Frantically Trying to Get Your Attention on Donations!

This is the worst December, year-end fundraiser we have ever seen. At this point in December of last year we had double the number of donations we have now. This amounts to a huge slashing of RSN’s budget.

We need reasonable support, very badly.

In earnest.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

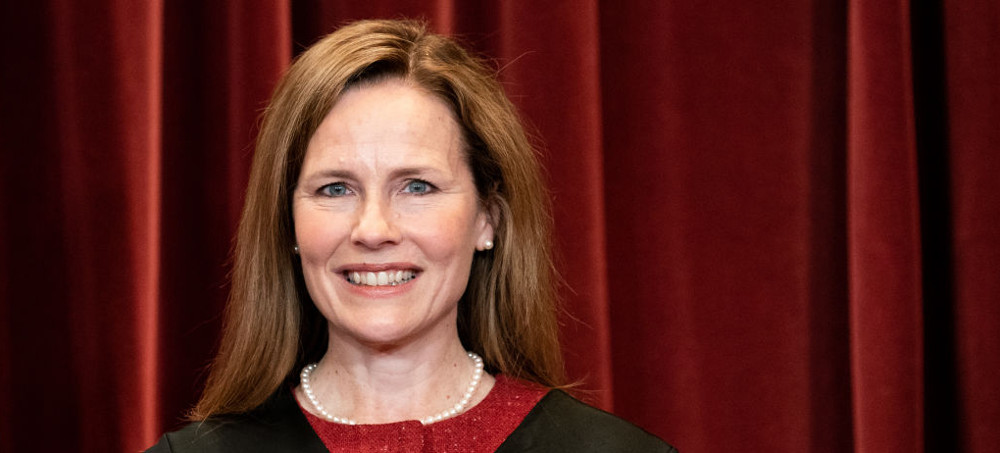

In her confirmation hearings, Amy Coney Barrett feigned ignorance of dark money groups. But she should be very familiar with such groups: new documents show that dark money bankrolled her Supreme Court nomination.

The new tax returns shed light on how Barrett’s successful, last-minute confirmation campaign was aided by a flood of dark money. They also reveal the rapid growth of Leo’s already highly successful dark money network and its tentacles in the broader conservative movement.

Corporate interests with access to nearly unlimited money have a huge stake in tilting the court to the right: in recent years, the court has played a pivotal role not only in swaying social policy, but also in shifting economic policy and corporate regulations. In Barrett’s first year, she has already sided with corporate interests on a landmark climate case involving an oil giant that employed her father for decades, and she refused to recuse herself in a donor transparency case involving a foundation tied to a dark money group that backed her confirmation.

“I Am Unaware of Any Outside Groups”

Leo is a longtime executive at the Federalist Society, a group for conservative lawyers. He formed the Rule of Law Trust (RLT) in 2018, and the group quickly raised nearly $80 million. RLT finally started spending that money in 2020, donating $21.5 million to the Judicial Crisis Network (JCN), another group steered by Leo that played a key role in Republicans flipping the Supreme Court and building a conservative supermajority.

JCN spent millions pressing Republican senators to block Barack Obama’s 2016 Supreme Court pick, Merrick Garland, and subsequently spent millions boosting each of Trump’s high court nominees — Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Barrett — all while Leo was advising Trump’s judicial strategy.

In 2017, when Barrett was nominated to serve on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, Senator Dick Durbin, Democrat from Illinois, asked her: “Do you want outside groups or special interests to make undisclosed donations to front organizations like the Judicial Crisis Network in support of your nomination?”

Barrett responded:

I am unaware of any outside groups or special interests having made donations on my behalf. I have not and will not solicit donations from anyone. Indeed, doing so would be a violation of my ethical responsibilities as a judicial nominee.

When Durbin asked whether she would “discourage donors from making such undisclosed donations” or “call for the donors to make their donations public,” Barrett referred him to her previous answer.

The 85 Fund

Leo also helps direct the 85 Fund, a charitable organization being used to fiscally sponsor a host of conservative nonprofits, including the Judicial Education Project, which has long been JCN’s sister arm.

The 85 Fund reported bringing in nearly $66 million in 2020, according to its latest tax return. That’s a huge increase over the roughly $13 million the organization raised in 2019, per OpenSecrets, which found the majority of the 85 Fund’s 2020 money came from DonorsTrust, a group known as a “dark money ATM,” for its use as a pass-through vehicle.

The 85 Fund donated big sums last year to groups that backed Barrett’s confirmation, including: Turning Point USA ($2.7 million), Job Creators Network ($500,000), Independent Women’s Forum ($310,000), the Susan B. Anthony List ($175,000), Concerned Women for America ($100,000), Faith and Freedom Coalition ($100,000), and Heritage Action for America ($50,000).

The 85 Fund disclosed donating to nearly four dozen conservative groups in 2020. It made a substantial donation — $5.6 million — to the Federalist Society, where Leo is a cochairman.

The organization gave $1 million to the New Civil Liberties Alliance, a group that fought in court to end the Joe Biden administration’s federal COVID-19 pandemic eviction ban. It contributed another $1 million to Passages Israel, a group known as “Christian birthright” for bringing American Christian students on trips to Israel.

The 85 Fund also donated $750,000 to RealClearFoundation, a conservative nonprofit tied to the political news aggregator RealClearPolitics. And it contributed $100,000 to the CO2 Coalition, a conservative climate denial group.

President Biden is willing to support 'whatever it takes' to pass voting legislation. (photo: Getty)

President Biden is willing to support 'whatever it takes' to pass voting legislation. (photo: Getty)

Driving the news: "If the only thing standing between getting voting rights legislation passed and not getting it passed is the filibuster, I support making an exception on voting rights for the filibuster," Biden said during an interview with ABC News Wednesday night.

Why it matters: Democratic calls to pass federal voting legislation have strengthened recently.

- In a letter to his colleagues this week, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D) said the Senate will consider voting rights legislation in January, and that the chamber would consider "changes to any rules" which stand in the way.

- Martin Luther King III has said there should be no celebration of MLK Day next month without the legislation.

Catch up quick: The House passed voting rights and election reform bills, but the legislation has been stuck in the Senate for months, Axios' Alexi McCammond writes.

Yes, but: Not all Senate Democrats, including Sen. Joe Manchin (WV) and Sen. Krysten Sinema (AZ), have backed the strategy.

Tamala Payne with attorney Sean Walton participate in a protest for the shooter of her, Casey Goodson Jr. (photo: Doral Chenoweth/AP)

Tamala Payne with attorney Sean Walton participate in a protest for the shooter of her, Casey Goodson Jr. (photo: Doral Chenoweth/AP)

Every week an officer kills someone during a traffic stop who is unarmed. The numbers for people of color are even more staggering.

The problem is that the victim, Casey Goodson Jr., was not the dangerous suspect that Meade was pursuing. Goodson, a 23-year-old Black man, was found dead in the doorway of his home with keys still in the lock and Subway sandwiches for his brother and grandmother. Goodson’s grandmother said he had just returned home.

Goodson, a licensed concealed carry permit holder, was armed at the time of the shooting. However, he was not under investigation for any crimes and did not have a criminal record. Meade said Goodson was brandishing a gun before he was shot. But community members say Meade’s shooting was unjustified, and Goodson's relatively clean record supports the assertion.

This seems to be the position of the grand jury in Columbus. On Dec. 2, nearly one year after the killing, Meade was indicted for two counts of murder and one charge of reckless homicide.

Goodson’s killing is among the many that add to the disturbing statistics about police killings and race in America.

White people are more than three times less likely to be killed by cops than Black people, according to a study conducted between 2013 and 2017 of metropolitan police departments.

Even more troubling, the racial statistics are worse when factoring in whether someone was unarmed – as Daunte Wright was when he was killed in Minnesota by former Brooklyn Center police officer Kim Potter. Potter is on trial for the killing. According to her, the incident happened because she mistakenly pulled her gun rather than her Taser.

Recent killings by officers, along with murder charges (such as those for Meade and Potter) and convictions (such as the conviction of Derek Chauvin for killing George Floyd) may give the impression that officers are often held accountable for unjustified killings. But less than 2% of officers are charged with murder despite the approximately 1,000 people killed in a police shooting on average every year.

Every week, a police officer kills someone during a traffic stop who does not have a weapon and is not under investigation for a violent crime.

Among Black men like Goodson, Wright and Floyd, the statistics are even more dire. Roughly “1 in every 1,000 (Black) men can expect to be killed by police,” according to a study published in 2019 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

And the risk of police violence peaks for people in their 20s and early 30s. For Black males, the risk window is even larger, starting during the teenage years and extending into the 40s. Floyd was 46.

Some people often try to justify police killings by pointing to violent crime. The problem is that research shows they seem to operate on different continuum. Moreover, they are much less related than people think. An analysis by Mapping Police Violence documents that cities with the highest levels of police violence are often not the same cities with the highest level of violent crime. Accordingly, it is important to decouple police violence from violent crime and realize they are two distinct social problems that need to be addressed.

However, police killings do impact local communities. Research shows that aggressive policing leads to worse mental and physical health outcomes for people living in overpoliced communities. Police use of force is also more likely to occur at left-wing protests than right-wing protests.

Area residents also pay for police violence with their tax money. Over a four-year period starting in 2015, the nation's largest police departments paid more than $2 billion for misconduct and other violations, according to The Wall Street Journal.

So, what explains police violence and racial disparities in use of force?

Research highlights that explicit and implicit racial bias as well as an over-reliance on a "warrior mindset" and use of force tactics explain police violence. Law enforcement recruits receive more than 50 hours of firearms training compared with fewer than 10 hours of de-escalation training. Recent technological advances, such as a training program created by Jigsaw – a virtual reality collaborative among the University of Maryland, the University of Cincinnati, Georgetown and Morehouse – provide opportunities for officers to train in safe environments.

Using advanced technology may start helping officers become more objective in their decision-making and use more communication to de-escalate.

The findings underscore one of the potential ways that Amazon could take advantage of federal tax subsidies. (photo: Getty)

The findings underscore one of the potential ways that Amazon could take advantage of federal tax subsidies. (photo: Getty)

The company has located delivery stations, fulfillment centers and even an air hub in regions that qualify for capital gains tax breaks under a 2017 law.

The company has located delivery stations, fulfillment centers and even an air hub in “opportunity zones,” regions across the country where investors can qualify for capital gains tax breaks under a 2017 law.

The initiative had bipartisan backing and was intended to incentivize investment in some of the most economically distressed regions of the country. But critics of the program have raised concerns that such programs further enrich wealthy investors and corporations for projects that would have happened without government assistance. And because there aren’t requirements that investors and corporations publicly report how they are using the tax breaks, it’s difficult to measure impact. Experts say it’s impossible to know if the program is having the intended effect of creating jobs and affordable housing — or simply exacerbating economic divides.

Amazon has opened 153 facilities in these zones since 2018, accounting for more than 15 percent of the warehouses that it has opened in that time period, according to the analysis from Good Jobs First, a policy resource center working with subsidy data, shared exclusively with The Washington Post. And 18 more facilities are scheduled to open in these areas in 2022 and 2023.

The findings underscore one of the potential ways that Amazon could take advantage of federal tax subsidies as it rapidly expands its delivery network. The company’s relatively low tax bills have been at the center of a political firestorm. The Good Jobs First researchers say the company has received at least $650 million in government subsidies this year, but that the expansion into opportunity zones highlights how the company could be receiving other tax breaks that are opaque to the public and difficult to track.

“More sunshine” is needed to better track the opportunity zone program, said Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good Jobs First.

Amazon spokeswoman Julia Lawless said the company hasn’t used the benefit in any of the 171 sites identified in the Good Jobs First analysis. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

“We may use the [opportunity zone] benefit on future acquired sites as Congress intended it to help jump-start local economies in the types of areas we are investing in and creating jobs,” she said.

She added that the company “does not actively seek out” locations in the zones.

“If we locate in one of these areas, it’s because of our site selection criteria — from available land to access to talent — aligns with tracts that governments, across all levels, have previously identified for economic development; not because we utilized the [opportunity zone] benefit,” she said.

Opportunity zones could be a boon to big companies like Amazon, that buy and sell many assets, leading to capital gains. Companies can invest those gains into projects in opportunity zones, allowing them to defer tax payments.

LeRoy says Amazon has been particularly aggressive in “garnering available tax breaks.” The Good Jobs First report argues the expansion into opportunity zones is part of a much broader pattern, where Amazon’s rapid growth has been bolstered through government subsidies. This push into potentially advantageous markets comes as federal policymakers are applying increasing scrutiny to the company. Lawmakers have introduced legislation that takes aim at Amazon’s alleged anticompetitive behavior, and President Biden has elevated some of the company’s most prominent critics, including Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan, to key regulatory roles.

Amazon has rapidly expanded amid an e-commerce boom, in part accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic. Good Jobs First estimates that Amazon has received $4.2 billion in U.S. subsidies, through property tax abatements, corporate income tax credits and even sales tax exemptions on building materials.

“You’ve got two functions of government fighting each other right now,” LeRoy said. “You’ve got state and local governments fueling this monopolistic grab in the retail space, accelerating the decline of brick-and-mortar retail. And you’ve got Uncle Sam finally smelling the coffee and realizing that maybe they have to look at the company through that lens.”

Amazon has a high-profile and controversial history of seeking government subsidies to expand its corporate footprint. In 2017, the company launched a nationwide search for its second headquarters. Faced with the promise of 50,000 high-paying jobs, cities aggressively competed to offer the company tax breaks and other incentives to attract the office. But after the company in 2018 announced it would split the new headquarters between Virginia and New York City, it faced broad blowback from liberal politicians, unions and community activists, who argued taxpayer dollars should not be used to further enrich a tech giant, and that the project would exacerbate income inequality in the city. The company ultimately dropped its plans to open the New York campus, amid the criticism that the tax incentives would take government resources away from other key programs, but pushed forward in Virginia.

However, unlike the high-profile headquarters search, the subsidies and incentives that Amazon receives for smaller local projects, like warehouses, data centers and offices, often fly under the radar.

The role of opportunity zones in fueling corporate growth is especially opaque, said David Wessel, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution. The tax law does not mandate public disclosure of who is using the opportunity zone program, and whether their projects are resulting in jobs or affordable housing. There have been some media reports about how individual investors have benefited from them, but less attention on how large corporations have used them.

That could be problematic if companies are using them to fund projects that do little to benefit or encourage job growth in the community, but garner them large tax breaks.

“It’s an unanswered question just how aggressive corporations are in the opportunity zone space,” he said.

Lawmakers, including Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr. (D-N.J.) have been calling for more robust reporting requirements around opportunity zones, especially in the wake of a Government Accountability Office report that found the IRS does not have the necessary data to evaluate the efficacy of the program. Pascrell also criticized the fact that there is no cap on the amount that investors can receive through the program.

“Nationwide, there is concern that the benefits are mostly flowing to those zones that were already ripe for development and could provide certain returns on investments,” Pascrell said at a recent hearing.

Political scrutiny of Amazon’s tax payments has escalated in recent years, especially after the company paid no federal taxes on profit of $11.2 billion in 2018. Democrats, including Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and Biden, repeatedly attacked the company for not paying its fair share of taxes during the presidential primary race. The company responded with an aggressive social media strategy, frequently tweeting at individual politicians.

“We pay every penny we owe,” the company said, saying the politicians’ complaints were about the U.S. tax code, not Amazon itself.

Panthers Anti-Racist union, a student activism group in the central York school district, protest the removal of books from school libraries. (photo: Panthers Anti-Racist Union)

Panthers Anti-Racist union, a student activism group in the central York school district, protest the removal of books from school libraries. (photo: Panthers Anti-Racist Union)

Narratives about race, gender and inequality are being banned around the US – but sales are rising as the frenzy appears to cause the opposite effect

One of the books targeted by name was 33 Snowfish, an acclaimed 2003 novel concerning a trio of runaway teens and all sorts of sordid, Kids-ish behavior. The concerned parents of northern Virginia believed that heady themes of poverty, addiction and abuse have no place in the sanctums of learning, and therefore, the book needed to go.

When Paul Cymrot heard about the meeting, he tracked down as many copies of 33 Snowfish as he could find. He soon discovered, ironically, that book was never really in the school library. 33 Snowfish is barely in print, and Cymrot tells me that it was an ebook version, lingering in some dusty corner of the school library servers, which sparked the initial animus.

The moral militancy immediately backfired, because Cymrot knows a good business opportunity when he sees one. He’s owned the Spotsylvania-area Riverby Books for 25 years, and possesses a shrewd nose for the ebbs and flows of the publishing market. One bookselling truth remains eternally undefeated, explains Cymrot. When a censorious zeitgeist swallows up a novel, a lot of people will want to buy it.

“It was not easy to find a box full of 33 Snowfish, but we did,” he continues. “We sold all that we bought, and we kept a couple as loaners because we wanted to make sure any students in the community could see what the fuss was about. There will always be some around.”

It’s now easier than ever to read 33 Snowfish in Spotsylvania county, subverting the rightwing siege on the supposed woke conspiracy infecting school libraries.

New ominous headlines about book bannings trickle in all the time. Just this month, Texas state representative Matt Krause pushed for the ousting of 850 books, including classics by Alan Moore and Margaret Atwood, from the public curriculum. A few days earlier, Parents in Kansas City barnstormed school conventions because they fear that their children might start internalizing the wisdom of Alison Bechdel or Angie Thomas. Two members of the board at the Spotsylvania meeting floated the idea of literally burning the offending titles, which would be an assault on both our precious norms and our precious subtext.

As always, the impetus of the mania is simple, stupid and cynical. The Republican party has made a concerted effort to bring outré philosophic principles like critical race theory to the heart of our politics, which is why the Virginia governor-elect, Glenn Youngkin, spent much of his time on the campaign trail griping about Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Parents took the bait, and overnight high school librarians – those brazen extremists pushing their anti-American agendas by cataloging Pulitzer winners from 1987 – were put in the crosshairs.

These books are rarely inflammatory or obscene; instead, they simply contain narratives about race, gender and inequality that chafe against prescribed American ideology. That’s more than enough for an emboldened conservative movement.

But there is no evidence that the wave of book bans are actually accomplishing their intended ambition. If anything they’ve achieved the opposite effect. Sales of Beloved increased after Youngkin transformed Morrison into a partisan figure, and Jerry Craft, an author and artist who found himself on the Krause list for his 2019 graphic novel New Kid, has spoken at length about how legislative suppression is an unlikely boon for his career. “What has happened is so many places have sold so many copies because now people want to see what all the hubbub is,” he said, in an interview with the Houston Chronicle. “They’re almost disappointed because there’s no big thing that they were looking for.”

In 2021, with countless different merchants all manacled together by an intercontinental supply chain, proscribing a novel is almost entirely ceremonial – more of a whinging fit than a genuine political project. The Nazis burned thousands of books after seizing Berlin in 1933. Today, if a constable comes looking to repossess your literature, a replacement copy can be delivered to your mailbox the next morning.

In fact, the booksellers I spoke to for this story all seemed eager to take on the government’s injunction as a spiritual challenge – almost like a test of their moral fortitude. Mark Haber, operations manager at Houston’s Brazos Bookstore, tells me his staff put up a display featuring a selection of the books evaporating from Texas school libraries. (Beloved and Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H-Mart are currently performing very well.) “We had a drive where people could buy a banned book as a donation for a free library somewhere in the city,” says Haber. “The bannings feel so organized. They aren’t targeting a specific book, they’re targeting ‘books’ in general.”

Brazos, of course, is part of Houston’s liberal enclave. There is a self-selection bias in his sales figures and customer clientele, which Haber happily admits. “It’s definitely a political stance,” he says. “We have customers who’ve maybe already read the book, and just want to buy it again.”

In fact, Cymrot tells me that he thinks that the book-ban sales bump is truly a bipartisan phenomenon. He notices a surge regardless of what party is currently relitigating the library. Earlier this year, when six of Dr. Seuss’ books left circulation due to some offensive caricatures in the pages, Riveryby thrived once again. “These paperbacks in our basement suddenly became collectibles,” he says.

At the very least, hopefully the censorship campaigns encourage kids to read more. I like the idea of enterprising teens wielding the Krause agenda like a summer reading list, checking off every title, one by one, until they’ve firmly opened their third eye.

One of the most heartening stories that surfaced from the hysteria occurred in York county, Pennsylvania, where local ordinances forbade teachers from using a swath of texts in their lesson plans last November. (The taxonomy was bizarre. Biographies of Aretha Franklin, Malala Yousafzai and Eleanor Roosevelt were put on ice.) High schoolers around the community roused to action – staging campus protests, canvassing the local papers and eventually winning a reversal of the policy in September.

Today, the confluence of students and teachers who overturned the ban are known as the Panthers Anti-Racist Union, named after the mascot of Central York high school. The group aims to continue their social justice advocacy into the future, which could soon result in much bolder action than the mealy proclivities of the local school board.

“We’ve always said this organization is about creating a safe space for everyone to talk about who they are, and what their struggles are. Not just in our school community, but in their lives,” says Edha Gupta, a senior at Central York high school and a member of the Panthers Anti-Racist Union. “Any healthy way for people to genuinely express how they’re feeling about these matters. We want a place for students to feel like they have the authority to speak up about what they’re passionate about.”

“I went through the list of the banned books and I thought they sounded great. My mom had a ton of them, I got others from random people,” says Olivia Pituch, another member of the union. “It’s funny, the ban made me more curious to see what they were about.”

U.S. soldiers stand guard behind barbed wire as Afghans sit on a roadside near the military part of the airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, on August 20, during the lead up to the complete withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan 10 days later. (photo: Wake Kohsar/Getty)

U.S. soldiers stand guard behind barbed wire as Afghans sit on a roadside near the military part of the airport in Kabul, Afghanistan, on August 20, during the lead up to the complete withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan 10 days later. (photo: Wake Kohsar/Getty)

It’s not just about China.

How could it be that even with those wars ending, Congress has authorized about $30 billion more than President Donald Trump’s last budget?

When the Cold War with Russia ended in the 1990s, military leaders acknowledged that spending could be halved while still maintaining security. President George H.W. Bush successfully slashed defense funding by 9 percent and then President Bill Clinton initially trimmed about 8 percent (or more, depending on the calculation). They sought to reinvest that money back home, in what was called the peace dividend. But Republican lawmakers also pushed back, and Clinton failed to really transform the military budget. Defense spending began climbing in the late ’90s, and then to much higher levels during the post-9/11 years.

In 2021, despite the US mostly leaving Iraq (2,500 troops remain) and Afghanistan, not even a slight peace dividend has materialized. “As we drew down from Afghanistan, we should have been having a real debate about whether there were opportunities to shift funding and make cuts,” said Mandy Smithberger of the Project on Government Oversight.

It’s a debate that Biden could have sparked. The idea of “building back better” appears about a dozen times in the White House’s interim security strategy, and Biden himself hinted at the potential for a peace dividend during the most chaotic days of the Afghanistan withdrawal in August. He framed the war as wasteful spending: “The American people should hear this: $300 million a day for two decades ... what have we lost as a consequence in terms of opportunities?” But he didn’t go further in reenvisioning how the US approaches its security and the world.

Not enough lawmakers have taken these issues up either, despite a pandemic that has shown the limits of a national security based on weapons systems and troops alone. A few progressive members of Congress were excited about redirecting money to the Build Back Better agenda. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA), who famously opposed the 2003 Iraq war, and 22 of her colleagues urged Biden in May to reset priorities after “as much as $50 billion will be freed up by withdrawing troops from Afghanistan.” So why did this not happen?

The short answer: The US national security establishment sees China as the most urgent threat of the moment, while the entrenched interests of the arms industry endure.

Put another way, although the US is no longer in Afghanistan, taxpayers continue to pay for the American military’s massive global presence. Absent a fundamental rethinking of how the US sees national security and the role the military plays in foreign policy, big cuts are unlikely.

“China, China, China”

Everyone in Washington is talking about “great power competition” or “strategic competition” with China — and given that (real or exaggerated) threat, no one in power is eager to cut the military budget.

“Within the national security community in DC, it’s really all China, China, China,” says defense budget expert Todd Harrison at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Congress didn’t think that Biden had committed enough to combatting China in his original defense budget request, so lawmakers added some $25 billion in all. Congress added $2 billion above Biden’s ask to the Pacific Deterrence Initiative for countering China in its own neighborhood, which brought that budget line to $7.1 billion. Fears surrounding China’s seapower has meant $4.7 billion more for shipbuilding and adding more than $3.5 billion for military base construction beyond what Biden requested.

Washington is particularly concerned about China’s new technological capabilities. Biden proposed a 5 percent boost to research and development; Congress then sprinkled in $5.7 billion more, which brings the military’s R…D pot to $117.7 billion.

Trump’s team articulated this hardline policy toward China in its 2018 national security strategy, building on Barack Obama’s so-called pivot to Asia, and now Biden is using that language and sense of urgency. “There’s been significant bipartisan buy-in to the idea that China is a major military threat. And I think that’s an exaggerated perspective, but it seems to be catching hold except for a minority of champions for reigning in the Pentagon budget,” said William Hartung of the Center for International Policy.

Across the political spectrum, politicians believe US power is contracting as China expands its global influence. Hostile rhetoric from Washington and Beijing has further inflated tensions, which have real-world implications. The US military is “arming itself for an actual war with China, particularly for a war over Taiwan,” says Harrison.

Still, skeptics of the new hawkishness around China warn that it’s unlikely that a conflict with China would take on the conventional forms of previous wars. Defense experts, like Smithberger, say that investment in education, technology, and supply-chain security will protect Americans much more from 21st century conflict than an arms race.

Some Democrats are even more skeptical, and believe the Biden administration is inflating the China threat. “This has nothing to do with any actual threats. It’s just feeding the beast. And until we have an administration or some meaningful number of legislators who would stand up to that beast, we’re just going to keep pouring money down this hole,” said a senior Democratic staffer in the Senate.

“Contractors are the biggest winners”

Almost no one wants to risk being seen as the person who cuts the defense budget: 88 senators voted in favor of the defense authorization for fiscal year 2022, and only 11 voted against. Over the past 60 years, the defense spending bill has passed each year with bipartisan support.

The military-industrial complex has been shaping Washington for almost a century. “Contractors are the biggest winners,” says Hartung of the Center for International Policy, who pointed out that about half the budget goes to contractors, who are outsourced to do everything from logistics to office support, intelligence work and private security. According to the Congressional Research Service, there are 464,500 full-time contractors working for the Defense Department.

The role of lobbying can’t be overstated. The defense industry spent $98.9 million lobbying so far in 2021, according to Open Secrets. Lockheed Martin, one of the largest five military companies in the country, has a presence in every state, a strategy that defangs critics.

There’s also the millions of dollars each year that military contractors donate to Washington think tanks. Many experts who regularly appear in the media are on “the defense industry dole,” according to the Intercept. Lawmakers who receive campaign donations from defense interests are more likely to vote to increase spending.

Even those acting in good faith could be swayed by persistent myths, like an overly strong belief in defense spending’s ability to create jobs. Yes, every dollar does create jobs somewhere. But because military investments are capital-intensive and much of the money is spent abroad, that defense spending creates fewer jobs than money going to other industries.

All of this, progressive critics say, leads to a budget process that looks like a Christmas Tree, with Congress members pinning on goodies to satisfy constituents that don’t fit into a larger, cohesive defense strategy.

“When something is set in motion it is often very hard to unseat that, and we have what I have called the military normal,” said anthropologist Catherine Lutz of Brown’s Costs of War Project.

The defense budget could be trimmed at the margins, but bigger change requires new thinking

The US is engaged in shadow conflicts across the globe, with more than 750 bases or installations in 80 countries. In the past year, special operations commandos deployed to 154 countries.

Take Afghanistan. Sure, the Pentagon will no longer be training and equipping Afghan forces at $3.8 billion a year. But US Central Command is still monitoring threats from potential terrorists, like ISIS affiliates, in the country. The US air war has moved out of Afghan bases and into bases in the broader Middle East and South Asia region.

Big cuts are possible. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) asked the Congressional Budget Office how to achieve a smaller military budget, and the nonpartisan federal agency came back with an option to gradually trim the budget over the next decade — and end up saving $1 trillion.

But most of Washington’s ideas are about snipping away at the margins or finding “efficiencies.”

On the campaign trail last year, Biden didn’t advocate for big cuts in military spending; the 2022 budget proposal he sent to Congress followed suit, trimming defense spending by 2 percent, with minor cuts to base construction and weapons purchases. The Pentagon’s number 2 leader, Kathleen Hicks, conceded in her Senate confirmation hearing, “there are ways for the Defense Department to be more efficient, to be more effective,” but such changes have not been forthcoming.

The military has proposed ideas to save money here and there as well. The Army, the Navy and the Air Force say that there are old weapons systems, unnecessary bases that could be closed, and older ships and planes could be put out of commission — in order to prioritize other costs. The Air Force, for example, has wanted to retire dozens of legacy attack planes known as the A-10, but Congress wouldn’t let that happen in this bill. “We’ve got to get rid of some of those aircraft so we can free up resources, and get on with modernization,” Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said recently.

Some conservatives, too, find this spending on out-of-date weapons and legacy projects to be wasteful. Mackenzie Eaglen of the American Enterprise Institute says that Congress, if it were building a defense program from scratch, could make the budget smaller and still keep Americans safe. Fiscal conservatives also talk about reforming the way the Pentagon purchases weapons and contracts out work, which as it stands leads to fraud, waste, and abuse.

“Why does it cost so much?” Eaglen said. “I get that. Even I am frustrated.”

Biden, like Clinton, has missed the chance for a peace dividend. After some initial posturing, Clinton never fully addressed the holdovers of the 20th century’s wars, and it seems Biden is falling into the same pattern. One analyst explained in 1995: “The most glaring weakness of the Clinton administration is that it is living with the defense budget of the now-dead Cold War era.” Now, Biden is living with the defense budget of the now-dead war on terrorism.

Kamila Rashid says an oil refinery now sits on what used to be her family's land. (photo: Lynzy Billing/Undark)

Kamila Rashid says an oil refinery now sits on what used to be her family's land. (photo: Lynzy Billing/Undark)

Decades of war, poverty, and fossil fuel extraction have devastated the country’s environment and its people.

Rashid was born here, like her parents before her and her children after her. She says when KAR moved into the area, residents traded their land for KAR’s promise of jobs and reliable, less expensive electricity for the village. The land was handed over, Rashid says, but she maintains that KAR never provided the promised electricity or long-term jobs.

The towers, also called flare stacks, are used by oil refineries across the globe to burn the byproducts of oil extraction. Such flaring releases a menagerie of hazardous pollutants into the air, including soot, also known as black carbon. “The smoke coats our skin and homes with black soot,” says Rashid. Many villagers keep their windows shut and try to remain indoors whenever possible.

Rashid’s neighbor, 29-year-old Bilah Tasim Mahmoud, joins her on the porch. The younger woman is holding a beat-up notebook with the names of women from Agolan who have miscarried. “No one is counting, but I am,” she says, flipping through the notebook’s pages. “We have had 300 miscarriages in this village since the oil field was developed,” she says, adding that she has been collecting this data but has no one official to take it to.

Miscarriages, of course, are common everywhere, and while pollution writ large is known to be deadly in the aggregate, linking specific health outcomes to local ambient pollution is a notoriously difficult task. Even so, few places on earth beg such questions as desperately as modern Iraq, a country devastated from the northern refineries of Kurdistan to the Mesopotamian marshes of the south — and nearly everywhere in between — by decades of war, poverty, and fossil fuel extraction.

As far back as 2005, the United Nations had estimated that Iraq was already littered with several thousand contaminated sites. Five years later, an investigation by The Times, a London-based newspaper, suggested that the U.S. military had generated some 11 million pounds of toxic waste and abandoned it in Iraq. Today, it is easy to find soil and water polluted by depleted uranium, dioxin and other hazardous materials, and extractive industries like the KAR oil refinery often operate with minimal transparency. On top of all of this, Iraq is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change, which has already contributed to grinding water shortages and prolonged drought. In short, Iraq presents a uniquely dystopian tableau — one where human activity contaminates virtually every ecosystem, and where terms like “ecocide” have special currency.

According to Iraqi physicians, the many overlapping environmental insults could account for the country’s high rates of cancer, birth defects, and other diseases. Preliminary research by local scientists supports these claims, but the country lacks the money and technology needed to investigate on its own. To get a better handle on the scale and severity of the contamination, as well as any health impacts, they say, international teams will need to assist in comprehensive investigations. With the recent close of the ISIS caliphate, experts say, a window has opened.

While the Iraqi government has publicly recognized widespread pollution stemming from conflict and other sources, and implemented some remediation programs, few critics believe these measures will be adequate to address a variegated environmental and public health problem that is both geographically expansive and attributable to generations of decision-makers — both foreign and domestic — who have never truly been held to account. The Iraqi Ministry of Health and the Kurdistan Ministry of Health did not respond to repeated requests for comment on these issues.

“Little priority has historically been given to the environmental dimensions of armed conflict, yet damage to the environment often echoes long into the future,” says Wim Zwijnenburg, who works for the Dutch peace organization PAX and has studied and written about the impact of war on the environment. He has investigated contamination in Iraq and says additional research is needed to clean up harmful toxins and mitigate health risks to people living in post-conflict regions.

The grim state of affairs is not lost on 27-year-old Idris Faroq, Rashid’s nephew, who works at the KAR refinery. (KAR also did not respond to multiple interview requests from Undark.) “If you travel to any village in Iraq, you will find contamination, radiation, and cancers,” he says. “This is the legacy of the American invasion and the wars that came before it — everyone left their waste behind.

“This land,” he added, “has been pillaged.”

Rashid’s family has grown wheat in Agolan for five generations, she says, but 15 years after the construction of the refinery, they are no longer able to support themselves as farmers. Rashid leaves her front porch to walk across the field that stands between her home and the facility. She says it’s the only land still owned by her family. “KAR uses the water from the river for their work and then they dump their waste,” she says, pointing at a pipe piercing through the exterior wall of the refinery. The waste flows directly into her family’s field, she says, and KAR also dumps its waste in the nearby river. The crops no longer grow, Rashid says, and anyway, the land “isn’t safe for agriculture now. And it isn’t safe for us.”

In Kurdistan, miles of pipelines shared with Turkish, Norwegian, and other international energy companies snake across the dry landscape, and the last decade has seen unregulated international, government, and militia oil refineries and oil fields pop up on contested lands, where drilling and flaring unfolds in close proximity to residential areas. Some facilities have been built within villages, expelling residents from their land and homes. People living near the refineries insist that they only started suffering from health ailments after the arrival of these companies and the pollution that came with them.

Rashid specifically mentions the fumes billowing from the flaring towers that surround her home, mindful that pollutants arising from flaring can increase myriad health risks for those living nearby. These towers were designed for the intentional burning of natural gas, a byproduct of pumping oil from the ground. While burning off the excess gas is technically better for the climate than merely venting it into the atmosphere, both have impacts on the climate — and more immediately on local health.

This past July, in an effort to address the issue, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s Ministry of Natural Resources issued a directive, giving oil companies 18 months to halt the flaring and instead seek ways to capture the gas and either reinject it underground, or use as an auxiliary power source. But this would mean additional costs for the companies, and it remains unclear whether the local industry has the technical and financial capacity to comply. And in any case, the government has little leverage to enforce the new policy — particularly given that the Iraqi economy is heavily dependent upon continued and robust oil exports, which account for more than 95 percent of state revenues.

As it stands, Iraq is the world’s sixth-largest oil producer. In 2020, the country ranked only behind Russia in the amount of gas flared, according to the World Bank, and air quality in the north — as with much of the country — can be relentlessly unhealthy to breathe.

The impacts are not only airborne. Roughly 100 miles northwest of Agolan is the Kwashe landfill, a monster dumpsite surrounded by agricultural land and, workers estimate, dozens of oil companies. Used for both domestic and industrial waste, the landfill is leaking oil and industrial waste into the surrounding environment. And like the residents of Agolan, those living in villages near Kwashe say they are suffering from an array of health problems, including migraines, fatigue, skin conditions, miscarriages, cancer, and respiratory problems such as shortness of breath and asthma.

“In Iraq, we often say that every family includes someone with cancer,” says 43-year-old Yasin Omar, who lives less than a mile from the landfill in the village of Moqeble. Omar used to work at an oil company himself until health problems arose. “This village is almost 60 years old and was here long before the oil companies moved in. There used to only be 10 companies here and now there are more than 100,” he says.

According to Omar, many residents have decided to relocate. Some left because they found it so difficult to breathe the polluted air. Others left after developing cancer. Local residents are in an impossible situation, he says, given that the oil companies and a nearby PVC factory provide some of the only employment opportunities. And according to Omar, workers in both places are falling ill. This includes Omar, who says he was diagnosed with cancer last year. His two children, he says, also suffer from health problems.

Cancer has been linked to an overall decline in the health of Iraqis since the 1990s, though precisely what’s driving it is under dispute. In the past, officials from the Iraqi Ministry of Health have said that cancer numbers were rising in large part due to the use of depleted uranium munitions during the 1991 Gulf War by the United States and British militaries. Both countries have disputed those claims.

That’s the problem, experts who study Iraq’s complex mosaic of pollution and health challenges say. Despite overwhelming evidence of pollution and contamination from a variety of sources, it remains exceedingly difficult for Iraqi doctors and scientists to pinpoint the precise cause of any given person’s — or even any community’s — illness; depleted uranium, gas flaring, contaminated crops all might play a role in triggering disease.

Absent international assistance, they say, answers will continue to be elusive. “We don’t have the facilities or equipment,” says Bassim Hmood, a cancer specialist in Al Nasiriyah in southern Iraq, “to test the causes of the cancers.”

Roughly 250 miles south of Agolan, a pediatrician named Eman navigates the bustling, narrow corridors of Baghdad’s Central Pediatric Teaching Hospital. (Eman would only provide her last name to Undark and attempts to follow up with her were unsuccessful.) It’s an August morning and the waiting areas outside the wards are full. Eman stops for a moment to direct a patient to the proper room then pulls a pen from her white physician’s coat to sign a form for another. It’s technically her lunch break, but it’s busy on the ward today. She will work through lunch.

This is Eman’s sixth year at the hospital, and her 25th as a physician. Over that time span, she says, she has seen an array of congenital anomalies, most commonly cleft palates, but also spinal deformities, hydrocephaly, and tumors. At the same time, miscarriages and premature births have spiked among Iraqi women, she says, particularly in areas where heavy U.S. military operations occurred as part of the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 to 2011 Iraq War.

Research supports many of these clinical observations. According to a 2010 paper published in the American Journal of Public Health, leukemia cases in children under 15 doubled from 1993 to 1999 at one hospital in southern Iraq, a region of the country that was particularly hard hit by war. According to other research, birth defects also surged there, from 37 in 1990 to 254 in 2001.

But few studies have been conducted lately, and now, more than 20 years on, it’s difficult to know precisely which factors are contributing to Iraq’s ongoing medical problems. Eman says she suspects contaminated water, lack of proper nutrition, and poverty are all factors, but war also has a role. In particular, she points to depleted uranium, or DU, used by the U.S. and U.K. in the manufacture of tank armor, ammunition, and other military purposes during the Gulf War and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The United Nations Environment Program estimates that some 2,000 tons of depleted uranium may have been used in Iraq, and much of it has yet to be cleaned up. The remnants of DU ammunition are spread across 1,100 locations — “and that’s just from the 2003 invasion,” says Zwijnenburg, the Dutch war-and-environment analyst. “We are still missing all the information from the 1991 Gulf War that the U.S. said was not recorded and could not be shared.”

Souad Naji Al-Azzawi, an environmental engineer and a retired University of Baghdad professor, knows this problem well. In 1991, she was asked to review plans to reconstruct some of Baghdad’s water treatment plants, which had been destroyed at the start of the Gulf War, she says. A few years later, she led a team to measure the impact of radiation on soldiers and Iraqi civilians in the south of the country.

Around that same time, epidemiological studies found that from 1990 to 1997, cases of childhood leukemia increased 60 percent in the southern Iraqi town of Basra, which had been a focal point of the fighting. Over the same time span, the number of children born with severe birth defects tripled. Al-Azzawi’s work suggests that the illnesses are linked to depleted uranium. Other work supports this finding and suggests that depleted uranium is contributing to elevated rates of cancer and other health problems in adults, too.

Today, remnants of tanks and weapons line the main highway from Baghdad to Basra, where contaminated debris remains a part of residents’ everyday lives. In one family in Basra, Zwijnenburg noted, all members had some form of cancer, from leukemia to bone cancers.

To Al-Azzawi, the reasons for such anomalies seem plain. Much of the land in this area is contaminated with depleted uranium oxides and particles, she said. It is in the water, in the soil, in the vegetation. “The population of west Basra showed between 100 and 200 times the natural background radiation levels,” Al-Azzawi says.

Some remediation efforts have taken place. For example, says Al-Azzawi, two so-called tank graveyards in Basra were partially remediated in 2013 and 2014. But while hundreds of vehicles and pieces of artillery were removed, these graveyards remain a source of contamination. The depleted uranium has leached into the water and surrounding soils. And with each sandstorm — a common event — the radioactive particles are swept into neighborhoods and cities.

Cancers in Iraq catapulted from 40 cases among 100,000 people in 1991 to at least 1,600 by 2005.

In Fallujah, a central Iraqi city that has experienced heavy warfare, doctors have also reported a sharp rise in birth defects among the city’s children. According to a 2012 article in Al Jazeera, Samira Alani, a pediatrician at Fallujah General Hospital, estimated that 14 percent of babies born in the city had birth defects — more than twice the global average.

Alani says that while her research clearly shows a connection between contamination and congenital anomalies, she still faces challenges to painting a full picture of the affected areas, in part because data was lacking from Iraq’s birth registry. It’s a common refrain among doctors and researchers in Iraq, many of whom say they simply don’t have the resources and capacity to properly quantify the compounding impacts of war and unchecked industry on Iraq’s environment and its people. “So far, there are no studies. Not on a national scale,” says Eman, who has also struggled to conduct studies because there is no nationwide record of birth defects or cancers. “There are only personal and individual efforts.”

“Every U.S. base had a burn pit,” Salam Alzaidi says bluntly, taking a seat in a cafe on the outskirts of Baghdad. Between 2009 and 2010, he worked at bases across Iraq as a program manager for L3 Harris Technologies, an American aerospace and defense company.

During the Iraq War, U.S. military bases used burn pits as a way to dispose of an array of industrial, military, and medical waste, which was variously comprised of paint, plastics, used medical supplies, electronics, spent munitions, petroleum products, lubricants, rubber, and an array of other items, including human waste. The refuse was burned in open pits, sometimes along with unexploded ordnance — an ostensibly “controlled detonation.” According to reports, at just one base, Balad Air Base, the U.S. military burned an estimated 140 tons of waste a day in open air pits.

The burning of such material created clouds of black smoke made up of numerous pollutants, including particulate matter and dioxins like a chemical weapon called hexachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. “Even though these were controlled detonations, they would leave the whole area contaminated,” says Alzaidi. “These were huge detonations, and many bases are located near residential and agricultural areas.”

(The actual number of bases with burn pits is contested, but the U.S. military has only publicly identified around 40. In an email to Undark, Richard Kidd, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Defense for Environment and Energy Resilience, acknowledged that the military still had nine active burn pits at bases throughout the Middle East and Afghanistan, though he did not respond to other questions regarding contamination or Iraqi residents’ claims of health problems related to burn pits.)

Alzaidi says he worried about the health of residents living close to the bases. He recalls a time in 2006 — before he started working on the burn pits — when military waste was burned at a base in Anbar and the U.S. military used speakers to warn locals not to drink the water in their village for a week. “They just said, ‘do not drink this water,’ but did not explain why,” says Alzaidi. He says that most of the locals didn’t understand what was said through the speakers, and those who did were uncertain about how, exactly, the water was contaminated. Many drank the water anyway.

After the Gulf War, many veterans suffered from a condition now known as Gulf War syndrome. Though the causes of the illness are to this day still subject to widespread speculation, possible causes include exposure to depleted uranium, chemical weapons, and smoke from burning oil wells. More than 200,000 veterans who served in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere in the Middle East have reported major health issues to the Department of Veterans Affairs, which they believe are connected to burn pit exposure. Last month, the White House announced new actions to make it easier for such veterans to access care.

Numerous studies have shown that the pollution stemming from these burn pits has caused severe health complications for American veterans. Active duty personnel have reported respiratory difficulties, headaches, and rare cancers allegedly derived from the burn pits in Iraq and locals living nearby also claim similar health ailments, which they believe stem from pollutants emitted by the burn pits.

Keith Baverstock, head of the Radiation Protection Program at the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Europe from 1991 to 2003, says the health of Iraqi residents is likely also at risk from proximity to the burn pits. “If surplus DU has been burned in open pits, there is a clear health risk” to people living within a couple of miles, he says.

Abdul Wahab Hamed lives near the former U.S. Falcon base in Baghdad. His nephew, he says, was born with severe birth defects. The boy cannot walk or talk, and he is smaller than other children his age. Hamed says his family took the boy to two separate hospitals and after extensive work-ups, both facilities blamed the same culprit: the burn pits. Residents living near Camp Taji, just north of Baghdad also report children born with spinal disfigurements and other congenital anomalies, but they say that their requests for investigation have yielded no results.

More than a dozen rivers snake through Iraq, tributaries of the mighty Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which flow into the Mesopotamian Marshes, also known as the Iraqi Marshes, a wetland area located in the southern part of the country. Once, the marshes were a literal oasis in the desert, but now they are a thirsty expanse. Sun scorched grasslands lead the way to what is left of the dried-out marshes. These marshes are not only wracked by evaporation, they are also badly polluted with the black wastewater carried in from sewage pipes that connect back with the region’s heavy industry.

Azhar Al-Asadi, a 31-year-old member of Save the Tigris organization and a water environmentalist, stands outside his home nestled on the corner of a quiet street. In the crook of his arm is his masters thesis on pollution in the nearby marshes. He keeps his hands stuffed inside his pockets, only removing them briefly to wipe sweat from his brow. It is a stifling 123 degrees Fahrenheit, and there’s not a whip of wind to offer any respite.

“The land here is starved of water,” says Al-Asadi. “The little water we have is heavily polluted and contaminated. Everything living is dying — plants, animals, and humans. There needs to be a concrete plan for sustaining everyday life on this land. Iraq needs to work towards environmental sustainability,” he says. “But these marshes are being abandoned. They are a dumping ground.”

Al-Asadi, like his father before him, was born and has spent his entire life in the town of Al-Chibayish in Dhi Qar Governorate, in southern Iraq, where the family once enjoyed fishing the meandering waterways. “I love this region,” he says, now standing beside his boat and looking out across the marshes that stretch to the horizon in every direction. The water is undisturbed, barely rocking Al-Asadi’s boat. The tall marsh grass lining the narrow waterways barely quivers in the still heat.

“I remember fishing here with my father as a young boy, but look at it now: the fish are already dead, floating on top of the water,” he says, pointing out a pile of fish floating in stagnant green water near a sewage point. It’s a familiar complaint in and around the marshes. Iraq’s environmental crisis bears heavily on the Euphrates and the Tigris, which provide nearly all the water to the country. Contamination in both waterways and their many tributaries is rife — byproducts of decades of both inadvertent and deliberate destruction.

During the war with Iran, which spanned the 1980s, former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein accused the region’s Indigenous inhabitants, known collectively as Marsh Arabs, of treachery. He dammed and drained Iraq’s iconic marshes to flush out rebels hiding in the reeds. By 2001, the wetlands were less than 7 percent of their size, according to estimates in a United Nations Environment Program report. Though the marshes had been partially restored since then, they are now dwindling once again.

Then, at the start of the Iraq War, the Tuwaitha Nuclear Research Center — known colloquially as the “yellowcake factory” — was looted. Barrels of radioactive waste were emptied in and around the facility just outside Baghdad. Some of the barrels containing uranium were stolen and dumped in rivers and barrels were found and used by people in the surrounding villages to preserve water and food, not knowing they were contaminated, says Al-Azzawi. Local residents were additionally exposed via contaminated dust.

Now Iraq’s waterways face a new threat. Seventy percent of Iraq’s industrial waste is being dumped directly into rivers or the sea, according to researchers. Harry Istepanian, senior fellow at the Iraq Energy Institute, says that the rivers and crisscrossed canals leading off the marshes in southern Iraq are highly contaminated with industry waste, sewage, pesticides, sunken ships, and other military debris that have sat at the bottom of the waterways since the 1980s.

Ships seemingly covered in rust can be seen half submerged in water around the marshes, he says. Many of them “still hold oil products, unexploded ordnance, and possibly rocket fuel, propellants, and toxic chemicals” and may still be leaking, he wrote in an email to Undark. “There are still more than 260 sunken ships — including tankers, tugs, barges, and patrol boats,” he continued, which clog the waters and, if dredged, might cause additional water pollution.

A 2019 U.N. Environment Program report noted that old and poorly maintained oil pipelines across the country were leading to spillages that were having a significant impact on the health of Iraqi communities as well as natural ecosystems. Istepanian says several of these spillages were near the Basra Shuaiba refinery’s wastewater infrastructure. A 2016 study published in the Engineering and Technology Journal analyzed dozens of water samples over a six month period. The authors found extreme levels of water pollution in the vicinity of the refinery and downstream of the Shatt Al-Basra river into which the refinery’s wastewater is dumped. In 2019, Human Rights Watch warned that the high salinity of Shatt Al-Arab river in Basra will cause serious environmental and health problems.

“Shatt-al-Arab and its canals,” Istepanian says, are “a stream of toxic waste.” There is fear that the 2018 water crisis might happen again. That summer, at least 118,000 people were hospitalized due to symptoms doctors identified as related to water quality, he says. And the soil contamination and air pollution from expanding oil fields and gas flaring are infiltrating area aquifers. “The polluted groundwater is now becoming extremely difficult and costly to make it safe, and it may be unusable for decades,” he adds.

Al-Asadi studied two of six sewage points in Al-Chibayish for his 2019 masters thesis. He collected samples in 2018 and 2019 and worked to identify the degree of pollution they are producing. “One sewage station alone will reach 1,200 square meters of the marshes per hour,” he says. “My study clearly showed that these sewage stations produce pollution which is harmful to human beings, animals, and plants.”

There is no upstream filtration system, Al-Asadi says, which means waste from hospitals, industry, and more “is going straight into the marshes.” Throughout his research, he has collected samples from the waterways in Chibayish and found the water to contain high levels of harmful toxins such as phosphorus, ammonium, and nitrate. “The water belongs to everyone, and yet it is not safe for anyone,” he says. His findings, which published in 2020, match up with previous work in the area. For instance, in 2011, a team of Iraqi scientists reported the same pollutants in the waterways in the Journal of Environmental Protection. Other research has found heavy metals and hydrocarbons in the marshes, and confirmed the high levels of salinity.

Al-Asadi says he can measure the radiation and pollution in the marshes, but Iraq only has basic equipment for testing and so the samples must be sent outside of the country, a lengthy and expensive process. But despite the challenges, he says, he will continue his research to raise public awareness about the pollution.

“The government, civil society organizations, and the public are doing nothing to prevent the pollution or find alternatives,” says Al-Asadi.

“I showed my findings to Iraqi government officials but they just ignored my studies. They are responsible to prevent more pollution or at least transfer these companies to remote areas. If they don’t, the conditions will deteriorate further and then we will be at the point where we can no longer amend the situation.”

In 2020, the U.N. Environment Program announced initiatives to address the steep environmental challenges in Iraq. That September, for instance, the organization announced a partnership with the Iraqi government to spend $2.5 million to help the country adapt to climate change. One month later, the U.N. Environment Program and the U.N. Development Program in Iraq signed an agreement to accelerate their environmental goals, which the organizations aim to hit by 2030, including addressing pollution and waste management.

In a press release, Zena Ali Ahmad, resident representative of the U.N. Development Program in Iraq, said: “Iraq faces a number of environmental challenges — from water scarcity, to rising temperatures, to pollution, to environmental degradation due to years of conflict and neglect. Tackling these challenges in a complex setting like Iraq cannot be done alone.” (The U.N. Environment Program did not respond to multiple interview requests.)

Meanwhile, the toll of the country’s longstanding environmental devastation continues.

Back in Agolan village in Kurdistan, the KAR Group has begun flaring again. To Idris Faroq, Rashid’s nephew, it’s just another insult in a land scarred by generations of combat and unchecked greed – both foreign and domestic. “Meanwhile,” he says, “there is nothing left for us.”

Rashid suggests there is one thing left behind: illness. Standing in the former wheat field near her home, she gazes at the raging flames towering several stories above her. She has to shout to be heard above rumbling noise of the flaring gas.

“Everyone here is sick,” she says. “When I’m trying to breathe, it’s like I’m dying.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment