Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Wealth inequality has spiraled out of control. It’s time to end this vicious cycle.

Wealth inequality is eating this country alive. We’re now in America’s second Gilded Age, just like the late 19th century when a handful of robber barons monopolized the economy, kept wages down, and bribed lawmakers.

While today’s robber barons take joy rides into space, the distance between their gargantuan wealth and the financial struggles of working Americans has never been clearer. During the first 19 months of the pandemic, U.S. billionaires added $2.1 trillion dollars to their collective wealth and that number continues to rise.

And the rich have enough political power to cut their taxes to almost nothing — sometimes literally nothing. In fact, Jeff Bezos paid no federal income taxes in 2007 or in 2011. By 2018, the 400 richest Americans paid a lower overall tax rate than almost anyone else.

But we can not solve this problem unless we know how it was created in the first place.

Let’s start with the basics.

I. The Basics

Wealth inequality in America is far larger than income inequality.

Income is what you earn each week or month or year. Wealth refers to the sum total of your assets — your car, your stocks and bonds, your home, art — anything else you own that’s valuable.Valuable not only because there’s a market for it — a price other people are willing to pay to buy it — but because wealth itself grows.

As the population expands and the nation becomes more productive, the overall economy continues to expand. This expansion pushes up the values of stocks, bonds, rental property, homes, and most other assets. Of course recessions and occasional depressions can reduce the value of such assets. But over the long haul, the value of almost all wealth increases.

Lesson: Wealth compounds over time.

Next: personal wealth comes from two sources.The first source is the income you earn but don’t spend. That’s your savings. When you invest those savings in stocks, bonds, or real property or other assets, you create your personal wealth — which, as we’ve seen, grows over time.

The second source of personal wealth is whatever is handed down to you from your parents, grandparents, and maybe even generations before them — in other words, what you inherit.

Lesson: Personal wealth comes from your savings and/ or your inheritance.

II. Why the wealth gap is exploding

The wealth gap between the richest Americans and everyone else is staggering.

In the 1970s, the wealthiest 1 percent owned about 20 percent of the nation’s total household wealth. Now, they own over 35 percent.

Much of their gains over the last 40 years have come from a dramatic increase in the value of shares of stock.

For example, if someone invested $1,000 in 1978 in a broad index of stocks — say, the S…P 500 — they would have $31,823 today, adjusted for inflation.

Who has benefited from this surge? The richest 1 percent, who now own half of the entire stock market. But the typical worker’s wages have barely grown.

Most Americans haven’t earned enough to save anything. Before the pandemic, when the economy appeared to be doing well, almost 80 percent were living paycheck to paycheck.

Lesson: Most Americans don’t make enough to save money and build wealth.

So as income inequality has widened, the amount that the few high-earning households save — their wealth — has continued to grow. Their growing wealth has allowed them to pass on more and more wealth to their heirs.

Take, for example, the Waltons — the family behind the Walmart empire — which has seven heirs on the Forbes billionaires list. Their children, and other rich millennials, will soon consolidate even more of the nation’s wealth. America is now on the cusp of the largest intergenerational transfer of wealth in history. As wealthy boomers pass on, somewhere between $30 to $70 trillion will go to their children over the next three decades.

These children will be able to live off of this wealth, and then leave the bulk of it — which will continue growing — to their own children … tax-free. After a few generations of this, almost all of America’s wealth could be in the hands of a few thousand families.

Lesson: Dynastic wealth continues to grow.

III. Why wealth concentration is a problem

Concentrated wealth is already endangering our democracy. Wealth doesn’t just beget more wealth — it begets more power.

Dynastic wealth concentrates power into the hands of fewer and fewer people, who can choose what nonprofits and charities to support and which politicians to bankroll. This gives an unelected elite enormous sway over both our economy and our democracy.

If this keeps up, we’ll come to resemble the kind of dynasties common to European aristocracies in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

Dynastic wealth makes a mockery of the idea that America is a meritocracy, where anyone can make it on the basis of their own efforts. It also runs counter to the basic economic ideas that people earn what they’re worth in the market, and that economic gains should go to those who deserve them.

Finally, wealth concentration magnifies gender and race disparities because women and people of color tend to make less, save less, and inherit less.

The typical single woman owns only 32 cents of wealth for every dollar of wealth owned by a man. The pandemic likely increased this gap.

The racial wealth gap is even starker. The typical Black household owns just 13 cents of wealth for every dollar of wealth owned by the typical white household. The pandemic likely increased this gap, too.

In all these ways, dynastic wealth creates a self-perpetuating aristocracy that runs counter to the ideals we claim to live by.

Lesson: Dynastic wealth creates a self-perpetuating aristocracy.

IV. How America dealt with wealth inequality during the First Gilded Age

The last time America faced anything comparable to the concentration of wealth we face today was at the turn of the 20th century. That was when President Teddy Roosevelt warned that “a small class of enormously wealthy and economically powerful men, whose chief object is to hold and increase their power” could destroy American democracy.

Roosevelt’s answer was to tax wealth. Congress enacted two kinds of wealth taxes. The first, in 1916, was the estate tax — a tax on the wealth someone has accumulated during their lifetime, paid by the heirs who inherit that wealth.

The second tax on wealth, enacted in 1922, was a capital gains tax — a tax on the increased value of assets, paid when those assets are sold.

Lesson: The estate tax and the capital gains tax were created to curb wealth concentration.

But both of these wealth taxes have shrunk since then, or become so riddled with loopholes that they haven’t been able to prevent a new American aristocracy from emerging.

The Trump Republican tax cut enabled individuals to exclude $11.18 million from their estate taxes. That means one couple can pass on more than $22 million to their kids tax-free. Not to mention the very rich often find ways around this tax entirely. As Trump’s former White House National Economic Council director Gary Cohn put it, “only morons pay the estate tax.”

What about capital gains on the soaring values of wealthy people’s stocks, bonds, mansions, and works of art? Here, the biggest loophole is something called the “stepped-up basis.” If the wealthy hold on to these assets until they die, their heirs inherit them without paying any capital gains taxes whatsoever. All the increased value of those assets is simply erased, for tax purposes. This loophole saves heirs an estimated $40 billion a year.

This means that huge accumulations of wealth in the hands of a relatively few households can be passed from generation to generation untaxed — growing along the way — generating comfortable incomes for rich descendants who will never have to work a day of their lives. That’s the dynastic class we’re creating right now.

Lesson: The estate tax and the capital gains tax have been gutted.

Why have these two wealth taxes eroded? Because, as America’s wealth has concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the wealthy have more capacity to donate to political campaigns and public relations — and they’ve used that political power to reduce their taxes. It’s exactly what Teddy Roosevelt feared so many years ago.

V. How to reduce the wealth gap

So what do we do? Follow the wisdom of Teddy Roosevelt and tax great accumulations of wealth.

The ultra-rich have benefited from the American system — from laws that protect their wealth, and our economy that enabled them to build their fortunes in the first place. They should pay their fair share.

The majority of Americans, both Democrats and Republicans, believe the ultra rich should pay higher taxes. There are many ways to make them do so: closing the stepped up basis loophole, raising the capital gains tax, and fully funding the Internal Revenue Service so it can properly audit the wealthiest taxpayers, for starters.

Beyond those fixes, we need a new wealth tax: a tax of just 2 percent a year on wealth in excess of $1 million. That’s hardly a drop in the bucket for centi-billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, but would generate plenty of revenue to invest in healthcare and education so that millions of Americans have a fair shot at making it.

One of the most important things you as an individual can do is take the time to understand the realities of wealth inequality in America and how the system has become rigged in favor of those at the top — and demand your political representatives take action to unrig it.

Wealth inequality is worse than it has been in a century – and it has contributed to a vicious political-economic cycle in which taxes are cut on the top, resulting in even more concentration of wealth there – while everyone else lives under the cruelest form of capitalism in the world.

We must stop this vicious cycle — and demand an economy that works for the many, not one that concentrates more and more wealth in the hands of a privileged few.

US soldiers inspect the site where an Iranian missile hit an air base in Iraq in January 2020. (photo: John Davidson/Reuters)

US soldiers inspect the site where an Iranian missile hit an air base in Iraq in January 2020. (photo: John Davidson/Reuters)

In the weeks after the attack, the Trump administration sought to diminish the injuries troops had suffered. It wasn't until more than a month after the attack that the Pentagon acknowledged that more than 100 troops had suffered traumatic brain injuries from the 13 missiles that slammed into the base.

About 80 troops involved in the attack submitted paperwork for the Purple Heart, the medal awarded to troops killed or wounded by enemy action. Of those 80 troops, the military awarded 30 Purple Hearts.

Col. Gregory Fix, the commander at the time, submitted Purple Heart paperwork for 56 soldiers in January 2020.

"Before submission, I conducted an extensive review of each Purple Heart award package to ensure compliance ... My Brigade Surgeon, Colonel Jonson, who personally treated each Soldier injured in the attacks, also reviewed each medical record to ensure all injuries were properly documented," Fix wrote last month in a memo obtained by USA TODAY. He said he was told to issue four of 23 Purple Hearts in February 2020 but was instructed not to inquire about or resubmit the awards for the other 33 soldiers.

The Army now anticipates receiving 39 more submissions for Purple Heart medals and will process them under existing regulations, Lt. Col. Gabe Ramirez, an Army spokesman, said on Tuesday.

“The U.S. Army’s Human Resources Command recently received a number of Purple Heart nominations related to the Jan. 8, 2020 Al Asad Air Base attack," Ramirez said in a statement. "HRC routinely processes award nominations submitted from units, soldiers, veterans and family members from as far back as (World War I)."

Beyond its symbolism, the Purple Heart carries entitlements that include priority health care upon retirement from the Veterans Affairs Department, preferences in hiring for federal jobs and eligibility for burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

A soldier who suffered a brain injury and an official who surveyed the damage described the missile attack as intense and a miracle that it didn't kill any troops. But it has left the soldier and others with injuries that linger nearly two years later. Both the soldier and official say commanders discouraged wounded troops from filing paperwork for the Purple Heart.

Invisible wounds

At the time, President Donald Trump was dismissive when asked about the wounds during a news conference.

"I don’t consider them very serious injuries, relative to other injuries that I’ve seen," Trump said after the attack. "No, I do not consider that to be bad injuries."

Complicating the issue is the nature of traumatic brain injuries, which are not as obvious as a lost limb from a bomb explosion. Brain injuries may qualify troops for a Purple Heart when the injuries are documented by a medical officer. But even the Pentagon struggles to count the wound accurately, according to a recent inspector general report, which found estimates still vary as to how many troops suffered brain injuries in the attack.

A statement from U.S. Central Command in 2020 noted that traumatic brain injuries do not automatically qualify troops for the award and the process for determining eligibility "was designed to be a fair and impartial proceeding that evaluated each case in accordance with applicable regulations."

Revenge for Soleimani, a soldier's goodbye to his daughter

The missile attack from Iran followed the Jan. 2, 2020, U.S. drone strike near Baghdad's airport that killed Gen. Qasem Soleimani, leader of Iran's elite Quds Force, part of the country's hard-line paramilitary Revolutionary Guard Corps. U.S. officials characterized his killing as defensive, saying Soleimani had been planning attacks on American diplomats and troops.

Iran responded six days later by firing ballistic missiles at Ain al-Asad base in western Iraq where hundreds of U.S. troops had been stationed. Intelligence reports had given U.S. troops hours of advance notice that the missile attack was coming, according to a soldier who was not authorized to speak publicly about the attack or the wounds he suffered.

The soldier had been writing a farewell letter to his daughter when the alarm sounded that missiles would strike within minutes. The first volley of three rounds rocked his building, enveloping everybody in dust, he said.

The explosions broke windows more than a mile away from the missiles' impact, according to a Defense official, who also was not authorized to speak publicly. It was a miracle that nobody was killed even with the advance warning, the official said. Unlike smaller rocket attacks launched by Iranian-backed militias on U.S. bases in Iraq, the blast from theater missiles sent dangerous shock waves across the base, the official said.

The days after the attack were fraught and busy, the soldier at Ain al Asad recalled. Worry persisted that Iran could attack again, the U.S. could launch a retaliatory strike, or that Iraq would rescind its welcome, requiring U.S. troops to evacuate immediately. The soldier and others returned to duty despite suffering headaches. He was told later that not being treated immediately meant that he and several others wouldn't qualify for the award.

The soldier and some of his colleagues continued to experience headaches, anger issues and slurred speech, he said. Yet doctors and commanders were reluctant to categorize them as wartime casualties, he said, and discouraged him from filing the necessary paperwork.

A board convened by the task force overseeing operations in Iraq determined who qualified for the Purple Heart from the attack.

Further muddying the issue is confusion within the Pentagon about how many troops suffered brain injuries in the attack. Central Command reported that 110 troops had brain injuries, while a separate office that tracks such wounds counted 87 troops with the wound from the same attack, according to the Defense Department's Inspector General.

The soldier, who in his 30s continues to take medication for his brain injury, said receiving the Purple Heart would signify formal recognition that he was wounded in combat and help make things right.

Rioters take to the steps of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. An NPR analysis found more Capitol riot defendants may have ties to the Oath Keepers, a far-right group, than was previously known. (photo: Kent Nishimura/Getty)

Rioters take to the steps of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. An NPR analysis found more Capitol riot defendants may have ties to the Oath Keepers, a far-right group, than was previously known. (photo: Kent Nishimura/Getty)

The Oath Keeper records were obtained from the nonprofit organization Distributed Denial of Secrets. The organization describes itself as a "transparency collective" and has publicized a variety of leaked material. Included in the Oath Keepers leak were chat logs, emails and a list of nearly 40,000 names and contact information for members. Many of the people whose information appears in the Oath Keepers leak have confirmed to NPR and other news organizations that they did, in fact, sign up with the group.

Some defendants that appear in the leaked data have already been described as Oath Keepers by federal prosecutors. For example, Mark Grods signed up for an annual membership with the group in October 2016, according to the data. Grods has since pleaded guilty to charges of conspiracy and obstruction of an official proceeding related to the storming of the Capitol, and has agreed to cooperate with the government.

At least five defendants charged in the Jan. 6 attack, however, have identifying information that appears in the leaked records, but have not been tied to the Oath Keepers as part of their Jan. 6 criminal cases. The news organization ProPublica first reported on three of those defendants. By comparing the Oath Keepers membership data to NPR's ongoing database of all Capitol riot criminal cases, NPR was able to identify another two.

NPR contacted all five defendants as well as their attorneys by phone and email. Only one responded: Kevin Loftus of Chippewa Falls, Wisc.

Loftus entered the Capitol building on Jan. 6 and posted photos of himself inside the building on Facebook with the message, "That is right folks some of us are in it to win it," according to court documents. He pleaded guilty to Parading, Demonstrating, or Picketing in a Capitol Building, a misdemeanor, and is set to be sentenced at the end of January 2022. He has not been accused of committing any violence or property damage. None of the court documents in his case allege a connection to the Oath Keepers.

The Oath Keeper records, meanwhile, indicate that Loftus signed up for an annual membership with the group in November 2016. Loftus confirmed those details. He told NPR by phone that he first heard about the Oath Keepers from podcasts and web shows like Infowars, the conspiratorial media organization led by Alex Jones. Infowars has regularly featured the Oath Keepers on podcasts, videos, and articles going back about a decade.

Loftus said he served in the U.S. Army in the 1990s, and he was attracted to the group's pro-Trump stance and their motto - taken from the military's oath of enlistment - that they "defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic." So Loftus paid for an annual membership with the group, which cost $40 at the time. (The membership fee is now $50 per year.)

Loftus said he ultimately only participated in one event with the Oath Keepers. In October 2019, the group called on volunteers to provide "security escorts for rally attendees" at a Trump event in Minneapolis, Minn. Oath Keepers have frequently been seen at similar events openly carrying rifles, but Loftus said he went to Minneapolis unarmed, and just helped escort rally-goers back to their cars. He said he also briefly met the eyepatch-wearing founder and leader of the Oath Keepers, Stewart Rhodes.

Loftus said he decided to stop paying dues to the group just a few months later. He said he was concerned with how the Oath Keepers spent the money received from members' dues. "I don't know where the money goes," said Loftus. "There was no transparency."

Around that time, Loftus said, he also started turning away from some of the media that introduced him to the Oath Keepers in the first place. "Back in those days, I'd listen to Alex Jones," Loftus said. "I don't listen to that nutbag anymore."

By the time of the Capitol riot, Loftus said he had lost track of the group, and wasn't aware that members of the group were in Washington, DC that day. When he heard the Oath Keepers were under federal investigation for their alleged involvement in the attack, Loftus said he thought to himself, "I'm glad I stopped paying dues." He condemned the rioters who committed violence on Jan. 6, and said he accepted responsibility for his own actions. "I understand I did something wrong," Loftus said, "and I'm going to pay the piper."

It's unclear to what extent any of the remaining four defendants may have been involved in the Oath Keepers. The leaked records that appear to match these defendants state that they all signed up for memberships with the group long before the Capitol riot, and as far back as 2012. Here's what court papers and these records state:

Dawn Frankowski of Naperville, Ill., allegedly breached the Capitol and can be seen on video inside the building. She has pleaded not guilty to all charges. Court records reference the last four digits of Frankowski's phone number. The leaked Oath Keeper records include a membership entry for Dawn Frankowski and a phone number with the same last four digits. The records state that Frankowski signed up for an annual membership with the group in February 2012.

Andrew Alan Hernandez of Riverside, Calif. also allegedly breached the Capitol on Jan. 6. In court papers, federal investigators said that Hernandez appeared to promote a variety of conspiracy theories, including "Q-Anon, health and science related conspiracies, financial conspiracies, and various conspiracies associated to US political figures." He has pleaded not guilty. The Oath Keeper records match Andrew Alan Hernandez's full name, physical address, and include an email address that exactly matches an online account cited in court documents. The records state Hernandez signed up for an annual membership with the Oath Keepers in February 2012.

John Nassif of Chuluota, Fla. allegedly posted on Facebook about breaching the Capitol on Jan. 6, while wearing a red "Make America Great Again" hat. He has pleaded not guilty. The Oath Keepers records state that a John Nassif signed up for an annual membership, but do not specify a date. The phone number included in the leaked records is associated with a social media account that matches an account cited by prosecutors in the case against Nassif. Some of the Oath Keeper data state what activities new Oath Keepers might be able to assist with. Next to Nassif's entry, it states, "Writing articles. Organizing local chapter. Strategy and planning."

Sean David Watson of Alpine, Tex. allegedly sent texts and photos sent shortly after the riot, one of which read "I was one of the people that helped storm the capitol building and smash out the windows . We made history today. Proudest day of my life!" He has pleaded not guilty. Photos allegedly depicting Watson inside the Capitol are included in court records, and show Watson wearing a T-shirt with the logo of the anti-government Three Percenter movement. The Oath Keepers and Three Percenters share much of the same ideology. According to a photo obtained by Marfa Public Radio, the side of Watson's house features the spray painted phrase "DEMOCRATS STOLE THE ELECTION" on the side. A "Veterans for Trump" sign could also be seen hanging outside. NPR was not able to confirm Watson's military history. The Oath Keepers have focused on current and former military servicemembers and law enforcement officers for recruitment. The group's records indicate a Sean David Watson with the same address signed up with the group in December 2012.

There is no publicly available evidence that any of these defendants joined the criminal conspiracies that federal prosecutors have alleged against Oath Keepers in court related to the Capitol riot. And some people included in the Oath Keepers data leak have since told reporters that they just supported the group's political stances or wanted an Oath Keepers T-shirt and had no further involvement.

Whatever the case, the records suggest that the Oath Keepers' extremist ideology may have been more widely adopted than was initially understood.

Rhodes' message in speeches and interviews often focuses on attacking "Marxists" who have supposedly taken over both the Republican and Democratic parties and are "killing our country from the inside"; making baseless claims of widespread "voter fraud"; and calling for individual Americans to arm themselves with "modern infantry weapons" to protect against a wide range of "domestic enemies." Rhodes has been a vocal supporter of Trump since the former president sought the 2016 Republican presidential nomination.

After Trump lost the 2020 election, Rhodes joined the pro-Trump "Stop The Steal" movement that tried to overturn Joe Biden's victory. He also indicated that he was supporting that movement with an armed militia.

Ahead of a Nov. 2020 pro-Trump rally in Washington, D.C. - known as the "Million MAGA March" - Rhodes told Infowars that, "we'll be inside DC, we'll also be on the outside of D.C. armed, prepared to go in, if the President calls us up."

Again, ahead of Jan. 6, 2021, which Trump had promised would be the day of a "wild" protest, Rhodes posted on the Oath Keepers website that the group would "have well armed and equipped QRF [Quick Reaction Force] teams on standby, outside DC, in the event of a worst case scenario, where the President calls us up as part of the militia to to assist him inside DC." That statement has since been cited in indictments of alleged Oath Keepers for allegedly conspiring to attack the Capitol. Prosecutors have alleged that members of the group planned for weeks and months to gather weapons and armor, set up encrypted communication channels, and use military-style tactics to breach the Capitol on Jan. 6.

Rhodes has denied any involvement in the Capitol riot. He was in Washington, D.C., that day, and allegedly met with Oath Keepers who breached the Capitol outside the building, but has not been accused of entering the Capitol himself.

Some commentators on the far-right have suggested that Rhodes may actually be a federal informant himself, because he has not been federally prosecuted. Rhodes has vehemently denied that he has any association with the FBI, and said in an interview in July that the accusation is "a defamation campaign."

He said he also stands by any Oath Keepers who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6.

"I don't think they did anything wrong. I don't think they committed any crimes," said Rhodes. "Do I think it was stupid? Yeah. Because it left our enemies a chance to demonize and persecute them. But I do not disavow them."

People protest the Flint water crisis outside of the Michigan State Capitol on January 19, 2016. (photo: David Guralnick/Detroit News)

People protest the Flint water crisis outside of the Michigan State Capitol on January 19, 2016. (photo: David Guralnick/Detroit News)

Judge announces compensation plans for tens of thousands of residents affected by one of America’s worst public health cases

Announcing the settlement on Tuesday, district judge Judith Levy called it a “remarkable achievement” that “sets forth a comprehensive compensation program and timeline that is consistent for every qualifying participant”.

Most of the money will come from the state of Michigan, which was accused of repeatedly overlooking the risks of using the Flint River without properly treating the water.

“This is a historic and momentous day for the residents of Flint, who will finally begin to see justice served,” said Ted Leopold, one of the lead attorneys in the litigation.

Earlier this year, the judge gave preliminary approval to a partial settlement of lawsuits filed by victims of the water crisis against the state.

Flint’s troubles began in 2014 after the city switched its water supply to the Flint River from Lake Huron to cut costs. Corrosive river water caused lead to leach from pipes, contaminating the drinking water and causing an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease.

The Flint water crisis was one of the country’s worst public health crises in recent memory. The case became emblematic of racial inequality in the United States as it afflicted a city of about 100,000 people, more than half of whom are African-Americans.

The contamination prompted several lawsuits from parents who said their children were showing dangerously high blood levels of lead, which can cause development disorders. Lead can be toxic and children are especially vulnerable.

The former Michigan governor Rick Snyder was charged in January with two counts of willful neglect of duty over the lead-poisoning of Flint’s drinking water.

Payouts from the settlement approved on Wednesday will be made based on a formula that directs more money to younger claimants and to those who can prove greater injury. Michigan’s attorney general has previously said that the settlement would rank as the largest in the state’s history.

“Although this is a significant victory for Flint, we have a ways to go in stopping Americans from being systematically poisoned in their own homes, schools, and places of work,” said Corey Stern, a counsel for the plaintiffs, in a statement after the judge’s order on Wednesday.

The judge said it was “remarkable” that more than half of Flint’s 81,000 residents have signed up for a share of the settlement. It’s not clear just how much each child will receive.

Flint resident Melissa Mays, a 43-year-old social worker, said her three sons have had medical problems and learning challenges due to lead.

“Hopefully it’ll be enough to help kids with tutors and getting the medical care they need to help them recover from this,” Mays said. “A lot of this isn’t covered by insurance. These additional needs, they cost money.”

She considers the settlement a win.

“We’ve made history,” Mays said, “and hopefully it sets a precedent to maybe don’t poison people. It costs more in the long run.”

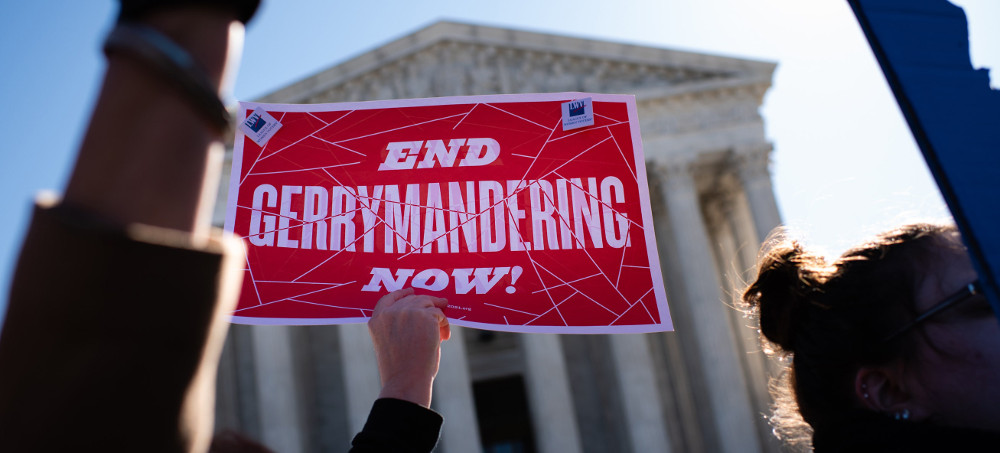

Gerrymandering could keep Democrats out of power in the House for years to come. (photo: Getty)

Gerrymandering could keep Democrats out of power in the House for years to come. (photo: Getty)

Gerrymandering is surging in states where legislatures are in charge of redrawing voting districts used to elect members of Congress

The state remains a perennial battleground, closely split between Democrats and Republicans in elections. In the last presidential race, Republican Donald Trump won by just over 1 percentage point — the narrowest margin since Barack Obama barely won the state in 2008.

But, last week, the GOP-controlled legislature finalized maps that redraw congressional district boundaries, dividing up Democratic voters in cities to dilute their votes. The new plan took the number of GOP-leaning districts from eight to 10 in the state. Republicans even have a shot at winning an eleventh.

North Carolina's plan drew instant criticism for its aggressive approach, but it's hardly alone. Experts and lawmakers tracking the once-a-decade redistricting process see a cycle of supercharged gerrymandering. With fewer legal restraints and amped up political stakes, both Democrats and Republicans are pushing the bounds of the tactic long used to draw districts for maximum partisan advantage, often at the expense of community unity or racial representation.

“In the absence of reforms, the gerrymandering in general has gotten even worse than 2010, than in the last round” of redistricting, said Chris Warshaw, a political scientist at George Washington University who has analyzed decades of redistricting maps in U.S. states.

Republicans dominated redistricting last decade, helping them build a greater political advantage in more states than either party had in the past 50 years.

Just three months into the map-making process, it's too early to know which party will come out on top. Republicans need a net gain of just five seats to take control of the U.S. House and effectively freeze President Joe Biden’s agenda on climate change, the economy and other issues.

But Republicans' potential net gain of three seats in North Carolina could be fully canceled out in Illinois. Democrats who control the legislature have adopted a map with lines that squiggle snake-like across the state to swoop up Democratic voters and relegate Republicans to a few districts.

In the 14 states that have passed new congressional maps so far, the cumulative effect is essentially a wash for Republicans and Democrats, leaving just a few toss-up districts. That could change in the coming weeks, as Republican-controlled legislatures consider proposed maps in Georgia, New Hampshire and Ohio that target Democratic-held seats.

Ohio Republicans have taken an especially ambitious approach, proposing one map that could leave Democrats with just two seats out of 15 in a state that Trump won by 8 percentage points.

Gerrymandering is a practice almost as old as the country, in which politicians draw district lines to “crack” opposing voters among several districts or “pack” them in a single one to limit competition elsewhere. At its extreme, gerrymandering can deprive communities of representatives reflecting their interests and lead to elections that reward candidates who appeal to the far left or right — making compromise difficult in Congress.

While both parties have gerrymandered, these days Republicans have more opportunities. The GOP controls the line-drawing process in states representing 187 House seats compared with 75 for Democrats. The rest of the states use either independent commissions, have split government control or only one congressional seat.

“Across the board you are seeing Republicans gerrymander,” said Kelly Ward Burton, executive director of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, which oversees redistricting for the Democratic Party. Burton didn't concede that Illinois' map was a gerrymander but argued that a single state shouldn't suggest equivalency between the parties.

“They're on a power grab for Congress for the entire decade,” Burton said of the GOP.

Former Attorney General Eric Holder, who leads the Democrats' effort, has called for more states to use redistricting commissions, and a Democratic election bill stalled in the Senate would mandate them nationwide. Democratic-controlled states such as Colorado and Virginia recently adopted commissions, leading some in the party to worry it is giving up its ability to counter Republicans.

Still, Democrats have shown themselves happy to gerrymander when they can. After a power-sharing agreement with Republicans in Oregon stalled, Democrats quickly redrew the state’s congressional map so all but one of its six districts leaned their way. In Illinois, Democrats could net three seats out of a map that has drawn widespread criticism for being a gerrymander.

In Maryland, Democrats are considering a proposal that would make it easier for a Democrat to oust the state’s only Republican congressman, Rep. Andy Harris.

The legal landscape has changed since 2010 to make it harder to challenge gerrymanders. Though using maps to diminish the power of specific racial or ethnic groups remains illegal, the conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that several states no longer have to run maps by the U.S. Department of Justice to confirm they're not unfair to minority populations as required by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. The high court also ruled that partisan gerrymanders couldn't be overturned by federal courts.

“Between the loss of Section 5 and the marked free-for-all on partisan gerrymandering in the federal courts, it's much more challenging,” said Allison Riggs, chief counsel for voting rights at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which is suing North Carolina to block its new maps.

Newly passed congressional maps in Indiana, Arkansas and Alabama all maintain an existing Republican advantage. Of the combined 17 U.S. House seats from those states, just three are held by Democrats, and that seems unlikely to change. In Indiana, the new map concentrates Democrats in an Indianapolis district. In Arkansas, a GOP plan that divides Black Democratic voters in Little Rock unnerved even the Republican governor, who let it become official without his signature. In Alabama, a lawsuit from a Democratic group contends the map “strategically cracks and packs Alabama’s Black communities, diluting Black voting strength."

On Wednesday in Utah, the Republican-controlled state legislature approved maps that convert a swing district largely in suburban Salt Lake City into a safe GOP seat, sending it Gov. Spencer J. Cox for his signature.

Though gerrymanders may not always be checked by the courts, they are limited by demographics.

In Texas, for example, the U.S. Census Bureau found the state grew so much it earned two new House seats. Roughly 95% of the growth came from Black, Latino and Asian residents who tend to vote Democratic. The GOP-controlled Legislature drew a map that, while creating no new districts dominated by these voters, maintained Republican advantages. Civil rights groups have sued to block it.

North Carolina Republicans took a different approach, much as they did a decade ago. Last cycle, courts first found that Republican lawmakers packed too many Black voters into two congressional districts, then ruled that they illegally manipulated the lines on the replacement map for partisan gain.

The new North Carolina map, which adds a 14th district to the state due to its population growth, already faces a lawsuit. Experts say it's unlikely it would have been approved by the Department of Justice if the old rules were in place, especially because it jeopardizes a seat held by a Black congressman, Democratic Rep. G.K. Butterfield.

“It raises a boatload of red flags,” said Michael Li, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice.

North Carolina House Speaker Tim Moore, a Republican, says he's confident the maps “are constitutional in every respect.”

A protester holds a banner during a protest attended by about a dozen people outside the offices of the Israeli cyber firm NSO Group in Herzliya near Tel Aviv, Israel, July 25, 2021. (photo: Reuters)

A protester holds a banner during a protest attended by about a dozen people outside the offices of the Israeli cyber firm NSO Group in Herzliya near Tel Aviv, Israel, July 25, 2021. (photo: Reuters)

Groups Condemn Use of NSO Group’s Pegasus Against Palestinians

We, the undersigned human rights organizations, condemn the hacking of six Palestinian human rights defenders with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware, as uncovered by the Front Line Defenders (FLD) and confirmed by the Citizen Lab and Amnesty International. This attack is part of a broader assault on Palestinian civil society, and it raises serious questions about whether Israeli authorities were involved in the targeting. Three of the targeted human rights defenders come from prominent Palestinian civil society groups that Israeli authorities recently designated as “terrorist organizations.”

The Investigation

In October 2021, Front Line Defenders began collecting data on suspected hacking of the devices belonging to several Palestinians working for civil society organizations based in the West Bank. Their analysis indicated that six of the analyzed devices were hacked using Pegasus. Both the Citizen Lab and Amnesty International’s Security Lab independently confirmed FLD’s analysis.

Pegasus, developed by Israel-based company NSO group, is surreptitiously introduced on people’s mobile phones. It turns an infected device into a portable surveillance tool by gaining access to the phone’s camera, microphone, and text messages, enabling surveillance of the person targeted and their contacts.

NSO Group responded to reports of Pegasus being used to target Palestinian human rights defenders by saying that “[d]ue to contractual and national security considerations, [it] cannot confirm or deny the identity of our government customers.” It also reiterated its past statements that “NSO Group does not operate the products itself; the company license approved government agencies to do so, and we are not privy to the details of individuals monitored,” and that “NSO Group develops critical technologies for the use of law enforcement and intelligence agencies around the world to defend the public from serious crime and terror. These technologies are vital for governments in the face of platforms used by criminals and terrorists to communicate uninterrupted.”

NSO Group did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s request for comment at the time of this publication.

Terrorist Designations of Palestinian Organizations

Three of the six people whose devices were hacked work at the Palestinian civil society groups that the Israeli government designated on October 19 as “terrorist organizations” under its Counter-Terrorism Law of 2016, but they were targeted before Israel’s designation. The people hacked include Ghassan Halaika, a field researcher and human rights defender working for Al-Haq; Ubai Al-Aboudi, the executive director of Bisan Center for Research and Development; Salah Hammouri, a lawyer and field researcher at Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association, based in Jerusalem, in addition to three other human rights defenders who wish to remain anonymous. Two of the people targeted are dual nationals – one French, the other American.

Israel’s decision to designate the organizations as “terrorist” has drawn widespread international condemnation and criticism including from Sweden’s Minister of International Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Affairs, the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Ireland’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Defense, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the EU Special Representative for Human Rights, US Congressional representatives, United Nations experts such as the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Association, and international groups including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, said that the designations were “arbitrary” and “contravene the right to freedom of association of the individuals affected and more broadly have a chilling effect on human rights defenders and civic space.”

A group of 17 UN experts, in a separate statement, concluded that the designations were a “frontal attack on the Palestinian human rights movement, and on human rights everywhere.” As stated, the designations would “effectively ban the work of these human rights defenders, and allow the Israeli military to arrest their staff, shutter their offices, confiscate their assets and prohibit their activities and human rights work.”

Surveillance of Palestinian Human Rights Defenders Violates Their Human Rights

Surveillance of Palestinian human rights defenders violates their right to privacy, undermines their freedom of expression and association, and threatens their personal security and lives. It not only affects those directly targeted, but also has a chilling effect on advocates or journalists who may self-censor out of fear of potential surveillance.

Information obtained through arbitrary surveillance can be used to prosecute, monitor, harass, or detain human rights defenders, dissidents, and others who challenge authorities or dare to stand up to those in power. Both Al-Aboudi and Hammouri have been arbitrarily detained by the Israeli authorities and placed in administrative detention, a practice routinely used by Israeli authorities to imprison Palestinians without trial or charge based on undisclosed secret evidence. On October 18, a day before the designations, the Israeli interior minister revoked Hammouri’s residency status for “breach of allegiance to the State of Israel,” a move to effectively exile him from his home city, despite the international humanitarian law prohibition on an occupying power compelling people under occupation to pledge loyalty or allegiance to it.

The targeted organizations have also been subject to previous harassment by the Israeli authorities, including intimidation, arbitrary detention of staff, travel bans, office raids, and confiscation of equipment. The Israeli government has also applied some of these tactics to Israeli and international human rights advocates.

This targeting of human rights defenders with Pegasus provides further evidence of a pattern of human rights abuses facilitated by NSO Group through spyware sales to governments that use the technology to persecute civil society and social movements in many countries around the world. Furthermore, these abuses underscore how NSO Group’s Human Rights Policy fails to prevent and mitigate human rights abuse in a meaningful way.

Call for Action

From the first revelations by the Citizen Lab in 2016 of NSO’s technology being used against the UAE dissident Ahmed Mansoor, to the recent Pegasus Project revelations by Amnesty International and Forbidden Stories, civil society has been calling for accountability for NSO Group and governments that use its technology and services.

Today, we, the undersigned organizations:

- Reiterate our calls on states to implement an immediate moratorium on the sale, transfer, and use of surveillance technology until adequate human rights safeguards are in place, and

- Press UN experts to take urgent action to denounce human rights violations by states facilitated by the use of the NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware and to provide immediate, robust support for impartial and transparent inquiries into the abuses.

The November 3 decision by the US Department of Commerce to add NSO Group to its trade restriction list (Entity List), for “acting contrary to the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States” is a positive step. The Commerce Department cited the use of NSO Group tools by foreign government clients to “maliciously target government officials, journalists, businesspeople, activists, academics, and embassy workers” and to enable “foreign governments to conduct transnational repression” by “targeting dissidents, journalists and activists outside of their sovereign borders to silence dissent.”

NSO Group said it was “dismayed by the decision” and will press to reverse it.

We encourage other states to impose similar restrictions to prohibit the export, sale, and in-country transfer of NSO Group technologies, as well as the provision of services that support NSO Group's products.

Signatory Organizations

- Access Now

- Human Rights Watch

- Masaar - Technology and Law Community

- Red Line for Gulf

- 7amleh- The Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media

- SMEX

- INSM Network for Digital Rights- Iraq

Randy Constant perpetrated the largest known organic food fraud in US history. (photo: AP)

Randy Constant perpetrated the largest known organic food fraud in US history. (photo: AP)

There’s no way to confirm that a crop was grown organically. Randy Constant exploited our trust in the labels—and made a fortune.

Constant, then in his thirties, had a degree in agricultural economics from the University of Missouri. Since graduating, he had “worked his way up the agricultural corporate ladder,” as his wife, Pam, later put it. In the eighties, a time of collapse in America’s farming economy, he had taken a series of sales and managerial jobs across the Midwest, before returning with Pam and their three children to live in Chillicothe, Missouri—a town of about nine thousand residents, ninety miles northeast of Kansas City, where he and Pam had grown up. Constant became active in Chillicothe’s United Methodist church, and later served as president of the town’s school board.

Constant appeared to be “the epitome of the Midwestern guy,” Ty Dick, a former employee, said recently. “Straightforward, healthy, wholesome.” Constant wore button-down shirts; his hair was always neatly combed. Hector Sanchez, who once worked for Constant in Chillicothe, recalls his former boss’s solicitousness: “He always asked me, ‘Do you need anything? Are you good ?’ ” When Constant met Borgerding, he had recently become licensed to sell real estate, and he occasionally sold a farm on behalf of Rick Barnes, of Barnes Realty, in Mound City, Missouri. Barnes, who told me he used to think that Constant missed his calling by not selling real estate full time, said, “He came across like a deacon in the church. He probably was a deacon.”

After the soybean-farm collaboration ended, Borgerding and Constant discussed starting a business together. “I had a lot of trust in him,” Borgerding said. “I felt that he had a lot of integrity. I felt that we had a very unified vision of what we wanted to accomplish.” In 2001, they founded a company, Organic Land Management.

John Heinecke lives and farms near Paris, Missouri, a hundred miles east of Chillicothe. When I called him to ask about Constant, he said, “That cocksucker. He screwed me over to fucking death.” Heinecke was about to drive to his weekend house, on an inlet at the Lake of the Ozarks, and he agreed to meet me there a few days later.

We spoke on his screened-in porch, which had a view down to his dock and his motorboat. Heinecke, who is in his early sixties, was wearing a sleeveless T-shirt and a fentanyl patch; he talked of spinal injuries related to a lifetime of agricultural lifting. Now and then, we had to shout over the straight-pipe speedboats screaming down the lake’s main channel.

Heinecke first went bust in the mid-eighties, when he was farming rented land. “Bank called my notes,” he said. By the time he met Constant, in the mid-nineties, he was enjoying a period of success as a contract farmer, working fifteen hundred acres for various owners. “I probably had forty farms or so,” he said. “A lot of little farms. I was a patch king!”

Heinecke used to have a sign at the end of his driveway which read “i shoot every third salesman.” Constant, pitching for Pfister, came to the door. Heinecke remembered him as “a smooth talker, one of these guys you have to worry about.” Constant enlisted Heinecke to become a local seed salesman for Pfister. That was their business relationship for the next few years. Then, around 2000, Constant asked if Heinecke knew of any pastureland that wasn’t being used. Heinecke mentioned a nine-hundred-acre farm, owned by a relative, a section of which hadn’t been tilled in years. “Can you rent that?” Constant asked. He then explained that he wanted to farm it organically.

Heinecke recalls replying, “Tell me what this organic deal is.”

More than in most retail transactions, the organic consumer is buying both a thing and an assurance about a thing. Organic crops are those which, among other restrictions, have been grown without the application of certain herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers. Close scrutiny of a crop of non-organic tomatoes might reveal that they had been exposed to these treatments. But it might not. And an organic product can become accidentally tainted if proscribed chemicals carry across from a neighboring crop. The rules forgive such contamination—to a point. Testing for residues is not common in American organic regulation.

The real difference, then, between a ton of organic soybeans and a ton of conventional soybeans is the story you can tell about them. The test, at the point of sale, is merely a question: Was this grown organically? That’s not like asking if a cup of coffee is decaffeinated. It’s more like buying sports memorabilia—is this really the ball?—or like trying to establish if a used car has had more than a single, careful owner.

The organic story has legitimate power. A farm’s conversion to organic methods is likely to increase biodiversity, reduce energy consumption, and improve the health of farmworkers and livestock. And, to the extent that agricultural chemicals enter the food supply, an organic diet may well be healthier than a conventional one.

When Constant asked Heinecke about pastureland, American organic agriculture had just begun booming. In 2000, organic sales in ordinary supermarkets exceeded, for the first time, sales in patchouli-scented health-food stores. During the next five years, domestic sales of organic food nearly doubled, to $13.8 billion annually. The figure is now around sixty billion dollars, and the industry is defined as much by large industrial dairy farms, and by frozen organic lasagna, as it is by the environmentalism and the irregularly shaped vegetables of the organic movement’s pioneers.

A new national system of organic certification, fully implemented in 2002, helped spur this growth. Previous regulation, where it had existed, had been uneven: farmers in Iowa could become organic by signing an affidavit saying that they farmed organically. Given the inscrutability of a crop’s organic status, the new system was likely to preserve an element of oath-making, but the reliance on trust was now overlaid—and, perhaps, disguised—by paperwork. Organic farmers, and others in the organic-food supply chain, were now required to hire the services of an independent certifying organization—one that had been accredited by an office of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Organic Program. A certifier kept an eye on a farm’s operation, primarily through an annual scheduled inspection.

Among the new federal rules: land subjected to non-organic treatments couldn’t be converted to organic production overnight. The process would take three years. Given how fast the organic market was expanding—including for meat, eggs, and dairy products, derived from animals given only organic feed—land that needed no transition period became valuable.

Organic Land Management proposed to find such land and, in exchange for a share of a farmer’s profits, get it certified, and then help grow and market the crops. “At the time, conventional corn was, let’s say, two dollars a bushel,” Borgerding told me. “The first corn crops that we sold were three-seventy-five and four dollars a bushel.”

Constant and Borgerding never worked out of the same office. Borgerding made deals with farmers in Minnesota and the Dakotas; Constant kept farther south. Their company’s pitch was bound to appeal to farmers who had bad credit, or other problems. John Heinecke, the patch king who’d struggled with bankruptcy, agreed to join. In Overton, Nebraska, Constant also signed up James Brennan and his father, Tom—a decorated Vietnam veteran whose alcohol abuse, connected to P.T.S.D., would lead to several convictions for drunk driving.

Within a few years, Organic Land Management was handling six thousand acres, on a dozen farms in five states. In the eyes of American regulators, this was a single operation, requiring only a single organic certification—as if the company’s scattered fields were divided only by railroads or rivers, rather than by, say, Iowa.

Constant and Borgerding settled on Quality Assurance International, based in San Diego, as their certifier. This was not the cheapest option. Q.A.I.’s core business was certifying food-processing companies, not farms; its name is now on every other box of American organic cookies and cornflakes. I recently spoke with Chris Barnier, who, between 2004 and 2007, oversaw Organic Land Management’s finances and records. Though he did not directly criticize Q.A.I., he said, “It’s a huge flaw in the organic industry that the farmers pay the certifier—sometimes many thousands of dollars. The certifier has a conflict of interest, because they really don’t want to blow the whistle on a fraud.”

Moreover, any inspection, however principled the investigator, is likely to be cursory. After Barnier left Organic Land Management, he worked for a while as an inspector himself. He explained that extending a farm visit beyond a couple of hours—looking at paperwork, asking questions—can feel like a provocation. The cows need milking, the kids are whining. An established grain trader recently told me that the certification industry is essentially toothless, adding, “If you saw my operation, then came and saw what they do on an inspection, your mind would be blown. I do thousands of transactions a year. They look at three.”

Borgerding told me, “Chris and I worked real hard to maintain the integrity of things—to make sure all of our organic paperwork was in order.” Nevertheless, he acknowledged that he had been drawn to Q.A.I. partly because the company was perceived not to nitpick: “It was not my intention to abuse their potential leniency. But I think they kind of glossed over things.” And, because Q.A.I. inspectors were not farm specialists, “they—at least at that time—were a little bit unaware. It was just more of a foreign territory to them.” He added, “They’re way out in California! What did they know about Midwest agriculture?” (A representative for Q.A.I. said that its inspectors understand the “intricacies of their particular region’s agricultural industry.”)

Constant and Borgerding were able to pay themselves a hundred thousand dollars a year. The Constants, who had a son and two daughters, the youngest of whom was in her teens, moved into a spacious house on Oaklawn Drive, in Chillicothe’s more monied end. Their furnishings included ceramic rabbits, two crosses, and a framed map of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, where the family liked to vacation.

Looking back, Borgerding can see that he failed to notice warning signs about his partner. He said that, in Missouri, he “would mention Randy’s name and people would just close down, back off.” He knew that Constant always had a side project. “When I hooked up with him, I was the side project,” he said, referring to Constant’s job at Pfister. “But it always haunted me a little: What happens when our business becomes the main project? What would Randy do on the side?”

He recalled once watching in awe as Constant deflected an agricultural inspector’s query about record-keeping. In a flurry of paper, “Randy threw down this document, tied to this document, and tied to this document, and presented it as ‘It’s so obvious, any idiot can figure this out—why can’t you?’ ” The inspector retreated. Today, Borgerding has a sense that he witnessed a charade. But, he said, “the tone in Randy’s voice, and the way he acted, it was like Novocaine—it just put you at ease.”

In 2001, Constant, on behalf of Organic Land Management, signed a contract to deliver organic soybeans from farmers it worked with to a facility in Beardstown, Illinois, owned by the Clarkson Grain Company. Clarkson, which buys grain from farmers and sells largely to food manufacturers, was an early specialist in organic grain and in grain that is not a genetically modified organism, or a G.M.O. The grain industry was then being transformed by such new products as Monsanto’s Roundup Ready soybeans and corn, which are genetically modified to survive in fields sprayed with Roundup, a weed killer made by the company.

A non-G.M.O. crop might or might not be organic, but a genetically modified crop is definitely not organic. Today, it’s nearly inevitable that a commercial buyer of organic grain will subject the crop to a G.M.O. test, which can take only a few minutes. But in 2001 it was unusual for such buyers to test every delivery. Clarkson did.

A Clarkson employee who worked at Beardstown at the time recently recalled that Organic Land Management’s soybeans, arriving by truck, tested positive for G.M.O.s. The drivers said that they must have accidentally loaded grain from the wrong storage bins at the farms. The next day, “the trucks came back,” the Clarkson employee told me. “More loads with the same results.” These, too, were sent away. Constant called up, furious, claiming that there was a mistake on Clarkson’s end. The trucks kept coming in for about a week, then stopped. “We eventually tore up the contract with Randy,” the Clarkson employee said. “We guessed at the time that he had found another buyer who was not testing for G.M.O.s.” In a recent call, Lynn Clarkson, the founder and C.E.O. of Clarkson, compared Constant to an Internet scammer. “He’s testing, just like the ransomware guys,” he said. “They want to test your defenses and see if they’re working.”

Around the time that Clarkson rejected the soybean trucks, Duane Bushman, who runs a grain-trading business in Fort Atkinson, Iowa, bought his first load of certified organic corn from Organic Land Management. Bushman felt confident about the transaction: he had visited two Organic Land Management farms. Over the next several years, he bought corn from the company in increasing quantities. Then something odd happened. During a phone conversation in the first half of 2006, Constant mentioned that he was out of corn from the previous harvest. But in a second call, a week or so later, Constant suddenly had a supply. He told Bushman, “I found five more railcars!” A railcar holds about a hundred tons of corn. Five railcars might be the annual yield of a modestly sized Missouri farm. Constant’s corn was covered by his company’s organic certification, but Bushman felt uneasy, and asked to see transaction certificates, which can indicate a load’s date and place of origin. Bushman, who was about to go on a work trip, told his assistant, Linda Holthaus, who had worked for him for several years, “Don’t pay him for those five loads until you get the T.C.s.”

When Bushman returned from his trip, Holthaus had paid for the order. She had also taken a new job, at Jericho Solutions—a grain brokerage that Randy Constant and his friend John Burton, a Missouri farmer, had just set up. In September, 2006, Constant created a branch of Jericho Solutions whose registered address was Holthaus’s home, in Ossian, Iowa.

Bushman tried and failed to reach Constant. Eventually, he Googled “Organic Land Management, Inc.,” found Glen Borgerding’s name, and called him. Borgerding was sympathetic, noting that it was often hard to get Constant to return calls, and asked if he could help.

“Well, there’s this paperwork on the railcars that you guys sold,” Bushman said.

Borgerding was confused: “Excuse me?”

“Remember those railcars?” Bushman said.

Borgerding told Bushman that Organic Land Management had never sold grain to Bushman’s company.

There was a pause. Bushman then asked, with evident anxiety, how much corn Organic Land Management had been growing in Missouri in recent years. About fifteen hundred acres, Borgerding said. Both men were again silent. Borgerding recalls, “You could have heard a pin drop.”

The math didn’t work: Bushman had been buying far more corn from Constant than could possibly have been grown on Organic Land Management’s Missouri farms. It began to dawn on Borgerding that “we were not talking about a load or two—we’re talking millions of dollars of grain.” He recalls concluding that Constant might have just been acting as a broker on the side—buying grain from other organic farmers and then selling it on. Borgerding laughed, weakly, then said, “Or he was doing something else.”

Constant was, in fact, passing off non-organic grain as organic grain. The scheme, in which at least half a dozen associates were involved, is the largest-known fraud in the history of American organic agriculture: prosecutors accused him of causing customers to spend at least a quarter of a billion dollars on products falsely labelled with organic seals.

Clarence Mock, a Nebraska lawyer who represented Mike Potter—one of the farmers who worked with Constant—recently proposed that the scheme may have been sustained, in part, by a disdain for organic consumers. “There was a little bit of a sense of effete, latte-drinking, Volvo-driving people,” Mock said. “The whole idea of organic corn versus other kinds of corn, you know—once you grind it up and put it into cornmeal, who the hell knows the difference?” The scheme’s participants, Mock went on, had perhaps recognized that misrepresenting grain as organic was “kind of naughty,” while telling themselves, “Nobody’s getting hurt, or getting sick. It wouldn’t be, like, ‘We’re drug manufacturers, and we’re giving people bad drugs.’ ”

Several organic old-timers I spoke with said that farmers often turn to organic production purely for the price advantage. At that stage, they may find the organic idea absurd, or at least discomforting: more work, more weeds, probably a lower yield. Some give up. For others, the experience of farming organically—of ending a reliance on chemicals and their providers, and perhaps seeing healthier animals, among other satisfactions—creates a convert.

This wasn’t Constant’s path. He seems to have begun with one idea for easy money—four dollars a bushel, and someone else doing the labor—and then discovered that within reach was a way to get money that was so much easier.

A farm’s organic certification is good for a year. It doesn’t get used up by sales. If a farmer has only a dozen organic apple trees, but agrees to sell you a million organic apples, you’re unlikely to learn that you have a problem merely by looking at the orchard’s certification. As the established grain trader explained, “Some certifiers put the acreage on the certification. Some don’t. It isn’t a U.S.D.A. requirement. It’s nuts!”

On at least one occasion, a farmer working with Constant treated a field with herbicides and pesticides—but left the perimeter untouched. To a neighbor, or a hurried inspector, the field would look as scrappy and weed-infested as it should. (Rick Barnes, the real-estate agent who employed Constant, told me that every organic farm “looks like a disaster.”) But Constant’s illicit activities rarely required much guile. In a market that often seems to value a certificate of authenticity over authenticity, all he had to do was lie.

Constant came to learn that, as long as he maintained control of some fields certified as organic, almost nothing stood in the way of his selling non-organic grain obtained elsewhere, as if it all had grown in those fields. In 2016, his sales of organic corn implied a yield per acre of about thirteen hundred bushels—about ten times any plausible number. That year, Constant controlled some three thousand acres certified for either organic corn or soybeans, and brought in about twenty million dollars. If, as Mock suggests, the organic consumer could be seen as a chump, Constant’s greater disregard may have been for the organic regulators and traders who agreed to take him at his word. As the Clarkson employee said of Constant, “In his mind, he could slick-talk anyone, and had no fear of actually getting caught.”

It isn’t hard to see how Constant had developed this confidence. When he was young, the Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune had frequently run admiring stories about him. He was a “hard nosed” defensive end on his high-school football team; he called in a report of vandalism to the police; he won scholarships and raised funds for charity. And he was clearly on a path to agricultural success: in 1974, at the age of fifteen, Constant became the “barnwarming king” in the local chapter of the Future Farmers of America. He went on to become the group’s chapter president, and to represent his district at a national conference. He won an F.F.A. award for his agricultural record-keeping, and another for his recitation of the organization’s creed, which includes these lines: “I believe that American agriculture can and will hold true to the best traditions of our national life and that I can exert an influence in my home and community which will stand solid for my part in that inspiring task.”

In negotiations with business partners, Constant liked to say, “Look, I’m just a dumb farmer.” John Heinecke said of him, “Hell, he didn’t know shit about farming.” This is perhaps unfair. Though it may have been odd to think of Constant driving a tractor, he could certainly join a conversation about tractors. “Randy could speak the language of agriculture,” Lynn Clarkson told me. Constant’s sales pitch sometimes included a savvy appeal to nostalgia: organic farming, he would say, was just like “how we did it in the sixties.”

Constant leased a few dozen acres of farmland near Chillicothe, and at times he managed thousands of acres elsewhere. But when he called himself a farmer—say, when he ran for the Chillicothe school board—he was simplifying a career of unrelenting hustle. Constant sold seeds, soybeans, fish, and real estate; he considered growing cilantro, for Chipotle restaurants, and growing marijuana; he explored an investment in “lingerie football,” played by women, with their midriffs exposed.

A former employee of Constant’s, who was keen to remember his better qualities, nonetheless described him to me as “friendly and presentable, but calculating.” Other associates shared similar impressions. In the early two-thousands, a young soybean farmer, Ben Austic, spent a week with Constant in London, on a junket that the Missouri Department of Agriculture had organized for people connected to organic farming. Austic, who has since become a Baptist minister, noticed that whenever the group’s conversation turned away from organic farming—say, during the intermission of “Les Misérables”—Constant cranked things back to sales opportunities. “I don’t mean this in an evil way, but he was always scheming,” Austic said. “If you’ll forgive the term, he was a bullshitter.”

In 2006, Constant started selling his grain through Jericho Solutions, the brokerage that he set up with his friend John Burton. Instead of negotiating with a trader like Bushman, Constant was now his own trader. He could present Linda Holthaus, Bushman’s former assistant, with grain and certifications for grain. And Holthaus, from her time with Bushman, knew where to find customers. In Jericho, Constant now had a reliable, in-house buffer between his grain’s source and its eventual customer. (Holthaus, who has not been accused of any wrongdoing, did not reply to requests for comment.)

In June and August, 2007, two stories published by The Organic … Non-GMO Report, a trade magazine, gave the first public hints of Constant’s deceptions. The articles centered on a Nevada company that processed soybeans. It had bought some supposedly organic soybeans from Jericho Solutions, but they had tested positive for G.M.O.s. The contamination was said to have cost the company a hundred thousand dollars. The magazine quoted Holthaus, who sounded defiant: “There was no problem on our end. We had the paper trail. . . . Someone’s trying to nail us for something we didn’t do.” Apparently without evidence, she blamed Chinese soybeans that had passed through the Nevada facility. The soy processor said, in response, that it had never had a G.M.O. problem with Chinese soybeans.

I asked John Heinecke about this episode. By 2007, he no longer had an Organic Land Management contract, but he remained open to working with Constant. The Nevada facility had been tainted, Heinecke said, by “railcar loads of fucking Roundup Ready beans.” He began to yell. “And Randy knew they were, because he knew what he bought! I sold them to him! I sold him the goddam railcars!” Heinecke said that he’d bought the soybeans from a Missouri landowner for whom he farmed. “I said, ‘Randy, these are Roundup Ready beans.’ He said, ‘I don’t care. Put ’em on a car. I’ll take care of it.’ ”

Constant and Borgerding, his partner at Organic Land Management, decided to sever ties in April, 2007. They agreed that Constant could keep the company’s name. Borgerding told me that the split was friendly, and the result of a cash-flow crisis. But he also said that in 2006 Constant had wildly underreported soybean yields on his portion of Organic Land Management farmland. (“It got dry toward the end of the summer,” Constant had claimed.)

There’s no evidence that Borgerding was involved in wrongdoing, and his reputation in the organic world remains strong. But, like many other former Constant associates, he can’t exactly say that he was floored when, in 2017, federal agents turned up at Oaklawn Drive, in a convoy of vehicles. He had picked up some worrisome clues about Constant’s undeclared side projects. The odometer on Constant’s truck had suggested incessant travel: it clocked hundreds of miles a day. And Constant had increasingly pushed for puzzlingly high-risk investments, like buying land in Colorado. “What the heck do we want to do in Colorado?” Borgerding had asked himself. “It never rains there.”

As Borgerding sees it, he became “dead weight” when he resisted such efforts to rapidly expand the company. So Constant found another way: “With Linda coming on, with all her contacts, suddenly he had a big market. And that became his main gig.”

After Borgerding left Organic Land Management, he stopped speaking with Constant. “It’s like you’re in one of the lifeboats on the Titanic,” he said. “You’re paddling away from the thing as fast as you can before it goes down and sucks you down along with it.”

In 2010, Constant called Heinecke for the first time in a while.

“John, I need some corn.”

“Not a problem. We’ve got half a million bushels.”

“Well, let’s load it there at Goss—the rail siding.”

Goss, a mile or so from Heinecke’s home, is a quiet place to do business: in the last census, the town had a population of zero. The siding hadn’t been used for years. Heinecke usually delivered grain to Stoutsville, six miles from his home, or at the Mississippi River, forty miles away. “To this day, I have not figured out how Randy got that siding open,” Heinecke told me. Constant’s success derived partly from his mastery of the railroad freight system, apparently learned during his years of corporate agricultural work.

Heinecke agreed to supply Constant, who, he said, offered “more than the local price, and more than I could get at the river”—a dollar a bushel more than another buyer would have paid, a premium of at least twenty per cent at the time. A bushel of corn weighs fifty-six pounds. Trucks can carry between five hundred and a thousand bushels. A railcar typically carries thirty-five hundred bushels, or about a hundred tons. When Heinecke began making grain deliveries at Goss, Constant usually gave him forty-eight hours to complete the task. In that time, Heinecke would normally fill seven railcars. He told me that, within a year, he had filled about a hundred.

This corn came either from land that Heinecke farmed, as a leaseholder, or from land farmed by neighbors. None of it was organic. Heinecke told me that he never claimed that it was. “It was non-G.M.O., but I was using modern fertilizer, right?” he said. “Phosphorus and nitrogen—the stuff we do for everything. I was using herbicides.” He went on, “I sold everything to Randy Constant. I didn’t sell to nobody else.”

Heinecke isn’t an easy man to like: he is susceptible to covid-19 conspiracy theories, and on the day we met he announced his racism with a flat statement of prejudice. He is estranged from both his father and his oldest child. Although he fulminated to me about Constant’s slipperiness, he also made a case for not pressing buyers too hard about their intentions. He recalled once asking a buyer who had purchased some moldy corn from him about his plans for it. “Do you like doing business with me?” the buyer said. “I don’t ever want to hear you ask that question again.”

Heinecke told me he’d always assumed that Constant was selling to buyers of non-organic grain. Theoretically, yes. Constant might have had such customers—he had a lot going on—but his land-management company had “organic” in its name, and his brokerage described itself as devoted to “Organic Planning, Production … Marketing.” There’s no sign that Constant, in the years that he bought from Heinecke, ever sold grain that wasn’t described as organic. During this time, corn labelled organic was often worth twice as much as conventional corn. As a railcar began inching out of Goss, its twenty-five-thousand-dollar load became a fifty-thousand-dollar load.

In 2010, Constant was paid $16.5 million for organic grain. By 2015, the figure was $24.4 million.

Jericho Solutions once claimed to be the country’s fourth-largest organic-feed operator. Clients’ payments would be deposited in the Luana Savings Bank, in Luana, Iowa, a town of some three hundred people about twenty miles from Linda Holthaus’s home. The bank stands on the town’s edge, surrounded by fields.

On February 10, 2017, for example, a customer banking in Sonora, California, transferred $419,417.50 to Jericho’s account in Luana. Duane Bushman told me that Constant regularly sold grain to a Sonora-based company called Oakdale Trading. (The established grain trader knew of this relationship, too.) Bushman knows Oakdale’s owner, Jim Parola, and he remembered a time when Parola “started to brag” that, for a period of some weeks, he had been able to send ten railcars of Constant’s corn a week to the East Coast, and ten loads to the West Coast. Bushman recalled once asking Parola about his confidence in Constant’s grain: “He said that as long as he had a certification that’s all he had to care about.” (Parola didn’t respond to requests for comment.)