Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

When conservative men like Rittenhouse and Brett Kavanaugh express their feelings, it is an act of thwarted entitlement – or a threat

Rittenhouse was 17 at the time of the shooting; he is 18 now. The young man’s emotional testimony had a practical purpose: it was a performance meant to make him seem helpless and childlike, and to convince the jury in his homicide trial that there was a reasonable possibility that he was in fear for his life when he shot the three men. But to many, the emotion of Rittenhouse’s testimony seemed to stem not from his memories of the incident, but from the indignant entitlement of a white man thwarted in the enforcement of his own privilege.

Many compared Rittenhouse’s tears during his testimony to those of Brett Kavanaugh, who shouted, red-faced and spitting, during his confirmation hearings, when he was asked questions about his alleged assault of Christine Blasey Ford, back when he was Rittenhouse’s age. Both of the displays prompted questions about their sincerity and opportunism. Was Rittenhouse really crying? Was Kavanaugh just putting on a show for Donald Trump to watch on TV? But they both also pointed to a peculiar phenomenon that remains little understood: the rightwing use of public displays of white male emotionalism as a political tool.

In one sense, the two men’s conduct under oath was quite strange. Both of them appear to be self-conscious avatars of white conservative masculinity, and their ideology would seem to preclude male emotionalism, as traditional gender norms have historically justified male dominance precisely because of men’s supposed stoicism and self-control. As Vox’s Jamil Smith put it: “We’re generally unfamiliar with seeing boys and men exhibit their emotion in such a public way. Vulnerability and common conceptions of manhood, especially among conservatives, have not traditionally been bedfellows.”

And yet conservative white men’s emotions are increasingly coming to the forefront of political life, and they seem to animate much of the Trumpist right. In practice, such men express their emotions all the time. They express them at Trump rallies, when they jeer at the mention of perceived enemies and cheer for lines of chauvinism and anger. They express their feelings when they picket abortion clinics, screaming at women walking inside and threatening the staff. They express their feelings when they fly Confederate and “Blue Lives Matter” flags; they express their feelings when they vote, and when they pick petulant fights with the service workers who ask them to wear their masks inside stores and restaurants. The common thread in these rightwing expressions of masculine emotion is that when conservative men express their feelings, they don’t do so as a gesture of humility or need. Instead, they wield their feelings as a threat.

Arguably, both Rittenhouse and Kavanaugh were expressing their emotions when they committed their famous acts of alleged violence. It’s impossible to know what was in his mind, but Rittenhouse’s actions leading up to that night in Kenosha indicate that what brought him there was anger, or maybe a desire for glory. Rittenhouse says that he came to Kenosha to protect local businesses from demonstrators; he had appointed himself a vigilante, out avenging the interests of property and police against the protests. It’s hard not to suspect that he daydreamed about himself as a lone wolf who doesn’t play by the rules, like an action movie hero who wears a bandana as a headband and a cutoff denim vest. The rifle that Rittenhouse used to kill Rosenbaum and Huber was illegal for him to possess. Asked why he didn’t use a handgun, he told the court that he had chosen the semiautomatic rifle because “it looked cool”.

For Kavanaugh, the project of decoding his emotions the night he allegedly assaulted Christine Blasey Ford is also speculative, but Ford’s testimony, along with documents made public during the hearings, paints a portrait of Kavanaugh as a young man with a vivid, if not especially varied, emotional life. His calendar from what was probably the month of the party shows him working out and calling his football friends by nicknames; he goes to their houses for “’skis” (“brewskis”: beers). In Ford’s account, he sounded satisfied with himself. “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter,” she said. “The uproarious laughter between the two, and their having fun at my expense.” Kavanaugh was a boy, like Rittenhouse, with an inflated sense of his own importance. The emotion he seemed to have expressed most clearly in those years was a consuming and profoundly unearned sense of his own superiority.

The fact of the matter is that for Rittenhouse, the question of emotion will be central to his case. The question of his legal guilt or innocence hangs on whether he felt endangered at the time of the shootings – a subjective experience that, conveniently, only Rittenhouse himself can speak to. Meanwhile, Kavanaugh now sits in a position of superlative power. Maybe the problem is not that these white men don’t express their feelings enough. Maybe the problem is that their feelings have too much power.

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

Republicans are vying for critical positions in many states – from which they could launch a far more effective power-grab than Trump’s 2020 effort

If they overruled the will of 81 million voters by blocking Joe Biden’s certification as president in a bid to snatch re-election for the defeated candidate, Donald Trump, “it would damage our Republic forever”.

Five minutes before he started speaking, hundreds of Trump supporters incited by the then president’s false claim that the 2020 election had been stolen broke through Capitol police lines and were storming the building. McConnell’s next remark has been forgotten in the catastrophe that followed – the inner sanctums of America’s democracy defiled, five people dead, and 138 police officers injured.

He said: “If this election were overturned by mere allegations from the losing side, our democracy would enter a death spiral. We’d never see the whole nation accept an election again. Every four years would be a scramble for power at any cost.”

Eleven months on, McConnell’s words sound eerily portentous. What could be construed as an anti-democratic scramble for power at any cost is taking place right now in jurisdictions across the country.

Republican leaders loyal to Trump are vying to control election administrations in key states in ways that could drastically distort the outcome of the presidential race in 2024. With the former president hinting strongly that he may stand again, his followers are busily manoeuvring themselves into critical positions of control across the US – from which they could launch a far more sophisticated attempt at an electoral coup than Trump’s effort to hang on to power in 2020.

The machinations are unfolding right across the US at all levels of government, from the local precinct, through counties and states, to the national stage of Congress. The stage is being set for a spectacle that could, in 2024, make last year’s unprecedented assault on American democracy look like a dress rehearsal.

The Guardian has spoken to leading Republican election experts, specialists in voting practices, democracy advocates and election officials in swing states, all of whom fear that McConnell’s warning is coming true.

“In 2020 Donald Trump put a huge strain on the fabric of this democracy, on the country,” said Ben Ginsberg, a leading election lawyer who represented four of the last six Republican presidential nominees. “In 2024 the strain on the fabric could turn into a tear.”

Since Joe Biden was inaugurated on 20 January, Trump has dug himself deeper into his big lie about the “rigged election” that was stolen from him. Far from cooling on the subject, he has continued to amplify the false claim in ever more brazen terms.

Initially he condemned the violence at the US Capitol on 6 January. But in recent months Trump has emerged as an unashamed champion of the insurrectionists, calling them “great people” and a “loving crowd”, and lamenting that they are now being “persecuted so unfairly”.

Trump recorded a video last month praising Ashli Babbitt, the woman shot dead by a police officer as she tried to break into the speaker’s lobby, where Congress members were hiding in fear of their lives. Babbitt was a “truly incredible person”, he said.

Michael Waldman, who as president of the Brennan Center is one of the country’s authorities on US elections, told the Guardian that Trump was normalizing the anti-democratic fury that erupted that day.

“He has gone from being embarrassed to treating 6 January as one of the high points of his presidency. Ashli Babbitt is now being lionized as this noble martyr as opposed to a violent insurrectionist trying to break into the House of Representatives chamber.”

Over the past year Trump has spread the stolen election lie far and wide, telling supporters at his regular presidential campaign-style rallies that 2020 was “the most corrupt election in the history of our country”. He has used his iron grip over the Republican party to cajole officials in Arizona, Pennsylvania, Texas, Wisconsin and other states to conduct “audits” of the 2020 election count in further vain searches for fraud.

One of the most eccentric of these “audits” (or “fraudits”, as they have been called) was carried out in Arizona by a company called Cyber Ninjas, which had virtually no experience in elections and whose owner supported the “Stop the Steal” movement. Paradoxically, even this effort concluded that Biden had indeed won the state, recording an even bigger margin for the Democratic candidate than the official count.

The idea of the stolen election continues to spread like an airborne contagion.

A poll released this week by the Public Religion Research Institute found that two-thirds of Republicans still believe the myth that Trump won. More chilling still, almost a third of Republicans agree with the contention that American patriots may have to resort to violence “in order to save our country”.

Waldman said the big lie is now ubiquitous. “The louder Trump yelled the more his supporters thought he was telling the truth. Increasingly the institutional machinery of the Republican party is organized around fealty to the big lie and the willingness to steal the next election, and that is terrifying for the future of American democracy.”

Ned Foley, a constitutional law professor at Ohio State University, said the current moment is “unique in American history”. He called it “electoral McCarthyism”.

Foley sees parallels between Trump and the anticommunist panic or “red scare” whipped up by senator from Wisconsin Joe McCarthy in the 1950s. “What’s unique about Trump and about what he’s trying to do in 2024 is that he’s applying McCarthy-like tactics to voting, and that’s never happened before.”

Electoral McCarthyism is being felt most acutely at state level. In several of the battlegrounds where the 2024 contest largely will be fought and won, a clear pattern is emerging.

Trump has endorsed a number of Republican candidates for key state election positions who share a common feature: they all avidly embrace the myth of the stolen election and the lie that Biden is an impostor in the White House.

The candidates are being aggressively promoted for secretary of state positions – the top official that oversees elections in US states. Should any one of them succeed, they would hold enormous sway over the running of the 2024 presidential election in their state, including how the votes would be counted.

To get into these positions of power, the candidates are challenging incumbent election officials who were seminal in thwarting Trump’s bid to overturn the 2020 election result. This is most evident in the critical state of Georgia. Brad Raffensperger, the secretary of state, resisted the sitting president’s demand, made during a phone call, that he “find 11,780 votes” for Trump – one more vote than Biden’s margin of victory.

Raffensperger is now facing a tough fight against Jody Hice, a US Congress member boosted by Trump’s backing. Hice was among the 147 Republicans in Congress who voted on 6 January (hours after the insurrection) to overturn election results, falsely claiming widespread irregularities.

In Arizona, another critical swing state, many Trump allies are running for secretary of state, including Shawna Bolick.

She was the architect of a bill introduced to the Arizona state legislature that would have given lawmakers the ability to overturn the will of voters and impose their own choice for president. Under Bolick’s bill, legislators would be able to overrule the official count and put forward an alternate slate of electors in the name of the loser by dint of a simple majority vote, no explanation needed.

Had that provision been in place in 2020 it would have allowed the legislature’s 47 Republicans to override 1.7 million Arizonans who had voted for Biden and send their own alternate slate of Trump electors to Congress instead.

Bolick’s bill did not pass. But it gave a clear indication of Trump acolytes’ thinking as they inject themselves into the election process.

Competing against Bolick to be the next secretary of state of Arizona is Mark Finchem, who Trump has also endorsed. Finchem was at the Stop the Steal rally in Washington on 6 January that turned into the Capitol insurrection.

Finchem, a former police officer, has links to the far-right extremist group the Oath Keepers, which federal prosecutors allege was involved in planning the violence. On 6 January he posted a photograph of the ransacked Capitol building with the comment: “What happens when the People feel they have been ignored, and Congress refuses to acknowledge rampant fraud.”

If Finchem were to become secretary of state he would have a central role over certifying – or not – the results in Arizona.

In Michigan, another battleground state which Biden won by 154,000 votes in 2020, Trump has endorsed Kristina Karamo for secretary of state. A self-styled “whistleblower” and Fox News favourite, Karamo filed lawsuits in 2020 seeking to block Biden’s certification on spurious grounds of mass fraud.

The list goes on. Reuters analysed the records of 15 Republican candidates running for secretary of state in five battleground states, finding that 10 of them are avid “stop the stealers”.

The pattern of Trump loyalists agitating to take control of elections can be seen even at the hyper-local level. Steve Bannon, Trump’s former White House senior adviser, has used his War Room podcast megaphone to call on supporters to take over the reins of election administration “precinct by precinct”.

Boards of canvassers, normally unsung panels of local administrators operating at county level, are also being targeted. In Michigan, Republican stop the stealers are moving to oust seasoned election officials from the boards in many of the state’s largest counties, with possible ramifications for how future election results are certified.

Leading authorities on US elections watch these rapidly shifting tectonic plates with mounting alarm. Rick Hasen, a legal scholar who writes the Election Law Blog, told the Guardian that he is worried about what might happen should Raffensperger and other officials who stood firm against Trump’s electoral coup attempt in 2020 be cast aside.

“It took the courage of Republican elected officials who refused to do Trump’s bidding and overturn the election result to save us from a political and constitutional crisis. With those people removed from office, it’s harder to have confidence that the next presidential election is going to be run fairly.”

Chris Krebs led the federal cybersecurity agency Cisa in charge of protecting the integrity of the 2020 election until he was fired by Trump. He fears that the conspiracy theory of the stolen election has spread so rapidly that it is now beyond control.

“There’s a part of me that thinks perhaps we’re too far gone,” he said. “The stop the steal movement has metastasized into a broad base that is more powerful than any individual, even Trump.”

Democracy experts have focused their energies in recent years on the resurgence of voter suppression, the form of anti-democratic politics that arose out of the Jim Crow era of the 20th century. Those techniques have been on ample display this past year. The Brennan Center recorded that in the first six months of this year alone at least 30 new laws were enacted in 18 states making it harder for Americans to vote.

But now voter suppression has been joined by a new, and possibly even more sinister, antidemocratic threat: election subversion. The trusted outcome of a presidential election, which every four years Americans took for granted as the bedrock of their democratic way of life, appears at risk of being willfully distorted or even overturned.

“The largest concern I have right now is the potential for election subversion,” Hasen said. “That’s something I never expected to worry about in the United States.”

The nonpartisan group Protect Democracy and its partner organisation States United Democracy Center have recorded 216 bills introduced this year in 41 states that politicize, criminalize or interfere with election administration. Many of the bills seek to increase the power of Republican-controlled state legislatures over the election process, stripping powers from impartial election officials and handing them to radically partisan lawmakers.

The largest concentration of bills fall in exactly those states that were most closely contested in 2020 and where the outcome of the 2024 presidential election is likely to be decided – Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Wisconsin and the increasingly competitive state of Texas.

“We know that some of these bills have been part of a coordinated effort,” Jessica Marsden, a lawyer with Protect Democracy, said. “We see similar measures pop up in a number of different states, so there is significant evidence that there is at least the beginnings of some sort of plan.”

So far 24 of the bills have been passed into law. They include a new voting law in Georgia that came into effect in August which the New York Times described as “a breathtaking assertion of partisan power in elections”.

The law tightens the grip of Republican lawmakers over the election board that oversees the vote count. It removes Raffensperger from his seat as chair of the board, which means that even if he survives next year’s challenge by Hice he will still have his wings clipped.

Under the law, the newly Republican-dominated election board gains the power to suspend county election officials. That is being seen as a thinly disguised power grab over the election processes of Fulton county, an area covering the heavily Democratic and majority-Black city of Atlanta.

Fulton county was seminal in handing victory to Biden. It also gave the edge to Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, in senatorial races that swung control of the US Senate to the Democratic party.

“Late at night during the passing of the voter bill in Georgia, Republicans snuck in a provision that could have the most devastating impact,” Waldman said. “It changes the rules of who gets to count the votes, taking away the power of the secretary of state and taking over county election processes on very flimsy grounds.”

For the past year Katie Hobbs, Arizona’s Democratic secretary of state, has been at the centre of the storm unleashed by Trump’s big lie. Attacks on Hobbs and her staff began straight after the November 2020 election and have continued unabated ever since.

Biden’s narrow victory in Arizona – by fewer than 11,000 votes – was vital in securing him the presidency. The controversial decision by Fox News to call the state for Biden as early as 11.20pm on election night provoked fury from Trump and his devotees that still reverberates in Arizona to this day.

Hobbs was one of those to feel their wrath. “We have been the target of a barrage of constant attacks. There have been threats, harassment and vitriol, not just against our election staff but to every department where people can find a phone extension to call,” she said.

Days after the presidential election, armed stop the stealers gathered outside Hobbs’ home. In May she and her family were assigned a security detail after she received three separate death threats in a single day and was chased outside her office by a man working for the conspiracy theory website Gateway Pundit.

“Security is certainly not something I expected as part of this job,” she said. Asked why she thought she was such a hate figure for Trump supporters, she said: “These folks think I’m going to be arrested, that I belong in Gitmo and deserve to be tried for treason – and they are reminding me of this every single day, without any evidence.”

Threats of violence are not the only challenge Hobbs has faced. In June, Republican lawmakers in the state legislature stripped her of powers to defend election laws in court, handing the critical function to the state attorney general, a Republican.

The move was later blocked by a judge on constitutional grounds. But Republican lawmakers have successfully weakened her role by barring her access to legal counsel, which severely curtails her ability to carry out her duties as the protector of Arizona democracy.

“They’ve tied my hands, and that’s been par for the course in terms of partisan retaliation throughout my term in office,” Hobbs said.

The Brennan Center reported in the summer that one in three election officials in the US felt unsafe in their jobs. One in six had received threats.

David Becker, executive director of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation and Research in Washington, said that professional election officials were increasingly stepping down, or preparing to do so, in the face of unbearable hostility.

“I have talked to election officials who have received threats containing the names of their children and schools they go to. These people are true public servants who are asking themselves is it worth it, because they are suffering. I’m talking about hundreds to thousands of election officials around the country who worry every night that they might be attacked as they go home.”

For every impartial election official who departs, there is a Trump loyalist waiting in the wings. “And they apparently view their oath not to the US constitution, but to a single individual,” Becker said.

And it doesn’t end there. Were the Republicans to regain control of the House of Representatives in 2024, Kevin McCarthy, the minority Republican leader, would have considerable sway as Speaker over how the outcome of the presidential election would be certified.

If a state legislature were to send an alternate slate of electors to Congress in an attempt to overturn the will of voters then McCarthy would be a pivotal player. His word would carry weight in determining whether to allow those alternate electors, potentially turning the result of the election on its head.

McCarthy was one of the 147 Republican rebels who on 6 January – hours after the storming of the Capitol – objected to the certification of Biden.

“Here’s one of my big concerns,” Hasen said. “The House of Representatives headed by Kevin McCarthy accepts alternate slates of electors and overcomes the will of the people, making the loser the winner.”

Such a move would undoubtedly trigger a constitutional crisis, which in turn would inevitably end up before the US supreme court. Here, too, there are reasons to be apprehensive.

In the runup to the 2020 election, four of the nine justices expressed some degree of support for the theory that state legislatures have the power to put forward their own alternate electors should they decide the official count somehow had failed. Trump nominated three new conservative justices during his time in the White House, tipping the balance on the court sharply to the right and increasing the likelihood that the conservative majority looks favourably on this highly questionable legal ruse.

“There could be five or six justices who could go along with it, given the right case,” Hasen said.

With 2024 on the horizon, democracy experts have identified several ways in which disaster could be averted. Rick Hasen wants new federal guardrails put in place to prevent state legislatures from interfering in elections for purely partisan reasons. Chris Krebs wants a more robust system of post-election audits to act as a legitimate counterpoint to the sham audits promulgated by Trump.

All the authorities on American democracy who spoke to the Guardian were united about the urgency of the moment. New protections need to be put in place, right now, or else the nation will enter the 2024 presidential election cycle with its democratic structures already bloodied and vulnerable to further attack.

Waldman looks to Washington for signs that the peril has been recognised, and that appropriate action is in train. He sees neither.

“The leadership of the federal government doesn’t appear to be treating this as the emergency it is. This is one of the great clashes in American political history. Where is the alarm?”

Rev. Cece Jones-Davis embraces a fellow activist on Nov. 1, 2021. (photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept)

Rev. Cece Jones-Davis embraces a fellow activist on Nov. 1, 2021. (photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept)

Persistent problems with lethal injection have not swayed the state’s determination to put Jones and five other men to death.

“We’re here to free an innocent man on death row,” Smith told me, adding that he wanted to raise awareness about other cases too. A few days earlier, on October 28, Oklahoma had carried out its first execution since 2015, killing a 60-year-old Black man named John Grant by lethal injection. Like the previous two men sent into the state’s death chamber — whose botched executions thrust Oklahoma’s dysfunctional capital punishment system into the national spotlight — Grant struggled before he died. Witnesses described how he vomited and repeatedly convulsed shortly after the lethal injection began. Yet officials denied that anything had gone wrong.

Now Jones faces the danger of a similar fate. Despite pending federal litigation over the state’s execution protocol — and a recommendation from the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board that Jones’s sentence be commuted to life in prison — Jones is scheduled to die on November 18 for a crime he swears he did not commit.

Jones was sentenced to death in 2002 for killing a white man named Paul Howell in an affluent suburb of Oklahoma City. The case rested largely on a single eyewitness account, along with the testimony of two confidential informants. Although the alleged murder weapon was recovered from his parents’ home, Jones insists that he was framed by his co-defendant, a former high school classmate named Christopher Jordan, who testified against him in exchange for a secret plea deal. Jordan was released after 15 years in prison.

Jones’s case was relatively obscure outside Oklahoma until 2018, when ABC aired a seven-part documentary series titled “The Last Defense.” Produced by actor Viola Davis, it laid out the case for Jones’s innocence — and catapulted his name into the public eye. Recent opinion polls taken from Oklahoma voters showed that 60 percent of those familiar with Jones believed that his death sentence should be commuted. Yet the publicity around his case has also sparked backlash from prosecutors and Howell’s family, who accuse Jones’s supporters of manipulating the public by misrepresenting the facts. After years of refusing interview requests, the family told a local TV station in September that they felt re-victimized by the celebrity-studded movement in support of Jones. “This is David versus Goliath,” Howell’s nephew said.

Around 8:15 a.m. on November 1, Rev. Cece Jones-Davis took the mic in the church parking lot. A minister and social justice activist, she had helped lead countless actions in Oklahoma City in the days before the clemency hearing. “What makes this different,” Jones-Davis told the crowd, “is that today Julius Jones gets to speak for himself.” After a prayer, the crowd turned out of the parking lot toward Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. Chanting and waving signs, they passed the headquarters of Oklahoma’s Department of Corrections, then arrived at another church.

Cars parked outside had “Justice 4 Julius” written on the windows. A spread of fruit, granola bars, and honey buns was laid out under a blue tent. Rows of folding chairs were arranged to face a women’s prison across the street, the location where the hearing would take place. A large set of speakers sat ready to broadcast the proceedings. “Julius Jones is innocent!” a man shouted from the crowd.

Among the country’s dwindling death penalty states, Oklahoma leads the nation in executions per capita. Although the state reflects national trends in residents’ waning support for capital punishment — and in the declining number of death sentences imposed year after year — Oklahoma remains a bastion in its willingness to carry out executions. “If you look at the states that are outliers in their zeal to kill, they are also the states that are outliers in their failure to provide fair process,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

Apart from Jones, five more men are set to die in Oklahoma between December and March 2022. Lawyers for those men are fighting largely under the radar to save the lives of their clients, whose cases reveal longstanding flaws with the death penalty, from ineffective lawyering to prosecutorial misconduct. According to Assistant Federal Public Defender Emma Rolls, head of the capital habeas unit of the Western District of Oklahoma, these cases also reflect “systemic failures resulting in generations of unbelievable poverty, childhood deprivation, mental illness, addiction, and trauma.”

Perhaps more disturbing is Oklahoma’s determination to kill the men despite persistent problems with its execution protocols — problems officials claim to have worked diligently to fix. “Oklahoma has had six years to think about how not to botch an execution and they squandered it,” said Dunham. In its rush to kill Jones, Oklahoma appears not only unbothered by its ugly death penalty history but also intent on repeating it.

In September 2015, Richard Glossip came within moments of being killed at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester when the execution was abruptly called off. Glossip swore he was innocent — and an investigation by The Intercept had found his conviction to be disturbingly flimsy, based almost solely on the account of a 19-year-old co-worker who admitted to killing the victim but blamed Glossip for coercing him. Yet Glossip’s execution wasn’t stopped due to the lingering questions about his guilt. Instead, prison officials explained that they had received the wrong drugs from their supplier, discovering the mistake at the last minute.

A grand jury report would later expose stunning incompetence and dishonesty on the part of state officials involved in the fiasco. Confronted with evidence that a man named Charles Warner had been previously executed using the same erroneously procured drug — his last words were “My body is on fire” — the governor’s general counsel pushed to kill Glossip anyway, lest they have to admit what had happened with Warner. Halting Glossip’s execution “would look bad for the state of Oklahoma,” he said.

Oklahoma had already made global headlines by then due to the horrifyingly botched execution of Clayton Lockett in 2014. Nevertheless, in 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Oklahoma’s lethal injection protocol, setting the stage for Glossip’s execution. Following the mix-up at the prison, however, executions were placed on hold.

In the meantime, the ruling in Glossip greased the wheels of other states’ execution machinery. Prison officials adopted protocols employing the same sedative used by Oklahoma, midazolam, despite warnings from experts that the drug would not render a condemned person insensate for the purpose of execution. Even more significantly, Glossip largely immunized death penalty states from further challenges to their lethal injection protocols. Under the ruling, people on death row who wish to challenge a state’s execution method must not only prove that it is unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment but also propose a viable alternative. The ruling put death penalty lawyers in the perverse position of proposing methods by which the state could kill their clients.

“Asking our clients to choose alternative methods for their own executions has been one of the most difficult experiences in my career,” said Rolls. “It is inimical to the instincts and beliefs of people committed to capital defense.” Still, this “pales in comparison to the anguish it has caused our clients. Many of our clients suffer from serious mental illness and cognitive limitations; they simply cannot understand how and why the law requires them to choose an alternative.”

In 2017, a special commission released a report that found problems in every corner of Oklahoma’s death penalty system and urged the state to correct “systemic flaws” before restarting executions. Instead, Oklahoma merely tinkered with its methods. In 2018, then-Attorney General Mike Hunter announced that the state would start executing the condemned using nitrogen gas. But in February 2020, Hunter changed course: Oklahoma would stick with the same three drugs it had used before but with “more checks and balances.” The drugs “have been successful in the past,” he said, “not only in Oklahoma but in numerous other states.”

For a while, both sides agreed that executions should remain paused pending federal litigation over the state’s revised lethal injection protocol. In July 2020, as required by Glossip, a group of men on death row outlined four alternative methods of execution, including the firing squad. But six of the plaintiffs did not answer an additional question. Prompted to check a box to indicate which execution method they would prefer, the six men left it blank.

This past August, U.S. District Judge Stephen Friot ruled that the lethal injection lawsuit could proceed, scheduling a trial for February 2022. But in a dark technicality, he dismissed the six men who failed to choose their preferred way to die. In a footnote, Friot all but invited the state to set execution dates for these men. Noting that “the parties would be well advised to be prepared, at trial, to present evidence as to the actual track record of midazolam,” Friot added that in light of the six plaintiffs who “declined to proffer an alternative method of execution, there may well be a track record … by the time this case is called for trial.” In other words, the men could make useful test subjects to determine the efficacy of midazolam.

On September 20, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals issued death warrants for all six men, including Jones. A seventh man, who was not part of the lawsuit, was also scheduled to die.

Pointing Fingers

Of the six men facing execution in the next few months, four, including Jones, were sentenced under former elected Oklahoma County District Attorney Robert “Cowboy Bob” Macy. Famed for aggressively seeking the death penalty — and infamous for prosecutorial misconduct — Macy, who served from 1980 to 2001, personally won 54 death sentences during his time in office.

The first man Macy ever put on death row, Clifford Henry Bowen, was accused of a triple murder based on the accounts of two eyewitnesses. After a dozen witnesses testified that Bowen was at a rodeo hundreds of miles away the night the crime took place, Macy suggested that perhaps Bowen had taken a private jet from the rodeo to Oklahoma City. The jury sent Bowen to death row. He was exonerated five years later.

To date, 11 people have been exonerated from Oklahoma’s death row, according to data collected by The Intercept. But the true number of innocence cases is impossible to know for sure. In 2001, as Jones waited to go on trial for his life, Oklahoma was forced to review some 1,200 criminal convictions won with the help of a fraudulent forensic scientist, whose work sent 23 people to death row. Twelve had already been executed.

Oklahoma County’s current district attorney, David Prater, worked under Macy. He has defended his old boss, arguing that it is inappropriate to view his record through a modern lens. But the culture and tactics of that office are reflected in the cases that are now coming up for execution, including Jones’s.

“I never trusted Bob Macy as far as I could throw him,” said Dennis Dill, a former police officer in Edmond, the Oklahoma City suburb where Jones was accused of killing Howell. Dill, who appeared in “The Last Defense,” is haunted by a different death penalty case tried under Macy — that of Jimmie Ray Slaughter, who was executed in 2005. In a phone call, Dill echoed what he said in the ABC series: that Slaughter was sent to death row by corrupt detectives who destroyed evidence and tried to get him to falsify a police report. Their conduct had moved him to speak up about Jones. “The same people that worked on this case worked on the Slaughter case,” he said. “They will focus on a direction and find only evidence to go that direction.”

Dill, who spent 24 years on the police force, was one of the first officers to respond to the murder of 45-year-old Howell on July 28, 1999. Howell, an insurance executive, had arrived at his parents’ home just after 9:30 p.m. after taking his young daughters out for ice cream when he was approached by a man as he was getting out of his GMC Suburban. The man shot him in the head at point-blank range. Howell’s sister, Megan Tobey, who was on the passenger side, glimpsed the shooter before fleeing the car with her nieces. She described him as a Black man in a white shirt and stocking cap, with a red bandanna covering his face. She said that she saw at least half an inch of hair coming out from under the cap.

Howell’s murder sent shockwaves through Edmond, where the majority of residents were white and well-off. A city council member and classmate of Howell’s described the neighborhood as a place where “getting a radio stolen out of a car would be a big deal.” For Black people, the city had a different reputation. “The Last Defense” includes an interview with a man who filed a lawsuit against the Edmond Police Department after a plainclothes officer allegedly put a gun to his head and called him the N-word. That officer, Tony Fike, investigated Howell’s murder alongside Edmond police detective Theresa Pfeiffer.

The stolen Suburban was found July 30 on Oklahoma City’s south side. When detectives approached a longtime confidential informant named Kermit Lottie, who owned a “chop shop” nearby, he pointed to a man named Ladell King, who had tried to sell him the Suburban. But King told detectives he was just a middleman. He said that on the night of the murder, two men had pulled up to his place driving separate cars: 20-year-old Jordan in an Oldsmobile Cutlass and 19-year-old Jones in the Suburban. It was only the next day after trying to sell the car that King said he saw a news report about Howell’s murder. He realized that the vehicle was linked to the murder — and that Jones was wearing a red bandanna and a stocking cap.

Dill, who said he was taken off the Howell case early on, remembers being skeptical. He was well acquainted with King, who had been an informant of his for years. “He knew if he started pointing fingers that he would get out of it,” Dill said.

Three days after the murder, Fike and Pfeiffer interviewed Jordan. There were signs that the detectives suspected Jordan might be the real shooter. “We don’t have this backward, do we?” Fike asked Jordan at one point. But the interview is most striking for how dramatically Jordan’s answers changed in response to detectives’ leading questions.

Jordan told detectives early on that he and Jones had been out together in the Cutlass the night of the murder when they spotted a Suburban driving behind them. Jones told Jordan to let him out of the car so he could “pop” it. Jordan said he did, then drove on to a taco place to get burritos. “I didn’t have nothing to do with it.”

But police told Jordan that his version of events didn’t make sense — or align with Howell’s known whereabouts that night. “He wasn’t in that part of town,” Pfeiffer said. Fike suggested that Jordan and Jones were out cruising around looking for a Suburban. Jordan denied it at first but then said it was true. As the detectives fed him more information, Jordan’s story evolved.

Where he’d previously said that he did not find out about Howell’s murder until the next day, now he said that he’d followed the Suburban into Howell’s neighborhood and let Jones out of the car. “So you followed him out, and you saw that man lying there on the ground, didn’t you?” Fike asked. Jordan said no, but Fike pressed him. “You saw him lying there, didn’t you? You knew he was shot right then, didn’t ya? Come on, Chris, you’re just a better witness that way.”

Jordan said he saw the man fall backward onto the ground. “How’d you know that he’d shot him? How’d you know he didn’t just hit him in the head or something and knock him down?” Fike asked, then answered his own question. “You heard the gun,” he told Jordan. “I heard the gunshot,” Jordan said.

More Questions Than Answers

By the time Jones’s trial began in 2002, the state’s theory was that Jones and Jordan had spotted the Suburban at an ice cream shop, then followed it to Howell’s parents’ home. Although Jordan never mentioned the ice cream shop to detectives, a man who was at the shop that night said he saw two Black men circling the parking lot. The driver had cornrows, like Jordan, and the other man wore a white shirt.

That man was among a slew of witnesses who took the stand against Jones at trial. But when it came time for the defense to present its case, Jones’s lead attorney, David McKenzie, called no witnesses. In an affidavit, McKenzie later said he had never tried a death penalty case before and “was terrified by this case due to my inexperience.” He admitted that he’d relied on an investigator who was “completely untrained and unqualified to be interviewing witnesses or otherwise performing investigative functions.” McKenzie also said he should have presented a key piece of evidence at trial: A photograph of Jones taken the week before the murder showed that Jones’s hair was cropped short — too short to match what Tobey, Howell’s sister, described.

Jones and his lawyers have long argued that if McKenzie had investigated Jones’s whereabouts on the night of the crime, he would have understood that Jones had an alibi. According to Jones’s family, Jones was at his parents’ home, eating spaghetti. In “The Last Defense,” his siblings recall how Jones got upset that they had eaten the rest of a leftover cookie cake from Jones’s birthday a few days before. His brother Antonio remembers that Jones was still there when their mother drove him to work. “I left, like, at 9:30 to go to work at 10 p.m.,” Antonio said. “There’s no way he could’ve skipped to Edmond and shot that guy at 9:30.”

Jones admits that he saw Jordan later that night. And he says that he did help move the Suburban, not on the night of the murder but the next day. According to Jones, King paged him looking for Jordan. When he could not reach him, King offered to pay Jones if he would help move the vehicle. Against his better judgment, Jones said, he agreed, but he refused to drive it. Regardless, Jones insists that he did not know what had happened to Howell. Later that night, Jordan spent the night in an upstairs bedroom at the home of Jones’s parents. It was there that police would find a .25 caliber gun wrapped in a red bandanna.

In “The Last Defense,” lawyers for Jones emphasized the need to test the bandanna for DNA. They believed that the results could implicate Jordan. But when the bandanna was tested in the fall of 2018, DNA instead came back pointing at Jones. There were three other male DNA profiles detected, but they were too degraded to compare to known profiles. Today, Jones’s lawyers say that the DNA raises more questions than answers.

They also argue that junk science was used to convict Jones, like discredited bullet lead analysis provided by a former FBI analyst who later admitted to giving false testimony in a different case. And they point to the absence of other key physical evidence, like the lack of fingerprints linking Jones to the Suburban.

Finally, they emphasize the racism that animated Jones’s trial. Only a single Black juror served on the panel that convicted Jones. One juror has since come forward to say that a fellow juror referred to Jones using the N-word, saying that he ought to be shot and buried under the jail. As McKenzie put it following the verdict, “In a death penalty case of a Black man accused of killing a rich white guy, I don’t think there is any possible way you could have gotten a fair trial in Oklahoma City.”

With so many lingering questions, Dill, the former Edmond police officer, can’t say for sure who really killed Howell. He is certain, however, that Jones does not belong on death row. “Let’s put it this way: He did not get a fair trial. I know that for a fact,” he said. “And if you don’t get a fair trial, then how can you be guilty? So I have to say that he’s not guilty.”

Invitation to an Execution

In the months before Jones’s clemency hearing, members of the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board repeatedly showed that they tended to agree with Dill. In March, over the protests of the state’s attorney general, board members agreed to consider Jones’s application for a commutation — a rare chance “to remedy an excessive sentence,” as defined by the board. Following a hearing in September, they recommended reducing Jones’s sentence to life in prison with the possibility of parole by a vote of 3-1. But Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt declined to make a decision at the time, explaining that he would prefer to wait for a clemency hearing, which traditionally precedes an execution date and gives both victims’ families and the condemned a chance to speak.

The board’s actions enraged Prater, the Oklahoma County district attorney, who along with state officials has taken extreme measures to block the board from considering Jones’s case. In March, he sued both the governor and his appointed board members just days after the decision to allow a hearing. He then repeatedly petitioned the state Supreme Court to disqualify two board members from voting on both Jones’s commutation and clemency applications. In October, Prater convinced an Oklahoma County judge to convene a grand jury to investigate the parole board. Although Prater has repeatedly accused board members of having conflicts of interest, the move evinced a double standard: The judge who gave the green light was the husband of one of the prosecutors who sent Jones to death row.

At the clemency hearing on November 1, Antoinette Jones watched as her brother’s lawyers prepared to speak. She wore a “Justice for Julius” face mask along with a strand of pearls given to her by her mother. In the months leading up to the hearing, she had taken leave from school to focus on fighting for her brother. Now she prayed for everyone at the hearing — for the Howells, who had to relive their loved one’s murder, and for her family, who stood to lose their own. “It was a lot of tension. It was a lot of emotion,” Antoinette said. But it was nothing compared to growing up with her brother facing execution for a crime she knew he did not commit.

Jones’s attorney, Assistant Federal Public Defender Amanda Bass, emphasized three key pieces of evidence that Jones’s jury never saw. She reiterated that the photograph showing Jones’s short hair conflicted with the claim from Howell’s sister, Tobey, that there was half an inch to an inch of hair sticking out from under the shooter’s cap. Jordan, on the other hand, had cornrows, which would more closely match what she saw.

Second, Bass said, two of the state’s main witnesses — Lottie and King — were longtime confidential informants who had cut deals with the Oklahoma County district attorney in exchange for their cooperation. In fact, just a few years before implicating Jones, Lottie had helped that same office send two innocent defendants to death row. Those men were exonerated in 2009.

Finally, the jury never heard from multiple people who said that Jordan had bragged about killing Howell and letting Jones take the blame. Two men had spoken up around the time of Jones’s trial, after spending time with Jordan at the Oklahoma County jail. Two more came forward earlier this year. “The attorney general’s office has argued that none of these individuals are credible because they have felony convictions,” Bass said. “At the same time, they ask you to credit the testimony of the prosecution’s central witnesses against Julius.”

In response, a prosecutor with the state attorney general’s office reiterated the witness accounts presented at trial. She also emphasized something Tobey told the local TV station in September: that her description of the shooter’s hat and hair had been misconstrued for years. When she said she saw a half-inch to an inch of hair, Tobey meant the hair visible between the man’s ear and cap, not the length of the hair itself.

For all the debate about the hair, a fundamental fact cuts to one of the biggest problems at the heart of the case: Eyewitness descriptions, particularly cross-racial identifications, are notoriously unreliable and a leading factor in wrongful convictions. Tobey’s account was based on what she saw in a moment of extreme panic, at night, as she frantically tried to escape the car with her nieces. Yet the state went so far as to insist that if Jordan were the real killer, Tobey would have been able to see “the outline of cornrows under the shooter’s cap.”

When it was time for the Howell family to speak, they were emotional, at times angry. Howell’s daughter, Rachel, who was only 9 years old when her father was murdered in front of her, said that she recalled waving to Jones before he shot her dad. She also read portions of a letter she said she had received from a defector from the Justice for Julius movement, who apologized for his role in misleading people about the case.

It was approaching noon when Jones spoke via video. In a maroon prison jumpsuit and glasses, he read from a prepared statement. He said he was sorry for Howell’s family. “My family and I never lost sight that they have lost a loved one.” But he maintained his innocence. “I’m here to tell you what I never got to tell the jury in my trial,” he said. “Yes, I’ve made many mistakes in my youth, but I did not kill Mr. Paul Howell.”

Around 12:30 p.m., the activists in the church parking lot gathered to listen to the vote. They bowed their heads and held hands. The board members spoke one by one. “I continue to believe that there is doubt in this case,” said Kelly Doyle, voting yes for clemency. Richard Smothermon, a former district attorney, voted no. Next came Larry Morris, who said both sides had given persuasive presentations. But to him, it was “not so much about his guilt or innocence” but the disparity between Jones’s sentence and Jordan’s. “To give one person 15 years and then execute the second one — there is something inherently wrong in that decision in my opinion.” He voted yes.

The last vote came from Chair Adam Luck. Yes. The final tally was 3-1. In the parking lot across the street, the crowd embraced and wiped tears from their faces. A woman went around giving hugs to strangers. But it was not over yet. The final decision would be up to the governor.

With the board now voting twice to spare her brother’s life, Antoinette hoped that Stitt would announce his decision swiftly. But two weeks later, she and her family are still waiting. In the meantime, a week after the clemency vote, she received a notice from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections asking her to fill out information for her attendance at her brother’s execution. “It’s so inhumane,” she said. “An invitation to an execution.”

Leigh White and Walter Adams, behavioral health specialists, respond to a 911 call about a homeless encampment in Albuquerque. They are members of the Albuquerque Community Safety department, an ambitious experiment in policing. (photo: Ann Hermes, CS Monitor)

Leigh White and Walter Adams, behavioral health specialists, respond to a 911 call about a homeless encampment in Albuquerque. They are members of the Albuquerque Community Safety department, an ambitious experiment in policing. (photo: Ann Hermes, CS Monitor)

Walter Adams and Leigh White are on patrol. Their white car, stamped with “Community Safety” decals, is headed for a neighborhood once known as the “war zone.”

Mr. Adams and Ms. White aren’t carrying guns, though. Instead, they are armed with a trunk full of water bottles, Cheez-Its, and Chewy bars. Both are wearing jeans and matching black T-shirts. Skee-Lo’s 1990s hit “I Wish” is blasting from the radio.

While Mr. Adams drives, Ms. White eats breakfast snacks and works on a black Dell laptop. Before long, the first dispatch flashes over the computer screen. They have to head west.

A few minutes later, they’re standing outside two tents pitched in the trees near a church. People walking or jogging along a nearby trail glance over.

“Someone called 911 and said there was a fire,” says Ms. White. A man inside the tent curses back at her.

“We know better than that,” he says. He’s been homeless for seven years, he tells them. “That’s what people do, call the cops,” he adds. “It’s [bull].”

“We’re not here for that,” replies Mr. Adams. “What happens is police get a call, and they send us.”

Ms. White and Mr. Adams, in fact, aren’t police. What they do is not normal emergency response work nor normal police work. It’s something of a hybrid of the two – part of an experiment that Albuquerque is hoping will change public safety in America.

They are members of the Albuquerque Community Safety (ACS) department. Launched in August, the agency is intended to complement the city’s police and fire departments by having teams of behavioral health specialists patrol and respond to low-level, nonviolent 911 calls.

While it is modeled after programs in a few other cities, ACS is the first stand-alone department of its kind in the country. The initiative is still nascent – Mr. Adams and Ms. White are one of just two responder teams at the moment. But authorities here hope it will defuse the kinds of tensions between police and residents that have surfaced in cities across the country and help reinvent 911 emergency response systems, which many believe have become antiquated.

“What Albuquerque is doing is really exciting and innovative,” says Nancy La Vigne, executive director of the Task Force on Policing at the Council on Criminal Justice, a think tank based in Washington, D.C. Police chiefs “almost universally say we’d love to offload these calls to other people. We need these types of models to be developed and implemented, so we can learn from them.”

On this stop, the program makes its small mark. Mr. Adams tells the homeless man about resources available at HopeWorks, a local nonprofit. The man says he’s been there before, but never upstairs, where many of the services are.

“As long as you show commitment, they’ll help you,” says Mr. Adams.

The man says he’ll go.

Since the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020, cities around the country have debated how to reform policing – from reducing the use of lethal force, to increasing accountability, to curtailing the need for officers to deal with complex social issues at the expense of genuine criminal investigations.

Albuquerque has been debating change, too. Yet to see why the city has become one of the first to push public safety in a new direction, you have to wind the clock back a decade.

From 2010 to 2014, members of the Albuquerque Police Department shot and killed 27 people. One of them, in March 2014, was James Boyd, a homeless man diagnosed with schizophrenia. An investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice concluded a month later that APD “too often uses deadly force in an unconstitutional manner,” including against “individuals who posed a threat only to themselves.” The police entered into a court-approved agreement with DOJ that October, which the department has been operating under ever since.

Initially, police shootings in the city decreased for several years. But more recently they have begun to rise again. From 2015 to this year, Albuquerque had the second-highest rate of fatal police shootings in the country among big cities.

While all this was going on, New Mexico’s behavioral health system was falling into disarray as well. In 2013, the state launched a criminal investigation into 15 of its largest mental health providers – accusing them of defrauding Medicaid – and froze their funding. The state attorney general cleared all the providers of the allegations, but the state’s mental health system has never fully recovered.

Since moving to Albuquerque from the East Coast 20 years ago, Ms. White has watched as the city’s police and mental health care systems have fallen in national rankings – and wondered what she could do.

“I have certainly seen it get a whole lot worse in Albuquerque over the last couple of years, especially with COVID,” she says. “I thought [ACS] would be a great way to get back involved in the community, let these folks know that there’s somebody that cares.”

In many cities, calling 911 hasn’t always been the best way to get someone help. Albuquerque’s aim with its new initiative is as much to re-imagine its emergency response system as it is to reform policing.

The 911 system is now about 60 years old. It hasn’t changed much since emergency medical services were added to calls in the mid-1970s. “We ultimately decided to couple care with enforcement,” says Rebecca Neusteter, leader of the Transform911 project at the University of Chicago Health Lab, an initiative aimed at reforming the nation’s emergency response system. And since then “this critical gateway [has] been neglected.”

About 1 in 4 people killed by police since 2015 had mental illnesses, according to a Washington Post database. Many of those killings occurred after the families of those people called the police for help.

“The default response is to send police to a scene and hope they solve whatever is happening,” says Dr. Neusteter. That’s “really not in anyone’s interests.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has put even more strain on systems in cities such as Albuquerque, in terms of both funding and demand. But the new agency has the potential to bring some changes locally.

“By and large [ACS] is a positive move” for policing in the city, says Peter Simonson, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico. “It holds the promise that perhaps someday we will see fewer armed officers interacting with people in mental health crisis.”

Ms. White and Mr. Adams are having a busy morning. They respond to five calls, most of them dealing with unsheltered individuals and homeless encampments. They all follow a familiar script. The two responders pull up in their white Honda Civic, and Mr. Adams and Ms. White grab water bottles and snacks from the trunk. They offer them to the people in the encampments, who eye them with a mixture of suspicion and curiosity. Then the behavioral health specialists ask the people if they’re connected to services, or want to be.

Ms. White, with a keen eye for detail, notices cuts or hospital bracelets and checks to see if anyone wants medical attention. Mr. Adams approaches them with a disarming ease. He ambles up and greets the individuals like he would a stranger he’s asking for directions. It’s an unruffled approach born of his past.

Mr. Adams grew up in a town, Las Vegas, New Mexico, that had widespread gang and drug problems. It also was home to the state’s main psychiatric hospital. To keep him out of trouble, Mr. Adams’ father would have his son accompany him to basketball games at the hospital.

So, starting in third grade – long before he knew about behavioral disorders – young Walter began socializing with people who were dealing with mental health issues. It is something he leans on today.

“My dad’s playing basketball and I’m just there. I was around it,” he says. “You knew those people, you knew their name, you talked to them. So to me, it wasn’t anything new or different.”

Mr. Adams came to ACS from the criminal justice system – specifically juvenile corrections and specialty courts for people with behavioral health disorders. Like many of his colleagues, he’s spent years dealing with people some might consider dangerous or threatening. And while he admits that ACS is in its infancy, he thinks they could be doing more.

“Ninety-five percent of our calls are unsheltered individuals,” says Mr. Adams. “We can respond to others. [But] I think [officials] are still getting used to it.”

ACS teams operate under some restrictions. While the responders have been integrated into the 911 system, the calls they get are screened first by the police department to determine whether they meet certain classifications – no firearms on scene, for instance – and then by fire department staff.

For now, the ACS teams are also only working 8 to 5, avoiding the possible hazards of night duty. They hope to have 24/7 service by the end of the year.

Once the responders are available round-the-clock, Mr. Adams doesn't envision many concerns. “It would be more intoxicated people, potentially more dangerous,” he says. But “I don’t think the response would be different.”

Not everyone agrees with that. Some think more serious call types could dramatically change what team members do, and, more important, what happens to them.

And those circumstances could determine how successful the program is.

Or isn’t.

In the lead-up to the launch of the ACS initiative, the new recruits had to go through considerable training before being allowed to roam Albuquerque’s streets. They met with various emergency response professionals to learn about coping with different situations.

Some of the training was technical – how to use “MDTs,” the mobile data terminals that flash calls across the screens in their cars. Other lessons were case specific: How do you transport someone who is drunk? What do you do if you take someone into custody and they have a dog?

Yet a key focus of the training was on the main concern that many people have about the ACS program here and initiatives like it around the country – safety. How do you send unarmed social workers or behavioral health responders into potentially dangerous situations without getting them killed?

“Every call you go on you should expect the potential for violence,” Lt. Jerrad Luciani of Albuquerque Fire Rescue (AFR) told the new recruits during an instruction session in August. “Keep your head on a swivel.”

“A bullet can travel faster than you,” added AFR Capt. Alejandro Marrufo. Even though calls are screened to avoid putting AFC team members into potentially dangerous situations, no one can predict when something might go wrong.

“There’s only so much the call taker can do to determine what’s happening on the ground,” says Dr. La Vigne of the Council on Criminal Justice. “Situations can also become threatening in real time as well.”

For now, there are 10 emergency call types ACS personnel will respond to, ranging from issues surrounding homelessness to suicide. Albuquerque receives about 200,000 of these calls a year. Over time, this list will expand, which is where complications could arise.

“It’s a complex problem of when to send who. But until recently we only had one option and that was police for everything,” says Matt Dietzel, acting commander of the police department’s Crisis Intervention Section.

“It makes me nervous, and I fully support ACS,” he adds. “There are tons and tons of calls for them to take. But there is probably a line” to draw somewhere on who gets sent out on what calls.

The new recruits know there will be challenges to face. Many of them come from backgrounds of managed care, where they had worked with individuals for a long period of time, and now they will be responding to spontaneous situations. But they believe their backgrounds will be an asset.

Chris Blystone moved to New Mexico from a small town in Michigan after the 2008 recession. He had hit bottom, along with the U.S. economy, and wanted to turn his life around. Raised by a single mother who had a litany of mental health issues and an abusive partner, Mr. Blystone was rebellious growing up. He got kicked out of his mother’s house and spent time on the streets, he says, stealing food and car stereos.

He got involved in the behavioral health system when he moved to New Mexico, working in a halfway house and then at HopeWorks. “It takes a hard life to deal with hard lives,” he says. “No guns and no weapons, just empathy and a soft touch. I think that can go a long ways.”

The police department does have some experience in dispatching social worker-types out into the streets. The Crisis Intervention Section contains eight detectives, two clinicians, and a psychiatrist. When police encounter unexpected behavioral issues on a call, this is the group they usually summon. The division also contains COAST, a small team of case managers that since 2005 has focused on helping mentally ill people who come into repeated contact with law enforcement. This unit will now be absorbed in the ACS program.

Mr. Dietzel, a police officer for 16 years, has watched as the department has struggled to adapt to its increasing behavioral health-related workload – and not hired the officers it needs.

“There’s never been enough officers,” he says. But, as ACS grows, “it’s going to help reduce the burden that [the police department] is facing right now.”

The ACS staff is expanding slowly, but another group of responders should be hitting the streets in November, doubling the department’s number of patrol units. Once the agency has hired its full complement of 41 field staff for the year, the goal is to take 3,000 to 4,000 calls a month. While this is a fraction of the overall 911 calls the city gets, advocates of the program believe it will have effects far beyond the emergency response system.

“You can correlate it to lives saved,” says Tim Keller, the mayor of Albuquerque and one of the driving forces behind the new initiative. He believes it will give police more time to respond to serious crimes, and “should build trust in communities,” especially ones that have been “overpoliced.”

Backers also note the program should be insulated somewhat from the vicissitudes of politics. ACS is budgeted as a stand-alone department, which means it may avoid some of the budget cutbacks that have historically bedeviled criminal justice reforms when violent crime spikes.

“We’re not quite sure if [everything] is going to work, says Mariela Ruiz-Angel, director of ACS. “But if we don’t get this going, [if we] try to overanalyze, we’ll never get anywhere.”

“Public safety has to at some point change,” she adds.

Eventually, authorities hope the program will help them tackle the root causes of systemic issues like substance abuse and chronic homelessness, as well as cut down on repeat 911 calls.

“We [want to] have enough longitudinal data to say that people who [were] calling 911 three hundred times a year are now calling [about] 12 times a year,” says Sarita Nair, the city’s chief administration officer.

The last call of the morning brings Mr. Adams and Ms. White to a gas station convenience store at a busy intersection near downtown. A homeless woman outside the store is shaking and yelling to herself.

The team worries she could stumble into the street, or accidentally hit someone walking past, so the two responders talk with her, keeping a bit more distance than normal. She eventually takes the bottle of water they offer, and sits down in the shade. Mr. Adams believes that she is on drugs or may suffer from mental illness, but she’s answering their questions and staying calm. Until she isn’t.

She starts shouting to herself. Mr. Adams calls for an ambulance. It arrives a few minutes later, followed by a fire truck. The woman was lucid and responsive, Mr. Adams says, “then she just flipped.” After a short discussion with the other responders, the woman is sedated and taken to a hospital.

It’s the kind of call that, if the wrong person responded at the wrong time, could have escalated like the James Boyd incident in 2014. Instead, everyone is leaving safe, and no police officer had to be there.

Mr. Adams walks away from it like he has the hundreds of other calls he’s taken so far in his new job. No matter what the circumstances, he approaches each incident, he says, the same way: with patience, compassion, and snacks.

“I serve those people with the same intention that I would want someone to help my family,” he says.

Still, he notes, ACS is “a work in progress.” “There’s no one that could tell us [how to evolve], because there has never been this type of program,” he says. “We’re going to grow together.”

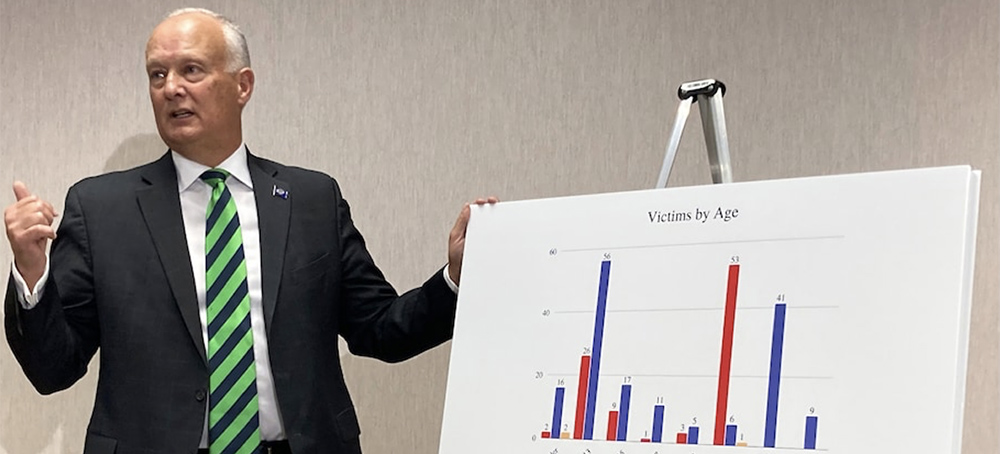

Nebraska Attorney General Doug Peterson discusses the findings of a statewide Catholic Church sex abuse investigation on Nov. 4 in Lincoln, Neb. (photo: Grant Schulte/AP)

Nebraska Attorney General Doug Peterson discusses the findings of a statewide Catholic Church sex abuse investigation on Nov. 4 in Lincoln, Neb. (photo: Grant Schulte/AP)

Yes, it’s an old story. And no, the sheer repetitiveness of what is by now a well known pattern of conduct within the church should not cauterize the outrage nor inure lawmakers to the urgency of action.

As in other states, and many countries, prosecuting clerical abusers in Nebraska for crimes committed years ago is impossible because the criminal statute of limitations has closed or the abusers themselves are dead. Most of the instances of reported abuse documented by the state attorney general’s office took place in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s and tapered off over the past 20 years. Nebraska has changed its laws to eliminate any time limit on prosecutions for future child sex assaults, but past cases remain off limits both for criminal charges and for lawsuits.

It’s an old story; it’s also a current one. Sexual abuse is notoriously under-reported, especially when the victims are children unaware, or not fully cognizant, that what they have experienced is a crime. Typically, the victims, whose abusers are often authority figures, say nothing for years. Today’s youthful victims, in the Catholic Church or any other setting, might not come forward for a decade or two.

In Nebraska, the hair-raising details of Attorney General Doug Peterson’s report reflect the depth of the church’s arrogance and impunity. It’s noteworthy that one of the state’s three dioceses, based in Lincoln, for years refused to participate in the church’s own annual reviews of sexual misconduct. Incredibly, the church tolerated it. It was in Lincoln that church higher-ups knew about multiple allegations of sexual abuse for at least 15 years against James Benton, a priest who continued on in ministry until his retirement in 2017. Some of the allegations against him dated from the early 1980s.

The number of victims of clerical abuse who have come forward to report abuse exploded after a major investigation by the Pennsylvania attorney general’s office, which published a report on it in 2018. The next year, allegations of past abuse quadrupled, to more than 4,400, and stayed roughly in that range in 2020, according to the latest annual report on the subject by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Despite those reports, and that scrutiny, just about 10 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that allow victims to file lawsuits for past abuse, by briefly suspending the statute of limitations in “lookback windows.” Amazingly, Pennsylvania, where the grand jury documented roughly 300 priests accused of abusing more than 1,000 children, is not one of those states.

It is true that the U.S. Catholic Church has been more proactive than its counterparts in almost every other country in identifying clerical sex abusers and cooperating with investigative authorities. Yet the U.S. bishops have also continued spending tens of millions of dollars annually lobbying state lawmakers to prevent changes in law that would allow lawsuits for past clerical sex crimes — and enable a measure of justice and healing for victims. That is morally indefensible.

Polish military police stay on guard at the Poland/Belarus border near Kuznica, Poland. (photo: Irek Dorozanski/DWOT/Reuters)

Polish military police stay on guard at the Poland/Belarus border near Kuznica, Poland. (photo: Irek Dorozanski/DWOT/Reuters)

Stranded refugees and migrants say they are in dire need of help as row between European Union and Belarus escalates.

This weekend, the body of a young Syrian man was found in the woods near the Polish border village of Wolka Terechowska. The cause of death was not immediately known, according to Polish officials.

The restricted zone near the border is a forbidden space for reporters and aid workers, with no one except local residents allowed to enter. Reports say that some residents have started putting green lights outside their houses to show they are willing to help people in distress facing freezing conditions and a lack of vital supplies, including medical care.

What happens inside the restricted zone is impossible to fully verify because soldiers and police turn journalists away at every checkpoint. Outside, blankets abandoned on the edge of thick woodlands are often the only reminder that some people have made it through the heavily fortified border.

There is a sense of weariness on the ground from activists who have been calling attention for months to a crisis that people are only just waking up to. Now, thousands of people are camped at the Belarusian border as Poland, a European Union member, has denied them entry amid a standoff with its neighbour.

Mere kilometres from the roadblocks, Kochar*, a 26-year-old Iraqi-Kurdish man, is one of those trapped on the other side of the fence. He sends a WhatsApp location which pins his spot just opposite the Polish Kuznica border crossing point.

Kochar, who feared persecution in Iraq after having worked for a Kurdish political party in Iran, said he read on social media he could take a flight to Belarus’s capital, Minsk, and get to Europe that way.

“You know Iran can do anything in Iraq, maybe one day they will catch me,” he said. There are two options now in his mind: “Die here or die in my country; a lot of us have the same situation.”

A graduate of mathematics from the University of Sulaymaniyah in Iraq, Kochar was hoping that he might have better prospects in the EU, but knows now he has taken a dangerous journey to find a better life. “Sometimes you will do anything to escape death,” he said, even as he realises that he has been caught up in a geopolitical tug of war between the EU and Belarus.

“It’s not humanity [what] Europe and Belarus do with us,” he said. “I know Belarus is using us, but what shall we do?”

Terms such as “hybrid warfare” and “weaponisation” have been used to describe the escalating situation of desperate people lured by Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko to the EU’s borders – but Kochar finds these terms difficult to digest.

“We don’t like it,” he said, rejecting being described as a “weapon”. “We are here for life, not for fighting,” he said, pointing out the number of young children around him in the makeshift camp.

The situation on his side of the border is desperate. He sends photos of young children with messages for help scrawled on their faces.

There is not enough wood to make fires, there is not enough food for people, and many are sick because of the cold temperatures, he said. “We just want this bad thing to finish,” Kochar added. “It’s a bad thing, [to] use people and forget humanity.”

“I want Europe and all of the world to know that we are in danger. We will die here soon. We will freeze,” he said. “Belarus and Poland use us like a war. We want a good life. We are humans. I don’t want to die here, I have a lot of ambitions, I think Europe is full of humanity, but I don’t see anything until now. Please, please help us.”

‘Deeply dehumanising’ narratives

Maurice Stierl, from activist network Alarm Phone, said European countries have not found any other way to deal with the issue of migration “than to see it as a gigantic political problem, which it, of course, is not. Europe has the means to accommodate a couple of thousand people from the Belarusian forests.”

Stierl went on to describe Belarus’s actions as “obviously shocking”, but added that “when we hear about ‘instrumentalisation’ and migrants as ‘weapons’ it always underplays the fact that these people are not simply some sort of pawns moved around on a chessboard by Lukashenko and other authoritarian leaders – they are individuals who have many reasons for wanting to move”.

Stierl said it was crucial to emphasise the agency of people on the move. “Otherwise, we are always stuck in this binary where they can be understood only as military threats or as absolute victims – and, in many ways, both narratives are deeply dehumanising.”

Meanwhile, those caught up in the turmoil on the ground continue to find themselves in dire straits. Early on Sunday morning, Kochar messaged to say that he had fallen ill.

“The Belarusian soldiers told us we should cut the border today; if we don’t do [it] they push and hit us, everyone is so upset about it,” he said.