Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

With the rise of the modern right, however, America turned its back on that history. Tax breaks — essentially giving wealthy people money and hoping that it would trickle down — became the solution to every problem. “Infrastructure week” became a punchline under Donald Trump partly because the Trump team’s proposals were more about crony capitalism than about investment, partly because Mr. Trump never showed the will to override conservatives who opposed any significant new spending.

Now Joe Biden is trying to revive the tradition of public spending oriented toward the future.

The Build Back Better legislation that passed the House recently isn’t a pure investment plan; in particular, it includes substantial health care spending that is more about helping Americans in the near term than about the future. But about two-thirds of the proposed spending is indeed investment in the sense that it should have big payoffs in the future. And if you combine Build Back Better with the already enacted infrastructure bill, you see an agenda that is about three-fourths investment spending.

Here’s how I read the Biden program as it now stands. Total new spending would be about $2.3 trillion over a decade. This total would include $500 billion to $600 billion of spending on each of three things: traditional infrastructure, restructuring the economy to address climate change, and children, with the last item mainly consisting of pre-K and child care but also involving tax credits that would greatly reduce child poverty.

There’s every reason to believe that all three types of spending would have a high social rate of return.

Snarled supply chains have reminded everyone that old-fashioned physical infrastructure remains hugely important; we are still living in a material world, and getting stuff where it needs to go requires public as well as private investment.

As far as climate investments are concerned, the damage from a warming planet is becoming increasingly obvious — and droughts, fires and extreme weather are only the leading edge of the disasters to come. Build Back Better’s investments wouldn’t come close to ending the danger, but they would mitigate climate change, partly protect us against some of its consequences and make it easier for the United States to lead the world toward a more comprehensive solution. So the money would be well spent.

Finally, there is overwhelming evidence that helping families with children is a high-return investment in the nation’s future because children whose families have adequate resources become healthier, more productive adults.

So what’s not to like about this agenda? No, it wouldn’t be inflationary: Don’t take it from me, but listen to credit rating agencies, which are saying the same thing. The approved and proposed spending would be fairly small as a share of gross domestic product — which the Congressional Budget Office projects at $288 trillion over the next decade — and largely paid for with new taxes, so it would have very little inflationary impact.

Oh, and while some of the “pay-fors” are questionable — as it happens, mainly on the traditional infrastructure bill; Build Back Better is more or less paid for — which means that the spending would probably add somewhat to federal debt over the next few years, that debt increase would be small relative to GDP and, given low interest rates, would barely add to debt service costs. Over the longer term, the payoff to public investment might well be enough to reduce the deficit.

Still, Republicans are denouncing the Biden agenda as socialism because, of course, they are. Hey, by their standards America has been run by socialists for most of its history — people like DeWitt Clinton, the New York governor who built the Erie Canal, and Horace Mann, who led the Common School movement for universal basic education a couple of decades later. And don’t even get me started on Dwight Eisenhower, who presided over huge government investment and a top tax rate of 91%.

Admittedly, the Biden plan would reduce economic disparities, both because expanded benefits would matter more to less-affluent families and because its tax changes would be strongly progressive. But public policy that reduces inequality, like public investment, is squarely in our national tradition. America basically invented progressive taxation, and as economist Claudia Goldin has noted, the high school movement was “rooted in egalitarianism.”

So don’t believe politicians who are trying to portray President Biden’s investment agenda as somehow irresponsible and radical. It’s highly responsible, and it’s an attempt to restore the all-American idea that government should help create a better future.

Nancy Pelosi. (photo: Reuters)

Nancy Pelosi. (photo: Reuters)

Hanging in the balance is the Build Back Better Act, an ambitious attempt to create jobs, strengthen the US social safety net, and address climate change that Democrats are still struggling to finalize. The package has been repeatedly cut back to appease conservative Democrats, but even its reduced form would make it the most significant anti-poverty program in half a century.

Still, some in the party are trying to pump the breaks. "Nobody elected Joe Biden to be FDR," said Virginia Rep. Alison Spanberger. "He was elected to be normal and stop the chaos."

Spanberger is mistaken. Polls show broad support for the plan's provisions — including more affordable health care, prescription drugs, child care, and elder care, as well as monthly payments for parents, investments in clean energy, and more.

The bill has now been passed by the House. As it heads to the Senate, the Democrats need to focus on passing the bill, not stripping it down.

Pays for itself

All of this is more than paid for by fairer taxation of the uber-wealthy, which is itself very popular.

An overwhelming majority of Americans support these measures, including a majority of independents and nearly 40% of Republicans polled. So this is not only Biden's agenda — it's the new normal that the majority of US voters desperately want.

Yet Youngkin won where he shouldn't have, New Jersey's Democratic governor was only narrowly reelected, and only Donald Trump was more unpopular at this point in his presidency than Joe Biden is.

A big part of the problem is that most voters simply have no idea that Democrats are trying to do all this. Instead of telling voters what's actually on the agenda in Washington, the mainstream media has been nearly exclusively focused on the "cost" — and the infighting between progressive and "moderate" Democrats. Neither focus is accurate or honest.

The same surveys that show overwhelming support for elements of the Build Back Better Act also show that barely a third of voters believe anything in it will help them. People don't know what's in the bill — a big enough problem that Sen. Bernie Sanders held a webinar entitled "What's in the Damn Bill?"

Far more voters, by contrast, have heard something about what the bill costs. 60% say they know the bill's cost — $3.5 trillion over 10 years in its original form, now closer to $1.85 trillion.

Set aside for a moment that these investments represent a fraction of what we spend on the Pentagon, and barely a drop of water in the sea of money poured into militarism since 9/11. The real net cost of the law is closer to $0.

Because the bill raises revenue from taxing millionaires, billionaires, and profitable corporations, the plan is more than paid for. In fact, over the next 10 years it raises enough revenues to actually start paying down the federal debt.

What's more, 15 Nobel Laureate economists agree that the plan won't contribute to inflation. In fact, by creating good jobs and making it easier for Americans to afford child care, food, housing, prescription drugs, and certain medical expenses, the bill offers much-needed assistance to voters worried about inflation.

Once you know what's actually in the bill, the coverage of the debate over it feels even more frustrating.

For one thing, there's nothing "moderate" about the obstructionism of Democratic Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. By limiting the bill's ability to allow Medicare to negotiate lower prescription drug prices, raise tax rates on billionaires, and guarantee American workers paid family and medical leave, they've positioned themselves far outside the US mainstream. This opposition to broadly popular ideas is radical, not moderate.

But for another, negotiation is what democracy is all about. Lawmakers should be doing as they're doing: listening to constituents and advocates, incorporating data, and representing voters. The sensationalist, 24/7 cable news infotainment industry has morphed the perception of this process into dysfunction rather than democracy.

If Joe Biden was elected to "be normal" and "stop the chaos," then this program would take the first step toward a new normal — and away from the chaos of poverty, uncertainty, and climate disruption so many of us are experiencing.

Democrats shouldn't back away from the wildly popular programs in the Build Back Better bill. Instead, they need to pass it, and make sure voters actually know about it.

Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp. (photo: CNN)

Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp. (photo: CNN)

We speak with Mansoor Adayfi, a former Guantánamo Bay detainee who was held at the military prison for 14 years without charge, an ordeal he details in his new memoir, “Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo.” Adayfi was 18 when he left his home in Yemen to do research in Afghanistan, where he was kidnapped by Afghan warlords, then sold to the CIA after the 9/11 attacks. Adayfi describes being brutally tortured in Afghanistan before he was transported to Guantánamo in 2002, where he became known as Detainee #441 and survived years of abuse. Adayfi was released against his will to Serbia in 2016 and now works as the Guantánamo Project coordinator at CAGE, an organization that advocates on behalf of victims of the war on terror. “The purpose of Guantánamo wasn’t about making Americans safe,” says Adayfi, who describes the facility as a “black hole” with no legal protections. “The system was designed to strip us of who we are. Even our names were taken.”

Mansoor Adayfi has just published his memoir. It’s called Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. I spoke to him in September from his home in Belgrade. I began by asking him to talk about how he ended up at Guantánamo.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: OK, let’s fly back like 38 years, which, actually, I — like, when people ask me, “How old are you?” I say I’m like 24, because I don’t count Guantánamo, like try to cheat. Anyway, I born in a tiny village in Yemen, Raymah, born like with 11, 12 — 11 brothers and sisters, large family, very conservative family. I studied my primary school and secondary school in the village. We had no high school, so I had to go live with my aunt in the capital, Sana’a, which was like a new world.

When I finished with my high school, I was assigned to do some research in Afghanistan. I was like a research assistant in Afghanistan. This is how my journey started there. In Afghanistan, I spent a couple months researching and doing some of the research required to be done.

One day, after 9/11, I was kidnapped by the warlords. They were actually interested in the car; they weren’t interested in us. Then, when Americans came, the American airplane, they were throwing a lot of flyers offering a large bounty of money, which could change Afghanis’ life. So, Afghanis found out that the more you give them high-rank people, the more you get paid. The price ranged between $5,000 to like $200,000, $500,000.

First of all, we were taken as — held for ransom. Then I was sold to the CIA as an al-Qaeda general, middle-age Egyptian, you know, a 9/11 insider. I was taken to the black site, where I was, like, tortured for like over two months, then from the black site to Kandahar detention — was one of the funny things.

When I arrived at Kandahar detention, I was totally naked there. It’s like another — it’s a long journey. Second day of my arrival, guards came to move me to a tent. After the interrogation, I was asked to sign a paper that the Americans have a right to shoot me and kill me if I try to escape. I said, “No, I’m not going to sign. Of course I will try to escape. I shouldn’t be here in the first place.” So, yeah, I was beating — I refused to sign. They put my hand on the paper; they signed it themselves. I said, “No, that doesn’t count. I have to sign with my — like, willingly.”

AMY GOODMAN: And when you talked about a bounty being paid to the warlords who handed you over to the U.S. CIA and then you were tortured at a black site, do you know where that black site was? And when you say “tortured,” what actually happened to you in that two-month period? If I — I hate to bring you back there, but what actually happened?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, I don’t know where — until that day, I don’t know where the black site is, where that place. But I was kept, before that, at one of the warlord home. I was treated like a guest, teaching his kids classes — math, Qur’an and so on. And after that, I was — when the Americans came, they stripped naked. They put me in the bag, hooded, and they shipped me to somewhere I don’t know, ’til that day.

So, in the black site, it was one of the worst experiences in my life. Sometimes I’m afraid to get back there, because — not because fear. It’s just, you know, to relive that trauma, because there was no limit to whatever they can do to us, 24 hours.

AMY GOODMAN: And these were U.S. soldiers?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yes, U.S. soldiers and with also Afghanis, where people actually lost their life there, because they were looking for Osama bin Laden, where is Mullah Mohammed Omar, where are the new attacks, the sleeper cells. And they have a long list and photos and all kind of things.

So, yes, I mean, those black sites, I believe no one knows how many people in that ended there and how many people actually died there. But there was no limitation to whatever they can do to you. I mean, we spent — hang on the ceiling all the time, upside down, even blindfolded, naked. The food and drink, just pour rice and water in our mouth. Sometimes they — we also do our thing sort of standing, and there’s no rest. Twenty-four hours, there’s a programming, like sleep deprivation. We have only sleep — they give you 30 minutes, like, then six hours, then 20 minutes, if you can sleep — loud music, beating, waterboarding. They used to put us in kind of like a barrel and roll it in the ice and shoot. And the first time I did, I thought that I died, because they rolled it, and they shot with a gun. I, like, was looking: “Where are the holes?” But I was still alive. So, yes, I mean —

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you were taken from there to Kandahar, and then you were held where in Kandahar before being brought to Guantánamo?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: I think, Kandahar, we were at the airport. They have a detention — they built a detention prison in Kandahar. It was tents surrounded with like high walls of barbed wires. We could see the airplanes taking off every time.

So, when we saw — when we used to see the small airplanes, we knew they bring a new group of people. But we called — the big one, we called “the beast,” the Air Force really big one. So, that, when it comes, we all, like, panic, because we knew some people was going to leave, and they’re going to disappear. So, even that trauma, just waiting for your name or number to be — no, name — our name to be called.

They took us. And they call it a process station. Or they just drag me to that place, hang on the pole, strip naked, shaved. And there were all kind of humiliation, I mean, just too much to talk about it. So, we were packed on orange jumpsuits. Everything was orange — shoes, socks, uniform, shirt, T-shirt, pants. Everything was orange. And they have also goggles, ear muffs. My mouth was duct-taped, my eyes, too, also then hood. And they put one more thing upon me special, because as a big fish: They put a sign around my neck which said, “Beat me.” So, every 15, 10 minutes, I get beaten all the way for the next over 40 hours, until we arrived at Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did they say you did? What were the charges against you?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, at the black site, I was accused to be an Egyptian. They asked me I was in Nairobi and was recruiting, money laundering, I was al-Qaeda camp — head of the camp, trainer, a commander — all kind of accusations. I tried to deny them, but I admit to everything, you know? But the problem was with the details. I couldn’t give them the details. By the end, like two months and a half, when they found out I wasn’t that person, they just throw me in Kandahar detention. And from Kandahar, the same files were sent with me, where the interrogation started again about the same person, and in Guantánamo over and over and over again.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, I want to just be very clear: You were 18 years old.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah, I turned — I was 18 years old when I was kidnapped. I turned 19 in the black site.

AMY GOODMAN: So, your time at Guantánamo, Mansoor — first of all, your English is excellent. Where did you learn English? Did you speak English in Kandahar? Did you learn English in the black site and when you were being tortured and then at Guantánamo for the more than decade that you were held there?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: In the black site in Kandahar, all I learned, how to stay alive. You know, that’s it, just try to survive, try to stay — I tried to hold to little hope I had that place. But I learned — you know, in Yemen, in school, we studied English, but very basic. Also, before Guantánamo, I worked in Yemen in a security company. I used to work in the German Embassy and Dutch Embassy. But my English was very, very basic. And the black site even made me forget my name and my family and everything.

When I arrived at Guantánamo, I started to learn English in 2010, when we moved from the Dark Age to the Golden Age, when the White House became the Black House. Sorry, guys, that’s what we called it. So, I learned my — basically learned, yeah, in Guantánamo and after 2010. And we also found a businessman there. We had a class with one of the brothers who lived in the United States for 17 years. He taught us English and business. And we prepared some feasibility report, Yemen Milk and Honey. It’s a business plan. I’ll send you guys photos.

AMY GOODMAN: When did you start writing Don’t Forget Us Here, your story, your life in Guantánamo, the subtitle, Lost and Found at Guantánamo?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, before that, I lived it second by second, moment by moment, breath by breath. That’s what I did. Secondly, after 2010 — in 2009, I was assigned for the first time for a lawyer, Andy Hart. He was my friend. He died in 2013, one of the good people I lost at Guantánamo. Anyway, I started writing Arabic, letter — as stories to Andy Hart. And he loved it, and he encouraged me. But I also — when I started learning English, I used to write in Arabic, then translated it into English. It took me a long time.

So, one of the funny stories, when I started learning English, I had a book called Around the World in 80 Days, in like Arabic-English. I used to read with the guards. “Hey, MP, can you please help me in learning English?” I would read a half page and go — we had only one dictionary in the block — and go to check for the words. And I spent six months to finish the book. So, the guards and brothers used to make fun of me. They said, “Mansoor, have you finished your trip? That guy finished in 86 days — in 80 days.” I said, “No, I haven’t found my sweetheart yet. When I find her, the [inaudible] will finish.”

So, one of the guards, nice guards, he saw me. I didn’t have a dictionary. He brought me the first dictionary as a gift, was Webster. So Webster also helped me to learn.

I wrote the first draft from 2010 until 2013. But in 2013, when the camp administration locked down the camp and they canceled the communal living, they confiscated everything. Actually, they restarted Guantánamo. We went back to the — even worse than the Camp X-Ray. Everything was taken. We were stripped naked, brought orange jumpsuit, and they took our books, our letters, our artwork, everything. They took my drafts. I have two drafts, another book, too, documentary. I was screaming, “Bring my baby! I need my child!” So, they refused to give it back. Then, again, in —

AMY GOODMAN: This is during — this is under President Obama.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah. We called it the Golden Age during Obama, because, as you know, Obama signed an executive order to close Guantánamo in 2009. But deep inside me, I wanted to believe, but I had a feeling it’s not going to happen. When they found out Guantánamo is now going to be closed, they relaxed the rules. They didn’t change the rules. You know, Americans are very smart, you know? We were on — I was on force-feeding for three years. And there is many of us. So we initiated a deal with the camp administration to improve the life, healthcare. We asked for classes, art class, English class, TVs, better food, better healthcare, phone calls with our families. Actually, almost like most our demands were met, but the trick, they wanted to calm us down. It’s not because they wanted to improve things.

So, during that time, we had a little peace. I started to write my memoir. But again, in 2013, when the Army came, they closed the communal living. Again, they took everything, because they weren’t happy about how we lived. In 2015, I get a lovely lawyer, Aunt Beth Jacob. When I met her, I used to go to the classroom while chained and shackled to the floor. I started writing again my memoir, but by that time in English, in the cursive writing. Every week I would write like 20 pages, 25 pages, and send them to her as legal mail. She collated all the letters. And again, she — because all the letters have to go to the secure facility in Washington. She will collect all the letters and send them back to Guantánamo, where they again get to be screened and read again. And the book was — the draft was approved.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, he’s author of the memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. When we come back, Mansoor will talk about how he survived the prison and why he repeatedly went on hunger strike.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We’re continuing our conversation with Mansoor Adayfi, imprisoned by the United States at Guantánamo for 14 years, author of the new memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: What people — most people don’t know about the purpose of Guantánamo. Let me, like, talk just a little. Guantánamo, as you know, it was outside of the law. They call it the island outside of the law. So, the purpose of Guantánamo wasn’t about making Americans safe or about safety or security. You know, it wasn’t that purpose. So, we were called detainees. And as you know, international law doesn’t apply. The Geneva Convention doesn’t apply. American law doesn’t apply. Cuban law doesn’t apply. Nothing applied at that place. It’s just a dark hole, a black site within the military base.

So, when General Miller arrived by the end of 2002, he’s the first one who wrote the camp SOP, standard operation procedure, and he was the first one who started developing what they call enhanced interrogation technique, enhanced torture technique. So, we were kept in solitary confinement, experimented on, punished, everything utilized as experiment — our religion, our daily life, food, clothes, medicine, talk, air. Everything was used in those experiments. Also, there was a psychologist who supervised those experiments.

You know, there was around — as you know, around 800 detainees from 50 nationalities, 20 languages spoken. You know, Amy, the youngest detainee was only 3 months old. They brought him with his father. He was kept in the hospital. The oldest detainee was 105 years old. That man was my neighbor. And that’s what hurt me most at Guantánamo, seeing that man, at that age, treated like the same I was treated. I couldn’t take it. I had to fight every day with the guards to stop treating that way.

So, yes, General Miller was — his job — there is research called “Guantánamo: America’s Battle Lab,” talk about how Guantánamo was turned into experimenting lab on detainees. So, even not just us, there is a chaplain I think you know about, James Yee. I met him in Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: James Yee —

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: — was the chaplain at Guantánamo who would come out and talk about what happened there.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: No, before, what happened to James Yee at Guantánamo shocked and surprised us all. I remember, the first time I talked to James Yee, I was taken to the interrogation room, stripped naked, and they put me in a — we call it the satanic room, where they have like stars, signs, candles, a crazy guy come in like white crazy clothes reciting something. So, they also used to throw the Holy Qur’an on the ground, and, you know, they tried to pressure us to — you know, like, they were experimenting, basically. When I met James Yee, I told him, “Look, that won’t happen with us that way.”

James Yee tried to — he was protesting against the torture at Guantánamo. General Miller, the one who was actually developing enhanced interrogation technique, enhanced torture technique, saw that James Yee, as a chaplain, is going to be a problem. So he was accused as sympathizer with terrorists. He was arrested, detained and interrogated. This is American Army captain, a graduate of West Point University, came to serve at Guantánamo to serve his own country, was — because of Muslim background, he was accused of terrorism and was detained and imprisoned. This is this American guy. Imagine what would happen to us at that place.

So, when they took James Yee, we protested. We asked to bring him back, because the lawyers told us what happened for him after like one year. We wrote letters to the camp administration, to the White House, to the Security Council, to the United Nations — to everyone, basically.

AMY GOODMAN: When you talked about General Miller, just for people who might not remember, he, who oversaw the enhanced interrogation techniques — that was the euphemism for torture at Guantánamo — then brought from there to Iraq to Gitmoize Abu Ghraib there, to bring those same torture techniques there. And when the Taguba Report came out, it cited Miller for the massive level of abuse at Abu Ghraib. So, in that period, I mean, Mansoor Adayfi, you write so powerfully about what sustained you, about the relationships you had, not only with other prisoners — or, as you say, detainees — but with guards, as well. Can you talk about that?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, Amy, let me go a little like — I’d like to make a point here. First of all, we, as prisoners, or detainees, we weren’t just the victims at Guantánamo. There are also guards and camp staff, were also victims of Guantánamo itself. You know, that war situation or condition brought us together and proved that we’re all human and we share the same humanity, first.

Also, Amy, a simple question: What makes a human as a human, make Amy as Amy, make Mansoor as Mansoor, makes the guys in there as individual and person, you know? What makes you as a human, and uniquely, is your name, your language, your faith, your morals, your ethics, your memories, your relationships, your knowledge, your experience, basically, your family, also what makes a person as a person.

At Guantánamo, when you arrive there, imagine, the system was designed to strip us of who we are. You know, even our names was taken. We became numbers. You’re not allowed to practice religion. You are not allowed to talk. You’re not allowed to have relationships. So, to the extent we thought, if they were able to control our thought, they would have done it.

So, we arrived at Guantánamo. One of the things people still don’t know about Guantánamo, we had no shared life before Guantánamo. Everything was different, was new and unknown and scary unknown, you know? So, we started developing some kind of relationship with each other at Guantánamo between — among us, like prisoners or brothers, and with the guards, too, because when guards came to work at Guantánamo, they became part of our life, part of our memories. That will never go away. The same thing, we become part of their life, become memories.

Before the guards arrived at Guantánamo, they were told — some of them were taken to the 9/11 site, ground zero, and they were told the one who has done this are in Guantánamo. Imagine, when they arrive at Guantánamo, they came with a lot of hate and courage and revenge.

But when they live with us and watch us every day eat, drink, sleep, get beaten, get sick, screaming, yelling, interrogated, torture, you know, also they are humans. You know, the camp administration, they cannot lie to them forever. So the guards also, when they lived with us, they found out that they are not the men we were told they’re about. Some of them, you know, were apologizing to us. Some of them, we formed strong friendships with them. Some of them converted to Islam.

I remember one of the female guards. We had really a younger brother. He was only 15 years old. You know, he would look scary all the time. During 2003 and ’04, the worst times, torture, she always would bring chocolate for him and told him, “Listen, everything is going to be OK. I have a brother at your age,” every time she came to work on the block, you know? I will never forget that moment, because even those guards, they are still humans, and they also were victims of Guantánamo machinery.

I remember one of the days when I was — I refused, as protest, to walk to the interrogation room. So they used to bring the FCE teams, forced extraction teams or raid teams. They would spray us, bring the dogs first, then pepper-spray, then kick our asses, then drag us on our back to the interrogation room. That day, the escort was a female. She was ordered to drag me. She said, “No.” And the watch commander told her, “Drag the detainee.” She said, “No.” They called the camp officer. When he came, he said, “Drag the [bleep] detainee!” She said, “I cannot do it.” And he told her, “Step aside.” The other guard came to drag me. I told her, “OK. You can do it. I don’t care,” because I didn’t want her to get in trouble. So, when they dragged me, I was like beeeep, beep. They kicked me in my back. So, she was forced to watch.

I mean, not just as — sometime, Amy, we used to fight for the guards, you know, especially when the communal living. The guards would stay outside in the heat. They didn’t have tents. We have to write letters to the colonel. Sometimes we have to protest, in many occasions, because the rule — the military rules is cruel. And they treat those guards as a product, not humans, you know? Even those guards, when they — some of them went to tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. When they came back, we saw how they changed. When I grew up and became my thirties, when they used to bring younger guards, I looked at them as like younger brothers and sisters, and always told them, like, “Please, get out of the military, because it’s going to devastate you. I have seen many people change.”

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, this is such an important point you’re making. You were there when you were 19, and you were still there in your thirties. And then the young people who were there, who were the guards, are the age you were when you first got there.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah, I mean, because I have — when I grew up at that place, when I saw how the guards came back, many of them were mentally devastated. You know, when you see a broken soul, it is painful than anything. You know, even the pain that touch your soul, it is worse than — it’s the most severe pain. I have experienced many pain — beating, torture, you name it. But the worst thing I experienced, them that touched my soul.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about the hunger strikes. You participated in these for years, and you were force-fed.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, Amy, we were in a place we tried to survive. As I told you, we had only each other. And there is no way — we tried to stop the torture, the abuses, the mistreatment. You know, we tried to find why we were held there and what was going to happen to us. So, when the first time, at Camp X-Ray, when they — they were harsh, stopping us from praying together. One day, they came. One of the brothers were praying. They opened his door. They beat him, and they threw the holy book onto the floor.

So, we — you know, this is the first protest together. So, we discussed amongst ourselves: What should we do? You know, OK, the first time I heard about the hunger strike — I never heard about it before — we went on hunger strike. It was — I spent nine days. It was a mean trying to survive, a mean — we were hurting ourselves. I always tell the people, you know, our bodies was the battlefield, because Americans torture us, abuse us and beat us on our bodies; also, we were torturing our bodies by hunger strike, by trying to resist. And I wrote about it, the hunger strikes. It was a slow journey to death, toward death. That’s hunger strike, you know?

They also become very experienced how to break the hunger strike. We spent almost — every year we had, like, to go through many hunger strikes, over and over, over and over again. We were force-fed in 2005, ’07, 2010, ’13. Some of the brothers, I spent — some of the brothers spent three years, five years, 10 years, 15 years. There are brothers ’til now force-feeding ’til that day.

AMY GOODMAN: And what was that force-feeding? Can you describe it? I remember, I mean, we’re just learning — we were just learning about what was happening at Guantánamo at the time, the tubes that were used, how big they were, that this was used as a form of torture, as well. What it meant when they were forced to stop force-feeding you?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, like as I told you, they were also — the doctors, they were experimenting on us. They used to bring — they tried to bring the hunger strike — I was one of the very first five detainees who was on the brink of death in 2005, before they approved the force-feeding. I remember when the camp commander came. He said, “Now the Congress approved the force-feeding.” When they took us, they bring tubes they took through our nose — our noses, like a drill, bleeding.

AMY GOODMAN: Through your nose.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah, through our noses to our stomach. At that time, we were in bed, you know? Then the situation got worse. They brought something called feeding chair, force-feeding chair, which, like, they tie our heads — eight points — our shoulders, our wrists, our waist, our legs on the force-feeding chair. Then they brought also really large — they call it 9 French tube, really, really large, and they put it through our nose. We were screaming, shouting. But “Eat!” That way. “Eat!”

In 2005, they forced all of us to stop the hunger strike. What they did, they used to force-feed us — regularly, they should for us twice a day, but when they wanted to break the first, the hunger strike, they used to feed us five times a day. Nobody could last. The tubers, they used to bring piles of Ensure and just pour in our stomach, one after another, one after another. If we throw up, it doesn’t matter. “Eat!” Eight hours to 12 hours in the force-feeding chair. They used to bring those —

AMY GOODMAN: This is to put the Ensure through your nose.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yes. You know, during — they used to pour the Ensure, one can. After we was to throw up — if you threw up, you would get more. They also used to mix some laxatives in the Ensure. We [bleep] on ourselves on the feeding chair. And we were taken to solitary confinement, really cold AC.

They said — I remember that time there’s a general who came. He said, “I was sent by the White House just to break your hunger strike.” The first time he met me, he said — he took my file — “Sir, 441” — he was so mean. Like, you can see in his eyes and words. He said, “I am here today to tell you, sir, eat. Because tomorrow there will be no talking.” I tried to explain to him why we were on a hunger strike. He said, like, “I don’t give a [bleep] about anything. Eat. Tomorrow, there will be no talking.” I didn’t last for two days. I stopped. I couldn’t take it. You know, it was too much.

In 2007, again, I went on hunger strike. Then I spent from 2007 to 2010 on force-feeding until things changed in the camp. And even, Amy, our hunger strike was viewed by the camp administration as a jihad. They said we are an al-Qaeda cell and launching jihad against the United States — the way how they understood our protest and hunger strike. And we told them, “This is our demand. You know, stop the torture, stop the interrogation, improve the living condition. And we need to figure out what’s going to happen to us.”

So, what they did, they used to also hide us when the ICRC came. I remember one day I was on force-feeding. The ICRC, his name Hatim, Sudani guy, he walked in the block and was like — on the force-feeding, I called him, “Hatim! Hatim!” He looked at me, and he covered his eyes. I said, “What’s wrong with you?” He said, “We are not allowed to see you in that way.” Even the ICRC at Guantánamo, you know, we asked them to leave many, many years. We boycott them. We give them official letters. We signed many letters asking them to leave Guantánamo, because being at Guantánamo as ICRC, it just give legitimacy to whatever Americans do here.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Mansoor Adayfi. He was Detainee 441 at Guantánamo, imprisoned without charge for 14 years and has written a memoir about his life, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. So, I then want to ask you about what happened in 2016; why, after 14 years without charge, in at 19 years old, now in your thirties, you were released; and how you ended up, a Yemeni man, in Serbia.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: I was brought for release. Then I was sent to Serbia against my will. I refused to come to Serbia. I was forced. They told me, “You have no choice. Either leave or rot in here.” Then, the ICRC, when I protest — I went on hunger strike protesting going to Serbia. The ICRC came, [inaudible]. They issued a new — Obama administration issued new rules: If any detainee accepted by any country, he will be forced to leave regardless. So, basically, I had no choice. They bought me with money, and they gave the Serbian government money to take me again. So, this is the game. We have no say.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you end up in Serbia. You end up in Belgrade. I was just listening to an interview that Frontline did with you. And when PBS partnered with NPR to do this documentary series, you did an interview with them. And ultimately, you were beaten for that interview. Can you explain what happened to you? This, not long after you got to Serbia.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, when they came to interview me, I was on hunger strike on my 25 days. I spent 48 days on hunger strike protesting my condition, because the agreement between the United States government and the receiving countries, it was a resettlement agreement, but when you arrived at the hosting countries, they said, “No, we had an agreement. We had a new contract to come here for two years. You’ll live in our countries under restrictions. Nothing. You have no education, no courses, no, no, no, no.” You know, they made us promises, especially in my case. I was recommendation to finish my college education. So I talked to my lawyer. I said, “I cannot live here. I cannot stay here. I want to leave.” So I went on hunger strike. When I was — even one of the universities, I was accepted. When they found out I came from Guantánamo, I was expelled. You know, this is one of the things that hurt me most after Guantánamo. So, I went on hunger strike.

When the Frontline came here, the first, we had — they went to the government. They said they were fine, and they were doing well. When they came to see me, I was on hunger strike. They were surprised. The first time, we had an interview. Then, the second day, some people came to my apartment, took me down. They would send me messages: “Stop lying. You are lying. You’re a liar. You’re a liar.” And so on. And, you know, I don’t want to cause any problem, because I didn’t know what to expect, because, as you know, the Serbians, they have their history with Bosnia in the 1990s. Scary place. So, then I disappear. Then I contact my lawyer. I contacted the Frontline, and we continue again.

And again, after the interview was aired, a Serbia newspaper really represented me in the worst way — newspaper, TV. I was arrested, interrogated, threatening to be entrapped. You know, I wrote a lot about it, and you’ll read it here. I don’t want to talk much detail this, because they’re going to kick my ass again. But what I have learned at Guantánamo, I will never keep silence, you know, because keeping silence only give the oppressor a mean to oppress you more. So, I will never keep silence. Whatever they do, I will keep — you know, because I have done nothing wrong. Even if I had done something wrong, there is a justice system. You cannot just beat people, arrest them or interrogate them because you have a power.

So, basically, yes, I mean, then, in 2018, they came to me. They said, “Now with the two years finished, you have the choice: to go to Saudi jail or to go to the refugee camp.” And that guy — his name is Nikola — told me, “Americans [bleep] you. The interview cost you a lot,” literally, word by word. And my lawyer was there listening to him. He was like, “What?”

So, yes. When I talk about our life after Guantánamo, we still live in Guantánamo 2.0. You know, just to let you know, Amy, I studied in another college. I will be graduating on the 29th of December. And my thesis is about rehabilitation and reintegration of former Guantánamo detainees into social life and the labor market. I have been doing a lot of research for the last five years. I have interviewed around 150 brothers released from Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: You can’t leave Serbia, Mansoor?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You remember when I told you the worst pain that touch your soul? You know, I wanted to get married. I found really a woman that I thought she is going to be my wife. The only thing — the only thing was like the piece of paper in a travel document where I can get married. So, I couldn’t travel, so I couldn’t marry. And finished.

Not just me. I think I’m lucky. There are — one of the brothers, Lotfi, he died last year. He had heart diseases. He was relocated from Kazakhstan to Mauritania, where they didn’t have a good health system. He needed to go to somewhere where he can — he’d be treated, because he needed emergency surgery. And his doctor told him, “You have only six months.” So, he needed $30,000. CAGE organized, raised fund for him. And they said his surgery will be covered. He needed just a travel document, either to travel to Tunisia or other country, just to have the surgery and get back. He lost his life. You know, it’s one of the saddest moments. Like, when I was talking to him, [inaudible] was talking to ICRC, was talking to human rights organizations, to governments, nobody cares. Simply, nobody cares.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi. When we come back, Mansoor will talk about how faith and art helped him survive Guantánamo, as well as why he insisted on having a woman voice the audiobook version of his new memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Is It for Freedom?” Sara Thomsen, here on Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue our conversation with Mansoor Adayfi. He was jailed by the United States at Guantánamo for 14 years. He’s author of the new memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. I asked him about reports that the Biden administration was considering holding Haitian refugees at Guantánamo.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Creating another Guantánamo, you know, I hope Western nations, United States and the Western nations can solve the crisis within the countries, that generation, that massive crisis of refugees, immigration and so on, because dealing with the symptoms is not going to help. You know, they should help the countries to have some kind of stability so that people can live their lives. Yeah, it’s one of the biggest crises in the 21st century, the massive immigration of refugees. But creating Guantánamo again, if brought us again, what’s going to happen to these people? How is it going to be treated? So, I hope it’s not — honestly, I tweeted about it. And I don’t want anybody to be detained in that place, especially the name of Guantánamo. I love Guantánamo. I have made peace with it. But the idea of Guantánamo, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let me ask — when you said, “I have made peace with it,” you held up your scarf, that’s orange, that’s wrapped around your neck right now as you speak to us. You were forced to wear orange from head to toe. Why wear orange now?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: I wear orange all the time, because at Guantánamo, when the psychologist and the ICRC told me, “Wow! If you see the orange color, you will be shocked, if you heard the [inaudible].” I said, “No, this is part of my life, and I will never let Guantánamo change me.” So, Alhamdulillah, I choose to fight to close Guantánamo and to try to help anyone who are wrongly detained or, you know, stripped his freedom, because I don’t want anyone to suffer the same fate I have suffered, although I have made peace with Guantánamo. I almost, like, every day talk about Guantánamo, write, talk, give interviews and so on. My other brothers, they don’t want to remember, because it’s like a trauma. It reminds yourself over and over again. But, for me, I took it in another way. And, Alhamdulillah, I have some kind of strength. Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala gives me strength. So, I would use that strength to support those helpless people and also to bring the truth about Guantánamo. So I use my 441 and my emails and my names everywhere. And I use the orange color all the time also to bring the awareness to the people the misuse of power, how can damage us as humans.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, if you can talk about how you survived through Guantánamo, what hope meant for you? And was it hope that kept you going, through the forced feedings, through the hunger strikes, through the beatings, through the torture? What got you through?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: First of all, Amy, faith as Muslims. The first thing, we stick to our faith as Muslims, because — before Guantánamo, I was studying in the Islamic Institute. That’s where I got the mission to go for research. So, most of us, even the U.S. government viewed us as terrorists, or the faith as source of terrorism. It’s not. First it’s our faith, stick to it, praise to Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala, knowing that everything in the hand of Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala, and Americans have nothing to decide our fate.

Secondly, we had each other, because we were kept at that place. We had no books, nothing, just totally disconnected from the world outside. So we had each other. I wrote about it. I wrote about it, a piece called “The Beautiful Guantánamo,” which is, I just took all the bad things, and I wrote about how we survived Guantánamo. Imagine, Amy, around 50 nationalities, 20 languages, different background. People who were at Guantánamo, they were artists, singers, doctors, nurses, divers, mafia, drug addicts, teachers, scholars, poets. That diversity of culture interacted with each other, melted and formed what we call Guantánamo culture, what I call “the beautiful Guantánamo.”

Imagine, I’m going to sing now two songs, please. Imagine we used to have celebrate once a week, night, to escape away pain of being in jail, try to have some kind of like — to take our minds from being in cages, torture, abuses. So, we had one night a week, in a week, to us, like in the block. So, we just started singing in Arabic, English, Pashto, Urdu, Farsi, French, all kind of languages, poets in different languages, stories. People danced, from Yemen to Saudi Arabia, to rap, to all kind. It’s like, imagine you hear in one block 48 detainees. You heard those beautiful songs in different languages. It just — it was captivating.

However, the interrogators took it as a challenge. We weren’t challenging them. We were just trying to survive. This was a way of surviving, because we had only each other. The things we brought with us at Guantánamo, whether our faith, whether our knowledge, our memories, our emotions, our relationships, who we are, helped us to survive. We had only each other.

Also, the guard was part of survival, because they play a role in that by helping someone held sometimes and singing with us sometimes. Also, we also had the art classes. I think you heard about the — especially in that time when we get access to classes, we paint. So, those things helped us to survive at that place.

Hope also. Hope, it was a matter of life or death. You know, you have to keep hoping. You know, that place was designed just to take your hope away, so you can see the only hope is through the interrogators, through Americans. We said, “No, it’s not going to happen that way.” So we had to support each other, try to stay alive.

Also, we lost some brothers. And I lost very good brothers in that place. It’s one of the hardest and saddest moments at Guantánamo.

And, hamdulillah, I managed — I don’t know if I survived, to be honest with you, because someone asked me last month — I had an interview with the — I had an interview last month. Someone asked me, “How did you spend your twenties and thirties?” I said, “I don’t know.” I didn’t know what this means, twenties or thirties. I am now at my late of my thirties, but I’m not sure yet. So, imagine I have a huge gap in our life, like 15 years ago until now five years now. And physically, you know, technically, practically — you know, technically, I feel like I’m 30, 38, 39, but, practically, I feel like I’m still in my twenties, this mentality. Even you can see in my behavior, the way I talk, the way — that’s who I am, actually. So we have this huge gap.

And when I was released, different society, language, community. Anyone I get to interact or friend with get arrested, interrogated. People stay away from us, because the stigma of Guantánamo. So, basically, but I’m trying now — I’m trying to make a life, to get married. Yeah, I can sing a song for you.

AMY GOODMAN: Yes, you said you’d sing two.

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah. The first one, when we, like, supporting, because, especially when General Miller arrived, he tried to crush us. The first day he arrived, he searched all of us, beat all of us, cavity search. You know, they put dogs, FC teams, pepper spray. It was like a message: “I am here. [bleep] those terrorists. I’m going to kick your asses.”

But at Guantánamo, we don’t treat people wrong. It doesn’t matter. The only thing we have with guards is respect for respect and [bleep] for [bleep]. It’s as simple as that. Not all of us, but a group of us. I am sorry for these words, but we are talking about Guantánamo.

So, because Guantánamo is designed to extract the worst of us, so when someone was to go to the interrogation or for torture, we tried to support him, you know, and we would sing for him. [singing in Arabic] And like around 48 — two blocks sometimes sing together collectively. It was like [inaudible] encouraging. It means —

AMY GOODMAN: And what did it mean? What did that mean?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: [speaking in Arabic] “Go, go with peace. May Allah grant you more peace and safety.” And when they came from appointment or interrogation or torture, or people can arrive at Guantánamo, new at Guantánamo, especially when a new group arrived at Guantánamo, we would say — we would welcome them, that songs. Imagine, you just new arrive at Guantánamo, and three blocks, around 150 detainees, sung for you. [singing in Arabic] It means, “Welcome, welcome, they who come.” Imagine when the brothers first time arrived, you sing for them. You know, it was like they were surprised. “Are they detainees, or they’re like living in kind of like kind of a beach, laying or something?” One of the brothers used to tell us, “We thought that you guys live in some kind of like lovely life, enjoying yourself.” Then, when they took the hood, “Whoa! It is cages.” I said, “What did you expect?” He said, “I heard the voice. I thought, like, everyone is happy, singing.” So, we can, like, give them the first impression that everything is OK.

AMY GOODMAN: Mansoor, last two questions. One is, you talked about the art classes that you took. Can you describe what art meant for you? And what did you create? What did you draw?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: You know, Amy, when we started negotiating with the camp administration in 2010, when we negotiated in 2009 and '10, we negotiated an art class. The camp commander said, “Art class? You guys are terrorists. You don't know how to paint.” So, we asked the brothers, “Can you paint, please?” The second meeting, we showed them. They were shocked and surprised. They said, “OK.” It was a process, the negotiation, asking over and over again.

But, Alhamdulillah, art class was one of the most important classes at Guantánamo, because it helped us to express ourselves. It was a mean, a way of escaping being in jail, because you need to escape that feeling. So, art connect us to the world outside. You can see the brothers. We paint sea, trees, the things we missed most, sky, the stars, you know, homes, deserts and so on. So, arts actually help us to connect to our life that we almost forgot. The art connected us to ourselves, because it brung that memories back. It connected us to each other.

It connected us to the guards. You know, when someone saw arts, it can, like, mutual admiration and love for arts. And some of the guards asked for the brothers to paint for them. They will give them like arts for gifts. Brothers used to teach guards arts. Same thing, guards who has background teach brothers.

Also, you know, in the arts, one of the brothers, Sabry, one of the artists [inaudible], he said, “Mansoor, wa alallahi, when I paint, I saw myself in that painting, like on the hill, on the boat, on the ship, on the sea, sometimes like running here and there.” So, he said, like, “It just takes my mind and calm people down.” And, you know, it was like a therapy, too.

Also, one of the things we did there, we had like a painting everywhere, ourselves, in the block. We actually changed the blocks to be like a hotel. You know, you can see the rooms, the paintings, the art, the signs. Everything changed, the life, because we needed to change everything to live in different — we didn’t [inaudible], but this is the way how we want things to be.

AMY GOODMAN: Mansoor, I wanted to ask you about your choice to have a woman voice your book. Usually, it’s the author, when a book is done through audio, that someone can listen to it. It’s either the author or an actor. But you chose to have a woman read, voice Don’t Forget Us Here. Why?

MANSOOR ADAYFI: Yeah. I remember, like, talking to Sam from Hachette — hi, Sam — Antonio and Julia, my agent. I said, “Guys, I need a woman — I want a woman to read my book.” “No, why? It doesn’t happen before. You know, typically, the man” — I said, “No, I want a woman to read my book.” “Mansoor, that doesn’t make any sense.” I said, “What makes sense about Guantánamo [inaudible] happened to us, you know? Men have been kidnapping me, torturing me, kicked my ass, imprisoned me. And, like, they have done a lot of things, you know? The one who treated us nicely was women, so I want a woman to read my book. So, why not?” At the same time, I told him, it is like kind of racism against women. So, first they send me some kind of like men. I said, “No, I don’t want. I want a woman to read my book.” So, when they found it turned out good, they said, “Well, it was a good idea.” I said, “I know. I told you.”

AMY GOODMAN: Former Guantánamo prisoner Mansoor Adayfi, author of the new memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo. He was speaking to us from Serbia.

Ilhan Omar. (photo: Mandel Ngan/Getty Images)

Ilhan Omar. (photo: Mandel Ngan/Getty Images)

“Saying I am a suicide bomber is no laughing matter,” the Minnesota Democrat tweeted. “[House Republican leader] Kevin McCarthy and [Speaker] Nancy Pelosi need to take appropriate action, normalising this bigotry not only endangers my life but the lives of all Muslims. Anti-Muslim bigotry has no place in Congress.”

Boebert made the remarks in her home district. To laughs and whoops, she joked about encountering Omar, one of the first Muslim women elected to Congress, in an elevator on Capitol Hill.

“I see a Capitol police officer running to the elevator,” she said. “I see fret all over his face, and he’s reaching, and the door’s shutting, like I can’t open it, like what’s happening. I look to my left, and there she is. Ilhan Omar.

“And I said, ‘Well, she doesn’t have a backpack, we should be fine.’ We only had one floor to go. I said, ‘Oh look, the Jihad Squad decided show up for work today.’”

That was a reference to the “Squad”, a group of prominent House progressives of which Omar is a member. Boebert, a far-right Trump ally and controversialist, has also used the term on the floor of the House.

In response, Omar said: “Fact. This buffoon looks down when she sees me at the Capitol, this whole story is made up. Sad she thinks bigotry gets her clout.

“Anti-Muslim bigotry isn’t funny and shouldn’t be normalised. Congress can’t be a place where hateful and dangerous Muslims tropes get no condemnation.”

In the face of widespread condemnation, Boebert apologised “to anyone in the Muslim community I offended with my comment about Representative Omar”.

She also said she had “reached out to [Omar’s] office to speak with her directly. There are plenty of policy differences to focus on without this unnecessary distraction”.

Democratic House leaders including Pelosi indicated that was not enough.

“Racism and bigotry of any form, including Islamophobia, must always be called out, confronted and condemned in any place it is found,” they said in a joint statement.

“Congresswoman Boebert’s repeated, ongoing and targeted Islamophobic comments and actions against … Ilhan Omar are both deeply offensive and concerning … we call upon Congresswoman Boebert to fully retract these comments and refrain from making similar ones going forward.”

The statement also condemned as “outrageous” McCarthy “and the entire House Republican leadership’s repeated failure to condemn inflammatory and bigoted rhetoric from members of their conference”.

Another far-right Republican, Paul Gosar of Arizona, was recently formally censured for tweeting a video in which he was depicting killing Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, another leading progressive, and threatening Joe Biden.

Only two Republicans voted for censure: Liz Cheney of Wyoming and Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, who both broke with the pro-Trump wing over the Capitol attack.

On Friday, Kinzinger called Boebert “trash” and said: “I take sides between decency and disgusting.”

Perhaps alluding to McCarthy’s silence on controversies involving pro-Trump figures, he wrote: “Ask some of the normal members when they last talked to Kevin? Been a while for most.”

On Friday evening another pro-Trump extremist, Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, tweeted that she “just got off a good call” with McCarthy.

“We spent time talking about solving problems not only in the conference, but for our country,” she said. “I like what he has planned ahead.”

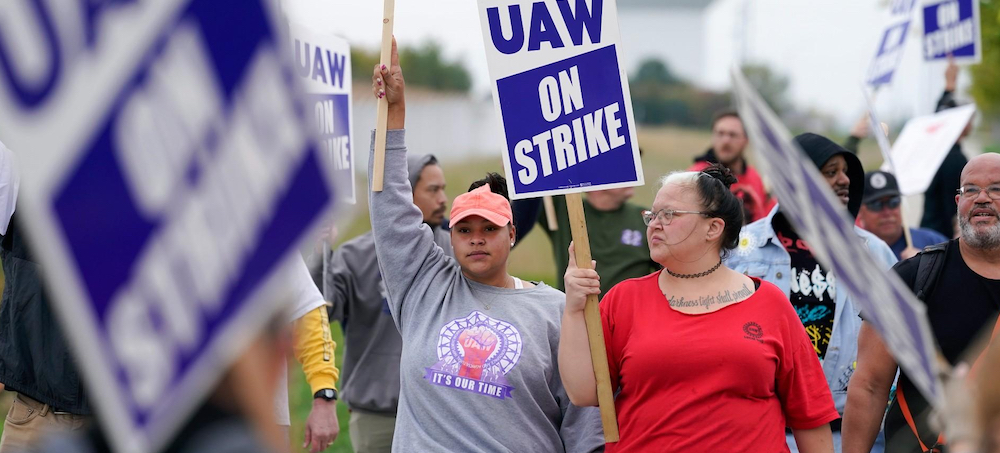

Members of the United Auto Workers strike outside of a John Deere plant in Ankeny, Iowa. (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

Members of the United Auto Workers strike outside of a John Deere plant in Ankeny, Iowa. (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

A strike by more than 1,000 Kellogg's plant workers is in its seventh week. There are ongoing walkouts by coal miners in Alabama. Health care workers in Northern California are also on strike. John Deere recently settled with 10,000 striking workers, as did Mercy Hospital in Buffalo, New York.

"Workers definitely have more labor market leverage because employers need to hire," said Johnnie Kallas, a project director at Cornell University's Labor Action Tracker. "They're understaffed and therefore workers have more bargaining power."

At Kellogg's four plants in the U.S., workers are demanding an end to a two-tier pay structure the union conceded to in 2015 that pays new hires lower wages indefinitely.

"We're professional cereal makers," said mechanic Dan Osborn, who is among 1,400 Kellogg's workers on strike. "We've been doing it our whole lives. And they're not going to get anybody better than that."

"I feel we have the upper hand right now," added James Jackson, a mine operator on strike.

Maintenance mechanic Robert Jensen pointed to Nebraska's unemployment rate —1.9%, the lowest for any state in recorded history.

"There just aren't enough skilled craftsmen to fill all these openings," Jensen said.

Kellogg's said the strike has forced it to begin replacing workers.

"The prolonged work stoppage has left us no choice but to begin to hire some permanent employees to replace those currently on strike," Kellogg's said in a statement to CBS News.

Even as the weather gets colder and picketing gets old, Osborn said the employees won't give up their fight.

"We'll stay out here one day longer than they are willing to," he said.

Paramilitary fighters hold their rifles during a ceremony to lay down their arms in Otu, northwest Colombia. (photo: Fernando Vergara/AP)

Paramilitary fighters hold their rifles during a ceremony to lay down their arms in Otu, northwest Colombia. (photo: Fernando Vergara/AP)

In a civil lawsuit, the court found that the paramilitaries operated in a “symbiotic relationship” with U.S.-funded Colombian forces.

Macaco led a group called the Bloque Central Bolívar in Colombia’s Middle Magdalena region; the BCB was dubbed“a killing machine” by another paramilitary commander. Its members murdered upward of 1,300 men, women, and children — a figure Macaco himself admitted to but is widely believed to be a conservative estimate. In the late 1990s, a number of paramilitary groups came together under the banner of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, or AUC in Spanish, a now-disbanded formation that the U.S. and several other governments listed as a terrorist organization. Macaco’s BCB forces made up the group’s largest and most violent unit.

In 2005, Colombia’s paramilitary groups laid down their arms as part of a justice and peace process that promised militant leaders sentences of no more than eight years in exchange for a full account and admission of responsibility for their crimes. Through that process, paramilitary commanders began to speak about their deep connections to Colombia’s military and political classes, implicating leading figures in the government of then-President Álvaro Uribe, a close ally of the United States. In 2008, the U.S. requested the extradition of Macaco and several dozen paramilitary leaders — relieving Uribe of uncomfortable revelations about the interdependence of the Colombian state and the paramilitaries, a relationship which the U.S. itself had enabled to the tune of billions of dollars in security assistance. (Macaco himself had benefited from U.S. support even more directly, as a palm oil company he owned had received funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development.)

While the atrocities committed by Colombian paramilitaries were well documented, the U.S. Department of Justice prosecuted those leaders over narcotrafficking charges exclusively — cutting short a Colombian effort to get tens of thousands of victims and their families a full accounting of the paramilitaries’ abuses. Macaco was convicted on drug trafficking charges and sentenced to 33 years in federal prison. His sentence was reduced in exchange for collaborating with U.S. prosecutors, and Macaco was released after 11 years and deported back to Colombia in 2019. While he continues to face murder and conspiracy charges in Colombia, he has not yet been found criminally responsible for any of the hundreds of murders he oversaw.

Macaco’s victims, many of whom have continued to push for an official recognition of his crimes, found a first glimmer of accountability earlier this fall: not in Colombia but in the U.S., where a Florida federal judge ruled against Macaco in a civil case filed on behalf of the family of one of his victims. Eduardo Estrada was a popular community leader and founder of an independent radio station whom paramilitary leaders ordered executed in the town of San Pablo in 2001. Once he was back in Colombia, Macaco halted contact with his U.S. attorneys, essentially dropping out of the case. The court awarded $12 million in damages to Estrada’s family, though they will likely never be able to collect the money.

Hugo Rodriguez, an attorney who last represented Macaco in 2015, told The Intercept that he had “serious doubt” a jury would have ruled against his former client. A different attorney who represented Macaco more recently did not respond to a request for comment.

“These cases are rarely about the actual collecting,” Claret Vargas, one of the attorneys who represented Estrada’s family, told The Intercept. “Often times they are about establishing a historical proof and about getting to confront the defendant with what they did. The idea is that the ruling itself is a form of reparation.”

The ruling is nonetheless significant in a number of other ways. It marked the first time a court in any country held Macaco responsible for one of the hundreds of murders carried out by the BCB. It was also the first judgment for murder and torture against a Colombian paramilitary leader in a case of its kind in the United States.

Perhaps most significantly, the ruling recognized a “symbiotic relationship” between the paramilitaries and the Colombian state. While such a relationship is hardly a secret in Colombia, it was the first time a U.S. court recognized it.

“A U.S. court has found that these violent, murderous, paramilitary regimes were basically the same as the Colombian government,” Daniel McLaughlin, another attorney who litigated the case, told The Intercept. “Which is the Colombian government that the U.S. was supporting at the time.”

Gustavo Gallón, the director of the Colombian Commission of Jurists, noted that the U.S. decision, even though it is a civil rather than criminal one, was a landmark moment in the push for accountability for the paramilitaries’ crimes. The commission had strenuously fought against Macaco and other paramilitary leaders’ extradition to the U.S., seeking the intervention of the International Criminal Court and of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, as well as lobbying senior U.S. officials to no avail.

“This is the first time we have got a decision in the United States about these people, and it is very important that judicial authorities in the United States have declared Macaco’s responsibility,” Gallón, who represents Estrada and other victims’ families in Colombia, told The Intercept. “There has been an important responsibility of the United States in the creation of paramilitary groups.”

A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Justice said that the extraditions “assisted Colombia in severing paramilitary leaders from their power base.” The spokesperson also noted that some of the extradited men continued to participate in Colombia’s justice and peace process through virtual appearances from the U.S. “To the extent Macaco did not cooperate, that would have been his choice, not as a result of extradition,” the spokesperson said, adding: “The Department of Justice was instrumental in ensuring Macaco returned to Colombia.”

A spokesperson for the Colombian Embassy in the U.S. declined to comment.

A Symbiotic Relationship

The civil case against Macaco was filed in the U.S. by the Center for Justice and Accountability, or CJA, a group that helps victims of human rights abuses worldwide seek justice in court. The decadelong litigation was filed under the Torture Victim Protection Act, U.S. legislation passed in the early 1990s that grants both U.S. citizens and foreigners the right to bring civil claims over torture and extrajudicial killings committed anywhere in the world as long as the perpetrators are under U.S. jurisdiction, as was the case when Macaco was in U.S. custody.

The case against him hinged on a particular interpretation of the law that stipulates the crimes must have been committed “under actual or apparent authority, or color of law, of any foreign nation.” That requirement has traditionally excluded victims of paramilitaries and other nonstate actors, but the judge in Macaco’s case concluded that there was an “abundance of evidence” the BCB had operated in conjunction and coordination with the Colombian state.

The case could set a precedent for more civil litigation against paramilitaries and other nonstate actors to be filed in the United States, as well as impact ongoing cases. “Our case was pushing the limits of the state action requirement to say, ‘Paramilitaries that are operating in this symbiotic relationship with the state qualify as state actors,” said McLaughlin. “You could imagine other contexts where governments are using paramilitary groups to kind of do their dirty work.”

According to testimony presented to the court, the BCB’s first foray into San Pablo, Eduardo Estrada’s town, came in 1999, when the group massacred 14 civilians as state security forces, whom the paramilitaries had warned in advance of the attack, stood down. In the following years, the ties between official forces and the paramilitary group were on stark display: Police and the military provided information about suspected guerrillas to the BCB, who proceeded to target and kill them; the military sold weapons to the BCB, and police took bribes from the group in exchange for not investigating killings they had committed. Members of the BCB detailed those relationships at length in testimony they gave Colombian prosecutors as part of the justice and peace process.

The Colombian military and police received funding and training from the United States as they operated closely with paramilitary groups in their fight against left-wing guerrillas and quest for control of vast swaths of the country. That support was part of a $10 billion U.S. investment into what is known as “Plan Colombia,” a counternarcotics program that profoundly transformed the Colombian security landscape and effectively enabled the government-allied paramilitaries to flourish. For years, U.S. officials raised concerns internally that the Colombian government seemed to have little interest in curbing paramilitary violence and, in multiple occasions, appeared to promote it instead. But despite the warnings, the U.S. government continued to fund Colombian security forces.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of State wrote in an email to The Intercept that “support through Plan Colombia has helped Colombia become a law enforcement leader in the region, to the point where Colombia now provides training and capacity building exercises to many other countries.”

In 2005, the umbrella paramilitary organization known as AUC disbanded. Its members let go of their weapons and embarked on a reintegration process that included a transitional justice initiative. When Macaco’s BCB, which had more than 7,000 members, disarmed, they handed over more than 5,000 firearms and 2,000 grenades, as well as four-wheel vehicles, motorcycles, aircraft, and boats. (Macaco, as the group’s general commander, oversaw the demobilization in military attire, court documents note.)

A year later, what became known as the “parapolitics scandal” rocked Colombia, exposing the deep ties between scores of the country’s politicians and the AUC. As the transitional justice process went underway, some of the demobilized paramilitaries — though not Macaco — began to speak about their ties to the military and to members of Colombia’s business and political elites.

“They spoke clearly about what they had done, and their justifications for their crimes, and their political project, because they thought that the AUC was a political project, that they were trying to protect the property and the security of places around the country against guerrilla attacks,” said Daniel Marín López, a transitional justice researcher and adviser to Colombia’s Truth Commission, which was established as part of the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, the largest left-wing guerrilla group in the country.

“That’s why they extradited them,” Marín López told The Intercept. “Because these commanders were starting to talk to the prosecutors, and for the political establishment it wasn’t a good idea to have these people talking. … They were talking too much, and the government didn’t want to have this kind of truth being released.”

The commanders’ revelations were a profound embarrassment not only to the Uribe government, but also to the U.S., where long-standing support for the Colombian government came under scrutiny.

“There was tremendous pressure on Uribe’s government to show that he had no links to the paramilitaries,” said Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli, director for the Andes region at the Washington Office for Latin America, a U.S.-based group that advocates for human rights in the region. “And so what did he do? He extradited all the Self-Defense Forces paramilitary commanders to the United States, including Macaco. He got rid of the heads of these groups.”

In May 2008, in the middle of the night to avoid the intervention of Colombia’s Supreme Court, the men were picked up from jails across the country and flown to the United States.

Whitewashing Paramilitarism

The extraditions dealt a huge blow to Colombia’s nascent transitional justice process.

“It was a catastrophe for Colombia’s peace and accountability,” Vargas, the attorney, told The Intercept.

Because U.S. prosecutors had agreed to extradite the paramilitary leaders on drug-related charges only, they could not prosecute them for other crimes, and the paramilitaries’ victims were largely excluded from proceedings in the U.S.

“The U.S. government had a choice to not ignore the victims — it wasn’t unknown to them that these people were responsible for atrocities and not just drug trafficking offenses,” Vargas said. “What the victims want is to know: If their loved ones have disappeared, where are they? Or if they were found or killed, what happened to them? And if they know what happened to them, they want to know why. And they never got access to that information.”

Extradition requests, particularly over narcotrafficking charges, have long been a staple of the U.S. war on drugs and have occasionally resulted in diplomatic disputes with foreign governments, including, recently, Mexico. The Colombian paramilitaries’ extradition was unique, however, because there was a truth and justice process underway, and there was widespread opposition to the prospect of the U.S. whisking the perpetrators away. “This case was literally about thousands of killings, including multiple massacres,” said McLaughlin, the attorney. “The victims had already given up so much: All [the paramilitary commanders] could get was at most eight years in prison — as long as they told the truth.”

That moment of truth never came, and for the most part, there was no mention of the paramilitaries’ crimes during their legal proceedings in the United States. U.S. prosecutors did not consider hundreds of slain Colombians to be victims of drug conspiracies, said Roxanna Altholz, a human rights attorney who fought for years to have the testimonies of the families of victims included in U.S. criminal proceedings against paramilitary leaders.

The Justice Department “tried very high-level state and cartel officials for drug conspiracies, and those prosecutions have absolutely failed in holding those individuals accountable for the violence they perpetrated in their countries of origin, and that is a horrendous omission,” Altholz, who authored a detailed report about the extraditions, told The Intercept. Individuals responsible for hundreds of murders were tried in the U.S. “for pounds and ounces,” she added. “That’s an enormous disservice to the victims and their families in Colombia. It’s a denial of the value of their lives.”

After a seven-year legal battle, Altholz managed to get the family of Julio Henríquez Santamaría, another Colombian community activist slain by the paramilitaries, to testify in the narcotrafficking case against the extradited leader responsible for his torture and death, Hernán Giraldo Serna. Altholz’s clients were the first foreign victims of a drug conspiracy to be recognized by a U.S. court.

Meanwhile, extradition to the U.S. became a sought-after solution for Colombians facing serious criminal charges back home — a reversal of what had long been steadfast opposition to being transferred to the U.S. to face justice. “In the 1990s, one of the main crusades of drug traffickers such as Pablo Escobar and people from the Cali Cartel was against extradition. People had this mental framework that extradition was the worst thing that could happen to you,” said Marín López, the human rights researcher. “But drug traffickers today find that extradition is the most lenient penalty they can get: Because they can make some kind of deal with the [U.S.] Justice Department, they can maintain their assets in their country, and they can have some special protection in the United States. Right now, it’s a very good deal to be extradited.”