lose his investment. Yassin went ahead anyway.

“Farming is an addiction,” he said, recalling how, as a child, he would accompany his father to the fields, and how the roads were choked with people coming from all over Iraq to buy Diyala’s pomegranates, apricots and oranges.

Yassin poured tens of thousands of dollars into the effort, installing drip irrigation to create a modern, profitable farm.

But he soon found out his father was right: The margins didn’t make sense. The government cut support for fertilizer, seeds and the gas he needed to run pumps. And though the state had banned importing certain types of produce to protect Iraqi farmers, the right bribe at the right checkpoint meant that truckloads of fruit from Iran, Turkey, Syria and Yemen still showed up at local markets, undercutting local growers.

The water shortage delivered the killing blow.

The last three years were especially hard, Yassin said, forcing farmers to dig deeper wells to hit groundwater, which in turn turned increasingly brackish from overpumping. Stepping through his neighbor’s orchard, he grabbed a plump-looking pomegranate from one of the trees.

“From outside it looks good,” he said. “But inside…” He cracked open the fruit in his hands to reveal dull yellow innards and the translucent red of the seeds; there wasn’t a drop of juice.

His neighbor had tried everything. “He has money. He dug wells, put pipes, installed pumps. Nothing worked,” Yassin said, adding that now the neighbor grew produce only for personal consumption.

Downstream in Balad Ruz, about 20 miles southeast of Yassin’s farm, Ghadban Tamimi had for decades planted his 300-acre property with pomegranates, wheat and rice. (“Balad Ruz” means “rice field.”)

This year? Not a single acre. The last time the canal he relied on for irrigation had proper flow was seven months ago. Now it had only sewage. Digging a well was no use.

“We went down 140 feet — nothing but saltwater,” he said.

Convinced that theirs is now literally a fruitless pursuit, many farmers have abandoned their plots, Tamimi said. “From here to 10 miles on, you’ll find villages with no one in them. We were nine families. Now it’s three.”

You can see the crisis in Lake Hamrin, an artificial 130-square-mile reservoir. It’s fed by the Halwan River, another tributary of the Tigris that begins in Iran’s portion of the Zagros Mountains.

On Google Maps, the reservoir shows up as a blue dagger stabbing the heart of Diyala. The Diyala-Kirkuk highway threads through the dagger’s tip. Years ago, authorities had to shore up the highway’s sides because the water lapped its edge. But now the basin is bone-dry.

Trudging along the basin’s exposed floor, Wissam Wadi, a 29-year-old shepherd, watched his flock kick up swirls of dust as it foraged on shrubs growing out of the cracked earth. It took Wadi an hour and a half to find this patch. In the past, he would’ve found plenty of suitable areas within a half-hour’s walk of his home.

He and his colleagues lost 300 sheep from heat and lack of water in July, when temperatures in parts of Iraq soared above 110 degrees. The survivors, he said, are a stunted 60 pounds each compared with the nearly 100-pound sheep he raised in the past.

“What are they supposed to eat? Dirt?” he said. “The land that we had, it was our gold. Now look at us: No salaries, nothing. We were living off this lake. And it’s gone.”

From the window of his office overlooking the Darbandikhan Dam 80 miles northeast of Diyala, along the Sirwan River, Rahman Khani has a front-row view of the water crisis. As the dam’s director, it falls to him to regulate river flows to farmers as far as Basra, in Iraq’s deep south.

By November, he should have been releasing water at a rate of about 6,600 gallons per second. He was supposed to get double that amount from Iran, which controls 70% of the dam’s 7,000-square-mile catchment area and which recently activated a 29-mile diversionary tunnel siphoning away most of the Sirwan River.

That and the lack of rain have dried up the dam’s inflows to one-fifth of what Khani was expecting.

“Just look out the window and you’ll see it,” he said, pointing to a discolored line on one of the dam’s towers where the water once reached. It was more than 23 feet above the current level.

“You’re telling me the view from here is nice. But for me, it’s a source of worry.”

Iran’s exports of produce to Iraq, Khani said, amounted to an indirect purchase of water.

“If we’re not planting in Iraq, then we’re essentially buying water from Iran through their fruits and vegetables,” he said, adding that he had received no communication from authorities on the Iranian side — not even basic information on expected inflows.

That tension over water persists all the way beyond the mountains near Halabja, where the Sirwan forms the border between Iran and Iraq. One recent afternoon, Iraqi Kurdish forces Cmdr. Ahmad Abdul Qader walked down to the river. Though Sirwan means “shouting river,” its sound was reduced to an indifferent burble.

“The Iranians only allow the water to come a few hours a day,” Abdul Qader said.

In 1988, during the closing days of the Iran-Iraq war, when Iraqi President Saddam Hussein bombed Halabja’s Kurds with chemical weapons, many residents fled to the river, running across a narrow footbridge, Abdul Qader said. The bridge’s discarded skeleton now pokes out of the riverbed.

“In the past, the water submerged the bridge. These days it barely covers what’s left of it,” he said.

Iranian officials say Iraq should be more worried about the impact of massive public works in Turkey such as the Ilisu Dam, which could take away much of the Tigris’ flow into Iraq, rather than Iran’s comparatively smaller irrigation projects.

“I don’t believe Iraqi complaints and calls for suing Iran are justifiable,” said Fadaei Fard, who works on water resources and flood management at the Iranian Ministry of Energy. “They have no legal standing in international courts because almost all projects carried out in Iran foresaw enough water inflows into Iraqi territory.”

Iranian state media have quoted officials dismissing Iraqi concerns as anti-Iran propaganda. The blame for Iraq’s problems, the state-run Islamic Republic News Agency said in one report, lies with Baghdad’s mismanagement and corruption, as well as low investment in Iraq’s infrastructure, which has been damaged by decades of war and neglect. Besides, with a population half that of Iran or Turkey, Iraq is relatively still better off than both of its neighbors.

Hamdani, the Iraqi water resources minister, acknowledged problems with water distribution but insisted that Tehran was “evading its responsibility.”

Azzam Wash, an environmental expert who was a member of Iraq’s delegation to the U.N. climate change conference in Scotland in November and a founder of the environmental group Nature Iraq, said that “suing Iran will not resolve the problem.”

“Assume for the sake of argument Iran accepts adjudication, and further assume Iraq wins, then what? Will Iran release water?” he said, adding that successive Iraqi governments had done little to reduce water waste.

Yassin, the pomegranate farmer, isn’t expecting any improvement in the situation either. He now has a state job as a maintenance engineer, joining others in Diyala abandoning their farms.

“For 80% of the people here, if someone came and gave them money, they would sell their land,” he said.

“They say, ‘Let me do something in the city. Farming is over.’”

Taylor Energy has agreed to pay more than $43 million in penalties and transfer a further $432 million to the Department of the Interior as a trust to complete the cleanup of the 17-year spill. (photo: AP)

Taylor Energy has agreed to pay more than $43 million in penalties and transfer a further $432 million to the Department of the Interior as a trust to complete the cleanup of the 17-year spill. (photo: AP)

Taylor Energy has agreed to pay more than $43 million in penalties and transfer a further $432 million to the Department of the Interior as a trust to complete the cleanup of the 17-year spill, the Department of Justice announced Wednesday.

“Offshore operators cannot allow oil to spill into our nation’s waters,” Assistant Attorney General Todd Kim for the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division said in a statement. “If an oil spill occurs, the responsible party must cooperate with the government to timely address the problem and pay for the cleanup. Holding offshore operators to account is vital to protecting our environment and ensuring a level industry playing field.”

The oil spill began in 2004 when Hurricane Ivan triggered the collapse of a Taylor Energy production platform located around 10 miles off the Louisiana coast in the Gulf of Mexico. The collapse damaged around two dozen oil wells, Reuters reported. All told, the ongoing spill has poured hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, according to The Hill.

“Despite being a catalyst for beneficial environmental technological innovation, the damage to our ecosystem caused by this 17-year-old oil spill is unacceptable,” U.S. Attorney Duane A. Evans for the Eastern District of Louisiana said in a statement. “The federal government will hold accountable businesses that violate our Nation’s environmental laws and ensure that any oil and gas company operating within our District meets their professional and legal responsibilities.”

The settlement resolves a years-long legal standoff between Taylor Energy and the government. Taylor Energy ceased operations in 2008 and set up a $666 million fund to clean the spill, The New York Times reported. However, it only capped nine of the 25 wells, saying the rest were too difficult to reach, and sued the Department of the Interior for the remaining funds. Since then, the company has continued to push back against the federal government over the costs of cleanup and the extent of the damage.

Wednesday’s agreement requires Taylor Energy to drop three lawsuits it has filed against the federal government and pay $432 billion into a trust to cap the remaining wells, shutter the facility and decontaminate the area. It will also liquidate its remaining assets, an amount of more than $43 billion, to pay civil penalties, removal costs and natural resources damages.

However, Taylor Energy does not "admit any liability to the United States or the State arising out of the MC-20 Incident,” The Hill reported.

The settlement has been filed as a proposed consent decree. It now waits on 40 days of public comment and court review.

“This settlement represents an important down payment to address impacts from the longest-running oil spill in U.S. history,” Nicole LeBoeuf, director of NOAA’s National Ocean Service, said in a statement. “Millions of Americans along the Gulf Coast depend on healthy coastal ecosystems.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment