Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

I see the thousands of young protesters in the streets of Glasgow bearing signs such as “I Have To Clean Up My Mess, Why Don’t You Clean Up Yours?” and “The Dinosaurs Thought They Had Time Too” and “Stop Climate Crime” and “If Not Now, When?” at the UN Climate Change Conference, where the United States and China have issued vague promises of eliminating carbon someday but without a timetable. So much for American leadership; I guess we’re waiting for Iceland or Ecuador to show the way.

The young people in the streets are aware that a time of suffering lies ahead. Science is pretty clear about the ecological impact of industrial agriculture and the rapacious destruction of forests and overfishing of the seas and the virtual disappearance of many insect species, but none of this has enough political impact to turn the ship of state. Statistics don’t move people, recognizable images do, such as the plight of a polar bear on an ice floe miles from land. We’re fond of polar bears in zoos, and if we could get a video of this bear drowning in glacial melt, it would move people. Or if Yellowstone blew up and ushered in a year of darkness. That could be the Pearl Harbor that moves our country to action.

Greta Thunberg, the 18-year-old Swedish activist who, in 2018 after Sweden’s fierce hot summer of wildfires and omens of disaster, sat outside the Swedish parliament every day to get her message across. Her message was simple: “Our house is on fire.” Five words, not one wasted, and you could paint it on any wall and everyone would know what you mean.

Children have great power to shame the rest of us, as every parent knows, and this cause is worth their effort. It’s about the survival of our kind. Everything we love is in the balance, language, art, music, history, the art of story, dance, Eros, baseball, bird-watching, and the effect of apocalypse on the bond market would not be good.

The last Good War was won by boys who rushed to sign up, after seeing newsreels of sunken battleships in Hawaii. My hero Bob Altman was 16 and lied about his age to get into the Army Air Force and pilot a B-17 bomber in the Pacific. The children marching in Glasgow are capable of heroism, but they’ve put their faith in the conscience of politicians, not a good bet. One of the two major American political parties is in denial that global warming exists because it is devoted to an illiterate leader. That party appears likely to take over Congress in 2022 and two years later No. 45 may well become No. 47. If he does, we may have a constitutional convention at which the presidency is made a lifetime term. Meanwhile, we have a Supreme Court with a solid majority of Ayn Rand justices who deny that the state has the right to govern individual behavior. Gun control will be dead, conservation will be an individual responsibility.

I don’t see that bunch leading the country toward clean energy. So we’ll go on enduring wildfires and horrific hurricanes and drought and the melting of the arctic ice cap and nothing will change. We’re living in a tunnel and a train is approaching. Mr. Bezos and Mr. Musk can move to the moon but the rest of us are earthlings.

I put my faith in scientific enterprise. Someone will come up with a way to turn plankton into something that looks like and tastes like ground beef. Someone else will figure out how to make linguine from dead leaves. Then there’ll be nuclear airliners.

People don’t like to be lectured and made to feel stupid, Mr. Science. Get busy and invent a car that runs on urine. So much gas is wasted by people driving around looking for a lavatory. This will come as a great relief.

Former Trump Chief of Staff Mark Meadows failed to appear before a capitol riot committee. (photo: Patrick Semansky/AP)

Former Trump Chief of Staff Mark Meadows failed to appear before a capitol riot committee. (photo: Patrick Semansky/AP)

ALSO SEE: Trump Defended Rioters Who Threatened to 'Hang Mike Pence,' Audio Reveals

The former Trump adviser would be the second ex-white house official to face a criminal referral for contempt of congress

The ex-White House aide had received a subpoena from Mississippi Rep Bennie Thompson, the chairman of the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the Capitol on 23 September, ordering him to deliver documents and appear to give evidence before the committee, which is investigating the role White House officials played in efforts to block Congress from certifying Joe Biden’s electoral college victory, by 7 October.

Mr Meadows, who represented North Carolina’s 11th congressional district from January 2013 until he resigned to serve as former president Donald Trump’s top aide in March 2020, had his deadline for compliance with the subpoena extended while he and his attorney, George Terwilliger, were in negotiations with the committee over the terms of his compliance.

But Mr Thompson appears to have lost patience with his former colleague. In a Thursday letter to Mr Meadows’s attorney, the chairman ordered him to appear for a 10.00 am deposition on 12 November.

“Simply put, there is no valid legal basis for Mr. Meadows’s continued resistance to the Select Committee’s subpoena. As such, the Select Committee expects Mr. Meadows to produce all responsive documents and appear for deposition testimony tomorrow, November 12, 2021, at 10:00 a.m. If there are specific questions during that deposition that you believe raise legitimate privilege issues, Mr. Meadows should state them at that time on the record for the Select Committee’s consideration and possible judicial review,” Mr Thompson wrote.

“The Select Committee will view Mr. Meadows’s failure to appear at the deposition, and to produce responsive documents or a privilege log indicating the specific basis for withholding any documents you believe are protected by privilege, as willful non-compliance. Such willful non- compliance with the subpoena would force the Select Committee to consider invoking the contempt of Congress procedures…which could result in a referral from the House of Representatives to the Department of Justice for criminal charges—as well as the possibility of having a civil action to enforce the subpoena brought against Mr. Meadows in his personal capacity”.

If the House votes to hold Mr Meadows in contempt, he would be the second ex-Trump White House official to be referred to the Justice Department for such charges. Former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon, who has also defied a subpoena on Mr Trump’s orders, was referred to the Justice Department after a House vote last month.

The former congressman claims that he cannot obey a valid subpoena from the body in which he once served because Mr Trump, who is now a private citizen, has directed him not to comply on the grounds that his testimony and the documents requested by the committee are shielded by executive privilege, a legal doctrine which protects deliberations between and among a president and his advisers.

In addition, his attorney said in a letter to Mr Thompson that Mr Meadows is “immune” from having to give evidence based on legal opinions from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel.

“Mr Meadows remains under the instructions of former President Trump to respect long-standing principles of executive privilege. It now appears the courts will have to resolve this conflict,” Mr Terwilliger wrote.

In his response, Mr Thompson noted that “every federal court” that has taken up the issue of whether presidential advisers enjoy “absolute immunity” from testimony have rejected such arguments.

Most reputable legal scholars say Mr Trump, whose term as president ended on 20 January, has no legal authority to block Mr Meadows from complying with a congressional subpoena because under Supreme Court precedent it is the incumbent president — Joe Biden — who determines whether to claim the privilege.

So far, Mr Biden has declined to do so, citing the need to fully investigate the circumstances which led to the worst attack on the Capitol since the 1814 Burning of Washington.

Mr Trump is currently pursuing litigation in federal court to block the National Archives and Records Administration from turning over White House records created before and during the 6 January insurrection. A federal district judge has already rejected his arguments, but he has filed an appeal before the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which will hear arguments in the case on 30 November.

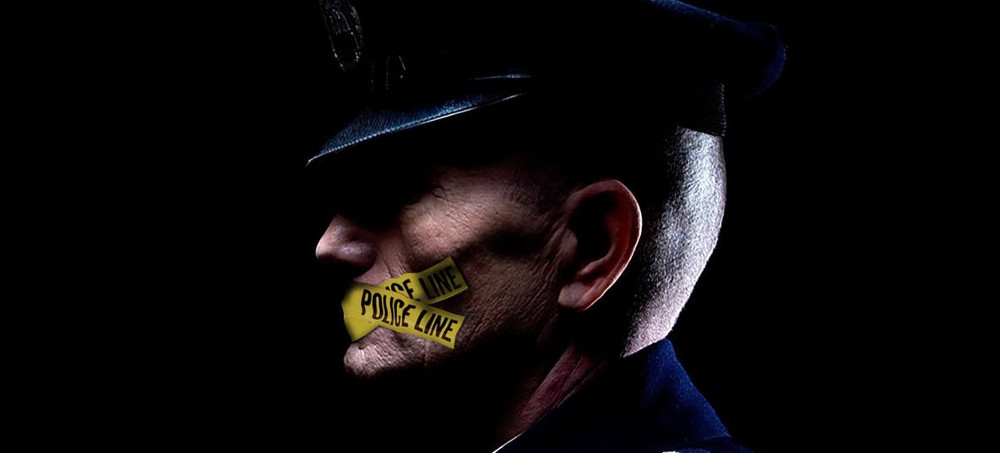

A new investigation finds that police often face retaliation for reporting misconduct. (photo: USA TODAY)

A new investigation finds that police often face retaliation for reporting misconduct. (photo: USA TODAY)

He wrote that his distinguished career "was all tarnished ... after I reported (an) officer lying on the stand and going to the FBI."

He was responding to an investigative story we published this week, Behind the Blue Wall, that documented how often police whistleblowers face retaliation for reporting misconduct. They have been threatened, fired, jailed, one was even forcibly admitted to a psychiatric ward.

"I want to personally thank you for bringing this to light," the officer wrote. "You were able to write what I have experienced for the last 6 years. After reading this I took a deep breath and for the first time since this began I feel liberated from the stigma of being a rat, untruthful, discredited."

Police covering for colleagues, and punishing those who don't, isn't new. But with this investigation, we wanted to quantify, for the first time, the extent of the problem and how it impacts the whistleblowers. And, we wanted to find out how officers silence their own.

What we discovered: "In building a catalog of more than 300 examples from the past decade, reporters found there is no wrongdoing so egregious or clear cut that a whistleblower can feel safe in bringing it to light."

How did we get these documents?

We tried going to police agencies themselves asking for records on whistleblower complaints. In many cases, no luck. They cited privacy issues and ongoing investigations or just ignored the requests. So, investigative reporter Brett Murphy explains, reporters went for side doors. They asked whistleblowers where else they reported misconduct.

Whistleblowers are "turning to their local human resources division for the city governments, state labor boards, the feds, EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission), the NLRB (National Labor Relations Board), the attorneys general, state police, anywhere that they thought they could get out from their own department because they were kind of terrified of what was gonna happen to them internally."

So we went to the same places and requested records that included words such as "police" or "sheriff" and "retaliation." Many fought the requests, and we fought back for the public's right to know. We sent reporters to seven states to interview police officers, victims of misconduct and grieving families.

Reporters sent out 400 public records requests and secured tens of thousands of pages of records. They found 300 cases in the past decade where an officer helped expose misconduct – a small window into how the system works. The vast majority of those cases ended with those whistleblowers saying they faced retaliation.

"It doesn't matter how bad the stuff is they expose," Murphy said. "Fellow deputies beating a prisoner who later died; a captain who impregnated a 16-year-old girl and then paid for an abortion; a co-worker bragging about killing an unarmed teenager.

"In each of those, the officers who spoke out were forced out of their departments and branded traitors by fellow officers."

Meanwhile, the team reported, "the officers who lied or stayed silent in support of an accused colleague later secured promotions, overtime and admiration from their peers."

Another finding that sticks with Murphy: How the systems that police created to hold themselves accountable, such as internal affairs, often have been weaponized to hunt down and punish whistleblowers.

“Whistleblowing is a life sentence,” former Chicago undercover narcotics officer Shannon Spalding told our team. She faced death threats and resigned after she exposed corruption that led to dozens of overturned convictions. “I’m an officer without a department. I lost my house. I lost my marriage. It affects you in ways you would never imagine.”

That was striking to investigative reporter Gina Barton, the toll this takes on the whistleblowers.

"I talked to several guys who said they were surveilled – mysterious cars would drive past their house while their wife and kids were outside. Very frightening and intimidating actions," she said. "The police were victims of their own profession and their own agency. These are people who you're supposed to lay your life on the line for, and you're supposed to trust them to have your back no matter what, and then they do these terrible things."

To be sure, not every officer who comes forward faces retaliation. We found cases where departments rewarded whistleblowers.

"In Del City, Oklahoma, a detective who testified against a fellow officer for shooting an unarmed man rose up the ranks to major. In Perth Amboy, New Jersey, an officer who testified against the chief ended up replacing him. There are undoubtedly other departments with similar stories that did not make it into the public record," our story said.

"But for every example of retaliation USA TODAY found, countless others likely remain concealed. That’s because the system works. Officers have seen or heard of other careers destroyed over speaking up."

One Twitter response we got to the story suggested police are no different than any other group in covering for their own: "An institution circles the wagons." Investigative reporter Daphne Duret explains the massive difference.

"These kinds of retaliations could happen in another profession," she said. "But in law enforcement, when this kind of stuff happens, people die. When (police) encounter people, a police officer can be judge, jury and executioner." And when whistleblowers face retaliation, "it does have a chilling effect" on other officers who might come forward.

That's how this story started. Investigative editor Matt Doig was reading online chats about the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. One police officer, Derek Chauvin, kneeled on Floyd's neck for more than nine minutes while he cried for help. Three other officers didn't stop him. Commenters were wondering why.

"One person who said he was a cop said, 'You guys don't understand law enforcement, it's your whole life, not just your professional life, but your personal life,'" Doig remembers. " 'If you speak out against a brother, your career is over, but your life is over, too. We all go to the same barbecues together. My wife will leave me because all her friends were the wives of cops.' "

That got him thinking, how many whistleblowers had faced retaliation? Could we quantify the number, find out how pervasive the problem is?

That's exactly what the team did.

Already, we're hearing talk of creating an independent inspector general to give whistleblowers a safe place to report. We're hearing that agencies are discussing their internal practices, now that the attention is on them.

That's the purpose of investigative journalism. Shine a light. Right a wrong. Hold the powerful accountable.

We're also heartened by officers reaching out with personal stories – and gratitude.

The Massachusetts officer ended his letter with this:

"I can not thank you enough. Beers are on me!"

Gerrymandering allows Republicans to virtually guarantee their re-election. (photo: Getty)

Gerrymandering allows Republicans to virtually guarantee their re-election. (photo: Getty)

Scroll down our visual guide to see how gerrymandering allows Republicans to virtually guarantee their re-election

Yet the reality in 2021 is much more depressing. As politicians undertake the once-a-decade process of redrawing political districts across the country, they are essentially rigging the system by deciding among themselves exactly which voters in which areas they want to represent. It’s a process called gerrymandering that allows them to virtually choose their voters and guarantee their re-election.

The United States stands almost alone in allowing partisan politicians to draw political districts in this way. It’s an invisible scalpel that profoundly affects US politics but also the tenor and character of the national discourse.

Republicans have control of the process in many states this year. And so far, they’re maximizing their advantage wherever they can. The new lines will likely help Republicans retake control of the US House next year.

Let us show you how the Republicans are gerrymandering in four important parts of the country.

Dismantling a Democratic district

In North Carolina, Republicans have drawn a new congressional map that gives them a lock on at least 10 of the state’s 14 congressional seats. That’s a staggering advantage in a state that re-elected a Democratic governor in 2020 and where Joe Biden got 48.6% of the statewide vote.

Remarkably enough, federal courts can’t do anything to stop this kind of extreme gerrymandering on partisan grounds, the supreme court ruled in 2019.

There are few limits on the process. Each district must have roughly the same number of people. In many places they must be reasonably compact. And lawmakers can’t dilute the influence of voters based on their race.

But politicians are free to group voters based on their partisan leanings. And in recent decades, they’ve done that surgically, carving up communities to essentially lock in advantages for years to come. A decade ago, Republicans launched a hugely successful effort, called Project REDMAP, to take control of state legislatures and then used their new majorities to draw maps that locked in their advantage for a decade. This year, Republicans have the power to draw the lines of 187 congressional districts while Democrats have power in 75, according to the Cook Political Report.

During the 2012, 2014 and 2016 midterm elections, gerrymandering shifted 59 congressional seats, 39 for Republicans and 20 for Democrats, according to a report from the left-leaning Center for American Progress.

While Democrats have gerrymandering power in far fewer places this year, they’ve also shown a willingness to use their scalpel where they have control in places such as Illinois and Oregon.

Diluting the influence of Black voters

Although it is illegal to carve up districts that weaken the influence of voters based on their race, sometimes lawmakers do it anyway.

Weakening diverse, Democratic-leaning suburbs

In Texas, Republicans have drawn lines that blunt the immense growth among the Democratic-leaning Hispanic population to shore up the GOP’s hold on as many as 25 of the state’s 38 congressional seats.

Even though people of color accounted for 95% of the population growth over the last decade, there are no districts where minorities make up a majority of the population.

Until 2013, states with a history of voting discrimination, including Texas, had to get their maps pre-cleared by the federal government before they went into effect to ensure they didn’t discriminate against minority voters. Now, Texas has much more leeway to pass maps that discriminate against people of color.

Packing Democrats into non-competitive districts

The Dallas-Fort Worth area in Texas is one of the fastest growing areas in the state – and one of the most politically competitive. Because each district must have roughly the same number of people by law, Texas Republicans had to get creative in how they regrouped voters.

In some places, they took small slivers of heavily populated Democratic suburbs and attached them to rural GOP areas. In other cases, they excised Democrats from politically competitive districts and packed them into districts that already favored Democrats.

Voting rights advocates face an uphill battle in challenging these maps in court. In 2019, the US supreme court said there was nothing federal courts could do to stop partisan gerrymandering.

Redistricting litigation often takes years to move its way through the court, allowing lawmakers to get at least one election, and often many more, conducted under district lines that may later get struck down.

In the meantime, the effects are insidious. When politicians know their seat is safe, they no longer have to worry about competition from the opposing party or concern themselves with reaching out to the other party’s voters.

Instead, they become more interested in appealing to their own base and fending off challengers from within their own party. It makes politics more extreme, and contributes to extreme polarization.

President Biden is nominating Califf to again lead the FDA. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

President Biden is nominating Califf to again lead the FDA. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Califf, 70, led the agency in 2016-2017, in the last year of the Obama administration. In a statement, the White House called Califf "an internationally recognized expert in clinical trial research, health disparities, healthcare quality, and cardiovascular medicine."

The agency has been without a permanent leader, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, since Biden took office in January. Biden praised the acting commissioner, Dr. Janet Woodcock, for "an incredible job leading the agency during what has been a busy and challenging time."

The White House noted that Califf won Senate confirmation the last time, 89-4, with "broad bipartisan support."

Califf has in the past been a consultant to the pharmaceutical industry. He is currently a professor at the Duke University School of Medicine and is head of clinical policy at Verily Life Sciences, which conducts life sciences research.

At least one Democrat, Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, says he will oppose Califf, as he did in 2016, citing the opioid crisis in his state. Manchin said Califf's "significant ties to the pharmaceutical industry take us backwards not forward," and called the nomination "an insult to the many families and individuals who have had their lives changed forever as a result of addiction."

Jacinto Romero Flores was assassinated in August, one of eight journalists murdered in Mexico this year. His talk show was transmitted through Facebook. (photo: Victoria Razo/cuartooscuro.Com)

Jacinto Romero Flores was assassinated in August, one of eight journalists murdered in Mexico this year. His talk show was transmitted through Facebook. (photo: Victoria Razo/cuartooscuro.Com)

Half of the eight journalists murdered in Mexico this year posted on Facebook hours before they were killed. Nearly all of them relied on the platform to publicize their stories.

As he came home from the party three hours later, López was shot dead by a single bullet to the head. His killer was waiting for him as he pulled up to his house in San Cristóbal de las Casas, in the southern Mexico state of Chiapas. López was lifting a box of avocados out of the trunk of his car when a man emerged from the shadows and pulled the trigger. The father of six died on the spot.

He was the eighth journalist murdered in Mexico this year, the highest number in the world, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, an international advocacy group. The ninth, a reporter for conservative outlet Breitbart, died in mysterious drowning circumstances in October during a reporting trip about a militia group in southern Mexico.

The recent deaths have a pattern: At least four posted on Facebook in the immediate hours before their murders with personal updates or live news feeds showing their location. All but one worked on their own or for small news outlets that relied almost entirely on Facebook to disseminate their stories. Roughly 60 percent of all Mexicans use the platform, offering journalists tremendous reach they might not have otherwise, especially in small communities where internet access is scarce.

But depending on the social media platform also makes these journalists particularly vulnerable to threats, because their personal lives are exposed in ways that make it easy to threaten and track them down. Of the eight Mexican journalists killed this year, seven worked for hyper-local news outlets that lacked independent websites and published or broadcast on Facebook. In small communities, they were just as influential, if not more, than journalists from big outlets.

“A lot of these journalists who are falling victim to violence have been active on social media, and particularly Facebook,” said Jan-Albert Hootsen, the Mexico representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists. “Many of them want to report on crime and violence. They want to do their own investigations. They want to reach an audience using their own particular kind of journalism.”

But, he added, “These platforms they have on Facebook also allow their attackers to find them relatively easily.”

One journalist whose publication had an independent website was murdered in July, a few months after accusing local police of using a Facebook page to falsely accuse him of having ties to organized crime. Another journalist now in hiding after gunmen attacked his newsroom said he receives constant death threats, “principally through Facebook.” A third who covered crime was assassinated last year at a restaurant shortly after doing a Facebook Live where he denounced alleged ties between the local mayor and criminal groups. This week, on Wednesday at dawn, gunmen fired on the house of a journalist in the central Mexican state of Hidalgo, one day after she posted on Facebook that she had received threats for her reporting.

In a statement to VICE World News, Meta, the parent company of Facebook, said it invested in supporting journalists. It didn’t respond to questions about whether it was aware reporters were receiving death threats through its platform.

“We condemn any acts of violence against journalists and stand ready to work with law enforcement on their investigations into these horrific crimes,” a Meta spokesman said. “We know that many journalists use Facebook to publish stories and raise awareness about what’s happening in their communities. To support their work and help them stay safe, we have several programs, policies, and tools in place, including security features against harassment and potential threats.”

It cited, among other things, a feature that allows journalists to obtain stronger security features that protect their information and account against harassment and hacking threats.

López spent his last day busy on Facebook, posting to his personal account. He also had a one-man news site, Jovel T.V. and Radio, which was hosted on the platform.

Over the course of a few hours, he published a video of an armed self-defense group threatening local leaders, as well as short articles about the latest migrant caravan and city politics. López’s informal writing style mixed personal musings with government statistics and updates about local political appointments.

López’s eldest son, Oscar Takeshi López Moreno, said his father had received threats in the past for his journalism work, but nothing in recent years. But he is sure the assasination had to do with López’s reporting. “Every day he was publishing news, questioning the government,” he said.

The Committee to Protect Journalists said there’s a strong chance López was targeted for his reporting, but it hasn’t ruled out other possibilities. Several of the murdered journalists had jobs on the side, including López, who rented cabins by the beach. The group said it has confirmed that at least three of the journalists were targeted because of their reporting. It’s calling for investigations into the rest.

At least two of the murdered journalists had unsuccessfully run for mayor before returning to journalism, an example of how many reporters in Mexico are involved in other professions and activities that makes it hard to discern the motives behind the killings. They also raise the perennial question of who qualifies as a journalist.

“In the sense of professional journalists who are salaried, most are not that. But still they are private citizens practicing journalism. In that sense, they are exercising freedom of speech and deserve protection,” said Andrew Paxman, a historian at CIDE, a university in Mexico City, who is writing a recent history of the Mexican press.

“They are trying to hold local government to account, and they get bullied for it, and sometimes they get killed for it,” he said.

Julio César Zubillaga, editor of El Diario de la Tarde, a newspaper in Iguala in the southern state of Guerrero, went into hiding in July with the help of federal authorities after local police entered his home in the middle of the night claiming they were looking for a criminal. A year earlier, men with high-power rifles shot up the paper’s offices.

Even now, four months after fleeing Iguala, Zubillaga said he receives constant death threats, to both his personal Facebook account and the paper’s Facebook page. And it’s not just threatening messages. Fake news pages have popped up on Facebook claiming Zubillaga has ties to an armed militia group, along with photos of Zubillaga and his family members. The journalist said he believes criminal groups are behind the fake news pages.

“It 's like a window: It opens a door for everyone to participate,” Zubillaga said. “There’s no care taken, no caution.”

Harlo Holmes, chief information security officer and director of digital security at Freedom of the Press Foundation, said reporters should take commonsense steps to protect themselves.

“Even if you are not explicitly saying, ‘Here I am at this particular location,’ there might be visible cues in the background that would tip anyone off as to where you are,” Holmes said. “Chances are, anyone who is surveilling you also knows the terrain as well as you do.”

But journalists in Mexico depend on Facebook too much to simply leave it.

Hundreds of small outlets have turned to the platform for survival as the world of paper newspapers has died out and government funding for media has trickled off, said Paula Saucedo, protection and defense program officer at Article 19, a nonprofit dedicated to the protection of journalists.

“There are very small outlets, and they base all their communication through Facebook,” Saucedo said.

“Every year we witness more attacks on social media,” she added. “The vast majority of the male editors that were attacked this year have their media on Facebook.” Attacks could be both verbal and physical.

Saucedo attributed the violence against journalists to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s frequent broadsides against the press, which she said have fueled an even more hostile environment for the media, as well as widespread impunity for the politicians and crime bosses who order the journalists’ murders.

In a rare feat of justice, the killer of Javier Valdez, one of Mexico’s most well-known and respected reporters on organized crime, was sentenced in June to 32 years in prison. And a local mayor in the state of Chihuahua in northern Mexico was sentenced to eight years in prison for his role in the murder of Miroslava Breach, an acclaimed investigative journalist. Both were high-profile cases that garnered international attention.

“We have a really hard path when it comes to impunity. That’s a fact. We cannot close our eyes to the fact that during many years, no crimes were prosecuted effectively. We are trying to do our best to change that,” said Ricardo Sánchez, head of Mexico’s Special Prosecutor's Office for Attention to Crimes committed against Freedom of Expression.

Still, he said, his office doesn’t investigate if local authorities don’t come up with evidence linking the crime to the reporter’s work. That’s a problem in a country where more than 95 percent of crimes go unpunished.

Criminal groups are still warning journalists to censor what they write, or face the consequences. A member of the Viagras gang, which operates in the western state of Michoacán, recently told journalists passing through to “be careful about what you publish,” The Associated Press reported.

A leader of the group warned the journalists: “I can monitor you on Facebook, and I’ll find you.”

Climate activists protest at the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference on November 8, 2021, in Glasgow, Scotland. (photo: Alastair Grant/AP)

Climate activists protest at the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference on November 8, 2021, in Glasgow, Scotland. (photo: Alastair Grant/AP)

More money is on the table at the Glasgow climate conference, but it’s not enough.

Rising sea levels, hotter heat waves, and more frequent torrential downpours disproportionately hammer low-lying coastal areas, islands, tropics, and deserts that are home to people who historically haven’t burned that much coal, oil, or natural gas. The slow and acute impacts of climate change are already destroying homes, forcing migrations, and taking lives, particularly in countries that have few resources to begin with. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the most vulnerable countries to climate change include Haiti, Myanmar, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and the Bahamas.

Meanwhile, major producers and consumers of fossil energy, like the United States, have become the wealthiest countries in the world. That wealth also means more government and private resources to respond to a warming world, whether by building infrastructure to withstand higher tides, managing forests to reduce severe wildfires, or compensating citizens for their flood-ruined homes.

That inequity is the undercurrent of the United Nations’ ongoing COP26 climate negotiations in Glasgow, Scotland. The meeting is an opportunity for major polluters and those suffering from the effects to sit across from one another — and the countries bearing the brunt of global warming say that addressing this central injustice must be at the core of any climate agreement. Otherwise, hopes of reaching concordance on other key climate issues could fall apart.

“The largest share of the historical emissions originated in developed countries,” Diego Pacheco Balanza, head of the Bolivian delegation to COP26, told reporters Thursday. “So there is a historical responsibility of developed countries and [industrialized] countries to deal with the climate crisis.”

The most concrete way to fulfill this responsibility is to pay for it. And some wealthy countries at COP26 have said they will — to an extent, at least, and in principle.

“The countries most responsible for historic[al] and present-day emissions are not yet doing their fair share of the work,” British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said at the start of the summit.

The actions so far, however, are still lacking. “There were a lot of very positive statements,” said Janine Felson, deputy head of the Belize delegation and an adviser to the Alliance of Small Island States, a negotiating bloc of 39 island and low-lying countries. “What we are seeing, though, in the [negotiating] room is very different. It’s more business as usual, so rhetoric and deed are far apart.”

At COP26, several governments — including the US and the UK — have announced additional funding to aid low-income countries in transitioning toward clean energy, as well as more cash to help them cope with the unavoidable losses from climate change.

But the amount of money on the table still doesn’t meet past commitments, and it’s not enough to cover the enormous changes that are needed, negotiators from developing countries say.

Without settling the money issue, COP26 negotiations on other matters — trading carbon credits, phasing out fossil fuels, timelines for reducing greenhouse gas emissions — could stall or fall apart. “Climate finance is the glue that brings a package together at the end of a COP,” Richie Merzian, director of the climate and energy program at the Australia Institute, told reporters Thursday.

With the talks heading into their final day, the pressure is on wealthy governments to contribute more money toward global efforts to lower emissions. “My message to donor countries is very, very clear: Without adequate finance, the task ahead is nigh impossible,” said Alok Sharma, president of COP26.

Rich countries still aren’t meeting their commitments on climate finance

At the 2009 COP15 meeting in Copenhagen, wealthy countries set a target of pooling $100 billion by 2020 to help less wealthy countries adapt to changes in the climate already underway as well as to curb greenhouse gas emissions. The money, from public institutions like governments rather than private banks, would be deployed as a mix of loans, investments, and grants across initiatives from decarbonizing power generation to building seawalls.

The target was missed. The last tally shows that $79.6 billion in international climate financing was awarded in 2019. Now the goal post is 2023 for the $100 billion goal, given the current pace of commitments.

Negotiators in developing countries have been pushing to close that gap even faster and want the final agreement from the COP26 meeting to highlight their “serious concern” that the amount of financing available is not enough to cope with what’s needed to cope with climate change. They also want the text to emphasize that wealthy countries are required to contribute more money to climate financing programs.

“Finance is not the charity of developed countries to the developing world,” Pacheco Balanza said. “Finance is an obligation.”

At the same time, there are immense financial to mitigating climate change. One estimate found that shifting the global economy toward sustainable energy would save the world $26 trillion by 2030. But the costs of mitigating climate change and the benefits often accrue to different people, and it’s proven difficult to leverage that in negotiations.

Now, some developing countries now say they need vastly more money to meet their goals. India, the world’s third-largest greenhouse gas emitter, committed at COP26 to reaching net-zero emissions by 2070. But it says it wants $1 trillion in international climate financing by 2030 to meet its goal. African governments have said that climate finance funding should reach $1.3 trillion per year by 2030.

It’s likely that the $100 billion funding target will be solidified at COP26 with the momentum underway. However, it’s unlikely these far greater demands will be considered, given that parties to the Paris agreement failed to meet a much smaller objective on time.

Who will pay for climate devastation in the most vulnerable and poorest places?

Many of the talks at COP26 focus on climate change mitigation — what countries will do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, what their targets should be, when they should reach them, and what tactics count toward their goals.

But the world has already warmed up by 1.1 degrees Celsius compared to global average temperatures before the industrial revolution, and that warming is already having effects. Global sea levels, for instance, have already risen 8 to 9 inches, leading to more devastating storm surges.

Dealing with the changes in climate already underway is a high priority for countries like island nations seeing their land swallowed up by rising seas and seeing disasters amplified with more rainfall and higher heat.

In COP-speak, this is known as loss and damage. There is a mechanism for dealing with this under the 2015 Paris climate agreement, building on an earlier framework known as the Warsaw International Mechanism. One estimate found that loss and damage from climate change would cost the world between $290 and $580 billion a year by 2030. And losses can go beyond those that are easily priced, like cultural heritage and ecosystems degraded by rising average temperatures.

The trouble is, there isn’t a set goal for how much money should be allocated to loss and damage, who is required to chip in and by when, and how that money should be distributed. And crucially, loss and damage has been largely excluded from discussions around climate finance.

“We heard a lot of about solidarity [from wealthy countries] for the losses and damages in our experiences,” said Felson. “But if, in the finance room, I raise loss and damage, I hear that it’s a red line. We can’t talk about life and damage in finance [discussions].”

For countries like Belize, the goal is to have a system that doesn’t respond to climate-related disasters and damages on a one-off basis like an emergency relief fund. Rather, they want a systematic approach that delivers consistent money not only in wake of hurricanes and wildfires, but for slow-moving problems like the decline of barrier reefs and falling crop yields.

On Thursday, Scotland announce that it would contribute £2 million to a loss and damage fund, making it the first country to chip in.

Money has also been allocated at COP26 to indirect measures that relate to loss and damage. Twelve donor governments pledged $413 million in new funding for the Least Developed Countries Fund, which helps countries like Gambia and Togo cope with the effects of climate change. The UN’s Adaptation Fund also announced it raised $351.6 in new pledges.

One of the big obstacles though is that wealthy countries do not want any language in a loss and damage agreement that hints that they are liable for climate change. Some are already pushing back against the loss and damage language in the draft agreement.

“With wealthy countries, it’s always a fear of some kind of reparations framework coming out which will impose higher and higher costs,” said Rachel Kyte, an advisor to the climate negotiations and dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University. “They’re prepared to talk about today and tomorrow. They don’t want to talk about yesterday.”

Negotiators for countries facing the brunt of climate impacts now say they at least want to get the ball rolling on paying for current climate destruction. They are calling for language in the COP26 agreement to create a dedicated funding mechanism for loss and damage and give it long-term stability.

But as the negotiations head into their final day with so many outstanding issues, loss and damage may once again end up shelved until the next COP.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment