Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Fearing that candidates of color will alienate white swing voters is an ancient impulse. Two practical objections can be made to it. The first is that political parties that refuse to represent loyal constituencies on the ballot may soon find themselves losing some of their votes. This is a particularly serious threat given signs in 2020 and 2021 of softening enthusiasm for the Democratic Party among Black and especially Latino voters. The second is that appeasing white voters (as Bacon puts it) by running candidates who look and sound like them doesn’t really seem to work very well:

The Virginia race is instructive here. Democrats nominated McAuliffe over several other candidates in the Democratic primary, including two Black women. During his general election campaign, McAuliffe reversed his previous support for a key plank of police reform — getting rid of qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that limits civil suits against officers. So Virginia Democrats took steps right out of the White appeasement playbook — run a White male candidate, move right on racial issues — and lost.

Now it’s probably not fair to assume Virginia Democrats nominated McAuliffe primarily because he was white or because he was willing to hedge a bit on the commitments to racial justice that have been so central to Democratic governance in the commonwealth since the party won trifecta control in 2019. He’s a former governor with universal name ID, unparalleled fundraising prowess, and a solid history of support from and work for non-white Democrats. But the question remains in Virginia and elsewhere: If you are going to lose the votes of racially resentful white voters anyway, why not begin to build the coalition of a more demographically diverse future with candidates who finally offer non-white voters better representation? At some point, the kind of backdoor arrangement between white Democratic leaders and non-white followers stops being prudent and starts being actively offensive.

Interestingly enough, the transition to a new model for Democratic success has progressed more in parts of the South where white racial backlash is a constant reality, as I noted in 2018:

Until very recently, the Democratic constituency of the South was an uneasy coalition of disgruntled, conservative white voters perpetually on the brink of defection and loyal Black voters who felt unappreciated and underrepresented. At different paces in different states but all throughout the region, a new suburban-minority coalition is emerging. It may never achieve majority status in areas that are too white or too rural to sustain it. But it is showing great promise in enough states to make the South’s political future an open question for the first time in this millennium.

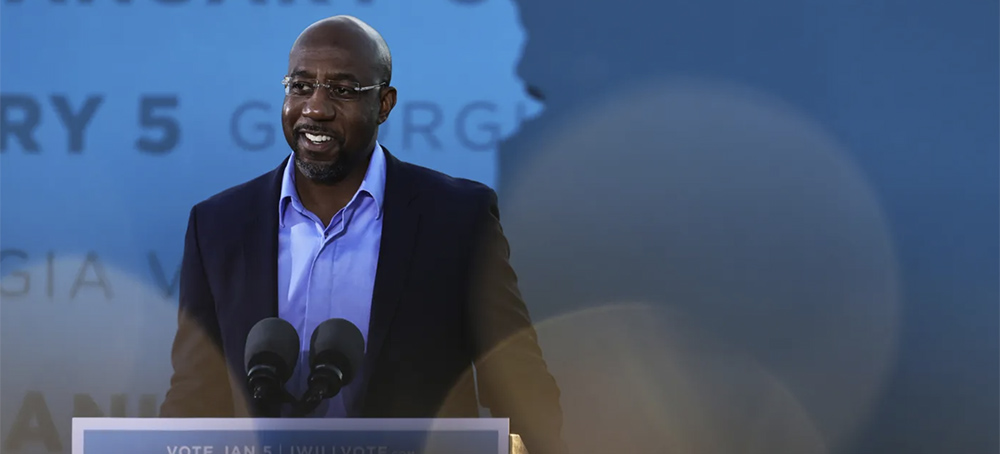

Notably, Black 2018 gubernatorial candidates Stacey Abrams of Georgia and Andrew Gillum of Florida improved on the performance of their white centrist predecessors, though both fell short by heartbreaking (and in Abrams’s case, controversial) margins. In 2020, Black Senate candidate Jaime Harrison (now the DNC chairman) threw a big scare into South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham. A couple of months later, these near victories for Black southern Democrats culminated in the election of Raphael Warnock in a Senate runoff in Georgia. This was a development that would have baffled the old (and in some quarters, still reigning) conventional wisdom about race and politics in the former Confederacy.

In 2022, we will likely see a return of the kind of savage contest between Abrams and Republican Brian Kemp in Georgia, which could pose a new test as to whether white racial resentments are truly on the rise. Warnock himself will face the particular challenge of being opposed by a Black Republican celebrity, football legend and Trump friend Herschel Walker, who will likely campaign on “election integrity” themes designed to arouse racist conspiracy theories about non-white voters.

Whatever happens in these races, it’s precisely the wrong time for Democrats to abandon their new commitment to a more reciprocal relationship with their base in pursuit of vanishingly small swing-voter categories that could be unreachable. If they don’t panic and keep making progress, Democrats still may not escape the historic pattern of midterm losses by the president’s party. But they can build a foundation for a united and growing party in the very near future.

Protesters take part in the Women's March and Rally for Abortion Justice in Austin, Texas, on Oct. 2. The demonstration targeted Senate Bill 8, a state law that bans nearly all abortions as early as six weeks in a pregnancy, making no exceptions for survivors of rape or incest. (photo: Sergio Flores/AFP/Getty Images)

Protesters take part in the Women's March and Rally for Abortion Justice in Austin, Texas, on Oct. 2. The demonstration targeted Senate Bill 8, a state law that bans nearly all abortions as early as six weeks in a pregnancy, making no exceptions for survivors of rape or incest. (photo: Sergio Flores/AFP/Getty Images)

Piper Stege Nelson, chief public strategies officer for the SAFE Alliance, says the father didn't let the young girl leave the house.

"She got pregnant," Nelson says. "She had no idea about anything about her body. She certainly didn't know that she was pregnant."

The girl was eventually able to get help, but if this had happened after Sept. 1, when the state law went into effect, her options would have been severely curtailed, Nelson says.

In Texas, abortions are now banned as early as six weeks into a pregnancy. The law, Senate Bill 8, is currently the most restrictive ban on the procedure in effect in the country. According to a recent NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist national poll, Texas' law is unpopular across the political spectrum.

Notably, the law also makes no exceptions for people who are victims of rape or incest. Social workers in Texas say that's causing serious harm to sexual assault survivors in the state.

"Devastating" for survivors of repeated rape and abuse

While many people don't realize they are pregnant until after 6 weeks, Nelson says this is a particular problem for those who are being repeatedly raped or abused.

That's because to cope with the trauma of the abuse, they often grow numb to what's happening to their bodies.

"That dissociation can lead to a detachment from reality and the fact that she's pregnant," Nelson says. "And so, there again, she is not going to know that she is pregnant by six weeks and she's not going to be able to resolve that pregnancy."

Monica Faulkner, a social worker in Austin who has worked with sexual assault survivors, says not having the option of terminating a pregnancy will make recovering from an assault even harder.

"The impact of finally coming forward and then being told there are no options for you is devastating," says Faulkner, who directs the Institute for Child and Family Wellbeing at the University of Texas at Austin.

Being forced to carry a pregnancy to term can be harmful financially, psychologically and, sometimes, physically. For survivors, that further strips away agency, Nelson says, after their sense of safety and control has already been violated.

"And so when you have something like SB 8," Nelson says, "what it is doing is, it's further taking control and power away from the survivor right at the moment when they need that power and control over their lives to begin healing."

Faulkner says it's important to give sexual assault survivors options on how to move forward in their lives. She says SB 8 "clearly is taking away any choice that they have."

Public opinion, even in Texas, favors exceptions to strict bans

For decades, public opinion — even in Texas — has been pretty consistent about allowing some exceptions to laws that restrict abortion. Most Americans believe there should be exceptions to strict abortion bans.

Carole Joffe, a professor and sociologist who studies abortion policy at the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says that despite public opinion on the matter, most of the anti-abortion bills introduced across the country in recent years haven't included exceptions for rape or incest.

"What we have seen over the years is a dramatic escalation," she says. "I think what Texas shines a bright spotlight on is what disdain we have for the needs of women and girls, or people who can get pregnant even if they don't identify as female."

The history of these types of exceptions is somewhat complicated. Joffe notes that toward the end of the 20th century, it was more common than now for states to include exceptions for rape and incest.

She says this trend to drop exceptions for rape and incest started about 10 years ago, after the Tea Party gained power in Congress and in many statehouses. As many legislatures became more politically conservative, anti-abortion groups started gaining more influence in the lawmaking process.

Anti-abortion movement has a tightening hold on state legislatures

Meanwhile, even as some state legislatures have been increasing the restrictions on abortion, the public views have really remained quite stable," Joffe says, with a sentiment that abortion should be allowed in cases of rape and incest. "The kind of restrictions we are seeing are the product of growing power in state legislatures of the anti-abortion movement," she says.

In 2019, a coalition of anti-abortion groups sent letters to national Republican Party officials following the passage of a controversial abortion law in Alabama. In it, groups asked GOP leaders to "reconsider decades-old talking points" regarding exceptions for rape and incest.

In Texas, the growing power of hardline conservatives in the state has helped anti-abortion successfully push for more restrictive laws.

John Seago, the legislative director with Texas Right To Life — an influential anti-abortion group that pushed for SB 8, says the political shifts in the Texas legislature have made it easier to enact stricter abortion laws.

"In the last ten years, in Texas, our Republican majority has been growing," he says. "And kind of right around 2011/2013 we were really having enough votes to pass strong legislation."

And by "strong" Seago means not having to compromise on things like allowing abortions when severe fetal abnormalities are detected. Texas got rid of those exceptions a few years ago. And now that the new law in Texas doesn't exempt rape and incest, Seago says, it's more consistent with the underlying philosophy that groups like his hold.

"We are talking about innocent human life — that it is not their crime, it was not their heinous behavior that victimized this woman," he says. "And so why should they receive the punishment?"

The problem of pregnancies arising from sexual assault is not a small one. One study estimates that almost 3 million women in the U.S. have become pregnant following a rape.

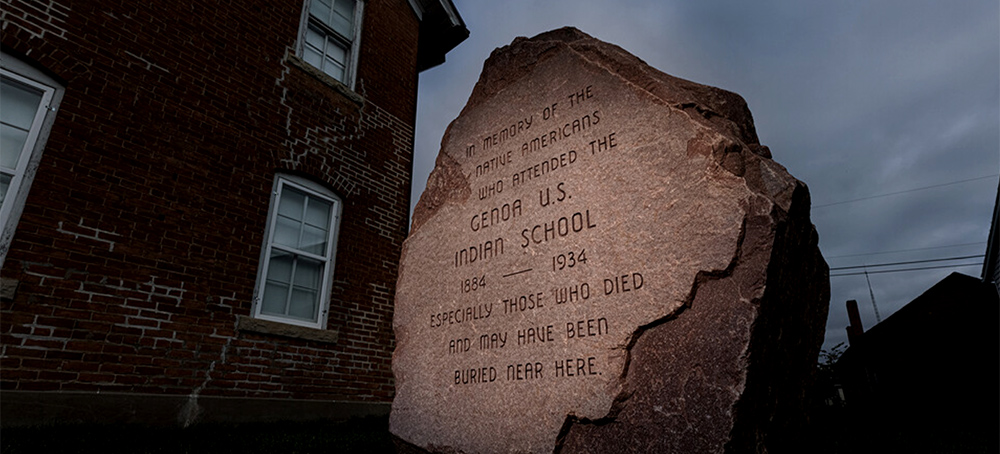

A monument is erected outside the former Genoa Indian Residential School in Genoa, Nebraska. (photo: Craig Chandler/University Communication)

A monument is erected outside the former Genoa Indian Residential School in Genoa, Nebraska. (photo: Craig Chandler/University Communication)

Researchers say they have uncovered the names of 102 Native American students who died at a federally operated boarding school in Nebraska

The Omaha World-Herald reports that the discovery comes as ground-penetrating radar has been used in recent weeks to search for a cemetery once used by the school that operated in Genoa from 1884 to 1934. So far, no graves have been found.

The Genoa school was one of the largest in a system of 25 federally run boarding schools for Native Americans. The dark history of abuses at the schools is now the subject of a nationwide investigation.

Margaret Jacobs, co-director of the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project, said some of the names identified so far might be duplicates, but the true death toll is likely much higher.

Jacobs said that many of the children died of diseases including tuberculosis. Some other deaths such as a drowning were reported by newspapers at the time.

When the school closed, documents were either destroyed or scattered across the country. Locating them has proved challenging for both the Genoa project and others working to gather information on the schools.

Many of the names linked to Genoa were found in newspaper archives, including the school’s student newspapers, said Jacobs, who also is a history professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

F.B.I. (photo: Mary F. Calvert/Reuters)

F.B.I. (photo: Mary F. Calvert/Reuters)

The fake emails appeared to be from a legitimate FBI email address ending in @ic.fbi.gov, the FBI said in a statement on Saturday. The hardware impacted by the incident "was taken offline quickly upon discovery of the issue," the FBI said.

In an update issued on Sunday, the bureau said that a "software misconfiguration" allowed an actor to leverage an FBI system known as the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal, or LEEP, to send the fake emails. The system is ordinarily used to by the agency to communicate with state and local law enforcement partners.

"No actor was able to access or compromise any data or PII [personal identifiable information] on the FBI's network," the bureau said. "Once we learned of the incident, we quickly remediated the software vulnerability, warned partners to disregard the fake emails, and confirmed the integrity of our networks."

The spam emails went to 100,000 people, according to NBC News, and warned recipients of a cyberattack on their systems. The FBI and Department of Homeland Security routinely send legitimate emails to companies and others to warn them about cyber threats. This is the first known instance of hackers using that same system to send spam messages to a large group of people, NBC reports.

The Spamhaus Project, a threat-tracking organization, posted on Twitter what it said was a copy of one such email. It showed a subject line of "Urgent: Threat actor in systems" and appeared to end with a sign-off from the Department of Homeland Security.

Both the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security's Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency are aware of the incident, the FBI said Saturday.

Bricks piled in a dirt lot where the Town House Motor Lodge once stood near the Sands Regency Hotel Casino in downtown Reno. The casino is owned by the developer Jeffrey Jacobs. (photo: David Calvert/ProPublica)

Bricks piled in a dirt lot where the Town House Motor Lodge once stood near the Sands Regency Hotel Casino in downtown Reno. The casino is owned by the developer Jeffrey Jacobs. (photo: David Calvert/ProPublica)

Reno, Nevada, has one of the worst affordable housing shortages in the U.S. Yet city officials let an out-of-state casino owner displace hundreds of low-income residents so he could one day build an entertainment complex.

Then, about 10 years ago, he found Nystrom House, in the shadow of downtown Reno’s Sands Regency Hotel Casino. The rent was affordable. For $450 a month, he had a room with a shared kitchen and bathroom.

To Block, the eight-room home on Ralston Street — though aging and not the grand house it had been in its heyday — was an oasis in a busy, and often rough, neighborhood on the western edge of downtown. Fruit trees sheltered the backyard from the lights of nearby casinos. When he returned home from his job as a dishwasher, the neighborhood cat would be waiting. Block would lie on the grass and let her curl up on his chest.

“I liked that place,” he said. “It felt like home to me.”

In late 2016, an out-of-state casino owner, Jeffrey Jacobs, started buying up property surrounding Nystrom House: vacant land, derelict houses, historic mansions, a car repair shop, a dry cleaner, a wedding chapel, a neighborhood bar, a gas station. And motels, lots of motels. Within months, Jacobs owned Nystrom House, too.

Then, as Block and his housemates watched, Jacobs began demolishing the motels. First the Carriage Inn and Donner Inn Motel. Then the Stardust Lodge. Next, the Keno, El Ray and Star of Reno fell. The motels, decades past their prime, had served as housing of last resort for hundreds of people with extremely low incomes and few other options. Jacobs was clearing the way for what he said will be a $1.8 billion entertainment district anchored by his two casinos.

Jacobs’ property manager called a meeting of the Nystrom House tenants one day in mid-2018. She served free barbecue and told them they would need to find new places to live. She said she’d help.

Block, like hundreds of others in motels and boarding houses bought by Jacobs in the last five years, was thrust into Nevada’s brutal affordable housing shortage — a crisis that is among the most severe in the country for extremely low-income renters, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

A ProPublica investigation found that local policies and federal tax breaks have accelerated demolition of motels and other properties where extremely low-income residents live, while doing little to help those who have lost their homes. Unlike some cities, Reno has no policy to deter demolition of affordable housing, and no requirements to replace lost units. Once such housing is gone, it often stays gone.

Though the Reno City Council’s strategic plan lists addressing the housing crisis as one of six goals, it doesn’t specify how many units should be built or what to do with people who’ve lost their homes. Instead they call for “partnering with other agencies” and implementing “proven approaches,” which they don't name.

City leaders have not used Jacobs’ project as leverage to increase and improve affordable housing options. They’ve been reluctant to slow what they see as an opportunity unlike any in recent history to remake the city. They’ve been enthusiastic boosters of the project, waiving requirements and making phone calls to property owners on Jacobs’ behalf.

The city also has made it easier for Jacobs to profit from any development that follows his demolitions. It has deferred building permit fees and extended the time that he can use fee credits for connecting to the city sewers, meaning he can hold vacant land for longer without losing those credits. Meanwhile, a Trump-era federal tax program that applies to development in the neighborhood has created additional incentives for developers to build market-rate or luxury housing, not affordable housing.

In his public rhetoric, Jacobs doesn’t leave room for the idea that the buildings he demolishes are anything but cesspools.

“The motels in the area that we demolished were structures that no one should have to live in, and rented for $1,400-$1,500” a month, Jacobs said in a written response to ProPublica’s questions. (He declined an in-person interview.) Jacobs said he has spent $400,000 to relocate 280 people who lived in the properties.

“There are only a couple of these properties left in the area, run by local and out of town slumlords. The increasing value of the land in the area will ultimately cause these properties to recycle into a higher and different use,” Jacobs said.

But not all of the motels are slums and some charge far less than $1,400 a month. While their number is dwindling, more than 50 remain citywide. As of February, an estimated 2,550 people lived in Reno’s motels.

Reno is not the only city in the region facing a shortage of low-income housing. The crisis is particularly acute in cities like Denver, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Colorado Springs and Tucson, in part, because the region started with far less public housing than the national average. From the 1930s to the 1960s, when the federal government was more focused on building public housing for the poor, Southwestern cities were in their infancy and federal resources largely went to bigger, more established cities. Today, Arizona ranks last in public housing units per 1,000 people, according to U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development data. Nevada and Utah also rank near the bottom.

In Reno, these dynamics are playing out across 15 blocks of downtown, where city government has allowed the demolition of nearly 600 units of last-resort housing in exchange for Jacobs’ inchoate promise of a grand $1.8 billion entertainment district. The details of what that district might eventually look like have changed repeatedly. Most recently, Jacobs has promised a hub of hotels, restaurants and condo towers — though he’s made little progress on any of it.

So far, the developer has purchased more than 100 parcels, including 19 motels — 14 of which have been demolished.

By 2001, Jacobs’ companies owned, controlled or had the option to purchase 10 parcels, including those containing 0 motel rooms and other housing units that have since been demolished or boarded up.

Reno officials have not taken issue with the displacement of the motels’ residents. Instead, the mayor and some council members have cheered the demolitions, even as housing advocates have pleaded with them to preserve and update the buildings or create alternative housing before turning people out of their homes. Only 326 subsidized housing units have been built in Reno during the last six years, an amount that failed to keep pace with the city’s growth.

“That housing was not affordable housing. That housing was horrific,” Reno Mayor Hillary Schieve said of the buildings demolished by Jacobs. “It’s wrong to continue to say we took away people’s housing. Honestly, what happened, it needed to happen a long time ago. We let it go on way too long and subjected people to horrific conditions for a very long time and that’s what we should be ashamed of.”

Much of the land purchased by Jacobs remains vacant. A few of the parcels, including where Nystrom House stood, have been converted to parking lots. Some are adorned with sculptures from the annual Burning Man event: a 35-foot polar bear made of car hoods; a 12-ton steel Mongolian warrior; a pair of dancing bumblebees in ballet slippers. Jacobs lined one recently cleared block with replicas of Reno’s historic neon signs, some bearing monikers of the demolished motels. The people who used to live in those motels refer to the row of neon replicas as the sign graveyard. Jacobs calls it the Glow Plaza.

Although Jacobs appears to have helped some former tenants find new housing, some who resided in buildings he demolished have ended up living in their cars, on the banks of the Truckee River or in similarly decrepit motel rooms.

In the three years since Block was forced to leave Nystrom House, he’s been shuffled from room to room by Jacobs’ property manager. His options are dwindling. He has received an eviction notice from Jacobs’ company for his current residence and is once again trying to stay one step ahead of homelessness.

Developing With the Help of Public Subsidies

When Jacobs first entered the Reno market, he had begun building an empire of small casinos and gambling halls in three states. The scion of a wealthy family of Ohio real estate moguls, he also had a Cleveland redevelopment project under his belt: a riverfront entertainment complex.

In 2001, Jacobs bought his first Reno property, the Gold Dust West, a small casino that catered to locals. If he had plans beyond that, he kept them quiet. But 15 years later, he used limited liability companies that shielded his identity to begin assembling land around that casino. He also brokered a $26 million deal to buy a much larger hotel and casino three blocks to the east: the Sands Regency.

Since then, Jacobs has bought every parcel he could in between his casinos, using them as collateral for the $435 million in debt carried by his company, according to property records.

Once he bought the Sands, Jacobs could no longer keep his acquisitions quiet. Initially, Jacobs offered few details. He simply told the public he planned to remodel the Sands Regency and build a $500 million mixed-use entertainment project called the Fountain District. The district might include up to 300 housing units, he said at the time.

Even with scant details, Jacobs’ plan appealed to city leaders who had spent decades trying to remake Reno.

Once the booming gambling capital of the state, the city had seen tourism, the economic lifeblood of its downtown, go into steep decline since the early 2000s. Las Vegas emerged as the country’s leading gambling resort city, and Native American casinos in California had siphoned away many regional visitors. But Jacobs saw an opportunity.

“After the 2010 recession I realized that the California Native American casino impact on Reno had bottomed out and I believed that growth and opportunity lay ahead for Reno,” Jacobs told ProPublica.

Today Jacobs calls his project The Neon Line District. He says the project will include hotels, restaurants and up to 3,000 housing units — 10 times the number in the original plan. There could be an outdoor amphitheater. Most recently he said he might add a zip line.

In Reno, Jacobs is following the same strategy he’s used in the past: relying on public subsidies to further his development efforts.

In the 1980s, while serving a term as an Ohio state lawmaker, Jacobs sponsored unsuccessful legislation to publicly finance a Cleveland stadium project he and his partners were pitching, according to the Akron Beacon Journal. Later, his family and their partners used voter-approved sin tax revenue to build Jacobs Field — now Progressive Field, home of the Cleveland Guardians, a team Jacobs’ father used to own. (After his term in the Ohio Legislature, Jacobs ran unsuccessfully for state treasurer. His campaign consultant: Roger Stone.)

In the 1990s, Jacobs asked for $4 million in improvements from Columbus, Ohio, for a proposed development there. He told the Cincinnati Enquirer that he might need the city to use eminent domain to help him acquire land. That development never materialized. In Toledo, Ohio, Jacobs proposed building an entertainment district at a declining mall, saying he would need city and state financing. That project also never happened. Jacobs told ProPublica he had “conversations” with both cities about “public-private partnerships,” but a “national recession” put an end to both ideas.

When he started buying motels in Reno, Jacobs began contributing to Reno council members’ campaigns, giving to those who supported his project and to the opponents of those who didn’t. Since 2017, he’s contributed $33,250 to Reno council candidates. Mayor Schieve got the majority of that money: $21,500.

Jacobs also hired as his lobbyist a former Reno city council member. Referred to by some city staff as the “eighth council member,” Jessica Sferrazza has ties to key city employees and is a close friend of Schieve, a fact the mayor discloses publicly every time the council votes on Jacobs’ project. Jacobs also hired an experienced city planning lawyer, Garrett Gordon, with a long history of helping developers get their projects approved by the City Council.

Jacobs and his team have won public subsidies while limiting public input. According to statements by both Jacobs and council members, many of the conversations about his project took place in private. Jacobs refused a council member’s request for a town-hall-style meeting prior to approval of his subsidy requests. And in 2018, his company withdrew support for a community-driven design plan for that part of downtown. Eventually, the city nixed the plan. Council member Jenny Brekhus said it was done at Jacobs’ request.

“The assistant city manager had conversations with the Jacobs group and their consultants and told me that Jacobs did not want this planning effort because they were, quote, ‘afraid of losing control of planning in the area,’” Brekhus said.

The assistant city manager told ProPublica Jacobs withdrew support for the community plan because he was worried Brekhus, a vocal critic of Jacobs, would use it to thwart his project.

As a result, there has been no comprehensive effort to solicit public input on the demolitions or on how to increase affordable housing in the district.

Schieve denied her support for the project has been influenced by Jacobs’ campaign contributions or choice of lobbyist.

“I approve good projects. I don’t approve projects based on relationships,” she said.

“My Name Is Doug and I’m With the City of Reno”

Those eager to see downtown rescued from decay are anxious to see construction begin. “I’m sitting there watching it like I’m across the street from Disneyland,” said one nearby property owner. “I hope something stupendous happens.”

But not all property owners want to sell, even at the prices Jacobs is offering. (He paid the owners of one motel five times what they had bought it for in 2012, according to assessor records.)

In these situations, Jacobs has again turned to City Hall.

When Jacobs started sniffing around the Midtown Motel on West Second Street, its owner, Kathie Mead, didn’t give it much thought. She wasn’t interested in selling, leasing or signing an option agreement.

In addition to providing retirement income for Mead and her husband, the Midtown Motel serves an important need in the community. A shortage of housing in Reno has driven costs higher. The vacancy rate for rentals is 1.6%, significantly tighter than the regional average of 4.4%. The national average is 5.8%. As a result, the average rent in Reno is $1,600 a month.

Mead’s rooms rent for far less and have become a place for those who either can’t afford, can’t qualify for or can’t find a home in Reno’s market. She’s rented to some tenants for more than a decade and kept their rent low. Some pay as little as $650 a month.

She continued to ignore calls from Jacobs and his people. But on Aug. 30, a different call came in. She recognized it as a city government phone number. She answered.

“My name is Doug, and I’m with the city of Reno,” the caller said, according to Mead.

Doug wanted to know if Mead would meet with him and Jacobs that Thursday on the 17th floor of the Sands. He neglected to mention his job title: city manager.

“I’m really baffled with what the city of Reno has to do with this,” Mead said she told Reno City Manager Doug Thornley. “He said, ‘No, no. We set up meetings like this all the time. It’s just to get your questions answered.’”

Mead refused the meeting. But the call left her unsettled. “Is this some kind of pressure? Are they telling me they are going to take my property if I don’t agree to sell to this person?” she said.

In an interview with ProPublica, Thornley denied calling Mead to exert pressure to sell to Jacobs. At the request of Jacobs’ representatives, Thornley said, he had reached out to “several” property owners who had been ignoring the developer’s calls. Each one turned him down.

“I have never been part of a discussion involving the Jacobs folks or another property owner on whether or not a property would, should, could be available for sale,” Thornley said. “That’s not me. That’s not my business.”

Contrary to what Jacobs said about Reno motel owners, Mead hardly fits the definition of a slumlord. Her motel is not the subject of repeated code violations. And she keeps her prices low, especially for long-term tenants.

Cecilia DeRush never dreamed she’d spend her retirement in a weekly motel. She used to own transmission repair shops, where she worked as both bookkeeper and transmission rebuilder. But for the past eight years, she and her partner, Karl Hager, have lived at the Midtown Motel. They pay $650 in rent for a place with a main room big enough for a bed, small couch, chest of drawers and TV stand. There’s a small kitchen, where DeRush keeps a pot of coffee brewing for Hager, who sips constantly as he watches television. The walls are decorated with artwork of Nevada’s iconic wild horses and family photos.

DeRush knows Jacobs has been pushing Mead to sell. She’s confident Mead will fend him off.

“If he got it, he would tear it down,” she said, shaking her head at the thought of trying to afford rent at a typical apartment on their $1,400 in monthly income. “Can he get his claws in deep enough to force her to sell? That’s the question.”

Lost Leverage

Jacobs' aggressive land acquisition and ambitious plans have given Reno leverage it could use to address its crisis — largely because he wants public assistance to build the project. In exchange for his demands for discounted land, waived or delayed building fees and subsidies from future tax revenue, the city could require him to provide affordable housing.

This summer, it appeared the city might do just that. An early draft of a development agreement obtained by ProPublica would have required Jacobs to make 15% of all new housing in the district affordable — a requirement that could have replaced three-quarters of the demolished housing units.

In mid-October, the City Council scheduled a key vote on the development agreement that would spell out which financial and regulatory incentives Jacobs would be granted by the city and what he would do in return. That morning, dozens of people arrived at City Hall. Some wanted information about what Jacobs would build. Some thought the council should help get the entertainment district off the ground.

But others were there to urge the council to better care for the people being displaced by Jacobs: Was the council willing to use its leverage with the developer to address the city’s dwindling supply of affordable housing?

Four hours into the meeting, the council began discussing the agreement. Everyone who wanted to comment on the project had left.

But one key figure had just arrived: Jacobs.

It was a rare appearance at a public meeting for him. Wearing pressed blue jeans, a navy suit coat and a checked shirt, Jacobs took a seat in the middle of the nearly empty room.

Although most of the public had departed, under the council’s rules it was required to play public comments left by voicemail. As Jacobs sat impassively, the voice of George Campagnoni filled the chambers.

Campagnoni had lived in downtown’s Courtyard Inn when Jacobs bought it. At one point, Jacobs’ property manager told Campagnoni and his neighbors they’d have a year to vacate.

“One month later, they’re kicking us out, telling us we had to move, we had to get out of there,” Campagnoni said. Nearly three years after they were forced out, the motel still stands, but it’s empty. That fact rankles Campagnoni, whose rent is almost 50% higher in his new room in a downtown apartment building.

“They have done nothing but left vacant, dirty lots all over the city of Reno,” he said. “They do not deserve any compensation.”

(During an interview later in his tiny studio apartment, Campagnoni chuckled when told Jacobs had been present to hear his comments. “Good! Good!” he said.)

In early negotiations with the city, Jacobs had asked for a nearly $3 million discount on city property, but ultimately paid market rate in exchange for fewer restrictions on how he could use the land. He had also asked for $20 million of the future property tax revenue generated within his district, but set aside that request for later.

At this meeting, Jacobs asked for initial approval for streetscape design elements, including special lighting, signage and skyways. He also wanted $4.7 million in credits for pedestrian amenities and more time to use $1.6 million in sewer credits earned when he demolished his motels. Usually the city gives a landowner five years after demolishing a building to reconnect new construction to the sewer system without paying any fees. Jacobs wanted 20 years, an incentive that would allow him to sit on vacant land for two decades without losing the credits.

In return for any of these requests, the council could have demanded the construction of affordable housing. Instead, the city gave Jacobs nearly everything he asked for without requiring the replacement of any low-income housing.

The council did reject Jacobs’ request for 20 years to use his soon-to-expire sewer credits, instead giving him an additional five years. And it added a requirement that he apply for building permits for 63 condominium units within a year. But the 15% affordable housing requirement wasn’t part of the final agreement.

Jacobs had steered the city away from using the project to advance its housing goals. He declined to comment on why he didn’t agree to the affordable housing requirement in the draft development agreement.

In Thornley’s view, the best way for Reno to increase its stock of affordable housing is by adopting citywide ordinances that make it easier to build new units, or by requiring all housing developers to include some affordable units, not by leveraging one project.

“That would go a longer way toward development and preserving the naturally occurring affordable housing than any sort of requirement in an agreement,” Thornley said.

But that has also been a challenge. In 1999, the Legislature authorized inclusionary zoning, which requires new developments to include some affordable units, but no Nevada cities have actually adopted such an ordinance. Earlier this year, lawmakers killed a bill that would have allowed cities to require developers to pay fees to fund affordable housing in lieu of requiring them to build it directly. The city of Reno has passed several smaller initiatives to address housing, such as density bonuses, which let developers build more units than zoning allows, reduced parking requirements for affordable projects and fee deferrals.

Reno’s affordable housing shortage is so severe, however, that the City Council would be justified in more aggressively leveraging individual projects to address it, said Christine Hess, executive director of the Nevada Housing Coalition.

“The opportunity to ask the developer to contribute truly affordable units, meaning units that have some income restrictions, would be helpful,” Hess said. “Private developers are a really important part of the solution. ... Those units don’t build themselves.”

Jacobs hasn’t ignored the housing crisis entirely. He’s promised to set aside as affordable 10% of any housing his company builds and operates — for example, Renova Flats, the one motel he has renovated to market-rate housing. Renova Flats’ deed, however, doesn’t require any affordable housing or income restrictions. The only thing holding Jacobs to it is his word.

Renova Flats is only 46 units, and Jacobs’ representatives have indicated he has little interest in being a residential landlord. They said he’d much rather focus on the entertainment aspects of his project and sell excess assembled land to housing developers. For those developments, his promise that 10% of the units will be affordable wouldn’t apply.

Jacobs has donated $1.5 million to the Reno Housing Authority, which went toward a $13 million, 44-unit senior housing project. And Jacobs counters criticism of his housing demolition by pointing out he did not exercise an option to buy and renovate a subsidized housing project on the edge of his Glow Plaza called the Sarrazin Arms apartments.

In an interview with ProPublica, Mayor Schieve said she’s wary of requiring landowners to replace demolished housing, because it could hinder development. She agreed the city should develop a better policy to help displaced residents.

“I do think we have not handled it the best,” she said.

But so far, she’s relied on private conversations with Jacobs and his representatives to ensure they are helping residents rather than spearheading a policy change.

“Gentrification on Steroids”

Federal programs still exist to encourage private construction of affordable projects and rehabilitate deteriorating housing stock — resources that cities can marshal to address shortages. But on the land assembled by Jacobs, federal policy is working against Reno’s affordable housing goals.

Reno’s downtown is in a special tax zone for low-income census tracts, a designation that can promote demolition of affordable housing in favor of investment — any investment. In February 2018, city officials nominated a handful of qualifying census tracts for the then-new federal Opportunity Zone program. According to emails obtained by ProPublica, city officials put Jacobs’ land at the top of the list they sent to the governor’s office. The census tract where it’s located met the federal criteria for poverty rate and median income. The fact that projects by Jacobs and others had already been proposed for the area made it even more desirable to the governor’s office for the designation.

This June, the U.S. Treasury Department certified it as an Opportunity Zone.

Under Opportunity Zone rules, investors in Jacobs’ project can get a deferral and discount on paying taxes on capital gains invested in the zone. Even bigger tax breaks come in a decade, when any subsequent gains on that initial investment become tax-free. That provision could, in this case, end up working against affordable housing development.

Opportunity Zones take an “agnostic” approach to investment, operating under the belief that “investment equals benefits regardless of what that investment is,” said Urban Institute senior fellow Brett Theodos. Opportunity Zones do not prioritize the social good.

Because the benefit is directly proportional to the size of the investment gains, the program tends to discourage projects that won’t generate a large profit. Affordable housing development is not an enterprise that generates large profits.

“Opportunity Zones are a tool, it’s like a hammer,” Theodos said. “You can use a hammer to build a house or you can use a hammer to tear one down.

“Maybe that was not all high-quality housing, but until we provide an alternative, even housing of last resort is housing. It’s better than a shelter. It’s better than under a bridge.”

The Opportunity Zone’s influence on Reno’s motel demolitions is reminiscent of the 1990s, when the federal government incentivized cities to demolish decaying public housing projects. The stated intent of the HOPE VI program was to “eradicate severely distressed” public housing and build subsidized units in mixed-income developments. Tens of thousands of such units were demolished across the country, while only a fraction were replaced.

In Utah, housing advocates have seen a similar dynamic play out in Opportunity Zones. An established mobile home park in the city of Layton was uprooted for an incoming development, they said.

“The people who live there are pretty much screwed,” said Francisca Blanc, advocacy and outreach coordinator for the Utah Housing Coalition, who refers to Opportunity Zones as “gentrification on steroids.”

Housing experts refer to low-rent homes that don’t come with subsidies or rent controls — like Reno’s weekly motels — as “naturally occurring affordable housing.” Given the struggle to add affordable housing, the preservation and rehabilitation of such units is key to addressing the crisis.

“In areas where there is high demand for housing, that affordability is very much at risk,” said Andrew Aurand, vice president for research at the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Because the Opportunity Zone law requires almost no public reporting, it is difficult for researchers to determine how effective the tax incentives are at spurring investment in underserved areas, Theodos said. A qualitative study by the Urban Institute found multiple barriers to “mission-oriented” projects such as affordable housing. One of them was that such projects “yield below market returns that most OZ investors appear unwilling to accept.”

Previous reporting by ProPublica and others revealed that the wealthy have used political connections to designate areas with existing investments as Opportunity Zones, taking tax breaks meant to help the poor. Again, because of the lack of reporting requirements, it’s impossible to know how widespread that abuse is.

Jacobs told ProPublica he is not using Opportunity Zone financing. The rules preclude casinos from receiving the tax breaks. But the designation alone makes his assembled land more valuable.

Some of the developers considering buying those sites “will include OZ credits in their sources of financing,” Jacobs said.

Incentives, both local and federal, that Jacobs has cobbled together have already yielded gains. In September, Jacobs sold one of his parcels for 60% more than he paid for it 18 months ago.

“I Just Wish He Hadn’t Ever Come Here”

When Jacobs moved the tenants out of Nystrom House, Block landed at the Lido Inn, which Jacobs also demolished, then at a former wedding chapel across from Jacobs’ Glow Plaza.

While Block lived at the chapel, Jacobs cleared the land where Nystrom House stood. Built in 1875, it had served as a boarding house for out-of-state divorce seekers in the early 20th century and had been put on the National Register of Historic Places. That had given Block a false sense of security when he moved in.

“I thought maybe this is some place that is going to be here for a while,” Block said.

Rather than demolishing the house, Jacobs moved it to an empty lot next door to the chapel, where Block was living. The house still sits there: empty, resting slightly cockeyed on a temporary support structure, many of its windows shattered. With the house gone, Jacobs plowed under the fruit trees and shrubbery that had created a neighborhood oasis.

“He just leveled all the properties there on that street,” Block said. “That’s the thing that made me, like, not even want to know this person. I just wish he hadn’t ever come here.”

Block’s time at the chapel didn’t last. Jacobs’ property manager moved him to Renova Flats. The average rent there is $1,000 a month. The property manager gave Block a substantial discount so he could afford a room.

Block paid on time and made progress paying off fees he was charged to move in. But in July, he came home from work to find a no-cause eviction notice on his door.

The property manager told him the rent discount wasn’t permanent, he said. She gave him additional time to find a place and put his name on the waiting list for a room at a transitional housing project in an industrial area. Block doesn’t blame the property manager, saying she’s done her best to help. His ire rests with Jacobs.

It’s “like we don’t matter,” Block said. “It just feels like we’re kinda in the way. Like they’re just trying to move people that don’t make a lot of money. But, being born and raised here, I just feel like that’s not fair. I’ve invested the time in my life to making this a better place.”

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the president of Mexico, speaks during the daily briefing in May 2021 in Mexico City. (photo: Hector Vivas/Getty Images)

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the president of Mexico, speaks during the daily briefing in May 2021 in Mexico City. (photo: Hector Vivas/Getty Images)

The Mexican president considered that as the European community was created and later the European Union, "so we need a kind of union and integration with respect to the sovereignty of all countries to strengthen us as a commercial economic region in the world."

In his morning conference, the president said this Friday that in the talks with the last two U.S. presidents, Donald Trump and Joe Biden, there were moments of great tension, but he believes that the essence of it all is that he convinced them that they could not close their economy.

“We did a job to convince them that the United States could not develop without Latin America. We are even recommending that what is most convenient is not only economic integration with respect for sovereignty but for all of America," said the president.

AMLO — as the Mexican president is known, alluding to the initials of his name — considered, then, that as the European community was created and later the European Union, "so we need a kind of union and integration with respect to the sovereignty of all countries to strengthen us as a commercial economic region in the world."

He went on to say that he will personally ask his U.S. counterpart, Joe Biden, to promote the creation of an 'American union' of all the countries of the continent, similar to the European bloc made up of 27 states.

Today, more than ever, the unionist thinking and vision of Simón Bolívar exists in the different integration mechanisms in Latin America, says an expert. AMLO has explained that "it is a fact" the exponential growth of the economy and trade in Asia.

The Mexican President's proposal to replace the OAS with a truly autonomous body could be in line with the history of the Latin American region in its drive for integration.

Faced with the increase in maritime transport prices, he questioned, “why are we going to import goods from other countries if we can produce them in North America?”

He also pointed out that the region has many favorable aspects, mainly the young labor force, which is why it is necessary to deal with migration differently.

The Mexican president will travel to Washington to participate in the first face-to-face meeting with his Canadian and American counterparts, Justin Trudeau and Joe Biden, respectively, on November 18.

This year, the garden produced more than 8,000 pounds of produce, while the panels above generate enough power for 300 local homes. (photo: Kirk Siegler/NPR)

This year, the garden produced more than 8,000 pounds of produce, while the panels above generate enough power for 300 local homes. (photo: Kirk Siegler/NPR)

"Our farm has mainly been hay producing for fifty years," Kominek said, on a recent chilly morning, the sun illuminating a dusting of snow on the foothills to his West. "This is a big change on one of our three pastures."

That big change is certainly an eye opener: 3,200 solar panels mounted on posts eight feet high above what used to be an alfalfa field on this patch of rolling farmland at the doorstep of the Rocky Mountains.

Getting to this point, a community solar garden that sells 1.2 megawatts of power back into the local grid wasn't easy, even in a progressive county like his that wanted to expand renewable energy. When Kominek approached Boulder County regulators about putting up solar panels, they initially told him no, his land was designated as historic farmland.

"They said, land's for farming, so go farm it," Kominek says. "I said, well, we weren't making any money, you all want to be 100% renewable at some point so how about we work together and sort this out."

They eventually did, with help from researchers at nearby Colorado State University and the National Renewable Energy Lab, which had been studying how to turn all that otherwise unused land beneath solar panels into a place to grow food.

With close to two billion dollars devoted to renewable power in the newly passed infrastructure bill, the solar industry is poised for a win. But there have long been some tensions between renewable developers and some farmers. According to NREL, upwards of two million acres of American farmland could be converted to solar in the next decade.

But what if it didn't have to be an either or proposition? What if solar panels and farming could literally co-exist, if not even help one another.

That was what piqued Kominek's interest, especially with so many family farms barely hanging on in a world of corporate consolidation and so many older farmers nearing retirement.

Last year, Boulder County updated its land use code. And soon after Kominek installed the solar panels on one of this pastures. They're spaced far enough apart from one another so he could drive his tractor between them.

Still, when it came time to plant earlier this year, Kominek was initially skeptical.

But he soon discovered that the shade from the towering panels above the soil actually helped the plants thrive. That intermittent shade also meant a lot less evaporation of coveted irrigation water. And in turn the evaporation actually helped keep the sun-baked solar panels cooler, making them more efficient.

By summer, Kominek was a believer.

Walking the intricately lined rows of veggies beneath the panels, he beams pointing out where the peppers, tomatoes, squash, pumpkins, lettuces, beets, turnips, carrots were all recently harvested. The farm is still bursting with chard and kale even in November.

"Oh yeah, kale never dies," Kominek says, chuckling.

Kominek's farm, rebranded as Jack's Solar Garden (Jack is his grandfather's name), is part of a burgeoning industry known as agrivoltaics. It's a relatively new field of research and Kominek's farm is one of only about a dozen in the United States known to be experimenting with it.

But agrivoltaics is drawing particular interest in the West, now in the grips of a 22 year megadrought.

"Around the western US, water is the reason to go to war," says Greg Barron-Gafford, a University of Arizona professor who is considered one of the country's foremost experts in the field.

"Water is the reason we have to have real big arguments about where we're going to get our food from in the future," he says.

Barron-Gafford's research in the Arizona desert showed some crops grown underneath solar panels needed 50% less water. He and other scientists have their eyes on the infrastructure bill and are pushing to get some of the estimated $300 million included in it for new solar projects to go toward agrivoltaics.

"If you really want to build infrastructure in a way that is not going to compete with food and could actually take advantage of our dwindling resources in terms of water in a really efficient way, this is something to look at," Barron-Gafford says.

Researchers say there needs to be financial incentives for family farmers to add solar to their portfolio, if solar gardens like Byron Kominek's are really going to take off and become mainstream.

In Kominek's case, he literally bet the farm in order to finance the roughly $2 million solar arrays.

"We had to put up our farm as collateral as well as the solar array as collateral to the bank," he says. "If this doesn't work, we lose the farm."

But farming is all about taking on risk and debt, he says. And early on anyway, it's looking like his bet could pay off.

"That humming [you hear] is the inverters making us money," he says, pointing toward an electric converter box mounted near a row of kale. A series of wires carry the power out to the county highway and onto the local Xcel Energy grid.

The inverters here generate enough power for 300 homes to use in a year. Kominek hopes to soon grow enough food beneath the panels to maybe feed as many local families.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment